Abstract

Purpose

Dysphonia is a common symptom due to the coronavirus disease of the 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Nonetheless, it is often underestimated for its impact on human's health. We conducted this first study to investigate the global prevalence of COVID-related dysphonia as well as related clinical factors during acute COVID-19 infection, and after a mid- to long-term follow-up following the recovery.

Methods

Five electronic databases including PubMed, Embase, ScienceDirect, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science were systematically searched for relevant articles until Dec, 2022, and the reference of the enrolled studies were also reviewed. Dysphonia prevalence during and after COVID-19 infection, and voice-related clinical factors were analyzed; the random-effects model was adopted for meta-analysis. The one-study-removal method was used for sensitivity analysis. Publication bias was determined with funnel plots and Egger's tests.

Results

Twenty-one articles comprising 13,948 patients were identified. The weighted prevalence of COVID-related dysphonia during infection was 25.1 % (95 % CI: 14.9 to 39.0 %), and male was significantly associated with lower dysphonia prevalence (coefficients: −0.116, 95 % CI: −0.196 to −0.036; P = .004) during this period. Besides, after recovery, the weighted prevalence of COVID-related dysphonia declined to 17.1 % (95 % CI: 11.0 to 25.8 %). 20.1 % (95 % CI: 8.6 to 40.2 %) of the total patients experienced long-COVID dysphonia.

Conclusions

A quarter of the COVID-19 patients, especially female, suffered from voice impairment during infection, and approximately 70 % of these dysphonic patients kept experiencing long-lasting voice sequelae, which should be noticed by global physicians.

Keywords: COVID-19, Voice assessment, Dysphonia, Prevalence

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the coronavirus disease of the 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, many aspects of our lives have been profoundly influenced. COVID-19 could not only bring about short-term health impact, but may even pose a threat to the long-term quality of life, which could become a huge socioeconomic burden for the public [1,2]. With emerging evidence having proved that many symptoms and outcomes COVID-19 could contribute to [1], people have gradually understood the health impact during and after infection, as well as treatment against the disease.

A diversity of symptoms related to aerodigestive system could occur when infected with COVID-19 [3]. These include but are not limited to cough, dyspnea, sore throat, olfactory and gustatory dysfunction, etc. [[4], [5], [6]]. Voice impairment, or dysphonia, is one of the common symptoms in COVID-19 patients [7]; nonetheless, it could often be underestimated when discussed together with the rest of the above-mentioned symptoms due to it being relatively less emergent and life-threatening [8]. Being characterized as vocal functional changes, it could mostly be attributed to the immune response following the infection, and further lead to poor sound production [9]. Moreover, patients suffering from phonation difficulties might also experience less self-confidence, poorer communications with others, and eventually lower quality of life [10]. With many adverse outcomes, to understand the prevalence and relative risk factors of COVID-related dysphonia is therefore crucial for the worldwide clinicians and patients for early management and prevention.

Currently, there are several observational studies exploring the voice outcome with miscellaneous modalities in patients with COVID-19 [4,9]. However, there lacks synthesized data on the exact prevalence of COVID-related dysphonia. Moreover, as the pandemic persists with emerging long-lasting sequelae (at least three months from the onset of COVID-19, and with symptoms lasting for more than two months could be categorized as “long-COVID” per the definition of the World Health Organization [11]) following infection, it remains unclear whether this prevalence alters after the patients recover from the acute COVID-19 infection episode with a mid- to long-term follow-up, which could greatly influence the coping strategies for dysphonia and the length of probable treatment and rehabilitation. Being an important public health issue, our study therefore aims to investigate the global prevalence of COVID-related dysphonia and epidemiological risk factors during and after the acute infection, which might be expected to provide certain insights into this irritating health problem.

2. Material and methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline [12] was followed for this study. Besides, the study was registered to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO); the registration number was CRD42022383399.

2.1. Literature search and selection

Five electronic databases, including PubMed, Embase, ScienceDirect, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science were systematically searched by two of the authors (Y.H.W. and Y.E.L.) on Dec 15, 2022. The major keywords for searching were (“COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2”) AND (“voice impairment” OR “dysphonia” OR “aphonia”); a detailed searching strategy was presented in Supplemental Table 1. Literatures published between Dec, 2019 and Dec, 2022 were enrolled, and there was no language restriction on the enrolled articles. The references of the recruited literatures were also viewed for involvement if necessary. After removing duplicates, the two authors (Y.H.W. and Y.E.L.) independently screened the articles for eligibility, and enrolled the final eligible literature. The inclusion criteria were (i) articles of prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, and clinical trials; (ii) articles with abstract and full-text for critical appraisals; (iii) studies reporting dysphonia with a clear definition and/or diagnosis; and (iv) studies providing sufficient information and extractable data regarding the COVID-related dysphonia prevalence rate. The exclusion criteria were (i) studies with patients aged under 18; (ii) studies with populations mainly composed of occupational or frequent voice users; and (iii) studies not excluding dysphonia or voice complications prior to COVID-19 infection. Any inconsistency during the process was discussed with a third author (C.W.L.).

2.2. Data extraction

One author (C.W.L.) extracted the required data, which was cross-examined by the other two authors (Y.H.W. and Y.E.L.). The data included: (i) name of the first author and the publication year; (ii) country of the study; (iii) sample size; (iv) mean age of the subjects; (v) gender distribution of the subjects; (vi) percentage of smokers; (vii) major voice-related comorbidities (e.g. asthma, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (COPD), rhinitis, gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) / laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR)); (viii) modalities for dysphonia assessment; (ix) percentage of tracheostomy/intubation; (x) dysphonia prevalence during/after the acute COVID-19 infection period; and (xi) time to re-assessment of dysphonia (after recovery from the acute COVID-19 infection period).

2.3. Risk of bias assessment

Two authors (C.W.L. and T.Y.C.) independently assessed the risk of bias of the studies. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist [13] was adopted for determining the quality of the individual study. Any discrepancy was discussed with a third author (H.C.L.).

2.4. Data processing & statistical analysis

The percentage and 95 % confidence interval (CI) were adopted as the effect measurements of dysphonia prevalence rate. Due to the expected variation among different populations and the real-world settings, the random-effects model was more statistically appropriate and was adopted in this study. The proportion of heterogeneity was calculated with the I2 statistic.

In this study, we divided the patients into two parts for further meta-analysis and comparisons: (i) During acute COVID-19 infection; and (ii) Post COVID-19 infection, which was defined as most of the acute symptoms being relieved and recovery with clinical evidence (e.g. negative results of real-time polymerase chain reaction) that occurred mostly one month after the acute infection period [14]. Besides, in those grouped as “post COVID-19 infection”, we further performed subgroup analysis based on the follow-up period being at least 3 months (long-COVID) after recovery from COVID-19 as a long-term investigation for persistent voice sequelae.

To identify the heterogeneity across the enrolled studies, meta-regressions were used to analyze the impact of clinical factors, including mean age, gender, tracheostomy/intubation, and dysphonia assessment modalities (“objective with/without subjective means” versus “subjective means only”), on dysphonia prevalence. In this study, the dysphonia assessment modalities were defined and classified as objective means if the patients were evaluated either using fiberscope for detecting laryngeal vocal structure abnormality or standardized acoustic voice analysis [15,16]; and subjective means if the patients were assessed using non-instrumental techniques (e.g. clinicians' subjective judgement, patients' self-reported experience, and questionnaires). The one-study-removal method was used for the sensitivity analysis to detect potential outliers, and publication biases were analyzed with funnel plots and Egger's tests. A two-tailed P < .05 was considered to have significance. All of the analyses were conducted using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, version 3 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA).

3. Results

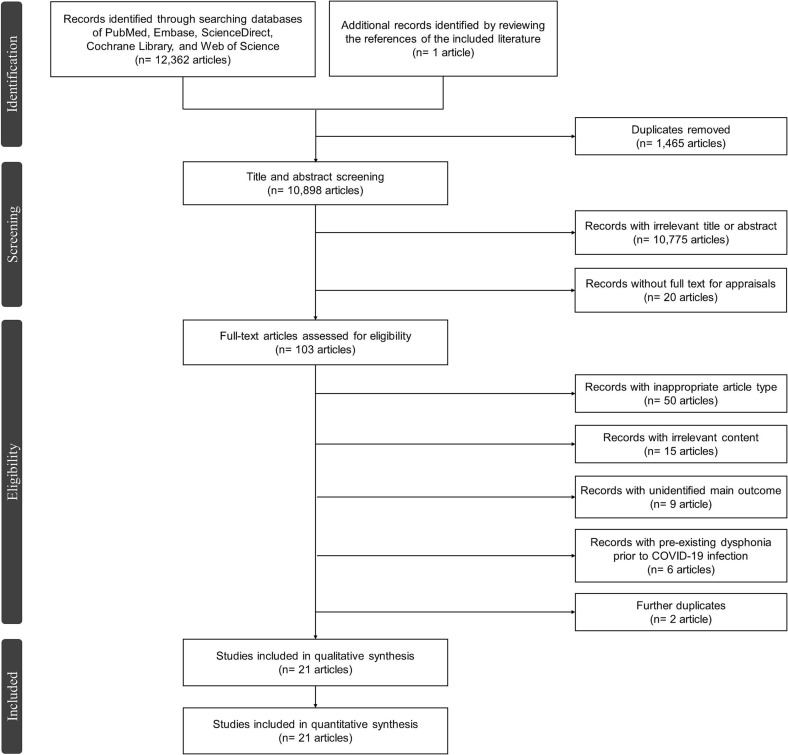

A total of 12,363 articles were collected after searching the databases and reviewing the references. Among these articles, 10,898 of them were screened following the duplicates removal, and 103 articles were later evaluated for eligibility after initial screening. Finally, twenty-one articles [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]] were included after the exclusion of ineligible literatures (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

The PRISMA flowchart of the literature selection process.

3.1. Characteristics of the studies

Among the twenty-one enrolled articles, 13,948 patients were identified (Supplemental Table 2).

In the “during COVID-19 infection” group, there were thirteen studies [17,[20], [21], [22], [23],[27], [28], [29], [30], [31],[35], [36], [37]] involving 12,913 patients. The prevalence of dysphonia during COVID-19 infection ranged from 0.04 to 82.1 %, and three of the studies [20,22,35] reported more than half of the patients experienced dysphonia during this period. In this group, the mean age ranged from 35.8 to 60.2 years [17,20,21,27,28,30,31,36,37], and the percentage of male patients ranged from 26.4 to 65.1 % [17,[20], [21], [22], [23],[27], [28], [29], [30], [31],36,37]. Besides, the percentage of smokers and tracheostomy/intubation ranged from 15.0 to 50.6 % and 0 to 100 %, separately [17,20,21,23,28,29,36,37]. As for the dysphonia assessment modalities, one study [20] used only objective means; another six studies [21,23,28,31,35,36] used only subjective means; while the rest of the six studies [17,22,27,29,30,37] adopted both.

In the “post COVID-19 infection” group, there were fourteen studies [[17], [18], [19],21,[24], [25], [26], [27],29,30,[32], [33], [34],36] encompassing 1716 patients. The prevalence of COVID-related dysphonia presenting as voice sequelae after recovery ranged from 3.8 to 71.6 %, and only one study [18] reported more than half of the patients (>50 %) suffering from post-COVID voice impairment; the follow-up periods were reported from one month to six months [[17], [18], [19],21,[24], [25], [26], [27],29,30,32,33,36]. In this group, the mean age ranged from 34.6 to 61.0 years [17,19,21,26,27,30,[32], [33], [34],36], and the percentage of male patients ranged from 31.3 to 75.0 % [17,19,21,24,25,27,29,30,[32], [33], [34],36]. Additionally, the percentage of smokers and tracheostomy/intubation ranged from 22.9 to 50.6 % [[17], [18], [19],21,24,29,36] and 0 to 100 % [[17], [18], [19],21,[24], [25], [26], [27],29,30,32,34], respectively. As for the dysphonia assessment modalities, one study [18] used only objective means; another eight studies [19,21,25,26,[32], [33], [34],36] used only subjective means; while the rest of the four studies [17,27,29,30] adopted both. The general risks of bias of the enrolled studies were not high (Supplemental Table 3). Ways to determine a powerful population size, individual study-based bias, and participant selection are subjects with higher bias, but it might be expected that the measured outcomes could only be influenced by these subjects to some minor extent based on the nature of the present epidemiological study type.

3.2. Results of meta-analysis

3.2.1. During COVID-19 infection

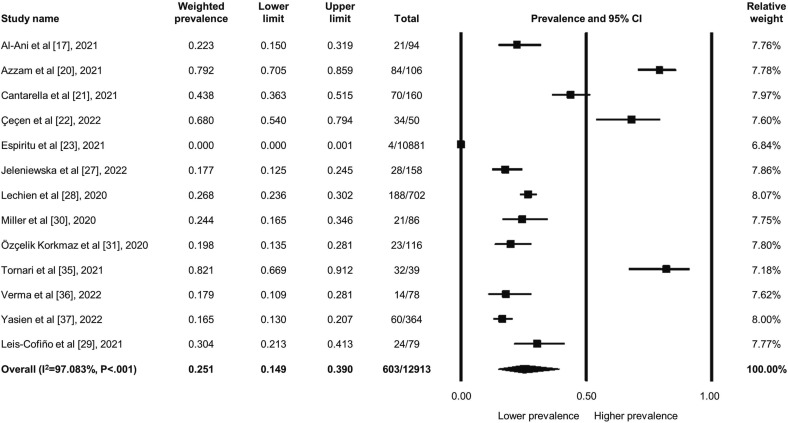

Among the 12,913 patients, 603 patients experienced new-onset dysphonia when infected with COVID-19; the weighted prevalence was 25.1 % (95 % CI: 14.9 to 39.0 %) (Fig. 2 ). The heterogeneity was high across the studies (I2 = 97.083, P < .001). However, the sensitivity analysis did not alter the main findings regarding the dysphonia prevalence. As for possible publication bias, though the funnel plot appeared asymmetrical (Supplemental Fig. 1), the insignificant results of the Egger's test did not reflect substantial bias (P = .889).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot regarding the weighted prevalence of COVID-related dysphonia in patients during acute infection.

The further meta-regression (Table 1 ) revealed that among the clinical covariates able to be calculated, male patients were correlated with a statistically lower dysphonia prevalence rate during COVID-19 infection (coefficients: −0.116, 95 % CI: −0.196 to −0.036; P = .004) compared to female; on the other hand, the rest of the clinical factors, including mean age, tracheostomy/intubation, and dysphonia assessment modalities, did not possess significant relationships with dysphonia prevalence. The covariates being analyzed altogether could explain 90.66 % of the heterogeneity.

Table 1.

Meta-regression among covariates and dysphonia prevalence in COVID-19 patients during infection period and after recovery.

| Covariate | Coefficient (95 % CI)a | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (year) | ||

| During infection [17,20,21,27,28,30,31,36,37] | 0.056 (−0.062, 0.175) | 0.352 |

| After recovery [17,19,21,26,27,30,[32], [33], [34],36] | −0.072 (−0.211, 0.067) | 0.307 |

| Gender (male; %) | ||

| During infection [17,[20], [21], [22], [23],[27], [28], [29], [30], [31],36,37] | −0.116 (−0.196, −0.036) | 0.004 |

| After recovery [17,19,21,24,25,27,29,30,[32], [33], [34],36] | −0.018 (−0.105, 0.070) | 0.693 |

| Tracheostomy/Intubation (%) | ||

| During infection [17,20,21,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31],35,37] | 0.021 (−0.001, 0.042) | 0.060 |

| After recovery [[17], [18], [19],21,[24], [25], [26], [27],29,30,32,34] | 0.019 (−0.008, 0.045) | 0.163 |

| Assessment methodb | ||

| During infection [17,[20], [21], [22], [23],[27], [28], [29], [30], [31],[35], [36], [37]] | −0.852 (−1.856, 0.153) | 0.097 |

| After recovery [[17], [18], [19],21,[25], [26], [27],29,30,[32], [33], [34],36] | −0.747 (−2.638, 1.143) | 0.439 |

Objective measurements were set to be the reference group.

CI = confidence interval.

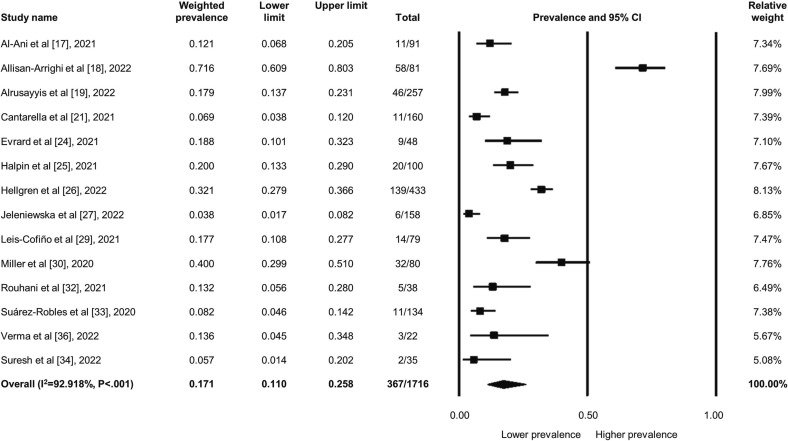

3.2.2. Post COVID-19 infection

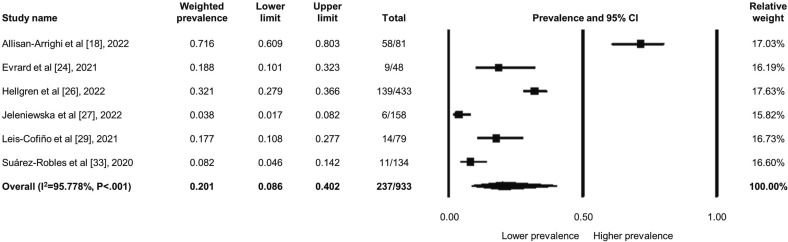

Among the 1716 patients, 367 patients kept suffering from persistent dysphonia owing to COVID-19 after recovery; the weighted prevalence was 17.1 % (95 % CI: 11.0 to 25.8 %) (Fig. 3 ). The heterogeneity was high across the studies (I2 = 92.918, P < .001). Besides, in the specific “long-COVID” subgroup with 933 patients, 237 of them still experienced persistent voice sequelae at least three months after recovery from COVID-19, accounting for 20.1 % (95 % CI: 8.6 to 40.2 %) of the weighted prevalence; the heterogeneity remained high in this subgroup (I2 = 95.778, P < .001) (Fig. 4 ). Nevertheless, the sensitivity analysis did not change the main findings as well regarding the dysphonia prevalence. The asymmetrical funnel plot indicated possible publication bias (Supplemental Fig. 2), but the insignificant results of the Egger's test did not show existing bias (P = .072).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot regarding the weighted prevalence of COVID-related dysphonia in patients after recovery from infection.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot regarding the weighted prevalence of long-COVID voice sequelae.

The further meta-regressions (Table 1) showed that unexpectedly, no statistically significant associations among mean age, gender, tracheostomy/intubation, and dysphonia assessment modalities and the prevalence of long-lasting dysphonia were identified. Despite this, all of the above parameters being pooled together could still account for 85.12 % of the heterogeneity analysis.

4. Discussion

Being one of the common COVID-related symptoms, voice disturbance has paramount influence on people's daily lives. Having been gradually understood for the potential mechanisms, in fact, it is often underestimated for the inconvenience and discomfort being left to the patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis specifically focusing on the prevalence and relative risk factors on COVID-related dysphonia. After the comprehensive analysis, we figured out that about a quarter of the patients infected with COVID-19 could experience new-onset dysphonia; furthermore, after recovery from the acute infection, approximately 70 % of these dysphonic patients could still suffer from long-lasting voice sequelae, which deserves the attention of global clinicians.

From the biomolecular perspective, it has been proved that COVID-19 could enter the human bodies with the aids of certain cellular surface proteins, mainly including angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) [38]; both of them are highly expressed in the aerodigestive tract [38,39]. Moreover, ACE2 appears even more frequently than TMPRSS2 in the head and neck region, especially the vocal tract [39,40]. After infected with COVID-19, subsequent series of inflammatory reactions driven by cytokines could generate corresponding symptoms especially in these upper airway locations. In COVID-19 patients, dysphonia is accompanied with various laryngeal manifestations, such as vocal cord immobility, and glottis/subglottic stenosis [41]. For those with persistent symptoms, adequate medication (e.g. corticosteroids, botulinum toxin), invasive treatment if indicated (e.g. surgery), and well-enacted rehabilitation programs (e.g. speech and language therapy) could provide certain benefits for symptoms relief [42]. The results of our study highlight the adverse impact of COVID-19 on voice, which is suggested to be aware of not only during active infection but also after recovery.

4.1. Dysphonia during COVID-19 infection

According to the results of the meta-analysis, 25.1 % of the COVID-19 patients experienced dysphonia during the acute infection, and female had a statistically higher prevalence rate. The gender differences in the presentation of COVID-19 patients have been studied previously by Haitao et al. [43], indicating that despite the inconsistencies of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expressions between genders, the general outcomes of male patients seemed to be more lethal. In addition, being a relatively less fatal symptom, dysphonia secondary to COVID-19 infection could result from the inherited immune response, which is more aggressive and significant in female adults [44]. The above evidence could serve as the probable explanations for the gender difference of this new-onset symptom during acute COVID-19 infection.

Based on the results of the meta-regression, it is also quite interesting that both tracheostomy/intubation and dysphonia assessment modalities are not the key factors associated with COVID-related dysphonia when analyzed together with gender and age. As for the procedure of intubation/tracheostomy, it is unsurprising that this potential confounding factor could inevitably cause injuries to the vocal cord and related tissues to some extent [45], which may in turn generate dysphonia. Nonetheless, as stated by Brodsky et al. [46], these short-term vocal symptoms are mostly self-limiting and may not always be severe enough to cause functional consequences. Therefore, though still important, the short-term iatrogenic effect could be less substantial compared to the inherited sex influence on COVID-related dysphonia since gender is a more crucial determinant related to cellular molecular pathways [43], and could be more important in general outcomes of COVID-19 patients. Moreover, due to safety reasons and less exposures, subjective means were more recommended to evaluate patients with suspected voice impairment during the pandemic [47]. The results of our study also indicated that adopting subjective measurements only could still provide results not inferior to using objective and/or subjective modalities in dysphonia assessments during acute COVID-19 infection.

4.2. Dysphonia post COVID-19 infection

The weighted prevalence of this study showed that 17.1 % of COVID-19 patients experienced dysphonia after recovery from COVID-19. Besides, in those specifically defined as long-COVID dysphonia, the weighted prevalence was 20.1 %. However, no significant correlations with post-COVID dysphonia were found in age, gender, tracheostomy/intubation, and dysphonia assessment modalities when all of the above covariates were analyzed together. Given that the presentation of COVID-related dysphonia could be a consecutive course extended from acute to post-acute stage, it might be reasonable that some of the findings in this group may be similar to those assessed during the acute infection period, while their effects could be lower after recovery. Furthermore, since inherited characteristics (age, gender) could be more related to viral activity itself and the disease severity during the acute phase [43,48], the influence on long-lasting dysphonia might be relatively lower after passing the acute episode.

As to the impact of tracheostomy/intubation, Neevel et al. [49] have studied the post-acute laryngeal impairments led by COVID-19 using laryngoscopy, concluding that dysphonia could occur in a proportion of patients regardless of receiving tracheostomy/intubation. A further study by Allisan-Arrighi et al. [18] directly comparing patients being intubated or not with a long-term follow-up also figured out that no significant difference of dysphonia was presented, which could together support the results in this study. The above condition could probably be explained by the fact that most of the symptoms following extubation regress within three days [50], which make this clinical factor less influential during a mid- to long-term follow-up. Methods for dysphonia evaluation for post-COVID dysphonia being less significant have also been directly investigated by Rouhani et al. [32], revealing significant positive association between endoscopic findings and self-reported dysphonia, which was in accordance with our pooled results.

There are two major strengths of this study. First, pre-existing dysphonia and laryngeal complications were excluded, which means that a majority of patients experiencing dysphonia due to comorbidities (e.g. LPR or GERD) or other personal reasons (e.g. frequent voice users) could not influence the exact dysphonia prevalence caused by COVID-19, making the results of this study more precise. Additionally, this study assessed the prevalence of COVID-related dysphonia mainly at two different timings: during infection and after recovery. This could provide more comprehensive epidemiological evidence that help tailor the clinical evaluation and probable treatment for these vulnerable patients with regard to symptom progression. On the other hand, some limitations should also be taken into considerations. First, since we majorly aimed to discover the prevalence of COVID-related dysphonia, the severity of voice impairment was not discussed in this study, which should be further investigated with more research. Second, factors such as smoking and certain minor comorbidities (despite pre-existing dysphonia has been excluded) that might affect the dysphonia prevalence were not analyzed due to lack of enough studies to provide enough power. Third, treatment for dysphonia were not analyzed as well; however, since most dysphonic patients discontinued treatment and lost follow-up after symptoms relief, the results could be greatly misleading when compliance was considered. Last but not least, the results of the present study were based on the literature having been published since the origin of the pandemic, which was more comprehensive but may not completely reflect the current predominant variant. With the evolvement of COVID-19, it could be expected that the real-world dysphonia prevalence might also be relatively lower in the near future under the omicron-predominant era, and should be further investigated with more research. Despite the general quality of the enrolled studies may not reach the highest level according to the assessment, the results could still provide certain insights into prevalence and risk factors for evaluating COVID-related dysphonia based on the present study nature, and more research is still warranted to elucidate this health issue in the future.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, 25.1 % of the COVID-19 patients, especially female, could experience dysphonia during acute infection. Moreover, 70 % of these dysphonic patients might keep suffering from persistent voice sequelae even after recovery, which should be cautiously evaluated and treated by the global clinicians. Future studies are still needed to better understand this important health issue in the post-pandemic era.

Financial support

This study received no financial support from any profit agency.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

C.W.L. conceptualized the idea, designed the study scheme, appraised the literature, curated the data, performed the analysis, and drafted the manuscript; Y.H.W. searched and appraised the literature, created and modified the tables and figures, and justified all the analyzed results; Y.E.L. searched and appraised the literature, and drafted the manuscript; T.Y.C. appraised the literature; L.W.C. drafted the manuscript; H.C.L conceptualized the idea, data interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript and final approval; C.T.C. data interpretation and justified all the analyzed results.

Declaration of competing interest

Dr. Hsin-Ching Lin received two research grants from Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA.

However, Intuitive Surgical Inc. had no role in the design or conduct of this study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Dr. Chung-Wei Lin, Dr. Yu-Han Wang, Dr. Yu-En Li, Dr. Ting-Yi Chiang, Dr. Li-Wen Chiu, and Professor Chun-Tuan Chang declare no potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the authors and the patients of the enrolled studies for sharing their experience and reports during the pandemic.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2023.103950.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Groff D., Sun A., Ssentongo A.E., et al. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williamson A.E., Tydeman F., Miners A., Pyper K., Martineau A.R. Short-term and long-term impacts of COVID-19 on economic vulnerability: a population-based longitudinal study (COVIDENCE UK) BMJ Open. 2022;12(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walczak P., Janowski M. The COVID-19 menace. Glob Chall. 2021;5(9):2100004. doi: 10.1002/gch2.202100004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elibol E. Otolaryngological symptoms in COVID-19. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(4):1233–1236. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song W.J., Hui C.K.M., Hull J.H., et al. Confronting COVID-19-associated cough and the post-COVID syndrome: role of viral neurotropism, neuroinflammation, and neuroimmune responses. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(5):533–544. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00125-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agyeman A.A., Chin K.L., Landersdorfer C.B., Liew D., Ofori-Asenso R. Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(8):1621–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saniasiaya J., Kulasegarah J., Narayanan P. New-onset dysphonia: a silent manifestation of COVID-19. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;145561321995008 doi: 10.1177/0145561321995008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miles A., McRae J., Clunie G., et al. An international commentary on dysphagia and dysphonia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dysphagia. 2022;37(6):1349–1374. doi: 10.1007/s00455-021-10396-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dassie-Leite A.P., Gueths T.P., Ribeiro V.V., Pereira E.C., Martins P.D.N., Daniel C.R. Vocal signs and symptoms related to COVID-19 and risk factors for their persistence. J Voice. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2021.07.013. S0892-1997(21)00253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson J.A., Deary I.J., Millar A., Mackenzie K. The quality of life impact of dysphonia. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2002;27(3):179–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2002.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soriano J.B., Murthy S., Marshall J.C., Relan P., Diaz J.V. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(4):e102–e107. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00703-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Borst B. Recovery after Covid-19. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2021;12:100208. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stemple J.C., Stanley J., Lee L. Objective measures of voice production in normal subjects following prolonged voice use. J Voice. 1995;9(2):127–133. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(05)80245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu P., Ouaknine M., Revis J., Giovanni A. Objective voice analysis for dysphonic patients: a multiparametric protocol including acoustic and aerodynamic measurements. J Voice. 2001;15(4):529–542. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(01)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Ani R.M., Rashid R.A. Prevalence of dysphonia due to COVID-19 at Salahaddin General Hospital, Tikrit City, Iraq. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42(5):103157. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2021.103157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allisan-Arrighi A.E., Rapoport S.K., Laitman B.M., et al. Long-term upper aerodigestive sequelae as a result of infection with COVID-19. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2022;7(2):476–485. doi: 10.1002/lio2.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alrusayyis D., Aljubran H., Alshaibani A., et al. Patterns of otorhinolaryngological manifestations of Covid-19: a longitudinal questionnaire-based prospective study in a tertiary hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13 doi: 10.1177/21501319221084158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azzam A.A.A., Samy A., Sefein I., ElRouby I. Vocal disorders in patients with COVID 19 in Egypt. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(Suppl. 2):3420–3426. doi: 10.1007/s12070-021-02663-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantarella G., Aldè M., Consonni D., et al. Prevalence of Dysphonia in Non hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 in Lombardy, the Italian Epicenter of the Pandemic. J Voice. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2021.03.009. S0892-1997(21)00108-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Çeçen A., Korunur Engiz B. Objective and subjective voice evaluation in Covid 19 patients and prognostic factors affecting the voice. J Exp Clin Med. 2022;39(3):664–669. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espiritu A.I., Sy M.C.C., Anlacan V.M.M., Jamora R.D.G. COVID-19 outcomes of 10,881 patients: retrospective study of neurological symptoms and associated manifestations (Philippine CORONA study) J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2021;128(11):1687–1703. doi: 10.1007/s00702-021-02400-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evrard D., Jurcisin I., Assadi M., et al. Tracheostomy in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome patients and follow-up: a parisian bicentric retrospective cohort. PloS One. 2021;16(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halpin S.J., McIvor C., Whyatt G., et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol. 2021;93(2):1013–1022. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hellgren L., Levi R., Divanoglou A., Birberg-Thornberg U., Samuelsson K. Seven domains of persisting problems after hospital-treated Covid-19 indicate a need for a multiprofessional rehabilitation approach. J Rehabil Med. 2022;54(jrm00301) doi: 10.2340/jrm.v54.2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeleniewska J., Niebudek-Bogusz E., Malinowski J., Morawska J., Miłkowska-Dymanowska J., Pietruszewska W. Isolated severe dysphonia as a presentation of post-COVID-19 syndrome. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022;12(8):1839. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12081839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lechien J.R., Chiesa-Estomba C.M., Cabaraux P., et al. Features of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 patients with dysphonia. J Voice. 2022;36(2):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leis-Cofiño C., Arriero-Sánchez P., González-Herranz R., Arenas-Brítez Ó., Hernández-García E., Plaza G. Persistent dysphonia in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. J Voice. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2021.07.001. S0892-1997(21)00234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller B, Tornari C, Miu K, et al. Airway, voice and swallow outcomes following endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation for COVID-19 pneumonitis: preliminary results of a prospective cohort study. 2020. Preprint. Posted online August 28, 2020. Research Square. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-65826/v1.

- 31.Özçelik Korkmaz M., Eğilmez O.K., Özçelik M.A., Güven M. Otolaryngological manifestations of hospitalised patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(5):1675–1685. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06396-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rouhani M.J., Clunie G., Thong G., et al. A prospective study of voice, swallow, and airway outcomes following tracheostomy for COVID-19. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(6):E1918–E1925. doi: 10.1002/lary.29346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suárez-Robles M., Iguaran-Bermúdez M.D.R., García-Klepizg J.L., Lorenzo-Villalba N., Méndez-Bailón M. Ninety days post-hospitalization evaluation of residual COVID-19 symptoms through a phone call check list. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:289. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.37.289.27110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suresh H., Nagaraja M.S. A study of clinical profile, sequelae of COVID, and satisfaction of inpatient care at a government COVID care hospital in Karnataka. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(6):2672–2677. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1754_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tornari C., Surda P., Takhar A., et al. Tracheostomy, ventilatory wean, and decannulation in COVID-19 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(5):1595–1604. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verma H., Shah J., Akhilesh K., Shukla B. Patients’ perspective about speech, swallowing and hearing status post-SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) recovery: E-survey. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279(5):2523–2532. doi: 10.1007/s00405-021-07217-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yasien D.G., Hassan E.S., Mohamed H.A. Phonatory function and characteristics of voice in recovering COVID-19 survivors. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279(9):4485–4490. doi: 10.1007/s00405-022-07419-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gkogkou E., Barnasas G., Vougas K., Trougakos I.P. Expression profiling meta-analysis of ACE2 and TMPRSS2, the putative anti-inflammatory receptor and priming protease of SARS-CoV-2 in human cells, and identification of putative modulators. Redox Biol. 2020;36:101615. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertram S., Heurich A., Lavender H., et al. Influenza and SARS-coronavirus activating proteases TMPRSS2 and HAT are expressed at multiple sites in human respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. PloS One. 2012;7(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Descamps G., Verset L., Trelcat A., et al. ACE2 protein landscape in the head and neck region: the conundrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Biology (Basel) 2020;9(8):235. doi: 10.3390/biology9080235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naunheim M.R., Zhou A.S., Puka E., et al. Laryngeal complications of COVID-19. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5(6):1117–1124. doi: 10.1002/lio2.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stachler R.J., Francis D.O., Schwartz S.R., et al. Clinical practice guideline: hoarseness (dysphonia) (update) Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158(1_suppl):S1–S42. doi: 10.1177/0194599817751030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haitao T., Vermunt J.V., Abeykoon J., et al. COVID-19 and sex differences: mechanisms and biomarkers. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2189–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Del Valle D.M., Kim-Schulze S., Huang H.H., et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1636–1643. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1051-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin C.W., Chiang T.Y., Chen W.C., et al. Is Postextubation Dysphagia Underestimated in the Era of COVID-19? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(5):935–943. doi: 10.1002/ohn.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brodsky M.B., Akst L.M., Jedlanek E., et al. Laryngeal injury and upper airway symptoms after endotracheal intubation during surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(4):1023–1032. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anagiotos A., Petrikkos G. Otolaryngology in the COVID-19 pandemic era: the impact on our clinical practice. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(3):629–636. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06161-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Attaway A.H., Scheraga R.G., Bhimraj A., Biehl M., Hatipoğlu U. Severe covid-19 pneumonia: pathogenesis and clinical management. BMJ. 2021;372:n436. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neevel A.J., Smith J.D., Morrison R.J., Hogikyan N.D., Kupfer R.A., Stein A.P. Postacute COVID-19 laryngeal injury and dysfunction. OTO Open. 2021;5(3) doi: 10.1177/2473974X211041040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brodsky M.B., Levy M.J., Jedlanek E., et al. Laryngeal injury and upper airway symptoms after oral endotracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation during critical care: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(12):2010–2017. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material