Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine plasma-activated buffer solution (PABS) and plasma-activated water (PAW) combined with ultrasonication (U) treatment on the reduction of chlorothalonil fungicide and the quality of tomato fruits during storage. To obtain PAW and PABS, an atmospheric air plasma jet was used to treat buffer solution and deionized water at different treatment times (5 and 10 min). For combined treatments, fruits were submerged in PAW and PABS, then sonicated for 15 min, and individual treatment without sonication. As per the results, the maximum chlorothalonil reduction of 89.29% was detected in PAW-U10, followed by 85.43% in PABS. At the end of the storage period, the maximum reduction of 97.25% was recorded in PAW-U10, followed by 93.14% in PABS-U10. PAW, PABS, and both combined with ultrasound did not significantly affect the overall tomato fruit quality in the storage period. Our results revealed that PAW combined with sonication had a significant impact on post-harvest agrochemical degradation and retention of tomato quality than PABS. Conclusively, the integrated hurdle technologies effectively reduce agrochemical residues, which helps to lower health hazards and foodborne illnesses.

Keywords: Plasma activated water, Plasma-activated buffer solution, Sonication, Tomato, Chlorothalonil reduction, Storage

1. Introduction

Novel cold plasma (CP) as a food processing technique has been established to influence food products positively [1]. The potential utilization of plasma innovation is broad and contains microbial decontamination, removal of toxins, food packaging dynamics, and agrochemical degradation [2]. Agrochemicals, such as pesticides and fungicides, are used in modern agriculture to improve crop production and protect them from pests and fungal attacks. Among fungicides, chlorothalonil is widely used for crops, especially tomato fruits, to protect against fungal disease [3]. However, tomatoes have been associated with health hazards and foodborne illnesses due to microorganisms or agrochemical residues [4], [5], [6]. According to USDA, the maximum residual limit (MRL) of chlorothalonil fungicide in tomato fruit is 5 mg/kg [7]. So, the remaining residues of used agrochemicals above the MRL in agricultural products induce human health risks, such as cancer, skin diseases, and damage to the nervous system [8]. Thus, removing or degrading these residues is essential to overcome health issues.

Conventional industrial water washing, with or without chemical sanitizers, is commonly used to remove pesticide residues. However, forming by-products through these sensitizers affects the quality of products [9]. This chemical sanitation is banned in several countries because of the carcinogenic potential of its by-products [10], [11]. Trihalomethanes or chlorohyhydroxyfuranones are produced when HOCl and OCl combine with organic molecules, potentially causing human cancer due to cytotoxic and genotoxic [11].

Different novel food processing approaches have been developed to prevent product quality and post-harvest decay. Emerging sensitizer approaches such as plasma-activated liquids (PAL) are produced by exposure to plasma above or beneath the water or organic acids. PAL is eco-friendly and co-effective as compared to conventional disinfectants [12]. Earlier studies showed that energy efficiency decreased with increasing PAL activation time [3]. The effectiveness of PAL regarding pesticide degradation, it presents promising oxidative properties reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as H2O2, O2, O3, H2O+, OH− anion, (●OH radical), and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), including N2, NO, NO2, and NO3 [13], [14], [15]. Also, several biochemical reactions are triggered at the gas–liquid interface, and these reactive species are transferred to the liquids for producing broad-spectrum sanitizers. Literature suggests that PAL can inactivate many microorganisms and is exceptionally powerful in removing toxins from agricultural products without altering the taste, aroma, nutritional quality, physical attributes, and textural properties [16], [17], [18], [19].

Also, ultrasonication processing has been widely used in the food sector for different applications, such as decontamination and structural and functional component modifications. Ultrasonic processing in the food sector has revolutionized due to low-cost alternatives and eco-friendliness [20], [21], [22]. Integrating hurdle technologies for food processing has had improved results than individual applications [23], [24], [25]. Patil, Patil and Gogate [26] reported that ultrasound combined with the oxidation process effectively degraded dichlorvos pesticide, reducing the residual concentration to 3%. Earlier, Mu, Feng, Wei, Li, Cai and Zhu [27] stated that the sonication combined with an aqueous chlorine solution effectively removed nitrate content of up to 17.94% from spinach during 7 days storage period at 4 °C. Also, our previous study reported the potential of sonication combined with plasma activated water (PAW) and plasma-activated buffer solution (PABS) for reducing chlorothalonil fungicide on tomatoes immediately after washing with minimal effect on quality [3], [15]. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the fungicide degradation ability of sonication combined with PAW and PABS on tomatoes during storage. This research aimed to assess their impact on chlorothalonil residual reduction during 12 days storage period at 4 °C, along physicochemical and textural properties of the tomato fruits.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemical reagents

Chlorothalonil (C8Cl4N2, 99%), methanol (CH3OH, 99%), acetonitrile (CH3CN, 99%), hydrochloric acid (HCl), sulfamic acid (H3NO3S), sodium chloride (NaCl), hexane, magnesium sulfate (MgSO4), sulfanilamide, metaphosphoric-acetic acid (HPO3-CH3COOH) and N-(1-Naphthyl) ethylenediamine were acquired from Aladdin (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Sample preparation

Fresh organic tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) fruits were acquired from a local market in Guangzhou, Guangdong, China. Then fruits were washed with distilled water to remove the dust and dirt particles. Afterward, the fruits were contaminated with chlorothalonil solution (6 mg/L), soaked for 30 min, and dried at 25 °C for 5 h.

2.3. Activation of plasma-activated water and buffer solution

Atmospheric cold plasma prepared plasma-activated water (PAW) and plasma-activated buffer solution (PABS). The device comprises a ceramic electrode and a rotating nozzle with a plasma generator (50 kHz). A power source of 220 V AC was used with DC, having 2–7 kV and 600 W, an output voltage, and operating power to generate plasma, using atmospheric air as a gas.

PAW and PABS were prepared using distilled water and buffer solution containing 0.5 M potassium phosphate and sodium phosphate and placed 3 cm below the plasma jet for 5 and 10 min.

2.4. PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound treatments

Five tomato fruits were taken approximately the same size and weight for each treatment. In the individual treatments, tomato fruits were immersed in PAW and PABS for 15 min. For combined treatments, fruits were immersed in PAW and PABS and then placed in ultrasound (SB25-12D, Ningbo, China) bath cleaner with a 40 kHz frequency, 500 W output power for 15 min. The Schematic diagram of the experimental design is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup.

2.5. Storage study

The PAW, PABS, and combined ultrasound-treated samples were drained and packed in a polyethylene Ziploc bag (10 × 14 cm) and stored at 4 °C for 12 days in a refrigerator (BCD-525WKPZM9 (E), Hefei, China). The storage study period was designed based on initial trials and available literature. According to the literature, usually after harvesting, the shelf life of cherry tomato fruits is approximately 7 to 8 days [28]. Therefore, the maximum storage period of 12 days was adopted.

2.6. Chlorothalonil fungicide analysis

The treated samples' chlorothalonil fungicide residues were extracted using the QuEChERS method [3]. The well-homogenized 10 g samples were placed in a centrifuge tube (50 mL) with 10 mL acetonitrile, then further added 3 g of magnesium sulfate and 1 g of sodium chloride to the mixture. Afterward, the mixtures were well stirred and centrifuged (JW-3024HR, Hefei, China) for 5 min at 3500 rpm. After centrifugation, 3 mL of supernatant was taken into a centrifuge tube (10 mL) containing 50 g primary secondary amine (PSA) and centrifuged at 400 rpm for 2 min. Then 1 mL of the samples was used for HPLC analysis after filtration through a 0.22 µm filter syringe.

Chlorothalonil fungicide degradation was analyzed via an HPLC system (Waters, Singapore) coupled with a 2998 PDA detector at 227 nm for HPLC [3]. The following conditions were used: column temperature of 40 °C, a flow rate of 1 mL/min, injection volume of 20 µL, mobile phase including 70% methanol and 30% water. C18 (2.1 × 100 mm) analytical column with a particle size of 2.5 m (XBridge®, BEH, Ireland) was used.

The residual fungicide reduction from tomato fruits was calculated following the equation:

| (1) |

C0 and Cf are the initial and final concentrations (mg/kg) of chlorothalonil residue before and after treatment.

2.7. Determination of pH, total soluble solids (TSS), and titratable acidity (TA)

A digital pH meter was used to determine the pH of all samples (SP-2300, China), while a digital refractometer was used to determine the total soluble solids (TSS) concentration (PAL-1, Tokyo, Japan). The prism of the device was wiped thoroughly with water and then dried before each measurement.

10 g of tomato puree was diluted with 50 mL of distilled water to determine titratable acidity (TA). After filtering, 10 mL of the extract was titrated with 0.1 M NaOH, and phenolphthalein as an indicator was added [29].

2.8. Determination of color properties

The effect of treatments on the fruit's color was measured with a colorimeter (CR-400 Osaka, Japan). The color change was expressed in terms of whiteness/darkness (L*), redness or greenness (a*), yellowness or blueness (b*), and (ΔE) total color difference was calculated by the following equation.

| (2) |

where L*1 and L*2 are the initial and final lightness values, a*1 and a*2 are the initial and final redness and greenness values, and b*1 and b*2 are the initial and final yellowness or blueness values.

2.9. Determination of ascorbic acid and lycopene contents

The ascorbic acid content in tomatoes was measured according to Khalil, Moniruzzaman, Boukraâ, Benhanifia, Islam, Sulaiman and Gan [30], and Chang, Lin, Chang and Liu [31] methods with light modifications. The tomatoes were crushed and homogenized in a blender (DYL-D055, Guangzhou, China), and 3 g of the mixture was placed in a 50 mL centrifuge tube with 10 mL metaphosphoric acid solution and vortexed for 20 min, afterward filtered through Whatman filter paper (Hangzhou, China). 1 mL was taken from the filtrate and added 9 mL of 0.05 mM 2, 6-dichlorophenolindophenole, and then absorbance was measured at 515 nm using a spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Kyoto, Japan). Based on the calibration curve of L-ascorbic acid (10, 50, 100, 200, 300, and 400 µg/mL; Y = -2.2067, X = 0.243, R2 = 0.9839), the final concentration of ascorbic acid was determined and expressed as mg/100g of fresh fruit.

Lycopene content was determined by a prescribed method by Oliveira, Rodrigues and Fernandes [32] with slight modification. Briefly, 4 g of tomato puree was combined with 8 mL of hexane and centrifuged for 5 min at 300 rpm. The top layer was collected, and absorbance was measured at 503 nm with a spectrophotometer. The lycopene concentration was expressed as mg/kg of fresh fruit using a modified Beer-Lambert equation [33]:

| (3) |

where is mg/kg of lycopene, V is a volume of hexane (mL), W is a sample mass (g), A503 is a absorbance at 503 nm, is a molar extinction coefficient of lycopene in hexane (1.72 × 105 L/mol cm), and is a path length (1 cm).

2.10. Determination of textural profile

A textural profile analyzer (TA-XT plus, Surrey, UK) with (P/2) (2 mm in diameter) cylindrical probe was used, followed by a penetration distance of 20 mm and a test speed of 15 mm/min, specifically for the hardness, firmness, and skin elasticity of the whole fruits [3].

2.11. Statistical analysis

All the data were analyzed in triplicate, representing the results as mean ± SD. Analysis of variance ANOVA was performed, and the Tukey test was performed to calculate the significant differences between treatments and storage days (p < 0.05). The statistical analysis was carried out by Statistix 9 software (Analytical Software Tallahassee, FL, USA).

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Impact of PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound on fungicide degradation

The impact of PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound treatment on the fungicide degradation are shown in Table 1. The results showed that the fungicide residues significantly reduced (p ≤ 0.05) after treatments and during storage. The results stated that the PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound significantly reduced the fungicide residues than individual ultrasound treatment. The PAW10-U treatment caused a maximum reduction of fungicide residues among all treatments. On the other hand, at the end of the storage period, a maximum reduction of 97.26 % and 93.14% was observed in PAW10-U and PABS10-U, respectively. Results showed that the residual reduction rate was higher in the integrated treatments treated samples than in the PAW, PABS, and ultrasound. It could be assumed that the longer shelf life of reactive species and the synergistic effect of PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound, increased hydroxyl radicals during the storage period and degraded the pesticides. Studies revealed that the reduction of pesticides by plasma-activated liquids (PAL) could be associated with reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and their effect on the breakdown of the pesticide structures [3], [34], [35]. The formation of ROS and RNS such as ●OH, H2O2, O3, NO, NO2, and NO3 are the critical species for the decontaminating pesticides, which related to the collision of water molecules with intense electrons produced during plasma treatment leads to water molecule dissociation [35]. Earlier studies have proved that increasing the acidity, electrical conductivity, ROS, and RNS with increasing the PAL activation time enhances the reduction of fungicide residues, which is also observed in the current study [36], [37].

Table 1.

Effects of PAL combined ultrasound treatments on the degradation of fungicide residues from tomato fruits during storage.

| Treatments | Storage (Days) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | |

| D0 | 100.00 ± 1.43aA | 78.17 ± 1.88aB | 73.49 ± 1.51aBC | 68.55 ± 1.44aC | 61.56 ± 1.52aD |

| DW | 54.42 ± 1.76bA | 52.29 ± 188bA | 47.74 ± 1.29bB | 41.67 ± 2.34bC | 36.79 ± 1.65bD |

| DW-U | 51.11 ± 2.34bA | 47.35 ± 1.87bB | 40.05 ± 3.65bC | 36.50 ± 2.43bD | 32.91 ± 1.37bDE |

| PAW5 | 37.87 ± 1.63cA | 34.87 ± 1.41cAB | 27.58 ± 2.51cdC | 21.25 ± 1.52cD | 14.37 ± 3.87cE |

| PAW10 | 14.715 ± 1.83eA | 11.21 ± 1.84deB | 8.89 ± 1.91eC | 6.86 ± 1.81eD | 5.89 ± 1.11eD |

| PABS5 | 42.43 ± 2.76cA | 38.21 ± 2.88cB | 33.42 ± 2.51cC | 26.89 ± 3.44cD | 15.71 ± 2.52cE |

| PABS10 | 25.91 ± 3.44dA | 22.98 ± 1.69dAB | 17.63 ± 1.87dC | 15.18 ± 1.83dC | 10.86 ± 1.88cdD |

| PABS5-U | 36.04 ± 1.66cA | 34.38 ± 1.98cA | 31.41 ± 1.41cB | 24.89 ± 1.54cC | 12.90 ± 1.42cD |

| PABS10-U | 19.77 ± 1.34eA | 17.57 ± 2.59eA | 16.63 ± 1.05dA | 14.18 ± 2.63 dB | 6.86 ± 1.68eC |

| PAW5-U | 32.28 ± 2.53cdA | 30.66 ± 1.51cdA | 25.74 ± 3.41cdB | 19.25 ± 2.49cdC | 10.82 ± 1.77cdD |

| PAW10-U | 10.718 ± 1.43eA | 8.507 ± 2.84eB | 6.734 ± 1.91eC | 4.862 ± 1.71eD | 2.74 ± 1.70eE |

Note: D0 = Control, DW = Distilled water, DW-U = Distilled water + ultrasound, PAW = plasma-activated water, PABS = plasma-activated buffer solution, PAW-U = plasma-activated water + ultrasound, and PABS-U = plasma-activated buffer solution + ultrasound. Data presented as means ± SD. Different lowercase letters in the same column show significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments, while different uppercase letters in the same row present significant differences (p < 0.05) concerning storage days.

When the ultrasonic waves are combined with ozonation, it breaks down O3 into microbubbles and increases the solubility of O3 in the solution, which also could be responsible for pesticide degradation [38], [39]. The synergistic effect of PALs combined with ultrasound may generate hydroxyl radicals and improve the oxidation process [3], [40]. Turkish Food Codex-approved metalaxyl, thiamethoxam, and captan for use on tomatoes with MRL of 0.2, 0.2, and 1.0 mg kg−1. Cengiz, Başlar, Basançelebi and Kılıçlı [41] reported the maximum degradation efficiency of captan, thiamethoxam, and metalaxyl pesticides after ultrasound combined with the low electric current treatment up to 94.24, 69.80, and 95.06%, respectively. Wang, Zhu, Gong, Zhu, Huang, Xu, Ren, Han and He [38] investigated the impact of ultrasound combined with ozonation and reported the maximum degradation efficiency of acephate in water up to 87.60%. Zhang, Xiao, Chen, Ge, Wu and Hu [42] stated that apple juice's MRL of malathion and chlorpyrifos is 2–3 mg L-1. The authors reported that the maximum degradation efficiency of Malathion and chlorpyrifos after the ultrasonic wave's treatment was 41.70 and 82.0%, respectively. Earlier, Calvo, Redondo, Remón, Venturini and Arias [43] studied the impact of electrolyzed water and chlorine dioxide (ClO2) on cyprodinil, iprodione and tebuconazole residues in peach, with MRL ranging from 6.32 to 26. 11 g kg−1 during 15 days of storage. The outcomes revealed that ClO2 considerably reduced tebuconazole residues from all fruits with maximum degradation efficiency of 60%, and photocatalysis caused a maximum reduction of iprodione residues by 70%. In contrast, electrolyzed water reduced the concentration, like tap water, which never exceeded 40%. In addition, Rodrigues, de Queiroz, Neves, de Oliveira, Prates, de Freitas, Heleno and Faroni [44] evaluated the impact of ozone and detergent for the removal of azoxystrobin, difenoconazole and chlorothalonil fungicide from tomato fruits during storage with the MRL of 0.16 g L-1, 0.50 mL L-1 and 4.0 mL L-1, respectively, diluting in 1 L water. The results showed the highest reduction efficiency in samples treated with ozone, up to 90% for chlorothalonil and 77% for difenoconazole and azoxystrobin. Our results indicated that the PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound treatments effectively reduced the pesticide residues compared to the control sample. Moreover, our results reveal better degradation efficiency than the studies mentioned above, proving that PAW integrated with ultrasound is more effective for agrochemical degradation than other methods or techniques.

3.2. Impact of PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound on color properties of tomato fruit

During an evaluation of the impact of PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound on pesticide degradation, the quality characteristics of the tomato fruit after treatment are an essential index. The color L*, a*, b*, and total color difference (ΔE) values of the fruits after PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound treatments were presented in Table 2. Immediately after the treatments, the color value of the treated samples was analyzed, and the results showed a non-significant difference (p > 0.05). The samples treated with PAW combined with ultrasound showed promising results during storage compared to untreated samples. During the whole storage period, the treated sample exhibited low total color differences between 1.12 and 1.93. The findings of the color properties depend on the browning reaction and the decreases in anthocyanins in fruits [15], [45], [46]. Illera, Chaple, Sanz, Ng, Lu, Jones, Carey and Bourke [47] noticed a decrease in the color value of cold plasma-treated apple juice during storage. Kim, Kim and Kang [48] reported that some sanitizers altered the color of the tomato fruits during the storage period at 4–6 °C.

Table 2.

Effects of PAL combined ultrasound treatments on color values of tomato fruits during storage.

| Storage (Days) | Treatments |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DW | DW-U | PAW5 | PAW10 | PABS5 | PABS10 | PAW5-U | PAW10-U | PABS5-U | PABS10-U | |

| L* | ||||||||||

| 0 | 49.35 ± 0.30aA | 49.42 ± 0.06aA | 49.47 ± 0.13aA | 49.51 ± 0.71aA | 49.16 ± 0.34bA | 49.14 ± 1.23bA | 49.69 ± 0.47aA | 49.79 ± 0.51aA | 49.25 ± 0.81bC | 49.25 ± 0.58bA |

| 3 | 49.31 ± 0.12bA | 49.35 ± 0.05bA | 49.42 ± 0.08bA | 49.45 ± 0.23cA | 49.13 ± 0.21cA | 49.11 ± 0.98cA | 49.40 ± 0.48bB | 49.88 ± 0.44aA | 49.49 ± 1.25bA | 49.21 ± 0.32cA |

| 6 | 49.29 ± 0.06bA | 49.28 ± 0.04bA | 49.39 ± 0.09aA | 49.41 ± 0.47aA | 49.09 ± 0.41cA | 49.08 ± 0.11cA | 49.36 ± 0.57aB | 49.56 ± 0.43aB | 49.62 ± 0.72aA | 49.18 ± 0.34cA |

| 9 | 49.21 ± 0.14cA | 49.23 ± 0.12cA | 49.21 ± 0.87cB | 49.36 ± 0.19bAB | 49.03 ± 0.92cdA | 49.05 ± 1.13aA | 49.25 ± 0.44bB | 49.48 ± 0.30aB | 49.57 ± 0.35aA | 49.15 ± 0.51cA |

| 12 | 49.15 ± 0.39bA | 49.08 ± 0.11bB | 49.08 ± 0.32bC | 49.18 ± 0.16aB | 49.00 ± 0.32bB | 49.01 ± 0.15bA | 48.18 ± 0.32bBC | 49.11 ± 0.51bC | 49.42 ± 1.81aB | 49.11 ± 1.19bA |

| a* | ||||||||||

| 0 | 18.45 ± 0.74aA | 18.46 ± 0.84aA | 18.41 ± 0.12aA | 18.42 ± 0.45aA | 18.39 ± 0.39aA | 18.40 ± 0.27aA | 18.44 ± 0.67aA | 18.47 ± 0.49aA | 18.40 ± 0.85aA | 18.41 ± 0.16aA |

| 3 | 18.41 ± 2.27aA | 18.42 ± 0.82aA | 18.36 ± 0.06aA | 18.38 ± 0.89aA | 18.34 ± 0.48aA | 18.35 ± 0.14aA | 18.38 ± 0.03aAB | 18.43 ± 0.41aA | 18.36 ± 0.87aA | 18.37 ± 0.28aA |

| 6 | 18.34 ± 0.48aB | 18.36 ± 0.58aB | 18.29 ± 0.56aB | 18.33 ± 0.42aB | 18.29 ± 0.23aB | 18.30 ± 0.37aB | 18.27 ± 0.89aB | 18.37 ± 0.65aB | 18.29 ± 0.04aB | 18.33 ± 0.44aAB |

| 9 | 18.23 ± 0.31aC | 18.28 ± 0.86aC | 18.25 ± 0.20aB | 18.31 ± 0.12aB | 18.21 ± 0.46aC | 18.27 ± 0.28aB | 18.23 ± 0.14aB | 18.34 ± 0.01aB | 18.25 ± 0.68aB | 18.26 ± 0.61aB |

| 12 | 18.17 ± 0.62aD | 18.23 ± 0.99aC | 18.19 ± 0.57aBC | 18.28 ± 0.49aB | 18.18 ± 0.18aC | 18.21 ± 0.25aBC | 18.21 ± 0.69aB | 18.30 ± 0.87aBC | 18.20 ± 0.75aBC | 18.22 ± 0.69aB |

| b* | ||||||||||

| 0 | 12.36 ± 0.21aA | 12.35 ± 0.52aA | 12.31 ± 0.39aA | 12.32 ± 0.28aA | 12.29 ± 0.13aA | 12.30 ± 0.12aA | 12.32 ± 0.05aA | 12.35 ± 0.23aA | 12.33 ± 0.56aA | 12.31 ± 0.31aA |

| 3 | 12.33 ± 0.45aA | 12.30 ± 0.64aA | 12.29 ± 0.20aA | 12.21 ± 0.57aB | 12.18 ± 0.07aB | 12.20 ± 0.24aB | 12.22 ± 0.27aB | 12.28 ± 0.14aA | 12.27 ± 0.19aA | 12.25 ± 0.21aA |

| 6 | 12.31 ± 0.57aA | 12.25 ± 0.67aAB | 12.27 ± 0.17aA | 12.15 ± 0.29bBC | 12.11 ± 0.42bBC | 12.14 ± 0.10bBC | 12.21 ± 0.49abB | 12.22 ± 0.51aAB | 12.19 ± 0.46abB | 12.16 ± 0.54bB |

| 9 | 12.28 ± 0.18aA | 12.17 ± 0.43bC | 12.19 ± 0.10bAB | 12.09 ± 0.31cC | 12.09 ± 0.21cBC | 12.08 ± 0.25cC | 12.13 ± 0.57bcBC | 12.17 ± 0.91bB | 12.13 ± 0.36cBC | 12.08 ± 0.43aBC |

| 12 | 12.23 ± 0.28aAB | 12.11 ± 0.49abC | 12.15 ± 0.38abB | 12.00 ± 0.26cC | 12.01 ± 0.15cC | 12.03 ± 0.73cC | 12.05 ± 0.22cC | 12.08 ± 0.57abBC | 12.09 ± 0.61abBC | 12.03 ± 0.97aC |

| ΔE value | ||||||||||

| 0 | 1.08 ± 0.13eB | 1.93 ± 0.22bA | 1.68 ± 0.38cB | 1.38 ± 0.29 dB | 2.45 ± 0.16aA | 1.73 ± 0.21cA | 1.63 ± 0.18cC | 1.28 ± 0.26 dB | 1.68 ± 0.23cAB | 1.35 ± 0.11dA |

| 3 | 1.13 ± 0.09cdB | 1.53 ± 0.03bBC | 1.57 ± 0.21bB | 1.92 ± 0.13aA | 1.96 ± 0.18aB | 1.38 ± 0.13cB | 1.68 ± 0.09bBC | 1.58 ± 0.14bA | 1.87 ± 0.08aA | 1.23 ± 0.11cAB |

| 6 | 1.21 ± 0.12cAB | 1.57 ± 0.13bBC | 1.59 ± 0.19bB | 1.49 ± 0.09bB | 1.85 ± 0.12aB | 1.45 ± 0.17bB | 1.70 ± 0.03abBC | 1.12 ± 0.17aB | 1.55 ± 0.15bB | 1.15 ± 0.05cAB |

| 9 | 1.25 ± 0.13cA | 1.77 ± 0.16abB | 1.96 ± 0.11aA | 1.38 ± 0.04bB | 1.46 ± 0.06bC | 1.63 ± 0.09abA | 1.85 ± 0.08aA | 1.54 ± 0.07bA | 1.18 ± 0.11cC | 1.03 ± 0.04cB |

| 12 | 1.31 ± 0.02cA | 1.35 ± 0.07cC | 1.49 ± 0.05bB | 1.83 ± 0.06aA | 1.68 ± 0.11abBC | 1.30 ± 0.07cB | 1.93 ± 0.12aA | 1.70 ± 0.06abA | 1.93 ± 0.08aA | 1.37 ± 0.06cA |

Note: D0 = Control, DW = Distilled water, DW-U = Distilled water + ultrasound, PAW = plasma-activated water, PABS = plasma-activated buffer solution, PAW-U = plasma-activated water + ultrasound, and PABS-U = plasma-activated buffer solution + ultrasound. Data presented as means ± SD. Different lowercase letters in the same row show significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments, while different uppercase letters in the same column present significant differences (p < 0.05) concerning storage days.

3.3. Impact of PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound on pH, TSS, and TA of tomato fruit

Table 3 presents tomato fruits' pH, TSS, and TA values after PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound treatments and during storage. Immediately after the treatments and during storage, the pH values of all samples were analyzed, and the results showed a non-significant difference (p > 0.05). The results align with the previously reported study, where no significant effect was noticed in cabbage and tomato fruit after being individually treated with ultrasound and combined with chemicals [49].

Table 3.

Effects of PAL combined ultrasound treatments on pH, TSS, and titratable acidity of tomato fruits during storage.

| Storage (Days) | Treatments |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DW | DW-U | PAW5 | PAW10 | PABS5 | PABS10 | PAW5-U | PAW10-U | PABS5-U | PABS10-U | |

| pH values | ||||||||||

| 0 | 4.27 ± 0.01aA | 4.26 ± 0.01aA | 4.21 ± 0.02aA | 4.20 ± 0.04aA | 4.22 ± 0.01aA | 4.21 ± 0.26aA | 4.15 ± 0.01aA | 4.15 ± 0.02aA | 4.16 ± 0.02aA | 4.17 ± 0.11aA |

| 3 | 4.28 ± 0.09aA | 4.27 ± 0.05aA | 4.21 ± 0.04aA | 4.20 ± 0.07aA | 4.22 ± 0.03aA | 4.21 ± 0.08aA | 4.16 ± 0.05aA | 4.15 ± 0.07aA | 4.16 ± 0.02aA | 4.17 ± 0.03aA |

| 6 | 4.27 ± 0.07aA | 4.28 ± 0.03aA | 4.22 ± 0.08aA | 4.21 ± 0.09aA | 4.23 ± 0.08aA | 4.22 ± 0.09aA | 4.14 ± 0.05aA | 4.16 ± 0.04aA | 4.17 ± 0.05aA | 4.16 ± 0.02aA |

| 9 | 4.28 ± 0.56aA | 4.29 ± 0.07aA | 4.23 ± 0.15aA | 4.21 ± 0.02aA | 4.23 ± 0.12aA | 4.23 ± 0.11aA | 4.16 ± 0.15aA | 4.16 ± 0.08aA | 4.17 ± 0.11aA | 4.18 ± 0.07aA |

| 12 | 4.29 ± 0.11aA | 4.28 ± 0.08aA | 4.23 ± 0.13aA | 4.22 ± 0.04aA | 4.24 ± 0.31aA | 4.23 ± 0.05aA | 4.17 ± 0.12aA | 4.17 ± 0.09aA | 4.18 ± 0.21aA | 4.19 ± 0.02aA |

| Total soluble solids | ||||||||||

| 0 | 7.22 ± 0.36aBC | 7.21 ± 0.67aBC | 7.18 ± 0.08aB | 7.18 ± 0.11aB | 7.17 ± 0.18aBC | 7.19 ± 0.15aBC | 7.19 ± 0.36aBC | 7.20 ± 0.26aC | 7.21 ± 0.57aC | 7.21 ± 0.25aC |

| 3 | 7.52 ± 0.11bB | 7.33 ± 0.02dBC | 7.22 ± 0.07eB | 7.21 ± 0.07eB | 7.18 ± 0.14eBC | 7.18 ± 0.81eBC | 7.53 ± 0.06bB | 7.29 ± 1.38dBC | 7.73 ± 0.65aB | 7.43 ± 0.32cBC |

| 6 | 7.61 ± 0.85bB | 7.51 ± 0.41bB | 7.25 ± 0.13cB | 7.22 ± 0.09cB | 7.32 ± 0.06cB | 7.33 ± 0.72cB | 7.55 ± 0.43bB | 7.63 ± 0.49bB | 7.83 ± 0.15aB | 7.63 ± 0.32bB |

| 9 | 8.26 ± 1.12aA | 8.09 ± 0.41bA | 8.10 ± 0.06bA | 8.11 ± 0.12bA | 8.12 ± 0.21bA | 8.13 ± 0.28bA | 8.31 ± 0.61aA | 8.23 ± 0.81aA | 8.27 ± 0.81aA | 8.21 ± 0.31aA |

| 12 | 8.29 ± 0.45aA | 8.10 ± 0.52cA | 8.18 ± 0.04bA | 8.17 ± 0.14bA | 8.18 ± 0.11bA | 8.18 ± 0.10bA | 8.23 ± 0. 66abA | 8.31 ± 0.62aA | 8.33 ± 0.45aA | 8.32 ± 0.21aA |

| Titratable acidity | ||||||||||

| 0 | 0.47 ± 0.01bA | 0.48 ± 0.03bA | 0.50 ± 0.04aA | 0.51 ± 0.02aA | 0.49 ± 0.04bA | 0.50 ± 0.05aA | 0.55 ± 0.01aA | 0.59 ± 0.02aA | 0.53 ± 0.03aA | 0.56 ± 0.01aA |

| 3 | 0.43 ± 0.02bA | 0.45 ± 0.04bA | 0.47 ± 0.06abA | 0.48 ± 0.01abA | 0.46 ± 0.06bA | 0.45 ± 0.02abB | 0.49 ± 0.03aB | 0.53 ± 0.04aB | 0.47 ± 0.02aB | 0.51 ± 0.03aB |

| 6 | 0.37 ± 0.03cB | 0.40 ± 0.08cB | 0.41 ± 0.03cB | 0.44 ± 0.04bB | 0.42 ± 0.01bB | 0.40 ± 0.01cC | 0.43 ± 0.02bC | 0.48 ± 0.01aC | 0.42 ± 0.03bC | 0.46 ± 0.05aC |

| 9 | 0.31 ± 0.02cC | 0.35 ± 0.01bC | 0.39 ± 0.04aB | 0.38 ± 0.03abC | 0.37 ± 0.02bC | 0.34 ± 0.02cD | 0.39 ± 0.05aC | 0.42 ± 0.02aD | 0.37 ± 0.01bD | 0.40 ± 0.02aD |

| 12 | 0.26 ± 0.02cD | 0.29 ± 0.03bcD | 0.30 ± 0.05bC | 0.31 ± 0.06bD | 0.27 ± 0.04cD | 0.28 ± 0.03cE | 0.34 ± 0.04abD | 0.38 ± 0.01aD | 0.33 ± 0.04bD | 0.36 ± 0.03aD |

Note: D0 = Control, DW = Distilled water, DW-U = Distilled water + ultrasound, PAW = plasma-activated water, PABS = plasma-activated buffer solution, PAW-U = plasma-activated water + ultrasound, and PABS-U = plasma-activated buffer solution + ultrasound. Data presented as means ± SD. Different lowercase letters in the same row show significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments, while different uppercase letters in the same column present significant differences (p < 0.05) concerning storage days.

The results reveal that PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound after treatment non-significantly (p > 0.05) changed the TSS values, while a significant (p < 0.05) change was observed during storage. The increase in TSS value during storage might be related to the hydrolysis of sucrose [45]. It has been observed that sugars and acids are the primary substrates of the respiratory metabolism of fruits and vegetables. They are used up, causing the related changes occurring in TSS [50]. Sarangapani, O'Toole, Cullen and Bourke [51] observed a significant TSS increase in cold plasma-treated blueberries. Ma et al. [50] reported increased TSS values in Chinese bayberries' after being treated with PAW during 8-day storage. They revealed that it might be attributed to PAW treatment which caused a reduction in respiratory rate, reducing consumption of sugars and acids during storage.

The results describe that PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound after treatment non-significantly (p > 0.05) changed the TA, while a significant (p < 0.05) reduction was observed during storage. According to Khaliq, Mohamed, Ali, Ding and Ghazali [52], a decrease in TA in fruit could be related to the higher respiration and ripening rate, where sugar and organic acid could be used as substrates in the respiration process. Recently, Liu, Manzoor, Tan, Inam‐ur‐Raheem and Aadil [53] reported a decline in TA in fresh apple cuts after treatment with PAW during the storage time.

3.4. Impact of PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound on ascorbic acid and lycopene contents of tomato fruit

Fig. 2A presents tomato fruits' ascorbic acid values after PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound treatments and during storage. The results indicated a non-significant (p > 0.05) impact of all treatments at 0 days and during storage compared to a control sample. The results revealed that the reduction in ascorbic acid contents during storage emerged as 25.16 and 25.09 mg/100 g for PAW10-U and PABS10-U, respectively. The literature revealed that ascorbic acids are susceptible to processing and storage conditions. Wan et al. [54] observed a reduction in the ascorbic acid content of plasma-treated pears, carrots, and cucumbers. In addition, studies have shown that the Criegee process to form ozonide or the free radical mechanism via singlet oxygen is the most likely cause of ozone's ascorbic acid degradation. Sarangapani, O'Toole, Cullen and Bourke [51] stated that fresh-cut fruits treated with ozonation and UV-C exhibited a reduction in ascorbic acid concentration. Moreover, Min, Roh, Niemira, Boyd, Sites, Fan, Sokorai and Jin [55] reported that grape tomato aging is directly connected to decreasing ascorbic acid concentration throughout the storage period.

Fig. 2A.

Effect of PAW, PABS and combined with ultrasound on ascorbic acid of tomato fruits during storage. Data presented as means ± SD. Different lowercase letters show significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments, while different uppercase letters present significant differences (p < 0.05) concerning storage days.

The lycopene contents of tomato fruits after PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound treatments and during storage are presented in Fig. 2B. The results indicated a non-significant (p > 0.05) change after treatments and during storage. It might be due to the potential interactions between lycopene and various plasma reactive species, including singlet oxygen and peroxyl radicals, which overreact with lycopene, which might theoretically result in a drop in lycopene concentration [55], [56].

Fig. 2B.

Effect of PAW, PABS and combined with ultrasound on lycopene content of tomato fruits during storage. Data presented as means ± SD. Different lowercase letters show significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments, while different uppercase letters present significant differences (p < 0.05) concerning storage days.

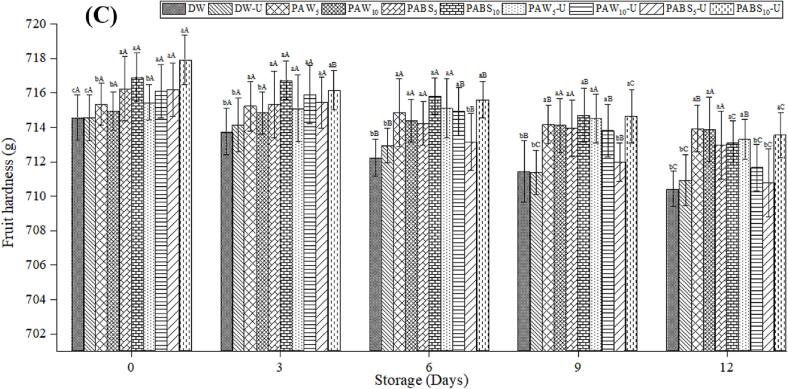

3.5. Textural properties of tomato

The textural properties of the fruit are an essential quality parameter for consumer acceptance. The textural properties of all samples after treatment and during storage were evaluated. Fig. 3A, Fig. 3B, Fig. 3C represent the skin elasticity, hardness, and firmness values. After the storage end, skin elasticity was 4.97 and 4.96 mm; fruit hardness was 711.67 and 713.55 g, and fruit firmness was 180.34 and 179.15 for PAW10-U and PABS10-U, respectively. The results indicated that the textural properties of the tomato fruits were slightly reduced during storage, but no significant difference was observed among treatments at 0 days. Liu, Manzoor, Tan, Inam‐ur‐Raheem and Aadil [53] reported similar firmness during the storage study of fresh apple cuts treated with PAW. The decrease in firmness might be due to cell leakage coupled with damage to the tissue surface [57]. The lower firmness with a non-significant difference has been observed in tomato fruits treated with sanitizers and combined with ultrasound treatment [58], low electrical current treatment [41], acidic electrolyzed water [59], and in-packaged atmospheric cold plasma treated grape tomato and in-packaged atmospheric cold plasma treated grape tomatoes [60]. In another study, a similar reduction in the hardness of tomato and apple fruits during storage study at 4 ℃ was determined after being treated with electrolyzed water, chemicals, ultrasound, and their combination [59]. Also, firmness decreases have been found for PAW-treated bayberries during 8 days of storage at 3 ℃ [50]. Likewise, 5 to 25 min ultrasound treatment affected the cherry tomatoes' firmness [61], and chemical sanitizer combined with ultrasound treatment on strawberry fruit during storage [45].

Fig. 3A.

Effect of PAW, PABS and combined with ultrasound on skin elasticity of tomato fruits during storage. Data presented as means ± SD. Different lowercase letters show significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments, while different uppercase letters present significant differences (p < 0.05) concerning storage days.

Fig. 3B.

Effect of PAW, PABS and combined with ultrasound on firmness of tomato fruits during storage. Data presented as means ± SD. Different lowercase letters show significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments, while different uppercase letters present significant differences (p < 0.05) concerning storage days.

Fig. 3C.

Effect of PAW, PABS and combined with ultrasound on hardness lycopene content of tomato fruits during storage. Data presented as means ± SD. Different lowercase letters show significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments, while different uppercase letters present significant differences (p < 0.05) concerning storage days.

4. Conclusions

Our study proposed the practical application of PAW, PABS and combined with ultrasound treatment for fungicide degradation. The maximum degradation of fungicide residues was 91.52, 89.14, 97.26 and 93.14% after treatment with PAW, PABS, PAW-U, and PABS-U, respectively. The concentration of the residues was lower as compared to control samples. PAL's solid oxidative capabilities and acidic nature, the presence of hydroxyl radicals formed during plasma and ultrasonic treatment, and the prolonged shelf life of hydroxyl radicals during storage were associated with the significant degradation of fungicide residues. Also, the results revealed no significant changes in the quality of tomato fruit samples after treatment and during storage. So, it can be concluded that PAW, PABS, and combined with ultrasound effectively degrade the pesticide residues with minimal impact on quality, even during storage, paving the way for up-scale plasma and ultrasound treatment at the industrial level.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Murtaza Ali: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Software. Jun-Hu Cheng: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Diana Tazeddinova: Writing – original draft, Data curation. Rana Muhammad Aadil: Writing – original draft, Data curation. Xin-An Zeng: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Gulden Goksen: Writing – original draft, Data curation. Jose Manuel Lorenzo: Writing – review & editing. Okon Johnson Esua: Writing – original draft, Data curation. Muhammad Faisal Manzoor: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Software.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors want to acknowledge the support of Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Intelligent Food Manufacturing, Foshan University, Foshan 528225, China (Project ID:2022B1212010015).

Funding for open access charges Cientisol, S.L.U., Av. do Cruceiro da Coruña, 14 bajo,15703, Santiago de Compostela (Spain).

Contributor Information

Jun-Hu Cheng, Email: fechengjh@scut.edu.cn.

Xin-An Zeng, Email: xazeng@scut.edu.cn.

Muhammad Faisal Manzoor, Email: faisaluos26@gmail.com, faisaluos26@fosu.edu.cn.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Manzoor M.F., Hussain A., Goksen G., Ali M., Khalil A.A., Zeng X.-A., Jambrak A.R., Lorenzo J.M. Probing the impact of sustainable emerging sonication and DBD plasma technologies on the quality of wheat sprouts juice. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;92 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J. In: Applications of Cold Plasma in Food Safety. Ding T., Cullen P.J., Yan W., editors. Springer Singapore; Singapore: 2022. Application of cold plasma in food packaging; pp. 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali M., Sun D.-W., Cheng J.-H., Esua O.J. Effects of combined treatment of plasma activated liquid and ultrasound for degradation of chlorothalonil fungicide residues in tomato. Food Chem. 2022;371 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mu Y., Feng Y., Wei L., Li C., Cai G., Zhu T. Combined effects of ultrasound and aqueous chlorine dioxide treatments on nitrate content during storage and postharvest storage quality of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) Food Chem. 2020;333 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biggel M., Jessberger N., Kovac J., Johler S. Recent paradigm shifts in the perception of the role of Bacillus thuringiensis in foodborne disease. Food Microbiol. 2022;105:104025. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2022.104025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziuzina D., Han L., Cullen P.J., Bourke P. Cold plasma inactivation of internalised bacteria and biofilms for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015;210:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.USDA, China releases new maximum residue limits for pesticides, Ministry of Agriculture China, Food and Drug Administration, (2017) 1-218.

- 8.Nejatifar F., Abdollahi M., Attarchi M., Roushan Z.A., Deilami A.E., Joshan M., Rahattalab F., Faraji N., Kojidi H.M. Evaluation of hematological indices among insecticides factory workers. Heliyon. 2022;8(3):e09040. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mir S.A., Dar B.N., Mir M.M., Sofi S.A., Shah M.A., Sidiq T., Sunooj K.V., Hamdani A.M., Mousavi Khaneghah A. Current strategies for the reduction of pesticide residues in food products. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022;106:104274. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnabel U., Niquet R., Schmidt C., Stachowiak J., Schlüter O., Andrasch M., Ehlbeck J. Antimicrobial efficiency of non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma processed water (PPW) against agricultural relevant bacteria suspensions. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Res. 2016;2:212–224. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iram A., Wang X., Demirci A. Electrolyzed oxidizing water and its applications as sanitation and cleaning agent. Food Eng. Rev. 2021;13:411–427. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esua O.J., Sun D.-W., Cheng J.-H., Li J.-L. Evaluation of storage quality of vacuum-packaged silver pomfret (Pampus argenteus) treated with combined ultrasound and plasma functionalized liquids hurdle technology. Food Chem. 2022;391 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cappato L.P., Ferreira M.V.S., Guimaraes J.T., Portela J.B., Costa A.L.R., Freitas M.Q., Cunha R.L., Oliveira C.A.F., Mercali G.D., Marzack L.D.F., Cruz A.G. Ohmic heating in dairy processing: Relevant aspects for safety and quality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017;62:104–112. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esua O.J., Cheng J.-H., Sun D.-W. Optimisation of Treatment Conditions for Reducing Shewanella putrefaciens and Salmonella Typhimurium on Grass Carp Treated by Thermoultrasound-Assisted Plasma Functionalized Buffer. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;76:105609. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali M., Cheng J.-H., Sun D.-W. Effect of plasma activated water and buffer solution on fungicide degradation from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit. Food Chem. 2021;350 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phan K.T.K., Phan H.T., Boonyawan D., Intipunya P., Brennan C.S., Regenstein J.M., Phimolsiripol Y. Non-thermal plasma for elimination of pesticide residues in mango. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018;48:164–171. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esua O.J., Cheng J.-H., Sun D.-W. Optimisation of treatment conditions for reducing Shewanella putrefaciens and Salmonella Typhimurium on grass carp treated by thermoultrasound-assisted plasma functionalized buffer. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;76 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahman M., Hasan M.S., Islam R., Rana R., Sayem A., Sad M.A.A., Matin A., Raposo A., Zandonadi R.P., Han H. Plasma-activated water for food safety and quality: A review of recent developments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:6630. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19116630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao Y., Francis K., Zhang X. Review on formation of cold plasma activated water (PAW) and the applications in food and agriculture. Food Res. Int. 2022;157:111246. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manzoor M.F., Ali M., Aadil R.M., Ali A., Goksen G., Li J., Zeng X.-A., Proestos C. Sustainable emerging sonication processing: Impact on fungicide reduction and the overall quality characteristics of tomato juice. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;94 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manzoor M.F., Hussain A., Sameen A., Sahar A., Khan S., Siddique R.…Xu B. Novel extraction, rapid assessment and bioavailability improvement of quercetin: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manzoor M.F., Ahmad N., Ahmed Z., Siddique R., Mehmood A., Usman M., Zeng X.A. Effect of dielectric barrier discharge plasma, ultra‐sonication, and thermal processing on the rheological and functional properties of sugarcane juice. J. Food Sci. 2020;85(11):3823–3832. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manzoor M.F., Zeng X.A., Rahaman A., Siddeeg A., Aadil R.M., Ahmed Z.…Niu D. Combined impact of pulsed electric field and ultrasound on bioactive compounds and FT-IR analysis of almond extract. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019;56:2355–2364. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03627-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faisal Manzoor M., Ahmed Z., Ahmad N., Karrar E., Rehman A., Muhammad Aadil R., Al-Farga A., Waheed Iqbal M., Rahaman A., Zeng X.A. Probing the combined impact of pulsed electric field and ultra-sonication on the quality of spinach juice. J. Food Process. Preservation. 2021;45:e15475. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed Z., Manzoor M.F., Hussain A., Hanif M., Zeng X.-A. Study the impact of ultra-sonication and pulsed electric field on the quality of wheat plantlet juice through FTIR and SERS. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;76 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patil A.L., Patil P.N., Gogate P.R. Degradation of imidacloprid containing wastewaters using ultrasound based treatment strategies. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21:1778–1786. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mu Y., Feng Y., Wei L., Li C., Cai G., Zhu T. Combined effects of ultrasound and aqueous chlorine dioxide treatments on nitrate content during storage and postharvest storage quality of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) Food Chem. 2020;333:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yadav A., Kumar N., Upadhyay A., Sethi S., Singh A. Edible coating as postharvest management strategy for shelf-life extension of fresh tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.): an overview. J. Food Sci. 2022;87(6):2256–2290. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.16145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bilek S.E., Değirmenci A., Tekin İ., Yılmaz F.M. Combined effect of vacuum and different freezing methods on the quality parameters of cherry tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum var. Cerasiforme) J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019;13:2218–2229. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khalil M., Moniruzzaman M., Boukraâ L., Benhanifia M., Islam M., Sulaiman S.A., Gan S.H. Physicochemical and antioxidant properties of Algerian honey. Molecules. 2012;17:11199–11215. doi: 10.3390/molecules170911199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang C.-H., Lin H.-Y., Chang C.-Y., Liu Y.-C. Comparisons on the antioxidant properties of fresh, freeze-dried and hot-air-dried tomatoes. J. Food Eng. 2006;77:478–485. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliveira V.S., Rodrigues S., Fernandes F.A. Effect of high power low frequency ultrasound processing on the stability of lycopene. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;27:586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esua O.J., Chin N.L., Yusof Y.A., Sukor R. Effects of simultaneous UV-C radiation and ultrasonic energy postharvest treatment on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of tomatoes during storage. Food Chem. 2019;270:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou R., Zhou R., Yu F., Xi D., Wang P., Li J., Wang X., Zhang X., Bazaka K., Ostrikov K.K. Removal of organophosphorus pesticide residues from Lycium barbarum by gas phase surface discharge plasma. Chem. Eng. J. 2018;342:401–409. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng Y., Wu S., Dang J., Wang S., Liu Z., Fang J., Han P., Zhang J. Reduction of phoxim pesticide residues from grapes by atmospheric pressure non-thermal air plasma activated water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019;377:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qi Z., Tian E., Song Y., Sosnin E.A., Skakun V.S., Li T., Xia Y., Zhao Y., Lin X., Liu D. Inactivation of shewanella putrefaciens by plasma activated water. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2018;38:1035–1050. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esua O.J., Cheng J.-H., Sun D.-W. Antimicrobial activities of plasma-functionalized liquids against foodborne pathogens on grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon Idella) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020;104:9581–9594. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10926-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang B., Zhu C.-P., Gong R.-H., Zhu J., Huang B.o., Xu F., Ren Q.-G., Han Q.-B., He Z.-B. Degradation of acephate using combined ultrasonic and ozonation method. Water Sci. Eng. 2015;8(3):233–238. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ali M., Manzoor M.F., Goksen G., Aadil R.M., Zeng X.-A., Iqbal M.W., Lorenzo J.M. High-intensity ultrasonication impact on the chlorothalonil fungicide and its reduction pathway in spinach juice. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;94:106303. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thokchom B., Pandit A.B., Qiu P., Park B., Choi J., Khim J. A review on sonoelectrochemical technology as an upcoming alternative for pollutant degradation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;27:210–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cengiz M.F., Başlar M., Basançelebi O., Kılıçlı M. Reduction of pesticide residues from tomatoes by low intensity electrical current and ultrasound applications. Food Chem. 2018;267:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y., Xiao Z., Chen F., Ge Y., Wu J., Hu X. Degradation behavior and products of malathion and chlorpyrifos spiked in apple juice by ultrasonic treatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2010;17(1):72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calvo H., Redondo D., Remón S., Venturini M.E., Arias E. Efficacy of electrolyzed water, chlorine dioxide and photocatalysis for disinfection and removal of pesticide residues from stone fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019;148:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodrigues A.A.Z., de Queiroz M.E.L.R., Neves A.A., de Oliveira A.F., Prates L.H.F., de Freitas J.F., Heleno F.F., Faroni L.R.D.A. Use of ozone and detergent for removal of pesticides and improving storage quality of tomato. Food Res. Int. 2019;125 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aday M.S., Caner C. Individual and combined effects of ultrasound, ozone and chlorine dioxide on strawberry storage life, LWT-Food. Sci. Technol. 2014;57:344–351. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ali M., Cheng J.H., Sun D.W. Effects of dielectric barrier discharge cold plasma treatments on degradation of anilazine fungicide and quality of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill) juice. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021;56:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Illera A., Chaple S., Sanz M., Ng S., Lu P., Jones J., Carey E., Bourke P. Effect of cold plasma on polyphenol oxidase inactivation in cloudy apple juice and on the quality parameters of the juice during storage. Food Chem.: X. 2019;3:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2019.100049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim S.H., Kim J.H., Kang B.-K. Decomposition reaction of organophosphorus nerve agents on solid surfaces with atmospheric radio frequency plasma generated gaseous species. Langmuir. 2007;23(15):8074–8078. doi: 10.1021/la700692t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mustapha A.T., Zhou C., Amanor-Atiemoh R., Ali T.A.A., Wahia H., Ma H., Sun Y. Efficacy of dual-frequency ultrasound and sanitizers washing treatments on quality retention of cherry tomato. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020;62:102348. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma R., Yu S., Tian Y., Wang K., Sun C., Li X., Zhang J., Chen K., Fang J. Effect of non-thermal plasma-activated water on fruit decay and quality in postharvest Chinese bayberries. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2016;9(11):1825–1834. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarangapani C., O'Toole G., Cullen P., Bourke P. Atmospheric cold plasma dissipation efficiency of agrochemicals on blueberries. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017;44:235–241. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khaliq G., Mohamed M.T.M., Ali A., Ding P., Ghazali H.M. Effect of gum arabic coating combined with calcium chloride on physico-chemical and qualitative properties of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit during low temperature storage. Sci. Hortic. 2015;190:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Z.W., Manzoor M.F., Tan Y.C., Inam-ur-Raheem M., Aadil R.M. Effect of dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma on the structure and antioxidant activity of bovine serum albumin (BSA) Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;55:2824–2831. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang R., Nian W., Wu H., Feng H., Zhang K., Zhang J., Zhu W., Becker K., Fang J. Atmospheric-pressure cold plasma treatment of contaminated fresh fruit and vegetable slices: inactivation and physiochemical properties evaluation. Eur. Phys. J. D. 2012;66:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Min S.C., Roh S.H., Niemira B.A., Boyd G., Sites J.E., Fan X., Sokorai K., Jin T.Z. In-package atmospheric cold plasma treatment of bulk grape tomatoes for microbiological safety and preservation. Food Res. Int. 2018;108:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manzoor M.F., Ahmad N., Ahmed Z., Siddique R., Zeng X.A., Rahaman A., Muhammad Aadil R., Wahab A. Novel extraction techniques and pharmaceutical activities of luteolin and its derivatives. J. Food Biochem. 2019;43:e12974. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tappi S., Berardinelli A., Ragni L., Dalla Rosa M., Guarnieri A., Rocculi P. Atmospheric gas plasma treatment of fresh-cut apples. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2014;21:114–122. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mustapha A.T., Zhou C., Amanor-Atiemoh R., Ali T.A., Wahia H., Ma H., Sun Y. Efficacy of dual-frequency ultrasound and sanitizers washing treatments on quality retention of cherry tomato. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020;62:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tango C.N., Khan I., Kounkeu P.-F.-N., Momna R., Hussain M.S., Oh D.-H. Slightly acidic electrolyzed water combined with chemical and physical treatments to decontaminate bacteria on fresh fruits. Food Microbiol. 2017;67:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Q., Niu Y., Xing P., Wang C. Bioactive polysaccharides from natural resources including Chinese medicinal herbs on tissue repair. Chin. Med. 2018;13:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13020-018-0166-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mustapha M.U., Halimoon N., Johar W.L.W., Abd Shukor M.Y. An overview on biodegradation of carbamate pesticides by soil bacteria. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2019;27:547–563. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.