Abstract

Art-of-living allows individuals to live a contemplative, mindful, and active life to attain well-being. This study demonstrates the development and implementation of an art-of-living training intervention to nurture positivity among Pakistan’s university students during COVID-19. To ensure the efficacy of teaching and learning during the second wave of the pandemic, the intervention was imparted through a blended learning approach comprising two modes: (1) online learning and (2) offline personal and collaborative learning. This approach was based on the emotionalized learning experiences (ELE) format to make learning more engaging, permanent, and gratifying. The study comprised 243 students randomly assigned to an experimental group (n = 122) and a wait-list control group (n = 121). Growth curve analysis indicated that positivity together with the components of art-of-living—self-efficacy, savoring, social contacts, physical care, and meaning—and overall art-of-living increased at a greater rate in the experimental group than in the control group from pretest to posttest and from posttest to follow-up measurement. The analysis provided an all-encompassing view of how positivity developed in the two groups over time. There were significant variations in participants’ initial status (intercepts) and growth trajectories (slopes). The influence of participants’ initial positivity scores suggested that students with high initial positivity scores had a slower increase in linear growth, whereas those with low initial positivity scores had a faster increase in linear growth over time. The success of the intervention may be attributed to the dimensions of ELE—embodied in the two modes—and fidelity to intervention for effectively implementing the blended learning approach.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10902-023-00664-0.

Keywords: Art-of-living, Positivity, Emotionalized learning experiences, Online learning and offline personal and collaborative learning modes, COVID-19

Introduction

Based on the philosophical thoughts by Schmid (2013), art-of-living is a conscious, reflected, and active way of life. According to Schmitz (2016), art-of-living has a long-term perspective focusing on identifying the possibility for enriching one’s future life and implementing practical strategies for attaining life satisfaction. Art-of-living is a holistic integrative model incorporating fifteen fundamental constructs of positive psychology (i.e., coping, serenity, savoring, shaping of living conditions, physical care, integration of different areas of life, openness, optimisation, positive attitude towards life, self-actualisation, self-knowledge, self-determined way of life, self-efficacy, meaning, and social contacts) and two meta constructs (i.e., reflection and balance) pertinent for maintaining internal relationships or equilibrium among the fifteen components (cf. Schmitz & Schmidt, 2014). Art-of-living components—each having a sound theoretical foundation—are malleable and can be taught and learned to nurture well-being. As such, art-of-living can be consciously developed through active effort and training (Schmid, 2013). This research is based on the development and implementation of an art-of-living training intervention to nurture positivity among Pakistan’s university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Positivity embodies the essence of life satisfaction, self-esteem, and optimism to foster optimal functioning (Caprara et al., 2012). According to Diener et al. (2000), positivity is a tendency to evaluate aspects of one’s life as good. The predominant objective of this research is to assess the efficacy of an art-of-living intervention in terms of the development of its five components—self-efficacy, savoring, social contacts, physical care, and meaning—as well as positivity among university students from pretest to posttest and six months later (follow-up measurement). The intervention is imparted through a blended learning approach based on the ELE format (explained in the Section, Art-of-Living Intervention Developed for this Study) to make learning more engaging, permanent, and gratifying to enable participants to apply the lessons learned to their distinct contexts (cf. Green, 2023).

Pursuing an art-of-living lifestyle can be useful for any individual and therefore it may be important to intentionally enhance it through training interventions and empirically evaluate its efficacy (Lang & Schmitz, 2016). This research is important because of six major reasons. First, it supports the importance of developing art-of-living—a relatively new concept of well-being—among university students in the collective culture of Pakistan and as such makes a valuable contribution to the literature on well-being. This is among the few positive psychology interventions (PPIs) that have been designed and implemented for Pakistani university students (e.g., Green, 2021, 2022a).

Second, majority of the previous psychological interventions—e.g., compassion interventions, cognitive therapy interventions, expressive writing interventions, mindfulness interventions, multi-theoretical interventions, character strengths interventions, gratitude interventions, and multicomponent PPIs—have focused on furthering subjective well-being, psychological well-being, affectivity, and a combination of subjective and psychological well-being (cf. meta-analysis by van Agteren et al., 2021). This is in all likelihood the first psychological intervention that furthers positivity among university students and that too amid the second wave of COVID-19.

Third, most of the PPIs are designed to train just one component/construct (Hone et al., 2014); however, this PPI combines five components of art-of-living and in intentionally training them based on the recommendation of prior art-of-living studies (Lang et al., 2018; Lang & Schmitz, 2016; Schmitz & Schmidt, 2014). It is pertinent to note that each component of art-of-living may support the development of its other components as well (Lang & Schmitz, 2016) and may therefore synergistically facilitate the development of positivity.

Fourth, this is the first study to test the long-term efficacy of an art-of-living intervention in relation to a wait-list control group, which serves as a yardstick for evaluating its effectiveness based on the difference in the development of positivity, the five components of art-of-living, and overall art-of-living in the two groups from pretest to follow-up measurement (Kinser & Robins, 2013). Further, having a follow-up measurement is pertinent for determining the efficacy of the intervention beyond posttest. Usually, the influence of an intervention does not become evident until six months after posttest (sleeper effects) because participants require time to internalize the knowledge acquired from it and opportunities to apply that knowledge to their unique contexts (Green, 2022a; Quinlan et al., 2012). Hence, this research aims at providing more robust results than the previous art-of-living interventions.

Fifth, this is perhaps the first psychological intervention that uses a growth curve analysis to offer an all-encompassing view of the development of an outcome variable (i.e., positivity) over time based on university students’ intercepts and slopes (growth parameters). Growth curve modeling estimates inter-individual variability in intra-individual patterns of change over time (Bollen & Curran, 2006), that is, between-person differences in within-person change. The within-person change or trajectories can vary from individual to individual. For example, the trajectories may be flat (depicting no change). These may also be systematically increasing or decreasing over time (Curran et al., 2010). Of note is that each student has a different development trend based on his or her own intercept (initial status) and slope (rates of changes over time; Shek & Ma 2011). Fundamentally, each student has a different initial score based on which his or her trajectory is developed over time. This experimental study is most likely the first to examine how students’ scores on an outcome variable develop over time based on their initial scores on it.

Lastly, this intervention is imparted through a novel blended learning approach based on (1) online learning and (2) offline personal and collaborative learning modes. Embodied in the dimensions of ELE, this approach demonstrates a modus operandi for ensuring the efficacy of teaching and learning during the second wave of the pandemic (Green, 2022b, 2023; Bao 2020). The ELE format has also been successfully used in previous in-class intervention studies (Green, 2019a, 2023; Green & Batool, 2017). This research demonstrates the application of the ELE format to blended learning to enrich the teaching-learning process for real learning and development to occur. This blended learning approach is not only beneficial for imparting academic courses and PPIs during the pandemic, but also holds great promise post-pandemic for diverse intentional learning and capacity-building purposes. Hence, this contribution advances literature on affective learning as well.

Theoretical Framework

Positivity

Positivity reflects a positive view of one’s self, one’s life, one’s future, and one’s confidence in others. For instance, having faith in the future and looking forward to it with hope and enthusiasm, being satisfied with oneself and one’s life, being proud of many things in life, feeling confident in oneself, and being able to count on others when in need (Caprara et al., 2012). Kozma et al. (2000) assert that positivity is a general dispositional determinant of subjective well-being operating much in the same manner as a trait and may account for individual variation and stability in happiness despite environment change.

Importance of Developing Positivity Among Pakistan’s University Students

Positivity was considered a relevant outcome of the art-of-living intervention because of the continuous negative effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on people’s lives. University students have been experiencing considerable uncertainty on account of the pandemic (Lim & Javadpour, 2021), which has unquestionably disrupted their academic life (Chaturvedi et al., 2021). Research has indicated that in Pakistan, university students’ mental health has been severely affected by the pandemic (Qazi et al., 2021). Many students have been experiencing fear, depression, anxiety, and stress because of the pandemic (Aqeel et al., 2020; Green & Yıldırım, 2022; Green et al., 2022a; Kausar et al., 2021; Salman et al., 2020). One of the major sources of mental distress among Pakistani students is the fear of their loved ones contracting the virus (Green et al., 2022a; Salman et al., 2020). Further, the pandemic has had a negative effect on university students’ academic performance as well as threatened their academic future (Green et al., 2022a; Kaleem et al., 2020). Because of the problems associated with the online mode of education, many students have been anxious about losing an academic year (Qazi et al., 2021). It is much pertinent to mention here that positivity has been shown to be strongly related to well-established measures of well-being and adjustment (Caprara et al., 2012). In light of the aforementioned, advancing positivity among Pakistan’s university students was considered pertinent.

Art-of-Living Components Selected for this Study

Self-efficacy reflects the conviction in one’s own abilities to address challenges (Schmitz & Schmidt, 2014). This component measures a general sense of perceived self-efficacy (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995) reflecting the belief that one can complete novel or difficult tasks, or cope with hard times in various domains of human functioning (Schwarzer, 1992). Self-efficacy was selected as a component of art-of-living for this research predominantly because the internal resources (e.g., persistence, self-assurance, fortitude, ingenuity, and recovery from setback; Green, 2020) instilled by generalized self-efficacy as a positive resistance resource factor enable individuals to face adversity (e.g., challenges associated with COVID-19) without negative consequences (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995). Moreover, generalized self-efficacy has been shown to relate to as well as predict psychological well-being, subjective well-being (Green, 2020), and academic achievement (Green, 2019b). Furthermore, research during the pandemic suggests that moderate and high levels of generalized self-efficacy shield the negative effects of higher levels of academic anxiety on academic self-efficacy over time (Green, 2022b).

Savoring implies intentionally placing one’s attention on positive experiences and altering one’s thoughts and behaviors in ways that enhance and prolong positive feelings (Bryant et al., 2011). In this study, savoring was conceptualized as savoring the moment keeping in view its actual conceptualization by Schmitz and Schmidt (2014). Savoring the moment represents the ability to create, strengthen, and linger positive emotions connected to positive events in the moment (Hurly & Kwon, 2012). As such, savoring may help individuals in developing coping resources for alleviating the persistent negative influence of the pandemic (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004; Broaden-and-Build theory of positive emotions). Savoring has been shown to relate to such well-being measures as life satisfaction and positive affect (Hurly & Kwon, 2012). Hence, savoring was considered as a component of art-of-living in this study.

Social contacts, as a component of art-of-living, suggest having good relationships (Schmitz & Schmidt, 2014). Ryff’s (1989) positive relations with others scale captures the essence of social contacts as conceptualized by Schmitz and Schmidt (2014). It focuses on having sincere, gratifying relationships with others; being empathetic, affectionate, and concerned regarding the well-being of others; and understanding the give and take aspect of human relations (Ryff & Keynes, 1995). Research indicates a positive association between positive relations with others and life satisfaction (Green, 2020). Having trusting and fulfilling relationships with others during the pandemic may be pertinent for university students to receive and offer emotional support. Research suggests that feelings of warmth, closeness, friendship, kinship, and understanding triggered by emotional support may provide university students valuable resources to minimize the influence of the pandemic-related academic stressors on mental well-being (Green et al., 2022b). Therefore, we considered social contacts germane to this study.

Physical care suggests being mindful of one’s body (Schmitz & Schmidt, 2014), i.e., eating a healthy and balanced diet, watching one’s weight and exercising on a regular basis, staying physically fit (Hey et al., 2006), and adhering to COVID-19 preventive behaviors. Research indicates that physical health (Bae et al., 2017) and consumption of healthy foods (André et al., 2017) are positively related to life satisfaction. We believe that physical care is of utmost significance during the pandemic because physical inactivity and long-term sedentary sitting during home confinement have had an undesirable influence on well-being and quality of life (Qi et al., 2020). Furthermore, adherence to COVID-19 preventive behaviors has also been emphasized (cf. Green & Yıldırım, 2022). Thus, an art-of-living intervention focusing on boosting physical health may be much beneficial amid the pandemic.

Meaning implies having clarity of purpose in life and knowing where one stands in life (Schmitz & Schmidt, 2014). According to Steger (2012), meaning provides a connection to something larger than oneself and fosters feelings that life is precious and worthwhile. Meaning in life has been shown to relate to psychological well-being (García-Alandete, 2015), life satisfaction, hope (Karataş et al., 2021), and happiness (Li et al., 2019). The pandemic has also had an adverse effect on the sense of purpose in life of students in higher education and hence interventions meant for rediscovering meaning in life are most likely crucial for managing the psychological effects of COVID-19 and navigating through these challenging times (de Jong et al., 2020). Research has also suggested that increased meaning in life is associated with lower anxiety and emotional stress during the COVID-19 crisis (Trzebiński et al., 2020). Considering the above, we selected meaning as the fifth component of art-of-living for this research.

Art-of-Living Interventions

Research on art-of-living is sparse as the construct is fairly new (Schmitz, 2016). In the scholastic context, results of the first intervention based on secondary school students (ages 16–19) indicated that art-of-living components (coping, self-knowledge, positive attitude towards life, savoring, and physical care) increased significantly for the two training conditions (cognitive training and combination of cognitive and body-focused training) as compared to the control group. In the second intervention based on primary school students (ages 8–11), results showed that overall art-of-living and its components (savoring, positive attitude towards life, and serenity) improved as a result of the intervention. Also, students’ quality of life was enhanced significantly in the training group than in the wait-list control group. In both interventions, participants were randomly assigned to the groups (Lang & Schmitz, 2016). Art-of-living training has also been conducted in the clinical-therapeutic context for adolescents (Lang et al., 2018). Results indicated that from pretest to posttest, overall art-of-living and six of its components (meaning, self-knowledge, savoring, openness, integration of different areas of life, and self-efficacy) as well as life satisfaction increased in the training conditions (needs-oriented and predefined) than in the wait-list control group. Furthermore, there was a greater decrease in depression from pretest to posttest in the two training conditions as compared to in the control group. It is noteworthy that from posttest to follow-up measurement (three weeks after posttest), the two experimental groups were not compared with the control group. Results showed that life satisfaction, overall art-of-living, and five of its components increased during this period in the two experimental groups. In addition, depression decreased in these two groups from posttest to follow-up measurement.

Art-of-Living Intervention Developed for this Study

The art-of-living intervention incorporated the elements/factors that have contributed to result-oriented PPIs as indicated in different meta-analyses. We used a wait-list control group and a sufficiently long intervention period (32 h of online classes, 8 h of virtual office hours for addressing student queries, and time spent by students on offline tasks) for the prescription to take effect (Carr et al., 2020; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Further, to promote change in learners’ behaviors, the intervention focused on multiple positive learning activities, motivating the less emotionally engaged participants, and encouraging all participants to keep a record of the lessons learned from the intervention sessions (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Also, a blended learning approach was implemented because online interventions have generally been less effective than face-to-face interventions in the past (cf. Koydemir et al., 2020). Fundamentally, the online and offline learning modes complement each other based on capitalising on the advantages of each to nurture greater learning capabilities (Bao 2020). Of note is that fidelity to intervention was observed to successfully implement the two learning modes (cf. Online Resource 1 for details).

Emotionalized Learning Experiences Format

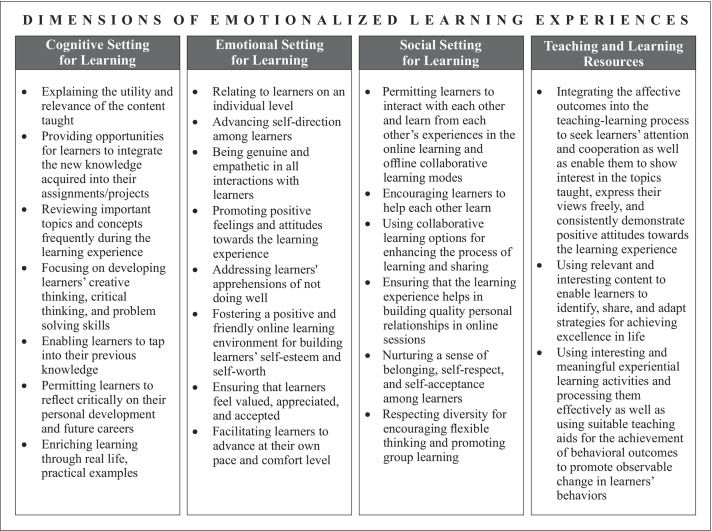

ELE are geared towards providing affective experiences to increase engagement and sustain motivation in the learning process based on a learner-centric environment (Green, 2023). ELE focus on integrating affective outcomes into the teaching-learning process (Patel, 2010) based on high value affective content (i.e., interesting, current, and need-relevant content) to affect learners emotions, attitudes, and beliefs to secure their cooperation to learn well (Green et al., 2020a). The training intervention used high value affective content to actively and meaningfully engage participants in it. Previous research has also indicated that the intervention content is more important than the manner in which it is delivered (Green, 2019a; Green & Batool, 2017). ELE foster comprehensive or whole body learning, as the affective outcomes make possible the attainment of cognitive and psychomotor outcomes (Patel, 2010) to affect noticeable change in learners’ behaviors at the end of a learning experience (Thoen & Robitschek, 2013). The intervention content and associated behavioral outcomes of the art-of-living intervention are available as Online Resource 2. These details are pertinent for replicating the intervention. Figure 1 presents the four dimensions of ELE (the cognitive setting for learning, the social setting for learning, the emotional setting for learning, and teaching and learning resources; Green, 2019a), which form the affective learning environment (Green, 2019a; Green & Batool, 2017). These dimensions incorporate the Principles of Significant Learning (Rogers, 1969) and the Adult Teaching and Learning Assumptions (Knowles, 1990) to enhance learning and sharing through an authentic, empathetic, trustworthy, and accepting learning environment. The details of these learning principles are available as Online Resource 3.

Fig. 1.

The Four Dimensions of Emotionalized Learning Experiences

Online Learning Mode

This comprised 16 online classes that covered six modules over four weeks (32 h). The duration of each online class was two hours and the platform used was Microsoft Teams. Each online class enabled the facilitator to develop affective connections with students—a pertinent aspect of the emotional setting for learning (Green, 2019a)—through frequent one-on-one interaction with the students. Details of the online sessions, online activities, and offline activities per module are available as Online Resource 4. The different types of online sessions incorporated into the online mode of the intervention are explained in the following paragraphs.

The interactive lecturette sessions used PowerPoint presentations and focused on maintaining students’ interest and engagement based on questions and creative whips as well as explaining the importance and utility of the content covered to their personal and professional lives (cognitive setting for learning and teaching and learning resources).

Individual activity sessions featured such activities as interpreted lecture, admirable individuals, and self-reflection (teaching and learning resources). These enabled participants to demonstrate their analytical, critical, and creative thinking skills (cognitive setting for learning). A brief discussion followed the activities in which volunteers reported their findings.

The question and answer sessions tested students’ knowledge and comprehension as well as addressed their queries about topics that needed further clarification (cognitive setting for learning). A discussion board was linked to the sessions enabling students to post their questions in advance.

Sessions for students to share their findings of experiential learning activities tasked as homework (offline personal and collaborative learning mode) were an important aspect of the online learning mode. With regard to small group tasks, each group leader shared his or her group’s findings in not more than 90 s with the entire class (social and cognitive settings for learning). With regard to individual tasks, volunteers were asked to briefly report their findings. Feedback was provided by the facilitator after each group leader or volunteer had reported his or her findings (teaching and learning resources). The facilitator ensured that the activities were properly processed to affect students’ emotions and attitudes regarding art-of-living (emotional setting for learning). As part of the virtual working hours—other than the time allotted for online classes—WhatsApp or Zoom was used to address content-related queries (emotional setting and teaching and learning resources).

The online collaborative learning sessions (social settings for learning) comprised activities for pairs, triads, and quartets to enhance the process of learning and sharing (teaching and learning resources) and enabled participants to demonstrate their higher-order thinking skills (cognitive setting for learning). Findings were reported by volunteer group leaders and learning partners in not more than 60 s.

The reflecting on module sessions entailed asking volunteers to present three pertinent lessons learned from the previous module in not more than 60 s (Green, 2023; cognitive setting for learning and teaching and learning resources).

Offline Personal and Collaborative Learning Mode

Four elements were incorporated into this mode. First, a self-instructional study guide was used for offline personal learning and to support online learning (teaching and learning resources). Second, the experiential activities tasked as homework (teaching and learning resources) included individual, pair, and group activities for advancing students’ analytical, creative, and problem-solving skills (cognitive setting for learning). Students used WhatsApp and Zoom (teaching and learning resources) for completing the group and pair activities (social setting for learning). Third, reading assignments entailed studying an assigned topic from the web resources listed in the study guide (teaching and learning resources) to answer facilitator’s conceptual questions in the relevant online class (cognitive setting for learning). Also, participants were asked to read and watch inspirational material (teaching and learning resources) to write a one-pager on the lessons learned from it regarding the art-of-living (cognitive setting for learning). Lastly, one-pager assignments (teaching and learning resources) allowed students to (a) look up a topic and write their views about it and (b) recommend strategies for mastering a component of art-of-living (cognitive and emotional settings for learning).

Intervention Content

The intervention content was covered through the online learning and offline personal and collaborative learning modes. The first module provided an introductory perspective of art-of-living. The other five were each devoted to a component of art-of-living. Annexure 1 presents the description of the experiential activities used in the two learning modes and the content covered through them. The details of the content of the six modules and associated behavioral outcomes are available as Online Resource 2. In addition, sample PowerPoint slides are available as Online Resource 5.

Merits of Growth Curve Modeling

Growth curve modeling was used because of three major reasons. First, it is a flexible and robust approach when handling missing data, as it is very common to encounter issues of participant dropout in longitudinal studies. This overcomes the limitations inherent in other conventional statistical techniques (e.g., ANOVA with repeated-measures) that do not cater to missing data (Shek & Ma, 2011). Second, gaining insights into the patterns of change as well as the effects at the individual and group levels provide an all-inclusive picture of developmental changes over time (Miner & Clarke-Stewart, 2008). Third, growth curve modeling is more powerful as compared to other statistical methods (e.g., ANOVA and MANOVA) in analyzing the effects pertaining to repeated measures. Growth curve modeling fits the true covariance structure to the data (cf. Kowalchuk et al., 2004). In essence, selecting an appropriate covariance structure for the growth model likely reduces the error variance allowing the specification of a correct model to conceptualize the patterns of change over time (Shek & Ma, 2011).

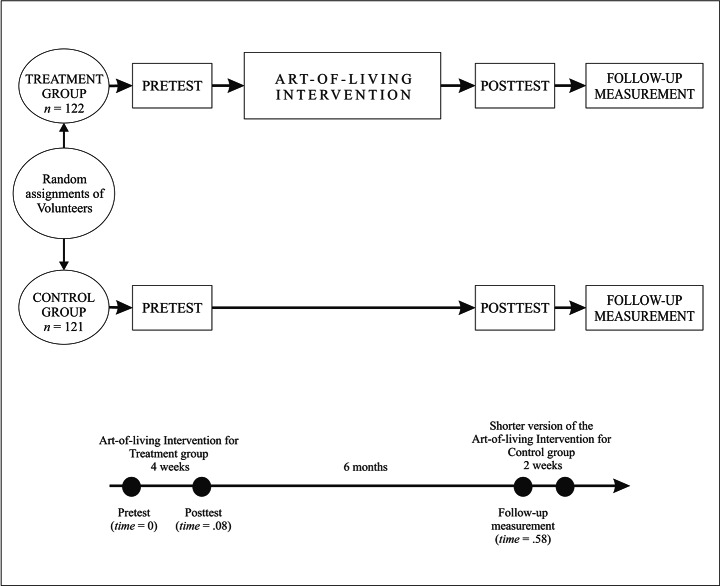

In this three-wave longitudinal study, time was coded as 0 for the first measurement occasion (pre-test) to represent the intercept as the true initial status. As the intervention was one-month long (4 weeks), therefore, the second measurement occasion (posttest) was codes as 0.08 (first month divided by 12 months—1/12). Finally, the third measurement occasion (follow-up measurement) was six months after the intervention, therefore, it was coded as 0.58 (seventh month divided by 12 months—7/12).

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Research Question 1. How did the intervention group fare on art-of-living and positivity as compared to the control group from pretest to posttest and from posttest to follow-up measurement?

Hypothesis 1

As compared to the control group, the scores pertaining to positivity (outcome variable), self-efficacy, savoring, social contacts, physical care, meaning, and overall art-of-living will increase at a greater rate in the intervention group over each time interval.

Research Question 2. How did the participants’ positivity scores develop from pretest to follow-up measurement based on the growth parameters?

Hypothesis 2

There will be significant variations in students’ positivity scores at the initial status.

Hypothesis 3

There will be significant variations in students’ growth trajectories of their positivity scores.

Hypothesis 4

There will be a slower linear increase in positivity scores from pretest to follow-up measurement among students with high initial positivity scores than among those with low initial positivity scores.

Method

In this section, we report (a) how we allocated the study participants to the two groups; (b) how we addressed the problem of attrition and missing data; (c) the details of the six measures used in the study and how we determined their suitability for administering them to the participants; (d) the research procedure including the ethical approval, the modalities for conducting the intervention, and research ethics; (e) the details of the research design; and (f) how data were analyzed.

Participants

This intervention study comprised 243 bachelor’s and master’s students—103 (42%) women and 140 (58%) men—studying at a midsized university located in Islamabad. Their average age calculated to 24.11 years (SD = 3.57). A research randomizer divided the study sample into two groups, experimental/intervention group (n = 122; 44% women and 56% men) and control group (n = 121; 40% women and 60% men). The CONSORT flow diagram shows the flow of participants in the two groups at the three stages of the study (cf. Online Resource 6).

Further, this research used no inclusion/exclusion criteria and therefore no restrictions were imposed on participation. Study participants were enrolled in the following disciplines: Psychology (27%), Computer Sciences (23%), Economics (20%), Education (16%), and Business Administration (14%). Additionally, a priori power analysis in G*Power for MANOVA (Global effects) based on a medium effect size of 0.09, an alpha of 0.05, power of 0.8, two groups, and 7 response variables suggested a total sample size of 168 participants (Faul et al., 2013). Hence, a sample size of 243 students was more than sufficient for this research.

Measures

Pilot testing assessed the validity (through confirmatory factor analysis; CFA) and reliability (based on the value of Cronbach’s alpha) of the six scales used in the study. This determined the appropriateness of administering the scales to the study participants. The items in the online survey were properly shuffled before study participants were asked to complete it at the three time points. Each construct was assessed based on the total score obtained on its measure. Also, the total scores of self-efficacy, savoring, social contacts, physical care, and meaning were added to assess the overall art-of-living.

Positivity

This was assessed through the 8-item Positivity Scale by Caprara et al. (2012). Participants rated the items (e.g., “I look forward to the future with hope and enthusiasm”) on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). According to Caprara and colleagues, the internal consistency reliability of the scale calculated to 0.76. Further, CFA indicated a good model fit, i.e., χ2 (18, N = 247) = 29.16, p = .075; χ2/df = 1.62; RMSEA = 0.05; RMSEA 90% CI [0.01; 0.08]; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; NFI = 0.95; GFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.04. Factor loadings ranged from 0.48 to 0.72. Higher scores on the scale suggest higher levels of positivity. Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha indicated good internal consistency of the scale (α = 0.83).

Self-Efficacy

The 10-item Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale by Schwarzer and Jerusalem (1995) was used to assess this component of art-of-living. Measuring a general sense of perceived self-efficacy, a sample item in the scale is: “Thanks to my resourcefulness, I know how to handle unforeseen situations.” The scale uses a Four-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all true; 4 = exactly true). However, this study used a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). In a study by Green (2020), the internal consistency of the scale calculated to 0.94. Furthermore, CFA indicated a good model fit, i.e., χ2 (27, N = 247) = 28.08, p = .041; χ2/df = 1.04; RMSEA = 0.01; RMSEA 90% CI [0.0; 0.07]; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; NFI = 0.95; GFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.03. Factor loadings ranged from 0.45 to 0.67. Higher scores on the scale suggest greater self-efficacy. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha indicated good internal consistency of the scale (α = 0.88).

Savoring

This was assessed through the 8-item Savoring the Moment subscale (STMS) of the Savoring Beliefs Inventory by Bryant (2003). The items (e.g., “I know how to make the most of good time”) are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree), but, in this study, we used a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). In five college samples, the internal consistency of the subscale ranged from 0.68 to 0.83 as reported by the author. Next, CFA indicated a good model fit, i.e., χ2 (14, N = 247) = 21.69, p = .17; χ2/df = 1.55; RMSEA = 0.04; RMSEA 90% CI [0.0; 0.08]; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.97; NFI = 0.96; GFI = 0.98; SRMR = 0.03. Factor loadings ranged from 0.45 to 0.64. Higher scores on the scale suggest higher levels of savoring. Further, Cronbach’s alpha indicated good internal consistency of the STMS (α = 0.84).

Social Contacts

The Positive Relations with Others subscale (PRWOS) of the 54-item Psychological Well-being scale by Ryff (1989) was used to assess this component of art-of-living. The 9 items of the PRWOS (e.g., “People would describe me as a giving person, willing to share my time with others;” α = 0.74) are rated on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree). However, in this study, we used a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly agree; 5 = strongly disagree). Furthermore, CFA indicated a good model fit, i.e., χ2 (26, N = 247) = 34.21, p = .13; χ2/df = 1.32; RMSEA = 0.03; RMSEA 90% CI [0.0; 0.07]; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; NFI = 0.95; GFI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.04. Factor loadings ranged from 0.42 to 0.60. Higher scores on the PRWOS indicate that respondents have abundant social contacts/relationships. Also, Cronbach’s alpha indicated good internal consistency of the scale (α = 0.82).

Physical Care

The 9 items of the Body dimension of Wellness (BDW) subscale of the Body-Mind-Spirit Wellness Behavior and Characteristic Inventory (BMS-WBCI) by Hey et al. (2006) was used to assess physical care. The inventory uses a 3-point rating scale (1 = rarely/seldom; 3 = often/always), but, in this study we used a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). A sample item in the BDW is: “I maintain my fitness by exercising regularly and maintaining my weight.” In view of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was considered relevant to add the following item to the BDW: “I follow the necessary preventive measures to keep myself safe from the coronavirus.” The internal consistency of the BDW calculated to 0.87 in a study by Green et al. (2020a). Next, CFA indicated a good model fit, i.e., χ2 (34, N = 247) = 44.52, p = .09; χ2/df = 1.31; RMSEA = 0.04; RMSEA 90% CI [0.0; 0.06]; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.98; NFI = 0.95; GFI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.04. Factor loadings ranged from 0.51 to 0.74. Higher scores on the BDW indicate greater physical care. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha indicated excellent internal consistency of the scale (α = 0.90).

Meaning

This was assessed through the 5-item presence of meaning subscale (PMS) of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) by Steger et al. (2006). The MLQ uses a 7-point rating scale (1 = absolutely untrue; 7 = absolutely true). However, in this study, participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). A sample item in the PMS is: “I understand my life’s meaning.” According to the authors of the MLQ, the internal consistency reliability of PMS calculated to 0.86. Furthermore, CFA indicated a good model fit, i.e., χ2 (4, N = 247) = 8.64, p = .07; χ2/df = 2.16; RMSEA = 0.06; RMSEA 90% CI [0.0; 0.13]; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.96; NFI = 0.96; GFI = 0.98; SRMR = 0.03. Factor loadings ranged from 0.49 to 0.63. Higher scores on the PMS indicate a greater presence of meaning in life. Also, Cronbach’s alpha indicated good internal consistency of the PMS (α = 0.86).

Procedure

The Contemporary Research Initiative (CRI) obtained the necessary approval from the Research Ethics Committee for conducting the study. Next, CRI formally contacted the university to seek its approval for conducting the art-of-living intervention for its students. The university management was explained the nature and scope of the research study and its relevance during the pandemic through Zoom Meeting. After getting the approval, the modalities for conducting the intervention were finalized. The intervention was offered during January and February, 2021. The experimental group was offered online classes in two groups (n = 61; n = 61) for four weeks. Subgroup-1 was taught between 8:30 AM and 10:30 AM and the subgroup-2 between 11:00 AM and 1:00 PM on Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. Additionally, virtual working hours were scheduled from 9:30 AM to 11:30 AM on Wednesdays and Fridays for subgroup-1 and subgroup-2 respectively. Students in the wait-list control group (n = 61; n = 60) were offered a shorter version of the art-of-living training soon after the online administration of all measures pertaining to the follow-up measurement in August 2021. The art-of-living training was free for the study participants who were awarded a course completion certificate signed by the Dean. In addition, 5 marks were added to their sessional result (as class participation) pertaining to the course in which they scored the least. University students were informed about the art-of-living training by the Student Affairs Division through email and WhatsApp. The e-noticeboard also provided details about the intervention. Participation in the study was voluntary and appropriate informed consent was obtained from all the participants. They were also assured that the collected data will remain confidential. Most importantly, they were kept unaware of the concept of positivity.

The facilitator is a life coach who has extensive experience in positive psychology, instructional design, conducting experiential activities, and activity-based online teaching. The facilitator was kept unaware of the research questions and associated hypotheses.

Research Design

Based on an experimental design, this three-wave longitudinal study shows a comparison of individual growth trajectories. Bachelor’s and master’s students volunteered to participate in the study. Volunteers were randomly allocated to a wait-list control group and a treatment/experimental group. The research design is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Research Design of the Study

The fixed effects comprise time (coded as 0, 0.08, and 0.58 for the three time points respectively), the control (coded as 0) versus the treatment (coded as 1), and the time-by-treatment interaction. Additionally, as hypothesized, the experimental group will show a greater increase in the study variables immediately after the art-of-living intervention (time = 0.08) as well as six months after it (time = 0.58). This will be tested through a time-by-treatment/condition interaction based on the expectation that the two groups will have varying growth trends pertaining to positivity as well as the components of art-of-living and overall art-of-living.

Next, random effects in the growth model provide an all-encompassing view of the development of positivity from pretest (time = 0) to follow-up measurement (time = 0.58) by taking into consideration the difference between individual participants’ growth parameters (i.e., intercepts and slopes). As expected, there will be significant differences in university students’ positivity scores at the initial status (variance in intercepts) as well as growth trajectories (variance in slopes). Lastly, as hypothesized, there will be a slower linear increase in positivity scores of students with high initial positivity scores as compared to those with low initial positivity scores. This will be tested through the estimate of covariance between the intercepts and slopes based on the expectation that it will be negative and significant.

Data Analyses

With regard to the preliminary analyses, first, descriptives pertaining to the study variables at each time point were calculated. Second, the treatment group and the control group were compared before the intervention to check whether they were equivalent with regard to gender, age, and pretest scores on the study variables. Finally, we determined the intercorrelations among the three time points of positivity as well as among those of each component of art-of-living and overall art-of-living.

The main analysis comprised performing a growth curve analysis with hierarchical linear model (HLM) repeated measures data in SPSS based on the linear mixed modeling option. The analysis was based on two growth models, namely the conditional growth model (included the condition) and the unconditional growth model (did not include the condition). The two models were implemented for each study variable using the maximum likelihood estimation with an unstructured covariance structure for random effects and an identity covariance structure for error variance (Hesser, 2015). For comparing the two groups on positivity, art-of-living components, and overall art-of-living over time, the conditional model for each variable computed the following estimates of fixed effects: initial status of the variable, rate of growth, condition, and time-by-treatment (indicating the rate of growth of the variable in the treatment group). For gaining insights into the development of positivity scores from pretest (time = 0) to follow-up measurement (time = 0.58), the two models were analyzed. The conditional model provided a comprehensive picture of the development of positivity from pretest to follow-up measurement based on following estimates of random effects: variance in intercepts, variance in slopes, and covariance between the intercept and slopes. The unconditional model demonstrated how the heterogeneity in slopes could in part be accounted for by the inclusion of the condition predictor variable in the conditional model. In tandem with the conditional model, the unconditional model was used to compute the Pseudo-R2 for determining the extent to which the condition predictor variable accounted for the variance in participants’ slopes. Overall, data analysis and reporting was based on the approaches used by Heck et al. (2014) and Hesser (2015).

Additionally, we used the maximum likelihood estimation to manage missing data. This is an iterative process that identifies population parameter values having the highest probability of reproducing the sample data (cf. Enders, 2010). Providing increased statistical power as well as more accurate standard errors and estimates, it is a far superior alternative for handling missing data than the widely used last observation carried forward strategy as indicated in methodological studies (e.g., Lane 2008; Salim et al., 2008). The maximum likelihood estimation has also been used by many internet interventions (e.g., Hesser et al., 2012; Newby et al., 2013).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics pertaining to positivity as well as components of art-of-living and overall art-of-living at pretest, posttest, and follow-up measurement. Comparison of the groups before the intervention showed no statistically significant difference for gender (χ2 (1) = 0.35, p = .552) and age (F (1, 241) = 0.92, p = .338). Further, as part of growth curve analysis, the treatment variable in Table 2 shows that there was no significant difference between the two groups at the initial stage (i.e., before the intervention) for positivity (-0.20, p = .752), self-efficacy (-0.53, p = .487), savoring (-0.41, p = .591), social contacts (-0.30, p = .697), physical care (-0.04, p = .970), meaning (-0.02, p = .963), and overall art-of-living (-1.19, p = .618). Additionally, correlations among the three variables of positivity ranged from 0.44 to 0.66, self-efficacy from 0.45 to 0.76, savoring from 0.45 to 0.77, social contacts from 0.46 to 0.80, physical care from 0.54 to 0.79, meaning from 0.51 to 0.78, and overall art-of-living from 0.47 to 0.78.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics at the Three Time Points

| Variable | Control Group |

Treatment Group | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Positivity (time = 0) | 29.52 | 4.85 | 29.61 | 4.11 | 29.56 | 4.49 | |

| Positivity (time = 0.08) | 29.53 | 4.83 | 29.88 | 4.18 | 29.71 | 4.51 | |

| Positivity (time = 0.58) | 29.82 | 4.88 | 30.62 | 4.36 | 30.21 | 4.64 | |

| Self-efficacy (time = 0) | 35.65 | 5.91 | 35.59 | 5.34 | 35.62 | 5.62 | |

| Self-efficacy (time = 0.08) | 35.68 | 5.87 | 36.12 | 5.32 | 35.90 | 5.59 | |

| Self-efficacy (time = 0.58) | 35.95 | 5.89 | 37.30 | 5.52 | 36.61 | 5.75 | |

| Savoring (time = 0) | 30.60 | 5.91 | 30.46 | 5.72 | 30.53 | 5.80 | |

| Savoring (time = 0.08) | 30.63 | 5.94 | 30.83 | 5.78 | 30.73 | 5.85 | |

| Savoring (time = 0.58) | 30.92 | 5.88 | 32.10 | 6.13 | 31.49 | 6.02 | |

| Social contact (time = 0) | 34.61 | 6.47 | 34.54 | 5.56 | 34.58 | 6.01 | |

| Social contact (time = 0.08) | 34.68 | 6.41 | 34.96 | 5.61 | 34.82 | 6.01 | |

| Social contact (time = 0.58) | 35.04 | 6.33 | 36.03 | 5.75 | 35.54 | 6.06 | |

| Physical care (time = 0) | 34.62 | 6.91 | 34.46 | 7.78 | 34.54 | 7.35 | |

| Physical care (time = 0.08) | 34.70 | 6.99 | 34.83 | 7.97 | 34.76 | 7.48 | |

| Physical care (time = 0.58) | 35.04 | 6.99 | 35.93 | 8.37 | 35.47 | 7.69 | |

| Meaning (time = 0) | 18.90 | 2.89 | 18.99 | 3.02 | 18.94 | 2.95 | |

| Meaning (time = 0.08) | 18.91 | 2.74 | 19.22 | 3.08 | 19.06 | 2.91 | |

| Meaning (time = 0.58) | 19.21 | 2.57 | 19.99 | 3.43 | 19.59 | 3.04 | |

| Art-of-living (time = 0) | 154.37 | 17.42 | 154.04 | 18.07 | 154.21 | 17.72 | |

| Art-of-living (time = 0.08) | 154.60 | 17.10 | 155.68 | 17.89 | 155.13 | 17.46 | |

| Art-of-living (time = 0.58) | 156.32 | 16.81 | 161.34 | 18.78 | 158.77 | 17.93 | |

Table 2.

Development of Scores of Positivity as well as Art-of-Living (Overall) and its Components (N = 243)

| Estimated parameters | Positivity | Self-efficacy | Savoring | Social Contacts | Physical care | Meaning | Art-of-living | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | b | (SE) | p | b | (SE) | p | b | (SE) | p | b | (SE) | p | b | (SE) | p | b | (SE) | p | b | (SE) | p |

| Initial status | 29.14 | 0.45 | 0.000 | 35.70 | 0.54 | 0.000 | 30.61 | 0.54 | 0.000 | 34.63 | 0.55 | 0.000 | 34.60 | 0.70 | 0.000 | 18.93 | 0.28 | 0.000 | 154.50 | 1.69 | 0.000 |

| Time (Rate of growth) | 0.68 | 0.19 | 0.001 | 1.05 | 0.40 | 0.009 | 0.88 | 0.28 | 0.002 | 0.75 | 0.24 | 0.002 | 1.85 | 0.28 | 0.000 | 0.44 | 0.14 | 0.002 | 5.01 | 0.94 | 0.000 |

| Treatment (Condition) | − 0.20 | 0.63 | 0.752 | − 0.53 | 0.77 | 0.487 | − 0.41 | 0.76 | 0.591 | − 0.30 | 0.78 | 0.697 | − 0.04 | 0.99 | 0.970 | − 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.963 | -1.19 | 2.37 | 0.618 |

| Time by condition (Rate of growth of variable in treatment group) | 1.42 | 0.27 | 0.000 | 2.15 | 0.56 | 0.000 | 1.83 | 0.40 | 0.000 | 1.91 | 0.34 | 0.000 | 1.65 | 0.39 | 0.000 | 1.40 | 0.20 | 0.000 | 9.19 | 1.30 | 0.000 |

Comparing the Two Groups on Positivity and Art-of-Living Components Over Time

The estimates of fixed effects in Table 2 show that university students in the control group started with a mean positivity score of 29.14, mean self-efficacy score of 35.70, mean savoring score of 30.61, mean social contacts score of 34.63, mean physical care score of 34.60, mean meaning score of 18.93, and mean overall art-of-living score of 154.50. On average, students’ positivity scores in the control group increased by 0.68 points over each time interval, that is, from pretest to posttest and from posttest to follow-up measurement. The same held true for overall art of living and its components, that is, the control group’s scores of self-efficacy increased by 1.05 points, savoring by 0.88 points, social contacts by 0.75 points, physical care by 1.85 points, meaning by 0.44 points, and overall art-of-living by 5.01 points.

Furthermore, as per Table 2, there was a significant interaction effect of time by condition for positivity (1.42, p < .001), self-efficacy (2.15, p < .001), savoring (1.83, p < .001), social contacts (1.91, p < .001), physical care (1.65, p < .001), meaning (1.40, p < .001), and overall art-of-living (9.19, p < .001). This signifies that university students who were offered the targeted art-of-living intervention increased their positivity scores (1.42 points), self-efficacy scores (2.15 points), savoring scores (1.83 points), social contacts scores (1.91 points), physical care scores (1.65 points), meaning scores (1.40 points), and overall art-of-living scores (9.19 points) at a greater rate over each time interval than their peers in the control group. This finding suggests that as compared to the control group, the treatment/experimental group had a stronger positive linear relationship between time and positivity scores, between time and scores of each component of art-of-living, and between time and overall art-of-living scores. Based on the aforementioned results Hypothesis1 was confirmed.

Development of Positivity Scores from Pretest to Follow-up Measurement

Participants’ positivity scores—regardless of assignment to groups—increased on average by approximately 1.42 points per time interval (Table 3). More importantly, the between-subject variance in intercepts, the between-subject variance in slopes, the role of the condition predictor, and the covariance between the intercepts and slopes were examined to obtain an all-encompassing view of the development of positivity scores from pretest to follow-up measurement.

Table 3.

Estimates of Fixed and Random Effects for Positivity (N = 243)

| POSITIVITY | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated parameters | Unconditional Model | Conditional Model | ||||

| Fixed effects | b | (SE) | p | b | (SE) | p |

| Initial status | 29.04 | 0.32 | 0.000 | 29.14 | 0.45 | 0.000 |

| Time (Rate of growth) | 1.42 | 0.14 | 0.000 | 0.68 | 0.19 | 0.001 |

| Treatment (Condition) | - | - | − 0.20 | 0.63 | 0.752 | |

| Time by condition (Rate of growth of variable in treatment group) | - | - | 1.42 | 0.27 | 0.000 | |

| Random effects | ||||||

| Variance in intercepts (initial level) | 24.36 | 2.22 | 0.000 | 24.35 | 2.22 | 0.000 |

| Variance in slopes | 3.31 | 0.48 | 0.000 | 2.81 | 0.43 | 0.000 |

| Covariance between intercepts and slopes (influence of initial variable) | -2.00 | 0.75 | 0.008 | -1.85 | 0.71 | 0.009 |

| Residual | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.000 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.000 |

Pseudo-R2 = (variance in slopes of unconditional model - variance in slopes of conditional model) / variance in slopes of unconditional model

Pseudo-R2 = 0.15

Initial Status of Participants’ Positivity

Regarding students’ initial positivity (time = 0), results presented in Table 3 show that the variance in intercepts was significant, implying that there were significant variations in students’ positivity scores (24.35, p < .001) at the initial status even after controlling for the treatment variable. Hence, results confirm Hypothesis2.

End Status of Participants’ Positivity

With regard to the end status (time = 0.58), results show that the variance in slopes was also significant (2.81, p < .001). This showed that significant variations existed in university students’ growth trajectories while the condition variable modeled its fixed effect on the randomly varying slopes for time.

Heterogeneity in Slopes

Of note is that the heterogeneity in slopes is possibly in part because of the inclusion of the condition predictor variable in the model. This is likely why the variance associated with the random slope decreased from 3.31 to 2.81 (Table 3). Additionally, as there was a significant interaction effect of time by condition (1.42, p < .001); therefore, condition in all likelihood systematically explained some of the variance in individual slope estimates. Moreover, computing the Pseudo-R2 was considered pertinent for interpreting this random effect. Pseudo-R2 computes the proportion of the explained variance in the random effect by the condition predictor variable (Singer & Willett, 2003). The value of Pseudo-R2 therefore indicates that the condition predictor variable accounted for around 15% of the variance in students’ slopes.

In light of the results associated with the unconditional model and the conditional model, Hypothesis3 was confirmed.

Influence of Students’ Initial Positivity Scores

This was analyzed based on the covariance between the intercepts and slopes (linear growth parameters). Results indicate that the covariance between the intercepts and slopes was negative and significant (-1.85, p < .01), suggesting that university students with high initial positivity scores had a slower increase in linear growth, whereas those with low initial positivity scores had a faster increase in linear growth over time. Thus, results support Hypothesis4.

Discussion

An art-of-living intervention was developed for university students in Pakistan and imparted through a blended learning approach to ensure the efficacy of teaching and learning during the pandemic. Results suggest that positivity (outcome variable) increased at a greater rate over each time interval in the experimental group than in the control group. The same held true for self-efficacy, savoring, social contacts, physical care, meaning, and overall art-of-living. Previous art of living interventions (Lang et al., 2018; Lang & Schmitz, 2016) also indicate a greater increase in overall art-of-living and its components in the experimental conditions than in the control group from pretest to posttest. The same was true for the outcome variables in these studies, i.e., life satisfaction (Lang et al., 2018) and quality of life (Lang & Schmitz, 2016). However, these studies had a small sample size, which may have undermined the reliability of the results required for drawing solid conclusions. This study used growth curve modeling, a follow-up measurement, and a more than adequate sample size. Robust conclusions may therefore be drawn from the findings of this study.

In this study, the increase in positivity as well as the components of art-of-living and overall art-of-living at each time interval suggests that the intervention was successful in sustaining their development over time. Comparability of these results is restricted and as such future research on art-of-living interventions—based on growth curve modeling and a pretest-posttest-posttest design—is needed to properly validate them. It is much pertinent to mention here that previous PPIs based on university students have also been successful in sustaining the development of such outcome variables as life satisfaction (Rashid, 2004), thriving (Bu & Duan, 2019), and PERMA-oriented wellbeing (Green, 2022a) from pretest to posttest and from posttest to follow-up measurement.

With regard to the development of positivity from pretest to follow-up measurement in the two groups, results suggest that university students had significant variations in positivity scores at the initial level and significant variations in their growth trajectories of positivity scores. This is likely because each individual has a different initial status and rate of change over time (Shek & Ma, 2011). Essentially, the development of positivity (growth trajectories) in the two groups over time was based on students’ initial positivity scores. The influence of students’ initial positivity indicates that those with high initial positivity scores had a slower increase in linear growth rate, whereas those with low initial positivity scores had a faster increase in linear growth over time. This is perhaps because of the process of learning curves (cf. Anzai & Simon, 1979), implying that over time, limited improvement in positivity is possible for those participants who at the start of the intervention have a high level of positivity because their output (positivity) has most likely reached its natural limit (Harlow, 1949).

The long-term efficacy of the art-of-living intervention may have been because of observing intervention fidelity, which may have helped in the effective implementation of the two learning modes. Moreover, the learning principles (Knowles, 1990; Rogers, 1969) integrated into the dimensions of ELE may have made blended learning more active, engaging, and result-oriented. For example, with regard to the cognitive setting for learning, explaining the relevance and benefits of art-of-living and its components to participants (need to know and learners’ natural propensity to learn) during the intervention may have contributed to the intervention’s success. Previous research has also indicated the same for career interventions (Green, 2023; Green et al., 2020b). Also, the experiential activities enabling participants to demonstrate higher-order thinking skills likely deepened their learning (orientation to learning, freedom for threat to the self, and learning acquired through doing). Pertaining to the emotional setting for learning, the positive facilitator-student relations (developed based on addressing students’ queries as well as providing them meaningful advice and feedback on their participation in experiential activities) despite technology-mediated instruction may have enriched learning (motivation to learn and freedom from threat to the self). Prior research also suggests the importance of facilitator-student relations in enriching learning (Donaldson et al., 2019; Green, 2019a, 2023). In addition, the offline personal learning mode may have advanced considerable self-direction among participants to make learning more permanent and gratifying (self-directedness, motivation to learn, and learners’ participating responsibly in the learning process). In connection with the social setting for learning, the collaborative learning (based on pair and small group tasks) environment may have provided a sense of belonging to participants as well as renewed/strengthened their relationships to enhance learning (motivation to learn and freedom from threat to the self). Prior in-class intervention research has also indicated the same (Green, 2019a, 2021, 2023). Finally, regarding the dimension of teaching and learning resources, the affective value of the intervention content (need to know, orientation to learning, and relevance of the subject matter to learners’ purposes) and the interesting and meaningful experiential learning activities—as well as their proper processing—for attaining the behavioral outcomes (orientation to learning, freedom for threat to the self, and learning acquired through doing) in all possibility contributed to intervention effectiveness. Previous in-class intervention studies have also suggested the same (Green, 2019a, 2021, 2023, Green & Batool, 2017).

Theoretical Contribution

Results make important theoretical contribution. First, the study provides additional evidence that art-of-living can be developed through active effort (Schmid, 2013) suggesting that its components—self-efficacy, savoring, social contacts, physical care, and meaning—are malleable and can be trained. Second, results indicate that despite the unprecedented challenges brought about by the pandemic, the art-of-living intervention developed for this study may have bolstered students’ self-efficacy beliefs, prolonged their positive emotions, strengthened their relationships, enhanced their physical health, and helped them find or renew meaning in life to foster positivity among them. This lends credence to the belief that art-of-living may help individuals in managing stressful conditions and hardships (caused by the pandemic) to empower them to lead a fulfilling life (Lang & Schmitz, 2016). At the same time, it demonstrates the potential of art-of-living—as a multicomponent construct—for empowering students to muster the necessary resources for nurturing positivity amid the pandemic. Thus, this study makes the case for training multiple positive psychology constructs in an intervention to achieve positive results (Hone et al., 2014; Lang & Schmitz, 2016). It is noteworthy that this brand new art-of-living intervention may be equally effective for university students abroad. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, this study presents robust conclusions because of the use of growth curve modeling, a relatively large sample size, and a pretest-posttest-posttest design. It has therefore opened avenues of investigation for testing the potential of art-of-living with regard to attaining various positive outcomes. Third, it may be deduced from the concept of diminishing returns that university students having high positivity scores at pretest likely have lower incremental gains in positivity as compared to those having low initial positivity scores in the two groups. In connection with varying training/learning pre-conditions, these results extend prior studies by showing how positivity may be developed in the experimental and control groups over time. All in all, this study provides first evidence regarding the role of individual learning curves in art-of-living interventions. Fourth, the study also demonstrates the relevance of positivity as a measure for assessing students’ optimal functioning amid the pandemic. As an outcome of the art-of-living intervention, positivity is likely required by university students to navigate life with self-assurance, hope, equanimity, and contentment and in the process experience well-being. Fifth, self-efficacy—as a component of art-of-living—developed the most among participants over time likely because it reflects an optimistic self-belief, which may have inspired them to find solutions to problems and cope with unexpected situations (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic) with ingenuity, perseverance, and fortitude (Jerusalem & Schwarzer, 1992). Moreover, a perceived sense of general self-efficacy bolsters individuals’ motivation to proactively achieve their goals and craft their own futures (Diehl et al., 2006), as it is action-oriented and competence-based (Schwarzer et al., 2005). The same may have been applicable to the study participants. Sixth, the art-of-living components were assessed through established measures with good reliability and validity. Adequately reflecting people’s capacity to acquire art-of-living, these measures provide a much meaningful understanding and comprehensive assessment of the components than those used in previous art-of-living interventions (Lang et al., 2018; Lang & Schmitz, 2016). We therefore recommend the importance of using suitable measures for evaluating art-of-living interventions. Relevant to note is that the assessed art-of-living may vary because of the measures used and therefore appropriate measures may produce more robust results. Finally, this contribution recommends using the blended learning approach for imparting the art-of-living intervention as well as other well-being interventions during the pandemic and even after it. This is possibly because the four dimensions of ELE bolster the two learning modes, which collectively address the problems present in online learning, such as those associated with applying learner-centered approaches, using collaborative learning, fostering teacher-student interactions, and implementing innovative instructional strategies (Bao, 2020; Dhawan, 2020; Friedman, 2020). Moreover, the blended learning approach is cost effective. It may be of great value post-pandemic. For instance, this approach may be used by academic departments for enriching various credit or noncredit courses to increase student engagement and motivation to learn. In addition, the student affairs departments may use the two modes for implementing nonacademic programs to facilitate students’ transition from university to work. Last, but not least, blended learning may present a worthwhile mechanism for delivering PPIs and diverse capacity building programs for different populations.

Practice Implications

Findings indicate that the art-of-living intervention developed for this study successfully enhanced positivity, self-efficacy, savoring, social contacts, physical care, and meaning among university students. Education administrators may therefore consider offering the intervention to university students across Pakistan. Student affairs departments in collaboration with positive psychology intervention specialists may launch a series of workshops based on the two learning modes. Each workshop may be based on a component of art-of-living. The content of these workshops may need to have a high affective value to inspire students to identify, share, and adapt various techniques for developing/enhancing the components of art-of-living. Further, it is recommended to support the affective content with video activities based on short duration clips extracted from films and TV shows or downloaded from the YouTube. Video activities promote reflective learning to make learning more permanent and enjoyable. Niemiec and Wedding (2008) assert that films enhance the teaching-learning process by expanding and adding value to class discussions. Previous PPIs have also made good use of videos to support the intervention content (e.g., Green, 2021, 2022a, 2023; Smith et al., 2020). Video activities tasked as homework may present an interesting and meaningful option for augmenting offline personal learning as well.

Findings also suggest that the development of positivity among participants is based on their initial scores on it. As such, interventions for developing positivity may focus on participants’ initial level of positivity (training/learning pre-condition) so that appropriate strategies (e.g., intervention content with a high affective value, appropriately challenging experiential activities, and pairing students with different levels of initial positivity) may be implemented to augment their positivity accordingly and at the same time keep their interest alive in the training.

Enhancing the Current Art-of-living Intervention

We suggest some meaningful strategies for improving the current art-of-living intervention for university students. These strategies may also be incorporated into the workshops discussed in the previous section. First, to increase the efficacy of the two modes, pre-recorded sessions may be used to communicate such pertinent information as the intervention’s objectives, importance, and benefits (cognitive settings for learning); guidelines for getting the maximum out of the online sessions; and tips for improving offline personal and collaborative learning. Second, the recording of the interactive lecturette sessions may be made available for participants to refer to at any time to advance offline personal and collaborative learning as well as deepen learning of different concepts related to art-of-living and its components (teaching and learning resources). This may also help in improving comprehension of the concepts that were not properly grasped in the online lecturette sessions. Third, participants may be asked to make a plan—based on a template provided by the facilitator—comprising the steps they would undertake to advance art-of-living in terms of its components. Lastly, pair-based activities tasked as homework may need to be carefully designed to focus more on developing affective competencies requiring participants to present their recommendations, demonstrate a problem-solving attitude, and incorporate the new concepts learned in online sessions into their homework. Pair-based tasks allow each partner to communicate naturally and comfortably as well as offer candid and objective feedback (even through technology), which enhances and sustains learning and sharing (cf. Green, 2021). Further, in group tasks, some members may not participate actively or may not participate at all. As compared to groups of three or more members, pairs may be better able to jointly explore, discuss, and examine how best to master art-of-living as well as address the obstacles to mastering it.

Limitations and Future Research

Findings of this study should be considered bearing in mind its limitations. First, six different measures were administered to study participants. As such, self-report response bias may have been introduced because of social desirability. Future research may focus on a mixed-method study to provide insights into the strategies or activities undertaken by participants during posttest and follow-up measurement to cultivate positivity or master art-of-living in terms of its five components. Further, at posttest, from an educational psychology perspective, participants may be asked to list the elements that they believe contributed to the effectiveness of the training. The aforementioned may provide rich qualitative data regarding the long-term efficacy of the art-of-living intervention.

Second, this intervention only focused on the development of five components of art-of-living. In the future, this blended learning approach may be implemented to train most of the components of art-of-living including the two meta constructs (i.e., reflection and balance). It is pertinent to mention here that an important limitation of art-of-living is that it misses out on some key positive psychology constructs, which may also be useful for enriching people’s lives and furthering well-being. Gratitude is one such construct—as identified by Lang (2020)—permitting individuals to regularly experience positive emotions essential for cultivating a positive mindset (Wood et al. 2008) and building valuable personal resources pertaining to the body-mind-spirit dimensions of wellness (Green et al., 2020a). Moreover, the power of gratitude can never be underestimated. In a study by Kumar et al. (2022), gratitude decreased mental health problems and furthered positivity among college students at the beginning of the pandemic. Furthermore, a gratitude intervention successfully enhanced mental well-being among university students amid the pandemic (Geier & Morris, 2022). Gratitude is thus an important positive psychology construct, which may be included in the art-of-living model and tested as one of its components. Future studies may also use the brand new art-of-living scale, which has good psychometric properties. It is a 35-item scale and assesses 11 components of art-of-living (Schmitz et al., 2022). In addition, to increase the application of the art-of-living intervention, it may be offered to educators, executives, health care providers, social workers, and hospitality crews. Offering the intervention to students studying at different levels may improve its generalizability.

Third, as explained earlier, positivity is a relevant outcome of the art-of-living intervention because of the continuous negative effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on people’s lives. However, the concept of positivity— embodying the essence of life satisfaction, self-esteem, and optimism—overlaps to some extent with two components of art-of-living used in this study, namely social contacts and self-efficacy. The items, “Others are generally there for me when I need them” and “I generally feel confident in myself,” of the positivity scale reflect a sense of social contacts and self-efficacy respectively. It should be noted that because of the importance of self-efficacy and social contacts for university students amid the pandemic, we selected them as components of art-of-living for this study.

In the future, strengths interventions may also be developed and implemented for furthering art-of-living. As such, it may be important to gain useful insights from existing PPIs (e.g., Bu & Duan 2019; Gander et al., 2013, 2016; Green, 2022a; Mitchell et al., 2009; Proyer et al., 2015) to obtain meaningful results. In addition, future research may analyze the effect of the art-of-living intervention—developed for this study—on such variables as PERMA-oriented well-being, mental well-being, the X-Factor, personal growth initiative, career adaptability, work well-being, positive psychological functioning, positive orientation toward future (Butler & Kern, 2016; Green, 2021; Green et al., 2023; Maggiori et al., 2017; Merino & Privado, 2015; Robitschek, 1998; Tennant et al., 2007; Tokar et al., 2020). Its effect may also be studied on variables associated with the pandemic, such as COVID-19 burnout, uncertainty of COVID-19, and anxiety of COVID-19 (Jian et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2022; Yıldırım & Solmaz, 2022). Further, it may be interesting to examine the effect of the art-of-living intervention on such new variables as the new normal way of life and post-pandemic growth. To this end, the scales for assessing these new variables may need to be constructed and validated.

Conclusion

Growth curve analysis showed the long-term utility of an art-of-living intervention developed for bachelor’s and master’s students in Pakistan. Results indicated that positivity, self-efficacy, savoring, social contacts, physical care, meaning, and overall art-of-living increased at a greater rate in the experimental group than in the control group over each time interval. Furthermore, growth curve analysis provided an all-encompassing view of how positivity developed in the two groups over time based on students’ growth parameters (intercepts and slopes). Most importantly, the covariance between the intercepts and slopes suggested that university students with high initial positivity scores had a slower linear increase, whereas those with low initial positivity scores had a faster increase in linear growth over time. The long-term success of the intervention may be attributed to the four dimensions of ELE embodied in the two learning modes permitting participants to gain valuable insights into leading a productive, mindful, and fulfilling life based on the components of art-of-living to experience positivity. Moreover, fidelity to intervention in all probability ensured the effective implementation of blended learning aimed at advancing the efficacy of teaching and learning during COVID-19.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the study participants and the university management for bringing the study to fruition. Special thanks to Rahmatullah Jalal Farooq Ahmed, Seemab Munnawar, Saqib Maqbool, Huma Malik, and Mansoor Khan for their help and support during the study.

Annexure 1

Experiential Activities and Associated Content

| Activity | Description | Associated Content |

|---|---|---|

| INDIVIDUAL LEARNING ACTIVITIES | ||

|

Question assigned as homework (One-pager assignments) Offline learning |

• Participants looked up topics on the Internet (web resources) and typed their views (in not more than 4 points) about them. • They recommended strategies for mastering a component of art-of-living. • They read and watched inspirational material to share lessons learned from it regarding art-of-living. |

• Sources of self-efficacy information, savoring experiences, being a social facilitator, staying interesting and relevant. • Positive attitude, savoring, self-efficacy, social contacts, and meaning. • Acts of kindness, optimism, gratitude, and finding meaning in life. |

|

In 60 s (Reflections activity) Online learning |

Participants presented three pertinent lessons learned from the previous module in not more than 60 s. | Lessons learned pertaining to the 8 modules. |

|

Make it personal Offline learning |

Participants shared personal experiences pertaining to a topic. | Securing positive relationships and taking care of oneself. |

|

Reflective writing Offline learning |

Participants to identify and adapt 3 strategies for attaining well-being based on different topics. | Invigorating the mind, body, and soul; building one’s mystique; living intensively; experiencing positive emotions; finding meaning in life. |

|

Self-reflection Online learning |

Participants completed worksheets in Word documents by answering short questions based on relating the topics covered in the online class to their personal lives. | Savoring life, building healthy habits, practice developing a positive outlook on life, and meaning in life. |

|

Admirable individuals Offline learning |

Participants typed a paragraph (Word document) about an individual in their field or community they respected highlighting his or her strengths in a particular area. | Positive attitude, building relationships, and good conversationalist. |

|

Food for thought (Reading assignment) Offline learning |