Abstract

Burnout in health care has received considerable attention; widespread efforts to implement burnout reduction initiatives are underway. Healthcare providers with marginalized identities may be especially at risk. Health service psychologists are often key members of interprofessional teams and may be asked to intervene with colleagues exhibiting signs of burnout. Consequently, psychologists in these settings can then find themselves in professional quandaries. In the absence of clear guidelines, psychologists are learning to enhance their scope of practice and navigate ethical guidelines while supporting colleagues and simultaneously satisfying organizational priorities. In this paper we (a) provide an overview of burnout and its scope, (b) discuss ethical challenges health service psychologists face in addressing provider burnout, and (c) present three models to employ in healthcare provider burnout and well-being.

Keywords: Burnout, Resilience, Well-being, Healthcare, Psychologists

Clinical Vignette

Dillon (pronouns They/Them) is an early career psychologist who, after completing post-doctoral training, started a clinical faculty position in the same department of family and geriatric medicine with a residency training program. Dillon works primarily (2.5 days/week) in the family medicine clinic as a leader on the Behavioral Health Team in an integrated primary care model. Their responsibilities include direct and indirect patient care and consultation, training of medical residents, and training and supervision of psychology learners (i.e., externs, interns, and postdoctoral fellows). Two days per week, Dillon works in a collocated model within an anesthesia-based pain clinic in which they primarily conduct and supervise pre-procedure/surgical assessments and brief interventions. Many of the same medical residents and psychology learners also rotate through this clinic. One half day per week Dillon has “protected” time to devote to research and other projects serving patients, medical residents, and psychology learners.

Dillon has become a trusted and valued faculty member of the clinics in which they work. They have enjoyed a warm and positive relationship among the faculty, residents, psychology learners, and patients. Dillon has worked diligently to cultivate these relationships and skill sets to be a successful psychologist serving medical supervisors in these integrated and collaborative models of health care. When opportunities to become more involved in department-wide projects and initiatives arise, Dillon has always been quick to volunteer. It is Dillon’s hope that they will be in the department for the duration of their career.

After a spring clinic leadership meeting, the clinic medical and residency training directors asked if Dillon could meet to discuss an important initiative to support medical residents and other clinic providers. While meeting, the directors asked Dillon to help fulfill an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) accreditation directive to address burnout and well-being among (primarily) the medical residents. In addition to the accreditation requirement, the directors are interested in addressing burnout because the medical residents have seemed increasingly rundown beyond what would be considered normal. The directors also recounted a few incidents of residents’ unprofessional behavior and are worried about how overall well-being of the residents and attending providers could negatively impact the reputation of the clinics and clinical training programs. The directors felt it was vital to have a proactive program in place to support residents prior to the next cohort start date on July 1.

When Dillon asked what, specifically, this would entail, the directors said that they envision in-house psychologists providing group and individual counseling and programs for residents. The directors also offered that this work would become 10% (4 h each week) of Dillon’s position responsibilities and that it would be reflected as part of regular responsibilities in Dillon’s next contract. The directors shared that having Dillon oversee this program was a “no brainer” because the residents reported that when Dillon occasionally led Balint support groups, that specific group experience was especially useful.

The directors also mentioned that it would be helpful if when a resident was distressed or was not behaving professionally, the resident (or even one of the psychology interns or postdocs) could immediately be referred to Dillon for a few counseling sessions. The directors emphasized to Dillon that this process would be easy to track in-house (for accreditation purposes) and it would be especially convenient because residents have very little time to seek counseling elsewhere.

Although this is a great opportunity to capitalize on the trust Dillon has fostered, this proposed program has both ethical and scope-of-practice issues to consider. Part of the strain Dillon feels is that in integrated models of care, prioritizing the relationship among the medical providers—especially the directors—is vital. To succeed, such a program should be (a) clearly defined regarding expected deliverables among all stakeholders, (b) measurable, and most importantly (c) ethically implemented.

Psychologists’ Role in Addressing Healthcare Provider Burnout and Well-Being

Background

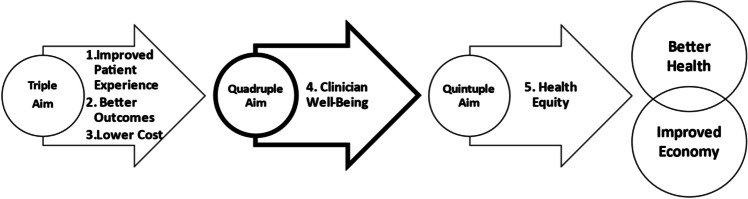

More than a decade ago, the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) introduced the “Triple Aim” for health care as an aspirational guide to improved population health (Berwick et al., 2008). The three-pointed aim is comprised of improving the health of populations while enhancing the experience of care for individuals and reducing the per capita cost of health care (https://www.ihi.org/Topics/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx). Since that time, there has been an important evolution in that original three-pointed model (see Fig. 1). Subsequent conversations highlight that achieving the Triple Aim is virtually impossible without supporting the health and well-being of the caregivers (i.e., healthcare providers). In 2014, “clinician well-being” was added to the framework as an essential fourth point resulting in the “Quadruple Aim” (Bodenheimer & Sinsky, 2014; Nundy et al., 2021).

Fig. 1.

Evolution of the Quintuple Aim. Adapted from American College of Cardiology (2021)

The area of clinician well-being has recently garnered more attention to the extent that attending to the well-being of healthcare providers has become a component of a psychologist’s job roles with increased frequency. For psychologists working in academic health centers and training affiliated positions, new and exciting opportunities have arisen. Although appealing, the models and approaches for how psychologists can successfully meet expectations while simultaneously adhering to ethical and evidence-based practices have not been delineated.

In the National Academy of Medicine (2022) National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being, the major priority areas point to many ways in which psychologist expertise can be beneficial. Psychologists’ knowledge and skills may benefit individuals, healthcare teams, and systems and policy. Herein, we present an overview of the magnitude of the problem, an example of a clinical situation commonly encountered by psychologists working in training clinics, and finally, we compare three models for addressing clinician burnout, resilience, and/or well-being in healthcare settings.

A comprehensive review of what psychologists “need to know” regarding these important issues is well beyond the scope of this paper. Rather, we hope to enhance awareness and provide a reference for psychologists to consider regarding how to approach the design and implementation of this work in healthcare organizations.

Nomenclature and Culture of Healthcare Settings

Although we frequently use the term provider to refer to healthcare clinicians, that term may not be universally accepted across healthcare cultures. We recommend that the psychologist attend carefully to the culture and nomenclature of the settings in which they serve. Much of the research and literature we have cited pertains to medical personnel (i.e., physicians). We acknowledge that this work applies to broader professional audiences. Finally, we refer here exclusively to psychologists in these roles. Much like integrated models of care, the “behavioral scientist” in such a role may also be a mental health provider from another healthcare discipline (e.g., nursing) or counseling, social work, or pastoral care.

Magnitude of the Problem

In 2022, the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office published Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce. The opening paragraph of this advisory states unequivocally that, even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, burnout among US healthcare workers had reached “crisis levels” (National Academy of Medicine, 2022; Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, 2022, p. 7).

Widespread efforts to research, understand, and effectively address burnout and well-being in the healthcare systems are underway through various organizations including the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), and National Academy of Sciences (NAS) among others. Most of the literature, research, and broad organizational initiatives are found in the medical and healthcare literature—not in the psychology literature. These initiatives have direct implications for training, professional roles, and skills of health service psychologists. Psychologists who have an interest in or who are entering into these areas of work are advised to review these key documents, initiatives, and directives, some of which we reference here. The National Academy of Medicine (2022) National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being outlines seven major priority areas with specific goals and action items. We recommend that psychologists with an interest in these roles avail themselves of this literature prior to moving forward.

The effects of provider and learner burnout are costly on several fronts. High levels of burnout have been associated with increased medical errors as well as high rates of provider absenteeism or leaving the profession altogether (Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, 2022). Turnover among primary care physicians (PCP) alone is estimated to result in approximately $979 million in excess healthcare expenditures annually; more than one fourth of that cost ($260 million) is directly related to PCP burnout (West et al., 2020).

It is estimated that among individual providers, burnout “symptoms” are reported by approximately 50% of physicians and nurses and as much as 60% of medical residents (National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019). Elevated levels of burnout have been associated with physical and mental health concerns including increased levels of anxiety (National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019), depression, suicidal ideation (Menon et al., 2020) as well as decreased cognitive function, sleep dysfunction and insomnia and substance use and misuse (National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019). Healthcare professionals experiencing high levels of burnout also cite a marked increase in interpersonal difficulties including unprofessional behavior among colleagues, patients, or peers and with family and primary relationships (National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019; Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, 2022).

Data suggest that burnout levels are even higher among healthcare profession learners (i.e., medical students, residents, and fellows) and may vary by medical or healthcare specialty area. Although base rates of psychological symptoms and suicidal ideation are appreciably higher among medical learners and physicians than the general population, there may nonetheless be a reluctance to seek support or treatment (Shanafelt, 2021; National Academy of Medicine, 2022).

Addressing the Problem

Policy and system-level initiatives to address the problem of burnout and well-being in health care have begun to be implemented. In 2016, ACGME revised its Common Program Requirements for all accredited residency and fellowship programs to address well-being more directly and comprehensively (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2016). The requirements emphasize that psychological, emotional, and physical well-being are critical in the development of the competent, caring, and resilient physician. Similarly, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2021) included in The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education domain addressing Personal, Professional, and Leadership Development that nursing graduates should be involved in activities that promote personal health, resilience, and well-being. Other healthcare discipline accreditation agencies and commissions are also following suit.

In 2021, the Health Resources and Services Administration Health and Public Safety Workforce Resiliency Training Program Funding awarded over $68 million to 34 grantees for evidence-based or evidence-informed strategies designed to “reduce and address burnout, suicide, mental health conditions and substance use disorders and promote resiliency among... the ‘Health Workforce,’ in rural and underserved communities” (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2021, “About the Program”).

Burnout Defined

Despite the proliferation of coverage of this topic in professional and popular outlets, there remains a surprising level of widespread misunderstanding of how burnout is accurately defined and, especially, how to address it. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems lists burnout as a phenomenon/syndrome (World Health Organization, 2019). It is not, however, included as a diagnosis. Rather, it is an “occupational phenomenon”—the drivers of which occur on more of a system level. Decades of research have identified that burnout manifestation within individuals is often driven by six “mismatches” in workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values between the system and persons working in the system. In an American Psychological Association podcast episode, psychologist and foremost expert in burnout research Christina Maslach, PhD, explained that “it’s really the relationship between people and their job, whether there’s a good match or fit or a mismatch, that really is problematic and raises the risk of burnout” (Mills, 2021).

Within the individual, there are three key dimensions of burnout: (1) emotional exhaustion, (2) cynicism and detachment from one’s job (also referred to as depersonalization) and (3) professional inefficacy or sense of being ineffective in one’s work. According to Leiter and Maslach (2017) the burned out profile is comprised of high emotional exhaustion, moderate-to-high cynicism, and a low sense of efficacy. If a person is showing just one of these, they are not necessarily burned out per se, but they may be headed in that direction (Mills, 2021; Leiter & Maslach, 2017).

Given the magnitude of healthcare professional burnout and the imminent need to effectively address it, involving the expertise of psychologists would seem logical and—from our perspective—even vital. Experts in this area are emphatic regarding how important it is to not confuse individual and clinical interventions as the way to address the problem of burnout in individual healthcare learners and personnel who are working in especially challenging systems (Dyrbye et al., 2017; Shanafelt et al., 2020). This sentiment is underscored by Christine Sinsky, MD, who said, “The very high rates of physician burnout are not related to a deficiency of resilience within physicians” (Berg, 2020).

Due in large part to the ways in which we are trained, psychologists may be inclined to approach assessment and intervention from the standpoint of individual clinical symptomatology and psychopathology. Psychologists may intuitively conceptualize individual manifestations of burnout as a diagnosis or symptoms to be treated. Dr. Maslach noted:

[Burnout] can be a step in the path towards other kinds of problems, like depression or anxiety, but it is a mistake, I think—and the World Health Organization agrees on that point and says that it's not a medical diagnosis. So it's not something that should be treated in that way. And it is not identified within the DSM, for example, because it's more a human condition or response to stressors. (Mills, 2021).

Burnout in Underrepresented, Marginalized, and Vulnerable Groups

While occupational burnout reflects system-level issues (Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, 2022), it is also influenced by individual factors. Burnout and subjective well-being in providers and learners with marginalized identities (i.e., race, ethnicity, sexual orientation) who are also underrepresented in medicine (URiM) are poorly understood and require further assessment.

Sexual and Gender Identities

Identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, queer/questioning, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQ +) has been associated with higher rates of workplace burnout in medicine (Afonso et al., 2021). LGBTQ + medical students report more distress and worse health (Przedworski et al., 2015) compared to their heterosexual peers. Further, LGBTQ + identifying medical students reported experiencing discrimination and mistreatment due to sexual orientation (West et al., 2016). LGBTQ + status has been associated with burnout (Serafini et al., 2020; Smith et al. 2022). Those with marginalized sexual and gender identities may not disclose their identity due to stigma and sociopolitical environment, and thus not receive potential support from family and coworkers. Furthermore, members of this community may have insufficient workplace protection from mistreatment, which could put these individuals at an increased risk for burnout. Medical students are increasingly identifying as LGBTQ + (Przedworski et al., 2015), which will result in a more diverse workforce in medicine. This shift underscores the urgency to implement systems and policy level changes as well as provide individual support to increase well-being and buffer the effects of burnout in these marginalized populations.

Women

Data on potential gender-specific burnout drivers are mixed. Women appear to face greater challenges regarding balancing work and family responsibilities as they are primarily responsible for childrearing and, in some cases, caretaking for aging family members. This stress can lead to appreciable levels of role strain (Robinson, 2003). Women physicians consistently make less money (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020) and advance slower than their male peers (Diamond et al., 2016), yet generally report satisfaction in the workplace (Rizvi et al., 2012). Despite being at least as satisfied in their work as their male counterparts, women physicians self-reported high rates of burnout both pre- (McMurray et al., 2000) and post-COVID (The Physicians Foundation, 2021). In other studies, no sex differences in burnout were detected (Shanafelt et al., 2019). Perceived lack of support at home has been associated with both a high risk for burnout and burnout syndrome (Afonso et al., 2021); conversely, having a supportive spouse or colleague buffered the effects of burnout (McMurray et al., 2000). Although the numbers of women practicing medicine are increasing, system-level interventions to support women experiencing role strain are lacking. For a recent, thoughtful discussion of burnout, engagement, and common gender-specific stressors experienced by women in medicine, please see Sullivan et al. (2023).

Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Groups

Surprisingly, some studies report little to no difference in burnout based on racial or ethnic identity. Whereas Smith et al. (2022) reported higher rates of burnout for family medicine residents who self-identify as persons of color (POC), Garcia et al. (2020) found burnout rates to be highest in those identifying as non-Hispanic Whites. Anesthesiologists with English as their second language as well as non-US medical graduates reported lower rates of burnout (Afonso et al., 2021; West et al., 2011). These findings are indeed puzzling. In one recent study, Serafini et al. (2020) documented the experiences of racism in the workplace, and although racism wasn’t specifically tied to burnout, racially and ethnically underrepresented physicians reported experiencing, and being upset by, racism perpetrated by patients, colleagues, and organizations where they were employed. Both data and the lived experience of those who are racially/ethnically URiM support the reality of systemic oppression.

It stands to reason that healthcare professionals belonging to vulnerable groups might experience more burnout and lower subjective well-being than those with majority status, yet studies are inconclusive, potentially due to measurement (Rotenstein et al., 2018) or reporting issues. Perhaps those URiM may be more likely to report overt discrimination (i.e., racism, sexism) because it is acknowledged as a systemic issue, whereas burnout continues to be erroneously conceptualized as an individual problem. Furthermore, underrepresented racial and ethnic groups may be less likely to disclose distress due to social stigma associated with help-seeking behavior (Memon et al., 2016); it is possible this extends to burnout-related distress. It is also possible that vulnerable groups are more resilient or experience burnout in ways not currently captured by standardized instruments (Afonso et al., 2021). Careful studies are needed to elucidate the experience of those URiM, especially those with intersecting marginalized identities, to better support the well-being and retention of a diverse work force.

Ethical Considerations

In each of the three models presented herein, ethical dilemmas should be anticipated and will likely be commonplace (see Table 1 for a model-specific listing of applicable APA and Interprofessional Education Collaborative [IPEC] ethical codes/principles). This emerging area of burnout interventions offers exciting opportunity replete with ethical challenges that are often uncharted. We refer the reader to the 8-step model for resolving ethical challenges in primary care (Kanzler et al., 2013) as an exemplar.

Table 1.

Ethical Codes to Consider in Interprofessional Burnout/Wellness Interventions

| Domain | Potentially Relevant Ethical Principles, Codes of Conduct and Values Related to Interprofessional Competency | Potential Risk Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||

| Multiple Roles |

APA 3.05: Multiple Relationships APA 3.07: Third-Party Requests for Services APA 3.11: Psychological Services Delivered to or Through Organizations APA 7.04: Student Disclosure of Personal Information APA 7.05: Mandatory Individual or Group Therapy APA 7.06: Assessing Student and Supervisee Performance IPEC VE4: Respect the unique cultures, values, roles/responsibilities, and expertise of other health professions |

High | High | High |

| Scope of Practice/Competence |

APA 2.01: Boundaries of Competence APA 2.02: Providing Services in Emergencies IPEC VE10: Maintain competence in one’s own profession appropriate to scope of practice |

Low/Moderate | High | High |

| Confidentiality |

APA 4.01: Maintaining Confidentiality APA 4.04: Minimizing Intrusions on Privacy APA 4.05: Disclosures APA 4.06: Consultations IPEC VE2: Respect the dignity and privacy of patients while maintaining confidentiality in the delivery of team-based care |

High | Moderate | Low |

| Conflict of Interest | APA 3.06: Conflict of Interest | High | Low | High |

| Professionalism |

APA 6.01: Documentation of Professional and Scientific Work and Maintenance of Records APA 6.05: Barter with Clients/Patients APA 6.06: Accuracy in Reports to Payors and Funding Sources IPEC Values and Ethics Competencies: Work with individuals of other professions to maintain a climate of mutual respect and shared values |

High | High | Low |

Model 1: Individual Treatment/Counseling/Consultation

Health service psychologists working within this model find themselves at high risk for encountering ethical conundrums (see Table 1). Psychologists may be asked to assume multiple roles when working on interprofessional teams. Like Dillon, those who earn the respect of their colleagues and administrators may be tasked with addressing burnout-related distress in medical colleagues. When considering practice culture unique to interprofessional settings, being asked to assist is a vote of confidence in the psychologist’s ability. However, this should raise significant ethical concerns.

Multiple issues of confidentiality regarding documentation, disclosure, and minimizing privacy intrusions are applicable in this situation. Charting in electronic health records that are widely available within a healthcare system is problematic even when they may be stored in a protected fashion often referred to as behind the glass. Although psychologists’ expertise lends itself to individual intervention, treating a colleague (even when self-referred) is unethical. Interceding with distressed colleagues may lead to the revelation that a colleague is impaired or practicing with a diminished capacity thus putting the psychologist in an untenable bind.

The APA’s code of conduct makes no provision for identifying and monitoring impaired colleagues; as suggested by Kanzler et al. (2013), psychologists can refer to and thoughtfully consider the American Medical Association’s definition of an impaired physician. Nonetheless, this is a difficult conversation for all parties. If a psychologist is financially supported by the department for this service, it calls into question the financial arrangement for this type of service. Billing for services requires a diagnostic code, but burnout is not an individual diagnosis. Furthermore, providers without adequate knowledge of burnout may incorrectly characterize a colleague’s experience as a diagnosis to be treated. This is especially problematic when interacting with colleagues who are already vulnerable to being systemically over pathologized (i.e., LGBQT + individuals, racial/ethnic minorities). Separate—yet related—concerns arise when administrators or supervisors either recommend or require that medical providers be seen for intervention. Administrators may inappropriately ask for progress reports on a provider’s treatment or mental health; intervention requests involving students provide another layer of concern. It is of the utmost importance that psychologists carefully and critically address ethical issues as they arise while maintaining a climate of mutual respect and commitment to their interprofessional team.

Model 2: Group-Based Intervention

Given the high rates of burnout among physicians and medical residents, the traditional consultation model employed by many psychologists may be inadequate for addressing this epidemic. Group programming can better meet the needs of multiple providers at once in a supportive, collegial, and more anonymous atmosphere. While this is a better option than Model 1, ethical dilemmas are still present (see Table 1). Group interventions, like the Cultivating Personal Resilience (CPRP; Beacham et al., 2020) or Promoting Resilience in Stress Management (PRISM; Yi-Frazier et al., 2022) programs afford a natural opportunity to build community and connection, which fit nicely with IPEC’s (2016) value of creating environments that foster mutual respect. Working within this model offers a unique opportunity to further enhance interprofessional collaboration. However, those who have not given appropriate acknowledgement of the system drivers of burnout may fall short in meeting key objectives for such a program.

Some group-based intervention programs, like CPRP and PRISM, are unique because attendees can individualize their experience by engaging with the content and activities either collaboratively within the group or independently. This is especially salient for providers with marginalized identities, as they may experience burnout and resilience differently from others with whom they work. Notably, individualized group approaches provide a high level of autonomy for marginalized providers, making this a culturally sensitive intervention option.

Well-being related group interventions are often implemented to meet a training requirement and can be embedded into curriculum, raising ethical concerns about mandatory participation. Although this is convenient for program documentation, it can be met with some resistance from various constituents. We have found that offering recipients options of equivalent delivery methods, such as in-person or online modular formats, can foster greater success of these initiatives.

Model 3: System-Level Assessment and Intervention

Addressing burnout at the system level is vitally important and working from this model may pose several challenges (see Table 1). Psychologists may be asked to conduct climate surveys to assess burnout and perceived worker well-being, which requires competency in organizational assessment. Climate surveys are tremendously important and have the potential to shift organizational policy, making valid, culturally sensitive, and ethical assessment of the utmost importance. Conducting climate surveys while engaging in interprofessional clinical work requires psychologists to function in multiple roles. Those who typically enjoy close working relationships with team members may find themselves at odds with the task they are assigned. Psychologists must balance maintaining good standing with their colleagues while supporting larger organizational needs. Although responses are presented as aggregate data, medical providers may not trust the process and be concerned they could be singled out, especially if they have previously expressed administrative grievances. This could damage carefully built trust within teams.

Providers with marginalized identities may be hesitant to engage with climate feedback, especially if their needs have commonly been dismissed by organizations. Demographic variables collected via surveys are useful in identifying areas of need. Conversely, those who are members of a minority within the organization risk being identified. For example, an African American faculty member who holds the rank of professor in an administrative position and who also identifies as gender nonbinary could be easily identified in the data set. Psychologists conducting climate surveys will be tasked with providing aggregated feedback to key organizational stakeholders, which should be handled with transparency and delicacy. In the final analysis, psychologists who are providing feedback may find themselves in a vulnerable position, particularly if the feedback reveals significant organizational dissatisfaction.

Evidence-Based Assessment and Practice Considerations

Interventions for addressing burnout and well-being among healthcare professionals fall into three model categories: (1) individual treatment/counseling/consultation, (2) group-based intervention, and (3) system-level assessment and intervention. The preferred approach is dependent on three factors. First, we must consider the relationship and role of the psychologist with key stakeholders. In the case of Dillon, key stakeholders are both the directors/administrators and recipients of the programming. Second, we need to consider the expertise of the psychologist who finds themself in this role. In some cases, the psychologist is autonomous regarding what and how interventions are delivered. Other times, the psychologist must respond to specific requests made regarding topics, content, and modalities of an intervention. Finally, the psychologist must construct an intervention approach that meets both the needs and desires of the key stakeholders while also adhering to evidence-based practice and their own professional and ethical guidelines. A systematic approach to resolving ethical dilemmas (e.g., Kanzler et al., 2013) is especially pertinent when considering the attributes of each of the three models.

Model 1: Individual Treatment/Counseling/Consultation Model

In this model, providers (including learners) can either self-refer or be referred by others (e.g., training directors, supervisors) to meet with the psychologist. A primary consideration is the location of the service provision. Not unlike models of integration in medical settings, services may be co-located (separate within the clinic but nearby) or elsewhere. In the case of our psychologist, Dillon, the stakeholders are requesting that there be a co-located service. Another possibility is that such services may be in another location but within the same system. Two such examples of these service models are at the University of Utah Health Employee Resiliency Center (https://healthcare.utah.edu/wellness/resiliency-center/) and the Christianacare Center for WorkLife Wellbeing (https://christianacare.org/us/en/for-health-professionals/center-for-worklife-wellbeing). As discussed earlier, this model—although quite convenient for those requesting it—introduces a host of ethical considerations (see Table 1). Finally, there may be a designated external entity to which referrals are made (e.g., employee assistance programs).

Within this model, there may also be informal support requested of the psychologist in the form of a confidential consultation. For psychologists who have worked in medical clinics, it is not unusual for a colleague to request a closed-door conversation to obtain advice or referral information. Although psychologists may find this to be an ethical conundrum, healthcare providers may see such sharing of services as commonplace. Informal consultations have clear benefits with respect to relationship and trust building among healthcare colleagues and key stakeholders. Nonetheless, the psychologists walk a fine line when providing such consultation given the many potential costs related to mandatory reporting. For example, psychologists may uncover potentially unsafe circumstances, making such consultations fraught with peril.

A vital consideration within this individual service provision model is the referral source (i.e., individual self-referred versus referred by another person). If referred by others, there may be some concern about provider impairment or unprofessional behavior. In this situation, the referring party may in some instances also request that the psychologist report back regarding the referred party’s progress. A firewall regarding confidentiality between supervisors and the psychologist can be difficult to establish and maintain. From the perspective of leadership, this may be an especially convenient and confidential way of tracking how some problems are addressed. Such tracking may even be an accreditation reporting requirement. This is the model requested by the clinic medical and residency training directors in our clinical vignette.

In many US states, there are health or mental health programs that provide assessment and treatment for providers who may have displayed mental health problems, unprofessional behavior, or impairment due to a variety of factors. When a physician/provider is referred to such agencies, it is often not voluntary. Such a referral becomes “high stakes” because individuals may, consequently, lose the right to confidentiality or even lose their license and ability to practice in that state. It is not surprising that key stakeholders and administrators may wish to handle such cases in-house to avoid aversive interactions and maintain a positive reputation of the department, division, or training program as being problem free. In fact, some departments or divisions have hired and embedded an in-house mental health provider to serve their own personnel. In some cases, the mental health provider’s direct supervisor may be the chair or director of that entity.

Assessment Considerations

Psychologists working within this model should carefully consider the role of the service especially as it pertains to assessment. The depth and breadth of assessment is certainly at the discretion of the psychologist. If the primary purpose of the psychologist’s role is consultation, then very brief screening can suffice for determining next steps. Screening can take the form of validated screening measures or a conversation to ascertain the difficulties cited by the individual such as an informal functional assessment of behavior. It is our belief that psychologists who are in positions like that of Dillon in our clinical vignette should avoid any in-depth assessment and opt for screening, triage, and immediate referral or warm hand-off to another mental health professional when possible.

Model 2: Group-Based Intervention

A common approach to intervention targeting burnout, resilience, and well-being is group-based programming focused on a specific topic or skill development. Within some medical specialties, there is a robust history of group-based interventions to support medical trainees (primarily medical residents). For example, in the 1950s seminars were developed for medical doctors that were psychoanalytic in nature. Developed by Michael Balint, these weekly groups met sometimes for all years of medical residents’ training in general practice (now family medicine in the US). Still employed today, Balint groups are sometimes led or co-led by psychologists and are one tool designed to buffer the effects of burnout through providing peer support and relational connection among healthcare workers. These are small, open-ended, experiential learning groups designed to help healthcare workers manage difficult patient–provider relationships while building empathy for both them and their patients. Overall, research results for these groups are mixed (Van Roy et al., 2015). Nonetheless, in programs with a tradition and culture of Balint groups, psychologists would be advised to be prepared to lead and/or participate in them.

In group-based models it is most common that foci are singular and groups meet for an average of 1 to 8 sessions. It is our experience that program recipients specifically request that preferred topics and content be evidence-based and, sometimes, quite brief (e.g., a 20-min grand rounds presentation). Common topics are those that demonstrate effectiveness for enhancing subjective well-being, resilience, or stress. Some examples of these topics include mindfulness, meditation, sleep, resilience training, joy in health care, dealing with compassion fatigue, and/or moral injury. For reasons discussed in the Background section, explicit targeting of burnout within the individual is generally discouraged. Those who attend these programs typically want to be able to employ practical and brief tools that yield immediate perceived benefit. In fact, in our own program (CPRP), each of the four, 50-min sessions present a maximum of three activities for the attendee to try while in session and at home between sessions. The activities are designed to require 1–15 min to perform. Attendees from previous iterations of the content have commented on how much the brevity of activities is appreciated and perceived to be effective.

In group-based interventions, the psychologist may be the sole leader or co-lead with a healthcare provider colleague. The psychologist should be aware that healthcare providers may prefer to have such groups led by a trusted colleague from their own discipline. In these cases, it is possible that the psychologist either becomes a co-leader or provides training for trainers. “Train-the-Trainer” models may be the preferred approach among some groups or professional disciplines. In our experience, when training others to present programming developed by psychologists, extra effort and assistance is often needed to assist new trainers to conduct effective groups even when content is scripted.

In devising or employing programming for groups, a sound evidence base and requisite expertise is vitally important. Although the common topics may seem intuitive for the psychologist, many programs have been researched and piloted or tested in controlled trials. Skillfully leading meditation and mindfulness, for example, may require additional training and certification. The popular 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program (Marotta et al., 2022) and the brief 4-week adaptation Koru Mindfulness (Greeson et al., 2014) both require teacher training and certification (see https://professional.brown.edu/certificate/mindfulness and https://korumindfulness.org/teacher-certification/benefits/, respectively). Similarly, another popular intervention program HeartMath (Buchanan & Reilly, 2019; Elbers & McCraty, 2020) also requires instructor training (https://www.heartmath.org/research/science-of-the-heart/).

Multidimensional programs grounded in theory are useful in addressing burnout. Positive psychology programs provide excellent conceptual models such as the PERMA model of well-being (Seligman, 2018). The CPRP employs the PERMAH model (PERMA plus Health) as an organizational platform for program content. The model itself includes facets of well-being: positive emotion, relationships, engagement, meaning, accomplishment, and health as common pillars of individual well-being. Many of these pillars (e.g., positive emotion, engagement, meaning) have been shown to buffer effects of burnout in healthcare professionals (Bazargan-Hejazi et al., 2021; Beacham et al., 2020). Programs utilizing this model employ activities and topics associated with enhancing each of the PERMAH pillars in every session including (1) art of balance, (2) pragmatic mindfulness, (3) positive and negative emotion, and (4) values-based decision-making throughout the day (Beacham et al., 2020).

Another approach in delivering group-based content is to adapt a model employed in clinical populations for application in professionals. The PRISM program, a manualized, skills-based coaching program originally developed for adolescents and young adults with serious/chronic illness, was adapted to support healthcare workers and staff at Seattle Childrens Hospital. The “PRISM at Work” program examined effects of 6 weekly 1-h sessions, covering (1) science of resilience, (2) stress management, (3) goal setting, (4) cognitive reframing, (5) meaning making, and (6) coming together and moving forward with resilience. Notably, groups were led by non-medical facilitators with psychology and social work graduate degrees (Yi-Frazier et al., 2022).

Assessment Considerations

In each of the example group interventions or programs, outcome measures utilized tend to be pertinent to the topics or program focus areas and not to clinical outcomes (i.e., depression or anxiety). For example, programs employing the PERMA(H) model may elect to use the PERMA Workplace Profiler, which assesses each model component plus scales assessing heath, negative emotion, and a single item for loneliness (Butler & Kern 2016). Additional measures may assess mindfulness (e.g., Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; Bohlmeijer et al., 2011; Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale; Feldman et al., 2007), positive affect/emotion (e.g., Positive and Negative Affect Scales; Watson et al., 1998), resilience (e.g., Brief Resilience Scale; Smith et al., 2008) and job satisfaction items or burnout (e.g., Maslach Burnout Inventory; Maslach et al., 2018). This list is certainly not comprehensive and there are numerous excellent ways to assess group-based interventions.

Programs and interventions typically select measures based on validity/reliability, brevity, and budget as not all measures are publicly available. Most programs also include open-ended items for program attendees to provide feedback. In the case of our own programs, we include session-by-session ratings for usefulness, likelihood of applying, and confidence in applying the information presented (0 = Not at all to 10 = Extremely) and open-ended questions regarding what was most enjoyed and suggestions for future presentations. At the end of each session, attendees are provided with a QR code to access these items via smart phone. We have been impressed by the thoughtfulness, detail, and helpfulness of attendee responses. We have received feedback about our materials, presentation, facilitators, and even requests for specific food at sessions (including a recent request for ham sandwiches). These items are perhaps the most important as they provide us with the ability to respond quickly to needs of the group attendees.

Model 3: System-Level Assessment and Intervention

There is broad consensus within health care that until system-level drivers of burnout are adequately addressed, directing interventions solely toward individual providers is misguided. Recalling that drivers of burnout arise from six areas of work life (workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values), burnout syndrome reflects a mismatch between the system and persons working in those systems. Psychologists are advised to review the associated literature in this area. There is certainly recognition of the need to address provider well-being and mental health access and stigma. An appreciable portion of the National Academy of Medicine (2022) National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being clearly contextualizes stated priorities within broader system-level interventions stating, “For health systems, changing the environment and culture will require a systems approach of active and engaged executive leadership that meaningfully involves staff throughout the organization…” (pp. 9–10). Much can also be learned from business and organizational management models regarding how to address burnout most effectively in systems. Harvard Business Review (HBR) (2021) published the HBR Guide to Beating Burnout in which the first chapter is entitled “Rethinking Burnout. It’s a workplace problem, not a work-life balance problem” (p. 1–16). The HBR guide presents ways to address workplace burnout and well-being across all levels of organizations: system, managerial/leadership, team, and individual.

As efforts to address burnout and enhance resilience and well-being necessitate focus on system-level solutions, this does not preclude the clinically trained psychologist from participating in such efforts. Successful solutions within organizations, clinics, and teams are predicated on integrating the voices of the individuals working in those settings.

It is common for departments and organizations to conduct climate surveys on a regular basis. Psychologists’ training in survey construction, statistical analysis, and/or interpretation of data can be useful. If, for example, organizations wished to identify actionable steps in addressing climate and well-being, psychologist-led focus groups may be useful. One such model integrated the drivers of burnout with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to devise a “Physician Wellness Hierarchy Designed to Prioritize Interventions at the Systems Level” (Shapiro et al., 2019). At each level of the hierarchy, actionable examples are provided to focus group members. For example, having a clean environment, adequate access to restroom facilities, and time for breaks and meals are reflective of both meeting basic needs and demonstrating respect for the employees. At the highest levels of the hierarchy, authors present examples of concrete actions that administration can take to foster employees’ ability to contribute to their work at their highest level of potential.

Assessment Considerations

Assessment in this model requires the integration of measures and metrics that can reflect change in the broader aggregate as opposed to change in smaller groups or within individuals. This is an area unfamiliar to many psychologists and requires cultivation of the ability to view meaningful outcomes from various perspectives. Key organizational metrics may be defined within the 5-pointed Quintuple Aim (Nundy et al., 2021). Determinants of successful outcomes may be positive changes in patient outcomes, cost savings in care delivery, patient satisfaction, provider satisfaction and well-being, and indicators of health of the clinical population served by a clinic, team, or system. These metrics and indicators are often pre-defined or measured by or within the system.

If assessing burnout indicators, it is recommended that such measures be designed for aggregate reporting across groups. The Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach et al., 2018) is the “gold standard” among burnout measures. Although often employed erroneously to measure individual burnout levels, the measure is designed to be used as a research tool for group-based measurement and reporting (Maslach & Leiter, 2021). Maslach and Leiter also caution that the MBI should not be used in isolation. So, if a goal is to assess how people are reacting to six key components of their workplace culture (workload, control, reward, community, fairness, values), Maslach and Leiter recommend utilizing a parallel corollary measure assessing these areas (e.g., Areas of Worklife Survey).

Conclusions and Lessons Learned

In considering the roles of psychologists in addressing burnout, resilience, and well-being in healthcare settings, the authors’ collective knowledge and experience highlight the parallel processes that each of us has seen in interprofessional programs and integrated models of care. Although the parallels are many, we agree that there are four primary areas to consider. First, there are appreciable differences in professional and training cultures in healthcare settings in which psychologists work. Second, those in administrative and supervisory roles base requests of psychologists on their own healthcare professional culture and their sometimes limited understanding of the skill sets that psychologists bring to these settings. Third, many psychologists—especially those early in their careers—will go to extraordinary lengths to cultivate positive relationships with their medical counterparts and supervisors. Finally, addressing the well-being of healthcare providers is an area of increasing demand for psychology. Meeting that demand can extend the psychologists’ scope of practice and competence beyond our traditional training.

Differences in Professional and Training Cultures

As we see in Dillon’s activities, inherent to their position, they find themself managing multiple roles. In a typical week, they are serving in a clinical and supervision role across multiple clinics (i.e., family and geriatric medicine, anesthesiology) and they are in an evaluative role with the same learners across these clinics. This affords Dillon the excellent opportunity to forge relationships among the learners and clinic faculty. Dillon also has an advantage of observing learners across settings over time. From the standpoint of the training and medical directors, Dillon is the perfect person to interface with learners (or faculty) who may be having difficulty. This arrangement is described as a “no brainer” in the vignette because everyone is pleased with Dillon’s leadership in Balint groups. Therefore, from the perspective of the directors, extending this level of support through individual intervention (Model 1) seems to be quite beneficial.

Limited Understanding of the Psychologists’ Skill Sets and Ethical Code of Conduct

The request made of Dillon and countless other psychologists in similar positions may not be unusual. Healthcare providers may have a limited knowledge of what psychologists can “do.” Often, healthcare providers and administrators may believe that psychologists just “do” therapy. Much like understanding integrated models of care, the psychologist must recognize that this request may be viewed as an assumed part of being in a departmental and training “family.” Dillon finds themself in a conundrum wherein ethical codes of conduct are defined differently in this departmental context. Now, Dillon’s task is to find a successful way forward to meet expectations regarding the deliverables through a model that is also implemented ethically for all concerned parties. This process is iterative and calls upon the psychologist to methodically follow steps and discuss concerns—perhaps via consultation with a trusted colleague.

Prioritizing Positive Relationships

As is highlighted in the vignette, Dillon has cultivated positive relationships throughout their postdoctoral fellowship to garner a full-time position as a faculty member and preceptor in the same department. Fostering trust and positive working relationships among healthcare colleagues is often the determining factor in a psychologist’s success in interprofessional and integrated care. Dillon has been diligent in this area by volunteering for projects and adopting a stance of saying yes to opportunities. Dillon is now being entrusted with an extraordinary opportunity. The successful outcome of this new facet of Dillon’s work may depend on their ability to provide a value-added alternative that meets all stakeholder needs. Perhaps a programmatic alternative (Model 2) with more extensive reach and less potential for ethical dilemmas is the best solution (see Table 1).

Extending Psychologists’ Scope of Practice and Competence

As in our example of Dillon, it may be crucial for psychologists to extend their scope of expertise in new areas. This requires reviewing the literature, developing skills, obtaining training and credentials, or obtaining access to experts necessary to provide programming inherent to Models 2 and 3. Each of these models has the potential for enormous positive impact in the system but requires that the psychologist do their own due diligence in preparing for their role in these programmatic intervention approaches.

Key Clinical Considerations

There is extraordinary need and opportunity for psychologists in addressing healthcare provider burnout, resilience, and well-being. The possible approaches to addressing these issues fall into three general models: (1) individual treatment/counseling/consultation, (2) group-based interventions, and (3) system-level assessment and intervention.

Not unlike integrated primary and specialty medical settings, traditional training as a health service psychologist may not provide the requisite knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for success in this area.

Psychologists must attend carefully to the needs of learners and providers who are members of marginalized and vulnerable groups in healthcare systems.

The ethical challenges in this work are replete and, yet, largely uncharted for the psychologist wishing to do this work.

Each of the presented models has the potential for enormous positive impact affecting those who work in healthcare systems, but it requires that the psychologist do their own due diligence in adequately preparing to perform their role in these programmatic initiatives.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Health Resources and Services Administration Health and Public Safety Workforce Resiliency Training Program Funding (HRSA-22-109), “Cultivating Personal Resilience Program” Awarded to Spalding University School of Professional Psychology, January 2022.

Biographies

Abbie O’Ferrell Beacham,

PhD, is a Clinical Health Psychologist and the Director of Behavioral Sciences at the University of Louisville (UofL) School of Dentistry. Prior to returning to UofL—her PhD alma mater—she served at the University of Colorado School of Medicine as an Associate Director of the Resilience Program. Dr. Beacham’s research, teaching, and clinical work focus on interprofessional team-based and integrated care as well as burnout, resilience, and well-being among healthcare professionals.

Andrea Westfall King,

PsyD, is an Assistant Professor and Director of the Health Psychology Emphasis Area at Spalding University. Dr. King completed her internship at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and fellowship at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, specializing in pediatric psychology, specifically the management of chronic illness across disease groups. Dr. King’s current clinical and research interests include interdisciplinary care and resilience-based training for children and their parents.

Brenda F. Nash,

PhD, is the Psychology Chair at Spalding University and the Chair of the Kentucky Board of Examiners of Psychology. A graduate of the University of Kentucky, Dr. Nash specializes in post-traumatic growth, and teaching such to the next generation of psychologists. She was the 2020 Faculty of the Year at Spalding and the 2022 Psychologist of the Year in Kentucky. She is also a 2021 alumnae of APA’s Leadership Institute for Women in Psychology.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Abbie Beacham, PhD, and Andrea King, PsyD, declare no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript or programming described herein. Brenda Nash, PhD, serves as the Principal Investigator on a Health Resources and Services Administrator grant in program development and evaluation of resilience programming for healthcare professions trainees.

References

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. (2016). Common program requirement Retrieved from https://www.acgme.org/newsroom/2016/1/common-program-requirements-revisions/

- Afonso A, Cadwell J, Staffa S, Zurakowski D, Vinson A. Burnout Rate and Risk Factors among Anesthesiologists in the United States. Anesthesiology. 2021;134:683–696. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2021). The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/AcademicNursing/pdf/Essentials-2021.pdf

- American College of Cardiology [@ACCinTouch]. (2021, December 3). “Achieving this Quintuple Aim is a worthy goal that ties directly to the ACC’s Mission to transform CV care & improve ♡ health,” Dr. @ditchhaporia writes in her #JACC Leadership Page. [Image attached] [Link attached] [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/ACCinTouch/status/1466755354662952975/photo/1

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, amended effective June 1, 2010, and January 1, 2017). https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx

- Bazargan-Hejazi S, Shirazi A, Wang A, Shlobin A, Karunungan K, Shulman J, Marzio R, Ebrahim G, Shay W, Slavin S. Contribution of a positive psychology-based conceptual framework in reducing physician burnout and improving well-being: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:593. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-03021-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beacham, A., Janosy, N., Brainard, A. and Reese, J. (2020). A brief evidence-based intervention to enhance workplace well-being and flourishing in health care professionals: feasibility and pilot outcomes. Journal of Wellness, (2)1, Article 7. 10.18297/jwellness/vol2/iss1/7

- Berg, S. (2020, July 29) Physician Health: Burnout isn’t due to resiliency deficit. It’s still a system issue. American Medical Association Practice Management News. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/burnout-isn-t-due-resiliency-deficit-it-s-still-system-issue

- Berwick D, Nolan T, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health AffAirs. 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–576. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer E, ten Klooster PM, Fledderus M, Veehof M, Baer R. Psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Assessment. 2011;18(3):308–320. doi: 10.1177/1073191111408231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TM, & Reilly PM. (2019). The impact of HeartMath resiliency training on health care providers. Dimens Crit Care Nurs, 38(6), 328–336. 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000384 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Butler J, Kern ML. The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Wellbeing. 2016;6(3):1–48. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond S, Thomas C, Desai S, Holliday E, Jagsi R, Schmitt C, Enestvedt B. Gender differences in publication productivity, academic rank, and career duration among US academic gastroenterology faculty. Academic Medicine. 2016;91:1158–1163. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye, L. N., T. D. Shanafelt, C. A. Sinsky, P. F. Cipriano, J. Bhatt, A. Ommaya, C. P. West, and D. Meyers. (2017). Burnout among health care professionals: A call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. (NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper). National Academy of Medicine. 10.31478/201707b

- Elbers J, McCraty R. Heartmath approach to self-regulation and psychosocial well-being. Journal of Psychology in Africa. 2020;30(1):69–79. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2020.1712797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman G, Hayes A, Kumar S, Greeson J, Laurenceau JP. Mindfulness and emotion regulation: The development and initial validation of the cognitive and affective mindfulness scale revised (CAMS-R) Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2007;29(3):177–190. doi: 10.1007/s10862-006-9035-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yi-Frazier, J., O’Donnell, M., Adhikari, E., Zhou, C., Bradford, M., Garcia-Perez, S., Shipman, K., Hurtado, S., Junkins, C., O’Daffer, A., & Rosenberg, A. (2022). Assessment of resilience training for hospital employees in the era of COVID-19. JAMA Network Open, 5(7):e2220677. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.20677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Garcia, L.C., Shanafelt, T.D., West, C.P., Sinsky, C.A., Trockel, M.T., Nedelec, L., Maldonado, Y.A., Tutty, M., Dyrbye, L.N., Fassiotto, M. (2020). Burnout, depression, career satisfaction, and work-life integration by physician race/ethnicity. JAMA Netw Open, 3(8), e2012762. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greeson JM, Juberg MK, Maytan M, James K, Rogers H. A randomized controlled trial of Koru: a mindfulness program for college students and other emerging adults. J Am Coll Health. 2014;62(4):222–233. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.887571.PMID:24499130;PMCID:PMC4016159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvard Business Review. (2021). HBR guide to beating burnout. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Health Resources and Services Administration. (2021). Health and Public Safety Workforce Resiliency Training Program. Retrieved on October 20, 2022, from: https://www.hrsa.gov/grants/find-funding/HRSA-22-109

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. (2016). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update.https://ipec.memberclicks.net/assets/2016-Update.pdf

- Kanzler KE, Goodie JL, Hunter CL, Glotfelter MA, Bodart JJ. From colleague to patient: Ethical challenges in integrated primary care. Families, Systems, & Health. 2013;31(1):41–48. doi: 10.1037/a0031853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter MP, Maslach C. Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burnout Research. 2017;3(4):89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2016.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marotta M, Gorini F, Parlanti A, Berti S, Vassalle C. Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on the Well-Being, Burnout and Stress of Italian Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Clin Med. 2022;11(11):3136. doi: 10.3390/jcm11113136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S., Leiter, M., Schaufeli, W., & Schwab, R. (2018). Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI, 4th ed.). Mind Garden Inc.

- Maslach, C. and Leiter, M.P. (2021, March 19). How to measure burnout accurately and ethically. Harvard Business Review.https://hbr.org/2021/03/how-to-measure-burnout-accurately-and-ethically

- McMurray, J.E., Linzer, M., Konrad, T.R., Douglas, J., Shugerman, R., Nelson, K. (2000). The work lives of women physicians results from the physician work life study. The SGIM career satisfaction study group. J Gen Intern Med, 15(6), 372–80. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2000.im9908009.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Memon, A., Taylor, K., Mohebati, L., Sundin, J., Cooper, M., Scanlon, T., & de Visser, R. (2016). Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: a qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open, 6:e012337. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Menon, N.K., Shanafelt, T.D., Sinsky, C.A., et al. (2020). Association of Physician Burnout With Suicidal Ideation and Medical Errors. JAMA Netw Open, 3(12):e2028780. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mills, K. I. (Host). (2021, July 28). Why we’re burned out and what to do about it, with Christina Maslach, PhD (Episode 152) [Audio podcast episode]. In Speaking of Psychology. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/burnout

- National Academy of Medicine. (2022). National plan for health workforce well-being. 10.17226/26744

- National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Taking action against clinician burnout: a systems approach to professional well-being. The National Academies Press. 10.17226/25521 [PubMed]

- Nundy S, Cooper L, Mate K. The quintuple aim for health care improvement: a new imperative to advance health equity. JAMA. 2021;327(6):521–522. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.25181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the U.S. Surgeon General. (2022). Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/health-worker-wellbeing-advisory.pdf [PubMed]

- Przedworski J, Dovidio J, Hardeman R, Phelan S, Burke S, Ruben M, Perry S, Surgess D, Nelson D, Yeazel M, Knudsen J, van Ryn M. A comparison of the mental health and well-being of sexual minority and heterosexual first-year medical students: a report from the Medical Student CHANGE Study. Academic Medicine. 2015;90(5):652–659. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi R, Raymer L, Kunik M, Fisher J. Facets of career satisfaction for women physicians in the United States: a systematic review. Women Health. 2012;52(4):403–421. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2012.674092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson GE. Stresses on women physicians: consequences and coping techniques. Depress Anxiety. 2003;17(3):180–189. doi: 10.1002/da.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotenstein L, Torre M, Ramos M, Rosales R, Guille C, Sen S, Mata D. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131–1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2018;13(4):333–335. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2018.1437466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini, K., Coyer, C., Brown Speights, J., Donovan, D., Guh, J., Washington, J., & Ainsworth, C. (2020). Racism as experienced by physicians of color in the health care setting. Fam Med, 52(4), 282–287. 10.22454/FamMed.2020.384384. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T. (2021). Physician Well-being 2.0: Where Are We and Where Are We Going? Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 96(10), 2682–2693. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt T. D., J. Ripp, M. Brown, and C. A. Sinsky. (2020, May 08). Creating a resilient organization: caring for healthcare workers during crisis. American Medical Association. Retrieved September 24, 2020, https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-05/caring-for-health-care-workers-covid-19.pdf

- Shanafelt TD, Schein E, Minor LB, Trockel M, Schein P, Kirch D. Healing the professional culture of medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1556–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro D, Duquette C, Abbott L, Babineau T, Pearl A, Haidet P. Beyond burnout: a physician wellness hierarchy designed to prioritize interventions at the systems level. The American Journal of Medicine. 2019;132(5):556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;15(3):194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R., Johnson, A., Targan, A., Piggott, C., Kvach, E. (2022). Taking Our Own Temperature: Using a Residency Climate Survey to Support Minority Voices. Fam Med, 54(2), 129–133. 10.22454/FamMed.2022.344019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sullivan A, Hersh C, Rensel M, Benzil D. Leadership inequity, burnout, and lower engagement of women in medicine. Journal of Health Service Psychology. 2023;49:33–39. doi: 10.1007/s42843-023-00078-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Physicians Foundation (2021, June). 2021 Survey of America’s Physicians COVID-19 Impact Edition: A Year Later. https://physiciansfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2021-Survey-Of-Americas-Physicians-Covid-19-Impact-Edition-A-Year-Later.pdf

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). Highlights of women's earnings in 2019. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-earnings/2019/home.htm

- Van Roy K, Vanheule S, Inslegers R. Research on Balint groups: a literature review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2015;98(6):685–694. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark L, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;54(6):1063–1079. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West C, Shanafelt T, Kolars J. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306:952–956. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West C, Dyrbye L, Erwin P, Shanafelt T. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272–2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West, C.P., Dyrbye, L.N., Sinsky, C., et al. (2020). Resilience and Burnout Among Physicians and the General US Working Population. JAMA Netw Open, 3(7):e209385. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2019, May 28). Burn-out as an occupational phenomenon: international classification of diseases. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases