Abstract

Glucose metabolism in fish remains a controversial area of research as many fish species are traditionally considered glucose-intolerant. Although energy homeostasis remodeling has been observed in fish with inhibited fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO), the effects and mechanism of the remodeling caused by blocked glucose uptake remain poorly understood. In this study, we blocked glucose uptake by knocking out glut2 in zebrafish. Intriguingly, the complete lethality, found in Glut2-null mice, was not observed in glut2−/− zebrafish. Approxiamately 30% of glut2−/− fish survived to adulthood and could reproduce. The maternal zygotic mutant glut2 (MZglut2) fish exhibited growth retardation, decreased blood and tissue glucose levels, and low locomotion activity. The decreased pancreatic β-cell numbers and insulin expression, as well as liver insulin receptor a (insra), fatty acid synthesis (chrebp, srebf1, fasn, fads2, and scd), triglyceride synthesis (dgat1a), and muscle mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (mtor) of MZglut2 zebrafish, suggest impaired insulin-dependent anabolic metabolism. Upregulated expression of lipolysis (atgl and lpl) and FAO genes (cpt1aa and cpt1ab) in the liver and proteolysis genes (bckdk, glud1b, and murf1a) in muscle were observed in the MZglut2 zebrafish, as well as elevated levels of P-AMPK proteins in both the liver and muscle, indicating enhanced catabolic metabolism associated with AMPK signaling. In addition, decreased amino acids and elevated carnitines of the MZglut2 zebrafish supported the decreased protein and lipid content of the whole fish. In summary, we found that blocked glucose uptake impaired insulin signaling-mediated anabolism via β-cell loss, while AMPK signaling-mediated catabolism was enhanced. These findings reveal the mechanism of energy homeostasis remodeling caused by blocked glucose uptake, which may be a potential strategy for adapting to low glucose levels.

Keywords: GLUT2, homeostasis, insulin, lipolysis, proteolysis, zebrafish

Introduction

Fish are known to have a poor ability to use dietary carbohydrates. Overloading dietary carbohydrates may cause metabolic disorders in fish, such as fatty liver disease, stress response, and reduced growth performance (1, 2). Although the high carbohydrate diet challenge has been undertaken in several studies (3–6), the metabolic consequences of blocking glucose uptake under normal conditions are unknown. Insulin is well known to promote anabolic metabolism by stimulating lipid and protein synthesis (7), whereas adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling promotes catabolic metabolism by switching on catabolic pathways but turning-off energy-consuming processes (8–11). Recently, studies in fish demonstrated that inhibited fatty acid β-oxidation by cpt1b and pparab deletion, or mildronate administration caused the remodeling of energy homeostasis by increasing glucose utilization and inhibiting amino acid breakdown through activating AMPK pathways (10, 12). However, the energy homeostasis remodeling of fish after blocking glucose uptake and the regulation of insulin and/or AMPK signaling remains unknown.

Glucose enters cells through facilitated diffusion regulated by a large family of glucose transporter proteins (GLUTs) (13), which contain 12 membrane-spanning helices with amino and carboxyl termini exposed to the cytosol. Glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2, also known as SLC2A2), is encoded by solute carrier family 2 member 2, which is expressed in various tissues, including the liver, intestine, kidney, pancreatic β-cell, and central nervous system (14–16). GLUT2 in mammals has been known to transport glucose in different tissues, such as the intestine, liver, and kidney (17). Inactivating GLUT2 mutations resulted in a condition associated with hepatomegaly, growth retardation, and Fanconi syndrome, which is characterized by glucose malabsorption, renal glucosuria, and transient neonatal diabetes (17, 18). Loss of GLUT2 in mice usually leads to death within 2–3 weeks of birth (19) and exhibits hyperglycemia and hypoinsulinemia, and elevated levels of glucagon and free fatty acids in plasma (20). Interestingly, transgenic re-expression of GLUT1 or GLUT2 in pancreatic β-cells rescues GLUT2-null mice from early death and restores glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (21, 22), which indicated that the function of GLUT2 in pancreatic β-cells plays an important role for survival. To date, the effect of Glut2 on the normal maintenance of pancreatic β-cells and the survival of fish has not been reported.

The deletion of GLUT2 in the kidney improved glucose tolerance, reversed hyperglycemia, and normalized body weight in mice with diabetes and obesity (23). However, the deletion in the liver and kidney eliminated these improvements (23). It was revealed that GLUT2 participated in glucose absorption in the intestine, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in β-cells, glucosensing capabilities, and food intake in the brain (13, 17). The differential physiological role of GLUT2 in systemic glucose homeostasis is tissue-specific, and this may be due to the differentiated systemic regulatory network of glucose in different tissues. On the other hand, given the crucial role of skeletal muscle in glucose metabolism, more attention should be paid to adaptive metabolic responses to glucose uptake attenuation. Studies in mice have shown that skeletal muscles are essential for regulating glucose metabolism as they are responsible for 70% of postprandial glucose uptake (24). The metabolic consequences of glucose uptake attenuation-mediated energy insufficiency would contribute to the elucidation of the systemic regulatory network of nutrient metabolism in non-mammalian vertebrates and provide an excellent model for dissecting the intrinsic association and regulatory network of insulin and AMPK signaling.

Zebrafish have been developed as an appropriate model for nutrient metabolism research (12, 25, 26). In this study, we constructed the glut2-deletion zebrafish model to block glucose uptake in fish and found that zebrafish with glut2-deletion did not completely die like mice, and surviving glut2-deletion zebrafish could reproduce. Therefore, these maternal zygotic mutant glut2 (MZglut2) zebrafish may be ideal models for studying overall nutrient metabolism after glucose loading. In addition, we found that glut2-deletion caused a decrease in the number of β-cells, which was related to the decrease of insulin-associated anabolic metabolism in surviving zebrafish. However, MZglut2 zebrafish may adapt to blocked glucose uptake by remodeling the metabolic pattern in vivo by reducing insulin-mediated anabolism and enhancing AMPK-mediated catabolism. These results suggest that glut2 is important in regulating glucose uptake and is a key signal for maintaining energy expenditure in fish. Thus, we reveal the mechanism of energy homeostasis remodeling induced by blocked glucose uptake in fish.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

Experimental zebrafish were obtained from the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Wuhan, Hubei, China). Animal experiments and treatments were performed according to the Guide for Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IHB, CAS, Protocol No. 2016–018).

Zebrafish maintenance

All embryos were obtained by natural fertilization and were incubated in hatching water (4 L water + 6 mL sea salt + 200 μL methylene blue saturated solution) at 28.5°C with no more than 50 embryos per dish. Developmental stages were determined by days post-fertilization (dpf) or months post-fertilization (mpf) (27). Dead embryos were promptly removed at 0–3 dpf, and membranes were removed at 3 dpf. At 5 dpf, all larvae were transferred to standing water aquariums (50 larvae/aquarium/L) and fed with paramecia. From 9 to 15 dpf, they were fed with paramecia and a small amount of newly hatched brine shrimp (Artemia cysts) (Tianjin Fengnian Aquaculture Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China). From embryos to 15 dpf larvae, half of the rearing water was replaces daily. At 15 dpf, all larvae (60 fish/aquarium/10L) were transferred to a circulated water system and fed with newly hatched brine shrimp twice a day at 28.5°C under a 14-h light and 10-h dark photocycle.

The analysis of glut2 transcriptional expression

Six wild-type zebrafish (3 mpf) were exposed to ice bath anesthesia and their tissues were immediately separated into RNAlater™ solution (AM7020, Invitrogen, USA). The glut2 mRNA tissue distribution analysis was then performed according to the previously described method (28).

Establishment of the glut2-deletion zebrafish line

According to a previous study, glut2-knockout zebrafish were created using CRISPR/Cas9 technology (29). Briefly, male zebrafish with mosaic mutations (F0) were mated with wild-type zebrafish to create heterozygous F1 offspring; female fish were further purified with another control male to generate an F2 population. F3 fish, with glut2+/+(control), glut2+/−, and glut2−/− genotypes, were obtained from crossing glut2 F2 heterozygotes at 3 mpf. Examination of fish genotypes from the population was carried out as previously described (25). Two effective mutant lines were obtained, and the knockout efficiency was further verified using qPCR analysis, which was performed on 5 dpf F3 population zebrafish (control and glut2−/−) as previously described (30).

Hatching rate and survival

Six pairs of male and female heterozygote F2 zebrafish (6 mpf) from the same parent were selected as parent fish to ensure that the genetic background of the experimental fish was similar. Then, 100 eggs of each pair were randomly selected and incubated to calculate the hatching rate: hatching rate = 100 × (100 – number of dead embryos – number of unbroken embryos until 3 dpf)/100. The survival rate of zebrafish was analyzed from 6 to 21 dpf. The dead zebrafish were timeously collected in PCR tubes and stored at −80°C. All live fish were killed in an ice bath and genotyped together with the dead fish. Here, 236 fish were successfully identified for survival analysis.

Photographing and growth performance

Juvenile zebrafish at 30 dpf were anesthetized using MS-222 (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), and each fish was immediately photographed and genotyped. The images were imported into ImageJ software for body length measurement, which was standard with a known length bar. Each genotyped zebrafish was then weighed. Here, 105 fish were used for growth performance analysis.

Hatching rate and survival of MZglut2 zebrafish

The homozygous fish (F3) could partially survive and self-cross to produce the maternal zygotic mutant glut2 (MZglut2) zebrafish (F4). To ensure that the genetic background of the next experimental fish was similar to the previous experimental fish, the F4 zebrafish (including the control group) used the same pair of male and female heterozygotes F2 zebrafish offspring as their parent fish (F3). The hatching rate and survival analysis were then performed as described above (200 larvae per genotype were used for survival analysis). Only male fish were analyzed in the following study to avoid ovulation cycle bias on lipid and glucose metabolism (31).

Growth performance of MZglut2 zebrafish

Until their adult stage (3 mpf), fish (21 fish for each genotype) were randomly selected and anesthetized using MS-222, and the body length was measured, and the corresponding weight was weighted.

Glucose measurement

After ice bath anesthesia, the caudal fin was severed with scissors and whole blood collected from the wound was immediately used for blood glucose measurement using a blood glucose meter (Nipro Diagnostics, Inc., Florida, USA). Liver and muscle tissues (two fish for one sample, eight replicates for each genotype) were then immediately harvested and their glucose content was measured according to the instructions of the assay kit (MS2601, Shanghai Cablebridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China).

Glucose uptake assay

Hepatocyte preparation was performed according to the previous study (32). The control and MZglut2 zebrafish primary hepatocyte (12 fish per genotype at 3 mpf) were separated and incubated in DMEM/F12 medium at 28.5°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h. The medium was then discarded, and PBS was added to slowly wash the cells; the PBS was removed for the glucose uptake assay. The glucose uptake assay in hepatocytes was performed according to assay kit instructions (J13114, Promega, USA). Briefly, the cells were treated with 10 mM 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) for 10 min at 28.5°C, and their luminescence intensity was measured according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Dynamic detection of blood glucose

Glucose tolerance tests were performed on the control and MZglut2 fasting (16 h) zebrafish at 3 mpf. Their dynamic blood glucose levels were measured using a glucose meter after ice bath anesthesia using two methods (six fish for each time point). First, fasting zebrafish were immersed in a 3% glucose solution for 3 h, and following hyperglycemic induction, blood glucose concentrations at different time points were detected. Second, zebrafish were fed a high carbohydrate diet (40% dextrin) for 6 days before the experiment was started, and after the diet was consumed for 7 days, blood glucose concentrations were measured at different time points (calculated from the first bite of food). The caudal fin was severed with scissors after ice bath anesthesia, and whole blood collected from the wound was used for blood glucose measurement. The high carbohydrate diet used in this experiment is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

qRT-PCR analysis

The qRT-PCR analysis was performed as per the detailed steps in our previous study (33). Briefly, total mRNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA), and cDNA was synthesized using a cDNA synthesis kit (TransGen Biotech, AE311-03). A real-time quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche, Germany) on a Light-Cycler 480 system (Roche). All mRNA levels were calculated as fold expression relative to the housekeeping gene rpl7. The primers used for qPCR are listed in Table 1. In the present study, since glut2 is thought to be a high Michaelis constant (Km) transporter, intestinal and liver tissue samples were taken at 2 h of high carbohydrate feeding to monitor glucose transporter expression. However, the difference is that we sampled lipid-related gene expression at 6 h after a normal meal, while protein-related gene expression was sampled at 24 h after a normal meal.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

| Gene name | Primer directiona and sequence (5′-3′) | Accession no. | Product sizeb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype examination | |||

| glut2c | F: CAGATGGGATACAGCTTGG | NM_001042721.1 | 181 |

| R: AGATGGCGACGGATAAAGA | |||

| qPCR | |||

| rpl7c | F: CAGAGGTATCAATGGTGTCAGCCC | NM_213644.2 | 119 |

| R: TTCGGAGCATGTTGATGGAGGC | |||

| glut2c | F: CCACCGAAAACATGGAGGAGTT | NM_001042721.1 | 167 |

| R: TGTCATAACACCTGGGCTCTGTG | |||

| glut1c | F: TATTGGACGGTTTGTGGTG | XM_002662528.5 | 118 |

| R: AAGTTGATGAAGTGTGCCC | |||

| glut3c | F: CACTGGAGAGCCGATGGATG | XM_002667123.5 | 135 |

| R: ATGGACTTCCGTCCTCCAAG | |||

| glut5c | F: TGATGGGTGTGAGTGAAGTG | NM_001365652.1 | 297 |

| R: GGAAGAAAGGCAGAAGCAG | |||

| glut8c | F: TGACCAGTGTGCTAACGGAC | NM_212798.1 | 300 |

| R: TAGAAGCACACAGTGCCGAG | |||

| glut9c | F: CTTCGGCTTTTCAGCGATGG | XM_017359073.2 | 157 |

| R: CAACACAAACGGGACACCAC | |||

| glut12c | F: GGGACAATCCTGGACCACTA | NM_200538.1 | 136 |

| R: ACATCCCAACCAGCATTCTC | |||

| sglt1c | F: ATTGGAGCCTCTCTCTTCGC | NM_200681.1 | 177 |

| R: CATAGTCACAACCCCAGCCT | |||

| insra c | F: GCGTGGCAATAATCTGTTCT | NM_001142672.1 | 278 |

| R: CGTTGATAGTGGTGAGGGGG | |||

| insrb c | F: TTTCGCCTACATCTTGTGCC | NM_001123229.1 | 101 |

| R: AGTTCTCCAAAACCCGCA | |||

| chrebp c | F: ACCCCGACATGACCTTCAAC | NM_001328694.1 | 157 |

| R: TGTGGCATCTCTGTGTTGCT | |||

| srebf1c | F: ATGGCGGAAGACAGCAA | NM_001105129.1 | 107 |

| R: AGCGGGTTAAAGGACAGAA | |||

| srebf2c | F: CACACTCTTCTCTCTGCCCG | NM_001089466.1 | 165 |

| R: GATGTCGGTGAGTGAAGGGG | |||

| aclya c | F: GAGCTCCGAGTGAGCAACAA | NM_001002649.2 | 157 |

| R: AAAGCCCTGACGATACCCTTG | |||

| fasn c | F: GGAGCAGGCTGCCTCTGTGC | XM_009306807.3 | 128 |

| R: TTGCGGCCTGTCCCACTCCT | |||

| acc c | F: GCGTGGCCGAACAATGGCAG | XM_021476192.1 | 137 |

| R: GCAGGTCCAGCTTCCCTGCG | |||

| fads2c | F: CAGCATCACGCTAAACCCAAC | NM_131645.2 | 164 |

| R: AGGGGAGGACCAATGAAGAAG | |||

| scd c | F: AGCCACTTTACCTCTGCG | NM_198815.2 | 219 |

| R: AGCTCTAGTTTGCGTCCT | |||

| dgat1ac | F: CCAAAGCTCGAACCCTGTCT | NM_199730.1 | 104 |

| R: GTGTGTGAGGTTTCCCGGAT | |||

| dgat2c | F: ACGCATAACCTGCTTCCC | NM_001030196.1 | 102 |

| R: TCCTGTGGCTTCTGTCCC | |||

| atgl c | F: CCTGCAAGGAGTGAGGTATG | XM_005174256.4 | 192 |

| R: CTGTAGAGGTTGGCGAGTGT | |||

| lpl c | F: GCTCTCACGAGCGCTCTATT | NM_131127.1 | 293 |

| R: CTTCATGGGCTGGTCAGTGT | |||

| pparab c | F: TCAGGATACCACTATGGCGTTCAT | NM_001102567.1 | 100 |

| R: AGCGGCGTTCACACTTATCGTA | |||

| cpt1aac | F: CATCCTTAGGCCTGCTCTTCAAA | NM_001044854.1 | 94 |

| R: ACCATGACACCCCCAACTAACAT | |||

| cpt1ab c | F: GACTTCCAATTACGTCAGCGA | XM_005170707.4 | 189 |

| R: TGTGCTCTGTCCAGTTTTCTCC | |||

| acox3c | F: TGGAAGGACATGATGCGCTTT | NM_213147.1 | 102 |

| R: AGGCTGCCGGGCAAAAA | |||

| mtor c | F: TGGGAGCAGACAGGAATGAAGG | NM_001077211.2 | 97 |

| R: TGCACCTGCTGGAAAAAGAATG | |||

| bcat1c | F: GGGCTCGTACTTCAGCACAGGA | NM_200064.1 | 104 |

| R: TCCCTCCCATCTTGCAGTCTCC | |||

| bcat2 c | F: CCGACCATCGCTGTCCAGAATG | NM_001002676.2 | 100 |

| R: TCATGGTGCCGACCTCAGTGAT | |||

| bckdha c | F: TCCGACGAGAAGCCGCAGTT | NM_001024419.1 | 117 |

| R: GCCCTGTCTGTCCATCACTCTG | |||

| bckdk c | F: TTGATTTTGCTCGACGGCTCT | NM_213060.2 | 95 |

| R: TGGAATGAAGGGAAAGCGGG | |||

| glud1bc | F: GATGTCCTGGATTGCTGACACCT | NM_199545.4 | 96 |

| R: CCACCCTGGCTAATGGGTTTT | |||

| asns c | F: TTCAGAATGCTGACTGACGATGG | NM_201163.3 | 105 |

| R: TGGAAAAGCAGTGATCTTTGCAG | |||

| atf4ac | F: AGATGAGCACACTGAGGTTCCA | NM_213233.1 | 120 |

| R: TCGGAGCAATCGCTAATGTTCT | |||

| eif4ebp3c | F: CCGCTTCCGGACAGTTACA | NM_001007354.2 | 78 |

| R: ATAGATAATCCGAGTTCCGCC | |||

| murf1ac | F: AGCCTGTTGTCATTCTCCCG | NM_001002133.1 | 126 |

| R: CCTCGAAGCGACAAGTAGGG | |||

aF: Forward primer; R: Reverse primer. bbp: base pair. cglut2, solute carrier family 2 member 2; rpl7, ribosomal protein L7; glut1, solute carrier family 2, member 1; glut1, solute carrier family 2, member 1; glut3, solute carrier family 2, member 3; glut5, solute carrier family 2, member 5; glut8, solute carrier family 2, member 8; glut9, solute carrier family 2, member 12; sglt1, solute carrier family 5 member 1; insra, insulin receptor a; insrb, insulin receptor b; chrebp, carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein-like; srebf1, sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1; srebf2, sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 2; aclya, ATP citrate lyase a; fasn, fatty acid synthase; acc, acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha; fads2, fatty acid desaturase 2; scd, stearoyl-CoA desaturase; dgat1a, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1a; dgat2, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2; atgl, adipose triglyceride lipase gene; lpl, lipoprotein lipase; pparab, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha b; cpt1aa, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1Aa; cpt1ab, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1Ab; acox3, acyl-CoA oxidase 3; mtor, mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase; bcat1, branched chain amino-acid transaminase 1; bcat2, branched chain amino-acid transaminase 2; bckdha, branched chain keto acid dehydrogenase E1 subunit alpha; bckdk, branched chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase; glud1b, glutamate dehydrogenase 1b; asns, asparagine synthetase; atf4a, activating transcription factor 4a; eif4ebp3, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 3; murf1a, muscle-specific RING finger 1a.

β-cell monitoring, proliferation, and whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) analyses

Tg (insulin:EGFP) (34) was used to mark β-cells for imaging and/or counting as previously described (35). The β-cells of control and MZglut2 zebrafish were monitored at 5 dpf. Fisetin was considered a GLUT2 inhibitor (36), and a concentration of 120 μm was used to incubate 3–5 dpf Tg (insulin:EGFP) embryos to monitor the β-cells at 5 dpf. Proliferation was analyzed as previously described (35). Briefly, the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 594 Imaging kit (C10339, Invitrogen) was used to identify proliferating β cells. At 4 dpf, 1–2 nL of 0.1 mM 5-ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine (EdU) was injected into the fish heart. After 24 h, the fish were euthanized and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde to detect the signals. WISH was performed as previously described (37). Antisense digoxigenin-labeled insulin cRNA was synthesized and used in this study.

HM350 metabolome analysis

Control and MZglut2 zebrafish livers were sampled (three livers per sample, six samples per genotype) in a 1.5-mL tube, which immediately froze in liquid nitrogen. These samples were then sent to the Beijing Genomics Institution for HM350 metabolome analysis.

Determination of lipids and crude proteins

Lipid and crude protein content was measured according to our previous descriptions (33). Briefly, zebrafish were freeze-dried and then ground using a mortar. Next, the chloroform/methanol (V/V, 2:1) extraction technique was used to measure the lipid content of zebrafish. Crude protein content (N × 6.25) was determined after acid digestion using an auto Kjeldahl system (Kjeltec-8400, FOSS Tecator, Haganas, Sweden).

Nile red staining, triglyceride measurement, and Oil Red O staining analyses

Neutral lipid accumulation was visualized using fluorescent dye staining, Nile red, in live fish as previously described (25, 38). Nile red (N3013; Sigma) was dissolved to a concentration of 0.1 g/mL. The fish were immersed in Nile red at 28.5°C overnight in the dark. Images were taken using an Olympus SZX16 FL stereomicroscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. Liver triglycerides were measured using commercially available kits (A110-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China). Fatty droplet accumulation in the liver was visualized using Oil Red O staining as previously described (25).

Western blotting

A Western blot analysis was performed on the liver and muscle tissues of 12 zebrafish from each genotype (one sample mixed with tissues from four fish). The Western blot analysis protocols were performed using the methods described in our previous study (39). The primary antibodies of P-AMPK (1:1000; #2535S; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and β-ACTIN (1:1000; #4970S; Cell Signaling Technology) were used in this study.

Adenosine triphosphate content analysis

For liver and muscle ATP content analysis, 12 individual fish from each genotype were sampled (two fish tissues for one sample, six replicates for each genotype) and measured according to the instructions of the assay kit (A095-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China). The results were standardized using a protein concentration kit (A045-3, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China).

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

For the muscle histological analysis, six individual fish from each genotype were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24 h, followed by routine paraffin sectioning and H&E staining. The cross-section at the base of the cloaca was selected to quantify the total muscle area. Individual total muscle area was determined using the CaseViewer software.

Locomotion tracking analysis

The locomotion tracking analyses were tracked and analyzed as previously described (40, 41). Briefly, after 6 h postprandial, each zebrafish was kept in a tank, and locomotion tracking was recorded for 5 min; the large speed distance and slow-mild speed distance were calculated in each tank for evaluation using the ZebraBox system (ViewPoint Life Sciences, Montreal, QC, Canada).

Measurement of oxygen consumption

Oxygen consumption was measured and analyzed as previously described (40, 41). Briefly, four control or MZglut2 male fish were placed in an 1,150-mL conical flask and sealed for 6 h. Dissolved oxygen before and after sealing was measured using a dissolved oxygen respirator (41). Oxygen consumption was calculated as oxygen consumption per unit body weight. The oxygen consumption of 6 h postprandial (hpp) was calculated from 6 h postprandial fish fed with regular food. Basic oxygen consumption was calculated from the fish after starvation and lasted for 2 days. Four groups of each genotype were set as replicates.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). All results are presented as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

glut2−/− zebrafish from the F3 population showed a 30% survival rate and stunted growth

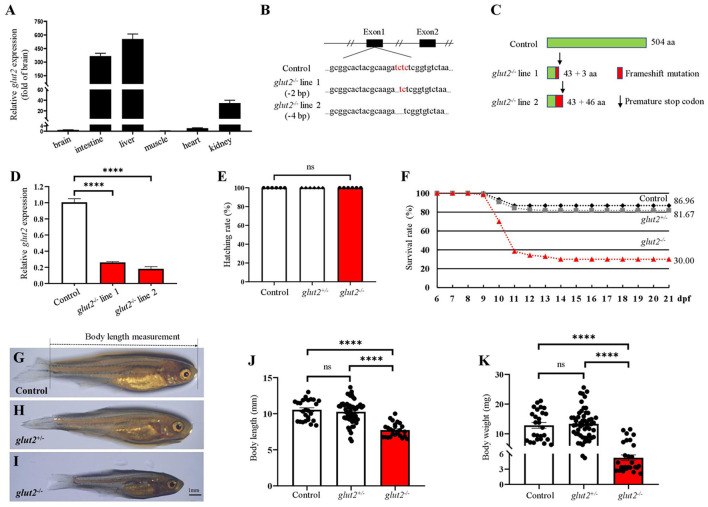

We first examined glut2 transcriptional levels in different zebrafish tissues. The abundant transcriptional expression of glut2 was observed in the liver, intestine, and kidney, suggesting its physiological role associated with glucose uptake in target organs where glut2 is highly expressed (Figure 1A). The putative mRNA of glut2 is 1515 base pairs in length and encodes 504 amino acids. Using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, glut2 knockout in zebrafish with target site mutation was established by microinjection of recombinant Cas9 protein and gRNA from glut2 target sites. The two knockout lines with 2 and 4 base pair deletions were obtained (Figure 1B). PCR products with genomic DNA and cDNA were used as templates for mutation validation. Premature stopping occurs in glut2−/− fish from both knockout lines, which both retain 43 correct amino acids (Figure 1C). Transcriptional expression of glut2 in the 5 dpf control and glut2−/− fish in both line one and line two F3 populations was examined. The downregulated transcriptional expression of glut2 in glut2−/− fish compared to control fish indicates knockout efficacy (P < 0.05) (Figure 1D); this is usually considered due to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. In the F3 population of line two, comparable hatching rates of glut2+/+, glut2+/−, and glut2−/− were observed from 0 to 3 dpf (P > 0.05) (Figure 1E). Subsequently, the F3 population survival rate was statistically analyzed, and a significant decrease was observed in glut2−/− fish, as they died sharply from 9 to 14 dpf (Figure 1F). Intriguingly, approximately 30% of glut2−/− fish survived to adulthood and could reproduce. Compared to glut2+/+ and glut2+/− zebrafish at 30 dpf, the surviving glut2−/− fish exhibited apparent growth retardation, shortened body length, and decreased body weight observed (P < 0.05) (Figures 1G–K).

Figure 1.

The knockout of glut2 in zebrafish. (A) Transcriptional expression analysis of glut2 in different tissues (n = 6). (B) Sequence comparison of glut2 alleles in the control and two glut2 knockout zebrafish lines. (C) Schematic representation of glut2 full-length putative peptide from the control and two glut2 knockout fish lines. aa, amino acids. (D) The transcriptional expression of glut2 in 5 dpf control and glut2−/− fish in the F3 population of both lines 1 and 2 (n = 3). (E) The hatching rate analysis of the control (glut2+/+), glut2+/−, and glut2−/− fish from 0–3 dpf in the F3 population of line 2 (n = 6). (F) Analysis of the control, glut2+/−, and glut2−/− survival rates from 6 to 21 dpf in line 2 F3 population (236 fish were genotyped for analysis). (G–I) Representative images of the overall morphology of the control, glut2+/−, and glut2−/− fish at 30 dpf. (J, K) Body weight and body length of the control (n = 26), glut2+/− (n = 53), and glut2−/− (n = 26) fish at 30 dpf. A two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to detect significance. ****P < 0.0001. ns, no significance.

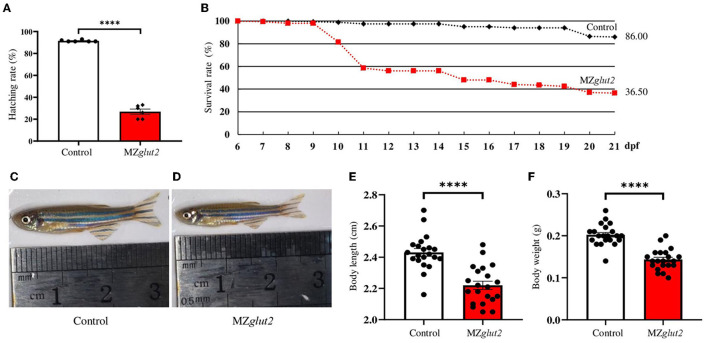

Subsequently, the hatching rate and growth performance of control (offspring from natural mating of glut2+/+ males and females) and MZglut2 fish were compared and analyzed. Hatching rates of MZglut2 fish decreased significantly compared to control fish (P < 0.05) (Figure 2A). This result suggested that maternal glut2 is essential and critical for hatching. Similarly, more than 60% lethality occurred in MZglut2 fish up to 21 dpf, as well as arrested growth performance at 3 mpf (e.g., decreased body length and weight (P < 0.05) (Figures 2B–F).

Figure 2.

glut2-deletion results in growth retardation in MZglut2 fish. (A) The hatching rate analysis of the control and MZglut2 fish from 0 to 3 dpf (n = 6). (B) Survival rate analysis of the control and MZglut2 fish from 6–21 dpf (200 fish of each genotype were used for analysis). (C, D) Representative images of the overall morphology of the control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf. (E, F) Body weight and body length of the control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf (n = 21). A two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to detect significance. ****P < 0.0001.

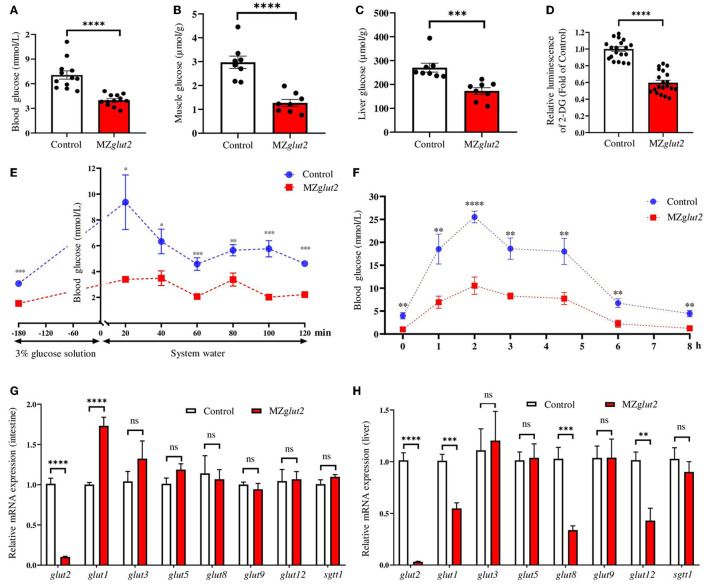

Glucose uptake was effectively inactivated in MZglut2 fish

Adult control and MZglut2 (3 mpf) zebrafish were used for the following analyses. Compared to control fish, MZglut2 fish at 2 hpp showed decreased glucose levels in the blood, muscle, and liver (P < 0.05) (Figures 3A–C). The in vitro 2-DG uptake assay demonstrated that the 2-DG uptake decreased in the liver of MZglut2 fish compared to the control fish (P < 0.05) (Figure 3D). After administration of a 3% glucose solution for 3 h, significant increases in blood glucose were observed in the control and MZglut2 fish at 20 min after 3% glucose deprivation; however, MZglut2 fish blood glucose decreased before and after 3% glucose administration at all time points examined (P < 0.05) (Figure 3E). Dynamic blood glucose was also assessed after a high carbohydrate diet. Blood glucose peaked at 2 hpp in both control and MZglut2 fish, but the MZglut2 fish blood glucose decreased at all time points (P < 0.05) (Figure 3F). The compensatory effect of glucose transporters in the intestine of the MZglut2 fish at 2 hpp of the high carbohydrate diet was detected, as intestinal glut1 transcriptional expressions were upregulated compared to control fish at 2 hpp (P < 0.05) (Figure 3G). Compensatory expression of other glucose transporters in the liver was not observed, as expressions of glut2, glut1, glut8, and glut12 were downregulated in MZglut2 fish at 2 hpp of the high carbohydrate diet (P < 0.05) (Figure 3H). These results suggest that glucose uptake was effectively inactivated in MZglut2 fish.

Figure 3.

glut2-deletion results in impaired glucose uptake in MZglut2 fish. (A) Glucose content in the blood of the control and MZglut2 fish (n = 12). (B) Glucose content in the muscle of the control and MZglut2 fish (n = 8). (C) Glucose content in the liver of the control and MZglut2 fish (n = 8). (D) The hepatic glucose uptake levels (2-DG) of the control and MZglut2 fish (n = 20). (E) Blood glucose levels of the control and MZglut2 fish after the glucose tolerance test for 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 min (n = 6). (F) Blood glucose levels of the control and MZglut2 fish after being fed a high carbohydrate diet for 0, 1, 2, 3, 4.5, 6, and 8 h (n = 6). (G) Transcriptional expression of glut2, glut1, glut3, glut5, glut8, glut9, glut12, and sglt1 in the intestine of the control and MZglut2 fish after fed high carbohydrate diet at 2 h (n = 6). (H) Transcriptional expression of glut2, glut1, glut3, glut5, glut8, glut9, glut12, and sglt1 in the liver of the control and MZglut2 fish after fed high carbohydrate diet at 2 h (n = 6). A two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to detect significance. ****P < 0.0001. ***P < 0.001. **P < 0.01. *P < 0.05. ns, no significance.

glut2-deletion results in impaired insulin-mediated anabolic metabolism in MZglut2 fish

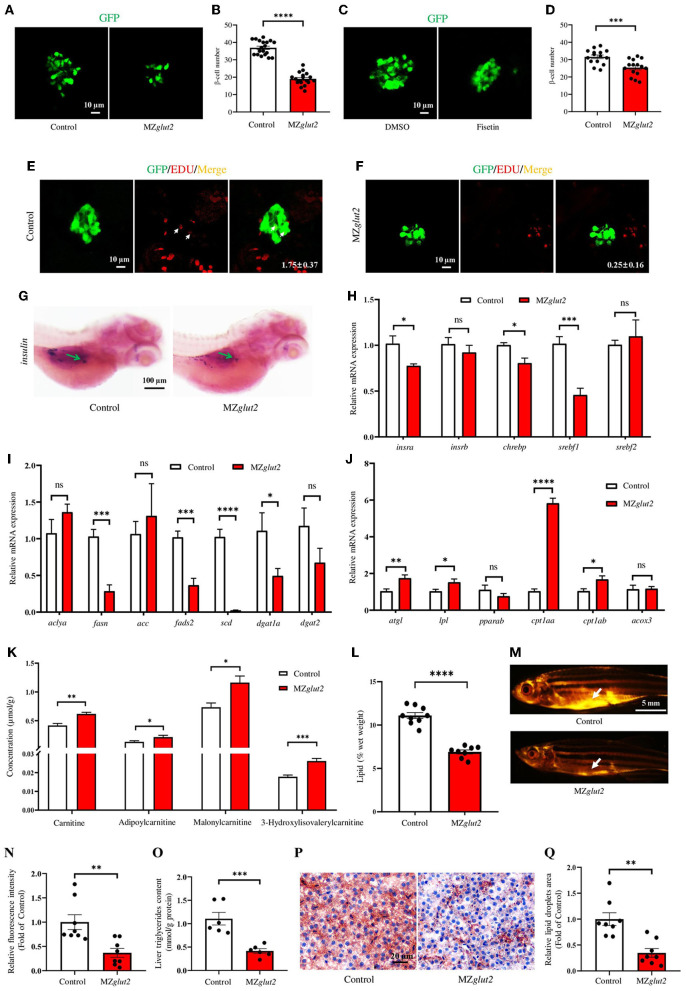

To visualize and analyze the number of β-cells and insulin content in glut2-deletion fish, the transgenic line Tg (insulin:EGFP) was bred with the glut2−/− fish. This enables us to obtain the Tg (insulin:EGFP);glut2+/− fish, which were inbred to generate Tg (insulin:EGFP);glut2−/− fish. The Tg (insulin:EGFP);MZglut2 fish from the natural mating of Tg (insulin:EGFP);glut2−/− males and females were used for the β-cells visualization and analysis. Compared with the control fish at 5 dpf, the number of β-cells significantly decreased in MZglut2 fish (P < 0.05) (Figures 4A, B). Fisetin, which has a hypoglycemic effect (42), was administered to wild-type embryos. In wild-type fish at 5 dpf, the Fisetin-treated fish also displayed decreased number of β-cells (P < 0.05) (Figures 4C, D), mimicking a reduced β-cells number of MZglut2 fish. The EdU staining in control fish and MZglut2 fish at 5 dpf was carried out for 24 h, and the statistical analysis of EdU stained β-cells in MZglut2 larvae was decreased (P < 0.05) (Figures 4E, F). These observations were also supported by the WISH results, from which, the decreased insulin signal in MZglut2 fish at 5 dpf was detected (Figure 4G).

Figure 4.

glut2-deletion results in impaired insulin-mediated anabolic metabolism in MZglut2 fish. (A) Representative images of β-cells in the control and MZglut2 larvae at 5 dpf. (B) The statistical analysis of β-cells in the control (n = 19) and MZglut2 (n = 18) larvae at 5 dpf. (C) Representative images of β-cells in DMSO- and Fisetin-treated larvae at 5 dpf. (D) The statistical analysis of β-cells in DMSO- and Fisetin-treated larvae at 5 dpf (n = 16). (E) Representative images of EdU stained β-cells in the control fish at 5 dpf. Red signal-positive β-cells are indicated by arrows (n = 8). (F) Representative images of EdU staining β-cells in MZglut2 larvae at 5 dpf (n = 8). (G) WISH using the insulin probe to the control and MZglut2 larvae at 5 dpf, with the green arrow representing the signal area. (H) The transcriptional expression levels of insra, insrb, chrebp, srebf1, and srebf2 in the liver of the control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf (n = 6). (I) The transcriptional expression levels of aclya, fasn, acc, fads2, scd, dgat1a, and dgat2 in the liver of the control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf (n = 6). (J) The transcriptional expression levels of atgl, lpl, pparab, cpt1aa, cpt1ab, and acox3 in the liver of the control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf (n = 6). (K) The quantification of carnitine metabolites based on the observations of metabolomics in the liver of control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf (n = 6). (L) The measurement of the lipid content of the control (n = 9) and MZglut2 (n = 8) fish at 3 mpf. (M) Nile Red staining of the control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf. White arrows: visceral adipose tissue. (N) The bar chart represents the relative fluorescence intensity of the control and MZglut2 fish after Nile Red staining (n = 8). (O) Liver triglyceride content at 3 mpf (n = 6). (P) Oil Red O staining of liver sections for distribution of lipid droplets in the control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf. (Q) The bar chart represents the relative lipid droplet areas of control and MZglut2 fish after Oil Red O staining (n = 8). A two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to detect significance. ****P < 0.0001.***P < 0.001. **P < 0.01. *P < 0.05. ns, no significance.

A downregulated insulin receptor gene (insra) was found in the liver of MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf (P < 0.05) (Figure 4H). Meanwhile, fatty acid synthesis (chrebp, srebf1, fasn, fads2, and scd) and triglyceride synthesis (dgat1a) were also downregulated (P < 0.05), but upregulated lipolysis genes (atgl and lpl) and fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) (cpt1aa and cpt1ab) were observed in MZglut2 fish liver at 3 mpf (P < 0.05) (Figures 4H–J). We performed a metabolomic analysis of the liver to obtain an overview of their energy metabolism due to impaired glucose uptake. Carnitines are effective factors to lower lipid content, as they function as key transporters of fatty acids to mitochondria for FAO (43). For metabolite measurements, increased carnitine, adipoylcarnitine, malonylcarnitine, and 3-hydroxylisovalerylcarnitine metabolites were observed in the liver of MZglut2 fish (P < 0.05) (Figure 4K). We observed a significant decrease in lipid content in MZglut2 fish, as evidenced by lipid measurements (P < 0.05) (Figure 4L) and observations of neutral lipids with Nile red staining (P < 0.05) (Figures 4M, N). The biochemical measurement to examine the quantity of liver triglyceride was performed. The MZglut2 fish liver triglyceride content significantly decreased compared with the control fish (Figure 4O). Pathological features of the control and MZglut2 fish liver were examined with histological analysis and Oil Red O staining, from which, the significantly decreased fatty droplet accumulation was observed in MZglut2 fish liver at 3 mpf (P < 0.05) (Figures 4P, Q). These results suggest that glut2-deletion impaired insulin-mediated anabolic metabolism in MZglut2 fish.

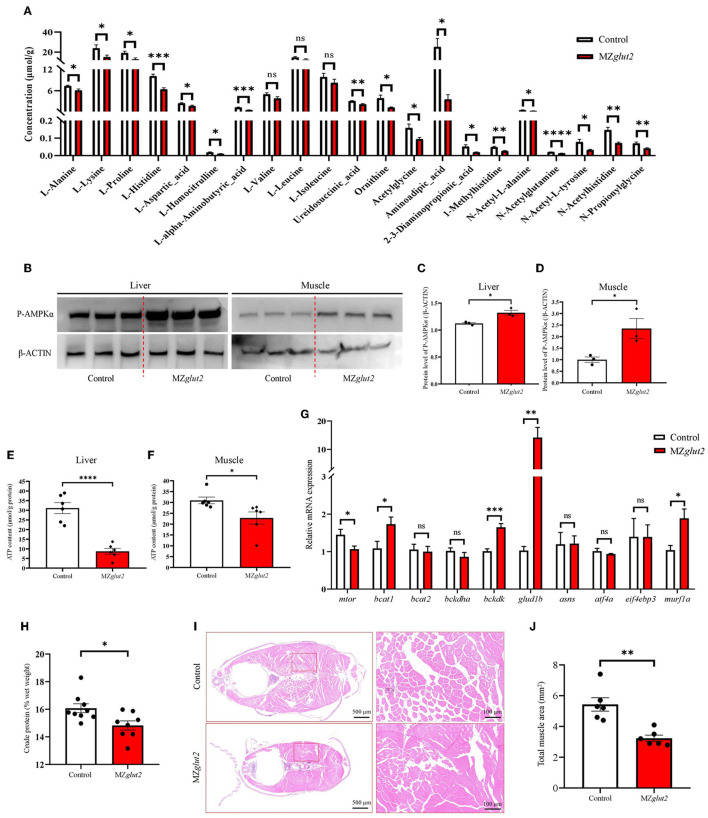

Glucose uptake attenuation enhanced AMPK-mediated catabolic metabolism in MZglut2 fish

Through metabolomics analysis, we found reduced amino acids, such as L-alanine, L-lysine, and L-proline, in the liver of MZglut2 fish (P < 0.05) (Figure 5A). AMPK is known as an energy sensor for activating lipid and protein catabolic metabolism when glucose is deficient. P-AMPK protein levels in the liver and muscle were significantly increased in MZglut2 fish at 24 hpp compared to control fish (P < 0.05) (Figures 5B–D), suggesting a low energy status of MZglut2 fish. Significantly reduced ATP levels were found in the liver and muscle of MZglut2 fish (P < 0.05) (Figures 5E, F). These results provided direct evidence that when glucose uptake was inactivated, insufficient energy supply from glucose activated catabolic metabolism. The bckdk, glud1b, and murf1a genes are known to activate amino acid catabolism and promote ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation (44, 45). All these genes were upregulated in MZglut2 fish muscle (P < 0.05), suggesting an increase in protein and amino acid degradation (Figure 5G). The downregulated expression of mtor in MZglut2 fish muscle not only reflects its attenuated protein synthesis but also agrees with the rise in proteolytic genes. These observations correlated with the decreased crude protein content (P < 0.05) (Figure 5H) and muscle mass (P < 0.05) (Figures 5I, J), which ultimately accounted for growth retardation.

Figure 5.

glut2-deletion results in enhanced AMPK-mediated catabolic metabolism in MZglut2 fish. (A) The quantification of amino acid metabolites is based on the observations of metabolomics in the liver of the control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf (n = 6). (B–D) The level of P-AMPK and β-ACTIN proteins in the liver and muscle of the control and MZglut2 fish (n = 3). (E) The ATP content in the liver of control and MZglut2 fish (n = 6). (F) The ATP content in the muscle of the control and MZglut2 fish (n = 6). (G) The transcriptional expression levels of mtor, bcat1, bcat2, bckdha, bckdk, glud1b, asns, atf4a, eif4ebp3, and murf1a in muscle of control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf (n = 6). (H) The measurement of the crude protein content of the control (n = 9) and MZglut2 (n = 8) fish at 3 mpf. (I) Representative images of H&E staining of the control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf. (J) The bar chart represents the total area of muscle mass in the body cross-section (n = 6). A two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to detect significance. ****P < 0.0001.***P < 0.001. **P < 0.01. *P < 0.05. ns, no significance.

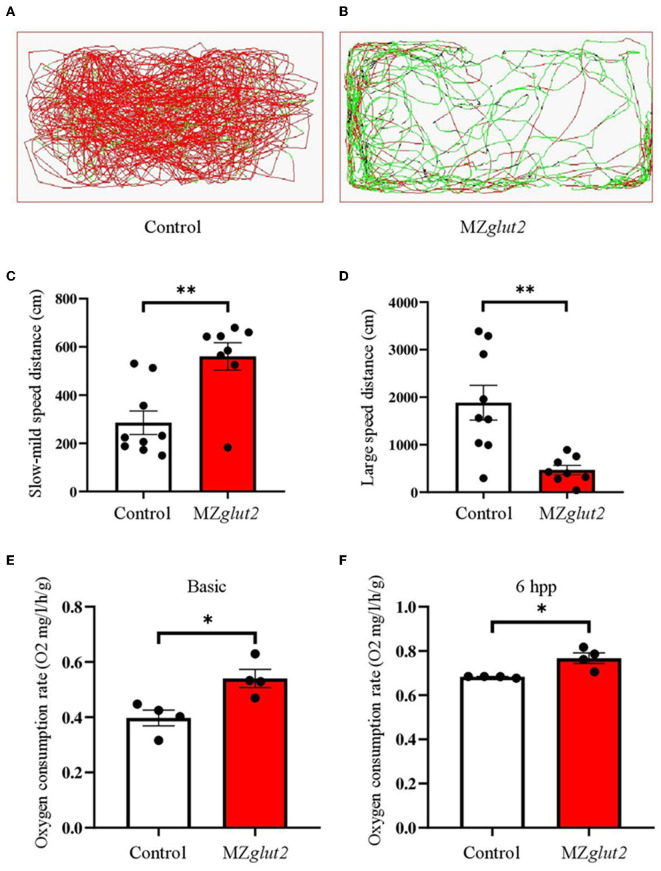

glut2-deletion resulted in slower movement activity but increased oxygen consumption in MZglut2 fish

The swimming activity of the control and MZglut2 fish was recorded for 5 min at 6 hpp. The distance traveled by MZglut2 fish was significantly reduced compared to the control fish (Figures 6A, B). Statistical analysis revealed that the slow-mild movement of MZglut2 fish was upregulated, while the large movement of MZglut2 fish was significantly downregulated (P < 0.05) (Figures 6C, D). To assess energy expenditure, we tested oxygen consumption in control and MZglut2 fish. Both basic and 6 hpp oxygen consumption was significantly increased in MZglut2 fish (P < 0.05) (Figures 6E, F).

Figure 6.

glut2-deletion resulted in slower movement activity but increased oxygen consumption in MZglut2 fish. (A, B) Pathway monitoring of the control and MZglut2 fish continued for 5 min at 3 mpf. (C, D) The distance covered with slow-mild speed or large speed of the control fish (n = 9) and MZglut2 (n = 8). Slow-mild speed (0–2 cm/s) and large speed (> 2 cm/s) of the control and MZglut2 fish. (E, F) The oxygen consumption rate of basic level and 6 hpp in the control and MZglut2 fish at 3 mpf (n = 4). A two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to detect significance. **P < 0.01. *P < 0.05.

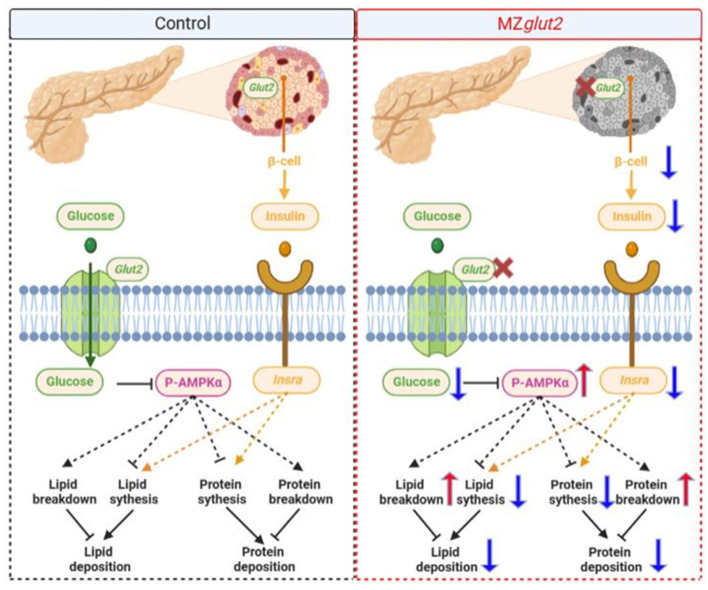

Together, we found that glut2-deletion caused a decrease in the number of β-cells, which was related to the decrease of insulin-associated anabolic metabolism in surviving zebrafish. However, surviving zebrafish may adapt to blocked glucose uptake by remodeling the metabolic pattern in vivo by reducing insulin-mediated anabolism and enhancing AMPK-mediated catabolism (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

A hypothetical diagram showing how glut2-deletion induces remodeling of nutrient metabolism in zebrafish (the blue arrow means downregulation and the red arrow means upregulation).

Discussion

Fish are known to have a poor ability to use dietary carbohydrates. Several metabolic disorders in fish were characterized to be caused by overloaded carbohydrates, as revealed by the high carbohydrate diet challenge undertaken in several studies (1–6). Regardless, the metabolic consequences of blocking glucose uptake under normal conditions are poorly investigated; therefore, the energy homeostasis remodeling of fish after blocking glucose uptake and the regulation of insulin and/or AMPK signaling are still unknown. The dynamic balance among glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids is an important prerequisite for maintaining cellular energy homeostasis (46). Glucose, which is absorbed through various GLUTs in different tissues, is the main source of metabolic energy for most cells (47). GLUT2 controls glucose uptake and glucose sensing, which is mainly expressed in the intestine, liver, and pancreatic β-cells (17). However, energy homeostasis remodeling after glucose uptake and glut2 function in fish is still unknown. In the present study, the effects of energy homeostasis remodeling induced by blocking glucose uptake through glut2-deletion in zebrafish were characterized. We found abundant glut2 expression in the liver and intestine of wild-type zebrafish, and glut2-deletion successfully blocked glucose uptake in zebrafish, which was validated as a useful tool for investigations to help discover the functions of glucose in fish.

In the present study, growth retardation was observed after glucose blocking by knocking out glut2, which was consistent with mutations in Glut2 in mammals (17, 48). The growth of vertebrates is regulated by insulin signaling because insulin is known as the strongest anabolic hormone, which promotes the body's synthesis of proteins and lipids (25, 49). Insulin is secreted by pancreatic β- cells (50), and GLUT2 is thought to be one of the key factors in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (17). Here, we found that glut2-deletion in zebrafish resulted in a decrease in β-cell number, which was caused by reduced proliferation. Similarly, the β-cell reduction was observed in Glut2 knockout mice (20), which indicated a conserved glut2 function for maintaining normal β-cell numbers between mice and zebrafish. Secreted insulin binds to insulin receptors to control downstream signal activation (30). In zebrafish, two insulin receptors play distinct roles in mediating glucose metabolism through the insulin signaling pathway (25). Based on our previous observations, insra is more likely to promote lipid synthesis, while insrb is more likely to promote lipid utilization and protein synthesis (25). In the present study, decreased insulin and insra expression were found in glut2-deletion zebrafish, indicating that the declined lipid synthesis may be mediated by impaired Insulin/Insra signaling, which is also supported by the downregulated lipid synthesis gene expression (chrebp, srebf1, fasn, etc.). Compared with the decrease in lipid content (P < 0.0001) in MZglut2 fish, decreased protein content (P < 0.05) and downregulated mtor (protein synthesis-related gene) were observed. Though insrb was not altered in MZglut2 fish, attenuated Insulin/Insrb signaling cannot be disregarded, which may be caused by the diminished insulin expression in β-cells. In summary, we concluded that glut2-deletion may cause impaired insulin signaling associated with attenuated anabolic metabolism in zebrafish.

As a prominent intracellular energy sensor, AMPK is directly activated by glucose deprivation (51). In this study, increased P-AMPK protein levels in the liver and muscle of MZglut2 fish indicated a poor energy status due to blocked glucose uptake. This was also directly reflected by glucose levels in the liver and muscle. In mice, liver-specific Glut2 knockout inhibited liver glucose uptake (52), which is consistent with our results in the MZglut2 fish liver. However, energy homeostasis remodeling after glucose deprivation was not explored. The functions of AMPK in regulating metabolism are divided into two categories: inhibition of anabolism to reduce ATP consumption and stimulation of catabolism to increase ATP production (51). When cells have poor nutrition, catabolic pathways are activated, but energy-consuming biosynthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol is switched off (53, 54). In our study, switching on the catabolic pathways of lipolysis (atgl and lpl) and FAO (cpt1aa and cpt1ab), and switching off biosynthesis of fatty acids (chrebp, srebf1, fasn, fads2, and scd) and triglycerides (dgat1a) were observed in MZglut2 fish. These results indicated that AMPK-mediated inhibition of anabolism and stimulation of catabolism occurred in MZglut2 fish. AMPK activation directly promotes lipolysis and FAO, while directly inhibiting transcription factors such as carbohydrate-responsive element binding protein (ChREBP) and sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP), and other factors mediated lipid synthesis (51). Previously, Li et al. demonstrated that mitochondrial FAO inhibition resulted in energy homeostasis remodeling, as evidenced by the promotion of glucose utilization in fish (10, 12). However, repressed insulin signaling increased lipolysis and FAO also indicated energy homeostasis remodeling from glucose to lipid in MZglut2 fish. Lipids conserve protein for development more effectively than any other nutrient in fish (55). Thus, appropriate amounts of lipids can reduce protein breakdown in fish, replenishing the body's energy. However, we observed significant reductions in both lipid and protein contents after blocking glucose intake, indicating that lipids are no longer sufficient to maintain a normal energy supply. These findings could be supported by the enhanced amino acid breakdown (bckdk, glud1b, and murf1a) in muscle. Furthermore, protein degradation caused by blocking glucose uptake indicated that appropriate glucose uptake is essential for fish. Overall, elevated carnitines correlated with decreased protein and lipid deposition phenotype, which could be explained by the upregulated transcriptional expression of genes involved in protein and amino acid degradation, lipolysis, and FAO. Therefore, we proposed that glut2-deletion may have activated AMPK signaling associated with catabolic metabolism in zebrafish via insufficient ATP production. This hypothesis is supported by the reduced ATP content in the liver and muscle of MZglut2 fish, which was reflected by the decreased motility, increased protein levels of P-AMPK, and transcriptional expression of the above-mentioned genes in MZglut2 fish.

The complete lethality observed in Glut2 homozygous mice, which died between 2 and 3 weeks of age (20), was not seen in glut2−/− and MZglut2 zebrafish. In the present study, elevated glut1 expression was observed in the MZglut2 fish intestine. Conversely, we speculated that incomplete lethality probably resulted from fish having a higher tolerance for hypoglycemia than mammals (56) or that insulin signaling has divergent roles between fish and mammals (57). Similar differences in survival between mammals and teleosts were observed in cyp17a1 knockout fish, which would not cause lethality in fish (58), while loss of Cyp17a1 leads to embryonic lethality in mice by embryonic day 7 (before gastrulation) (59). Therefore, in addition to compensatory glut1 expression in the intestine, incomplete lethality could be explained by the differentiated function and requirement of GLUT2 between mammals and teleosts. Hence, zebrafish that survived after blocking glucose uptake by knocking out glut2 had lower blood glucose levels than control fish and enhanced lipids and protein catabolism to meet energy requirements. These findings may be a potential mechanism for energy homeostasis remodeling caused by blocked glucose uptake in fish. It could also be a potential strategy for fish to adapt to hypoglycemia.

Conclusion

In summary, we have provided new insights into the function of glut2 and shed new light on the regulation of lipid and protein deposition by glucose uptake. The promotion of protein and amino acid degradation in muscle and lipolysis and FAO in the liver of MZglut2 fish are the primary adaptive metabolic responses. We suggest that glut2-deletion and attenuated glucose uptake cause the above phenotype decreases anabolism by inactivating insulin and increases catabolism by activating the AMPK signaling pathway. These results first demonstrated the metabolic consequences of glucose uptake attenuation in MZglut2 fish and provided a valuable theoretical basis and practical guidance for the establishment of a potential strategy for manipulating glucose uptake.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were performed according to the Guide for Animal Care and Use Committee of Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IHB, CAS, Protocol No. 2016–018).

Author contributions

DH and ZY: conceptualization. LX, GZ, YL, YG, and QL: investigation. ZZ, HL, and JJ: methodology. LX and GZ: writing. XZ, ZY, and SX: writing, reviewing, and editing. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final version.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Guanghan Nie for his technical help. We would like to thank Guangxin Wang at the Analysis and Testing Center of the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for the β-cell observations and photography.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation, China (U21A20266, 31972771, 31972805, and 31672670), the National Key Research and Development Program, China (2018YFD0900404 and 2018YFD0900205), the Pilot Program A Project from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA08010405), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS (2013223 to DH and 20200336 to GZ), and the State Key Laboratory of Freshwater Ecology and Biotechnology (2022FBZ03).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1187283/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Wilson RP. Utilization of dietary carbohydrate by fish. Aquaculture. (1994) 124:67–80. 10.1016/0044-8486(94)90363-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prisingkorn W, Prathomya P, Jakovlic I, Liu H, Zhao YH, Wang WM. Transcriptomics, metabolomics and histology indicate that high-carbohydrate diet negatively affects the liver health of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). BMC Genomics. (2017) 18:856. 10.1186/s12864-017-4246-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gong YL, Lu QS, Liu YL, Xi LW, Zhang ZM, Liu HK, et al. Dietary berberine alleviates high carbohydrate diet-induced intestinal damages and improves lipid metabolism in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Front Nutr. (2022) 9:1010859. 10.3389/fnut.2022.1010859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taj S, Li XJ, Zhou QC, Irm M, Yuan Y, Shi B, et al. Insulin-mediated glycemic responses and glucose homeostasis in black sea bream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii) fed different carbohydrate sources. Aquaculture. (2021) 540:736726. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.736726 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kostyniuk DJ, Marandel L, Jubouri M, Dias K, de Souza RF, Zhang DP, et al. Profiling the rainbow trout hepatic miRNAome under diet-induced hyperglycemia. Physiol Genomics. (2019) 51:411–31. 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00032.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su JZ, Mei LY, Xi LW, Gong YL, Yang YX, Jin JY, et al. Responses of glycolysis, glycogen accumulation and glucose-induced lipogenesis in grass carp and Chinese longsnout catfish fed high-carbohydrate diet. Aquaculture. (2021) 533:736146. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.736146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimitriadis G, Mitrou P, Lambadiari V, Maratou E, Raptis SA. Insulin effects in muscle and adipose tissue. Diabetes Res Clin Pr. (2011) 93:S52–9. 10.1016/S0168-8227(11)70014-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu LY, Zhang LN, Li BH, Jiang HW, Duan YN, Xie ZF, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) regulates energy metabolism through modulating thermogenesis in adipose tissue. Front Physiol. (2018) 9:122. 10.3389/fphys.2018.00122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA. AMPK a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. (2012) 13:251–62. 10.1038/nrm3311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li LY, Li JM, Ning LJ, Lu DL, Luo Y, Ma Q, et al. Mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation inhibition promotes glucose utilization and protein deposition through energy homeostasis remodeling in fish. J Nutr. (2020) 150:2322–35. 10.1093/jn/nxaa187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magnoni LJ, Vraskou Y, Palstra AP, Planas JV. AMP-activated protein kinase plays an important evolutionary conserved role in the regulation of glucose metabolism in fish skeletal muscle cells. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e31219. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li LY, Lv HB, Jiang ZY, Qiao F, Chen LQ, Zhang ML, et al. Peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor alpha-b deficiency induces the reprogramming of nutrient metabolism in zebrafish. J Physiol-London. (2020) 598:4537–53. 10.1113/JP279814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uldry M, Thorens B. The SLC2 family of facilitated hexose and polyol transporters. Pflug Arch Eur J Phy. (2004) 448:259–60. 10.1007/s00424-004-1264-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorens B, Cheng ZQ, Brown D, Lodish HF. Liver glucose transporter: a basolateral protein in hepatocytes and intestine and kidney cells. Am J Physiol. (1990) 259:279–85. 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.2.C279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorens B, Sarkar HK, Kaback HR, Lodish HF. Cloning and functional expression in bacteria of a novel glucose transporter present in liver, intestine, kidney, and beta-pancreatic islet cells. Cell. (1988) 55:281–90. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90051-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorens B. Molecular and cellular physiology of GLUT-2, a high-Km facilitated diffusion glucose transporter. Int Rev Cytol. (1992) 137A:209–238. 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62677-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thorens B. GLUT2, glucose sensing and glucose homeostasis. Diabetologia. (2015) 58:221–32. 10.1007/s00125-014-3451-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santer R, Schneppenheim R, Dombrowski A, Gotze H, Steinmann B, Schaub J. Mutations in GLUT2, the gene for the liver-type glucose transporter, in patients with Fanconi-Bickel syndrome. Nat Genet. (1997) 17:298–298. 10.1038/ng0398-298a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stümpel F, Burcelin R, Jungermann K, Thorens B. Normal kinetics of intestinal glucose absorption in the absence of GLUT2: evidence for a transport pathway requiring glucose phosphorylation and transfer into the endoplasmic reticulum. P Natl Acad Sci USA. (2001) 98:11330–5. 10.1073/pnas.211357698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillam MT, Hummler E, Schaerer E, Yeh JI, Birnbaum MJ, Beermann F, et al. Early diabetes and abnormal postnatal pancreatic islet development in mice lacking Glut-2. Nat Genet. (1997) 18:88–88. 10.1038/ng0198-88c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rorsman P, Rorsman P. Pancreatic β-cell electrical activity and insulin secretion: of mice and men. Physiol Rev. (2018) 98:117–214. 10.1152/physrev.00008.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorens B, Guillam MT, Beermann F, Burcelin R, Jaquet M. Transgenic reexpression of GLUT1 or GLUT2 in pancreatic beta cells rescues GLUT2-null mice from early death and restores normal glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. (2000) 275:23751–8. 10.1074/jbc.M002908200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordeiro LMD, Bainbridge L, Devisetty N, McDougal DH, Peters DJM, Chhabra KH. Loss of function of renal Glut2 reverses hyperglycaemia and normalises body weight in mouse models of diabetes and obesity. Diabetologia. (2022) 65:1032–47. 10.1007/s00125-022-05676-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ran H, Lu Y, Zhang Q, Hu QY, Zhao JM, Wang K, et al. MondoA is required for normal myogenesis and regulation of the skeletal muscle glycogen content in mice. Diabetes Metab J. (2021) 45:797–797. 10.4093/dmj.2021.0251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang BY, Zhai G, Gong YL, Su JZ, Peng XY, Shang GH, et al. Different physiological roles of insulin receptors in mediating nutrient metabolism in zebrafish. Am J Physiol-Endoc M. (2018) 315:E38–51. 10.1152/ajpendo.00227.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun S, Cao XJ, Castro LFC, Monroig O, Gao J, A. network-based approach to identify protein kinases critical for regulating srebf1 in lipid deposition causing obesity. Funct Integr Genomic. (2021) 21:557–70. 10.1007/s10142-021-00798-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dynam. (1995) 203:253–310. 10.1002/aja.1002030302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao WL, Qin CB, Yang GK, Yan X, Meng XL, Yang LP, et al. Expression of glut2 in response to glucose load, insulin and glucagon in grass carp (Ctenophcuyngodon idellus). Comp Biochem Phys B. (2020) 239:110351. 10.1016/j.cbpb.2019.110351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mali P, Yang LH, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. (2013) 339:823–6. 10.1126/science.1232033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang BY, Zhai G, Gong YL, Su JZ, Han D, Yin Z, et al. Depletion of insulin receptors leads to β-cell hyperplasia in zebrafish. Sci Bull. (2017) 62:486–92. 10.1016/j.scib.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu RL, Lu Y, Peng XY, Jia JY, Ruan YL, Shi SC, et al. Enhanced insulin activity achieved in VDRa/b ablation zebrafish. Front Endocrinol. (2023) 14:1054665. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1054665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eide M, Rusten M, Male R, Jensen KHM, Goksoyr A, A. characterization of the ZFL cell line and primary hepatocytes as in vitro liver cell models for the zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquat Toxicol. (2014) 147:7–17. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xi LW, Lu QS, Liu YL, Su JZ, Chen W, Gong YL, et al. Effects of fish meal replacement with Chlorella meal on growth performance, pigmentation, and liver health of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Anim Nutr. (2022) 10:26–40. 10.1016/j.aninu.2022.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu PF, Zhu KY, Jin Y, Chen Y, Sun XJ, Deng M, et al. Setdb2 restricts dorsal organizer territory and regulates left-right asymmetry through suppressing fgf8 activity. P Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107:2521–6. 10.1073/pnas.0914396107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gong YL, Yang BY, Zhang DD, Zhang Y, Tang ZH, Yang L, et al. Hyperaminoacidemia induces pancreatic α cell proliferation via synergism between the mTORC1 and CaSR-Gq signaling pathways. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:235. 10.1038/s41467-022-35705-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Low BSJ, Lim CS, Ding SSL, Tan YS, Ng NHJ, Krishnan VG, et al. Decreased GLUT2 and glucose uptake contribute to insulin secretion defects in MODY3/HNF1A hiPSC-derived mutant β cells. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:3133. 10.1038/s41467-021-22843-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thiss C, Thisse B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc. (2008) 3:59–69. 10.1038/nprot.2007.514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng XY, Shang GH, Wang WQ, Chen XW, Lou QY, Zhai G, et al. Fatty acid oxidation in zebrafish adipose tissue is promoted by 1alpha,25(OH)2D3. Cell Rep. (2017) 19:1444–55. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu QS, Xi LW, Liu YL, Gong YL, Su JZ, Han D, et al. Effects of dietary inclusion of Clostridium autoethanogenum protein on the growth performance and liver health of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Front Mar Sci. (2021) 8:764964. 10.3389/fmars.2021.76496435647322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han SL, Qian YC, Limbu SM, Wang J, Chen LQ, Zhang ML, et al. Lipolysis and lipophagy play individual and interactive roles in regulating triacylglycerol and cholesterol homeostasis and mitochondrial form in zebrafish. BBA-Mol Cell Biol L. (2021) 1866:158988. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2021.158988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi C, Lu Y, Zhai G, Huang JF, Shang GH, Lou QY, et al. Hyperandrogenism in POMCa-deficient zebrafish enhances somatic growth without increasing adiposity. J Mol Cell Biol. (2020) 12:291–304. 10.1093/jmcb/mjz053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prasath GS, Subramanian SP. Modulatory effects of fisetin, a bioflavonoid, on hyperglycemia by attenuating the key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism in hepatic and renal tissues in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol. (2011) 668:492–6. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li LY, Limbu SM, Ma Q, Chen LQ, Zhang ML, Du ZY. The metabolic regulation of dietary L-carnitine in aquaculture nutrition: present status and future research strategies. Rev Aquacult. (2019) 11:1228–57. 10.1111/raq.12289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bodine SC, Baehr LM. Skeletal muscle atrophy and the E3 ubiquitin ligases MuRF1 and MAFbx/atrogin-1. Am J Physiol-Endoc M. (2014) 307:E469–484. 10.1152/ajpendo.00204.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tso SC, Qi XB, Gui WJ, Chuang JL, Morlock LK, Wallace AL, et al. Structure-based design and mechanisms of allosteric inhibitors for mitochondrial branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase. P Natl Acad Sci USA. (2013) 110:9728–33. 10.1073/pnas.1303220110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gale SM, Castracane VD, Mantzoros CS. Energy homeostasis, obesity and eating disorders: Recent advances in endocrinology. J Nutr. (2004) 134:295–8. 10.1093/jn/134.2.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holman GD. Structure, function and regulation of mammalian glucose transporters of the SLC2 family. Pflug Arc Eur J Phy. (2020) 472:1155–75. 10.1007/s00424-020-02411-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharari S, Abou-Alloul M, Hussain K, Khan FA. Fanconi–bickel syndrome: a review of the mechanisms that lead to dysglycaemia. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:6286. 10.3390/ijms21176286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hernandez-Sanchez C, Mansilla A, de la Rosa EJ, de Pablo F. Proinsulin in development: new roles for an ancient prohormone. Diabetologia. (2006) 49:1142–50. 10.1007/s00125-006-0232-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Do HO, Thorn P. Insulin secretion from beta cells within intact islets: Location matters. Clin Exp Pharmacol P. (2015) 42:406–14. 10.1111/1440-1681.12368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herzig S, Shaw RJ. AMPK guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. (2018) 19:121–35. 10.1038/nrm.2017.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seyer P, Vallois D, Poitry-Yamate C, Schutz F, Metref S, Tarussio D, et al. Hepatic glucose sensing is required to preserve beta cell glucose competence. J Clin Invest. (2013) 123:1662–76. 10.1172/JCI65538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hardie DG, AMPK. positive and negative regulation, and its role in whole-body energy homeostasis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. (2015) 33:1–7. 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin SC, Hardie DG. AMPK Sensing glucose as well as cellular energy status. Cell Metab. (2018) 27:299–313. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thirunavukkarasar R, Kumar P, Sardar P, Sahu NP, Harikrishna V, Singha KP, et al. Protein-sparing effect of dietary lipid: Changes in growth, nutrient utilization, digestion and IGF-I and IGFBP-I expression of Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (GIFT), reared in Inland Ground Saline Water. Anim Feed Sci Tech. (2022) 284:115150. 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2021.115150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wright JR, Bonen A, Conlon JM, Pohajdak B. Glucose homeostasis in the teleost fish tilapia: insights from Brockmann body xenotransplantation studies. Am Zool. (2000) 40:234–45. 10.1093/icb/40.2.234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Retaux S. The healthy diabetic cavefish conundrum. Nature. (2018) 555:595–7. 10.1038/d41586-018-03242-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhai G, Shu TT, Xia YG, Lu Y, Shang GH, Jin X, et al. Characterization of Sexual Trait Development in cyp17a1-Deficient Zebrafish. Endocrinology. (2018) 159:3549–62. 10.1210/en.2018-00551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bair SR, Mellon SH. Deletion of the mouse P450c17 gene causes early embryonic lethality. Mol Cell Biol. (2004) 24:5383–90. 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5383-5390.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.