Abstract

Long INterspersed Element 1 (LINE-1 or L1) acts as a major remodeling force in genome regulation and evolution. Accumulating evidence shows that virus infection impacts L1 expression, potentially impacting host antiviral response and diseases. The underlying regulation mechanism is unclear. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), a double-stranded DNA virus linked to B-cell and epithelial malignancies, is known to have viral–host genome interaction, resulting in transcriptional rewiring in EBV-associated gastric cancer (EBVaGC). By analyzing publicly available datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), we found that EBVaGC has L1 transcriptional repression compared with EBV-negative gastric cancer (EBVnGC). More specifically, retrotransposition-associated young and full-length L1s (FL-L1s) were among the most repressed L1s. Epigenetic alterations, especially increased H3K9me3, were observed on FL-L1s. H3K9me3 deposition was potentially attributed to increased TASOR expression, a key component of the human silencing hub (HUSH) complex for H3K9 trimethylation. The 4C- and HiC-seq data indicated that the viral DNA interacted in the proximity of the TASOR enhancer, strengthening the loop formation between the TASOR enhancer and its promoter. These results indicated that EBV infection is associated with increased H3K9me3 deposition, leading to L1 repression. This study uncovers a regulation mechanism of L1 expression by chromatin topology remodeling associated with viral–host genome interaction in EBVaGC.

INTRODUCTION

Long INterspersed Element 1 (LINE-1), also known as L1, is a group of non-long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons that are widespread in the genome of many eukaryotes (1–3). The human genome contains >500 000 L1s that occupy ∼17% of the genome (1–3), constituting the greatest remodeling force for shaping the genome structure and function (2–5). The retrotransposition-competent human L1 carries two open reading frames (ORFs), ORF1 and ORF2, coding for an RNA-binding protein and a reverse transcriptase-endonuclease, together with the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) and 3′-UTR necessary for transcription and transposition. As the only autonomous transposon in the human genome, transposition of L1s impacts the genome by generating genetic variations and mutations as well as regulating the expression of various genes (4,6–8). In addition, the L1-encoded proteins (ORF1p and ORF2p) can mobilize non-autonomous retrotransposons, other non-coding RNAs and mRNAs, leading to the generation of processed pseudogenes (2,3). Multiple mechanisms restrict the transcriptional activity of this potential mutagen to protect genome integrity (9). Specifically, epigenetic regulation, such as DNA methylation (10,11) and histone methylation (12–14), plays an important role in guarding against L1 activation. Alterations of epigenetic modification would lead to L1 dysregulation, causing genome instability (11) and in some cases diseases (9,15,16).

Accumulating evidence shows that virus infection impacts L1 expression and retrotransposition activity (7,17–21). Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), a member of the Herpesviridae, is among the most common human pathogens, with >90% of adults testing seropositive (22,23). EBV is an oncogenic virus that has been linked to Burkitt lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric cancer (22,24). EBV-associated gastric cancer (EBVaGC) is among the most common EBV-related tumors and is also a major type of gastric cancer (23,25,26). In EBV-infected cells, the viral DNA does not integrate into the host chromosomes. Instead, the EBV genome exists episomally (22,23,27). To ensure persistence of the infection, the viral episomal DNA tethers to host chromosomes to faithfully partition to the nuclei of daughter cells during mitosis (22,28). The tethering remodels chromatin topology, and hence alters the patterns of gene expression (27,29,30).

We set out to determine whether EBV infection impacts L1 expression in EBVaGC by integrating publicly available datasets. We found that the overall expression level of L1s was repressed in EBV-infected gastric cancer cells, with a subset of full-length L1s (FL-L1s) as the most impacted. The underlying mechanism by which viral–host genome interaction regulates L1 expression was explored.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Public data resource

Gene expression data of clinical samples and full clinical annotation empolyed in this study were retrieved from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database and the Asian Cancer Research Group (ACRG). Two previously deposited GC cohort data repositories, GSE62254/ACRG and TCGA-STAD (The Cancer Genome Atlas-Stomach Adenocarcinoma), were utilized. As previously described (31), EBV-negative gastric cancer (EBVnGC) samples that have the clinical variables most similar to the EBV-infected GC samples were selected to correct confounding effects (Supplementary Table S1).

Raw FASTQ files of four types of datasets, i.e. RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, 4C-seq and HiC-seq, from all cell lines utilized in this study were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (Supplementary Table S1). RNA-seq datasets of MKN7, MKN7_EBVi, SNU-719, NCC24 and YCC10 were from GSE84897, GSE85465, GSE141352, GSE141385 and GSE147152, respectively. ChIP-seq datasets of MKN7, MKN7_EBVi, SNU-719, NCC24, YCC10, MKN7_vector, MKN7_EBNA1, MKN7_EBVi_vector and MKN7_EBVi_dnEBNA1 cell lines were from GSE97837, GSE97838 and GSE135175, respectively. 4C-seq data of MKN7_EBVi and HiC-seq data of both MKN7 and MKN7_EBVi were from GSE135174 and GSE135941.

Ethical review, experimental and methodological details relating to study design and data acquisition can be found in the original reports.

RNA-seq data analysis

Raw Sequence Read Archive (SRA) files were downloaded from the GEO and transferred to FASTQ file by the SRA Toolkit (version 2.11.1). Read trimming procedures with additional quality trimming (≥20) and sequence length filtering (≥20 nt) were applied to remove adapter sequences and low sequencing quality bases using Trim Galore (version 0.6.6). FastQC (version 0.11.9) was used to assess read quality and adapter contamination. Trimmed RNA-seq reads were aligned to the human genome (GRCh37/hg19) using STAR (version 2.7.9a) (32) with parameters of –outFilterMultimapNmax 100 and –winAnchorMultimapNmax 100 to obtain multi-mapped reads. STAR with –outFilterMultimapNmax 1 option was utilized to quantify uniquely aligned reads on L1 annotation and coding gene annotation.

TEtranscripts from the TEToolkit (version 4.11) (33) with multi-mode option was applied to analyze the transcription level of L1 subfamilies and coding genes based on multi-mapped reads. FeatureCounts from the Subread package was used to quantify the expression level of L1 copies with unique alignments to annotated L1s in the human genome assembly (hg19) downloaded from the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) table browser. After quantification, we used R sva (version 3.40.0) (34) to search for and to correct hidden batch effects. After the removal of unexpressed transposable element (TE) copies (<1 reads in total across all samples), differential expression of L1 subfamilies, individual L1 copies and protein-coding genes were identified using R DESeq2 (version 1.32.0) (35) with the significance criteria of |log2FC| >1 and P <0.05. The R ggplot2 (version 3.3.5) package was used for data visualizing.

Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using GSEA (version 4.1.0) with default parameters. The gene set of HUSH-bound L1s was retrieved from published data (6).

ChIP-seq data analysis

Sequencing reads were trimmed using Trim Galore (–q 20 –3 10) and read quality was assessed by FastQC. Trimmed reads were then mapped to the UCSC human genome assembly (hg19) using Bowtie2 (version 2.2.5) (36) with default parameter settings. MarkDuplicates function from Picard tools (version 2.25.6) was used to remove duplicated reads. Peak calling and peak annotations were determined using HOMER with default settings. bedtools (version 2.30.0) (37) was applied to quantitatively analyze the L1 histone modifications. LINE-1_annotation.bed was converted from the LINE-1 annotation file imported from HOMER using a custom R script. H3K9me3- and H3K27me3-modified L1 elements were identified by performing bedtools by intersecting bed files of these two modification signals with LINE-1_annotation.bed.

For visualization, bigWig coverage files normalized to FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments) were generated with deepTools (version 3.5.1) (38) with the default configurations. Heatmap and plots map were made by using the plotHeatmap function of deepTools. The .bigWig files were subsequently loaded into IGV (version 2.8.069) (39) for peak visualization.

HiC-seq data analysis

The HiC-Pro (40) pipeline was used to align sequence reads to the UCSC hg19. Juicer (version 1.22.01) (41) was utilized to convert allvalidpairs files to .hic files. Chromatin loops were called using the CPU version of HICCUPS with Juicer Tools and visualized by IGV software.

4C-seq data analysis

The w4Cseq (42) pipeline was used to map reads to UCSC hg19 for detecting statistically significant interacting regions. We used IGV software to visualize significant interactions and identified genes associated with captured fragments.

siRNA-mediated knockdown in SNU-719 cells

SNU-719 cells were from the Korean Cell Line Bank. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin within a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. The oligos of small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting human TASOR, PPHLN1 and MPP8 (Supplementary Table S2) were synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). Transfections of siRNAs were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 following the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, cells were plated in 6- or 24-well plates (Corning) 24 h before transfection. Non-targeting control siRNA was used as negative control. Cells were harvested 72 h after transfection and subjected to RNA extraction or western blots.

RNA extraction and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay

Total RNA was extracted from transfected cells using TRIzol reagent (15596026, Life Technologies) following the manufacturer's instructions. A 1 μg aliquot of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using HiScript III RT SuperMix (R323-01, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Q711-02-AA, Vazyme, Nanjing, China) on an Applied Biosystems 7300 real-time PCR system. Data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method to obtain relative abundance. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used for normalization. Primers used in the detection are listed in Supplementary Table S3.

Western blot

Live cells were lysed in protein extraction buffer [50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS), 10 μM EDTA] with protease inhibitors for 30 min at 4°C. After a brief centrifugation, the supernatant of the cell lysate was collected and separated by 8% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were blocked with 2% non-fat milk in TBST (Tris-buffered saline; 100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) followed by incubation with rabbit anti-LINE-1 ORF1p antibody (ab230966, Abcam) or rabbit anti-FAM208 (TASOR) antibody (ab224393, Abcam) at 4°C overnight. Membranes were washed three times with TBST and then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated mouse anti-rabbit secondary antibody (31464, Thermofisher Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature. After washing three times with TBST, proteins on the PVDF membrane were detected using an ECL reagent kit (P0018FS, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and the ChemiScope 6000 Touch imaging system (Clinx, China). GAPDH was used as a loading control which was detected with mouse anti-GAPDH antibody (AF2819, Beyotime) followed by an HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse secondary antibody (61–6520, Thermofisher Scientific).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Sample sizes were determined by the available dataset numbers deposited in the GEO. Assessment of differences between groups was performed using Welch's t-tests for comparing two unpaired datasets. Pearson correlation analysis were performed by the R ggpmisc (version 0.4.0) package. Continuous variables were analyzed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test using the R stats package. We describe statistically significant differences as *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001 or ****P <0.0001.

RESULTS

Identification of differentially expressed L1s in EBV-infected GC cells

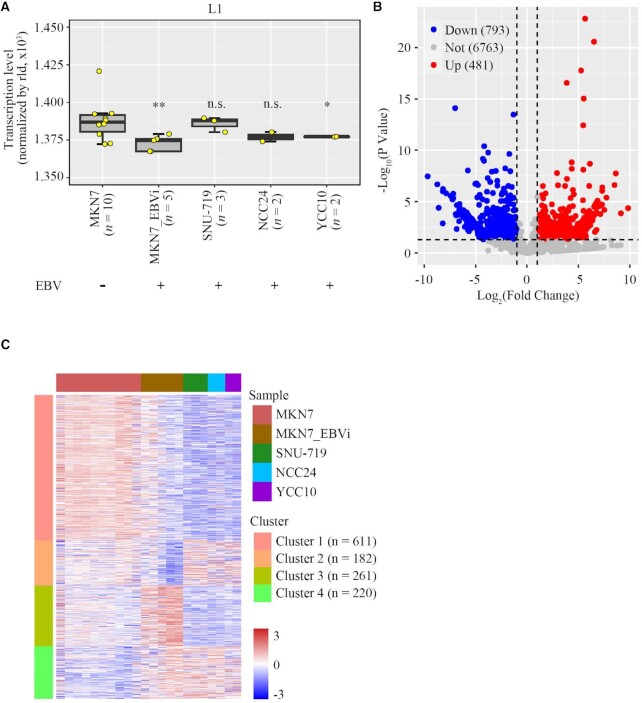

To explore the impact of EBV on L1 expression in EBVaGC, genome-wide L1 transcription was analyzed in GC cell lines with or without the presence of the EBV genome. We retrieved all currently available RNA-seq datasets of the GC cell MKN7 and EBV-infected MKN7 cell line (MKN7_EBVi) from the GEO database to perform a comprehensive analysis of genome-wide L1 transcription (27,43–46). After using the sva package to correct the batch effect and trimming L1 copies counted 0 in all samples, cell types were found to be well clustered (Supplementary Figure S1A). We noticed that the overall expression levels of L1s were significantly decreased in MKN7_EBVi compared with those in MKN7 (Figure 1A). Using the same approach, we also analyzed L1 expression in three naturally EBV-infected GC cells (SNU-719, NCC24 and YCC10), all of which are known to carry latent EBV in the cell. In the absence of representative EBV-negative controls for these cell types, we used MKN7 for comparison. We found that L1 expression in YCC10 was also down-regulated (P <0.05), similar to that observed in MKN7_EBVi (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

L1 expression was repressed in EBV-infected gastric cancer cells. (A) Overall L1 expression level in MKN7, MKN7_EBVi, SNU-719, NCC24 and YCC10 cells shown in a box plot. Boxes represent: central lines, median; limits of the boxes, interquartile range of values; yellow dots, mean value of L1 expression level for individual samples. The asterisks represent the statistical P-value (*P<0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001, Mann–Whitney U-tests). (B) Scatter plots showing significantly repressed L1s (blue dots), significantly up-regulated L1s (red dots) and all other L1s (gray dots) in MKN7_EBVi cells compared with MKN7 cells. Average expression for each L1 locus across all samples of the same cell type was used for calculation for the fold change in MKN7_EBVi cells compared with MKN7 cells. Differentially expressed copies of L1 were defined as those with ≥2-fold change and P-value ≤0.05 using DESeq2. (C) Cluster heatmap showing the expression level of differentially expressed L1s identified in MKN7_EBVi, SNU-719, NCC24 and YCC10 compared with MKN7. Red represents high expression of L1s and blue represents low expression.

We then compared the expression of each individual L1 locus in MKN7 and in EBV-infected GC cell lines. After having excluded L1 copies counted 0 in both samples, a total number of 8037 L1s were retained for the analysis. Among them, 1274 L1s were found to be differentially expressed (DE-L1s; |log2FC| >1 and P <0.05) which included 793 down-regulated L1s and 481 up-regulated L1s in MKN7_EBVi compared with those in MKN7 (Figure 1B).

We then investigated whether the alteration pattern in L1 expression was shared among EBV-infected cells. We found that 611 out of the 793 (77.0%) down-regulated L1s identified in MKN7_EBVi cells are also down-regulated in three naturally EBV-infected GC cells, whereas only 220 out of 481 (45.7%) up-regulated L1s identified in MKN7_EBVi cells remain up-regulated in those three cell lines (Figure 1C). These results indicated that repressed L1s were more likely to be shared in EBV-infected GC cells.

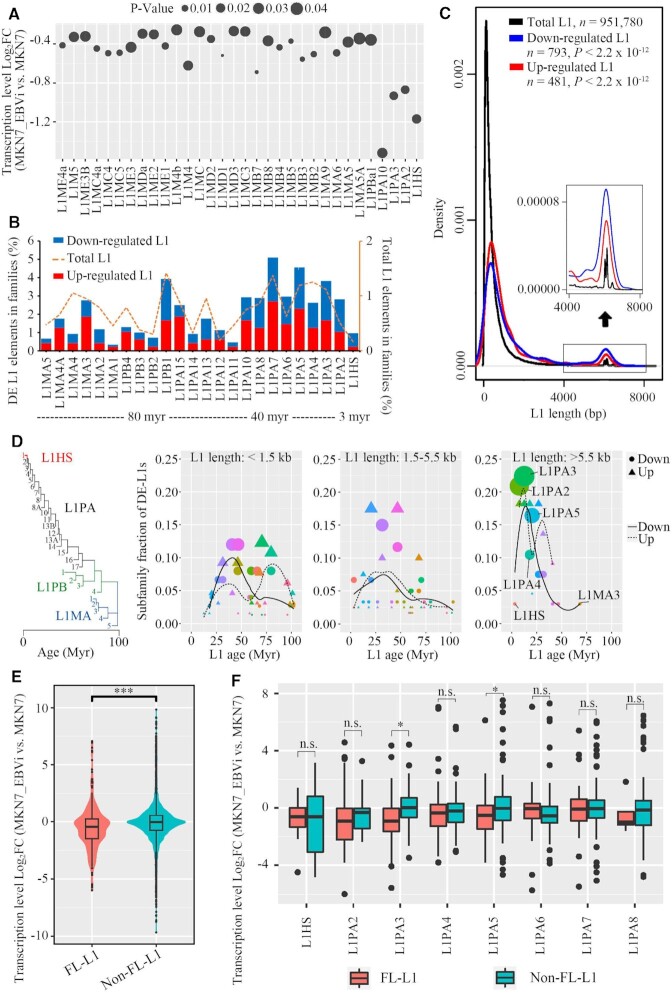

Young and full-length L1s are repressed in EBVaGC

L1 has integrant evolutionary age which represents active dominant L1 subpopulations in different waves during evolution (47,48). We found that L1 subfamilies in general were significantly repressed in MKN7_EBVi compared with MKN7, while young L1 subfamilies, such as L1HS (L1PA1), L1PA2 and other primary L1 subfamilies such as L1PA3 and L1PA10 had a markedly higher degree of decrease in expression (Figure 2A). We further examined the evolutionary track of the up-regulated and down-regulated L1s and found that suppressed L1 copies primarily belonged to lineages younger than 40 million years, in particular L1HS, L1PA2 and L1PA3 (Figure 2B). Notably, up-regulated L1s were largely attributed to older L1M subfamilies (Figure 2B). We then analyzed L1 length distribution. In the human genome, the majority of L1s are of <1 kbp in length due to truncations (6). Likewise, we found that most of the L1s fell into this category (Figure 2C). The median length of repressed L1s is 654 bp which is slightly longer than that of up-regulated L1s (640 bp). Nevertheless, we found that both the repressed and up-regulated L1s were enriched in FL-L1 populations, indicating that the expression of FL-L1s is prone to be affected (Figure 2C). In particular, the repressed L1s had a higher level of enrichment for FL-L1s compared with the up-regulated L1s (Figure 2C), suggesting the specific enrichment of repressed L1s on FL-L1s.

Figure 2.

Young and full-length L1s were the most repressed L1s in EBV-infected gastric cancer cells. (A) Dot plot showing log2FC and P-value of L1 expression for subfamilies with significant expression change (MKN7_EBVi versus MKN7). (B) Subfamily analysis of DE-L1s: subfamily distribution of DE-L1s (down-regulated L1, blue; up-regulated L1, red) and subfamily distribution of human genome-wide L1s (dotted lines). Myr, million years. (C) Size distribution of the DE-L1s (down-regulated L1, blue; up-regulated L1, red; total L1s, black). The y-axis is the fraction of L1s ranked by length. A zoom-in view of the size distribution (length >4 kbp) is shown as an inset. P-value, two-tailed Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. (D) Dot plot showing the fraction of DE-L1 subfamilies (center values) as a function of L1 length (three size groups are presented) and age [phylogenetic analysis was performed to predict the age of L1 subfamilies (47)]. Colored dots represent different L1 families, with areas proportional to the number of DE-L1s. Circle, down-regulated L1s. n = 202. Triangle, up-regulated L1s. n = 127. The logistic regression lines for down- (continuous line) and up-regulated (dotted line) L1s are plotted. (E) Violin plot showing the log2FC of FL-L1s and non-FL-L1s (MKN7_EBVi versus MKN7). A total number of 8037 L1 loci were included in the analysis. (F) Box plot showing the log2FC of FL-L1s and non-FL-L1s for each subfamily (MKN7_EBVi versus MKN7; FL-L1s, red; non-FL-L1s, blue). Boxes represent: central lines, median; limits of the boxes, interquartile range of values; black dots, outliers. The asterisks represent the statistical P-value (*P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001, Mann–Whitney U-tests).

An additional analysis was performed by combining the age and length of DE-L1s. We found that the <1.5 kb group was enriched with L1 subfamilies of 40 million years old for down-regulated L1s and 80 million years old for up-regulated L1s. The enrichment of DE-L1s belonging to the 1.5–5.5 kb group was slightly shifted to subfamilies of younger ages. Interestingly, the >5.5 kb group of DE-L1s was enriched with young L1 subfamlies, such as L1PA2 and L1PA3. Within this group, down-regulated L1s distinctly outcompeted the up-regulated L1s from the aspect of both fraction and number (Figure 2D). We further compared the expression of FL-L1s and non-FL-L1s, and found that FL-L1s were significantly repressed in MKN7_EBVi (Figure 2E). We looked specifically into the evolutionarily young L1 subfamilies and observed a universally down-regulated pattern for both FL-L1s and non-FL-L1s, whereas FL-L1s in general exhibited a larger degree of decline compared with non-FL-L1s for most L1 subfamilies (Figure 2F). We finally looked at the age distribution of the FL-L1s and unsurprisingly found that 7038 out of 7321 FL-L1s (96.1%) belong to the L1P family. This is consistent with the notion that older subfamilies typically have fewer full-length loci (49). These results together revealed that young and FL-L1s with autonomous transposition potential were selectively repressed in EBVaGC.

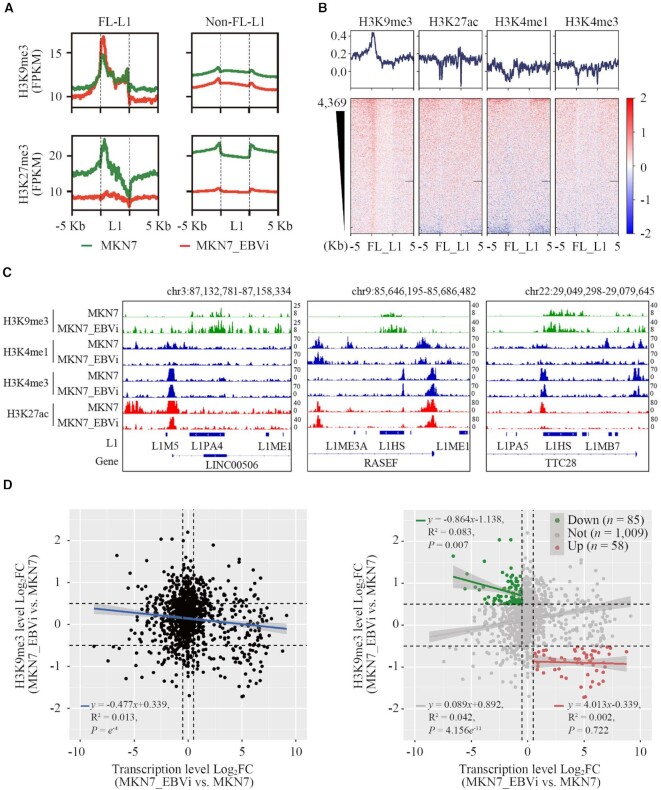

FL-L1s have aberrant histone modifications in EBVaGC

To explore the underlying mechanism for the repression of FL-L1s in EBVaGC cell lines, we asked whether EBV infection would alter the histone modification of L1s since histone modification is important for regulation of L1s (2,3,6). For this, we analyzed ChIP-seq datasets of MKN7 and MKN7_EBVi retrieved from the GEO (50). We compared the signals of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3, two suppressive histone modification markers, on FL-L1s, the subset which exhibited the most impacted expression alteration upon EBV infection. A noticeably increased H3K9me3 signal was detected at the 5′ end of FL-L1s but not of the non-FL-L1s in MNK7_EBVi compared with those in MKN7 (Figure 3A). H3K27me3 signal was significantly decreased for both FL-L1s and non-FL-L1s in MNK7_EBVi compared with those in MKN7, which indicated that H3K27me3 is unlikely to be the contributor (Figure 3A). Interestingly, FL-L1s are highly enriched with H3K4me3 and H3K27Ac in MKN7 cells (Supplementary Figure S2A), implying that these repressed L1s probably have transcriptional potential in the original MKN7 cells without EBV infection (51). Nevertheless, H3K27ac, H3K4me1 and H3K4me3 signals were distinctly decreased in the FL-L1 population in MNK7_EBVi (Figure 3B). This is consistent with the notion that suppressive and active histone marks antagonize each other. The observation was confirmed by analyzing H3K9me3 modification using three representative L1s displayed in Figure 3C. The MKN7_EBVi cell line had a significant accumulation of H3K9me3 modification on two L1HS copies and one L1PA4 copy which are located on chromosomes 22, 9 and 3, respectively. The 5′ end of these L1s exhibit the most alteration. These results indicated that repressed FL-L1 expression was likely to be attributed to the elevated H3K9me3 modification level which occurred at the promoter region of FL-L1s.

Figure 3.

L1s had aberrant histone modifications in EBVaGC. (A) Average tag density plots showing H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 log2FC enrichment at L1 regions in MKN7_EBVi cells compared with MKN7 cells (MKN7, green; MKN7_EBVi, red; H3K9me3, up; H3K27me3, down; FL-L1, left; non-FL-L1, right). (B) Heatmaps (down) and average tag density plots (up) showing H3K9me3, H3K27ac, H3K4me1 and H3K4me3 log2FC enrichment at FL-L1 (MKN7_EBVi versus MKN7). Black horizon represents the missing signal in the sequencing data. (C) IGV tracks: H3K9me3, H3K4me1, H3K4me3 and H3K27ac signals of three FL-L1P members in MKN7 and MKN7_EBVi cells are shown. The represented signals were normalized by FPKM. Chr, chromosome. (D) The dot plot showing the relationship between log2FC of the FL-L1 transcription level and the FL-L1 H3K9me3 modification level (MKN7_EBVi versus MKN7). Left panel, entire population of FL-L1; right panel, subpopulation analysis.

To further address the impact of EBV on FL-L1 H3K9me3 modification, we analyzed a H3K9me3 ChIP-seq dataset from MKN7_EBVi cells but with the EBV genome removed by the dominant negative EBNA1 (dnEBNA1) inhibitor (27). The H3K9me3 modification levels at L1 regions noticeably decreased after elimination of the EBV genome (Supplementary Figure S2B). For comparison, MKN7 cells or MKN7_EBVi cells that had the EBV genome removed had significantly fewer H3K9me3 marks. This result implicated EBV in the aberrant H3K9me3 modification at FL-L1s.

In addition, we examined the correlation between H3K9me3 modification and expression on these FL-L1s, and found higher levels of H3K9me3 signal correlated to a lower expression of FL-L1s in MKN7_EBVi (Figure 3D, left panel). Specifically, expression of down-regulated L1 subgroups significantly negatively correlated to H3K9me3 modification (P = 0.007) (Figure 3D, right panel). These results suggested that increased H3K9me3 levels on FL-L1s probably contributes to suppression of FL-L1s in EBV-infected cells.

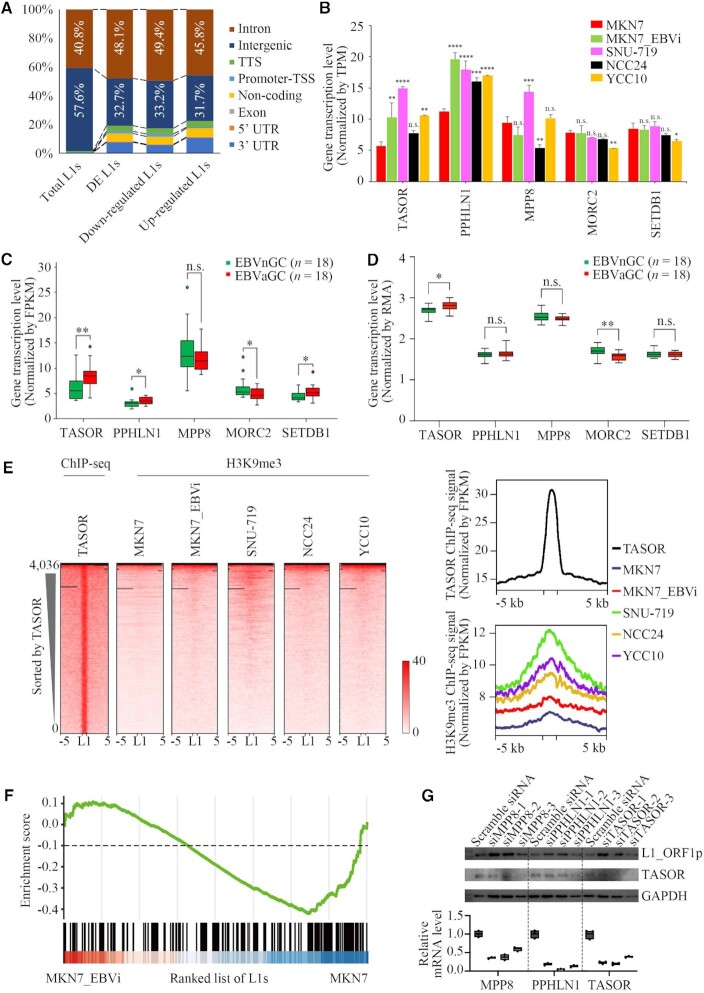

H3K9me3 enrichment in TASOR-bound L1s in EBVaGC

The majority of human L1s are located in non-coding regions, including intergenic regions and introns (6,7). We annotated the DE-L1s in EBV-infected cells and observed that these L1s were enriched within the introns, especially the repressed L1s (Figure 4A). The human silencing hub (HUSH) is responsible for H3K9me3 deposition on intronic L1s (6). We thus addressed whether the HUSH complex had a role in L1 repression in EBV-infected cells. The HUSH complex is composed of the scaffold protein TASOR, MPP8 and PPHLN1, and recruits MORC2 and SETDB1 for its function (6,52). We observed that both TASOR and PPHLN1 are transcriptionally up-regulated in most EBV-infected cell lines (P <0.01) (Figure 4B). This observation was further investigated using expression datasets retrieved from the TCGA and the ACRG database. Consistent with the results from EBV-infected cells, higher expression levels of both TASOR and PPHLN1 were correlated to EBVaGC compared with that from EBVnGC in TCGA datasets (Figure 4C). In addition, we also observed a correlation of slight SETDB1 up-regulation to EBVaGC (Figure 4C). Moreover, a similar pattern was observed in the ACRG dataset with a correlation of an increase of TASOR expression to EBVaGC (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

TASOR up-regulation and H3K9me3 enrichment in TASOR-bound L1s in EBVaGC. (A) Bar charts showing the region of distribution for the DE-L1s in MKN7, MKN7_EBVi, SNU-719, NCC24 and YCC10 cells. (B) The expression of TASOR, PPHLN1, MPP8, MORC2, SETDB1 in MKN7 (red), MKN7_EBVi (green), SNU-719 (purple), NCC24 (black) and YCC10 (yellow) cells. The asterisks represent the statistical P-value (*P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001, Welch's t-test). (C, D) Box plots showing the mRNA level between EBVnGC samples (green) and EBVaGC samples (red) from TCGA (C) and ACRG (D). Boxes represent: central lines, median; limits of the boxes, interquartile range of values; dots, outliers. The asterisks represent the statistical P-value (*P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001, Welch's t-test). (E) Heatmaps (left) and average tag density plots (right) showing TASOR signal enrichment (normalized by FPKM) at L1s in K562 cells, and H3K9me3 signal enrichment at L1s in MKN7 (navy), MKN7_EBVi (red), SNU-719 (green), NCC24 (orange) and YCC10 (purple) cells. Black horizon represents the missing signal in the sequencing data. (F) GSEA of L1 RNA-seq data of MKN7_EBVi compared with MKN7 by the HUSH-bound L1 set. (G) Upper panel, L1_ORF1p and TASOR protein levels in SNU-719 treated with siRNA targeting MPP8, PPHLN1, TASOR or scramble siRNA shown by western blotting with GAPDH as a loading control. Lower panel, box plot showing mRNA level for TASOR, PPHLN1 and MPP8 between SNU-719 treated with siRNA targeting MPP8, PPHLN1, TASOR or scramble siRNA.

To address the role of the HUSH complex in L1 regulation in EBVaGC cells, we examined H3K9me3 modification for the L1s captured by TASOR ChIP-seq (6) in EBV-infected GC cell lines. We observed an increased H3K9me3 signal at TASOR-bound L1s (Figure 4E). We further performed GSEA and found a significant enrichment of down-regulated L1s in HUSH-bound L1s. This implies a correlation between HUSH binding and L1 down-regulation in EBV-infected cells (Figure 4F).

To confirm that the HUSH complex may play a role in the down-regulation of FL-L1s in EBVaGC, we performed HUSH complex knockdown in SNU-719 cells, a naturally EBV-infected GC cell line, using RNA interference. siTASOR, siMPP8 or siPPHLN1 resulted in a decreased expression of target genes, which was accompanied by a significantly increased expression of L1-orf1p (Figure 4G).

Altogether, these data suggested that the increased H3K9me3 level on L1s was probably related to TASOR up-regulation in EBVaGC.

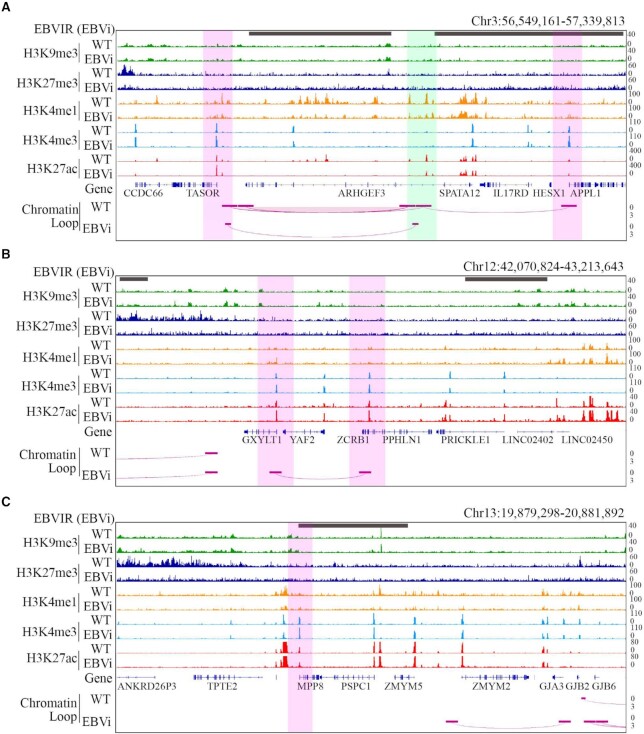

The EBV genome tethers in the proximity to the TASOR enhancer and leads to loop formation between the TASOR enhancer and promoter

To explore the mechanism of TASOR up-regulation in EBV-infected cells, we first investigated the histone modification on the TASOR promoter in MKN7 and MKN7_EBVi cells. ChIP-seq data revealed an overall low suppressive histone modification at this genomic locus (Figure 5A). We observed a 1.7-fold increase of H3K27ac signal and a 1.3-fold increase of H3K4me3 signal on the TASOR promoter in MKN7_EBVi cells compared with MKN7 cells, which is consistent with up-regulated TASOR transcription. We also observed continuous H3K4me1/H3K27ac signal peaks while there was a lack of H3K4me3 signal located upstream of the TASOR promoter. This histone modification pattern suggested that this region carries multiple active enhancers. Active enhancers could promote gene transcription by interacting with their target genes through the formation of chromatin loops (53). Therefore, we hypothesized that the formation of a chromatin loop between the TASOR promoter and the active enhancer increased TASOR expression in EBV-infected GC cells.

Figure 5.

The EBV genome tethered in proximity to TASOR and strengthened loop formation between the TASOR enhancer and promoter. Histone ChIP-seq and HiC-seq interaction at TASOR (A), PPHLN1 (B) and MPP8 (C) gene loci in MKN7 and MKN7_EBVi cells. From top to bottom: EBVIRs (gray bar) illustrated by 4C-seq with the EBV genome as bait; tracks showing H3K9me3, H3K27me3, H3K4me3, H3K4me1, H3K27ac signal; and HiC-seq loops for MKN7 and MKN7_EBVi. Interaction strength was demonstrated by the depth of the loop. Promoter, pink shadow; enhancer, green shadow.

To test this hypothesis, we analyzed high-throughput sequencing (Hi-C) data to map cis-regulated interaction in MKN7 and MKN7_EBVi. We identified an enhancer with H3K27ac+/H3K4me1+/H3K4me3- located 325 kb upstream of the TASOR coding region which interacted with the TASOR promoter as well as the APPL1 promoter in MKN7 cells (Figure 5A). The interaction between the enhancer and TASOR promoter was significantly strengthened by ∼3-fold in MKN7_EBVi compared with that in MKN7 (Figure 5A), which indicated that the strengthened interaction between the TASOR promoter and the enhancer might contribute to TASOR up-regulation.

Intriguingly, the H3K27ac and H3K4me1 signal was significantly decreased at a certain region of this multi-enhancer, especially at the ARHGEF3 gene coding region which is located between the TASOR promoter and enhancer. The EBV genome is known to exist as an episomal chromosome tethered to human chromosomes via viral oriP loci by EBNA1 protein. The viral–host genome interaction could induce chromatin topology remodeling that impacts histone modification (22,23). We hypothesized that the alteration of histone modification and loop conformation was related to EBV genome tethering. To test this hypothesis, we explored a 4C-seq dataset of MNK7_EBVi which used the regions both upstream and downstream of oriP proximal DNA of the EBV genome as baits. Regions with overlapped reads using either bait were defined as potential viral genome-tethering sites, named EBV genome interaction regions (EBVIRs). We observed ∼50 EBVIRs on this chromosome in MKN7_EBVi cells which included the ARHGEF3 coding gene body (Figure 5A). This specific EBVIR covered the entire ARHGEF3 coding gene body which coincided with decreased H3K27ac and H3K4me1 modification. We thus proposed that viral genome tethering is a possible contributor to the histone modification and chromatin conformation alteration which occurred at the TASOR promoter/enhancer region.

Similarly, we investigated the impact of EBV–host interaction on MPP8 and PPHLN1. We detected EBVIRs at genomic loci of PPHLN1 and MPP8 using the same approach. We found increased H3K27ac modification at the PPHLN1 promoter and unchanged epigenetic modification of MPP8 promoters in MKN7_EBVi cells (Figure 5B, C), which was in agreement with the increased PPHLN1 and unchanged MPP8 transcription level. No enhancer–promoter interaction as observed at the TASOR locus was detected using Hi-C data. Interestingly, we found an interaction between PPHLN1 and GXYLT1 promoters (Figure 5B), which probably belonged to promoter-anchored chromatin interactions (PAIs) (54) and might be related to co-expression of these two genes.

Together, these results suggest that viral–host genome interaction by EBV genome tethering possibly induced a chromatin topology remodeling at the TASOR locus, which enhances the interaction between the TASOR promoter and enhancer for increased HUSH function.

DISCUSSION

L1-mediated retrotranspositions are closely related to development, aging and diseases. In addition to genetic mutations caused by L1 transposition events, changes in transposon expression are often associated with diseases including autoimmune disorders, neural diseases and cancers (3,4,55). In this study, we investigated the effect of EBV infection on L1 expression and found that L1s were repressed in EBV-infected GC cells. Importantly, we found that young and FL-L1s, a subset of L1s possessing retrotransposition potential, were among those which were significantly repressed. These findings suggested that EBV infection induced a cellular response by selectively repressing the young and FL-L1s, a group of L1s likely to be a threat to genome integrity.

Despite their high abundance in the genome, the activity of L1s is strictly controlled primarily via epigenetic regulation to ensure genome stability. Cells have developed silencing mechanisms to prevent remobilization of transposons. These include RNAi-triggered silencing (56), DNA methylation (7,10) and histone modifications (12–14). EBV induces host genome aberrant histone modification to promote the expresssion of oncogenes and suppressed the transcription of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) in EBVaGC (27,50,57). Those alternations were primarily attributed to the modification on protein-coding genes, non-coding RNA or cis-regulatory elements, such as enhancers and promoters. We found that retrotransposon L1s, widely distributed repeat elements in the human genome, also underwent significant aberrant histone modification in EBV-infected GC cells. H3K9me3, the most common silencing histone modification on L1s in the human genome (10,12), was significantly increased.

The HUSH complex plays important roles in virus genome silencing. The HUSH complex was recently found to transcriptionally repress L1s preferentially targeting at intronic young and FL-L1s by promoting H3K9me3 deposition on those L1s (6,52). Three components, MPP8, PPHLN1 and TASOR, make up the HUSH complex, which recruits two effectors, MORC2 and SETDB1, to promote chromatin compaction and H3K9me3 deposition to silence L1 transcription. TASOR acts as a scaffold protein in the HUSH complex by interacting with MPP8 and PPHLN1, a key process of HUSH complex assembly. In our analysis, we observed an increased expression of TASOR in EBV-infected GC cells. We also found that the H3K9me3 signal level was increased in TASOR-bound L1 regions in EBV-infected GC cells compared with EBVnGC cells, connecting TASOR binding and H3K9me3 enrichment on L1s to EBVaGC. Given that the HUSH complex plays an essential role on L1 repression, it is plausible for us to extrapolate that up-regulated TASOR, the scaffold protein, may promote the complex assembly which leads to L1 repression.

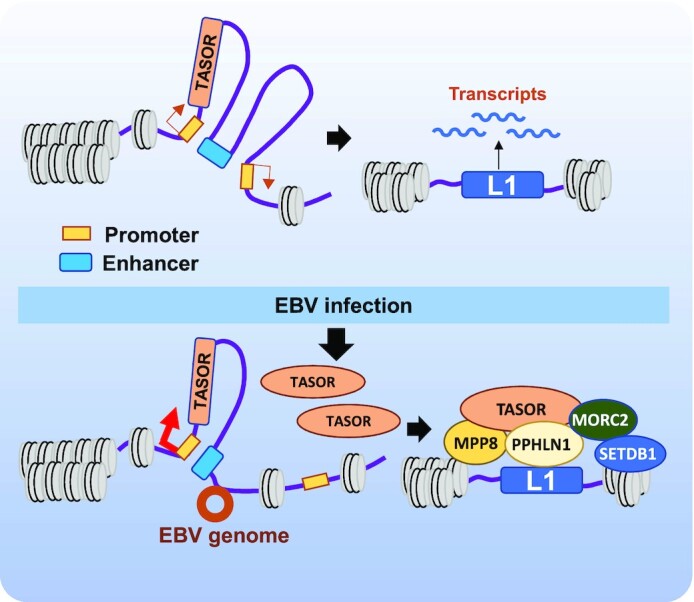

In EBVaGC, the EBV viral genome tethers to the host chromosome, resulting in viral–host genome interaction and causing chromatin topology remodeling (27). We identified two EBV genome-tethering sites in proximity to the TASOR enhancer. Interestingly, the interaction between the TASOR enhancer and promoter was augmented in MNK7_EBVi cells compared with that in MKN7 cells, accompanied by elimination of the interaction between the enhancer and the competing promoter (Figure 5). It is worth noting that the EBV genome favors tethering at H3K9me3-rich regions and release of silenced enhancers (27). Here the EBV genome tethering sites in proximity to the TASOR enhancer is due to lack of H3K9me3 modification. The tethering eliminated an interaction between the enhancer and a promoter, which consequently strengthened the interaction between the enhancer and the second promoter. We thus proposed a model for L1 regulation in EBVaGC cells. The EBV genome is tethered in proximity to the TASOR enhancer which promoted loop formation between the enhancer and the TASOR promoter. The up-regulated TASOR favored HUSH complex assembly, which promoted the deposition of H3K9me3 on L1s, especially the young and FL-L1 elements, and silenced their expression (Figure 6). Taken together, these findings revealed a mechanism of L1 expression regulation via virus-induced chromatin topological remodeling at the genomic locus of the L1 regulator.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of L1 expression regulation by the HUSH complex in EBVaGC. In the absence of the EBV genome, the promoters (yellow rectangle) of TASOR and a neighboring gene share an enhancer (cyan rectangle). TASOR expression is moderately induced and L1 repression is limited, which produces L1 RNA. The viral genome (brown circle) tethers near the TASOR enhancer resulting in a strengthened interaction between the enhancer and the TASOR promoter. TASOR protein (orange oval) stimulates the formation of the HUSH complex, which binds to the intronic young and FL-L1s (blue rectangle) and silences L1.

It is worth noting that all the analyses in this study were performed on EBV-negative and -positive cell lines derived from gastric cancers. These cell lines are critical cell models for studying gastric cancer, which permit us to carry out experiments and analyses to answer some fundamental biological questions related to the disease. Nevertheless, we cannot disregard the limitation of using cell models for disease study. On the other hand, the original sequencing data of EBVaGC cell lines retrieved from the GEO were all performed using a single-ended sequencing approach. Teissandier and colleagues have shown that TE analysis using paired-end reads has a higher true positive rate and mapping percentage compared with single-end reads (58). Future analysis using paired-end reads would be needed to confirm the alteration of L1 expression observed in this study.

EBV infection can cause genome hypermethylation (25,59,60). We could not exclude the possibility that DNA hypermethylation would play an independent role in L1 down-regulation via DNA methylation beyond HUSH repression. DNA methylation could possibly regulate both intronic and intergenic L1s, and potentially other TEs (61). In fact, short interspersed element (SINE) DNA transposons are also down-regulated in EBVaGC (Supplementary Figure S1B). However, LTR retrotransposons are up-regulated in EBVaGC (Supplementary Figure S1B), suggesting that DNA methylation is not sufficient to explain TE down-regulation. Further study should focus on the contribution of aberrant DNA methylation to TE expression in EBVaGC. Besides, although the EBV genome mostly exists as an extrachromosomal molecule via tethering to the host chromosome, Peng and colleagues have identified EBV–host integration sites from extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma tumor biopsies (62). The integration sites were enriched in the repeat regions of the human genome, such as SINEs, LINEs and satellites, suggesting that EBV might have an alternative regulation mechanism on cellular TEs.

As a potential mutagen, L1s possess the potential to cause mutations leading to genome instability (11). In particular, L1HS, the full-length youngest L1 subfamily members retaining retrotransposition competence, in particular are more likely to threaten genome integrity (6,15,52). Here we found that young L1s (such as L1HS and L1PA2) are the most repressed L1 family members in EBVaGC cells, which implies a reduced retrotransposition potential. This might explain why EBVaGC displayed a significantly lower frequency of copy number variation mutations than EBVnGC (23,25). It is also likely that down-regulated L1s can influence the expression of their neighboring genes. Indeed, we found a positive correlation of expression between L1s and neighboring genes (Supplementary Figure S3A, B). By using KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) analysis on the neighboring genes around the 793 down-regulated L1s in MKN7 upon EBV infection, we found that the neighboring genes which are most affected are classified as proteoglycans in cancer, extracellular membrane–receptor interaction, starch and sucrose metabolism, etc. (Supplementary Figure S3C). These data together indicate that down-regulated L1s in EBV-infected cells could impact expression of an L1 neighboring gene which might be related to tumor progression.

L1s are usually recognized as a causative mutagen for cancers. About half of all cancers have somatic integrations of retrotransposons (4). However, the frequency of L1 insertional events varied by cancer types, suggesting that L1 regulation may be altered in different cancer cells. For instance, myeloid malignancies including myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) had a low incidence of L1 retrotransposition (4). Derepression of L1s compellingly inhibited AML development by inducing DNA damage response and cell cycle exit (52). Thus, cancer type-specific L1 regulation and its contribution to cancer development remain largely unknown. Here we found that L1 expression was repressed in EBVaGC, the most common EBV-related tumor (23,24,26). It remains unclear whether the repressed L1s contribute to tumorigenesis in EBVaGC. An interesting observation is that EBVaGC has an up-regulated p53 protein level with a low mutation rate (23,25). It was reported that overactivated L1 expression led to cellular stress and DNA damage in the presence of functional p53 (63). These observations together imply that repressed L1s in EBVaGC might be a cellular strategy to avoid lethal DNA damage. Further studies are needed to fully elucidate the role of L1 in tumorigenesis in EBV-related cancers.

Taken together, our data support a model whereby EBV silences the young and FL-L1 elements through chromatin topology remodeling as a consequence of viral–host genome interaction. This mechanism provides a new aspect for the regulation of L1 expression upon oncogenic virus infection, although the detailed mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets analyzed in the present study are available in the GEO and TCGA (Supplementary Table S1). Detailed information and experiment design can be accessed in previous research (6,25,27,45,46,64,65).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor Michael Chandler from Georgetown University Medical Center for reading the manuscript and for discussions.

Author contributions: S.H., M.Z. and E.L. conceived the study; M.Z., W.S., X.Y., D.X., L.W. and J.Y. performed the experiments and data analysis; M.Z., E.L. and S.H. wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors have approved the current version.

Notes

Present address: Lingling Wang. School of Comprehensive Health Management, Xihua University, Chengdu, 610039, China.

Contributor Information

Mengyu Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Yancheng Medical Research Center, Medical School, Nanjing University, Yancheng 224000, China.

Weikang Sun, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China.

Xiaoxin You, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China.

Dongge Xu, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China.

Lingling Wang, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China.

Jingping Yang, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China.

Erguang Li, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Institute of Medical Virology, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Shenzhen Research Institute of Nanjing University, Shenzhen 518000, China.

Susu He, State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; Yancheng Medical Research Center, Medical School, Nanjing University, Yancheng 224000, China.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [81871636 to E.L.]; Jiangsu Natural Science Foundation [BK20200316 to S.H.]; Central Universities Fundamental Research Funds [14380470 and 14380526 to S.H.]; and the Science, Technology and Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality [JSGG 20200519160755008 to E.L.]. The funding agencies had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Richardson S.R., Salvador-Palomeque C., Faulkner G.J.. Diversity through duplication: whole-genome sequencing reveals novel gene retrocopies in the human population. Bioessays. 2014; 36:475–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burns K.H. Transposable elements in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017; 17:415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kazazian H.H. Jr, Moran J.V. Mobile DNA in health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017; 377:361–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rodriguez-Martin B., Alvarez E.G., Baez-Ortega A., Zamora J., Supek F., Demeulemeester J., Santamarina M., Ju Y.S., Temes J., Garcia-Souto D.et al.. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes identifies driver rearrangements promoted by LINE-1 retrotransposition. Nat. Genet. 2020; 52:306–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pascarella G., Hon C.C., Hashimoto K., Busch A., Luginbuhl J., Parr C., Hin Yip W., Abe K., Kratz A., Bonetti A.et al.. Recombination of repeat elements generates somatic complexity in human genomes. Cell. 2022; 185:3025–3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu N., Lee C.H., Swigut T., Grow E., Gu B., Bassik M.C., Wysocka J.. Selective silencing of euchromatic L1s revealed by genome-wide screens for L1 regulators. Nature. 2018; 553:228–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jonsson M.E., Ludvik Brattas P., Gustafsson C., Petri R., Yudovich D., Pircs K., Verschuere S., Madsen S., Hansson J., Larsson J.et al.. Activation of neuronal genes via LINE-1 elements upon global DNA demethylation in human neural progenitors. Nat. Commun. 2019; 10:3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xiong F., Wang R., Lee J.H., Li S., Chen S.F., Liao Z., Hasani L.A., Nguyen P.T., Zhu X., Krakowiak J.et al.. RNA m6A modification orchestrates a LINE-1–host interaction that facilitates retrotransposition and contributes to long gene vulnerability. Cell Res. 2021; 31:861–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burns K.H. Our conflict with transposable elements and its implications for human disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2020; 15:51–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deniz O., Frost J.M., Branco M.R.. Regulation of transposable elements by DNA modifications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019; 20:417–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pappalardo X.G., Barra V.. Losing DNA methylation at repetitive elements and breaking bad. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2021; 14:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Healton S.E., Pinto H.D., Mishra L.N., Hamilton G.A., Wheat J.C., Swist-Rosowska K., Shukeir N., Dou Y., Steidl U., Jenuwein T.et al.. H1 linker histones silence repetitive elements by promoting both histone H3K9 methylation and chromatin compaction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020; 117:14251–14258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. He Q., Kim H., Huang R., Lu W., Tang M., Shi F., Yang D., Zhang X., Huang J., Liu D.et al.. The Daxx/Atrx complex protects tandem repetitive elements during DNA hypomethylation by promoting H3K9 trimethylation. Cell Stem Cell. 2015; 17:273–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ishak C.A., Marshall A.E., Passos D.T., White C.R., Kim S.J., Cecchini M.J., Ferwati S., MacDonald W.A., Howlett C.J., Welch I.D.et al.. An RB–EZH2 complex mediates silencing of repetitive DNA sequences. Mol. Cell. 2016; 64:1074–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Payer L.M., Burns K.H.. Transposable elements in human genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019; 20:760–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wei J., Yu X., Yang L., Liu X., Gao B., Huang B., Dou X., Liu J., Zou Z., Cui X.L.et al.. FTO mediates LINE1 m6A demethylation and chromatin regulation in mESCs and mouse development. Science. 2022; 376:968–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Macchietto M.G., Langlois R.A., Shen S.S.. Virus-induced transposable element expression up-regulation in human and mouse host cells. Life Sci. Alliance. 2020; 3:e201900536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ahuja A., Journo G., Eitan R., Rubin E., Shamay M.. High levels of LINE-1 transposable elements expressed in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related primary effusion lymphoma. Oncogene. 2021; 40:536–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schobel A., Nguyen-Dinh V., Schumann G.G., Herker E.. Hepatitis C virus infection restricts human LINE-1 retrotransposition in hepatoma cells. PLoS Pathog. 2021; 17:e1009496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sudhindar P.D., Wainwright D., Saha S., Howarth R., McCain M., Bury Y., Saha S.S., McPherson S., Reeves H., Patel A.H.et al.. HCV activates somatic L1 retrotransposition—a potential hepatocarcinogenesis pathway. Cancers (Basel). 2021; 13:5079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li Y., Yang J., Shen S., Wang W., Liu N., Guo H., Wei W.. SARS-CoV-2-encoded inhibitors of human LINE-1 retrotransposition. J. Med. Virol. 2022; 95:e28135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Young L.S., Yap L.F., Murray P.G.. Epstein–Barr virus: more than 50 years old and still providing surprises. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016; 16:789–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang J., Liu Z., Zeng B., Hu G., Gan R.. Epstein–Barr virus-associated gastric cancer: a distinct subtype. Cancer Lett. 2020; 495:191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Farrell P.J. Epstein–Barr virus and cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2019; 14:29–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014; 513:202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khan G., Fitzmaurice C., Naghavi M., Ahmed L.A.. Global and regional incidence, mortality and disability-adjusted life-years for Epstein–Barr virus-attributable malignancies, 1990–2017. BMJ Open. 2020; 10:e037505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Okabe A., Huang K.K., Matsusaka K., Fukuyo M., Xing M., Ong X., Hoshii T., Usui G., Seki M., Mano Y.et al.. Cross-species chromatin interactions drive transcriptional rewiring in Epstein–Barr virus-positive gastric adenocarcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2020; 52:919–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. You J., Croyle J.L., Nishimura A., Ozato K., Howley P.M.. Interaction of the bovine papillomavirus E2 protein with Brd4 tethers the viral DNA to host mitotic chromosomes. Cell. 2004; 117:349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim K.D., Tanizawa H., De Leo A., Vladimirova O., Kossenkov A., Lu F., Showe L.C., Noma K.I., Lieberman P.M.. Epigenetic specifications of host chromosome docking sites for latent Epstein–Barr virus. Nat. Commun. 2020; 11:877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang L., Laing J., Yan B., Zhou H., Ke L., Wang C., Narita Y., Zhang Z., Olson M.R., Afzali B.et al.. Epstein–Barr virus episome physically interacts with active regions of the host genome in lymphoblastoid cells. J. Virol. 2020; 94:e01390-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang R., Strong M.J., Baddoo M., Lin Z., Wang Y.P., Flemington E.K., Liu Y.Z.. Interaction of Epstein–Barr virus genes with human gastric carcinoma transcriptome. OncoTargets Ther. 2017; 8:38399–38412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R.. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013; 29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heinz S., Benner C., Spann N., Bertolino E., Lin Y.C., Laslo P., Cheng J.X., Murre C., Singh H., Glass C.K.. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell. 2010; 38:576–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leek J.T. svaseq: removing batch effects and other unwanted noise from sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:e161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S.. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014; 15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Langmead B., Salzberg S.L.. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012; 9:357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Quinlan A.R., Hall I.M.. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010; 26:841–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ramirez F., Ryan D.P., Gruning B., Bhardwaj V., Kilpert F., Richter A.S., Heyne S., Dundar F., Manke T.. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:W160–W165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Robinson J.T., Thorvaldsdottir H., Winckler W., Guttman M., Lander E.S., Getz G., Mesirov J.P.. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011; 29:24–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Servant N., Varoquaux N., Lajoie B.R., Viara E., Chen C.J., Vert J.P., Heard E., Dekker J., Barillot E.. HiC-Pro: an optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biol. 2015; 16:259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Durand N.C., Shamim M.S., Machol I., Rao S.S., Huntley M.H., Lander E.S., Aiden E.L.. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 2016; 3:95–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cai M., Gao F., Lu W., Wang K.. w4CSeq: software and web application to analyze 4C-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2016; 32:3333–3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Asakawa Y., Okabe A., Fukuyo M., Li W., Ikeda E., Mano Y., Funata S., Namba H., Fujii T., Kita K.et al.. Epstein–Barr virus-positive gastric cancer involves enhancer activation through activating transcription factor 3. Cancer Sci. 2020; 111:1818–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ebert K., Zwingenberger G., Barbaria E., Keller S., Heck C., Arnold R., Hollerieth V., Mattes J., Geffers R., Raimúndez E.et al.. Determining the effects of trastuzumab, cetuximab and afatinib by phosphoprotein, gene expression and phenotypic analysis in gastric cancer cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2020; 20:1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Namba-Fukuyo H., Funata S., Matsusaka K., Fukuyo M., Rahmutulla B., Mano Y., Fukayama M., Aburatani H., Kaneda A.. TET2 functions as a resistance factor against DNA methylation acquisition during Epstein–Barr virus infection. OncoTargets Ther. 2016; 7:81512–81526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ooi W.F., Xing M., Xu C., Yao X., Ramlee M.K., Lim M.C., Cao F., Lim K., Babu D., Poon L.F.et al.. Epigenomic profiling of primary gastric adenocarcinoma reveals super-enhancer heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 2016; 7:12983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Khan H., Smit A., Boissinot S.. Molecular evolution and tempo of amplification of human LINE-1 retrotransposons since the origin of primates. Genome Res. 2006; 16:78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Giordano J., Ge Y., Gelfand Y., Abrusan G., Benson G., Warburton P.E.. Evolutionary history of mammalian transposons determined by genome-wide defragmentation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007; 3:e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lanciano S., Cristofari G.. Measuring and interpreting transposable element expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020; 21:721–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Okabe A., Funata S., Matsusaka K., Namba H., Fukuyo M., Rahmutulla B., Oshima M., Iwama A., Fukayama M., Kaneda A.. Regulation of tumour related genes by dynamic epigenetic alteration at enhancer regions in gastric epithelial cells infected by Epstein–Barr virus. Sci. Rep. 2017; 7:7924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Freeman B., White T., Kaul T., Stow E.C., Baddoo M., Ungerleider N., Morales M., Yang H., Deharo D., Deininger P.et al.. Analysis of epigenetic features characteristic of L1 loci expressed in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022; 50:1888–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gu Z., Liu Y., Zhang Y., Cao H., Lyu J., Wang X., Wylie A., Newkirk S.J., Jones A.E., Lee M. Jret al.. Silencing of LINE-1 retrotransposons is a selective dependency of myeloid leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2021; 53:672–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Furlong E.E.M., Levine M.. Developmental enhancers and chromosome topology. Science. 2018; 361:1341–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wu Y., Qi T., Wang H., Zhang F., Zheng Z., Phillips-Cremins J.E., Deary I.J., McRae A.F., Wray N.R., Zeng J.et al.. Promoter-anchored chromatin interactions predicted from genetic analysis of epigenomic data. Nat. Commun. 2020; 11:2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Thomas C.A., Tejwani L., Trujillo C.A., Negraes P.D., Herai R.H., Mesci P., Macia A., Crow Y.J., Muotri A.R.. Modeling of TREX1-dependent autoimmune disease using human stem cells highlights L1 accumulation as a source of neuroinflammation. Cell Stem Cell. 2017; 21:319–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zoch A., Auchynnikava T., Berrens R.V., Kabayama Y., Schöpp T., Heep M., Vasiliauskaitė L., Pérez-Rico Y.A., Cook A.G., Shkumatava A.et al.. SPOCD1 is an essential executor of piRNA-directed de novo DNA methylation. Nature. 2020; 584:635–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li W., Okabe A., Usui G., Fukuyo M., Matsusaka K., Rahmutulla B., Mano Y., Hoshii T., Funata S., Hiura N.et al.. Activation of EHF via STAT3 phosphorylation by LMP2A in Epstein–Barr virus-positive gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021; 112:3349–3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Teissandier A., Servant N., Barillot E., Bourc’his D.. Tools and best practices for retrotransposon analysis using high-throughput sequencing data. Mob. DNA. 2019; 10:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chen Z.H., Yan S.M., Chen X.X., Zhang Q., Liu S.X., Liu Y., Luo Y.L., Zhang C., Xu M., Zhao Y.F.et al.. The genomic architecture of EBV and infected gastric tissue from precursor lesions to carcinoma. Genome Med. 2021; 13:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Matsusaka K., Kaneda A., Nagae G., Ushiku T., Kikuchi Y., Hino R., Uozaki H., Seto Y., Takada K., Aburatani H.et al.. Classification of Epstein–Barr virus-positive gastric cancers by definition of DNA methylation epigenotypes. Cancer Res. 2011; 71:7187–7197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ewing A.D., Smits N., Sanchez-Luque F.J., Faivre J., Brennan P.M., Richardson S.R., Cheetham S.W., Faulkner G.J.. Nanopore sequencing enables comprehensive transposable element epigenomic profiling. Mol. Cell. 2020; 80:915–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Peng R.J., Han B.W., Cai Q.Q., Zuo X.Y., Xia T., Chen J.R., Feng L.N., Lim J.Q., Chen S.W., Zeng M.S.et al.. Genomic and transcriptomic landscapes of Epstein–Barr virus in extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2019; 33:1451–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ardeljan D., Steranka J.P., Liu C., Li Z., Taylor M.S., Payer L.M., Gorbounov M., Sarnecki J.S., Deshpande V., Hruban R.H.et al.. Cell fitness screens reveal a conflict between LINE-1 retrotransposition and DNA replication. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020; 27:168–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cristescu R., Lee J., Nebozhyn M., Kim K.M., Ting J.C., Wong S.S., Liu J., Yue Y.G., Wang J., Yu K.et al.. Molecular analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. Nat. Med. 2015; 21:449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ebert K., Zwingenberger G., Barbaria E., Keller S., Heck C., Arnold R., Hollerieth V., Mattes J., Geffers R., Raimundez E.et al.. Determining the effects of trastuzumab, cetuximab and afatinib by phosphoprotein, gene expression and phenotypic analysis in gastric cancer cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2020; 20:1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets analyzed in the present study are available in the GEO and TCGA (Supplementary Table S1). Detailed information and experiment design can be accessed in previous research (6,25,27,45,46,64,65).