Abstract

Aims

To define a stepwise application of left bundle branch pacing (LBBP) criteria that will simplify implantation and guarantee electrical resynchronization. Left bundle branch pacing has emerged as an alternative to biventricular pacing. However, a systematic stepwise criterion to ensure electrical resynchronization is lacking.

Methods and results

A cohort of 24 patients from the LEVEL-AT trial (NCT04054895) who received LBBP and had electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI) at 45 days post-implant were included. The usefulness of ECG- and electrogram-based criteria to predict accurate electrical resynchronization with LBBP were analyzed. A two-step approach was developed. The gold standard used to confirm resynchronization was the change in ventricular activation pattern and shortening in left ventricular activation time, assessed by ECGI. Twenty-two (91.6%) patients showed electrical resynchronization on ECGI. All patients fulfilled pre-screwing requisites: lead in septal position in left-oblique projection and W paced morphology in V1. In the first step, presence of either right bundle branch conduction delay pattern (qR or rSR in V1) or left bundle branch capture Plus (QRS ≤120 ms) resulted in 95% sensitivity and 100% specificity to predict LBBP resynchronization, with an accuracy of 95.8%. In the second step, the presence of selective capture (100% specificity, only 41% sensitivity) or a spike-R <80 ms in non-selective capture (100% specificity, sensitivity 46%) ensured 100% accuracy to predict resynchronization with LBBP.

Conclusion

Stepwise application of ECG and electrogram criteria may provide an accurate assessment of electrical resynchronization with LBBP (Graphical abstract).

Keywords: Left bundle branch pacing, Criteria, Electrocardiographic imaging, Cardiac resynchronization, Electrical resynchronization

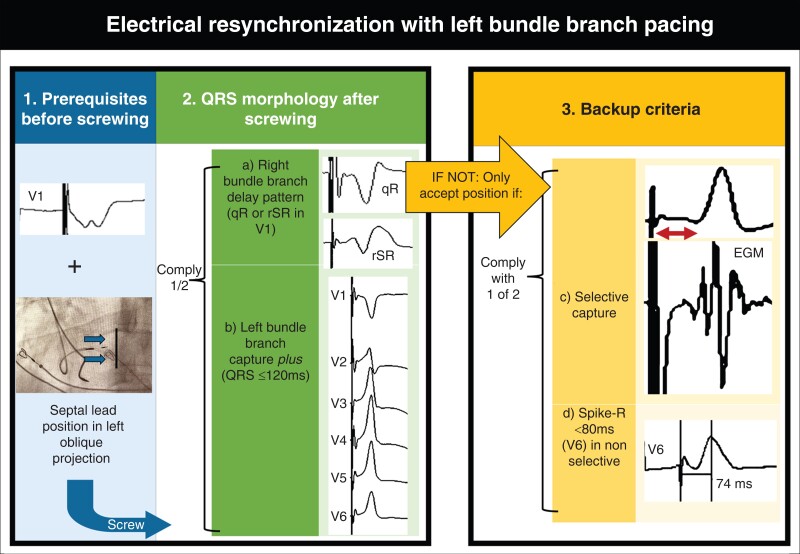

Graphical Abstract

Graphical abstract.

Electrocardiographic- and electrogram-based stepwise approach for electrical resynchronization with left bundle branch pacing. QRS should be measured from the start of fast deflection in left bundle branch capture Plus (QRS ≤120 ms).

What’s New?

Although various authors have proposed criteria to ensure left bundle branch pacing (LBBP), the published algorithms are complex and difficult to implement.

Left bundle branch capture-Plus criterion, provides excellent diagnostic accuracy for electrical resynchronization when applied in combination with the right bundle branch delay morphology criterion (qR or rSR in V1).

A stepwise approach is proposed to deploy the lead, ensuring electrical resynchronization with LBBP.

Introduction

Left bundle branch pacing (LBBP) has emerged1 as an alternative to biventricular pacing (BiVP) and conventional right ventricular (RV) apical pacing.2–4 Observational studies5–11 have shown that LBBP is a feasible and safe approach, achieving lower thresholds than His bundle pacing (HBP).12 It may be successful in blocks that are too distal to be treated with HBP and it also facilitates atrioventricular (AV) junction ablation, which can be challenging with HBP.13 The LEVEL-AT trial14 showed non-inferiority of conduction system pacing (CSP) compared with BiVP. Moreover, LBBP was not inferior to HBP with respect to left ventricular electrical resynchronization and acute hemodynamic response.15 However, LBBP implantation is still a challenge. The lack of systematic application of left bundle branch (LBB) capture criteria complicates decision-making during implantation.16–20 The aim of this study was to propose an implant criterion and a stepwise approach for LBBP implantation that facilitates the procedure and ensures electrical resynchronization with LBBP.

Methods

Study design

Of 25 consecutive patients (September 2019 to June 2021) who received LBBP in the LEVEL-AT trial14 (LEft VEntricuLar Activation Time Shortening with Physiological Pacing vs. Biventricular Resynchronization Therapy NCT04054895), all but one (who changed residence during follow-up) underwent electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI) (CardioInsight™ Medtronic, Minneapolis USA) at 45 days post-implant (Figure 1A Flowchart; Table 1Supplementary material online).

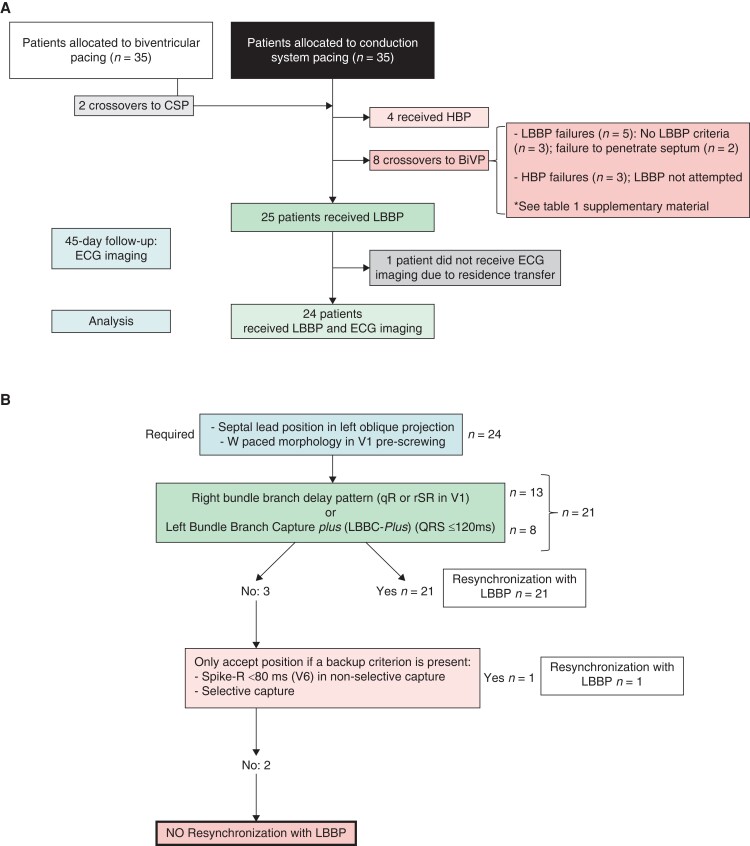

Figure 1.

(A). Flowchart of the patients included in the study, from the LEVEL-AT trial. (B) Diagnostic algorithm. BiVP: biventricular pacing; CSP: conduction system pacing; HBP: His bundle pacing; LBBP: left bundle branch pacing.

Table 1.

Baseline data

| n = 24 | |

|---|---|

| Female, % (n) | 37.5% (9) |

| Age, years | 65 ± 9 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy, % (n) | 33.3% (8) |

| Glomerular filtration <45 mL/min, % (n) | 16.7% (4) |

| QRS width, ms | 174 ± 24 |

| LBBB, % (n) | 66.7% (16) |

| Nonspecific intraventricular delay, % (n) | 8.3% (2) |

| Atrioventricular block (no upgrade), % (n) | 8.3% (2) |

| Upgrades, % (n) | 16.7% (4) |

| Permanent atrial fibrillation, % (n) | 16.7% (4) |

| NYHA functional class | 2.2 ± 0.7 |

| LVEF, % | 27 ± 7% |

| LV end-diastolic volume, ml | 198 ± 111 |

| LV end-systolic volume, ml | 143 ± 103 |

LBBB, left bundle branch block; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

LEVEL-AT inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, symptomatic patients with heart failure on optimal medical treatment with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35%, and wide QRS [left bundle branch block (LBBB) ≥130 ms or QRS ≥150 ms in non-LBBB] or an indication for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) due to AV block and cardiac dysfunction. Exclusion criteria were myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or cardiac revascularization within 3 months before assessment, pregnancy, or participation in other clinical trials.

The LEVEL-AT protocol was approved by the Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Reg.HCB/2019/0576) and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Procedure

The CSP lead was placed in the deep septum to pace the LBB, using a SelectSecure 3830 pacing lead, delivered by a fixed-curve C315-His sheath or a SelectSite C304-HIS deflectable catheter (Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA). Intracavitary signals were recorded in unipolar mode. QRS interval was measured from the start of fast deflection, rather than from the pacing spike as reported previously21,22 (at a screen speed of 300 mm/s) to avoid the latency time of the activation, i.e. not contributing to contraction. The 12 leads of the surface ECG were recorded simultaneously and displayed in vertical alignment on the screen.21,23 The QRS onset was the start of fast deflection, considering all 12 leads. QRS measurements were performed using digitally stored computerized recordings (EP-TRACER, Schwarzer CardioTek, Germany).

In 10/24 (41.6%) patients, LBBP was anatomically located 1 to 1.5 cm distal to the His signal in a right anterior oblique projection; subsequently, the lead was positioned towards the septum in a left oblique projection. In the remaining patients (14/24, 58.3%), the lead was directly placed in the septum using left oblique projection. Before screwing a ‘W’ pattern in V1 with unipolar pacing was pursued, as described by Huang W et al.17 The sheath was rotated counterclockwise to maintain the lead tip perpendicular to the septum. Septal orientation with left anterior oblique projection was guaranteed in all the patients before screwing. Two prerequisites had to be met in all the patients before lead screwing: septal lead in left oblique projection and W paced morphology in V1. The pacing lead was rotated clockwise to obtain fixation, controlling impedance. Thresholds <2.5 V at 1 ms were required for acceptance of the lead position.

The decision to accept a lead position as indicative of LBBP was based on previously described criteria and detailed in the LEVEL-AT trial14: paced morphology of right bundle branch delay in V1 (qR or rSR)16,17,24; narrow QRS (≤120 ms)25; selective capture, defined as an isoelectric segment between the pacing spike and QRS onset16,17,24; left ventricular activation time in V6 ≤85 ms (from the stimulus artifact to peak R wave in lead V6)16,18; recording of LBB potential17; visualization of both components (selective LBB and myocardial-only) of the paced QRS complex with programmed pacing.26

After the procedure, the AV interval was optimized with electrocardiography whenever intrinsic conduction was preserved with the fusion-optimized intervals method.7,23,27 This aimed to shorten the QRS by allowing fusion with intrinsic right bundle ventricular activation, adjusting the AV interval that resulted in the shortest QRS.

Criteria analysis

The following five criteria during implantation were analyzed to establish their accuracy in predicting LBBP resynchronization, assessed with ECGI: (i) qR or rSR in V116,17,24; (ii) R in V1 or V224; (iii) presence of selective capture (defined as isoelectric segment between spike and QRS, along with a discrete local component separate from the stimulus artifact on the unipolar electrogram from the LBBP lead)16,17,24; (iv) spike-R ≤85 ms in V616,18 in non-selective capture; and (v) qR or rSR in V1 or LBB capture Plus (LBBC-Plus). LBBC-Plus is defined as a pattern of narrow QRS (≤120 ms) resulting from simultaneous capture of right and LBBs25 (Figure 2).

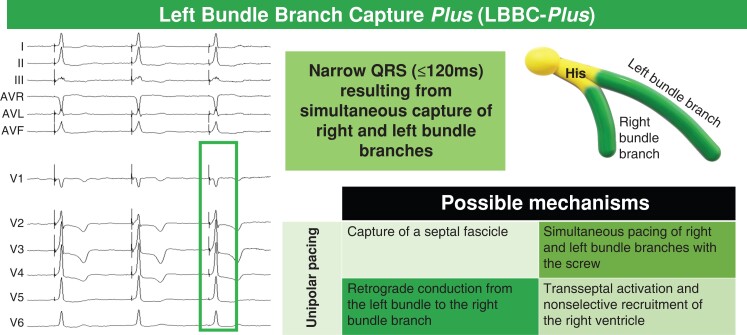

Figure 2.

Left bundle branch capture plus (LBBC-Plus) criterion. LBBC-Plus was described as a narrow QRS (≤120 ms)25 obtained with monopolar pacing, without fusion with intrinsic conduction; it shows a pattern characterized by a Q wave in V1 without right bundle branch delay morphology. The physiologic basis for this phenomenon is incompletely understood; potential mechanisms included in the figure.

Electrocardiographic imaging

Left ventricular activation was assessed with the noninvasive 3-dimensional (3D) mapping system CardioInsight™ (Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA) at 45 days post-implant. The multi-electrode ECGI vest was placed on the thorax after ensuring that the patient’s torso had been completely shaved. The patient was positioned supine on a flat bed. Signal acquisition was performed to obtain ventricular activation from the 252 electrocardiogram sensors in baseline conditions (device OFF or only-right-ventricular-pacing if the patient was pacemaker-dependent) and final programming. After signal acquisition, a computerized tomography scan was performed and segmented with the vest in place to obtain the 3D location of each sensor and the detailed anatomy of the epicardial surface of the heart. From these data, the system applies mathematical algorithms to the geometrical information to transform the measured body surface signals into epicardial signals by solving the inverse-electrocardiography problem. As a result of this process, activation and propagation maps of both ventricles were obtained. The anterior descending artery was segmented to establish the limit between the right and left ventricle (LV). All ECGI was performed by an electrophysiologist (M.P.L.) and a biomedical engineer (P.G.) who had received specific training.

The LV activation time measurement has been previously described.14 In brief, ECGI maps showed the LV activation sequence with the earliest and latest activation points. Total LV activation time was calculated as the time elapsed between the earliest and latest activation points of the isochrones determined by the system. Electrical resynchronization with LBBP was defined with ECGI as a change in activation pattern as compared to the baseline with early activation of the septal area28 and shortening of the left ventricular activation time.29

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were presented as the mean ± SD. Qualitative variables were expressed as the number of cases and proportions. To assess the performance of each diagnostic criterion, we computed sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and accuracy. All 24 patients were included in the analysis. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was applied, with Youden's criteria, to define the optimum cut-off value of the spike-R criterion in non-selective capture.

Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.1.0 for Windows (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean age was 65 ± 9 years, 37.5% were women and 33.3% had ischemic cardiomyopathy; baseline QRS interval was 174 ± 24 ms. Four patients (16.7%) were upgraded from RV pacing due to a low LV ejection fraction.

Twenty-two (91.6%) patients showed electrical resynchronization with LBBP in the ECGI (Figure 3). All 22 patients showed shortening of LV activation time (mean shortening of -39.9 ± 17 ms, minimum shortening of -16 ms) and change in activation pattern as compared to the baseline with early activation of the septal area. In two patients, ECGI showed lack of electrical resynchronization with LBBP (Figure 4). Mean LV activation time in patients with electrical resynchronization was 59.8 ± 16 ms; mean LV activation time in the two patients with lack of electrical resynchronization was 92.5 ± 22 ms (P = 0.013).

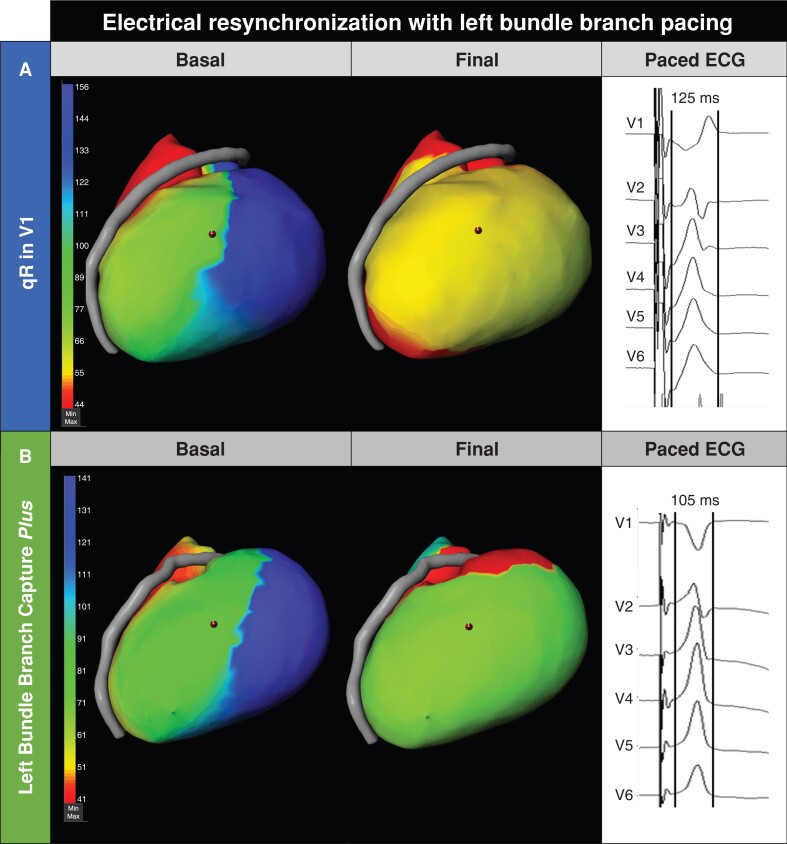

Figure 3.

Electrical resynchronization with left bundle branch pacing. Examples of electrocardiographic imaging showing electrical resynchronization in a patient with ECG with a qR pattern and QRS of 125 ms (A) and a patient with LBBC-Plus criterion and a QRS of 105 ms (B). At baseline, both patients presented with delayed activation of the lateral left ventricular wall. LBBP obtained a faster activation of the left ventricle. Laterolateral projection is shown. The anterior descending artery separates right ventricle from left ventricle.

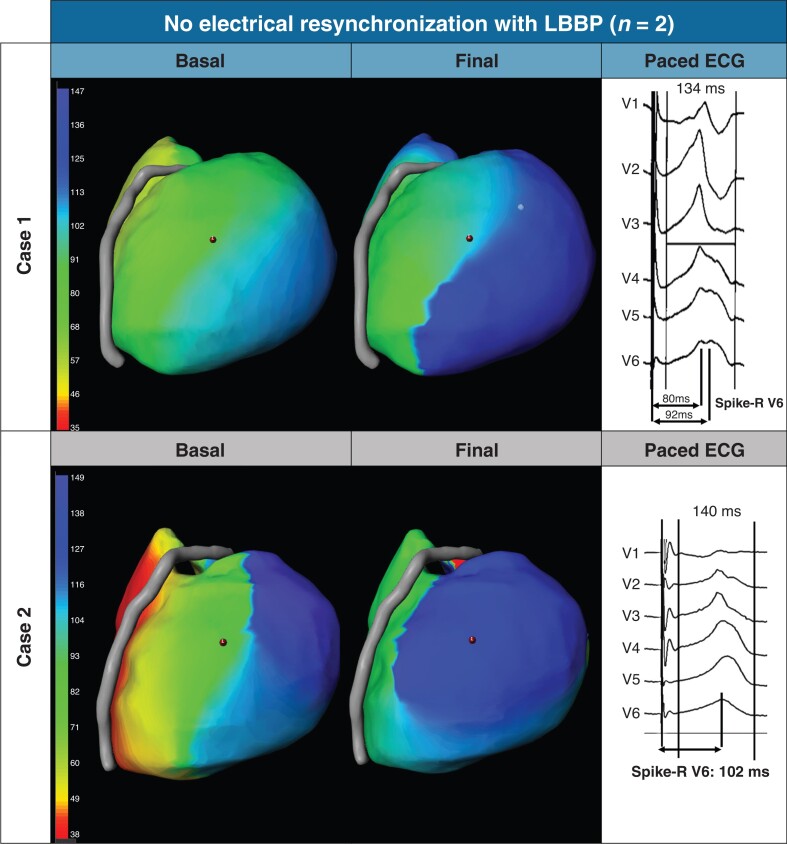

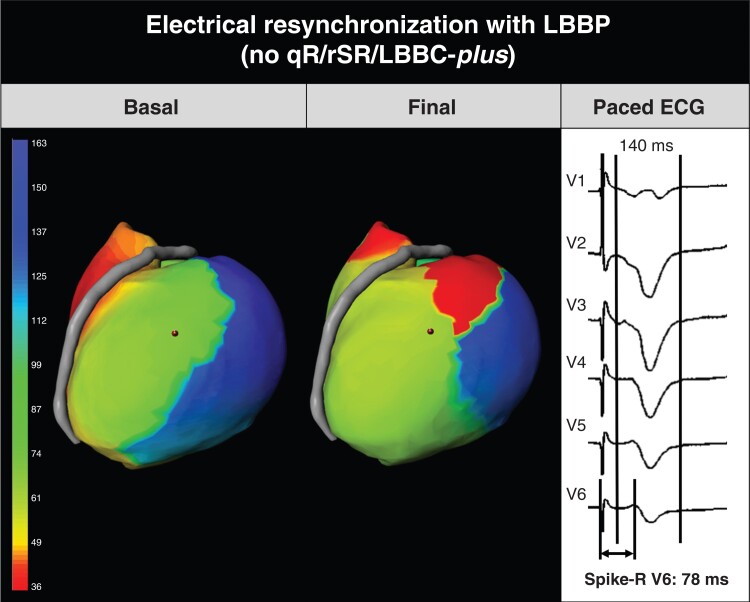

Figure 4.

Cases with no electrical resynchronization with left bundle branch pacing. Case 1: The patient was a crossover from failed biventricular pacing. The ECG did not show the qR/rSR/LBBC-Plus criteria and the spike-R was not <80 ms (notched QRS with two peaks: 80 ms and 92 ms). Case 2, showing lack of electrical resynchronization with ECGI: Patient did not meet the qR/rSR/LBBC-Plus criteria and showed a spike-R in V6 of 102 ms; the operator left the electrode in this position for clinical reasons after narrowing the QRS from 180 to 140 ms. LBBP: left bundle branch pacing. LBBC-Plus: left bundle branch capture Plus.

Means of paced QRS were 121 ± 14 ms and 154 ± 21 ms measured from start of fast deflection and from the spike, respectively. Mean paced QRS in LBBC-Plus (QRS ≤120 ms) was 110 ± 12 ms measured from start of fast deflection, as previously described,25 and 137 ± 11 ms measured from the spike. Mean stim-to-peak R wave in patients with LBBC-Plus was 78 ± 12 ms.

Right bundle branch conduction delay pattern (qR or rSR in V1) criterion showed a sensitivity of 59.1% and specificity of 100% to predict electrical resynchronization with LBBP. If this criterion is combined with the LBBC-Plus criterion, sensitivity increases to 95.5%, specificity of 100%, positive predictive value of 100%, negative predictive value of 67%, and diagnostic accuracy of 95.8%. All the patients that fulfilled qR/rSR/LBBC-Plus criterion had LBBP electrical resynchronization in the ECGI.

The remaining criteria analyzed showed lower sensitivity than qR/rSR/LBBC-Plus (Table 2); selective capture showed 100% specificity but with a low sensitivity (41%). The spike-R ≤85 ms showed only 77% sensitivity and 50% specificity. A ROC curve provided a cut-off of <80 ms showing a 100% specificity, at the expense of a lower sensitivity (46%). R in V1 or V2 had lower sensitivity (86.4%) and specificity (50%) as compared to the qR/rSR/LBBC-Plus.

Table 2.

Diagnostic performance characteristics of electrical resynchronization with left bundle branch pacing criteria

| n (patients with the criterion) | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Diagnostic Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qR or rSR in V1 or LBBC-Plus25 | 21 | 95.5% | 100% | 100% | 67% | 95.8% |

| Spike-R <80 ms in non-selective capture | 6 | 46% | 100% | 100% | 22% | 53.3% |

| Selective capture | 9 | 41% | 100% | 100% | 13.3% | 45.8% |

| qR or rSR in V1 | 13 | 59.1% | 100% | 100% | 18% | 62.5% |

| R wave in V1 or V2 | 20 | 86.4% | 50% | 95% | 25% | 83.3% |

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and diagnostic accuracy are provided for each criterion analyzed.

LBBC-Plus: Left bundle branch capture Plus; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value.

All the patients met the prerequisites for screw-in lead placement: lead in septal position (left oblique projection with fluoroscopy) and W paced morphology in V1. Mean threshold was 0.9 V ± 0.4 V (0.6 ms ± 0.2 ms).

Two patients that failed to show electrical resynchronization with LBBP in the ECGI did not fulfill the criteria of qR/rSR/LBBC-Plus. One of these patients, a crossover from failed biventricular CRT, had an R wave in V1 (but not qR or rSR) and notched QRS with two peaks in V6, 80 and 92 ms (Figure 4, case 1). The second patient did not present the qR/rSR/LBBC-Plus criteria and showed a spike-R in V6 of 102 ms; the operator left the electrode in this position for clinical reasons (Figure 4, case 2).

Figure 5.

Electrocardiographic imaging and ECG of a patient who did not fulfill the first criterion but achieved resynchronization. Baseline ECGI shows the delayed activation of the left ventricular wall. Final paced ECGI showed early activation in the left ventricle and a change in activation as compared to the baseline pattern. Left ventricular activation time shortening was -24 ms. Final paced QRS without qR/rSR/LBBC-Plus criteria but meeting the backup criterion (spike-R < 80) to accept lead position. Patient had non-isquemic cardiomyopathy, related to chemotherapy; QRS shortened 42 ms (182 to 140 ms), and at 12 months LVEF improved from severe dysfunction (24%) to moderate (35%). Severe hypokinesia in the lateral area. Laterolateral projection is shown. The anterior descending artery separates right ventricle from left ventricle. LBBP: left bundle branch pacing. LBBC-Plus: Left bundle branch capture Plus.

Only one patient had LBBP electrical resynchronization at the ECGI and did not present qR/rSR/LBBC-Plus criteria (Figure 5). In that patient, the V6 spike-R was 78 ms.

Discussion

Criteria to ensure LBBP have been published, but the proposed algorithms are complex and difficult to apply.16–18 Each center applies published criteria but homogeneity is lacking in the number and order of application of the criteria. We analyzed four of the published electrophysiological criteria: qR or rSR in V1; presence of selective capture; spike-R ≤85 ms in non-selective capture; and R in V1 or V2. Previous work16,20,26 assessed LBB capture. Our study used the concept of electrical resynchronization, demonstrated by shortening of the LV activation time and correction of the electrical delay at the lateral wall with LBBP.

A stepwise approach is proposed to ensure electrical resynchronization with LBBP (Graphical abstract). Both prerequisites for screw-in lead placement should be met: lead in septal position in left oblique projection and W paced morphology in V1. After screwing the lead, a QRS with right bundle branch delay pattern (qR or rSR) or LBBC-Plus must be obtained. If the qR/rSR/LBBC-Plus criteria is not fulfilled, the position could be satisfactory if selective capture is present or if the spike-R (non-selective capture) is <80 ms.

LBBC-Plus was described as a narrow QRS (≤120 ms) obtained with monopolar pacing, without fusion with intrinsic conduction; it shows a pattern characterized by a Q wave in V1 without right bundle branch delay morphology and suggests simultaneous capture of right and left bundle.25 The physiologic basis for this phenomenon is incompletely understood. Potential mechanisms include (Figure 2): (i) simultaneous capture of right and left bundle with the lead screw25; (ii) presence and capture of a septal fascicle; (iii) retrograde conduction from the left bundle to the right bundle branch20; and (iv) transseptal activation and nonselective recruitment of the RV.20 In a recent study, Q wave in V1 with narrow QRS was observed in 7.6% of patients,11 compared to 33% in our series (8/24 patients). R wave disappearance in lead V1 without significant QRS widening has been reported in 56.1% of the patients in whom high voltage bipolar left bundle branch area pacing was delivered30 During bipolar pacing, the phenomenon could be explained by capture of part of the right septal myocardium by anodal capture.7,31 LBBC-Plus has been described during unipolar pacing.25 The qR/rSR/LBBC-Plus criteria was the best approach in our study to obtain electrical resynchronization with LBBP.

Using a multielectrode catheter at the LV septum as a gold standard, Wu S. et al.16 defined the sensitivity and specificity of the more commonly used criteria. They found a specificity of 100% for the selective capture, in line with our findings, and a very high specificity for spike-peak R wave in V6: 93–95%, depending on the presence of LBBB (spike-R in V6 85 ms) or non-LBBB (spike-R in V6 75 ms). Jastrzebski M. et al., found that the optimal spike-R in V6 were 83 ms and 101 ms for patients with normal and diseased LBB, respectively; and ≤80 ms had specificity of 100% for LBB capture diagnosis in diseased LBB.32 Sun W. et al.20 showed that spike-R in V5–V6 was significantly shorter for non-selective capture compared to selective LBBP. Paced right bundle branch block morphology criterion has been previously studied using a LV septum catheter16 with 100% sensitivity; however, the accuracy of the new composite criterion including LBBC-Plus had not been reported to date.

In summary, the proposed approach could help in LBBP lead implantation by providing a stepwise, simple approach to ensure electrical resynchronization with LBBP.

Limitations

The main limitation is the small number of patients and the very small number of patients without electrical resynchronization with LBBP. Larger studies evaluating real-time activation non-invasively with ECGI during implantation and in different positions (not only the final placement) are needed to validate the algorithm proposed here. It would be valuable to demonstrate the utility of this approach in a prospective population including primarily LBBB patients with cardiomyopathy.

The criteria derived from our substudy data have been tested in patients with dilated heart and ventricular dysfunction. The validity of the criteria in structurally normal hearts remains to be determined. The V6–V1 interpeak interval criterion33 (>33 ms, sensitivity of 71.8%, specificity of 90.0%) has not been considered in the LEVEL-AT trial nor in the present study; prospective consideration of this criterion could provide additional insight, due to the described capacity to distinguish LBB capture from pure left ventricular septal myocardial capture. R wave peak time in lead aVL < 79 ms is another promising criterion to be studied, especially when a drop in R wave amplitude in the V6 lead occurs.34

Finally, a multielectrode mapping catheter in the left septum would have been the best tool to record retrograde and/or anterograde potentials as direct evidence to confirm LBB capture.16 The approach used to assess LBBP electrical resynchronization with ECGI has not been validated with endocardial LV activation maps. As LBBP could only be confirmed with left septal mapping, the study analyzed the achievement of electrical resynchronization with the LBBP lead, defined as shortening of the LV activation time and change in the activation pattern. Results described in our study refer to electrical resynchronization with LBBP assessed with ECGI and not to LBB capture. However, ECGI data allowed non-invasive assessment of electrical resynchronization with LBBP and avoided the added risks to the patient associated with use of a retro-aortic catheter during device implantation.

Conclusions

A stepwise approach is proposed to deploy the septal lead, ensuring electrical resynchronization with LBBP. The main criterion is QRS with right bundle branch delay pattern (qR or rSR) in V1 or LBBC-Plus capture (QRS ≤120 ms), after guaranteeing that the prerequisites for screwing are met: septal position of the lead in left oblique projection and W paced morphology in V1. If the main criterion is not met, the lead position would be acceptable if selective capture or spike-R <80 in non-selective capture were achieved.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Neus Portella, Carolina Sanroman, and Eulàlia Ventura for administrative support; Arrhythmia nursing team for their work in the Device Clinic; David Sanz and Jose Alcolea for their support at the Cardiac Imaging Section; Yolanda Rivodigo for her logistic support; Dr Susanna Prat, Dr Marcelo Sanchez, and the computed tomography scan technicians for their help in image processing; Josep Boqué for his support with electrocardiographic imaging. Finally, the authors thank the LEVEL-AT patients who have made this work possible.

Contributor Information

Margarida Pujol-López, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

Elisenda Ferró, Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

Roger Borràs, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

Paz Garre, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain.

Eduard Guasch, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

Rafael Jiménez-Arjona, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain.

Cora Garcia-Ribas, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain.

Adelina Doltra, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

Mireia Niebla, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

Esther Carro, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain.

Ivo Roca-Luque, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

J Baptiste Guichard, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

J Luis Puente, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain.

Laura Uribe, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain.

Sara Vázquez-Calvo, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

M Ángeles Castel, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

Elena Arbelo, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

Andreu Porta-Sánchez, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain.

Marta Sitges, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

José M Tolosana, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

Lluís Mont, Institut Clínic Cardiovascular (ICCV), Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, C/Villarroel 170, 08036 Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Funding

M.P.L. has received the Catalan Society of Cardiology Research Grant in 2019 and 2020 (Catalonia, Spain); the Josep Font Research Grant (2019–2022) from Hospital Clínic Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain); the Research Grant 2020 from Asociación del Ritmo Cardiaco from the Spanish Society of Cardiology (Spain); and the Post-Residence Mobility Grant 2021 from the Spanish Society of Cardiology (Spain). J.M.T., M.A.C., M.P.L., and R.J.A. have received funding for Project in Conduction System Pacing (FIS PI21/00615) from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid, Spain).

Data availability

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

References

- 1. Kircanski B, Boveda S, Prinzen F, Sorgente A, Anic A, Conte Get al. Conduction system pacing in everyday clinical practice: EHRA physician survey. Europace 2023;25:682–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang W, Su L, Wu S, Xu L, Xiao F, Zhou Xet al. A novel pacing strategy with low and stable output: pacing the left bundle branch immediately beyond the conduction block. Can J Cardiol 2017;33:1736.e1–.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Padala SK, Ellenbogen KA. Left bundle branch pacing is the best approach to physiological pacing. Heart Rhythm O2 2020;1:59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang Y, Zhu H, Hou X, Wang Z, Zou F, Qian Zet al. Randomized trial of left bundle branch vs biventricular pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80:1205–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu S, Su L, Vijayaraman P, Zheng R, Cai M, Xu Let al. Left bundle branch pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy: nonrandomized on-treatment comparison with His bundle pacing and biventricular pacing. Can J Cardiol 2021;37:319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vijayaraman P, Ponnusamy S, Cano Ó, Sharma PS, Naperkowski A, Subsposh FAet al. Left bundle branch area pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2021;7:135–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang S, Zhou X, Gold MR. Left bundle branch pacing. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:3039–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huang W, Wu S, Vijayaraman P, Su L, Chen X, Cai Bet al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy using left bundle branch pacing. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2020;6:849–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ponnusamy SS, Arora V, Namboodiri N, Kumar V, Kapoor A, Vijayaraman P. Left bundle branch pacing: a comprehensive review. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020;31:2462–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scheetz SD, Upadhyay GA. Physiologic pacing targeting the his bundle and left bundle branch: a review of the literature. Curr Cardiol Rep 2022;24:959–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jastrzębski M, Kiełbasa G, Cano O, Curila K, Heckman L, de Pooter Jet al. Left bundle branch area pacing outcomes: the multicentre European MELOS study. Eur Heart J 2022;43:4161–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vijayaraman P, Chung MK, Dandamudi G, Upadhyay GA, Krishnan K, Crossley Get al. His bundle pacing. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:927–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, Michowitz Y, Auricchio A, Barbash IMet al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace 2022;24:71–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pujol-López M, Jiménez-Arjona R, Garre P, Guasch E, Borràs R, Doltra Aet al. Conduction system pacing vs biventricular pacing in heart failure and wide QRS patients. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2022;8:1431–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ali N, Arnold AD, Miyazawa AA, Keene D, Chow JJ, Little Iet al. Comparison of methods for delivering cardiac resynchronization therapy: an acute electrical and haemodynamic within-patient comparison of left bundle branch area, his bundle, and biventricular pacing. Europace 2023;25:1060–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu S, Chen X, Wang S, Xu L, Xiao F, Huang Zet al. Evaluation of the criteria to distinguish left bundle branch pacing from left ventricular septal pacing. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2021;7:1166–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang W, Chen X, Su L, Wu S, Xia X, Vijayaraman P. A beginner’s guide to permanent left bundle branch pacing. Heart Rhythm 2019;16:1791–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen X, Qian Z, Zou F, Wang Y, Zhang X, Qiu Yet al. Differentiating left bundle branch pacing and left ventricular septal pacing: an algorithm based on intracardiac electrophysiology. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2022;33:448–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen K, Li Y. How to implant left bundle branch pacing lead in routine clinical practice. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2019;30:2569–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun W, Upadhyay GA, Tung R. Influence of capture selectivity and left intrahisian block on QRS characteristics during left bundle branch pacing. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2022;8:635–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tamborero D, Mont L, Sitges M, Silva E, Berruezo A, Vidal Bet al. Optimization of the interventricular delay in cardiac resynchronization therapy using the QRS width. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:1407–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tamborero D, Vidal B, Tolosana JM, Sitges M, Berruezo A, Silva Eet al. Electrocardiographic versus echocardiographic optimization of the interventricular pacing delay in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2011;22:1129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arbelo E, Tolosana JM, Trucco E, Penela D, Borràs R, Doltra Aet al. Fusion-optimized intervals (FOI): a new method to achieve the narrowest QRS for optimization of the AV and VV intervals in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2014;25:283–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen X, Wu S, Su L, Su Y, Huang W. The characteristics of the electrocardiogram and the intracardiac electrogram in left bundle branch pacing. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2019;30:1096–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pujol-López M, Tolosana JM, Mont L. The plus and pure left bundle branch pacing. Europace 2021;23:1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jastrzębski M, Moskal P, Bednarek A, Kiełbasa G, Kusiak A, Sondej Tet al. Programmed deep septal stimulation: a novel maneuver for the diagnosis of left bundle branch capture during permanent pacing. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020;31:485–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Keene D, Whinnett ZI. Advances in cardiac resynchronisation therapy: review of indications and delivery options. Heart 2022;108:889–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Elliott MK, Mehta V, Sidhu BS, Niederer S, Rinaldi CA. Electrocardiographic imaging of his bundle, left bundle branch, epicardial, and endocardial left ventricular pacing to achieve cardiac resynchronization therapy. HeartRhythm Case Rep 2020;6:460–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arnold AD, Shun-Shin MJ, Keene D, Howard JP, Chow J, Lim Eet al. Electrocardiographic predictors of successful resynchronization of left bundle branch block by His bundle pacing. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2021;32:428–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mirolo A, Chaumont C, Auquier N, Savoure A, Godin B, Vandevelde Fet al. Left bundle branch area pacing in patients with baseline narrow, left, or right bundle branch block QRS patterns: insights into electrocardiographic and echocardiographic features. Europace 2023;25:526–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vijayaraman P, Huang W. Atrioventricular block at the distal his bundle: electrophysiological insights from left bundle branch pacing. HeartRhythm Case Rep 2019;5:233–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jastrzębski M, Kiełbasa G, Curila K, Moskal P, Bednarek A, Rajzer Met al. Physiology-based electrocardiographic criteria for left bundle branch capture. Heart Rhythm 2021;18:935–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jastrzębski M, Burri H, Kiełbasa G, Curila K, Moskal P, Bednarek Aet al. The V6-V1 interpeak interval: a novel criterion for the diagnosis of left bundle branch capture. Europace 2022;24:40–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Briongos-Figuero S, Estévez-Paniagua Á, Sánchez-Hernández A, Muñoz-Aguilera R. Combination of current and new electrocardiographic-based criteria: a novel score for the discrimination of left bundle branch capture. Europace 2023;25:1051–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.