Abstract

Background: Quality strategies, interventions, and frameworks have been developed to facilitate a better understanding of healthcare systems. Reporting adverse events is one of these strategies. Gynaecology and obstetrics are one of the specialties with many adverse events. To understand the main causes of medical errors in gynaecology and obstetrics and how they could be prevented, we conducted this systematic review. Methods: This systematic review was performed in compliance with the Prisma 2020 guidelines. We searched several databases for relevant studies (Jan 2010–May 2023). Studies were included if they indicated the presence of any potential risk factor at the hospital level for medical errors or adverse events in gynaecology or obstetrics. Results: We included 26 articles in the quantitative analysis of this review. Most of these (n = 12) are cross-sectional studies; eight are case–control studies, and six are cohort studies. One of the most frequently reported contributing factors is delay in healthcare. In addition, the availability of products and trained staff, team training, and communication are often reported to contribute to near-misses/maternal deaths. Conclusions: All risk factors that were found in our review imply several categories of contributing factors regarding: (1) delay of care, (2) coordination and management of care, and (3) scarcity of supply, personnel, and knowledge.

Keywords: medical errors, adverse events, gynaecology and obstetrics, healthcare quality, safety, systematic review, medical record review

1. Introduction

Much research is performed on ‘quality of healthcare’. Most recent definitions of ‘quality of healthcare’ are provided by the European Commission and the World Health Organization (WHO) [1,2,3]. Both the European Commission and the WHO describe ‘quality of care’ as the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes, working from evidence-based professional knowledge. Quality services should, according to the European Commission and WHO, be effective, safe, and people-centered and, therefore, must be timely, equitable, integrated, and efficient.

A broad range of quality strategies, interventions and frameworks have been developed with the aim of facilitating a better understanding of health systems and improving the quality of healthcare. The strategies can be summarized into (1) system-level strategies, (2) institutional/organizational strategies, and (3) patient-level strategies [4]. One broadly implemented strategy at the organizational level is reporting adverse events [5]. Often, adverse events function as a starting point for root cause analysis to identify direct and indirect causes of safety incidents [6]. These definitions and strategies presume a relation between ‘quality’, ‘safety’, and ‘risk’ of occurring ‘medical errors’.

An adverse event is defined as an unwanted outcome of (delayed/lacked) medical treatment. Adverse events and medical errors imply that a person, situation, system, or a combination of these factors has caused health damage [7]. The “Harvard medical practice” study found that 3.7% of all hospital admissions led to adverse events, while the “quality in Australian healthcare study” identified adverse events in 16.6% of admissions. Half of these adverse events were preventable [8]. Recent data from Liu et al. showed that the highest numbers of adverse events are seen in the medical specialties: general surgery, orthopaedics, and obstetrics/gynaecology [9].

To understand the main causes of medical errors in gynaecology and obstetrics, how they can be prevented, and how the quality of care can be improved, we conducted a systematic review. The goal of this review was to identify the direct and indirect causes of medical errors and mistakes related to one of the top three medical specialties, obstetrics and gynaecology, due to the high number of adverse events and the potential high impact of adverse events in this specialty. Understanding the direct and indirect causes of medical errors can lead to improvements in the quality of care.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search

This systematic literature search was electronically performed for relevant studies in PubMed, EMBASE, web of knowledge and the Cochrane Library. For this search strategy, the following MeSH- and non-MeSH terms were used: medical error, medical mistake, adverse event, risk management, health care quality assessment, health care quality, access, evaluation, gynaecology and/or obstetric. The following limits were added to these terms: full text, 2010–2023, language restriction in Dutch and English, and the presence of gynaecology and/or obstetrics in the title or the abstract. Since maternal care was part of the millennium development goals report in 2010 and the increased attention on maternal care ever since, we limited our search to the period from 2010 until 2023. The researchers MR and DoK have performed all searches. The final search was performed on 11 May 2023. For the specific search terms, including used limits and the number of articles for each database, see Appendix A. The systematic review was performed respecting the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [10].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

All included articles indicate the presence of any potential risk factor at the hospital level for medical errors or adverse events in gynaecology or obstetrics. Only full articles were included. Letters, abstracts and review studies were excluded. All articles that did not contain information about the cause of medical errors or adverse events or articles exclusively describing patient-related risk factors were excluded from this literature review.

2.3. Study Selection

After completion of the search, all articles were independently screened on title by two researchers (DeK, MR). Disagreements at this stage were dealt with by discussion and consensus. If disagreement was maintained, a third independent researcher (DoK) was involved in the final decision. After the completion of screening on the title, the remaining articles were further analyzed on the abstract and full text by the same three authors (DeK, DoK, MR).

2.4. Data Extraction

The included articles were analyzed on the title, author, year of publication, study setting, study design, study population, study size, results, factors, and conclusion. After completion of the extracted data, this information was clustered in a summary of findings table (Supplementary table). Data extraction was conducted by all three authors separately (DeK, DoK, MR). All articles were analyzed using the Prisma checklist [10]. Again, disagreements were dealt with by discussion and consensus. In order to provide an overview of the factors contributing to adverse events, near-misses and medical mistakes, results were summarized per category according to the framework provided by Tello et al. (2020) [11].

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Search and Study Selection

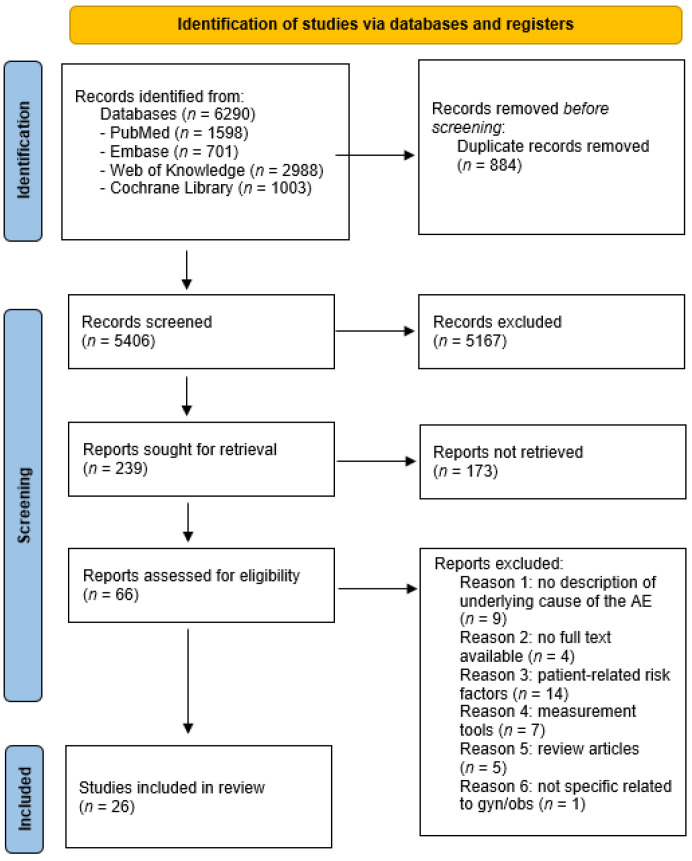

After completing the search, 6290 articles were identified before deduplication. Following manual and automatic deduplication (N = 884), 5406 articles remained for further analysis. After screening the title, 239 records remained for further analysis on the abstract. After reviewing the abstracts, an additional 173 articles were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. A total of 66 full-text articles were independently analyzed by three researchers (DeK, DoK, MR) for eligibility, resulting in 26 articles for quantitative analysis in this review. A flowchart and an overview of all exclusion details can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature search and selection of studies.

3.2. Quality Criteria

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the criteria developed by Worster et al. for assessing the quality of MRR studies [12]. Quality assessment was performed in duplicate by DeK and DoK. The assessment used rating categories of “present” or “missing”, which were transformed into 1’s and 0’s and added together for a score between 1 and 15. Studies with scores between 0 and 5 were considered weak; those with scores between 6 and 10 were deemed reasonable, and studies with scores between 11 and 15 were classified as good. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Quality assessment of included studies [12]. 1 = Present, 0 = missing.

| Abstractors Training | Selection Criteria | Variable Definition | Abstraction Forms | Performance Monitored | Blind to Hypothesis | IRR * Mentioned | IRR * Tested | MR Identified | Sampling Method | Missing Data Management | Institutional Review Board | Total Score |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aibar [13] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Aikpitanyi [14] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Benimana [15] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Carvalho [16] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| David [17] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Florea [18] | No MRR, criteria inapplicable | ||||||||||||

| Habte [19] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| Hadad [20] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Huner [21] | No MRR, criteria inapplicable | ||||||||||||

| Iwuh [22] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Jensen [23] | No MRR, criteria inapplicable | ||||||||||||

| Johansen [24] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Johansen [25] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Kalisa [26] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Kasahun [27] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Kulkarni [28] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Mahmood [29] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Mawarti [30] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Mulongo [31] | No MRR, criteria inapplicable | ||||||||||||

| Nassoro [32] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Neogi [33] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Saucedo [34] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Sayinzoga [35] | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Sorensen [36] | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Wasim [37] | No MRR, criteria inapplicable | ||||||||||||

| Zewde [38] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

* Inter observer reliability.

3.3. Included Studies

Patient populations or clinical conditions that were studied included pregnant and postpartum women (within 42 days of termination of pregnancy) admitted to the obstetric department and also maternal near-miss and maternal death cases. The studies that were included varied in study center extent and study size (1 hospital versus nationwide inclusion; sample sizes varied between 18 and 27,916). The studies were performed in 18 different countries (see Supplementary table).

Most of the studies were cross-sectional studies (n = 12), case–control studies (n = 8) or cohorts (n = 6). 21/26 studies were based on medical record reviews. All studies were quantitative studies except two, which combined qualitative and quantitative research by means of interviews with healthcare professionals and patients. Table 1 shows the quality assessment of the included articles, which were considered weak (N = 9) and reasonable (N = 12) quality. For five articles, the criteria were not applicable.

3.4. Definitions

Only seventeen of the twenty-six articles explicitly stated a definition of the patient population or clinical conditions that were included and/or the outcome that was measured (for example, ‘adverse event’ or ‘maternal near-miss’). If provided, definitions varied between these articles. In 12 articles, the WHO definitions and criteria were followed. The WHO defines an adverse event as an injury related to medical management, in contrast to complications of a disease. Most studies include cases of maternal near-misses, which is defined by the WHO as ‘a woman who nearly died but survived a complication that occurred during pregnancy, childbirth or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy’ [39]. Both adverse events and maternal near-misses may be preventable or non-preventable. Table 2 provides an overview of definitions used in the included articles.

Table 2.

Terms and definitions used in each article.

| Author | Terms Used | Definition Used |

|---|---|---|

| Aibar [13] | Patient safety incident | Any event or circumstance that caused or could have caused unnecessary harm to a patient. |

| No harm incident | Any unforeseen and unexpected event recorded in the medical record that did not cause harm to the patient but which, under different circumstances, could have been an accident or an event that, if not discovered or corrected in time, could imply problems for the patient. | |

| Adverse event | Any unforeseen and unexpected accident recorded in the medical record that caused injury and/or disability and/or prolonged the hospital stay and/or led to death, which was the result of health care and not the patient’s underlying condition. | |

| Aikpitanyi [14] | Maternal death | No definition provided |

| Benimana [15] | Maternal near-miss | Refers to WHO criteria |

| Maternal deaths | Refers to WHO criteria | |

| Carvalho [16] | Three delays | Refers to WHO criteria |

| David [17] | Near-miss cases | Refers to clinical criteria for identification of near-miss (e.g., eclampsia, severe hemorrhage, severe sepsis, uterine rupture and severe malaria). |

| Florea [18] | Averse events | No definition provided |

| Incidents | No definition provided | |

| Near-misses | No definition provided | |

| Habte [19] | Maternal near-miss | Refers to WHO criteria |

| Haddad [20] | Severe maternal morbidity | Refers to WHO criteria |

| Hüner [21] | Adverse events | A catalogue of criteria or events was developed based on international research findings from scientific studies in two project meetings and interprofessional focus groups. |

| Iwuh [22] | Maternal near-miss | Refers to WHO criteria |

| Jensen [23] | Adverse health outcomes | No definition provided |

| Clinical performance | TeamOBS-PPH score | |

| Johansen [24] | Adverse events | No definition provided |

| Serious outcomes | No definition provided | |

| Serious adverse events | An injury was regarded as serious when it had serious consequences on the patient’s disease or disorder; or if it caused serious pain or reduced self-realization in the short or long term | |

| Johansen [25] | Serious adverse events | Three categories were described (birth asphyxia, shoulder dystocia and severe PPH) |

| Adequate obstetric care | Healthcare is in accordance with clinical practice based on Norwegian national and local obstetric guidelines. | |

| Kalisa [26] | Maternal near-miss | Refers to WHO criteria: a woman who almost died but survived a complication during pregnancy, childbirth or within 42 days after the termination of pregnancy. |

| Severe maternal outcome | Maternal near-miss and maternal deaths combined | |

| Kasahun [27] | Maternal near-miss/severe maternal morbidity | Refers to WHO criteria and states that the terms maternal near-miss and severe maternal morbidity are used interchangeably.Operational definition: maternal near-misses (severe maternal morbidity) is women who are admitted with either of the following obstetric diagnoses: severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, severe hemorrhage, dystocia (defined in the current study as uterine rupture, impending uterine rupture like prolonged labor with previous cesarean section, and emergency C/S delivery), severe anemia (<6), sepsis (puerperal sepsis, chorioamnionitis and septic abortion). |

| Kulkarni [28] | Near-miss obstetric event | Refers to WHO criteria. Near-miss obstetric event concerns a woman who nearly died as a result of a complication that occurred during pregnancy, childbirth or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy. Clinical criteria near-miss events were defined as any near-miss event related to a specific disease entity, while management-based near-miss events and organ-system dysfunction-based near-miss events were defined according to the near-miss approach outlined by WHO. |

| Mahmood [29] | Maternal deaths | No definition described |

| Mawarti [30] | Maternal deaths | Refers to WHO criteria |

| Maternal near-miss | Refers to WHO criteria | |

| Mulongo [31] | Maternal near-miss | Refers to WHO criteria |

| Nassoro [32] | Maternal deaths that occurred due to haemorrhage | No definition described |

| Neogi [33] | Stillbirths | Any baby born dead after the 24th week of pregnancy. |

| Saucedo [34] | Pregnancy-associated deaths | All deaths of women while pregnant or within one year of the termination of pregnancy, regardless of the cause of death. |

| Sayinzoga [35] | Maternal deaths | No definition described |

| Sorensen [36] | Maternal death | No definition described |

| Wasim [37] | Maternal deaths | Refers to WHO criteria |

| Maternal near-miss | Refers to WHO criteria | |

| Zewde [38] | Severe maternal outcome | Combination of maternal deaths and maternal near-miss |

| Maternal near-miss | Refers to WHO criteria |

3.5. Findings

Most of the included studies (n = 21) were medical record reviews. All studies except two were quantitative studies. These combined qualitative and quantitative research by means of interviews with healthcare professionals and patients. All studies were related to obstetric care and maternal near-misses. Supplementary table provides a summary of the findings table of all included studies.

In 25/26 studies, cases of maternal or neonatal near-misses, maternal deaths, or adverse events were selected using different definitions and selection criteria. After selection, a retrospective (medical record) review was performed by an internal and/or external committee. Most studies provide an overview of factors that contributed to the near-misses, maternal deaths or adverse events. One of the most commonly reported factors is delay in healthcare. In addition, availability of products (such as medication and blood products), availability of trained staff, team training and communication are often reported to contribute to near-misses/maternal deaths. In Table 3, we provide a summary of the most commonly reported contributing factors, categorized per quality-of-care mechanism, according to the framework provided by Tello et al. [11]. The following mechanisms are described: patient-related factors, clinical practice, emergency medicine, management, workforce, pharmaceuticals, medical products, health facilities, and information systems. The percentage indicates the relative number of the studied cases in which the contributing factor played a part. For example, in the study of Aikpitanyi, delay in commencing treatment played a part in 27.8% of all cases analyzed.

Table 3.

Summary of contributing factors to adverse events or medical (near)misses and maternal deaths. This table describes, per quality-of-care mechanism, the contributing factors described per study. Percentages reflect the relative number of cases (from this study) in which this factor contributed to an adverse event.

| Quality of Care Mechanism | Study | Results | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Iwuh [22] | Patient education (lack of information) | 6.25 |

| Clinical practice | Aikpitanyi [14] | Delay in commencing treatment | 27.8 |

| Benimana [15] | Diagnostic delays | 41.3 | |

| Therapeutic delays | 5.8 | ||

| Florea [18] | Protocol | 5.9 | |

| Nursing resources | 0.2 | ||

| Physician resources | 1.7 | ||

| Other personnel | 0.7 | ||

| Equipment/resources | 6.9 | ||

| Records/results | 14.5 | ||

| Staff communication | 10.0 | ||

| Patient/family communication | 1.6 | ||

| Delay | 1.0 | ||

| Haddad [20] | Lack of trained staff | 5.1 | |

| Difficulty in monitoring | 8.1 | ||

| Delay in diagnosis | 5.6 | ||

| Delay in starting treatment | 6.5 | ||

| Delay in referral/transfer of the case | 5.2 | ||

| Improper management of the case | 21.8 | ||

| Iwuh [22] | Not managed at the level of care that was needed | 20.5 | |

| Clinical assessment (diagnosis), Problem recognition | 4.5 | ||

| Delay in referring | 0.9 | ||

| Managed at inappropriate level | 0.9 | ||

| Monitoring problems | 13.4 | ||

| Johansen [24] | Failure in surveillance | 36 | |

| Failure in diagnostics | 17 | ||

| Failure in operative delivery | 8 | ||

| Failure in resuscitation | 2 | ||

| Sayinzoga [35] | Lack of skilled staff | ||

| Insufficient diagnostic means | |||

| Inadequate monitoring of labour (use of partograph) | |||

| Delay in recognising the complication or administering the correct treatment | |||

| Insufficient follow-up in post-operative or postpartum period | |||

| No respect for asepsis | |||

| Not following protocol | |||

| Inadequate resuscitation | |||

| Insufficient follow-up of anaesthesia induction | |||

| Insufficient pre-operative preparation | |||

| Poor quality of antenatal care visit | |||

| Sorensen [36] | Training of staff insufficient | ||

| Habte [19] | Poor birth preparedness and poor complication readiness | 85.2 | |

| Johansen [25] | Delay in decision to operate | 8 | |

| Delay in decision to delivery time | 20 | ||

| Failure monitoring/Misinterpretation CTG | 13 | ||

| Medication error | 56.2 | ||

| Nasorro [32] | Delay in managing uterine atony | 17 | |

| Carvalho [16] | Inadequate prenatal care: improper conduct with patient | 5 neonatal near-miss/1 death | |

| Huner [21] | Peripartum therapeutic delay | 44.32 | |

| Diagnostic error | 36.36 | ||

| Inadequate birth position | 34.09 | ||

| Medication error | 2.27 | ||

| Zewde [38] | Insuffiency of medical staff | ||

| Delay in making diagnosis | |||

| Poor communication during referral | |||

| Emergency medicine | Aikpitanyi [14] | Delay in deciding to refer patients | 5.6 |

| Haddad [20] | Difficulty in communication between hospital and regulatory centre | 18.8 | |

| Delay in referral/transfer | 5.2 | ||

| Mahmood [29] | Failure in delay and emergency response | 42.9 | |

| Delay in procedures | 28.6 | ||

| Lack of policy, protocol and guidelines. | 46.4 | ||

| Delay in emergency response | 33.3 | ||

| Lacking knowledge and skills | 60 | ||

| Failure to follow best practice | 70 | ||

| Lack of recognition of seriousness. | 50 | ||

| Sayinzoga [35] | delay of the ambulance to reach the health centre | ||

| Nasorro [32] | Inadequate preparation in complete readiness | 17 | |

| Management | Aikpitanyi [14] | Lack of skilled manpower | 11.1 |

| Mahmood [29] | Inadequate access to senior clinical staff | 39.3 | |

| Failure to seek supervision or help | 43.3 | ||

| Sayinzoga [35] | Delay in referring the patient at high level | ||

| Sorensen [36] | Staff not available | ||

| Nasorro [32] | Delated referral from another facility | 26 | |

| Saucedo [34] | Lack of 24/7 on-site presence of obstetrician or anesthesiologist | 5/66 28/81 obstetrician | |

| 13/66 37/81 anesthesiologist | |||

| Zewde [38] | Unavailability of a senior obstetrician | ||

| Inappropriate management | |||

| Multiple referrals between health facilities | |||

| Health workforce | Johansen [24] | Failure in teamwork | 14 |

| Johansen [25] | Failure in cooperation between midwife and physician | 16 | |

| Pharmaceuticals and medical products | Aibar [13] | Peripheral venous catheter | 86.2 |

| Closed bladder catheter | 18.9 | ||

| Aikpitanyi [14] | Non-availability of blood products | 33.3 | |

| Lack of essential emergency drugs | 11.1 | ||

| Benimana [15] | Delayed or lacking supplies (blood and medication) | 5.8 | |

| Haddad [20] | Lack of medication | 1.8 | |

| Absence of blood products | 1.3 | ||

| Johansen [24] | Failure in administration of medication | 11.1 | |

| Sayinzoga [35] | Lack of isogroup blood | ||

| Wasim [37] | Inadequacy in blood arrangement | ||

| Zewde [38] | Lack of supplies and equipment | ||

| Health Facilities | Aikpitanyi [14] | Non-functional ICU | 11.1 |

| Carvalho [16] | Inadequate prenatal care: difficult access due to lack of specialised services | 46.5 | |

| Mulongo [31] | Lack of continuity of care and coordination | ||

| Wasim [37] | Inadequacy in overburdened ICU | ||

| Information Systems | Iwuh [22] | Incomplete registration (lack of information) | 6.3 |

| Johanssen [24] | Failure in documentation | 5 | |

| Huner [21] | Lack of documentation |

Table 4 summarises and categorises the contributing factors according to the level of healthcare in which they occurred, including individual healthcare workers (nurses or doctors), teamwork, or the healthcare system in which the team and the individuals cooperate. Some factors may occur on multiple levels (such as delay). Not all factors described in Table 3, are categorised in Table 4, because of insufficient information in the primary studies to determine the level of healthcare in which these factors occurred (for example, monitoring problems, inadequate preparation and medication errors).

Table 4.

Contributing factors categorised and summarised.

| Protocols | Delay | Equipment and Staff | Communication | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of Adequate Protocol | Not Following Protocol | Delay in Referral/Transfer | Delay in Diagnostics | Delay in Decision-Making/Therapy | Lack of Equipment | Lack of (Well Trained) Staff | Verbal | Medical File | |

| Individual healthcare worker | 5.9% [18] 70% [24] |

0.9% [21] 5.2% [20] 5.6% [14] 26% [32] |

4.5% [22] 13.7% [20] 17% [25] 36.4% [21] 41.3% [15] |

5.8% [15] 6.5% [20] 27.8% [14] 28.6% [20] 33.3% [29] 44.3% [21] 46.0% [24] 48% [25] 61% [32] |

13% [32] 18.2% [21] 56% [25] 60% [29] |

1.6% [18] 6.25% [22] |

5% [24] 6.3% [22] |

||

| Teamwork | 14% [24] 39% [25] 43.3% [29] |

10% [18] | |||||||

| System | 46.4% [29] | 42.9% [29] | 6.9% [18] 55.5% [14] 5.8% [15] 3.1% [20] |

2.6% [18] 5.1% [20] 11.1% [14] 28% [34] 39.3% [29] |

18.8% [20] | 14.5% [18] | |||

4. Discussion

The aim of our review was to identify the direct and indirect causes of medical errors and adverse events in obstetrics and gynecologic practice. Our review included 26 studies from the last 13 years concerning the direct and/or indirect cause(s) of medical errors in obstetrics. The included studies are cross-sectional studies (N = 12), case–control studies (N = 8), and cohorts (N = 6), mainly based on retrospective medical record reviews. Maternal deaths and maternal near-misses were frequently used to select cases for medical record reviews.

The included studies were performed in 18 different countries and under different conditions, including developed and developing countries.

Table 3 summarizes the “quality of care” mechanisms that were frequently found to be a contributing cause to the onset of medical errors and adverse events. All of the risk factors identified in this review imply several categories of direct and indirect factors regarding: (1) delay of care, (2) coordination and management of care and (3) scarcity of supply, personnel, and knowledge. These factors occurred at both the level of individual healthcare workers (such as not following protocol, delay in decision making) and at a system level (no protocol available, lack of staff and equipment).

Although most included studies describe the same types of risk factors for errors and adverse events, it is important to interpret these results with knowledge of the (local) circumstances of the studies, such as socio-economical, geographical, cultural and financial factors.

Studies conducted in developing countries often found a lack of supply, lack of blood products, non-functional IC-units and non-availability of medication as causes for errors and adverse events [14,15,27,28,35,36,37]. Although these factors do not seem to apply to developed countries, recent circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and war in Europe and Asia, have shown the vulnerability of the current health and medical systems. The import of medication and supply from abroad is currently under pressure.

The same applies to the factor a lack of (qualified) personnel, which is mainly described in low-income countries [17,29,31,35]. However, with an imminent shortage of healthcare personnel worldwide, developed countries will be threatened by this factor as well.

Furthermore, studies in both high- and low-income countries found second and third delay to be risk factors for medical errors and adverse events. Second delay is related to reaching an appropriate health facility, and third delay occurs once the patient reaches the health facility and is waiting to see a medical professional. The proportion of cases in which treatment delay had a part ranged from 0.9% [22] to 42.9% [29]. In developing countries, second and third delay occurs due to a lack of supply, ambulances and poor infrastructure [14,15,19,22,27,29,30,32,35]. In developed countries, second and third delay appeared to occur as a result of delayed referral between first-, second- and third-line healthcare systems, for example, in countries where home birth is still common [23,24]. In addition, a lack of teamwork and communication at the moment of referral increases the risk for errors and adverse events [16,18,20], even as a lack of continuity and coordination of antenatal and obstetrical care [31]. Lastly, shortage of information or an incomplete medical file also increases the risk of medical errors and adverse events [18]. This underlies the importance of an integral, cross-institutional medical file, which is currently not available in most developed countries due to privacy laws.

An additional important insight from the verification is that there is a lack of unambiguous terminology and/or definitions in the field of near-misses, complications, (medical) errors or root cause analysis. Table 2 shows that only 17 (of 27) studies provide a definition of these terms. In 9 studies, the definitions refer to criteria from the World Health Organization (WHO). To gain homogeneity, we strongly recommend that future research conform to these definitions using the WHO criteria.

This systematic review has some limitations. Disadvantages of medical record reviews are the risk of selection bias, hindsight bias and the fact that the reliability of the results depends on the quality (completeness/readability) of the included medical files and the experience of the abstractors. It is not clear against which standards/guidelines the files have been tested and whether there are differences in standards between high- and low-income countries.

Furthermore, the described factors remain quite superficial qualifications of context and situations and often did not expose root causes of adverse events and medical errors.

Fur multiple factors, such as delay of care and communication, a retrospective analysis comes with a high risk of hindsight bias and is judged in the eye of the beholder. While it may seem logical in retrospect that a quicker response or referral could have led to better outcomes, it is essential to question whether healthcare workers may have misinterpreted the available knowledge of the patient at the time; therefore, incorrectly referred or treated too late.

In addition, when a medical file is retrospectively judged, certain cause-and-effect relations are supposed and attributed to a healthcare worker, while it might have been the healthcare system that allowed the adverse event to occur. For example, if a patient in labor is referred ‘too late’ to a hospital, this might be due to a personal mistake by the healthcare worker. However, if the healthcare system was set up differently, the chance that this error would occur would be different. For example, in a healthcare system where all deliveries have to take place in hospitals, the chance that this error would have occurred is probably much smaller.

As mentioned in the introduction, quality improvement strategies have been developed on different levels: (1) system-level strategies, (2) institutional/organizational strategies and (3) patient-level strategies [4]. Unfortunately, medical record reviews focus on the health situation of the patient and do not provide any information regarding the local health system and possible factors of influence, such as the circumstances on the work floor at the moment of the incident, for example, workload, supply of material, working atmosphere, current lack of staff, etc. Medical record reviews might be deficient in identifying environmental circumstances that allow errors to occur, possibly leaving large amounts of information underexposed. This information could be obtained by, for example, interviewing staff and direct observations of patient care.

Although the registration of adverse events contributes as a signaling system for quality of care, a more in-depth analysis is essential to take preventive measures on a system or institutional level.

In most developed countries, ‘clinical audits’ are used to describe a process of assessing clinical practice against standards. Interviews of involved healthcare providers and patients are part of this and may improve the knowledge regarding risk factors at a system level. Analytical methods such as the Functional Resonance Analysis Method (FRAM) [40] are developed to provide insight into how healthcare professionals work together under complex circumstances and the ways in which they must adapt to fluctuations. Using a method like FRAM might improve the insight into causes for errors in a broader context, including the reality of the workplace.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review regarding the direct and indirect causes of medical errors in gynaecology and obstetrics has led us to 26 studies performed in 18 countries, mostly based on reported adverse events and medical record reviews. The findings provide insight into general and circumstance-specific, direct or indirect causes for adverse events and errors, such as (1) delay of care, (2) coordination and management of care and (3) scarcity of supply, personnel, and knowledge. With an eye to the future and an imminent shortage of healthcare personnel worldwide, these findings should be taken seriously by healthcare developers and should encourage changes at the system level in order to keep healthcare available, safe and of a high standard for every patient.

In order to make preventive measures to avoid future errors, we would advise further research concerning the onset of medical errors or near-misses in relation to the healthcare system, workplace behaviour and safety/quality of healthcare. Therefore, we should analyse the healthcare system in which frequent errors occur in a broader context, including the reality of the workplace. The analytical method called Functional Resonance Analysis Method (FRAM) is an example of a method that provides insight into how healthcare professionals work together under complex circumstances and the ways in which they must adapt to fluctuations. With this method, important steps, supplies, personal staff and mutual interactions between these actors can be mapped, and preventive measures might be taken to avoid future adverse events and medical errors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare11111636/s1, Table S1. Summary of findings (PDF).

Appendix A

Table A1.

The specific search terms including used filters, and the number of articles found per database).

| Search Database | Search Terms | Filters | Articles (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pubmed | Medical error, medical mistake, adverse event, risk management, health care quality assessment, health care quality, access, and evaluation, gynaecology and/or obstetrics |

|

1598 |

| EMBASE | Medical error, medical mistake, adverse event, complication, risk factor, risk management, incident report, risk report, quality assurance, quality assessment, health care quality assessment, health care quality, access, and evaluation, gynaecology or obstetrics |

|

701 |

| Web of knowledge | Medical error, medical mistake, adverse event, complication, risk factor, risk management, incident report, quality assurance, quality assessment, health care quality assessment |

|

2988 |

| cocchrane library | Medical error, medical mistake, adverse event, risk management, health care quality assessment, health care quality, access and evaluation, gynaecology, obstetrics |

|

1003 |

| Total (before exclusion) | 6290 |

* Inter observer reliability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K. (Désirée Klemann), M.R., H.M., F.v.M. and D.K. (Dorthe Klein), methodology, D.K. (Désirée Klemann), M.R. and D.K. (Dorthe Klein), software, D.K. (Désirée Klemann), M.R. and D.K. (Dorthe Klein), validation, D.K. (Désirée Klemann), M.R. and D.K. (Dorthe Klein); formal analysis, D.K. (Désirée Klemann), M.R. and D.K. (Dorthe Klein), investigation, D.K. (Désirée Klemann), M.R. and D.K. (Dorthe Klein); resources, D.K. (Désirée Klemann), M.R. and D.K. (Dorthe Klein); data curation, D.K. (Désirée Klemann), M.R. and D.K. (Dorthe Klein); writing—original draft preparation, D.K. (Désirée Klemann), M.R. and D.K. (Dorthe Klein); writing—review and editing H.M. and F.v.M.; visualization, D.K. (Désirée Klemann), M.R. and D.K. (Dorthe Klein); supervision, H.M. and F.v.M.; project administration, D.K. (Désirée Klemann); funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Busse R.P.D., Quentin W. Improving Healthcare Quality in Europe: Characteristics, Effectiveness and Implementation of Different Strategies. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graafmans W. EU Actions on Patient Safety and Quality of Healthcare. European Commission, Healthcare Systems Unit; Madrid, Spain: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development & International Bank for Reconstruction and Development . Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative for Universal Health Coverage. World Health Organization, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development & International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; Geneva, Switzerland: 2018. World Health. [Google Scholar]

- 4.OECD . Caring for Quality in Health: Lessons Learnt from 15 Reviews of Health Care Quality. OECD Publishing; Paris, France: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walshe K. Adverse events in health care: Issues in measurement. Health Care Qual. 2000;9:47–52. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin-Delgado J., Martínez-García A., Aranaz J.M., Valencia-Martín J.L., Mira J.J. How Much of Root Cause Analysis Translates into Improved Patient Safety: A Systematic Review. Med. Princ. Pract. 2020;29:524–531. doi: 10.1159/000508677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson R.M., Runciman W.B., Gibberd R.W., Harrison B.T., Newby L., Hamilton J.D., BS F.R.M.W.M., Fanzca W.B.R., Rn R.B.T.H., Llb M.L.N., et al. The Quality in Australian Health Care Study. Med. J. Aust. 1995;163:458–471. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb124691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leape L.L., Brennan T.A., Laird N., Lawthers A.G., Localio A.R., Barnes B.A., Hebert L., Newhouse J.P., Weiler P.C., Hiatt H. The Nature of Adverse Events in Hospitalized Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;324:377–384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J., Liu P., Gong X., Liang F. Relating Medical Errors to Medical Specialties: A Mixed Analysis Based on Litigation Documents and Qualitative Data. Risk Manag. Health Policy. 2020;13:335–345. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S246452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J.M., Akl E.A., Brennan S.E., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tello J.E., Barbazza E., Waddell K. Review of 128 quality of care mechanisms: A framework and mapping for health system stewards. Health Policy. 2019;124:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worster A., Bledsoe R.D., Cleve P., Fernandes C.M., Upadhye S., Eva K. Reassessing the Methods of Medical Record Review Studies in Emergency Medicine Research. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2005;45:448–451. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aibar L., Rabanaque M.J., Aibar C., Aranaz J.M., Mozas J. Patient safety and adverse events related with obstetric care. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014;291:825–830. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3474-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aikpitanyi J., Ohenhen V., Ugbodaga P., Ojemhen B., Omo-Omorodion B.I., Ntoimo L.F., Imongan W., Balogun J., Okonofua F.E. Maternal death review and surveillance: The case of Central Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0226075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benimana C., Small M., Rulisa S. Preventability of maternal near miss and mortality in Rwanda: A case series from the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali (CHUK) PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0195711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carvalho O.M.C., Junior A.B.V., Augusto M.C.C., Leite J.M., Nobre R.A., Bessa O.A.A.C., De Castro E.C.M., Lopes F.N.B., Carvalho F.H.C. Delays in obstetric care increase the risk of neonatal near-miss morbidity events and death: A case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:437. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03128-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.David E., Machungo F., Zanconato G., Cavaliere E., Fiosse S., Sululu C., Chiluvane B., Bergström S. Maternal near miss and maternal deaths in Mozambique: A cross-sectional, region-wide study of 635 consecutive cases assisted in health facilities of Maputo province. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:401. doi: 10.1186/s12884-014-0401-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Florea A., Caughey S.S., Westland J., Berckmans M., Kennelly C., Beach C., Dyer A., Forster A.J., Oppenheimer L.W. The Ottawa Hospital Quality Incident Notification System for Capturing Adverse Events in Obstetrics. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2010;32:657–662. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34569-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habte A., Wondimu M. Determinants of maternal near miss among women admitted to maternity wards of tertiary hospitals in Southern Ethiopia, 2020: A hospital-based case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0251826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haddad S.M., Cecatti J.G., Souza J.P., Sousa M.H., Parpinelli M.A., Costa M.L., Pacagnella R.C., Brum I.R., Filho O.B.M., Feitosa F.E., et al. Applying the Maternal Near Miss Approach for the Evaluation of Quality of Obstetric Care: A Worked Example from a Multicenter Surveillance Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2014;2014:989815. doi: 10.1155/2014/989815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hüner B., Derksen C., Schmiedhofer M., Lippke S., Janni W., Scholz C. Preventable Adverse Events in Obstetrics—Systemic Assessment of Their Incidence and Linked Risk Factors. Healthcare. 2022;10:97. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10010097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwuh I.A., Fawcus S., Schoeman L. Maternal near-miss audit in the Metro West maternity service, Cape Town, South Africa: A retrospective observational study. S. Afr. Med. J. 2018;108:171–175. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i3.12876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen K.R., Hvidman L., Kierkegaard O., Gliese H., Manser T., Uldbjerg N., Brogaard L. Noise as a risk factor in the delivery room: A clinical study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0221860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johansen L.T., Braut G.S., Andresen J.F., Øian P. An evaluation by the Norwegian Health Care Supervision Authorities of events involving death or injuries in maternity care. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2018;97:1206–1211. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johansen L.T., Braut G.S., Acharya G., Andresen J.F., Øian P. How common is substandard obstetric care in adverse events of birth asphyxia, shoulder dystocia and postpartum hemorrhage? Findings from an external inspection of Norwegian maternity units. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020;100:139–146. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalisa R., Rulisa S., Akker T.V.D., Van Roosmalen J. Maternal Near Miss and quality of care in a rural Rwandan hospital. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:324. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1119-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasahun A.W., Wako W.G. Predictors of maternal near miss among women admitted in Gurage zone hospitals, South Ethiopia, 2017: A case control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:260. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1903-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulkarni R., Chauhan S., Daver R., Nandanwar Y., Patil A., Bhosale A. Prospective observational study of near-miss obstetric events at two tertiary hospitals in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016;132:170–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahmood M.A., Mufidah I., Scroggs S., Siddiqui A.R., Raheel H., Wibdarminto K., Dirgantoro B., Vercruyssen J., Wahabi H.A. Root-Cause Analysis of Persistently High Maternal Mortality in a Rural District of Indonesia: Role of Clinical Care Quality and Health Services Organizational Factors. BioMed. Res. Int. 2018;2018:3673265. doi: 10.1155/2018/3673265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mawarti Y., Utarini A., Hakimi M. Maternal care quality in near miss and maternal mortality in an academic public tertiary hospital in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:149. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1326-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulongo S.M., Kaura D., Mash B. Self-reported continuity and coordination of antenatal care and its association with obstetric near miss in Uasin Gishu county, Kenya. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2023;15:8. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v15i1.3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nassoro M.M., Chiwanga E., Lilungulu A., Bintabara D. Maternal Deaths due to Obstetric Haemorrhage in Dodoma Regional Referral Hospital, Tanzania. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2020;2020:8854498. doi: 10.1155/2020/8854498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neogi S.B., Sharma J., Negandhi P., Chauhan M., Reddy S., Sethy G. Risk factors for stillbirths: How much can a responsive health system prevent? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:33. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1660-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saucedo M., Bouvier-Colle M., Blondel B., Bonnet M., Deneux-Tharaux C. Delivery Hospital Characteristics and Postpartum Maternal Mortality: A National Case-Control Study in France. Obstet. Anesth. Dig. 2020;40:54. doi: 10.1097/01.aoa.0000661292.57610.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sayinzoga F., Bijlmakers L., van Dillen J., Mivumbi V., Ngabo F., van der Velden K. Maternal death audit in Rwanda 2009–2013: A nationwide facility-based retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009734. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorensen B.L., Elsass P., Nielsen B.B., Massawe S., Nyakina J., Rasch V. Substandard emergency obstetric care—A confidential enquiry into maternal deaths at a regional hospital in Tanzania. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2010;15:894–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasim T., Raana G., Wasim M., Mushtaq J., Amin Z., Asghar S. Maternal near-miss, mortality and their correlates at a tertiary care hospital. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2021;71:1843–1848. doi: 10.47391/JPMA.05-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zewde H.K. Quality and timeliness of emergency obstetric care and its association with maternal outcome in Keren Hospital, Eritrea. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:14614. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-18685-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pattinson R., Say L., Souza J.P., Broek N.v.D., Rooney C. WHO maternal death and near-miss classifications. Bull. World Health Organ. 2009;87:734. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.071001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hollnagel E. FRAM: The Functional Resonance Analysis Method. Modelling Complex Socio-Technical Systems. 1st ed. CRC Press; London, UK: 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.