Abstract

Background

During the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, vaccination of healthcare workers (HCWs) has a critical role because of their high-risk exposure and being a role model. Therefore, we aimed to investigate vaccine hesitancy and the role of mandatory polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing and education for vaccine uptake.

Methods

We conducted an explanatory sequential designed observational mixed-methods study, including quantitative and qualitative sections consecutively in two different pandemic hospitals between 15 September 2021 and 1 April 2022. The characteristics of vaccinated and unvaccinated HCWs were compared. The vaccine hesitancy scales were applied, and the effect of nudging, such as mandatory PCR and education, were evaluated. In-depth interviews were performed to investigate the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among HCWs according to Health Belief Model.

Results

In total, 3940 HCWs were included. Vaccine hesitancy was more common among males than females, the ancillary workers than other health professions, and nonmedical departments than other departments. After the mandatory weekly PCR request nudge, 83.33 % (130/156) vaccine-hesitant HCWs were vaccinated, and 8.3 % (13/156) after the small group seminars and mandatory PCR every two days. The rate of COVID-19 vaccination was raised from 95.5 % to 99.67 % (3927/3940). At the end of in-depth interviews (n = 13), the vaccine hesitancy determinants were distrust, fear of uncertainty, immune confidence and spirituality, the media effect, social pressure, and obstinacy.

Conclusions

The nudging interventions such as mandatory PCR testing and small group seminars helped raise the rate of COVID-19 vaccination; the most effective one is mandatory PCR.

Keywords: Covid-19 pandemic, Healthcare worker, Vaccine hesitancy, Vaccine intake, Qualitative analysis, Mixed methods

1. Introduction

Healthcare workers (HCWs) have played a critical role in providing health services during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Many studies reported the rate of COVID-19 among HCWs, which appears to differ by region, term of the pandemic, and the positive case numbers of the population [1], [2], [3]. As of 16 May 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported more than 688 million cases and over 6.8 million deaths [4], creating significant challenges for healthcare services globally. Moreover, many HCWs got severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS CoV-2) infection through positive patients, co-workers, and extra-professional social contact [5].

The vaccination of the HCWs against COVID-19 has become the most effective preventive measure [6], [7], [8]. Unvaccinated HCWs were found to have a 12 times higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection [9]. Besides the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection, HCWs are accepted as a trusted source of information about the COVID-19 vaccines [10]; therefore, the rate of vaccination among HCWs can influence the population's vaccination rate [11].

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that as of 15 September 2021, 30 % of HCWs in more than 2000 US hospitals are COVID-19 vaccine-hesitant [12]. Moreover, the WHO announced this rate could be raised to 73 % among African HCWs on 25 November 2021 [13]. Vaccine hesitancy is defined by WHO as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite the availability of vaccination services” [14], and the most common causes of vaccine hesitancy among HCWs are vaccine safety, efficacy, and potential side effects [15], [16], [17], [18]. In addition, the reported predictors for vaccine hesitancy were age, gender, ethnicity, education, income, clinical position, vaccine technology, vaccine country of origin, lack of trust in the government/science/drug or vaccine companies, using social media, the strength of the social network, etc. [15], [17], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. Although, in order to overcome these barriers and raise the vaccination rate, some countries, including the United Kingdom, France, Greece, Italy, and Hungary, have mandated HCWs to be vaccinated [26]; some healthcare settings, where there was no mandate for COVID-19 vaccines, have used different strategies such as alert, reminder, to present an alternative, active choice or feedback [27].

These strategies can be considered nudging, which is defined as “any aspects of the choice architecture that predictably alters people's behaviour without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives” by Thaler and Sunstein, and these strategies can be used improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness [28]. According to a systematic review by Renosa et al., nudging interventions vary, including sending reminders, offering incentives, changing default participation mode from opt-in to opt-out, invoking social norms, and encouraging emotional response [29]. The objective of nudging strategies has varied from HCWs' compliance with hygiene standards, guidelines for the rational use of medicines, and evidence-based case management recommendations to improving communication with patients and vaccination rates [27]. The studies testing the nudging strategies used to increase vaccine uptake among patients, healthcare workers, and populations show that these interventions are effective, but further evidence is needed to develop concrete recommendations [29], [30], [31], [32].

COVID-19 vaccination started voluntarily on 13 January 2021 in Turkiye by giving priority to HCWs with the provision of CoronaVac (inactive SARS-CoV-2 vaccine) at the beginning and then BioNTech (mRNA vaccine) three months later [33]. As a result, the vaccination rate with at least two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine in Turkiye was 85.5 % by 19 July 2022; nevertheless, the rate of vaccination among HCWs has not been published by the Ministry of Health yet. Therefore, we had three main objectives for this study. First, we aimed to examine the rate of COVID-19 vaccination among HCWs; second, to observe the effectiveness of nudging interventions planned by the hospital administration, such as mandatory polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test submissions and group seminars for unvaccinated HCWs; and third, to explore the reasons of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and perceptions about interventions among HCWs in hospital settings.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

This is an explanatory sequential designed observational mixed-methods study, including quantitative and qualitative sections consecutively [34]. The study was conducted at two pandemic hospitals with 650 beds capacity (one tertiary university hospital and one private hospital under the same consortium) in Istanbul, Turkiye. Healthcare workers who were ≥ 18 years of age and did not get infected with SARS-CoV-2 within the last six months and did not get any COVID-19 vaccines yet were included in the study. In addition, the HCWs who took long-term leave (maternity leave, military duty) were excluded from the study. Written consent was obtained from the participants, and the Institutional Review Board of Koc University approved the study (No 2021.375.IRB1.108).

2.1.1. Institutional study timeline

After the publication of CDC and WHO reports on the concerns about COVID-19 vaccination rates among HCWs, our hospital administration department planned two types of interventions to raise the COVID-19 vaccination rate. As the study researchers, we observed the effects of these nudging interventions planned by hospital administration and evaluated the reasons for vaccine hesitancy of HCWs with the help of in-depth individual interviews.

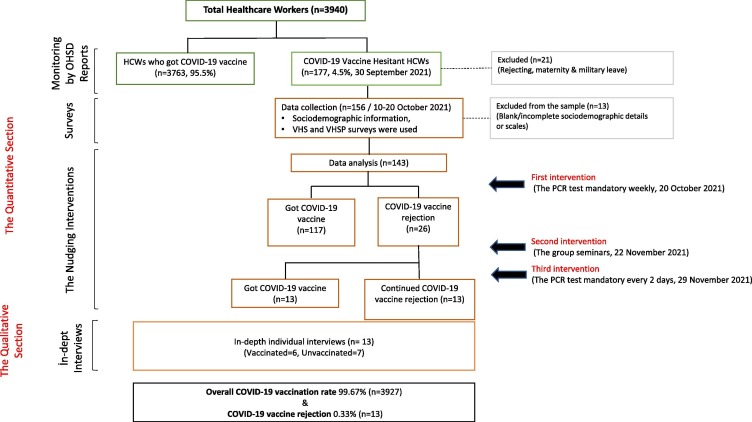

The first part of the study is based on monitoring the vaccination status of the HCWs through the health record data obtained from the Occupational Health and Safety Departments (OHSD). We have monitored the change in vaccination rates among HCWs weekly. The monitoring continued until the hospital administration cancelled the interventions upon the Ministry of Health's decision to abolish all the COVID-19 measures in the country on 19 January 2022. Therefore, we have defined the initial vaccination rate as voluntary and the latest vaccination rates as post-intervention. The second part of the study is comprised of a survey conducted between 10 October 2021 and 20 October 2021 before the interventions began. Data was collected via a self-reported survey from the HCWs, who had not yet been vaccinated at the time and had not been infected with SARS-CoV-2 within the last six months. When the data collection was completed on 20 October 2021, the hospital administration launched the intervention phase. Interventions included a weekly mandatory PCR test submission and mandatory group seminars regarding COVID-19 vaccines for unvaccinated HCWs. Vaccine-hesitant HCWs did not had to pay; they were led to the free PCR test centres near the study centre or their homes. On 29 November 2022, the hospital administration updated the mandatory PCR test submissions to be submitted every 48 h. We have monitored the COVID-19 vaccination status of the HCWs for six weeks by the researchers. The third part of the study was a qualitative inquiry based on in-depth interviews with the HCWs who still refused to get any of the COVID-19 vaccines after implementing the interventions for 12 weeks (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Study flow.

2.2. Data collection tools

The survey had 50 items in total, including socio-demographic information, “The Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS)” and “The Vaccine Hesitancy Scale in Pandemics (VHSP).“ VHS evaluated the individuals' attitudes on the general vaccination with 21 items (Cronbach alfa: 0.901) [26]. The VHS has four sub-factor, which are ”benefit and protective value of vaccine,“ ”vaccine repugnance,“ ”solutions for unvaccinated,“ and ”legitimization of vaccine hesitancy.“ VHSP assessed the vaccine hesitancy attitudes of people during pandemics with ten items (Cronbach alfa: 0.905) [27]. The VHSP also had two sub-scales: ”risk“ and ”lack of confidence.“For each survey, the participants were asked to rank their attitudes toward general and pandemic vaccines. The ranking was based on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The participants who responded incompletely to the research questions or surveys were excluded from the analysis.

We used a semi-structured interview form in the qualitative inquiry. The form was prepared based on the Health Belief Model (perceived severity, susceptibility, benefits, barriers, self-efficacy, cues to action), and in this study, we presented the results of perceived barriers for COVID-19 vaccination as it is relevant to the survey. This study's two authors (IK & BM) conducted in-depth interviews in the hospital setting. We used a purposeful sampling technique to invite the remaining 26 people who had not yet been vaccinated after 12 weeks of interventions.

2.3. Data analysis

In univariate analysis, for the continuous variables, t-test and ANOVA, and categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. The differences at the end of the ANOVA test Tukey, Hochberg's GT2, or Gabriel post-doc tests were used according to the sample number of groups. The score comparison of the VHS and VHSP before and after group education was made by the Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks test. The SPSS 28v (USA) was used in statistical analysis, and p < 0.05 was set as statistical significance. For the qualitative analysis, interviews were recorded upon the participant's consent, the recordings were transcribed verbatim, and the interview texts were analyzed in MAXQDA software. Two researchers (BM, IK) developed a codebook and coded the data. We used the content analysis technique to develop themes with the initial codes.

3. Results

Before the interventions, 3763 (95.5 %) HCWs out of 3940 got vaccinated with either BioNTech or CoronaVac, which the Ministry of Health provided between 11 February 2021 and 1 October 2021. The mean age of vaccinated and unvaccinated HCWs were 31.5 and 31.8, respectively (p = 0.355), and the mean years of working experience were 4.32 and 4.2, respectively (p = 0.605). Vaccine hesitancy was common among male HCWs, ancillary workers, and nonmedical departments (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of vaccinated and unvaccinated HCWs in study centers.

| Baseline Characteristic |

Unvaccinated HCWs (n = 177) n ( %) |

Vaccinated HCWs (n = 3763) n ( %) |

Total (n = 3940) n ( %) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Female Male |

91 (3.6) 86 (6) |

2399 (96.3) 1364 (94) |

2490 (100) 1450 (100) |

0.009 |

| Profession Physician Nurse Technician Administration Staff in ancillary † Other professionals‡ |

2 (1) 38 (3) 22 (4) 35 (4) 64 (10) 16 (5) |

405 (99) 1112 (97) 601 (96) 756 (96) 571 (90) 318 (95) |

407 (100) 1150 (100) 623 (100) 791 (100) 635 (100) 334 (100) |

P < 0.001 |

| Department Emergency Adult ICUs Operation Room Surgical Departments Internal Medicine Departments Pediatric Departments Other Medical Departments¥ Administration Nonmedical Departments≠ |

4(3) 8 (5) 9 (4) 11(2) 17 (3) 7 (5) 32 (5) 15 (6) 74 (8) |

122 (97) 168 (95) 231 (96) 699 (98) 632 (97) 136 (95) 681(95) 227 (94) 867 (92) |

126 (100) 176 (100) 240 (100) 710 (100) 649 (100) 143 (100) 713 (100) 242 (100) 941 (100) |

P < 0.001 |

Abbreviations.

Staff in ancillary †; Porter, cleaner, cafeteria employee, security, valet.

Other professionals‡; Pharmacists, physiotherapists, biologists, information technologies workers, translators, call center workers etc.

Other Medical Departments¥; Pharmacy, laboratory, pathology, radiology, checkup, home health, sterilization unit.

Nonmedical Departments≠; Housekeeping, refectory, maintenance, information technologies, security and parking, communications, accounting, logistic etc.

Before the first intervention, 177 HCWs were hesitant to or rejected the COVID-19 vaccine, and all were invited to the survey, for which we received 156 responses (88.13 %). The reasons for non-responding were unwillingness without reason (n = 12) and maternity leave or military leave (n = 9). In addition, incomplete surveys (n = 13) were excluded from the analysis. As a result, 143 (response rate of 80.79 %) participants were included in the quantitative data analysis (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

The baseline characteristics, COVID-19 history, and COVID-19 vaccination details of vaccine-hesitant HCWs (n = 143).

| Baseline Characteristics, COVID-19 History and Vaccination Attitudes | n ( %) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD, min–max) | 31.55 (6.92;18–55) | |

| Work Experience (SD, min–max) | 4.33 (5.16; 0–34) | |

| Gender | Female Male |

68 (48) 75 (52) |

| Marital Status | Married Single |

67 (47) 76 (53) |

| Comorbidities | Yes No |

26 (18) 116 (82) |

| Smoked cigarettes | Yes No |

56 (39) 86 (61) |

| Education | Primary or High School University or MSc or PhD |

37 (26) 106 (74) |

| COVID-19 History | ||

| Providing care COVID-19 patients | No Yes* Less than 8 h 8–12 h 13–24 h 24–48 h |

114 (80) 28 (20) 19 (68) 5 (18) 1 (4) 3 (11) |

| Have you ever been diagnosed with COVİD-19? | Yes No |

46 (32) 96 (67) |

| Has any family member of yours diagnosed with COVID-19? | Yes No |

63 (44) 79 (56) |

| Has someone among your family or friends died due to COVID-19? | Yes No |

10 (7) 132 (93) |

| Vaccination | ||

| Have you ever rejected any other vaccine? | Yes No |

38 (27) 105 (73) |

| Is there a vaccine that you think is unsafe? | Yes No |

73 (51) 70 (49) |

| Is there a vaccine that you do NOT recommend for children? | Yes No |

40 (28) 103 (72) |

| Have you ever had the flu shot? | Yes No |

30 (21) 112 (79) |

| Have you ever received any negative information about COVID-19 vaccines? | No Yes Social media Online news/magazine Family and friends TW Newspaper Other HCWs friend Other physicians Radio |

31 (22) 112 (78) 81 (72) 60 (54) 56 (50) 40 (36) 39 (35) 32 (29) 13 (12) 8 (7) |

| The current attitude to COVID-19 vaccines | Absolute refuse I am hesitant I will get vaccine at first opportunity |

31 (22) 74 (52) 38 (26) |

The average VHS score was significantly higher among non-smoker vaccine-hesitant HCWs (2.62 vs 2.38, p = 0.022). In advanced analysis, the mean scores of the “vaccine repugnance” (p = 0.020), “solutions for unvaccinated” (p = 0.004), and “risk” (p = 0.015) sub-scales were also significantly higher among non-smoker HCWs.

Following the first intervention, 26 HCWs were still COVID-19 vaccine-hesitant. They (n = 26) were included in the group seminars (second intervention), and after that, the duration of the PCR test was tightened to 48 h (third intervention) from weekly. At the end of three interventions, there were 13 COVID-19 vaccine-rejecting HCWs. In the qualitative section, we invited these 26 still vaccine-hesitant HCWs to participate in the face-to-face, in-depth interviews. Thirteen (6 vaccinated, 7 unvaccinated - 5 males, 8 females) out of 26 HCWs agreed to participate (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of interviewers.

| Interview | Gender | Age | Initial attitude to vaccination | Current Vaccination Status | COVID-19 History | Educational attainment | Smoking | Children if any |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | Female | 29 | Hesitant | Unvaccinated | Infected | University, MSc | No | No |

| I2 | Female | 40 | Refuse | Unvaccinated | Never | Up to high school | Yes | No |

| I3 | Female | 30 | Hesitant | Vaccinated | Never | University, MSc | Yes | No |

| I4 | Male | 38 | Refuse | Vaccinated | Infected | Up to high school | No | No |

| I5 | Female | 44 | Refuse | Unvaccinated | Infected | University, MSc | No | Yes |

| I6 | Male | 46 | Refuse | Unvaccinated | Never | University, MSc | No | No |

| I7 | Female | 48 | Hesitant | Unvaccinated | Infected | University, MSc | No | Yes |

| I8 | Male | 40 | Refuse | Unvaccinated | Never | Up to high school | Yes | Yes |

| I9 | Female | 31 | Hesitant | Vaccinated | Infected | University, MSc | No | Yes |

| I10 | Female | 30 | Refuse | Vaccinated | Infected | University, MSc | No | No |

| I11 | Female | 33 | Refuse | Vaccinated | Infected | University, MSc | No | No |

| I12 | Male | 26 | Hesitant | Unvaccinated | Infected | Up to high school | Yes | No |

| I13 | Male | 26 | Hesitant | Vaccinated | Infected | University, MSc | No | Yes |

The vaccine-hesitant HCWs' perceived barriers to accepting COVID-19 vaccines were categorized into six themes: distrust, fear of uncertainty, immune confidence & spirituality, media effect, social pressure, and obstinacy (Table 5). Distrust and fear of uncertainty were the most common themes among the HCWs. Under the theme of distrust, pharmaceutical companies producing the vaccines were the most prominent sub-theme as the source of this distrust (Table 5). Related to the distrust expressions, some HCWs pointed out that pharmaceutical companies caused the COVID-19 pandemic; some of them believed the pandemic never existed and that all the preventive measures were unnecessary. Some HCWs also expressed that there were some conspiracy theories about the pandemic (Some real expressions in Supplementary 1).

Table 5.

The themes and codes of the interviews that managed according to Health Belief Model.

| Themes | Sub-themes | Total number of codes |

|---|---|---|

| (Perceived Barriers) | What is the reason you refused to be vaccinated at first place? | |

| Distrust | The commercial intentions of pharmaceutical companies | 32 |

| The political preferences of the ministry of health | 27 | |

| Constantly updated and changing processes regarding preventive measures and treatment modalities | 23 | |

| Powerful institutions’ conflict of interests | 23 | |

| Tendency to believe in conspiracy theories | 22 | |

| Wait & see approach | 18 | |

| The discovery of COVID-19 vaccines in a short time | 11 | |

| Disbelief in COVID-19 or the pandemic | 11 | |

| Purposeful fear mongering | 11 | |

| Vaccination consent process | 9 | |

| Distrust towards health governing institutions | 6 | |

| Only emergency use approval of COVID-19 vaccines | 5 | |

| Distrust to the country that released the COVID-19 vaccine | 2 | |

| Fear of uncertainty | Conflicting news about effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines | 51 |

| Unforeseen side effects of COVID-19 vaccines | 48 | |

| Constantly updated and changing processes regarding preventive measures and treatment modalities | 28 | |

| Equal weight given to vaccinated and unvaccinated people when they get infected with COVID-19 | 16 | |

| The uncertainty regarding the number of booster doses | 10 | |

| Pregnancy-related reasonsf | 5 | |

| The concerns regarding their personal immunity | 3 | |

| Immune-confidence & Spirituality | Trust in their immune system to overcome the virus | 15 |

| Belief in the ability to heal after COVID-19 disease | 11 | |

| Use of immune-supportive medications | 5 | |

| Belief in spiritual powers that provides protection against diseases | 4 | |

| The media exposure | Confusion created by social media | 17 |

| Confusion created by the mainstream media | 7 | |

| Disturbing social pressure | By physicians or other co-workers | 10 |

| By members of their family | 8 | |

| By their close friends | 1 | |

| Obstinacy | Pure stubborn attitude towards the pressure to vaccinate | 4 |

Another theme was the fear of uncertainty that HCWs discussed. The most prominent sub-themes were conflicting news on social media and mainstream media outlets, side effects of COVID-19 vaccines, constantly updated information on the disease's microbiological, clinical, and public health aspects, and concerns regarding side effects (Some real expressions in Supplementary 1). Some other HCWs stressed their confidence in their immune system to overcome the disease, and these HCWs were mostly talking about “being present at the moment” as a way of life to prevent the severe consequences of COVID-19 disease.

The study participants complained about nudging interventions during in-depth interviews. The most challenging intervention was the mandatory PCR test submission. HCWs primarily complained about (1) not being able to follow their daily routine due to mandatory PCR testing; (2) having to wait in PCR test queues for hours; (3) discomfort of PCR testing, such as wounds in the nose; (4) shying away from being recognized in PCR test queues; (5) how these PCR tests were meaningless (Some real expressions in Supplementary 1).

3.1. The effect of nudging interventions to increase the rate of COVID-19 vaccination

After the implementation of free of charge mandatory PCR test (first intervention), 130 HCWs (46 % female) out of 156 (50 % female) were vaccinated. The vaccination rate among females was less than that of males (p = 0.032). All participants' vaccination status has been followed for six weeks. Still, vaccine-hesitant HCWs, despite the first intervention (n = 26, 69 % female), were involved in group seminars (second intervention) about the COVID-19 vaccines provided by the hospital infection control team. After the seminar, the frequency of PCR test submission was increased to every 48 h from once a week (third intervention) and sustained for more than six weeks. At the end of the third intervention, thirteen HCWs got COVID-19 vaccination (77 % females). Finally, 143 vaccine-hesitant HCWs out of 156 (91.6 %) got COVID-19 vaccines, and the vaccination rate was increased to %99.7 (3927/3940) in two hospitals.

4. Discussion

In this study, we defined the reasons for vaccine hesitancy and related factors, along with the effect of the nudging interventions implemented by the hospital administration among unvaccinated HCWs to further increase vaccination rates. The interventions, particularly mandatory PCR test submission, proved to be an effective method to increase the COVID-19 vaccine uptake among HCWs under the conditions that there is no legal enforcement for COVID-19 vaccination for HCWs in Turkiye. Numerous studies suggest that nudging interventions can be effective for this purpose [27], [29], [30], [31].

While some studies advocating such nudging interventions (showing negative PCR tests, vaccination, education, or some other restrictions) are usually provided “low-power” incentives to influence people's behaviour change [30], some other studies proved that these kinds of enforcement made notable changes in people's vaccine uptake behavior in the pandemics [35], [36]. The studies also assert that nudging interventions alone will not be practical to raise vaccine uptake. Researchers should also focus on other determinants such as communication strategy, the knowledge level about vaccines, the position or departments of HCWs [37], geographical [35], and generational differences [38] among HCWs. So, considering these suggestions, using the power of education, face-to-face interaction with vaccine-hesitant HCWs, and configuring original studies are crucial in increasing the vaccination rate. In this case, the hospital administration has mandated considerably strict measures for the HCWs who have not received any COVID-19 vaccines voluntarily. These nudging interventions were mandatory PCR test submission (initially once a week, later once every 48 h) and group seminars for unvaccinated HCWs on COVID-19 vaccines, which resulted in an increase in vaccination rate among HCWs from 95.5 % to %99.7 in two hospital settings.

We did not detect a significant difference in VHS and VHSP scores according to gender. While vaccine hesitancy has been reported to be more common among female HCWs in the literature [39], it is essential to note that our survey participants were selected from unvaccinated HCWs, who can be considered already hesitant. Our monitoring at baseline confirmed that unvaccinated HCWs were more common among males (6 % vs 3.6 %). However, previous studies have reported that uptake was more common among male HCWs [15], [20], [40], [41].

The reason that male healthcare workers in our study group were less likely to be vaccinated may be related to different perceptions of COVID-19 and the pandemic between the two genders. According to our qualitative analysis of the reasons for rejecting the COVID-19 vaccine, the first three reasons for male HCWs were distrust, fear of uncertainty, and media exposure, however it was fear of uncertainty, distrust, and immune confidence & spirituality for female HCWs. When we focused on the most common expressions among these reasons, male HCWs expressed “distrust for the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines”, “unforeseen side effects of COVID-19 vaccines”, and “distrust to frequently updated and changing processes,“ respectively. On the other hand, female HCWs expressed “unforeseen side effects of COVID-19 vaccines” first and then continued with “distrust for the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines” and “distrust to frequently updated and changing processes” as other reasons.

Before the interventions, unvaccinated HCWs were more common among ancillary workers (10 % vs. 1–5 %) and nonmedical departments (8 % vs 2–6 %). These differences could be explained by the predominantly male gender among ancillary workers (71 %) and nonmedical departments (65 %). In addition, the educational factor could explain another reason: the support and nonmedical personnel probably need to be more educated than other HCWs, such as physicians, nurses, and technicians. Some previous studies show that HCWs who are lower educated were less likely to get the COVID-19 vaccine [42], [43], [44]. Moreover, distrust of new vaccines can be another reason. In our qualitative data analysis, when we compare the rate of distrust expressions against the new COVID-19 vaccines, the rate of expressed distrust was higher among unvaccinated HCWs who were also less educated (17.5 vs. 13.2 expressions per person).

In the survey part of our study, many unvaccinated HCWs (n = 112, 78 %) indicated that they got negative information about COVID-19 vaccinations. According to some previous studies [18], [22], [23], the most common source of negative news was social media (72 %, Table 2). In previous studies, Reno et al. claimed that social media could increase vaccine hesitancy directly or indirectly [22]. Furthermore, Agha et al. underlined that social media could be a significant barrier to increasing the rate of COVID-19 vaccination [18]. Also, in our analysis, negative information from social media is statistically higher among vaccine-hesitant healthcare workers with higher levels of education (28 % vs 26 %, p = 0.021).

The average VHSP score was not different between smoker and non-smoker unvaccinated HCWs, whereas the average VHS score was higher among non-smoker HCWs than smokers (2.62 vs. 2.38, p = 0.022, Table 3 ). In addition, it was observed that non-smoker healthcare workers were more reluctant to receive the COVID-19 vaccine (p = 0.020), had a higher percentage of believing that vaccines were riskier (p = 0.015), and had more solutions to avoid getting vaccinated (p = 0.004) compared to smokers in our study group. Some current studies statistically indicated that smokers were more vaccine-hesitant than non-smokers (52.6 % vs. 30.9 %, p = 0.010)[45], however, in our study, non-smoker HCWs were more reluctant to the general vaccines. Analyzing unvaccinated HCWs' expressions in in-depth interviews can explain these differences. In our study group, the participants' expressions of “believing in conspiracy theories” were two times more common among non-smoker vaccine-hesitant HCWs than the smoker vaccine-hesitant HCWs.

Table 3.

The comparison of the VHS and VHSP scores according to characteristics of vaccine hesitant HCWs (n = 143).

| n | The Average Vaccine Hesitancy Scale Score | p | The Average Vaccine Hesitancy Scale in Pandemics Score | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 68 | 2.46 | 0.178 | 3.02 | 0.967 |

| Male | 75 | 2.60 | 3.02 | |||

| Marital Status | Married | 67 | 2.51 | 0.679 | 3.08 | 0.405 |

| Single | 76 | 2.55 | 2.97 | |||

| Chronic diseases | Yes | 26 | 2.45 | 0.758 | 3.06 | 0.803 |

| No | 117 | 2.54 | 3.01 | |||

| Education‡ | Primary and high school | 37 | 2.49 | 0.546 | 2.93 | 0.405 |

| University, MSc, PhD | 106 | 2.54 | 3.06 | |||

| Profession‡ | Nurse | 38 | 2.44 | 0.229 | 3.16 | 0.373 |

| Physician | 2 | 2.09 | 2.95 | |||

| Technician | 22 | 2.48 | 2.76 | |||

| Administration | 35 | 2.72 | 3.19 | |||

| Ancillary worker | 64 | 2.56 | 2.93 | |||

| Other HCWs | 16 | 2.33 | 2.92 | |||

| Smoking | Yes | 56 | 2.38 | 0.022* | 2.89 | 0.107 |

| No | 87 | 2.62 | 3.11 | |||

| COVID-19 History in past | Yes | 46 | 2.52 | 0.949 | 3.02 | 0.996 |

| No | 97 | 2.53 | 3.02 | |||

| Contact to COVID-19 patients | Yes | 28 | 2.51 | 0.708 | 3.02 | 0.991 |

| No | 115 | 2.52 | 3.02 | |||

| Lost someone due to COVID-19 | Yes | 10 | 2.68 | 0.435 | 3.28 | 0.291 |

| No | 133 | 2.52 | 3.00 | |||

| If there are other unsafe vaccines except COVID-19 vaccines | Yes | 73 | 2.70 | <0.001* | 3.39 | <0.001* |

| No | 70 | 2.35 | 2.64 | |||

| If there are any childhood vaccine you don’t suggest | Yes | 40 | 2.78 | 0.002* | 3.40 | <0.001* |

| No | 103 | 2.43 | 2.87 |

p < 0.005, t-test and ANOVA (‡) was use during analysis.

In-depth interviews based on the health belief model illustrated that the most common vaccine hesitancy reasons were distrust, fear of uncertainty, immune confidence and spirituality, the media effect, social pressure, and obstinacy, respectively (Table 5 ). In addition, “Conflicting news about the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines (51 expressions)”, “Unforeseen side effects of COVID-19 vaccines (48 expressions)”, and “The commercial intentions of pharmaceutical companies (32 expressions)” were the most common vaccine hesitancy codes (Table 5). The first three common causes of vaccine hesitancy, which we identified as themes, were the same according to gender. The fourth reason was “the effect of media” among males, ”the immune confidence and spirituality“ were among females.

This study is subject to some limitations. Due to the high uptake of vaccines among healthcare workers in our hospitals, our study cannot be generalized to other healthcare settings where vaccine intake is low. Health professionals' responses to such interventions may differ in different healthcare settings. However, the fact that there was a mixed-method study covering all health professionals in our two hospitals increased the inclusiveness and quality of the study.

5. Conclusion

Our results indicate that mandatory PCR testing for unvaccinated HCWs can further increase COVID-19 vaccination uptake. Combined efforts such as mandatory testing, group seminars, and dissemination of updated information helped raise the rate of COVID-19 vaccination to 99 %. Under such circumstances, remaining vaccine-hesitant HCWs can be considered as COVID-19 vaccine resistant, and there are various reasons, both external (the media effect, social pressure) and internal (distrust, fear of uncertainty, immune confidence, and obstinacy) to explain the vaccination rejection.

6. Funding source

This research received no specific grant from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to all participants for their willingness to participate in the study and their time to it. We are grateful to hospital management for their support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.06.022.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Kayi I., Madran B., Keske S., Karanfil O., Arribas J.R., Pshenismalles C.N., et al. The seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among health care workers before the era of vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:1242–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaselli N.M., Hungerford D., Shenton B., Khashkhusha A., Cunliffe N.A., French N. The seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 during the first wave in Europe 2020: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0250541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Huth S., Lillevang S.T., Roge B.T., Madsen J.S., Mogensen C.B., Coia J.E., et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among 7950 healthcare workers in the Region of Southern Denmark. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;112:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. WHO Coronavirus Dashboard; 2023.

- 5.Farah W., Breeher L., Shah V., Wang Z., Hainy C., Swift M. Coworkers are more likely than patients to transmit SARS-CoV-2 infection to healthcare personnel. Occup Environ Med. 2022 doi: 10.1136/oemed-2022-108276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maeda H., Saito N., Igarashi A., Ishida M., Suami K., Yagiuchi A., et al. Effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections during the Delta variant epidemic in Japan: Vaccine Effectiveness Real-time Surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 (VERSUS) Clin Infect Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tenforde M.W., Patel M.M., Ginde A.A., Douin D.J., Talbot H.K., Casey J.D., et al. Effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines for preventing Covid-19 hospitalizations in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muhsen K., Maimon N., Mizrahi A., Bodenneimer O., Cohen D., Maimon M., et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine against acquisitions of SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers in long-term care facilities: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ntziora F., Kostaki E.G., Grigoropoulos I., Karapanou A., Kliani I., Mylona M., et al. Vaccination hesitancy among health-care-workers in academic hospitals is associated with a 12-fold increase in the risk of COVID-19 infection: A nine-month Greek Cohort study. Viruses. 2021;14 doi: 10.3390/v14010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher K.A., Nguyen N., Crawford S., Fouayzi H., Singh S., Mazor K.M. Preferences for COVID-19 vaccination information and location: Associations with vaccine hesitancy, race and ethnicity. Vaccine. 2021;39:6591–6594. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dror A.A., Eisenbach N., Taiber S., Morozov N.G., Mizrachi M., Zigron A., et al. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35:775–779. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reses H.E., Jones E.S., Richardson D.B., Cate K.M., Walker D.W., Shapiro C.N. COVID-19 vaccination coverage among hospital-based healthcare personnel reported through the Department of Health and Human Services Unified Hospital Data Surveillance System, United States, January 20, 2021-September 15, 2021. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49:1554–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO . WHO; 2021. Only 1 in 4 African health workers fully vaccinated against COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacDonald N.E., Hesitancy S.W.G.O.V. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33:4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswas N., Mustapha T., Khubchandani J., Price J.H. The nature and extent of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in healthcare workers. J Community Health. 2021;46:1244–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-00984-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alle Y.F., Oumer K.E. Attitude and associated factors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health professionals in Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, North Central Ethiopia; 2021: cross-sectional study. Virusdisease. 2021;32:272–278. doi: 10.1007/s13337-021-00708-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mondal P., Sinharoy A., Su L. Sociodemographic predictors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: a nationwide US-based survey study. Public Health. 2021;198:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agha S., Chine A., Lalika M., Pandey S., Seth A., Wiyeh A., et al. Drivers of COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake amongst Healthcare Workers (HCWs) in Nigeria. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navin M.C., Oberleitner L.M., Lucia V.C., Ozdych M., Afonso N., Kennedy R.H., et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare personnel who generally accept vaccines. J Community Health. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10900-022-01080-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas C.M., Searle K., Galvan A., Liebman A.K., Mann E.M., Kirsch J.D., et al. Healthcare worker perspectives on COVID-19 vaccines: Implications for increasing vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers and patients. Vaccine. 2022;40:2612–2618. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu B., Zhang Y., Chen L., Yu L., Li L., Wang Q. The influence of social network on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional survey in Chongqing, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:5048–5062. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.2004837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reno C., Maietti E., Di Valerio Z., Montalti M., Fantini M.P., Gori D. Vaccine Hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccination: Investigating the role of information sources through a mediation analysis. Infect Dis Rep. 2021;13:712–723. doi: 10.3390/idr13030066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paris C., Benezit F., Geslin M., Polard E., Baldeyrou M., Turmel V., et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers. Infect Dis Now. 2021;51:484–487. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Sokkary R.H., El Seifi O.S., Hassan H.M., Mortada E.M., Hashem M.K., Gadelrab M., et al. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Egyptian healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:762. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06392-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tram K.H., Saeed S., Bradley C., Fox B., Eshun-Wilson I., Mody A., et al. Deliberation, dissent, and distrust: Understanding distinct drivers of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Europe M. Which countries in Europe will follow Austria and make COVID vaccines mandatory? 2022.

- 27.Sant'Anna A., Vilhelmsson A., Wolf A. Nudging healthcare professionals in clinical settings: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:543. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06496-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thaler R.H., Sunstein C.R. Yale University Press; London: 2008. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renosa M.D.C., Landicho J., Wachinger J., Dalglish S.L., Barnighausen K., Barnighausen T., et al. Nudging toward vaccination: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2021:6. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cantarelli P., Belle N., Quattrone F. Nudging influenza vaccination among health care workers. Vaccine. 2021;39:5732–5736. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dai H., Saccardo S., Han M.A., Roh L., Raja N., Vangala S., et al. Behavioural nudges increase COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature. 2021;597:404–409. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03843-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bianchi F.P., Stefanizzi P., Brescia N., Lattanzio S., Martinelli A., Tafuri S. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in Italian healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21:1289–1300. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2022.2093723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AA. The COVID-19 vaccination strategy; 2021.

- 34.Guetterman T.C., Fetters M.D., Creswell J.W. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:554–561. doi: 10.1370/afm.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mills M.C., Ruttenauer T. The effect of mandatory COVID-19 certificates on vaccine uptake: synthetic-control modelling of six countries. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e15–e22. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00273-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Lorenzo A., Tafuri S., Martinelli A., Diella G., Vimercati L., Stefanizzi P. Could mandatory vaccination increase coverage in health-care Workers? The experience of Bari Policlinico General Hospital. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:5388–5389. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1999712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toth-Manikowski S.M., Swirsky E.S., Gandhi R., Piscitello G. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among health care workers, communication, and policy-making. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomietto M., Simonetti V., Comparcini D., Stefanizzi P., Cicolini G. A large cross-sectional survey of COVID-19 vaccination willingness amongst healthcare students and professionals: Reveals generational patterns. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78:2894–2903. doi: 10.1111/jan.15222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lazarus J.V., Ratzan S.C., Palayew A., Gostin L.O., Larson H.J., Rabin K., et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27:225–228. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaw J., Hanley S., Stewart T., Salmon D.A., Ortiz C., Trief P.M., et al. Health Care Personnel (HCP) attitudes about COVID-19 vaccination after emergency use authorization. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chudasama R.V., Khunti K., Ekezie W.C., Pareek M., Zaccardi F., Gillies C.L., et al. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and hesitancy opinions from frontline health care and social care workers: Survey data from 37 countries. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2022;16 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.102361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adeniyi O.V., Stead D., Singata-Madliki M., Batting J., Wright M., Jelliman E., et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine among the Healthcare Workers in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: A Cross Sectional Study. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kara Esen B., Can G., Pirdal B.Z., Aydin S.N., Ozdil A., Balkan I.I., et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in healthcare personnel: A university hospital experience. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kandiah S., Iheaku O., Farrque M., Hanna J., Johnson K.B., Wiley Z., et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in four health care systems in Atlanta. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9:ofac224. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Derdemezis C., Markozannes G., Rontogianni M.O., Trigki M., Kanellopoulou A., Papamichail D., et al. Parental Hesitancy towards the established childhood vaccination programmes in the COVID-19 Era: Assessing the drivers of a challenging public health concern. Vaccines (Basel) 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.