Abstract

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated an exclusively virtual 2021 residency application cycle. We hypothesized that residency programs’ online presence would have increased utility and influence for applicants.

Methods

Substantial surgery residency website modifications were undertaken in the summer of 2020. Page views were gathered by our institution’s information technology office for comparison across years and programs. An anonymous, voluntary, online survey was sent to all interviewed applicants for our 2021 general surgery program match. Five-point Likert-scale questions evaluated applicants’ perspective on the online experience.

Results

Our residency website received 10,650 page views in 2019 and 12,688 in 2020 (P = 0.14). Page views increased with a greater margin compared to a different specialty residency program’s (P < 0.01). From 108 interviewees, 75 completed the survey (69.4%). Respondents indicated our website was satisfactory or very satisfactory compared to other programs (83.9%), and none found it unsatisfactory. Applicants overall stated our institution’s online presence impacted their decision to interview (51.6%). Programs’ online presence impacted the decision to interview for nonWhite applicants (68%) but significantly less for white applicants (31%, P < 0.03). We observed a trend that those with fewer than this cohort’s median interviews (17 or less) put more weight on online presence (65%), compared to those with 18 or greater interviews (35%).

Conclusions

Applicants utilized program websites more during the 2021 virtual application cycle; our data show most applicants depend on institutions’ websites to supplement their decision-making; however, there are subgroup differences in the influence online presence has on applicant decisions. Efforts to enhance residency webpages and online resources for candidates may positively influence prospective surgical trainees, and especially those underrepresented in medicine, to decide to interview.

Keywords: Applicant perspective, General surgery residency, Online presence, Residency match

Introduction

Medical school clinical clerkships grant students exposure to almost all specialties so that students may make informed career choices; students are able to interact with current faculty and residents, interview the specific patient population that specialty treats, and have the opportunity for mentorship in pursuit of the residency of their choosing.1 The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted traditional clerkship rotations, away rotation opportunities, and in-person interviews for residency training programs. Historically, 59% of fourth-year medical students reported doing an away rotation, and 53% of students reported changing their ranking of residency programs based on these in-person rotations. Prospective residents during the pandemic however, have had to depend on impressions from program websites, email communications, and social media.2

Many residency programs have taken steps to adapt to the virtual world that was necessary in the wake of the pandemic. Across multiple residency programs, social media use greatly increased by as much as 170%.1 , 3, 4, 5 Almost one-third of all social media accounts for pediatric residencies were started after March 1, 2020, with this increase suspected to be a result of COVID-19.3 Programs were required to expand opportunities for applicant engagement through online portals, such as virtual open houses, virtual tours, and question forums.6 Some residency programs are utilizing social media to not only contact future applicants but to also help “brand” their programs.6

Transitioning to virtual platforms has not only affected how residency programs interact with applicants but has altered the information or saliency of an impression programs make on applicants. There is a positive correlation between the presence of a social media account and a higher Doximity ranking found in orthopedic residency programs; Doximity ranks programs on several metrics and is used by many medical students during the ranking process.5 , 7 In addition, 80% of emergency medicine residents said that a program’s website was an influential factor for them applying to that given program.2 There is high variability in medical and surgical programs’ websites, the detail of information provided, and the accuracy of the content.2 The resources spent on online presence are not a corollary to the quality of a program. Significant gaps in content most valued by applicants is concerning and opens the process up to possible bias; well-funded university programs with substantial web support and/or branding staff may have a more polished website than others.2

Daniels et al. suggested programs focus webpages on more applicant-relevant content, such as frequently asked questions.2 With increased social media access, programs can better represent a typical day in the life of a resident, have hospital or city tours, and host Q&A sessions to help give applicants and interested parties a more personal understanding of the program. These opportunities are important for applicants, but they are also important for program directors to help determine who is a good fit.3 Recent literature has studied how residency programs have adapted to the virtual setting, but we sought to better evaluate how these efforts were perceived by the general surgery applicant.

With the obsoletion of away rotations and full transition to virtual interviews, we hypothesized that residency programs’ online presence would have an increased impact and utility in applicants’ decisions regarding the general surgery residency application match.

Methods

The general surgery webpage at our institution was reviewed, and multiple opportunities for improvement were identified. Specifically, we opted to focus on removing out-of-date information, improving navigability, spotlighting residents and faculty as individuals with photographs and biographies, and displaying our nondiscrimination statement and commitment to diversity. Additional resident information was sought, a resident-organized and directed campus tour video was completed, and multiple faculty introductions were filmed for a welcome informational video.

Page view is an automated data point captured by our institution’s information technology office and was captured when any user on the internet navigated to our webpage. An investigator-generated survey was sent to all 108 candidates interviewed for a categorical general surgery position at our institution. The survey was hosted inResearch Electronic Data Capture, a secure, web-based software platform. The survey asked participants to self-report demographic information, and then answer several questions about the number of interviews they were offered and completed. The full list of questions can be seen in Table 1 . The survey concluded with internal quality assessment for our program’s unique virtual interview day strengths and weaknesses.

Table 1.

The survey.

| 1. Participant variable | |||||||

| 2. Age | |||||||

| 3. Gender | Female | Male | Non-binary | Prefer not to say | |||

| 4. Race | American Indian/Alaskan Native | Asian | Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | Black or African American | White | More than one race | Unknown/Not reported |

| 5. Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | NOT Hispanic or Latino | Unknown/Not reported | ||||

| 6. When was your Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) interview date? | |||||||

| 7. What number interview is this for you? | |||||||

| 8. How many interviews have you accepted at this time? | |||||||

| 9. Did MUSC’s online presence (website, social media, etc) impact your decision to apply and interview here? | Yes | No | |||||

| 10. Compared to other programs, how would you rate MUSC’s online presence? | Very unsatisfactory | Unsatisfactory | Neutral | Satisfactory | Very satisfactory | ||

Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Captureelectronic data capture tools. This study was deemed exempt from review by the institutional review board. We present descriptive data in tables and graphs. Analysis was determined based on the underlying distribution. For normally distributed variables, means with standard deviations are presented; for non-normally distributed variables, medians, and interquartile ranges are presented. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare continuous covariates between groups. The chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Data were analyzed using the R statistical software version 4.2.2 (R core Team 2015, Vienna, Austria).

Results

75 of the 108 candidates completed the investigator-generated survey with a response rate of 69.4%. The median age was 27, and 53% of respondents were male (n = 40). 77.3% self-identified as white versus non-White, which does not accurately represent our more diverse interview pool. The median interviews accepted by these applicants was 17 (range 2-40).

Candidates reported our website was satisfactory or very satisfactory compared to other programs’ pages (83.9%), and none found it unsatisfactory. Most applicants stated our institution’s online presence impacted their decisions to interview (51.6%).

The Department of Surgery residency webpage at our institution saw a statistically significant increase in page views after our website modifications in summer of 2020 (P < 0.01). Compared with the anesthesia residency landing page, who have a similar number of trainees and interviewees, the surgery webpage had significantly more views in 2020 (10,650 in 2019 to 12,688 in 2020 compared with anesthesia 10,305 in 2019 and 9595 in 2020) (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

The surgery residency program website page views by year compared with the anesthesia program’s page views by year. Surgery’s website page views were higher than anesthesia’s both in 2019 (P < 0.6) and 2020 (P < 0.002).

Page view data were examined by month, and similar temporal trends were noted for multiple residency programs at our institution, including obstetrics/gynecology, otolaryngology, and anesthesia. Page view trends over time, month-by-month demonstrated a spike in the September and October months (Fig. 2 ). Other webpages that are less directly tied to the residency application process, such as the fellowship page and the general medical education page at our institution, did not see the same magnitude of temporal spike.

Fig. 2.

Webpage viewership varied by month for residency pages, indicating a substantial temporal relationship when applicants navigate to program webpages. (A) Depicts surgery compared to anesthesia, surgery fellowship, and general medical education webpages in 2020. (B) Depicts 2019 compared with 2020 webpage views for the residency landing webpages of surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, and otolaryngology. Surgery’s page view was higher than obstetrics and gynecology in 2019 (P < 0.001) and 2020 (P < 0.001). Surgery’s page view was higher than otolaryngologyin 2019 (P < 0.001) and 2020 (P < 0.001).

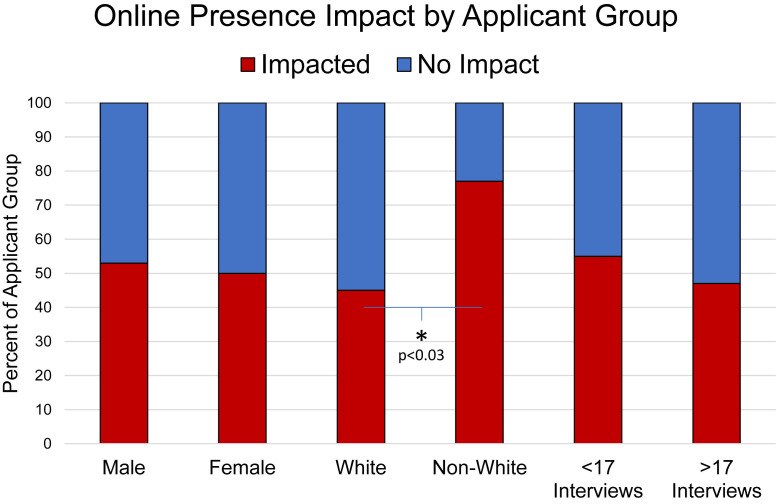

We appreciated a trend that males were more impacted by the program’s online presence than females (P = 0.053) (Fig. 3 ). White applicants found the online presence of a program of decreased influence compared to non-White applicants (45% versus 77%, P < 0.03). A trend was also observed that students with fewer interviews were more likely to be impacted by online presence (P = 0.4) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The self-reported yes/no if online presence impacted applicants’ decision to interview with a program by sex, race, and if they had more or less than the median number of interviews in our cohort. Males were more impacted than females (P = 0.053). White applicants indicated a decreased influence compared to non-White applicants (45% versus 77%, P < 0.03). Students with fewer interviews were more likely to be impacted (P = 0.4).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that surgery applicants navigated to program websites more during the 2021 virtual application cycle than in prior years. Despite program websites historically being used by applicants, it seems they are of increased importance and utility during an application cycle when travel and in-person interviews are restricted. The virtualization of interviews along with multiple other factors, not able to be assessed by this study, contributed to this trend in applicant behaviors. Our survey data reveals applicants depend on institutions’ websites to supplement their decision-making. In a virtual setting, the quality and quantity of the information gathered from programs’ websites hold more power than during in-person traditional application cycles. Salient in-person experiences can allow more robust portrayals of hospital systems, facilities, faculty, staff, and residents. Efforts must be taken to translate those cultural subtleties to a virtual platform that can communicate to remote applicants. To be useful, the social media accounts and websites should be active, up-to-date, and provide responses to frequently asked or sought-after information to help prospective residents.5

Lee et al. recently recommended that individual programs survey whether their virtual platforms enhanced their recruitment efforts and brought in more applicants with diverse backgrounds.4 Our data found that the non-White subpopulation of applicants was more influenced by online program information. To increase diversity in our surgical trainees, it is crucial to understand how to best engage non-White, under-represented minority applicants. This finding describes an exciting opportunity to further recruit this subpopulation. By measuring the effectiveness and influence of virtual platforms, programs can tailor their websites and accounts to increase engagement scores.

Diversity makes an institution better equipped to serve all members of the community by creating an atmosphere of inclusivity and representation. Studies have shown that not only are patients from minority groups more comfortable with a diverse medical team, but some health disparities can be mitigated with race concordant care-providers.8, 9, 10 Unfortunately, thus far efforts have fallen short; minority groups are still underrepresented in different areas of medicine, especially in residency programs and especially in surgical subspecialties.8 , 10, 11, 12 In plastic surgery residency, for example, both Hispanics and African Americans are underrepresented when compared to Whites and Asians.8 When transitioning to a virtual setting, residency programs can garner their online presence to demonstrate the diversity of their residency and faculty cohorts. One of the revisions made to our surgical residency program website included showcasing the department’s diversity, equity, and inclusion mission statement, 5-y plan, team, and calendar of events. Displaying these commitments may help diminish the gap in representation, as was accomplished with women’s representation in plastic surgery residency programs.11 Among general surgery residency programs, some websites featured elements that displayed the program’s dedication to promoting a diverse and inclusive environment through formal statements about policies, photos of residents and applicants, and extended resident or faculty biographies.12 It was found that these aspects of the website help explicitly demonstrate a program’s culture and dedication to diversity.12

Limitations to this study include its use of page views as a measure to compare applicant use of the Department of Surgery webpage. Comparison with our institution’s anesthesia, obstetrics and gynecology, and otolaryngology program pages (Fig. 3) was undertaken to minimize confounders; however, an increase in page views is multifactorial. Additionally, anonymous survey results demonstrated only increased impact, with no positive or negative association with the webpage experience.

Economic concerns and access to resources may limit what information applicants are exposed to through in-person travel, mentorship, and network connections. Our data suggests this can be combat by bolstering program webpages or social media platforms. This study, to our knowledge, is one of the first to demonstrate different communication preferences or influences by applicant subgroups, whether it demonstrates a positive or negative impact. It is important to understand how to best connect with different applicant subpopulations such that we do not fuel an exclusive or homogenous workforce. With these findings in mind, programs should take steps to improve their online presence. We also encourage programs track their effectiveness in increasing engagement and reaching under-represented minoritys; only through measuring the reach of interventions can we collectively determine which efforts reap the greatest results.

Conclusions

The virtual interview cycle brought increased residency website page views. Program updates and enhancements to the webpage were satisfactory to almost all applicants and had an impact on their decision to interview. Moreover, our results show these online updates significantly engage non-White applicants. Future studies to evaluate targeted interventions are encouraged to continue to attract diverse applicants.

Author Contributions

KQ designed, acquired, analyzed, interpreted, and drafted the study. KQ and BR drafted the work and revised it. RP provided statistical support and revisions. CT provided critical mentorship support and edits.

Disclosure

None declared.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2023.05.012.

Supplementary Materials

References

- 1.Haupt T.S., Dow T., Smyth M., et al. Medical student exposure to radiation oncology through the pre-clerkship residency exploration program (PREP): effect on career interest and understanding of radiation oncology. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35:388–394. doi: 10.1007/s13187-019-1477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang O.Y., Ruddell J.H., Hilliard R.W., Schiffman F.J., Daniels A.H. Improving the online presence of residency programs to ameliorate COVID-19’s impact on residency applications. Postgrad Med. 2021;133:404–408. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2021.1874195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pruett J.C., Deneen K., Turner H., et al. Social media changes in pediatric residency programs during COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21:1104–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee D.C., Kofskey A.M., Singh N.P., King T.W., Piennette P.D. Adaptations in anesthesiology residency programs amid the COVID-19 pandemic: virtual approaches to applicant recruitment. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:464. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02895-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malyavko A., Kim Y., Harmon T.G., et al. Utility of social media for recruitment by orthopaedic surgery residency programs. JB JS Open Access. 2021;6 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.21.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeAtkine A.B., Grayson J.W., Singh N.P., Nocera A.P., Rais-Bahrami S., Greene B.J. #ENT: otolaryngology residency programs create social media platforms to connect with applicants during COVID-19 pandemic. Ear Nose Throat J. 2023;102:35–39. doi: 10.1177/0145561320983205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doximity, Inc.; 2022. Doximity residency navigator.https://www.doximity.com/residency/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silvestre J., Serletti J.M., Chang B. Racial and ethnic diversity of U.S. Plastic surgery trainees. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saha S., Komaromy M., Koepsell T.D., Bindman A.B. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:997–1004. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.9.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao C., Dowzicky P., Colbert L., Roberts S., Kelz R.R. Race, gender, and language concordance in the care of surgical patients: a systematic review. Surgery. 2019;166:785–792. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2019.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parmeshwar N., Stuart E.R., Reid C.M., Oviedo P., Gosman A.A. Diversity in plastic surgery: trends in minority representation among applicants and residents. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:940–949. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driesen A.M., Arenas M.A., Arora T.K., et al. Do general surgery residency program websites feature diversity? J Surg Educ. 2020;77:e110–e115. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.