Abstract

Background

Pancreatic cancer often presents as locally advanced (LAPC) or borderline resectable (BRPC). Neoadjuvant systemic therapy is recommended as initial treatment. It is currently unclear what chemotherapy should be preferred for patients with BRPC or LAPC.

Methods

We performed a systematic review and multi-institutional meta-analysis of patient-level data regarding the use of initial systemic therapy for BRPC and LAPC. Outcomes were reported separately for tumor entity and by chemotherapy regimen including FOLFIRINOX (FIO) or gemcitabine-based.

Results

A total of 23 studies comprising 2930 patients were analyzed for overall survival (OS) calculated from the beginning of systemic treatment. OS for patients with BRPC was 22.0 months with FIO, 16.9 months with gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (Gem/nab), 21.6 months with gemcitabine/cisplatin or oxaliplatin or docetaxel or capecitabine (GemX), and 10 months with gemcitabine monotherapy (Gem-mono) (p < 0.0001). In patients with LAPC, OS also was higher with FIO (17.1 months) compared with Gem/nab (12.5 months), GemX (12.3 months), and Gem-mono (9.4 months; p < 0.0001). This difference was driven by the patients who did not undergo surgery, where FIO was superior to other regimens. The resection rates for patients with BRPC were 0.55 for gemcitabine-based chemotherapy and 0.53 with FIO. In patients with LAPC, resection rates were 0.19 with Gemcitabine and 0.28 with FIO. In resected patients, OS for patients with BRPC was 32.9 months with FIO and not different compared to Gem/nab, (28.6 months, p = 0.285), GemX (38.8 months, p = 0.1), or Gem-mono (23.1 months, p = 0.083). A similar trend was observed in resected patients converted from LAPC.

Conclusions

In patients with BRPC or LAPC, primary treatment with FOLFIRINOX compared with Gemcitabine-based chemotherapy appears to provide a survival benefit for patients that are ultimately unresectable. For patients that undergo surgical resection, outcomes are similar between GEM+ and FOLFIRINOX when delivered in the neoadjuvant setting.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1245/s10434-023-13353-2.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma remains among the leading causes of cancer-related mortality.1–3 Most patients present with an advanced stage of disease, e.g., distant metastasis, or locally advanced (LAPC) or borderline resectable (BRPC) pancreatic cancer, ultimately resulting in a dismal 10-15% upfront resection rate and poor 5-year survival.2 In patients with BRPC or LAPC, primary chemotherapy with or without chemoradiation, hypofractionated radiotherapy, or stereotactic body radiotherapy has become increasingly utilized for local downstaging to enable a potentially curable resection. To this end, FOLFIRINOX (FIO) and Gemcitabine-based regimens (GEM+) are commonly used for primary treatment of pancreatic cancer.4–6 Generally, neoadjuvant FIO has been favored based on extrapolation of favorable outcomes in the adjuvant setting; however, this regimen carries a significant toxicity burden limiting use to patients with an excellent performance status.7,8 Gemcitabine continues to be used for its moderate side effect profile and is commonly paired with other therapies (GEM+) with increased biological activity.6–9 While PRODIGE 24 favored FIO over gemcitabine monotherapy in the adjuvant setting, these findings have yet to be demonstrated in the neoadjuvant setting with high level data.6–9 Prospective series investigating this question are available, but often include a limited number of patients, and are usually highly heterogeneous due to the combination of patients with resectable tumors, BRPC, and LAPC, which limit the ability to assess the impact of the type of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on surgical resection rate, positive margin rate, and survival.6,8,10,11

Thus, the objective of this study was to summarize the current evidence regarding initial systemic treatment for LAPC and BRPC through a multi-institutional meta-analysis of patient-level data from high-volume pancreatic centers. The primary goal of our meta-analysis was to assess the impact of primary chemotherapy, FIO, or GEM+ regimens on survival rates of patients with BRPC and LAPC. Secondary outcomes included resection rates, R0 resection rates, and impact of radiotherapy.

Methods

Study Search and Selection

The systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted following the PRISMA guidelines.12 The review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database.13 The databases of Medline, Scopus Embase, and Cochrane were systematically searched for relevant clinical studies in English by a dedicated librarian without time restrictions in May 2020. The complete search strategy was provided in Appendix 1. The reference list of included studies was crosschecked manually to identify additional studies. All clinical studies reporting patients with primary pancreatic cancer without distant metastasis, who received primary FIO or GEM+ regimens, were included. Change in treatment regimen after initial treatment was not an exclusion criterion. Case series with less than ten patients, conference abstracts, letters, reviews, study protocols, and other type of nonoriginal articles were excluded.

Data Collection and Outcome Measures

After removal of duplicates, two reviewers (D.E. and B.A.) independently screened all articles for relevance. Decision of article inclusion in the meta-analysis was done after full-text assessment, and discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus. The following data were collected for meta-analysis: institution, study design, study population, tumor type (LAPC and BRPC), chemotherapy regimen, radiotherapy application, resection rate, R0 resection rate, and overall and disease-free survival. If study design was not clearly stated otherwise, the study was classified as a retrospective study. For survival analysis, we obtained patient level data from the studies listed in Table 1. Patients with available survival data from the time of systemic treatment were considered for the “full treatment population,” regardless of surgery at later timepoints. Secondary outcomes included resection rates, receipt of radiotherapy, R0 resection rates, and progression-free survival. Progression-free survival was calculated from the start of primary treatment.

Statistical Methods

The individual patient-level data analysis included available time-to-event data from participating centers. Median follow-up time was estimated with the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. Time-to-event outcomes were visualized with the Kaplan Meier method. Hazard ratios for the comparison of FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine-based regimens were estimated and reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Survival analysis also was reported separately for resected and nonresected patients. The analysis did not account for clustering within centers. A meta-analysis was performed with dichotomous outcomes on study level in single groups, noncomparative data.14 Due to the expected heterogeneity of included studies, the random effects meta-analysis results were considered most relevant. Single-group, noncomparative data were estimated from all included studies, and proportions were reported either for FOI or GEM+ arm. These results were reported with 95% CIs. These results were reported as risk ratios (RR) with 95% CI. The heterogeneity was evaluated according to Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions with I2 statistics.15 I2 statistics was interpreted as follows: 0-40% not relevant heterogeneity; 30-60% moderate heterogeneity; 50-90% substantial heterogeneity; 75-100% considerable heterogeneity. Two-sided p-values were calculated in all analyses. The statistical programming language R, version 4.0.3 was used for survival analyses.

Role of the Funding Source

There was no funding for this systematic review with meta-analysis.

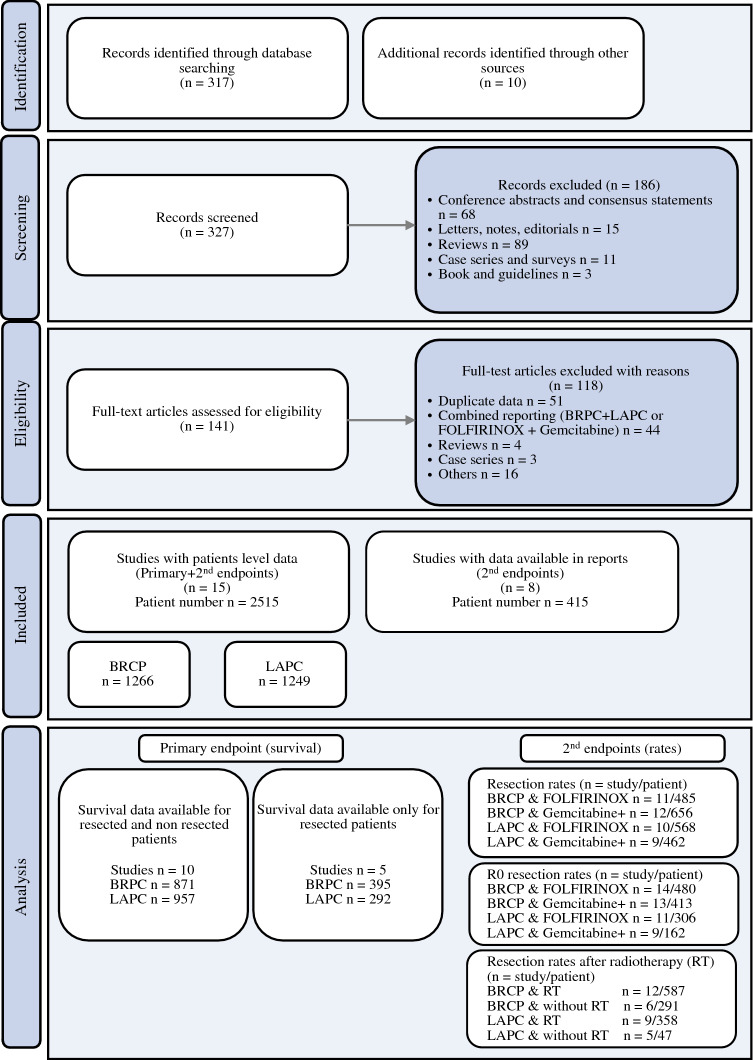

Results Included Studies and Descriptive Data

The systematic literature review identified 317 potential studies, and 10 studies were additionally identified manually. Of those, a total of 23 studies included 2,930 patients in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Of these publications, authors of 15 studies provided individual patient-level data for the 2,515 patients6,10,16–28 included in the survival analysis. Among the eight studies without patient level data, one is a randomized, controlled trial,29 four are prospective,30–33 and three retrospective observational studies.34–36 The majority of studies (n = 18) included patients from the start of systemic treatment. Five studies reported only patients undergoing resection. One of the main criteria for study exclusion during full-text assessment was combined reporting of BRPC together with LAPC, or FIO with GEM+. Therefore, separation of data for LAPC and BRPC was possible in all included studies reporting both tumor entities. For the definition of BRPC or LAPC, most studies used NCCN criteria (13 studies; Table 1). In ten studies, either GEM+ or FIO was used as systemic treatment; six studies report FIO only, in two of those studies a modified FIO (dose reduction to 75%) regimen was used, and seven studies report only GEM+. Radiotherapy (conventionally fractionated, hypofractionated, or stereotactic) was delivered in 19 studies.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart

Overall Survival Analysis

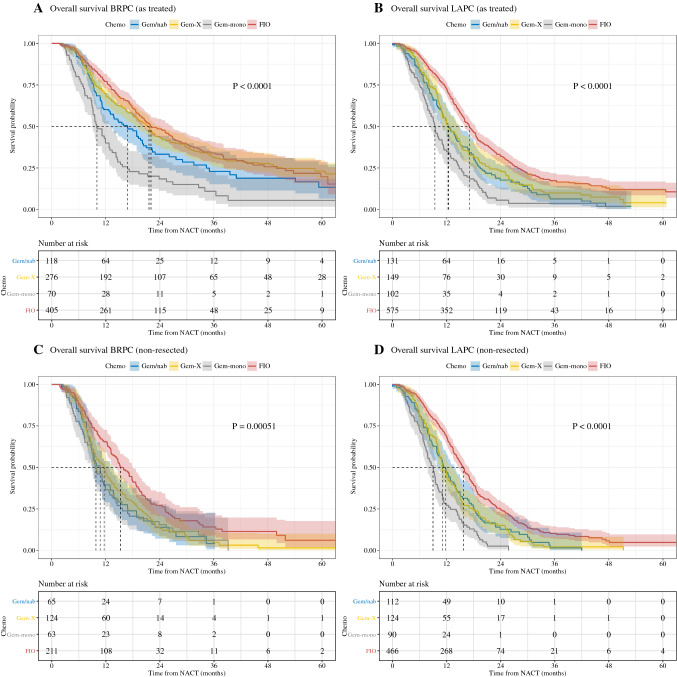

Overall survival was analyzed for patients “as treated,” based on diagnosis with BRPC and LAPC (Fig. 2). This analysis includes (n = 10) studies reporting on patient outcomes after the initialization of systemic treatment. Series reporting resected patients only (n = 5) were therefore excluded. Data were available for 869 BRPC patients with median follow-up of 44 months and for 957 LAPC patients with median follow-up of 37.9 months. We separately performed post-hoc overall survival analyses for the following groups: FIO, gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (Gem/nab), gemcitabine/cisplatin or oxaliplatin or docetaxel or capecitabine (GemX), and gemcitabine monotherapy (Gem-mono). For patients with BRPC, median overall survival for FIO was 22.0 months (95% CI 20.03–26.8), Gem/nab 16.9 months (95% CI 13.0–20.4), GemX 21.6 months (95% CI 18.7–24.0), and Gem-mono 10.1 months (95% CI 9.17–12.9; Fig. 2A). There was a statistically significant difference in overall survival across compared groups (p < 0.0001). In post-hoc analysis of FIO with other GEM+ regimens, a survival advantage for FIO was observed compared with Gem/nab (p = 0.012; hazard ratio of 0.718 (95% CI 0.555-0.929)) and Gem-mono (p < 0.0001; hazard ratio of 0.410 (95% CI 0.302-0.543)), while GemX disclosed the similar survival (p = 0.525; hazard ratio of 0.939 (95% CI 0.773-1.14)).

Fig. 2.

Overall survival with pooled, patient-level data for the intention for full treatment population (A, B) and non-resected patients (C, D) according to treatment regimen groups. BRPC borderline resectable pancreatic cancer; LAPC locally advanced pancreatic cancer; FIO FOLFIRINOX; GEM/nab gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel; GemX gemcitabine/cisplatin or oxaliplatin or docetaxel or capecitabine; Gem-mono gemcitabine as monotherapy; ITT full treatment cohort

In patients with LAPC, the overall survival for FIO was 17.1 months (95% CI 16–18.5), compared with Gem/nab 12.5 months (95% CI 11.1–15.0), GemX 12.3 months (95% CI 11.1–14.9), and Gem-mono 9.4 months (95% CI 8.3–11.1; Fig. 2B). There was a statistically significant difference across compared groups (p < 0.0001). In post-hoc analysis, a survival advantage associated with FIO was observed compared with all GEM+ treatments (Gem/nab, GemX and Gem-mono p < 0.001 with hazard ratio of 0.618 (95% CI 0.500-0.763), 0.683 (95% CI 0.559-0.833), and 0.391 (95% CI 0.312-0.491) respectively).

Survival in Unresected Patients

Patients without pancreatic tumor resection were analyzed separately as survival in pancreas cancer is heavily influenced by the ability to undergo resection. Data were available for 463 patients with BRPC and 792 patients with LAPC. In a separate analysis of nonresected patients, initially diagnosed as BRPC, overall survival for FIO was 15.3 months (95% CI 14–18), Gem/nab 10.8 months (95% CI 9.0–13.7), GemX 11.7 months (95% CI 9.7–13.4) and Gem-mono 9.8 months (95% CI 8.9–12.8). There was a statistically significant difference across compared groups (p = 0.0005) (Fig. 2C). In post hoc analysis of FIO with other GEM+ regimens, a survival advantage associated with FIO was observed (Gem/nab p = 0.003; hazard ratio of 0.620 (95% CI 0.452 to 0.850), GemX p = 0.002; hazard ratio of 0.676 (95% CI 0.528-0.865) and Gem-mono p = 0.001; hazard ratio of 0.600 (95% CI 0.442-0.816).

In patients with LAPC without resection, overall survival for FIO was 15.7 months (95% CI 14.7–17.0), Gem/nab 11.8 months (95% CI 10.0–13.8), GemX 11.1 months (95% CI 10.4–12.1) and Gem-mono 9.0 months (95% CI 7.7–10.0) (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2D). In post hoc analysis, FIO was associated with a survival advantage compared with all GEM+ regimens (Gem/nab, GemX, and Gem-mono p < 0.0001 with hazard ratio of 0.627 (95% CI 0.5-0.786), 0.622 (95% CI 0.504-0.768) and 0.361 (95% CI 0.283-0.460) respectively).

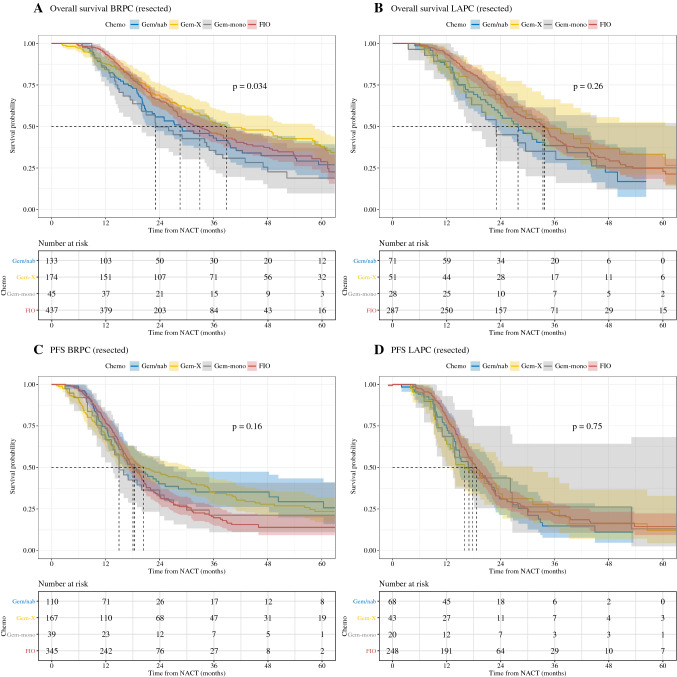

Survival in Resected Patients

In analysis of all resected BRPC patients, patient level data were available for 789 patients with a median follow-up time of 46.4 months. In patients initially staged as BRPC and resected, median overall survival was 32.9 months (95% CI 28.9–38.2) for FIO, 28.6 months (95% CI 22.4–39.7) for Gem/nab, 38.8 months (95% CI 33.0–58.5) for GemX, and 23.1 months (95% CI 20.0–38.0) for Gem-mono (Fig. 3A). Overall, there was a statistically significant difference in compared groups (p = 0.034). However in post-hoc analysis, there was no statistically significant difference between FIO and other GEM+ regimens (Gem/nab p = 0.267; hazard ratio of 0.859 (95% CI 0.529-1.124), GemX p = 0.155; hazard ratio of 1.193 (95% CI 0.935-1.52), and Gem-mono p = 0.069; hazard ratio of 0.714 (95% CI 0.496-1.027)).

Fig. 3.

Overall (A, B) and progression-free (C, D) survival with pooled patient level data for resected patients, according to treatment regimen groups. BRPC borderline resectable pancreatic cancer; LAPC locally advanced pancreatic cancer; FIO FOLFIRINOX; GEM/nab gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel; GemX gemcitabine/cisplatin or oxaliplatin or docetaxel or capecitabine; Gem-mono gemcitabine as monotherapy; ITT full treatment cohort

Of 437 patients with LAPC who underwent radical pancreatic surgery, the median follow-up was 44.5 months. Median overall survival was for FIO 33.4 months (95% CI 29.0–36.3), for Gem/nab 27.9 months (95% CI 22.7–38.8), for GemX 33.7 months (95% CI 25.3– 73.3), and for Gem-mono 23 months (lower bound of 95% CI 17.6) (p = 0.26; Fig. 3B). In post-hoc analysis of FIO with GEM+ regimens, no survival advantage of FIO was observed (Gem/nab p = 0.116; hazard ratio of 0.768 (95% CI 0.552 to 1.068), GemX p = 1.0 hazard ratio of 1 (95% CI 0.683-1.466), and Gem-mono p = 0.167; hazard ratio of 0.714 (95% CI 0.444-1.151).

There was no difference in disease-free survival by chemotherapy regimen for resected BRPC patients (p = 0.16, Fig. 3C) or resected LAPC patients (p = 0.75, Fig. 3D). Disease-free survival in BRCP was 18.1 months (95% CI 17.0–20.0) for FIO, 18.4 months (95% CI 15.9–28.2) for Gem/nab, 20.5 months (95% CI 15.4–30.9) for GemX, and 15 months (95% CI 13.3–27.1) for Gem-mono. Disease-free survival for patients with LAPC was 18.7 months (95% CI 17.0–20.8) for FIO, 17 months (95% CI 14.1–22.8) for Gem/nab, 16 months (95% CI 12.9–31.2) for GemX, and 17.7 months (lower bound of 95% CI 13.4) for Gem-mono.

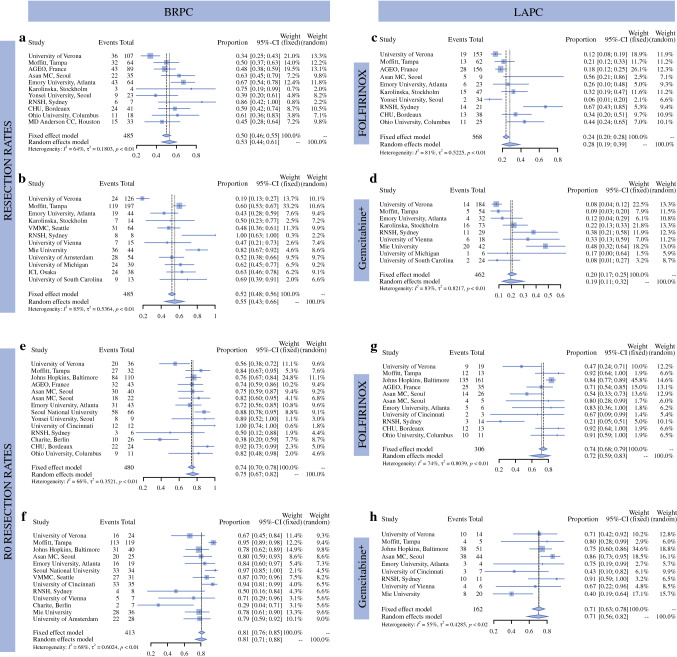

Meta-Analysis of Secondary Endpoints

Secondary analyses of overall resection rate, R0 resection rate, and resection rate after radiation therapy for patients with these reported endpoints: For patients with BRPC, the overall resection rates were 0.53 and 0.55, and R0 resection rates were 0.75 and 0.81 for FIO and GEM+ regimens, respectively. In patients with LAPC, overall resection rates were 0.28 and 0.19, and R0 resection rates were 0.72 and 0.71 for FIO and GEM+ regimens, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis of resection and R0-resection rates. a, b: Resection rates for patients with BRCP or LAPC after FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine+. c, d: Resection rates in patients with LAPC after FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine+. e, f: R0 resection rates in patients with BRCP after FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine+. g, h: R0 resection rates in patients with LAPC after FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine+. Overall, we observed a substantial heterogeneity (I2) in all analyses

Details regarding technique and dose of radiotherapy were lacking from most studies. Thus, we combined chemotherapy regimens and explored the value of radiotherapy in increasing the resection rate in the preoperative setting for BRPC and LAPC. In BRPC, resection rates with and without radiotherapy were 0.58 and 0.51. For LAPC, resection rates with and without radiotherapy were 0.24 and 0.21 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Discussion

This study is the largest, systematic review and multi-institutional, patient-level meta-analysis to examine the impact of neoadjuvant systemic treatment with FOLFIRINOX (FIO) or gemcitabine-based regimens (GEM+) in patients with BRPC or LAPC. Our data suggest the superiority of FIO over GEM+ in both the BRPC and LAPC patient population. However, this benefit is driven in patients who do not undergo surgery. In patients who ultimately undergo resection, the survival outcomes were similar. It may be argued that including patients who received gemcitabine, monotherapy may be considered a palliative treatment and multiagent chemotherapy should be favored whenever possible.

In the setting of primary, resectable pancreatic cancer, surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy remains the standard approach. However, neoadjuvant therapy is being increasingly utilized in this setting as evidenced by the increase number of clinical trials.37 Over the past decades, major advances in novel combination drug therapies and aggressive dose adjustments have significantly improved patient outcomes in the adjuvant setting. Dismal outcomes with 5-FU monotherapy was supplanted by significant survival improvements with the introduction of gemcitabine in 1997.38 Today, FOLFIRINOX and multidrug, gemcitabine-based regimens have shown benefits in the adjuvant and palliative settings and are now a standard of care.7,39,40 In contrast to primary, resectable pancreatic cancer, data suggest that patients with BRPC or LAPC have improved outcomes when treated with primary chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy.29,41,42 Based on the success of FOLFIRINOX and GEM+ in the palliative setting, these combination regimens are currently used as preoperative systemic treatment for BRPC and LAPC. There are two available meta-analysis with patient level data examining survival outcomes for FOLFIRINOX-based treatments for BRPC.43,44 This paucity of data has left significant knowledge gaps for high-level data for other important clinical outcomes (such as resectability and progression-free survival) as well as optimal treatment of patients with LAPC. A recent, multicenter, phase II study from Germany evaluated Gemcitabine/nab-Paclitaxel versus FOLFIRINOX in patients after initial treatment with two cycles of Gemcitabine/nab-Paclitaxel and found similar conversion and survival rates in both arms; however, this was not a direct comparison of these regimens.45 Comparison of the two regimens within two, single-institution, cohort studies did not favor either treatment strategy as both resulted in similar survival rates.6,8 In patients who do not undergo surgery, our results suggest improved survival rates for patients treated with FOLFIRINOX compared with gemcitabine-based regimens. However, this result was influenced by the outcome of nonresected patients. In patients who underwent resection, we did not observe a benefit for FOLFIRINOX neither in BRPC nor in LAPC. This finding suggests that surgical resection of the tumor remains a critical driver of survival, and the type of chemotherapy may be less important than the duration and sequencing of treatment. Clearly, conversion to surgical resectability also represents the biology of the tumor, implying a less aggressive or chemosensitive tumor.

To evaluate outcomes, particularly after surgery, it is critical to stratify by the local stage of the pancreatic tumor. During the past years, the concept of BRPC and LAPC evolved and is currently defined by the tumor involvement of the celiac and mesenteric arteries and the portal vein/superior mesenteric vein.46 It is important to mention that there is significant heterogeneity in the definitions of BRPC or LAPC across institutions.47 Moreover, combined reporting of LAPC and BRPC may significantly skew the results, depending on the number of included entities, which was the case in previous meta-analyses. The ability to analyze these patient groups separately is a primary strength of this study. Indeed, the resection rate in two previous meta-analyses differed from 28% to 68% due to the pooling of BRPC and LAPC patients one of these studies.43,44 The importance of the distinction between BRPC and LAPC is highlighted in this study with the observation that BRPC could be resected in approximately half of the patients after systemic chemotherapy, whereas less than a third of LAPC patients underwent definitive surgical resection after neoadjuvant treatment.

Despite advanced local stage, the R0 resection rates in BRPC and LAPC were high (0.71-0.81) and are well above a recently reported benchmark for pancreatoduodenectomy where R0 resection rates of at least 0.61 were proposed for primary resectable pancreatic cancer.48 This high R0 resection rate reflects the experience of the included centers and but also may belay the benefit of aggressive neoadjuvant treatment, because these high R0 rates were achieved despite more advanced disease.

Due to a lack of comparative data in our analysis, no definitive conclusion should be drawn regarding the effect of neoadjuvant or definitive radiotherapy, which is similar to limitations discussed in previous meta-analyses.41,43 There is significant heterogeneity in the treatment fields, biologically effective dose (BED), and fractionation between institutions in treatment of pancreatic cancer. Furthermore, the combination of different modalities in the neoadjuvant setting often precludes current interpretation of a distinct role of one technique over the other. For example, in the recently published, Dutch, PREOPANC-1 study, patients with BRPC were randomized between immediate surgery and primary moderately hypofractionated chemoradiotherapy with Gemcitabine.29 Preoperative chemoradiotherapy provided a significant overall survival benefit, but the added value of radiotherapy in addition to chemotherapy remains unclear. To this end, the LAP07 trial was unable to demonstrate a survival benefit in the addition of conventionally fractionated, low-BED radiotherapy to gemcitabine monotherapy for LAPC; however, there was a 14% improvement in local control.49 More recent evidence favors stereotactic radiotherapy as delivered in LAPC-1 after FOLFIRINOX, which demonstrated a survival benefit, but lacks a comparative group not treated with of radiotherapy.50 Finally, for unresected patients, ablative doses approaching 100 Gy BED may be associated with the best outcomes for LAPC,51 and new technology, such as MRI-guided, adaptive radiotherapy, may facilitate delivery of this treatment safely.52 The Alliance for Clinical Oncology Trial A021501compared mFOLFIRINOX with and without hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients with BRPC. The arm with hypofractionated radiotherapy disclosed 67% R1 resection rate, whereas the other arm 43%. This randomized, controlled trial concluded that mFOLFIRINOX alone is superior compared with mFOLFIRINOX plus hypofractionated radiotherapy in neoadjuvant setting. However, this randomized, controlled trial terminated prematurely and is ultimately underpowered to report the value of the addition of hypofractionated radiotherapy for patients with BRPC.53–55

We acknowledge the limitations of this meta-analysis. There is clearly a lack of prospectively collected, randomized data comparing FOLFIRINOX with gemcitabine-based regimens in patients with BRPC or LAPC. Therefore, the choice of the regimen is left to the physician.43 None of the included studies reported a decision to use either FOLFIRINOX or GEM+, which reflects the current, real-world dilemma. Due to a more favorable side-effect profile, Gemcitabine-based regimens may be chosen for patients with poor performance status, whereas patients with a higher performance status receive FOLFIRINOX. The number of chemotherapy cycles varied across studies; however, a previous meta-analysis demonstrated this may not have a major impact.43 Further the data on the rate of complications of systemic therapy, i.e., how many patients interrupt the therapy or need a modification of therapy were not available. Another bias is the role of radiotherapy. Not all included studies performed radiotherapy in the multimodal management of pancreatic cancer in the neoadjuvant setting. The literature search was conducted 18 months ago. Since publications, some further studies were conducted and not included in this analysis.55–57 It is important to highlight that heterogeneity exists between institutional and international committee definitions of BRCP and LAPC.46 Despite these limitations, our ability to examine patient-level data, examine patients who were and were not resected, and the ability to analyze BRCP and LAPC patients separately offers significant value to this important clinical question. Finally, we were able to offer subanalyses on the variety of combinations of Gemcitabine-based chemotherapy regimens, which further improves the real-world applicability of our findings.

Conclusions

In the setting of BRPC and LAPC, our data suggest that FOLFIRINOX may be preferred for patients with good performance status due to the survival benefit in patients who are ultimately not resected. Combination therapy with gemcitabine can be considered as a reasonable alternative to FOLFIRINOX, particularly in patients who have a less robust performance status or who are expected to ultimately undergo definitive surgical resection. Prospective data are needed to clarify the optimal timing, duration, and type of chemotherapy regimen as well as the appropriate use of radiotherapy in neoadjuvant or definitive treatment for the heterogeneous patient population that comprises BRPC and LAPC.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contributions

DE, BA, and RP are first authors, and KL is the last author of this manuscript. UH performed statistical analysis and edited the manuscript. All other authors contributed as following: data interpretation, writing, patient level data. First authors, last author, and a statistician (UH) verified the underlying data.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich. None.

Disclosures

Sarah Hoffe: Galera Pharmaceuticals, Institutional Principal Investigator for the GRECO-2 randomized international study for which my cancer center receives funding to support the trial, it is a pancreas trial that includes SBRT. D.E., B.A., R.P share first authorship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dilmurodjon Eshmuminov, Botirjon Aminjonov and Russell F. Palm share the first authorship.

References

- 1.Henley SJ, Ward EM, Scott S, Ma J, Anderson RN, Firth AU, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part I: National cancer statistics. Cancer. 2020;126(10):2225–2249. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stathis A, Moore MJ. Advanced pancreatic carcinoma: current treatment and future challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(3):163–172. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74(11):2913–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ducreux M, Cuhna AS, Caramella C, Hollebecque A, Burtin P, Goere D, et al. Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):v56–68. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Al-Hawary M, Asbun H, Bain A, Behrman SW, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Version 2.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(8):1028-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Maggino L, Malleo G, Marchegiani G, Viviani E, Nessi C, Ciprani D, et al. Outcomes of primary chemotherapy for borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(10):932–942. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, Ben Abdelghani M, Wei AC, Raoul JL, et al. FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2395–2406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perri G, Prakash L, Qiao W, Varadhachary GR, Wolff R, Fogelman D, et al. Response and survival associated with first-line FOLFIRINOX vs Gemcitabine and nab-Paclitaxel chemotherapy for localized pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(9):832–839. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philip PA, Lacy J, Portales F, Sobrero A, Pazo-Cid R, Manzano Mozo JL, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPACT): a multicentre, open-label phase 2 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(3):285–294. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellon EA, Hoffe SE, Springett GM, Frakes JM, Strom TJ, Hodul PJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of induction chemotherapy and neoadjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy for borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(7):979–985. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1004367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kunzmann V, Siveke JT, Algul H, Goekkurt E, Siegler G, Martens U, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine followed by FOLFIRINOX induction chemotherapy in locally advanced pancreatic cancer (NEOLAP-AIO-PAK-0113): a multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(2):128–138. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PROSPERO. Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/. Accessed 1 Feb 2021.

- 14.Online statistics. Available at: http://rbiostatistics.com/. Accessed 24 Aug 2021.

- 15.Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available at: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-10. Accessed 26 Dec 2020.

- 16.Byun Y, Han Y, Kang JS, Choi YJ, Kim H, Kwon W, et al. Role of surgical resection in the era of FOLFIRINOX for advanced pancreatic cancer. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2019;26(9):416–425. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itchins M, Arena J, Nahm CB, Rabindran J, Kim S, Gibbs E, et al. Retrospective cohort analysis of neoadjuvant treatment and survival in resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in a high volume referral centre. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(9):1711–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kourie H, Auclin E, Cunha AS, Gaujoux S, Bruzzi M, Sauvanet A, et al. Characteristic and outcomes of patients with pathologic complete response after preoperative treatment in borderline and locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: An AGEO multicentric retrospective cohort. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2019;43(6):663–668. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rangelova E, Wefer A, Persson S, Valente R, Tanaka K, Orsini N, et al. Surgery improves survival after neoadjuvant therapy for borderline and locally advanced pancreatic cancer: A single institution experience. Ann Surg. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Rose JB, Rocha FG, Alseidi A, Biehl T, Moonka R, Ryan JA, et al. Extended neoadjuvant chemotherapy for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer demonstrates promising postoperative outcomes and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(5):1530–1537. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3486-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahora K, Kuehrer I, Eisenhut A, Akan B, Koellblinger C, Goetzinger P, et al. NeoGemOx: Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin as neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced, nonmetastasized pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2011;149(3):311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmocker RK, Wright MJ, Ding D, Beckman MJ, Javed AA, Cameron JL, et al. An aggressive approach to locally confined pancreatic cancer: defining surgical and oncologic outcomes unique to pancreatectomy with celiac axis resection (DP-CAR). Ann Surg Oncol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Shaib WL, Sayegh L, Zhang C, Belalcazar A, Ip A, Alese OB, et al. Induction therapy in localized pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2019;48(7):913–919. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timmermann L, Rosumeck N, Klein F, Pratschke J, Pelzer U, Bahra M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy enhances local postoperative histopathological tumour stage in borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: A matched-pair analysis. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(10):5781–5787. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia BT, Fu B, Wang J, Kim Y, Ahmad SA, Dhar VK, et al. Does radiologic response correlate to pathologic response in patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy for borderline resectable pancreatic malignancy? J Surg Oncol. 2017;115(4):376–383. doi: 10.1002/jso.24538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoo C, Lee SS, Song KB, Jeong JH, Hyung J, Park DH, et al. Neoadjuvant modified FOLFIRINOX followed by postoperative gemcitabine in borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a Phase 2 study for clinical and biomarker analysis. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(3):362–368. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0867-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang H, Jo JH, Lee HS, Chung MJ, Bang S, Park SW, et al. Comparison of efficacy and safety between standard-dose and modified-dose FOLFIRINOX as a first-line treatment of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;10(11):421–430. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i11.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoo C, Shin SH, Kim KP, Jeong JH, Chang HM, Kang JH, et al. Clinical outcomes of conversion surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer: a single-center, retrospective analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Versteijne E, Suker M, Groothuis K, Akkermans-Vogelaar JM, Besselink MG, Bonsing BA, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus immediate surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: Results of the Dutch randomized phase III PREOPANC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(16):1763–1773. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim EJ, Ben-Josef E, Herman JM, Bekaii-Saab T, Dawson LA, Griffith KA, et al. A multi-institutional phase 2 study of neoadjuvant gemcitabine and oxaliplatin with radiation therapy in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(15):2692–2700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koay EJ, Katz MHG, Wang H, Wang X, Prakash L, Javle M, et al. Computed tomography-based biomarker outcomes in a prospective trial of preoperative FOLFIRINOX and chemoradiation for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Takahashi H, Akita H, Ioka T, Wada H, Tomokoni A, Asukai K, et al. Phase I trial evaluating the safety of preoperative gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel with concurrent radiation therapy for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2018;47(9):1135–1141. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esnaola NF, Chaudhary UB, O'Brien P, Garrett-Mayer E, Camp ER, Thomas MB, et al. Phase 2 trial of induction gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and cetuximab followed by selective capecitabine-based chemoradiation in patients with borderline resectable or unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(4):837–844. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi M, Mizuno S, Murata Y, Kishiwada M, Usui M, Sakurai H, et al. Gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery for borderline resectable and locally unresectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: significance of the CA19-9 reduction rate and intratumoral human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 expression. Pancreas. 2014;43(3):350–360. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pouypoudat C, Buscail E, Cossin S, Cassinotto C, Terrebonne E, Blanc JF, et al. FOLFIRINOX-based neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for borderline and locally advanced pancreatic cancer: A pilot study from a tertiary centre. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(7):1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blazer M, Wu C, Goldberg RM, Phillips G, Schmidt C, Muscarella P, et al. Neoadjuvant modified (m) FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced unresectable (LAPC) and borderline resectable (BRPC) adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(4):1153–1159. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4225-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mavros MN, Moris D, Karanicolas PJ, Katz MHG, O'Reilly EM, Pawlik TM. Clinical trials of systemic chemotherapy for resectable pancreatic cancer: A review. JAMA Surg. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Burris HA, 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(6):2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Versteijne E, Vogel JA, Besselink MG, Busch ORC, Wilmink JW, Daams JG, et al. Meta-analysis comparing upfront surgery with neoadjuvant treatment in patients with resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2018;105(8):946–958. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jang JY, Han Y, Lee H, Kim SW, Kwon W, Lee KH, et al. Oncological benefits of neoadjuvant chemoradiation with gemcitabine versus upfront surgery in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: A prospective, randomized, open-label, multicenter phase 2/3 trial. Ann Surg. 2018;268(2):215–222. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Janssen QP, Buettner S, Suker M, Beumer BR, Addeo P, Bachellier P, et al. Neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and patient-level meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(8):782–794. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suker M, Beumer BR, Sadot E, Marthey L, Faris JE, Mellon EA, et al. FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and patient-level meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(6):801–810. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00172-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kunzmann V, Siveke JT, Algül H, Goekkurt E, Siegler G, Martens U, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine followed by FOLFIRINOX induction chemotherapy in locally advanced pancreatic cancer (NEOLAP-AIO-PAK-0113): a multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(2):128–138. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gilbert JW, Wolpin B, Clancy T, Wang J, Mamon H, Shinagare AB, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: conceptual evolution and current approach to image-based classification. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(9):2067–2076. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katz MH, Marsh R, Herman JM, Shi Q, Collison E, Venook AP, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: need for standardization and methods for optimal clinical trial design. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(8):2787–2795. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanchez-Velazquez P, Muller X, Malleo G, Park JS, Hwang HK, Napoli N, et al. Benchmarks in pancreatic surgery: A novel tool for unbiased outcome comparisons. Ann Surg. 2019;270(2):211–218. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hammel P, Huguet F, van Laethem JL, Goldstein D, Glimelius B, Artru P, et al. Effect of chemoradiotherapy vs chemotherapy on survival in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer controlled after 4 months of Gemcitabine with or without Erlotinib: The LAP07 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1844–1853. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teriaca MA, Loi M, Suker M, Eskens F, van Eijck CHJ, Nuyttens JJ. A phase II study of stereotactic radiotherapy after FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC-1 trial): Long-term outcome. Radiother Oncol. 2020;155:232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reyngold M, O'Reilly EM, Varghese AM, Fiasconaro M, Zinovoy M, Romesser PB, et al. Association of ablative radiation therapy with survival among patients with inoperable pancreatic cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(5):735–738. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chuong MD, Bryant J, Mittauer KE, Hall M, Kotecha R, Alvarez D, et al. Ablative 5-fraction stereotactic magnetic resonance-guided radiation therapy with on-table adaptive replanning and elective nodal irradiation for inoperable pancreas cancer. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2021;11(2):134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katz MHG, Ou FS, Herman JM, Ahmad SA, Wolpin B, Marsh R, et al. Alliance for clinical trials in oncology (ALLIANCE) trial A021501: preoperative extended chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy plus hypofractionated radiation therapy for borderline resectable adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Katz MHG, Shi Q, Meyers JP, Herman JM, Choung M, Wolpin BM, et al. Alliance A021501: Preoperative mFOLFIRINOX or mFOLFIRINOX plus hypofractionated radiation therapy (RT) for borderline resectable (BR) adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. 2021;39(3_suppl):377-.

- 55.Katz MHG, Shi Q, Meyers J, Herman JM, Chuong M, Wolpin BM, et al. Efficacy of preoperative mFOLFIRINOX vs mFOLFIRINOX plus hypofractionated radiotherapy for borderline resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: The A021501 phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(9):1263–1270. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghaneh P, Palmer D, Cicconi S, Jackson R, Halloran CM, Rawcliffe C, et al. Immediate surgery compared with short-course neoadjuvant gemcitabine plus capecitabine, FOLFIRINOX, or chemoradiotherapy in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (ESPAC5): a four-arm, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00348-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Janssen QP, van Dam JL, Prakash LR, Doppenberg D, Crane CH, van Eijck CHJ, et al. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy after (m)FOLFIRINOX for borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A TAPS consortium study. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(7):783-91 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.