Abstract

The typing of a radiation hybrid (RH) panel is generally achieved using a unique primer pair for each marker. We here describe a complementing approach utilizing IRS–PCR. Advantages of this technology include the use of a single universal primer to specify any locus, the rapid typing of RH lines by hybridization, and the conservative use of hybrid DNA. The technology allows the mapping of a clone without the requirement for STS generation. To test the technique, we have mapped 48 BAC clones derived from mouse chromosome 12 which we mostly identified using complex probes. As mammalian genomes are repeat-rich, the technology can easily be adapted to species other than mouse.

INTRODUCTION

Radiation hybrid (RH) mapping has tremendously accelerated the pace at which chromosomal maps can be constructed. Conceived at a time when DNA technology was still in its infancy by Goss and Harris (1), the concept was revived 15 years later by Cox and co-workers (2) who irradiated somatic cell hybrid lines containing single human chromosomes before fusing them to HPRT-deficient hamster cells. Subsequently, RH maps of several human chromosomes based on the approach of Cox et al. were constructed, for instance of chromosome 16 and X (3,4). It was Walter et al. (5) who returned to the original Goss and Harris protocols and presented a panel of cell hybrids that they had constructed by fusion of irradiated diploid human fibroblasts with hamster cells. Since then, whole-genome RH panels have been constructed and characterized for a variety of mammalian species other than human, including pig (6,7), cow (8), rat (9,10), dog (11,12), cat (13) and mouse (14–17).

Once a panel has been characterized and a dense framework map is available, it ideally suits the requirements for large-scale high-resolution mapping. To place a new marker on an RH map, all that is needed is an assay to determine the presence of a particular sequence in the individual hybrids. Co-retention with markers previously assayed on the panel can be used to map new markers.

Using the mouse as our model system, we demonstrate here the usefulness of interspersed repetitive sequence (IRS)–PCR with respect to mapping on whole genome RH panels. IRS–PCR exploits the frequent occurrence of repeat elements in the genome of mammals. For instance, a single primer that anneals to the B1 repeat sequence is able to amplify several thousand different fragments from a mouse genomic DNA template. IRS–PCR was originally developed for the species-specific amplification of sequences from somatic cell hybrids (18), and subsequently served as the technological platform for high-throughput genetic and physical mapping in the mouse (19–24).

We here employ complex probes generated by IRS–PCR to identify BAC clones from one specific mouse chromosome. Subsequently, using IRS–PCR fragments derived from these clones, the mouse T31 RH panel is typed by hybridization and the clones thereafter integrated into the RH framework map.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA

DNA from the T31 mouse whole genome radiation hybrid panel was purchased from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL). DNA from hybrid N2C1 (25) that contained mouse chromosome 12 on a human background was a gift from Dr Phil Avner (Institute Pasteur, Paris, France).

IRS–PCR

PCR amplification from cell hybrid DNA (5 ng) or genomic mouse DNA (50 ng) was carried out under conditions described previously (23), using 1 µg of B1-repeat primer B1R (5′-AGTTCCAGGACAGCCAGGGCTAYACAGA-3′; ref. 23) in a 60 µl reaction. The amplification of IRS–PCR fragments from BAC colonies or purified BAC-DNA was carried out as described (23).

Filter generation and hybridization

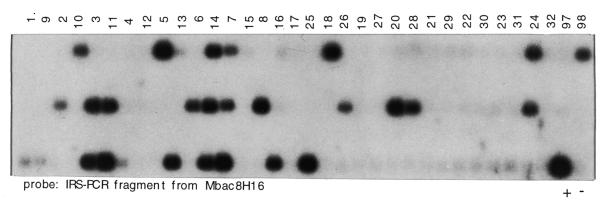

For the preparation of Southern blots, 5 µl of complex IRS–PCR product from each RH line was run on 1% agarose gels. A distance of 1.5 cm between gel combs allowed us to assemble all 100 RH lines plus controls on a filter the size of 16 × 4.5 cm (Fig. 1). Alkaline blotting was carried out according to standard procedures (23). Colony filters from a mouse BAC library (B.Birren, unpublished) were produced on robotic equipment in-house (26). For the preparation of hybridization probes, BAC-derived IRS–PCR fragments were run and cut out from 1.2% SeaPlaque GTG low melt agarose (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, ME). For the preparation of complex probes, 20 ng of unpurified IRS–PCR reaction product prepared from DNA of cell hybrid N2C1 was used. Radioactive labeling was carried out using the random priming method (27). Prior to hybridization, probes were pre-associated with an excess of sheared unlabeled genomic mouse DNA as described (23). Southern blots from the RH panel were hybridized inside 15 ml plastic tubes. Library filters (22 × 22 cm) were sealed into plastic bags. Hybridization was carried out in Church buffer (28) in a 65°C water-bath for 16 h. After hybridization, filters were washed at 65°C for 60 min each in 2× SSC/0.1% SDS and 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS. Exposure against X-ray film was from 1 day (RH panel) up to 1 week (complex probes) at room temperature.

Figure 1.

Typing of the mouse whole genome RH panel by hybridization. Inter B1 repeat PCR was carried out on the 100 cell lines of the mouse T31 panel, and mouse and hamster controls. Individual samples were loaded onto a gel with three comb rows at 1.5 cm spacing and used to prepare a Southern blot. Top row, hybrid lines 1–32, 97, 98; middle row, lines 33–64, 99, 100; bottom row, lines 63–96, positive control 129aa (indicated with +), negative control hamster A23 (indicated with –). Hybridization probe is an IRS–PCR-fragment from mouse BAC clone mbac8h16.

Data entry and evaluation

Autoradiograms from RH panel hybridizations were entered into our database using a scoring tool developed in-house. Data were matched against the T31 marker framework (17) using the RH Map server at the Whitehead Institute Center for Genome Research (www-genome.wi.mit.edu/mouse_rh/index.html ).

RESULTS

Using DNA from the cell hybrid N2C1 that carried mouse chromosome 12 (MMU12) on a human background (25), IRS–PCR was carried out with the mouse B1-specific primer B1R. The complex reaction product was labeled radioactively and hybridized against a mouse BAC library. Out of 27 000 clones screened approximating one genome equivalent, 110 positive clones were identified and retrieved from a picking copy of the library. Thirty-two of the clones were found to contain a repeat element and were excluded from further analysis. Next, IRS–PCR was carried out on the remaining 78 clones to obtain probes for hybridization. Likewise, IRS–PCR was carried out on cell hybrid N2C1 plus suitable positive and negative controls for the preparation of Southern blots. Of 78 clones, 66 (85%) gave a positive signal with the N2C1 cell hybrid and could therefore be assumed to be correctly derived from MMU12 (data not shown). In order to place these 66 clones relative to the RH framework map of the mouse genome (17), DNA from each of the 100 hybrid lines that are comprised within the T31 mouse whole genome RH panel plus mouse and hamster controls were amplified by IRS–PCR and used to prepare Southern blots (Fig. 1). Of the 66 clones tested, 44 could be placed relative to the RH framework map of MMU12 at a LOD threshold of or exceeding 10 (Table 1). Two markers mapped to MMU12 at a LOD threshold of 8. The remainder of IRS-fragments resulted in either weak hybridization signals or gave smeary hybridization results on the T31 panel (11 probes), mapped to multiple chromosomes (2 probes), or did not link to a framework marker at a LOD threshold as low as 7 (3 probes). Four markers out of 66 mapped to a chromosome other than MMU12 at a significant LOD threshold.

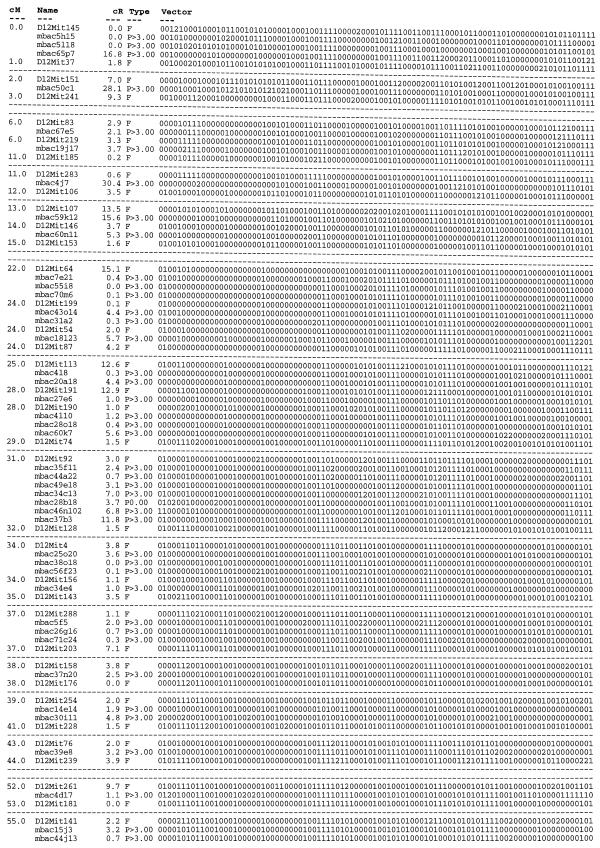

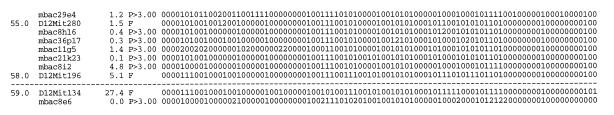

Table 1. Placement map of mouse chromosome 12 (MMU12).

Primary data were generated by hybridization of clone-derived IRS–PCR fragments against the T31 RH panel. Fragments that indicated linkage to MMU12 at a LOD threshold of 10 or greater were placed on the framework map (17). Fourty-four of the placed mouse BAC clones originate from characterization of clones identified by hybridization with chromosome-specific complex probes. Clones mbac25o20, mbac30i11, mbac39e8, mbac4d17 are derived from other sources (H.Himmelbauer, unpublished). Column designations: cM, positions of framework markers on the consensus map of MMU12 (www.informatics.jax.org/bin/ccr ) in Centi-Morgan; name, marker name; cR, distance between markers expressed in Centi-Rays; Type, F is a framework marker (17), P indicates a marker placed in this study followed by the likelihood of the determined interval position; Vector, scores on the hybrid lines: 1, positive; 0, negative; 2, unknown or ambiguous. Displayed are only intervals of the framework map that contain placed markers (flanking framework markers plus placed markers). A single dashed line indicates a gap between intervals with placed markers that on the genetic map are 2 cM at the most. Two dashed lines indicate a gap larger than 2 cM on the genetic map.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated here the feasibilty to type a whole genome RH panel by hybridization using IRS–PCR. The procedure that we describe offers some advantages in comparison to current STS-based approaches of RH mapping. First, a single primer is sufficient to map a number of markers on the panel. Second, one single hybridization is sufficient to generate the required typing data on a panel of 100 RH lines. Third, the technology is extremely conservative concerning the consumption of RH line DNA. Starting with 5 ng of hybrid DNA that is initially used for an IRS–PCR reaction, the resulting amplification product provides sufficient material to type (conservatively estimated) 100 markers.

Using complex probes for clone identification, we have succeeded to place almost 50 BAC clones onto the RH framework map of MMU12 (Table 1). It is clear that this chromosome must contain many more IRS fragments that can be generated by PCR with primer B1R. However, the product that emerges as the outcome of a complex PCR reaction does not contain equal amounts of each individual amplified fragment. Rather, there is a strong bias towards some fragments that amplify preferentially and these will hybridize most strongly to the library filter.

When DNA from an RH line is amplified with primer B1R, the primer will not only amplify mouse sequences, but from the hamster background as well. This does not interfere with hybridization-based typing of the panel, because the positions of B1 elements in the mouse and hamster genomes, respectively, are not evolutionarily conserved. This is in contrast to STS-based RH panel typing, which frequently suffers from co-amplification of hamster background. In the context of another project, we have tested many hundreds of different mouse-derived IRS–PCR fragments on Southern blots that included IRS-products from hamster DNA, but observed cross-hybridization with hamster DNA only very rarely (<1% of cases).

While genetic mapping employing IRS–PCR requires the existence of highly inbred strains of a specific species, this is not a limiting constraint for RH mapping. Since a high content in dispersed repeat sequences has emerged to be a common feature of mammalian genomes, our method therefore makes IRS–PCR amenable to genome mapping in species other than rodents, such as farm animals (cow, pig), cat and dog.

For mapping markers on an RH panel following our strategy, it is necessary that the target contains repeat sequences located at short distance. Our method will therefore be most valuable if mapping of genomic clones is the primary focus. Projects in this context could be large-scale sequencing efforts, gene-mapping via genomic clone intermediates (23) or the construction of clone contigs, which require cost-effective protocols to rapidly either establish or confirm the location of large numbers of clones in the genome. In particular, mouse genomic sequencing has barely begun and a substantial amount of sequence-ready BAC clone contigs will be established from the YAC maps that are existing (29) or under development (L.C.Schalkwyk, H.Lehrach, H.Himmelbauer, in preparation). Similarly, other mammalian genomes that at least in part will be subjected to high-resolution physical mapping and genomic sequence determination (e.g. farm animal genomes) should greatly benefit from the procedure described.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Martina Hopp, Ilona Dunkel, Sabine Scheel and Jutta Piefke for excellent technical assistance, Markus Kramer for computing assistance and Dr Margit Burmeister for comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to Phil Avner for supplying DNA from hybrid cell line N2C1. This work was supported by the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goss S.J. and Harris,H. (1975) Nature, 255, 680–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox D.R., Burmeister,M., Price,E.R., Kim,S. and Myers,R.M. (1990) Science, 250, 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ceccherini I., Romeo,G., Lawrence,S., Breuning,M.H., Harris,P.C., Himmelbauer,H., Frischauf,A.M., Sutherland,G.R., Germino,G.G. et al. (1992) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 104–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumlien J., Grigoriev,A., Roest-Crollius,H., Ross,M., Goodfellow,P.N. and Lehrach,H. (1996) Mamm. Genome, 7, 758–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter M.A., Spillett,D.J., Thomas,P., Weissenbach,J. and Goodfellow,P.N. (1994) Nature Genet., 7, 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yerle M., Pinton,P., Robic,A., Alfonso,A., Palvadeau,Y., Delcros,C., Hawken,R., Alexander,L., Beattie,C., Schook,L., Milan,D. and Gellin,J. (1998) Cytogenet. Cell Genet., 82, 182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawken R.J., Murtaugh,J., Flickinger,G.H., Yerle,M., Robic,A., Milan,D., Gellin,J., Beattie,C.W., Schook,L.B. and Alexander,L.J. (1999) Mamm. Genome, 10, 824–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Womack J.E., Johnson,J.S., Owens,E.K., Rexroad,C.E.,III, Schlapfer,J. and Yang,Y.P. (1997) Mamm. Genome, 8, 854–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe T.K., Bihoreau,M.T., McCarthy,L.C., Kiguwa,S.L., Hishigaki,H., Tsuji,A., Browne,J., Yamasaki,Y., Mizoguchi-Miyakita,A., Oga,K. et al. (1999) Nature Genetics, 22, 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steen R.G., Kwitek-Black,A.E., Glenn,C., Gullings-Handley,J., Van Etten,W., Atkinson,O.S., Appel,D., Twigger,S., Muir,M., Mull,T. et al. (1999) Genome Res., 9, AP1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Priat C., Hitte,C., Vignaux,F., Renier,C., Jiang,Z., Jouquand,S., Cheron,A., Andre,C. and Galibert,F. (1998) Genomics, 54, 361–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vignaux F., Hitte,C., Priat,C., Chuat,J.C., Andre,C. and Galibert,F. (1999) Mamm. Genome, 10, 888–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy W.J., Menotti-Raymond,M., Lyons,L.A., Thompson,M.A. and O’Brien,S.J. (1999) Genomics, 57, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmitt K., Foster,J.W., Feakes,R.W., Knights,C., Davis,M.E., Spillett,D.J. and Goodfellow,P.N. (1996) Genomics, 34, 193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schalkwyk L.C., Weiher,M., Kirby,K., Cusack,B., Himmelbauer,H. and Lehrach,H. (1998) Mamm. Genome, 9, 807–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott R.W., Manly,K.F. and Hohman,C. (1999) Genomics, 57, 365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Etten W.J., Steen,R.G., Nguyen,H., Castle,A.B., Slonim,D.K., Ge,B., Nusbaum,C., Schuler,G.D., Lander,E.S. and Hudson,T.J. (1999) Nature Genet., 22, 384–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson D.L., Ledbetter,S.A., Corbo,L., Victoria,M.F., Ramirez-Solis,R., Webster,T.D., Ledbetter,D.H. and Caskey,C.T. (1989) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 6686–6690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox R.D., Copeland,N.G., Jenkins,N.A. and Lehrach,H. (1991) Genomics, 10, 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter K.W., Ontiveros,S.D., Watson,M.L., Stanton,V.P.,Jr, Gutierrez,P., Bhat,D., Rochelle,J., Graw,S., Ton,C., Schalling,M. et al. (1994) Mamm. Genome, 5, 597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarthy L., Hunter,K., Schalkwyk,L., Riba,L., Anson,S., Mott,R., Newell,W., Bruley,C., Bar,I., Ramu,E., Housman,D., Cox,R. and Lehrach,H. (1995) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 5302–5306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter K.W., Riba,L., Schalkwyk,L., Clark,M., Resenchuk,S., Beeghly,A., Su,J., Tinkov,F., Lee,P., Elango,R. et al. (1996) Genome Res., 6, 290–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Himmelbauer H., Wedemeyer,N., Haaf,T., Wanker,E.E., Schalkwyk,L.C. and Lehrach,H. (1998) Mamm. Genome, 9, 26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nock C., Gauss,C., Schalkwyk,L.C., Klose,J., Lehrach,H. and Himmelbauer,H. (1999) Electrophoresis, 20, 1027–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabile A., Poras,I., Cherif,D., Goodfellow,P. and Avner,P. (1997) Mamm. Genome, 8, 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehrach H., Drmanac,R., Hoheisel,J., Larin,Z., Lennon,G., Monaco,A.P., Nizetic,D., Zehetner,G. and Poustka,A. (1990) In Davies,K.E. and Tilghman,S.M. (eds), Genome Analysis. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, Vol. 1, pp. 39–81.

- 27.Feinberg A.P. and Vogelstein,B.A. (1983) Anal. Biochem., 132, 6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Church G.M. and Gilbert,W. (1984) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 81, 1991–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nusbaum C., Slonim,D.K., Harris,K.L., Birren,B.W., Steen,R.G., Stein,L.D., Miller,J., Dietrich,W.F., Nahf,R., Wang,V. et al. (1999) Nature Genet., 22, 388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]