Abstract

Cardiometabolic disease comprises cardiovascular and metabolic dysfunction, and underlies the leading causes of morbidity and mortality, both within the United States and worldwide. Commensal microbiota are implicated in the development of cardiometabolic disease. Evidence suggests that the microbiome is relatively variable during infancy and early childhood, becoming more fixed in later childhood and adulthood. Effects of microbiota, both during early development, and in later life, may induce changes in host metabolism that modulate risk mechanisms and predispose towards development of cardiometabolic disease. In this review, we summarize factors that influence gut microbiome composition and function during early life, and explore how changes in microbiota and microbial metabolism influence host metabolism and cardiometabolic risk throughout life. We highlight limitations in current methodology and approaches, and outline state of the art advances which are improving research, and building towards refined diagnosis and treatment options in microbiome-targeted therapies.

Keywords: Cardiovascular Disease, Metabolism

Introduction

Gut microbiota have been associated with a wide variety of diseases1, with cardiometabolic diseases and their risk factors being repeatedly identified as having a microbial component. Exposure to commensal microbes and their products begins at or before birth, and microbial metabolism may modulate pathways that can initiate early metabolic reprograming that can be pathogenic or protective, depending on specific circumstances. While microbiota across various body sites have potential relevance to disease, the gut microbiome represent the most abundant and the most well-studied, and serves as the focus for this review. Within the following sections, we summarize the known determinants of gut microbiome composition (Figure 1), examine potential mechanisms linking microbial metabolism to disease (Figure 2), highlight known microbiome-disease relationships, and discuss developments in the field that may ultimately lead towards clinical utility.

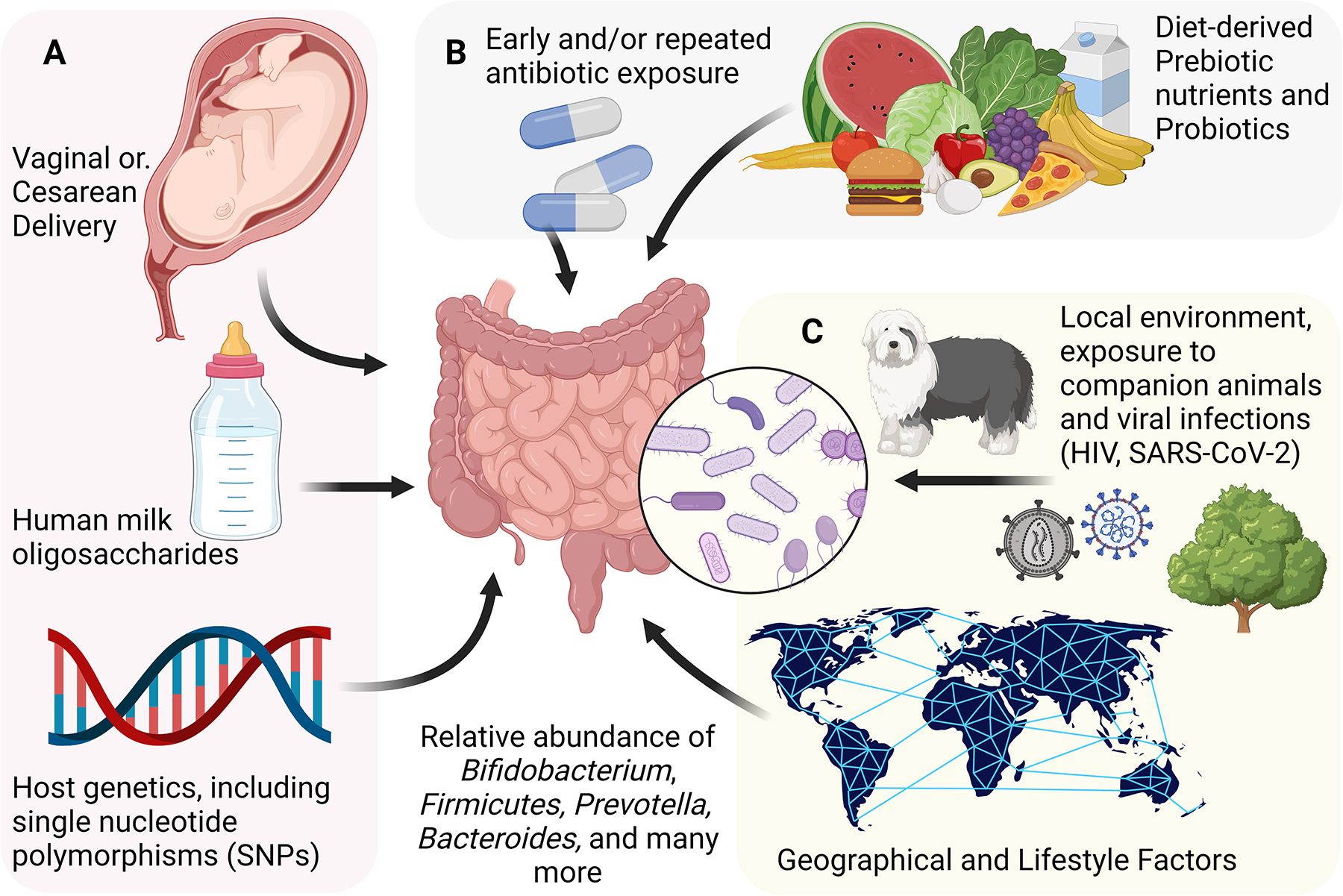

Figure 1. Determinants of Gut Microbiome Composition.

Many factors influence the composition of the gut microbiota. Some of these are determined very early in life, and are not modifiable later in life, including individual genetic background, delivery method, and early infant feeding method (A). Other determinants are variable throughout life, and potentially modifiable, including diet and use of medications (B). Other factors are similarly variable throughout life, but potentially more difficult to modify, including persistent viral infection, the local environment and broader geographical environment (C).

HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

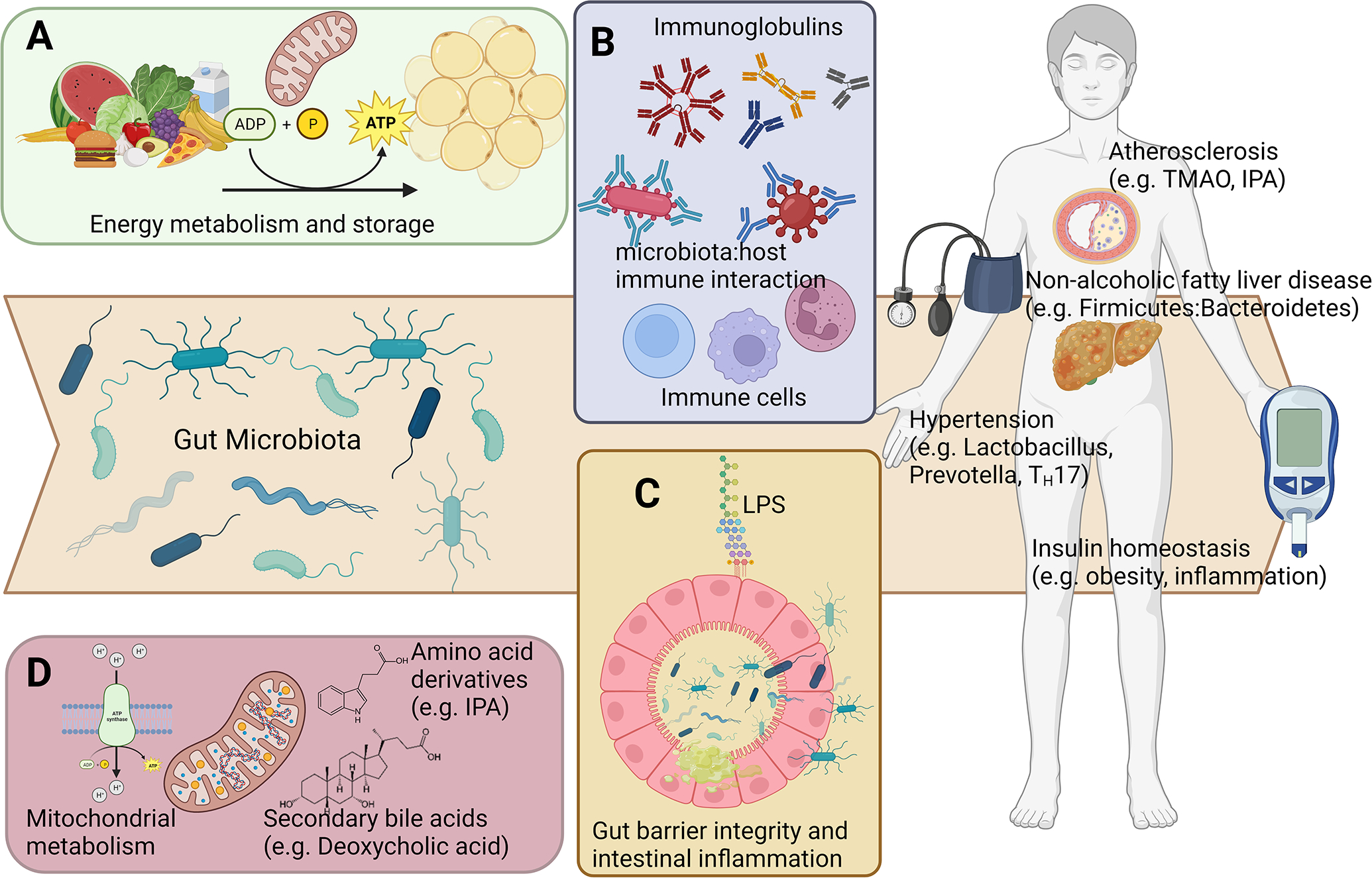

Figure 2. Mechanisms linking microbial metabolism to host physiology.

Gut microbiota may cause cardiometabolic disease through diverse mechanisms including A) modulation of energy and nutrient availability; B) activation of immune responses; C) modulation of gut barrier integrity; and D) systemic effects via microbe-mediated signaling molecules. TMAO: Trimethylamine N-oxide; IPA: Indole-3-propionic acid. TH17: T helper 17 cells.

Gut microbiome composition is highly variable during infancy and childhood.

Early life represents a highly variable period for microbial colonization. While some evidence has suggested that microbiota may be transferred to the developing fetus prior to delivery2–4, the majority of current evidence points towards birth as the major event triggering large-scale microbial colonization5–7. Colonization of the infant gut occurs opportunistically, with initial contributions from vaginal, fecal, and skin microbiota, depending on delivery method, in addition to contributions from species present in the local environment8–13. Of these early strains, only a small subset are later found to successfully colonize14, and it has not yet been firmly established whether the initial source of microbiota during delivery has a significant effect on any long-term outcomes15–17. Engraftment of specific microbes occurs during the months following birth, and is influenced by source of nutrition18,19. Infants who are fed human milk have been reported to have higher proportions of Bifidobacterium, Actinobacteria and Firmicutes compared to higher levels of Atopobium, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroides in infants fed with formula18,19. However, human milk feeding has also been associated with higher relative abundances of Bacteroides compared with formular feeding, in addition to lower proportions of Clostridium, Lachnospiraceae, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and Veillonella20. These data highlight the challenges that remain in characterizing specific taxa that associate with environmental exposures, and suggest the need for more functional characterization. Human milk contains microbiota21–23, and additionally contains prebiotics, oligosaccharides, and antibodies, which can preferentially support growth of specific microbiota, including Bifidobacterium, and protect against pathogens24–30. Further, there is some evidence of reciprocal interaction of oral microbiota and other signaling molecules which may occur during breastfeeding31–35. However the composition of human milk is highly variable36–39, suggesting that effects of human milk feeding on infant microbiome composition and any long-term outcomes may not be uniform. Microbiome composition becomes more stable after age 3, resembling the composition seen in adults14, with predominant representation by Firmicutes phylum, and Prevotella and Bacteroides genera14,40. Overall, this pattern of high variability suggests that infancy and early childhood is a critical period where sub-optimal colonization may determine later predisposition towards dysbiosis. There is some evidence linking early life microbiota to later inflammatory and immune-mediated disease, and to childhood obesity41. However, longitudinal studies are required to establish whether microbiome composition in childhood and early adulthood impacts long-term adult cardiometabolic health.

Bi-directional relationships between diet-derived nutrients and microbiota.

One of the most well-studied determinants of human microbiome composition is diet. Significant differences have been observed in gut microbiota from individuals consuming different diets based on geographical or traditional distinctions, such as hunter-gatherer, pastoralist, agriculture or urban14,42–50. However, even within local populations, microbiota differ between individuals based on dietary choices, such as vegetarian or vegan51–55, low-carbohydrate “paleo”56–58, low fat59, or gluten free60,61. Non-digestible carbohydrates, including starches and fiber, are abundant in certain plant-based foods, and serve as a substrate for fermentation by colonic microbiota, leading to their designation as prebiotics. Prebiotics are generally defined as substances which are metabolized by commensal microbes and promote health62, which contrasts with probiotics, defined as the beneficial microbes themselves63. Presence or absence of prebiotic nutrients provides a selective pressure which may favor specific microbes64–67. Further, metabolism of these nutrients produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which serve as a primary fuel source for colonic epithelial cells, and act as important signaling molecules68, as discussed further in a later section. In the setting of sub-optimal diet, supplementation with pre- or probiotics may be an effective means of promoting microbial diversity. Supplementation with the prebiotic fiber inulin has been shown to lead to increases in Bifidobacterium, Anaerostipes, Faecalibacterium and Lactobacilus, with reduction in Bacteroides69. However, whether this leads to changes in SCFAs is unclear69. Further, given the complexity and inter-individual variability in microbiomes, there may be risks associated with probiotic and prebiotic supplementation, which remain to be fully explored70. Other dietary components with potentially large effects on microbiota include non-nutritive sweeteners71,72, and probiotic-containing fermented foods73–78.

In addition to host dietary intake influencing microbial abundance, the presence and action of specific microbes also modulates nutrient availability to the host79. This is one mechanism whereby microbiota can influence host health status, and may be of particular relevance to obesity. Many studies have identified differences in microbiome composition based on body weight or adiposity, starting in childhood80–82, and fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) studies in animals and humans suggest that microbiota by themselves can promote obesity83–85. Because microbiota both consume and produce energy and nutrients within the intestines, there can be considerable variability in energy and nutrient availability to individuals consuming the same diet79,84,86,87. However, identifying effective strategies to reduce obesity through modulation of the gut microbiota have proven challenging88,89, and considerable additional research is required to understand the complex host:microbe relationships modulating energy and nutrient metabolism.

Environmental determinants of microbiome composition and drug:microbe interactions.

Local environment plays an important role in determining microbiome composition, particularly during childhood, but also throughout the lifespan. Differences have been reported in microbiota within individuals in rural or urban environments90–92. Within the home, exposure to older siblings93, and to pets has been associated with increased bacterial diversity in children94,95. Use of antibiotics has a significant impact on commensal microbes, particularly in the case of broad-spectrum oral antibiotics, generally leading to a reduction in diversity and reduction in microbes through to be beneficial96. The gut microbiota generally recover following a course of antibiotics, however it can take several weeks, and may never completely restore to pre-antibiotic diversity97. Repeated courses of antibiotics, particularly in children, may have more long-standing effects98, including increased risk of antibiotic resistance99, in addition to obesity and cardiometabolic disease100–107. This is likely mediated by antibiotic-induced alterations in microbiota which alter the function of the microbiome, and may lead to altered production of metabolites, and persistent downstream host metabolic dysregulation98,107–109. Other medications also interact bidirectionally with the microbiome, and may alter microbiota, in addition to being differentially metabolized based on presence or absence of specific microbes110–114. These include commonly used anti-hypertensive and cardiometabolic drugs, including angiotensin II receptor blockers115,116, statins117, proton-pump inhibitors118, and anti-diabetic medication119, both individually and in combination120, as well as neuropsychiatric121 and gastrointestinal medications122. Microbiota may also alter vaccine responses in children and adults123–126.

Genetic determinants of microbiome composition.

Several studies have investigated the impact of host genetic variation on gut microbial composition, primarily through genome-wide association studies (GWAS). These have identified close to 1,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that associate with specific bacterial taxa127–136. However, given the inherent heterogeneity in metagenomic profiling between studies, and presence of confounding, robust replication and validation of suggested GWAS associations remains a challenge137. Several microbe-associated SNPs also associate with disease phenotypes, suggesting that one mechanisms linking human genetic variation with disease may be through modulation of commensal microbes138–141. Suggested associations include Ruminococcus flavefaciens and hypertension, Clostridium and platelet count142, and Lachnospiraceae and several autoimmune diseases138, however these associations require more validation, and remain to be proven experimentally. While human genetic variation may contribute to inter-individuality in gut microbiota, this may be relatively minor compared with other determinants of microbial composition143.

Mechanisms linking gut microbiota to development of cardiometabolic disease.

Gut microbiome composition has been found to associate with numerous complex diseases, including cardiometabolic disease144. However, the potential pathways linking gut microbiota to cardiometabolic health are not fully understood. There are likely several distinct mechanisms whereby commensal microbes can influence disease pathogenesis, including through 1) modulation of nutrient and energy availability, as described above; 2) activation of immune responses; 3) modulation of gut barrier integrity; and 4) systemic effects via microbe-mediated signaling molecules.

Commensal microbiota and innate immune function:

The interaction between microbes and the host immune system is complex. In a healthy gut, multiple factors allow the intestinal immune system and commensal microbes to coexist in a mutually tolerant state145. Dysregulation of this balance, leading to uncontrolled immune activation, may partly underlie the chronic systemic low-grade inflammation associated with cardiometabolic diseases146. Immune activation occurs through direct interaction between host cells and microbes, and through microbe-generated signaling molecules. Intestinal host:microbe homeostasis is thought to be promoted through a balance of effector and suppressor arms of the adaptive immune system; commensal microbes target multiple antigen-presenting cells, promoting expansion of anti-inflammatory T regulatory cells (Treg), or pro-inflammatory T helper 17 (TH17) depending on the setting147–149. This is mediated through multiple mechanisms. Specific species, including segmented filamentous bacteria, activate TH17 cells, which increases intestinal inflammation, and protects against intestinal pathogens150. However other species, including Lactobacillus murinus, have been suggested to inhibit pathogenic TH17 cell activation, but are depleted in the setting of a high-salt diet151. While TH17 activation in some settings may improve host immune responses and healing152,153, there may also negative consequences on host immune function from pathogenic TH17 activation, including hypertension, inflammatory and autoimmune disease154,155. Clostridium species have been found to induce Treg cells156,157. The SCFA butyrate induces tolerogenic dendritic cells and promotes Treg cells158–161. Other microbe-derived molecules may similarly affect T cell activity, including bile acids162,163. Innate immune system and T cell development during early life may have particular importance in establishing antigen tolerance164–166, further highlighting the importance of early microbial colonization in infancy and childhood on lifelong health167. Changes in immune function occurring at subsequent life stages including pregnancy168, may also disrupt the balance between microbes and the innate immune system. In addition, dietary factors, including intake of sodium, can affect host:microbe homeostasis, leading to activation of TH17 cells, promoting formation of pro-inflammatory isolevuglandins and increased risk of hypertension169,170.

Host:microbe interaction in gut barrier integrity:

In a healthy intestine, colonic goblet cells produce a thick mucus barrier which provides some separation between host cells and microbes171. The mechanisms determining mucus secretion remain incompletely defined, but are in part regulated by activation of autophagy and consequent reduction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, in a microbiota-dependent manner172. The presence of butyrate-producing bacteria promotes mucus production by goblet cells173. However, in the absence of sufficient SCFA availability, potentially due to low-fiber diet or dysbiosis, there is reduction in the mucosal barrier, linked both to reduced mucus production173 and digestion of the mucosal barrier by commensal microbes174. While a certain amount of mucus digestion by microbes is expected and may even be beneficial to the microbial ecosystem and epithelial health175, excessive degradation can promote inflammation within the intestinal wall, in addition to reduction in epithelial tight junctions, leading to a “leaky” gut barrier and increased risk of pathogenic infection and translocation of intestinal products176–178. The presence of bacteria or bacterial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) entering through the portal vein then activates systemic immune responses, leading to a pro-inflammatory state with altered LPS-responsiveness, and increased risk of cardiometabolic disease, heart failure, and adverse outcomes179–182.

Microbial Metabolism:

Commensal microbes produce a large variety of metabolites, some of which have already been demonstrated to be of relevance to human health. However, our understanding of the specific pathophysiological relevance of the full spectrum of microbial-metabolites is still in its infancy. Several microbe-derived metabolites have been identified as being of particular importance to cardiometabolic health and disease149,183,184. Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) is a metabolite produced collaboratively by the host and microbiota, where microbes generate trimethylamine (TMA) from dietary precursors (including choline, phosphatidylcholine, carnitine and betaine)185, and the host then converts TMA into TMAO, which has been shown to increase atherosclerosis186–188 and other cardiovascular diseases183. The production of TMA is dependent on the presence of microbial genes, collectively known as the gbu gene cluster, which catalyze intermediate steps, such as the conversion of carnitine to TMA via γ-butyrobetaine189,190. Another microbe-dependent metabolite, phenylacetylglutamine (PAG), which is derived from phenylalanine, has also been shown to associate with cardiovascular disease191,192. Production of this metabolite is dependent on the presence of microbial genes encoding enzymes in the phenylpyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PPFOR) and phenylpyruvate decarboxylase (PPDC) pathways191. PAG has been shown to modulate adrenergic receptor signaling, and is linked to increased risk of thrombosis and heart failure192,193. Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) is a microbe-derived metabolite of tryptophan, which acts as an antibiotic, and has been suggested to be protective in disease, exhibiting anti-inflammatory and antioxidant function194,195, and modulation of cholesterol efflux196. Higher IPA has been associated with higher gut microbiome diversity197. Other tryptophan metabolites, including kynurenine, are also modulated by microbiota198 and may associate with cardiometabolic disease199,200 as well as with neuropsychiatric disease201, highlighting potential mechanistic underpinnings of the known comorbidity of cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric disease202. The production and abundance of IPA and other indole-derived tryptophan metabolites is dependent on the presence of specific microbial genes203. Host-derived bile acids are important for nutrient metabolism within the digestive tract, but also alter microbial composition and function204. Bile acids are modified by microbiota into secondary bile acids205, which can act as systemic signaling molecules modulating inflammation and metabolism206,207. The production of secondary bile acids, and potential downstream pathogenicity, are dependent on the presence of microbial species possessing bile salt hydrolase activity208,209. Several microbe-derived metabolites act as uremic toxins, including TMAO and IPA, in addition to other protein-derived metabolites210,211. Communication between the host and microbial metabolism can occur at any point throughout the lifetime, but may be particularly important during early life. As mentioned earlier, the evidence supporting pre-natal microbial colonization is limited. However, maternal microbes may affect fetal development through metabolic signaling that crosses the placenta212. SCFAs were shown to act on embryonic receptors (GPR41 and GPR43), altering cell differentiation and development across multiple tissues, with long-lasting effects on metabolism212. Other microbial metabolites, including amino acid-derived metabolites may also cross the placenta, with potential effects on fetal development213,214. Further, there is growing evidence for a wide variety of other metabolites, produced through the action of microbiota on dietary nutrients, that may affect host health, including amino acids215, soy-derived isoflavones216–219, cannabinoids220, and phenolic acids221, in addition to a large number of pharmacological and host metabolites that may be modulated by microbiota110,222–225.

Association between microbial metabolism and early development of cardiometabolic disease.

Effects of microbiota on gut barrier integrity and inflammation, both local and systemic, have the potential to alter cardiometabolic disease risk broadly, through modulation of body weight and energy metabolism, insulin and glucose homeostasis, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and vascular function. As described below, microbiota have been linked to multiple risk mechanisms underlying cardiometabolic disease226, many of which likely precede overt CVD or diabetes. However, the relative importance of each mechanism remains to be further understood, and there may be considerable heterogeneity in effects, potentially linked to host genetic background or other factors.

The effects of gut microbiota on body weight regulation, inflammation, and insulin homeostasis:

Obesity and inflammation are recognized as important contributors to the development of subsequent cardiometabolic diseases, and may be one of the earliest symptoms of metabolic dysregulation227. Cross-sectional studies have identified differences in gut microbiota between lean and obese individuals across the lifespan80,81,83,228,229, and in the setting of diabetes230–232. Further, FMT experiments suggest causality, with microbiota from obese individuals promoting obesity in recipients84,85,233. Fecal transplants have also been shown to modulate insulin sensitivity in humans, however whether these effects persist over the long-term is unknown234,235. As discussed, the mechanisms are incompletely understood, but may relate in part to the effects of microbiota on energy harvesting capacity79,86,87,236. Further, effects of microbiota on inflammation may, by itself, be sufficient to promote metabolic dysregulation and obesity146,227,237. In particular, interaction between microbes and the gut immune system during critical periods of development, including early life, may have long-lasting effects on immune programming165–167,238–240.

Relationship between gut microbiota and hypertension:

Gut microbiota have been reported to modulate blood pressure through several potential mechanisms. Blood pressure elevation in response to dietary sodium has a contribution by gut microbiota, including Lactobacillus species, through modulation of TH17 cells and production of isolevuglandins151,169,170,241.Multiple bacterial species have been associated with hypertension, including Lactobacillus, Klebsiella, Parabacteroides, Desulfovibrio, and Prevotella241,242, although more validation and functional work is needed to delineate causal associations. Specific microbiota, including Romboutsia, Turicibacter, Ileibacterium, and Dubosiella, have affinity to prompt host immunoglobulin A (IgA) binding, which may promote the development of hypertension, potentially through the gut-brain axis243–245. Many of the aforementioned diet-derived and microbe-mediated metabolites, including TMAO and SCFAs, also play a role in modulating blood pressure246. For example, microbe-derived SCFAs bind to olfactory and G protein-coupled receptors (Olfr78 and Gpr41) in the kidney and vascular endothelium to modulate vasodilation, heart rate and blood pressure247–249.

Effects of gut microbiota on lipid metabolism:

Observational studies have identified potential relationships between gut microbiota and circulating lipids and lipoproteins250–254, with microbiota accounting for an estimated 4–6% of the variation in TG and HDL cholesterol255, and individual microbiota associating with specific lipoprotein subclasses in obese individuals256. Gut microbiota may affect lipid metabolism directly through modulation of lipids within the gut and systemically257, with gut microbial production of SCFAs serving as the precursor for hepatic synthesis of longer-chain monounsaturated fatty acids and glycerophospholipids258. Microbiota have also been shown to mediate transformation of cholesterol259. Mendelian Randomization analysis has also been used to support a potential causal pathway between specific gut microbiota and dyslipidemia260. In contrast, a reverse relationship is not supported, and elevated plasma lipid levels may not significantly affect gut microbiota; however bile acids may mediate relationships between microbiota and lipids261.

Gut microbial signaling modulates the development of hepatic steatosis:

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) accounts for a growing share of chronic liver disease in children and young adults262. NAFLD has been linked with atherosclerosis and left ventricular dysfunction in children and adolescents263 and there is growing evidence that early-life NAFLD carries life-long cardiometabolic health implications. Maternal obesity is associated with the development of NAFLD in childhood and early adulthood, partly due to changes in the intestinal microbiota264–267. Offspring of obese mice had altered intestinal microbiota and a worsened NAFLD phenotype relative to offspring of lean mothers266. Mice that received fecal transplants from infants born of obese mothers had a higher intestinal Bacteroidetes-to-Firmicutes ratio and these intestinal microbiome changes were associated with higher hepatic expression of inflammatory genes and higher hepatic triglyceride accumulation268. Studies in later childhood showed that children with NAFLD had significantly different intestinal microbiota characterized by lower alpha diversity and higher Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio, as well as higher abundance of Bradyrhizobium, Peptoniphilus, Anaerococcus, Propionibacterium acnes, Dorea and Ruminococcus and lower abundance of Oscillospira, Gemmiger and Rikenellaceae269–271. Additionally, Oscillospira, Gemmiger, and Bacteroidetes abundance as well as F/B ratio interact with PNPLA3 polymorphisms to contribute to the severity of NAFLD in children and adolescents270. Similar pathogenic changes in microbiota are associated with obesity and high fat diet in later childhood272. Changes in intestinal microbiota contribute to NAFLD pathogenesis through a variety of mechanisms: increased intestinal permeability and translocation of proinflammatory bacterial products268, changes in bile acid metabolism273,274, endogenous alcohol production275 and altered microbial metabolism of lipids, carbohydrates and amino acids276–279.There are currently no FDA-approved treatments for pediatric NAFLD and dietary and lifestyle interventions remain the standard of care. Clinical trials targeting the microbiome in children and adolescents with NAFLD have had promising results. Children with NAFLD treated with probiotics (VSL#3) for 4 months had significant improvement in hepatic steatosis compared to placebo controls280. Similarly, children with NAFLD treated with a probiotic containing Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus spp. for 12 weeks had improvement in hepatic steatosis in addition to improvement in LDL and triglyceride levels and serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST)281.

Gut microbial effects on cardiovascular disease:

Several studies have reported associations between microbiota and atherosclerosis282,283. As mentioned previously, TMAO associates with atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events, through mechanisms linked to atherothrombotic effects on platelet hyperreactivity and vascular function284,285. Down-regulation of IPA has been found to associate with coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis196, as well as with peripheral artery disease286. However, in mice fed a Western Diet, supplementation with IPA did not ameliorate the development of cardiometabolic disease287. Beyond metabolites, microbial nucleic acids have been found within lipoproteins288, suggesting that bacteria or their products may be carried within the circulation. Further, analysis of atherosclerotic plaque has identified microbial DNA within plaque289, suggesting that translocation of microbiota or their products to the circulation, whether from intestinal or oral sources, may directly increase plaque formation. While intriguing, at present there is still limited evidence to suggest that live microbes themselves cause plaque formation directly290, and atherosclerosis occurs even in the absence of live microbes291,292. However, plaque formation or expansion may be mediated by microbe-derived small RNAs, which can be carried by LDL cholesterol, and activate macrophages, potentiating development of atherosclerosis293. Microbiota, as assessed through microbiome composition, have been implicated in multiple cardiovascular diseases, including pulmonary arterial hypertension294, abdominal aortic aneurysm295, heart failure296, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)297, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)298, and coronary artery disease299. However, most studies have included relatively small sample sizes, with little or no replication, leaving considerable uncertainty surrounding the clinical or mechanistic relevance of specific findings. While some of these associations are likely mediated by microbial metabolites, and effects on inflammation, lipid metabolism and vascular function, as previously discussed179,196,284, the specific pathways linking microbiota to individual CVDs remain to be established. There is also some evidence that presence or absence of microbiota can alter gene expression in kidney and other tissues300–302, which remains to be further characterized and explored. Much could be learned through increased efforts to characterize microbiome composition and function across disease development in robust metagenomic and metatranscriptomic studies with large sample sizes, including replication and validation of novel associations.

Interaction between the gut microbiome and viral infection in modulation of cardiometabolic risk.

There is evidence to suggest that the presence of viral pathogens may potentiate negative effects of gut microbiota on cardiometabolic disease. Persons with HIV (PWH) have a twofold greater risk of developing CVD relative to persons without HIV, independent of Framingham cardiovascular risk factors303. HIV infection is associated with increased intestinal permeability304,305 that permits translocation of pro-inflammatory bacterial products306 that may increase systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease risk. This may be due to lower production of microbiota-produced SCFA in PWH307 which are integral for maintaining intestinal barrier function308. Additionally, levels of the microbial metabolite TMAO increase with antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation and are associated with carotid plaque burden in PWH309,310.

Following the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, several studies have focused on the role of the gut microbiota in COVID-19 and post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS, or Long-COVID). The gut microbiota of COVID-19 patients has been reported to be altered when compared with uninfected individuals311, and microbiota have been found to associate with severity of infection and outcomes within COVID-19 patients312–314. Specific microbes were reported to associated with PACS, and with various symptoms, including respiratory and neuropsychiatric315. Whether SARS-CoV-2 interacts with the gut microbiota to modulate COVID-19-related CVD risk remains unknown316,317.

Best practices and state of the art methods for microbiome clinical translation.

Microbiome research has undergone rapid expansion over the past two decades, but many existing microbiome studies suffer from limitations which have impeded interpretability and clinical translation. Some of these inherent limitations are easier to address than others. Early issues in methods and study design, and in reporting of results, are now largely addressable through adherence to best practices such as the Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies’ (STORMS) guidelines318, including careful study design, consideration of confounders, standardized protocols, and well-selected controls319. While early studies mostly applied 16S rRNA sequencing to approximate taxa, the costs for whole metagenome sequencing are now broadly equivalent to 16S profiling, and offer considerable advantages including more precise taxonomical classification to the species level, and the possibility to infer functionality based on microbial genes320,321. However, it remains important to also use direct measurement of microbial gene expression through metatranscriptomics, and metabolite measurement to accurately assess microbiome function322. Sample sizes in many clinical studies are still relatively small, often including fewer than 100 individuals, which limits power and generalizability. However, this issue may be one of the easiest to address: sequencing costs continue to drop, removing some of the financial considerations that previously limited the size of studies. Further, stool is a highly accessible tissue, and several studies have demonstrated that previous barriers relating to sample collection, transportation, and cold storage, can be eliminated using convenient collection and preservation methods that allow for non-invasive sample collection and room temperature transportation and storage323. This also alleviates an additional limitation, which relates to the variability of samples obtained cross-sectionally. While there is relative stability in microbiome profiles over time, there are both stochastic and biological differences in gut microbiome samples obtained at different times. Inclusion of multiple samples over short and long-term follow-up can greatly improve the quality of a study. While overall barriers relating to recruitment and cost of clinical and epidemiological studies remain, future studies can and should endeavor to maximize sample sizes and obtain repeated samples where possible for longitudinal analysis. However, some limitations are more difficult to overcome. As with other types of studies, there remains over-representation from certain population groups and geographical regions. Greater efforts are needed to ensure diversity in sampling and representation, including children and adolescents. Given the complexity of the relationships between microbiota and disease, there can be considerable confounding due to measured and unmeasured factors that affect microbial composition, and can lead to artifacts. These can be challenging to identify, but can be addressed in part through the strategies already discussed to maximize rigor and power, and by inclusion of external validation cohorts. Because microbes engage in horizontal gene transfer, there is a fundamental limitation in how accurately we can align sequence reads and define species, particularly when comparing across different studies324. Further, determining the relative importance of individual microbial species within the context of the holobiont remains a complex challenge. The use of complex synthetic microbiomes may be one way to bridge reductionist and holistic approaches325,326, and to allow for better-defined FMT-based therapeutics. In addition to metagenomic sequencing, additional approaches including metatranscriptomics can shift focus from presence or absence of specific species or microbial genes, towards functional read-outs that may have more biological relevance. Large-scale metabolomic profiling of stool, or of microbial metabolites in circulation using NMR or Mass Spectrometry may also shed more light on microbiome function, but may require rapid processing and careful handling of samples327–329. While animal studies and basic mechanistic studies are very important, to further advance clinical translation, we will require a greater emphasis on studies that test microbiome-targeted interventions, including those using pre- and probiotics, FMT, and targeted therapeutics to alter microbiome composition or function330–332. Pharmacological manipulation of microbes, to “drug the bugs” is a promising avenue that may have advantages in providing host benefit, with fewer side effects than traditional pharmacological approaches284,333,334. Overall, the field would be strengthened by a greater focus on translational studies that combine observational findings with mechanistic interrogation, or clinical implementation.

In summary, the emerging wealth of literature on gut microbiota and microbial metabolism support clear roles for microbiota in early development of cardiometabolic disease. While much remains unknown, improvements in clinical trial design and increased focus on rigor and reproducibility in microbiome studies are likely to support significant advances in the field, leading towards improved clinical utility of microbiome-related biomarkers, and future therapeutic implementation of microbiome-targeted therapies.

Funding:

CLG is supported by K12HL143956. JFF is supported by R01 DK117144 and R01 HL142856 from the NIH, and support from the Layton Family Fund.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Jackson MA, Verdi S, Maxan M-E, Shin CM, Zierer J, Bowyer RCE, Martin T, Williams FMK, Menni C, Bell JT, et al. Gut microbiota associations with common diseases and prescription medications in a population-based cohort. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aagaard K, Ma J, Antony KM, Ganu R, Petrosino J, Versalovic J. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:237ra65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prince AL, Ma J, Kannan PS, Alvarez M, Gisslen T, Harris RA, Sweeney EL, Knox CL, Lambers DS, Jobe AH, et al. The placental membrane microbiome is altered among subjects with spontaneous preterm birth with and without chorioamnionitis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 2016;214:627.e1–627.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiménez E, Fernández L, Marín ML, Martín R, Odriozola JM, Nueno-Palop C, Narbad A, Olivares M, Xaus J, Rodríguez JM. Isolation of commensal bacteria from umbilical cord blood of healthy neonates born by cesarean section. Curr. Microbiol 2005;51:270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez-Muñoz ME, Arrieta M-C, Ramer-Tait AE, Walter J. A critical assessment of the “sterile womb” and “in utero colonization” hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome. Microbiome. 2017;5:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker JM, Chase DM, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Uterine Microbiota: Residents, Tourists, or Invaders? Front Immunol. 2018;9:208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehbinder EM, Lødrup Carlsen KC, Staff AC, Angell IL, Landrø L, Hilde K, Gaustad P, Rudi K. Is amniotic fluid of women with uncomplicated term pregnancies free of bacteria? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 2018; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferretti P, Pasolli E, Tett A, Asnicar F, Gorfer V, Fedi S, Armanini F, Truong DT, Manara S, Zolfo M, et al. Mother-to-Infant Microbial Transmission from Different Body Sites Shapes the Developing Infant Gut Microbiome. Cell Host & Microbe. 2018;24:133–145.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yassour M, Jason E, Hogstrom LJ, Arthur TD, Tripathi S, Siljander H, Selvenius J, Oikarinen S, Hyöty H, Virtanen SM, et al. Strain-Level Analysis of Mother-to-Child Bacterial Transmission during the First Few Months of Life. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24:146–154.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grönlund MM, Lehtonen OP, Eerola E, Kero P. Fecal microflora in healthy infants born by different methods of delivery: permanent changes in intestinal flora after cesarean delivery. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr 1999;28:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jakobsson HE, Abrahamsson TR, Jenmalm MC, Harris K, Quince C, Jernberg C, Björkstén B, Engstrand L, Andersson AF. Decreased gut microbiota diversity, delayed Bacteroidetes colonisation and reduced Th1 responses in infants delivered by Caesarean section. Gut. 2014;63:559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller NT, Mao G, Bennet WL, Hourigan SK, Dominguez-Bello MG, Appel LJ, Wang X. Does vaginal delivery mitigate or strengthen the intergenerational association of overweight and obesity? Findings from the Boston Birth Cohort. Int J Obes (Lond). 2017;41:497–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tun HM, Bridgman SL, Chari R, Field CJ, Guttman DS, Becker AB, Mandhane PJ, Turvey SE, Subbarao P, Sears MR, et al. Roles of Birth Mode and Infant Gut Microbiota in Intergenerational Transmission of Overweight and Obesity From Mother to Offspring. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:368–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486:222–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H -t, Zhou Y -b, Liu J -m. The impact of cesarean section on offspring overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:893–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smithers LG, Mol BW, Jamieson L, Lynch JW. Cesarean birth is not associated with early childhood body mass index. Pediatric Obesity. 2018;12:120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barros AJD, Santos LP, Wehrmeister F, Motta JVDS, Matijasevich A, Santos IS, Menezes AMB, Gonçalves H, Assunção MCF, Horta BL, et al. Caesarean section and adiposity at 6, 18 and 30 years of age: results from three Pelotas (Brazil) birth cohorts. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bezirtzoglou E, Tsiotsias A, Welling GW. Microbiota profile in feces of breast- and formula-fed newborns by using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Anaerobe. 2011;17:478–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan W, Huo G, Li X, Yang L, Duan C, Wang T, Chen J. Diversity of the intestinal microbiota in different patterns of feeding infants by Illumina high-throughput sequencing. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2013;29:2365–2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang M, Li M, Wu S, Lebrilla CB, Chapkin RS, Ivanov I, Donovan SM. Fecal microbiota composition of breast-fed infants is correlated with human milk oligosaccharides consumed. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:825–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gómez-Gallego C, Morales J, Monleón D, du Toit E, Kumar H, Linderborg K, Zhang Y, Yang B, Isolauri E, Salminen S, et al. Human Breast Milk NMR Metabolomic Profile across Specific Geographical Locations and Its Association with the Milk Microbiota. Nutrients. 2018;10:1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solís G, de Los Reyes-Gavilan CG, Fernández N, Margolles A, Gueimonde M. Establishment and development of lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria microbiota in breast-milk and the infant gut. Anaerobe. 2010;16:307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gueimonde M, Laitinen K, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Breast milk: a source of bifidobacteria for infant gut development and maturation? Neonatology. 2007;92:64–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Triantis V, Bode L, van Neerven RJJ. Immunological Effects of Human Milk Oligosaccharides. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore RE, Xu LL, Townsend SD. Prospecting Human Milk Oligosaccharides as a Defense Against Viral Infections. ACS Infect Dis. 2021;7:254–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore RE, Townsend SD, Gaddy JA. The Diverse Antimicrobial Activities of Human Milk Oligosaccharides against Group B Streptococcus. Chembiochem. 2022;23:e202100423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spicer SK, Gaddy JA, Townsend SD. Recent advances on human milk oligosaccharide antimicrobial activity. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2022;71:102202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogier EW, Frantz AL, Bruno MEC, Wedlund L, Cohen DA, Stromberg AJ, Kaetzel CS. Secretory antibodies in breast milk promote long-term intestinal homeostasis by regulating the gut microbiota and host gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:3074–3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charbonneau MR, O’Donnell D, Blanton LV, Totten SM, Davis JCC, Barratt MJ, Cheng J, Guruge J, Talcott M, Bain JR, et al. Sialylated Milk Oligosaccharides Promote Microbiota-Dependent Growth in Models of Infant Undernutrition. Cell. 2016;164:859–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakanaka M, Gotoh A, Yoshida K, Odamaki T, Koguchi H, Xiao J, Kitaoka M, Katayama T. Varied Pathways of Infant Gut-Associated Bifidobacterium to Assimilate Human Milk Oligosaccharides: Prevalence of the Gene Set and Its Correlation with Bifidobacteria-Rich Microbiota Formation. Nutrients. 2020;12:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azad MB, Vehling L, Chan D, Klopp A, Nickel NC, McGavock JM, Becker AB, Mandhane PJ, Turvey SE, Moraes TJ, et al. Infant Feeding and Weight Gain: Separating Breast Milk From Breastfeeding and Formula From Food. Pediatrics. 2018;142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardner AS, Rahman IA, Lai CT, Hepworth A, Trengove N, Hartmann PE, Geddes DT. Changes in Fatty Acid Composition of Human Milk in Response to Cold-Like Symptoms in the Lactating Mother and Infant. Nutrients. 2017;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breakey AA, Hinde K, Valeggia CR, Sinofsky A, Ellison PT. Illness in breastfeeding infants relates to concentration of lactoferrin and secretory Immunoglobulin A in mother’s milk. Evol Med Public Health. 2015;2015:21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Shehri SS, Knox CL, Liley HG, Cowley DM, Wright JR, Henman MG, Hewavitharana AK, Charles BG, Shaw PN, Sweeney EL, et al. Breastmilk-Saliva Interactions Boost Innate Immunity by Regulating the Oral Microbiome in Early Infancy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sweeney EL, Al-Shehri SS, Cowley DM, Liley HG, Bansal N, Charles BG, Shaw PN, Duley JA, Knox CL. The effect of breastmilk and saliva combinations on the in vitro growth of oral pathogenic and commensal microorganisms. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Twigger A-J, Küffer G, Geddes D, Filgueria L, Twigger A-J, Küffer GK, Geddes DT, Filgueria L. Expression of Granulisyn, Perforin and Granzymes in Human Milk over Lactation and in the Case of Maternal Infection. Nutrients. 2018;10:1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bzikowska-Jura A, Czerwonogrodzka-Senczyna A, Olędzka G, Szostak-Węgierek D, Weker H, Wesołowska A, Bzikowska-Jura A, Czerwonogrodzka-Senczyna A, Olędzka G, Szostak-Węgierek D, et al. Maternal Nutrition and Body Composition During Breastfeeding: Association with Human Milk Composition. Nutrients. 2018;10:1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panagos PG, Vishwanathan R, Penfield-Cyr A, Matthan NR, Shivappa N, Wirth MD, Hebert JR, Sen S. Breastmilk from obese mothers has pro-inflammatory properties and decreased neuroprotective factors. J Perinatol. 2016;36:284–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gay M, Koleva P, Slupsky C, Toit E, Eggesbo M, Johnson C, Wegienka G, Shimojo N, Campbell D, Prescott S, et al. Worldwide Variation in Human Milk Metabolome: Indicators of Breast Physiology and Maternal Lifestyle? Nutrients. 2018;10:1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rinninella E, Raoul P, Cintoni M, Franceschi F, Miggiano GAD, Gasbarrini A, Mele MC. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms. 2019;7:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarkar A, Yoo JY, Valeria Ozorio Dutra S, Morgan KH, Groer M. The Association between Early-Life Gut Microbiota and Long-Term Health and Diseases. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021;10:459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kisuse J, La-Ongkham O, Nakphaichit M, Therdtatha P, Momoda R, Tanaka M, Fukuda S, Popluechai S, Kespechara K, Sonomoto K, et al. Urban Diets Linked to Gut Microbiome and Metabolome Alterations in Children: A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study in Thailand. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruggles KV, Wang J, Volkova A, Contreras M, Noya-Alarcon O, Lander O, Caballero H, Dominguez-Bello MG. Changes in the Gut Microbiota of Urban Subjects during an Immersion in the Traditional Diet and Lifestyle of a Rainforest Village. mSphere. 2018;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rampelli S, Schnorr SL, Consolandi C, Turroni S, Severgnini M, Peano C, Brigidi P, Crittenden AN, Henry AG, Candela M. Metagenome Sequencing of the Hadza Hunter-Gatherer Gut Microbiota. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1682–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnorr SL, Candela M, Rampelli S, Centanni M, Consolandi C, Basaglia G, Turroni S, Biagi E, Peano C, Severgnini M, et al. Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers. Nature Communications. 2014;5:3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gomez A, Petrzelkova KJ, Burns MB, Yeoman CJ, Amato KR, Vlckova K, Modry D, Todd A, Jost Robinson CA, Remis MJ, et al. Gut Microbiome of Coexisting BaAka Pygmies and Bantu Reflects Gradients of Traditional Subsistence Patterns. Cell Rep. 2016;14:2142–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jha AR, Davenport ER, Gautam Y, Bhandari D, Tandukar S, Ng KM, Fragiadakis GK, Holmes S, Gautam GP, Leach J, et al. Gut microbiome transition across a lifestyle gradient in Himalaya. PLoS Biol. 2018;16:e2005396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hansen MEB, Rubel MA, Bailey AG, Ranciaro A, Thompson SR, Campbell MC, Beggs W, Dave JR, Mokone GG, Mpoloka SW, et al. Population structure of human gut bacteria in a diverse cohort from rural Tanzania and Botswana. Genome Biol. 2019;20:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Afolayan AO, Ayeni FA, Moissl-Eichinger C, Gorkiewicz G, Halwachs B, Högenauer C. Impact of a Nomadic Pastoral Lifestyle on the Gut Microbiome in the Fulani Living in Nigeria. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubel MA, Abbas A, Taylor LJ, Connell A, Tanes C, Bittinger K, Ndze VN, Fonsah JY, Ngwang E, Essiane A, et al. Lifestyle and the presence of helminths is associated with gut microbiome composition in Cameroonians. Genome Biol. 2020;21:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Keilbaugh SA, Bewtra M, Knights D, Walters WA, Knight R, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334:105–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu GD, Compher C, Chen EZ, Smith SA, Shah RD, Bittinger K, Chehoud C, Albenberg LG, Nessel L, Gilroy E, et al. Comparative metabolomics in vegans and omnivores reveal constraints on diet-dependent gut microbiota metabolite production. Gut. 2016;65:63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zimmer J, Lange B, Frick J-S, Sauer H, Zimmermann K, Schwiertz A, Rusch K, Klosterhalfen S, Enck P. A vegan or vegetarian diet substantially alters the human colonic faecal microbiota. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kabeerdoss J, Devi RS, Mary RR, Ramakrishna BS. Faecal microbiota composition in vegetarians: comparison with omnivores in a cohort of young women in southern India. Br. J. Nutr 2012;108:953–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim M-S, Hwang S-S, Park E-J, Bae J-W. Strict vegetarian diet improves the risk factors associated with metabolic diseases by modulating gut microbiota and reducing intestinal inflammation. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2013;5:765–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Świątecka D, Dominika Ś, Narbad A, Arjan N, Ridgway KP, Karyn RP, Kostyra H, Henryk K. The study on the impact of glycated pea proteins on human intestinal bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol 2011;145:267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barone M, Turroni S, Rampelli S, Soverini M, D’Amico F, Biagi E, Brigidi P, Troiani E, Candela M. Gut microbiome response to a modern Paleolithic diet in a Western lifestyle context. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0220619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Genoni A, Christophersen CT, Lo J, Coghlan M, Boyce MC, Bird AR, Lyons-Wall P, Devine A. Long-term Paleolithic diet is associated with lower resistant starch intake, different gut microbiota composition and increased serum TMAO concentrations. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59:1845–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fava F, Gitau R, Griffin BA, Gibson GR, Tuohy KM, Lovegrove JA. The type and quantity of dietary fat and carbohydrate alter faecal microbiome and short-chain fatty acid excretion in a metabolic syndrome “at-risk” population. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanz Y Effects of a gluten-free diet on gut microbiota and immune function in healthy adult humans. Gut Microbes. 2010;1:135–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dieterich W, Schuppan D, Schink M, Schwappacher R, Wirtz S, Agaimy A, Neurath MF, Zopf Y. Influence of low FODMAP and gluten-free diets on disease activity and intestinal microbiota in patients with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, Prescott SL, Reimer RA, Salminen SJ, Scott K, Stanton C, Swanson KS, Cani PD, et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, Gibson GR, Merenstein DJ, Pot B, Morelli L, Canani RB, Flint HJ, Salminen S, et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:506–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sonnenburg ED, Sonnenburg JL. Starving our microbial self: the deleterious consequences of a diet deficient in microbiota-accessible carbohydrates. Cell Metab. 2014;20:779–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, Burcelin R. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57:1470–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut. 2015;64:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cotillard A, Kennedy SP, Kong LC, Prifti E, Pons N, Le Chatelier E, Almeida M, Quinquis B, Levenez F, Galleron N, et al. Dietary intervention impact on gut microbial gene richness. Nature. 2013;500:585–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Feng Y, Wang Y, Wang P, Huang Y, Wang F. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Manifest Stimulative and Protective Effects on Intestinal Barrier Function Through the Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome and Autophagy. Cell. Physiol. Biochem 2018;49:190–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Le Bastard Q, Chapelet G, Javaudin F, Lepelletier D, Batard E, Montassier E. The effects of inulin on gut microbial composition: a systematic review of evidence from human studies. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39:403–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bafeta A, Koh M, Riveros C, Ravaud P. Harms Reporting in Randomized Controlled Trials of Interventions Aimed at Modifying Microbiota. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang Q-P, Browman D, Herzog H, Neely GG. Non-nutritive sweeteners possess a bacteriostatic effect and alter gut microbiota in mice. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0199080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Suez J, Korem T, Zeevi D, Zilberman-Schapira G, Thaiss CA, Maza O, Israeli D, Zmora N, Gilad S, Weinberger A, et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature. 2014;514:181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matsumoto K, Takada T, Shimizu K, Moriyama K, Kawakami K, Hirano K, Kajimoto O, Nomoto K. Effects of a probiotic fermented milk beverage containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on defecation frequency, intestinal microbiota, and the intestinal environment of healthy individuals with soft stools. J. Biosci. Bioeng 2010;110:547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang Y-J, Sheu B-S. Probiotics-containing yogurts suppress Helicobacter pylori load and modify immune response and intestinal microbiota in the Helicobacter pylori-infected children. Helicobacter. 2012;17:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zabat MA, Sano WH, Wurster JI, Cabral DJ, Belenky P. Microbial Community Analysis of Sauerkraut Fermentation Reveals a Stable and Rapidly Established Community. Foods. 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marco ML, Heeney D, Binda S, Cifelli CJ, Cotter PD, Foligné B, Gänzle M, Kort R, Pasin G, Pihlanto A, et al. Health benefits of fermented foods: microbiota and beyond. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2017;44:94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nozue M, Shimazu T, Sasazuki S, Charvat H, Mori N, Mutoh M, Sawada N, Iwasaki M, Yamaji T, Inoue M, et al. Fermented Soy Product Intake Is Inversely Associated with the Development of High Blood Pressure: The Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study. J. Nutr 2017;147:1749–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.He T, Priebe MG, Zhong Y, Huang C, Harmsen HJM, Raangs GC, Antoine J-M, Welling GW, Vonk RJ. Effects of yogurt and bifidobacteria supplementation on the colonic microbiota in lactose-intolerant subjects. J. Appl. Microbiol 2008;104:595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stanhope KL, Goran MI, Bosy-Westphal A, King JC, Schmidt LA, Schwarz J-M, Stice E, Sylvetsky AC, Turnbaugh PJ, Bray GA, et al. Pathways and mechanisms linking dietary components to cardiometabolic disease: thinking beyond calories. Obes Rev. 2018;19:1205–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peters BA, Shapiro JA, Church TR, Miller G, Trinh-Shevrin C, Yuen E, Friedlander C, Hayes RB, Ahn J. A taxonomic signature of obesity in a large study of American adults. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mbakwa CA, Hermes GDA, Penders J, Savelkoul PHM, Thijs C, Dagnelie PC, Mommers M, Zoetendal EG, Smidt H, Arts ICW. Gut Microbiota and Body Weight in School-Aged Children: The KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kalliomäki M, Collado MC, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Early differences in fecal microbiota composition in children may predict overweight. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 2008;87:534–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Cheng J, Duncan AE, Kau AL, Griffin NW, Lombard V, Henrissat B, Bain JR, et al. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;341:1241214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Murphy EF, Cotter PD, Healy S, Marques TM, O’Sullivan O, Fouhy F, Clarke SF, O’Toole PW, Quigley EM, Stanton C, et al. Composition and energy harvesting capacity of the gut microbiota: relationship to diet, obesity and time in mouse models. Gut. 2010;59:1635–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Arora T, Sharma R. Fermentation potential of the gut microbiome: implications for energy homeostasis and weight management. Nutr. Rev 2011;69:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boscaini S, Leigh S-J, Lavelle A, García-Cabrerizo R, Lipuma T, Clarke G, Schellekens H, Cryan JF. Microbiota and body weight control: Weight watchers within? Mol Metab. 2022;57:101427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sergeev IN, Aljutaily T, Walton G, Huarte E. Effects of Synbiotic Supplement on Human Gut Microbiota, Body Composition and Weight Loss in Obesity. Nutrients. 2020;12:222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.De Filippo C, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Albanese D, Pieraccini G, Banci E, Miglietta F, Cavalieri D, Lionetti P. Diet, Environments, and Gut Microbiota. A Preliminary Investigation in Children Living in Rural and Urban Burkina Faso and Italy. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sun S, Wang H, Howard AG, Zhang J, Su C, Wang Z, Du S, Fodor AA, Gordon-Larsen P, Zhang B. Loss of Novel Diversity in Human Gut Microbiota Associated with Ongoing Urbanization in China. mSystems. 2022;7:e0020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bai X, Sun Y, Li Y, Li M, Cao Z, Huang Z, Zhang F, Yan P, Wang L, Luo J, et al. Landscape of the gut archaeome in association with geography, ethnicity, urbanization, and diet in the Chinese population. Microbiome. 2022;10:147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Laursen MF, Zachariassen G, Bahl MI, Bergström A, Høst A, Michaelsen KF, Licht TR. Having older siblings is associated with gut microbiota development during early childhood. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Azad MB, Konya T, Maughan H, Guttman DS, Field CJ, Sears MR, Becker AB, Scott JA, Kozyrskyj AL, CHILD Study Investigators. Infant gut microbiota and the hygiene hypothesis of allergic disease: impact of household pets and siblings on microbiota composition and diversity. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology. 2013;9:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tun HM, Konya T, Takaro TK, Brook JR, Chari R, Field CJ, Guttman DS, Becker AB, Mandhane PJ, Turvey SE, et al. Exposure to household furry pets influences the gut microbiota of infant at 3–4 months following various birth scenarios. Microbiome. 2017;5:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Penders J, Thijs C, Vink C, Stelma FF, Snijders B, Kummeling I, Brandt PA van den, Stobberingh EE. Factors Influencing the Composition of the Intestinal Microbiota in Early Infancy. Pediatrics. 2006;118:511–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108 Suppl 1:4554–4561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cox LM, Yamanishi S, Sohn J, Alekseyenko AV, Leung JM, Cho I, Kim SG, Li H, Gao Z, Mahana D, et al. Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell. 2014;158:705–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nicolini G, Sperotto F, Esposito S. Combating the rise of antibiotic resistance in children. Minerva Pediatr. 2014;66:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Azad MB, Moossavi S, Owora A, Sepehri S. Early-Life Antibiotic Exposure, Gut Microbiota Development, and Predisposition to Obesity. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2017;88:67–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Turta O, Rautava S. Antibiotics, obesity and the link to microbes - what are we doing to our children? BMC Med. 2016;14:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cox LM, Blaser MJ. Antibiotics in early life and obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yallapragada SG, Nash CB, Robinson DT. Early-Life Exposure to Antibiotics, Alterations in the Intestinal Microbiome, and Risk of Metabolic Disease in Children and Adults. Pediatr Ann. 2015;44:e265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ajslev TA, Andersen CS, Gamborg M, Sørensen TIA, Jess T. Childhood overweight after establishment of the gut microbiota: the role of delivery mode, pre-pregnancy weight and early administration of antibiotics. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35:522–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bailey LC, Forrest CB, Zhang P, Richards TM, Livshits A, DeRusso PA. Association of antibiotics in infancy with early childhood obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:1063–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Murphy R, Stewart AW, Braithwaite I, Beasley R, Hancox RJ, Mitchell EA, ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Antibiotic treatment during infancy and increased body mass index in boys: an international cross-sectional study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38:1115–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cho I, Yamanishi S, Cox L, Methé BA, Zavadil J, Li K, Gao Z, Mahana D, Raju K, Teitler I, et al. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature. 2012;488:621–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mahana D, Trent CM, Kurtz ZD, Bokulich NA, Battaglia T, Chung J, Müller CL, Li H, Bonneau RA, Blaser MJ. Antibiotic perturbation of the murine gut microbiome enhances the adiposity, insulin resistance, and liver disease associated with high-fat diet. Genome Med. 2016;8:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schulfer AF, Schluter J, Zhang Y, Brown Q, Pathmasiri W, McRitchie S, Sumner S, Li H, Xavier JB, Blaser MJ. The impact of early-life sub-therapeutic antibiotic treatment (STAT) on excessive weight is robust despite transfer of intestinal microbes. ISME J. 2019;13:1280–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tuteja S, Ferguson JF. Gut Microbiome and Response to Cardiovascular Drugs. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2019;12:421–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Aziz RK, Hegazy SM, Yasser R, Rizkallah MR, ElRakaiby MT. Drug pharmacomicrobiomics and toxicomicrobiomics: from scattered reports to systematic studies of drug-microbiome interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2018;1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wilson ID, Nicholson JK. Gut microbiome interactions with drug metabolism, efficacy, and toxicity. Transl Res. 2017;179:204–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Koppel N, Maini Rekdal V, Balskus EP. Chemical transformation of xenobiotics by the human gut microbiota. Science. 2017;356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Weersma RK, Zhernakova A, Fu J. Interaction between drugs and the gut microbiome. Gut. 2020;69:1510–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dong S, Liu Q, Zhou X, Zhao Y, Yang K, Li L, Zhu D. Effects of Losartan, Atorvastatin, and Aspirin on Blood Pressure and Gut Microbiota in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Molecules. 2023;28:612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Robles-Vera I, Toral M, de la Visitación N, Sánchez M, Gómez-Guzmán M, Muñoz R, Algieri F, Vezza T, Jiménez R, Gálvez J, et al. Changes to the gut microbiota induced by losartan contributes to its antihypertensive effects. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:2006–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Vieira-Silva S, Falony G, Belda E, Nielsen T, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Chakaroun R, Forslund SK, Assmann K, Valles-Colomer M, Nguyen TTD, et al. Statin therapy is associated with lower prevalence of gut microbiota dysbiosis. Nature. 2020;581:310–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Imhann F, Vich Vila A, Bonder MJ, Lopez Manosalva AG, Koonen DPY, Fu J, Wijmenga C, Zhernakova A, Weersma RK. The influence of proton pump inhibitors and other commonly used medication on the gut microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2017;8:351–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wu H, Esteve E, Tremaroli V, Khan MT, Caesar R, Mannerås-Holm L, Ståhlman M, Olsson LM, Serino M, Planas-Fèlix M, et al. Metformin alters the gut microbiome of individuals with treatment-naive type 2 diabetes, contributing to the therapeutic effects of the drug. Nat Med. 2017;23:850–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Forslund SK, Chakaroun R, Zimmermann-Kogadeeva M, Markó L, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Nielsen T, Moitinho-Silva L, Schmidt TSB, Falony G, Vieira-Silva S, et al. Combinatorial, additive and dose-dependent drug-microbiome associations. Nature. 2021;600:500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ou J, Elizalde P, Guo H-B, Qin H, Tobe BTD, Choy JS. TCA and SSRI Antidepressants Exert Selection Pressure for Efflux-Dependent Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms in Escherichia coli. mBio. 2022;13:e0219122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Vich Vila A, Collij V, Sanna S, Sinha T, Imhann F, Bourgonje AR, Mujagic Z, Jonkers DMAE, Masclee AAM, Fu J, et al. Impact of commonly used drugs on the composition and metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Nat Commun. 2020;11:362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zimmermann P, Curtis N. The influence of the intestinal microbiome on vaccine responses. Vaccine. 2018;36:4433–4439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Huda MN, Lewis Z, Kalanetra KM, Rashid M, Ahmad SM, Raqib R, Qadri F, Underwood MA, Mills DA, Stephensen CB. Stool microbiota and vaccine responses of infants. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e362–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mullié C, Yazourh A, Thibault H, Odou M-F, Singer E, Kalach N, Kremp O, Romond M-B. Increased poliovirus-specific intestinal antibody response coincides with promotion of Bifidobacterium longum-infantis and Bifidobacterium breve in infants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr. Res 2004;56:791–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Alexander JL, Mullish BH, Danckert NP, Liu Z, Olbei ML, Saifuddin A, Torkizadeh M, Ibraheim H, Blanco JM, Roberts LA, et al. The gut microbiota and metabolome are associated with diminished COVID-19 vaccine-induced antibody responses in immunosuppressed inflammatory bowel disease patients. EBioMedicine. 2023;88:104430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Goodrich JK, Waters JL, Poole AC, Sutter JL, Koren O, Blekhman R, Beaumont M, Van Treuren W, Knight R, Bell JT, et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell. 2014;159:789–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhernakova DV, Le TH, Kurilshikov A, Atanasovska B, Bonder MJ, Sanna S, Claringbould A, Võsa U, Deelen P, LifeLines cohort study, et al. Individual variations in cardiovascular-disease-related protein levels are driven by genetics and gut microbiome. Nat. Genet 2018; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kolde R, Franzosa EA, Rahnavard G, Hall AB, Vlamakis H, Stevens C, Daly MJ, Xavier RJ, Huttenhower C. Host genetic variation and its microbiome interactions within the Human Microbiome Project. Genome Med. 2018;10:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lopera-Maya EA, Kurilshikov A, van der Graaf A, Hu S, Andreu-Sánchez S, Chen L, Vila AV, Gacesa R, Sinha T, Collij V, et al. Effect of host genetics on the gut microbiome in 7,738 participants of the Dutch Microbiome Project. Nat Genet. 2022;54:143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Blekhman R, Goodrich JK, Huang K, Sun Q, Bukowski R, Bell JT, Spector TD, Keinan A, Ley RE, Gevers D, et al. Host genetic variation impacts microbiome composition across human body sites. Genome Biol. 2015;16:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Draisma HH, Pool R, Kobl M, Jansen R, Petersen AK, Vaarhorst AA, Yet I, Haller T, Demirkan A, Esko T, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel genetic variants contributing to variation in blood metabolite levels. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wang J, Thingholm LB, Skiecevičienė J, Rausch P, Kummen M, Hov JR, Degenhardt F, Heinsen F-A, Rühlemann MC, Szymczak S, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies variation in vitamin D receptor and other host factors influencing the gut microbiota. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1396–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Bonder MJ, Kurilshikov A, Tigchelaar EF, Mujagic Z, Imhann F, Vila AV, Deelen P, Vatanen T, Schirmer M, Smeekens SP, et al. The effect of host genetics on the gut microbiome. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1407–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Davenport ER, Cusanovich DA, Michelini K, Barreiro LB, Ober C, Gilad Y. Genome-Wide Association Studies of the Human Gut Microbiota. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Xie H, Guo R, Zhong H, Feng Q, Lan Z, Qin B, Ward KJ, Jackson MA, Xia Y, Chen X, et al. Shotgun Metagenomics of 250 Adult Twins Reveals Genetic and Environmental Impacts on the Gut Microbiome. Cell Syst. 2016;3:572–584.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hughes DA, Bacigalupe R, Wang J, Rühlemann MC, Tito RY, Falony G, Joossens M, Vieira-Silva S, Henckaerts L, Rymenans L, et al. Genome-wide associations of human gut microbiome variation and implications for causal inference analyses. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:1079–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Markowitz RHG, LaBella AL, Shi M, Rokas A, Capra JA, Ferguson JF, Mosley JD, Bordenstein SR. Microbiome-associated human genetic variants impact phenome-wide disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119:e2200551119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Qin Y, Havulinna AS, Liu Y, Jousilahti P, Ritchie SC, Tokolyi A, Sanders JG, Valsta L, Brożyńska M, Zhu Q, et al. Combined effects of host genetics and diet on human gut microbiota and incident disease in a single population cohort. Nat Genet. 2022;54:134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Liu X, Tang S, Zhong H, Tong X, Jie Z, Ding Q, Wang D, Guo R, Xiao L, Xu X, et al. A genome-wide association study for gut metagenome in Chinese adults illuminates complex diseases. Cell Discov. 2021;7:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kurilshikov A, Medina-Gomez C, Bacigalupe R, Radjabzadeh D, Wang J, Demirkan A, Le Roy CI, Raygoza Garay JA, Finnicum CT, Liu X, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify host factors influencing human gut microbiome composition. Nat Genet. 2021;53:156–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Groot HE, van de Vegte YJ, Verweij N, Lipsic E, Karper JC, van der Harst P. Human genetic determinants of the gut microbiome and their associations with health and disease: a phenome-wide association study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Scepanovic P, Hodel F, Mondot S, Partula V, Byrd A, Hammer C, Alanio C, Bergstedt J, Patin E, Touvier M, et al. A comprehensive assessment of demographic, environmental, and host genetic associations with gut microbiome diversity in healthy individuals. Microbiome. 2019;7:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mohammadkhah AI, Simpson EB, Patterson SG, Ferguson JF. Development of the Gut Microbiome in Children, and Lifetime Implications for Obesity and Cardiometabolic Disease. Children (Basel). 2018;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zheng D, Liwinski T, Elinav E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020;30:492–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Danesh J, Whincup P, Walker M, Lennon L, Thomson A, Appleby P, Gallimore JR, Pepys MB. Low grade inflammation and coronary heart disease: prospective study and updated meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical research ed. 2000;321:199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kedmi R, Najar TA, Mesa KR, Grayson A, Kroehling L, Hao Y, Hao S, Pokrovskii M, Xu M, Talbot J, et al. A RORγt+ cell instructs gut microbiota-specific Treg cell differentiation. Nature. 2022;610:737–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Nutsch K, Chai JN, Ai TL, Russler-Germain E, Feehley T, Nagler CR, Hsieh C-S. Rapid and Efficient Generation of Regulatory T Cells to Commensal Antigens in the Periphery. Cell Rep. 2016;17:206–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Lyu M, Suzuki H, Kang L, Gaspal F, Zhou W, Goc J, Zhou L, Zhou J, Zhang W, JRI Live Cell Bank, et al. ILC3s select microbiota-specific regulatory T cells to establish tolerance in the gut. Nature. 2022;610:744–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, Wei D, Goldfarb KC, Santee CA, Lynch SV, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Wilck N, Matus MG, Kearney SM, Olesen SW, Forslund K, Bartolomaeus H, Haase S, Mähler A, Balogh A, Markó L, et al. Salt-responsive gut commensal modulates TH17 axis and disease. Nature. 2017;551:585–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]