Abstract

Genetic and biochemical studies have shown that DNA polymerase δ (Polδ) is the major replicative Pol in the eukaryotic cell. Its functional form is the holoenzyme composed of Polδ, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and replication factor C (RF-C). In this paper, we describe an N-terminal truncated form of DNA polymerase δ (ΔN Polδ) from calf thymus. The ΔN Polδ was stimulated as the full-length Polδ by PCNA in a RF-C-independent Polδ assay. However, when tested for holoenzyme function in a RF-C-dependent Polδ assay in the presence of RF-C, ATP and replication protein A (RP-A), the ΔN Polδ behaved differently. First, the ΔN Polδ lacked holoenzyme functions to a great extent. Second, product size analysis and kinetic experiments showed that the holoenzyme containing ΔN Polδ was much less efficient and synthesized DNA at a much slower rate than the holoenzyme containing full-length Polδ. The present study provides the first evidence that the N-terminal part of the large subunit of Polδ is involved in holoenzyme function.

INTRODUCTION

DNA replication requires the finely tuned action of many enzymes, proteins and cofactors. In eukaryotic cells, eight DNA polymerases called α, β, γ, δ, ɛ, θ, ζ and η have been identified (1). Three of them [namely polymerase (Pol)α, Polδ and Polɛ] are essential for DNA replication. Polα contains primase activity and is responsible for initiation of DNA synthesis on both the leading and lagging strands; Polδ and Polɛ seem to be involved in elongation of the DNA primers synthesized by Polα on the leading and lagging strand, respectively (2,3). Genetic and biochemical studies have shown that Polδ is the major replicative Pol in the eukaryotic cell. In addition to DNA replication, Polδ has been implicated in many other DNA transactions, such as nucleotide excision repair, mismatch repair and recombinational repair (reviewed in 4). More recently, Polδ has also been identified in base excision repair as a back-up enzyme (5).

Polδ has been purified from mammalian cells, including fetal calf thymus tissue, as a heterodimer with a catalytic subunit of 125 kDa and a second subunit of 48 kDa (6). Both the polymerase and the 3′→5′ exonuclease activities are located on the large p125 subunit. The precise function of the small subunit is still unknown. It has been shown that the 48 kDa subunit is required for efficient stimulation of Polδ by the sliding clamp proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (7–9). In addition to PCNA, at least two other accessory proteins are required at the replication fork: replication factor C (RF-C) and replication protein A (RP-A). RF-C, also called the clamp loader, recognizes DNA and utilizes ATP hydrolysis to assemble the PCNA clamp around the DNA. The two auxiliary proteins RF-C and PCNA form a complex that is able to track along the DNA strand as a moving platform until it encounters a 3′-OH primer template junction (10). This moving platform then recruits and tethers Polδ to the DNA. The complex between Polδ, PCNA and RF-C forms the Polδ holoenzyme (11).

How these proteins interact and whether RF-C remains a part of this complex in the elongation process is still not known. Deletion mutants of Polδ that selectively abolish interactions of Polδ with PCNA or RF-C would help to clarify this issue. Unfortunately, these mutants are not presently available due to the apparent difficulty in obtaining recombinant fully active Polδ overexpressed from either bacteria (7) or baculovirus-infected insect cells (12). A major problem might be that Polδ appears to be more complex than anticipated so far, since a third subunit has recently been identified in human cells (13).

In this paper we describe an N-terminal truncated form of Polδ (ΔN Polδ) that does not share the same characteristics as full-length Polδ. ΔN Polδ is as much stimulated as the full-length Polδ by PCNA in a RF-C-independent Polδ assay but not in a RF-C-dependent holoenzyme assay. The product size analysis and kinetic experiments with the holoenzyme complex showed that the holoenzyme containing ΔN Polδ was much less efficient and synthesized DNA at a much slower rate than the holoenzyme containing full-length Polδ. Our data indicate that the N-terminal part of Polδ large subunit is important for holoenzyme function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enzymes and proteins

RF-C was isolated as described (14). Human PCNA was purified to homogeneity as described (15). Recombinant human RP-A was purified according to Henricksen et al. (16) and Escherichia coli single-strand DNA-binding protein (SSB) according to Lohman et al. (17). Polyclonal antibodies against the exonuclease box and against the C-terminal domain of mouse Polδ were prepared as described in Cullmann et al. (18) and Hindges and Hübscher (7), respectively. Rabbit antisera against two different peptides in the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of the large subunit were gifts from P. Fischer and K. Downey (19).

Buffers

The following buffers were used: buffer A, [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 250 mM d-(+)-sucrose, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaHSO3, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), 1 µg/ml aprotinin, 1 µg/ml leupeptin, 1 µg/ml antipain, 1 µg/ml chymostatin]; buffer B, [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaHSO3, 1 mM PMSF]; buffer C-50, [50 mM KPO4 pH 7.5, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF]; buffer C-500, [500 mM KPO4 pH 7.5, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF]; buffer D, [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 mg/l leupeptin]. Salt concentrations (as NaCl) are indicated by a suffix, e.g. buffer B100 = buffer B + 100 mM NaCl.

Polδ purification

All steps were carried out at 0–4°C.

Crude extract. To 880 g of fetal calf thymus was added 1.5 l of buffer A. The tissue was thawed and homogenized in a Sorvall Omnimixer. After centrifugation of the homogenate at 10 000 g for 20 min, the supernatant was filtered through four layers of cheesecloth.

Phosphocellulose P11 chromatography. The crude extract was adsorbed in batch for 1 h on P11 resin (100 ml column) equilibrated in B100 buffer. The resin was packed onto a column washed with 3 volumes of B100. The polymerase activity was eluted with 3 volumes of a linear gradient from B100 to B800. Under these conditions, the PCNA-dependent polymerase activity was identified in the wash.

Q-Sepharose chromatography. The P11 wash was loaded on a 40 ml Q-Sepharose resin equilibrated in B100 buffer. The column was washed with 5 volumes of B100. Elution was performed with 10 volumes of a linear gradient from B100 to B800. The Polδ activity eluted at the very beginning of the gradient, at around B110 (Q-Seph. pool).

Ceramic Hydroxyapatite cHAP chromatography. The Q-Seph. pool was loaded onto a ceramic hydroxyapatite (12 ml column) pre-equilibrated with B100 buffer. The column was washed with 6 volumes of C-50 and proteins were eluted with a 10 column volumes gradient from C-50 to C-500. Fractions with an activity strongly dependent on PCNA were pooled (HAP pool) and dialyzed against buffer D100.

MonoQ FPLC column. For concentration, the HAP pool was injected onto a 1 ml MonoQ column (Pharmacia), which was then washed with 4 volumes of buffer B100 and eluted with a 5 column volumes gradient from 100 to 800 mM NaCl. The active Polδ fractions were pooled and stored in 20 µl aliquots in liquid nitrogen until use.

Enzymatic assays

RF-C-independent Polδ assay. The stimulation of Polδ by PCNA was assayed in a final volume of 25 µl containing 50 mM Bis–Tris pH 6.5, 1 mM DTT, 0.25 mg/ml BSA, 6 mM MgCl2, 20 µM [3H]dTTP (300 c.p.m./pmol), 0.5 µg poly(dA)/oligo(dT)16 base ratio 10:1, and variable amounts of Polδ and PCNA. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and then stopped with 10% trichloracetic acid. Acid-insoluble radioactivity was quantified as described (20). One unit of polymerase activity corresponds to the incorporation of 1 nmol dTMP into acid-precipitable material in 60 min at 37°C in the assay described above.

Km determination for the 3′-OH terminus. The reactions were carried out with the RF-C-independent Polδ assay as described above using 100 ng PCNA, 0.1 U Polδ (either full-length or ΔN Polδ) and varying amounts of template poly(dA)/oligo(dT) (0.06, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 µM).

RF-C-dependent Polδ holoenzyme assay. The assays were carried out as described (21) in the presence of 500 ng RP-A, 100 ng PCNA, 0.017 U RF-C and variable amounts of full-length or ΔN Polδ. One unit of RF-C allows the incorporation of 1 nmol dNMP into acid-precipitable material in 60 min at 37°C in standard holoenzyme assay conditions.

Product analysis in the RF-C-dependent holoenzyme assay. The assays were carried out as described (22). A mix of 800 ng RP-A, 100 ng PCNA, 0.017 U RF-C and variable amounts of full-length or ΔN Polδ were incubated at 37°C for 30 min.

RESULTS

Purification of a truncated form of Polδ from fetal calf thymus

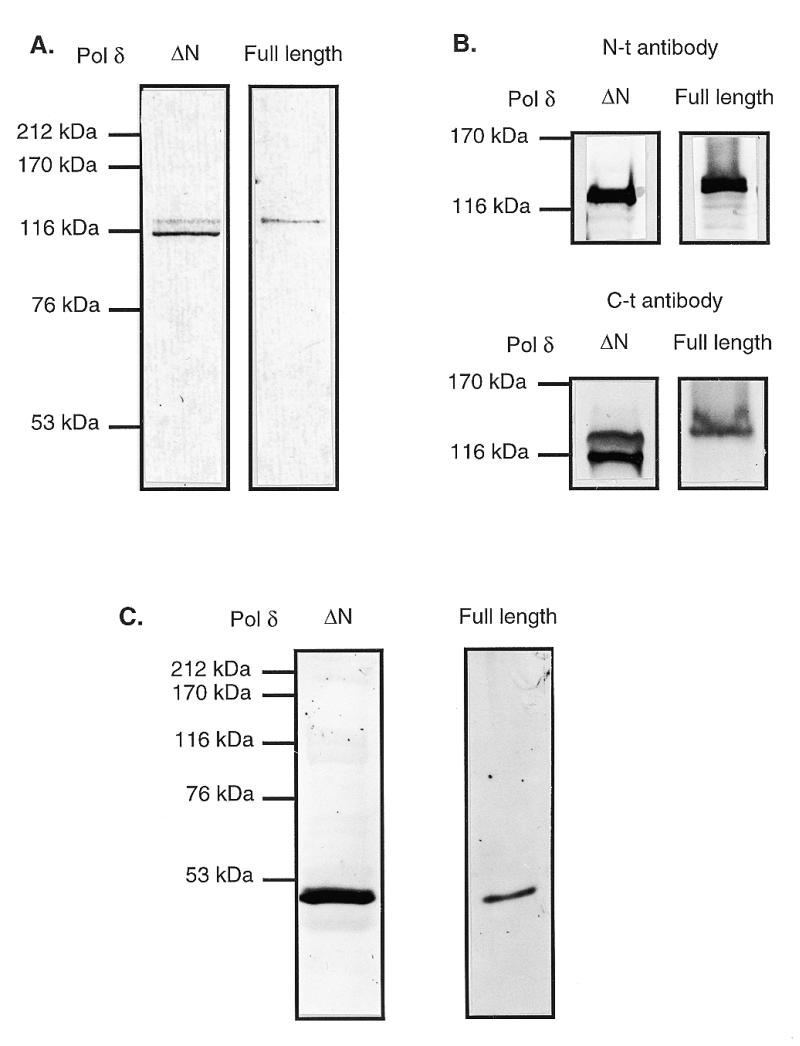

Polδ from calf thymus was purified through four consecutive chromatographic steps (see Materials and Methods). During purification, a form of Polδ was observed that bound unusually weakly to columns, e.g. eluting in the wash or at the very beginning of a gradient. Nevertheless, after the three chromatographic steps, Phosphocellulose, Q-Sepharose and Hydroxyapatite, this Polδ was separated from Polα and from Polɛ (data not shown). At this stage, Polδ required the addition of PCNA whereas Polɛ was PCNA-independent (23). Since PCNA can stimulate Polδ on a linear poly(dA)/oligo(dT) template in the absence of RF-C, the activity detected by this assay is referred to as RF-C-independent polymerase activity. After concentration on a MonoQ column, the active fractions containing only Polδ were pooled. These fractions were characterized further by immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies against the small p50 subunit (Fig. 1C) and two different polyclonal antibodies against the large subunit of Polδ: one against the C-terminal region (Fig. 1A) and the other against a region comprising the exo box (7,18). As a positive control, we used a full-length Polδ purified from calf thymus (23). The data in Figure 1A show that >90% of the large subunit of the unusual Polδ has an apparent molecular weight of 116 kDa, compared with 125 kDa for full-length Polδ. In order to see which part, N- or C-terminal, was missing, immunoblots were performed with rabbit antisera against two different peptides: KRRPGPGGVPPKRARC in the N-terminal region and CDQEQLLRRFGPPGP in the C-terminal region of the large subunit (19). The data in Figure 1B show that the antibody specific for the C-terminal part recognized both full-length and truncated Polδ and the antibody specific for the N-terminal part recognized only full-length Polδ. We concluded then that the N-terminal part (~80 amino acids) of the large subunit was missing in this Polδ preparation, which was designated ΔN Polδ.

Figure 1.

Immunoblots of full-length Polδ and ΔN Polδ. Both DNA polymerases were denatured, separated on a 7.5 (A and B) or 10% (C) SDS–polyacrylamide gel and transferred to an Immobilon-P nylon membrane by electroblotting with a Bio-Rad Trans blot apparatus, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The membrane was blocked with a 5% (w/v) solution of milk powder containing 1 mg/ml BSA. (A and B) The blots were probed with a 1:1000 dilution of either the polyclonal rabbit antibodies raised against the C-terminal domain of the large subunit (A) or with rabbit antisera against two different peptides: KRRPGPGGVPPKRARC in the N-terminal region and CDQEQLLRRFGPPGP in the C-terminal region of the large subunit as indicated (19) (B). (C) The blot was probed with a 1:1000 dilution of the monoclonal rat antibody raised against the small subunit. Cross reactivity of antibody to proteins was detected using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies with NBT and BCIP as chromogenic substrates as described (48). Lines to the left of the panel indicate standard marker proteins.

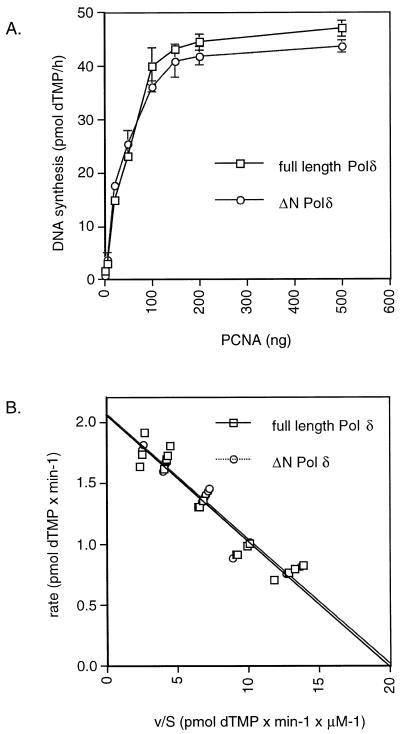

Full-length and ΔN Polδ are stimulated by PCNA in a RF-C-independent Polδ assay and have the same Km for 3′-OH primer termini

During purification, the activity of ΔN Polδ was monitored, both in the presence and absence of PCNA, using poly(dA)/oligo(dT) as a linear DNA template. This assay does not require RF-C since under low pH conditions (e.g. pH 6.5) PCNA can slide on DNA by itself. The incorporation of [3H]dTMP by both full-length Polδ and ΔN Polδ was stimulated over 100 times by PCNA. Moreover, titration of PCNA clearly indicated that both forms of Polδ could be stimulated by PCNA in a very similar manner (Fig. 2A). Next we tested whether the missing N-terminal region was precluding the binding of ΔN Polδ to DNA. For this purpose, the affinity of both polymerases for the 3′-OH terminus was determined by measuring the kinetic constants Km and Vmax with the RF-C-independent Polδ assay mentioned above. As shown in Figure 2B, the Km and Vmax of full-length Polδ were identical to those of ΔN Polδ, being ~0.1 µM for Km and 2 pmol/min for Vmax, respectively. Thus, both Polδ forms have the same affinity for the 3′-OH primer terminus in the presence of PCNA.

Figure 2.

Full-length Polδ and ΔN Polδ are stimulated by PCNA in a RF-C-independent Polδ assay and have the same Km for 3′-OH primer termini. The same amounts of Polδ determined in a RF-C-independent Polδ assay as described in Materials and Methods were used to allow a direct comparison between full-length Polδ (squares) and ΔN Polδ (circles). (A) Stimulation of ΔN Polδ and full-length Polδ by PCNA in a RF-C-independent Polδ assay. All reactions contained 0.05 U Polδ. (B) Km determination for both forms of Polδ for the 3′-OH terminus with the RF-C-independent Polδ assay. The reaction was carried out as in (A) using 100 ng of PCNA, 0.1 U Polδ and varying amounts of template (0.06, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 µM) as described in Materials and Methods. The equations of the regression curves are: y = –0.103x + 2.053 (r = 0.955) for full-length Polδ and y = –0.102x + 2.062 (r = 0.960) for ΔN Polδ.

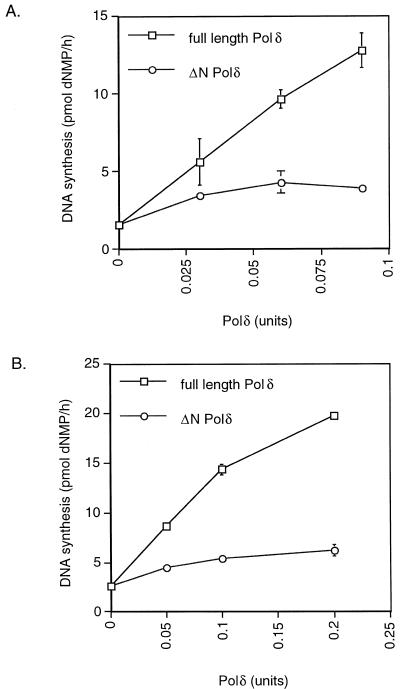

Full-length but not ΔN Polδ is active in a RF-C-dependent Polδ holoenzyme assay

When a circular singly primed template M13 DNA is used as a model template, at least two other auxiliary proteins are required: first RF-C and ATP to load PCNA onto the DNA and second RP-A, which covers the single-stranded DNA, thus preventing non-specific binding of RF-C. Interestingly, under conditions where loading of PCNA onto the DNA by RF-C is required, the activity of ΔN Polδ was only very modestly stimulated by PCNA whereas under these conditions full-length Polδ was, as expected, stimulated >10-fold (Fig. 3A). When increasing amounts of PCNA or RF-C were added, identical results were obtained (data not shown). These experiments might suggest two conclusions: there is either a factor inhibiting the activity of Polδ or the missing part of Polδ plays an important role in the interaction with RP-A and/or RF-C. The presence of a contaminating factor inhibiting the activity of ΔN Polδ was first tested by mixing increasing amounts (0–0.3 U) of ΔN Polδ to 0.15 U of full-length Polδ. No decrease in the full-length Polδ holoenzyme activity was observed even with the highest amount of ΔN Polδ added, clearly showing that there was no factor inhibiting Polδ (data not shown). A specific interaction between the N-terminal part of Polδ and RP-A was subsequently investigated by replacing RP-A with E.coli SSB. As shown in Figure 3B, the activities in the RF-C-dependent Polδ assay of both full-length and ΔN Polδ were the same when SSB was used instead of RP-A (compare Fig. 3A and B).

Figure 3.

Full-length but not ΔN Polδ is active in a RF-C-dependent Polδ holoenzyme assay. The same amounts of Polδ (as indicated) determined in a RF-C-independent Polδ assay as described in Materials and Methods were used to allow a direct comparison between full-length Polδ (squares) and ΔN Polδ (circles). The RF-C-dependent holoenzyme assay was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Full-length Polδ but not ΔN Polδ is active in a RF-C-dependent holoenzyme assay containing RP-A. (B) Full-length Polδ but not ΔN Polδ is active in a RF-C-dependent holoenzyme assay in the presence of E.coli SSB.

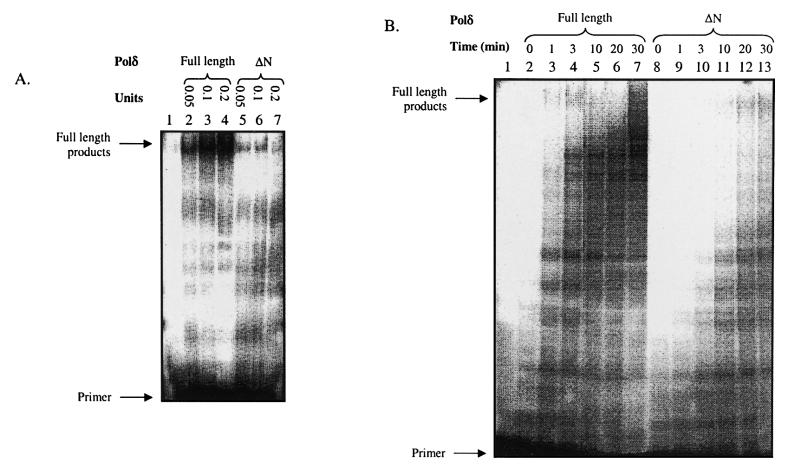

The holoenzyme containing ΔN Polδ is significantly less efficient and slower than that containing full-length Polδ

To analyze in more detail the effects of ΔN Polδ on DNA synthesis, a radioactive 5′-32P-labeled primer (40mer) was annealed to single-strand M13 DNA and replication was monitored after 30 min in the RF-C-dependent holoenzyme assay using increasing amounts of full-length and ΔN Polδ. The products were separated on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. As shown in Figure 4A, the amount of full-length products was proportional to the amount of full-length Polδ added. The holoenzyme containing ΔN Polδ, in contrast, is much less efficient in synthesizing full-length products (compare lanes 2–4 with 5–7 in Fig. 4A). Next, kinetic experiments were performed in order to compare the rate of the reaction catalyzed by ΔN Polδ with full-length Polδ (Fig. 4B). The products of DNA synthesis catalyzed by 0.2 U Polδ were analyzed at different incubation times (0, 1, 3, 10, 20 and 30 min) on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. With full-length Polδ, full-length products were synthesized within the first minute of the reaction, while ΔN Polδ synthesized full-length products only after 10 min.

Figure 4.

Product analysis with full-length Polδ and ΔN Polδ in the RF-C-dependent holoenzyme assay. The primer was first end-labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase from Biolabs and [γ-32P]dATP, then annealed to single-strand M13 DNA, and the reactions were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. The products were separated on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide/bis-acrylamide ratio 19:1). After drying the gel, the labeled products were visualized with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). (A) Titration of the full-length and ΔN Polδ. A mix of 800 ng RP-A, 100 ng PCNA, 0.017 U RF-C and variable amounts of full-length or ΔN Polδ was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Lane 1, control without Polδ; lanes 2–4, different amounts of full-length Polδ; lanes 5–7, different amounts of ΔN Polδ. (B) Kinetics of the holoenzyme assay. All reactions contained 0.017 U RF-C, 0.2 U Polδ (either full-length or ΔN), 100 ng PCNA and 800 ng RP-A for each time point. Lane 1, control without Polδ. Samples in the other lanes are different incubation times for full-length Polδ (lanes 2–7) and for ΔN Polδ (lanes 8–13).

DISCUSSION

In this paper we present the characteristics of a truncated form of Polδ from calf thymus. Immunoblot analysis with polyclonal antibodies suggested that 9 kDa (~80 amino acids) of the N-terminal part of the large subunit of Polδ were missing (Fig. 1A and B). Several cleavage sites for proteases are present around this position. For example, trypsin cleaves at position W78 and chymotrypsin at W78 and R80. A multiple sequence alignment (20 sequences) produced by the program MAXHOM (24) predicted a solvent-exposed loop conformation for the 100 amino acids at the N-terminal end of the catalytic subunit (25,26), making it accessible to proteases. Interestingly, this N-terminal part of the large subunit is less conserved among species and is completely absent from the polymerases from Chlorella virus and from Archaea, which start at position 99 and 123, respectively. We took advantage of this ΔN Polδ to investigate its properties compared with those of the full-length Polδ previously purified from the same tissue, using two different assays: the RF-C-independent and the RF-C-dependent Polδ assays.

When DNA synthesis was measured with the RF-C-independent Polδ assay (Fig. 2), both forms of Polδ were equally active, suggesting that the 80 amino acids at the N-terminus do not function in catalysis per se. These results are in agreement with other studies showing that deletion mutants at the N-terminus (amino acids 2–249) retain polymerase activity, but deletion of the C-terminal part of the large subunit abolished all polymerase activity (27). This C-terminal domain is thought to be responsible for DNA interaction, as shown by photocrosslinking performed together with immunoblot analysis (28). The truncated Polδ, which contains the intact C-terminal region of the catalytic subunit, has the same affinity for DNA as full-length Polδ (Fig. 2B). When ΔN Polδ was tested for stimulation by PCNA, a similar behavior to the full-length Polδ was observed (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the N-terminal domain is not involved in the interaction with PCNA. Studies with model peptides derived from the catalytic subunit of Polδ indicated the presence of a variant of the PCNA-binding motif (residues 142 to 149) still present in ΔN Polδ (29–31). However, this domain does not per se appear to be functional, since DNA synthesis by the catalytic subunit of mammalian Polδ is not stimulated by PCNA. The two-subunit form of Polδ (p125·p48) is required for stimulation by PCNA (7,12,32–34). Confirming these results, immunoblot analysis with monoclonal antibodies showed that the small p50 subunit in ΔN Polδ was intact and present at expected levels (Fig. 1C). At present, it is not clear whether PCNA directly interacts with the small p50 subunit or whether the binding of p50 to the p125 subunit leads to a conformational change that increases the interaction of the catalytic subunit with PCNA. Recently, a more complex form of Polδ has been isolated from Schizosaccharomyces pombe, with at least four, and possibly even five, subunits (35), and from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (36,37) and human (13), with three subunits. Although the sequence similarity between the three subunits Pol32p (S.cerevisiae), Cdc27 (S.pombe) and p66 (human) is very low, the presence of a PCNA-binding motif (22) in each of these subunits suggests that these three proteins are functional homologs involved in the interaction with PCNA.

When the two Polδ forms were tested under conditions where PCNA cannot assemble around DNA by itself, but must be loaded onto DNA by the clamp loader RF-C, ΔN Polδ and full-length Polδ behaved differently (Figs 3 and 4). The mechanism by which RF-C enables Polδ to use primed circular DNA as a template in vitro has been studied in detail (11,38–41). Our results showed that when RF-C is required, the activity of ΔN Polδ is only moderately stimulated by PCNA, in contrast to full-length Polδ (Fig. 3). This moderate stimulation could be due to the residual amounts of full-length large subunit (see Fig. 1A). Furthermore, we showed that the holoenzyme containing ΔN Polδ was significantly less efficient and slower than that containing full-length Polδ (Fig. 4), suggesting that the N-terminal part of Polδ is involved in the interaction with another protein. Three proteins could be candidates for such an interaction: PCNA, RP-A and RF-C. First, an interaction between the N-terminal part of Polδ and PCNA is very unlikely, since both forms of Polδ are similarly stimulated by PCNA on a poly(dA)/oligo(dT) template. Second, a specific interaction between the N-terminal part of Polδ and RP-A was investigated using E.coli SSB: the polymerase activities in the RF-C-dependent Polδ assay of both full-length and ΔN Polδ were the same when SSB was used instead of RP-A (compare Fig. 3A and B). Consequently, the fact that ΔN Polδ could be only moderately stimulated by PCNA in the RF-C-dependent holoenzyme assay was not due to loss of a specific interaction between the N-terminal part of Polδ and RP-A. However, it does not eliminate the possibility that ΔN Polδ is no longer able to interact with both E.coli and human SSB. The fact that Polδ has been shown to interact directly with the p70 subunit of RP-A favors this hypothesis (42). The third possibility is that the N-terminal part of the large subunit of Polδ might interact with RF-C. This conclusion is supported by the previous isolation of a multiprotein complex active in DNA replication containing at least Polα, Polδ and RF-C from calf thymus (21) and human cells (43), suggesting a direct interaction between Polδ and RF-C. Furthermore, Polδ has been shown to interact directly with RF-C (42), consistent with interaction between Polδ and the p40 subunit of RF-C (13,44). The role of RF-C in the holoenzyme complex (beyond its role of loading PCNA) seems to be dependent on the presence of RP-A, via interactions between three RF-C subunits (p140, p40 and p38) and the p70 subunit of RP-A, as RF-C does not remain in the holoenzyme if E.coli SSB is substituted for RP-A (45) but is not released from RP-A-coated DNA (42,46). This report shows that the N-terminal part of the large subunit of Polδ is important for holoenzyme function, probably through its interaction with RF-C and/or RP-A. Such an interaction could play a role in stabilization of the Polδ holoenzyme (Polδ, RF-C and PCNA) at the mammalian DNA replication fork. Recently, evidence that Polδ can be mutated in human colon cancer cells, particularly those having no mismatch repair defects, has been presented (47). Six of 19 mutations were localized in the first 119 amino acids of the N-terminal part of the Polδ large subunit, underlining the important role played by this region that we propose interacts with RF-C and/or RP-A.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Aengus Mac Sweeney and Zophonías O. Jónsson for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Paul Fischer and Kathleen Downey for providing the antisera against the the N- and C-terminal parts of Polδ and Alexander Yuzhakov for a copy of his manuscript in press. This work was supported by the UBS, ‘im Aufrag eines Kunden’ to S.B., by the Swiss Cancer League (grant KFS 164-9-1995) to M.S. and by the Kanton of Zürich.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bridges B.A. (1999) Curr. Biol., 9, R475–R477. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navas T.A., Zhou,Z. and Elledge,S.J. (1995) Cell, 80, 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zlotkin T., Kaufmann,G., Jiang,Y., Lee,M.Y.W.T., Uitto,L., Syväoja,J., Dornreiter,I., Fanning,E. and Nethanel,T. (1996) EMBO J., 15, 2298–2305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hindges R. and Hübscher,U. (1997) Biol. Chem., 378, 345–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stucki M., Pascucci,B., Parlanti,E., Fortini,P., Wilson,S.H., Hubscher,U. and Dogliotti,E. (1998) Oncogene, 17, 835–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee M.Y.W.T., Tan,C.K., Downey,K.M. and So,A.G. (1984) Biochemistry, 23, 1906–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hindges R. and Hübscher,U. (1995) Gene, 158, 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J.Q., He,H., Tan,C.K., Downey,K.M. and So,A.G. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 1094–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Y., Jiang,Y., Zhang,P., Zhang,S.-J., Zhou,Y., Li,B.Q., Toomey,N.L. and Lee,M.Y.W.T. (1997) J. Biol. Chem., 272, 13013–13018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Podust V.N., Podust,L.M., Goubin,F., Ducommun,B. and Hübscher,U. (1995) Biochemistry, 34, 8869–8875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Podust V.N., Georgaki,A., Strack,B. and Hübscher,U. (1992) Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 4159–4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou J., Tan,C.K., So,A.G. and Downey,K.M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem., 271, 29740–29745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes P., Tratner,I., Ducoux,M., Piard,K. and Baldacci,G. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 2108–2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hübscher U., Mossi,R., Ferrari,E., Stucki,M. and Jónsson,Z.O. (1999) In Cotterill,S. (ed.), Eukaryotic DNA Replication: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp. 119–137.

- 15.Schurtenberger P., Egelhaaf,S.U., Hindges,R., Maga,G., Jónsson,Z.O., May,R.P., Glatter,O. and Hübscher,U. (1998) J. Mol. Biol., 275, 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henricksen L.A., Umbricht,C.B. and Wold,M.S. (1994) J. Biol. Chem., 269, 11121–11132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohman T.M., Green,J.M. and Beyer,R.S. (1986) Biochemistry, 25, 21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cullmann G., Hindges,R., Berchtold,M.W. and Hübscher,U. (1993) Gene, 134, 191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McConnell M., Miller,H., Mozzherin,D.J., Quamina,A., Tan,C.-K., Downey,K.M. and Fisher,P.A. (1996) Biochemistry, 35, 8268–8274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hübscher U. and Kornberg,A. (1979) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 76, 6284–6288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maga G. and Hübscher,U. (1996) Biochemistry, 35, 5764–5777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jónsson Z.O., Hindges,R. and Hübscher,U. (1998) EMBO J., 17, 2412–2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiser T., Gassmann,M., Thömmes,P., Ferrari,E., Hafkemeyer,P. and Hübscher,U. (1991) J. Biol. Chem., 266, 10420–10428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sander C. and Schneider,R. (1991) Protein, 9, 56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rost B. and Sander,C. (1993) J. Mol. Biol., 232, 584–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rost B. and Sander,C. (1994) Proteins, 19, 55–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu S.-M., Zhang,P., Zeng,X.R., Zhang,S.-J., Mo,J., Li,B.Q. and Lee,M.Y.W.T. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., 273, 9561–9569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mozzherin D.J., Tan,C.-K., Downey,K.M. and Fisher,P.A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem., 274, 19862–19867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang P., Frugulhetti,I., Jiang,Y., Holt,G.L., Condit,R.C. and Lee,M.Y. (1995) J. Biol. Chem., 270, 7993–7998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang S.J., Zeng,X.R., Zhang,P., Toomey,N.L., Chuang,R.Y., Chang,L.S. and Lee,M.Y. (1995) J. Biol. Chem., 270, 7988–7992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang P., Mo,J.-Y., Perez,A., Leon,A., Liu,L., Mazloum,N., Xu,H. and Lee,M.Y.W.T. (1999) J. Biol. Chem., 274, 26647–26653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goulian M., Herrmann,S.M., Sackett,J.W. and Grimm,S.L. (1990) J. Biol. Chem., 265, 16402–16411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiang C.S. and Lehmann,I.R. (1995) Gene, 166, 237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arroyo M.P., Downey,K.M., So,A.G. and Wang,T.-S.F. (1996) J. Biol. Chem., 271, 15971–15980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuo S., Gibbs,E., Kelman,Z., Wang,T.S.F., O’Donnell,M., MacNeill,S.A. and Hurwitz,J. (1997) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 11244–11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerik K.J., Li,X., Pautz,A. and Burgers,P.M.J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., 273, 19747–19755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burgers P.M.J. and Gerik,K.J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., 273, 19756–19762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee S.-H. and Hurwitz,J. (1990) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 5672–5676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burgers P.M.J. (1991) J. Biol. Chem., 266, 22698–22706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsurimoto T. and Stillman,B. (1991) J. Biol. Chem., 266, 1950–1960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee S.H., Kwong,A.D., Pan,Z.Q. and Hurwitz,J. (1991) J. Biol. Chem., 266, 594–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuzhakov A., Kelman,Z., Hurwitz,J. and O’Donnell,M. (1999) EMBO J., 18, 6189–6199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Applegren N., Hickey,R.J., Kleinschmidt,A.M., Zhou,Q., Coll,J., Wills,P., Swaby,R., Wei,Y., Quan,J.Y., Lee,M.Y.W.T. and Malkas,L.H. (1995) J. Cell. Biochem., 59, 91–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pan Z.Q., Chen,M. and Hurwitz,J. (1993) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Podust V.N., Tiwari,N., Stephan,S. and Fanning,E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., 273, 31992–31999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waga S. and Stillman,B. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 4177–4187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flohr T., Dai,J.-C., Büttner,J., Popanda,O., Hagmüller,E. and Thielmann,H.W. (1999) Int. J. Cancer, 80, 919–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.