Abstract

The microbiome is known to provide benefits to hosts, including extension of immune function. Amphibians are a powerful immunological model for examining mucosal defenses because of an accessible epithelial mucosome throughout their developmental trajectory, their responsiveness to experimental treatments, and direct interactions with emerging infectious pathogens. We review amphibian skin mucus components and describe the adaptive microbiome as a novel process of disease resilience where competitive microbial interactions couple with host immune responses to select for functions beneficial to the host. We demonstrate microbiome diversity, specificity of function, and mechanisms for memory characteristic of an adaptive immune response. At a time when industrialization has been linked to losses in microbiota important for host health, applications of microbial therapies such as probiotics may contribute to immunotherapeutics and to conservation efforts for species currently threatened by emerging diseases.

Keywords: antimicrobial peptides, chytridiomycosis, disease ecology, homeostasis, microbiota, resilience, stress physiology, symbiosis

1. Defining the Adaptive Microbiome Hypothesis

Adaptive immunity is characterized as specific to an antigen, protective of the host, and remembered such that future exposures result in more rapid responses (Ferro et al., 2019). Specificity requires a diverse repertoire for antigen recognition. Protection of the host requires neutralizing or eliminating a pathogen and preventing host damage. Memory requires a mechanism to repeat a response at an accelerated rate. Immune systems of bacteria, plants, and invertebrates incorporate these characteristics without T and B lymphocyte receptors or antibodies. This includes the CRISPR-CAS antiviral immunity of bacteria (Nussenzweig and Marraffini, 2022), the diverse Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) in plants (Han 2019), diverse mechanisms for immune memory in invertebrates including endoreplication, genomic incorporation of viral elements for RNA interference response amplification, epigenetics (Lanz-Mendoza and Contreras-Garduno, 2022) and the Variable Lymphocyte Repeat (VLR)-based immunity in the jawless hagfish and lampreys (Boehm et al., 2012). Indeed, innate immunity across the tree of life can respond specifically, be protective, and show innate immune memory (priming or training) via epigenetic changes, chromatin remodeling, transcriptional shifts, cell-cell and systemic communication, as well as transgenerational or vertical transmission of immune defenses (Gourbal et al., 2019). Thus, the typical adaptive immune mechanisms of somatic generation of antigen receptors, clonal expansion of lymphocytes, and production of memory cells that are unique to animals (Flajnik, 2023) represent a subset of the adaptive strategies utilized across the tree of life for immune defense.

The microbiome is a diverse set of cells producing mucosal and humoral factors that interact with host immunity and behavior (Table 1, Suppl. Table S1). In the amphibian skin, the microbiome includes hundreds of bacteria (Table 2), a conservative estimate ranging from 69 to 645 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) on average in wild amphibian populations (Kueneman et al., 2022), but depending on the sequencing and bioinformatics strategy the estimate may be in the thousands of OTUs per individual (Hu et al. 2022, Hughey et al. 2022), consistent with complex microbiomes found across vertebrates (Woodhams et al. 2020). Kearns et al. (2017) also described a diverse composition of skin fungi on amphibians, and other micro-eukaryotes are often present (Kueneman et al., 2016). These microbes, with dynamic population abundances and transcriptional output lead to a complex metabolome that can differ even among similar bacterial communities (Medina et al., 2017) and provide pathogen-specific host defenses. Indeed, the function of bacterial secondary metabolites in anti-pathogen defense is well-studied in pursuit of probiotic applications for disease management (Harris et al., 2009; Bletz et al., 2013; Mueller and Sachs, 2015; Woodhams et al., 2015, 2016; Rebollar et al., 2016; McKenzie et al., 2018). Thus, pathogen-specificity and protective function may be supplied by the microbiome.

Table 1. Examples of mucosome components of microbial or host origin ranging in size.

See Supplemental Table S1 for components of the skin mucosome specific to amphibian species commonly used in research.

| Mucosome compounds | Molecular Weight (g/mol, or Da) |

|---|---|

| galactose | 180 |

| tetrodotoxin (TTX) | 319 |

| violacein | 343 |

| corticosterone | 346 |

| temporin A | 1,397 |

| bacteriocin (class 1) | 1,500 |

| ranatuerin 2P | 3,003 |

| BA-lysozyme | 15,000 |

| bacteriocin (class 3) | 26,600 |

| frog integumentary mucins (FIM) | 116,000 |

| frog integumentary mucins (FIM) | 650,000 |

Table 2.

Common bacteria detected by culture or culture-independent targeted amplicon sequencing across amphibians from Kueneman et al. (2019) and Woodhams et al. (2015).

| Phylum* | Genus | Percent of isolates (N=7273) |

Percent reads (Total 42.5%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actinomycetota | Cellulomonas | 0.1 | 1.1 |

| Microbacterium | 11.2 | 0.8 | |

| Arthrobacter | 1.5 | 0.8 | |

| Rhodococcus | 1.7 | 0.6 | |

| Sanguibacter | 0.0 | 0.9 | |

| Bacteroidota | Bacteroides | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| Chryseobacterium | 4.2 | 3 | |

| Elizabethkingia | 0.3 | 0.6 | |

| Wautersiella | 0.1 | 0.5 | |

| Flavobacterium | 1.4 | 1 | |

| Pedobacter | 0.9 | 0.7 | |

| Sphingobacterium | 0.7 | 1.1 | |

| Pseudomonadota (Alphaproteobacteria) | Methylobacterium | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| Agrobacterium | 0.7 | 0.5 | |

| Rhodobacter | 0.2 | 0.6 | |

| Sphingomonas | 2.3 | 0.9 | |

| Pseudomonadota (Betaproteobacteria) | Pigmentiphaga | 0.0 | 1.3 |

| Methylibium | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| Rhodoferax | 0.1 | 0.7 | |

| Janthinobacterium | 0.7 | 0.5 | |

| Methylotenera | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| Pseudomonadota (Gammaproteobacteria) | Klebsiella | 0.1 | 3.7 |

| Pantoea | 0.1 | 0.7 | |

| Acinetobacter | 3.8 | 8.1 | |

| Pseudomonas | 12.9 | 10.2 | |

| Stenotrophomonas | 3.3 | 1.3 | |

| Verrucomicrobiota | Luteolibacter | 0.0 | 0.5 |

Taxonomy after Oren and Garrity (2021)

The third characteristic of an adaptive immune response is memory. According to the adaptive microbiome hypothesis, infection primes the microbial community by enrichment with anti-pathogen members, thus reducing the impact of secondary exposure. Like immune memory cells, or a seed bank, dormant or rare beneficial microbes may be able to quickly proliferate in response to pathogen exposure. Additionally, changes at the host population or host community assemblage scales provide a mechanism by which increases in prevalence allow the transmission of beneficial microbes that can in effect rescue the host upon repeat exposure (Pillai et al., 2017; Mueller et al., 2020). Memory can also be incorporated at a cellular scale due to selection within microbial populations for function and horizontal gene transfer. Thus, adaptation of the microbiome may occur with or without shifts in community composition.

Symbiosis can generate evolutionary novelty and innovation (Erwin, 2021), and may require regulation to maintain mutual benefit (Japp, 2010). Thus, in addition to evolving interactions within the microbiome, hosts have the behavioral, physiological, and immunological potential to change the selective environment that would facilitate directional changes in response to external stressors such as disease, or pathogen exposure (Foster et al., 2017). Following exposure to a stressor (e.g., a pathogen or changes in environmental conditions), the adaptive microbiome is reduced in terms of dispersion or variation among individual hosts, and it shifts to a state that is better suited to the conditions. While the stressor itself may be a change in environmental conditions or direct impacts by the pathogen, local conditions are also shifted by host responses (such as behavioral changes in habitat use, or production of mucosal antibodies, peptides, signaling molecules, and mucus composition - reviewed below) which result in a new selective environment. Similarly, ecological stressors that change the biotic community can alter microbial recruitment linkages (Greenspan et al., 2019, 2020). Holobiont theory suggests that under conditions of strong vertical transmission and rapid host generation, the holobiont can evolve (Theiss et al., 2016; van Vliet and Doebeli, 2019). Mathematical modeling suggests that holobiont evolution is also possible with environmental reservoirs and horizontal transmission (Roughgardern, 2020). Indeed, there are several alternative pathways for “remembered” microbes, including reliable transmission of functions (reviewed in Rosenberg and Rosenberg, 2021; Box 1).

Box 1. The Adaptive Microbiome and Nested Adaptive Cycles.

The Adaptive Microbiome Hypothesis is described as an individual host response to pathogen exposure characterized by a shift in microbial composition including reduced microbial diversity and increased anti-pathogen function. In addition, interhost differences or microbiome dispersion is reduced at the population level, compared to unexposed populations. Potential mechanisms for these effects are described in the text and Figure 1.

According to René Dubos (1959), “The states of health or disease are the expressions of the success or failure experienced by the organism in its efforts to respond adaptively to environmental challenges.” One of these adaptive responses to pathogen exposure involves the microbiome. In a map of disease space, this can be represented by hysteric or looping patterns of the host microbiome in relation to infection load (Torres et al., 2016).

When the adaptive microbiome is modeled with nested adaptive cycles or panarchy after Gunderson and Holling (2002) based on ecosystem studies, the interactions across spatial and temporal scales become apparent (Fig. B1). Quantitative measures of ecological resilience may be possible by measuring the ability of an adaptive cycle to persist (e.g., a host surviving infection) by absorbing the disturbance (e.g., homeostatic mechanisms in response to pathogen exposure; Fig. 3). Alternatively, the system will shift to an alternative state with new structure, functions, and relationships (Sundstrom and Allen, 2019). The quadrats of each lemniscate representing an adaptive cycle include processes of reorganization (α), growth (r), conservation (K), and release (Ω). Connections between scales include processes termed remember and revolt. Cross-scale memory for host microbiota includes transmission (merger of microbe and host) by recruitment or infection from host populations or from biotic communities, and immunological pressure (host immunity or microbiome) from hosts on populations of each microbe. At the individual host scale, the most resilient period is upon transmission (α) where reorganization of host immunity and microbiota is possible leading to growth (r, or immune activation coupled with competitive microbial interactions) toward a steady conservation state (K) that is more constrained and less resilient to additional perturbations (Pilippot et al., 2021). Disease is indicted in the release stage (Ω) at which point the system may collapse (a type of homeostatic overload or failure) affecting other scales particularly at the conservation stage (K), or the host may recover and move back to the reorganization stage (α). Mounting immunological pressure in the host growth stage (r) can result in reorganization (α) at lower scales such as microbial evolution and functional changes. Microbial evolution in response to disturbance is one mechanism underlying adaptive microbiomes, referred to in the text. Of note, in this panarchical model multiple microbes are nested within each host, and multiple hosts are nested within each community, while only one adaptive cycle is depicted at each scale for clarity in Figure B1.

The importance of cross-scale interactions is indicated by the examples of Bsal exposure in Eastern newts in studies by Malagon et al. (2020) and Carter et al. (2021), performed on adults at 14°C (Fig. B1). A host that is exposed to an aseptic pathogen dose produced in culture media may not respond in way that represents a naturally transmitted infection by contact between hosts even with an equivalent exposure dose because of the co-transmitted microbiota. If adapted in the host population for anti-pathogen function, the co-transmitted microbiota is likely to attenuate the infection, as shown in Figure B1. In this example, Eastern newts, Notophthalmus viridescens, in contact with an infected conspecific developed infection and showed survival curves similar to newts artificially dosed with high concentrations of Bsal zoospores. However, more newts survived the infection from contact in the study by Malagon et al. (2020) compared to the 100% lethal exposure to cultured zoospores in Carter et al. (2021). We note, however, that variation between studies is to be expected, and careful examination of adaptive microbiome transmission is needed.

There is a place in infectious disease research for controlled exposure experiments to examine emergent properties of host-microbe interactions. However, among the many factors that are excluded in a controlled laboratory setting is the metacommunity dynamic that potentially transforms the impact on disease outcome. Applying metacommunity theory to adaptive microbiomes reveals that co-transmission of pathogen and defensive microbiota may attenuate disease. Coinfections are common and widespread in wildlife including amphibians Herczeg et al., 2021), and transmission of microbes among hosts and between host and abiotic environments is continuous. Thus, for both directly and indirectly transmitted pathogens, co-transmission of microbiota along with the pathogen is an understudied feature of many disease systems.

Figure B1.

The adaptive microbiome hypothesis as represented by panarchy, or nested adaptive cycles after Gunderson and Holling (2002). In the top panel, adaptive cycles are represented at the scales of microbial population, individual amphibian host, and amphibian population or community. Connections across scale are indicated by processes of remember and revolt. Lower panels are representative figures of experiments in which newts were exposed to infectious Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal) zoospores obtained from sterile culture (lower right panel), or exposed to Bsal and co-transmitted adaptive microbiota from direct contact of naïve to infected newts (lower left panel). Upon infection, newts with undetermined co-transmission may have gained a head-start at adapting to infection by assembling a protective microbiota.

While many studies identify alterations in a microbiome when compared before and after a disturbance (Table 3; Palleja et al., 2018; Mickan et al., 2019; Sáenz et al., 2019), determining if the observed changes indicate a protective directional response or dysbiosis is difficult without time series samples and knowledge of disease or recovery outcomes. To help interpret microbial shifts in response to infection, Zaneveld et al. (2017) applied the Anna Karenina Principle (AKP) to host-associated microbiomes. Drawing on the opening line of Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina (1878), the idea that “happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way” is applied to microbiomes in dysbiosis - the community of healthy hosts will be similar, but the influence of disturbance will cause stochastic shifts in the stressed or diseased host (Madison, 2021). An AKP effect is primarily assessed through an increase in microbial community dispersion reflecting stochastic changes from an assumed similar ‘healthy’ microbiome. Indices including the normalized stochasticity ratio (NST; Ning et al., 2019) can also measure the relative roles of deterministic versus stochastic assembly processes. In a study of 27 human microbiome-associated diseases, AKP effects were detected in half and attributed to a dominant pathobiont. In cases demonstrating anti-AKP effects (decreased dispersion) or no effects, the community of microbes including rare species played a role (Ma, 2020).

Table 3.

Example systems with microbial dynamics subsequent to environmental stressors leading to evolutionary and ecological rescue of host populations or environmental microbiota with associated ecosystem functions.

| Environmental disturbance |

Microbial dynamics |

|---|---|

| Pathogen exposure | Increased competition and enrichment of anti-pathogen microbiome with or without host facilitation (Loudon et al., 2016) |

| Anthropogenic Disturbance (antibiotics, heavy-metal contamination, pesticides, fertilizer) | Increased antibiotic resistance in microbiome; proliferation of fungi, reduction of targeted pathogen; transfer of plasmids with resistance genes, duplication of resistance genes; enrichment of denitrifying bacteria; microbiome resilience and recovery after shift (Zipperer et al., 2016; Weeks et al., 2020; Gust et al., 2021; Rolli et al., 2021; Su et al. 2022) |

| Seasonality | Enrichment of dormancy pathways and microbes with wide thermal tolerance, persistence and recovery of dominant taxa in repeated freeze-thaw conditions (Sawicka et al., 2010; Lau and Lennon, 2012; Kueneman et al., 2019; Le Sage et al. 2021) |

| Circadian rhythm | Photoperiod modulates daily rhythms in skin immune expression and microbiome (Martinez-Bakker and Helm, 2015; Ellison et al., 2021a) |

| Tides and Flooding | Phylogenetic diversity enriched at low tides, increased halotolerance at high tide, and shifts in trophic interactions; soil inundation frequency impacts methane cycling microorganisms (Chauhan et al., 2009; Maietta et al., 2020; Martínez-Arias et al., 2022) |

| Migrations | Transmission changes with habitat, host physiology, immunity, density, or assemblage; functional resilience of microbiome after migration; relative increase Corynebacterium in migrating birds; evolution of microbial replication and migration rates depending on host or free-living status (Risely et al., 2018; Turjamen et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Obrochta et al., 2022; Becker et al., 2023) |

Cases that do not match the predictions of the AKP fall into two categories - termed ‘anti-AKP effects’ and ‘non-AKP’ effects - which demonstrate either less or the same level of dispersion as was seen in the ‘healthy’ microbiome (Zaneveld et al., 2017; Ma, 2020). From the perspective of the microbiome as a source of potential therapeutics or as an extension of host immune defense, the non-AKP and anti-AKP effects offer an opportunity because they indicate a directional response in the microbiome. This may indicate an adaptation when the microbial community shifts to an alternative state better suited to the environment or as a response to stress that helps restore homeostasis (key concepts defined in Table 4). The framework of ecological resilience provides further application of the adaptive microbiome hypothesis.

Table 4. Key concepts related to adaptive microbiomes, stress physiology, and disease resilience.

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Homeostasis | A complex process of maintaining physiological variables at or near a desired ‘set point’ (or reactive scope) through ‘controller’ systems monitoring stock levels of the regulated variables, and adjusting levels through flows maintained by ‘plant’ systems (Romero et al., 2009; Kotas and Medzhitov, 2015) |

| Homeostatic overload or failure | When physiological processes that mediate stress operate above the naturally fluctuating predictive homeostatic range, this can be considered Homeostatic Overload, and when operating below the predictive homeostatic range this is considered Homeostatic Failure. Neither conditions is conducive to organismal health (Romero et al., 2009) |

| Dysbiosis | A change in the composition of the host microbiota relative to the community found in healthy hosts, concurrent with a stressor or disease. Specifically, this can be seen as a reduction of beneficial or keystone species, a change in functional ability, an increase in pathogenic species, or a change in diversity (Peterson and Round, 2014; Vangay et al., 2015; Kriss et al., 2018; discussed in Hooks and O’Malley, 2017) |

| Microbiome | “the entire habitat, including the microorganisms (bacteria, archaea, lower and higher eurkaryotes, and viruses), their genomes (i.e., genes), and the surrounding environmental conditions” (Marchesi and Ravel, 2015) |

| Engineering resilience | the rate at which a community recovers to a pre-disturbance state (Pimm 1984) |

| Ecological resilience | the ability of the system “to absorb changes of state variables, driving variables, and parameters, and still persist” (Holling, 1973; Van Meerbeek et al., 2021) |

| Holobiont and hologenome | the host and its microbiota, including viruses, function as a single organism with a combined genome (Theiss et al., 2016; van Vliet and Doebeli, 2019; Zhou et al., 2022) |

| Immunological resilience | An individual’s ability to overcome disease through homeostasitic processes including inflammation (Medzhitov 2021) |

| Microbial community resilience | The ability of a microbial community to resist or recover from disturbance with regards to either taxonomic composition or functional capacity and be stable through time (Philippot et al., 2021) |

| Qualitative immune equilibrium | “a healthy immune system is always active and in a state of dynamic equilibrium between antagonistic types of response. This equilibrium is regulated both by the internal milieu and by the microbial environment” (Eberl, 2016) |

| Quantitative immune equilibrium | The evolutionary balance of protective and pathological immune responses toward a “Goldilocks” intermediate optimum cytokine response that balances the costs and benefits of parasitemia and immunopathology (Graham et al., 2022) |

| Evolutionary rescue | “The recovery and persistence of a population through natural selection acting on heritable variation” (Bell, 2017) |

| Ecological rescue | Changes in inter- and intra-specific interactions and/or community composition that reduce the negative impact of stressors and result in recovery of a population or community (Pillai et al., 2017; DiRenzo et al., 2018) |

1.1. Disease Resilience and the Adaptive Microbiome Hypothesis

Resilience to disease (Table 3) can occur at the scales of ecosystem, host population, individual host, microbial population or cell. At the ecosystem scale, resilience is a measure of maintenance or recovery of ecosystem function. At the host population scale, resilience is determined by epidemic fade-out. At the individual host scale, resilience is a state of health that includes pathogen resistance, tolerance, or recovery from infection. Hosts can develop resilience through development of an immunological response, and microbial populations are resilient when they evolve improved functions of defense or competitive advantages. Thus, conceptual models that transcend scale and the associated disciplinary boundaries are needed to synthesize and advance research on the biology of resilience. The adaptive microbiome hypothesis described here focuses on microbial dynamics on an individual scale following environmental stressors, including but not limited to disease, leading to evolutionary and ecological rescue of host populations or ecosystem functions associated with environmental microbiota (Table 3).

The emergence of the fungal disease chytridiomycosis is notorious for its historically unprecedented and broad ecological and taxonomic impact on amphibians (reviewed in: Lips et al., 2016; Woodhams et al., 2018; Zumbado-Ulate et al., 2022). While substantial research focuses on the hundreds of species impacted by this disease, a review found that 12% of species that had declined in population show signs of recovery (Scheele et al., 2019), and 32 species of Harlequin frogs thought to have gone extinct were rediscovered (Jaynes et al., 2022). While the pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) showed signs of increasing virulence through time as it spread through Central America (Phillips and Puschendorf, 2013), Voyles et al. (2018) found that virulence of the fungal pathogen was not changing in Panama, and mucosal skin defenses were higher post-disease emergence. These hopeful examples of disease resilience are a central focus of research because they may provide strategies for conservation, and a model for resilience to environmental disturbance.

Rather than dysbiosis or an imbalance of microbial communities in response to infection, adaptive responses of host microbiomes may be characterized by shifts in microbial community structure and diversity leading to a healthy defensive state (Jin Song et al., 2019). According to this hypothesis, upon recovery from infection, enriched microbial communities are primed for a second exposure, and like immune memory cells, are able to quickly proliferate or activate production of defensive compounds in response to pathogen exposure. Protective microbes may also be transmitted. This occurs in amphibian habitats (Kaiser et al., 2019; McGrath-Blaser et al., 2021), or vertically (Walke et al., 2011), or along with pathogens. Most disease studies artificially expose hosts to pathogen isolates and neglect co-infections common in amphibians (but see Stutz et al., 2017; Becker et al., 2019; reviewed in Herczeg et al., 2021). Historical contingency including immunological hysteresis and microbial assembly processes are known to induce, direct, or deplete immune defenses (Eberl et al., 2010; Johnson and Hoverman, 2012). Controlled studies may also neglect other natural contexts of infection, including the “memory” provided by the larger scales of host populations and communities that can be sources of microbial migration or transmission and considered in nested adaptive cycles (Box 1). The adaptive microbiome defense blurs the distinction between innate and adaptive immunity (Cooper, 2016) and helps explain the curiously high diversity of symbionts hosted by vertebrates with complex adaptive immunity (Dethlefsen et al., 2007; McFall-Ngai, 2007; Woodhams et al., 2020). This hypothesis underscores our reliance on microbial diversity for health and disease resilience.

At the population level, microbial rescue effects occur upon transmission through a population with beneficial changes in microbiome abundance, composition, or activity (Mueller et al., 2020). This is in opposition to dysbiosis, a condition also defined at the population level (Zanveld et al., 2018) in which host microbiomes shift stochastically in response to disease leading to morbidity (Fig. 1). At the level of an individual host, the adaptive microbiome hypothesis provides measurable indicators of disease resilience that may be predictive of population rescue or decline.

Figure 1. Characteristics of host microbiomes subsequent to pathogen exposure are conceptualized by the Adaptive Microbiome Hypothesis.

The hypothesis posits that the microbiome of hosts shifts in response to pathogen exposure with the following characteristics: beta-diversity shifts and microbiome dispersion decreases as the diversity of microbes on individual hosts decreases but taxa functioning in anti-pathogen competition increase (A). The microbiome of eight individual hosts is shown changing through time (circles on day 0 and squares on day 5 changing upon pathogen exposure), with alternative states depicted at day 20 post-exposure (panel C). Stability of the microbial rescue effect may depend on continued selection pressure from pathogen exposure. Clearance of infection may lead to microbiome resilience and host recovery (B), or tolerance of infection leading to microbial rescue of the host population (C). Disease is thought to lead to Anna Karenina Principle (AKP) effects (C) in which increased dispersion and dysbiosis results from homeostatic overload, or the threshold beyond which the holobiont can no longer adapt. An alternative to the indicated trajectories is a depauperate initial microbial diversity that leads to homeostatic failure, such that the microbiome is unable to mediate the stress of infection (see Bletz et al., 2018; Greenspan et al., 2022).

1.2. Measuring the adaptive microbiome with metrics of disease resilience

Typically, measures of disease resilience are retrospective in the sense that the intensity of infection (an amount of disturbance) that can be absorbed or withstood while maintaining host function or homeostasis (Holling 1973) can be measured upon pathogen exposure. This may be equivalent to resistance (Justus 2007) to infection, or tolerance of infection (Medzhitov et al., 2012). This absorption of stress is termed “ecological resilience” (Table 4) and is similarly described as the threshold of disturbance needed to shift the host to an alternative stable state (Scheffer et al., 2001). Alternative definitions of resilience (for example that used in the field of engineering, or “engineering resilience”; Table 4) are also retrospective including the rate at which a microbiome can return to its initial state after a disturbance (Pimm 1984), or degree of return. Others have defined resilience measurements in different ways in terms of function or adaptive cycles (Sundstrom and Allen, 2019; Philippot et al., 2021; Van MeerBeek et al., 2021). These definitions require time-series measures before and after disturbance as illustrated in Figure 1.

The microbiome has been used as a prospective measure of disease resilience in amphibians, and the concept of herd immunity was invoked to indicate a population protected by a threshold proportion of individuals that hosted microbes with anti-pathogen function (Woodhams et al., 2007b; Bletz et al., 2017). Given that anti-pathogen function may also be present in biotic communities and transmitted to hosts, this concept could be extended to community immunity by expanding the boundaries of an immunological individual to encompass the ecological population or biotic community.

At the scale of microbial population, the Pollution Induced Tolerance Concept (PITC) offers a perspective for disease ecology at the level of microbial genetics and/or community composition (Tlili et al., 2016). After a selection phase in which structural changes in a microbial community develop upon exposure to a pollutant, microbial communities are more tolerant to the pollutant due to adaptation or shifts in community composition, rather than acclimatization of populations by phenotypic plasticity. This is the result of loss of sensitive microbes and dominance of tolerant microbes and can be quantified as effective concentration (ECX), the dose of a pollutant needed to obtain a certain response or microbiome structural change. For example, when applied to a pathogen the EC50 could be defined as the pathogen dose needed to inhibit growth of a microbial community in culture by 50%, and comparing a pathogen-exposed and pathogen-naïve microbiome provides a measure of tolerance. Gust et al. (2021) found that phylogenetic groups of bacteria that tolerated chemical exposure increased in the microbiomes of larval Northern leopard frogs, Rana pipiens, along with immune transcriptional changes in a chemical dose-dependent manner. Changes in microbiome function with minimal structural changes are possible (Medina et al., 2017), and may indicate intraspecific selection leading to changes in the metabolome.

Indeed, hosts in polluted environments may have microbiomes that include genes involved with detoxification of heavy metals, and prevalence of these genes may increase along pollution gradients. Hernández-Gómez et al. (2020) found that rather than specific responses to trematode infection (a natural stressor) and sulfadimethoxine exposure (an anthropogenic stressor), larval skin microbiomes responded with similar changes, perhaps indicating a generalized stress response. It is unknown whether this response leads to anti-pathogen phenotypes or adaptations, or to what extent this represents dysbiosis. Northern leopard frogs are a widespread model species for examining agricultural pollutants as well as impacts of parasites and pathogens on the microbiome. Hayes et al. (2006) suggest that pesticides can have sublethal effects including endocrine disruption and immune suppression. The examples above indicate leopard frogs are a suitable model system for measuring adaptive microbiomes, thus testing for pathogen-induced tolerance of cultures may be informative.

The adaptive microbiome hypothesis posits that diversity of symbiotic microbiota provides the baseline for assembly of an anti-pathogen microbiome that develops upon pathogen exposure or infection. Indeed, Chen et al. (2022) showed that future Bd infection probability in five amphibian species was predicted by the richness of bacteria with antifungal properties, but not overall bacterial richness. Thus, measures of anti-pathogen genes in the microbiome, or predictive measures of anti-pathogen function of the microbiome based on targeted amplicon sequencing (Kueneman et al., 2016), can be used to quantify resilience potential or “latent resilience”. Similarly, invasion ecology predicts higher resistance to invasion of new species into species-rich assemblages that are more likely to contain competitors and predators, in functionally diverse assemblages, or in assemblages with species that facilitate invasion resistance (Hodgson et al., 2002; Renault et al., 2022). Escape from natural enemies, or enemy-release, may be more common when a pathogen invades a novel or low diversity assemblage (Colautti et al., 2004). Indeed, amphibians in experimental habitats providing a high diversity of skin microbiota were more resistant to ranavirus infection (Harrison et al., 2019). However, invasion need not destabilize an assemblage, and merger of microbe with host does not always lead to disease in an individual. The continuum of effects on hosts displayed by symbionts ranges from harm to benefit (Chen et al., 2018), and the balance, or adaptive benefit to the host, may be provided by particular microbial community constituents or host immune responses that are most likely to develop under conditions of high diversity and compartmentalization (Chomicki et al., 2020), and thus may be most vulnerable to disturbance under conditions of low diversity or high connectivity (Justus 2007; Pearson et al. 2021; Martins et al., 2022).

Co-occurrence networks may demonstrate increased structure in adaptive microbiomes indicative of competitive interactions (Rebollar et al., 2016), or increases in highly connected hub taxa with pathogen inhibitory properties (Jiménez et al., 2022). Critically, we would also expect a functional shift in the community in which we see selection for genes providing host benefit (Fig. 2). Compartmentalization of the microbiome with adaptive components enriched on body sites with higher infection load are possible (Bataille et al., 2016), as are whole-organism microbiome responses to stress-induced immunoregulation. As a result of this selection, impacts of the stressor should be reduced (e.g., reduced pathogen load).

Figure 2. Bacteria isolated from amphibians in Panama indicate shifts in microbiome function against the fungal pathogen (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, Bd) depending on host community disease state.

Upon recovery from the chytridiomycosis epizootic, amphibian assemblages in a Bd endemic state have higher proportions of individuals with at least one anti-Bd bacterium isolated from their skin (A; Campana X21 = 18.958, p < 0.0001; El Cope X21 = 7.289, p = 0.0069). Individuals with anti-Bd skin bacteria may be considered “protected” from Bd infection to some extent and show reduced infection prevalence (B; X 21 = 20.027, p < 0.0001). Populations of some species persisting after the epizootic show increased prevalence of the anti-Bd bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens (C; Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0232), a bacterium more common on the skin of tropical than on temperate amphibians (Kueneman et al., 2019). At the same time, these amphibians showed a significant reduction in prevalence of Serratia marcescens and Pseudomonas mosselii post-epidemic. Amphibians in rainforests of Panama exhibited culturable isolate diversity ranging from 3-21 unique isolates as indicated in this “living histogram” (D) showing morphologically distinct isolates stacked by individual amphibian. (Methods and data collection described in Woodhams et al., 2015; Voyles et al., 2018).

The adaptive microbiome is an alternate state that is maintained, at least in the short term while the selection pressure persists. Upon an additional exposure to the stressor, the microbial community will be stable as selection has already occurred for a community suited for that environment. Timing in the measurement of the microbiome to detect these features will be critical, as sampling in the transition between alternative stable states, or upon development of disease, may appear similar to the Anna Karenina Principle effects described as dysbiosis (Zaneveld et al., 2017).

1.3. Examples of Adaptive Microbiomes in Amphibian Disease Systems

Several recent studies offer empirical evidence for adaptive microbiomes in amphibians. In a host that is hyper-susceptible to chytridiomycosis, the mountain yellow-legged frog, Rana muscosa (Vredenburg et al., 2010), microbiota did not demonstrate engineering resilience, and a directional shift occurred with Bd infection such that some microbial taxa increased (Undibacterium and Weeksellaceae) while other taxa decreased in relative abundance (Jani et al., 2021). It would be informative to monitor microbiomes through time in individuals of this species that recover from infection with natural immunological mechanisms rather than fungicidal clearance of infection that is likely to disturb adaptive microbiome processes. Indeed, in a reanalysis of 99 microbiome samples from Jani and Briggs (2014) and Jani et al. (2017), Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog, Rana sierrae, populations experiencing epizootics with high prevalence and intensity of Bd infection had significantly lower skin bacterial richness and dispersion compared to populations in the enzootic disease phase, indicating a selective reduction of the microbiome, that in some species may lead to a skew toward protective microbes (Suppl. Table S2, Suppl. Fig. S1). In two studies testing cultured isolates from R. sierrae skin, the proportion of individuals with at least one anti-Bd isolate was greater than 80% in enzootic phase populations and significantly less in epizootic phase (Woodhams et al., 2007b; Lam et al., 2010) indicating that populations that persist to the enzootic stage either experienced selection for anti-Bd microbiota or fortuitously started with this beneficial composition. Similarly, Ellison et al. (2019) found that juvenile R. sierra with high Bd infection loads had significantly reduced skin bacterial richness and dispersion, and increased members of Burkholderiales (an order of Gram-negative bacteria that includes Undibacterium and Janthinobacterium) that when isolated and tested showed anti-Bd activity. Frogs with skin dominated by Burkhorderiales had low bacterial diversity that was stable through time (Ellison et al., 2021b). Indeed, Janthinobacterium lividum is a bacterium of special interest because after isolation from endangered mountain yellow-legged frogs in the field (Woodhams et al., 2007b) and application as a probiotic prior to Bd exposure, frogs could reduce infection loads and recover (Harris et al., 2009). Thus, field studies of naturally recovering populations, or lab studies of individuals that recover from infection may be an enriched source for microbiota adapted for mutualism with the host.

Besides Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs (Knapp et al., 2016) and amphibian species in Panama recovering from chytridiomycosis emergence (Fig. 2), other disease resilient species demonstrate trends consistent with an adaptive microbiome (Suppl. Table S2). For example, Bates et al. (2018) showed the same patterns of reduced skin bacterial richness and dispersion in epizootic phase larval and metamorphic midwife toads, Alytes obstetricans, along with an increase in predicted antifungal function (Suppl Fig. S3). Whether these changes represent an adaptive microbiome within the lifetime of individual hosts is not clear and requires time series experiments following the same individuals through infection progression and recovery, and examination of different pathogens or routes of exposure. In the American bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, a species with high infection tolerance (Peterson and McKenzie, 2014), skin microbiomes became more similar post-Bd infection (Chen et al., 2022). In contrast, in the highly susceptible boreal toad, Anaxyrus boreas (Carey et al., 2006), Bd exposure led to high infection loads and greater microbiome dispersion compared to healthy controls. Overall, hosts that were more susceptible to Bd increased in dispersion of microbiome through time (Chen et al., 2022). Like Hughey et al. (2022) and Martínez-Ugalde et al. (2022), we suggest that hosts with a history of disease emergence have microbiomes adapted to pathogen defense and may be less prone to disturbance by pathogen exposure. Whether or not a host became infected was predicted by the richness of bacteria that can function to inhibit Bd, while future infection intensity was predicted by the proportion of anti-Bd bacteria (Chen et al., 2022).

An initial examination suggests that populations with higher microbial diversity may be better protected (Suppl. Table S2). Becker et al. (2015) found that in the highly susceptible Panama golden frogs, Atelopus zeteki (Gass and Voyles, 2022), pre-established protective members were crucial for chytridiomycosis resistance. Similarly, in a study of American bullfrogs, R. catesbeiana, initial microbiome was correlated with growth rate as well as Bd infection intensity (Walke et al., 2015). Jani et al. (2017) surmise, “…much of the difference in microbiome composition between enzootic and epizootic populations may be in part a result, rather than a cause, of differences in Bd infection severity.” For example, in Panama where populations declined from west to east with disease emergence, Medina et al. (2017) found a decreasing trend in microbial diversity in Silverstoneia flotator populations. Population history of infection can impact the established microbiome (Campbell et al., 2018, 2019; Harrison et al., 2019) . Thus, the pathogen, type of exposure, population disease history, progression of infection, and timing of sampling may all be factors impacting adaptive microbiome dynamics. Environmental disturbances that impact the microbiome (Belden and Harris, 2007), including captive rearing (Kueneman et al., 2022), will also impact the adaptive potential of the microbiome, or latent resilience, to respond to disease emergence.

1.4. Adaptive microbiomes, homeostasis, and stress physiology

Disease dynamics are linked to stress physiology. For example, a stress response can help a host to recover from pathogen exposure, but chronic stress can also increase susceptibility to infection or reduce infection tolerance (Hall et al., 2020). Reactivity to stress can differ among individuals and may be developmentally regulated (Johnson et al., 2011; Gans and Coffman, 2021). Stress physiology can be described in the reactive scope model (Romero et al. 2009) in which physiological mediators are required to maintain or return the body to its homeostatic range following disturbance. The stress response can be considered an emergency life history stage and entails several acute phase responses (Fig. 3). The homeostatic range is physiologically mediated through behavior, the central nervous system, immune function, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal/interrenal axis, or cardiovascular function, and the adaptive microbiome.

Figure 3. The acute phase response or Reactive Homeostasis (Romero et al., 2009) to infection in amphibians involves several interrelated components that mediate homeostasis.

(A) Activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-interrenal axis stimulates an immediate corticosterone response, here accumulating in water rinses within the first hour of exposure to the fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal) as quantified from spotted salamanders, Ambystoma maculatum (data from Barnhart et al., 2020). Not shown is the activation of acute phase proteins including complement proteins from hepatocytes (reviewed in Jain et al., 2011; Rodriguez and Voyles, 2020). Catecholamines may also be stimulated by infection (Rollins-Smith, 2017). (B) Homeostatic circuit modified from Medzhitov (2021) inflammatory circuit model. The adaptive microbiome is hypothesized to be a novel homeostatic variable as well as an effector in the negative feedback loop regulating homeostasis. Tolerance, or adaptation of the microbiome to a new stable state that does not influence homeostatic variables is an alternative outcome. (C) Skin bacterial communities of Eastern red-spotted newts, Notophthalmus viridescens, depicted in a principal coordinates analysis showing samples colored by Bd infection load (white = 0 to red = 3.1x106 zoospores max), and points scaled by predicted anti-Bd function of the microbiome of each individual (data from Carter et al., 2021). Shifts in amphibian skin microbiome communities are a typical response to infection (Jani and Briggs, 2014), although the mechanism and timing of response remains under investigation. Baseline corticosterone, immune defenses, and microbiome can change seasonally and with circadian rythms in amphibians and in other vertebrates (Martinez-Bakker and Helm 2015; Le Sage et al., 2021). (D) Sickness behaviors in N. viridescens in response to B. salamandrivorans infection include inappetence, unusual shedding patterns (reviewed in Grogan et al., 2018) and body posturing perhaps functioning to dry the skin or inducing movement away from the water potentially inhabited by conspecifics (photo credit: Julia McCartney). (E) Sickness behaviors in N. viridescens may also include thermal regulation (behavioral fever, reviewed in Lopes et al., 2021).

Dysbiosis and loss of microbiome regulation, or “Anna Karenina effects” (Zaneveld et al., 2017), are anticipated beyond a stress threshold termed homeostatic overload (Table 4; Romero et al., 2009) at which point microbial communities can no longer adapt (moribundity in Fig. 1C; feedforward loop of Fig. 3B). The adaptive microbiome in response to host infection is a special case involving interactions with immunological responses. While microbial responses to pathogen exposure or other stressors may sometimes facilitate opportunistic infection or evolution of virulence (Radek et al., 2010; Stevens et al., 2021), immunological responses often support an adaptive microbiome (Ichinohe et al., 2011; Deines et al., 2017; Mergaert, 2018; Meisel et al., 2018; Varga et al., 2019). Indeed, co-option of stress mechanisms specific to infection stressors is a potential mode of evolutionary novelty (Love and Wagner, 2022).

1.5. Microbiomes and other mediators of stress

While there are many mediators of homeostasis, in amphibians, stress is often measured by the glucocorticoid hormone corticosterone. Corticosterone plays a role in the acute phase response to infection (Fig. 3A) and may redirect host resources toward sickness behaviors and immune system activation while providing negative feedback on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal/interrenal axis and inflammation (Sapolsky et al., 2000; Sears et al., 2011; Lopes et al., 2021; Medzhitov 2021). Increasingly, stress physiology has focused on comparison of baseline levels (e.g., among populations) and the response of corticosterone recovery through time (Narayan et al., 2019) indicating capacity to contribute to the acute phase response. Amphibian corticosterone is typically elevated in response to acute exposure to pathogens including chytrid fungi Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and B. salamandrivorans (Peterson et al., 2013; Gabor et al., 2015; Barnhart et al., 2020), ranavirus (Warne et al., 2011), and also in response to some probiotic bacterial applications (Kearns et al., 2017). The stress response may be suppressed by some helminth parasites, and Koprivnikar et al. (2019) found no response or decreased corticosteroid levels in larval amphibians experimentally exposed to trematodes. In field studies, the relationship between Bd infection status and baseline corticosterone is inconsistent and compared to uninfected frogs, infected frogs may show higher (Kinderman et al., 2012; Gabor et al., 2013), lower or no difference (Hammond et al., 2020) in baseline levels.

The interactions between corticosterone and other acute phase responses and the microbiome remain to be elucidated, and an adaptive microbiome is one mechanism among many integrated systems for maintaining homeostasis (Fig. 3). For example, differential blood cell counts can indicate stress (Davis and Maerz, 2023), and antimicrobial peptides from granular glands in the skin of northern leopard frogs, Rana pipiens, may also provide an index of stress because the quantity of secretion depends on the type of stimuli and intensity of the stressor (e.g., norepinephrine dose, feeding, predation; Suppl. Fig. S2; Pask et al., 2012). We hypothesize that the preparatory immunity functioning to increase skin defense peptides ahead of low temperature conditions conducive to fungal infection, and early spring breeding in Rana sphenocephala (LeSage et al., 2021), may have an underlying glucocorticoid component that synchronizes biological rythms and predictable risk (Sapolsky et al., 2000). Skin secretions impact the microbiome including pathogens (Woodhams et al., 2007a), and can function to inhibit or facilitate different microbes (Fig. 4). Similarly, Bd secretes compounds that impact the growth of some bacteria (growth facilitation or inhibition; Woodhams et al., 2014), and at the same time impacts the host immune function (Woodhams et al. 2012; Fites et al., 2013) such that both direct and indirect pathways may operate to impact the microbiome, thus reinforcing the selective strength on the microbiome during infection. There are a growing number of studies describing the crosstalk between the microbiome and host immune system, with each influencing the other. While most studied in the human digestive system (reviewed in: Reid et al., 2011; Belkaid and Hand, 2014; Belkaid and Harrison, 2017; Levy et al., 2017), the amphibian skin is a model system poised to uncover novel mechanisms of microbial and immune regulation (reviewed in Varga et al. 2019).

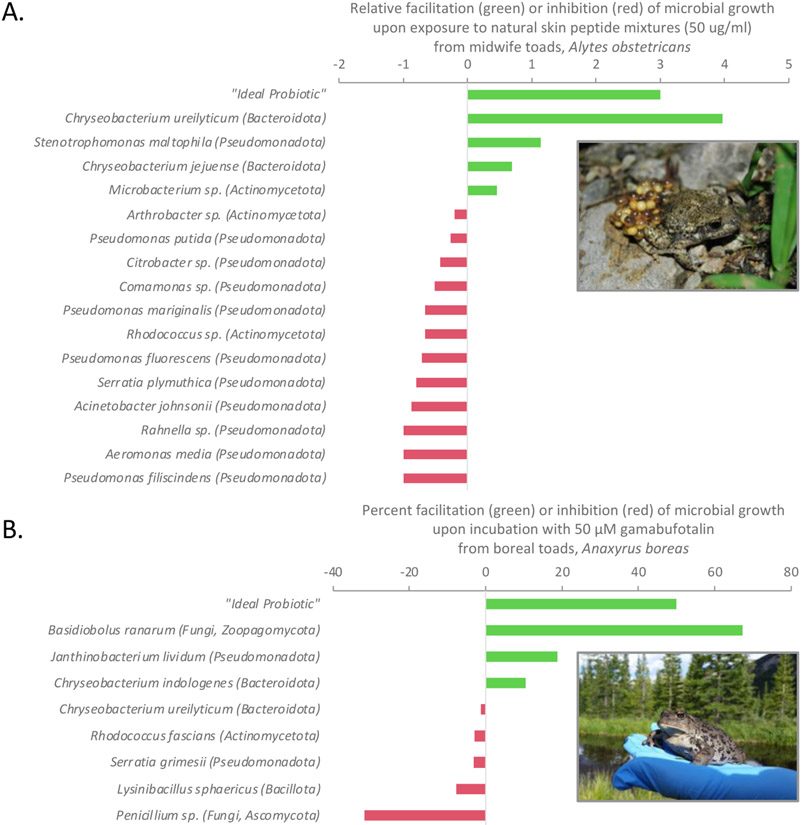

Figure 4. Compounds including antimicrobial peptides and bufadienolides secreted from skin granular glands into the mucosome may differentially regulate microbial growth on amphibian skin.

(A) Natural mixtures of antimicrobial peptides purified from skin secretions of midwife toads, Alytes obstetricans, from Switzerland have differential activity on growth of bacteria cultured from toad skin (Davis, 2013; parentheses indicate the phyla). Ideal probiotics, as conceptually modeled in the figure, for amphibian skin are not inhibited by antimicrobial skin defense peptides or other immune defenses, but rather are facilitated in growth or anti-pathogen function, and function over a range of host temperatures in ectotherms, and are not inhibited by the endogenous microbial community or by the target pathogen (Woodhams et al., 2014). In addition to the promicrobial function of some peptides (Woodhams et al., 2020b), (B) bufadienolides have microbe-specific activities that may help regulate the host microbiome. Shown are the bioactivities of gamabufatalin described from boreal toads, Anaxyrus boreas. Data from Barnhart et al. (2017), photo credit Timothy Korpita.

2. Interactions between amphibian skin microbiome and mucosal immunity

The skin functions as a barrier to the outside world socially, physically, chemically, and immunologically (reviewed in Chen et al., 2018; Swaney and Kalan, 2021; Woodley and Staub, 2021) . Amphibian skin also functions in osmoregulation, oxygen exchange, water balance, camouflage and behavioral signaling, and the production and secretion of mucus and a variety of small molecule toxins and immune factors (Table 1, Suppl. Table S1). Thus, the amphibian skin surface is a dynamic environment interacting with microbes and a model for microbial-vertebrate symbioses (Fig. 5). The regulation of symbiotic microbes may be a mechanism for resilience to disturbance. Here we provide a brief overview of amphibian skin anatomy before describing microbiome-immune interactions as regulatory mechanisms in the skin mucosome, the combined host and microbial components (see Schempp et al., 2009, Haslam et al., 2014; and Varga et al., 2019 for more detailed reviews on amphibian skin).

Figure 5. The microbiome interacts with multiple aspects of the amphibian skin landscape.

Microbes present on amphibian skin can interact with the host directly and indirectly. The immune system influences microbes present on the skin through avenues such as mucosal antibodies and pattern recognition receptors inducing innate immune responses (upper left panel). Other microbes present on the skin may influence the overall community composition through competitive and cooperative behaviors (upper right panel). Mucus is known to interact with microbes, acting as a food source and an anchor point for both microbes and bacteriophage (Barr et al., 2013), and mucus turnover rates (caused by shedding, ciliated cells in larvae, etc.) may help remove microbes attached to the matrix (lower left panel). Small molecules released by the host, such as antimicrobial peptides (shown: Subasinghagea et al. 2008; PBD ID: 2K10), can directly influence the survival and growth of microbes present on the skin, changing the community following granular gland release (lower right panel). Created with BioRender.com.

2.1. Amphibian skin composition

Amphibian skin, similar to mammalian skin, consists of the dermis and the epidermis. Generally, there are between 5 to 7 layers of cells in four strata of the epidermis, though the exact number differs among species (reviewed in Voyles et al., 2011; Haslam et al., 2013). The most basal layer of epidermis is the stratum germinativum (or stratum basale), which is largely made up of columnar epithelial cells that will flatten and become part of the stratum spinosum, the stratum granulosum, and eventually age into the outermost stratum corneum - the keratinized layer of dead cells in which the pathogen Bd colonizes (Haslam et al., 2013; Varga et al., 2019). The process of desquamation of the stratum corneum usually occurs in synchrony with shedding of a semi-continuous layer (Schempp et al., 2009). Periodic skin sloughing is balanced by keratinocyte proliferation in stratum germinativum. It should be noted that urodeles that are permanently aquatic will not develop a keratinized layer (Alibardi, 2009).

Molting, or skin sloughing, is a behavior that can have a benefit to the host by shedding infected tissue (Ohmer et al., 2015) perhaps similar to the role of intestinal mucus sloughing controlled by the enteric nervous system (Herath et al., 2020). The regular removal of the outermost skin layer may play a role in preventing pathogen establishment and reducing infection burden (Becker and Harris 2010; Meyer et al., 2012), and has been documented to influence the presence of cutaneous microbes on the skin of Australian green tree frogs, Litoria caerulea, and Marine toads, Rhinella marina (Meyer et al., 2012; Cramp et al., 2014).

The dermis consists of collagen and elastin fibers that are loosely packed (stratum spongiosum, below the stratum germinativum) or tightly packed in orthogonal patterns (stratum compactum) (Haslam et al., 2013). Some amphibians will have an additional layer consisting of calcium salts and polysaccharides bonding covalently with proteins interspersed with collagen fibers, that exists between epidermis and dermis, called the substantia amorpha (Toledo and Jared, 1992; Schwinger et al., 2001). This phenomenon appears to be restricted to terrestrial anurans, though it is not universally seen in species in this niche, and is thought to be related to preventing water loss or storage of calcium (Toledo and Jared, 1992). The skin is interspersed with immune cells, such as T and B cells and dendritic cells, and melanophores (Burgers and Van Oordt, 1962; Castell-Rodriguez et al., 1999; Pelli et al., 2007; Ramanayake et al., 2007; Schempp et al., 2009). The dermis also contains granular and/or mucus glands that differ in type and quantity across skin surfaces and among species or populations (Schempp et al., 2009; Haslam et al., 2013; Wanninger et al., 2018). Some species, for example the rough-skinned newt, Taricha granulosa, demonstrate seasonal, sexual, and life-history differences in the skin structure including the number and size of glands differing between aquatic and terrestrial stages (Gibson, 1969), or differences between body sites as in the Himalayan newt, Tylototriton verrucosus (Wannigan et al. 2018). Tubercles, when present, are the result of thickened epidermis over a dermal papilla (Gibson 1969). Parotoid glands and dorsolateral folds are also present in the skin of some species and contain concentrations of granular glands (McCallion, 1956). These variations in skin structure, and particularly glands, are likely to mediate the assemblage of microbiota.

Glands in amphibian skin are lined with secretory cells that produce a range of compounds (Suppl. Table S1), and largely consist of granular and mucus glands. Smooth muscle surrounds these glands and can contract to release these compounds onto the skin of the individual. Granular glands are the larger of the two and can contain a wide variety of biomolecules such as antimicrobial peptides (Mangoni and Casciaro, 2020) or sequestered toxic alkaloids (Daly et al., 1987; Toledo and Jared, 1995). These compounds perform a wide range of functions such as preventing infection or otherwise modulating the skin microbial community, predator deterrence, and defense (Prates et al., 2011; Bucciarelli et al., 2017). Mucus glands are smaller than granular glands in many species and primarily function to maintain a moist surface environment. In addition to releasing mucus onto the skin, amphibians will also secrete mucus into the intercellular space in the epidermis which helps to retain moisture by acting as a hydrophilic matrix, and aids in gas exchange (Parakkal and Matoltsy, 1964). Nerve endings are associated with both types of glands, but are only in direct contact with the secretory cells of granular glands (Sjöberg and Flock, 1976), which may imply different patterns of gland stimulation or sensitivity to certain stimulation.

Neuroendocrine immune interactions (Verburg-van Kemenade et al., 2017) are a critical component in mucosal defense, and amphibians may be model species for comparative neuroimmunology research (Kraus et al., 2021). For example, while acetylcholine induces glandular secretions in urodeles (Carter et al., 2021), norepinephrine induces secretions from granular glands in anurans (Conlon et al., 2007; Gammill et al., 2012; Suppl. Fig. S2). Indeed, stress can mediate immune function and stimulate skin peptide secretion through the autonomic nervous system, or mediate peptide expression via hypothalamic–pituitary–interrenal cortical axis acting through glucocorticoid release (Simmaco et al., 1997; but see Tatiersky et al., 2015). The role of stress hormones in permitting, suppressing, stimulating, or preparing the antimicrobial skin peptide defenses requires further experimental analysis (Sapolsky et al., 2000), although one recent study suggests a preparatory role of AMPs in regulating microbiota including the pathogen Bd (Le Sage et al., 2021). Studies demonstrate differential regulation of skin defense peptides and signaling molecules including Toll-like receptors upon infection with different pathogens (Xiao et al., 2014) and reciprocally, we found that skin peptide secretions differentially affect growth of bacteria (Fig. 4A; Woodhams et al. 2020b, Fletchas et al., 2019). Thus, skin defense peptides, including combinations that work synergistically (Zerweck et al., 2017), provide a narrow spectrum or targeted specificity that acts as a selective force on the microbiome. Not all amphibians produce antimicrobial skin peptides, and other chemical defense compounds as well as protein linked mucosal glycans or mucins (N- and O-linked oligosaccharides; Barbosa et al., 2022), can also provide selection on the microbiome (Barnhart et al. 2018, Fig. 4B), leading to the hypothesis that the microbiota provide the major system of defense in amphibian skin (Conlon et al., 2011).

As mentioned previously, various immune cells reside in the skin to respond early to potential threats to the host. In the epidermis, there are antigen-presenting Langerhans cells (Carrillo-Farga et al., 1990; Castell-Rodriguez et al., 1999), as well as B and T cells (Horton et al., 1992; Ramanayake et al., 2007). B and T cells can also be found in the dermis, along with mast cells (Pelli et al., 2007). The presence of these cells indicates that amphibians have the potential to respond with both the innate and adaptive immune system, but the location of these cells - below the stratum corneum - may mean that they are mainly responsive when the skin is broken. However, evidence of immunoglobulins in the skin mucus of African clawed frogs, Xenopus laevis, in response to infection with Bd indicates that the immune components in the skin are able to interact with microbes (Ramsey et al., 2010). Additionally, pattern recognition receptors have been found in amphibian genomes and direct interaction between epithelial cells and microbes is possible. However, much of the current literature is based in genomics and little is known about how common and how influential such interactions may be (reviewed in: Robert and Ohta, 2009; Grogan et al., 2018, 2020; Varga et al., 2019).

The skin of larval amphibians operates and protects the host differently than that of adults. Generally, the skin at the larval stage has fewer layers compared to an adult, but still consists of a dermis and epidermis (Takahama et al., 1992; Ishizuya-Oka, 1996; Schreiber and Brown, 2003). While keratinocytes are present in the outermost layers of larval skin, widespread keratinization of the epidermis is absent (Fox and Whitear, 1986; Breckenridge, 1987; Alibardi, 2001; Perrotta et al., 2012), and some of the keratins that are produced during the larval stage are unique to this life stage and are replaced with adult keratin following metamorphosis (Ellison et al., 1985; Suzuki et al., 2009). Vandebergh and Bossuyt (2022) report 23 type I keratin and 15 type II keratin genes in Western clawed frogs, Xenopus (Silurana) tropicalis, and show that the increase in keratins through metamorphosis is of a similar pattern to that observed in their phylogenetic analysis showing diversification during the evolutionary transition from water to land. While the characteristic widespread keratinization that is seen in adults does not happen to the larval epidermis, some keratin rich locations, such as the mouth, have been identified in tadpoles (Marantelli et al., 2004). We are not aware of studies comparing the microbial or pathogen utilization of different keratins, but this is one component that may account for shifts in microbiome through development (Piccinni et al., 2021).

Another characteristic component of larval skin is the presence of Leydig cells (LCs), which are found in urodeles and lost by the adult stage except in paedomorphic salamanders (Kelly, 1966; Ohmura and Wakahara, 1998; Perrotta et al., 2012), and mitochondria rich cells (MRCs), which are more abundant earlier in life and distinct from those found in adult skin, and present in anurans and urodeles (Restani and Pederzoli, 1997; Perrotta et al., 2012). The former is found in urodeles, and their function is not well understood. The literature notes that these cells are dense with granules and may be secreting mucus into the intercellular space below the outer epidermis (Kelly, 1966; Fox, 1986), though conflicting results suggest this may differ by species (Warburg and Lewison, 1977; Rosenberg et al., 1982; Fox, 1986; Breckenridge, 1987; Jarial and Wilkins, 2003; Brunelli et al., 2021). Additionally, LCs in the gills of the Italian newt, Lissotriton italicus, express aquaporin-3 where the general epidermis LCs do not, implying a role in water transport (Brunelli et al., 2022). MRCs are understood to primarily play a role in ion transport, as well as that of organic molecules, though the ability to move certain ions varies by species (Katz and Gabbay, 2010).

Some amphibians have observable glands in the dermis during the larval stage, but may not express skin defense peptides until just before metamorphosis (Delfino et al., 1998; Delfino et al., 2002; Angel et al., 2003; Terreni et al., 2003; Chammas et al., 2014; Stynoski and O’Connell, 2017). Antimicrobial peptides begin to develop during or after anuran metamorphosis and are actively secreted in some species with long-lived tadpole stages (Holden et al., 2015; Woodhams et al., 2016a). In larval Ambystoma tigrinum, for example, AMPs produced in granular glands can be collected (Sheafor et al., 2008), indicating functioning glands. Other species are not noted to have glands in the larval stage at all, though they are found in the adult life stage (Perrotta et al., 2012).

Some anuran larvae have ciliated cells that are lost as individuals approach metamorphosis (Nokhbatolfoghahai et al., 2006). These cells are thought to move mucus or the water around the host, as a mechanism to prevent infection or for chemosensing (Nokhbatolfoghahai et al., 2006). In place of mucus glands, mucus-containing goblet cells within the epidermis are often noted in early life stages (Kelly, 1966; Hayes et al., 2007; see also above discussion of LCs). While location and presence during the tadpole state can vary by species, a survey of 21 anuran tadpoles found that they were most concentrated around the eyes, nostrils, and on the tail (Nokhbatolfoghahai et al., 2006). In embryos, cilia may function to oxygenate the embryo or to facilitate microbiota including algae or microeukaryotes (Anslan et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2022), and anurans including Xenopus are model systems for studies of ciliated cells (Walentek and Quigley, 2017) and the development of ciliated epithelia (Collins et al., 2021).

The environment that the host maintains on the skin surface is a complex space for microbes to exist in and interact with. A multitude of components, both produced at a baseline level and in response to stress or disease (e.g., mucus, AMPs, antibodies), directly interact with and influence the physical microhabitat structure and activity of the microbial community. Thus, there is the clear potential to create new selective pressures and shape the symbiotic community as part of the host response to a stressor. In a review of the components of the skin mucosome of seven amphibians used as model research systems (Suppl. Table S1), we found that proteins (mucins, lysozymes, complement, and immunoglobulins; the larger and more complex components of the mucosome, Table 1) are underrepresented research topics, as are the virome and eukaryotic components of the microbiome including algae and the mycobiome. Below we give a brief overview of the microbiome and review studies relating to interactions with mucins and immunoglobulins. This does not negate the strong interactions between the microbiome and other mucosome components, particularly skin defense peptides which have been extensively reviewed elsewhere (e.g., Mergaert, 2018; Mangoni and Casciaro, 2020; Zeeuwen and Grice, 2021).

2.2. Amphibian skin microbiome

The epidemiological, ecological, and evolutionary forces that impact the assembly of the amphibian skin microbiome have been reviewed in Becker et al. (2023) and Kueneman et al. (2019). Depending on the biological scale of study, bioclimate and habitat may be the force driving the microbiome, or host community composition may influence microbial migration. Host population history of disease, host development stage, behavior, diet, or infection status can all impact the microbiome (reviewed in Becker et al., 2023). Of note, studies at larger spatial or temporal scales test for and report different drivers of the microbiome than smaller scale studies of individual hosts. We suggest that the microbiome be considered across scales to incorporate multiple mechanisms for achieving diversity, specificity, and memory in the adaptive microbiome (Box 1).

The amphibian skin microbiome includes not just bacteria (Kueneman et al., 2019), but also bacteriophages, viruses, and microeukaryotes including fungi (Kueneman et al., 2016; Kearns et al., 2017; Medina et al., 2019; Alexiev et al. 2021; Carter et al., 2021; Bates et al., 2022) and algae (Mentino et al., 2014; Anslan et al., 2021). We note a recent increase in studies examining the mycobiome, but a paucity of studies on the virome, or microeukaryotes such as algae. In terms of bacterial communities on amphibian skin, several meta-analyses provide information on culture-independent bacteria (Kueneman et al., 2019; Woodhams et al., 2020) and culturable bacteria (Woodhams et al., 2015). Dominant members are summarized in Table 2, and tested for correlation in terms of relative abundance of cultured or culture-independent genera (Fig. 6). We found that some members of the bacteriome are prevalent in populations but not abundant in targeted amplicon sequencing studies and no cultures exist for testing isolate function. These members include 5 out of the 27 genera with at least 0.5% relative abundance across the dataset: Sanguibacter (phylum Actinomycetota), Bacteroides (Bacteriodota), Pigmentiphaga and Methylotenera (Pseuomonadota), and Luteiobacter (Verrucomirobiota). These bacteria should be targeted for future culture. The wart-like Verrucomicrobiota is of particular interest as no member of this phylum has been cultured from amphibians, yet it is a core member with 100% prevalence in red-backed salamander hosts, Plethodon cinereus (Loudon et al. 2013), and 100% prevalence in Eastern red-spotted newts, Notophthalmmus viridescens (Walke et al., 2015). Importantly, Verrucomicrobiota, as well as Sanguibacter and Methylotenera are members that show patterns of correlation with Bd infection in Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs (Jani and Briggs, 2014).

Figure 6. Bacteria commonly isolated from amphibian skin (x-axis) also tend to dominate in culture-independent targeted amplicon sequencing (y-axis) and metagenomic studies, with some exceptions.

For example, Pseudomonas is a commonly isolated bacterial genus that is dominant in both culture and culture-independent assessments of amphibian skin bacteria. In contrast, Microbacterium is under-represented in culture-independent assessments perhaps due to difficulty in lysing Gram-positive cells during DNA extraction. The addition of a lysozyme incubation step during DNA extraction may help to reduce this bias (Teng et al., 2018). (Data from cultured isolates from Woodhams et al. (2015); data from amplicon sequencing studies from Kueneman et al. (2019).

Bacterial competition occurs in the mucosome via toxic molecules, secretion systems, bacteriocins, and understudied putative AMP defenses (Oulas et al., 2021). Cooperation and beneficial functions for the host may evolve in the microbiome when controlled by host immune effectors (Sharp and Foster, 2022). Such effectors have been studied in the human skin microbiome (Byrd et al., 2018), and a trait-based analysis of the functional diversity in amphibian skin is a next step for comparison among amphibian species and with human skin microbial traits (Bewick et al., 2019). Traits including motility, growth form and rate, spore formation, pH and temperature optima and range, and toxin production are relevant to amphibian skin microbiome assembly and function (Prest et al., 2018; Woodhams et al., 2018; Kueneman et al., 2019; Bates et al., 2022). Indeed, the ability to resist AMPs or host toxins (Fig. 4) and degrade mucus may be functions particularly relevant for establishment of microbiota on amphibian skin.

2.3. Mucus and its components

The mucosal layer that envelops amphibian skin serves myriad functions including minimization of water loss, regulation of cutaneous gas exchange, suspension of chemical defenses against predators, lubrication to resist predation and injury through environmental abrasion, and increasing stiction to promote climbing abilities (Toledo and Jared, 1995; Clarke, 2007; Haslam et al., 2014; Langkowski et al., 2019). Here, we focus on the primary components of amphibian skin mucus and their roles in shaping the adaptive microbiome.

While mucus is composed of up to 95% water (Creeth, 1978), it owes its viscoelastic properties to a complex network of highly-glycosylated proteins called mucins (Dubaissi et al., 2018). Mucins are defined as either membrane-bound or secreted, which can be further categorized into gel-forming and non-gel-forming types. Amphibian skin mucus is characterized by dominance of secreted gel-forming mucins produced in goblet cells of the epithelium, with some species such as X. tropicalis possessing at least 26 types of mucins (Hayes et al., 2007; Lang et al., 2016). These gel-forming mucins contain regions rich in proline, threonine and serine (PTS domains), which serve as sites for sugars to attach via O-glycosylation (Lang et al., 2016). In amphibians, these sugars include N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc), N-acetyl galactosamine (GalNAc), N-acetylneuraminic acid (Sialic acid), N-acetyl hexosamine (HexNAc), N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc), fucose, galactose, and mannose (Meyer et al., 2007; Lang et al., 2016; Dubaissi et al., 2018; Barbosa et al., 2022). Bound glycans enlarge the size of mucins, resulting in a brush-like shape that enhances solubility and capture of large quantities of water (Dubaissi et al., 2018; reviewed in Hansson, 2020).

At N- and C-terminal regions, where proline threonine serine-rich (PTS) domains give way to cystine knot (CK) and von Willebrand D (VWD) domains rich in cysteine, disulfide bonds polymerize mucin strands into a complex network (Perez-Vilar and Hill, 1999; Ambort et al., 2012; Lang et al., 2016). It is the combination of extensive glycosylation and the polymerization into mucin networks that create viscous gel-like mucus (McGuckin et al., 2011; Lang et al., 2016). Interspersed in this mucin network are electrolytes, lipids, peptides, immunoglobulins, microbes and their secondary metabolites that together make up the mucosome (Suppl. Table 1; reviewed in: Van Rooij et al., 2015; Varga et al., 2019).

2.3.1. Function of mucus in disease resistance

Most work in mucin-bacterial interactions is prompted by questions related to human health, but difficulty in studying these systems in mammals has led researchers to seek alternative test organisms (Dubaissi et al., 2014, 2018). For amphibian disease researchers, one fortuitous consequence from the use of Xenopus as stand-ins for mammalian subjects is greater insight into amphibian mucus and its role in disease dynamics. Host species must maintain mucosal integrity to prevent invasion by pathogens (McGuckin et al., 2011; Dubaissi et al., 2018). With respect to disease resistance, mucus functions first as a physical barrier, trapping potential pathogens so they may be removed from the skin by ciliated epithelial cells (reviewed in: Cone, 2009, Varga e al., 2019). One mucin (MucXS, formerly Otogl) has been identified as the primary structural mucin component in larval X. tropicalis mucus. Knockdowns of the MucXS gene in tadpoles resulted in a decrease in mucosal layer thickness from μ6μm to 0.9μm. Subsequent exposures to the opportunistic pathogen Aeromonas hydrophila showed increased host susceptibility to infection compared to tadpoles with intact MucXS (Dubaissi et al., 2018).

The assortment of glycans both free and bound to mucins directly influence microbial interactions in mucus (reviewed in Varga et al., 2019). These sugars are thought to allow for selection and control of beneficial microbiota that are able to exploit glycans as sources of energy, as well as inhibit infection by pathogens (Barbosa et al., 2022; Meyer et al., 2007). For example, α-D-mannose, GIcNAc, β-D-galactose, α-L-fucose can inhibit bacterial attachment to epithelial cells. Sialic acids regulate mucus pH and viscosity and are known to inhibit attachment to epithelial cells by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Wolska et al., 2005; Pastoriza Gallego and Hulen, 2006). Free and bound glycans can work to prevent infection by binding to lectins present on bacterial cell membranes, either trapping them to mucins or simply preventing their attachment to host epithelia (Hanisch et al., 2014; Padra et al., 2019). Other proteins and molecules are known to interact with mucin glycans, such as antigens and lectins, some of which are associated with antibiotic activity and immune responses when bound to mucin (Hanisch et al., 2014; Godula and Bertozzi, 2012; Kiwamoto et al., 2014). Further, mucins can also bind to phages that can act as another line of defense against bacterial infection, according to the Bacteriophage Adherence to Mucus (BAM) model (Barr et al., 2013; Almeida et al., 2019).

Maintenance of mucosal integrity to defend against would-be invaders must be balanced with the need to support communities of symbiotic or commensal microbes colonizing the skin. Binding specificity to bacteria seems to vary by bacterial species and body site and may be determined by the glycosylation structures present on mucins (Padra et al., 2019). Some bacteria in the gut can metabolize outer branches of the glycan structure, opening avenues for selection of beneficial microbes able to capitalize on this energy source via host modulation of glycan composition. Simultaneously, this ability may allow opportunistic pathogens to disturb mucosal integrity and invade epithelial tissue (Tailford et al., 2015). Additionally, some pathogens have developed strategies for degrading or bypassing the mucus barrier through secretion of glycosyl hydrolases and other compounds that can alter mucus pH and destabilize mucin networks (Engevik et al., 2021; Celli et al., 2009).