Highlights

-

•What can be learned about the healthcare access of undocumented workers? How can health equity be advanced through sensitivity to the process of precaritization and the precarities informing their lives?

-

•Thailand and Spain are the only countries in the world that offer the same healthcare access to undocumented migrants as citizens. Most European countries only offer emergency services: France, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland allow undocumented migrants to access similar services to citizens if they meet conditions (proof of identity; length of residence in the country). European cities such as Ghent, Frankfurt, and Dusseldorf, offer barrier-free healthcare. Throughout the USA, Federally Qualified Health Centers support care to the uninsured regardless of immigration status.

-

•In Canada, Ontario and Quebec, provide a base level of healthcare access to undocumented migrants, and a small number of stand-alone community-based clinics offer additional care and specialized services.

-

•To promote healthcare for undocumented migrants in Alberta, barrier-free access to vaccination, COVID-19 treatment, and proof of vaccinations are essential, but an equity lens to healthcare service— informed by analytic understanding and robust approach to precaritization as a social determinant, is most needed.

-

•

Introduction

COVID-19 has drawn attention to the various inequities embedded in our societies highlighting the necessity for governance and advocacy work that will advance health inclusion. In many countries, migrants have been disproportionately affected by direct and indirect effects of the pandemic—in the first instance from infection often due to their status as essential workers and/or crowded living conditions, and in the latter due to loss of livelihoods and reduced access to other health determinants. [Laundry, et al., 2021, Etowa & Hyman, 2021, Machado & Goldenberg, 2021, Spitzer, in press] The World Health Organization 1948 Constitution included the right to health for all migrants. In recent years, the 2017 World Health Assembly furthered this agenda by highlighting the contributions of migrants to host and natal countries and the critical importance of migrant health to the Sustainable Development Goals. [WHO 2017] In Canada, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms affirms that all persons, regardless of citizenship status, are entitled to “life, liberty, and security of person” and “the right to human dignity, respect, equality and justice.” [Alcaraz, et al., 2021, p. 9] These tenets underpin the call for pandemic healthcare including vaccination for all—encompassing the undocumented migrants.

The term undocumented refers to individuals who do not possess the state-sponsored authorization to reside or work in the confines of the nation-state. Although the exact number of undocumented migrants in Canada is difficult to ascertain, as of 2016 over 500,000 undocumented migrants lived in Ontario alone. Those numbers are thought to have increased in the intervening years. [Bains, 2021] Undocumented workers often enter a country legally, but may slip into and out of legal status as they navigate systems of border controls and employment authorizations. [Goldring & Landholt, 2013a, United Nations, 2015] Under conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic, the shuttering of businesses, government offices, and lockdowns, created more possibilities for migrant workers to become undocumented. As a result, there is slippage between the categories of temporary and undocumented migrant workers. Employers in the western Canadian province of Alberta are believed to be “among the most enthusiastic users of temporary foreign workers” in the country, [Barnetson & Foster, 2017, p. 27] suggesting that a considerable number of undocumented migrants may reside in the Province.

Our work is informed by the deployment of critical race theory, an eco-social framework, and migrant health equity as primary and reinforcing theoretical lenses-critical race, eco-social, and migrant health equity.. Critical race theory highlights the historically and politically constructed racialized inequalities that are embedded in and reinforced by socio-political systems. [Crenshaw, 2016] Eco-social theory examines how social environments, interacting with exposures, agency, and resistance, are embodied and configure the health and well-being of individuals and communities.[Krieger & Gruskin, 2001] Migrant health equity employs both lenses to situate migrant well-being within the skeins of neoliberal globalization and the unequal gendered division of labour that serves global capitalism. [Spitzer, 2022, Tuyisenge & Goldenberg, 2021] As it also advocates for the adoption of fairer social and economic policies that meaningfully address the unmet needs and rights of migrants and the undocumented, migrant health equity is highly aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals’ principle of leaving no one behind as well as public health's moral imperative of social justice. Migrant health equity, however, can only be wrought through sustained and meaningful disruption of upstream forces that currently engender social, economic, and gendered inequalities that contour access to social determinants of health and social location, which for undocumented migrant workers is characterized by their precarious lives. [Spitzer, 2022, Spitzer, 2020]

Anchored by these perspectives, we summarize evidence in support of health care for all, with a view towards promoting health equity for undocumented workers in Alberta. We ask: What can be learned about the healthcare access of undocumented workers? How can health equity be advanced through sensitivity to the process of precaritization and forms of precarities that inform undocumented migrants’ lives? We respond to these questions by first providing an overview of temporary foreign workers’ (TFWs) contributions to the Canadian labour market and economy as the context in which undocumented migrants are situated. Next, and using Alberta as an illustrative case, we contrast these gains to the barriers that undocumented workers face in accessing health determinants and healthcare services including vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. We then examine international policies and programs implemented to facilitate undocumented migrants’ pandemic health rights, as well as models of service delivery and policy found across Canada to ground our recommendations for action.

Methods

Working from a feminist methodological perspective that challenges the singular epistemic privilege according to Western bio-scientific knowledge, [Brooks, 2007] we produced this scoping review through a collaborative, robust, and multi-thematic process of environmental scanning. We included multiple viewpoints, particularly from people with lived expertise, to integrate diverse information and strengthen our evidentiary base. Given the emerging nature of our topic and recognizing that there is rich research beyond peer-reviewed publications, we also utilized both grey and peer-reviewed literature to promote inclusion and conversation of multiple knowledge sources.

Contributing to the call for literature review that goes beyond seeking and filling the gap, [Tynan & Bishop, 2023] we used a modified mini-delphi process—an iterative research and group facilitation technique, [Hasson et al., 2000] to start from our positionality and to tap on the team members’ public health perspectives. Through an online discussion, we generated an outline of topics to be covered. Utilizing an editable google document and spending a span of one week for a participatory thematic analysis, each team member then contributed to the review and reduction of the initial outline into key words and conceptual relationships. We followed this with a facilitated online meeting where we discussed and established consensus on the final search strings: (i) “temporary foreign workers” “economic contributions” “Alberta” and “Canada”; (ii) “policy” “healthcare” “undocumented” “uninsured” “immigrant” and “migrant”; (iii) “medically uninsured”, “migrants'', “immigrants”, “healthcare access”, “access to health services”, “migrant worker”, “uninsured”, “undocumented”, “illegal”, “barrier”; and “Alberta”; and (iv)“undocumented”, “migrants”, “healthcare access”, “refugee”, and “immigrants.

We searched a total of seven databases between March to May 2021. These included Scopus, PubMed, PAIS International, OVID, EMBASE, CINAHL, and EBSCO. We also conducted a general search of published and grey literature using Google Scholar and the University of Alberta Academic Search portals. We utilized “Connected Papers,” a visual search tool to identify policy related papers, and consulted governmental and policy websites to complement and verify our findings. Limiting our scan to an 11-year period (2010-2021), our search attempts generated a total of 443 publications that we subjected to initial screening. The reading, annotation, and cross referencing of these materials eventually led to the inclusion of 83 articles in our final analysis.

Results

Generating Precarity

From a political economic and critical social science perspective, precarity and precaritization are multi-dimensional constructs that characterize TFWs’ employment, lives, and, subsequently, health conditions. [Schierup, Ålund, and Likic-Brboric, 2015, Syed, 2020] Precarity is often articulated as the experience of limited job opportunity, reduced social protection, and induced income insecurity [Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities, 2019] and the resulting effects of indecent living conditions, growing social isolation, and constant mental stress. [Brown-McLaughlin, 2020] Precarity needs to be understood, however, as a condition driven by contextual factors beyond employment. Because while the narrow and traditional conceptualization of precarity often fails to account for the system and structural level creation of both ontological and labour conditions that deprive TFWs of predictability and stability, these attendant processes position migrant workers into existential and economic locations of risks and uncertainties. [Syed, 2020]

In Canada, the gendered, neoliberal and capitalist work and migration regimes, bolstered by the state's sustenance of societal, political, economic, and legal structures that overtly construct and reinforce categories of differences—status vs. non-status, citizen vs. non-citizen—are mechanisms for the distribution of power, privilege, and access to health and wellbeing. [Spitzer, 2022] As a case in point, under the auspices of the Canadian Temporary Foreign Workers’ Programs, migrant workers from the Global South are brought to the country to fill labour shortages via issuance of employer-specific work permits (ESWP). This restricts ESWP holders to particular employers and ensures that they “inhabit[s] social and political categories that carry ideological weight and institutional logic, which in turn generate specific administrative practices that subjugate them in Canada.” [Abboud, 2013; p.134] Being tied to a single employer leads them to a life of indentured labour because they are not free to circulate in the labour market. “[C]losed work permits, coupled with inadequate monitoring and enforcement of labour standards, create the conditions that allow unscrupulous employers and recruiters to abuse…(TFWs) with impunity. Closed work permits facilitate employer control and exploitation of workers including working excessive hours without payment for overtime, unpaid hours of work and often less than minimum wage pay.” [Migrante Alberta, 2016, para. 8] Closed work permits and the two-tiered process of permanent residency in Canada, wherein some TFWs may apply for permanent residency status, have become instrumentalities in forcing ESWP holders to be docile bodies as they are not only pushed into indentureship, but also impelled to be silent about their experiences of abuse due to their employers’ power to control their pathways to citizenship.[Torres, et al., 2012, Tungohan, 2018] As Brown-McLaughlin [Brown-McLaughlin, 2020] argues, Canada intentionally uses TFWs to create a pool of legally free or coerced labour by systematically denying participants’ access to citizenship. This in turn produces predominantly racialized non-citizens or denizens of foreigners with residency rights to work, but who are denied full citizen rights. TFWs are therefore deemed ‘good enough to work’, but not to stay in Canada because gate-keeping policies are well placed to keep TFWs out of spaces for citizenship rights.

As the non-citizenship status is a system induced social location, being undocumented is also a fluid condition that migrants are forced to move into and/or out of. Being undocumented embodies “the authorized and unauthorized forms of non-citizenship that are institutionally produced and [that] share a precarity rooted in the conditionality of presence and access” [GOLDRING & LANDOLT, 2013b]. Oftentimes undocumented migrants are ‘created’ when their work permits cannot be renewed leaving them with the option of either returning with few funds or continuing to earn for their families while running the risk of deportation. [Brown-McLaughlin, 2020] Given the precarity of their migration status and their lives in Canada, undocumented migrants try to minimize contact with authorities who represent the nation-state, including health services. Resultantly, despite their elevated risk of occupational injuries, stress, and noxious social and physical environmental exposures, [Alcaraz, et al., 2021, Burton-Jeangros, et al., 2020, Ridde, et al., 2020] they report a high number of unmet healthcare needs or a failure to obtain healthcare when needed—including health services for pregnancy and conditions requiring tertiary care.

Situating Undocumented Migrants in Canada

Primarily subsumed under the category of temporary foreign workers (TFWs), undocumented migrants are among the thousands of foreign-born Canadian residents who contribute to—and sustain—Canadian society and the Canadian economy, including those whose labours have been deemed essential during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, the literature suggests that TFWs benefit Canada in four important ways by: (1) Supplying human resources for different sectors and industries; (2) Providing essential services in the time of the pandemic; (3) Contributing quantifiable resources and other enabling mechanisms for Canada's economy; and (4) Enriching national and transboundary discourses on migration, citizenship, and development.

Undocumented Migrant's Health and Health Care in Alberta

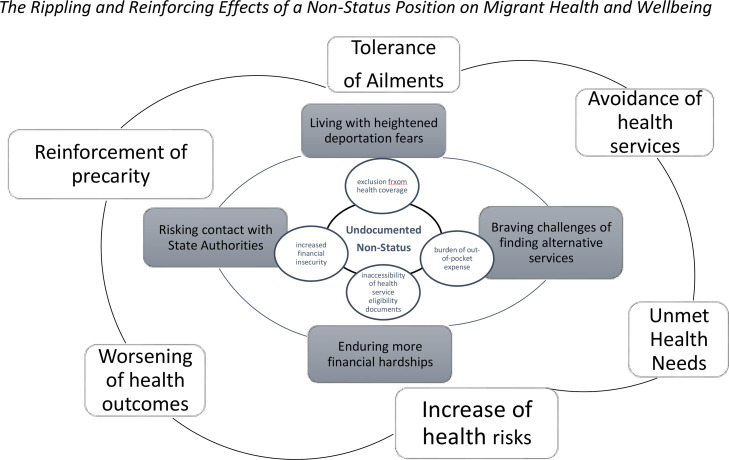

Undocumented migrants in Alberta are among those with the poorest health outcomes. [Foster & Luciano, 2020, Salami, et al., 2020] As Fig. 1 suggests, their social location as non-status individuals position them into multi-level and reinforcing risks and uncertainties that shape their healthcare seeking behaviors and consequently overall health and wellbeing.

Fig. 1.

The Rippling and Reinforcing Effects of a Non-Status Position on Migrant Health and Wellbeing

As elsewhere in the country, hospitals and emergency rooms in Alberta have the ethical responsibility to provide services to all patients regardless of their residency status and may be seen as facilitators of undocumented migrants’ health; however, many migrants without status remain afraid to seek health services as they do not possess a valid Alberta Healthcard and, as a result, are not covered by the publicly funded healthcare system. [Mattatall, 2017] This often leads to tolerance of minor ailments or outright avoidance of health services. When seeking treatment in most urgent situations, uninsured migrants face enormous out of pocket expenses, which they are unable to afford as they already struggle financially due to precarious employment conditions.

Policy barriers also pose additional threats to safe and continuous healthcare access for undocumented migrants. While there is no specific policy prohibiting access to healthcare for undocumented migrants, they are not eligible to apply for the Alberta Health Card. An extension of the Card for those who entered Canada legally but are waiting for their residency or work permits to be renewed, is also limited to a few months. [Gov. Alberta, 2021] Afterwards, they are on their own. Many migrants with precarious status have tried to challenge their healthcare coverage in court arguing that access to healthcare is a basic human right covered under Canadian law, but to date their fights have been unsuccessful. [Chen, 2017]

Additionally, undocumented migrants consistently live in fear of deportation as a consequence of being reported to authorities by healthcare providers they visit. [Government of Alberta 2021] The most common reason for undocumented migrants to seek medical care is to give birth. In Calgary, a continuous increase in deliveries by non-Canadians including uninsured migrants has been observed over the past decade. [Chen, 2017] These pregnant people often do not have another choice and must go to a hospital to deliver their babies, but afterwards they face bills of thousands of dollars that they have to pay back over many months, putting them in even greater financial straits. Importantly, in many cases these individuals do not receive any prenatal care, which may enhance their risk for various birth complications and poor maternal health outcomes.

Some healthcare practitioners and clinics do not charge non-status migrants as they feel uncomfortable billing their patients once they learn that they are uninsured. Only a small number of undocumented migrants, however, is able to locate health care providers who will not levy fees; thus, the majority still ends up being charged for services. [Mattatall, 2017, Chen, 2017] Moreover, when uninsured migrants receive a prescription from their healthcare provider, they immediately face another challenge as most pharmacies request a valid Alberta Health Card to dispense medications. [Mattatall, 2017]

COVID-19 and Migrant Workers in Alberta

COVID-19 also exposed and widened the jarring healthcare disparities that migrant workers experience in the province. [Benjamen, et al., 2021] For instance, the COVID-19 outbreak in the Cargill meat-packing plant in High River, Alberta, was linked to 25% of the province's cases in October 2020. Most of the workers in this plant are TFWs [Green, 2020] who are said to take on 3D jobs—difficult, dirty, dangerous, just to survive [Mattatall, 2017]. Migrant workers in Alberta also reported heightened physical and mental health concerns as they confront COVID-19 related issues. These include language barriers limiting understanding of public health guidelines, loss of employment and income, and problems obtaining documentation. [Baum, et al., 2020]

In the early days of the pandemic, when social distancing was the primary measure implemented by the Alberta health authorities to stop the spread of the virus, many migrant workers in precarious employment were unable to comply. [Baum, et al., 2020, Bragg, 2020] Amongst meat packing and food processing workers for instance, carpooling, close living conditions, and cramped working conditions were inherent to their jobs; neither did they have the option to work from home because they were not eligible to receive employment insurance. For some, missing days of work, even if exhibiting symptoms, would mean losing work, which would mean losing income and, for those who possessed it, legal status in Canada. [Dryden, 2021] Overall, as federal benefits and health supports were widely unavailable to migrant workers, it became clear as to how exploitation and fear has continued to plague migrant workers’ rights to health during the pandemic. It is also not difficult to imagine how adverse the condition was for their undocumented counterparts.

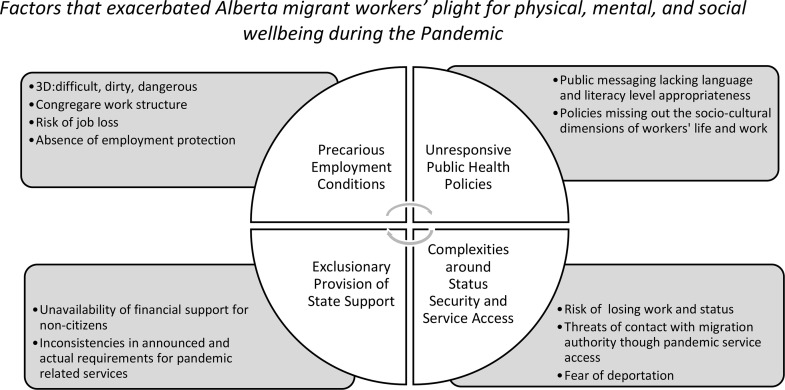

In the case of COVID-19 vaccinations, many workers reported language barriers, inaccessibility to clinics and a mere lack of knowledge that vaccines were being offered—signaling the ineffectiveness of generic public health messaging. [Baum, et al., 2020, Beck, et al., 2019] Health messages were not tailored for many TFWs who did not speak English well, were hesitant to access the healthcare system, or were lacking access to the Internet. Additionally, in the case that workers knew of vaccinations, clear messaging on how to access these services without an Alberta Health Card was inconsistent and identified as a deterrent. [Baum, et al., 2020, Beck, et al., 2019] Although some messaging stated a valid Health Card would not be requested upon arrival, this was not always the case when one arrived at their appointment. Signages at clinics would, in fact, often indicate where people needed to present their Alberta Health Cards. For an undocumented worker, the possibility of being asked for a valid health card was enough to deter one from seeking vaccination, despite the presence of such vaccination services and assurances of vaccination providers. Lastly, fear of deportation and the vaccine database being available to the Canadian Border Services, was also a reason to avoid vaccinations. [Bains, 2021, Somos, 2021] Overall, a lack of transparency and adequate messaging represented a failure of public health efforts to protect this population. In the face of a pandemic, where healthcare is of utmost importance, undocumented migrants faced major stressors that had severe impacts on their physical, mental and social health (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Factors that exacerbated Alberta migrant workers’ plight for physical, mental, and social wellbeing during the Pandemic

A global glimpse of Healthcare and Pandemic Service Access for Undocumented Migrants

Undocumented Migrants’ Health Care Access: A Pan-Canadian picture

Many countries do not have federal or state policies addressing healthcare for undocumented immigrants; however, local governments and organizations working towards providing accessible health services for those without state-sanctioned healthcare may be found. For example, the US government funds Federally Qualified Health Centers across the country that support care to the uninsured regardless of immigration status. [Beck, et al., 2019] Major cities in the European Union have created localized systems that grant healthcare access to undocumented immigrants without enforcement interactions. In Ghent, Belgium, undocumented immigrants are given access to a medical card that is valid for three months and does not require the provision of an address. [PICUM, 2017] In Germany, Frankfurt and Dusseldorf employ local governments and organizations to fund the provision of uninsured healthcare for undocumented migrants, bypassing their need to register under the national German health system and face potential exposure to immigration authorities. [Bahar Özvarış, et al., 2020] At the federal level, both Italy and Spain provide universal access to healthcare for undocumented immigrants through government programs that support all levels of healthcare. [National Resource Center for Refugees, 2021] In Spain, Madrid strengthens the federal system of universal healthcare at the local level through facilitating an ongoing campaign which educates undocumented migrants about their rights to access the public health system in that country. The campaign also reminds practitioners of their duty to care for patients irrespective of status and provides identity cards for undocumented residents to ensure they have access to public services offered by the city, including healthcare. [Bahar Özvarış, et al., 2020]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments across the world started to increase their healthcare access to undocumented migrants due to the nature of this public health pandemic; however, some initiatives have had untoward impacts. Pop-up vaccine clinics have circulated throughout the USA, enabling easier access to testing and vaccination services for the undocumented. These pop-up clinics work in conjunction with a variety of institutions, including local organizations, religious institutions, local government committees, and cultural services. [National Resource Center for Refugees, 2021] In Turkey, refugees and undocumented immigrants were granted access to COVID-19 testing and treatment. This response was led by the Turkish government with support from local authorities, local and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and community organizations. While this initiative provided COVID-19 related health services to undocumented migrants, the service created was hampered by a number of issues including language and information obstacles, which prevented migrants from accessing the specific services they required. [Bahar Özvarış, et al., 2020] In light of intersectional barriers related to the COVID-19 pandemic, Portugal granted undocumented migrants who have applied for permanent residency, citizenship rights, enabling full access to the nation's healthcare services as a method of decreasing risks associated with public health. Undocumented migrants are given access to health services while awaiting the outcome of their applications. [Cotovio, 2020]

Undocumented Migrants’ Health Care Access: A Pan-Canadian picture

Across Canada, only two of ten provinces, Ontario and Quebec, provide a base level of healthcare access to undocumented immigrants. Ontario has 74 community health centres and an additional 22 health centres in Toronto that provide medical services to undocumented immigrants. [Association of Ontario Health Centres, 2016] Furthermore, the FCJ Refugee Centre in the City of York and a medical clinic in Scarborough have also been providing free access to healthcare. [FCJ Refugee Centre, 2012, Kennedy, 2021] In Montreal, Quebec, the community-based perinatal health and social centre Maison Bleue, operated by the non-governmental organization Medicins du Monde, offers medical treatment and maternal and child health services to marginalized populations. [Aubé, et al., 2019, CBC News, 2017] Maison Bleue also offers services for uninsured migrants with the exception of prenatal care and follow-through. Operating on donations and grants, the clinic cannot address complex needs of its target population; resultantly, unmet healthcare needs, primarily due to financial barriers remain. [Salami, et al., 2020] Unfortunately, while we only found these few examples within Canada, many of these centres also do not have the capacity nor the resources to take on a large number of patients. This highlights the need for more support from the government for these organizations and for greater overall access to healthcare for undocumented immigrants.

The Public Health Agency of Canada stated that COVID-19 vaccines would be available to all regardless of insurance and migration status. However, the identification procedures were determined by provincial and territorial governments, and as of March 2021, only Ontario and British Columbia announced that undocumented and migrant workers would not be required to present health cards to access vaccines. [Bains, 2021] Many vaccination clinics in Toronto, Montréal, Edmonton, and Calgary did not check for an individual's health card, although name and date of birth were required. [FCJ Refugee Centre 2012, TCRI, 2020] Although legally only a first name, date of birth, and contact information (email address or phone number) were required and could be affirmed without documentary evidence, some sites requested confirmation of address. The Government of Quebec also designated medical clinics that provided free access for the diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19. [Steps to Justice, 2021] Local health authorities and community organizations in partnership with individual physicians and advocacy groups also launched ‘barrier and surveillance free’ vaccination clinics in community and workplace settings. [Poncana, 2021, Tait & Graney, 2021]

The issuance of proof of vaccination certificates has added another layer of complication for undocumented migrants. In Ontario, an Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) card is needed to obtain a receipt via the Province's vaccination portal. Those who do not possess OHIP could procure a receipt through their local public health unit. Venues that ask for vaccination receipts require accompanying identification that verifies name and date of birth. Although some may not be aware of the regulations, these documents do not need to be government-issued nor include photo ID. [Steps to Justice, 2021]

Conclusion

COVID-19 has exposed and exacerbated the health, social, and economic inequities embedded in Canada's political-economic structures. Despite undocumented migrants’ contributions to Canadian society, especially feeding and keeping Canada safe in this unprecedented time of a global health emergency, they have not been afforded the same access to critical preventative healthcare and services as other Canadian residents. Financial barriers, fear of deportation, logistical problems, and lack of information about accessible barrier-free migrant-responsive services that do not require documentation of residency status or provincial health, are all obstacles for care. Even where undocumented migrants are able to obtain free healthcare services, they are often limited in their capacity to address complex conditions and care needs.

As a result, undocumented migrants report a high rate of unmet healthcare needs, which may lead to more severe conditions, higher rates of disability, and, potentially, death. Health and wellbeing and access to healthcare, however, cannot be extracted from issues of social location, working conditions, income, migration status, and familial separation. Moreover, undocumented workers may be unable to lodge complaints about poor working and living conditions; some may be challenged to reach out to migrant advocacy groups who are able to channel their voices to policymakers and the public.

The plight of TFWs and undocumented migrants echo the long existing calls and demands for the revision of Canada's labour and economic policies as well its overall stance and participation in global processes of migration and development. TFWs have been—and continue to be integral to the nation-building of this country and to the functioning of specific sectors and industries despite the structural constraints that render TFWS as indentured labour and technically Canadians without passports. [Burton-Jeangros, et al., 2020] The temporary nature of their stays in Canada and the contingencies inherent in their work visas make them vulnerable to shifts in their documented status — a process that we illustrated in this paper as induced and systemic precaritization.

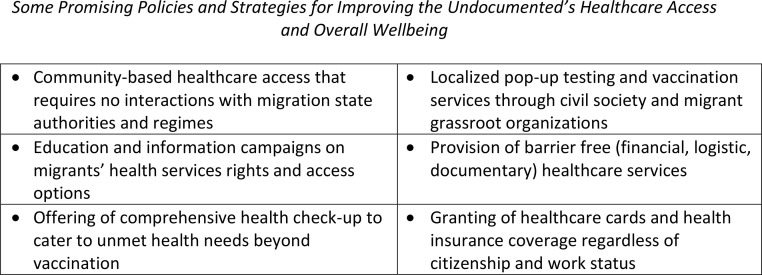

Models of better healthcare access for undocumented immigrants exist both around the world and in Canada (see Fig. 3). The Province of Alberta has the responsibility to follow these examples and provide healthcare access including vaccination services to people irrespective of their status. Barriers to accessing healthcare, which include fear of being deported, delayed access to health services, and healthcare costs, can be mitigated using the specific strategies outlined above in creating programs and services for undocumented migrants to access health services.

Fig. 3.

Some Promising Policies and Strategies for Improving the Undocumented's Healthcare Access and Overall Wellbeing

Healthcare for all requires attention not only on migrant workers’ work, life and health conditions, but also on the role of economic and migration models and how they facilitate enslaved, cheapened and extractive wage labour systems that breed conditions for poor migrant health and healthcare access. Overall, applying an equity lens to pandemic healthcare necessitates an analytic understanding and robust approach to precaritization as a social determinant of health and wellbeing. In the context of the World Health Organization's founding documents, the Sustainable Development Goals, and Canada's own Charter of Rights and Freedom, we offer the following recommendations to promote healthcare for undocumented migrants in Alberta, based on the findings in this report:

-

1

Eliminate waiting periods for provincial insurance coverage and provide universal healthcare coverage for all residents of Canada regardless of status;

-

2

Expand barrier-free access to health care services including access to vaccination, COVID-19 treatment, and proof of vaccinations

-

3

Support community-based migrant-responsive healthcare; and

-

4

Grant temporary foreign workers permanent residency status upon arrival.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Marian C. Sanchez, Email: mcsanche@ualberta.ca.

Deborah Nyarko, Email: nyarko@ualberta.ca.

Jenna Mulji, Email: jmulji@ualberta.ca.

Anja Džunić, Email: dzunic@ualberta.ca.

Monica Surti, Email: surti@ualberta.ca.

Avneet Mangat, Email: amangat@ualberta.ca.

Dikshya Mainali, Email: dikshya@ualberta.ca.

Denise L. Spitzer, Email: spitzer@ualberta.ca.

References

- Abboud R. University of Toronto; 2013. The Social Organization of the lives of ‘semi-skilled’ international migrant workers in Alberta: Political rationalities, administrative logic and actual behaviours.https://hdl.handle.net/1807/35759 Doctoral Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaraz N, Ferrer I, Abes JG, Lorenzetti L. Hiding for Survival: Highlighting the Lived Experiences of Precarity and Labour Abuse Among Filipino Non-status Migrants in Canada. J Hum Rights Soc Work. 2021;6(4):256–267. doi: 10.1007/s41134-021-00169-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of Ontario Health Centres , CHC Fact Sheet. 2016 .Accessed July 14 2022. https://www.aohc.org/chcfact-sheet.

- Aubé T, Pisanu S, Merry L. La Maison Bleue: Strengthening resilience among migrant mothers living in Montreal, Canada. PLoS One. 2019;14(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220107. Published 2019 Jul 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahar Özvarış Ş, Kayı İ, Mardin D, et al. COVID-19 barriers and response strategies for refugees and undocumented migrants in Turkey. J Migr Health. 2020;1-2 doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2020.100012. Published 2020 Dec 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains C. The Globe and Mail; 2021. Undocumented workers hesitant to get vaccines, fear deportation: Advocates.https://login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/undocumented-workers-hesitant-get-vaccines-fear/docview/2505605554/se-2?accountid=14474 March 27,. Accessed June 29, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Baum K, Tait C, Grant T. The Globe and Mail; 2020. How Cargill became the site of Canada's largest single outbreak of COVID-19.https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-how-cargill-became-the-site-of-canadas-largest-single-outbreak-of/ May 3,. Accessed June 29, 2022. . [Google Scholar]

- Beck TL, Le TK, Henry-Okafor Q, Shah MK. Medical Care for Undocumented Immigrants: National and International Issues. Physician Assist Clin. 2019;4(1):33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cpha.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamen J, Girard V, Jamani S, et al. Access to Refugee and Migrant Mental Health Care Services during the First Six Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Canadian Refugee Clinician Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5266. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105266. Published 2021 May 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragg B. The Globe and Mail; 2020. Opinion: Alberta's COVID-19 crisis is a migrant-worker crisis, too.https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-albertas-covid-19-crisis-is-a-migrant-worker-crisis-too/ May 1,. Accessed June 29, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks A. In: Feminist Research Practice: A Primer. Hesse-Biber S, Leavy P, editors. Sage Publications; 2007. Feminist Standpoint Epistemology: Building Knowledge and Empowerment Through Women's Lived Experience. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-McLaughlin S. Temporary foreign work, precarious migrant labour, and advocacy in Canada: A critical exploratory case study.Masters Thesis, University of Alberta, 2020. 10.7939/r3-706z-q121. [DOI]

- Burton-Jeangros C, Duvoisin A, Lachat S, Consoli L, Fakhoury J, Jackson Y. The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic and the Lockdown on the Health and Living Conditions of Undocumented Migrants and Migrants Undergoing Legal Status Regularization. Front Public Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.596887. Published 2020 Dec 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CBC News. New clinic opens in Montreal for migrants with no health insurance. June 13, 2017 . Accessed June 29, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/montreal-clinic-uninsured-migrants-1.4159476.

- Chen B. The future of precarious status migrants' right to healthcare in Canada. Alberta Law Rev. 2017;54:649–663. doi: 10.29173/alr778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cotovio V. CNN; 2020. Portugal gives migrants full citizenship rights during coronavirus outbreak.https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/30/europe/portugal-migrants-citizenship-rights-coronavirus-intl/index.html March 30,. Accessed June 29, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. In: Framing Intersectionality: Debates on a Multi-Faceted Concept in Gender Studies. Lutz H, Vivar M, Supik L, editors. Routledge Press; 2016. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of anti-discrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and anti-racist politics. [Google Scholar]

- Dryden J. CBC News; 2021. Migrant farm workers lack access to vaccines - advocates say that hints at a larger problem.https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/alberta-migrant-farmers-vanesa-ortiz-syed-hussan-calgary-1.6028840 May 16,. Accessed June 29, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Etowa J, Hyman I. Unpacking the health and social consequences of COVID-19 through a race, migration and gender lens. Can J Public Health. 2021;112(1):8–11. doi: 10.17269/s41997-020-00456-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FCJ Refugee Centre, Primary healthcare clinic. 2012 . Accessed June 29, 2022. http://www.fcjrefugeecentre.org/ourprograms/settlement-programs/.

- Foster J, Barneston B. Who's on secondary?: The impact of temporary foreign workers on Alberta construction employment patterns. J. Can. Labour Stud. 2017;80(1):27–53. doi: 10.1353/llt.2017.0042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J, Luciano M. In the shadows: Living and working without status in Alberta. https://www.parklandinstitute.ca/in_the_shadows . April 29, 2020. Accessed June 2022.

- Goldring L, Landholt P. In: Producing and Negotiating Citizenship: Precarious Legal Status in Canada. Goldring L, Landholt P, editors. University of Toronto Press; 2013. The Social Production of Non-Citizenship: The Consequences of Intersecting Trajectories of Precarious Legal Status and Precarious Work; pp. 154–174. [Google Scholar]

- GOLDRING L., LANDOLT P. In: Producing and Negotiating Non-Citizenship: Precarious Legal Status in Canada. GOLDRING L., LANDOLT P., editors. 2013. The Conditionality of Legal Status and Rights: Conceptualizing Precarious Non-citizenship in Canada; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Alberta, Healthcare coverage for temporary residents. 2021. Accessed June 29, 2022. https://www.alberta.ca/ahcip-temporary-residents.aspx.

- Green K. CVT News; 2020. This virus was not made by us': Filipino employees say they face discrimination after Cargill COVID-19 outbreak.https://calgary.ctvnews.ca/this-virus-was-not-made-by-us-filipino-employees-say-they-face-discrimination-after-cargill-covid-19-outbreak-1.4914137 April 27,. Accessed June 29, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy B. Toronto Star; 2021. ‘We're going to keep doing this’: Scarborough clinic offering COVID-19 vaccine to undocumented workers.https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2021/03/26/were-going-to-keep-doing-this-scarborough-clinic-offering-covid-19-vaccine-to-undocumented-workers.html March 26,. Accessed 29 June 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Gruskin S. Frameworks matter: ecosocial and health and human rights perspectives on disparities in women's health–the case of tuberculosis. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972) 2001;56(4):137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry V, Semsar-Kazerooni K, Tjong J, et al. The systemized exploitation of temporary migrant agricultural workers in Canada: Exacerbation of health vulnerabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic and recommendations for the future. J Migr Health. 2021;3 doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100035. Published 2021 Mar 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado S, Goldenberg S. Sharpening our public health lens: advancing im/migrant health equity during COVID-19 and beyond. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01399-1. Published 2021 Feb 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattatall FM. Uninsured Maternity Patients in Calgary: Local Trends and Survey of Health Care Workers. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39(11):1015–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migrante Alberta. 2016. Briefing for TFW Review.https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HUMA/Brief/BR8374497/br-external/Migrante%20Alberta-e.pdf Accessed June 29, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- National Resource Center for Refugees . University of Minnesota; 2021. Immigrants, and Migrants (NRC-RIM). Pop-up COVID-19 vaccine sites.https://nrcrim.org/pop-covid-19-vaccine-sites 2022. Accessed June 29, 2022. Accessed June 29, [Google Scholar]

- PICUM. Cities of rights: ensuring health care for undocumented residents. April 2017 . Accessed June 30, 2022. https://picum.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/CityOfRights_Health_EN.pdf.

- Poncana M. The Pigeon; 2021. Marginalized communities in Toronto are taking vaccinations into their own hands.https://the-pigeon.ca/2021/06/04/marginalized-communities-toronto-vaccines/ June 4,. Accessed June 29, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ridde V, Aho J, Ndao EM, et al. Unmet healthcare needs among migrants without medical insurance in Montreal, Canada. Glob Public Health. 2020;15(11):1603–1616. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1771396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salami B, Mason A, Salma J, et al. Access to Healthcare for Immigrant Children in Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9):3320. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093320. Published 2020 May 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schierup C, Ålund A, Likić-Brborić B. Migration, Precarization and the Democratic Deficit in Global Governance. Int Migr. 2015;53:50–63. doi: 10.1111/imig.12171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Somos C. CTV News; 2021. Migrants, undocumented workers fear getting COVID-19 vaccine could lead to deportation.https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/migrants-undocumented-workers-fear-getting-covid-19-vaccine-could-lead-to-deportation-1.5375993 April 6,. Accessed June 29, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer DL. In: Globalizing Gender, Gendering Globalization. Çalışkan C, editor. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2020. Precarious Lives, Fertile Resistance: Migrant Domestic Workers, Gender, Citizenship, and Well-Being; pp. 142–157. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer DL. In: Migration and Health. Galea S, Ettman C, Zaman M, editors. University of Chicago Press; 2022. Intersectionality: From Migrant Health Care to Migrant Health Equity; pp. 186–193. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer D. COVID-19 and the Intersections of Gender, Migration Status, Work, and Place. In McAuliffe M, Bauloz C, eds. Research Handbook on Migration, Gender and COVID-19.London: Elgar; in press.

- Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities. Precarious work: understanding the changing nature of work in Canada. 2019. Accessed June 28, 2022. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/HUMA/Reports/RP10553151/humarp19/humarp19-e.pdf.

- Steps to Justice. I don't have status in Canada or a health card. Can I get a COVID-19 vaccine or proof of vaccine? October 26, 2021 . Accessed June 29, 2022. https://stepstojustice.ca/questions/covid-19/i-dont-have-status-in-canada-or-a-health-card-can-i-get-a-covid-19-vaccine-or-proof-of-vaccine/.

- Syed I. York University; 2020. Theorizing precarization and racialization as social determinants of health: a case study investigating work in long-term residential care. Doctoral Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Tait C, Graney E. The Globe and Mail; 2021. Majority of meat-packing plant workers have been vaccinated against COVID-19.https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/alberta/article-majority-of-alberta-meat-packing-workers-have-been-vaccinated/ May 13,. Accessed June 29, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- TCRI, Table de concertation des organismes au service des personnes réfugiées et immigrantes, Covid-19 immigration status and access to healthcare. 2020 . Accessed May 30. 2021. https://www.doctorsoftheworld.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Messages-de-diffusion-ANGVersion-6.pdf.

- Torres S, Spitzer D L, Hughes K., Oxman-Martinez J, Hanley J. In: Legislated inequality: temporary foreign migrants in Canada. Lenard P., Straehle C., editors. McGIll- Queen's University Press; 2012. From temporary worker to resident: The LCP and its impact through an intersectional lens; pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Tungohan E. Temporary foreign workers in Canada: reconstructing ‘belonging'and remaking ‘citizenship. Soc. Leg. Stud. 2018;27(2):236–252. doi: 10.1177/0964663917746483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tuyisenge G, Goldenberg SM. COVID-19, structural racism, and migrant health in Canada. Lancet. 2021;397(10275):650–652. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00215-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tynan L, Bishop M. Decolonizing the Literature Review: A Relational Approach. Qualitative Inquiry. 2023;29(3–4):498–508. doi: 10.1177/10778004221101594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . UN; New York: 2015. Behind Closed Doors: Protecting and Promoting the Human Rights of Migrant Domestic Workers in an Irregular Situation. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2017. Promoting the Health of Refugees and Migrants. Draft Framework of Priorities and Guiding Principles to Promote the Health of Refugees and Migrants. [Google Scholar]