Abstract

The most important difference between enzyme and small molecule catalysts is that only enzymes utilize the large intrinsic binding energies of nonreacting portions of the substrate in stabilization of the transition state for the catalyzed reaction. A general protocol is described to determine the intrinsic phosphodianion binding energy for enzymatic catalysis of reactions of phosphate monoester substrates, and the intrinsic phosphite dianion binding energy in activation of enzymes for catalysis of phosphodianion truncated substrates, from the kinetic parameters for enzyme-catalyzed reactions of whole and truncated substrates. The enzyme-catalyzed reactions so-far documented that utilize dianion binding interactions for enzyme activation; and, their phosphodianion truncated substrates are summarized. A model for the utilization of dianion binding interactions for enzyme activation is described. The methods for the determination of the kinetic parameters for enzyme-catalyzed reactions of whole and truncated substrates, from initial velocity data, are described and illustrated by graphical plots of kinetic data. The results of studies on the effect of site-directed amino acid substitutions at orotidine 5'-monophosphate decarboxylase, triosephosphate isomerase, and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase provide strong support for the proposal that these enzymes utilize binding interactions with the substrate phosphodianion to hold the protein catalysts in reactive closed conformations.

Keywords: Enzyme Catalysis, Enzyme Activation, Decarboxylation, Proton Transfer, Hydride Transfer, Phosphoryl Transfer, Conformational Change

1. INTODUCTION

The total stabilization of the transition state for an enzyme-catalyzed reaction is equal to the sum of the stabilizing interactions between the catalyst and the transition state [1, 2]. Large rate accelerations are not possible for enzyme-catalyzed single substrate reactions of small molecules such as ethanol and acetaldehyde, because of the limited interactions between the protein and transition state. Protein catalysts and the metabolic pathways in which they function have therefore evolved through natural selection to catalyze the reactions of substrates that carry nonreacting handles at small reactive functional groups [3]. The handles provide the large binding energy that is required to stabilize many enzymatic transition states. They provide the large specificity that nature's most efficient catalysts show in binding their transition states with a much higher affinity than substrate [2, 4, 5].

Functional-group handles are present at many enzymes noted for their high catalytic efficiency [3, 6], and at metabolic pathways that support a large net flux of metabolites [3, 7]. For example, the phosphodianion at phosphate monoesters [3, 7, 8] are carried through many steps of glycolysis [9] and the hexose monophosphate shunt [10], while the coenzyme A handle at thioesters of carboxylic acids feature prominently for enzymes at pathways that function in the synthesis and degradation of fatty acids [11–13]. The rationale for the incorporation of large binding affinity handles, which are passed along the most efficient metabolic pathways, was obvious to Bill Jencks over fifty years ago [14], but was not examined until the development of the methods described in this chapter. These experimental methods quantify the stabilization of enzymatic transition states by interactions between protein catalysts and high-affinity functional-group handles.

2. DETERMINATION OF INTRINSIC FRAGMENT BINDING ENERGIES

The intrinsic binding energy of a substrate for an enzymatic reaction is defined as the total ligand binding utilized for stabilization of the enzymatic transition state [14]. This intrinsic substrate binding energy is generally much greater than the binding energy observed at the Michaelis complex, because the full expression of large substrate intrinsic binding energies at the Michaelis complex favors the effectively irreversible binding of substrate [4, 14, 15]. X-ray crystal structures show that complexes between enzymes and their substrates, or transition state analogs, are stabilized by extensive networks of electrostatic interactions with nonreacting substrate handles [16–20]. An important step towards evaluating the rate accelerations for enzymatic reactions is to determine the contribution of binding interactions to these nonreacting handles to the stabilization of the substrate Michaelis complex (anchoring interactions), and to the specific stabilization of the enzymatic transition state (activating interactions) [2, 4, 5]. We will describe protocol developed over the past 15 years for determining the total intrinsic binding energies for nonreacting substrate handles, and for partitioning this binding energy into anchoring and activating interactions.

2.1. Intrinsic Phosphodianion Binding Energy.

We first focused on the development of protocol for determining the intrinsic binding energy of the phosphodianion handle of phosphate monoesters substrates for the isomerization reaction catalyzed by triosephosphate isomerase (TIM, Scheme 1A) [21–26], the decarboxylation and proton transfer reactions catalyzed by orotidine 5'-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC, Scheme 1B) [15, 26–28], and the hydride transfer reaction catalyzed by glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH, Scheme 1C) [26, 29]. These protocol may be generalized to enzyme-catalyzed reactions of other phosphate monoesters [7, 26, 29], and to enzyme-catalyzed reactions of substrates with nonreacting adenosyl [6, 30] and -CoA [11, 12, 31] handles attached to the reacting center.

Scheme 1.

(A) The isomerization reaction of D-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP) to form dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) catalyzed by triosephosphate isomerase (TIM). (B) The decarboxylation reaction catalyzed by orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC). (C) The hydride transfer reaction of DHAP to form D-glycerol 3-phosphate (G3P) catalyzed by glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH).

The total intrinsic binding energy for the phosphodianion handle of alkyl phosphate substrates has been calculated as the difference between the activation barriers for the enzyme-catalyzed reaction of whole substrate and the catalyzed reaction of the substrate fragment SH. This difference in activation barriers is obtained using eq 1, where (Scheme 2A) and (Scheme 2B) are the second-order rate constants for enzyme-catalyzed reactions of the whole substrate and the substrate fragment, respectively [22]. Values for −= (11–13 kcal/mol have been determined for reactions catalyzed by the following six enzymes: TIM [22], glucose 6-phosphate isomerase (PGI) [7], GPDH [29], glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) [7], 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGD) [7], and OMPDC [28]. These are larger than the total substrate binding energy of ≤ 8 kcal/mol for these enzymes, so that a significant fraction of the intrinsic dianion binding must be expressed specifically at the transition state for these enzyme-catalyzed reactions [2, 4, 5].

Scheme 2.

The kinetic parameters for enzyme-catalyzed reactions of the whole substrate (, 1A), the truncated substrate piece S-H (, 1B), and for activation of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction of S-H by the second substrate piece (, 1C).

| (1) |

| (2) |

2.2. Intrinsic Binding Energy: Ground and Transition State Interactions.

When the total intrinsic phosphodianion binding energy exceeds the total substrate binding energy, protein-dianion interactions do not function solely to anchor the substrate to the protein. In fact, it is well known that protein-dianion interactions are often utilized to drive large protein conformational changes [16–18, 20, 32, 33]. The binding energy so utilized is not expressed in the value for the Michaelis constant , but must contribute in some other way to the enzyme's catalytic efficiency.

We further evaluated the role of dianion-binding energy in enzyme catalysis by cutting the covalent connection between the phosphodianion and reacting substrate, and examining the effect of the phosphite dianion piece on enzyme activity for catalysis of the reaction of the untethered substrate SH. Phosphite dianion activates many enzymes for catalysis of the reaction of SH [21, 28, 29], as shown by the increase in the observed second-order rate constants for enzyme-catalyzed reactions of SH at increasing [HPO32–] [7, 26]. The slope of plots of against [HPO32–] is equal to the third-order rate constant (Scheme 2C) [7]. Details for the experimental protocol utilized to determine the kinetic parameter are presented in Section 3.2.

The ratio of the rate constants for the dianion activated enzyme-catalyzed reaction and for the unactivated reaction is equal to the rate acceleration for the unactivated reaction caused by addition of 1.0 M phosphite dianion activator. This ratio defines the intrinsic binding energy for formation of the complex between of phosphite dianion and the transition state for the enzyme-catalyzed reaction of SH (eq 2 derived for Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Kinetic mechanism for unactivated and phosphite dianion activated enzyme-catalyzed reactions of phosphodianion truncated substrate S-H to form P-H. The velocities for the unactivated and phosphite dianion activated reactions are defined by the rate constants and , respectively, from Schemes 2B and 2C.

Figure 1 summarizes the results of experiments that were designed to partition the total phosphodianion binding energy (, eq 1) into the binding energy utilized for enzyme activation (, eq 2) and the binding energy utilized to anchor the whole substrate to the enzyme. Values of − = 6–8 kcal/mol have been reported for dianion activation of reactions of truncated substrates catalyzed by six different enzymes for which − = 11–13 kcal/mol [7]. The difference between the total dianion binding energy and the binding energy expressed after cutting the connection to the dianion [] is equal to the binding energy utilized to anchor the whole substrate to the enzyme.

Figure 1.

Partitioning of the total −(11–13) kcal/mol total intrinsic dianion binding energy for enzyme-catalyzed reactions of phosphate monoesters ( eq 1). From −(6–8) kcal/mol of this binding energy is used to activate the enzyme for catalysis of the reaction of SH ( eq 2) and from −(4–8) kcal/mol of this binding energy is utilized to anchor the phosphate monoester substrate to the protein catalyst.

Scheme 4 shows a graph that partitions the total −11.8 kcal/mol intrinsic phosphodianion binding energy (, eq 1) for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation (Scheme 1A) into a −7.7 kcal/mol activating binding energy and a − 4.1 kcal/mol anchoring binding energy. The 4.1 kcal/mol difference between and is equal to the catalytic advantage obtained from connection of the two substrate fragments to form the whole substrate. It is often referred to as the connection energy [34].

Scheme 4.

Partitioning of the total intrinsic phosphodianion binding energy (eq 1) for the decarboxylation reaction catalyzed by OMPDC into (eq 2), the total phosphite dianion binding energy observed in the absence of a covalent connection between the substrate pieces and , the additional transition state stabilization obtained when there is a covalent connection between the substate pieces [34].

The explanations for the variation in the magnitude of energy binding energies and are not fully understood. In two cases they may represent failures of implicit assumptions made in their calculation from eq 1 and 2.

(1) It is assumed that the effect of truncation of the phosphodianion on for the enzymatic reaction is due solely to the loss of intrinsic dianion binding energy. However, the whole substrate DHAP for GPDH-catalyzed hydride transfer (Scheme 1C) is a ketone, while the truncated substrate glycolaldehyde (GA) is an aldehyde. The higher chemical reactivity of aldehydes compared to ketones towards hydride transfer will result in an increase in for GPDH-catalyzed reduction of GA relative to for the ketone DHAP, and a decrease in the apparent intrinsic dianion binding energy This could account for the smaller absolute value of = −11 kcal/mol for GPDH-catalyzed hydride transfer relative to the values of for other enzymes [7].

(2) It is assumed that the same values of will be observed for the enzyme-catalyzed reactions of the whole substrate and the corresponding bound substrate pieces, because the enzyme at both complexes is held in the same reactive loop closed form by interactions with either the substrate phosphodianion or the activator phosphite dianion (see next section). This assumption is supported by the results of computational studies on TIM [35]. However, the estimated value for turnover of the ternary complex to OMPDC (EO is the truncated substrate) is significantly larger than for turnover of the complex to the whole substrate [36], for reasons that are not understood. The large value of − = 8 kcal/mol for phosphite dianion activated OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation, compared with dianion activation of other enzymes [7], may be related to this large rate constant for OMPDC-catalyzed turnover of the ternary complex.

2.3. The Role of the Dianion in Enzyme Activation.

X-ray crystallographic analysis of unliganded forms of TIM, OMPDC and GPDH, and of enzyme complexes to substrates, substrate analogs, or intermediate analogs show that ligand binding to inactive open forms () of these enzymes (, Scheme 5) induces large protein conformational changes that trap the ligand at a closed protein cage [16–20, 25]. Schemes 5A and 5B were developed, respectively, for these enzymes to rationalize phosphite dianion activation of the catalyzed reactions of phosphodianion truncated substrates, and phosphodianion activation of the catalyzed reactions of whole phosphate monoester substrates [2–4, 23]. These models are similar to Koshland’s enzyme induced-fit model, which was first proposed as a mechanism for obtaining enzyme specificity [37, 38].

Scheme 5.

Koshland's induced-fit mechanism [37, 38] for enzymes that exist mainly in an inactive open conformation (), and where the binding interactions between the nonreacting dianion at HPO32– or is utilized stabilize the active closed form of the catalyst . Scheme 5A is for phosphite dianion activation of enzyme-catalyzed reactions of truncated substrates S-H, where [23]. Scheme 5B is for phosphodianion activation of enzyme catalyzed reactions of whole substrates , where [2, 3].

The results of a computational study support the conclusion that the low reactivity of TIM for catalysis of deprotonation of the truncated substrate glycolaldehyde (S-H, Scheme 5A) is due to the small fraction of total enzyme present in the closed form (, Scheme 5) [35]. Phosphite dianion provides binding energy to drive the conformational change from inactive to active (Scheme 5A). The phosphite dianion binding energy observed at the Michaelis complex (= 2 kcal/mol) [21] is small comparison to the total intrinsic transition state binding energy (= 6 kcal/mol [21, 26]. The 4 kcal/mol excess binding energy is utilized to drive the unfavorable enzyme conformational change that activates TIM for catalysis of carbon deprotonation [2, 23].

Scheme 5B shows the utilization of the intrinsic dianion binding energy of the whole substrate to drive the same protein conformational change from inactive to active shown in Scheme 5A; and, with the same effect on the enzyme catalytic activity. By analogy with Scheme 5A, the observed substrate binding energy for Scheme 5B is smaller than the total intrinsic substrate binding energy by the 4 kcal/mol of binding energy that is "wasted" in driving the unfavorable protein conformational change. This apparent squandering of substrate binding energy to drive an unfavorable protein conformational change is required to ensure the differential stabilization of the Michaelis complex [weak binding] and reaction transition state [tight binding], and to thereby avoid tight and irreversible substrate binding.

2.4. Structure-Reactivity Effects.

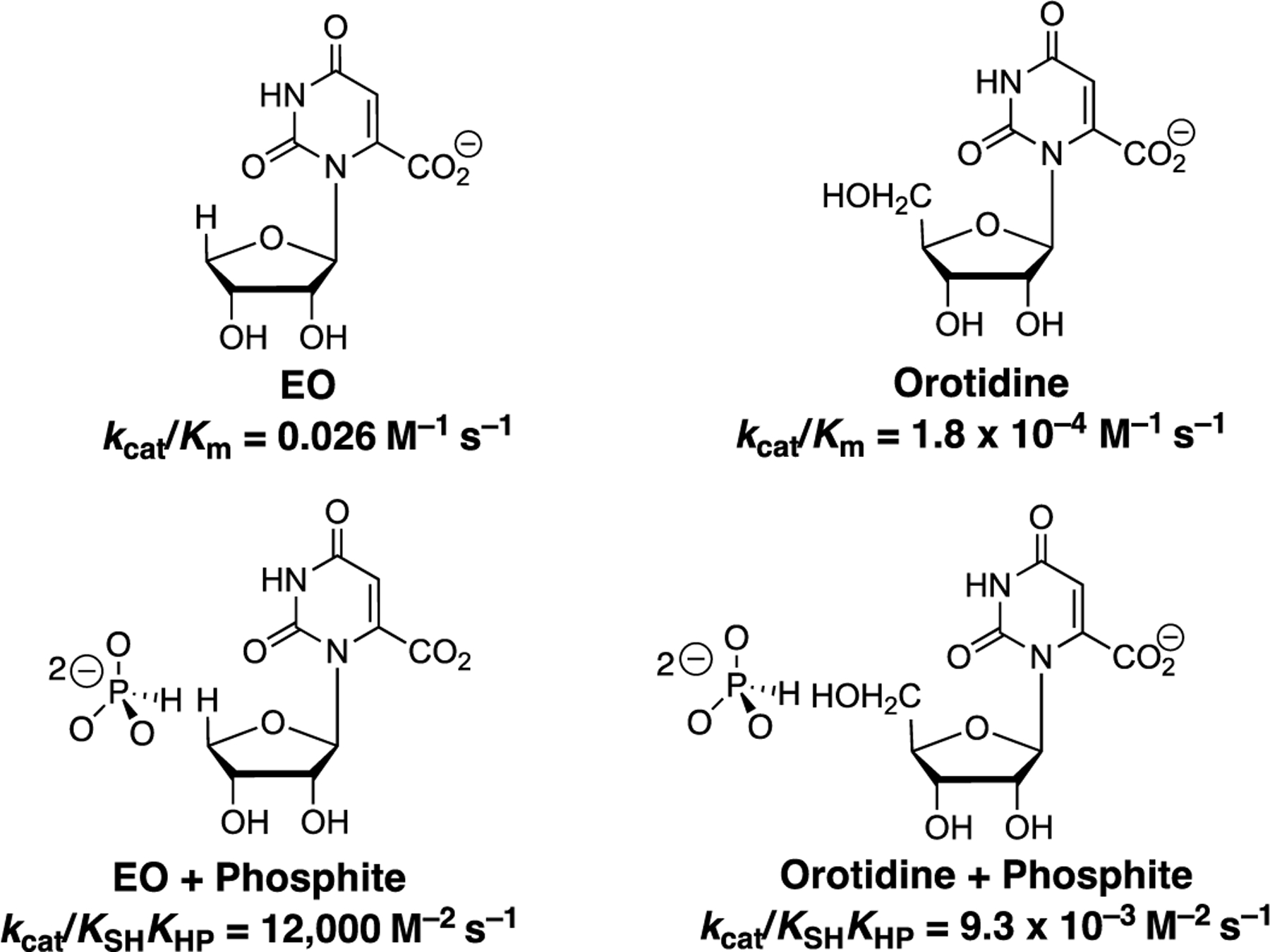

Early experiments to detect dianion activation of enzyme-catalyzed reactions of truncated substrate pieces failed. For example, the products of the hydrolysis of whole substrates orotidine 5'-monophosphate [orotidine + phosphate] or glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate [glyceraldehyde + phosphate] show no detectable activity, respectively for TIM deprotonation of glyceraldehyde [22], or for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of orotidine [39]. The large and complex effects of changing structure on the reactivity of substrate pieces is illustrated in greater detail by kinetic data for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation (Scheme 6). The second-order rate constant for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of the preferred truncated substrate is more than 100-fold smaller than for decarboxylation of orotidine [40]. This is not a simple steric effect on the placement of catalytic side chains, since both orotidine and are substantially smaller than the whole substrate . These results may reflect as yet to be determined destabilizing polar interactions between active-site protein side chains and the of orotidine [40]. The very large ≈106 fold difference in the third-order rate constant for phosphite dianion activated OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of compared to orotidine reflects the combined steric and electronic effect of the at orotidine on the optimal positioning of catalytic side chains at the caged complex to the substrate pieces [40–42].

Scheme 6.

Kinetic parameters for the direct OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of the truncated substrates and orotidine and for the reactions activated by phosphite dianion [28].

These results provide evidence that the acid side chains at the protein-substrate cage are held at positions which show a strong complementary to the transition state for the catalyzed reaction of the whole phosphodianion substrate [43]. The precision in placement of these side chains is perturbed, and the transition states are strongly destabilized when the substrate pieces are too large to easily fit into the catalytically active protein cage [40]. The failure to anticipate these large steric effects has resulted in a long delay in the recognition of the importance of Koshland's induced-fit mechanism in providing a mechanism by which enzymes bind their transition states with a higher affinity than substrate [3, 4].

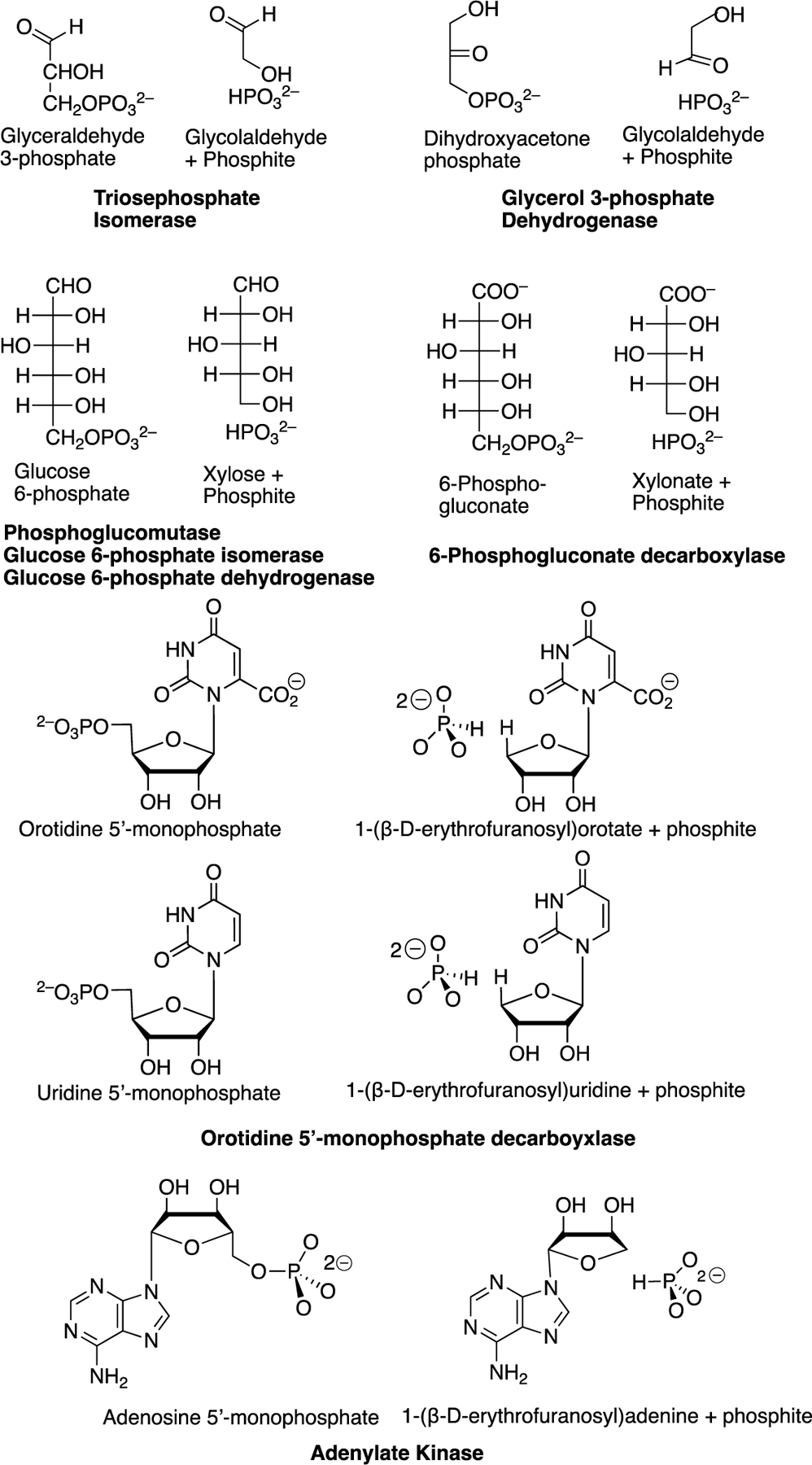

Scheme 7 summarizes published reports of enzymatic reactions where the catalytic activity of the whole phosphate monoester substrate is captured by enzymatic catalysis of reactions of substrate fragments where a has been truncated from the organic substrate piece and an -OH from the phosphate piece. This Scheme reveals the following trends.

Scheme 7.

Enzyme-catalyzed reactions of whole substrates that are effectively mimicked by the enzyme catalyzed reactions of the substrate pieces. Isomerization reaction catalyzed by TIM [21]; hydride transfer reaction catalyzed by GPDH [29]; intramolecular phosphoryl transfer reaction catalyzed by phosphoglucomutase [44]; isomerization reaction catalyzed by PGI; hydride transfer reaction catalyzed by G6PDH [7]; oxidative decarboxylation catalyzed by 6-PGD, [7] decarboxylation and proton transfer reactions catalyzed by OMPDC [27, 28]; and the phosphoryl transfer reaction catalyzed by, adenylate kinase [6, 30].

(1) The substrate pieces GA + phosphite dianion are a good mimic for either DHAP or GAP in reactions catalyzed by TIM and GPDH, where GAP and DHAP are interconverted by the TIM-catalyzed isomerization reaction (Scheme 1A) and DHAP is reduced by NADH to G3P in the reaction catalyzed by GPDH (Scheme 1C).

(2) The substrate pieces xylose + phosphite dianion mimic glucose 6-phosphate in reactions catalyzed by phosphoglucomutase [44], G6PDH [7], and PGI [7], while the pieces xylonate + phosphite dianion are a good mimic for 6-phosphogluconate for the reaction catalyzed by 6PGDH [7].

(3) OMPDC catalyzes: (a) the decarboxylation of the whole substrate OMP and of the complex to + phosphite dianion [28]; and (b) the exchange of deuterium between solvent and the C-5 position of uridine for the whole substrate UMP and the complex to the + phosphite dianion pieces [27], where the deuterium exchange reaction is the first step for the microscopic reverse of the decarboxylation reaction.

(4) There is a large evolutionary pressure to optimize the activity of OMPDC, because this enzyme catalyzes the final step in the biosynthesis the pyrimidine nucleotide UMP [45]; and the activity of adenylate kinase, because this enzyme functions for short periods of extreme stress to ensure that both high energy phosphates of ATP contribute to muscle motion [46, 47]. This pressure has led to the selection of catalytic motifs where the nucleoside fragment of OMP (EO, Scheme 7) is a substrate for the decarboxylation reaction catalyzed by OMPDC and an activator (EA, Scheme 7) for the phosphoryl transfer reaction catalyzed by adenylate kinase [48, 49]. This shows the tremendous ability of protein structures to adapt as needed to produce the large transition state stabilization required for effective catalysis.

3. EXPERIMENTAL PROTOCOL.

The experimental protocol for the determination of the kinetic parameters for enzyme-catalyzed reactions of the phosphodianion truncated substrate, and for phosphite dianion activation of this reaction may generally be adapted directly from published procedures used to determine kinetic parameters for the reaction of the whole substrate. Only the highlights of these procedures are discussed in this Section.

3.1. Enzyme Assays.

The kinetic parameters for the unactivated and fragment-activated reactions of substrate pieces are determined from initial velocity data for reaction of <10% of the truncated substrate SH. When there is a direct spectrophotometric assay [28, 29] to monitor the reaction of the whole substrate, a similar assay will generally be used to monitor the reaction of the phosphodianion truncated substrate piece. In some cases, the slow reactions of truncated substrates were monitored by using HPLC to separate reactants from products, because this assay is more sensitive than the direct spectrophotometric assay [28, 50].

The situation is more complicated when a coupled enzyme assay is used for the whole substrate and the product of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction of the truncated substrate piece is not a good substrate for the coupling enzyme. This is the case for the TIM-catalyzed reactions of GA in water. This reaction was first monitored using proton-NMR by following TIM-catalyzed exchange of deuterium from solvent into unlabeled GA [21]. A more sophisticated NMR assay was next developed using GA labeled with carbon-13 at the carbonyl carbon ([1-13C]-GA) [23], which provided the yields of the three products of TIM-catalyzed reactions in (Scheme 8).

Scheme 8.

Products of TIM-catalyzed reactions of ([1-13C]-GA) in . Biochemistry, 48, 5769–5778 with permission, Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

Large enzyme concentrations of up to 1 mM, and extended reaction times were used in the determination of the small values of the second-order rate constants M–1 s–1 for the catalyzed reactions of phosphodianion truncated substrates. Even then it was not possible to determine the kinetic parameter for unactivated adenylate kinase catalyzed phosphoryl transfer from ATP to phosphite dianion to form isohypophosphate and ADP, because this reaction is much slower than adenylate kinase-catalyzed hydrolysis of ATP to form ADP and phosphate [30]. It may also be necessary to deal with complications that arise from slow enzyme-catalyzed side reactions of SH. For example, the unactivated reaction of ([1-13C]-GA) in D2O gives in addition to the products of TIM-catalyzed reactions at the enzyme active site, the doubly deuterated product [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA [23]. This product forms by nonspecific reaction(s) of this substrate at the protein surface [51].

3.2. Kinetic Analyses.

Apparent third-order rate constant (Scheme 9) for the reaction of truncated substrate (SH) activated by phosphite dianion (HP) were determined by examining the effect of increasing concentration of SH and HP on the apparent first-order rate constants v/[E] for the enzyme-catalyzed reaction of SH, where v is the initial reaction velocity and [E] is the enzyme concentration. This is the rate constant from eq 2 and Scheme 2C, that was described in the earlier discussion of the determination of the intrinsic phosphite dianion binding energy .

Scheme 9.

Kinetic scheme for the activation of phosphodianion truncated substrate (SH) by phosphite dianion (HPO32–), with random binding of SH and HPO32–.

Figure 2 shows representative kinetic data for phosphite dianion (HP) activation of GPDH-catalyzed reduction of the phosphodianion truncated substrate glycolaldehyde () by an enzyme saturated with NADH [26]. The solid lines through the experimental data for reactions at different fixed [SH] show the global non-linear least squares fits of the data to eq 3 derived for Scheme 9, and treating , and as variable parameters. These fits give values of , and M–2 s–1 [26]. By comparison, a value of was determined for the GPDH-catalyzed reaction in the absence of activator [26].

Figure 2.

Dependence of (s–1) for the reduction of GA by NADH (0.2 mM) catalyzed by GPDH at increasing concentrations of phosphite dianion for reactions at different fixed concentrations of GA. Key: (●), 3.6 mM; (○); 3.0 mM; (▲), 2.4 mM; (△), 1.8 mM; (■), 1.2 mM; (▼), 0.6 mM; (◆); 0.3 mM GA. Reprinted with permission from Journal of the American Chemical Society, 137, 1372–1382, Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

| (3) |

Figure 3 shows representative kinetic data for phosphite dianion (HP) activation of glucose-6-phosphate isomerase-catalyzed (PGI) isomerization of SH = xylose to form ribulose, where the initial velocity v was corrected for the small velocity vo for reaction in the absence of phosphite dianion. It was not possible to obtain satisfactory fits the data from Figure 3 to eq 3, because these data do not define the value of KSH for the weakly bound substrate xylose. The solid lines show the fits of kinetic data at different fixed [xylose] to the Michaelis-Menten equation. Figure 4 shows the replot of values of determined at each individual concentration of xylose against [xylose]. The slope of this linear plot is equal to for phosphite dianion activated PGI-catalyzed isomerization of xylose.

Figure 3.

The effect of increasing [HPO32–] on ()/[E] for PGI-catalyzed reactions of different fixed concentrations of D-xylose. Key: (●), 10 mM; (■) 20 mM; (▲) 30 mM; (▼) 40 mm; and (◆) 50 mM D-xylose. Reprinted with permission from Journal of the American Chemical Society, 143, 2694–2698, Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

Figure 4.

The effect of increasing [D-xylose] on the values of from Figure 3 for dianion activation of PGI-catalyzed isomerization of D-xylose. Reprinted with permission from Journal of the American Chemical Society, 143, 2694–2698, Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

The values of determined for phosphite dianion activators correspond to a ground state binding energy of 2–3 kcal/mol. This is much smaller than the 6–8 kcal/mol binding energy expressed at the reaction transition states [26]. The difference is proposed to be equal to the binding energy utilized to drive the unfavorable protein conformational change (Scheme 5) [2, 3, 23]. The xylose and xylonate substrate pieces show no detectable binding (, Figure 4) to enzymes that catalyze the reactions of glucose 6-phosphate or 6-phosphogluconate substrates [7], while values of and 6 mM, respectively were determined for phosphite dianion activated isomerization and hydride transfer reactions of GA catalyzed by TIM and GPDH, respectively [26]. The latter values of may correspond to apparent disassociation constants for breakdown of nonproductive complexes of these enzymes to the hydrated form of glycoaldehyde, which is 94% of the total pool of this compound in water [21].

It is interesting that the many binding interactions between the separated substrate pieces and their enzyme catalysts do not give rise to small disassociation constants KSH or KHP. This reflects the large entropic cost to formation of the individual binary complexes to the pieces. There is a similar entropic cost to the binding of the whole substrate. However, the observed values of for reactions of the whole substrate are much smaller than the disassociation constants and , because the binding interactions with both substrate fragments are expressed at the Michaelis complex to the whole substrate [34].

4. NEW HORIZONS.

Enzymologists typically treat single-substrate enzyme active sites as an organic whole. However, it is useful and informative, for the cases discussed above, to divide these active sites into a catalytic site that carries out chemistry at a small substrate, and an activation site that uses activator binding energy to drive a protein conformational change that traps the truncated substrate in a reactive catalytic cage. There is considerable scope for examining the mechanism by which the interaction between these two sites gives rise to robust enzymatic catalysis.

4.1. Specificity of Activator and Dianion Activation Sites.

The enzyme specificity for catalysis of the reaction of the substrate pieces at these subsites can be determined by following simple protocol. For example, the reactions of phosphodianion truncated substrates (Scheme 7) catalyzed by TIM (proton transfer, Scheme 1A), OMPDC (decarboxylation, Scheme 1B), and by GPDH (hydride transfer, Scheme 1C) are activated by phosphite dianion and by several additional tetrahedral dianions. Table 1 shows the intrinsic binding energies (eq 2) for stabilization of the transition states for unactivated enzyme-catalyzed reactions of phosphodianion truncated substrates (Scheme 7) by structurally homologous tetrahedral dianions [26]. Two trends for the values of reported in Table 1 were noted in the original report of this work [26].

Table 1.

The intrinsic dianion binding energies (eq 2) for stabilization of the transition states for enzyme-catalyzed reactions of phosphodianion truncated substrates by tetrahedral dianions [26]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 137, 1372–1382 with permission, Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

|

Adenylate kinase-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer from ATP to AMP has also been modeled in studies of 1-(β-D-erythrofuranosyl)adenine-activated (EA, Scheme 10) phosphoryl transfer from ATP to phosphite dianion [30]. The catalytic site for this EA-activated reaction accepts phosphite dianion (HP, ), fluorophosphate (FP, ), and phosphate (HOP ) [6]. These results offer unique insight into the steric and electronic effects that govern the reactivity of dianion nucleophiles at the acceptor site for adenylate kinase-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer from ATP [52].

Scheme 10.

Three tetrahedral phosphorus dianions accepted at the catalytic site for EA-activated adenylate kinase-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer from ATP.

4.2. Mechanisms for Enzyme Activation: Insight from Mutagenesis Studies.

Studies on the effect of site-directed amino acid substitutions on enzyme kinetic parameters have provided tremendous insight into the role of these side chains in catalysis at the catalytic and dianion activation subsites for catalysis by OMPDC [40, 50, 53–57], TIM [10, 58–61] and GPDH [19, 62–65]. The results of these studies highlight the mechanistic imperatives for the construction of the dianion activation sites for enzymes that catalyze this diverse set of reactions.

The X-ray crystal structures for TIM (K12) [16, 17], OMPDC (R235) [18] and GPDH (R269) [19] each show a cationic side chain at the enzyme active site, which lies close to the phosphodianion of the respective enzyme-bound substrates. The K12G substitution at TIM [66], the R235A substitution at OMPDC [67], and the R269A substitution at GPDH [65] result in 7.8, 5.6, and 9.1 kcal/mol increases, respectively, in the respective activation barriers to the enzyme-catalyzed reactions of whole substrates.

Each of the side chain cations sits on the protein surface and forms an ion-pair with the buried phosphodianion. The K12G, R235A and R269A substitutions leave gaps at the protein surface. This leads to efficient rescue of catalytic activity, when small molecule side-chain analogs are transferred from solution to these surface gaps. The transition state stabilization by 1.0 M exogenous cation for these mutant enzymes is: K12G TIM, 3.4 kcal/mol by 1.0 M EtNH3+ [68]; R235A OMPDC, 3.0 kcal/mol by 1.0 M guanidine cation [67]; and, R269A GPDH, 6.7 kcal/mol by 1.0 M guanidine cation [65]. These results are consistent with the notion that the dianion activation sites at these enzymes have evolved to enable a strong, focused, interaction between the substrate dianion and a side chain cation. The efficient rescue of the activity of site-directed variants is facilitated by interactions of the excised side chains with other groups at the protein that hold the side chain cation close to the substrate dianion. For example, the K12 side chain of TIM form an ion-pair to the E97 side chain [69], while the R269 side chain of GPDH form a hydrogen bond to the Q295 side chain [63].

Good linear logarithmic linear free energy correlations, with slopes of 1.0–1.1, are observed between the values of for reactions of the whole substrate (Scheme 2A) and for the phosphite dianion activated reactions of the truncated substrate for catalysis by wildtype and a wide range of variant forms of OMPDC [54], TIM [59, 61] or GPDH [63, 70]. These results show that single site-directed amino acid substitutions at these enzymes has essentially the same effect on the activation barriers for reactions of the whole substrate, which is defined by the value of log , and for reactions of the substrate pieces, which is defined by the value of log . They are consistent with the conclusion that the protein-dianion binding interactions are utilized for the sole purpose of holding these catalysts in the reactive closed form (, Scheme 5), and that shows similar reactivity towards catalysis of the reactions of bound whole substrate and substrate pieces.

4.3. Dianion Activation Sites

The dianion binding sites at OMPDC [18], TIM [16, 17], and GPDH [19, 20] were first identified by X-ray crystallographic analysis. These structures did not identify the activating nature of these binding interactions. These were only revealed by the kinetic studies described in this chapter. There is considerable variation in the structures of the dianion binding sites for these three enzymes. However, they share the common property of using the interactions between the protein catalyst and substrate phosphodianion drive a protein conformational change that traps the substrate in a closed protein cage.

OMPDC.

The ligand phosphodianion of OMP bound to OMPDC interacts with the amide side chain of Q215, the phenol side chain of Y217, the guanidine side chain of R235 and backbone amides from G234 and R235 (Figure 5). These interactions trap OMP in a protein cage [43]. The contribution of interactions between the Q215, Y217 and R235 side chains and the substrate phosphodianion was determined by examining the effect of site-directed side chain substitutions on the intrinsic dianion binding energy (eq 1); this was calculated from the ratio of the second-order rate constants for the enzyme-catalyzed reactions or whole and phosphodianion truncated substrates (Scheme 11).

Figure 5.

X-ray crystal structure (PDB entry 1DQX) of yeast OMPDC in a complex with 6-hydroxyuridine 5′-monophosphate that shows three side chains at the dianion activation site that interact with the ligand phosphodianion: Q215, Y217 and R235. Hydrogen bonds to the G234 and R235 backbone amides are also shown. Reprinted with permission from Journal of the American Chemical Society, 136, 10156–10165, Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

Scheme 11.

The protocol for determining the intrinsic phosphodianion binding energy for wildtype and variant OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation reactions from the ratio of second-order rate constants for the enzyme-catalyzed reactions of whole and phosphodianion truncated substrates. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 136, 10156–10165 with permission, Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

Table 2 shows the intrinsic phosphodianion binding energies determined for wildtype and variant (Scheme 11) forms of OMPDC; and, the effect of site-directed substitutions of Q215, Y217 and R235 side chains on = 11.7 kcal/mol for catalysis by the wildtype enzyme [54]. The Q215, Y217 and R235 side chains are found to contribute 1.7, 1.9 and 5.5 kcal/mol to the total 11.7 kcal/mol total intrinsic dianion binding energy of substrate OMP. The 10.2 kcal/mol effect of the triple Q215A/Y217F/R235A substitution on is only 1.1 kcal/mol larger than the sum of the effects of the three single substitutions (9.1 kcal/mol). These results show that any single substitution has only a small effect on the remaining side chain-dianion interactions and are consistent with the conclusion that single substitutions do not cause large changes in the structure of the dianion activation site at OMPDC.

Table 2.

Intrinsic Phosphodianion Binding Energies for Wildtype and Variant Forms of OMPDC and the Effects of these Amino Acid Substitutions on the Intrinsic Phosphodianion Binding Energy (eq 1).a

| OMPDC | (eq 1) | (kcal/mol) eq 1 | − (kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 4.2 x 108 | 11.7 | ||

| Q215A | 2.3 x 107 | 10.0 | 1.7 | |

| Y217F | 1.5 x 107 | 9.8 | 1.9 | |

| R235A | 3.5 x 104 | 6.2 | 5.5 | |

| Q215A/Y217F | 7.4 x 105 | 8.0 | 3.7 | |

| Q215A/ R235A | 3300 | 4.8 | 6.9 | |

| Y217F /R235A | 410 | 3.6 | 8.1 | |

| Q215A/Y217F/R235A | 12 | 1.5 | 10.2 | |

Data from [54].

The data from Table 2 provide direct evidence that the side chains at the OMPDC dianion binding site promote decarboxylation at the 10 Å distant catalytic site by providing 12 kcal/mol of binding energy to stabilize the active closed enzyme conformation. The observation that these substitutions cause no more than a small decrease in for decarboxylation of the phosphodianion-truncated substrate shows that there is little direct interaction between these side chains and the decarboxylation transition state [71].

OMPDC provides only a ca 9 kcal/mol stabilization of the transition state for decarboxylation of the simple base orotidine. This shows that interactions of the protein with the nonreacting substrate pieces of OMP account for 22 of the total 31 kcal/mol stabilization of the transition state for OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of OMP [50]. We have documented additional stabilization of the active closed enzyme by an interaction between the S154 side chain at the pyrimidine umbrella loop and Q215 [57, 72]; and, by interactions of protein side chains with the ribosyl hydroxy groups [56, 73, 74].

TIM.

X-ray crystal structures for unliganded TIM and for complexes between TIM and substrate or transition state analogs show that the phosphodianion driven conformational change results in a ca 2 Å movement of the carboxylate side-chain of E165 towards the acidic α-carbonyl carbon that is deprotonated by E165 [16, 17, 25, 75]. The effect of site-directed substitutions of two different types of side chains that participate in this conformational change have been probed: (a) Side chains in flexible loop 7 that act directly to stabilize the loop-closed form of TIM [59–61]; (b) Side chains from flexible loop 6 that move during the ligand-driven conformational change [58, 76]. The most important conclusion from these studies is that the dianion driven conformational change functions to induce a large increase in the basicity of the carboxylate side chain of E165. This promotes abstraction of the weakly acidic α-carbonyl proton of substrate in the first step for the TIM-catalyzed isomerization reaction [77, 78].

The L230A mutation at TIM from Trypanosoma brucei brucei results in a 6-fold decrease in for TIM-catalyzed isomerization of whole substrate, but a 17-fold increase in for TIM-catalyzed deprotonation of the truncated substrate piece GA [79]. This result is surprising because other substitutions of active site side chains at TIM result in a decrease in and either a decrease or no change in [58–61]. The phosphodianion driven conformational change of TIM forces the E165 side chain to lie between the hydrophobic side chains of I170 and L230 [75]. This favors the increase in the basicity of the E165 side chain described above. We proposed that this conformational change introduces a destabilizing steric interaction between the L232 and E165 side chains at the closed enzyme, and that relief of this interaction at the L230A variant results in a ca. 1.7 kcal/mol stabilization of a catalytically active loop-closed form of TIM (, Scheme 5) relative to an inactive open form (). The result is a 17-fold increase in the fraction of TIM present in the active loop-closed form and in for deprotonation of GA. A different effect of the L230A substitution on for TIM-catalyzed isomerization of whole substrate is observed. The rate-determining step for this reaction is diffusion-controlled formation or breakdown of Michaelis complexes to GAP, and the rate of this step is not controlled by the stability of [80].

GPDH.

The architecture of the dianion activation site for GPDH [62] is different from that for OMPDC and TIM (Figure 6). The phosphodianion of DHAP bound to GPDH shows a strong ion-pairing interaction with the side-chain cation from R269 [65], and a weaker hydrogen bond to the amide side chain of N270 [81]. The R269 side chain is held over the dianion by a hydrogen bond to the amide side chain of Q295 [63]. The elimination of this interaction at several Q295 variants results in up to a 3 kcal/mol decrease in the transition state stabilization from the interaction between the R269 side chain and the phosphodianion of DHAP [63].

Figure 6.

Representation of the X-ray crystal structure of the non-productive ternary complex between GPDH, NAD, and DHAP (PDB 6E90). This shows the R269 and N270 side chains that interact with the phosphodianion of DHAP. The Q295 side chain at a flexible loop interacts with the R269 side chain to hold the side chain close to the DHAP phosphodianion. Reprinted with permission from Biochemistry, 61, 856–867, Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

5. CONCLUSIONS

It has been less than 20 years since the report of the recovery of the reactivity of the whole substrate OMP in the reaction of the EO and phosphite dianion pieces [28], and less than 15 years since the proposal of the induced-fit model to rationalize the high reactivity of GA and phosphite dianion pieces in the reaction catalyzed by triosephosphate isomerase [3, 23]. In recent years we have reported many other examples of enzyme-catalyzed reactions, where the reactivity of the whole substrate is recovered in the reactivity of well-chosen substate pieces by a mechanism where the piece derived from the nonreactive substrate handle activates the enzyme for catalysis of reaction of the second piece. This work has focused on studies of metabolic enzymes, which we have proposed owe their impressive catalytic proficiency to the evolution of mechanisms that incorporate induced-fit type ligand-driven conformational changes into the catalytic cycle [3]. The scope of this reaction mechanism has not yet been fully documented by experiments to examine the role of enzyme-conformational changes in enzyme catalysis. We hope that the methods described in this chapter will be adopted in other laboratories interested in determining the breadth of enzyme-activating substrate-driven conformational changes.

Acknowledgement.

We are grateful to the US National Institutes of Health Grants GM134881, GM116921 and GM039754 for generous support of our work.

REFERENCES

- [1].Pauling L, The nature of forces between large molecules of biological interest., Nature 161 (1948) 707–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Amyes TL, Richard JP, Specificity in transition state binding: The Pauling model revisited, Biochemistry 52(12) (2013) 2021–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Richard JP, Enabling Role of Ligand-Driven Conformational Changes in Enzyme Evolution, Biochemistry 61(15) (2022) 1533–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Richard JP, Protein Flexibility and Stiffness Enable Efficient Enzymatic Catalysis., J. Am. Chem. Soc 141 (2019) 3320–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Amyes TL, Malabanan MM, Zhai X, Reyes AC, Richard JP, Enzyme Activation Through the Utilization of Intrinsic dianion binding energy, Prot. Eng., Des. & Sel 30(3) (2017) 157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fernandez PL, Richard JP, Adenylate Kinase-Catalyzed Reactions of AMP in Pieces: Specificity for Catalysis at the Nucleoside Activator and Dianion Catalytic Sites, Biochemistry 61(23) (2022) 2766–2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fernandez PL, Nagorski RW, Cristobal JR, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Phosphodianion Activation of Enzymes for Catalysis of Central Metabolic Reactions, J. Am. Chem. Soc 143 (2021) 2694–2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Westheimer FH, Why Nature Chose Phosphates, Science 235 (1987) 1173–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fothergill-Gilmore LA, Michels PAM, Evolution of Glycolysis, Prog. Biophys. Molec. Biol 59 (1993) 105–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Akram M, Ali Shah SM, Munir N, Daniyal M, Tahir IM, Mahmood Z, Irshad M, Akhlaq M, Sultana S, Zainab R, Hexose monophosphate shunt, the role of its metabolites and associated disorders: A review, Journal of Cellular Physiology 234(9) (2019) 14473–14482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Whitty A, Fierke CA, Jencks WP, Role of binding energy with coenzyme A in catalysis by 3-oxoacid coenzyme A transferase, Biochemistry 34 (1995) 11678–11689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Moore SA, Jencks WP, Formation of active site thiol esters of CoA transferase and the dependence of catalysis on specific binding interactions, J. Biol. Chem 257 (1982) 10893–10897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Stryer L, Biochemistry (Fouth edition), W.H. Freeman and Company., New York, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jencks WP, Binding energy, specificity, and enzymic catalysis: the Circe effect, Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol 43 (1975) 219–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Richard JP, Amyes TL, Reyes AC, Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Probing the Limits of the Possible for Enzyme Catalysis., Acc. Chem. Res 51 (2018) 960–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Davenport RC, Bash PA, Seaton BA, Karplus M, Petsko GA, Ringe D, Structure of the triosephosphate isomerase-phosphoglycolohydroxamate complex: an analog of the intermediate on the reaction pathway, Biochemistry 30(24) (1991) 5821–5826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lolis E, Petsko GA, Crystallographic analysis of the complex between triosephosphate isomerase and 2-phosphoglycolate at 2.5-Å resolution: implications for catalysis, Biochemistry 29(28) (1990) 6619–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Miller BG, Hassell AM, Wolfenden R, Milburn MV, Short SA, Anatomy of a proficient enzyme: the structure of orotidine 5'-monophosphate decarboxylase in the presence and absence of a potential transition state analog, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci 97(5) (2000) 2011–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mydy LS, Cristobal J, Katigbak R, Bauer P, Reyes AC, Kamerlin SCL, Richard JP, Gulick AM, Human Glycerol 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase: X-Ray Crystal Structures that Guide the Interpretation of Mutagenesis Studies., Biochemistry 58 (2019) 1061–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ou X, Ji C, Han X, Zhao X, Li X, Mao Y, Wong L-L, Bartlam M, Rao Z, Crystal structures of human glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 (GPD1), Journal of Molecular Biology 357(3) (2006) 858–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Amyes TL, Richard JP, Enzymatic catalysis of proton transfer at carbon: activation of triosephosphate isomerase by phosphite dianion, Biochemistry 46 (2007) 5841–5854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Amyes TL, O'Donoghue AC, Richard JP, Contribution of phosphate intrinsic binding energy to the enzymatic rate acceleration for triosephosphate isomerase, J. Am. Chem. Soc 123(45) (2001) 11325–11326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Go MK, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Hydron Transfer Catalyzed by Triosephosphate Isomerase. Products of the Direct and Phosphite-Activated Isomerization of [1-13C]-Glycolaldehyde in D2O, Biochemistry 48(24) (2009) 5769–5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Richard JP, A Paradigm for Enzyme-Catalyzed Proton Transfer at Carbon: Triosephosphate Isomerase, Biochemistry 51 (2012) 2652–2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wierenga RK, Triosephosphate isomerase: a highly evolved biocatalyst, Cell. Mol. Life Sci 67(23) (2010) 3961–3982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Reyes AC, Zhai X, Morgan KT, Reinhardt CJ, Amyes TL, Richard JP, The Activating Oxydianion Binding Domain for Enzyme-Catalyzed Proton Transfer, Hydride Transfer and Decarboxylation: Specificity and Enzyme Architecture, J. Am. Chem. Soc 137 (2015) 1372–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Goryanova B, Amyes TL, Gerlt JA, Richard JP, OMP Decarboxylase: Phosphodianion Binding Energy Is Used To Stabilize a Vinyl Carbanion Intermediate, J. Am. Chem. Soc 133(17) (2011) 6545–6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Amyes TL, Richard JP, Tait JJ, Activation of orotidine 5'-monophosphate decarboxylase by phosphite dianion: The whole substrate is the sum of two parts, J. Am. Chem. Soc 127(45) (2005) 15708–15709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tsang W-Y, Amyes TL, Richard JP, A Substrate in Pieces: Allosteric Activation of Glycerol 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (NAD+) by Phosphite Dianion, Biochemistry 47(16) (2008) 4575–4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fernandez PL, Richard JP, Adenylate Kinase-Catalyzed Reaction of AMP in Pieces: Enzyme Activation for Phosphoryl Transfer to Phosphite Dianion, Biochemistry 60 (2021) 2672–2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fierke CA, Jencks WP, Two functional domains of coenzyme A activate catalysis by coenzyme A transferase. Pantetheine and adenosine 3'-phosphate 5'-diphosphate, J. Biol. Chem 261 (1986) 7603–7606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kerns SJ, Agafonov RV, Cho Y-J, Pontiggia F, Otten R, Pachov DV, Kutter S, Phung LA, Murphy PN, Thai V, Alber T, Hagan MF, Kern D, The energy landscape of adenylate kinase during catalysis, Nature 22(2) (2015) 124–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Berry MB, Phillips GN Jr., Crystal structures of Bacillus stearothermophilus adenylate kinase with bound Ap5A, Mg2+ Ap5A, and Mn2+ Ap5A reveal an intermediate lid position and six coordinate octahedral geometry for bound Mg2+ and Mn2+, Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet 32(3) (1998) 276–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jencks WP, On the attribution and additivity of binding energies, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci 78(7) (1981) 4046–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kulkarni YS, Liao Q, Byléhn F, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Kamerlin SCL, Role of Ligand-Driven Conformational Changes in Enzyme Catalysis: Modeling the Reactivity of the Catalytic Cage of Triosephosphate Isomerase., J. Am. Chem. Soc 140 (2018) 3854–3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Porter DJT, Short SA, Yeast Orotidine-5'-Phosphate Decarboxylase: Steady-State and Pre-Steady-State Analysis of the Kinetic Mechanism of Substrate Decarboxylation, Biochemistry 39(38) (2000) 11788–11800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Thomas JA, Koshland DE Jr., Competitive inhibition by substrate during enzyme action. Evidence for the induced-fit theory, J. Am. Chem. Soc 82 (1960) 3329–33. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Koshland DE Jr., Application of a Theory of Enzyme Specificity to Protein Synthesis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 44 (1958) 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sievers A, Wolfenden R, The effective molarity of the substrate phosphoryl group in the transition state for yeast OMP decarboxylase, Bioorg. Chem 33(1) (2005) 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Goryanova B, Spong K, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Catalysis by Orotidine 5'-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: Effect of 5-Fluoro and 4'-Substituents on the Decarboxylation of Two-Part Substrates, Biochemistry 52(3) (2013) 537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Warshel A, Sharma PK, Kato M, Xiang Y, Liu H, Olsson MHM, Electrostatic basis for enzyme catalysis, Chem. Rev 106(8) (2006) 3210–3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Warshel A, Electrostatic Origin of the Catalytic Power of Enzymes and the Role of Preorganized Active Sites, J. Biol. Chem 273(42) (1998) 27035–27038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Richard JP, Amyes TL, Goryanova B, Zhai X, Enzyme architecture: on the importance of being in a protein cage, Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 21(0) (2014) 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ray WJ Jr., Long JW, Owens JD, An analysis of the substrate-induced rate effect in the phosphoglucomutase system, Biochemistry 15(18) (1976) 4006–4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Miller BG, Wolfenden R, Catalytic proficiency: the unusual case of OMP decarboxylase, Ann. Rev. Biochem 71 (2002) 847–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Noda L, Adenosine Triphosphate-Adenosine Monophosphate Transphosphorylase III. Kinetic Studies, J. Biol. Chem 232(1) (1958) 237–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Zeleznikar RJ, Heyman RA, Graeff RM, Walseth TF, Dawis SM, Butz EA, Goldberg ND, Evidence for compartmentalized adenylate kinase catalysis serving a high energy phosphoryl transfer function in rat skeletal muscle, J. Biol. Chem 265(1) (1990) 300–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kerns SJ, Agafonov RV, Cho Y-J, Pontiggia F, Otten R, Pachov DV, Kutter S, Phung LA, Murphy PN, Thai V, Alber T, Hagan MF, Kern D, The energy landscape of adenylate kinase during catalysis, Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 22(2) (2015) 124–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Henzler-Wildman KA, Lei M, Thai V, Kerns SJ, Karplus M, Kern D, A hierarchy of timescales in protein dynamics is linked to enzyme catalysis, Nature 450(7171) (2007) 913–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Reyes AC, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: Erection of Active Orotidine 5'-Monophosphate Decarboxylase by Substrate-Induced Conformational Changes., J. Am. Chem. Soc 139 (2017) 16048–16051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Go MK, Malabanan MM, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Bovine Serum Albumin-Catalyzed Deprotonation of [1-13C]Glycolaldehyde: Protein Reactivity toward Deprotonation of the α-Hydroxy α-Carbonyl Carbon, Biochemistry 49(35) (2010) 7704–7708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lassila JK, Zalatan JG, Herschlag D, Biological Phosphoryl-Transfer Reactions: Understanding Mechanism and Catalysis, Ann. Rev. Biochem 80(1) (2011) 669–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Goryanova B, Goldman LM, Ming S, Amyes TL, Gerlt JA, Richard JP, Rate and Equilibrium Constants for an Enzyme Conformational Change during Catalysis by Orotidine 5’-Monophosphate Decarboxylase, Biochemistry 54(29) (2015) 4555–4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Goldman LM, Amyes TL, Goryanova B, Gerlt JA, Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: Deconstruction of the Enzyme-Activating Phosphodianion Interactions of Orotidine 5'-Monophosphate Decarboxylase, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136(28) (2014) 10156–10165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Goryanova B, Goldman LM, Amyes TL, Gerlt JA, Richard JP, Role of a Guanidinium Cation–Phosphodianion Pair in Stabilizing the Vinyl Carbanion Intermediate of Orotidine 5’-Phosphate Decarboxylase-Catalyzed Reactions, Biochemistry 52(42) (2013) 7500–7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Cristobal JR, Brandão TAS, Reyes AC, Richard JP, Protein–Ribofuranosyl Interactions Activate Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase for Catalysis, Biochemistry 60(45) (2021) 3362–3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Reyes AC, Plache DC, Koudelka AP, Amyes TL, Gerlt JA, Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: Breaking Down the Catalytic Cage that Activates Orotidine 5′-Monophosphate Decarboxylase for Catalysis., J. Am. Chem. Soc 140 (2018) 17580–17590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Richard JP, Amyes TL, Malabanan MM, Zhai X, Kim KJ, Reinhardt CJ, Wierenga RK, Drake EJ, Gulick AM, Structure–Function Studies of Hydrophobic Residues That Clamp a Basic Glutamate Side Chain during Catalysis by Triosephosphate Isomerase, Biochemistry 55(21) (2016) 3036–3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhai X, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Role of Loop-Clamping Side Chains in Catalysis by Triosephosphate Isomerase, J. Am. Chem. Soc 137(48) (2015) 15185–15197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Zhai X, Go MK, Donoghue AC, Amyes TL, Pegan SD, Wang Y, Loria JP, Mesecar AD, Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: The Effect of Replacement and Deletion Mutations of Loop 6 on Catalysis by Triosephosphate Isomerase, Biochemistry 53(21) (2014) 3486–3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Zhai X, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: Remarkably Similar Transition States for Triosephosphate Isomerase-Catalyzed Reactions of the Whole Substrate and the Substrate in Pieces, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136 (2014) 4145–4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Cristobal JR, Reyes AC, Richard JP, The Organization of Active Site Side Chains of Glycerol-3-phosphate Dehydrogenase Promotes Efficient Enzyme Catalysis and Rescue of Variant Enzymes., Biochemistry 59 (2020) 1582–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Richard JP, He R, Reyes AC, Amyes TL, Reyes AC, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: The Role of a Flexible Loop in Activation of Glycerol-3-phosphate Dehydrogenase for Catalysis of Hydride Transfer, Biochemistry 57(23) (2018) 3227–3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Reyes AC, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: Self-Assembly of Enzyme and Substrate Pieces of Glycerol-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase into a Robust Catalyst of Hydride Transfer, J. Am. Chem. Soc 138 (2016) 15251–15259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Reyes AC, Koudelka AP, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: Optimization of Transition State Stabilization from a Cation–Phosphodianion Pair, J. Am. Chem. Soc 137(16) (2015) 5312–5315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Go MK, Koudelka A, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Role of Lys-12 in Catalysis by Triosephosphate Isomerase: A Two-Part Substrate Approach, Biochemistry 49(25) (2010) 5377–5389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Barnett SA, Amyes TL, Wood MB, Gerlt JA, Richard JP, Activation of R235A Mutant Orotidine 5'-Monophosphate Decarboxylase by the Guanidinium Cation: Effective Molarity of the Cationic Side Chain of Arg-235, Biochemistry 49(5) (2010) 824–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Go MK, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Rescue of K12G mutant TIM by NH4+ and alkylammonium cations: The reaction of an enzyme in pieces, J. Am. Chem. Soc 132 (2010) 13525–13532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Chang TC, Park JH, Colquhoun AN, Khoury CB, Seangmany NA, Schwans JP, Evaluating the Catalytic Importance of a Conserved Glu97 Residue in Triosephosphate Isomerase., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 505 (2018) 492–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Richard JP, Cristobal JR, Amyes TL, Linear Free Energy Relationships for Enzymatic Reactions: Fresh Insight from a Venerable Probe, Acc. Chem. Res 54(10) (2021) 2532–2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Amyes TL, Ming SA, Goldman LM, Wood BM, Desai BJ, Gerlt JA, Richard JP, Orotidine 5'-monophosphate decarboxylase: Transition state stabilization from remote protein-phosphodianion interactions, Biochemistry 51 (2012) 4630–4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Barnett SA, Amyes TL, Wood BM, Gerlt JA, Richard JP, Dissecting the Total Transition State Stabilization Provided by Amino Acid Side Chains at Orotidine 5'-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: A Two-Part Substrate Approach., Biochemistry 47(30) (2008) 7785–7787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Miller BG, Butterfoss GL, Short SA, Wolfenden R, Role of Enzyme-Ribofuranosyl Contacts in the Ground State and Transition State for Orotidine 5'-Phosphate Decarboxylase: A Role for Substrate Destabilization?, Biochemistry 40(21) (2001) 6227–6232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Brandão TAS, Richard JP, Orotidine 5'-Monophosphate Decarboxylase: The Operation of Active Site Chains Within and Across Protein Subunits, Biochemistry 59(21) (2020) 2032–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Kursula I, Wierenga RK, Crystal structure of triosephosphate isomerase complexed with 2-phosphoglycolate at 0.83-Å resolution, J. Biol. Chem 278(11) (2003) 9544–9551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Malabanan MM, Koudelka AP, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Mechanism for Activation of Triosephosphate Isomerase by Phosphite Dianion: The Role of a Hydrophobic Clamp, J. Am. Chem. Soc 134 (2012) 10286–10298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Zhai X, Reinhardt CJ, Malabanan MM, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: Amino Acid Side-Chains That Function To Optimize the Basicity of the Active Site Glutamate of Triosephosphate Isomerase, J. Am. Chem. Soc 140(26) (2018) 8277–8286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Malabanan MM, Nitsch-Velasquez L, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Magnitude and origin of the enhanced basicity of the catalytic glutamate of triosephosphate isomerase, J. Am. Chem. Soc 135(16) (2013) 5978–5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Malabanan MM, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Mechanism for Activation of Triosephosphate Isomerase by Phosphite Dianion: The Role of a Ligand-Driven Conformational Change, J. Am. Chem. Soc 133(41) (2011) 16428–16431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Blacklow SC, Raines RT, Lim WA, Zamore PD, Knowles JR, Triosephosphate isomerase catalysis is diffusion controlled, Biochemistry 27(4) (1988) 1158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Reyes AC, Amyes TL, Richard JP, Enzyme Architecture: A Startling Role for Asn270 in Glycerol 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase-Catalyzed Hydride Transfer, Biochemistry 55(10) (2016) 1429–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]