Abstract

Evidence regarding the adverse burden of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) in hospitalized neonates in resource-constrained settings is sparse. We attempted to determine the prevalence of SNJ, described using clinical outcome markers, in all World Health Organization (WHO) regions in the world. Data were sourced from Ovid Medline, Ovid Embase, Cochrane Library, African Journals Online, and Global Index Medicus. Hospital-based studies, including the total number of neonatal admissions with at least one clinical outcome marker of SNJ, defined as acute bilirubin encephalopathy (ABE), exchange blood transfusions (EBT), jaundice-related death, or abnormal brainstem audio-evoked response (aBAER), were independently reviewed for inclusion in this meta-analysis. Of 84 articles, 64 (76.19%) were from low- and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs), and 14.26% of the represented neonates with jaundice in these studies had SNJ. The prevelance of SNJ among all admitted neonates varied across WHO regions, ranging from 0.73 to 3.34%. Among all neonatal admissions, SNJ clinical outcome markers for EBT ranged from 0.74 to 3.81%, with the highest percentage observed in the African and South-East Asian regions; ABE ranged from 0.16 to 2.75%, with the highest percentages observed in the African and Eastern Mediterranean regions; and jaundice-related deaths ranged from 0 to 1.49%, with the highest percentage observed in the African and Eastern Mediterranean regions. Among the cohort of neonates with jaundice, the prevalence of SNJ ranged from 8.31 to 31.49%, with the highest percentage observed in the African region; EBT ranged from 9.76 to 28.97%, with the highest percentages reported for the African region; ABE was highest in the Eastern Mediterranean (22.73%) and African regions (14.51%). Jaundice-related deaths were 13.02%, 7.52%, 2.01% and 0.07%, respectively, in the Eastern Mediterranean, African, South-East Asian and European regions, with none reported in the Americas. aBAER numbers were too small, and the Western Pacific region was represented by only one study, limiting the ability to make regional comparisons. The global burden of SNJ in hospitalized neonates remains high, causing substantial, preventable morbidity and mortality especially in LMICs.

Keywords: neonatal, jaundice, hyperbilirubinemia, global prevalence

1. Introduction

Severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) in a neonate may manifest as acute bilirubin encephalopathy (ABE) [1] with a range of symptoms including difficulty feeding, tone abnormalities, abnormal cry and the kernicteric facies [2] scored using the bilirubin-induced neurological dysfunction (BIND) score or modified BIND [3,4]. Persistent abnormalities which are now known as the Kernicterus Spectrum Disorder (KSD) [1], occur in 70% of survivors beyond the neonatal period including choreo-athetoid cerebral palsy, deafness, speech and language processing disorders, enamel dysplasia, and learning difficulties [5,6,7].

The Global Burden of Disease study ranks SNJ among the top 5–10 causes of neonatal deaths in countries with the highest number of neonatal deaths [8]. Previous attempts at providing global and regional estimates of SNJ burden have been challenged by limited data. Bhutani et al. estimated 481,000 global cases of SNJ among term/near-term neonates with 114,000 deaths and 75,000 of survivors developing kernicterus [9]. These figures derived using mathematical models with limited data have limitations inherent in such estimates. A previous population-based systematic review and meta-analysis including some authors in our current team (TS, DA, BL) reported a pooled incidence of SNJ at 244 per 100,000 live births [10]. A major drawback of this review was the disproportionate representation of high-income countries with lesser burden of disease. Several studies have suggested that the African and Asian regions have the highest burden of disease [9,10,11]. Factors responsible for these regional burdens include the high prevalence of glucose-6-phosphate deficiency (G6PD) deficiency, late presentation due to the high incidence of out-of-hospital births, inability of caregivers to promptly identify jaundice, caregivers’ decision to seek alternative treatments; lack of or ineffective phototherapy and unavailable or unreliable access to bilirubin estimations [11]. Unfortunately, most data on SNJ in low-resource countries is hospital-based without true population-based data making the actual burden of SNJ unknown. However, this review of hospital-based data covers a wider representation of literature from diverse countries to ascertain, though still imperfect, the burden in low and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs). Our intent is to be the first comprehensive, current systematic review and meta-analysis that provides rigorous, worldwide appraisal of SNJ for all neonatal hospital admissions which included adverse clinical outcomes seen in SNJ, to compare regional geographic differences, and to provide representation from low/lower-resource areas. These data are critical not only to meet the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) but also to assist in identifying region-specific strategies to decrease disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) from KSD morbidities [12].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Criteria for Article Inclusion

We included hospital-based studies that had neonatal hospital admissions for any cause and provided information about at least one clinical marker of SNJ, including number of exchange blood transfusions (EBTs); ABE; abnormal brainstem audio-evoked response (aBAER); or jaundice-related death. No patients or members of the public were involved in any way, and data were from published sources; therefore, investigational review board or ethics committee approval was not needed.

2.2. Criteria for Article Exclusion

Articles were excluded if (1) the entire data collection period was prior to 1997 or later than 2020, (2) sample size was <10, (3) period of data collection was not defined, (4) jaundice was conjugated, from metabolic or neonatal liver disease, (5) EBT was done for conditions unrelated to SNJ, (6) non-English, (7) non-neonatal, (8) publication type was a review article, questionnaire or survey or study design was case-control or experimental study on a subset of neonates with jaundice, and (9) missing critical data (total number of neonatal admissions). In the case of missing data, we (FA, TS) contacted the authors for further information and excluded the article if the requested information was not supplied. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was excluded due to no returned results.

2.3. Outcome Definition

Our primary outcome was the prevalence of SNJ in hospitalized neonates (both inborn and outborn) clinically defined as having at least one clinical indicator of SNJ noted above. We also looked at the prevalence of SNJ in hospitalized jaundiced neonates again using clinical markers noted above. LMIC status was defined using the 2020 World Bank Criteria [13].

2.4. Search Criteria

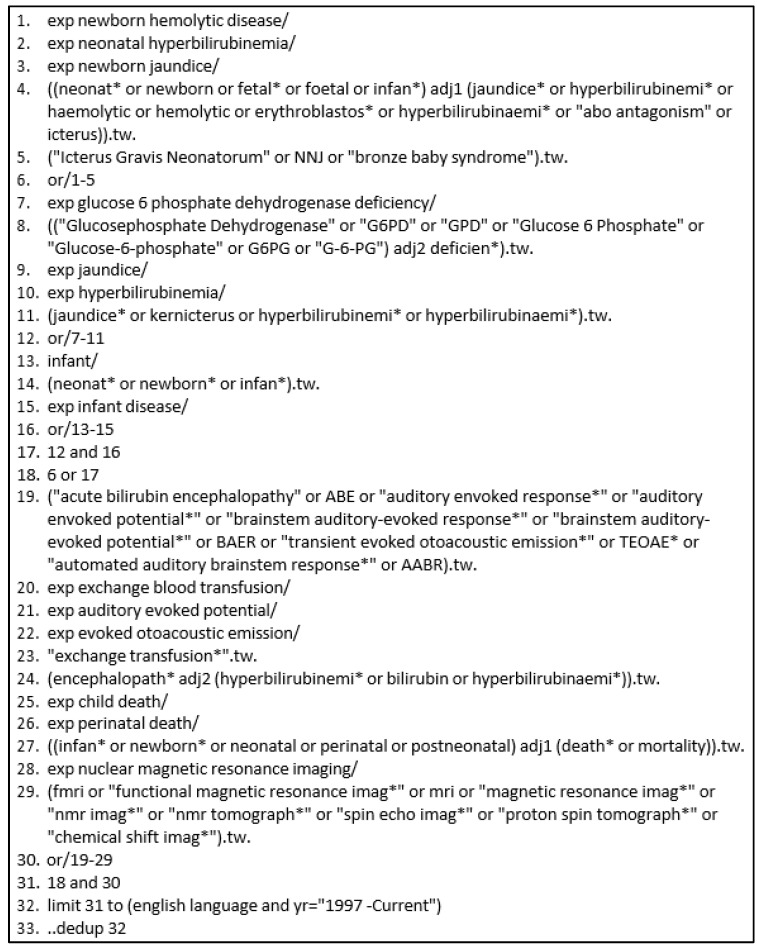

We conducted a comprehensive search including both natural language and controlled vocabulary terms to reflect concepts of a neonatal population and jaundice, including both serum bilirubin and clinical indicators. The search was conducted across five databases: Ovid Medline, Ovid Embase, Cochrane Library via Wiley, African Journals Online, and Global Index Medicus (Figure 1). This search strategy was translated across the different databases to ensure appropriate use of the available controlled vocabulary and unique search functionality. The search was conducted in June 2018 and updated in September 2020. The protocol was registered in Prospero (CRD42018100214). A PRISMA checklist was completed (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Search Protocol: Embase Classic + Embase via Ovid. * is a truncation symbol.

2.5. Data Extraction

Articles were screened using the Rayyan software for systematic reviews [14]. One author (CB) conducted the literature search and uploaded all eligible abstracts onto the software. Three groups of reviewers comprising of two authors per group [group A (UD and TO), group B (FU and LH) and group C (KS and FA)] were involved in the literature review.

During screening, each group member independently assessed the allocated articles’ titles and abstracts for eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved via group dialog and, when necessary, a third author (TS) acted as an arbitrator. This was followed by full-text screening with reasons for exclusion recorded (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the outcome of database searches and the process of selection of included studies.

Data extraction forms were developed, piloted, and refined. Data were extracted using Qualtrics®, including citation information, country and World Health Organization (WHO) region, study duration, total number of neonatal admissions and neonatal jaundice (NNJ) admissions, gestational age (all, only term, only near-term, term and near-term combined, only preterm or unspecified), how jaundice was determined (clinical definition or using bilirubin assay), markers of SNJ: number of EBTs, aBAER, and reported jaundice-related deaths. Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was used to collect data for analysis. Table 1 shows the profile of articles selected for the meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in Meta-analysis [6,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97].

| WHO Region | Country | Admission | NNJ | Gestation | EBT | aBAER | ABE | Deaths | SNJ | Risk of Bias | Ref # | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abolghasemi H et al., 2004 | Eastern Med | Iran ** | 2000 | 283 | All | 18 | 18 | 7 | [15] | |||

| Adebami OJ et al., 2010 | African | Nigeria ** | 605 | 89 | All | 6 | 6 | 5 | [16] | |||

| Adebami OJ et al., 2011 | African | Nigeria ** | 882 | All | 24 | 28 | 9 | 28 | 6 | [17] | ||

| Adhikari S et al., 2017 | SE Asian | Nepal ** | 1708 | 662 | All | 28 | 28 | 5 | [18] | |||

| Ahmed et al., 2005 | SE Asian | India ** | 1275 | 305 | All | 198 | 198 | 7 | [19] | |||

| Akintan PE et al., 2019 | African | Nigeria ** | 534 | 158 | Only term | 11 | 11 | 5 | [20] | |||

| Arain Y et al., 2020 | Americas | USA ++ | 509 | Preterms only | 1 | 1 | 6 | [21] | ||||

| Arnolda G et al., 2015 | SE Asian | Myanmar ** | 2780 | 989 | All | 118 | 118 | 8 | [22] | |||

| Atay E et al., 2005 | European | Turkey + | 2681 | 624 | Term | 98 | 6 | 98 | 5 | [23] | ||

| Audu LI et al., 2016 | African | Nigeria ** | 558 | 123 | Term-near term | 50 | 32 | 16 | 50 | 7 | [24] | |

| Bakhru V DR et al., 2018 | SE Asian | India ** | 1210 | 121 | Term and near-term | 2 | 2 | 7 | [25] | |||

| Bhat P et al., 2016 | SE Asian | India ** | 6000 | 406 | Term-near term | 35 | 35 | 7 | [26] | |||

| Bhutani V et al., 2016 | Americas | USA ++ | 2944 | 677 | Term-near term | 89 | 89 | 7 | [27] | |||

| Bokade C et al., 2018 | SE Asian | India ** | 1038 | 101 | All | 5 | 5 | 5 | [28] | |||

| Bozkurt O et al., 2020 | European | Turkey + | 3200 | 115 | Term and near-term | 67 | 45 | 67 | 7 | [29] | ||

| Bulbul A et al., 2011 | European | Turkey + | 6192 | 782 | Term-near term | 116 | 6 | 1 | 116 | 7 | [30] | |

| Celik HT et al., 2013 | European | Turkey + | 14,947 | 4906 | All | 167 | 3 | 167 | 8 | [31] | ||

| Chhapola V et al., 2018 | SE Asian | India ** | 39,217 | Not specified | 1575 | 1575 | 4 | [32] | ||||

| Colak R CS et al., 2020 | European | Turkey + | 3370 | 338 | Not specified | 4 | 1 | 2 | 12 | 4 | 6 | [33] |

| de Ccarvalho et al., 2011 | Americas | Brazil + | 4002 | 116 | Term-near term | 3 | 116 | 8 | [34] | |||

| Eke CV et al., 2013 | African | Nigeria ** | 2756 | All | 41 | 41 | 7 | [35] | ||||

| El-Honni MS et al., 2013 | Eastern Med | Libya + | 1585 | 400 | Term | 70 | 41 | 2 | 70 | 6 | [36] | |

| Emokpae AA et al., 2016 | African | Nigeria ** | 5229 | 1118 | All | 352 | 190 | 61 | 352 | 8 | [37] | |

| Eneh AU et al., 2008 | African | Nigeria ** | 206 | 44 | All | 36 | 6 | 2 | 36 | 8 | [38] | |

| Erdeve O et al., 2018 | European | Turkey + | 34,670 | 5620 | Term and near-term | 132 | 13 | 11 | 2 | 132 | 7 | [39] |

| Eshete A et al., 2020 | African | Ethiopia * | 913 | 52 | All | 7 | 7 | 5 | [40] | |||

| Eze P et al., 2020 | Eastern Med | Yemen * | 976 | 183 | All | 5 | 5 | 5 | [41] | |||

| Ezeaka C et al., 2004 | African | Nigeria ** | 487 | 141 | All | 24 | 24 | 7 | [42] | |||

| Ezeaka C et al., 2005 | African | Nigeria ** | 535 | 104 | Preterms only | 11 | 11 | 5 | [43] | |||

| Fahmy N et al., 2017 | Eastern Med | Egypt ** | 1725 | 647 | All | 19 | 19 | 6 | [44] | |||

| Fein EH et al., 2019 | Americas | USA ++ | 1,939,745 | 94,626 | Only term | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 | [45] | ||

| Fajolu IB et al., 2011 | African | Nigeria ** | 1297 | All | 52 | 52 | 4 | [46] | ||||

| Farouk Z et al., 2017 | African | Nigeria ** | 386 | 100 | All | 26 | 27 | 11 | 27 | 8 | [47] | |

| Farouk Z et al., 2018 | African | Nigeria ** | 2813 | 551 | All | 104 | 33 | 104 | 8 | [48] | ||

| Hadgu FB et al., 2020 | African | Ethiopia * | 1785 | 247 | All | 21 | 21 | 5 | [49] | |||

| Hakan N et al. et al., 2015 | European | Turkey + | 7450 | 1862 | All | 306 | 17 | 3 | 306 | 7 | [50] | |

| Hameed NN et al., 2014 | Eastern Med | Iraq + | 5034 | 162 | Term-near term | 53 | 99 | 19 | 53 | 7 | [51] | |

| Hanson C et al., 2019 | SE Asian | India ** | 6820 | 1513 | All | 14 | 14 | 5 | [52] | |||

| Haroon A et al., 2014 | Eastern Med | Pakistan ** | 326 | 124 | Preterms only | 6 | 6 | 7 | [53] | |||

| Helal NF et al., 2019 | Eastern Med | Egypt ** | 972 | 674 | Term and near-term | 81 | 8 | 81 | 7 | [54] | ||

| Ibekwe RC et al., 2012 | African | Nigeria ** | 1374 | 237 | All | 40 | 7 | 40 | 8 | [55] | ||

| Iqbal BJ et al., 2016 | Eastern Med | Pakistan ** | 1323 | 377 | All | 15 | 15 | 5 | [56] | |||

| Isa HM et al., 2017 | Eastern Med | Bahrain ++ | 2940 | 1129 | All | 49 | 11 | 49 | 5 | [57] | ||

| Israel-Aina et al., 2012 | African | Nigeria ** | 1784 | 472 | All | 166 | 60 | 166 | 7 | [58] | ||

| Jajoo M et al., 2019 | SE Asian | India ** | 1675 | All | 136 | 39 | 136 | 6 | [59] | |||

| Kilicdag et al., 2014 | European | Turkey + | 5300 | 529 | Term-near term | 33 | 3 | 33 | 6 | [60] | ||

| Kumar MN et al., 2012 | SE Asian | India ** | 236 | 48 | all | 1 | 1 | 5 | [61] | |||

| Malla T et al., 2015 | SE Asian | Nepal ** | 1114 | 481 | All | 29 | 29 | 8 | [62] | |||

| Malik FR et al., 2016 | Eastern Med | Pakistan ** | 4497 | All | 62 | 62 | 4 | [63] | ||||

| Mirajkar S et al., 2016 | SE Asian | India ** | 2704 | 575 | Term | 8 | 8 | 6 | [64] | |||

| Mmbaga BT et al., 2012 | African | Tanzania ** | 5033 | 174 | All | 5 | 5 | 5 | [65] | |||

| Nyangabyaki-Twesigye C et al., 2020 | African | Uganda * | 4840 | 242 | All | 17 | 7 | 7 | 8 | [66] | ||

| Ochigbo SO et al., 2016 | African | Nigeria ** | 2820 | 553 | All | 17 | 21 | 8 | 17 | 8 | [67] | |

| Ogunfowora O.B et al., 2019 | African | Nigeria ** | 2232 | 645 | All | 4 | 40 | 40 | 7 | [68] | ||

| Ogunlesi TA et al., 2007 | African | Nigeria ** | 4198 | 722 | All | 87 | 115 | 42 | 115 | 7 | [69] | |

| Ogunlesi TA et al., 2011 | African | Nigeria ** | 990 | 152 | Term | 75 | 75 | 6 | [70] | |||

| Ogunlesi, TA et al., 2019 | African | Nigeria ** | 519 | All | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | [71] | |||

| Ojukwu JU et al., 2004 | African | Nigeria ** | 536 | 61 | All | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | [72] | ||

| Okagua J et al., 2017 | African | Nigeria ** | 622 | 92 | All | 28 | 28 | 5 | [73] | |||

| Okechukwu AA et al., 2009 | African | Nigeria ** | 654 | 58 | All | 20 | 11 | 20 | 5 | [74] | ||

| Onyearugha CN et al., 2014 | African | Nigeria ** | 1196 | 172 | All | 48 | 5 | 2 | 48 | 8 | [75] | |

| Osaghae DO et al., 2013 | African | Nigeria ** | 641 | 105 | All | 3 | 3 | 5 | [76] | |||

| Pius S et al., 2017 | African | Nigeria ** | 639 | 64 | All | 30 | 3 | 5 | 30 | 7 | [77] | |

| Poudel P et al., 2009 | SE Asian | Nepal ** | 140 | 103 | Preterm only | 29 | 0 | 29 | 3 | [78] | ||

| Rasul CH et al., 2010 | SE Asian | Bangladesh ** | 1981 | 426 | All | 22 | 9 | 12 | 22 | 8 | [79] | |

| Rijal P et al., 2011 | SE Asian | Nepal ** | 820 | 86 | All | 4 | 4 | 7 | [80] | |||

| Salih SA et al., 2013 | Eastern Med | Sudan * | 100 | 46 | Preterm only | 6 | 6 | 5 | [81] | |||

| Salas AA et al., 2008 | Americas | Bolivia ** | 1167 | 362 | Term-near term | 78 | 15 | 78 | 6 | [82] | ||

| Simiyu DE et al., 2003 | African | Kenya ** | 308 | 106 | All | 24 | 24 | 5 | [83] | |||

| Simiyu DE et al., 2004 | African | Kenya ** | 533 | 198 | Preterm only | 6 | 121 | 121 | 3 | [84] | ||

| Singh SK et al., 2016 | SE Asian | India ** | 1175 | 167 | All | 38 | 10 | 38 | 8 | [85] | ||

| Singla DA et al., 2017 | SE Asian | India ** | 1970 | 432 | Term-near term | 60 | 10 | 2 | 60 | 7 | [86] | |

| Speleman K et al., 2012 | European | Belgium ++ | 615 | 363 | All | 12 | 12 | 7 | [87] | |||

| Tagare A et al., 2013 | SE Asian | India ** | 1801 | 52 | Preterms only | 7 | 31 | 11 | 6 | [88] | ||

| Taghidiri MM et al., 2008 | Eastern Med | Iran ** | 834 | All | 11 | 11 | 7 | [89] | ||||

| Tette EMA et al., 2020 | African | Ghana ** | 2004 | 155 | All | 12 | 12 | 5 | [90] | |||

| Thangavelu K et al., 2019 | European | Germany ++ | 4512 | 1286 | All | 10 | 12 | 26 | 26 | 8 | [91] | |

| Thielemans L et al., 2018 | SE Asian | Thailand + | 2980 | 1946 | All | 212 | 212 | 8 | [92] | |||

| Turner C et al., 2013 | SE Asian | Thailand + | 952 | 448 | All | 7 | 7 | 5 | [93] | |||

| Udo JJ et al., 2008 | African | Nigeria ** | 794 | 153 | All | 8 | 8 | 5 | [94] | |||

| Ugochukwu EF et al., 2002 | African | Nigeria ** | 133 | Preterm only | 2 | 2 | 3 | [95] | ||||

| Usman F et al., 2019 | African | Nigeria ** | 360 | 66 | Only term | 20 | 16 | 20 | 8 | [6] | ||

| Wouda EMN et al., 2020 | SE Asian | Thailand + | 2980 | 1946 | All | 4 | 35 | 14 | 35 | 8 | [96] | |

| Zhang F et al., 2020 | West Pacific | China + | 26,369 | 673 | Term and near-term | 195 | 73 | 195 | 6 | [97] |

* low income country; ** lower middle income country; + upper middle income country; ++ high income country. WHO: World Health Organization; NNJ: neonatal jaundice; EBT: exchange blood transfusion; abnormal Brainstem Auditory Evoked Response: aBAER; acute bilirubin encephalopathy: ABE: severe neonatal jaundice: SNJ: Reference number: Ref #: Eastern Mediterranean: Eastern Med; South-East Asian: SE Asian.

2.6. Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment

Each article was scored based on five parameters that were modified from those used in a prior population-based study also using clinical parameters to assess the burden of disease from SNJ [11]. Scoring was in line with recommendations by the modified quality assessment tool for systematic reviews of observational studies (QATSO) scoring system [98]. These included: (1) if the sampling method was representative of the target population i.e., covered the whole nursery population (scored 3), term and near-term only (scored 2), premature or term only (scored 1); (2) the method used to define jaundice, categorized based on bilirubin assay (scored 2), visual clinical assessment (scored 1) or not stated (scored 0); (3) whether the study excluded any of the following conditions: Glucose -6 Phosphate Dehydrogenase deficiency, ABO incompatibility, Rhesus incompatibility or sepsis and was grouped as yes (scored 0) or no (scored 1); (4) if total number of SNJ cases was reported and classed as yes (scored 1) or no (scored 0); and (5) whether clinically significant jaundice was clearly defined in the Methods section (including use of AAP/NICE guidelines) and classified as yes (scored 1) or no (scored 0). Each study’s quality was judged based on aggregate points, with a maximum obtainable score of 10, and classified as “good quality” (7–10 points), “fair quality” (4–6 points) and “poor quality” (0–3 points).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The summary estimate for the meta-analysis was prevalence/proportion, which was transformed using Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation to enable them to correspond to probabilities under the standard normal distribution and enhance significance testing [99]. The double transformations adequately addressed issues of variance instability as well as confidence intervals (CIs) of proportions falling outside the possible range of 0 to 1 for binomial data [100]. Pooled estimates were calculated using DerSimonian and Laird’s random-effects method, weighting individual study estimates using the inverse of the variance of their transformed proportion as study weight, with their 95% CI determined using the Clopper–Pearson exact binomial method [101]. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and I2 with a p-value of <0.10. The I2 quantifies the proportion of the dispersion that is real and not spurious [102]. Possible sources of heterogeneity were also explored via subgroup analysis.

Additionally, mixed-effects meta-regression analysis was used to determine whether study-level covariates, such as publication year, country-level income and methodological domains for assessing study quality, explained some of the observed between-study heterogeneity. A formal test of publication bias was assessed using Begg’s adjusted rank correlation [102] and Egger’ regression asymmetry tests [103], as well as through visual interpretation of funnel plots. Analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

The electronic databases search identified 4436 distinct articles (after removing 1497, duplicates) (Figure 2). An additional 3729 articles were excluded after reviewing titles and abstracts. Seven hundred and six (706) articles were selected for full article review and 700 (99%) were retrieved and reviewed. The remaining six articles were unavailable from any source that we could access. Eighty-four hospital-based studies involving a total of 2,210,043 neonatal admissions and 5986 neonates with at least one marker of SNJ were included in the meta-analysis (Table 1) [6,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97].

Sixty-four (76.19%) of the studies were conducted in LMICs (low (5) and lower-middle (59)), including 43 (51.19%) from the African region and 1 (1.19%) from the Eastern Mediterranean region (Table 1). Fourteen (16.67) were from upper-middle income countries. Six (7.1%) of the articles were from high-income countries. Both preterm and term neonates were included in 54 (64.2%) studies. Half (43/84) of the studies were adjudged to be of high quality (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence (%) of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) among all hospital admissions.

| N | Estimates (95% Confidence Interval) |

p-Value for Heterogeneity |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 84 | 2.55 (1.93–3.27) | - |

| Country Income Level | 0.013 | ||

| High | 6 | 0.81 (0.11–2.09) | |

| Upper-middle | 14 | 1.76 (1.00–2.73) | |

| Lower-middle | 59 | 3.15 (2.25–4.18) | |

| Low | 5 | 1.47 (0.36–3.20) | |

| Gestation | 0.389 | ||

| Preterm | 8 | 6.28 (1.68–13.32) | |

| Term and near term | 14 | 2.22 (1.11–3.71) | |

| Term | 8 | 2.04 (0.49–4.57) | |

| All | 54 | 2.36 (1.71–3.10) | |

| Quality of Study | 0.065 | ||

| High | 43 | 2.83 (2.02–3.78) | |

| Moderate | 34 | 1.73 (1.05–2.57) | |

| Low | 7 | 5.90 (1.44–12.97) |

NNJ was included in the diagnoses for 21.99% (95% CI: 18.42–25.78%) of all neonatal admissions in articles included in our review with a significant difference (p < 0.001) between WHO regions ranging from 30.61% (95% CI 22.19–39.74%) in South-East Asia, 20.39% (95% CI 11.73–30.70%) in Europe, 20.10% (95% CI 16.06–24.47%) in Africa, 16.66% (95% CI 4.90–33.54%) in the Eastern Mediterranean, 13.61% (95% CI 2.83–29.34%) in the Americas to 2.55% (95% CI 2.37–2.75%) in the Western Pacific region represented by only one article (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence (%) of neonatal jaundice (NNJ) among all hospital admissions by World Health Organization (WHO) region.

| WHO Regions a | N | Estimates (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 74 | 21.99 (18.42–25.78) |

| African | 34 | 20.10 (16.06–24.47) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 4 | 16.66 (4.90–33.54) |

| European | 10 | 20.39 (11.73–30.70) |

| Americas | 4 | 13.13 (2.83–29.34) |

| South-East Asian | 21 | 30.61 (22.19–39.74) |

| Western Pacific | 1 | 2.55 (2.37–2.75) |

N: Number of studies; WHO: World Health Organization. a Test for subgroup differences: p-value < 0.0001. References: [6,15,16,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,58,60,61,62,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,90,91,92,93,94,96,97].

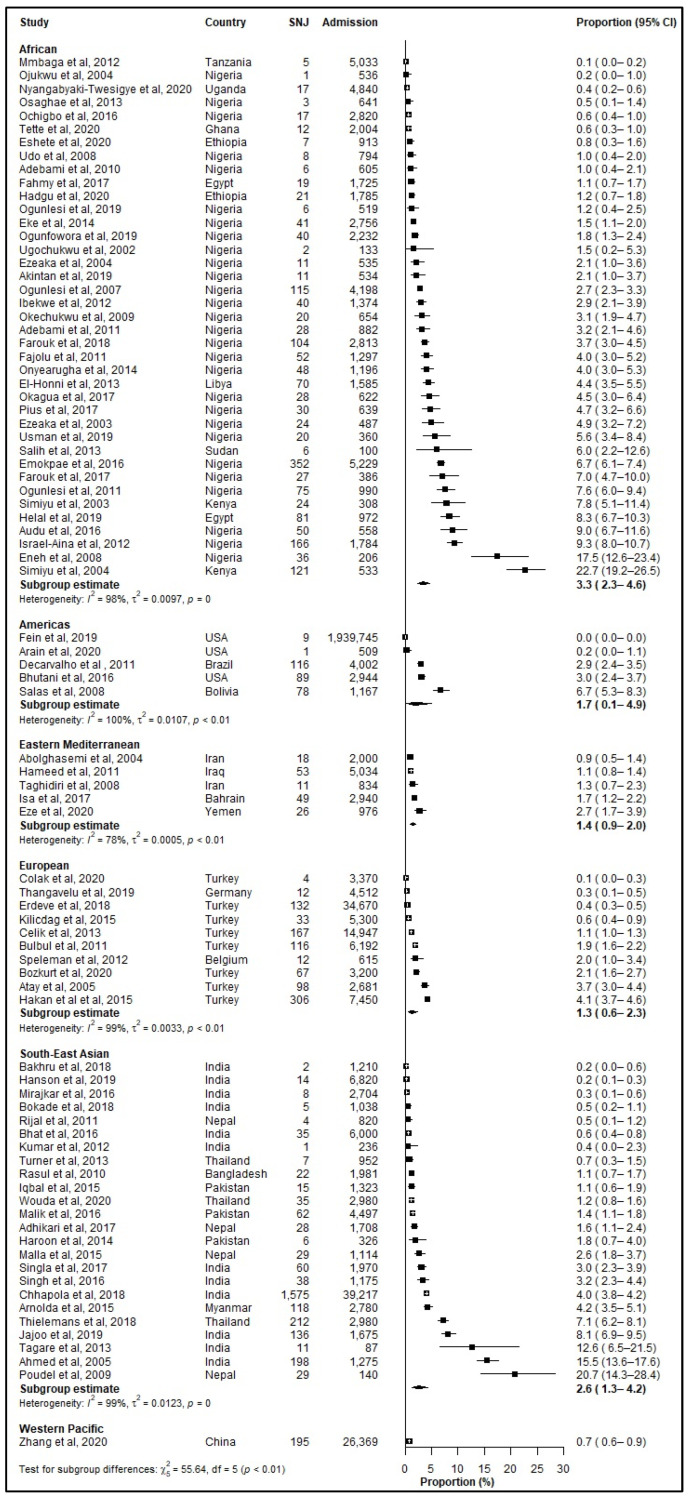

The prevalence of SNJ amongst all neonatal admissions (Figure 3) varied significantly across WHO regions (p < 0.001) with the African region reporting highest prevalence (3.34%, 95% CI: 2.28–4.57%), followed by the South-East Asian region (2.58%, 95% CI: 1.33–4.22) and the Americas (1.73%, 95% CI: 0.14–4.92) [Table 4].

Figure 3.

Prevalence (%) of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) among hospitalized neonates according to World Health Organization (WHO) regions. CI: Confidence interval; SNJ: Severe Neonatal Jaundice; References: [6,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97].

Table 4.

Prevalence (%) of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) and clinical markers among all hospitalized neonates by World Health Organization (WHO) region.

| African | Eastern Mediterranean | European | South-East Asian | Americas | Western Pacific | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Estimates (95% CI) | N | Estimates (95% CI) | N | Estimates (95% CI) | N | Estimates (95% CI) | N | Estimate (95% CI) | N | Estimates (95% CI) | |

| SNJ a | 39 | 3.34 (2.28–4.57) | 5 | 1.42 (0.93–2.02) | 10 | 1.31 (0.61–2.27) | 24 | 2.58 (1.33–4.22) | 5 | 1.73 (0.14–4.92) | 1 | 0.74 (0.64–0.85) |

| EBT b | 16 | 3.81 (2.14–5.92) | 3 | 1.19 (0.80–1.66) | 9 | 1.25 (0.51–2.30) | 17 | 3.50 (1.69–5.90) | 3 | 2.64 (0.17–7.71) | 1 | 0.74 (0.64–0.85) |

| ABE c | 19 | 2.75 (1.75–3.95) | 2 | 1.02 (0.05–3.16) | 8 | 0.16 (0.02–0.40) | 6 | 0.83 (0.36–1.46) | 2 | 0.34 (0.00–2.72) | 1 | 0.28 (0.22–0.34) |

| Jaundice Related Death d | 35 | 1.49 (0.85–2.28) | 2 | 1.24 (0.00–4.48) | 3 | 0.01 (0.00–0.04) | 11 | 0.82 (0.27–1.62) | 1 | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | - | - |

ABE: Acute Bilirubin Encephalopathy; CI: Confidence interval; EBT: Exchange Blood Transfusion; N: Number of studies; SNJ: Severe neonatal jaundice; WHO World Health Organization. a Test for subgroup differences: p-value < 0.001. b Test for subgroup differences: p-value < 0.001. c Test for subgroup differences: p-value < 0.001. d Test for subgroup differences: p-value < 0.001 References: [6,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97].

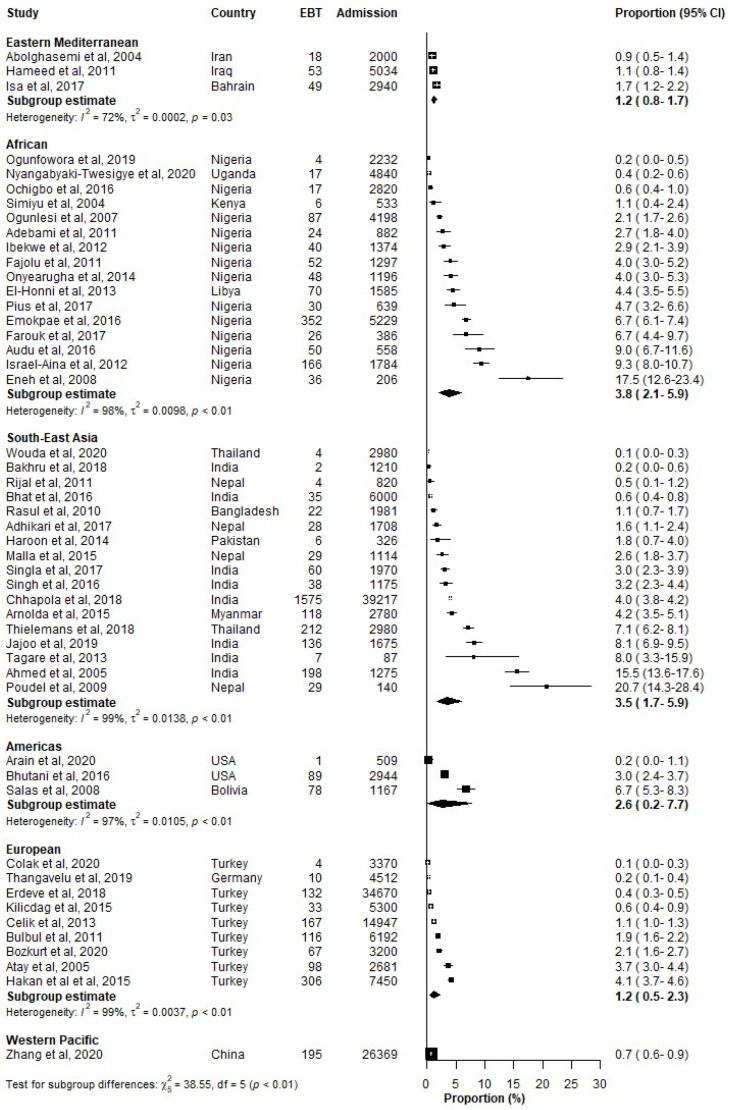

The prevalence of EBT among all neonates was the highest in the African region (3.81%, 95% CI: 2.14–5.92%), followed by the South-East Asian region (3.50%, 95% CI: 1.69–5.90%) (Table 4, Figure 4). Among jaundiced neonates, significant regional differences also existed (p < 0.001), with the African region reporting the highest prevalence of EBT at 21.42% (95% CI: 11.03–34.07) (Table 5).

Figure 4.

Prevalence (%) of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) with exchange transfusions (EBT) among hospitalized neonates according to WHO regions. CI: Confidence interval; EBT: Exchange Blood Transfusion; References: [15,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,36,37,38,39,46,47,49,51,53,55,57,58,59,60,62,66,67,68,69,75,77,78,79,80,82,83,84,85,86,88,91,92,96,97].

Table 5.

Prevalence (%) of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) and clinical markers among hospitalized neonates with jaundice by World Health Organization (WHO) region.

| African | Eastern Mediterranean | European | South-East Asian | Americas | Western Pacific | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Estimates (95% CI) | N | Estimates (95% CI) | N | Estimates (95% CI) | N | Estimates (95% CI) | N | Estimate (95% CI) | N | Estimates (95% CI) | |

| SNJ | 34 | 18.39 (12.87–24.63) | 4 | 12.58 (3.40–26.28) |

10 | 9.02 (2.64–18.62) |

21 | 8.31 (4.20–13.60) | 4 | 31.49 (0.00–89.12) | 1 | 28.97 (25.61–32.46) |

| EBT a | 14 | 21.42 (11.03–34.07) | 3 | 12.13 (1.09–32.11) |

9 | 9.76 (2.57–20.80) |

15 | 10.86 (5.32–18.01) |

2 | 17.03 (9.62–26.02) |

1 | 28.97 (25.61–32.46) |

| ABE b | 17 | 14.51 (9.08–20.90) |

2 | 22.73 (0.00–91.81) |

8 | 2.01 (0.00–8.10) |

5 | 2.07 (0.85–3.74) |

2 | 1.46 (0.00–7.94) |

1 | 10.85 (8.60–13.31) |

| Jaundice Related Death c | 31 | 7.52 (4.95–10.56) |

2 | 13.02 (9.64–16.81) |

3 | 0.07 (0.00–0.20) | 10 | 2.01 (1.06–3.20) |

- | - | - | - |

ABE: Acute Bilirubin Encephalopathy; aBAER: Abnormal Brainstem auditory evoked response; CI: Confidence interval; EBT: Exchange Blood Transfusion; N: Number of studies; SNJ: severe neonatal jaundice; WHO World Health Organization. a Test for subgroup differences: p-value < 0.001. b Test for subgroup differences: p-value < 0.001. c Test for subgroup differences: p-value < 0.001. References: [6,15,16,16,17,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,58,60,61,62,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,90,91,92,93,94,96,97].

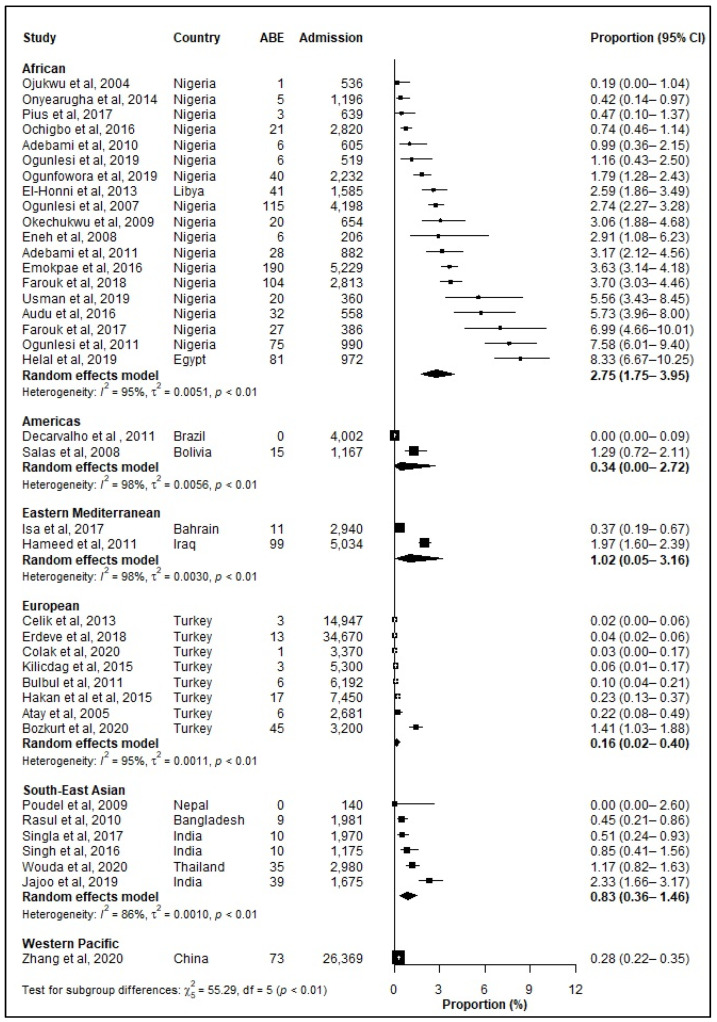

The prevalence of ABE among hospitalized neonates varied by WHO regions with the highest prevalence reported for the African region 2.75% (95% CI: 1.75–3.95%) (Figure 5, Table 4). ABE in jaundiced neonates was highest in the Eastern Mediterranean (22.73%) reporting the highest prevalence of ABE followed by (Table 5).

Figure 5.

Prevalence (%) of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) with acute bilirubin encephalopa-thy/kernicterus (ABE) among hospitalized neonates according to WHO regions. ABE: Acute Bilirubin Encephalopathy; CI: Confidence interval. References: [6,16,17,23,24,30,31,33,36,37,38,39,47,48,50,51,57,60,67,69,70,72,75,77,78,79,82,85,86,87,91].

The highest proportion of jaundice-related deaths among all neonates was 1.49% (95% CI: 0.85–2.28%) in the African region (Table 4). This increased to 7.52% (95% CI: 4.95–10.56%) in neonates with jaundice (Table 5). The Eastern Mediterranean region was next with 1.24% (95% CI: 0.00–4.48%) in all neonates and increased to 13.02% (95% CI: 9.64–16.81%) in neonates with jaundice (Table 4 and Table 5).

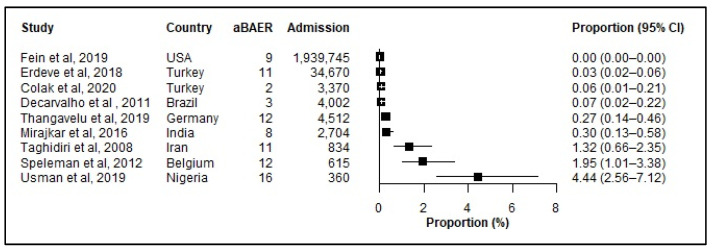

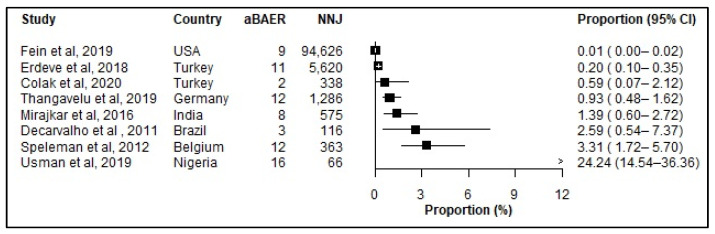

Only nine studies reported aBAERs, making the reported results likely a gross underestimate (Figure 6). For comparison, eight studies reported aBAERS among neonates admitted with jaundice (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Prevalence (%) of abnormal Brainstem Auditory Evoked Response (aBAER) among hospitalized neonates. aBAER: abnormal Brainstem Auditory Evoked Response (aBAER); CI: Confidence interval; References: [6,33,34,39,45,64,87,89,91].

Figure 7.

Prevalence (%) of abnormal Brainstem Auditory Evoked Response (aBAER) among neonates admitted with jaundice. aBAER: abnormal Brainstem Auditory Evoked Response (aBAER); CI: Confidence interval; References: [6,33,34,39,45,64,87,89,91].

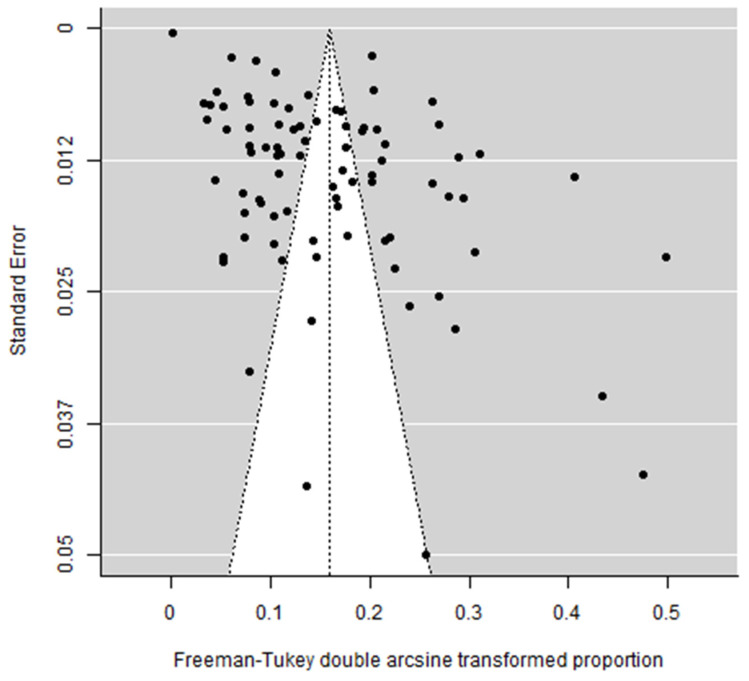

There was evidence of potential publication bias influencing the reporting of prevalence of SNJ. Studies that report a lower proportion of neonates with SNJ were less likely to be published. The funnel plot appeared largely asymmetrical (Figure 8) with empirical evidence supporting this observation (Begg test p < 0.001, Egger’s bias = 13.0, p < 0.001).

Figure 8.

Funnel plot of studies included in the meta-analysis. The unshaded triangle represents the region within which 95% of studies would be expected to lie to lie if the studies are all estimating the same underlying effect. References: [6,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97].

Of the six methodological domains included (5 domains used for assessing study quality and type of study facility), only facility type showed significant differences in estimates of the prevalence of SNJ in subgroup analysis (Table 6). In meta-regression analysis, publication year (<0.001), country income level (p = 0.009), representativeness of the sample to the target population (p = 0.04), and type of healthcare facility (p = 0.001) significantly explained 17.00% of the between-study heterogeneity in the observed prevalence of SNJ (Table 7).

Table 6.

Prevalence (%) of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) among all hospital admissions according to methodological domains for assessing quality of study.

| N | Estimates (95% Confidence Interval) |

p Value for Test for Subgroup Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 84 | 2.55 (1.93–3.27) | - |

| Sample representative of target population | 0.329 | ||

| All | 57 | 2.39 (1.76–3.10) | |

| Term and near term | 16 | 2.03 (1.04–3.32) | |

| Term only or preterm only | 11 | 4.85 (1.39–10.11) | |

| Method used to define jaundice | 0.749 | ||

| Serum bilirubin | 52 | 2.70 (1.92–3.60) | |

| Clinically | 3 | 1.80 (0.27–4.56) | |

| Not stated | 29 | 2.39 (1.30–3.77) | |

| Study excludes any of the following: G6PD, ABOi, Rhi, Sepsis | 0.055 | ||

| Yes | 4 | 1.20 (0.33–2.59) | |

| No | 80 | 2.64 (1.98–3.39) | |

| Study reported total number of NNJ cases | 0.040 | ||

| Yes | 74 | 2.72 (2.00–3.54) | |

| No | 10 | 1.56 (0.90–2.39) | |

| Was clinically significant jaundice clearly defined in methods (including use of AAP/NICE. etc guidelines)? | 0.646 | ||

| Yes | 45 | 2.42 (1.67–3.30) | |

| No | 39 | 2.71 (1.71–3.93) | |

| Type of healthcare facility | <0.001 | ||

| Tertiary/referral | 68 | 3.01 (2.25–3.86) | |

| Secondary, PHC, community | 2 | 0.62 (0.28–1.08) | |

| Not stated | 14 | 1.06 (0.38–2.06) |

AAP: American Academy of Pediatrics; ABOi: ABO-incompatibility; G6PD: Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; N: Number of studies; nice: National Institute of Health and Care Excellence; NNJ: Neonatal jaundice; PHC: primary health care; References: [6,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97].

Table 7.

Univariate mixed effects meta-regression analysis relating study-level factor and methodological domains for assessing quality of study to the proportion of severe neonatal jaundice (SNJ) among all hospital admissions.

| Estimates (95% Confidence Interval) |

Heterogeneity Accounted for by Factor | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | −0.006 (−0.010, −0.002) | 24.97% | <0.001 |

| Country income level | 50.99% | 0.009 | |

| High | Referent | ||

| Upper-middle | 0.041 (−0.028, 0.111) | ||

| Lower-middle | 0.087 (0.025, 0.149) | ||

| Low | 0.036 (−0.056, 0.153) | ||

| Sample representative of target population | 45.40% | 0.040 | |

| Term only or preterm only | Referent | ||

| Term and near term | −0.075 (−0.136, −0.013) | ||

| All | −0.062 (−0.114, 0.010) | ||

| Method used to define jaundice | 8.39% | 0.831 | |

| Not stated | Referent | ||

| Clinically | −0.021 (−0.140, 0.097) | ||

| Serum bilirubin/AAP/NICE | 0.009 (−0.036, 0.055) | ||

| Study excludes any of the following: G6PDd, ABOi, Rhi, Sepsis | 0.00% | 0.303 | |

| Yes | Referent | ||

| No | 0.055 (−0.050, 0.159) | ||

| Study reported total number of NNJ cases | 14.68% | 0.219 | |

| No | Referent | ||

| Yes | 0.040 (−0.024, 0.104) | ||

| Was clinically significant jaundice clearly defined in methods? | 28.77% | 0.621 | |

| No | Referent | ||

| Yes | −0.010 (−0.048, 0.029) | ||

| Type of healthcare facility | |||

| Not stated | Referent | 59.73% | 0.001 |

| Secondary, PHC, community | −0.024 (−0.124, 0.077) | ||

| Tertiary/referral | 0.070 (0.031, 0.109) |

AAP: American Academy of Pediatrics; NICE: National Institute for Healthcare and Excellence; G6PDd: Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency; ABOi: ABO incompatability; Rhi: Rhesus incompatability; NNJ neonatal jaundice; PHC: Primary Healthcare Center.

A one-year increase in publication year was found to predict a decrease in prevalence of SNJ by 0.6% (coefficient: −0.006 [95% CI: −0.010, −0.002]), indicating more recent studies tended to publish lower prevalence for SNJ compared to earlier published studies. Upper-middle-, lower-middle-, and low-income countries all had a prevalence of SNJ that was 4.10%, 8.70% and 3.60% higher than the prevalence of SNJ reported among high-income countries. Studies conducted on all neonates or term and near-term neonates had 6.20% and 7.50% lower prevalence than studies that only included term only or preterm only respectively. The prevalence of SNJ in tertiary/referral hospitals was 7.0% higher (coefficient: 0.070 [95% CI: 0.031, 0.109]) than studies that did not report type of healthcare facility. In multivariable meta regression analysis, year of publication, income level of country, sample representative of target population (whether it included term, preterm or whole neonate population), method used to define jaundice, study having reported total number of NNJ cases, whether clinically significant jaundice was clearly defined or not together explained 58% of the variation in SNJ prevalence across countries.

4. Discussion

Our data demonstrate that adverse clinical outcomes of SNJ remains a significant public health concern in LMICs. It continues to be a leading cause of neonatal admissions and death. SNJ contributes substantially to neonatal mortality worldwide, with the highest burden in the African (1.49%) and South-East Asian (0.82%) WHO regions. Our study highlights the global prevalence of SNJ with ranges varying from 3.34% in the African and 2.58% in the South-East Asian regions to 1.73%, 1.42%, 1.31% and 0.74% in the Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, European and Western Pacific regions. SNJ is associated with a substantial risk of long-term disability [2,8,9]. Of note, the prevalence declined slowly over time by 0.6% per year.

Focusing only on those with NNJ, our data show a prevalence of SNJ among this cohort ranging between 8.3% and 31.4%, with the highest burden of disease in the Western Pacific and African regions. However, the Western Pacific region was only represented by one report from China (upper middle-income) and the America’s had only five studies [USA-high-income (n = 3), Brazil-upper middle-income (n = 1), Bolivia-lower middle-income (n = 1)]. Despite efforts to find worldwide data there is still selection bias due to underreporting with only 27 of the 195 official countries providing any data at all.

Although still unevenly distributed with many countries without data, our review more accurately represents the global burden of SNJ than previous studies/reviews have done with 64 (76.19%) of the articles from LMICs and an additional 14 articles (16.67%) from upper-middle-income countries. This is a stark contrast to the previous population-based systematic review and meta-analysis, where 76% of the included studies were from high-income countries and, thus, much less representative of the actual income distribution globally than this present study [10]. Our current work included 84 studies representative of all WHO regions, including more country diversity and income levels within most regions.

Additionally, most articles included in our review studied both term and preterm populations. Important because preterm infants have a higher prevalence of NNJ and a higher risk of neurological damage at lower bilirubin levels [27,104]. Of note, studies that included only preterm neonates reported a higher prevalence of SNJ than other studies, however, this difference did not attain statistical significance; an observation differing from other reports [27,105].

This review also reported a higher prevalence of SNJ in higher-tier health facilities when compared to primary and secondary health facilities, possibly because SNJ is usually managed in higher-tier facilities due to these facilities having more phototherapy devices and manpower [105]. The actual burden is likely underreported as many neonates do not reach tertiary centers in LMICs.

The current review highlights that NNJ is noted in 21.99% of all neonatal admissions across WHO regions in the studies included in our review, consistent with prior studies [23,43,82]. Of all neonatal admissions with jaundice, those that had clinical evidence of severe disease ranged from 8.31–31.49% with variability across regions with areas with higher prevalence in regions where neonates often present late to the hospital, likely attributable to previously identified factors [8,106,107].

Striking differences persist between WHO regions for individual SNJ markers again with wide ranges for both ABE and percentages of neonates requiring EBTs. Many complications are likely underreported due to the lack of follow-up and/or the ability to perform specialized testing including BAER or MRI. For these reasons, along with the lack of representation of many countries, we expect that these data significantly underestimate the true burden of severe disease. With known effective treatment strategies, including intensive phototherapy and EBT, likely coupled with maternal education, early timely diagnosis, and treatment [106,108,109], these complications are preventable in almost all neonates.

Our study also looked at other factors potentially associated with SNJ. With the meta-regression, three factors—publication year, type of study facility and country income level accounted for 58% of the heterogeneity. More recent studies tended to report a lower prevalence of SNJ which may reflect modest gains in recently introduced national programs such as the “Every Newborn Action Plan (ENAP)” focusing on newborn risk assessment, identification of cases with prompt referrals, maternal education and postnatal visits and having the potential of reducing behavioral factors that contribute to SNJ [110].

Study limitations include the continued underrepresentation of several regions/countries in this data set and the decision to limit the search to English only based on the lack of any population-based data in other languages in the previous population-based review. Inability to accurately ascertain place of birth and uniformly determine how many neonates were readmissions versus admissions from outside of healthcare facilities. Bilirubin levels were not required because bilirubin levels are not uniformly available in all hospitals and definitions for severe hyperbilirubinemia vary widely. Another limitation of this review is in the observed high degree of heterogeneity of pooled prevalence which is not unexpected for prevalence studies with marked methodological differences. Though we tried to deal with the high heterogeneity by looking at the effect of design, year and population characteristics in the meta-regression, we still found significant heterogeneity. Despite the high heterogeneity, it is clear that the burden of disease remains high, with a much higher proportion of the disease in LMICs. This does not alter the significance of our study as it is a representation of available research done thus far in hospitalized neonates. We also failed to link prevalence of SNJ in this review to the predicted prevalence of long-term sequelae. A disappointing limitation is the small number of studies from three of WHO regions (Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, and Western Pacific), decreasing generalizability of the findings in these regions. Of note, the Americas did have stronger representation in the previous population-based review and did not have a high prevalence of SNJ [10]. This study could have been potentially strengthened by adding additional weighting based on the prevalence of known factors, such as G6PD deficiency, Rhesus disease and neonatal sepsis, which vary among different WHO regions in neonates with SNJ. This additional weighting should be included in future systematic reviews and meta-analyses to help determine the global burden of SNJ. A strength of this study is that it included global data, and most of articles analyzed were adjudged to be of high quality which strengthens the validity of our findings. The relatively high representation from the African, European, and South-East Asian regions and middle-income countries enhances generalizability of our findings to these regions. Overall, this review had better representation than our previous population-based study although attempts to get population-based data should continue.

As we highlighted in the limitations section above, our data demonstrated high heterogeneity but, despite that limitation, provides the best representation of the burden of disease, especially in LMICs/LICs available at this time. Country and regional registries and population data are urgently needed but only largely available in a few high-income countries globally [10]. Should true population-based data become widely available, they will provide more robust and generalizable data. However, if we wait for that population data to come, it will likely be years if not decades before important stakeholders, such as the WHO and United nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), move SNJ to the top of their list of global neonatal priorities. Using mathematical modeling, Bhutani et al. [9] predicted that in 2010, there were 240 million infants at risk for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia-related adverse outcomes, and 750,000 with KSD. With increasing populations in Africa and other LMICs where the burden of SNJ is highest, these estimates will increase if mitigation factors are not implemented. More studies are also needed that factor in the medical standards and risks for developing jaundice in each country along country and even within-country regional-specific guidelines based on the risks and treatment available within a given country or region. As highlighted in American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) 2022 guidelines, and also highlighted in a recent perspective piece, LMICs need to base treatment on their own risks and resources [111,112]. Using AAP guidelines would potentially lead to a substantially higher burden of both ABE and KSD than we currently see in LMICs.

5. Conclusions

SNJ remains an important contributor to neonatal morbidity and mortality, especially in the African and South-East Asian regions. As we work towards the SDGs of improving neonatal mortality and the goal of decreasing morbidity, SNJ needs to be addressed as a preventable cause of both-most effectively addressed with a package approach which includes maternal, community and healthcare provider education; country specific guidelines based on risk and resources; accurate reliable low-cost methods of screening and diagnosis including not only bilirubin levels but also blood grouping and Rhesus as well as G6PD screening, effective phototherapy, capabilities to do safe EBT’s when indicated and comprehensive follow-up and treatment for all children with KSD.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Vinod Bhutani and Yvonne Vaucher for their review of an early version of this manuscript and helpful suggestions for this paper. We also wish to thank Serena Silvaggio for her administrative assistance without which this submission would have been impossible. We also wish to thank the authors of the previous population-based review and the countless others on whose shoulders we stand as we all work hard to eliminate SNJ and the morbidity and mortality it causes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm12113738/s1.

Author Contributions

T.M.S. conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. U.M.D., F.U., L.H., T.O. and F.A., designed the study, collected data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. K.M.S. collected data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. C.J.B. designed the study including the data collection instruments, collected data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. D.A. designed the study, analyzed the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. B.W.L. designed the study, supervised data collection especially the quality assessment aspects and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Usman F., Diala U.M., Shapiro S.M., Le Pichon J.B., Slusher T.M. Acute bilirubin encephalopathy and its progression to kernicterus: Current perspectives. Res. Rep. Neonatol. 2018;8:33–44. doi: 10.2147/RRN.S125758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Pichon J.B., Riordan S., Watchkoe J., Shapiro S.M. The Neurological Sequelae of Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia: Definitions, Diagnosis and Treatment of the Kernicterus Spectrum Disorders (KSDs) Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2017;13:199–209. doi: 10.2174/1573396313666170815100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson L.H., Brown A.K., Bhutani V.K. BIND—A clinical score for bilirubin- induced neurologic dysfunction in newborns. Pediatrics. 1999;199:746–747. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radmacher P.G., Groves F.D., Owa J.A., Ofovwe G.E., Amuabunos E.A., Olusanya B.O., Slusher T.M. A modified Bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction (BIND-M) algorithm is useful in evaluating severity of jaundice in a resource-limited setting. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:28. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0355-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyperbilirubinemia S.O. Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 2004;114:297–316. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Usman F., Farouk Z.L., Ahmed A., Ibrahim M. Comparison of Bilirubin Induced Neurologic Dysfunction Score with Brainstem Auditory Evoked Response in Detecting Acute Bilirubin Encephalopathy in Term Neonates. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2019;13:SC05–SC09. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2019/41670.13382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ip S., Chung M., Kulig J., O’Brien R., Sege R., Glicken S., Maisels M.J., Lau J. An evidence-based review of important issues concerning neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e130–e153. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collaborators GCM Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1725–1774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31575-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhutani V.K., Zipursky A., Blencowe H., Khanna R., Sgro M., Ebbesen F., Bell J., Mori R., Slusher T.M., Fahmy N., et al. Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and Rhesus disease of the newborn: Incidence and impairment estimates for 2010 at regional and global levels. Pediatr. Res. 2013;74:86–100. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slusher T.M., Zamora T.G., Appiah D., Stanke J.U., Strand M.A., Lee B.W., Richardson S.R., Keating E.M., Siddappa A.M., Olusanya B.O. Burden of severe neonatal jaundice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Paediatr. Open. 2017;1:e000105. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olusanya B., A Ogunlesi T., Slusher T.M. Why is kernicterus still a major cause of death and disability in low-income and middleincome countries? Arch. Dis. Child. 2014;99:1117–1121. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hay S.I., Abajobir A.A., Abate K.H. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1260–1344. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32130-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bank W. The World by Income and Region. World Bank; Washington, DC, USA: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmind A.l. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong W.C.W., Cheung C.S.K., Hart G.J. Development of a quality assessment tool for systematic reviews of observational studies (QATSO) of HIV prevalence in men having sex with men and associated risk behaviours. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2008;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman M.F., Tukey J.W. Transformations Related to the Angular and the Square Root. Ann. Math. Stat. 1950;21:607–611. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177729756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barendregt J.J., Doi S.A., Lee Y.Y. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2013;67:974–978. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Begg C.B., Berlin J.A. Publication Bias—A Problem in Interpreting Medical Data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A. 1988;151:419–463. doi: 10.2307/2982993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egger M., Smith G.D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abolghasemi H., Mehrani H., Amid A. An update on the prevalence of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and neonatal jaundice in Tehran neonates. Clin. Biochem. 2004;37:241–244. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adebami O.J., Joel-Medewase V.I., Oyedeji O.A., Oyedeji G.A. A review of neonatal admissions in Osogbo, Southwestern Nigeria. Niger. Hosp. Pract. 2010;5:36–41. doi: 10.4314/nhp.v5i3-4.57848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adebami O.J. Factors associated with the incidence of acute bilirubin encephalopathy in Nigerian population. J. Pediatr. Neurol. 2011;9:347–353. doi: 10.3233/JPN-2011-0485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adhikari S., Rao K.S., B.K. G., Bahadur N. Morbidities and Outcome of a Neonatal Intensive Care in Western Nepal. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2017;15:141–145. doi: 10.3126/jnhrc.v15i2.18203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed S.M., Charoo B.A., Iqbal Q., Ali S.W., Hasan M., Ibrahim M., Qadir G.H. Exchange transfusion through peripheral route. JK-Practitioner. 2005;12:118–120. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akintan P., Fajolu I., Osinaike B., Ezenwa B.N., Ezeaka C.V. Pattern and Outcome of Newborn Emergencies in a Tertiary Center, Lagos, Nigeria. Iran. J. Neonatol. IJN. 2019;10:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arain Y., Banda J.M., Faulkenberry J., Bhutani V.K., Palma J.P. Clinical decision support tool for phototherapy initiation in preterm infants. J. Perinatol. 2020;40:1518–1523. doi: 10.1038/s41372-020-00782-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnolda G., Thein A.A., Trevisanuto D., Aung N., New H.M., Thin A.A., Aye N.S.S., Defechereux T., Kumara D., Moccia L. Evaluation of a simple intervention to reduce exchange transfusion rates among inborn and outborn neonates in Myanmar, comparing pre- and post-intervention rates. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:216. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0530-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atay E., Bozaykut A., Ipek I.O. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in neonatal indirect hyperbilirubinemia. J Trop Pediatr. 2006;52:56–58. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmi042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Audu L.I., Mairami A.B., Otuneye A.T., Mohammed-Nafiu R., Mshelia L., Nwatah V.E., Wey Y. Identifying Modifiable Socio-demographic Risk Factors for Severe Hyperbilirubinaemia in Late Preterm and Term Babies in Abuja, Nigeria. BJMMR. 2016;16:1–11. doi: 10.9734/BJMMR/2016/26551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakhru V.D.R., Bakhru J., Choudhary S. Universal Bilirubin Screening: A new hope to limit exchange transfusion in severe hyperbilirubinemia. Iran. J. Pediatr. 2018;113:285–286. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhat P., Chail A., Srivastava K. Critical appraisal of journal article by psychiatry PG residents using a new module: Impact analysis. J. Clin. Neonatol. 2016;5:153–156. doi: 10.4103/2249-4847.191245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhutani V.K., Wong R.J., Stevenson D.K. Hyperbilirubinemia in Preterm Neonates. Clin. Perinatol. 2016;43:215–232. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bokade C., Meshram R. Morbidity and mortality patterns among outborn referral neonates in central India: Prospective observational study. J. Clin. Neonatol. 2018;7:130–135. doi: 10.4103/jcn.JCN_27_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bozkurt Ö., Yücesoy E., Oğuz B., Akinel O., Palali M.F., Atas N. Severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in the southeast region of Turkey. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020;50:103–109. doi: 10.3906/sag-1906-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bülbül A., Okan F., Ünsür E.K.L., Nuhu L.A. Adverse events associated with exchange transfusion and etiology of severe hyperbilirubinemia in near-term and term newborns. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2011;41:93–100. doi: 10.3906/sag-0911-395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Celik H.T., Günbey C., Unal S., Gumruk F., Yurdakok M. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia: Hacettepe experıence. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2013;49:399–402. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chhapola V., Sharma A.G., Kanwal S.K., Kumar V., Patra B. Neonatal exchange transfusions at a tertiary care centre in north India: An investigation of historical trends using change-point analysis and statistical process control. Int. Health. 2018;10:451–456. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihy045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colak R.C.S., Ergon E.Y., Celik K., Ozdemir S.A., Olukman O., Ustunyurt Z. The Neurodevelopmental outcome of severe Neonatal Hemolytic and Nonhemolytic Hyperbilirubinemia. J. Pediatr. Res. 2020;7:152–157. doi: 10.4274/jpr.galenos.2019.16779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Carvalho M., Mochdece C.C., Sá C.A., Moreira M.E. High-intensity phototherapy for the treatment of severe nonhaemolytic neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Acta Paediatrica. 2011;100:620–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eke C.B., Ezomike U.O., Chukwu B.F., Chinawa J.M., Korie F.C., Chukwudi N., Ukpabi I.K. Pattern of Neonatal Mortality in a Teritiary Health Facility in Umuahia, South East, Nigeria. Int. J. Trop. Dis. Health. 2013;42:136–146. [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Honni N.S., El-Mechabresh M.S., Shlmani M.A., Mersal A.Y. Bilirubin encepahlopathy (kernicterus) among full term Lybian infants. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:s1–s200. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emokpae A.A., Mabogunje C.A., Imam Z.O., Olusanya B.O. Heliotherapy for Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia in Southwest, Nigeria: A Baseline Pre-Intervention Study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0151375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eneh A.U., Oruamabo R.S. Neonatal jaundice in a Special Care Baby Unit (SCBU) in Port Harcourt, Nigeria: A prospective study. Port Harcourt Med. J. 2008;2:110–117. doi: 10.4314/phmedj.v2i2.38906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erdeve O., Okulu E., Olukman O., Ulubas D., Buyukkale g., Narter F., Tunc G., Atasay B., Gultekin N.D., Arsan S., et al. The Turkish Neonatal Jaundice Online Registry: A national root cause analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0193108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eshete A., Abiy S. When Do Newborns Die? Timing and Cause-Specific Neonatal Death in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Referral Hospital in Gedeo Zone: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Pediatr. 2020;2020:8707652. doi: 10.1155/2020/8707652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eze P., Al-Maktari F., Alshehari A.H., Lawani L.O. Morbidities & outcomes of a neonatal intensive care unit in a complex humanitarian conflict setting, Hajjah Yemen: 2017–2018. Confl. Health. 2020;14:53. doi: 10.1186/s13031-020-00297-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ezeaka V.C., Ekure E.N., Iroha E.O., Egri-Okwaji M.T. Outcome of low birth weight neonates in a tertiary health care centre in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2004;33:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ezeaka V.C., Ogunbase A., Awongbemi O., Grange A.O. Why our children die: A review of paediatric mortality in a tertiary centre in Lagos, Nigeria. Niger. Q. J. Hosp. Med. 2005;13:17–21. doi: 10.4314/nqjhm.v13i1.12502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fahmy N., Ramy N., El Houchi S., Abdel-Khalek K., Alsharany W., Tosson A. Outborns or inborns: Clinical audit of the two intensive care units of Cairo University Hospital. Egypt. Pediatr. Assoc. Gaz. 2017;65:10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.epag.2017.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fein E.H., Friedlander S., Lu Y., Pak Y., Sakai-Bizmark R., Smith L.M., Chanty C.J., Chung P.J. Phototherapy for Neonatal Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia: Examining Outcomes by Level of Care. Hosp. Pediatr. 2019;9:115–120. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2018-0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fajolu I.B., Egri-Okwaji M.T.C. Childhood mortality in children emergency centre of the Lagos University Teaching hospital. Niger. J. Paed. 2011;38:131–135. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farouk Z., Ibrahim M., Ogala W.N. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency; the single most important cause of neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia in Kano, Nigeria. Niger. J. Paediatr. 2017;44:44–49. doi: 10.4314/njp.v44i2.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farouk Z.L., Muhammed A., Gambo S., Mukhtar-Yola M., Umar A.S., Slusher T.M. Follow-up of Children with Kernicterus in Kano, Nigeria. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2018;64:176–182. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmx041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hadgu F.B., Gebretsadik L.G., Mihretu H.G., Berhe A.H. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Neonatal Mortality at Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northern Ethiopia. A Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatr. Health Med. Ther. 2020;11:29–37. doi: 10.2147/PHMT.S235591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hakan N., Zenciroglu A., Aydin M., Okumus N., Dursun A., Dilli D. Exchange transfusion for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia: An 8-year single center experience at a tertiary neonatal intensive care unit in Turkey. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1537–1541. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.960832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hameed N.N., Abdul Jaleel R.K., Saugstad O.D. The use of continuous positive airway pressure in preterm babies with respiratory distress syndrome: A report from Baghdad, Iraq. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2014;27:629–632. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.825595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanson C., Singh S., Zamboni K., Tyagi M., Chamarty S., Shukla R., Schellenberg J. Care practices and neonatal survival in 52 neonatal intensive care units in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, India: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haroon A., Ali S.R., Ahmed S., Maheen H. Short-term neonatal outcome in late preterm vs. term infants. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. JCPSP. 2014;24:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Helal N.F., Ghany E., Abuelhamd W.A., Alradem A.Y.A. Characteristics and outcome of newborn admitted with acute bilirubin encephalopathy to a tertiary neonatal intensive care unit. World J. Pediatr. WJP. 2019;15:42–48. doi: 10.1007/s12519-018-0200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ibekwe R.C., Ibekwe M.U., Muoneke V.U. Outcome of exchange blood transfusions done for neonatal jaundice in abakaliki, South eastern Nigeria. J. Clin. Neonatol. 2012;1:34–37. doi: 10.4103/2249-4847.92239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iqbal B.J., Ahmed Q.I., Ali A.A., Ahmed C.B., Asif A., Ikhlas A. Efficacy of different types of phototherapy devices: A 3-year prospective study from Northern India. J. Clin. Neonatol. 2016;5:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Isa H.M., Mohamed M.S., Mohamed A.M., Abdulla A., Abdulla F. Neonatal indirect hyperbilirubinemia and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Korean J. Pediatr. 2017;60:106–111. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2017.60.4.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Israel-Aina Y.T., Omoigberale A.I. Risk factors for neonatal jaundice in babies presenting at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City. Niger. J. Paed. 2012;39:159–163. doi: 10.4314/njp.v39i4.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jajoo M. IDDF2019-ABS-0222 Exchange transfusion in neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and bilirubin encephalopathy: A long way to go. Gut. 2019;68:A149. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-IDDFAbstracts.290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kilicdag H., Gökmen Z., Ozkiraz S., Gulcan H., Tarcan A. Is it accurate to separate glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in neonatal hyperbilirubinemia as deficient and normal? Pediatr. Neonatol. 2014;55:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumar M.N., Thakur S.N., Singh B.B. Study of the morbidity and the mortality patterns in the neonatal intensive care unit at a tertiary care teaching Hospital in Rohtas District, Bihar, India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2012;6:282–285. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Malla T., Singh S., Poudyal P., Sathian B., Nik G., Malla K.K. A Prospective Study on Exchange Transfusion in Neonatal Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia—In a Tertiary Care Hospital, Nepal. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. (KUMJ) 2015;13:102–108. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v13i2.16781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Malik F.R., Amer K., Ullah M., Muhammad A.S. Why our neonates are dying? Pattern and outcome of admissions to neonatal units of tertiary care hospitals in Peshawar from January, 2009 to December, 2011. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2016;66:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mirajkar S., Rajadhyaksha S. Hearing evaluation of neonates with hyperbilirubinemia by otoacoustic emissions and brain stem evoked response audiometry. J. Nepal. Paediatr. Soc. 2016;36:310–313. doi: 10.3126/jnps.v36i3.12155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mmbaga B.T., Lie R.T., Olomi R., Mahande M.J., Kvale G., Daltveit A.K. Cause-specific neonatal mortality in a neonatal care unit in Northern Tanzania: A registry based cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nyangabyaki-Twesigye C., Mworozi E., Namisi C., Nakibuuka V., Kayiwa J., Ssebunya R., Mukose D.A. Prevalence, factors associated and treatment outcome of hyperbilirubinaemia in neonates admitted to St Francis hospital, Nsambya, Uganda: A descriptive study. Afr. Health Sci. 2020;20:397–405. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v20i1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ochigbo S.O., Venn I., Anachuna K. Prevalence of Bilirubin Encephalopathy in Calabar, South-South Nigeria: A Five-year Review Study. Iran. J. Neonatol. IJN. 2016;7:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ogunfowora O.B., Ogunlesi T.A., Ayeni V.A. Factors associated with clinical outcomes among neonates admitted with acute bilirubin and hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathies at a tertiary hospital in south-west Nigeria. South Afr. Fam. Pract. 2019;61:177–183. doi: 10.1080/20786190.2019.1622857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ogunlesi T.A., Dedeke I.O., Adekanmbi A.F., Adekanmbi A.F., Fetga M.B., Ogunfowora O.B. The incidence and outcome of bilirubin encephalopathy in Nigeria: A bi-centre study. Niger. J. Med. 2007;16:354–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ogunlesi T.A., Ogunfowora O.B. Predictors of Acute Bilirubin Encephalopathy Among Nigerian Term Babies with Moderate-to-severe Hyperbilirubinaemia. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2011;57:80–86. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmq045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ogunlesi T.A., Ayeni V.A., Ogunfowora O.B., Jagun E.O. The current pattern of facility-based perinatal and neonatal mortality in Sagamu, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2019;19:3045–3054. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v19i4.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ojukwu J.U., Ogbu C.N. Analysis and outcome of admissions in the Special Care Baby Unit of the Ebonyi State University Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki. Int. J. Med. Health Dev. 2004;9:2. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Okagua J.O.U. Morbidity and Mortality Pattern of Neonates admitted into the Special Care Baby Unit of University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. East Afr. Med. J. 2017;94:259–265. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Okechukwu A.A., Achonwa A. Morbidity and mortality patterns of admissions into the Special Care Baby Unit of University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, Gwagwalada, Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2009;12:389–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Onyearugha C.N., George I.O. Exchange Blood Transfusion in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital. Int. J. Trop. Med. 2014;9:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Osaghae D.O., Ogieva R., Sule R. The Pattern and Outcome of Newborn Admissions in Benin City. Niger. Hosp. Pract. 2013;11:4. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pius S., Bello M., Djossi S., Ambe J.P. Prevalence of exchange blood transfusion in severe hyper- bilirubinaemia and outcome at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital Maiduguri, North-eastern Nigeria. Niger. J. Paed. 2017;44:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Poudel P., Budhathoki S., Shrivastava M.K. Maternal Risk Factors and Morbidity Pattern of Very Low Birth Weight Infants: A NICU Based Study at Eastern Nepal. J. Nepal Paediatr. Soc. 2009;29:59–66. doi: 10.3126/jnps.v29i2.2040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rasul C.H., Hasan M.A., Yasmin F. Outcome of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in a tertiary care hospital in bangladesh. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2010;17:40–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rijal P., Bichha R.P., Pandit B.P., Lama L. Overview of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia at Nepal Medical College Teaching Hospital. Nepal Med. Coll. J. 2011;13:205–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Salih S.A/S., A/Gadir Y.S. Early outcome of pre-term neonates delivered at Soba University Hospital. Sudan. J. Paediatr. 2013;13:37–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Salas A.A., Mazzi E. Exchange transfusion in infants with extreme hyperbilirubinemia: An experience from a developing country. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:754–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Simiyu D.E. Morbidity and mortality of neonates admitted in general paediatric wards at Kenyatta National Hospital. East Afr. Med. J. 2003;80:611–616. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v80i12.8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Simiyu D.E. Morbidity and mortality of low birth weight infants in the new born unit of Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr. Med. J. 2004;81:367–374. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v81i7.9193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Singh S.K., Singh S.N., Kumar M., Tripathi S., Bhriguvanshi A., Chandra T., Kumar A. Etiology and clinical profile of neonates with pathological unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia with special reference to Rhesus (Rh) D, C, and E incompatibilities: A tertiary care center experience. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 2016;4:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2016.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Singla D.A., Sharma S., Sharma M., Chaudhary S. Evaluation of Risk Factors for Exchange Range Hyperbilirubinemia and Neurotoxicity in Neonates from Hilly Terrain of India. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2017;7:228–232. doi: 10.4103/ijabmr.IJABMR_298_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Speleman K., Kneepkens K., Vandendriessche K., Debruyne F., Desloovere C. Prevalence of risk factors for sensorineural hearing loss in NICU newborns. B-ent. 2012;8:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tagare A., Chaudhari S., Kadam S., Vaidya U., Pandit A., Sayyad M.G. Mortality and morbidity in extremely low birth weight (ELBW) infants in a neonatal intensive care unit. Indian J. Pediatr. 2013;80:16–20. doi: 10.1007/s12098-012-0818-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Taghdiri M.M., Eghbalian F., Emam F., Abbasi B., Zandevakili H., Ghale A., Razavi Z. Auditory Evaluation of High Risk Newborns by Automated Auditory Brain Stem Response. Iran. J. Pediatr. 2008;18:330–334. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tette E.M.A., Nartey E.T., Nuertey B.D., Azusong E.A., Akaateba D., Yirifere J., Alandu A., Seneadza A.A.H., Gandau N.B., Renner l.A. The pattern of neonatal admissions and mortality at a regional and district hospital in the Upper West Region of Ghana; a cross sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0232406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Thangavelu K., Martakis K., Fabian S., Venkateswaran M., Roth B., Beutner D., Lang-Roth R. Prevalence and risk factors for hearing loss in high-risk neonates in Germany. Acta Paediatr. 2019;108:1972–1977. doi: 10.1111/apa.14837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thielemans L., Trip-Hoving M., Landier J., Turner C., Prins T.J., Wouda E.M.N., Hanboonkunupakam B., Po C., Beau C., Mu M., et al. Indirect neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in hospitalized neonates on the Thai-Myanmar border: A review of neonatal medical records from 2009 to 2014. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:190. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Turner C., Carrara V., Aye Mya Thein N., Chit Mo Mo Win N., Turner P., Bancone G., White N.J., McGready R., Nosten F. Neonatal intensive care in a Karen refugee camp: A 4 year descriptive study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Udo J.J., Anah M.U., Ochigbo S.O., Etuk i.S., Ekanem A.D. Neonatal morbidity and mortality in Calabar, Nigeria: A hospital-based study. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2008;11:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ugochukwu E.F., Ezechukwu C.C., Agbata C.P., Ezumba I.I. Preterm Admissions in a Special Care Baby Unit: The Nnewi Experience. Niger. J. Paediatr. 2002;29:75–79. doi: 10.4314/njp.v29i3.12027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wouda E.M.N., Thielemans L., Darakamon M.C., Nge A.A., Say W., Khing S., Hanboonkunupakam B., Ngerseng T., Landier J., van Rheenen P.F., et al. Extreme neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia in refugee and migrant populations: Retrospective cohort. BMJ Paediatr. Open. 2020;4:e000641. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang F., Chen L., Shang S., Jiang K. A clinical prediction rule for acute bilirubin encephalopathy in neonates with extreme hyperbilirubinemia: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine. 2020;99:9. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Watchko J.F., Maisels M.J. The enigma of low bilirubin kernicterus in premature infants: Why does it still occur, and is it preventable? Semin. Perinatol. 2014;38:397–406. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Toma B.O., Diala U.M., Ofakunrin A.O.D., Shwe D.D., Abba J., Oguche S. Availability and distribution of phototherapy services and health care providers for neonatal jaundice in three local government areas in Jos, North—Central Nigeria. Niger. J. Paed. 2018;45:1–5. doi: 10.4314/njp.v45i1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Slusher T.M., Day L.T., Ogundele T., Woolfield N., Owa J.A. Filtered sunlight, solar powered phototherapy and other strategies for managing jaundice in low-resource settings. Early Hum. Dev. 2017;114:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Slusher T.M., Zipursky A., Bhutani V.K. A global need for affordable neonatal jaundice technologies. Semin. Perinatol. 2011;35:185–191. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]