Abstract

Background

Laboratory studies have linked nickel with the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (CVD); however, few observational studies in humans have confirmed this association.

Objective

This study aimed to use urinary nickel concentrations, as a biomarker of environmental nickel exposure, to evaluate the cross-sectional association between nickel exposure and CVD in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults.

Methods

Data from a nationally representative sample (n = 2702) in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–20 were used. CVD (n = 326) was defined as self-reported physicians’ diagnoses of coronary heart disease, angina, heart attack, or stroke. Urinary nickel concentrations were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Logistic regression with sample weights was used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of CVD.

Results

Urinary nickel concentrations were higher in individuals with CVD (weighted median 1.34 μg/L) compared to those without CVD (1.08 μg/L). After adjustment for demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and other risk factors for CVD, the ORs (95% CIs) for CVD compared with the lowest quartile of urinary nickel were 3.57 (1.73–7.36) for the second quartile, 3.61 (1.83–7.13) for the third quartile, and 2.40 (1.03–5.59) for the fourth quartile. Cubic spline regression revealed a non-monotonic, inverse U-shaped, association between urinary nickel and CVD (Pnonlinearity < 0.001).

Conclusions

Nickel exposure is associated with CVD in a non-monotonic manner among U.S. adults independent of well-known CVD risk factors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12403-023-00579-4.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Nickel, Epidemiology, U.S. adults

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number one cause of death and a leading contributor to mortality and morbidity worldwide (Roth et al. 2020). Between 1990 and 2019, prevalent cases of total CVD nearly doubled from 271 to 523 million globally, with the number of CVD deaths reaching 18.6 million in 2019 (Roth et al. 2020). Despite previously declining prevalence, age-standardized CVD rates have begun to rise in several high-income countries (Roth et al. 2020). While cardiometabolic, behavioral, and social risk factors are all viewed as major drivers of CVD, considerable experimental and epidemiological evidence supports the role of widespread environmental metals in the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (Solenkova et al. 2014; Lamas et al. 2016). Identification of additional modifiable environmental risk factors is urgently needed to inform public health policies and reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Nickel is frequently used in the nickel–cadmium battery, alloy production, and electroplating industries leading to high levels of occupational exposure (ATSDR, 2005). These industries, as well as trash incineration, mining, and fossil fuels emit nickel into the environment. For the general population, the most common non-occupational sources of nickel exposure are food, air, tobacco, and drinking water (Genchi et al. 2020). On average, a person is exposed to approximately 170 µg of nickel in a day through food, drinking water, and air; however, exposure can be higher for people who live in close proximity to areas where nickel is mined and refined (ATSDR, 2005). The toxicity of nickel is dependent on the route of exposure (inhalation, oral, dermal) and the solubility of the specific nickel compound (Coogan et al. 1989).

Exposure to nickel may induce oxidative stress and inflammation, which are known mechanisms in the pathogenesis of CVD (Jomova and Valko 2011). Nickel may also disrupt endocrine and endothelial vascular functions (Prozialeck et al. 2008; Iavicoli et al. 2009). Studies in ApoE knock-out mice have shown that inhalation of nickel nanoparticles is associated with altered cardiac function and may induce oxidative stress and inflammation that ultimately contribute to the progression of atherosclerosis (Lippmann et al. 2006; Kang et al. 2011). Carotid artery plaque is a measure of atherosclerosis and considered a major CVD risk factor (Polak et al. 2013). One study of Swedish adults observed that after adjustment for several CVD risk factors, nickel levels were related to the number of carotid arteries with plaques in an inverted U-shaped manner (Lind et al. 2012). Similarly, a study among Chinese adults observed an inverted U-shaped dose–response curve for the association between urinary nickel and hypertension (Shi et al. 2022). Furthermore, two independent studies have reported increased levels of nickel in biospecimens from coronary heart disease patients (Leach et al. 1985; Afridi et al. 2006).

In the present study, we used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to examine the association of urinary nickel concentrations, as a biomarker of environmental nickel exposure (McNeely et al. 1972), with CVD in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults.

Methods

Study Population

The NHANES is administered by the National Center for Health Statistics of the centers for disease control and prevention (CDC). Participants are selected using a stratified, multistage national probability sampling design to represent the non-institutionalized U.S. population. Information on demographics, diet, lifestyle, medical conditions, and socioeconomic status are collected as part of NHANES. Furthermore, samples are collected for laboratory tests and thorough health examinations are performed. These data are made public every 2 years. NHANES has been approved by the national center for health statistics ethics review board and all participants gave written informed consent.

In the present study, we used data from NHANES 2017–20. The 2019–2020 data collection was suspended in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Because this data cycle was incomplete and not nationally representative, it was combined with the 2017–2018 data cycle to form a nationally representative sample of 2017–March 2020 pre-pandemic data (Stierman et al. 2021). In total, CVD and urinary nickel concentrations data were available for 2739 adults aged ≥ 18 years. Based on visual inspection of box and QQ plots, outliers of urinary nickel concentrations were excluded (n = 5). After additionally excluding individuals who were pregnant (n = 26) and individuals with missing covariate information (n = 6), 2702 adult participants were included in the study.

Exposure Assessment

Nickel concentrations from urine samples were recorded using the inductively coupled plasma-dynamic reaction cell-mass spectrometry at the inorganic and radiation analytical toxicology division of laboratory sciences, national center for environmental health, centers for disease control and prevention (Atlanta, GA, USA). The lower limit of detection (LLOD) of nickel concentration in urine was 0.31 μg/L. Analytic results below the LLOD (7.5%) were given values of the LLOD divided by the square root of 2, per NHANES analytic guidance (CDC 2018). To account for variability in urine dilution, recommended adjustments were made for urinary creatinine in all analyses (Barr et al. 2005).

Outcome Ascertainment

CVD was defined as self-reported physicians’ diagnoses of coronary heart disease, angina, heart attack, or stroke. Trained interviewers collected information of self-reported previous diagnosis of CVD.

Potential Confounders

Standardized surveys were used to collect data on age, education, family income, medical conditions, race/ethnicity, and smoking status (Johnson et al. 2013). Blood draws, blood pressure (BP) measurements, and urine collections took place at NHANES mobile examination sites. The categories for race/ethnicity were Hispanic (Mexican and non-Mexican Hispanic), non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and other mixed races/ethnicities. For education, the categories were higher than high school (college or associates (AA) degree and college graduate or higher), high school, and less than high school. Categories for family income-to-poverty ratios were ≤ 1.30, 1.31–3.50, > 3.50, and missing (Johnson et al. 2013). Participants who smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime were considered never smokers. Participants who smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime but did not smoke at the time of the questionnaire were considered former smokers, and participants who smoked cigarettes at the time of the questionnaire were considered current smokers (CDC 2017). Electronic cigarette use was defined as responding affirmatively for using an electronic cigarette in the previous 5 days. The global physical activity questionnaire was used to assess the physical activity level of the participants, with the duration and intensity of activities being calculated using metabolic equivalents of task (MET) minutes per week (WHO 2014). Height and weight were assessed by clinical staff for calculating BMI. For participants with missing information on BMI, self-reported height and weight were used for calculating BMI when possible (n = 45). Mean brachial BP was measured using an Omron HEM-907XL with appropriately sized cuffs (CDC, 2019). After participants rested in a seated position for five minutes, technicians took 3 BP measurements, each 60 s apart. Per ACC/AHA guidelines, hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg or the current use of antihypertensive pharmacologic treatment (Whelton et al. 2018). Urinary creatinine, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglyceride, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) levels were determined enzymatically using a Cobas 6000 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) (CDC 2018). Whole blood lead concentrations were measured using the inductively coupled plasma–dynamic reaction cell–mass spectrometry (CDC 2018). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation developed by a research group of the national institutes of diabetes, digestive and kidney disease (Levey et al. 2009).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using NHANES analytical guidelines (Johnson et al. 2013). The Taylor series linearization method and appropriate weights were utilized to represent the non-institutionalized U.S. demographic (Johnson et al. 2013). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to compare continuous variables, while Chi-squared tests were utilized to compare categorical variables at baseline.

Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) of CVD according to quartiles of urinary nickel concentrations. We adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and urinary creatinine in Model 1. We additionally adjusted for family income-to-poverty ratios, education, physical activity, smoking status, electronic cigarette use, hypertension, triglyceride levels, LDL levels, HDL levels, hsCRP levels, and body mass index in Model 2. In Model 3, we adjusted for urinary cadmium concentrations, blood lead concentrations, and eGFR in addition to all factors that had been adjusted for in Model 2. Because heavy metals are linked to cardiovascular disease (Navas-Acien et al. 2007; Nigra et al. 2016), urinary cadmium and blood lead concentrations were included as confounders.

We conducted interaction and stratified analyses by hypertension, HDL, LDL, hsCRP, triglyceride, and smoking status to evaluate effect modification from other well-known CVD risk factors. Because kidney function could affect urinary nickel excretion, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding individuals with eGFR < 60 (mL/min/1.73m2) to test the robustness of our findings. Because urinary nickel expressed as µg/g creatinine is a more clinically relevant measure, primary analyses were repeated using creatinine-corrected nickel.

Multivariate adjusted restricted cubic spline models were utilized to evaluate the shape of the relationship between urinary nickel and odds of CVD with knots located at the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th percentiles for urinary nickel.

All statistical analyses were performed using survey procedures of the SAS 9.4 package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The level of statistical significance (α) was set at 0.05.

Results

The final sample consisted of 2702 participants (49.0% male, mean ± SEM age 47.6 ± 0.9 years; 51.0% female, mean ± SEM age 49.5 ± 1.1 years) of which 326 had CVD. The median urinary nickel concentration was 1.11 µg/L (interquartile range [IQR] 0.64–1.88), and the weighted prevalence of CVD was 9.5% (SE 1.3%). Participants with older age, lower levels of family income, hypertension, current smokers, had higher urine concentrations of cadmium and creatinine, and those with lower levels of HDLs were more likely to have higher urinary concentrations of nickel (Table 1). The weighted median (IQR) concentration of nickel among individuals with CVD compared to those without CVD was significantly higher (P = 0.002), at 1.34 (0.83–2.56) µg/L and 1.08 (0.62–1.82) µg/L, respectively. Urinary nickel concentrations according to population characteristics are given in Table S1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2017–20 according to quartiles of urinary nickel concentrations

| Urinary nickel quartiles (μg/L) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (< 0.65) | Q2 (0.66–1.16) | Q3 (1.17–1.94) | Q4 (> 1.95) | P-value | |

| No. Participants | 677 | 681 | 668 | 676 | |

| Age (years) | 47.8 ± 1.34 | 47.4 ± 1.18 | 48.9 ± 1.03 | 50.3 ± 1.14 | 0.008 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 46.9 (3.6) | 47.3 (2.9) | 53.7 (2.9) | 48.4 (2.6) | 0.33 |

| Female | 53.1 (3.6) | 52.7 (2.9) | 46.3 (2.9) | 51.6 (2.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 62.6 (3.2) | 65.2 (3.6) | 63.6 (3.0) | 58.1 (4.0) | 0.13 |

| Hispanic | 17.5 (1.7) | 14.8 (2.2) | 15.0 (2.0) | 16.7 (2.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 9.3 (1.2) | 11.4 (1.8) | 12.7 (1.8) | 12.7 (1.6) | |

| Other | 10.6 (1.9) | 8.6 (1.4) | 8.7 (1.4) | 12.6 (1.8) | |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 10.0 (1.4) | 10.2 (1.5) | 12.1 (2.0) | 13.4 (1.5) | 0.32 |

| High school | 26.1 (3.3) | 28.0 (2.7) | 32.4 (2.5) | 27.8 (2.9) | |

| College or higher | 63.9 (3.2) | 61.8 (3.0) | 55.5 (3.5) | 58.8 (3.3) | |

| Smoking | |||||

| Never smoker | 56.2 (4.0) | 52.8 (2.9) | 62.9 (3.0) | 55.2 (4.0) | 0.02 |

| Current smoker | 15.4 (2.0) | 14.5 (2.2) | 12.9 (1.8) | 21.9 (3.2) | |

| Past smoker | 28.3 (4.1) | 32.7 (3.5) | 24.2 (2.3) | 22.9 (2.8) | |

| Electronic cigarette use | |||||

| Yes | 1.1 (0.4) | 2.3 (0.9) | 3.6 (1.1) | 1.6 (0.5) | 0.07 |

| No | 98.9 (0.4) | 97.7 (0.9) | 96.4 (1.1) | 98.4 (0.5) | |

| Family income-to-poverty ratio | |||||

| < 1.3 | 13.0 (1.3) | 16.8 (1.6) | 17.5 (1.5) | 19.6 (1.9) | 0.02 |

| 1.3–3.5 | 29.1 (3.5) | 34.2 (3.0) | 31.1 (2.5) | 31.6 (2.2) | |

| ≥ 3.5 | 47.9 (3.3) | 39.7 (3.8) | 37.0 (3.7) | 34.4 (3.1) | |

| Missing | 10.0 (1.6) | 10.0 (1.6) | 14.4 (2.6) | 14.4 (2.2) | |

| Physical activity (MET-min/week) | |||||

| < 600 | 29.4 (2.8) | 30.9 (3.2) | 34.9 (3.5) | 33.8 (2.1) | 0.65 |

| 600–1199 | 11.3 (2.1) | 9.4 (1.8) | 8.5 (1.4) | 7.1 (1.5) | |

| > 1200 | 59.3 (3.3) | 59.7 (2.7) | 56.6 (3.4) | 59.2 (2.5) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| < 25.0 | 30.8 (2.9) | 25.0 (2.9) | 21.5 (2.3) | 27.3 (2.8) | 0.13 |

| 25–29.9 | 31.4 (3.2) | 30.7 (2.3) | 34.3 (2.4) | 26.1 (2.4) | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 37.8 (3.0) | 44.3 (3.6) | 44.2 (3.0) | 46.6 (3.8) | |

| Hypertension | |||||

| yes | 26.6 (2.8) | 33.8 (3.1) | 37.3 (3.0) | 37.9 (3.3) | 0.006 |

| no | 73.4 (2.8) | 66.2 (3.1) | 62.7 (3.0) | 62.1 (3.3) | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 55.4 ± 0.79 | 54.2 ± 0.89 | 52.0 ± 1.09 | 53.0 ± 0.68 | 0.03 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 110 ± 3.65 | 113 ± 2.97 | 105 ± 2.58 | 104 ± 3.11 | 0.15 |

| hsCRP (mg/dL) | 3.48 ± 0.59 | 4.18 ± 0.40 | 3.55 ± 0.36 | 3.82 ± 0.23 | 0.67 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 105 ± 7.26 | 108 ± 6.30 | 104 ± 5.41 | 112 ± 9.42 | 0.87 |

| Urine cadmium (μg/L) | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Blood lead (μg/dL) | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 1.16 ± 0.05 | 0.06 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 91.2 ± 1.70 | 91.7 ± 1.06 | 89.0 ± 1.36 | 88.7 ± 1.66 | 0.12 |

| Urine creatinine (mg/dL) | 62.8 ± 2.61 | 101 ± 3.10 | 148 ± 5.00 | 174 ± 3.99 | < 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||||

| yes | 6.1 (1.4) | 9.1 (1.8) | 10.1 (1.5) | 12.9 (1.7) | 0.007 |

| no | 93.9 (1.4) | 90.9 (1.8) | 89.9 (1.5) | 87.1 (1.7) | |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are given as the weighted mean ± SEM for continuous variables and weighted percentages (SEs) for categorical variables

BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MET, metabolic equivalent of task

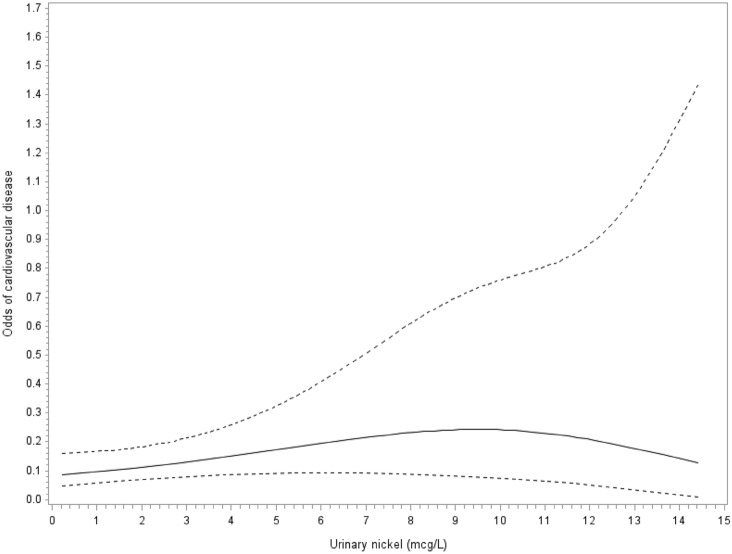

In age, sex, race/ethnicity adjusted models analyzed according to quartile, there was no association of urinary nickel concentrations (μg/L) with cardiovascular disease (Table 2). However, after further adjustment for additional demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, and CVD risk factors, nickel exposure showed relationship with cardiovascular disease. The ORs (95% CIs) for CVD compared with the lowest quartile (< 0.65 μg/L) were 3.83 (2.01–7.28) for the second quartile (0.66–1.17 μg/L), 3.86 (2.05–7.29) for the third quartile (1.18–1.95 μg/L), and 2.52 (1.15–5.56) for the fourth quartile (> 1.96 μg/L). After additional adjustment for urine cadmium and blood lead levels, the ORs (95% CIs) were 3.57 (1.73–7.36) for participants in the second quartile, 3.61 (1.83–7.13) for participants in the third quartile, and 2.40 (1.03–5.59) in the highest quartile. Cubic spline regression shows a non-monotonic dose–response suggestive of an inverted U-shaped relationship of urinary nickel with CVD (Pnonlinearity < 0.001; Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Associations of urinary nickel concentration with cardiovascular disease in U.S. adults

| Urinary nickel quartiles (μg/L) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (< 0.65) | Q2 (0.66–1.17) | Q3 (1.18–1.95) | Q4 (> 1.96) | |

| Median, μg/L | 0.43 | 0.91 | 1.50 | 2.74 |

| No. of cases/participants | 64/677 | 74/681 | 86/668 | 102/676 |

| Model 1 | 1 (reference) | 1.47 (0.90–2.40) | 1.47 (0.71–3.06) | 1.64 (0.85–3.17) |

| Model 2 | 1 (reference) | 3.83 (2.01–7.28) | 3.86 (2.05–7.29) | 2.52 (1.15–5.56) |

| Model 3 | 1 (reference) | 3.57 (1.73–7.36) | 3.61 (1.83–7.13) | 2.40 (1.03–5.59) |

Data show odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) in parentheses

Model 1: adjusted for age (years), sex (male, female), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and other race), and urinary creatinine

Model 2: adjusted for all factors in Model 1 plus education (less than high school, high school, college or higher), family income (family income-to-poverty ratio: < 1.3, 1.3–3.5, ≥ 3.5, or missing), cigarette smoking (never, past, current), electronic cigarette use (yes, no), physical activity (< 600, 600–1199, ≥ 1200 MET-min/week), hypertension (yes or no), triglycerides levels, LDL levels, HDL levels, hsCRP levels, body mass index (< 25.0, 25.0–29.9, ≥ 30.0 kg/m2), and eGFR

Model 3: adjusted for all factors in Model 2 plus urine cadmium levels and blood lead levels

Fig. 1.

Adjusted cubic spline regression model showing the association between urinary nickel (mcg/L) and the odds of cardiovascular disease. Models adjusted for age, sex, race, and urinary creatinine. The solid and dashed lines represent the odds and 95% confidence interval for cardiovascular disease. Knots are located at the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th percentiles for urinary nickel

Urinary nickel concentrations (μg/L) were correlated with creatinine-corrected nickel concentrations (rs = 0.52, P < 0.001). The relationship between urinary nickel and CVD was completely attenuated and no longer significant for the association between urinary nickel (μg/g creatinine) and odds of CVD (Table S2); however, the non-monotonic dose–response suggestive of an inverted U-shaped relationship was maintained in the cubic spline regression analysis (Pnonlinearity < 0.001; Figure S1).

There was a significant interaction of urinary nickel concentrations with HDL (Pinteraction = 0.006), hsCRP levels (Pinteraction = 0.003), and smoking status (Pinteraction = 0.002) for the association with CVD (Table S3). The OR (95% CI) of CVD among participants with normal HDL levels in the second quartile of urinary nickel concentration was 2.22 (1.04–4.73) before increasing to 5.31 (2.11–13.4) for the third quartile and decreasing to 2.86 (0.88–9.26) in the highest quartile of urinary nickel concentration. Among participants with low HDL status, the OR (95% CI) was 3.51 (1.22–10.1) in the second quartile of urinary nickel concentration, but there were no significant associations observed in the third and fourth quartiles. Among participants with normal hsCRP levels, the OR (95% CI) was 2.48 (0.56–11.1) for participants in the second quartile and increased to 5.68 (1.14–28.2) in the third quartile and 7.14 (1.50–34.0) for participants in the highest quartile. Among participants with high hsCRP, the OR (95% CI) was 3.01 (1.05–8.65) in the second quartile of urinary nickel concentration, but there were no significant associations observed in the third and fourth quartiles. Among non-smokers, the OR (95% CI) was 1.16 (0.45–2.96) in the second quartile before increasing to 3.34 (1.32–8.45) in the third quartile and decreasing to 2.69 (0.85–8.55) in the fourth quartile. Among participants who were ever-smokers, the OR (95% CI) was 7.29 (2.47–21.5) in the second quartile and 3.60 (1.34–9.68) in the third quartile before decreasing to 4.11 (1.13–14.9) in the fourth quartile.

No significant interactions were found for hypertension, LDL, or triglyceride status (Pinteraction > 0.05 for each). Among associations lacking significant interactions, the OR (95% CI) of CVD were elevated among normotensive participants in the second quartile at 2.22 (1.04–4.73) and in the third quartile at 3.44 (1.46–8.12) among participants with hypertension. Among participants with normal LDL, the OR (95% CI) of CVD was elevated in the fourth quartile of urinary nickel concentration at 3.63 (1.40–9.43), whereas among those with high LDL levels ORs (95% CIs) were elevated in the second quartile at 7.46 (2.40–23.1) and third quartile at 8.58 (2.37–31.1). Among those with normal triglyceride levels, the ORs (95% CIs) of CVD were 2.77 (1.14–6.73) in the second quartile and 4.14 (1.70–10.1) in the third quartile of urinary nickel concentration and for participants with high triglycerides the OR (95% CI) was elevated in the second quartile at 17.3 (1.25–238).

The association of urinary nickel concentrations with CVD did not change appreciably in a sensitivity analysis when excluding individuals with eGFR < 60 (mL/min/1.73m2; Table S4).

Discussion

In the present study, the association between urinary nickel concentration and cardiovascular disease exhibited a non-monotonic dose–response suggestive of an inverted U-shaped relationship. Intermediate concentrations of urinary nickel were significantly associated with elevated odds of CVD among U.S. adults after adjustment for other CVD risk factors (age, sex, socioeconomic status, lifestyle, BMI, hypertension, HDL and LDL cholesterol, triglycerides); however, this association was attenuated and no longer significant among participants in the highest quartile of urinary nickel concentration.

To our knowledge, this study represents the first in a nationally representative sample to examine the association between environmental nickel exposure and CVD in the general U.S. adult population. Consistent with our findings, a cross-sectional study of Swedish adults by Lind et al. (2012) observed that, after adjustment for several CVD risk factors, nickel levels were related to the number of carotid arteries with plaques, a major CVD risk factor (Polak et al. 2013), in a similar inverted U-shaped manner. Similarly, a study among Chinese adults observed an inverted U-shaped dose–response curve for the association between urinary nickel and hypertension (Shi et al. 2022). This type of relationship suggests that physiological adaptations to high exposure may protect from the detrimental effects of nickel and is commonly observed in epidemiological studies of endocrine disruptors (Vandenberg et al. 2012), for which nickel is classified (Stinson et al. 1992). Several underlying mechanisms have been explored to explain non-monotonic dose responses (Vandenberg and Blumberg 2018), such as the one observed in this study; however, the exact mechanism remains elusive for nickel. Corroborating the non-monotonic effects of nickel are two studies among adults in China and the U.S. that observed a plateau in the relationship between environmental nickel exposure and diabetes (Liu et al. 2015; Titcomb et al. 2021).

Humans are often exposed to nickel in the environment due to the prevalence of nickel in food, drinking water, tobacco, and air (Genchi et al. 2020). As cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for CVD (Law et al. 1997) and a source of nickel exposure, cigarette use may confound the observed findings between nickel exposure and CVD (Genchi et al. 2020). In the present study, the association between urinary nickel concentration and CVD was present among both non-smokers and ever-smokers but appeared stronger among those categorized as ever-smokers, suggesting that smoking modifies the relationship between nickel exposure and CVD. This study found nickel concentration above the LLOD in 92.5% of urine samples. This detection frequency is slightly below the detection rates reported in China, Canada, and a multi-ethnic cohort of U.S. adult women, which were between 96 and 100% (Liu et al. 2015; Saravanabhavan et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2020).

In a countrywide study, Bell et al. (2009) reported that communities in the U.S. with higher fine particulate matter content of nickel were found to have a higher risk of cardiovascular hospitalizations and CVD mortality. Similarly, population study analyses conducted by Lippman et al. (2006) reported significant differences in mortality rates associated with nickel concentrations in ambient air. Alternately, Wang et al. (2014) found no significant association between long-term exposure to the nickel component of ambient particulate matter and CVD mortality. While these studies have limitations in the context of our research, due to their focus on ambient air, they provide further evidence for an association between nickel exposure and CVD, even after controlling for socioeconomic, demographic, and CVD risk factors.

The association between nickel exposure and CVD is biologically plausible. Acute, aerosolized nickel exposure causes delayed bradycardia and arrhythmogenesis in rats (Campen et al. 2001). Furthermore, nickel enhances calcium influx in both rat heart and canine coronary artery cells in culture, inducing vasoconstriction and early afterdepolarizations (Golovko et al. 2003), a common cause of ventricular arrhythmias (Weiss et al. 2010). Nickel is also involved in many pathways that are critical in the development of CVD (Denkhaus and Salnikow 2002). Experiments in vitro have shown that nickel exposure regulates the expression of several transcription factors, including ATF-1 (Salnikow et al. 1997), HIF-1 (Salnikow et al. 1999), and NF-kB (Goebeler et al. 1995), that regulate pathways involved in cell adhesion, oxygen homeostasis, calcium homeostasis and inflammation. In addition, animal studies have consistently found that acute and sub-chronic exposure to nickel nanoparticles is correlated with cardiac stress and altered cardiac function. Studies in ApoE knock-out mice models have shown that nickel nanoparticle exposure increased mitochondrial DNA damage in the aorta and up-regulated mRNA levels of inflammatory cytokine genes (Kang et al. 2011) as well as altered heart rate and heart rate variability (Lippmann et al. 2006). These observations suggest that the cardiovascular effects of nickel may include vascular inflammation, the induction of oxidative stress, and atherosclerosis, which may be precursors to cardiac dysrhythmias, myocardial infarctions, and increased risk of mortality. While these studies support a link between nickel exposure and CVD, the mechanistic underpinnings of the non-monotonic dose–response relationships observed in the present, and other epidemiological studies, needs further investigation.

The strengths of this analysis include the use of NHANES, comprehensive and nationally representative data that includes demographic, socioeconomic, and lifestyle factors. This sample allows for adjusting for confounding from a variety of cardiovascular disease risk factors and generalization to a broader population. The present study also had several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of NHANES data prevents us from establishing a temporal relationship or drawing causal inferences. Longitudinal studies are essential for the confirmation of our findings. Second, perceived challenges with urine sample collection led NHANES researchers to collect spot urine samples rather than 24-h urine samples. It is well established that nickel is excreted through urine with a half-life between 20 and 27 h (Nielsen et al. 1999). Single measurements of urinary nickel levels may be imperfect markers of chronic exposure (Wang et al. 2016); thus, reverse causation cannot be ruled out in the present analysis. Although, short half-life biomarkers may reflect long-term exposure if the exposure is constant over time. Third, despite adjustment for urinary creatinine in the primary analysis, the repeated analysis conducted using quartiles of urinary creatinine-corrected nickel resulted in non-significant results; however, the results of the spline models were consistent for urinary creatinine-corrected nickel. Fourth, even after adjustment for many potential confounders, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding by other sociodemographic and lifestyle determinants of nickel exposure.

In this nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, urinary nickel, as a biomarker of environmental nickel exposure, was significantly associated with CVD in a non-monotonic dose–response suggestive of an inverted U-shaped relationship, independently of several demographic, lifestyle, socioeconomic, and CVD risk factors. These findings are consistent with those from other populations (Lind et al. 2012; Shi et al. 2022) and suggest that intermediate nickel exposure may be a novel risk factor for the pathogenesis of CVD. However, the mixed results of the analysis of urinary creatinine-corrected nickel necessitate replication of our findings. The pathophysiological mechanisms behind these observations and the temporal relationship between nickel exposure and CVD require further research.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. Patrick Ten Eyck and Linda M. Rubenstein for providing statistical consultations.

Author Contribution

JC: Writing—Original Draft; HJL: Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision; SSF: Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision; TJT: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision.

Funding

At the time this research was conducted, TJT was a research trainee of the Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center with funding from the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (T32DK112751-05). TJT is supported by the Carter Chapman Shreve Foundation and Fellowship Fund at the University of Iowa. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data Availability

The original datasets can be downloaded from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm. The analytical dataset and code for data cleaning and analysis have been deposited to the Iowa Research Online depository available at 10.25820/code.006186.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the aggregate data produced in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Afridi HI, Kazi TG, Kazi GH, Jamali MK, Shar GQ. Essential trace and toxic element distribution in the scalp hair of Pakistani myocardial infarction patients and controls. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2006;113:19–34. doi: 10.1385/BTER:113:1:19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR. (2005) Toxicological p rofile for nickel. book toxicological profile for nickel, City: U.S. Dept. of health and human services, public health service, agency for Toxic substances and disease registry

- Barr DB, Wilder LC, Caudill SP, Gonzalez AJ, Needham LL, Pirkle JL. Urinary creatinine concentrations in the U.S. population: implications for urinary biologic monitoring measurements. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:192–200. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell ML, Ebisu K, Peng RD, Samet JM, Dominici F. Hospital admissions and chemical composition of fine particle air pollution. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:1115–1120. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1240OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campen MJ, Nolan JP, Schladweiler MC, Kodavanti UP, Evansky PA, Costa DL, Watkinson WP. Cardiovascular and thermoregulatory effects of inhaled PM-associated transition metals: a potential interaction between nickel and vanadium sulfate. Toxicol Sci. 2001;64:243–252. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/64.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2017) Adult tobacco use information: glossary. book adult tobacco use information: glossary, City.

- CDC. (2018) National health and nutrition examination survey laboratory procedures manual. Atlanta, GA.

- CDC. (2019) National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) blood pressure procedures manual. book national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) blood pressure procedures manual, city.

- Coogan TP, Latta DM, Snow ET, Costa M. Toxicity and carcinogenicity of nickel compounds. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1989;19:341–384. doi: 10.3109/10408448909029327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denkhaus E, Salnikow K. Nickel essentiality, toxicity, and carcinogenicity. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;42:35–56. doi: 10.1016/S1040-8428(01)00214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genchi G, Carocci A, Lauria G, Sinicropi MS, Catalano A. Nickel: human health and environmental toxicology. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebeler M, Roth J, Brocker EB, Sorg C, Schulze-Osthoff K. Activation of nuclear factor-kappa B and gene expression in human endothelial cells by the common haptens nickel and cobalt. J Immunol. 1995;155:2459–2467. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.155.5.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovko VA, Bojtsov IV, Kotov LN. Single and multiple early afterdepolarization caused by nickel in rat atrial muscle. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2003;22:275–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavicoli I, Fontana L, Bergamaschi A. The effects of metals as endocrine disruptors. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2009;12:206–223. doi: 10.1080/10937400902902062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CL, Paulose-Ram R, Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kruszon-Moran D, Dohrmann SM, Curtin LR. National health and nutrition examination survey: analytic guidelines, 1999–2010. Vital Health Stat. 2013;2:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomova K, Valko M. Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Toxicology. 2011;283:65–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang GS, Gillespie PA, Gunnison A, Moreira AL, Tchou-Wong KM, Chen LC. Long-term inhalation exposure to nickel nanoparticles exacerbated atherosclerosis in a susceptible mouse model. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:176–181. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamas GA, Navas-Acien A, Mark DB, Lee KL. Heavy metals, cardiovascular disease, and the unexpected benefits of chelation therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2411–2418. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and ischaemic heart disease: an evaluation of the evidence. BMJ. 1997;315:973–980. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7114.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach CN, Jr, Linden JV, Hopfer SM, Crisostomo MC, Sunderman FW., Jr Nickel concentrations in serum of patients with acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris. Clin Chem. 1985;31:556–560. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/31.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind PM, Olsen L, Lind L. Circulating levels of metals are related to carotid atherosclerosis in elderly. Sci Total Environ. 2012;416:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann M, Ito K, Hwang JS, Maciejczyk P, Chen LC. Cardiovascular effects of nickel in ambient air. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1662–1669. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Sun L, Pan A, Zhu M, Li Z, ZhenzhenWang Z, Liu X, Ye X, Li H, Zheng H, et al. Nickel exposure is associated with the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Chinese adults. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:240–248. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely MD, Nechay MW, Sunderman FW., Jr Measurements of nickel in serum and urine as indices of environmental exposure to nickel. Clin Chem. 1972;18:992–995. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/18.9.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navas-Acien A, Guallar E, Silbergeld EK, Rothenberg SJ. Lead exposure and cardiovascular disease–a systematic review. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:472–482. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen GD, Soderberg U, Jorgensen PJ, Templeton DM, Rasmussen SN, Andersen KE, Grandjean P. Absorption and retention of nickel from drinking water in relation to food intake and nickel sensitivity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;154:67–75. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigra AE, Ruiz-Hernandez A, Redon J, Navas-Acien A, Tellez-Plaza M. Environmental metals and cardiovascular disease in adults: a systematic review beyond lead and cadmium. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2016;3:416–433. doi: 10.1007/s40572-016-0117-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polak JF, Szklo M, Kronmal RA, Burke GL, Shea S, Zavodni AE, O'Leary DH. The value of carotid artery plaque and intima-media thickness for incident cardiovascular disease: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000087. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prozialeck WC, Edwards JR, Nebert DW, Woods JM, Barchowsky A, Atchison WD. The vascular system as a target of metal toxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2008;102:207–218. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, Barengo NC, Beaton AZ, Benjamin EJ, Benziger CP, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2982–3021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salnikow K, Wang S, Costa M. Induction of activating transcription factor 1 by nickel and its role as a negative regulator of thrombospondin I gene expression. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5060–5066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salnikow K, An WG, Melillo G, Blagosklonny MV, Costa M. Nickel-induced transformation shifts the balance between HIF-1 and p53 transcription factors. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1819–1823. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.9.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saravanabhavan G, Werry K, Walker M, Haines D, Malowany M, Khoury C. Human biomonitoring reference values for metals and trace elements in blood and urine derived from the Canadian health measures survey 2007–2013. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2017;220:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi P, Liu S, Xia X, Qian J, Jing H, Yuan J, Zhao H, Wang F, Wang Y, Wang X, et al. Identification of the hormetic dose-response and regulatory network of multiple metals co-exposure-related hypertension via integration of metallomics and adverse outcome pathways. Sci Total Environ. 2022;817:153039. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solenkova NV, Newman JD, Berger JS, Thurston G, Hochman JS, Lamas GA. Metal pollutants and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms and consequences of exposure. Am Heart J. 2014;168:812–822. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll MD, Chen T-C, Davy O, Fink S, Fryar CD, Gu Q, Hales CM, Hughes JP, et al. (2021) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes Doi: 10.15620/cdc:106273.

- Stinson TJ, Jaw S, Jeffery EH, Plewa MJ. The relationship between nickel chloride-induced peroxidation and DNA strand breakage in rat liver. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992;117:98–103. doi: 10.1016/0041-008X(92)90222-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titcomb TJ, Liu B, Lehmler HJ, Snetselaar LG, Bao W. Environmental Nickel Exposure and Diabetes in a Nationally Representative Sample of US Adults. Expo Health. 2021;13:697–704. doi: 10.1007/s12403-021-00413-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg LN, Blumberg B. Alternative approaches to dose-response modeling of toxicological endpoints for risk assessment: nonmonotonic dose responses for endocrine disruptors, Third Edition. In: McQueen CA, editor. Comprehensive Toxicology. Oxford: Elsevier; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg LN, Colborn T, Hayes TB, Heindel JJ, Jacobs DR, Jr, Lee DH, Shioda T, Soto AM, vom Saal FS, Welshons WV, et al. Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses. Endocr Rev. 2012;33:378–455. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Beelen R, Stafoggia M, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Andersen ZJ, Hoffmann B, Fischer P, Houthuijs D, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Weinmayr G, et al. Long-term exposure to elemental constituents of particulate matter and cardiovascular mortality in 19 European cohorts: results from the ESCAPE and TRANSPHORM projects. Environ Int. 2014;66:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YX, Feng W, Zeng Q, Sun Y, Wang P, You L, Yang P, Huang Z, Yu SL, Lu WQ. Variability of metal levels in spot, first morning, and 24-hour urine samples over a 3-month period in healthy adult Chinese men. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:468–476. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Herman WH, Mukherjee B, Harlow SD, Park SK. Urinary metals and incident diabetes in midlife women: study of women’s health across the nation (SWAN) BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JN, Garfinkel A, Karagueuzian HS, Chen PS, Qu Z. Early afterdepolarizations and cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1891–1899. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2014) Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide. Book Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide, City.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original datasets can be downloaded from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm. The analytical dataset and code for data cleaning and analysis have been deposited to the Iowa Research Online depository available at 10.25820/code.006186.