Abstract

Background

Mailed fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) programs are increasingly utilized for population-based colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. Advanced notifications (primers) are one behavioral designed feature of many mailed FIT programs, but few have tested this feature among Veterans.

Objective

To determine if an advanced notification, a primer postcard, increases completion of FIT among Veterans.

Design

This is a prospective, randomized quality improvement trial to evaluate a postcard primer prior to a mailed FIT versus mailed FIT alone.

Participants

A total of 2404 Veterans enrolled for care at a large VA site that were due for average-risk CRC screening.

Intervention

A written postcard sent 2 weeks in advance of a mailed FIT kit that contained information on CRC screening and completing a FIT.

Main Measures

Our primary outcome was FIT completion at 90 days, and our secondary outcome was FIT completion at 180 days.

Key Results

Overall, unadjusted mailed FIT return rates were similar among control vs. primer arms at 90 days (27% vs. 29%, p = 0.11). Our adjusted analysis found a primer postcard did not increase FIT completion compared to mailed FIT alone (OR 1.14 (0.94, 1.37)).

Conclusions

Though primers are often a standard part of mailed FIT programs, we did not find an increase in FIT completion with mailed postcard primers among Veterans. Given the overall low mailed FIT return rates, testing different ways to improve return rates is essential to improving CRC screening.

Supplementary Information:

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-023-08248-7.

KEY WORDS: population health, preventative health, cancer screening.

INTRODUCTION

Mailed FIT programs are an effective means to increase screening for colorectal cancer (CRC)—the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the USA.[1–4] Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is evidence-based and cost-effective for average-risk patients and can be completed at home.[5] Though FIT was utilized at the Veterans Heath Administration (VHA) prior to COVID-19, its importance grew as a result of disruptions in access to routine primary care visits and CRC screening procedures, such as colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, or CT colonography.[6] On March 18th, 2020, VHA issued new guidelines to defer non-urgent procedures as a means to conserve limited healthcare resources at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. This guidance also recommended the use of FIT for average-risk CRC screening.[6]

With growing interest in mailed FIT program implementation, strategies to optimize FIT kit return are an area of needed evaluation. A recent Center for Disease Control and Prevention–sponsored summit reviewed the optimal components of mailed FIT programs, and recommended the use of “primers,” or advance notifications prior to the delivery of a mailed FIT kit, to enhance FIT return.[2] Advance notification is suggested to serve as a cue to action and to promote a shift in readiness.[7,8] Despite widespread use of primers as a best practice for mailed FIT programs, limited controlled studies have evaluated their direct impact on FIT completion rates. Advanced notifications in the form of letters or phone calls have shown to increase the rate of FIT return between 4 and 9%.[2,9,10] However, these studies are over a decade old and may not reflect the rapid changes in communication in mailed materials. To date, there has been no evaluation of mailed FIT program components among Veterans. Strategies to improve FIT return rates may differ in Veterans as compared to non-Veterans, given higher burden of mental health conditions and substance use, greater racial and ethnic diversity, lower socioeconomic status, and greater rurality.[11] It is not known whether a primer is more effective than the “just-in-time” notification provided by the mailed FIT kit among Veterans.

Given strong operational interest in identifying strategies to optimize a mailed FIT program to improve population health during the COVID pandemic, our team leveraged a learning health system (LHS) infrastructure within our regional VHA network to conduct a rigorous evaluation of primer effectiveness. Our local LHS infrastructure capitalizes on formalized operational-research partnerships to provide rapid feedback to the health system, with potential to scale results into larger VHA-wide efforts. To evaluate the evidence gap about primer effectiveness in Veteran populations in a contemporary setting, we conducted a pragmatic, prospective randomized quality improvement trial to address whether primers are an effective tool to improve FIT kit return rates among Veterans eligible for CRC screening. Given operational interest in primers, our team designed a trial to examine the effectiveness of written primer postcards. In this study, we randomized patients to either a written postcard primer with mailed FIT kit versus standard mailed FIT kit alone. Our aim was to assess the effectiveness of written primers on the rate of return for mailed FIT among Veterans.

METHODS

We conducted a prospective, randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of an advance notification primer postcard for return rates for FIT for CRC screening. This study was conducted at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, an integrated regional network serving 112,000 Veterans through two hospital-affiliated clinics and seven community-based clinics. Patient eligibility, demographics, and outcomes were obtained from electronic databases within the VHA corporate data warehouse.[12] Veteran characteristics evaluated included age (years), sex (male/female), marital status (yes/no), race/ethnicity (Alaska Native/Native American, Asian/Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, Hispanic, Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic White, Multiple/Other), neighborhood socioeconomic status (measured by decile of population, where lower decile is associated with increased all-cause mortality),[13] Gagne comorbidity score (< 0 to > 9, with increased scores corresponding to increased risk of one year mortality),[14] rurality (urban, rural, highly rural), utilization of healthcare visits (from within the last 12 months), and prior FIT screening status (FIT return in the prior 5 years).

Our study was completed as non-research quality improvement for evaluation of primary care operations under the designation of the VHA Office of Primary Care, and was therefore not subject to IRB review nor exemption. This trial was prospectively registered under Clinical Trials (NCT04923646).[15]

Participants—Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

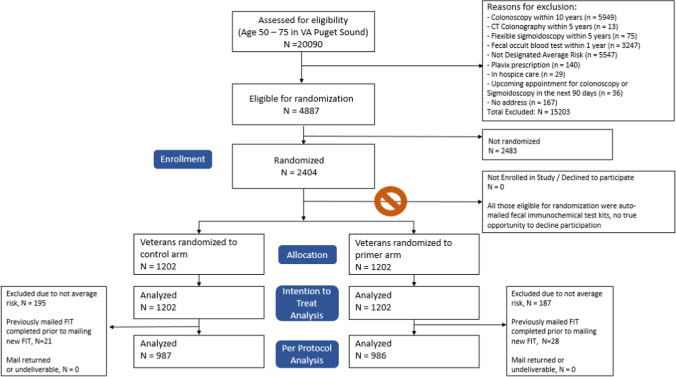

Eligibility requirements included age 50–75 years as of June 7 2021, enrolled with primary care, and with at least 1 outpatient visit in the past 2 years at VA Puget Sound (n = 20,090) (Fig. 1, consort). Patients were excluded if they lacked a mailing address (n = 167), were up to date with appropriate prior CRC screening (n = 9284), were not average-risk for CRC according to VHA guidelines (n = 5547), were newly prescribed clopidogrel within the last 6 months (n = 140), were enrolled in hospice (n = 29), or were already scheduled for upcoming colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy within 90 days (n = 36). Patients who had a prescription for clopidogrel within the last 180 days, but not in the prior 180–365 days, were considered newly prescribed clopidogrel. These patients were excluded because they may be unable to undergo a diagnostic colonoscopy in the recommended timeframe should their FIT return positive. A total of 4887 patients were eligible for inclusion.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram.

After completing the trial, it was recognized that a key exclusion criterion for greater than average risk (i.e., chart designation of “not average risk” entered by a provider for clinical reasons such as active symptoms, history of prior abnormal screening, personal risk factors, or family history) was missing, and after correction, this led to the further exclusion of 382 patients. This post-randomization change was unlikely to affect the results of the study due to equal impact on both arms, but we describe this for completion.

Intervention

This study occurred in the setting of a wider VHA effort to expand a mailed FIT program (Supplemental Fig. 1). Briefly, patients assigned to the intervention arm were mailed a postcard primer 2 weeks prior to being mailed a FIT kit. The postcard primer included messaging that they were due for screening, the benefits, and the process for returning a mailed FIT, along with primary care team contact information for questions (Supplemental Fig. 2). Those assigned to the control arm received a mailed FIT without a primer postcard. All FIT kits were mailed with an introductory letter, instructions on how to complete the test, and a pre-paid return mailer envelope. FIT kits were identical between trial arms. Materials were based on those previously published by Kaiser Permanente[16] and used clear simple messaging. A primary care clinic Veteran patient advisory board provided feedback on the content of the postcard primer.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the FIT return rate at 90 days post-randomization. Our secondary outcome was the FIT return rate at 180 days post-randomization.

Statistical Analysis

Annual CRC screening via FIT occurs in 43% of Veterans offered this screening at our facility, based on available administrative data in 2021. The trial was statistically powered to detect a 6% absolute difference from 43% for each group, with 80% power and 5% two-sided significance level. Based on these parameters, a sample size of 2404 patients was calculated, allowing for 10% attrition. We powered this pragmatic trial to detect a 6% difference, which is towards the median of available literature that suggests an expected increase FIT completion between 4 and 9%.[2,10]

From the eligible patient pool, 2404 patients were selected and then randomized in a 1:1 allocation to the intervention or control arm using permuted block randomization (with random block sizes of 4 and 8).[17] No blinding was applied and patients were not notified of their enrollment in the trial.

We used chi-square and Student’s t-test, as appropriate, to compare characteristics between individuals who completed FIT and those that did not. We used multivariable logistic regression models to assess the outcomes of interest. For increased precision, we a priori adjusted models for patient age, sex (male/female), race and ethnicity (American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, Hispanic, Multi-Race, Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic White, Other)[18], rurality (urban/rural), Gagne comorbidity index[14], SES[13], and prior history of FIT completion within past 5 years.

The intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses examined the association between randomization group and FIT return. The per-protocol (PP) analysis excluded Veterans whose FIT were undeliverable and returned by the post office, and those who returned a FIT after eligibility data was obtained but prior to randomization. Additional, exploratory subgroup analysis was done to assess the impact of primers among patients who did and did not have a prior history of FIT testing within the last 5 years. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.1.[19]

RESULTS

A total of 2404 patients were randomized, with 1202 patients in each arm. Overall, participants were mostly male (89%) and non-Hispanic White (70%) with an average age of 64.0 (SD 7.5) years old. Approximately half (48%) had previously completed a FIT within the last 5 years. Patient characteristics were well balanced between the intervention and control arms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Baseline

| Randomized group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Overall, N = 24041 | Control, N = 12021 | Primer, N = 12021 |

| Age (years) | 64.38 (7.47) | 64.41 (7.53) | 64.36 (7.41) |

| Sex (%) | |||

| Female | 256 (11%) | 135 (11%) | 121 (10%) |

| Male | 2148 (89%) | 1067 (89%) | 1081 (90%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 27 (1.2%) | 13 (1.1%) | 14 (1.2%) |

| Asian/Pac Islander/Native Hawaiian | 114 (4.9%) | 57 (4.9%) | 57 (4.9%) |

| Hispanic | 93 (4.0%) | 48 (4.1%) | 45 (3.9%) |

| Multi-race | 56 (2.4%) | 27 (2.3%) | 29 (2.5%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 401 (17%) | 189 (16%) | 212 (18%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1,642 (70%) | 837 (71%) | 805 (69%) |

| Other | 4 (0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| Marital status (%) | |||

| Married | 1105 (46%) | 564 (47%) | 541 (45%) |

| Prior FIT screen in last 5 years (Y) | 1144 (48%) | 568 (47%) | 576 (48%) |

| > 2 primary care visits in the past 12 months (Y) | 1686 (71%) | 838 (70%) | 848 (71%) |

| Number of ED visits in the past 12 months | 0.34 (1.01) | 0.33 (1.07) | 0.35 (0.94) |

| Gagne score | 0.47 (1.32) | 0.48 (1.35) | 0.46 (1.30) |

| Socioeconomic status index (decile) | |||

| 0 | 45 (2.1%) | 24 (2.2%) | 21 (2.0%) |

| 1 | 123 (5.7%) | 63 (5.9%) | 60 (5.6%) |

| 2 | 240 (11%) | 124 (12%) | 116 (11%) |

| 3 | 215 (10.0%) | 99 (9.2%) | 116 (11%) |

| 4 | 262 (12%) | 135 (13%) | 127 (12%) |

| 5 | 260 (12%) | 141 (13%) | 119 (11%) |

| 6 | 303 (14%) | 147 (14%) | 156 (14%) |

| 7 | 265 (12%) | 128 (12%) | 137 (13%) |

| 8 | 222 (10%) | 115 (11%) | 107 (9.9%) |

| 9 | 217 (10%) | 100 (9.3%) | 117 (11%) |

| Rurality (%) | |||

| Urban | 1794 (76%) | 898 (76%) | 896 (76%) |

| Rural | 518 (22%) | 255 (22%) | 263 (22%) |

| Highly rural/insular islands | 44 (1.9%) | 24 (2.0%) | 20 (1.7%) |

1Mean (SD); n (%)

Unadjusted rates and adjusted odds ratios of FIT return at 90 and 180 days are shown in Table 2. In the unadjusted analysis of FIT return at 90 days, mailed FIT return rates were similar among control vs. primer groups in the ITT (27% vs. 29%, p = 0.11) and PP (32% vs. 35%) analysis. In the adjusted analysis, a primer postcard did not increase FIT completion compared to mailed FIT alone (OR 1.14 (0.94, 1.37)). Similarly, in the unadjusted ITT and PP analysis of FIT return at 180 days, mailed FIT return rates were similar among control vs. primer groups. In the adjusted model, we observed a slightly higher odds of FIT return among the primer group that was not statically significant. Our exploratory subgroup analysis among individuals with and without prior FIT completion in the last 5 years found a significant increase in FIT return at 180 days among those who previously completed FIT and received a primer (OR 1.48, (1.02, 2.14)) in the unadjusted model, but the adjusted model did not reach statistical significance (OR 1.44, (0.99, 2.11)) (Supplemental Table 1a). There was no significant difference in FIT return at 90 days in the adjusted and unadjusted subgroup analysis (Supplemental Table 1a).

Table 2.

FIT Return Rates and Odds Ratios for the Control and Intervention Group at 90 and 180 Days

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to treat | Control, N = 12021 | Primer, N = 12021 | p-value2 | OR | 95% CI |

| FIT returned at 90 days | 319 (27%) | 354 (29%) | 0.11 | 1.14 | (0.94, 1.37) |

| FIT returned at 180 days | 349 (29%) | 385 (32%) | 0.11 | 1.14 | (0.94, 1.37) |

| Per-protocol | Control, N = 9861 | Primer, N = 9871 | p-value2 | OR | 95% CI |

| FIT returned at 90 days | 314 (32%) | 345 (35%) | 0.14 | 1.13 | (0.93, 1.38) |

| FIT returned at 180 days | 344 (35%) | 376 (38%) | 0.14 | 1.14 | (0.94, 1.38) |

1n (%)

2Pearson’s chi-squared test

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

DISCUSSION

Mailed FIT programs provide a population health strategy to increase access to needed CRC screening,[2] but advanced notification strategies to maximize return rates have not been independently studied among Veterans. We observed no significant difference in the FIT return rate among Veterans receiving a postcard primer prior to a mailed FIT, at either 90 or 180 days. In a subgroup analysis of patients with or without prior exposure to FIT, rates of return were not significantly different. Our findings add evidence to the literature on the effectiveness of advanced notifications as a strategy to enhance mailed FIT return. Our results suggest that a mailed postcard primer may not improve FIT return rates beyond the just-in-time information provided in standard mailed FIT program. This is important as primary care clinics with limited resources often encounter logistical barriers to implementing mailed primer postcards. We undertook this effort in partnership with our local VA operational team to better understand these challenges.

Our results that primers did not improve CRC return rates differ from prior evidence.[9] Prior studies, however, have shown heterogenicity in success by primer modalities.[7,8,20–25] Studies of written-material primers, specifically, were conducted over a decade ago, and only one study was conducted in the USA.[7,8,20,20,21] Since these studies were published, the US postal service has faced a major decline in the subsequent decade and mailed postcards may easily get thrown out as junk mail, increasing the chances that patients may not see this intervention.[26] In using a mailed postcard, we are unable to confirm that even a received primer is actually read; for example, the Veteran may relocate and not update their address on file or may discard the mail. Additionally, mobile phones have become ubiquitous. Primer strategies that use phone or text-based messages may be more effective and engaging to improve FIT return rates, especially if the call or text is answered.[22–25] We also only tested one version of the primer postcard, and it is possible alternative language could be more impactful, though notably we modeled our primer on those in use by other health care systems (i.e., Kaiser) and used patient feedback from a clinic patient advisory board in developing and vetting our primer. Lastly, our trial among Veterans engaged in care (i.e., at least one visit within the last year) also may have affected the impact of primers. Some have suggested that primers may be more effective among populations with less engagement in care (i.e., previously unscreened populations or those without regular care visits).[22] However, in our exploratory subgroup analysis we did not see this. In fact, our unadjusted analysis at 180 days suggests primers were more effective among those with prior FIT experience. Our findings may highlight that simple nudges via primers may be less effective among those who are less engaged or have little experience with FIT.[27]

We also note the significance of this trial being conducted a year into the COVID-19 pandemic. It is well documented that overall cancer screening rates dropped during the pandemic,[27]during which time CRC screening via procedural methods was less accessible. This context may have impacted our mailed FIT program as many patients did not seek in-person health services and accessed their primary care providers via virtual means.[28] This, when combined with reduced procedural access, may have reduced general screening discussions. However, because our trial was randomized, we believe these impacts would have been evenly distributed.

Our study has several limitations. Our pragmatic trial may be underpowered; for example, in some systems even a 2% increase in FIT return rates may be clinically meaningful.[29] Our selection to detect a 6% difference (i.e., mailing 16 primer postcards would lead to one additional FIT kit returned) as the basis for our sample size was based on the median seen in other similar trials[2,10] and pragmatic considerations with our operational partners including available population and facility resources. However, if a system assumes that mailing 50 postcards will lead to one additional FIT kit returned (i.e., a 2% absolute increase), then low-effort, low-cost interventions such as a primer postcard, text, or automated phone call may be felt to be reasonable investments. Future trials, particularly comparative effectiveness of varying modalities, among patient subgroups differing by engagement in care, and inclusion of formal cost-effectiveness analysis would be helpful in expanding the evidence around primers for health systems to optimize mailed FIT programs. Other limitations include the use of administrative data to identify eligible Veterans, which may lead to some number of greater than average-risk patients being included and may not capture Veterans who completed CRC screening outside the VHA. However, we anticipate these rates would be balanced between the randomized arms. Our study also examined mailed postcard primers among Veterans, which may not be generalizable to populations outside the VHA. Lastly, our trial was conducted at a single VA medical center, with higher baseline FIT use and rural community clinics; thus, results may differ at other VA sites across the country.

While our trial findings did not find evidence of overall benefit of our mailed postcard primer strategy for FIT return, this program was notable in its context and implementation. This work builds on VHA’s efforts and longstanding experience in using a learning health system (LHS) approach to improve and generate timely evidence benefitting patient care[30]. A LHS strives to learn and adapt practices based on rapidly acquired evidence from research-operational partnerships. Our team successfully facilitated a large, rigorously conducted, pragmatic randomized trial aligned with a system-level operational priority to address disruptions in CRC screening caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The trial adhered to operationally responsive timelines, with findings that directly informed care delivery in a large integrated system. The negative study results are important as they help to avoid expending resources on ineffective interventions and prompt efforts to find more effective means to bolster screening participation.

CONCLUSIONS

In our study, a written primer postcard did not significantly increase mailed FIT return rates among average-risk Veterans enrolled in primary care at a regional, integrated, tertiary VHA facility. More work is needed to evaluate the key components of a mailed FIT program, including the modality and optimal population for primers. Finally, this trial illustrates the application of a learning health system approach to rigorously evaluate operational projects to promote tailored interventions for the Veteran population.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

This work was made possible through operational support and funding from VA Puget Sound Health Care System Leadership. Additionally, this work was funded by the Primary Care Analytics Team through the Veterans Health Administration Office of Primary Care. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the US government, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the University of Washington.

Declarations:

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2020 submission data (1999–2018): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz. Accessed 30 June 2022.

- 2.Gupta S, Coronado GD, Argenbright K, et al. Mailed Fecal Immunochemical Test Outreach for Colorectal Cancer Screening: Summary of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-Sponsored summit. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(4):283-298. 10.3322/caac.21615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Dougherty MK, Brenner AT, Crockett SD, et al. Evaluation of Interventions Intended to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in the United States: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1645-1658. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Jager M, Demb J, Asghar A, et al. Mailed Outreach Is Superior to Usual Care Alone for Colorectal Cancer Screening in the USA: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(9):2489-2496. 10.1007/s10620-019-05587-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement | Cancer Screening, Prevention, Control | JAMA | JAMA Network. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2779985. Accessed 13 Jan 2022.

- 6.Gawron AJ, Kaltenbach T, Dominitz JA. The Impact of the Coronavirus Disease-19 Pandemic on Access to Endoscopy Procedures in the VA Healthcare System. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(4):1216-1220.e1. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Cole SR, Smith A, Wilson C, Turnbull D, Esterman A, Young GP. An Advance Notification Letter Increases Participation in Colorectal Cancer Screening. J Med Screen. 2007;14(2):73-75. 10.1258/096914107781261927. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Libby G, Bray J, Champion J, et al. Pre-notification Increases Uptake of Colorectal Cancer Screening in All Demographic Groups: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Screen. 2011;18(1):24-29. 10.1258/jms.2011.011002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Issaka RB, Avila P, Whitaker E, Bent S, Somsouk M. Population Health Interventions to Improve Colorectal Cancer Screening by Fecal Immunochemical Tests: a Systematic Review. Prev Med. 2019;118:113-121. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Goodwin BC, Ireland MJ, March S, et al. Strategies for Increasing Participation in Mail-Out Colorectal Cancer Screening Programs: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):257. 10.1186/s13643-019-1170-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Hebert PL, Batten AS, Gunnink E, et al. Reliance on Medicare Providers by Veterans after Becoming Age-Eligible for Medicare Is Associated with the Use of More Outpatient Services. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(Suppl 3):5159–5180. 10.1111/1475-6773.13033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Price LE, Shea K, Gephart S. The Veterans Affairs’s Corporate Data Warehouse: Uses and Implications for Nursing Research and Practice. Nurs Adm Q. 2015;39(4):311-318. 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Nelson K, Schwartz G, Hernandez S, Simonetti J, Curtis I, Fihn SD. The Association Between Neighborhood Environment and Mortality: Results from a National Study of Veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):416-422. 10.1007/s11606-016-3905-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. A Combined Comorbidity Score Predicted Mortality in Elderly Patients Better than Existing Scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):749-759. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Schuttner L. Primers to Improve Adherence to Annual CRC Screening Among Veterans: A Randomized Control Trial. clinicaltrials.gov; 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04923646. Accessed 12 Jan 2022.

- 16.Mailed FIT Outreach for Colorectal Cancer Screening Materials. Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research. https://research.kpchr.org/mailed-fit/Materials. Accessed 9 June 2022.

- 17.Snow G. Blockrand: Randomization for Block Random Clinical Trials. Published online April 6, 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=blockrand. Accessed 21 April 2022.

- 18.Hernandez S, Sylling P, Mor M, et al. Developing an Algorithm for Combining Race and Ethnicity Data Sources in the Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2019;185. 10.1093/milmed/usz322. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.R Core Team (2020). — European Environment Agency. https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/oxygen-consuming-substances-in-rivers/r-development-core-team-2006. Accessed 21 April 2022.

- 20.Senore C, Ederle A, DePretis G, et al. Invitation Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening Programmes: the Impact of an Advance Notification Letter. Prev Med. 2015;73:106-111. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.van Roon AHC, Hol L, Wilschut JA, et al. Advance Notification Letters Increase Adherence in Colorectal Cancer Screening: a Population-Based Randomized Trial. Prev Med. 2011;52(6):448-451. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Kempe KL, Shetterly SM, France EK, Levin TR. Automated phone and mail population outreach to promote colorectal cancer screening. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(7):370-378. [PubMed]

- 23.Lee B, Patel S, Rachocki C, et al. Advanced Notification Calls Prior to Mailed Fecal Immunochemical Test in Previously Screened Patients: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):2858-2864. 10.1007/s11606-020-06009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Huf SW, Asch DA, Volpp KG, Reitz C, Mehta SJ. Text Messaging and Opt-out Mailed Outreach in Colorectal Cancer Screening: a Randomized Clinical Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(7):1958-1964. 10.1007/s11606-020-06415-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Coronado GD, Nyongesa DB, Petrik AF, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Advance Notification Phone Calls vs Text Messages Prior to Mailed Fecal Test Outreach. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(11):2353-2360.e2. 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.New business plan charts path to financial stability. https://about.usps.com/news/national-releases/2012/pr12_029.htm. Accessed 30 June 2022.

- 27.Sunstein CR. Nudges that fail. Behav Public Policy. 2017;1(1):4-25. 10.1017/bpp.2016.3.

- 28.Teglia F, Angelini M, Astolfi L, Casolari G, Boffetta P. Global Association of COVID-19 Pandemic Measures With Cancer Screening: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(9):1287-1293. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Reddy A, Gunnink E, Deeds SA, et al. A Rapid Mobilization of “Virtual” Primary Care Services in Response to COVID-19 at Veterans Health Administration. Healthc Amst Neth. 2020;8(4):100464. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2020.100464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Halpern SD, Karlawish JHT, Berlin JA. The Continuing Unethical Conduct of Underpowered Clinical Trials. JAMA. 2002;288(3):358-362. 10.1001/jama.288.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Greene SM, Reid RJ, Larson EB. Implementing the Learning Health System: from Concept to Action. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(3):207-210. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00012. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.