Abstract

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the main food crops in the world and a primary source of zinc (Zn) and iron (Fe) in the human body. The genetic mechanisms underlying related traits have been clarified, thereby providing a molecular theoretical foundation for the development of germplasm resources. In this study, a total of 23,536 high-quality DArT markers was used to map quantitative trait loci (QTL) of grain Zn (GZn) and grain Fe (GFe) concentrations in recombinant inbred lines crossed by Avocet/Chilero. A total of 17 QTLs was located on chromosomes 1BL, 2BL, 3BL, 4AL, 4BS, 5AL, 5DL, 6AS, 6BS, 6DS, and 7AS accounting for 0.38–16.62% of the phenotypic variance. QGZn.haust-4AL, QGZn.haust-7AS.1, and QGFe.haust-6BS were detected on chromosomes 4AL, 6BS, and 7AS, accounting for 10.63–16.62% of the phenotypic variance. Four stable QTLs, QGZn.haust-4AL, QGFe.haust-1BL, QGFe.haust-4AL, and QGFe.haust-5DL, were located on chromosomes 1BL, 4AL, and 5DL. Three pleiotropic effects loci for GZn and GFe concentrations were located on chromosomes 1BL, 4AL, and 5DL. Two high-throughput Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR markers were developed by closely linking single-nucleotide polymorphisms on chromosomes 4AL and 5DL, which were validated by a germplasm panel. Therefore, it is the most important that quantitative trait loci and KASP marker for grain zinc and iron concentrations were developed for utilizing in marker-assisted breeding and biofortification of wheat grain in breeding programs.

Keywords: Wheat, Zinc, Iron, Quantitative trait loci, KASP marker

Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is a vital crop in the food production industry. Wheat grains contain various mineral elements, among which, zinc (Zn) and iron (Fe) have important clinical significance for global public health (Maathuis 2009; Nikwan et al. 2021). Malnutrition caused by mineral deficiencies afflicts > 2 billion people worldwide (Zhang and Gladyshev 2011; Stevens et al. 2013; Shivangi et al. 2021). Statistically, Zn deficiency threatens 17.3% of the world’s population and roughly 433,000 children under the age of 5 die every year due to Zn deficiency. Fe deficiency is the thirteenth greatest health risk factor in the world with 24.8% of the global population and > 65% of preschool children in Africa and Southeast Asia suffering from Fe deficiency anemia (Stevens et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2019). Many people in developing countries supplement Zn and Fe through the consumption of wheat foods. Genetic modification is the primary method by which grain Zn (GZn) and grain Fe (GFe) concentrations are increased and have become an increasingly popular area of research in crop science (Xue et al. 2012).

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, while GZn and GFe concentrations’ harvestplus in wheat was being promoted, different researchers presented various findings (Ryan et al. 2010). In earlier years, researchers were focused on increasing agricultural production. Kutman et al. (2011) showed that nitrogen (N) supply improved the rhizosphere environment of wheat and changed the rhizosphere morphology, thereby facilitating Zn and Fe absorption by the root system, which is then transferred to the grains. Ryan et al. (2010) found that phosphorous (P) fertilizer application had different effects on Zn and Fe absorption when compared to N fertilizer. If the P concentration in the soil was too high, Zn transport was inhibited. Srivastava et al. (2015) showed that potassium (K) application significantly enhanced Zn absorption in wheat grains and straws. Furthermore, Jalal et al. (2020) found that GZn and GFe concentrations significantly increased after spraying Zn and Fe fertilizer on plant leaves. However, these traditional fertilization methods are costly and easily poison the soil and plants. Currently, the safest and most effective method for addressing Zn and Fe deficiencies in humans is breeding Zn- and Fe-rich wheat varieties.

Recently, after the publication of the Chinese Spring Reference Genome, several gene loci related to GZn and GFe concentrations have been mined through linkage analyses and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) (Rasheed et al. 2017; Velu et al. 2019; Tong et al. 2020). Specifically, Crespo-Herrera et al. (2016) detected three main quantitative trait loci (QTL) for GZn concentrations and three for GFe concentrations on chromosomes 4B and 7D using recombinant inbred line (RIL) populations of spring wheat, which accounted for 10.7–19.6% of the phenotypic variation. Velu et al. (2016) detected two major QTLs for GZn concentrations and three for GFe concentrations on chromosomes 1B, 3A, 5B, and 6B using a total of 105 tetraploid RILs, which accounted for 10.6–16.9% of the phenotypic variation. In a separate study, eight major QTLs for GZn concentrations and four for GFe concentrations were detected on chromosomes 1B, 1D, 2B, 3A, 3D, 6B, 7A, and 7B using a total of 127 hexaploid RILs, which accounted for 10.0–31.0% of the phenotypic variation. Wang et al. (2021) detected one major QTL for GZn concentrations and one for GFe concentrations on chromosome 4D, which was a pleiotropic QTL. Liu et al. (2019) detected 1 major QTL for GZn concentrations and 2 for GFe on chromosomes 2B, 3B, and 5A, which accounted for 10.8–14.6% of the phenotypic variation. Rathan et al. (2021) identified seven new pleiotropic QTL for GZn and GFe concentrations on chromosomes 1B, 1D, 2B, 6A, and 7D. Genc et al. (2009) detected four major QTLs for GZn concentrations on chromosomes 3D, 4B, 6B, and 7A using a doubled haploid population. Each QTL exerted little effect but the aggregation of four high Zn alleles increased GZn concentrations by 23%.

Several pieces of research have proven very effective in increasing Zn and Fe content by wheat breeding method (Shivangi et al. 2021). Based on advancements using different populations for gene mapping, several QTLs that control GZn and GFe concentrations have been identified; however, the number of cloned genes is relatively scarce. Therefore, in this study, a genetic analysis was carried out using new populations to serve as a reference for the mining of effective candidate genes in future studies. The high-density maps were constructed to mine important QTLs and develop molecular markers that can be used for breeding and are of great significance for the genetic improvement of GZn and GFe concentrations’ nutritional quality. Thus, we aimed to identify QTLs for GZn and GFe concentrations using a total of 164 RILs derived from Avocet/Chilero. This study provides a theoretical basis and technical support for high Fe and Zn concentrations by utilizing wheat biotechnological breeding.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

A total of 164 F6 RILs derived from crossing Avocet/Chilero were used for the QTL mapping of GZn and GFe concentrations. The population was developed by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) with a single seed descent approach described (Basnet et al. 2014), and was used previously to characterize leaf rust, stripe rust resistance, and fructan content (Ponce-Molina et al.2018; Zeng et al. 2020). A germplasm panel, including 54 domestic and 97 foreign germplasm resources, was used to validate QTLs for GZn and GFe concentrations. Materials were provided by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and the wheat germplasm innovation and molecular breeding project of Henan University of Science and Technology, China.

Field trials

The RIL population was tested under a total of three environments in three sites. Field trials were conducted in the experimental field at the Agricultural College of Henan University of Science and Technology (E1; 34°62′N, 112°45′E; the concentrations of alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, available zinc, and available iron were 64.75 mg kg−1, 1.73 mg kg −1, and 4.21 mg kg −1 respectively) during the 2019–2020 cropping seasons, Luoning (E2; 34°38′N, 111°65′E; the concentrations of alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, available zinc, and available iron were 60.08 mg kg −1, 1.48 mg kg −1, and 6.23 mg kg −1 respectively) during the2019–2020 cropping seasons, and Mengjin (E3; 34°49′N, 112°26′E; the concentrations of alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, available zinc, and available iron were 55.85 mg kg −1, 1.36 mg kg −1, and 5.83 mg kg −1 respectively) during the2020–2021 cropping seasons in Henan Province, China. Each plot consisted of 2 m rows that were spaced 25 cm. The experiment was arranged in a randomized block design with three replicates. Standard agronomic wheat management practices were applied without using fertilizers to avoid the effect of additional fertilizers on the actual Zn and Fe concentrations. There were no serious pests or diseases and lodging throughout the entire growth period.

Measuring of grain Zn and Fe concentrations

After wheat plants matured, we randomly selected normal grains weighing ~ 5 g, placed the samples in a paper bag, and oven-dried the grains at 80 °C to a constant weight. Dried samples were crushed with a tungsten carbide ball mill (MM 400; Retsch, Haan, Germany) to obtain whole wheat flour. Whole wheat flour weighing 0.2 g was placed in a digestion tube, to which, 5 mL HNO3 (analytical grade) and 1 mL H2O2 (analytical grade) were added. Samples were digested in a microwave digestion machine (Multiwave PRO; Anton Paar, Shanghai, China) until no visible tissue pieces were left in the tube. After cooling, the volume was fixed to 25 mL. An inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometer (5110 ICP-OES; Agilent, CA, USA) was used to determine the GZn and GFe concentrations (Lu et al. 2010; Vijay et al. 2009). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and normal distribution tests were performed using IciMapping v4.1 (http://www.isbreeding.net) and SPSS v21.0 (IBM Inc., Chicago, USA) (Meng et al. 2015; Yan et al. 2013). Student’s t-test was used to calculate whether there were significant differences among different genotypes in germplasm panels (Velu et al. 2014). Broad-sense heritability (h2) was estimated using the following equation which was calculated following Holland et al. (2003): h2 = δ2/(δg2 + δg2×e/e), where δg2 = [(MSRIL-MSRIL×e)/e], δg2×e = MSRIL×e, g represents the number of varieties, e represents the environments, and MS represents the mean square.

Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping analysis

DArT markers covering the whole wheat genome with a total of 23,536 detection probes were used in this study, which were measured by Triticarte Co., Ltd. (Canberra, Australia). The molecular marker data was provided by Dr. Ravi P. Singh’s team of CIMMYT.

QTL mapping

Statistical processing of the markers was performed using Excel 2010 (Microsoft, WA, USA) to screen polymorphic markers with deletion rates < 10% and minimum alleles > 30%. IciMapping v4.1 software was used to construct the linkage maps and conduct the QTL analysis (Li et al. 2010; Wang 2009). JoinMap v4.0 (https://joinmap.software.informer.com) was used to calibrate the genetic lengths and obtain the final genetic map (Zeng et al. 2020). QTL mapping was performed by inclusive composite interval mapping (ICIM). The linkage marker sequence was compared to the Chinese Spring Reference Genome to obtain the physical location of the marker. Physical maps for the positional comparisons of GZn and GFe concentrations QTLs with previous reports were visualized using MapChart v2.3 (https://mapchart.net) (Velu et al. 2016).

Conversion of SNPs to Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP) markers

SNPs closely linked to the target QTLs were transformed into KASP markers. PolyMarker (http://www.polymarker.info/) was used to design KASP primers (Wang et al. 2021). A fluorescent quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR instrument (C1000 Touch; Bio-Rad, CA, USA) was used for gel-free fluorescent signal scanning and allele separation (Chandra et al. 2017). KASP reaction procedures were conducted following previously described methods (Rasheed et al. 2016).

Results

Phenotypic evaluation

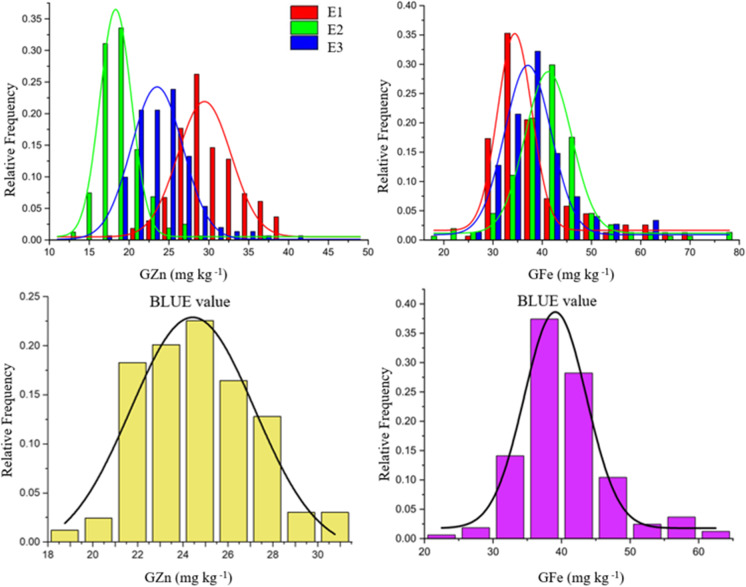

Concentrations and variation ranges of GZn and GFe concentrations in the RIL population and the parental lines are provided in Table 1. There was a significant difference between the GFe concentrations of Avocet and Chilero, where the GFe concentrations of Avocet were higher than Chilero in three environments and there were significant differences between the GFe concentrations of the RILs. There were no significant differences between the GZn concentrations of Avocet and Chilero in three environments, but the GZn concentrations among the RILs differed considerably. Thus, it was inferred that the GZn concentration is a quantitative trait controlled by polygenes. GZn and GFe concentrations in the RIL population had a continuous normal distribution (Fig. 1). Results showed that genotype, environment, and their interactions had significant effects on the GZn and GFe concentrations in the RIL population. Both GZn and GFe concentrations had a heritability of 55% (Table 2).

Table 1.

Mean and range of GZn and GFe concentrations (mg kg−1) in the Avocet/Chilero population among three environments

| Trait | Environment | Parents | RILs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avocet | Chilero | Range | Mean ± SD | ||

| GZn (mg kg−1) | E1 | 28.68 | 28.28 | 21.47–39.28 | 30.16 ± 3.91 |

| E2 | 18.80 | 19.53 | 13.62–36.77 | 19.14 ± 3.02 | |

| E3 | 19.15 | 19.33 | 17.53–40.74 | 24.21 ± 3.77 | |

| GFe (mg kg −1) | E1 | 36.74 | 30.70 | 26.08–69.77 | 38.47 ± 8.81 |

| E2 | 57.91 | 49.59 | 18.00–78.71 | 41.50 ± 8.32 | |

| E3 | 44.78 | 37.01 | 26.88–63.92 | 38.67 ± 7.28 | |

Fig. 1.

Distribution of wheat GZn and GFe concentrations in the Avocet/Chilero RIL population

Table 2.

Analysis of variance of GZn and GFe concentrations in the Avocet/Chilero RILs population

| Trait | Source of variation | DF | SS | MS | F value | P value | h2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GZn | Genotype (G) | 163 | 12,197.96 | 74.83 | 6.74 | 0.00** | 55% |

| Environment (E) | 2 | 132,457.80 | 66,228.90 | 5965.05 | 0.00** | ||

| Replicate (E) | 2 | 52.74 | 17.58 | 1.58 | 0.19 | ||

| G × E | 308 | 16,053.00 | 52.12 | 4.69 | 0.00** | ||

| GFe | Genotype | 163 | 72,524.34 | 444.93 | 15.37 | 0.00** | 55% |

| Environment | 2 | 245,213.91 | 122,606.95 | 4235.14 | 0.00** | ||

| Replicate (E) | 2 | 261.18 | 87.06 | 3.01 | 0.03* | ||

| G × E | 308 | 103,876.50 | 341.70 | 11.80 | 0.00** |

* and ** indicate significance at P < 0.05 and 0.01

Linkage map construction

Of the 23,536 DArT markers (genotypic data is available for the RILs), 3290 polymorphic molecular markers were used to construct the genetic linkage map. The map covered 15,281.85 cM, and the average genetic distance was 4.64 cM. Except for group 4 consisting of homoeologous chromosomes, the number of markers for other groups was roughly the same. Chromosome 4D had the least label coverage with 41 linkage markers and chromosome 6B had the most with 266 linkage markers. Chromosome 4D had the longest average genetic distance of 8.68 cM and chromosome 3B had the shortest at 3.71 cM (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of DArT markers in the linkage map on the chromosomes in the Avocet/Chilero RILs population

| Chromosome | Marker number | Genetic length/cM | Average density of markers/cM | Chromosome | Marker number | Genetic length/cM | Average density of markers/cM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | 184 | 785.50 | 4.27 | 6B | 266 | 1095.01 | 4.12 |

| 1B | 175 | 702.65 | 4.02 | 6D | 92 | 641.21 | 6.97 |

| 1D | 86 | 563.96 | 6.56 | 7A | 214 | 918.82 | 4.29 |

| 2A | 120 | 660.15 | 5.50 | 7B | 200 | 833.71 | 4.17 |

| 2B | 238 | 932.18 | 3.92 | 7D | 121 | 714.42 | 5.90 |

| 2D | 102 | 677.35 | 6.64 | Group 1 | 445 | 2052.11 | 4.61 |

| 3A | 204 | 773.02 | 3.79 | Group 2 | 460 | 2269.68 | 4.93 |

| 3B | 238 | 883.60 | 3.71 | Group 3 | 545 | 2287.95 | 4.20 |

| 3D | 103 | 631.33 | 6.13 | Group 4 | 367 | 1619.49 | 4.41 |

| 4A | 211 | 801.94 | 3.80 | Group 5 | 467 | 2126.15 | 4.55 |

| 4B | 115 | 461.49 | 4.01 | Group 6 | 471 | 2459.52 | 5.22 |

| 4D | 41 | 356.06 | 8.68 | Group 7 | 535 | 2466.95 | 4.61 |

| 5A | 210 | 831.55 | 3.96 | A genome | 1256 | 5494.28 | 4.37 |

| 5B | 194 | 759.73 | 3.92 | B genome | 1426 | 5668.37 | 3.98 |

| 5D | 63 | 534.87 | 8.49 | D genome | 608 | 4119.20 | 6.78 |

| 6A | 113 | 723.30 | 6.40 | Total | 3290 | 15,281.85 | 4.64 |

QTL mapping of GZn and GFe concentrations

A total of 10 QTLs of GZn concentrations were located on chromosomes 1B, 2B, 3B, 4A, 4B, 5A, 5D, 6A, and 7A, and identified in different environments (Fig. 2; Table 4). The identified QTLs were designated as QGZn.haust-1BL, QGZn.haust-2BL, QGZn.haust-3BL, QGZn.haust-4AL, QGZn.haust-4BS, QGZn.haust-5AL, QGZn.haust-5DL, QGZn.haust-6AS, QGZn.haust-7AS.1, and QGZn.haust-7AS.2, accounting for 1.07–14.67% of the phenotypic variation. The favorable alleles of QGZn.haust-1BL, QGZn.haust-3BL, QGZn.haust-4BS, QGZn.haust-5AL, QGZn.haust-5DL, QGZn.haust-6AS, and QGZn.haust-7AS.2 originated (Fig. 3) from Avocet and the phenotypic variation of each QTL was < 10%. QGZn.haust-2BL, QGZn.haust-4AL, and QGZn.haust-7AS.1 exhibited decreasing GZn. The phenotypic variation of QGZn.haust-4AL and QGZn.haust-7AS.1 was 11.87% and 16.62%, respectively, indicating that they are major QTLs (Fig. 4). QGZn.haust-4AL was bound to the DArT marker interval SNP100512195–1,721,210 with a physical interval ranging from 720.1–731.0 Mb and was detected in two of the three environments, indicating that it is a stable major QTL for controlling GZn concentrations.

Fig. 2.

Landscape of genetic architecture underlying Fe- and Zn-related traits in wheat. Genetic loci for Fe and Zn traits identified from wheat orthologs of Arabidopsis and rice genes, QTL mapping, association studies, and cloned wheat genes are displayed in black, red, green, blue, and purple, respectively. Yellow bars within chromosomes indicate the physical interval of QTL, QTL associated with both Fe and Zn are underlined

Table 4.

QTL mapping for GZn and GFe concentrations identified by inclusive composite interval mapping in the Avocet/Chilero population

| Trait | QTL | Environment | Physical interval | Marker interval | LOD | PVE (%) | Favorable allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GZn | QGZn.haust-1BL | E3 | 554.7–635.1 | 2,268,342–SNP100598436 | 5.70 | 3.78 | Avocet |

| QGZn.haust-2BL | E2 | 690.8–758.9 | SNP1063621–1,367,534 | 3.25 | 3.70 | Chilero | |

| QGZn.haust-3BL | E1 | 793.5–802.3 | 1,116,594–3,032,800 | 2.63 | 3.84 | Avocet | |

| QGZn.haust-4AL | E1 | 720.1–731.0 | SNP100512195–1,721,210 | 7.75 | 11.87 | Chilero | |

| QGZn.haust-4AL | E3 | 720.1–731.0 | SNP100512195–1,721,210 | 8.90 | 3.57 | Chilero | |

| QGZn.haust-4BS | E1 | 44.9–89.9 | 3,955,627–1,124,059 | 3.75 | 5.44 | Avocet | |

| QGZn.haust-5AL | E3 | 579.4–593.1 | 4,542,455–4,537,534 | 3.12 | 3.22 | Avocet | |

| QGZn.haust-5DL | E3 | 432.8–554.8 | 4,440,045–4,989,564 | 3.63 | 3.76 | Avocet | |

| QGZn.haust-6AS | E3 | 23.6–48.0 | SNP1127808–SNP1057803 | 2.70 | 1.07 | Avocet | |

| QGZn.haust-7AS.1 | E2 | 50.6–51.8 | 1,102,565–3,940,544 | 14.67 | 16.62 | Chilero | |

| QGZn.haust-7AS.2 | E2 | 49.6–50.0 | 2,253,164–1,130,512 | 8.17 | 8.05 | Avocet | |

| GFe | QGFe.haust-1BL | E1 | 554.7–635.1 | 2,268,342–SNP100598436 | 4.93 | 3.15 | Avocet |

| QGFe.haust-1BL | E3 | 554.7–635.1 | 2,268,342–SNP100598436 | 6.37 | 2.50 | Avocet | |

| QGFe.haust-2BL | E1 | 593.6–690.7 | SNP2351705–SNP1063621 | 12.44 | 3.28 | Avocet | |

| QGFe.haust-4AL | E1 | 720.1–731.0 | SNP100512195–1,721,201 | 12.28 | 3.25 | Chilero | |

| QGFe.haust-4AL | E2 | 720.1–731.0 | SNP100512195–1,721,201 | 10.62 | 0.38 | Chilero | |

| QGFe.haust-4AL | E3 | 720.1–731.0 | SNP100512195–1,721,201 | 12.41 | 2.58 | Chilero | |

| QGFe.haust-5AL | E3 | 666.9–680.4 | SNP1137615–4,541,384 | 2.62 | 0.68 | Avocet | |

| QGFe.haust-5DL | E1 | 432.8–554.8 | 4,440,045–4,989,564 | 6.61 | 3.17 | Avocet | |

| QGFe.haust-5DL | E2 | 432.8–554.8 | 4,440,045–4,989,564 | 8.60 | 0.38 | Avocet | |

| QGFe.haust-5DL | E3 | 432.8–554.8 | 4,440,045–4,989,564 | 2.59 | 0.82 | Avocet | |

| QGFe.haust-6BS | E2 | 32.7–39.4 | 1,044,528–986,510 | 10.52 | 10.63 | Chilero | |

| QGFe.haust-6DS | E3 | 18.7–30.2 | 3,027,965–4,405,040 | 4.39 | 2.64 | Avocet |

Fig. 3.

Genotyping of KASP molecular marker in the germplasm

A total of 7 QTLs of GFe concentrations were located on chromosomes 1B, 2B, 4A, 5A, 5D, 6B, and 6D, and were identified in different environments (Fig. 2; Table 4). The identified QTLs were designated as QGFe.haust-1BL, QGFe.haust-2BL, QGFe.haust-4AL, QGFe.haust-5AL, QGFe.haust-5DL, QGFe.haust-6BS, and QGFe.haust-6DS, accounting for 0.38–10.63% of the phenotypic variation. QGFe.haust-1BL, QGFe.haust-2BL, QGFe.haust-5AL, QGFe.haust-5DL, and QGFe.haust-6DS exhibited increasing GFe concentrations. The favorable alleles originated from Avocet and the phenotypic variation of each QTL was < 10%. The phenotypic variation of QGFe.haust-6BS was 10.63%, respectively, indicating that it is a major QTL. QGFe.haust-1BL was bound to the DArT marker interval 2,268,342–SNP100598436 with a physical interval ranging from 554.7 to 635.1 Mb and was detected in two of the three environments. QGFe.haust-4AL and QGFe.haust-5DL were bound to the DArT marker intervals SNP100512195–1,721,201 and 4,440,045–4,989,564 with physical intervals ranging from 720.1 to 731.0 and 432.8 to 554.8 Mb, respectively, and were detected in three environments. These findings indicated that the 3 loci were stable major QTLs for controlling GFe concentrations (Fig. 4).

QGZn.haust-1BL and QGFe.haust-1BL were detected on the same locus in E3 and exhibited increasing GZn and GFe concentrations. QGZn.haust-4AL and QGFe.haust-4AL were detected on the same loci in E1 and E3, and exhibited decreasing GZn and GFe concentrations. QGZn.haust-5DL and QGFe.haust-5DL were detected on the same locus in E3 and exhibited increasing GZn and GFe concentrations. The 3 loci were pleiotropic (Table 5).

Table 5.

Chromosomal intervals for GZn and GFe concentrations identified by multi-trait composite interval mapping (MCIM)

| Chromosomes | Flanking markers | Physical position (Mb) | Traits (environment) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1BL | 2,268,342–SNP100598436 | 554.7–635.1 | GZn (E3) |

| GFe (E1, E3) | |||

| 4AL | SNP100512195–1,721,201 | 720.1–731.0 | GZn (E1, E3) |

| GFe (E1, E2, E3, BLUE value) | |||

| 5DL | 4,440,045–4,989,564 | 432.8–554.8 | GZn (E3) |

| GFe (E1, E2, E3) |

QTL pyramids and validation

The chip markers located on the 1BL chromosome could not be converted into specific markers. The flanking SNPs of the pleiotropic loci (QGZn.haust-4AL and QGFe.haust-4AL; QGZn.haust-5DL and QGFe.haust-5DL) located on chromosomes 4AL and 5DL were converted into KASP markers, named Kasp_4A_QGZnFe and Kasp_5D_QGZnFe (Table 6). The markers were used to detect genotypes in the germplasm panels. Research indicates that both Kasp_4A_QGZnFe and Kasp_5D_QGZnFe had obvious genotypes in the germplasm panels (Fig. 3). Among the 151 germplasm panels, there was no significant difference (P < 0.05) in GZn and GFe concentrations between the two genotypes of Kasp_4A_QGZnFe (Table 7). The number of germplasm panels carrying the CC (Avocet) and GG (Chilero) genotypes was 41 (27.2%) and 110 (72.8%) for Kasp_5D_QGZnFe; the GZn and GFe concentrations of the CC genotype were significantly higher than the GG genotype with mean differences of 3.57 and 3.01 mg kg −1, respectively (Table 7). The frequency of germplasm carrying favorable allelic variants of CC was lower than GG allele, indicating that the pleiotropic loci (QGZn.haust-5DL and QGFe.haust-5DL) have considerable application value in breeding.

Table 6.

The designed primer sequence of KASP molecular marker in this study

| Chromosome | SNP name | KASP name | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4AL | SNP100512195 | Kasp_4A_QGZnFe |

5’-GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTTGACTAGGCTATTGCAGAAAGATT-3’ 5’-GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGACTAGGCTATTGCAGAAAGATC-3’ 5’-TTGGTTGGAGTTGCTAGGGC-3’ 5’-GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTATGAGTCGCCACCAGGGATC-3’ |

| 5DL | SNP1229622 | Kasp_5D_QGZnFe |

5’-GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTATGAGTCGCCACCAGGGATG-3’ 5’-GTCATTTGTGGCAGCTGCAG-3’ |

Table 7.

Mean values of GZn and GFe concentrations for genotype classes in the germplasm panel

| Trait | QTL | Marker | Genotype | Number | Mean (mg kg −1) | T value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GZn | QGZn.haust-4AL | SNP100512195 | TT | 89 | 37.72 | 0.83 |

| CC | 62 | 37.67 | ||||

| QGZn.haust-5DL | SNP1229622 |

CC GG |

41 110 |

40.40 36.83 |

0.007* | |

| GFe | QGFe.haust-4AL | SNP100512195 | TT | 89 | 40.39 | 0.15 |

| CC | 62 | 40.58 | ||||

| QGFe.haust-5DL | SNP1229622 |

CC GG |

41 110 |

43.38 40.37 |

0.047* |

* and ** indicate significance at P < 0.05 and 0.01

Discussion

Methods for increasing GZn and GFe concentrations

The GZn and GFe concentrations in wheat can be increased through several methods (Kopittke et al. 2018). Kutman et al. (2011) showed that the application of N fertilizer improved GZn and GFe concentrations in wheat. Srivastava et al. (Srivastava et al. 2015) showed that K fertilizer application improved GZn absorption in wheat. Furthermore, Ryan et al. (2010) found that P fertilizer inhibited the absorption of GZn and GFe concentrations in wheat. However, GZn and GFe concentrations are mainly absorbed from and accumulate in the soil, and the Zn and Fe contents in the soil that can be absorbed and transformed by plants are generally low. Therefore, only applying NPK fertilizer to improve GZn and GFe concentrations is inefficient and could easily cause soil toxicity. Jalal et al. (2020) found that the foliar application of ZnSO4·7H2O and FeSO4 increased GZn and GFe concentrations in wheat. An (2011) demonstrated that the combination of spraying Zn and bulk element fertilizers effectively improved crop yields and the GZn concentrations when compared to spraying Zn fertilizer alone. Although the application of Zn and Fe fertilizers increases the GZn and GFe concentrations, their cost is too high, and excessive Zn and Fe lead to toxicity that affects plants and humans (Uauy et al. 2006; Peleg et al. 2009). Thus, excavating for QTLs or genes with high Zn and Fe efficiencies to improve GZn and GFe accumulation in wheat is a safe and efficient biotechnology method. The use of genetic engineering has uncovered a new method for increasing the accumulation of GFe and GZn in wheat (Connorton andBalk 2019; Kathleen 2019; Henry et al. 2018).

Comparisons with QTL mapping

The genetic basis for and QTL mapping of GZn and GFe accumulation will serve as important references for selecting suitable breeding strategies through molecular marker-assisted breeding to improve GZn and GFe concentrations in wheat. In previous studies, if the genetic loci of GZn and GFe concentrations were located on the same or similar chromosomal regions, the loci had stable genetic effects (Gupta et al. 2020; Cao et al. 2020). In this study, the variation distributions of GZn and GFe concentrations of the RILs were continuous and susceptible to environmental factors, indicating they were quantitative traits controlled by multiple genes (Fig. 1), which was consistent with the findings of Velu et al. (2016). A total of 17 QTLs were detected that controlled GZn and GFe concentrations (Fig. 2). Compared to a previous study, the physical interval of QGZn.haust-1BL and QGFe.haust-1BL was 554.7–635.1 Mb, which was close to the location of QGZn.cimmyt-1B.5 detected by Crespo-Herrera et al. (2017) Therefore, we speculated that these 3 QTLs may be the same. The physical interval of QGZn.haust-4AL and QGFe.haust-4AL was 720.1–731.0 Mb. Crespo-Herrera et al. (2017) detected QGFe.cimmyt-4A and QGZn.cimmyt-4A at the physical positions 5.1 and 84.0 Mb, respectively. Gopalareddy et al. (2017) detected a locus for QGZn.iari-4A at 429.7 Mb, which was located far away from the locus detected in this study; therefore, it may be a new QTL. The physical interval of QGZn.haust-5DL and QGFe.haust-5DL was 432.8–554.8 Mb, which was located far away from QGFe.sau-5D in a previous study (Tong et al. 2020). However, they were similar to the loci of GZn-Xwmc357 and GFe-Xwmc357 detected by GWAS, indicating that they may be the same QTL (Gorafi et al. 2016). QGFe.haust-6BS is a major QTL with a physical interval of 32.7–39.4 Mb, which is located far away from QGFe.cimmyt-6B, QGZn.cimmyt-6B.1, QGZn.cimmyt-6B.1, QGFe.uh-6B, QGZn.uh-6B, QGZn.ua-6B, QGZn.huj-6B, and QGFe.huj-6B in previous studies and thus may be a new QTL. QGZn.haust-7AS.1 is a major QTL with a physical interval of 50.6–51.8 MB, which is close to QGZn.pau-7AS.1 and QGFe.pau-7AS.1, suggesting that they may be the same QTL (Tong et al. 2020).

Candidate gene analysis

There are nearly 200 Fe/Zn-related genes in Arabidopsis and rice, which a previous study used in a BLAST analysis against the wheat database in EnsemblPlants (Tong et al. 2020). Using the QTLs identified in this study, we compared the homologous genes controlling GZn and GFe concentrations in rice and Arabidopsis. TraesCS1B02G359000 is located in the physical interval of QGZn.haust-1BL. TraesCS2B02G530500, TraesCS2B02G543700, and TraesCS2B02G543800 are located in the physical interval of QGZn.haust-2BL. TraesCS2B02G443800 and TraesCS2B02G466500 are located in the physical interval of QGFe.haust-2BL. TraesCS3B02G562500 is located in the physical interval of QGZn.haust-3BL. TraesCS4B02G056600 and TraesCS4B02G081200 are located in the physical interval of QGZn.haust-4BS. TraesCS5A02G383400 and TraesCS5A02G391000 are located in the physical interval of QGZn.haust-5AL. TraesCS6B02G056600 and TraesCS4B02G081200 are located in the physical interval of QGZn.haust-5AL. TraesCS6B02G058700 and TraesCS6B02G391000 are located in the physical interval of QGZn.haust-5AL. By editing these genes, GZn and GFe concentrations in wheat can theoretically be effectively regulated. However, this biotechnology method is rarely used for the improvement of GZn and GFe concentrations in wheat. When OsNAS2 and PvFERRITIN are overexpressed in wheat, the GZn concentrations in wheat is thereby improved, thus laying a foundation for further research on Zn/Fe biofortification in wheat (Beasley et al. 2019; Singh et al. 2017).

Pleiotropic analysis of GZn and GFe concentrations

In this study, we identified QTLs on chromosomes 1B, 4A, and 5D that simultaneously control GZn and GFe concentrations in wheat (Table 5). These loci are pleiotropic QTLs. Moreover, Rathan et al. (2021) showed that nine RILs with the best combination of pleiotropic QTL for Zn and Fe have been identified to be used in future crossing programs and to be screened in elite yield trials before releasing as biofortified varieties. Gorafi et al. (2016) found a pleiotropic locus that controls GZn and GFe concentrations on chromosome 5D. Velu et al. (2016) found a pleiotropic locus on chromosome 2B that controls GZn and GFe concentrations, and demonstrated that a single locus could simultaneously increase GZn and GFe concentrations. Peleg et al. (2009) found pleiotropic QTLs that control GZn and GFe concentrations in tetraploid wheat. Therefore, it can be inferred that the accumulation of GZn and GFe concentrations has a similar genetic basis. Hao et al. (2021) reported that in the past 80 years, the GZn concentration increased but the GFe concentration decreased in Chinese wheat breeding. However, other studies showed that there was a significant positive correlation between GZn and GFe concentrations in wheat (Zhao et al. 2009; Morgounov et al. 2007). It was speculated that this result was due to the fact that Zn and Fe fertilizers were not applied in the experiment, which did not lead to coion antagonism effect. The effects of the pleiotropic loci on chromosome 5DL (QGZn.haust-5DL and QGFe.haust-5DL) in the germplasm panels corroborated these findings. The frequency of germplasm panels carrying favorable allelic variants of CC was lower than GG alleles, indicating that the pleiotropic loci (QGZn.haust-5DL and QGFe.haust-5DL) have considerable application value in breeding. The development of KASP markers can be effectively used for molecular marker-assisted breeding for the enhancement of GZn and GFe in wheat. Some transporters, chelators, and genes simultaneously regulate GZn and GFe concentrations in wheat (Shanmugam et al. 2013; Tong et al. 2020). These results indicated that GZn and GFe concentrations can be improved simultaneously in breeding programs aimed at the biofortification of trace elements. Therefore, it is most important that quantitative trait loci and KASP marker for grain zinc and iron concentrations were developed for utilizing in marker-assisted breeding and biofortification of wheat grain in breeding programs.

Conclusion

In this study, QTLs for GZn and GFe concentrations were identified using 164 RILs derived from Avocet/Chilero. Four stable QTLs, QGZn.haust-4AL, QGFe.haust-1BL, QGFe.haust-4AL, and QGFe.haust-5DL, were located on chromosomes 1BL, 4AL, and 5DL. Three pleiotropic effects loci for GZn and GFe concentrations were located on chromosomes 1BL, 4AL, and 5DL. Two high-throughput Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR markers were developed by closely linking single-nucleotide polymorphisms on chromosomes 4AL and 5DL, which were validated by a germplasm panel, further expanding upon the theoretical foundation for Zn and Fe biofortification and genetic improvement.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Ravi P. Singh, Dr. Xianchun Xia, and Dr. Yuanfeng Hao for their critical review of this manuscript.

Appendix

Fig. 4.

Genetic linkage map of major and pleiotropic effects loci for GZn and GFe concentrations in the wheat RIL population

Author contribution

CPW conceived and supervised the complete study, including data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, and writing—review and editing. PXR performed the experiment and wrote the paper, including data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. DHZ performed the experiment, including data curation, software, validation, writing—review and editing. ZKZ, YZ, and XFY participated in the field trials, trait evaluation, and software analysis. CXL provided resources and extensive revision of the manuscript. All authors read the final version of the manuscript and approved its publication.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD0100904), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (162300410077), and the International Cooperation Project of Henan Province (172102410052).

Data availability

Data of biparent and 164 F6 individuals are not publicly available due to the research on other important traits, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The other data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this manuscript and supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval

We declare that these experiments complied with the ethical standards in China.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

We agree that this manuscript is published in Molecular Breeding.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Pengxun Ren and Dehui Zhao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Pengxun Ren, Email: pengxun_ren@163.com.

Chunping Wang, Email: chunpingw@haust.edu.cn.

References

- An DG. Breeding wheat for enhanced micronutrients. Can J Plant Sci. 2011;91:231–237. doi: 10.4141/CJPS10117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basnet BR, Singh RP, Ibrahim AMH, et al. Characterization of Yr54 and other genes associated with adult plant resistance to yellow rust and leaf rust in common wheat Quaiu 3. Mol Breeding. 2014;33:385–399. doi: 10.1007/s11032-013-9957-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley JT, Bonneau JP, Sánchez-palacios JT, et al. Metabolic engineering of bread wheat improves grain iron concentration and bioavailability. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;08:1514–1526. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S, Xu D, Hanif M, Xia X, He Z. Genetic architecture underpinning yield component traits in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133:1811–1832. doi: 10.1007/s00122-020-03562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Singh D, Pathak J, et al. SNP discovery from next-generation transcriptome sequencing data and their validation using KASP assay in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Mol Breeding. 2017;37:92. doi: 10.1007/s11032-017-0696-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connorton JM, Balk J. Iron biofortification of staple crops: lessons and challenges in plant genetics. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019;60:1447–1456. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcz079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-herrera LA, Velu G, James S, Hao Y, Singh RP. QTL mapping of grain Zn and Fe concentrations in two hexaploid wheat RIL populations with ample transgressive segregation. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1800. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-herrera LA, Velu G, Singh RP. Quantitative trait loci mapping reveals pleiotropic effect for grain iron and zinc concentrations in wheat. Ann Appl Biol. 2016;169:27–35. doi: 10.1111/aab.12276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Genc Y, Verbyla AP, Torun AA, et al. Quantitative trait loci analysis of zinc efficiency and grain zinc concentration in wheat using whole genome average interval mapping. Plant Soil. 2009;314:49–66. doi: 10.1007/s11104-008-9704-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalareddy K, mahendru SA, Swati C. Molecular mapping of the grain iron and zinc concentration, protein content and thousand kernel weight in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) PloS One. 2017;12:e0174972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta PK, Balyan HS, Sharma S, Kumar R. Genetics of yield, abiotic stress tolerance and biofortification in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133:1569–1602. doi: 10.1007/s00122-020-03583-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorafi YSA, Ishii T, Kim JS, et al. Genetic variation and association mapping of grain iron and zinc contents in synthetic hexaploid wheat germplasm. Plant Genet Resour. 2016;1:1–9. doi: 10.1017/s1479262116000265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henry RJ, Furtado A, Rangan P. Wheat seed transcriptome reveals genes controlling key traits for human preference and crop adaptation. ScienceDirect Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2018;45:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao BZ, Ma JL, Chen P, Jiang LN, Wang XJ, Li CX, Wang ZM. Wheat breeding in China over the past 80 years has increased grain zinc but decreased grain iron concentration. Field Crop Res. 2021;271:108253. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JB, Nyquist WE, Cervantes-Matinez CT. Estimating and interpreting heritability for plant breeding: an update. Plant Breed Rev. 2003;22:9–111. doi: 10.1002/9780470650202.ch2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jalal A, Shah S, Filho MCMT, et al. Agro-biofortification of zinc and iron in wheat grains. Gesunde Pflanz. 2020;72:227–236. doi: 10.1007/s10343-020-00505-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kathleen H. Biotechnological approaches for generating zinc-enriched crops to combat malnutrition. Nutrients. 2019;11:253. doi: 10.3390/nu11020253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopittke PM, Punshon T, Paterson D, et al. Synchrotron-based X-ray fluorescence microscopy as a technique for imaging of elements in plants. Plant Physiol. 2018;178:507–523. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutman UB, Yildiz B, Cakmak I. Improved nitrogen status enhances zinc and iron concentrations both in the whole grain and the endosperm fraction of wheat. J Cereal Sci. 2011;53:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2010.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li HH, Zhang LY, Wang JK. Analysis and answers to frequently asked questions in quantitative trait locus mapping. Acta Agron Sin. 2010;36:918–931. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2010.00918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wu B, Singh RP, Velu G. QTL mapping for micronutrients concentration and yield component traits in a hexaploid wheat mapping population. J Cereal Sci. 2019;88:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Ji YY, Li LR, Li ZL, Wu Y. Analysis of Fe, Zn and Se contents in different wheat cultivars (lines) planted in different areas. Chin J Appl Environ Biol. 2010;05:646–649. [Google Scholar]

- Maathuis F. Physiological functions of mineral macronutrients. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L, Li H, Zhang L, Wang J. QTL IciMapping: integrated software for genetic linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus mapping in biparental populations - ScienceDirect. The Crop Journal. 2015;3:269–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2015.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgounov A, Gómez-Becerra HF, Abugalieva A, et al. Iron and zinc grain density in common wheat grown in Central Asia. Euphytica. 2007;155:193–203. doi: 10.1007/s10681-006-9321-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nikwan S, Bahram H, Christopher M. Meta-analysis of QTLome for grain zinc and iron contents in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Euphytica. 2021;217:86. doi: 10.1007/s10681-021-02818-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg Z, Cakmak I, Ozturk L, et al. Quantitative trait loci conferring grain mineral nutrient concentrations in Durum wheat x Wild Emmer wheat RIL population. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;119:353–369. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1044-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce-Molina LJ, Huerta-Espino J, Singh RP, et al. Characterization of leaf rust and stripe rust resistance in spring wheat ‘Chilero’. Plant Dis. 2018;102:421–427. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-11-16-1545-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed A, Liu J, Gao Q, Dreisigacker S, Zhai S. Development and validation of KASP assays for genes underpinning key economic traits in bread wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2016;129:1843–1860. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2743-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed A, Hao Y, Xia X, et al. Crop breeding chips and genotyping platforms: progress, challenges and perspectives. Mol Plant. 2017;10:1047–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan MH, Mcinerney JK, Record IR, Angus JF. Zinc bioavailability in wheat grain in relation to phosphorus fertiliser, crop sequence and mycorrhizal fungi. J Sci Food Agric. 2010;88:1208–1216. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rathan ND, Sehgal D, Thiyagarajan K, Singh R, Singh AM, Govindan V (2021) Identification of genetic loci and candidate genes related to grain zinc and iron concentration using a zinc-enriched wheat 'Zinc-Shakti'. Front Genet 12:652653. 10.3389/fgene.2021.652653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam V, Lo JC, Yeh KC. Control of Zn uptake in Arabidopsis halleri: a balance between Zn and Fe. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:281. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivangi N, Devendra S, Himanshu P, Rajesh KS. Biofortification for high Fe and Zn in various Poaceae crops by using different molecular breeding and biotechnological approaches. Plant Physiol. 2021;26:636–646. doi: 10.1007/s40502-021-00625-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Keller B, Gruissem W, Bhullar NK. Rice NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHASE 2 expression improves dietary iron and zinc levels in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2017;130:283–292. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2808-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava PC, Ansari UI, Pachauri SP, Tyagi AK. Effect of zinc application methods on apparent utilization efficiency of zinc and potassium fertilizers under rice-wheat rotation. J Plant Nutr. 2015;39:348–364. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2015.1016170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, et al. Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995–2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:16–25. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong J, Sun M, Wang Y, et al. Molecular sciences dissection of molecular processes and genetic architecture underlying iron and zinc homeostasis for biofortification: from model plants to common wheat. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:9280. doi: 10.3390/ijms21239280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uauy C, Distelfeld A, Fahima T, Blechl A, Dubcovsky J. A NAC gene regulating senescence improves grain protein, zinc, and iron content in wheat. Science. 2006;314:1298–1301. doi: 10.1126/science.1133649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velu G, Herrera LC, Guzman C, et al. Assessing genetic diversity to breed competitive biofortified wheat with enhanced grain Zn and Fe concentrations. Front Plant Sci. 2019;9:1971. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velu G, Ortiz-monasterio I, Cakmak I, Hao Y, Singh RP. Biofortification strategies to increase grain zinc and iron concentrations in wheat. J Cereal Sci. 2014;59:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2013.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velu G, Tutus Y, Gomez-becerra HF, et al. QTL mapping for grain zinc and iron concentrations and zinc efficiency in a tetraploid and hexaploid wheat mapping populations. Plant Soil. 2016;411:81–99. doi: 10.1007/s11104-016-3025-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay K, Tiwari NR, Parveen C, et al. Mapping of quantitative trait Loci for grain iron and zinc concentration in diploid A genome wheat. J Hered. 2009;100:771. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esp030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JK. Inclusive composite interval mapping of quantitative trait genes. Acta Agron Sin. 2009;35:239–245. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2009.00239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Xu X, Hao Y, et al. QTL mapping for grain zinc and iron concentrations in bread wheat. Front Nutr. 2021;8:680391. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.680391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue YF, Yue SC, Zhang YQ, et al. Grain and shoot zinc accumulation in winter wheat affected by nitrogen management. Plant Soil. 2012;361:153–163. doi: 10.1007/s11104-012-1510-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Xue WT, Yang RZ, et al. QTL mapping analysis of the yield of grain protein, Fe and Zn of single plant using RIL population from Durum wheat × Wild Emmer wheat. J Triticeae Crops. 2013;33:1149–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z, Wang C, Wang Z, et al. Genetic analysis and gene detection of fructan content using DArT molecular markers in spring bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grain. Mol Breeding. 2020;40:23. doi: 10.1007/s11032-020-1102-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Gladyshev VN. Comparative genomics of trace element dependence in biology. JBC. 2011;286:23623–23629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.172833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao FJ, Su YH, Dunham SJ, et al. Variation in mineral micronutrient concentrations in grain of wheat lines of diverse origin. J Cereal Sci. 2009;49:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2008.11.00. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data of biparent and 164 F6 individuals are not publicly available due to the research on other important traits, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The other data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this manuscript and supplementary information files.