Abstract

Escherichia coli endonuclease VIII and endonuclease III are oxidative base excision repair DNA glycosylases that remove oxidized pyrimidines from DNA. The genes encoding these proteins, nei and nth, are both co-transcribed as the terminal genes in operons. nei is the terminal gene in an operon with four open reading frames that encode proteins of unknown function. This operon has two confirmed transcription initiation sites upstream of the first open reading frame and two transcript termination sites downstream of nei. nth is the terminal gene in an operon with seven open reading frames that encode proteins of unknown function. The six open reading frames immediately upstream of nth show homology to the genes rnfA, rnfB, rnfC, rnfD, rnfG and rnfE from Rhodobacter capsulatis. The rnf genes are required for nitrogen fixation in R.capsulatis and have been predicted to make up a membrane complex involved in electron transport to nitrogenase. The nth operon has transcription initiation sites upstream of the first and second open reading frames and a single transcript termination site downstream of nth. The order of genes in these operons has been conserved or partially conserved in other bacteria, although it is not known whether the genes are co-transcribed in these other organisms.

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli endonuclease VIII (endo VIII) and endonuclease III (endo III) are oxidative base excision repair proteins with overlapping substrate specificities that remove oxidized pyrimidine bases from DNA. These enzymes remove potentially lethal lesions such as thymine glycol and urea that are blocks to DNA replication in vitro and are lethal in vivo (for reviews see 1,2). nth (endo III) mutants are not X-ray sensitive and nei (endo VIII) mutants are only slightly X-ray sensitive, but nth nei double mutants are 1.4-fold more sensitive than wild-type cells (3). The double mutants are also 3- to 4-fold more sensitive to hydrogen peroxide than wild-type cells (4,5). These data show that X-rays and hydrogen peroxide form lethal lesions that are not repaired in the nth nei double mutants. For the most part, the single mutants exhibit wild-type sensitivity to X-rays indicating that the enzymes are able to substitute for each other in the cells. Endo VIII and endo III also remove free radical damaged cytosines, uracil glycol, dihydrouracil, 5-hydroxyuracil and 5-hydroxycytosine, all of which can mispair with adenosine during DNA synthesis in vitro (6) and are mutagenic (7,8). nth mutants have a mild mutator phenotype, while nei mutants exhibit the same spontaneous mutation frequency as wild-type cells (3). Double mutants show a 20-fold increase in spontaneous mutation frequency (3) and all the mutations are C→T transitions (9). Again, it appears that the enzymes can substitute for each other in cells since the single mutants do not show a significant phenotype, although endo III appears to remove some premutagenic lesions that are not substrates for endo VIII.

There have been few studies on the regulation of oxidative base excision repair DNA glycosylases. No increase in endo VIII levels is observed after the administration of hydrogen peroxide, paraquat, agents that induce the SOS response, or in oxyR or soxR mutants constitutive for the hydrogen peroxide and superoxide inducible responses, respectively (10). There have been no reported studies on endo III regulation. Although our major goal is to define the regulatory controls for endo VIII and endo III, we first wanted to determine the transcriptional organization of nei and nth. If nei and nth are co-transcribed with surrounding genes, the other genes in the operons may play a role in or provide information about the regulation of the DNA glycosylases. We also wanted to determine if there was more than one promoter controlling the transcription of nei and nth. In this paper we report the transcript mapping of nei and nth and show that both genes are co-transcribed as the terminal genes in operons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains

Escherichia coli GC4468 [DE(argF-lac)169 λ– IN(rrnD-rrnE)1 rpsL179(strR)] was obtained from the Yale University E.coli Genetic Stock Center.

Growth conditions and RNA isolation

Escherichia coli GC4468 cultures were grown as previously described (11). Total RNA was isolated with a Qiagen RNeasy kit, the RNA was then treated with DNase, extracted twice with acid pH phenol and extracted once with chloroform/isoamyl alcohol. The RNA was precipitated and resuspended in RNase-free water.

Reverse transcription (RT)–PCR

RNA was reverse transcribed and PCR was performed as previously described (11). Briefly, total RNA (30 µg) and primer (15 pmol) were denatured in water for 10 min at 80°C and then quickly chilled on ice. Gibco BRL 1× first strand buffer, 10 mM dithiothreitol and 500 µM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) were added to the annealing mix and incubated at 47°C for 2 min. Superscript II (1 µl, 200 U) was added to a final volume of 20 µl and the reaction mixture was incubated for 1 h at 47°C. For each primer used in RT, a negative control lacking reverse transcriptase was run.

RNase protection assays

RNase protection assays (RPAs) were performed with an Ambion RPA II kit as previously described (11). Briefly, probe template was transcribed and then run on a 5% polyacrylamide gel for purification. Escherichia coli RNA (30 µg) was hybridized overnight with the labeled RNA probe (10 000 c.p.m.) at 47°C in hybridization buffer. Unhybridized probe was digested with RNase A and RNase T1, the RNases were inactivated and the remaining RNA was precipitated. The pellet was resuspended in formamide gel loading buffer and the sample was run on a 5% polyacrylamide gel.

Primer extension analysis

Primers were labeled as previously described (11). Total RNA (30 µg) and primer (2 pmol) were annealed in water by heating at 80°C for 10 min and then quickly chilling on ice. Gibco BRL 1× first strand buffer, 10 mM dithiothreitol and 500 µM each dNTP were added and the reaction was heated at 47°C for 2 min. Superscript II (1 µl, 200 U) was added and the reaction was incubated at 47°C for 1 h. The nucleic acids were precipitated and then resuspended in 5 µl of formamide gel loading buffer. A sequencing ladder was generated from control M13mp18 DNA with a US Biochemicals Sequenase v.2.0 sequencing kit.

Homology search

The amino acid sequence for the product of each gene in the nei and nth operons was used in a BLAST search at the Unfinished NCBI Microbial Genome BLAST Website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/unfinishedgenome.html ). On this web page, the ‘All’ option was chosen to search both the finished and unfinished genomes. The program used was tblastn. The amino acid sequences for the products of the genes in the nei operon were obtained from GenBank accession no. AE000174 and those for the nth operon were obtained from GenBank accession no. AE000258. Sequences from all organisms were aligned using the subject numbers provided by the BLAST searches.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

nei is part of an operon containing five genes

The nei transcript was initially mapped by RT–PCR to determine if it is transcribed alone or with surrounding genes. There are four open reading frames (ORFs) upstream of nei that have the same orientation and could potentially be transcribed with nei. These ORFs are designated ybgI, ybgJ, ybgK and ybgL in GenBank accession no. AE000174, with ybgL immediately 5′ to nei. These ORFs encode proteins of unknown function. The gene immediately 3′ to nei, abrB, has been shown to be in the opposite orientation (M.Volkert, personal communication). Escherichia coli total RNA was reverse transcribed with primer nei19 (Fig. 1A shows the approximate annealing locations of the primers used in RT–PCR), which anneals 336 bp 3′ to the nei start codon, and PCR was performed to determine the approximate size of the cDNA. Primer nei2 was the downstream primer and primers nei7 and nei8 were the upstream primers used in the PCR. Positive PCR controls were run with the two primer sets and genomic DNA as the template (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 4). PCR with primer set nei7/nei2 yielded a product (Fig. 1B, lane 3), indicating that the transcript extends from ybgI through nei. PCR with primer set nei8/nei2 did not yield a product (Fig. 1B, lane 6), indicating that the upstream transcription initiation site for the operon is within 428 bp of the ybgI start codon. The negative control lanes (the PCR template was a RT reaction minus reverse transcriptase) were empty, showing that the RNA used in RT was not contaminated with DNA (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 5).

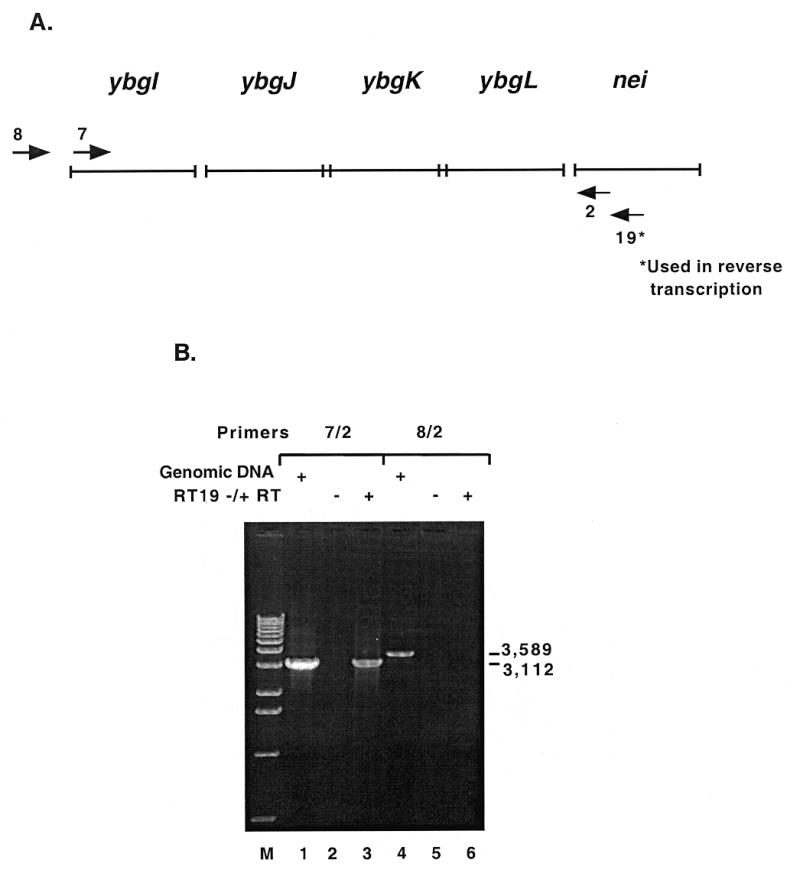

Figure 1.

Mapping of the nei transcript by RT–PCR. (A) The arrows numbered 2, 7 and 8 represent the primers used in PCR. The arrow numbered 19* represents the primer used to reverse transcribe E.coli total RNA. Primer nei2 anneals 53 bp 3′ to the nei start codon; nei7 anneals 3059 bp 5′ to the nei start codon; nei8 anneals 3536 bp 5′ to the nei start codon. (B) The primer sets used in PCR are indicated above the lanes. Lanes 1 and 4 are positive controls with E.coli genomic DNA as the PCR template. Lanes 2 and 5 are minus reverse transcriptase. Lanes 3 and 6 show PCR results obtained with cDNA from RT with primer 19* (RT19) as the template. The size of the PCR products are indicated in base pairs to the right.

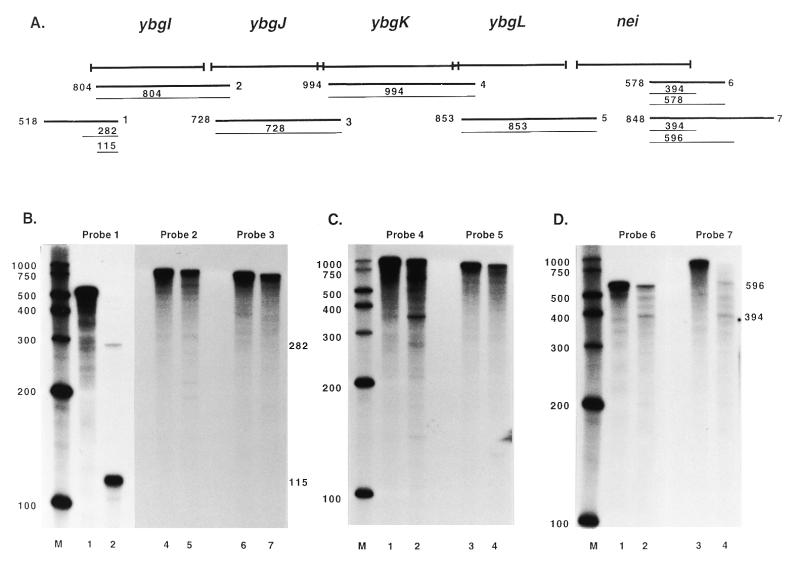

Figure 2.

Mapping of the nei transcript by RPAs. (A) The thick lines designated 1–7 indicate the approximate annealing locations of the probes used in the RPAs. The thin lines indicate the products obtained from RPAs with these probes along with the sizes of the products. The sizes and exact annealing locations of the probes are as follows: probe 1, 518 nt, anneals from 90 bp 3′ to the ybgI start codon to 428 bp 5′ to the ybgI start codon; probe 2, 804 nt, anneals from 146 bp 3′ to the ybgJ start codon to 50 bp 3′ to the ybgI start codon; probe 3, 728 nt, anneals from 87 bp 3′ to the ybgK start codon to 10 bp 3′ to the ybgJ start codon; probe 4, 994 nt, anneals from 81 bp 3′ to the ybgL start codon to 21 bp 3′ to the ybgK start codon; probe 5, 853 nt, anneals from 94 bp 3′ to the nei start codon to 12 bp 3′ to the ybgL start codon; probe 6, 578 nt, anneals from 263 bp 3′ to the nei stop codon to 315 bp 5′ to the nei stop codon; probe 7, 848 nt, anneals from 533 bp 3′ to the nei stop codon to 315 bp 5′ to the nei stop codon. (B–D) The probes used in the RPAs are indicated and lane M contains RNA size markers. Lanes 1, 3 and 5 in (B) and lanes 1 and 3 in (C) and (D) show the full-length probe (probe hybridized with yeast RNA and mock digested; only part of the reaction was loaded so that the signal would not overpower the other lanes). Lanes 2, 4 and 6 in (B) and lanes 2 and 4 in (C) and (D) show RPA results. Numbers beside the panels are in base pairs.

The nei operon contains no internal promoters

RPAs were performed to map the locations of promoters and terminators in the operon. The antisense RNA probes used in the RPAs were designed to span the length of the operon from 5′ of the ybgI start codon to 3′ of the nei start codon (Fig. 2A). The RPA with probe 1 resulted in a 282 and a 115 nt product (Fig. 2B, lane 2) as predicted with a semilog plot of the distance traveled by the RNA markers. These products correspond to possible transcription initiation sites 192 and 25 bp 5′ to the ybgI start codon, respectively. Primer extension analysis was performed with primer 17 (Fig. 3A) to more precisely map the site corresponding to the 282 nt RPA product. Primer 17 was extended to a product of 115 nt (Fig. 3B, lane 1), indicating there is a transcription initiation site at an A residue 208 bp 5′ of the ybgI start codon. The site is separated by 6 nt from a possible –10 hexamer (TGTGTT), but there is no good match for a –35 hexamer. The site corresponding to the 115 nt RPA product was mapped by primer extension analysis with primer 16. Primer 16 was extended to products of 99 and 124 nt (Fig. 3B, lane 2). The size of the 124 nt product indicates that there is a transcription initiation site 29 bp 5′ to the ybgI start codon. This matches the RPA results within 4 nt. The site corresponds to a G residue and is separated by 6 bp from a possible –10 hexamer (TATGTT) which is separated by 17 bp from a possible –35 hexamer (TCGACG). Because of the position it maps to, it seems unlikely that the 99 nt product corresponds to a transcription initiation site upstream of ybgI. The sequence GAAGG is separated by 7 bp from the ybgI start codon and corresponds to part of the Shine–Dalgarno consensus sequence UAAGGAGGU. The size of the 99 nt product would place a transcription initiation site 4 bp 5′ to the ybgI start codon, between the putative ribosome binding site and the start codon. It is possible that the 99 nt product was the result of non-specific binding of the primer. The RPA with probe 1 also resulted in very faint 474 and 426 nt products corresponding to possible transcription initiation sites 384 and 336 bp 5′ to the ybgI start codon. Attempts to map these sites by primer extension analysis were inconclusive, indicating that they correspond either to artifacts or to promoters that are too weak to be detected by primer extension.

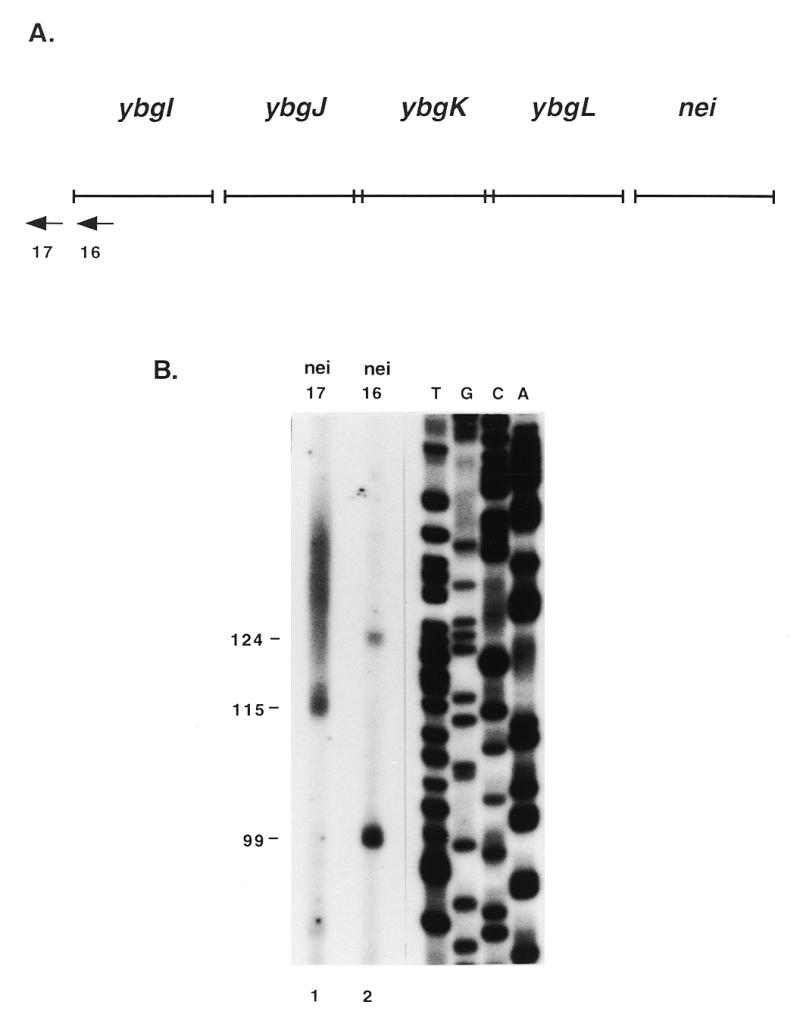

Figure 3.

Mapping of nei transcription initiation sites by primer extension analysis. (A) Arrows indicate primers used in primer extension analysis. nei16 anneals 95 bp 3′ to the predicted ybgI start codon; nei17 anneals 93 bp 5′ to the predicted ybgI start codon. (B) Lane 1, primer extension with primer nei17; lane 2, primer extension with primer nei16. The size of the products are indicated in base pairs to the left of the figure.

The RPAs with probes 2–5 all resulted in full-length products (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 and 7, and C, lanes 2 and 4) that correspond to transcript read-through from the upstream ORFs. The RPA with probe 4 also resulted in some products shorter than full-length which disappeared after RNase T1 digestion alone (data not shown), suggesting that the bands corresponded to RNase A-sensitive sites. It was of particular interest to determine if nei has an independent promoter. The results with probe 5 do not support this being the case, at least under aerobic growth conditions in Luria–Bertani broth. When nei was sequenced it was reported that there are potential –35 (TTGTTG) and –10 (TAATAA) like hexamers upstream of the nei start site (3). In the present study no promoters were observed upstream of nei but it is possible that the putative promoter is active under stress conditions.

Probes 6 and 7 were used to map the terminator(s) of the operon. The RPA with probe 6 resulted in a full-length product and a 394 nt product (Fig. 2D, lane 2). The RPA with probe 7 resulted in products of 394 and 596 nt and an upward smear towards full-length, but no distinct full-length product was detected (Fig. 2D, lane 4). These results indicate that there are termination sites 79 and 281 bp 3′ of the nei stop codon and that there may be some additional read-through past the second termination site. Both of these sites correspond to potential stem–loop structures identified by the Genetics Computer Groups’ program Stemloop. Neither of the potential stem–loops are followed by a run of T residues, suggesting that they may correspond to rho-dependent terminators.

Taken together, these results indicate that nei is co-transcribed as the terminal gene in a five gene operon. There are two confirmed transcription initiation sites upstream of the predicted ybgI start codon and two transcript termination sites downstream of the nei stop codon.

nth is part of an operon containing eight genes

There are eight ORFs upstream of nth that have the same orientation, as predicted in GenBank accession no. AE000258, and could potentially be transcribed with nth. These are designated ydgT, ydgK, ydgL, ydgM, ydgN, ydgO, ydgP and ydgQ on EcoMap10 (12) and are also designated b1625–b1632 in GenBank accession no. AE000258. ydgQ is immediately 5′ of nth. The closest ORF 3′ of nth is predicted to be over 600 bp downstream, so is unlikely to be transcribed with nth.

To determine whether any of these ORFs are co-transcribed with nth, E.coli total RNA was reverse transcribed with two different primers. Primer nth2 anneals 53 bp 3′ to the nth start codon and nth5 anneals 566 bp 3′ to the nth start codon (Fig. 4A). The cDNA from each RT reaction was used as a template in PCR reactions to determine their approximate length. nth20 was the downstream primer and nth19 and nth22 were the upstream primers used in the PCR. Positive PCR controls were run with the two primer sets and genomic DNA as the template (Fig. 4B, lanes 1, 4, 10 and 13). PCR with primer set nth19/nth20 yielded a product in reactions with the cDNA template made with both primer nth2 (Fig. 4B, lane 3) and primer nth5 (Fig. 4B, lane 12), suggesting that ydgK through nth are contained on the same transcript. PCR with primer set nth22/nth20 did not yield a product in reactions with the cDNA template made with either primer (Fig. 4B, lanes 6 and 15), indicating that the transcript begins between the annealing site of nth22 and the annealing site of nth19. The experiments were not designed to determine whether ydgT is part of the operon. It should be pointed out that it was not possible to obtain PCR product that spanned the length from ydgK to nth, but it was possible to obtain smaller PCR products along the length of ydgK to nth (data not shown). This could be due to low abundance RNA transcripts leading to poor production of cDNA in the reverse transcription reaction. The negative control lanes were empty, showing that the RNA used in RT was not contaminated with DNA (Fig. 4B, lanes 2, 5, 11 and 14).

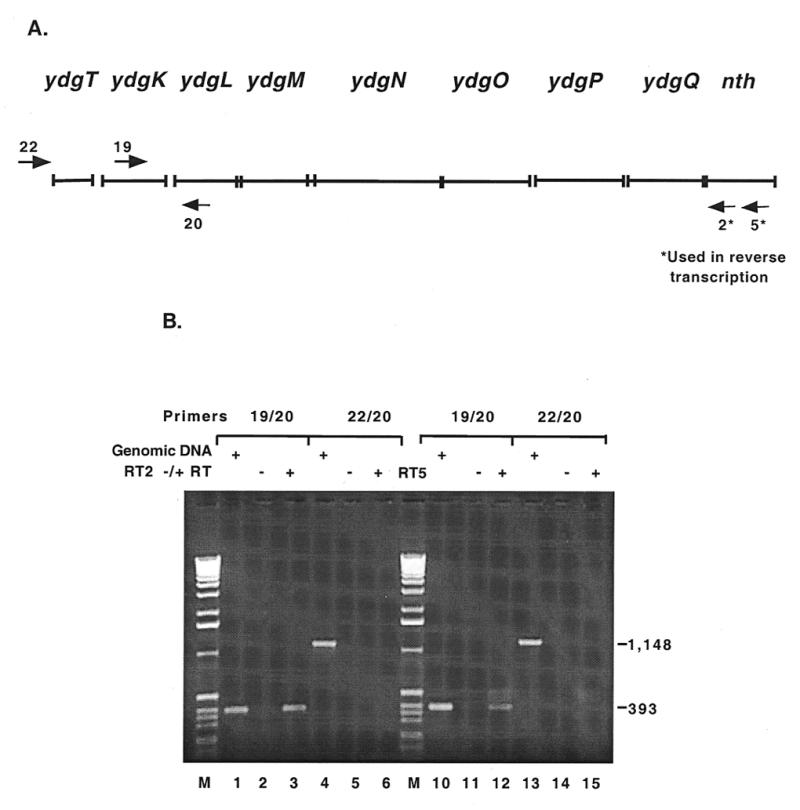

Figure 4.

Mapping of the nth transcript by RT–PCR. (A) The arrows numbered 20, 19 and 22 represent the primers used in PCR. The arrows numbered 2* and 5* represent the primers used to reverse transcribe E.coli total RNA. Primer nth20 anneals 88 bp 3′ to the predicted ydgL start codon, nei19 anneals 236 bp 3′ to the predicted ydgK start codon and nei22 anneals 242 bp 5′ to the predicted ydgT start codon. (B) Lanes 1, 4, 10 and 13 are positive controls with E.coli genomic DNA as the PCR template. Lanes 2 and 5 are negative controls with RT reaction mixtures minus reverse transcriptase with primer 2* as the PCR template. Lanes 11 and 14 are the negative controls for primer 5*. Lanes 3 and 6 show PCR results with the cDNA from reverse transcription with primer 2* (RT2) as template. Lanes 12 and 15 show PCR results obtained with the cDNA from RT with primer 5* (RT5) as the template.

The nth operon contains two promoters

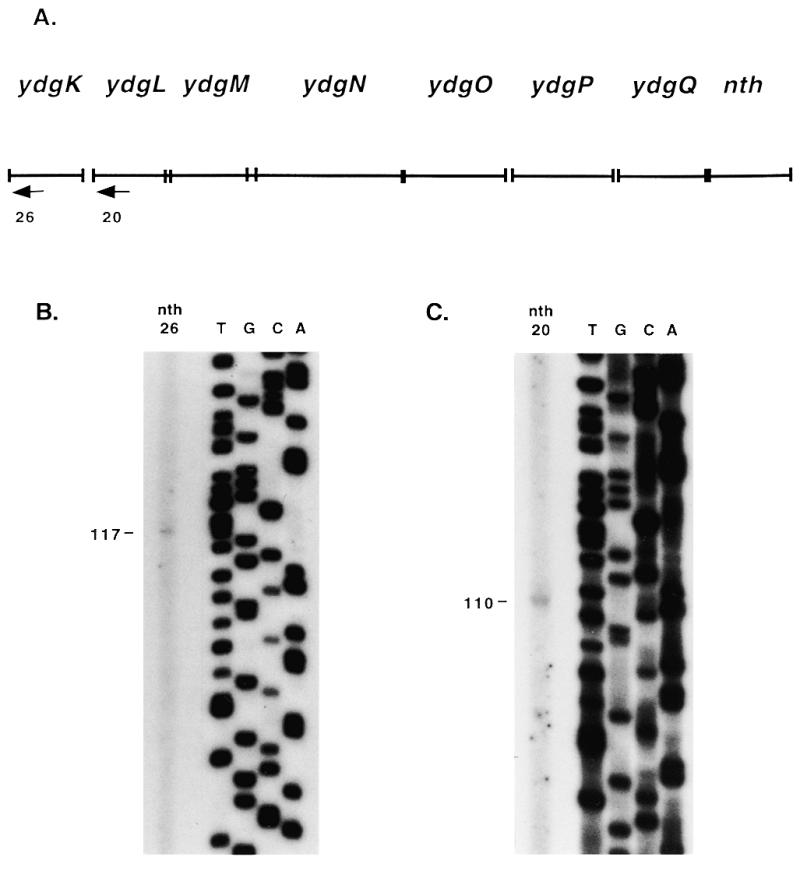

RPAs were performed to confirm the RT–PCR results, to determine if ydgT is part of the operon and to determine the locations of promoters and terminators in the operon. The RNA antisense probes used in the RPAs were designed to span the length of the operon from 5′ of the ydgT start codon to 3′ of the nth start codon (Figs 5A and 6A). The RPA with probe 1 resulted in a 320 nt product (Fig. 5B, lane 2). There was some faint smearing above the 320 nt product but no other distinct products were observed. The size of the product suggests that it corresponds to a transcription initiation site 4 bp 5′ to the ydgK start codon. The lack of a larger product indicates that ydgT is not co-transcribed with the downstream genes. Primer extension analysis was performed with primer nth26 which was extended to a product of 117 nt (Fig. 7B), confirming that there is an initiation site at a T residue 18 bp 5′ to the ydgK start codon. This site is separated by 7 nt from one possible –10 hexamer (TAATAA) and is separated by 9 nt from another (TATAAT). These –10 hexamers are separated by 18 and 16 nt, respectively, from a possible –35 hexamer (TAGCGA).

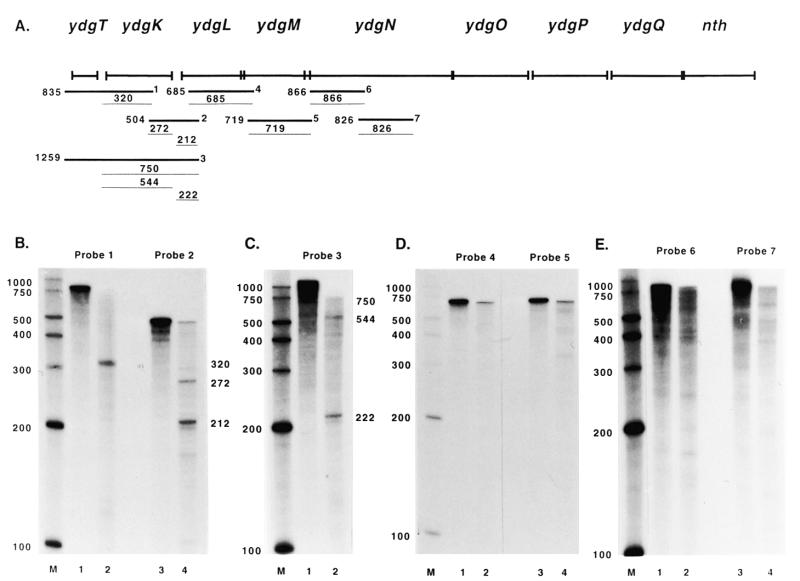

Figure 5.

Mapping of the nth transcript by RPAs. (A) The thick lines designated 1–7 indicate the approximate annealing locations of the probes used in the RPAs. The thin lines indicate the products obtained from RPAs with these probes along with the sizes of the products. The sizes and exact annealing locations of the probes are as follows: probe 1, 835 nt, anneals from 316 bp 3′ to the ydgK start codon to 519 bp 5′ to the ydgK start codon; probe 2, 504 nt, anneals from 199 bp 3′ to the ydgL start codon to 305 bp 5′ to the ydgK start codon; probe 3, 1259 nt, anneals from 199 bp 3′ to the ydgL start codon to 519 bp 5′ to the ydgK start codon; probe 4, 685 nt, anneals from 113 bp 3′ to the ydgM start codon to 10 bp 3′ to the ydgL start codon; probe 5, 719 nt, anneals from 150 bp 3′ to the ydgN start codon to 3 bp 3′ to the ydgM start codon; probe 6, 866 nt, anneals from 907 bp 3′ to the ydgN start codon to 42 bp 3′ to the ydgN start codon; probe 7, 826 nt, anneals from 1687 bp 3′ to the ydgN start codon to 862 bp 3′ to the ydgN start codon. (B–E) Lanes 1 and 3 in (B), (D) and (E) and lane 1 in (C) show the full-length probe. Lanes 2 and 4 in (B), (D) and (E) and lane 2 in (C) show RPA results.

Figure 7.

Mapping of nth transcription initiation sites by primer extension analysis. (A) Arrows indicate primers used in primer extension analysis. nth20 anneals 88 bp 3′ to the predicted ydgL start codon; nth26 anneals 99 bp 3′ to the predicted ydgK start codon. (B) Primer extension with primer nth26. (C) Primer extension with primer nth20

The RPA with probe 2 resulted in a full-length product and products of 272 and 212 nt (Fig. 5B, lane 4). The full-length product corresponds to transcript read-through from ydgK into ydgL. An RPA was performed with probe 3 in order to determine if the less than full-length products were due to 5′ or 3′ probe digestion. This assay resulted in products of 750, 544 and 222 nt (Fig. 5C, lane 2). The 750 nt product corresponds to the initiation site upstream of ydgK. The 544 nt product resulted from 3′ probe digestion to the ydgK initiation site and 5′ probe digestion to a termination site, and indicates that the 272 nt product obtained with probe 2 was due to 5′ probe digestion. This shows that there was some transcript termination in the intergenic region between ydgK and ydgL. The 222 nt product obtained with probe 3 corresponds to the 212 nt product obtained with probe 2 and indicates that there is a transcription initiation site 5′ to the ydgL start codon. Primer extension analysis was performed with primer nth20 which was extended to a product of 110 nt (Fig. 7C), indicating there is an initiation site at a T residue 12 bp 5′ to the ydgL start codon. This site is separated by 3 nt from a possible –10 hexamer (TTTTTT) which is separated by 17 nt from a possible –35 hexamer (TGGATT).

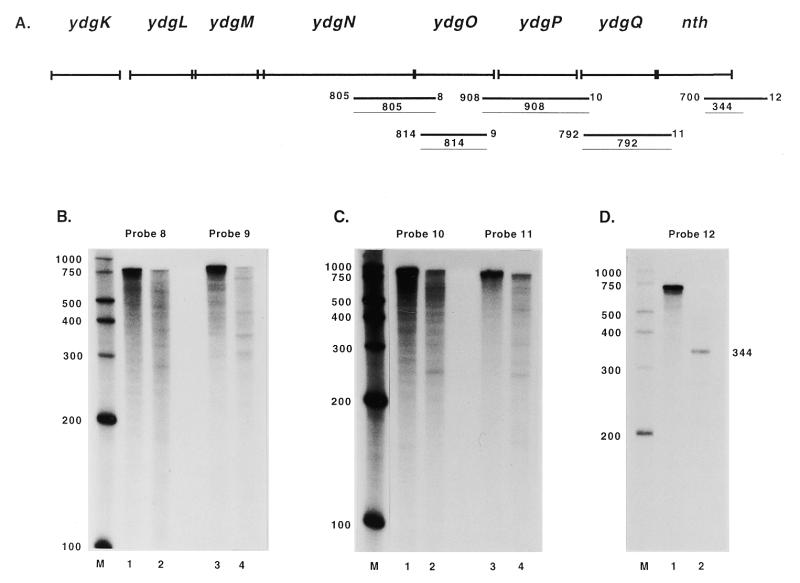

The RPAs with probes 4–11 all resulted in full-length products, confirming that the transcript extends from ydgK to nth (Fig. 5D, lanes 2 and 4, E, lanes 2 and 4, and Fig. 6B, lanes 2 and 4, and C, lanes 2 and 4). There is some smearing below the full-length product with probes 6–10. This is due to slight degradation of the RNA probe used in the RPAs (see Fig. 5E, lanes 1 and 3, and Fig. 6B, lanes 1 and 3, and C, lanes 1 and 3). The bands seen below full-length product with probes 9 and 10 disappear with RNase T1 digestion alone (data not shown), indicating that they are due to non-specific cleavage by RNase A. It was of particular interest to determine whether nth has its own promoter. The RPA with probe 11 showed some faint bands less than full length that could potentially correspond to a transcription initiation site, but when primer extension analysis was performed with several different primers (data not shown), it was not possible to detect an initiation site upstream of the nth start codon. When nth was originally sequenced it was reported to have a potential ribosome binding site, but no sequences similar to a consensus E.coli promoter were found preceding the gene (13).

Figure 6.

Mapping of the nth transcript by RPAs. (A) The thick lines designated 8–12 indicate the approximate annealing locations of the probes used in the RPAs. The thin lines indicate the products obtained from RPAs with these probes along with the sizes of the products. The sizes and exact annealing locations of the probes are as follows: probe 8, 805 nt, anneals from 207 bp 3′ to the ydgO start codon to 598 bp 5′ to the ydgN start codon; probe 9, 814 nt, anneals from 118 bp 5′ to the ydgP start codon to 132 bp 3′ to the ydgO start codon; probe 10, 908 nt, anneals from 80 bp 3′ to the ydgQ start codon to 204 bp 5′ to the ydgP start codon; probe 11, 792 nt, anneals from 97 bp 3′ to the nth start codon to 4 bp 3′ to the ydgQ start codon; probe 12, 700 nt, anneals from 372 bp 3′ to the nth stop codon to 328 bp 5′ to the nth stop codon. (B–D) Lanes 1 and 3 in (B) and (C) and lane 1 in (D) show the full-length probe. Lanes 2 and 4 in (B) and (C) and lane 2 in (D) show RPA results.

Probe 12 was used to map the terminator(s) of the operon and resulted in a product of 344 nt (Fig. 6D, lane 2). This transcript termination site corresponds to a C residue 16 bp 3′ to the nth stop codon. This residue is at the center of a predicted region of dyad symmetry capable of folding into a hairpin stem–loop structure which may act as a rho-dependent terminator (13).

These results confirm that nth is co-transcribed as the terminal gene in an eight gene operon. There are two transcription initiation sites, one upstream of the predicted ydgK start codon and one upstream of the predicted ydgL start codon, and there is a single transcript termination site downstream of the nth stop codon. In addition, there appears to be some transcript termination in the intergenic region between ydgK and ydgL.

The gene order of the operons is conserved or partially conserved in other organisms

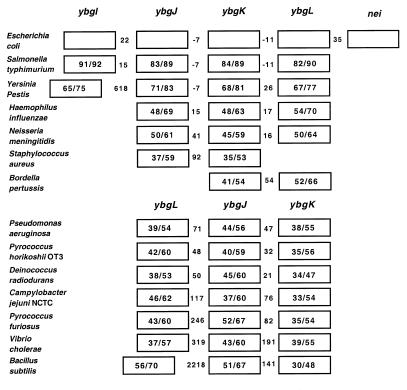

BLAST searches were performed with the finished and unfinished genome databases at the NCBI Website using the E.coli amino acid sequences for the products of each gene in both operons. The searches using the amino acid sequences for the products of the genes in the nei operon showed that there is only one obvious endo VIII homolog, in Salmonella typhimurium, but that it is not in the same location as in the E.coli genome. In S.typhimurium, the homologs of ybgI–ybgL are located together but nei is not next to ybgL (Fig. 8). It has also been suggested that there is an endo VIII homolog in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (14), but the order of genes surrounding the possible homolog is not the same as in E.coli. ybgJ, ybgK and ybgL have been well conserved in other organisms, either in the same order as in the nei operon or in the order ybgL, ybgJ, ybgK, although it is not known whether they are also transcribed together in the other organisms. This suggests that there could be some regulatory or functional significance for these genes being grouped together, since this grouping is found in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and also in Archea. These ORFs encode unknown proteins but the products of ybgJ and ybgK are putative carboxylases and the product of ybgL is a putative lactam utilization protein as reported in GenBank accession no. AE000174. In E.coli it appears that nei was arbitrarily tacked onto the end of these genes making it seem unlikely that there is a regulatory or functional significance for nei being the last gene in this operon. However, since nei does not appear to have its own promoter, at least under the growth conditions used, it is under the regulatory control of the two upstream promoters.

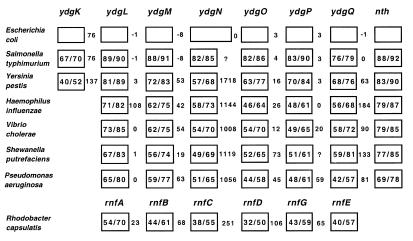

Figure 8.

Conservation of gene arrangement for the nei operon. The numbers in the boxes are percent identity/percent similarity of the proteins relative to the E.coli proteins. The numbers between the boxes represent the number of base pairs in the intergenic regions; negative numbers indicate that the ORFs overlap.

The searches using the amino acid sequences for the products of the genes in the nth operon showed that the gene order of the operon has been completely conserved in S.typhimurium and Yersinia pestis and that the order of ydgL through nth has been conserved in at least four other Gram-negative organisms (Fig. 9). The functions of the proteins encoded by the ORFs is unknown, but ydgL through ydgQ show homology to the genes rnfA, rnfB, rnfC, rnfD, rnfG and rnfE of Rhodobacter capsulatis, a purple non-sulfur photosynthetic bacterium. Rnf stands for Rhodobacter nitrogen fixation and these genes are required for nitrogen fixation (15). These genes, along with a seventh gene, rnfH, make up a seven gene operon under the control of a σ54 promoter (15). In E.coli and in the other bacteria shown in Figure 9, rnfH has been replaced by nth. It has been proposed that the Rnf proteins form a membrane complex that functions as an intermediate in electron transport to nitrogenase (15), but it is unclear whether RnfH is part of this complex (16). RnfA, RnfD and RnfE are predicted on the basis of hydrophobicity to be integral membrane proteins (15) and RnfA has been shown to have six membrane-spanning hydrophobic segments (17). RnfB and RnfC are [Fe-S]-containing proteins that are tightly bound to the membrane (16,17) and RnfC is predicted to contain potential NAD(H) and FMN binding sites which are similar to those found in proton-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductases (17). RnfG and RnfH are predicted to be largely soluble proteins (15). Since E.coli and the other organisms that have homologs to the rnf genes do not fix nitrogen, it has been predicted that these genes represent a new family of energy coupling NADH oxidoreductases that are distributed in a wide range of bacteria (17). If the terminal electron acceptor in this system is oxygen, it might make sense that nth is transcribed with these genes since partially reduced oxygen species that escape can cause the types of DNA damage that endo III repairs. However, it has been speculated that the electron acceptor may be ferrodoxin, as is thought to be the case with the Rnf complex (17).

Figure 9.

Conservation of gene arrangement for the nth operon. Question marks indicate that it was not possible to determine the number of base pairs in the intergenic region.

Studies are currently underway to examine the regulation of these operons. It has recently been shown that the genes for two other oxidative base excision repair DNA glycosylases, fpg and mutY, are also co-transcribed as part of operons (11). fpg is the last gene in a four gene operon with internal promoters and a strong attenuator between fpg and the upstream genes. fpg has its own promoter which appears to be weakly expressed during aerobic growth in LB broth. mutY is the first gene in a four gene operon with internal promoters and multiple attenuators. In contrast, nei and nth are part of simpler operons. Neither gene appears to have an independent promoter under the growth conditions used in this study, although nei has a putative promoter consensus sequence upstream of its start codon which could potentially be used under stress conditions.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R37 CA33657 awarded by the National Cancer Institute. C.M.G. was supported by Environmental Pathology training grant T32 07122 awarded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The authors are grateful for helpful discussions with Richard Cunningham.

REFERENCES

- 1.Evans J., Maccabee,M., Hatahet,Z., Courcelle,J., Bockrath,R., Ide,H. and Wallace,S. (1993) Mutat. Res., 299, 147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace S.S. (1994) Int. J. Radiat. Biol., 66, 579–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang D., Hatahet,Z., Blaisdell,J.O., Melamede,R.J. and Wallace,S.S. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 3773–3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace S.S., Harrison,L., Jiang,D., Blaisdell,J.O., Purmal,A.A. and Hatahet,Z. (1998) In Dizdaroglu,M. and Karakaya,A.E. (eds), Advances in DNA Damage and Repair. Plenum Press, New York, NY, pp. 419–430.

- 5.Saito Y., Uraki,F., Nakajima,S., Asaeda,A., Ono,K., Kubo,K. and Yamamoto,K. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 3783–3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purmal A.A., Kow,Y.W. and Wallace,S.S. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 72–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feig D.I., Sowers,L.C. and Loeb,L.A. (1994) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 6609–6613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreutzer D.A. and Essigmann,J.M. (1998) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 3578–3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaisdell J.O., Hatahet,Z. and Wallace,S.S. (1999) J. Bacteriol., 181, 6396–6402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melamede R.J., Hatahet,Z., Kow,Y.W., Ide,H. and Wallace,S.S. (1994) Biochemistry, 33, 1255–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gifford C.M. and Wallace,S.S. (1999) J. Bacteriol., 181, 4223–4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudd K.E. (1998) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 62, 985–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asahara H., Wistort,P.M., Bank,J.F., Bakerian,R.H. and Cunningham,R.P. (1989) Biochemistry, 28, 4444–4449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizrahi V. and Andersen,S.J. (1998) Mol. Microbiol., 29, 1331–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmehl M., Jahn,A., Meyer zu Vilsendorf,A., Hennecke,S., Masepohl,B., Schuppler,M., Marxer,M., Oelze,J. and Klipp,W. (1993) Mol. Gen. Genet., 241, 602–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jouanneau Y., Jeong,H.S., Hugo,N., Meyer,C. and Willison,J.C. (1998) Eur. J. Biochem., 251, 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumagai H., Fujiwara,T., Matsubara,H. and Saeki,K. (1997) Biochemistry, 36, 5509–5521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]