Abstract

Background:

Human factor XIIa (FXIIa) is a plasma serine protease that plays a significant role in several physiological and pathological processes. Animal models have revealed an important contribution of FXIIa to thromboembolic diseases. Remarkably, animals and patients with FXII deficiency appear to have normal hemostasis. Thus, FXIIa inhibition may serve as a promising therapeutic strategy to attain safer and more effective anticoagulation. Very few small molecule inhibitors of FXIIa have been reported. We synthesized and investigated a focused library of triazol-1-yl benzamide derivatives for FXIIa inhibition.

Methods:

We chemically synthesized, characterized, and investigated a focused library of triazol-1-yl benzamide derivatives for FXIIa inhibition. Using a standardized chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay, the derivatives were evaluated for inhibiting human FXIIa. Their selectivity over other clotting factors was also evaluated using the corresponding substrate hydrolysis assays. The best inhibitor affinity to FXIIa was also determined using fluorescence spectroscopy. Effects on the clotting times (prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT)) of human plasma were also studied.

Results:

We identified a specific derivative (1) as the most potent inhibitor in this series. The inhibitor exhibited nanomolar binding affinity to FXIIa. It also exhibited significant selectivity against several serine proteases. It also selectively doubled the activated partial thromboplastin time of human plasma.

Conclusion:

Overall, this work puts forward inhibitor 1 as a potent and selective inhibitor of FXIIa for further development as an anticoagulant.

Keywords: FXIIa, anticoagulation, triazol-1-yl benzamides, active site inhibitor, small molecule, thrombosis

1. INTRODUCTION

Factor XIIa (FXIIa) is a serine protease that is mainly produced and secreted by the liver into the systemic circulation as a zymogen, i.e., factor XII (FXII) [1, 2]. It has also been reported that two additional isoforms of FXII are biosynthesized by neurons [3] and leukocytes [4]. Activation of zymogen to the active enzyme typically occurs on a negatively charged surface by cleaving the peptide bond of Arg353-Val354. The resulting form of FXIIa is the α-form which is composed of a light chain consisting of the catalytic domain with the catalytic triad (His393, Asp442, and Ser544) and a heavy chain carrying several binding domains needed for binding to factor XI (FXI), fibrin, heparin, and cells [5-7]. The α-form of FXIIa can further be cleaved by plasma kallikrein at the peptide bonds of Arg343-Leu344 and Arg334-Asn335 to give β-FXIIa, which serves some but not all physiological function of the former form [5, 8]. Physiologically, the activity of FXIIa is regulated by several endogenous proteins, including C1-esterase inhibitor, antithrombin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, α1-antitrypsin, α2-macroglobulin, and α2-antiplasmin [5, 8, 9].

FXIIa plays several physiological roles, and hence, it contributes to several pathological conditions. In short, FXII(a) can be involved in blood coagulation via the intrinsic pathway, inflammation and fibrin degradation via the kallikrein-kinin and fibrinolytic systems, and innate immunity via the complement system. It may also have direct cellular effects that impact cell proliferation and movement and modulate inflammatory responses [10]. Therefore, FXII(a)-targeting agents are proposed to be beneficial in preventing, treating, or managing hereditary inflammatory diseases [11-13], thrombotic diseases [14, 15], sepsis [16], multiple sclerosis [17, 18], Alzheimer’s disease [19-21], and traumatic brain injury [22-24].

Interestingly, humans with inherited deficiency of FXII have been found not to suffer from bleeding, not even during extensive surgery [25, 26]. Not only that, but they also demonstrated prolonged activated partial thromboplastin clotting time (APTT) with no effect on prothrombin time (PT) [27]. Accordingly, FXIIa has become a very attractive drug target for developing new safer anticoagulants. Yet, much of the interest in FXIIa as a potential target for anticoagulation is due to observations in FXII knockout mice because FXII deficiency in humans is rare. These mice were found to be protected against chemically and mechanically induced arterial and venous thromboses in combination with normal bleeding times [27-29]. Like humans, these mice had significantly prolonged APTT clotting time without bleeding tendency [27-29]. FXII null mice were consistently protected from thromboembolic diseases, including ischemic stroke [28] and pulmonary embolism [29]. These observations led to the development of FXII(a)-targeting agents which demonstrated effective anticoagulant activity in an array of arterial and venous thrombosis models in mice, rabbits, and nonhuman primates with no bleeding complications [30-37]. Likewise, several preclinical studies confirmed the benefits of FXII inhibition in murine [38-41] and nonhuman primate [42-44] models of sepsis. Currently, there are two clinical trials ongoing to evaluate agents targeting the physiological functions of FXIIa for prophylactic treatment of hereditary angioedema (NCT03712228, Phase II, IV monoclonal antibody CSL312) and for thromboprophylaxis in end-stage renal dis-ease patients on chronic hemodialysis (NCT-03612856, Phase II, IV monoclonal antibody AB023) [45]. Importantly, although the FXII(a)-targeting agents in the above clinical trials are monoclonal antibodies, there are many other molecular entities under development, including peptides and proteins [10, 46], small molecules [47-49] (Fig. 1), antisense oligonucleotides, small interfering RNAs, and aptamers [10, 46].

Fig. 1.

The chemical structures of reported small molecule active site inhibitors of human FXIIa with the corresponding inhibition parameters against human FXIIa [47-49].

Despite the diversity of FXII(a)-targeting agents from the standpoint of structure, mechanisms, and potential indications, the full potential of FXII(a) as drug target(s) is yet to be achieved. In this paper, we have investigated the potential of triazol-1-yl benzamides as active site small molecule inhibitors of human FXIIa to serve as lead molecules for further development as anticoagulants, and potentially other indications. In our focused library of triazol-1-yl benzamides, inhibitor 1 stood out as the most potent and selective inhibitor of human FXIIa that is synthetically feasible in one chemical step. Inhibitor 1 also demonstrated physiologically relevant inhibitory activity by inhibiting the FXIIa-ediated activation of its macromolecular substrate in the coagulation pathway, i.e., FXI. Inhibitor 1 also exhibited selective anticoagulant activity at a macromolecular range in human plasma. Overall, this work puts forward the small molecule triazol-1-yl benzamide 1 as a potent and selective inhibitor of human FXIIa for further development as safe and effective anticoagulant, and potentially other relevant indications.

2. MATERIALS AND EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

2.1. Chemicals, Reagents, and Analytical Chemistry

Anhydrous organic solvents (hexanes, dichloromethane, and ethyl acetate) were purchased from Fisher (Pittsburgh, PA) and used as they were received. 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethy-laminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDCI) and 4-dimethy-laminopyridine (DMAP) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Analytical TLC was performed using UNIPLATETM silica gel GHLF 250 um precoated plates (ANALTECH, Newark, DE). Column chromatography was conducted using silica gel (200-400 mesh, 60 Å) from Sigma-Aldrich. All reactions were carried out under oven-dried glassware. Flash chromatography was performed using Teledyne ISCO (Lincoln, NE) Combiflash RF system and disposable normal silica cartridges of 30-50 μ particle size, 230-400 mesh size and 60 Å pore size. The mobile phase's flow rate was 18 to 35 ml/min, and mobile phase gradients of ethyl acetate/hexanes were used to elute inhibitors 1-5. Pooled normal human plasma for clotting assays was obtained from Valley Biomedical (Winchester, VA). PT (thromboplastin-D) and APTT containing ellagic acid (APTT-LS) were obtained from Fisher Diagnostics (Middletown, VA).

2.2. Chemical Characterization of Inhibitors (1-5)

1H and 13C NMR were recorded on Bruker-400 MHz spectrometer in CDCl3, acetone-d6, or DMSO-d6. Signals, in parts per million (ppm), are relative to the residual peak of the solvent. The NMR data are reported as chemical shift (ppm), multiplicity of signal (s= singlet, d= doublet, t= triplet, q= quartet, dd= doublet of doublet, m= multiplet), coupling constants (Hz), and integration. In the positive ion mode, ESI-MS profiles of inhibitors 1-5 were obtained using Waters Acquity TQD MS spectrometer. Samples were solubilized in methanol for mass spectrometry analysis. The purity of inhibitor 1 were greater than 95%.

2.3. Proteins, Substrates, and Buffers

Human plasma serine proteases, including thrombin, FXa, FXIa, FIXa, FVIIa/tissue factor, and plasmin were obtained from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT). FXIIa was purchased from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN). Bovine α-chymotrypsin, bovine trypsin, and human plasma kallikrein were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The substrates Spectrozyme TH, Spectrozyme FXa, Spectrozyme FIXa, and Spectrozyme PL. Spectrozyme VIIa, Spectrozyme FXIIa, and Spectrozyme PK were obtained from Biomedica Diagnostics (Windsor, NS Canada). Factor XIa substrate (S-2366) and trypsin substrate (S-2222) were obtained from Diapharma (West Chester, OH). N-succinyl Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-p-nitroanilide substrate for chymotrypsin is from Sigma-Aldrich. All enzymes and substrates were prepared in 20-50 mM TrisHCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 100-150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 0.1% PEG8000, and 0.02% Tween80. In the case of FIXa, 33% v/v ethyleneglycol was also added to the buffer.

2.4. Synthesis of Methyl 5-amino-1-(4-(tert-butyl)benzoyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxylate (1)

To a stirred solution of 4-(tert-butyl)benzoic acid (1.0 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was added DMAP (1.1 mmol) and EDCI (1.1 mmol) at RT under dry conditions. Methyl 5-amino-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxylate (1.1 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was then added. After stirring overnight, the reaction mixture was partitioned between saturated NaHCO3 solution (20 mL) and CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The organic layer was washed further with saturated NaHCO3 solution (2 × 10 mL) and saturated NaCl solution (20 mL), dried using anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated by the rotary evaporator to give a crude, which was purified by flash chromatography using a gradient of ethylacetate/hexanes mixture as eluant to produce inhibitor 1 in more than 90% yield.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 7.59 (d, 2H, J = 8.44 Hz), 7.46 (d, 2H, J = 8.44 Hz), 3.90 (s, 3H), 1.29 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 168.31, 160.02, 158.99, 158.05, 151.85, 131.63, 127.72, 125.55, 53.00, 35.31, 31.02. Calculated MS [M+Na]+= 325.13. Found MS [M+Na]+= 325.0712.

2.5. Synthesis of Methyl 5-amino-1-benzoyl-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxylate (2)

To a stirred solution of benzoic acid (1.0 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was added DMAP (1.1 mmol) and EDCI (1.1 mmol) at RT under dry conditions. Methyl 5-amino-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxylate (1.1 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was then added. After stirring overnight, the reaction mixture was partitioned between saturated NaHCO3 solution (20 mL) and CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The organic layer was washed further with saturated NaHCO3 solution (2 × 10 mL) and saturated NaCl solution (20 mL), dried using anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated by the rotary evaporator to give a crude, which was purified by flash chromatography using a gradient of ethylacetate/hexanes mixture as eluant to produce inhibitor 2 in more than 90% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): 7.98 (d, 2H, J = 7.4 Hz), 7.69-7.67 (m, 1H), 7.57-7.54 (m, 2H), 3.81 (s, 3 H).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): 168.08,160.02, 158.63, 152.31, 133.33, 131.27, 130.50, 128.17, 52.47. Calculated MS [M+Na]+= 269.07. Found MS [M+Na]+= 269.0459.

2.6. Synthesis of (5-amino-1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)(4-(tert-butyl) phenyl)methanone (3)

To a stirred solution of benzoic acid (1.0 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was added DMAP (1.1 mmol) and EDCI (1.1 mmol) at RT under dry conditions. Afterward, 1H-1,2,4-triazol-3-amine (1.1 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was added. After stirring overnight, the reaction mixture was partitioned between saturated NaHCO3 solution (20 mL) and CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The organic layer was washed further with saturated NaHCO3 solution (2 × 10 mL) and saturated NaCl solution (20 mL), dried using anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated by the rotary evaporator to give a crude, which was purified by flash chromatography using a gradient of ethylacetate/hexanes mixture as eluant to produce inhibitor 3 in more than 90% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): 8.02 (d, 2H, J= 8.48 Hz), 7.67 (s, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, 2H, J = 8.48 Hz), 1.33 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): 167.59, 158.32, 156.13, 151.24, 130.72, 129.12, 124.85, 34.84, 30.76. Calculated MS [M+Na]+= 267.12. Found MS [M+Na]+= 267.0934.

2.7. Synthesis of 5-amino-1-(4-(tert-butyl)benzoyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxylic acid (4)

To a stirred solution of inhibitor 1 in (1:1) (CH3OH:H2O) (10 mL) was added LiOH.H2O (1.2 mmol) at RT. After stirring for 5 hr, the reaction mixture was partitioned between 3 mM HCl solution (10 mL) and CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The organic extraction was repeated multiple times; the organic extract was then dried using anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated by the rotary evaporator to give a crude, which was purified by flash chromatography using a gradient of ethylacetate/hexanes mixture as eluant to produce inhibitor 4 in more than 90% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6): 7.84 (d, 2H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.42 (d, 2H, J = 8.56 Hz), 1.21 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, acetone-d6): 167.41,159.70, 157.80, 156.97, 150.70, 130.23, 128.72, 126.10, 35.30, 31.24. Calculated MS [M+Na]+= 311.11. Found MS [M+Na]+= 311.0253.

2.8. Synthesis of 5-amino-1-(4-(tert-butyl)benzoyl)-N-methyl-1-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide (5)

To a stirred solution of inhibitor 4 (1.0 mmole) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was added DMAP (1.1 mmol) and EDCI (1.1 mmol) at RT under dry conditions. Methyl amine (1.1 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was then added. After stirring overnight, the reaction mixture was partitioned between saturated NaHCO3 solution (20 mL) and CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The organic layer was washed further with saturated NaHCO3 solution (2 × 10 mL) and saturated NaCl solution (20 mL), dried using anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated by the rotary evaporator to give a crude, which was purified by flash chromatography using a gradient of ethylacetate/hexanes mixture as eluant to produce inhibitor 5 in more than 90% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 7.62 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.36 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 2.94 (s, 3H), 1.26 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 165.72, 162.31, 158.19, 157.55, 154.85, 131.63, 126.65, 125.47, 34.89, 31.15, 26.77. Calculated MS [M+Na]+=324.14. Found MS [M+Na]+= 324.0949.

2.9. Inhibition of Human FXIIa by Inhibitors (1-5)

Direct inhibition of human FXIIa was evaluated by a chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay using a microplate reader under physiologic conditions of 37 °C and pH 7.4, as reported in our previous reports [50-54]. In this platform, each well of the 96-well microplate had 175 μL of pH 7.4 TrisHCl buffer to which 5 μL of inhibitors 1-5 (or vehicle) and 5 μL of human FXIIa (stock conc. 200 nM) were sequentially added. Following a 5-min incubation, 5 μL of FXIIa substrate (stock 5 mM) was rapidly added and the residual FXIIa activity was measured from the initial rate of increase in absorbance at a wavelength of 405 nm. Stocks of potential FXIIa inhibitors were serially diluted (1/20 dilution factor) to give twelve different concentrations in the wells (500-0.0025 μM). Relative residual FXIIa activity at each concentration of the inhibitor was calculated from the ratio of FXIIa activity in the absence and presence of the inhibitor. Logistic equation 1 was used to fit the dose- dependence of residual FXIa activity to obtain the potency () as well as the efficacy () of inhibition.

| (1) |

In the above equation, is the ratio of residual FXIa activity in the presence of inhibitor 1 to that in its absence, and are the minimum and maximum possible values of the fractional residual proteinase activity, is the concentration of the inhibitor that results in 50% inhibition of enzyme activity, and HS is the Hill slope. Nonlinear curve fitting resulted in , , , and values.

2.10. Inhibition of Other Serine Proteases by Inhibitor 1

The inhibition profile of inhibitor 1 against related serine proteases, including thrombin, FVIIa/tissue factor, FIXa, FXa, FXIa, plasma kallikrein, bovine trypsin, bovine α-chymotrypsin, and plasmin was evaluated using the corresponding chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assays as documented in our previous studies [50-54]. These assays were performed using substrates and conditions appropriate for the studied enzyme. For selectivity analysis, several concentrations of inhibitor 1 were exploited and the residual enzyme activity was measured at each concentration. If the enzyme was inhibited concentration-dependently by inhibitor 1, the concentration vs the relative residual enzyme activity (%) profile was constructed using logistic equation 1 to determine the corresponding and efficacy of the enzyme–inhibitor complex. The KM of the chromogenic substrate for its enzyme was used to determine the concentration of the chromogenic substrate to be used for inhibition studies. The concentrations of enzymes and substrates in microplate cells were about 6 nM and 50 μM for thrombin, 8 nM and 1000 μM for FVIIa, 89 nM and 850 μM for FIXa, 1.09 nM and 125 μM for FXa, 3 nM and 100 μM for human plasma kallikrein, 500 ng/mL and 650 μM for bovine trypsin, 500 ng/mL and 910 μM for bovine chymotrypsin and 20 nM and 50 μM for human plasmin.

2.11. Determination of the Constant of Inhibitor 1 to Human FXIIa

The equilibrium binding constant () of inhibitor 1 to human FXIIa was determined by fluorescence spectroscopy. Fluorescence experiments were performed using a QM4 fluorometer (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ) in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer of pH 7.4 containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% PEG8000 and a temperature of 37°C. The for the interaction of inhibitor 1 with human FXIIa was determined by titrating inhibitor 1 (100 μM) into a solution of FXIIa (350 nM) and monitoring the increase in the intrinsic fluorescence of FXIIa at 348 nm (λEX = 280 nm). The slit widths on the excitation and emission sides were 1 mm. The increase in fluorescence signal was fitted using the quadratic equilibrium binding equation 2 to obtain the of interaction. In this equation, represents the change in fluorescence following each addition of inhibitor 1 from the initial fluorescence and represents the maximal change in fluorescence observed with saturation of FXIIa.

| (2) |

2.12. Inhibition of the Physiological Function of Human FXIIa, i.e., Activation of FXI to FXIa by Inhibitors 1

Inhibition of the activation of zymogen FXI to the corresponding enzyme FXIa via inhibiting the protein activator FXIIa by small molecule 1 was evaluated by a chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay using a microplate reader under physiologic conditions of 37 °C and pH 7.4. In this platform, each well of the 96-well microplate had 80 μL of pH 7.4 Tris-HCl buffer to which 5 μL of zymogen FXI (4 μM), 5 μL of human FXIIa (200 nM), 5 μL of inhibitor 1 (1000 - 0.32 μM) were sequentially added. Following a 5-min incubation, 5 μL of FXIa substrate (S-2366, stock 6.9 mM) was rapidly added and the residual FXIa activity was measured from the initial rate of increase in absorbance at a wavelength of 405 nm. Relative residual FXIa activity at each concentration of the inhibitor was calculated from the ratio of FXIIa activity in the absence and presence of the inhibitor. Logistic equation 1 was used to fit the dose- dependence of residual FXIa activity to obtain the potency () as well as the efficacy () of inhibition.

2.13. Clotting Times in Human Plasma. Measuring Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT) and Prothrombin Time (PT)

Plasma clotting assays of APTT and PT are routinely used to investigate the anticoagulation potential of new coagulation enzyme inhibitors under in vitro conditions. APTT studies the effect of an enzyme inhibitor on intrinsic/contact pathway-driven clotting which involves FXIIa, FXIa, and FIXa. PT studies the effect of an enzyme inhibitor on the extrinsic pathway of coagulation which involves FVIIa. The clotting time assays (APTT and PT) were performed using the BBL Fibrosystem fibrometer (Becton–Dickinson, Sparles, MD), as reported in our earlier studies [50-54]. For the APTT assay, 10 μL of inhibitor 1 (concentrations: 0, 65, 130, 200, 400, 465, 533, 600, 665, and 983 μM) was mixed with 90 μL of citrated human plasma and 100 μL of prewarmed APTT reagent (0.2% ellagic acid). After incubation for 4 min at 37°C, clotting was initiated by adding 100 μL of prewarmed 25 mM CaCl2, and the time to clotting was noted. For the PT assay, thromboplastin-D was prepared according to the manufacturer’s directions by adding 4 mL of distilled water, and then the resulting mixture was warmed to 37°C. A 10 μL of inhibitor 1 (same concentration above) was then mixed with 90 μL of citrated human plasma and was subsequently incubated for 30 sec at 37 °C. Following the addition of 200 μL of prewarmed thromboplastin-D preparation, the time to clotting was recorded. The positive controls used in APTT and PT assays were (1) argatroban, a clinically used thrombin inhibitor; (2) rivaroxaban, a clinically used FXa inhibitor, (3) UFH, a clinically used antithrombin activator; and (3) C6B7, an experimental FXIIa inhibitor, as reported in previous reports [50]. The negative controls (using the vehicle) for APTT and PT were measured and found to be 34.9 and 14.9 s, respectively.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Identification of the Inhibitors and their Chemical Synthesis

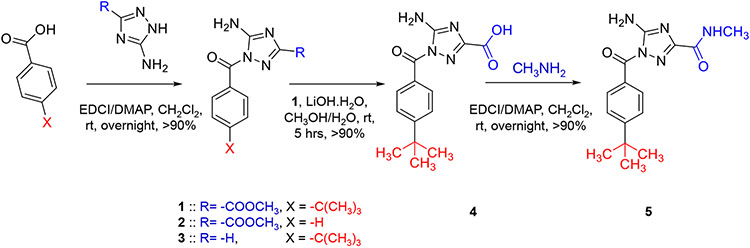

A survey of online databases of PubChem compounds and MEROPS peptidases led to the identification of multiple small molecules as potential inhibitors for FXIIa [2]. Considering its synthetic feasibility, we have chosen molecule 1 for detailed in vitro studies. Inhibitor 1 was quantitatively synthesized in one step from 4-(tert-butyl)benzoic acid and methyl 5-amino-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxylate in the presence of DMAP and EDCI, under anhydrous conditions (Fig. 2). Inhibitor 2 was quantitively synthesized by using benzoic acid instead of 4-(tert-butyl)benzoic acid, whereas inhibitor 3 was quantitively synthesized by using 1H-1,2,4-triazol-3-amine instead of methyl 5-amino-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxylate. Inhibitor 4 was synthesized from inhibitor 1 by hydrolyzing the inhibitor by hydrolyzing its methyl ester by LiOH.H2O. Under anhydrous conditions, treating inhibitor 4 with methylamine in the presence of DMAP and EDCI led to the formation of inhibitor 5. All five inhibitors were quantitatively isolated and appropriately characterized by 1H as well as 13C NMR and high-resolution mass spectroscopy, which also suggested high purity. In particular, the purity of inhibitor 1 was >95%.

Fig. 2.

The chemical synthesis of the five inhibitors (1-5) reported in this study along with the corresponding chemical reagents and conditions of each step and its approximate chemical yield.

3.2. Inhibition of Human FXIIa by Inhibitors 1-5

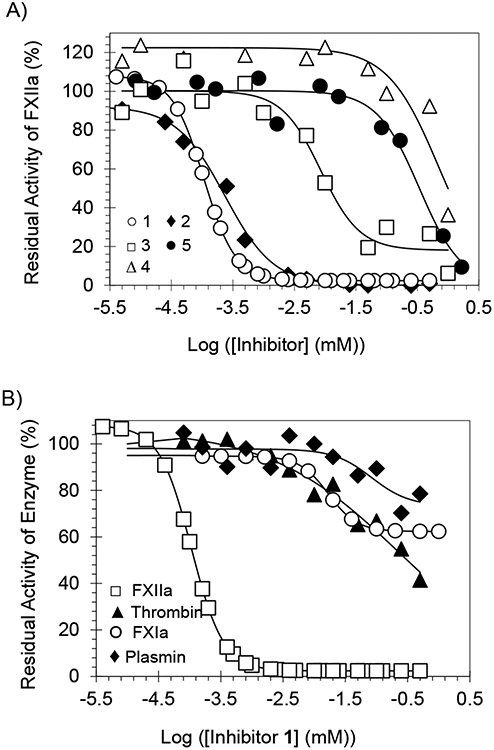

Direct inhibition of FXIIa was measured by a chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay under physiological conditions of pH 7.4 TrisHCl buffer at 37 °C, as reported earlier [50-54]. In this assay, hydrolysis of the substrate by FXIIa results in a linear increase in absorbance at 405 nm. The slope of the resulting line corresponds to the residual enzyme activity and the change in residual enzyme activity as a function of the concentration of the inhibitor is plotted and fitted by the logistic equation 1 to derive the potency (), efficacy () and Hill Slope (HS) of inhibition [50-54]. (Fig. 3A) shows the inhibition profiles for all five inhibitors. The values of these inhibitors widely ranged from 0.11 μM (inhibitor 1) to 699 μM (inhibitor 4) (Table 1), which provides some insights into the structure - activity relationship (SAR). The efficacy of all inhibitors was >82%.

Fig. 3.

(A) Direct inhibition of human FXIIa by inhibitors 1-5. The inhibition profiles of 1 (○), 2 (♦), 3 (□), 4 (), and 5 (●) were studied using the corresponding chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay. (B) Direct inhibition of several serine proteases by inhibitor 1. The inhibition of FXIIa (□), Thrombin (▲), FXIa (○), and plasmin (♦) by 1 was studied using the corresponding chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay. In the two figures, solid lines represent sigmoidal dose-response fits (equation 1) of the data to obtain the values of , , and .

Table 1.

The inhibition parameters of triazol-3-yl benzamide analogs (1-5) toward human FXIIa.a

| Inhibitor | (μM) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.11 ± 0.01b | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 105 ± 8 |

| 2 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 1.09 ± 0.14 | 92.2 ± 3.1 |

| 3 | 8.53 ± 1.19 | 1.37 ± 0.69 | 82.1 ± 8.1 |

| 4 | 699.4 ± 142.5 | 1.05 ± 0.55 | 122.4 ± 23.4 |

| 5 | 339.9 ± 30.5 | 1.26 ± 0.27 | 103 ± 5 |

Note:

The , , and values were obtained following nonlinear regression analysis of direct inhibition of human FXIIa in appropriate Tris–HCl buffers of pH 7.4 at 37 °C. Inhibition was monitored spectro-photometrically.

Errors represent ± 1 S.E.

Several important SAR aspects can be inferred. The inhibitors varied at two specific sites: (1) the para-substituent of the benzamide moiety at position-1 of the triazole ring and (2) the nature of position-3 substituent on the triazole ring. The most potent inhibitor in this series was inhibitor 1, which has a t-butyl group at the para-position of the benzamide moiety and a methylcarboxylate moiety at position-3 of the triazole ring. Replacing the t-butyl group with a hydrogen as in inhibitor 2 resulted in a ~2.2-fold decrease in the inhibition potency. Nevertheless, replacing the methylcarboxylate moiety with hydrogen led to a more detrimental effect as the potency decreased by 77.5-fold as in inhibitor (3). Interestingly, replacing the methylcarboxylate moiety with a carboxylate group or N-methylamido group resulted in a significant loss in inhibition potency as indicated by the high micromolar values of inhibitors 4 and 5. One possible explanation for the such dramatic loss of potency is that position-3 groups in these inhibitors are relatively electron-rich and in fact, are acidic in nature. This suggests that position-3 moieties may bind to a pocket/subsite in the active site of FXIIa, which contains an acidic amino acid (glutamate or aspartate), leading to repulsive forces and resulting in decreased inhibition potency. That pocket is likely to be the S1 subsite which contains Asp189 [49].

3.3. Selectivity of Inhibitor 1 Against Other Serine Proteases

Inhibitor 1 was studied for its potential to inhibit serine proteases under physiological or near physiological conditions using the corresponding chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assays, as reported earlier [50-54]. The serine proteases that were included in the selectivity studies are listed in Table 2 and representative profiles are depicted in Fig. (3B). The selectivity evaluation included: (1) thrombin, FXa, FXIa, FIXa, FVIIa/TF, and plasma kallikrein, serine proteases of the coagulation system; (2) bovine trypsin and α-chymotrypsin, serine protease of the digestive system; and (3) plasmin, a serine protease of the fibrinolytic system. Inhibitor 1 was found to be selective to human FXIIa over thrombin, FXIa, and plasmin with selectivity indices of 2137-fold, 153-fold, and 756-fold, respectively. The inhibitor was also found to be at least 4545-fold selective to FXIIa over FXa, FIXa, FVIIa/TF, plasma kallikrein, trypsin, and α-chymotrypsin. Overall, inhibitor 1 demonstrates high selectivity against other related serine proteases, and thus, it represents an excellent lead molecule to be further developed as a relatively safer anticoagulant, given that FXII(a)-targeting agents are associated with a low risk of bleeding [25-29].

Table 2.

Inhibition potency of triazol-3-yl benzamide 1 for other human serine proteases.a

| Enzyme | (μM) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FXIIa | 0.11 ± 0.01b | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 105 ± 8 |

| Thrombin | 235.1 ± 52.5 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 106 ± 7 |

| FXa | >577 | ND | ND |

| FXIa | 16.8 ± 6.7 | 1.9 ± 2.8 | 32 ± 11 |

| Plasmin | 83.2 ± 37.0 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 25 ± 12 |

| FIXa | >1000 | ND c | ND |

| FVIIa/TF | >1000 | ND | ND |

| P. Kallikrein | >500 | ND | ND |

| Trypsin | >1000 | ND | ND |

| Chymotrypsin | >1000 | ND | ND |

Note:

The , , and values were obtained following non-linear regression analysis of direct inhibition of human FXIIa in appropriate Tris–HCl buffers of pH 7.4 at 37 °C. Inhibition was monitored spectrophotometrically.

Errors represent ± 1 S.E.

Not determined.

3.4. The Thermodynamic Affinity of Inhibitor 1 to Human FXIIa

Although the of inhibitor 1 toward FXIIa was spectrophotometrically measured using a chromogenic substrate, its thermodynamic affinity, i.e., the equilibrium dissociation constant () is indeterminate. As their potential molecular targets, the affinity of inhibitors to serine proteases has been measured using either intrinsic or extrinsic fluorescence probes [54, 55]. The inhibitor may increase or decrease the fluorescence intensity of a fluorophore and may or may not cause a red or blue shift in λEM. For example, we previously measured the affinity of chromen-7-yl furan-2-carboxylate to human FXIa using the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (λEX = 280 nm, λEM = 348 nm) [54, 55]. Thus, we used the change in the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of human FXIIa to probe the interaction of inhibitor 1 with FXIIa and measure its . A saturating decrease of −29.6 ± 2.0% in the intrinsic fluorescence of FXIIa was measured for inhibitor 1 at pH 7.4 and 37 °C, which could be fitted using the standard quadratic binding equation 2 to calculate a value of 0.98 ± 0.13 μM (Fig. 4A). No substantial shift in λEM was noted. Overall, FXIIa inhibition by molecule 1 appears to be because of the direct interaction between the two entities, i.e., the macromolecule and the small molecule.

Fig. 4.

(A) Spectrofluorometric measurement of the affinity of human FXIIa for inhibitor 1 (○) at pH .4 and 37°C using the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (λEM = 348 nm, λEX = 280 nm). Solid lines represent the nonlinear regressional fits using quadratic equation 2 to derive and . (B) The effect of inhibitor 1 on the physiological function of FXIIa i.e., activation of FXI to the FXIa. The inhibition was studied using the corresponding chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assay as described in the experimental part. Solid lines represent sigmoidal dose-response fits (equation 1) of the data to obtain the values of , , and .

3.5. The Effect of Inhibitor 1 on the Physiological Function of FXIIa, i.e., Activation of the Zymogen FXI to the Corresponding Enzyme FXIa

Although inhibitor 1 inhibits FXIIa hydrolysis of the tripeptide chromogenic substrate, FXI is a more relevant substrate of FXIIa. During coagulation, FXIIa activates FXI through cleavage at the Arg369-Ile370 bond to generate FXIa [56, 57], which eventually amplifies thrombin production. To establish the translation aspect of molecule 1 inhibition of tripeptidyl substrate hydrolysis on physiological macromolecules, we measured, using S-2366, the residual activity of FXIa that was formed by activating FXI by FXIIa. Fig. (4B) shows the residual activity of FXIa formed by FXIIa-mediated activation of FXI in the presence of various concentrations of FXIIa inhibitor 1. As indicated by the profile, there was a decrease in the residual activity of FXIa, which most likely owes to its reduced generation from its zymogen because of the inhibition of the activating protein i.e., FXIIa. A similar setup was exploited before to demonstrate FXIIa-mediated activation of FXI [56, 57]. The and the efficacy of FXIIa inhibition by molecule 1 measured in this assay using the macromolecule substrate of FXIIa, i.e., FXI were ~2 μM and ~41%, respectively. Although we did not investigate the reason for such a decrease in the two inhibition parameters, the macromolecular substrate may sterically hinder inhibitor 1 from accessing the active site of FXIIa. Regardless, the inhibition activity of molecule 1 toward FXIIa appears to be physiologically relevant.

3.6. The Anticoagulant Activity of Inhibitor 1 in Human Plasma

Human plasma clotting assays are commonly used to assess the anticoagulant potential of new enzyme inhibitors in an in vitro setting. While the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) studies the effect of an inhibitor on the intrinsic coagulation pathway, the prothrombin time (PT) studies the effect on the extrinsic pathway of coagulation. The effects of inhibitor 1 on APTT and PT were conducted as reported previously. The inhibitor prolonged APTT concentration-dependently, whereas it lacked any significant effect on PT as depicted in Fig. (5). As reported earlier, the concentrations of inhibitor 1 required to increase APTT and PT by 1.5-fold were measured [50-54]. A 1.5-fold increase in APTT required ~340 μM of inhibitor 1. However, the PT was not significantly affected at the highest concentration tested, which was about 980 μM. These results indicate that inhibitor 1 has good anticoagulant activity in human plasma and that it exerts such activity primarily by selectively inhibiting enzymes in the intrinsic coagulation pathway, which includes FXIIa, in addition to FIXa and FXIa. To further support the selectivity of inhibitor 1, we compared its effects on APTT and PT with those of argatroban HCl, rivaroxaban, UFH, and C6B7. The first three affected both APTT and PT because they are either direct or indirect thrombin and/or FXa inhibitors, whereas C6B7 antibody inhibitor of human FXIIa only affected APTT [50] (Table (3). The profile of inhibitor 1 in human plasma is largely consistent with that of C6B7. Thus, these results establish the selectivity profile of inhibitor 1, which was evaluated above using the corresponding in vitro chromogenic substrate hydrolysis assays.

Fig. 5.

The anticoagulant activity of inhibitor 1 in human plasma. The time to clot was measured in the APTT assay (■) and the PT assay (■) in the presence of varying concentrations of inhibitor 1 The means of three experiments are reported along with the corresponding standard errors.

Table 3.

Effects of clinical and experimental anticoagulants on APTT and PT in normal human plasmas.

| Anticoagulant | APTT (EC×1.5)a | PT(EC×1.5)a |

|---|---|---|

| Argatroban HCl (Direct thrombin inhibitor) | ~0.19 μMb | ~0.13 μM |

| Rivaroxaban (Direct FXa inhibitor) | ~0.06 μM | ~0.08 μM |

| UFH (Indirect thrombin and FXa inhibitor) | ~0.47 μg/mL | ~2 μg/mL |

| C6B7 (Direct FXIIa inhibitor) | ~0.06 μg/mL | NE c |

| Inhibitor 1 | ~340 μM | NE |

Note:

The effective concentration to double the clotting time in the corresponding assay

Standard erros are less than 10% based on multiple measurements

NE No effect at the highest concentration tested. Abbreviations: EC: Effective concentration; APTT: Activated partial thromboplastin time; PT: Prothrombin time; AT: Antithrombin.

4. DISCUSSION

In our continuous efforts to develop clinically relevant anticoagulants that inhibit the intrinsic coagulation pathway, we discovered methyl 5-amino-1-(4-(tert-butyl)-benzoyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxylate 1 as a potent, selective, and physiologically relevant inhibitor of FXIIa. The presented scaffold is unique among previously reported small molecule inhibitors of human FXIIa (Fig. 1). Inhibitor 1 demonstrated a nanomolar inhibition potential toward human FXIIa ( nM). Not only that, but inhibitor 1 also exhibited a very promising selectivity profile over a host of related serine proteases, which typically share significant active site homology. In fact, inhibitor 1 was found to be selective to human FXIIa over thrombin, FXIa, and plasmin, with selectivity indices of 2137-fold, 153-fold, and 756-fold, respectively. The inhibitor was also found to be at least 4545-fold selective to FXIIa over FXa, FIXa, FVIIa/TF, plasma kallikrein, trypsin, and α-chymotrypsin. In contrast to the clinically available anticoagulants, inhibitor 1 apparently acted as an anticoagulant in human plasma by interfering with the intrinsic coagulation pathway as indicated by the APTT assay. This, in fact, is very encouraging and projects a limited potential bleeding risk to be associated with such a scaffold. This remains to be tested in tail bleeding assays.

Importantly, FXIIa appears to be a via ble drug target for multiple indications. In this report, we investigated triazol-1-yl benzamides as active site inhibitors of human FXIIa for identifying a lead molecule for further development as effective anticoagulants that are devoid of bleeding complications. Thrombotic disorders are major public health crises and continue to create enormous social and financial burdens. Anticoagulants are prescribed to prevent and/or treat thrombotic disorders. Nevertheless, current clinically used anticoagulants, which target thrombin and/or FXa, are plagued with several drawbacks, especially the high risk of bleeding [58-61]. FXIIa, an upstream serine protease of the intrinsic pathway, is a promising target for developing effective and safer anticoagulants [25-37].

The introduction of FXIIa small molecule inhibitors is expected to address multiple unmet medical needs for which current therapies are limited in efficacy and safety. FXIIa-based anticoagulants may benefit patients with chronic kidney disease who are considered as a high-risk group for thrombosis and have platelet abnormalities which put them at higher risk of bleeding [62-65]. Another special group of patients is those with atrial fibrillation. Because of the fear of bleeding, more than 30% of these patients fail to receive any anticoagulant prophylaxis, and among those given anticoagulation therapy, up to 50% are ineffectively treated [62-65]. Other patients who may also benefit from FXIIa-based anticoagulants are (1) patients with venous thromboembolism who are at an elevated risk of recurrent thrombosis upon discontinuation of anticoagulant therapy; (2) hemodialysis patients and patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; (3) patients with cardiac devices; and (4) acute coronary syndrome patients who need anticoagulant therapy in addition to antiplatelet therapy [66].

CONCLUSION

In this paper, inhibitor 1 was quantitatively synthesized in a single chemical reaction which allowed us to perform a concise SAR study that highlighted the significance of the two positions: position-3 on the triazole moiety and position-4 on the benzamide moiety for its FXIIa inhibitory activity. Modifications at these two sites and replacement of the triazole moiety with other 5- and 6-membered heteroaromatic moieties will be considered in efforts to optimize inhibitor 1.

In vitro and in vivo work to advance the anticoagulant potential of inhibitor 1 are ongoing and will be reported in due time. Overall, inhibitor 1 is expected to serve as an excellent lead to guide subsequent efforts to develop paradigm-shifting anticoagulants that treat and/or prevent thrombosis, yet with a none-to-limited risk of internal bleeding. It can also be considered as a potential lead to develop FXIIa-inhibiting agents as primary or adjunctive therapies to treat inflammation, sepsis among other pathological conditions.

FUNDING

The research reported was supported by NIGMS of the National Institute of Health under award number SC3-GM131986 to R.A.A.H. Furthermore, M.M. is supported by NIMHD of the National Institute of Health under the award number U54MD007595. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding institutions.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- APTT

Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time

- PT

Prothrombin Time

Footnotes

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article are available within the article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

DISCLAIMER: The above article has been published, as is, ahead-of-print, to provide early visibility but is not the final version. Major publication processes like copyediting, proofing, typesetting and further review are still to be done and may lead to changes in the final published version, if it is eventually published. All legal disclaimers that apply to the final published article also apply to this ahead-of-print version.

REFERENCES

- [1].Schmaier AH; Stavrou EX Factor XII - What’s important but not commonly thought about. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost, 2019, 3(4), 599–606. 10.1002/rth2.12235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rawlings ND; Barrett AJ; Thomas PD; Huang X; Bateman A; Finn RD The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Res., 2018, 46(D1), D624–D632. 10.1093/nar/gkx1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zamolodchikov D; Bai Y; Tang Y; McWhirter JR; Macdonald LE; Alessandri-Haber N A short isoform of coagulation factor XII mRNA is expressed by neurons in the human brain. Neuroscience, 2019, 413, 294–307. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stavrou EX; Fang C; Bane KL; Long AT; Naudin C; Kucukal E; Gandhi A; Brett-Morris A; Mumaw MM; Izadmehr S; Merkulova A; Reynolds CC; Alhalabi O; Nayak L; Yu WM; Qu CK; Meyerson HJ; Dubyak GR; Gurkan UA; Nieman MT; Sen Gupta A; Renné T; Schmaier AH Factor XII and uPAR upregulate neutrophil functions to influence wound healing. J. Clin. Invest, 2018, 128(3), 944–959. 10.1172/JCI92880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Didiasova M; Wujak L; Schaefer L; Wygrecka M Factor XII in coagulation, inflammation and beyond. Cell. Signal, 2018, 51, 257–265. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Stavrou E; Schmaier AH Factor XII: What does it contribute to our understanding of the physiology and pathophysiology of hemostasis & thrombosis. Thromb. Res, 2010, 125(3), 210–215. 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].de Maat S; Maas C Factor XII: Form determines function. J. Thromb. Haemost, 2016, 14(8), 1498–1506. 10.1111/jth.13383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Weidmann H; Heikaus L; Long AT; Naudin C; Schlüter H; Renné T The plasma contact system, a protease cascade at the nexus of inflammation, coagulation and immunity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res, 2017, 1864(11), 2118–2127. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Salvesen GS; Catanese JJ; Kress LF; Travis J Primary structure of the reactive site of human C1-inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem, 1985, 260(4), 2432–2436. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)89572-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Davoine C; Bouckaert C; Fillet M; Pochet L Factor XII/XIIa inhibitors: Their discovery, development, and potential indications. Eur. J. Med. Chem, 2020, 208, 112753. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Farkas H Hereditary angioedema: Examining the landscape of therapies and preclinical therapeutic targets. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets, 2019, 23(6), 457–459. 10.1080/14728222.2019.1608949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Philippou H Heavy chain of FXII: Not an innocent bystander. Blood, 2019, 133(10), 1008–1009. 10.1182/blood-2019-01-895110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Björkqvist J; de Maat S; Lewandrowski U; Di Gennaro A; Oschatz C; Schönig K; Nöthen MM; Drouet C; Braley H; Nolte MW; Sickmann A; Panousis C; Maas C; Renné T Defective glycosylation of coagulation factor XII underlies hereditary angioedema type III. J. Clin. Invest, 2015, 125(8), 3132–3146. 10.1172/JCI77139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tillman B; Gailani D Inhibition of factors XI and XII for prevention of thrombosis induced by artificial surfaces. Semin. Thromb. Hemost, 2018, 44(1), 060–069. 10.1055/s-0037-1603937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Weitz JI; Fredenburgh JC Factors XI and XII as targets for new anticoagulants. Front. Med, 2017, 4, 19. 10.3389/fmed.2017.00019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Raghunathan V; Zilberman-Rudenko J; Olson SR; Lupu F; McCarty OJT; Shatzel JJ The contact pathway and sepsis. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost, 2019, 3(3), 331–339. 10.1002/rth2.12217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Göbel K; Pankratz S; Asaridou CM; Herrmann AM; Bittner S; Merker M; Ruck T; Glumm S; Langhauser F; Kraft P; Krug TF; Breuer J; Herold M; Gross CC; Beckmann D; Korb-Pap A; Schuhmann MK; Kuerten S; Mitroulis I; Ruppert C; Nolte MW; Panousis C; Klotz L; Kehrel B; Korn T; Langer HF; Pap T; Nieswandt B; Wiendl H; Chavakis T; Kleinschnitz C; Meuth SG Blood coagulation factor XII drives adaptive immunity during neuroinflammation via CD87-mediated modulation of dendritic cells. Nat. Commun, 2016, 7(1), 11626. 10.1038/ncomms11626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ziliotto N; Baroni M; Straudi S; Manfredini F; Mari R; Menegatti E; Voltan R; Secchiero P; Zamboni P; Basaglia N; Marchetti G; Bernardi F Coagulation factor XII levels and intrinsic thrombin generation in multiple sclerosis. Front. Neurol, 2018, 9, 245. 10.3389/fneur.2018.00245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zamolodchikov D; Chen ZL; Conti BA; Renné T; Strickland S Activation of the factor XII-driven contact system in Alzheimer’s disease patient and mouse model plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2015, 112(13), 4068–4073. 10.1073/pnas.1423764112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zamolodchikov D; Renné T; Strickland S The Alzheimer’s disease peptide β-amyloid promotes thrombin generation through activation of coagulation factor XII. J. Thromb. Haemost, 2016, 14(5), 995–1007. 10.1111/jth.13209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chen ZL; Revenko AS; Singh P; MacLeod AR; Norris EH; Strickland S Depletion of coagulation factor XII ameliorates brain pathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease mice. Blood, 2017, 129(18), 2547–2556. 10.1182/blood-2016-11-753202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hopp S; Albert-Weissenberger C; Mencl S; Bieber M; Schuhmann MK; Stetter C; Nieswandt B; Schmidt PM; Monoranu CM; Alafuzoff I; Marklund N; Nolte MW; Sirén AL; Kleinschnitz C Targeting coagulation factor XII as a novel therapeutic option in brain trauma. Ann. Neurol, 2016, 79(6), 970–982. 10.1002/ana.24655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hopp S; Nolte MW; Stetter C; Kleinschnitz C; Sirén AL; Albert-Weissenberger C Alle via tion of secondary brain injury, posttraumatic inflammation, and brain edema formation by inhibition of factor XIIa. J. Neuroinflammation, 2017, 14(1), 39. 10.1186/s12974-017-0815-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Albert-Weissenberger C; Hopp S; Nieswandt B; Sirén AL; Kleinschnitz C; Stetter C How is the formation of microthrombi after traumatic brain injury linked to inflammation? J. Neuroimmunol, 2019, 326, 9–13. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Girolami A; Candeo N; De Marinis GB; Bonamigo E; Girolami B Comparative incidence of thrombosis in reported cases of deficiencies of factors of the contact phase of blood coagulation. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis, 2011, 31(1), 57–63. 10.1007/s11239-010-0495-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gailani D; Renné T The intrinsic pathway of coagulation: A target for treating thromboembolic disease? J. Thromb. Haemost, 2007, 5(6), 1106–1112. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02446.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Renné T; Pozgajová M; Grüner S; Schuh K; Pauer HU; Burfeind P; Gailani D; Nieswandt B Defective thrombus formation in mice lacking coagulation factor XII. J. Exp. Med, 2005, 202(2), 271–281. 10.1084/jem.20050664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kleinschnitz C; Stoll G; Bendszus M; Schuh K; Pauer HU; Burfeind P; Renné C; Gailani D; Nieswandt B; Renné T Targeting coagulation factor XII provides protection from pathological thrombosis in cerebral ischemia without interfering with hemostasis. J. Exp. Med, 2006, 203(3), 513–518. 10.1084/jem.20052458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Müller F; Mutch NJ; Schenk WA; Smith SA; Esterl L; Spronk HM; Schmidbauer S; Gahl WA; Morrissey JH; Renné T Platelet polyphosphates are proinflammatory and procoagulant mediators in vivo. Cell, 2009, 139(6), 1143–1156. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Larsson M; Rayzman V; Nolte MW; Nickel KF; Björkqvist J; Jämsä A; Hardy MP; Fries M; Schmidbauer S; Hedenqvist P; Broomé M; Pragst I; Dickneite G; Wilson MJ; Nash AD; Panousis C; Renné T A factor XIIa inhibitory antibody provides thromboprotection in extracorporeal circulation without increasing bleeding risk. Sci. Transl. Med, 2014, 6(222), 222ra17. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hagedorn I; Schmidbauer S; Pleines I; Kleinschnitz C; Kronthaler U; Stoll G; Dickneite G; Nieswandt B Factor XIIa inhibitor recombinant human albumin Infestin-4 abolishes occlusive arterial thrombus formation without affecting bleeding. Circulation, 2010, 121(13), 1510–1517. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.924761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Xu Y; Cai TQ; Castriota G; Zhou Y; Hoos L; Jochnowitz N; Loewrigkeit C; Cook J; Wickham A; Metzger J; Ogletree M; Seiffert D; Chen Z Factor XIIa inhibition by Infestin-4: In vitro mode of action and in vivo antithrombotic benefit. Thromb. Haemost, 2014, 111(4), 694–704. 10.1160/TH13-08-0668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chen JW; Figueiredo JL; Wojtkiewicz GR; Siegel C; Iwamoto Y; Kim DE; Nolte MW; Dickneite G; Weissleder R; Nahrendorf M Selective factor XIIa inhibition attenuates silent brain ischemia: Application of molecular imaging targeting coagulation pathway. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging, 2012, 5(11), 1127–1138. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].May F; Krupka J; Fries M; Thielmann I; Pragst I; Weimer T; Panousis C; Nieswandt B; Stoll G; Dickneite G; Schulte S; Nolte MW FXIIa inhibitor rHA-Infestin-4: Safe thromboprotection in experimental venous, arterial and foreign surface-induced thrombosis. Br. J. Haematol, 2016, 173(5), 769–778. 10.1111/bjh.13990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Revenko AS; Gao D; Crosby JR; Bhattacharjee G; Zhao C; May C; Gailani D; Monia BP; MacLeod AR Selective depletion of plasma prekallikrein or coagulation factor XII inhibits thrombosis in mice without increased risk of bleeding. Blood, 2011, 118(19), 5302–5311. 10.1182/blood-2011-05-355248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yau JW; Liao P; Fredenburgh JC; Stafford AR; Revenko AS; Monia BP; Weitz JI Selective depletion of factor XI or factor XII with antisense oligonucleotides attenuates catheter thrombosis in rabbits. Blood, 2014, 123(13), 2102–2107. 10.1182/blood-2013-12-540872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Matafonov A; Leung PY; Gailani AE; Grach SL; Puy C; Cheng Q; Sun M; McCarty OJT; Tucker EI; Kataoka H; Renné T; Morrissey JH; Gruber A; Gailani D Factor XII inhibition reduces thrombus formation in a primate thrombosis model. Blood, 2014, 123(11), 1739–1746. 10.1182/blood-2013-04-499111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Iwaki T; Cruz-Topete D; Castellino FJ A complete factor XII deficiency does not affect coagulopathy, inflammatory responses, and lethality, but attenuates early hypotension in endotoxemic mice. J. Thromb. Haemost, 2008, 6(11), 1993–1995. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03142.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Stroo I; Zeerleder S; Ding C; Luken B; Roelofs J; de Boer O; Meijers J; Castellino F; van ’t Veer C; van der Poll T Coagulation factor XI improves host defence during murine pneumonia-derived sepsis independent of factor XII activation. Thromb. Haemost, 2017, 117(8), 1601–1614. 10.1160/TH16-12-0920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Stroo I; Ding C; Novak A; Yang J; Roelofs JJTH; Meijers JCM; Revenko AS; van’t Veer C; Zeerleder S; Crosby JR; van der Poll T Inhibition of the extrinsic or intrinsic coagulation pathway during pneumonia-derived sepsis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol, 2018, 315(5), L799–L809. 10.1152/ajplung.00014.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tucker EI; Verbout NG; Leung PY; Hurst S; McCarty OJT; Gailani D; Gruber A Inhibition of factor XI activation attenuates inflammation and coagulopathy while improving the survival of mouse polymicrobial sepsis. Blood, 2012, 119(20), 4762–4768. 10.1182/blood-2011-10-386185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Pixley RA; De La Cadena R; Page JD; Kaufman N; Wyshock EG; Chang A; Taylor FB Jr.; Colman RW The contact system contributes to hypotension but not disseminated intravascular coagulation in lethal bacteremia. In vivo use of a monoclonal anti-factor XII antibody to block contact activation in baboons. J. Clin. Invest, 1993, 91(1), 61–68. 10.1172/JCI116201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jansen PM; Pixley RA; Brouwer M; de Jong IW; Chang AC; Hack CE; Taylor FBJ Jr.; Colman RW Inhibition of factor XII in septic baboons attenuates the activation of complement and fibrinolytic systems and reduces the release of interleukin-6 and neutrophil elastase. Blood, 1996, 87(6), 2337–2344. 10.1182/blood.V87.6.2337.bloodjournal8762337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Silasi R; Keshari RS; Lupu C; Van Rensburg WJ; Chaaban H; Regmi G; Shamanaev A; Shatzel JJ; Puy C; Lorentz CU; Tucker EI; Gailani D; Gruber A; McCarty OJT; Lupu F Inhibition of contact-mediated activation of factor XI protects baboons against S aureus-induced organ damage and death. Blood Adv., 2019, 3(4), 658–669. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018029983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mackman N; Bergmeier W; Stouffer GA; Weitz JI Therapeutic strategies for thrombosis: New targets and approaches. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov, 2020, 19(5), 333–352. 10.1038/s41573-020-0061-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kalinin DV Factor XII(a) inhibitors: A review of the patent literature. Expert Opin Ther Pat., 2021, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Korff M; Imberg L; Will JM; Bückreiß N; Kalinina SA; Wenzel BM; Kastner GA; Daniliuc CG; Barth M; Ovsepyan RA; Butov KR; Humpf HU; Lehr M; Panteleev MA; Poso A; Karst U; Steinmetzer T; Bendas G; Kalinin DV Acylated 1 H - 1, 2,4-triazol-5-amines targeting human coagulation factor XIIa and thrombin: Conventional and microscale synthesis, anticoagulant properties, and mechanism of action. J. Med. Chem, 2020, 63(21), 13159–13186. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bouckaert C; Serra S; Rondelet G; Dolušić E; Wouters J; Dogné JM; Frédérick R; Pochet L Synthesis, evaluation and structure-activity relationship of new 3-carboxamide coumarins as FXIIa inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem, 2016, 110, 181–194. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Dementiev A; Silva A; Yee C; Li Z; Flavin MT; Sham H; Partridge JR Structures of human plasma β-factor XIIa cocrystallized with potent inhibitors. Blood Adv., 2018, 2(5), 549–558. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018016337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kar S; Bankston P; Afosah DK; Al-Horani RA Lignosulfonic acid sodium is a noncompetitive inhibitor of human factor XIa. Pharmaceuticals, 2021, 14(9), 886. 10.3390/ph14090886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Al-Horani RA; Aliter KF; Kar S; Mottamal M Sulfonated nonsaccharide heparin mimetics are potent and noncompetitive inhibitors of human neutrophil elastase. ACS Omega, 2021, 6(19), 12699–12710. 10.1021/acsomega.1c00935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kar S; Mottamal M; Al-Horani RA Discovery of benzyl tetra-phosphonate derivative as inhibitor of human factor xia. ChemistryOpen, 2020, 9(11), 1161–1172. 10.1002/open.202000277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Al-Horani RA; Clemons D; Mottamal M The in vitro effects of pentamidine isethionate on coagulation and fibrinolysis. Molecules, 2019, 24(11), 2146. 10.3390/molecules24112146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Obaidullah AJ; Al-Horani RA Discovery of chromen-7-yl furan-2-carboxylate as a potent and selective factor Xia inhibitor. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem, 2017, 15(1), 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Boothello RS; Al-Horani RA; Desai UR Glycosaminoglycan-protein interaction studies using fluorescence spectroscopy. Methods Mol. Biol, 2015, 1229, 335–353. 10.1007/978-1-4939-1714-3_27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Gailani D; Smith SB Structural and functional features of factor XI. J Thromb Haemost., 2009, 7(Suppl 1), 75–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Geng Y; Verhamme IM; Smith SA; Cheng Q; Sun M; Sheehan JP; Morrissey JH; Gailani D Factor XI anion-binding sites are required for productive interactions with polyphosphate. J. Thromb. Haemost, 2013, 11(11), 2020–2028. 10.1111/jth.12414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Cohen AT; Harrington RA; Goldhaber SZ; Hull RD; Wiens BL; Gold A; Hernandez AF; Gibson CM APEX Investigators. Extended thromboprophylaxis with betrixaban in acutely Ill medical patients. N. Engl. J. Med, 2016, 375(6), 534–544. 10.1056/NEJMoa1601747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Schulman S; Kakkar AK; Goldhaber SZ; Schellong S; Eriksson H; Mismetti P; Christiansen AV; Friedman J; Le Maulf F; Peter N; Kearon C Treatment of acute venous thromboembolism with dabigatran or warfarin and pooled analysis. Circulation, 2014, 129(7), 764–772. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Agnelli G; Buller HR; Cohen A; Curto M; Gallus AS; Johnson M; Masiukiewicz U; Pak R; Thompson J; Raskob GE; Weitz JI Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med, 2013, 369(9), 799–808. 10.1056/NEJMoa1302507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Büller HR; Décousus H; Grosso MA; Mercuri M; Middeldorp S; Prins MH; Raskob GE; Schellong SM; Schwocho L; Segers A; Shi M; Verhamme P; Wells P Edoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med, 2013, 369(15), 1406–1415. 10.1056/NEJMoa1306638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Alamneh EA; Chalmers L; Bereznicki LR Suboptimal use of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: Has the introduction of direct oral anticoagulants improved prescribing practices? Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs, 2016, 16(3), 183–200. 10.1007/s40256-016-0161-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Lutz J; Jurk K; Schinzel H Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with chronic kidney disease: Patient selection and special considerations. Int. J. Nephrol. Renovasc. Dis, 2017, 10, 135–143. 10.2147/IJNRD.S105771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Black-Maier E; Piccini JP Oral anticoagulation in end-stage renal disease and atrial fibrillation: Is it time to just say no to drugs? Heart, 2017, 103(11), 807–808. 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Heine GH; Brandenburg V Anticoagulation, atrial fibrillation, and chronic kidney disease-whose side are you on? Kidney Int., 2017, 91(4), 778–780. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Al-Horani RA; Afosah DK Recent advances in the discovery and development of factor XI/XIa inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev, 2018, 38(6), 1974–2023. 10.1002/med.21503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]