Abstract

Background

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer among US women, and institutional racism is a critical cause of health disparities. We investigated impacts of historical redlining on BC treatment receipt and survival in the United States.

Methods

Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) boundaries were used to measure historical redlining. Eligible women in the 2010-2017 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare BC cohort were assigned a HOLC grade. The independent variable was a dichotomized HOLC grade: A and B (nonredlined) and C and D (redlined). Outcomes of receipt of various cancer treatments, all-cause mortality (ACM), and BC-specific mortality (BCSM) were analyzed using logistic or Cox models. Indirect effects by comorbidity were examined.

Results

Among 18 119 women, 65.7% resided in historically redlined areas (HRAs), and 32.6% were deceased at a median follow-up of 58 months. A larger proportion of deceased women resided in HRAs (34.5% vs 30.0%). Of all deceased women, 41.6% died of BC; a larger proportion resided in HRAs (43.4% vs 37.8%). Historical redlining is a statistically significant predictor of poorer survival after BC diagnosis (hazard ratio = 1.09, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.03 to 1.15 for ACM, and hazard ratio = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.13 to 1.41 for BCSM). Indirect effects via comorbidity were identified. Historical redlining was associated with a lower likelihood of receiving surgery (odds ratio = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.66 to 0.83, and a higher likelihood of receiving palliative care odds ratio = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.04 to 1.91).

Conclusion

Historical redlining is associated with differential treatment receipt and poorer survival for ACM and BCSM. Relevant stakeholders should consider historical contexts when designing and implementing equity-focused interventions to reduce BC disparities. Clinicians should advocate for healthier neighborhoods while providing care.

Cancer is the second-leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, and breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer among US women (1-4). In 2021, there were 281 550 cases and 43 600 BC-related deaths, and BC was the second-leading cause of cancer-related death (5). Age and racial disparities exist, and racial disparities have been attributed to wealth inequalities and structural barriers to cancer prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment (2,6-10). Structural and social barriers such as poor health-care access, racial discrimination, and systemic disinvestments in minoritized communities are major causes of cancer disparities (11), contribute to comorbid conditions among cancer survivors, and exacerbate racial and ethnic health disparities (8).

Institutional racism is a root cause of marginalization of individuals from racialized groups and contributes to systemic inequalities in socioeconomic status (SES) (6,8,12,13). Historically racist policies include mortgage-lending discrimination, racially restrictive housing covenants, segregation, and redlining (8,14-16). During the 1930s and the Great Depression, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was created to refinance defaulting home mortgages, prevent foreclosure, and expand home-buying opportunities (16). The HOLC City Survey project (1935-1940) generated color-coded maps to assess neighborhood creditworthiness by mortgage security risk (17). Although the direct influence of HOLC maps on lending practice has been debated (15,18,19), these maps captured the nature of US cities at the time and signaled the government’s support for devaluing areas inhabited primarily by individuals of color. As such, they are important historical records of institutionalized racism, indicating areas affected by government-sanctioned redlining (6-9,13,20). Poor historical redlining grades have been associated with adverse health outcomes (21) including higher BC risk (22), late-stage cancer diagnosis (23), and lower life expectancy (24).

Unfortunately, biased mortgage-lending practices persist today, and contemporary redlining has been associated with poorer survival after BC diagnosis (10,25). However, the influence of historical redlining on BC survival across the United States remains only partially understood (23). In this paper, we investigate the impact of historical redlining on BC survival and treatment (receipt of surgery, radiation, systemic treatment, palliative care) among older women diagnosed with BC in Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registries of California, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, and New York (2010-2017). We hypothesized that women residing in historically redlined areas (HRAs) will be less likely to receive treatment and experience poorer survival for all-cause mortality (ACM) and BC-specific mortality (BCSM), with a portion of the relationship explained by comorbidities at diagnosis.

Methods

Datasets

First, women with newly diagnosed invasive BC were identified from the SEER-Medicare–linked database (2010-2017). Second, HOLC maps from the Mapping Inequality Project were merged (26). Third, we identified population-weighted centers (a centroid that has been moved so that it represents the population center rather than the geometric center of an area or a polygon) for 2010 US census tracts and determined historical HOLC grade for these points using a point-in-polygon approach, given that HOLC and tract boundaries do not spatially align. Finally, a historical HOLC grade was assigned to each woman based on her residential census tract at diagnosis, excluding women without a HOLC grade match.

Cohort identification

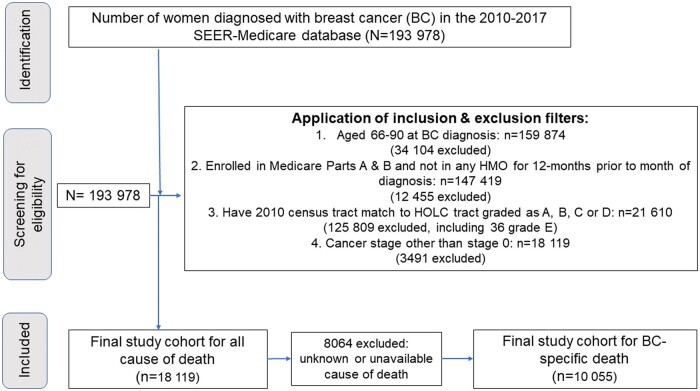

Women were included if they were aged 66-90 years, diagnosed with their first BC during 2010-2017, and alive at diagnosis. To calculate comorbidity, the cohort was restricted to women enrolled in Medicare parts A and B and not in a health maintenance organization for 12 months prior to diagnosis. Only women residing in a historical HOLC area graded as A, B, C, or D at BC diagnosis were included (n = 21 610). Women with stage 0 disease were excluded (n = 3491). The final sample size was 18 119 for ACM and 10 055 for BCSM after excluding women with unknown or unavailable cause of death (CoD) (n = 8064). The flowchart of the cohort identification process is illustrated in Figure 1. Five treatment-specific cohorts were created to evaluate the receipt of 5 different treatment outcomes, per the National Quality Forum measures, except palliative care outcome (Supplementary Table 1, available online) (27).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study cohort identification. HMO = health maintenance organization; HOLC = Home Owners’ Loan Corporation; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Variables

Outcome variables: receipt of treatment, all-cause, and BC-specific mortality

Outcome variables are receipt of 5 different treatments (see Table 2), ACM, and BCSM. Survival time was calculated using date of death from the Medicare enrollment file for deceased patients. BCSM was identified using CoD information from SEER.

Table 2.

Characteristics of treatment-specific cohorts within the 2010-2017 SEER-Medicare BC cohort by historical redlining status

| Characteristics | Total | Historically redlineda | Historically nonredlinedb |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Cohort 1: Localized and regional SEER summary stage | 15 781 | 10 242 (64.9) | 5539 (35.1) |

| Had breast surgery within 12 mo of diagnosis | |||

| Yes | 14 266 (90.4) | 9159 (89.4%) | 5107 (92.2%) |

| No | 1515 (9.6) | 1083 (10.6%) | 432 (7.8%) |

| Cohort 2: Localized and regional SEER summary stage and underwent breast-conserving surgery (BCS) | 10 015 | 6313 (63.0) | 3702 (37.0) |

| Had radiation therapy within 12 mo of BCS | |||

| Yes | 7448 (74.4) | 4676 (74.1) | 2772 (74.9) |

| No | 2567 (25.6) | 1637 (25.9) | 930 (25.1) |

| Cohort 3: Localized and regional SEER summary stage and hormone receptor–negative tumor | 1901 | 1310 (68.9) | 591 (31.1) |

| Received chemotherapy within 4 mo of diagnosis | |||

| Yes | 989 (52.0) | 667 (50.9) | 322 (54.5) |

| No | 912 (48.0) | 643 (49.1) | 269 (45.5) |

| Cohort 4: Localized and regional SEER summary stage and HER2-positive tumor | 1606 | 1069 (66.6) | 535 (33.4) |

| Received HER2-targeted therapyc | |||

| Yes | 799 (49.8) | 529 (49.5) | 270 (50.1) |

| No | 805 (50.2) | 540 (50.5) | 265 (49.5) |

| Cohort 5: Distant disease SEER summary stage | 1205 | 855 (70.9) | 350 (29.1) |

| Received palliative care within 12 mo of diagnosis | |||

| Yes | 291 (24.2) | 220 (25.7) | 71 (20.3) |

| No | 914 (75.9) | 635 (74.3) | 279 (79.7) |

HOLC grades C and D. BC = breast cancer; CI = confidence interval; HOLC = Home Owners’ Loan Corporation; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

HOLC grades A and B.

HER2-targeted treatment received within 4 months of diagnosis or within 12 months of diagnosis if anthracycline-based chemotherapy initiated within first 4 months of diagnosis.

Independent variable: HOLC grade (historical redlining)

The primary predictor was HOLC grade. HOLC categorized cities’ neighborhoods into 4 grades (A, B, C, and D) based on desirability for investment to represent mortgage-lending risk. Grade A was green/best; B was blue/still desirable; C was yellow/definitely declining; and D was red/hazardous. HOLC grade was dichotomized into “historically redlined” (grades C and D) and “nonhistorically redlined” (grades A and B). Sensitivity analyses were done with a 4-level redlining indicator.

Covariates and mediators

Covariates including age, tumor stage at diagnosis, and combined tumor receptor status (estrogen and progesterone receptor [hormone receptor]/HER2 status) were obtained from SEER and are all known to impact BC survival (10). Age at diagnosis was classified into 4 categories (66-70, 71-75, 76-80, and 81-90 years). Combined hormone receptor and HER2 tumor receptor status included 5 categories (hormone receptor positive and HER2 positive; hormone receptor positive and HER2 negative, hormone receptor negative and HER2 positive; hormone receptor negative and HER2 negative; and unknown). Tumor stage classification followed the SEER summary stage (localized, regional, distant, and unknown or unstaged), excluding stage 0 cancers. For sensitivity analyses, race and ethnicity were included as a covariate, represented as a 4-category variable using a combination of SEER race and ethnicity variables. Individuals identified as Hispanic were grouped into 1 category, and non-Hispanics individuals were categorized by racial category. Non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White women were included as separate groups, whereas Asians, Pacific Islanders, Native Americans, and others were aggregated into 1 non-Hispanic Other group. Comorbidity was calculated using inpatient, outpatient, and carrier Medicare claims data during 12 months before incident BC using the Klabunde algorithm (grouped into: none, 1, and ≥2) (28).

Analytical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata SE 17.0; the statistical significance level was set at alpha = 0.05. Descriptive statistics and χ2 tests were used to summarize sample/cohort characteristics by HOLC grades. Kaplan-Meier and Aalen-Johansen methods were used to estimate survival probability and probability of BC-specific death over time. Log-rank tests were used to compare 1- and 5-year survival between different HOLC grades. Logistic and Cox proportional hazards regression models were respectively used to model treatment receipt likelihood and time to death for ACM and BCSM. Loss-to-follow-up right censoring occurred on December 31, 2019, for ACM and December 31, 2018, for BCSM, based on vital status from Medicare and CoD from SEER.

The proportional hazards assumption was tested. Variables that violated the assumption were stratified (age, stage, and tumor type for ACM; stage and tumor type for BCSM). We used sequential adjustment to estimate the contribution of comorbidities to the disparity by estimating change-in-regression coefficient, with standard error adjusted for HOLC city clusters.

Results

Table 1 summarizes sample demographics and tumor characteristics for ACM by redlining status (n = 18 119; 65.7% in HRAs). Women in HRAs were more likely to be non-Hispanic Black (20.6% vs 11.7%) and have multiple comorbidities (33.0% vs 24.0%), triple-negative BC (9.4% vs 8.0%), and distant disease (7.5% vs 5.9%). At a median follow-up of 58 months, women who resided in HRAs were more likely to die (34.5% vs 30.0%) than women in non-HRAs. Among deceased patients (n = 2923), women in HRAs were more likely to die from BC than women in non-HRAs (43.4% vs 37.8%). Similar findings were observed in the BCSM cohort (Supplementary Table 2, available online). With respect to treatment outcomes (Table 2), among women with localized and regional disease, those residing in HRAs were less likely to receive breast surgery (89.4% vs. 92.2%) but there was no difference in receipt of postlumpectomy radiation treatment, chemotherapy for hormone receptor–negative tumors, or HER2-targeted treatment for HER2-positive tumors. After adjusting for patient age and comorbidity, these findings persisted (odds ratio [OR] = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.66 to 0.83; Table 3]. Among women with distant disease, those residing in HRAs were more likely to receive palliative care (25.7% vs 20.3%; OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.04 to 1.91).

Table 1.

Cohort demographic characteristics of the 2010-2017 SEER-Medicare BC cohort by historical redlining status (n = 18 119)

| Characteristics | Total | Historically redlineda | Historically nonredlinedb | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 18 119 | n = 11 912 (65.7%) | n = 6207 (34.3%) | ||

| Kaplan-Meier Survival probability for all-cause mortality | <.001 | |||

| 1-year survival probability (95% CI) | 0.92 (0.92 to 0.93) | 0.94 (0.94 to 0.95) | ||

| 5-year survival probability (95% CI) | 0.70 (0.70 to 0.71) | 0.75 (0.74 to 0.76) | ||

| Age at diagnosis, No. (%) | .761 | |||

| 66-70 y | 4986 (27.5) | 3304 (27.7) | 1682 (27.1) | |

| 71-75 y | 4587 (25.3) | 3000 (25.2) | 1587 (25.6) | |

| 76-80 y | 3762 (20.8) | 2480 (20.8) | 1282 (20.7) | |

| 81-90 y | 4784 (26.4) | 3128 (26.3) | 1656 (26.7) | |

| Race and ethnicity, No. (%) | <.001 | |||

| Hispanic | 1793 (9.9) | 1406 (11.8) | 387 (6.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3179 (17.6) | 2452 (20.6) | 727 (11.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 879 (4.9) | 671 (5.6) | 208 (3.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 12 268 (67.7) | 7383 (62.0) | 4885 (78.7) | |

| Comorbidity, No. (%) | <.001 | |||

| None | 7943 (43.8) | 4844 (40.7) | 3099 (49.9) | |

| 1 | 4748 (26.2) | 3132 (26.3) | 1616 (26.0) | |

| ≥2 | 5428 (30.0) | 3936 (33.0) | 1492 (24.0) | |

| Tumor stage at diagnosis, SEER summary stage, No. (%) | <.001 | |||

| Localized | 12 183 (67.2) | 7823 (65.7) | 4360 (70.2) | |

| Regional | 4179 (23.1) | 2844 (23.9) | 1335 (21.5) | |

| Distant | 1254 (6.9) | 890 (7.5) | 364 (5.9) | |

| Unknown or unstaged | 503 (2.8) | 355 (3.0) | 148 (2.4) | |

| Hormone receptor and tumor receptor status, No. (%) | <.001 | |||

| Hormone receptor positive/HER2- | 12 804 (70.7) | 8269 (69.4) | 4535 (73.1) | |

| Hormone receptor negative/HER2 negative, triple-negative | 1611 (8.9) | 1117 (9.4) | 494 (8.0) | |

| Hormone receptor positive/HER2+ | 1321 (7.3) | 863 (7.2) | 458 (7.4) | |

| Hormone receptor negative/HER2+ | 537 (3.0) | 377 (3.2) | 160 (2.6) | |

| Unknown | 1846 (10.2) | 1286 (10.8) | 560 (9.2) | |

| Vital status, No. (%) | <.001 | |||

| Alive | 12 208 (67.4) | 7800 (65.5) | 4408 (71.0) | |

| Deceased | 5911 (32.6) | 4112 (34.5) | 1799 (30.0) | |

| CoD, only for the 2923 with available CoD information; censoring date is December 31, 2018, No. (%) | .015 | |||

| CoD other than BC | 1652 (56.5) | 1074 (54.7) | 578 (60.3) | |

| Died of BC | 1216 (41.6) | 853 (43.4) | 363 (37.8) | |

| Unknown | 55 (1.9) | 37 (1.9) | 18 (1.9) |

HOLC grades C and D. Censoring date is December 31, 2019. BC = breast cancer; CI = confidence interval; CoD = cause of death; HOLC = Home Owners’ Loan Corporation; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

HOLC grades A and B.

Table 3.

Logistic regression models exploring unadjusted and adjusted effect of historical redlining (HOLC grades) on treatment received using 5 distinct cohorts within the 2010-2017 SEER-Medicare BC cohort

| Variables | Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 | Cohort 4 | Cohort 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast surgery within 12 mo of diagnosis | Radiation therapy within 12 mo of breast-conserving surgery | Chemotherapy within 4 mo of diagnosis | HER2-targeted therapya | Palliative care within 12 mo of diagnosis | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Unadjusted models | |||||

| HOLC grades | |||||

| Non-HRA | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| HRA | 0.72 (0.64 to 0.80)b | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.05) | 0.87 (0.71 to 1.05) | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.18) | 1.36 (1.01 to 1.84)b |

| Adjusted models | |||||

| HOLC grades | |||||

| Non-HRA | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| HRA | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.83)b | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.05) | 0.86 (0.70 to 1.06) | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.19) | 1.41 (1.04 to 1.91)b |

| Age, y | |||||

| 66-70 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 71-75 | 0.82 (0.69 to 0.99)b | 0.58 (0.49 to 0.67)b | 0.61 (0.47 to 0.79)b | 0.95 (0.72 to 1.25) | 1.13 (0.75 to 1.69) |

| 76-80 | 0.66 (0.55 to 0.79)b | 0.32 (0.27 to 0.37)b | 0.35 (0.27 to 0.46)b | 0.60 (0.45 to 0.80)b | 1.23 (0.82 to 1.86) |

| 81-90 | 0.27 (0.23 to 0.32)b | 0.12 (0.11 to 0.14)b | 0.13 (0.10 to 0.18)b | 0.29 (0.22 to 0.38)b | 1.46 (1.00 to 2.12)b |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| None | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 1 | 0.99 (0.85 to 1.14) | 0.95 (0.84 to 1.06) | 0.92 (0.72 to 1.17) | 0.67 (0.52 to 0.87)b | 0.68 (0.48 to 0.97)b |

| ≥2 | 0.56 (0.49 to 0.64)b | 0.75 (0.67 to 0.84)b | 0.66 (0.52 to 0.82)b | 0.48 (0.38 to 0.62)b | 0.78 (0.57 to 1.07) |

HER2-targeted treatment received within 4 months of diagnosis or within 12 months of diagnosis if anthracycline-based chemotherapy initiated within first 4 months of diagnosis. BC = breast cancer; CI = confidence interval; HOLC = Home Owners’ Loan Corporation; HRA = historically redlined (A and B); non-HRA = nonhistorically redlined (A and B); OR = odds ratio; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Denotes statistical significance.

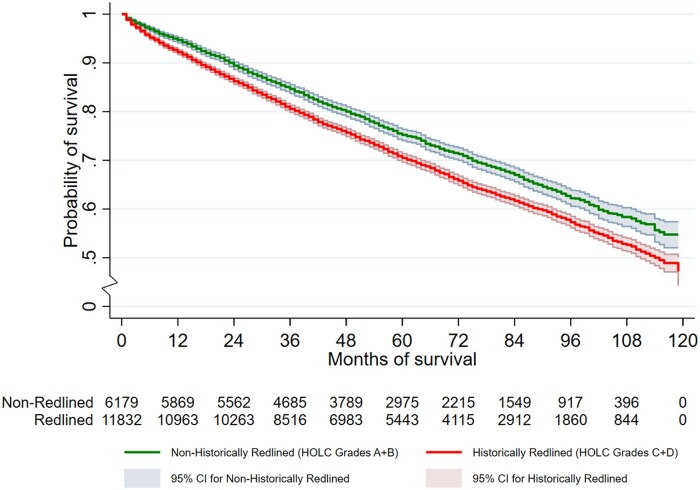

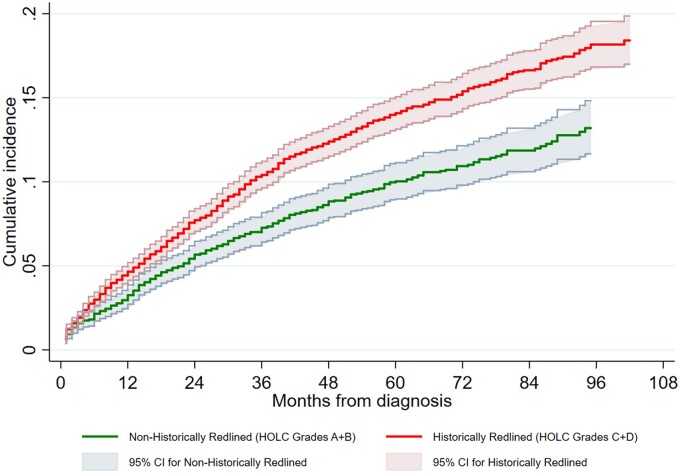

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the survival function for ACM and Aalen-Johansen estimates of cumulative incidence for BCSM are respectively shown in Figures 2 and 3, with a clear gradient effect. Women in HRAs had a poorer survival than those in non-HRAs. One-year Kaplan-Meier survival probability and 95% confidence interval are worse for women in HRAs (0.92, 95% CI = 0.92 to 0.93) than women in non-HRAs (0.94, 95% CI = 0.94 to 0.95). The same is true for 5-year Kaplan-Meier survival probability (0.70, 95% CI = 0.70 to 0.71 for women in HRAs vs 0.75, 95% CI = 0.74 to 0.76 for women in non-HRAs), and similar findings were observed for BCSM (Supplementary Table 2, available online).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of the survival function for all-cause mortality: SEER-Medicare Breast Cancer Cohort (2010-2017). CI = confidence interval; HOLC = Home Owners’ Loan Corporation; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Figure 3.

Aalen-Johansen estimate of cumulative incidence for breast cancer–specific mortality: SEER-Medicare BC Cohort (2010-2017). CI = confidence interval; HOLC = Home Owners’ Loan Corporation; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Table 4 summarizes model results relating historical redlining and ACM. In model 1 (unadjusted), hazard ratios (HR) were 1.22 (95% CI = 1.16 to 1.29) for women in HRAs compared with women in non-HRAs. In model 2 (without comorbidity, total effect of redlining on ACM) and model 3 (with comorbidity as a mediator, direct effect of redlining on ACM), hazard ratios are 1.16 (95% CI = 1.09 to 1.23) and 1.09 (95% CI = 1.03 to 1.15), respectively, for those residing in HRAs. The decrease in magnitude of the hazard ratios indicates that comorbidity explains part of the relationship between redlining and ACM.

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazards models exploring unadjusted and adjusted effects of historical redlining (HOLC grades) and time to death from any cause in the 2010-2017 SEER-Medicare BC Cohorta

| Variables | Model 1: unadjusted (n = 18 011) |

Model 2b: model 1 stratified without comorbidity (n = 18 011) |

Model 3b: model 2 adjusted with comorbidity (n = 18 011) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| HOLC grades | ||||||

| Nonhistorically redlined (A and B) | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Historically redlined (C and D) | 1.22 (1.16 to 1.29) | <.001 | 1.16 (1.09 to 1.23) | <.001 | 1.09 (1.03 to 1.15) | .002 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| None | Referent | Referent | ||||

| 1 | 1.24 (1.15 to 1.33) | <.001 | ||||

| ≥2 | 2.06 (1.87 to 2.26) | <.001 | ||||

A total of 108 women died during the month of diagnosis, and therefore, their survival time is 0 and the Cox model automatically drops them. Censoring date is December 31, 2019. BC = breast cancer; CI = confidence interval; HOLC = Home Owners’ Loan Corporation; HR = hazard ratio; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Stratified on age, hormone receptor and HER2 status, and tumor stage.

Table 5 summarizes results from cause-specific proportional hazards models relating historical redlining and BCSM. In model 1 (unadjusted), BC cause-specific hazard ratios (CSHRs) are 1.45 (95% CI = 1.25 to 1.68) for women in HRAs. In model 2 (age as a covariate) and model 3 (model 2 with comorbidity as a mediator), BC CSHRs are 1.29 (95% CI = 1.15 to 1.45) and 1.26 (95% CI = 1.13 to 1.41) for women in HRAs, respectively. Redlining effects on BCSM are partially mediated by comorbidity and persist after controlling for age. Sensitivity analyses with race and ethnicity as a covariate have similar results for ACM (Supplementary Table 3, available online) and for BCSM (Supplementary Table 4, available online).

Table 5.

Cause-specific proportional hazards models exploring unadjusted and adjusted effects of historical redlining (HOLC grades) on time to BC-specific death in the 2010-2017 SEER-Medicare BC cohort a

| Variables | Model 1: unadjusted (n = 9982) |

Model 2b: model 1 stratified and adjusted without comorbidity (n = 9982) |

Model 3b: model 2 with comorbidity (n = 9982) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSHR (95% CI) | P | CSHR (95% CI) | P | CSHR (95% CI) | P | |

| HOLC grades | ||||||

| Nonhistorically redlined, A and B | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||

| Historically redlined, C and D | 1.45 (1.25 to 1.68) | <.001 | 1.29 (1.15 to 1.45) | <.001 | 1.26 (1.13 to 1.41) | <.001 |

| Age | ||||||

| 66-70 y | — | Referent | Referent | |||

| 71-75 y | — | 1.34 (1.16 to 1.55) | <.001 | 1.32 (1.13 to 1.53) | <.001 | |

| 76-80 y | — | 1.43 (1.20 to 1.70) | <.001 | 1.40 (1.18 to 1.65) | <.001 | |

| 81-90 y | — | 2.48 (2.12 to 2.90) | <.001 | 2.36 (2.03 to 2.74) | <.001 | |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| None | — | — | Referent | |||

| 1 | — | — | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.19) | .714 | ||

| ≥2 | — | — | 1.38 (1.28 to 1.48) | <.001 | ||

A total of 73 women died during the month of diagnosis, and therefore, their survival time is 0 and the Cox model automatically drops them. Censoring date is December 31, 2018. BC = breast cancer; CI = confidence interval; CSHR = cause-specific hazard ratio; HOLC = Home Owners’ Loan Corporation; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Stratified on hormone receptor and HER2 status and tumor stage.

Simultaneous bootstrap with 1000 resamples applied to models 2 and 3 allowed us to evaluate the mediating effect of comorbidity. For ACM, the total effect of historical redlining (beta = 0.147, HR = 1.16; P = .002) is decomposed into direct (beta = 0.087; P < .001) and approximate or indirect (beta = 0.06; P < .001) effects. On the regression coefficient scale (log hazard ratio scale), the proportion of the total effect mediated by comorbidity was 40.1%. For BCSM, the total effect of historical redlining (beta = 0.254, HR= 1.29; P < .001) is decomposed into direct (beta = 0.234; P < .001) and approximate or indirect (beta = 0.020, P = .016) effects. On the regression coefficient scale, the proportion of the total effect mediated by comorbidity was 7.9%.

Sensitivity analyses with a 4-level redlining indicator reaffirmed the above results for BCSM (Supplementary Table 5, available online), with slightly lower hazard ratio when race and ethnicity are included (Supplementary Table 6, available online). Women in HOLC grades C and D had higher BC CSHR compared with women in grade A. BC CSHRs for C and D are 1.42 (95% CI = 1.07 to 1.88) and 1.35 (95% CI = 1.03 to 1.76), respectively. Women in grade B do not have a statistically significant difference in BC CSHR than women in A. Significance was attenuated with the addition of comorbidity as a mediator for ACM (Supplementary Table 7, available online).

Discussion

This study sought to understand the relationship between historical redlining and cancer treatments receipt, ACM, and BCSM among older women diagnosed with BC (2010-2017) in the United States and tested the mediating effect of comorbidity on survival. This is the first study to examine the full scope of HOLC data available in concert with a population-based sample of women with BC. We found that women residing in HRAs had lower likelihood of receiving surgery, higher likelihood of receiving palliative care, and poorer survival than those in non-HRAs. Lower receipt of surgery might be because of decreased access to initial evaluation, including the initial referral process and limited resources such as transportation, inability to take time off of work, childcare issues, or lack of support systems. However, once women entered the health system, there was no difference in receipt of adjuvant treatments (radiation and systemic treatment) by HRA status. The contrasting finding of increased receipt of palliative care among women in HRAs was unexpected and might be because of differences in end-of-life care needs, patient preferences and beliefs, and provider preferences (29,30). Women residing in HRAs may present with a higher disease burden at diagnosis and may require earlier referral for palliative care with a higher level of supportive care and services than those in non-HRAs (31).

Residing in HRAs is a statistically significant predictor of higher mortality, with women living in HRAs having a 16% higher hazard ratio for ACM and 29% higher hazard ratio for BCSM as compared with women in non-HRAs. Analyses showed a mediating effect of comorbidity, with a greater proportion of the effect of redlining explained by comorbidity for ACM (40.1%) as compared with BCSM (7.9%). This is unsurprising, given that highly prevalent comorbidities (ie, cardiovascular diseases) are also primary causes of death for women diagnosed with BC. Future work should examine incidence and mortality from common BC comorbidities, such as cardiovascular diseases, as outcomes in relation to residence in HRAs.

Our findings highlight the impact of historically racist policies and practices on contemporary cancer outcomes. It is likely that other related practices, including in the housing sector, may also have a lasting influence on health outcomes. For instance, the 1938 Federal Housing Administration (FHA) Underwriting Manual was biased in determining the mortgage risk rating process. In articles 932, 933, 934, and 935 of the 1938 FHA underwriting manual, deeds restrictions, zoning, restrictive covenants, and natural physical protection were respectively highlighted as a means to protect “White” neighborhoods from adverse influences to “prevent infiltration of lower class occupancy and inharmonious racial groups.” (18,32,33) The FHA manual indicated that valuators must give a “reject rating” when little or no protection from adverse influences was provided (32). The reality of unequal access to housing opportunities in the United States has contributed to poor SES for individuals targeted for marginalization and contributes to today’s poor health outcomes, including BC survival (8).

Our results are similar to previous studies that have examined historical redlining in concert with a range of outcomes. Studies have found associations between redlining and health determinants including urban greenspaces (20,34), air pollution (20), and current mortgage-lending discrimination (7), among others. Namin et al. (20) found that better neighborhood historical HOLC grades had higher percentage of tree canopy cover, and worse neighborhood HOLC grades had higher air pollution hazards exposure. Lynch et al. (7) found that greater historic redlining score was associated with low mortgage-lending occurrence and higher cost loans in Milwaukee, and Namin et al. (15) found a direct association between HOLC grades and contemporary levels of mortgage-lending bias across the United States. Further, historical redlining has been associated with other poorer cancer-related outcomes, including an elevated risk for late stage at diagnosis for cervical, breast, lung, and colorectal cancer in Massachusetts (23). In addition to historical redlining, Beyer et al. (10) found that contemporary redlining is associated with poorer BC survival among older women across the United States. Similarly, Collin et al. (25) found that living in redlined areas was associated with a 1.60-fold increase in BC mortality in metro-Atlanta.

Our findings, in concert with extant literature, reveal the long-term adverse impact of institutional racism on present-day health outcomes in the United States. We found that a poor historical redlining grade is associated with a lower likelihood of undergoing BC surgery and worse survival for ACM and BCSM. The future of cancer control and care should consider historical context as an important upstream factor that affects survival outcomes. It should be included at the forefront of policy discussions, embedded in research to study disparities and included in crafting community-based and/or clinical interventions to improve cancer-related outcomes. Thus, utilizing a health-in-all-policies approach to improve individual and community health is warranted (35). Clinicians should advocate for healthier neighborhoods as a component of comprehensive patient care and be more mindful of the powerful influence of a patient’s socioeconomic background or other constraints on beliefs, behavior, exposures, access, and ultimately outcomes (36). Clinicians can consider these factors when prescribing treatment regimens, recommending behavioral changes, requiring follow-up, or expecting particular results based on the care they provide. Further, clinicians can adjust course and adapt practice to achieve desired patient outcomes. Examples might include reconsidering policies for cancellations or late arrivals; considering resource constraints when prescribing medications and treatments; being mindful of implicit bias or judgement in patterns of offering particular therapies or clinical trials; adapting patient education to different literacy levels, languages, or educational backgrounds; or anticipating differential impacts of therapies among patients with different histories of chronic stress and being prepared to offer an altered regimen to achieve desired outcomes.

This study has limitations. First, HOLC areas represent the spatial extent of cities in the 1930s, and thus, individuals living in modern-day suburban and rural areas were necessarily excluded. This limits the generalizability of findings with respect to women living outside HOLC-assessed areas and leaves unexplored the impact of historical racism in these areas. Second, this study uses a sample of older women with Medicare insurance, and redlining impact on younger women and women with other insurance types, or the uninsured, could not be assessed. Third, HOLC neighborhoods do not spatially align with contemporary census tracts, and a point-in-polygon approach was taken to assign HOLC grades to current tracts. Because this approach is likely to have resulted in some exposure measurement error, it is likely that true associations between HOLC grade and BC survival may be stronger. Another limitation of Cox models is the noncollapsibility effect. Covariates change baseline hazards and consequently affect regression coefficients in the model (37).

Regardless of these limitations, this study lays strong foundations on the use of HOLC-designated areas in future work, as scientists examine the impact of institutional racism on health outcomes. Future work should investigate the relative contribution of other mediators (ie, SES) on the relationship between redlining and BC survival. Finally, institutional racism differentially impacts different groups; there is a need for outcomes assessment among populations with a range of racial and ethnic identities.

Residing in a HRA is associated with worse survival for ACM and BCSM, and the relationship is partially explained by comorbidity. Patients in HRAs are additionally affected by differences in treatments received. Public health and medical and government agency stakeholders should consider historical contexts when designing and implementing equity-focused interventions. Evaluation of such interventions targeted at mitigating and reducing BC disparities is critical in improving health equity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement # U58DP003862-01 awarded to the California Department of Public Health. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California Department of Public Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS) Inc; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jean C Bikomeye, Division of Epidemiology and Social Sciences, Institute for Health and Equity, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Yuhong Zhou, Division of Epidemiology and Social Sciences, Institute for Health and Equity, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Emily L McGinley, Center for Advancing Population Science, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Bethany Canales, Division of Epidemiology and Social Sciences, Institute for Health and Equity, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Tina W F Yen, Center for Advancing Population Science, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA; Division of Surgical Oncology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Sergey Tarima, Division of Biostatistics, Institute for Health and Equity, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Sara Beltrán Ponce, Division of Radiation Oncology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Kirsten M M Beyer, Division of Epidemiology and Social Sciences, Institute for Health and Equity, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Data availability

The data underlying this article were provided by SEER-Medicare with permission under a data use agreement. Per the data use agreement, data will not be shared. However, SEER-Medicare data are available to investigators for research purposes and may be requested from SEER-Medicare at: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seermedicare/obtain/. The census tracts boundaries are publicly available on the US Census website at https://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2010&layergroup=Census+Tracts; and HOLC boundaries are available on the Mapping Inequality Website at the University of Richmond Digital Scholarship Lab at: https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=5/39.1/-94.58&text=downloads).

Author contributions

Jean C. Bikomeye, MPH (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Validation; Visualization; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Yuhong Zhou, PhD, MS, ME (Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Software; Validation; Visualization; Writing—review & editing), Emily L. McGinley, MS, MPH (Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Software; Validation; Writing—review & editing), Bethany Canales, MPH (Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Writing—review & editing), Tina W.F. Yen, MD, MS, FACS (Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Writing—review & editing), Sergey Tarima, PhD (Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Validation; Writing—review & editing), Sara Beltrán Ponce, MD (Methodology; Resources; Validation; Writing—review & editing), and Kirsten M. M. Beyer, PhD, MPH, MS (Conceptualization; Data curation; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing)

Funding

The work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant: R01CA214805 (PI: KMMB), the American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific focused research network (SFRN) on disparities in Cardio-oncology grant (PI: KMMB; award number: 863108), the AHA Research Supplement to Promote Diversity in Science grant (PI: JCB; award number: 960133), and the Medical College of Wisconsin Cancer Center (KMMB).

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Bikomeye JC, Beyer AM, Kwarteng JL, Beyer KMM.. Greenspace, inflammation, cardiovascular health, and cancer: a review and conceptual framework for greenspace in cardio-oncology research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2426. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A.. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bikomeye JC, Terwoord JM, Santos JH, Beyer AM.. Emerging mitochondrial signaling mechanisms in cardio-oncology: beyond oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022;323(4):H702-H720. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00231.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bikomeye JC, Balza JS, Kwarteng JL, Beyer AM, Beyer KMM.. The impact of greenspace or nature-based interventions on cardiovascular health or cancer-related outcomes: a systematic review of experimental studies. PLoS One. 2022;17(11):e0276517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Cancer Society. Cancer-Facts-and-Figures-2021. 2021. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2021/cancer-facts-and-figures-2021.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2021.

- 6. Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA.. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):105-125. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lynch EE, Malcoe LH, Laurent SE, Richardson J, Mitchell BC, Meier HCS.. The legacy of structural racism: associations between historic redlining, current mortgage lending, and health. SSM Popul Health. 2021;14:100793. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bikomeye JC, Namin S, Anyanwu C, et al. Resilience and equity in a time of crises: investing in public urban greenspace is now more essential than ever in the US and beyond. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8420. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bikomeye JC, Rublee CS, Beyer KMM.. Positive externalities of climate change mitigation and adaptation for human health: a review and conceptual framework for public health research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2481. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beyer KMM, Zhou Y, Laud PW, et al. Mortgage lending bias and breast cancer survival among older women in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(25):2749-2757. doi: 10.1200/jco.21.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gerend MA, Pai M.. Social determinants of Black-White disparities in breast cancer mortality: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(11):2913-2923. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mateo CM, Williams DR.. Racism: a fundamental driver of racial disparities in health-care quality. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):20- 22. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Williams DR, Collins C.. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404-416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsai W-L, Yngve L, Zhou Y, et al. Street-level neighborhood greenery linked to active transportation: a case study in Milwaukee and Green Bay, WI, USA. Landsc Urban Plan. 2019;191:103619. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Namin S, Zhou Y, Xu W, et al. Persistence of mortgage lending bias in the United States: 80 years after the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation security maps. J Race, Ethn City. 2022;3(1):1-25. doi: 10.1080/26884674.2021.2019568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The Living New Deal. Home Owners’ Loan Act (1933). 2016. https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/home-owners-loan-act-1933/. Accessed March 08, 2022.

- 17. Michney TM. How the city survey’s redlining maps were made: a closer look at HOLC’s mortgagee rehabilitation division. J Plan Hist. 2021;21(4):15385132211013360. doi: 10.1177/15385132211013361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fishback P, Rose J, Snowden KA, Storrs T.. New evidence on redlining by federal housing programs in the 1930s. J Urban Econ. 2022;103462. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2022.103462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hillier AE. Redlining and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. J Urban Hist. 2003;29(4):394-420. doi: 10.1177/0096144203029004002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Namin S, Xu W, Zhou Y, Beyer K.. The legacy of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and the political ecology of urban trees and air pollution in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2020;246:112758. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee EK, Donley G, Ciesielski TH, et al. Health outcomes in redlined versus non-redlined neighborhoods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2022;294:114696. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wright E, Waterman PD, Testa C, Chen JT, Krieger N.. Breast cancer incidence, hormone receptor status, historical redlining, and current neighborhood characteristics in Massachusetts, 2005–2015. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2022;6(2):pkac016. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkac016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krieger N, Wright E, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Huntley ER, Arcaya M.. Cancer stage at diagnosis, historical redlining, and current neighborhood characteristics: breast, cervical, lung, and colorectal cancers, Massachusetts, 2001–2015. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189(10):1065-1075. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang SJ, Sehgal NJ.. Association of historic redlining and present-day health in Baltimore. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0261028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Collin LJ, Gaglioti AH, Beyer KM, et al. Neighborhood-level redlining and lending bias are associated with breast cancer mortality in a large and diverse metropolitan area. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(1):53-60. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. University of Richmond Digital Scholarship Lab. Mapping inequality. 2021. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=12/43.03/-83.69&city=flint-mi&area=D18&adimage=4/67/-123. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 27. National Quality Forum. Cancer - measures. https://www.qualityforum.org/ProjectMeasures.aspx?projectID=86163. Accessed December 30, 2022.

- 28. Klabunde CN, Legler JM, Warren JL, Baldwin L-M, Schrag D.. A refined comorbidity measurement algorithm for claims-based studies of breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancer patients. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(8):584-590. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. LoPresti MA, Dement F, Gold HT.. End-of-life care for people with cancer from ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(3):291-305. doi: 10.1177/1049909114565658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brown CE, Engelberg RA, Sharma R, et al. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and healthcare intensity at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(9):1308-1316. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sharma RK, Cameron KA, Chmiel JS, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in inpatient palliative care consultation for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Col. 2015;33(32):3802-3808. doi: 10.1200/JClinOncol.2015.61.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Federal Housing Administration. National Housing Act of the Underwriting and Valuation Procedure under Title II: Underwriting Manual. 1938. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Federal-Housing-Administration-Underwriting-Manual.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2022.

- 33. Kimble J. Insuring inequality: the role of the Federal Housing Administration in the urban ghettoization of African Americans. Law Soc Inq. 2008;32(2):399-434. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nardone A, Rudolph KE, Morello-Frosch R, et al. Redlines and greenspace: the relationship between historical redlining and 2010 greenspace across the United States. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129(1):17006. doi: 10.1289/EHP7495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. CDC Office of the Associate Director for Policy and Strategy. Health in all policies. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/policy/hiap/index.html. Accessed April 18, 2022.

- 36. Pleasant VA, Griggs JJ.. Contemporary residential segregation and cancer disparities. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(25):2739-2741. doi: 10.1200/JClinOncol.21.01328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martinussen T, Vansteelandt S.. On collapsibility and confounding bias in Cox and Aalen regression models. Lifetime Data Anal. 2013;19(3):279-296. doi: 10.1007/s10985-013-9242-z/figures/3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article were provided by SEER-Medicare with permission under a data use agreement. Per the data use agreement, data will not be shared. However, SEER-Medicare data are available to investigators for research purposes and may be requested from SEER-Medicare at: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seermedicare/obtain/. The census tracts boundaries are publicly available on the US Census website at https://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2010&layergroup=Census+Tracts; and HOLC boundaries are available on the Mapping Inequality Website at the University of Richmond Digital Scholarship Lab at: https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=5/39.1/-94.58&text=downloads).