Abstract

High-throughput 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing technology is widely applied for environmental microbiota structure analysis to derive knowledge that informs microbiome-based surveillance and oriented bioengineering. However, it remains elusive how the selection of 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions and reference databases affects microbiota diversity and structure profiling. This study systematically evaluated the fitness of different frequently used reference databases (i.e. SILVA 138 SSU, GTDB bact120_r207, Greengenes 13_5 and MiDAS 4.8) and primers of 16S rRNA gene in microbiota profiling of anaerobic digestion and activated sludge collected from a full-scale swine wastewater treatment plant (WWTP). The comparative results showed that MiDAS 4.8 achieved the highest levels of taxonomic diversity and species-level assignment rate. For whichever sample groups, microbiota richness captured by different primers decreased in the following order: V4 > V4-V5 > V3-V4 > V6-V8/V1-V3. Using primer-bias-free metagenomic data results as the judging standard, V4 region also best characterized microbiota structure and well represented typical functional guilds (e.g. methanogens, ammonium oxidizers and denitrifiers), while V6-V8 regions largely overestimated the archaeal methanogens (mainly Methanosarcina) by over 30 times. Therefore, MiDAS 4.8 database and V4 region are recommended for best simultaneous analysis of bacterial and archaeal community diversity and structure of the examined swine WWTP.

Keywords: swine wastewater treatment, 16S rRNA gene hypervariable region, reference database, microbiota structure, functional guilds

1. Introduction

The proportion of swine wastewater produced from centralized large-scale pig farms has significantly increased worldwide in recent decades due to the growing demand for food. According to a recent report by the US Department of Agriculture, intensive pig farms produced approximately 105 million tons of pork in 2019–2022, consuming around 105 million tons per year [1], which consumed about 500 billion m3 of water per year (1 kg pork production would consume 4850 l water [2]), in consequence producing a large amount of swine wastewater. Even though the properties of swine wastewater vary a lot according to the area, farming strategies and water use pattern, swine wastewater is a typical kind of high-strength livestock wastewater with high concentrations of total nitrogen (300–1500 mg N l−1), total phosphorus (10–100 mg P l−1) and organic pollutant (COD: 1300–15 000 mg O l−1) [3–5], which are 10–100 times higher than those found in in municipal wastewater. Without proper treatment, swine wastewater will greatly contribute to global warming, soil acidification and eutrophication [6].

In comparison to physical and chemical wastewater treatment methods, biological processes are more cost-effective and environmentally friendly. Therefore, biological processes are commonly used for swine wastewater treatment. Swine wastewater contains a high proportion of biodegradable organics and is suitable for treatment using anaerobic digestion (AD) process, where the engineered microbial community (i.e. microbiota) is an assemblage of closely interacted bacterial and archaeal functional guilds that occupy four trophic levels (i.e. hydrolysis, fermentation, acetogenesis and methanogenesis). These guilds work together to convert carbohydrates, proteins and lipids via fatty acids and alcohols to methanogenic substrates (i.e. acetate, H2/formate and CO2) [7] and eventually produce methane as renewable bioenergy [8]. In most cases, the residual pollutants (particularly ammonium nitrogen and organic matters) in the AD liquor are further removed in the traditional anoxic/oxic activated sludge (AS) process. In the oxic unit, the ammonium nitrogen is sequentially converted by ammonia-oxidizing and nitrite-oxidizing microbes to nitrite or nitrate (nitrification process). In the anoxic unit, the nitrite and nitrate together with organic matter are consumed simultaneously by denitrifying bacteria (denitrification process).

High-throughput 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing technology is the most widely used technology to investigate microbiota diversity and structure in various natural or engineered systems, informing microbiome-based system surveillance and oriented engineering operation [9]. However, the selection of PCR primer for the 16S rRNA gene significantly affected the resulting microbial composition and specific population abundances [10–12]. The optimal primers can vary for different environmental ecosystems, habitats or samples. Recent studies on engineered microbiota mainly focused on municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). Research by Nielsen's group on WWTP microbiota indicated that V1-V3 region amplicon of 16S rRNA gene provided the highest taxonomic resolution for AS bacteria, compared with other primer sets (i.e. V3-V4, V3-V5, V4, V4-V5 and V5-V8) [13], and the result was consistent with those obtained from metagenomic data and quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [14]. While another study recommended using V3-V4 for profiling AS bacteria, as these regions provided higher genus-level taxonomic coverage and more accurate diversity quantification than other primer sets (targeting V1-V2, V4-V5, V5-V6 and V7-V9) [15]. However, both the V1-V3 and V3-V4 are bacteria-specific primer sets and may not work for archaea [16], which also play a non-negligible role in WWTPs, especially for the AD systems [17]. To investigate the microbiota comprehensively, some researchers also used the V1-V3 regions for bacteria identification and the V6-V8 regions for simultaneous bacterial and archaeal identification [18,19]. Notably, universal primers of V4_2 (primer set of 515F (Parada) |806R (Apprill) [20,21]), modified from the origin V4_1 (primer set of 515F (Caporaso) |806R (Caporaso) [22]) and V4-V5 have been recommended by Earth Microbiome Project (http://earthmicrobiome.org/protocols-and-standards/16s/). A study by Wu et al. [23], which examined 269 WWTPs in 23 countries on six continents, showed that V4_2 covered 86.8% and 52.9% of all bacterial and archaeal sequences with 0 mismatches, respectively. Comparatively, although shotgun metagenomic sequencing is free of primer-related biases, it generates shorter reads than 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and is much more expensive. Thus, it is not an economically attractive methodological substitute for 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing in terms of profiling microbiota structure, unless the generated shot-gun metagenomes are also expected to be used for functional analysis in microbiome research [24].

Due to the notable differences in the characteristics of municipal wastewater and swine wastewater, the treatment facilities for swine WWTPs may contain microbiota with significantly distinct diversity and compositions compared to those found in municipal WWTPs. Therefore, the ideal 16S primer set for analysing the microbiota of swine WWTPs may differ from the one commonly used for municipal WWTPs. Moreover, although more high-quality reference databases of 16S rRNA gene sequences (e.g. GTDB bact120_r207 [25] and MiDAS 4.8 [16]) are now freely available, it remains unknown which databases and primer sets work the best for profiling the engineered microbiota structure in swine WWTPs. Hence, this study aims to select a suitable primer set and a taxonomic annotation database of 16S rRNA gene sequences for specific swine wastewater AD system and AS system. The evaluations of the 16S rRNA gene amplicon primers (including bacteria-specific primers of V1-V3 and V3-V4, universal primers of V4, V4-V5 and V6-V8) mainly focus on the microbiota structure and functional guilds by using 16S rRNA reads extracted from metagenomic data (free from 16S primer bias) as a reference standard.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample collection

The suspended sludge samples were collected from the AD tank, anoxic tank (AT) and oxic tank (OT) of a full-scale swine WWTP (with 260 t d−1 treatment capacity) of an intensive pig farm located in Nanjing city, China, on 13 July 2021. This swine WWTP was under good operational conditions and had been stably running for six months prior to sampling.

2.2. DNA extraction, 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and data analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the above-mentioned samples (2 g per sample) using FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Six commonly used 16S rRNA gene primers (i.e. V1-V3, V3-V4, V4_1, V4_2, V4-V5 and V6-V8; details shown in table 1) were used to amplify 16S rRNA genes. The amplified 16S rRNA genes were sequenced on the Illumina platforms with the sequencing strategy of PE250 or PE300 at the Guangdong Magigene Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China).

Table 1.

16S rRNA gene primer sets and sources.

| region | primer pair | sequencing strategy | forward primer sequence (5′–3′) | reverse primer sequence (5′–3′) | reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1-V3 | 27F|534R | PE300 | AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG | ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG | [26] |

| V3-V4 | 338F|802R | PE250 | ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG | TACNVGGGTATCTAATCC | [27] |

| aV4 | 515F (Caporaso) |806R (Caporaso) | PE250 | GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA | GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT | [22] |

| aV4 | 515F (Parada) |806R (Apprill) | PE250 | GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA | GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT | b[20,21] |

| V4-V5 | 515F|926R | PE250 | GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA | CCGYCAATTYMTTTRAGTTT | b[21,28] |

| V6-V8 | 926F|1392R | PE300 | AAACTYAAAKGAATTGRCGG | ACGGGCGGTGWGTRC | [29] |

a515F (Caporaso) |806R(Caporaso) primer and 515F (Parada) |806R (Apprill) targeting on V4 region were labelled as V4_1 and V4_2, respectively.

bPrimer set recommended by the Earth Microbiome Project (https://earthmicrobiome.org/protocols-and-standards/16s/).

The short-read amplicon data using different primers were processed with QIIME2 (v. 2020.6) with the DADA2 pipeline [30]. The following steps were executed: (i) raw data import, (ii) read demultiplexing, (iii) chimeric sequence removal and (iv) denoizing and quality control filtering using DADA2 algorithm (parameters used are listed in electronic supplementary material, table S1) to generate amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). The rarefaction analysis was performed with ASVs for all libraries. The operational taxonomic unit (OTU) table was generated based on 97% sequence similarity for 16S rRNA genes. Taxonomic annotation of sequences was performed with different annotation databases, namely Silva database (v. 138 SSU), Greengenes database (v. 13_5), GTDB database (v bact120_r207) and MiDAS database (v. 4.8) [16].

2.3. DNA extraction for metagenome sequencing, sequence processing and data analysis

Metagenome sequencing data can provide more realistic estimates of community richness by avoiding the biases related to amplification and primer mismatch than short-read 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing data. Hence, the metagenomic data were used as the standard of taxonomic analysis to evaluate the quantitative accuracy of different primers used in this study. Genomic DNAs were extracted from raw sludge samples (2 g per sample) using Mag-Bind Soil DNA Kit (Omega, M5635, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions, and prepared for shot-gun metagenomic sequencing on Illumina's Novaseq platform using PE150 sequencing strategy at the Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

The metagenomic rRNA gene reads used for taxonomic analysis were extracted from the clean reads post initial quality filtering using a kmer strategy in BBDuk from the BBMap tool suite (https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/) [31]. These rRNA reads were aligned to MiDAS 4.8 [16] reference database using the usearch_global algorithm implemented in VSEARCH (v. 2.7.0) [32] with the parameter of -id 0.97. Taxonomic annotation was manually added to the OTU table in R.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in R (v. 4.2.1) [33], RStudio (2022.07.1 Build 554) [34] and Microsoft Excel 365. The α-diversity analysis was conducted using the vegan R package (v. 2.6-2) in R. Bray–Curtis-based nonmetric multidimensional scaling (Bray–Curtis-based NMDS) was used to evaluate the similarity of microbiota structure with 16S rRNA sequences generated from the selected primer sets and metagenomic reads, using vegan R package. The quantifications of essential microorganisms, and functional bacteria of AD system (including fermentative microorganisms (fermenters), acetogenic microorganisms (acetogens) and methanogenic microorganisms (methanogens)) and AS (including ammonium-oxidizing bacteria (AOBs), nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOBs) and denitrifiers) were calculated at genus level in Microsoft Excel 365. The upset figure was made by using TBtools software [35]. All the other figures were drawn using OriginPro 2021.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Microbiota diversity in the swine WWTP determined by different hypervariable regions and reference databases

3.1.1. Alpha diversity

To evaluate the fitness of different universal (V4, V4-V5 and V6-V8) and bacteria-specific (V1-V3 and V3-V4) primer sets for microbiota diversity profiling, all the raw reads were preprocessed with DADA2 in Qiime 2. The quality control statistics, ASV and OUT counts are presented in electronic supplementary material, table S1. Although the number of reads generated from different primers varied greatly (ranging from 14 967 to 302 592 after quality control and denoizing), the rarefaction curves for observed ASVs (electronic supplementary material, figure S1) and Shannon index (electronic supplementary material, figure S2) for all primers reached clear saturation, indicating that 16S amplicon sequencing data were sufficient for revealing microbiota structure. The universal V4_2 primer generated the highest ASV number (1156, 1766 and 1713 for AD, AT and OT samples, respectively) and OTU number (944, 1396 and 1378 for AD, AT and OT samples, respectively); while V6-V8 primer generated the lowest ASV number (204, 522 and 458 for AD, AT and OT samples, respectively) and OTU number (150, 380 and 349 for AD, AT and OT samples, respectively). Previous studies on microbiota diversity also suggested that amplicons originating from the V6-V8 regions are less available than those from the V3-V5 regions (in autothermal thermophilic aerobic digestion sample) [36] or the V1-V3 regions (in cattle rumen sample) [37].

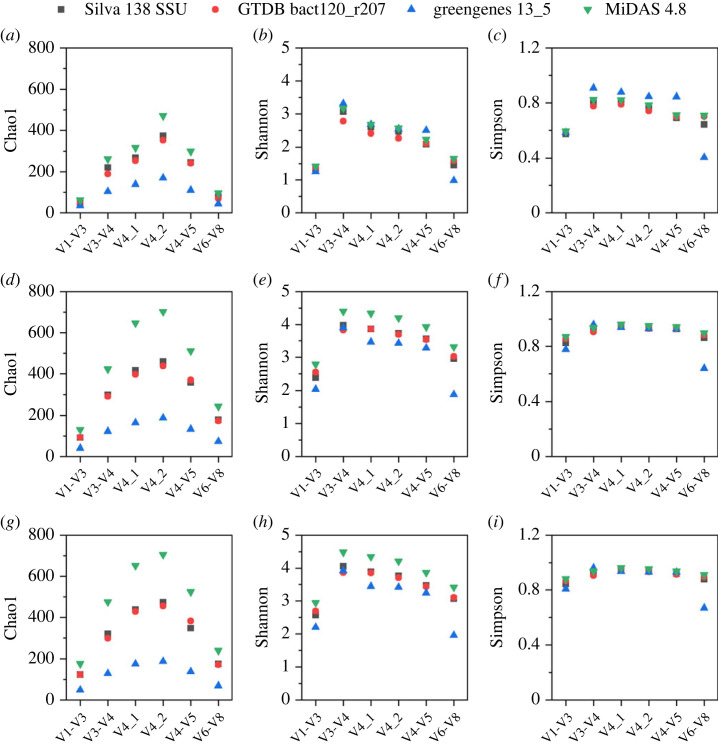

These OTUs generated from the selected six primer pairs were assigned to four commonly used databases (i.e. SILVA 138 SSU, GTDB bact120_r207, Greengenes 13_5 and MiDAS 4.8) and the measured alpha diversity matrixes at the genus and species levels from them are shown in figure 1 and electronic supplementary material, figure S3, respectively. For whichever primers, the Chao1 values at genus level (an estimator of the richness of genera, higher values of Chao1 indicating greater microbial richness) decreased in the order of MiDAS 4.8, SILVA 138 SSU, GTDB bact120_r207 and Greengenes 13_5. For swine wastewater AS samples (AT and OT samples), the alpha diversity (considering both microbial richness and evenness, indicated by Shannon index) at genus level based on MiDAS 4.8 was higher than those based on the other three universal reference databases. For AD sample, the values of Shannon index of the four databases were comparable; but the Simpson index result indicated that Greengenes 13_5 database harboured slightly higher alpha diversity than the others. While, considering the least genera identified by Greengenes 13_5 (maximum of 169 genera detected with V4_2 primer), the MiDAS 4.8 database obtained the highest genus number (maximum of 470 genera detected with V4_2 primer). The MiDAS 4.8 reference also exhibited sound microbiota diversity and was the optimal taxonomic database for swine wastewater AD system. Moreover, the percentages of 16S rRNA reads classified at genus level were highest in MiDAS 4.8 database for all samples (electronic supplementary material, figure S5). Therefore, the following taxonomic analysis was based on MiDAS 4.8 reference.

Figure 1.

Alpha diversity at OTU obtained with different primer sets classified at genus level. The analysis was performed by using databases SILVA 138 SSU, GTDB bact120_r207, Greengenes 13_5 and MiDAS 4.8. Chao1 (a), Shannon (b) and Simpson (c) diversity index of AD sample; Chao1 (d), Shannon (e) and Simpson (f) diversity index of AT sample; Chao1 (g), Shannon (h) and Simpson (i) diversity index of OT sample.

On the other hand, in whichever reference databases, the Chao1 values of all three examined samples suggested that the microbial richness obtained by using different primers decreased in the following order: V4 > V4-V5 > V3-V4 > V6-V8/V1-V3. Considering both the richness of genera and their relative abundance, the Shannon index and Simpson index (namely, Gini-Simpson index) of amplicons of different primers are also compared in figure 1. Higher values of Shannon index and Simpson index indicated greater microbial diversity. The Shannon index was highest with V3-V4 amplicon; while the Simpson index of V4_1, V3-V4 and V4_2 amplicons was comparable (reference database: MiDAS 4.8). Therefore, considering both microbial richness and evenness, the V4_2, V4_1 and V3-V4 primers can be good options for microbiota profiling in swine wastewater AD and AS samples. It should be noted that the alpha diversity based on 16S rRNA reads extracted from metagenomic data (abbreviated to ‘Meta') was significantly higher than those based on the 16S amplicon reads (reference database: MiDAS 4.8, shown in electronic supplementary material, figure S3); Chao1 values of swine wastewater AD, AT and OT samples based on Meta were 1105, 1138 and 1033, respectively (at genus level).

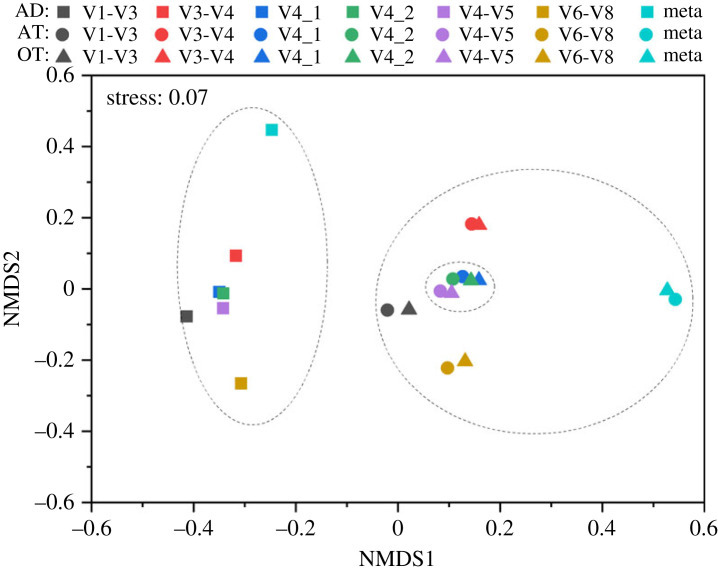

3.1.2. Beta diversity

The Bray–Curtis-based NMDS analysis effectively illustrated the dissimilarity in the microbial structure of the swine wastewater AD and AS samples using different 16S primer sets, with a low stress value of 0.07 (figure 2). The distance between communities reflects their dissimilarity, where closer distances indicate similar structures. Among the selected primers, the AS (AT and OT) samples were found to be similar to each other; while the AD sample distance was far away from AS samples. These might be because the environmental conditions of the AD system were significantly different from those of the AS system (such as the electronic conductivity, ammonium, total nitrogen, total organic carbon concentrations), and in AT and OT, similar environment conditions inducing by the inner recirculation of wastewater and sludge (the only obvious difference is that the DO level of OT was higher than that of AT). For all treatment units, the similarities between the V4_1, V4_2 and V4-V5 amplicons were high, while the V1-V3 and V6-V8 amplicons were found to be the farthest apart. For AD sample, the microbial structure based on V1-V3 amplicons was the closest to that based on extracted metagenomic 16S rRNA reads (Meta); while for the AS samples, the microbial structures based on V4_1 amplicons were the closest to those based on Meta. The NMDS analysis of the 16S rRNA reads of the six primer sets and metagenomic data assigned to Silva 138 SSU database at genus level suggested similar results (shown in electronic supplementary material, figure S6).

Figure 2.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis of microbiota structure based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities. The analysis was performed with selected primer 16S rRNA amplicon reads and metagenomic extracted 16S rRNA reads classified at genus level with MiDAS 4.8 as the database for taxonomic assignment. The black dashed circles were manually added for demonstration purposes.

3.2. Microbiota composition in the swine WWTP revealed by different 16S rRNA gene primers

3.2.1. Microbiota composition in anaerobic digestion system

Identifying the most sensitive and specific universal 16S rRNA gene primer greatly depends on the sample type and the target species [12]. For the studied swine WWTP, the AD sample harboured lower microbial diversity than the AS samples, and the microbiota structure of the AD system was significantly dissimilar to that of the AS system. At the domain level (taxonomy assignment based on MiDAS 4.8 database), quantification results from V4_2 amplicon were closest to those from Meta in the AD sample (archaea accounted for 1.5% and 2% of total assigned microorganisms for Meta and V4_2, respectively) (shown in electronic supplementary material, figure S7). The V1-V3 amplicon could not detect any archaea [16], and the V3-V4 amplicon only identified an archaea abundance of 0.1%. The V4-V5, V4_1 and V6-V8 amplicons tended to overestimate archaea and resulted in archaea abundance of 4.7, 5.5 and 45.2%, respectively. Moreover, in the swine wastewater AD sample, the V1-V3, V3-V4, V4_1, V4_2, V4-V5 and V6-V8 amplicons detected 0, 2, 5, 7, 5 and 6 archaea genera, respectively. Hence, V4_2 was the most suitable primer for archaea detection in the swine wastewater AD system.

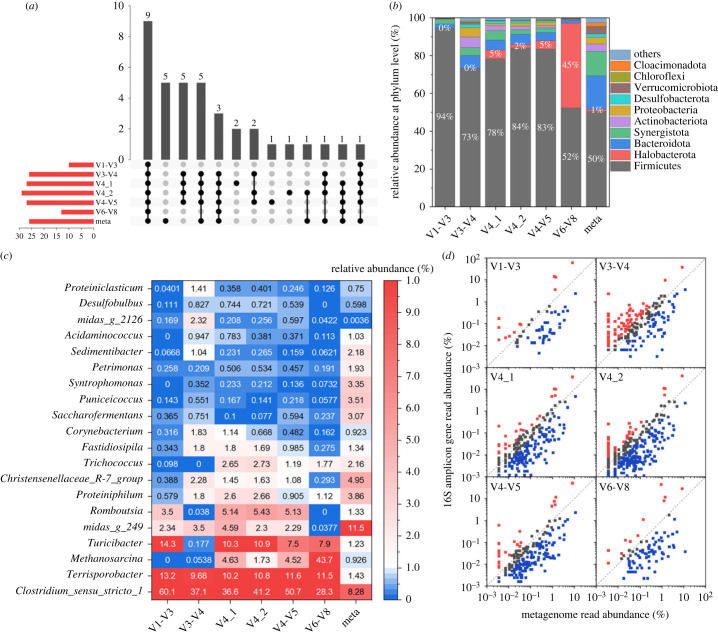

At the phylum level, the upset plot (figure 3a) showed the intersection and independence of the annotated phyla from the V1-V3, V3-V4, V4_1, V4_2, V4-V5, V6-V8 amplicons, and Meta. The V1-V3, V3-V4, V4_1, V4_2, V4-V5, V6-V8 amplicons and Meta identified 9, 26, 27, 29, 27, 13, 25, 37 phyla, respectively. They shared 9 phyla, namely, Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Synergistota, Actinobacteriota, Proteobacteria, Desulfobacterota, Verrucomicrobiota, Chloroflexi and Patescibacteria. V4_1 specifically identified Deferribacterota and Sumerlaeota; V4_1 specifically identified Thermoplasmatota; V4-V5 identified WS1; while all primer sets did not identify Fermentibacterota, SAR324_cladeMarine_group_B, Dadabacteria, Nitrospirota, Fusobacteriota.

Figure 3.

The microbial community composition of swine AD sample based on 16S rRNA amplicon reads and 16S rRNA reads extracted from metagenomic data. (a) The upset plot of detected phyla; (b) relative abundances of the top 10 phyla; (c) heatmap profiling based on the relative abundance of the top 20 genera; (d) comparison of relative abundance of genera based on selected primers 16S rRNA amplicon reads and metagenomic extracted 16S rRNA reads (genera present at greater than or equal to 0.001%); genera with less than twofold difference in relative abundance between the two data pools are shown with grey circles, those that are overrepresented by at least twofold with the 16S amplicon data are shown in red and the reverse in blue. V1-V3, V3-V4, V4_1, V4_2, V4-V5 and V6-V8 primers were used in 16S rRNA amplicon. The MiDAS 4.8 database was used for taxonomic classification.

As shown in figure 3b,c, in the swine wastewater AD sample, phylum of Firmicutes was the most abundant microorganism detected by all six amplicon data pools (greater than 50%). However, compared with Meta results, Firmicutes were overestimated by 16S amplicon data using whichever primers; the relative abundances of genera Clostridium sensu stricto 1 and Terrisporobacter, belonging to Firmicutes phylum detected by 16S amplicons, were 3.5–7.3 times higher than those using metagenomic data. On the contrary, the relative abundances of certain phyla, such as Bacteroidota, Synergistota and Verrucomicrobiota, were underestimated using 16S amplicons. Specifically, for the V1-V3 amplicon, genera of Clostridium sensu stricto 1, Terrisporobacter and Turicibacter (all belonging to Firmicutes phylum) together account for 87.6% in all detected microorganisms, which was only 10.9% using metagenomic data. Additionally, the V6-V8 amplicon detected a much higher relative abundance of the Methanosarcina genus (43.7%) from the Halobacterota phylum, compared to other amplicons (0–4.6%) or Meta (0.9%). A comparison of the genera with a relative abundance higher than 0.001% detected by the amplicons and Meta is shown in figure 3d. The numbers of genera with equal abundance (less than twofold difference compared with Meta) were 12, 54, 86, 84, 53 and 11 for the V1-V3, V3-V4, V4_1, V4_2, V4-V5 and V6-V8 amplicons, respectively. Thus, the V4_1 and V4_2 primers are recommended for use in swine wastewater AD system.

3.2.2. Microbiota composition in activated sludge system

In this study, the microbiota structures of the AT and OT samples were found to be very similar to each other (figure 2). Consequently, the diagnosis of microbiota structure and functional guilds of AS system was mainly represented by the corresponding analysis of the OT sample, while the related results of the AT sample are presented in the electronic supplementary material and described in electronic supplementary material, text S1. Generally, the archaea proportions of the AS system were significantly lower than those of the AD system. The quantifications of archaea from V4_2 and V4_1 amplicons were the closest to those from Meta in AS samples (AT sample: archaea accounted for 0.7% and 0.3% in the total assigned microorganisms for Meta and V4_2 amplicon, respectively; OT sample: archaea accounted for 0.9% and 0.7% in total assigned microorganisms for Meta and V4_1 amplicon, respectively) (shown in electronic supplementary material, figure S7).

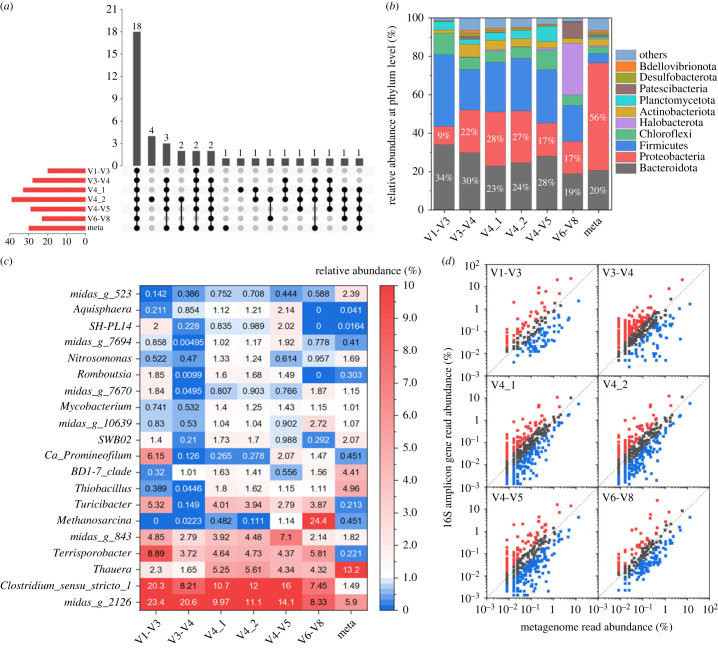

In the OT sample, the amplicons generated from the V1-V3, V3-V4, V4_1, V4_2, V4-V5 and V6-V8 primers and Meta identified 20, 28, 33, 39, 29, 23, 29, 41 phyla, respectively, and shared 18 phyla (shown in figure 4a). Notably, the V4_1 amplicon specifically identified Caldisericota; V4_2 amplicon identified WS1, WS2, Thermotogota, midas_p_7082. All amplicons failed to identify Fermentibacterota. With whichever amplicons, Bacteroidota (19–34%) and Proteobacteria (9–28%) were the most abundant phyla, which were comparable with Meta results (figure 4b,c). However, all the 16S amplicon data pools tended to overestimate the abundance of Firmicutes (by 2–55%) while underestimating the Proteobacteria (composed mainly of genera Thauera, Thiobacillus, BD1-7_clade and Arenimonas) (by 50–84%). Additionally, the numbers of equally abundant genera (compared to Meta results) in V1-V3, V3-V4, V4_1, V4_2, V4-V5 and V6-V8 amplicons were 44, 128, 166, 156, 102 and 71, respectively (figure 4d). Therefore, the V4_1 and V4_2 primers are good options for the swine wastewater AS system.

Figure 4.

The microbial community composition of swine OT sample based on 16S rRNA amplicon reads and 16S rRNA reads extracted from metagenomic data. (a) The upset plot of detected phyla; (b) relative abundances of the top 10 phyla; (c) heatmap profiling based on the relative abundance of the top 20 genera; (d) comparison of relative abundance of genera based on selected primer 16S rRNA amplicon reads and metagenomic extracted 16S rRNA reads (genera present at greater than or equal to 0.001%); genera with less than twofold difference in relative abundance between the two data pools are shown with grey circles, those that are overrepresented by at least twofold with the 16S amplicon data are shown in red and the reverse in blue. V1-V3, V3-V4, V4_1, V4_2, V4-V5 and V6-V8 primers were used in 16S rRNA amplicon. The MiDAS 4.8 database was used for taxonomic classification.

3.3. Functional guilds in the swine WWTP revealed by different 16S rRNA gene primers

3.3.1. Functional guilds in anaerobic digestion system

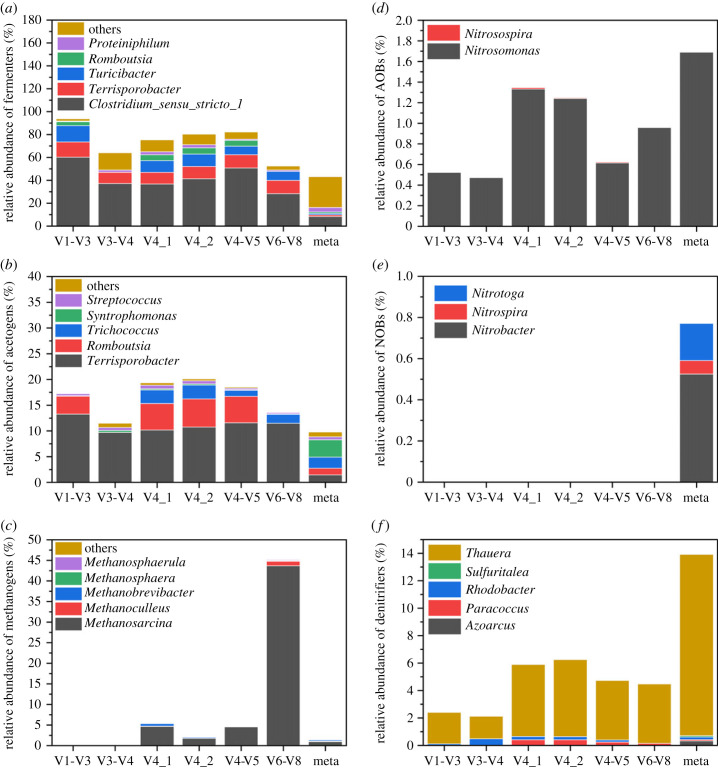

An AD is a complex engineered microbial ecosystem co-resided by hydrolytic, fermentative, acetogenic and methanogenic microorganisms. Here, functional guilds involved in AD processes were identified at the genus level, mainly based on the online Global MiDAS Field Guide (https://www.midasfieldguide.org/guide/search) and a self-collected list of reported functional genera. The genera Terrisporobacter, Romboutsia [38], Trichococcus and Ruminococcus were identified as fermenters and acetogens; Clostridium sensu stricto 1 was identified as fermentative bacteria [39,40]. The relative abundances of the functional guilds of swine wastewater AD samples are presented in figure 5a–c, and the relative abundances of all detected genera of fermenters, acetogens and methanogens are listed in electronic supplementary material, tables S2–S4, respectively. The high abundances of genera Clostridium sensu stricto 1 and Terrisporobacter resulted in higher proportions of fermenters and acetogens detected by all 16S amplicon data than those detected by Meta. Notably, the V1-V3 and V3-V4 amplicons did not target any methanogen; while the V6-V8 amplicon overestimated methanogen proportion by up to 292% (mainly overestimated the genus Methanosarcina). The quantifications of fermenters and acetogens based on the V6-V8 amplicon data were closest to those using Meta; while the quantification of methanogens by V4_2 amplicon was the most accurate.

Figure 5.

The relative abundances of functional guilds in the swine AD and AS systems (at genus level). The analysis is based on16S rRNA amplicon reads using V1-V3, V3-V4, V4_1, V4_2, V4-V5 and V6-V8 primers, and 16S rRNA reads extracted from metagenomic data. The MiDAS 4.8 database was used for taxonomic classification. (a) Relative abundance of fermenters in AD sample; (b) relative abundance of acetogens in AD sample; (c) relative abundance of methanogens in AD sample; (d) relative abundance of AOBs in OT sample; (e) relative abundance of NOBs in OT sample; (f) relative abundance of denitrifiers in OT sample.

In summary, the microbial community structure, composition and functional guilds of the swine wastewater AD system detected by V4_2 amplicon were the closest to Meta results.

3.3.2. Functional guilds in activated sludge system

The traditional AS system includes three types of bacteria for biological nitrogen removal: AOBs, NOBs and denitrifiers. The relative abundances of these functional bacteria in the OT and AT are shown in figure 5d,e and electronic supplementary material, figure S9, respectively. Generally, all the 16S rRNA amplicon data underestimated these functional guilds in the swine wastewater AS system (particularly for the V1-V3 and V3-V4 amplicons). Among the six studied primers, only V4_1 and V4_2 amplicons detected AOB genus Nitrosospira. Furthermore, the relative abundances of AOBs detected by V4_1 amplicon (0.9% in AT and 1.4% in OT) and V4_2 (0.9% in AT and 1.3% in OT) were the closest to those detected by Meta (1.0% in AT and 1.7% in OT). However, in the studied AS system, all amplicons failed to detect NOBs, whereas 0.8% relative abundance was detected by Meta in OT samples. In addition, the amplicon data detected only 6.2% relative abundance of denitrifies in the OT sample using the optimal primer V4_2, which was 55% lower than those detected by Meta (14%).

Overall, the results of microbial community structure, composition and functional guilds detected by V4_1 and V4_2 amplicons were the closest to the Meta results for the swine wastewater AS system.

3.4. Selections of taxonomic reference databases and primer in the swine WWTPs

In this study, three universal databases (i.e. SILVA 138 SSU, GTDB bact120_r207 and Greengenes 13_5) and one WWTP ecosystem-specific database (MiDAS 4.8) were compared. MiDAS 4.8 contains 5 million full-length 16S rRNA genes from 740 WWTPs across the world, using the Silva 138 NR99 taxonomy as a backbone, with stable placeholder names for unclassified taxa [13,16]. This database also provides a better coverage for wastewater treatment-related bacteria and improves the rate of genus and species level classification than the other universal annotation databases in the specific swine wastewater AD and AS systems.

On the other hand, the 16S amplicon data of this study were generated using Illumina MiSeq platform, which is a prevalent platform for short-read 16S sequencing. The PE250 sequencing strategy was used for the following four primers: V3-V4, V4_1, V4_2 and V4-V5. While, as V1-V3 and V6-V8 both target on three 16S hypervariable regions (longer than 460 bp), the sequencing strategy of PE300 was adopted for these two primers. Data sizes and quality of 16S gene reads generated from PE250 strategy were significantly higher than those generated from PE300 strategy. For example, the data sizes of PE250 were averagely four times higher than those of PE300; the average percentages of data passing the quality control were 90.6% and 56.4% for PE250 and PE300, respectively (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Therefore, the primers suitable for PE250 sequencing strategy provided higher data utilization rates (i.e. higher numbers of ASV and OTU) and were more cost-effective. Whereas the longer 16S reads (generated from V1-V3 and V6-V8) provided better taxonomy resolution and resulted in higher proportions of reads classified at genus/species level (electronic supplementary material, figure S4), which was also verified by previous studies on municipal WWTPs [13,26] and on rumen digesta [41]. However, the differences of the taxonomy resolutions between these two groups (primers using PE250 and primers using PE300) were dramatically decreased when a high-identity taxonomic reference database was selected. For example, in the studied swine wastewater AD sample, when taxonomy was assigned using Silva 138 SSU database, the percentages of 16S reads classified at species level were 72% and 14% for V6-V8 and V4_2, respectively. When taxonomy was assigned with MiDAS 4.8 database, these values were 83% and 70% for V6-V8 and V4_2, respectively (electronic supplementary material, figure S5).

The results of the current study suggested that primer selection was pivotal in reducing the primer-induced biases in 16S amplicon sequencing. To enable cross-study comparisons, the specific primer used in 16S amplicon sequencing should be taken into account. In this study, the universal primer targeting on V4 region (both V4_1 and V4_2 primer sets) exhibited better coverage of the microbial diversity for both archaea and bacteria, better representing the microbiota community structure and functional guilds in the swine WWTP. Similar results were also found in related studies on the eutrophic freshwater lake [12] and Kessler Farm soil [42]. However, the 16S amplicon data tend to overrepresent the abundant genera (i.e. Clostridium sensu stricto 1 and Terrisporobacter in examined swine wastewater AD sample), while underestimate or misidentify the rare genera. Since some rare bacteria play essential roles, their underestimation/misidentification might mislead the engineering operations. Therefore, the primer target on marker genes of the specific functional microorganism should be considered to achieve more accurate quantification. For example, for NOB identification and qualification in the studied AS system, instead of using the universal primer sets, the primers targeting on functional genes (Nitrite oxidoreductase genes, such as nxrA and nxrB [43]) can be used.

4. Conclusion

The selections of both taxonomic reference database and 16S rRNA gene primer significantly affected the profiling of microbiota and functional guilds in the swine wastewater AD and AS systems. Among the studied databases (SILVA 138 SSU, GTDB bact120_r207, Greengenes 13_5 and MiDAS 4.8), MiDAS 4.8 was the optimal taxonomic reference database, yielding sound microbial diversity and higher taxonomy resolution. Considering microbial richness and structure (for both archaea and bacteria), and qualification of majority of functional microorganisms in correspondence with metagenomic data (free of primer biases), the V4 primer (especially V4_2) was the optimal universal 16S rRNA primer. While the V1-V3 primer (not targeting on archaea) and V6-V8 primer (overestimating the specific archaea) were not suitable for the examined engineered microbiome system. These findings provide specific technical guidance to the selections of optimal universal 16S rRNA gene primers and taxonomy database for profiling microbiota structure and functional guilds in swine WWTPs. Additionally, they provide a technical paradigm for evaluating and standardizing 16S rRNA gene amplicon analysis protocols for microbiota structural analysis in other engineered microbial ecosystems.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the Westlake University HPC Center for computation support. We thank Ms. Yisong Xu for laboratory assistance and project management.

Data accessibility

Standard code for the reported R packages was used; any modifications are indicated in the Methods section. All raw sequence data of 16S rRNA gene amplicons and metagenomic sequencing generated in this study have been uploaded to China National GeneBank (CNGB) under the project accession number CNP0004305.

The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [44].

Authors' contributions

L.L.: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; F.J.: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LR22D010001 to F.J.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 42207546 to L.L.), the 2021 International Postdoctoral Exchange Fellowship Program supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. YJ20210302 to L.L.) and the Key R&D Program of Zhejiang (grant no. 2022C03075 to F.J.).

References

- 1.FAS USDA. 2023. Livestock and poultry: world markets and trade. United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agriculture Service. See https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/73666448x/f1882v52q/765389829/livestock_poultry.pdf.

- 2.Chapagain AK, Hoekstra A. 2008. Globalization of water: sharing the planet's freshwater resources. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishimoto C, Waki M, Soda S. 2021. Adaptation of anammox granules in swine wastewater treatment to low temperatures at a full-scale simultaneous partial nitrification, anammox, and denitrification plant. Chemosphere 282, 131027. ( 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishimoto C, Sugiyama T, Matsumoto T, Uenishi H, Fukumoto Y, Waki M. 2020. Full-scale simultaneous partial nitrification, anammox, and denitrification process for treating swine wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 81, 456-465. ( 10.2166/wst.2020.120) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magri A, Vanotti MB, Szogi AA. 2012. Anammox sludge immobilized in polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) cryogel carriers. Bioresour. Technol. 114, 231-240. ( 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.03.077) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkler T, Schopf K, Aschemann R, Winiwarter W. 2016. From farm to fork—a life cycle assessment of fresh Austrian pork. J. Clean. Prod. 116, 80-89. ( 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.01.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ju F, Lau F, Zhang T. 2017. Linking microbial community, environmental variables, and methanogenesis in anaerobic biogas digesters of chemically enhanced primary treatment sludge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 3982-3992. ( 10.1021/acs.est.6b06344) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lourinho G, Rodrigues LFTG, Brito PSD. 2020. Recent advances on anaerobic digestion of swine wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 17, 4917-4938. ( 10.1007/s13762-020-02793-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klimenko ES, Pogodina AV, Rychkova LV, Belkova NL. 2020. The ability of taxonomic identification of bifidobacteria based on the variable regions of 16S rRNA gene. Russ. J. Genet. 56, 926-934. ( 10.1134/S1022795420080074) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teng F, Nair SSD, Zhu PF, Li SS, Huang S, Li XL, Xu J, Yang F. 2018. Impact of DNA extraction method and targeted 16S-rRNA hypervariable region on oral microbiota profiling. Sci. Rep. 8, 16321. ( 10.1038/s41598-018-34294-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wear EK, Wilbanks EG, Nelson CE, Carlson CA. 2018. Primer selection impacts specific population abundances but not community dynamics in a monthly time-series 16S rRNA gene amplicon analysis of coastal marine bacterioplankton. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 2709-2726. ( 10.1111/1462-2920.14091) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang JY, et al. 2018. Evaluation of different 16S rRNA gene V regions for exploring bacterial diversity in a eutrophic freshwater lake. Sci. Total Environ. 618, 1254-1267. ( 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.228) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dueholm MS, Andersen KS, McIlroy SJ, Kristensen JM, Yashiro E, Karst SM, Albertsen M, Nielsen PH. 2020. Generation of comprehensive ecosystem-specific reference databases with species-level resolution by high-throughput full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing and automated taxonomy assignment (AutoTax). mBio 11, e01557-20. ( 10.1128/mBio.01557-20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albertsen M, Karst SM, Ziegler AS, Kirkegaard RH, Nielsen PH. 2015. Back to basics—the influence of DNA extraction and primer choice on phylogenetic analysis of activated sludge communities. PLoS ONE 10, e0132783. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0132783) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai L, Ye L, Tong AHY, Lok S, Zhang T. 2013. Biased diversity metrics revealed by bacterial 16s pyrotags derived from different primer sets. PLoS ONE 8, e53649. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0053649) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dueholm MS, Nierychlo M, Andersen KS, Rudkjobing V, Knutsson S, Albertsen M, Nielsen PH, Consortium MG. 2022. MiDAS 4: a global catalogue of full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences and taxonomy for studies of bacterial communities in wastewater treatment plants. Nat. Commun. 13, 1908. ( 10.1038/s41467-022-29438-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabatabaei M, Rahim RA, Abdullah N, Wright A-DG, Shirai Y, Sakai K, Sulaiman A, Hassan MA. 2010. Importance of the methanogenic archaea populations in anaerobic wastewater treatments. Process Biochem. 45, 1214-1225. ( 10.1016/j.procbio.2010.05.017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li FY, Henderson G, Sun X, Cox F, Janssen PH, Guan LL. 2016. Taxonomic assessment of rumen microbiota using total RNA and targeted amplicon sequencing approaches. Front. Microbiol. 7, 987. ( 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00987) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kittelmann S, Seedorf H, Walters WA, Clemente JC, Knight R, Gordon JI, Janssen PH. 2013. Simultaneous amplicon sequencing to explore co-occurrence patterns of bacterial, archaeal and eukaryotic microorganisms in rumen microbial communities. PLoS ONE 8, e47879. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0047879) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Apprill A, McNally S, Parsons R, Weber L. 2015. Minor revision to V4 region SSU rRNA 806R gene primer greatly increases detection of SAR11 bacterioplankton. Aquatic Microbial Ecol. 75, 129-137. ( 10.3354/ame01753) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parada AE, Needham DM, Fuhrman JA. 2016. Every base matters: assessing small subunit rRNA primers for marine microbiomes with mock communities, time series and global field samples. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 1403-1414. ( 10.1111/1462-2920.13023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, Fierer N, Knight R. 2011. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4516-4522. ( 10.1073/pnas.1000080107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu L, et al. 2019. Global diversity and biogeography of bacterial communities in wastewater treatment plants. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1183-1195. ( 10.1038/s41564-019-0426-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ju F, Zhang T. 2015. Experimental design and bioinformatics analysis for the application of metagenomics in environmental sciences and biotechnology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 12 628-12 640. ( 10.1021/acs.est.5b03719) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaumeil P-A, Mussig AJ, Hugenholtz P, Parks DH. 2020. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics 36, 1925-1927. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz848) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson JS, et al. 2019. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 5029. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-13036-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ju F, Zhang T. 2014. Novel microbial populations in ambient and mesophilic biogas-producing and phenol-degrading consortia unraveled by high-throughput sequencing. Microb. Ecol. 68, 235-246. ( 10.1007/s00248-014-0405-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quince C, Lanzen A, Davenport RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. 2011. Removing noise from pyrosequenced amplicons. BMC Bioinf. 12, 38. ( 10.1186/1471-2105-12-38) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dove SG, Kline DI, Pantos O, Angly FE, Tyson GW, Hoegh-Guldberg O. 2013. Future reef decalcification under a business-as-usual CO2 emission scenario. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15 342-15 347. ( 10.1073/pnas.1302701110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. 2016. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581-583. ( 10.1038/Nmeth.3869) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carrión VJ, et al. 2019. Pathogen-induced activation of disease-suppressive functions in the endophytic root microbiome. Science 366, 606-612. ( 10.1126/science.aaw9285) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rognes T, Flouri T, Nichols B, Quince C, Mahe F. 2016. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. Peerj 4, e2584. ( 10.7717/peerj.2584) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.R Core Team. 2013. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. See https://www.r-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Team R. 2015. RStudio: integrated development for R, vol. 42, p. 84. Boston, MA: RStudio, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CJ, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He YH, Xia R. 2020. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Molec. Plant 13, 1194-1202. ( 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piterina AV, Pembroke JT. 2013. Use of PCR-DGGE based molecular methods to analyse microbial community diversity and stability during the thermophilic stages of an ATAD wastewater sludge treatment process as an aid to performance monitoring. ISRN Biotechnol. 2013, 1-13. ( 10.5402/2013/162645) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pitta DW, Parmar N, Patel AK, Indugu N, Kumar S, Prajapathi KB, Patel AB, Reddy B, Joshi C. 2014. Bacterial diversity dynamics associated with different diets and different primer pairs in the rumen of Kankrej cattle. PLoS ONE 9, e111710. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0111710) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerritsen J, Hornung B, Ritari J, Paulin L, Rijkers GT, Schaap PJ, de Vos WM, Smidt H. 2019. A comparative and functional genomics analysis of the genus Romboutsia provides insight into adaptation to an intestinal lifestyle. BioRxiv. ( 10.1101/845511) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang XZ, Wang P, Meng XY, Ren LH. 2022. Performance and metagenomics analysis of anaerobic digestion of food waste with adding biochar supported nano zero-valent iron under mesophilic and thermophilic condition. Sci. Total Environ. 820, 153244. ( 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153244) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan TG, Bian SW, Ko JH, Liu JG, Shi XY, Xu QY. 2020. Exploring the roles of zero-valent iron in two-stage food waste anaerobic digestion. Waste Manag. 107, 91-100. ( 10.1016/j.wasman.2020.04.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu ZT, Morrison M. 2004. Comparisons of different hypervariable regions of RRS genes for use in fingerprinting of microbial communities by PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 4800-4806. ( 10.1128/Aem.70.8.4800-4806.2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Youssef N, Sheik CS, Krumholz LR, Najar FZ, Roe BA, Elshahed MS. 2009. Comparison of species richness estimates obtained using nearly complete fragments and simulated pyrosequencing-generated fragments in 16S rRNA gene-based environmental surveys. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 5227-5236. ( 10.1128/Aem.00592-09) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tu QC, Lin L, Cheng L, Deng Y, He ZL. 2019. NCycDB: a curated integrative database for fast and accurate metagenomic profiling of nitrogen cycling genes. Bioinformatics 35, 1040-1048. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty741) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin L, Ju F. 2023. Evaluation of different 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions and reference databases for profiling engineered microbiota structure and functional guilds in a swine wastewater treatment plant. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6662197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Lin L, Ju F. 2023. Evaluation of different 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions and reference databases for profiling engineered microbiota structure and functional guilds in a swine wastewater treatment plant. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6662197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

Standard code for the reported R packages was used; any modifications are indicated in the Methods section. All raw sequence data of 16S rRNA gene amplicons and metagenomic sequencing generated in this study have been uploaded to China National GeneBank (CNGB) under the project accession number CNP0004305.

The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [44].