Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association of air pollution exposure with the severity of interstitial lung disease (ILD) at diagnosis and ILD progression among patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc)-associated ILD.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective two-center study of patients with SSc-associated ILD diagnosed between 2006 and 2019. Exposure to the air pollutants particulate matter of up to 10 and 2.5 µm in diameter (PM10, PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and ozone (O3) was assessed at the geolocalization coordinates of the patients’ residential address. Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between air pollution and severity at diagnosis according to the Goh staging algorithm, and progression at 12 and 24 months.

Results

We included 181 patients, 80% of whom were women; 44% had diffuse cutaneous scleroderma, and 56% had anti-topoisomerase I antibodies. ILD was extensive, according to the Goh staging algorithm, in 29% of patients. O3 exposure was associated with the presence of extensive ILD at diagnosis (adjusted OR: 1.12, 95% CI 1.05–1.21; p value = 0.002). At 12 and 24 months, progression was noted in 27/105 (26%) and 48/113 (43%) patients, respectively. O3 exposure was associated with progression at 24 months (adjusted OR: 1.10, 95% CI 1.02–1.19; p value = 0.02). We found no association between exposure to other air pollutants and severity at diagnosis and progression.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that high levels of O3 exposure are associated with more severe SSc-associated ILD at diagnosis, and progression at 24 months.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12931-023-02463-w.

Keywords: Systemic sclerosis, Scleroderma, Interstitial lung disease, Air pollution, Ozone, Particulate matter, Nitrogen dioxide, Severity, Progression, CHIMERE

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a systemic disease characterized by autoimmune features, and endothelial and fibroblast dysfunctions, resulting in vasculopathy and tissue fibrosis. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is common in SSc. In a recent nationwide cohort study in Norway, high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) showed that half the patients had ILD [1]. ILD has a major impact on the morbidity and mortality of SSc patients, one third of whom die from pulmonary fibrosis [2]. The course of SSc-associated ILD is heterogeneous [3]. Extensive lung parenchyma involvement according to the Goh staging algorithm [4] and short-term functional decline [5, 6] have been described as predictors of poorer survival, but the factors underlying the prognostic heterogeneity between patients are not fully understood. Nevertheless, ethnic, immunological and phenotypic characteristics of SSc, such as Afro-Caribbean origin, anti-topoisomerase I antibodies, esophageal diameter, reflux/dysphagia symptoms, modified Rodnan skin score, diffuse cutaneous phenotype (dcSSc) and being male [3, 7–9], have been shown to be associated with ILD severity and progression.

Air pollution has been implicated in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in a number of studies. The incidence of IPF was associated with levels of exposure to nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and particulate matter of up to 2.5 µm in diameter (PM2.5) [10, 11]. Disease severity has been linked to exposure to particulate matter of up to 10 µm or up to 2.5 µm in diameter (PM10 and PM2.5) [12]. Disease exacerbations were linked to exposure to ozone (O3), NO2, PM10, and PM2.5 [13–16], and functional decline with exposure to PM10 [14]. Mortality was associated with exposure to PM10, PM2.5 and NO2 [12, 14, 17–19]. A role for air pollution in SSc was first suggested by a British study reporting a higher prevalence of SSc in the London region, particularly in boroughs close to airports, than in the West Midlands [20]. More recently, an Italian study on 88 SSc patients found that benzene exposure was positively correlated with skin score and inversely correlated with the diffusion of carbon monoxide in the lung (DLCO) [21]. However, to our knowledge, no larger-scale study has evaluated the impact of air pollution on SSc-associated ILD.

We conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the contribution of the principal air pollutants (PM10, PM2.5, NO2, and O3) to the natural course of SSc-associated ILD. The primary objective was to determine the association between air pollution exposure and disease severity at diagnosis according to the Goh staging algorithm [4]. The secondary objective was to evaluate the impact of air pollution on disease progression.

Patients and methods

Patients

The study population consisted of patients identified from the French hospital discharge database (Programme de Médicalisation des Systèmes d'Information [PMSI]) seen from January 1 2006 to December 31 2019 at two French centers in the Paris area (the internal medicine department of Cochin Hospital, Paris, and the respiratory medicine, internal medicine and dermatology departments of Avicenne Hospital, Bobigny). For inclusion in the study, patients had to have SSc, defined according to the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) classification criteria [22] and ILD, diagnosed on HRCT, with PFT results available from the 3 months immediately before or after SSc-associated ILD diagnosis. The patients also had to be at least 18 years old at the time of SSc-associated ILD diagnosis. Patients living abroad or in French overseas territories were excluded.

Scleroderma phenotype (dcSSc, limited cutaneous SSc, sine scleroderma SSc), associated non-pulmonary organ’s involvements, specific auto-antibodies, time between ILD diagnosis and first non-Raynaud symptom were collected. Follow-up PFT results were collected at 6, 12, 18 and 24 (± 3) months and last follow-up. Pulmonary volumes and flow (total lung capacity [TLC], forced vital capacity [FVC], and forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1]) were calculated as a percentage of predicted values with the Global Lung Initiative equations. A recourse to lung transplantation and the occurrence of death were also recorded. Initial HRCT data and HRCT data obtained at 2 years of follow-up (HRCT performed on the date closest to 2 years) were reviewed and a consensus interpretation was reached between expert radiologists blinded to clinical symptoms, autoantibody subtype and treatment. The expert radiologists concerned had 7 (S.T.B.), 7 (G.C.), 10 (S.J.), and 20 (P-Y.B.) years of experience in chest imaging. The extent of lesions (honeycombing, reticulations, ground-glass opacities and/or consolidations) was quantified over the whole lung, with the method described by Akira et al. [23], in which the lungs are divided into six zones, three for each lung (upper zone: above the carina, middle zone: between the carina and the inferior pulmonary veins, lower zone: below the inferior pulmonary veins). The overall extent of parenchymal abnormalities is estimated by averaging the estimated extent of the disease in the six zones. The radiologists attributed an ILD pattern from the following list to each HRCT image: usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), organizing pneumonia (OP), non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), early ILD, unclassifiable ILD. Patterns classified as UIP or probable UIP according to American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Asociación Latinoamericana de Tórax (ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT) Clinical Practice Guidelines were classified here as UIP [24]. A NSIP pattern was attributed to HRCT with predominant ground-glass opacities, with or without reticulations or traction bronchiectasis, with a predominantly basal distribution, and with no more than minimal honeycombing [25]. An OP pattern was defined as patchy, often migratory consolidation in a subpleural, peribronchial, or band-like pattern, commonly associated with ground-glass opacity according to the ATS/ERS criteria [26]. Early and unclassifiable ILD were labelled as indeterminate ILD.

Exposure to air pollution

The concentrations of air pollutants were obtained with the CHIMERE chemistry-transport model for mainland France [27]. This model uses meteorological fields, primary pollutant emissions, and chemical boundary conditions to calculate the atmospheric concentrations of gas and particles over local to continental domains (with a resolution from 1 km to 1 degree). In this study, we used this model to obtain, for the geolocalized address of each patient, the mean annual concentrations of NO2, O3, and PM10 available from 2000 to 2019 and of PM2.5 available from 2009 to 2019, with a resolution of 2 km. Two periods of exposure were defined: (1) exposure before ILD diagnosis was calculated by determining the mean concentrations of NO2, O3, PM10 and PM2.5 for the 5 years preceding SSc-associated ILD diagnosis; (2) exposure after ILD diagnosis was estimated from the mean annual concentrations in the year of ILD diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as absolute numbers (percentages) for categorical variables and as the median (interquartile range, IQR) or mean (standard deviation, SD) for quantitative variables.

Severity at diagnosis

Multiple logistic regression models were constructed to evaluate the impact of pre-ILD diagnosis air pollution on ILD severity at diagnosis, as evaluated with the Goh staging algorithm [4]. ILD was classified as extensive or limited: cases with an ILD extension on HRCT > 30% were considered extensive; cases with an extension ≤ 10% were considered limited; patients for whom extension was intermediate were classified as having extensive ILD if FVC < 70%, and limited ILD if FVC ≥ 70%.

We performed a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the impact of a change in judgement criteria, using other severity parameters: TLC < 70%, FVC < 70%, DLCO < 40%, composite physiological index (CPI) > 40 and ILD extension on HRCT > 10% in logistic regression models, and considering TLC, FVC, DLCO, CPI and ILD extent on HRCT at baseline as continuous variables in linear mixed models.

Evolution of ILD

We used two methods to determine whether air pollution exposure after ILD diagnosis was associated with evolution of ILD during follow-up.

First, we used multiple logistic regression models and Cox proportional hazard models to evaluate the association between air pollution exposure and the occurrence of progression within 24 months following ILD diagnosis. Functional decline was calculated based on relative changes in FVC or DLCO [(baseline value − follow-up value)/baseline value], with FVC measured in liters and DLCO as a percentage of the predicted value. Progression was defined as a relative decrease of at least 10% in FVC compared to baseline; or as a relative decrease between 5 and 10% in FVC plus a relative decrease in DLCO of at least 15% according to Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Connective Tissue Disease—ILD criteria [28]. Patients died or who had required lung transplantation during the considered follow-up period (12 or 24 months) were considered to have undergone progression.

A sensitivity analysis was performed with functional and radiological surrogates, defined as relative decline in FVC ≥ 10% or ≥ 5% and relative decline in DLCO ≥ 15%, ≥ 10% or ≥ 7.5% at 24 months, and the occurrence of radiological progression at 24 months. Radiological progression was defined in accordance with the 2022 ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Guidelines [29].

Second, we used linear mixed models to identify predictors of change in FVC (absolute decline in mL) or DLCO (absolute decline in % of predicted) over time. This model included a single, subject-level random effect, and fixed effects for potential predictors of change and time.

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the impact of air pollution on transplant-free survival, considering the time from ILD diagnosis to death or lung transplantation or last follow-up.

All multiple logistic regression models, linear mixed models and Cox proportional hazards models were adjusted for factors identified in univariate analysis, which were included in the multivariate model if the p value was < 0.2 (|t| value > 1.3 for mixed linear models). Final multivariate models included factors associated with the outcome in multivariate analysis (p value < 0.2 or |t| value > 1.3 for mixed linear models). Potential predictors analyzed were factors already shown to be associated with SSc-associated ILD severity, or progression of fibrosing ILD [30], or potential confounders: sex, age at ILD diagnosis, tobacco smoking, dcSSc, positive anti-topoisomerase I antibodies, UIP pattern, time from first non-Raynaud phenomenon, and for follow-up outcomes: baseline FVC and DLCO, ILD extension on initial HRCT, and initiation of an immunosuppressive therapy. We also considered patient’s continent of birth, socio-economic status, evaluated through the socio-professional category defined by the French Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (INSEE), and year of ILD diagnosis as potential confounders for health outcomes.

Statistical analysis was performed with R software V.4.1.2, and statistical significance was defined as a p value < 0.05 (|t| value > 2 for mixed linear models).

Ethical considerations

This study received Institutional Review Board approval (Comité Local d’Ethique pour la Recherche Clinique des HUPSSD, CLEA-2020-150) and the requirement for signed informed consent was waived according to French legislation (CNIL Reference methodology).

Results

Study population

We screened 269 patients with SSc-associated ILD defined on HRCT. We excluded 88 cases because they had ILD diagnosed before 2006 (n = 39), had no PFT data from a period within three months of diagnosis (n = 36), were less than 18 years old (n = 1), or were living abroad or in French overseas territories (n = 12) (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). We included 181 patients, 79.6% of whom were female. Most of patients were born in Europe (58%), 30.9% were born in Africa, and 6.6% in Asia. Thirteen percent of patients belonged to the working-class, and 6% had no professional activity. Median age at SSc diagnosis was of 53 years (IQR: 42.5–64 years); 44.2% had dcSSc, with anti-topoisomerase I antibodies in 55.8% and anti-centromere antibodies in 11.0% (Table 1). ILD was extensive in 53 of 181 cases (29.3%). Median (IQR) FVC at diagnosis was 78.5% (63.7–93.8), and median (IQR) DLCO was 55% (42–66%). NSIP was the most frequent radiological pattern (63.5%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease included in the study

| Total population N = 181 |

Extensive ILD N = 53 |

Limited ILD N = 128 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 144 (79.6) | 40 (75.5) | 104 (81.3) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoker, n (%) | 113/172 (65.7) | 38/51 (74.5) | 75/121 (62.0) |

| Former smoker, n (%) | 16/172 (9.3) | 2/51 (3.9) | 14/121 (11.6) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 43/172 (25.0) | 11/51 (21.6) | 32/121 (26.4) |

| Age at SSc diagnosis (years), median (IQR) | 53 (42.5–64) | 54 (44.5–64) | 53 (42–64.8) |

| Cutaneous phenotype | |||

| Diffuse cutaneous, n (%) | 80 (44.2) | 26 (49.1) | 54 (42.2) |

| Limited cutaneous, n (%) | 89 (46.4) | 25 (47.2) | 64 (50.0) |

| Sine scleroderma, n (%) | 12 (6.6) | 2 (3.8) | 10 (7.8) |

| ScS involvement | |||

| Gastrointestinal, n (%) | 139 (76.8) | 42 (79.2) | 97 (75.8) |

| Cardiac, n (%) | 19 (10.5) | 7 (13.2) | 12 (9.4) |

| Muscular, n (%) | 14 (7.7) | 3 (5.7) | 11 (8.6) |

| Renal, n (%) | 5 (2.8) | 1 (1.9) | 4 (3.1) |

| Autoantibodies | |||

| Anti-centromere, n (%) | 20 (11.0) | 1 (1.9) | 19 (14.8) |

| Anti-topoisomerase I, n (%) | 101 (55.8) | 37 (69.8) | 64 (50.0) |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III, n (%) | 11 (6.1) | 4 (7.5) | 7 (5.5) |

| Time from first non-Raynaud symptom (years) to ILD diagnosis, median (IQR) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–7) |

| Pulmonary function | |||

| FVC (% predicted), median (IQR) | 78.5 (63.7–93.8) | 61.7 (50.5–69.8) | 84.1 (74.5–98.6) |

| TLC (% predicted), median (IQR) | 83.4 (71.8–99.2) | 70.6 (61.9–76.0) | 92.4 (78.5–102.2) |

| FEV1 (% predicted), median (IQR) | 81.1 (67.5–94.9) | 67.9 (57.4–74.3) | 86.1 (73.0–97.6) |

| DLCO (% predicted), median (IQR) | 55.0 (42.0–66.0) | 43.5 (33.8–51.0) | 61 (49.0–71.5) |

| Composite physiological index, median (IQR) | 40.9 (28.8–50.0) | 52.0 (47.1–59.5) | 35.4 (25.8–45.1) |

| Radiological pattern | |||

| UIP | 13 (7.2) | 6 (12.1) | 7 (5.5) |

| NSIP | 115 (63.5) | 43 (75.9) | 72 (56.2) |

| Indeterminate ILD | 53 (29.3) | 4 (10.3) | 49 (38.3) |

| Extent of ILD (%), median (IQR) | 10 (5–20) | 30 (16–35) | 5 (5–12) |

| Emphysema association, n (%) | 34 (18.8) | 9 (17.0) | 25 (19.5) |

| Extent of emphysema (%), median (IQR) | 5 (3–10) | 3 (3–7.5) | 5 (3–10) |

| Hiatal hernia | 29 (16.0) | 9 (17.2) | 20 (15.6) |

| Esophageal dilation | 92 (47.9) | 30 (51.7) | 62 (48.4) |

| Immunosuppressive therapy initiationa, n (%) | 81 (44.8) | 31 (58.5) | 50 (39.1) |

DLCO diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide across the lung, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in one second, FVC forced vital capacity, ILD interstitial lung disease, NSIP nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, TLC total lung capacity, UIP usual interstitial pneumonia

aInitiation of any immunosuppressive therapy after ILD diagnosis (excluding steroids)

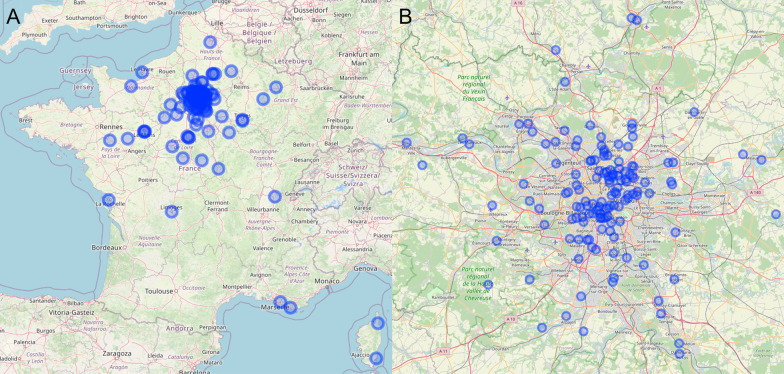

All the patients included in this study were resident in mainland France, and 139/181 (77%) were living in the Paris region (Fig. 1). The mean (SD) exposure levels during the 5 years preceding ILD diagnosis for the study population were 27.9 (8.4) µg/m3 for NO2 (range 9.9–42.2), 44.2 (6.0) µg/m3 for O3 (range 36.5–74.6), 23.5 (3.3) µg/m3 for PM10 (range 15.6–30.0) and 15.6 (2.4) µg/m3 for PM2.5 (range 9.6–20.3). About 99.5% of patients had pre-ILD diagnosis exposure levels above the recent WHO recommendations for NO2, and 100% had pre-ILD diagnosis exposure levels above WHO recommendations for PM10 and PM2.5 [31].

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the patients included in the study across mainland France. A Global distribution of the patients’ residential addresses in mainland France; B focus on the Parisian region (Ile-de-France)

ILD severity at diagnosis and air pollution exposure

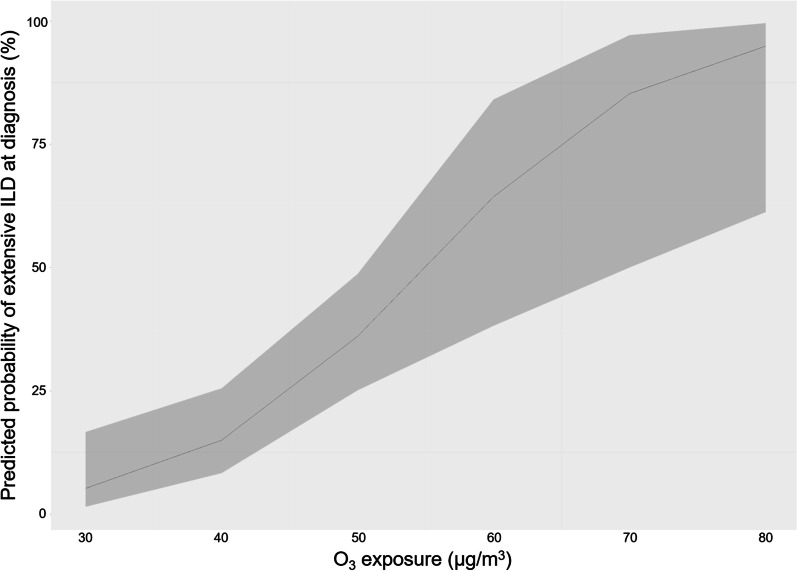

In univariate analysis, pre-ILD diagnosis O3 exposure tended to be associated with the presence of extensive ILD at diagnosis (OR: 1.05, 95% CI 1.00–1.11; p value = 0.06) (Additional file 1: Table S1). Parameters included in the final multivariate model were those associated with the presence of an extensive ILD in multivariate analysis: a non-European place of birth (adjusted OR for birth in Europe: 0.23, 95% CI 0.11–0.63; p value = 0.003), tobacco smoking (adjusted OR: 0.33, 95% CI 0.10–0.92; p value = 0.04), anti-topoisomerase I antibodies (adjusted OR: 4.56, 95% CI 1.75–13.43; p value = 0.003), UIP pattern (adjusted OR: 3.48, 95% CI 0.64–18.45; p value = 0.14), time between first non-Raynaud symptom and ILD diagnosis (adjusted OR: 0.93, 95% CI 0.84–1.01; p value = 0.16) and year of ILD diagnosis (adjusted OR: 1.08, 95% CI 0.97–1.22; p value = 0.19). In this final multivariate model, O3 exposure was significantly associated with the presence of extensive ILD (adjusted OR: 1.12, 95% CI 1.05–1.21; p value = 0.002) (Table 2). Thus, the predicted probability of extensive ILD for mean exposures of 30 µg/m3 and 60 µg/m3 were respectively 5 (95% CI 1–17) % and 64 (95% CI 38–84) % (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Association of air pollution (pre-diagnosis exposure) with the severity of SSc-associated ILD at diagnosis (extensive ILD)

| OR | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| NO2 | 0.95 (0.91–1.00) | 0.08 |

| O3 | 1.12 (1.05–1.21) | 0.002 |

| PM10 | 0.91 (0.75–1.11) | 0.36 |

| PM2.5 | 0.87 (0.64–1.20) | 0.39 |

Logistic regression models adjusted for birth in Europe, tobacco smoking, anti-topoisomerase I antibodies positivity, usual interstitial pneumonia pattern, time between first non-Raynaud symptom and ILD diagnosis, and year of ILD diagnosis

ILD: interstitial lung disease; NO2: nitrogen dioxide; O3: ozone; PM10 and PM2.5: particles with a 50% cutoff aerodynamic diameter of 10 µm and 2.5 µm, respectively

Fig. 2.

Predicted probability of presence of an extensive interstitial lung disease (ILD) at diagnosis according to ozone exposure in final multivariate logistic regression model

NO2 exposure tended to be associated with the presence of a limited ILD (adjusted OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.91–1.00; p value = 0.08). We found no association between the presence of extensive ILD and exposure to PMs. The association between extensive ILD at diagnosis and O3 exposure was confirmed in two-pollutant model (Table 3), whereas no association with NO2 exposure was found after adjustment for other pollutants exposure (OR after adjustment for O3 exposure: 1.09, 95% CI 0.99–1.24; p value = 0.21) (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Table 3.

Association of pre-diagnosis exposure to ozone pollution with the severity of SSc-associated ILD at diagnosis (extensive ILD): two-pollutant model

| OR | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| O3 | ||

| + NO2 | 1.24 (1.08–1.51) | 0.007 |

| + PM10 | 1.16 (1.06–1.30) | 0.002 |

| + PM2.5 | 1.19 (1.06–1.34) | 0.003 |

Logistic regression model adjusted for birth in Europe, tobacco smoking, anti-topoisomerase I antibodies positivity, usual interstitial pneumonia pattern, time between first non-Raynaud symptom and ILD diagnosis and year of ILD diagnosis

ILD: interstitial lung disease; NO2: nitrogen dioxide; O3: ozone; PM10 and PM2.5: particles with a 50% cutoff aerodynamic diameter of 10 µm and 2.5 µm, respectively

In the sensitivity analysis, exposure to O3 was associated with a TLC < 70% (adjusted OR: 1.07, 95% CI 1.01–1.15; p value = 0.03), and an extension on HRCT > 10% (adjusted OR: 1.07, 95% CI 1.01–1.14; p value = 0.03) (Table 4). Considering baseline functional and radiological data as continuous parameters in mixed linear models, exposure to O3 was also negatively associated with DLCO (Slope estimate: − 0.51 (Standard Error: 0.22), t value = 2.29, p value = 0.02) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association of air pollution (pre-diagnosis exposure) with the severity of systemic sclerosis-associated ILD at diagnosis: sensitivity analysis

| FVC < 70%a | TLC < 70%a | DLCO < 40%a | CPI > 40a | Extension > 10%a | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p value | OR | p value | OR | p value | OR | p value | OR | p value | ||||||

| NO2 | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 0.72 | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.33 | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 0.18 | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 0.91 | 0.96 (0.92–1.00) | 0.06 | |||||

| O3 | 1.07 (0.98–1.10) | 0.21 | 1.07 (1.01–1.15) | 0.03 | 1.05 (0.98–1.11) | 0.16 | 1.03 (0.97–1.11) | 0.36 | 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | 0.03 | |||||

| PM10 | 0.98 (0.83–1.16) | 0.83 | 1.02 (0.83–1.27) | 0.87 | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 0.22 | 1.01 (0.83–1.25) | 0.90 | 0.92 (0.78–1.07) | 0.28 | |||||

| PM2.5 | 0.94 (0.72–1.23) | 0.63 | 0.83 (0.59–1.18) | 0.28 | 0.91 (0.67–1.25) | 0.53 | 0.74 (0.51–1.03) | 0.08 | 0.89 (0.67–1.16) | 0.39 | |||||

| FVC (% th)b | TLC (% th)b | DLCO (%th)b | CPIb | Extensionb | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope estimate (SE) | t value | p value | Slope estimate (SE) | t value | p value | Slope estimate (SE) | t value | p value | Slope estimate (SE) | t value | p value | Slope estimate (SE) | t value | p value | |

| NO2 | − 0.06 (0.20) | − 0.29 | 0.78 | − 0.09 (0.19) | − 0.49 | 0.63 | 0.32 (0.17) | 1.88 | 0.06 | − 0.13 (0.15) | − 0.88 | 0.38 | − 0.13 (0.11) | − 1.10 | 0.27 |

| O3 | − 0.02 (0.27) | − 0.06 | 0.96 | − 0.10 (0.25) | − 0.39 | 0.70 | − 0.51 (0.22) | − 2.29 | 0.02 | 0.31 (0.20) | 1.56 | 0.12 | 0.22 (0.16) | 1.39 | 0.17 |

| PM10 | 0.30 (0.79) | 0.38 | 0.71 | − 0.07 (0.75) | − 0.09 | 0.93 | 1.29 (0.67) | 1.93 | 0.06 | − 0.54 (0.59) | − 0.92 | 0.36 | − 0.15 (0.45) | − 0.34 | 0.73 |

| PM2.5 | 0.43 (1.22) | 0.36 | 0.72 | 0.21 (1.20) | 0.17 | 0.86 | 2.07 (1.05) | 1.97 | 0.05 | − 1.87 (0.92) | − 2.03 | 0.04 | 0.33 (0.74) | 0.45 | 0.65 |

CPI: composite physiological index; DLCO: diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide across the lung; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity; ILD: interstitial lung disease; NO2: nitrogen dioxide; O3: ozone; PM10 and PM2.5: particles with a 50% cutoff aerodynamic diameter of 10 µm and 2.5 µm, respectively; TLC: total lung capacity

aLogistic regression models

bMultiple linear models. Models adjusted for: Anti-topoisomerase I Abs positivity, time between first non-Raynaud symptom and ILD diagnosis, and year of ILD diagnosis for FVC and ILD extent on HRCT; socio-economic status of worker, anti-topoisomerase I Abs positivity, time between first non-Raynaud symptom and ILD diagnosis, and year of ILD diagnosis for TLC; time between first non-Raynaud symptom and ILD diagnosis, and year of ILD diagnosis for CPI and DLCO

ILD evolution and air pollution exposure

Among 167 patients with at least one PFT during follow-up, median (IQR) FVC decline was − 33.4 (− 102; 19.9) mL/year, and median DLCO decline − 1 (− 3.7; 0.5) % of predicted/year. Among patients with PFT at 12 and 24 months, a FVC decline ≥ 10% was observed in 18/97 (18.6%) patients at 12 months and 17/89 (19.1%) patients at 24 months; a DLCO decline ≥ 15% was observed in 12/73 (16.4%) patients at 12 months and 18/65 (27.7%) patients at 24 months (Additional file 1: Table S3). Progression was observed in 27/105 (25.7%) patients at 12 months and 48/113 (42.5%) patients at 24 months (including 8 and 24 deaths respectively, no pulmonary transplantation). Radiological progression was noted in 54/141 patients (38.3%) at 24 months. After a median follow-up of 4.7 years (IQR 2.4–8.0 years), 24 patients (13.3%) had died and two had undergone lung transplantation.

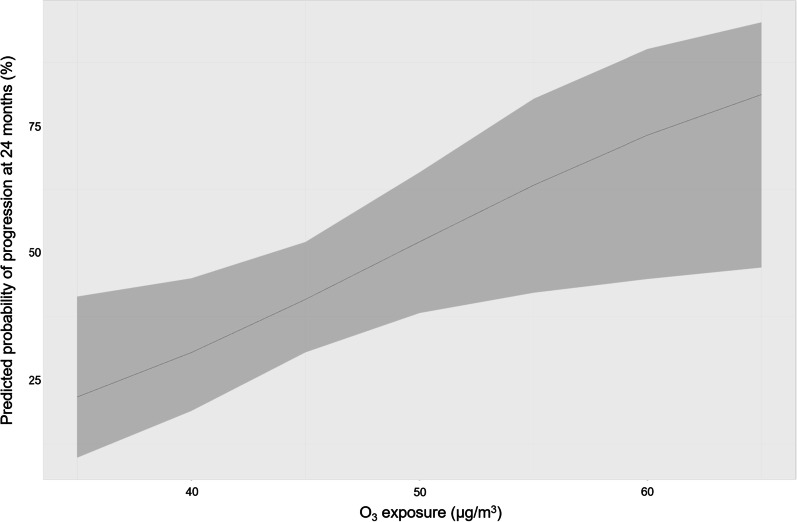

In univariate analysis, O3 exposure during the year of ILD diagnosis was associated with progression at 24 months (OR: 1.08, 96% CI 1.01–1.15; p value = 0.03) (Additional file 1: Table S4). Parameters included in the final multivariate logistic regression model were those associated with progression at 24 months in multivariate analysis: age at ILD diagnosis (adjusted OR: 1.05, 95% CI 1.01–1.10; p value = 0.02), socio-professional status of worker (adjusted OR: 3.47, 95% CI 0.80–16.77; p value = 0.10), dcSSc (adjusted OR: 2.22, 95% CI 0.78–6.65; p value = 0.14), and anti-topoisomerase I antibodies positivity (adjusted OR: 4.97, 95% CI 1.52–18.88; p value = 0.01). In the final multivariate model, O3 exposure was significantly associated with progression at 24 months (adjusted OR: adjusted OR: 1.10, 95% CI 1.02–1.19; p value = 0.02) (Table 5 and Additional file 1: Table S4). Thus, the predicted probability of progression at 24 months for mean exposures of 35 µg/m3 and 65 µg/m3 were respectively 25 (95% CI 13–44) % and 76 (95% CI 41–93) % (Fig. 3).

Table 5.

Association of air pollution (year of diagnosis exposure) with progression at 12 and 24 months

| 12 months | 24 months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p value | OR | p value | |

| NO2 | 0.96 (0.90–1.01) | 0.14 | 0.96 (0.10–1.02) | 0.19 |

| O3 | 1.04 (0.96–1.12) | 0.35 | 1.10 (1.02–1.19) | 0.02 |

| PM10 | 0.97 (0.84–1.10) | 0.61 | 0.93 (0.83–1.04) | 0.18 |

| PM2.5 | 0.94 (0.77–1.13) | 0.51 | 0.89 (0.75–1.04) | 0.15 |

Logistic regression models adjusted for age at ILD diagnosis, socio-professional status of worker, diffuse cutaneous scleroderma, anti-topoisomerase I antibodies positivity

NO2, nitrogen dioxide; O3, ozone; PM10 and PM2.5, particles with a 50% cutoff aerodynamic diameter of 10 µm and 2.5 µm, respectively

Fig. 3.

Predicted probability of progression at 24 months according to ozone exposure in final multivariate logistic regression model

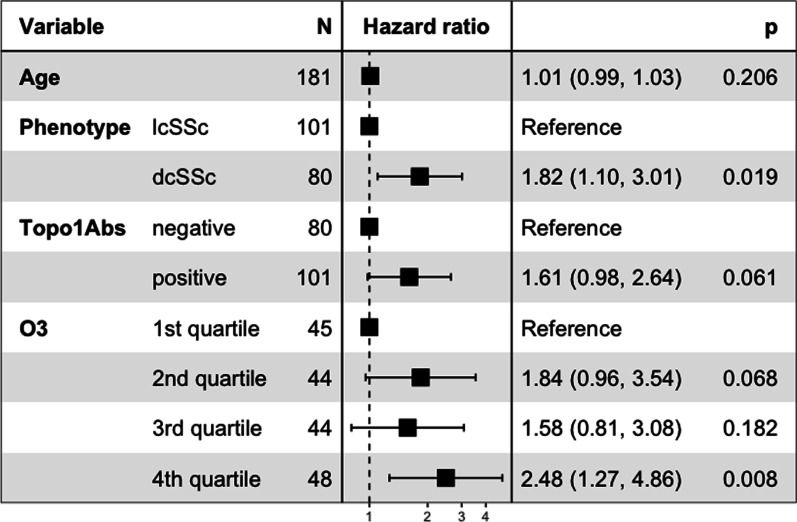

No significant association was found between air pollution exposure on the year of ILD diagnosis and the occurrence of progression at 12 months. O3 exposure was significantly associated with the risk of progression within 24 months following ILD diagnosis in Cox proportional risk model: HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.00–1.08, p value = 0.03. Categorical analysis by quartiles of O3 exposure yielded a hazard ratio of 2.48 (95% CI 1.27–4.86, p value = 0.008) for patient in the fourth quartile compared to the first quartile (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot showing the results of multivariate Cox proportional hazards model for ILD progression within 24 months following SSc-associated ILD diagnosis. dcSSc: diffuse cutaneous scleroderma, lcSSc: limited cutaneous scleroderma; O3: Ozone exposure on the year of ILD diagnosis; Topo1Abs: anti-topoisomerase I antibodies

In the sensitivity analysis, O3 exposure was associated with a FVC decline ≥ 5% (adjusted OR: 1.15, 95% CI 1.03–1.29; p value = 0.02) at 24 months (Additional file 1: Table S5). No association was found between air pollution exposure and a decline of DLCO ≥ 15%, ≥ 10%, or ≥ 7.5% at 24 months (Additional file 1: Table S5) or radiological progression (Additional file 1: Table S6).

In linear mixed models, no significant association was found between air pollution exposure and change in FVC or DLCO over time. No association was found between air pollution exposure at time of ILD diagnosis and transplant-free survival (Additional file 1: Table S7).

Discussion

We investigated the association between the severity of SSc-associated ILD and chronic exposure to PM2.5, PM10, NO2 and O3 in a cohort of SSc patients seen at two hospitals in the Paris area. We observed an association between long-term exposure to O3 and ILD severity at diagnosis, evaluated with the Goh staging algorithm, and according to extension on HRCT, TLC and DLCO. This association was independent of the principal factors associated with the severity of SSc-associated ILD and was confirmed in two-pollutant models. We also found an association between O3 exposure and progression at 24 months. We found no association between exposure to other pollutants and severity at diagnosis and progression.

Ozone is a secondary pollutant generated principally by the photochemical reaction of nitric oxides and oxygen molecules in the atmosphere. It has detrimental effects at concentrations only three to four times higher than natural background levels [32]. Episodes of high O3 concentration occur in urbanized areas during periods of sunny anticyclonic weather in the summer months. O3 is a highly reactive gas, and a powerful oxidant. Epidemiological studies have shown chronic O3 exposure to be associated with the risk of death from respiratory causes [33], and the incidence and mortality of acute respiratory distress syndrome [34, 35]. Animal models and lung autopsy study have revealed the presence of chronic epithelial changes, including fibrosis, in subjects chronically exposed to high O3 concentrations [36, 37]. In its Integrated Science Assessment for Ozone, the United States Environmental Protection Agency estimated that there is a “causal relationship” and a “likely causal relationship” between short-term and long-term O3 exposure, respectively, and respiratory effects [38]. In IPF, the onset of an acute exacerbation has been shown to be associated with an increase in O3 exposure within the preceding 6 weeks; however, no association between long-term O3 exposure and IPF severity has ever been reported [13]. Nevertheless, long-term exposure to O3 has been shown to be positively associated with serum IL-4 levels in IPF patients, and tends to be associated with osteopontin levels, two mediators implicated in fibrosis [39].

The role of air pollution in autoimmune diseases has been studied essentially in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Particulate matter, such as diesel emission particles, is thought to induce the citrullination of lung proteins and the development of inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT), leading to the production of pathogenic anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) [40, 41]. iBALT hyperplasia and the activation of T-cells contained in pulmonary lymph nodes have been observed in animal models exposed to O3 [42, 43]. In SSc patients, exposure to O3 may trigger the development of iBALT-inducing pathogenic autoantibodies. Lung oxidant/antioxidant equilibrium is disturbed at high levels of O3 exposure, or in situations in which the lung lining fluid antioxidant power is compromised. The reaction of O3 with substrates present in the lung lining fluid compartment then generates secondary oxidation products and inflammation [32, 44]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have profibrogenic effects on fibroblasts and induce the release of profibrotic mediators, such as transforming growth factor-β 1 (TGF β 1) [45]. High levels of ROS, produced by the NADPH oxidase system, have been implicated in the pathophysiology of SSc [46–48]. Scleroderma fibroblasts cannot respond to oxidative stress and they mount an inadequate antioxidant response [46].

Borghini et al. reported that exposure to benzene was inversely correlated with DLCO and positively correlated with Rodnan skin score in SSc patients, whereas they found no association with PM10 exposure [21]. Benzene is mostly emitted during wood heating in human homes and in the transport sector and contribute to the formation of O3 through reactions involving nitrogen oxides (NOx) and solar radiation. Recently, Goobie et al. reported the association of PM2.5 exposure with lung function at baseline and mortality among patients with fibrotic ILDs [49]. Homogeneity of particulate matter exposure among our patients could have limited the evaluation of their impact on ILD severity and progression. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to evaluate the effect of O3 exposure in SSc patients.

Our work has several limitations. First, due to the rarity of SSc and the two-center design of the study, the number of patients included was small for the purpose to detect correlations. Most of the patients were living in the same region, limiting the variability of exposure. However, the use of the CHIMERE model increased the accuracy of exposure estimates, making it possible to detect smaller differences in exposure than would have been possible with the use of concentration data from air quality stations. A limitation inherent to the study design is the estimation of personal exposure at residential addresses, while exposures take place in multiple locations. Assuming that the error in the estimates is random, it would likely bias any association to zero, suggesting that the true magnitude of the effect may be greater than measured [50]. Mean annual O3 exposure were considered in our analysis, while the maximum O3 concentrations are reached during the daytime period in the summer months. Thus, the association of high O3 levels with respiratory effects may have been underestimated. Trends in the exposure to air pollutants over time may be a source of confounding. However, concentrations of particulate matters and NO2 have fallen over the years, whereas concentrations of O3 have increased in our study population, whereas the trend over the years regarding ILD in SSc patients may be assumed toward an earlier diagnosis through HRCT and a better outcome. Moreover, our results were consistent after adjustment for the year of ILD diagnosis. The study was retrospective. As a result, evaluation was not standardized and many PFT data were missing at 12 and 24 months, limiting evaluations of the effects of pollution on progression in our study. Inclusion period (2006–2019) limited follow-up time and the interpretation of the results of survival data. Most of the patients included were followed in the French referral center for SSc (Internal medicine department, Cochin Hospital) or the competence center for ILDs (Respiratory medicine department, Avicenne Hospital), and may therefore not represent a general SSc population. Last but not least, our study’s primary objective was to determine the association between SSc-associated ILD severity at diagnosis but did not consider the incidence of ILD in SSc patients. We did not study the effect of exposure to pollution on extrapulmonary SSc manifestations. Therefore, the role of air pollution exposure on ILD occurrence and other organ involvements in SSc patients remains to be determined.

Despite the retrospective nature of this study, HRCT characteristics at ILD diagnosis, reviewed by expert radiologists, were available for all the patients included, together with PFT parameters, allowing an accurate evaluation of ILD at diagnosis. Our study showed consistently significant associations with O3, however, supportive evidence from future studies in various geographic areas and animal models describing pathophysiological pathways implicated will be necessary to strengthen the arguments for causality.

In conclusion, this study is the first to assess the impact of air pollution on SSc-associated ILD. It reveals an association between O3 exposure and ILD severity at diagnosis and progression at 24 months, that is independent of the principal factors associated with disease severity and progression. The identification of this preventable risk factor could lead to avoidance measures, particularly during periods of high O3 levels in warm weather. A prospective larger-scale multicenter study with a standardized evaluation of progression and prolonged follow-up is required, to confirm our results and to assess the effect of air pollution exposure on SSc-associated ILD incidence and outcome.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Factors associated with the severity at diagnosis of systemic sclerosis associated interstitial lung disease. Table S2. Association of air pollution with the severity of SSc-associated ILD at diagnosis: two pollutant-models. Table S3. Functional changes during follow-up. Table S4. Factors associated with the evolution of systemic sclerosis associated interstitial lung disease. Table S5. Association of air pollution with categorial changes in pulmonary function test results at 24 months. Table S6. Association of air pollution with radiological progression at 24 months. Figure S1. Flow chart.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Augustin Colette for his help in pollution’s data management.

Abbreviations

- dcSSc

Diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis

- DLCO

Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC

Forced vital capacity

- HRCT

High-resolution computed tomography

- ILD

Interstitial lung disease

- IPF

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- lcSSc

Limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis

- NO2

Nitrogen dioxide

- NSIP

Non-specific interstitial pneumonia

- O3

Ozone

- OP

Organizing pneumonia

- PFT

Pulmonary function test

- PM2.5

Particulate matter of up to 2.5 µm in diameter

- PM10

Particulate matter of up to 10 µm in diameter

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SSc

Systemic sclerosis

- TLC

Total lung capacity

- UIP

Usual interstitial pneumonia

Author contributions

AR has full access to all the data for the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. AR, BC, RD, FC, BD, LM contributed to clinical data collection. FA contributed to pulmonary function test data collection. GC, STB, SJ, MPR and PYB performed the review of lung CT scans. IAM provided air pollution data for the patients’ geolocalized residential addresses. AR, LS, IAM, YU and HN contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation. AR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AR, LS, BC, LM, YU and HN contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work received financial support from the Groupe Français de Recherche sur la Sclérodermie (GFRS).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors (Y.U.) on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received Institutional Review Board approval (Comité Local d’Ethique pour la Recherche Clinique des HUPSSD, CLEA-2020-150) and the requirement for signed informed consent was waived according to French legislation (CNIL Reference methodology).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None of the authors has any conflict of interest related to this work to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lucile Sese, Guillaume Chassagnon and Benjamin Chaigne contributed equally to this work.

Isabella Annesi-Maesano, Luc Mouthon, Hilario Nunes and Yurdagül Uzunhan contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Anaïs Roeser, Email: anais.roeser@aphp.fr.

Lucile Sese, Email: lucile.sese@aphp.fr.

Guillaume Chassagnon, Email: guillaume.chassagnon@aphp.fr.

Benjamin Chaigne, Email: benjamin.chaigne@aphp.fr.

Bertrand Dunogue, Email: bertrand.dunogue@aphp.fr.

Stéphane Tran Ba, Email: stranba@gmail.com.

Salma Jebri, Email: salma.jebri1987@gmail.com.

Pierre-Yves Brillet, Email: pierre-yves.brillet@aphp.fr.

Marie Pierre Revel, Email: marie-pierre.revel@aphp.fr.

Frédérique Aubourg, Email: frederique.aubourg@aphp.fr.

Robin Dhote, Email: robin.dhote@aphp.fr.

Frédéric Caux, Email: frederic.caux@aphp.fr.

Isabella Annesi-Maesano, Email: isabella.annesi-maesano@inserm.fr.

Luc Mouthon, Email: luc.mouthon@aphp.fr.

Hilario Nunes, Email: hilario.nunes@aphp.fr.

Yurdagül Uzunhan, Email: yurdagul.uzunhan@aphp.fr.

References

- 1.Hoffmann-Vold AM, Fretheim H, Halse AK, Seip M, Bitter H, Wallenius M, et al. Tracking impact of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis in a complete nationwide cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(10):1258–1266. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0486OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):940–944. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffmann-Vold AM, Allanore Y, Alves M, Brunborg C, Airó P, Ananieva LP, et al. Progressive interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease in the EUSTAR database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;80(2):219–227. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goh NSL, Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Copley SJ, Maher TM, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(11):1248–1254. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-877OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volkmann ER, Tashkin DP, Sim M, Li N, Goldmuntz E, Keyes-Elstein L, et al. Short-term progression of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis predicts long-term survival in two independent clinical trial cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(1):122–130. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goh NS, Hoyles RK, Denton CP, Hansell DM, Renzoni EA, Maher TM, et al. Short-term pulmonary function trends are predictive of mortality in interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(8):1670–1678. doi: 10.1002/art.40130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winstone TA, Hague CJ, Soon J, Sulaiman N, Murphy D, Leipsic J, et al. Oesophageal diameter is associated with severity but not progression of systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Respirology. 2018;23(10):921–926. doi: 10.1111/resp.13309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greidinger EL, Flaherty KT, White B, Rosen A, Wigley FM, Wise RA. African-American race and antibodies to topoisomerase i are associated with increased severity of scleroderma lung disease. Chest. 1998;114(3):801–807. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.3.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scussel-Lonzetti L, Joyal F, Raynauld JP, Roussin A, Rich É, Goulet JR, et al. Predicting mortality in systemic sclerosis: analysis of a cohort of 309 French Canadian patients with emphasis on features at diagnosis as predictive factors for survival. Medicine. 2002;81(2):154–167. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conti S, Harari S, Caminati A, Zanobetti A, Schwartz JD, Bertazzi PA, et al. The association between air pollution and the incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Northern Italy. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(1):1700397. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00397-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shull JG, Pay MT, Lara Compte C, Olid M, Bermudo G, Portillo K, et al. Mapping IPF helps identify geographic regions at higher risk for disease development and potential triggers. Respirology. 2021;26(4):352–359. doi: 10.1111/resp.13973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johannson KA, Vittinghoff E, Morisset J, Wolters PJ, Noth EM, Balmes JR, et al. Air pollution exposure is associated with lower lung function, but not changes in lung function, in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2018;154(1):119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johannson KA, Vittinghoff E, Lee K, Balmes JR, Ji W, Kaplan GG, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis associated with air pollution exposure. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(4):1124–1131. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00122213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sesé L, Nunes H, Cottin V, Sanyal S, Didier M, Carton Z, et al. Role of atmospheric pollution on the natural history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2018;73(2):145–150. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-209967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dales R, Blanco-Vidal C, Cakmak S. The association between air pollution and hospitalization of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Chile: a daily time series analysis. Chest. 2020;158(2):630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tahara M, Fujino Y, Yamasaki K, Oda K, Kido T, Sakamoto N, et al. Exposure to PM2.5 is a risk factor for acute exacerbation of surgically diagnosed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a case–control study. Respir Res. 2021;22(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12931-021-01671-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winterbottom CJ, Shah RJ, Patterson KC, Kreider ME, Panettieri RA, Rivera-Lebron B, et al. Exposure to ambient particulate matter is associated with accelerated functional decline in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2018;153(5):1221–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon HY, Kim SY, Kim OJ, Song JW. Nitrogen dioxide increases the risk of mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(5):2001877. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01877-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aguilar PM, Carrera LG, Segura CC, Sánchez MIT, Peña MFV, Hernán GB, et al. Relationship between air pollution levels in Madrid and the natural history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: severity and mortality. J Int Med Res. 2021;49(7):3000605211029058. doi: 10.1177/03000605211029058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silman AJ, Howard Y, Hicklin AJ, Black C. Geographical clustering of scleroderma in South and West London. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1990;29(2):92–96. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/29.2.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borghini A, Poscia A, Bosello S, Teleman AA, Bocci M, Iodice L, et al. Environmental pollution by benzene and PM10 and clinical manifestations of systemic sclerosis: a correlation study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(11):1297. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(11):2737–2747. doi: 10.1002/art.38098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akira M, Inoue Y, Arai T, Okuma T, Kawata Y. Long-term follow-up high-resolution CT findings in non-specific interstitial pneumonia. Thorax. 2011;66(1):61–65. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.140574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, Richeldi L, Ryerson CJ, Lederer DJ, et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(5):e44–e68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silva CIS, Müller NL, Hansell DM, Lee KS, Nicholson AG, Wells AU. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: changes in pattern and distribution of disease over time. Radiology. 2008;247(1):251–259. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2471070369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, King TE, Lynch DA, Nicholson AG, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):733–748. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menut L, Bessagnet B, Khvorostyanov D, Beekmann M, Blond N, Colette A, et al. CHIMERE 2013: a model for regional atmospheric composition modelling. Geosci Model Dev. 2013;6(4):981–1028. doi: 10.5194/gmd-6-981-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khanna D, Mittoo S, Aggarwal R, Proudman SM, Dalbeth N, Matteson EL, et al. Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung diseases (CTD-ILD)—report from OMERACT CTD-ILD working group. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(11):2168–2171. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Thomson CC, Inoue Y, Johkoh T, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(9):e18–47. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Platenburg MGJP, van der Vis JJ, Kazemier KM, Grutters JC, van Moorsel CHM. The detrimental effect of quantity of smoking on survival in progressive fibrosing ILD. Respir Med. 2022;194:106760. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambient (outdoor) air pollution. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health. Accessed 1 Mar 2022.

- 32.Mudway IS, Kelly FJ. Ozone and the lung: a sensitive issue. Mol Aspects Med. 2000;21(1):1–48. doi: 10.1016/S0098-2997(00)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Pope CA, Ito K, Thurston G, Krewski D, et al. Long-term ozone exposure and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1085–1095. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware LB, Zhao Z, Koyama T, May AK, Matthay MA, Lurmann FW, et al. Long-term ozone exposure increases the risk of developing the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(10):1143–1150. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1418OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rush B, McDermid RC, Celi LA, Walley KR, Russell JA, Boyd JH. Association between chronic exposure to air pollution and mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Environ Pollut. 2017;224:352–356. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stockstill BL, Chang LY, Ménache MG, Mellick PW, Mercer RR, Crapo JD. Bronchiolarized metaplasia and interstitial fibrosis in rat lungs chronically exposed to high ambient levels of ozone. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1995;134(2):251–263. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherwin RP. Air pollution: the pathobiologic issues. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1991;29(3):385–400. doi: 10.3109/15563659109000365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.US EPA National Center for Environmental Assessment RTPN, Luben T. Integrated science assessment (ISA) for ozone and related photochemical oxidants (final report, Apr 2020). https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/isa/recordisplay.cfm?deid=348522. Accessed 27 Feb 2022.

- 39.Tomos I, Dimakopoulou K, Manali ED, Papiris SA, Karakatsani A. Long-term personal air pollution exposure and risk for acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Environ Health. 2021;20(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12940-021-00786-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rangel-Moreno J, Hartson L, Navarro C, Gaxiola M, Selman M, Randall TD. Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in patients with pulmonary complications of rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(12):3183–3194. doi: 10.1172/JCI28756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiramatsu K, Azuma A, Kudoh S, Desaki M, Takizawa H, Sugawara I. Inhalation of diesel exhaust for three months affects major cytokine expression and induces bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue formation in murine lungs. Exp Lung Res. 2003;29(8):607–622. doi: 10.1080/01902140390240140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pabst R, Miller LA, Schelegle E, Hyde DM. Organized lymphatic tissue (BALT) in lungs of rhesus monkeys after air pollutant exposure. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2020;303(11):2766–2773. doi: 10.1002/ar.24456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dziedzic D, Wright ES, Sargent NE. Pulmonary response to ozone: reaction of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue and lymph node lymphocytes in the rat. Environ Res. 1990;51(2):194–208. doi: 10.1016/S0013-9351(05)80089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen C, Arjomandi M, Balmes J, Tager I, Holland N. Effects of chronic and acute ozone exposure on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant capacity in healthy young adults. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(12):1732–1737. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bellocq A, Azoulay E, Marullo S, Flahault A, Fouqueray B, Philippe C, et al. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates increase transforming growth factor-β 1 release from human epithelial alveolar cells through two different mechanisms. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21(1):128–136. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.1.3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambo P, Baroni SS, Luchetti M, Paroncini P, Dusi S, Orlandini G, et al. Oxidative stress in scleroderma: maintenance of scleroderma fibroblast phenotype by the constitutive up-regulation of reactive oxygen species generation through the NADPH oxidase complex pathway. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(11):2653–2664. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200111)44:11<2653::AID-ART445>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Svegliati S, Cancello R, Sambo P, Luchetti M, Paroncini P, Orlandini G, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor and reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulate Ras protein levels in primary human fibroblasts via ERK1/2. Amplification of ROS and Ras in systemic sclerosis fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(43):36474–36482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Servettaz A, Guilpain P, Goulvestre C, Chéreau C, Hercend C, Nicco C, et al. Radical oxygen species production induced by advanced oxidation protein products predicts clinical evolution and response to treatment in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(9):1202–1209. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.067504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goobie GC, Carlsten C, Johannson KA, Khalil N, Marcoux V, Assayag D, et al. Association of particulate matter exposure with lung function and mortality among patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeger SL, Thomas D, Dominici F, Samet JM, Schwartz J, Dockery D, Cohen A. Exposure measurement error in time-series studies of air pollution: concepts and consequences. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(5):419–426. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Factors associated with the severity at diagnosis of systemic sclerosis associated interstitial lung disease. Table S2. Association of air pollution with the severity of SSc-associated ILD at diagnosis: two pollutant-models. Table S3. Functional changes during follow-up. Table S4. Factors associated with the evolution of systemic sclerosis associated interstitial lung disease. Table S5. Association of air pollution with categorial changes in pulmonary function test results at 24 months. Table S6. Association of air pollution with radiological progression at 24 months. Figure S1. Flow chart.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors (Y.U.) on reasonable request.