Abstract

Cancer has been one of the major healthcare burdens, which demands innovative therapeutic strategies to improve the treatment outcomes. Combination therapy hold great potential to leverage multiple synergistic pathways to improve cancer treatment. Cancer cells often exhibit an increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant species compared with normal cells, and the levels of these species can be further elevated by common therapeutic modalities such as photodynamic therapy (PDT) or chemotherapy. Taking advantage that cancer cells are vulnerable to further oxidative stress, we aim to design a drug delivery system by simultaneously increasing the cellular ROS level, reducing antioxidative capacity, and inducing anticancer chemotherapy in cancer cells. Here, we designed a star-shape polymer, PEG(-b-PCL-Ce6)-b-PBEMA, based on the Passerini three-component reaction, which can both enhance ROS generation during PDT and decrease the GSH level in cancer cells. The polycaprolactone conjugated with photosensitizer Ce6 served as hydrophobic segments to promote micelle formation, and Ce6 was used for PDT. The H2O2-labile group of arylboronic esters pendent on the third segment was designed for H2O2-induced quinone methide (QM) release for GSH depletion. We thoroughly investigated the spectral properties of blank micelle during its assembling process, ROS generation, and H2O2-induced QM release in vitro. Moreover, this polymeric micelle could successfully load hydrophobic anticancer drug Doxorubicin (DOX) and efficiently deliver DOX into cancer cells. The triple combination of ROS generation, GSH elimination, and chemotherapy dramatically improved antitumor efficiency relative to each of them alone in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: Combination cancer therapy, Polymeric micelle, Arylboronic esters, GSH depletion, Photodynamic therapy

1. Introduction

The normality of cellular redox homeostasis is maintained by the intrinsic cell machinery. The dynamic homeostasis of oxidation-reduction is sophisticatedly regulated in cells. On one hand, ROS is generated by cells at a normal level to increase cell differentiation and proliferation [1,2], which plays vital roles in many biological functions, including modulation of inflammation and clearance of foreign pathogens and materials [3]; on the other hand, cells are equipped with antioxidant systems to eliminate ROS and maintain redox homeostasis, such as catalase, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione (GSH) et al. [4]. Such homeostasis is very important to counteract the detrimental effects of excessive ROS [1]. Disruption of this homeostasis often leads to disease development. For example, cancer cells often have excessive oxidative stress due to redox balance dysfunction [5], which promotes cancer cell proliferation, tumor growth, and metastasis, even arouse the resistance to chemotherapy [6]. This will in turn lead to the upregulation of antioxidant systems for tumor cell to counteract the accumulation of ROS [7]. The redox adaptation response may shift the redox dynamics with high ROS generation and elimination to maintain the ROS levels below the toxic threshold [5]. Therefore, cancer cells often exhibit an increased generation of ROS and antioxidant species compared with normal cells, which are widely used in many tumor responsive drug delivery systems [8-10].

For cancer therapy, the intracellular ROS generation has been modulated by a variety of approaches such as radiotherapy, PDT, Fenton-based or ferroptosis mechanisms [11]. Among these approaches, PDT is widely used to directly kill cancer cells with spatiotemporal specificity and minimal invasiveness. However, due to limited light penetration and hypoxia condition in tumor sites [12], the efficiency of PDT has been limited. As discussed above, cancer cells have become highly adapted to intrinsic oxidative stress with upregulated antioxidant capacity [5,13], which limits ROS production, especially in the deep tissue and many necrotic and hypoxic tumor tissues. Alternatively, for inhibition of antioxidant systems, depletion of GSH has been an interesting option among various endogenous antioxidants, since GSH is the major ROS-scavenging system in cells [14,15]. There are three common strategies that have been explored to reduce GSH level in tumor cells. First of all, buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) for example can target the GSH synthesis pathway and inhibit the synthesis of γ-glutamylcysteine [16], which is a rate-limiting enzyme for GSH synthesis. Another strategy is converting GSH to glutathione disulfide (GSSG) by oxidizers via redox reactions, such as some polyvalent metallic elements [17-20]. However, many metallic nanoparticles have poor colloidal stability and biocompatibility [21], which may affect their biomedical applications. Beyond the first two strategies, GSH depletion can be achieved by reacting with GSH through chemical reaction. Compounds such as some isothiocyanates [22], aziridine derivatives [23], quinone methide (QM) [16,24-26], or double bonds of acrylates [27] can rapidly conjugate with GSH through electrophile-nucleophile interactions. Many of these groups can be easily integrated into polymeric biomaterials for anticancer drug delivery. Most polymeric drug delivery systems are biocompatible, degradable, and possible to be functionalized to achieve a localized and sustained drug release [28]. Thus, elaborately designed polymers are an ideal choice to fulfill GSH depletion.

Since cancer cells are dependent on the antioxidant system and vulnerable to additional oxidative stress induced by exogenous ROS-generating or inhibit of antioxidant system [13], simultaneously increasing the cellular ROS level and reducing antioxidative capacity hold the potential to destroy redox homeostasis to promote tumor growth inhibition. Here, we designed a star-shape polymer ((PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA) that can both enhance ROS generation during PDT and in situ decrease the level of GSH in cancer cells (Scheme 1). The GSH depletion strategy was induced to make up for the shortcomings of PDT to reach the “threshold concept” of oxidative stress for cancer therapy. This polymer was synthesize based on the Passerini three-component reaction. The polycaprolactone (PCL) conjugated with Ce6 served as hydrophobic segments to promote micelle formation and fulfills PDT under light irradiation. The H2O2-labile group of arylboronic esters pendent on the third segment was designed for H2O2-indeced QM release to deplete GSH. We thoroughly investigated the spectral properties of blank micelle for its assembling process, ROS generation, and H2O2-induced QM release in vitro. This polymeric micelle could successfully load hydrophobic anti-cancer drug Doxorubicin (DOX) and efficiently deliver DOX into cancer cells. The ROS generation under light irradiation and GSH elimination combined with chemotherapy strategy displayed improved antitumor efficiency over DOX both in vitro and in vivo.

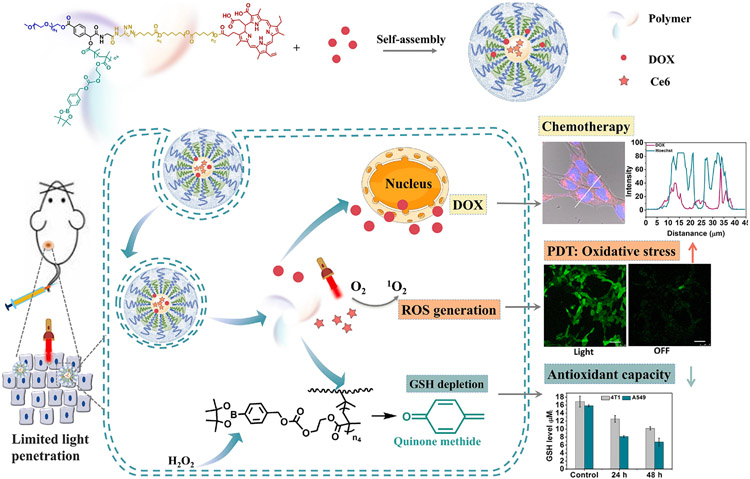

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of polymeric micelles for triple combination cancer therapy, in which DOX was used for cancer chemotherapy, and Ce6 was used for PDT. Together, PDT and glutathione depletion elevated the tumor oxidative stresses.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials and instruments

N,N-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), 4-dimethylamino-pyridine (DMAP), methoxy poly(ethylene glycol) (mPEG, Mw = 2000 g/mol) and ROS probe 9,10-anthracenediylbis- (methylene)dimalonic acid (ABDA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. Doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX·HCl) was obtained from Yingxuan Chempharm (Shanghai, China) and was deprotonated according to the method previously reported [29]. Chlorin e6 (Ce6) was purchased from J&K Chemical (Shanghai, China). Propargylamine and N,N,N′, N″, N″-Pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA) were purchased from TCI (Shanghai, China). 4-(Hydroxymethyl)phenylboronic acid pinacol ester and 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate were purchased from Adamas (Shanghai, China). N,N-Carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) and isocyanoacetic acid methyl ester were purchased from Energy Chemical. Triethylamine (TEA) was purchased from Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent. 2-Bromo-2-methylpropionic acid were purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). P-Toluenesulfonyl chloride (PTSC) and 4-Formylbenzoic acid were purchased from best-reagent (Chengdu, China). N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) and dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) were purchased from Kelong Chemical (Chengdu, China) and were purified before use. All the other solvents were purchased from Kelong Chemical (Chengdu, China) and used without further purification. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Shanghai Basal Media Technologies. [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)- 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] (MTT) was purchased from Energy Chemical Co. (Shanghai, China). 2′,7′-dichlorfluorescein-diacetate (DCFH-DA) and GSH and GSSG Assay Kit were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China).

The 1H NMR measurement was performed on an NMR spectrometer (Varian, 400 MHz). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS10 spectrophotometer. The particle size in solution was performed on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (UK) at room temperature, and the morphology of the micelles was observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM, S-4800, HITACHI). Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms were obtained on a TA Q2000 with the heating rate of 10 °C/min. UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy was performed on a Specord200 PLUS UV–Vis spectrophotometer. Fluorescence spectra were obtained on a spectrophotometer (F-7000, Hitachi, Japan).

2.2. Synthesis of star shape polymer PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA

2.2.1. Synthesis of PEG(-alkynyl)-Br

We first modified mPEG by reacting mPEG (3.00 g) with 4-Formylbenzoic acid (0.338 g) at the prescribed amounts of DCC (0.618 g) and DMAP (18.3 mg) in anhydrous DMF at an ice bath under nitrogen atmosphere. The mixture was magnetically stirred for 48 h. After that, white precipitate was filtrated, and the filtrate was condensed in dichloromethane and precipitated in a large amount of diethyl ether. This process was repeated at least 3 times. The white powder was vacuum-dried at room temperature to abstain PEG-CHO. Then we synthesis of propargyl isocyanoacetamide as a method described by Lei Li [30]. A mixture of propargylamine (0.279 g) and isocyanoacetic acid methyl ester (0.500 g) was stirred at room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was dissolved in THF and precipitated in cold diethyl ether for three times. The product was dried under vacuum overnight to give propargyl isocyanoacetamide. The synthesis of PEG(-alkynyl)-Br was adapted from the method described by Lei Li [30]. A mixture of PEG-CHO (1.00 g), 2-bromo-2-methylpropionic acid (0.417 g), and propargyl isocyanoacetamide (0.305 g) were mixed in THF and stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The mixture was evaporated to dryness on a rotary evaporator, then dissolved in 0.5 M aqueous HCl solution to remove the excess propargyl isocyanoacetamide. The aqueous solution was extracted with dichloromethane for at least 3 times. The combined organic phase was dried with anhydrous Mg2SO4, and filtrated, condensed at reduced pressure. Then the product was precipitated into a large amount of diethyl ether. The little brown powder after vacuum dryness was obtained as PEG(-alkynyl)-Br.

2.2.2. Synthesis of PEG(-alkynyl)-b-PBEMA

We first synthesized monomer BEMA through a method described by Zhang [31]. 4-(hydroxymethyl)phenylboronic acid pinacol ester (2.50 g) and CDI (3.00 g) were dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane under nitrogen atmosphere. The mixture was magnetically stirred at 40 °C and using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) to monitor the reaction progress. After the reaction was completed, the reaction mixture was dissolved in dichloromethane and washed by water for at least 3 times; then the organic phase was dried with anhydrous Mg2SO4, filtrated and dried under vacuum to give the CDI-activated phenylboronic acid pinacol ester. The CDI-activated product (3.40 g), HEMA (1.39 g), and DMAP (1.56 g) were dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane and reacted at 40 °C using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) to monitor the reaction progress. After the reaction was completed, the reaction mixture was condensed under reduced pressure. The BEMA monomer was obtained as a white solid by chromatography eluting with CH2Cl2/EtOAc (9:1). A mixture of PEG(-alkynyl)-Br (0.500 g), BEMA (1.07 g), and PMDETA (0.433 g) were dissolved in THF. After 3 times of freeze–pumpthaw cycles, CuBr (0.358 g) was introduced quickly into this reaction mixture under nitrogen atmosphere. The mixture was placed in an oil bath at 40 °C overnight. The polymerization was quenched by adding extra amount of THF and stirred by exposing it in the air. The solution was passed through an Al2O3 column and evaporated to dryness under vacuum. The residue was diluted with THF and precipitated in excess of diethyl ether for three times. PEG(-alkynyl)-b-PBEMA was obtained after vacuum drying.

2.2.3. Synthesis of N3-PCL-Ce6

The polymer HO-PCL-OH was synthesized by our lab just as the formerly published paper [32]. The molecular weight was about 1000 g/mol, which was calculated through NMR. HO-PCL-OH (2.00 g), PTSC (0.419 g) were dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane at an ice bath under nitrogen atmosphere. TEA (0.223 g) was dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane and was dropped into that mixture. The mixture was magnetically stirred at room temperature for 48 h. The mixture was diluted in dichloromethane and washed by 0.5 M HCl for 3 times, then washed by saturated NaCl for 3 times. The combined organic phase was dried with anhydrous Mg2SO4, and filtrated, condensed at reduced pressure. The white powder was obtained as TsCl-PCL-OH after vacuum dryness. All the TsCl-PCL-OH was then dissolved in DMF, and NaN3 (1.30 g) was carefully added to the solution. The reaction was put into an oil bath at 40 °C for 48 h. After that, the solution was condensed under reduced pressure and was diluted with dichloromethane. The organic phase was washed by water for 3 times, dried with anhydrous Mg2SO4, filtrated, and dried under vacuum dryness. The white powder turned to be N3-PCL-OH. Then N3-PCL-OH (0.500 g) was reacted with Ce6 (0.298 g) through DCC and DMAP just as the method we had described above. Then we can get the polymer of N3-PCL-Ce6.

2.2.4. Synthesis of star shape PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA

We get the final product through click reaction. PEG(-alkynyl)-b-PBEMA (0.680 g), N3-PCL-Ce6 (0.231 g), and PMDETA (88.0 mg) were dissolved in anhydrous DMF. After 3 times of freeze-pump-thaw cycle, CuBr (73.0 mg) was added quickly into the mixture under the protection of nitrogen. The click reaction was carried out at 60 °C for 24 h. The reaction was diluted with THF and stirred in the air for stopping. The mixture was passed through an Al2O3 column to remove the copper catalyst. The solution was condensed under reduced pressure and precipitated into diethyl ether. After vacuum drying overnight, PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA was obtained as a little brown solid.

2.3. Micelle preparation and characterization

2.3.1. Blank micelle preparation

The amphiphilic polymer PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA can self-assemble into blank micelle by the cosolvent evaporation method. In brief, 5.00 mg PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA was dissolved in THF; then the organic phase was dropped into 10 mL DI water under magnetic stir until THF was fully evaporated. Subsequently, the solutions were filtered by 0.45 μM filters to remove the undissolved substance. The size and morphology of the micelles were characterized by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and SEM. The polymeric micelles are also prepared in PBS containing 10% FBS to examine the colloidal stability. The fluorescence spectra and UV–Vis absorption spectra were measured with different micelle concentration from 0.5 mg/mL with a two-fold serial dilution.

2.3.2. H2O2 responsiveness and QM release

We use 1H NMR analysis and fluorescence spectra to evaluate H2O2-induced QM release. We prepared blank micelles with a concentration of 0.125 mg/mL and incubated them with 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, or 100 mM H2O2 at 37 °C for different time points. The fluorescence spectra were recorded to reveal the influence of Ce6 fluorescence during the change of micelle architecture. The amount of 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol (HA) release was also determined by 1H NMR analysis.

2.3.3. DOX loaded micelle and drug release

For the preparation of DOX loaded micelles, the amphiphilic polymer (PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA, 20 mg) and DOX (5 mg) were dissolved in 1 mL of DMSO. The mixture was ultrasonicated to obtain a homogeneous solution. Then the organic phase was dropped into 20 mL deionized water with vigorous stirring. The solution was then transferred to a dialysis tubing (Spectra/Por MWCO = 2000) and dialyzed against deionized water for 18 h. The outer phase was replaced with fresh deionized water every 4 h until the organic solvent was eliminated. The drug loaded solution was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min to remove any unloaded DOX. The loading solution was lyophilized, and the whole procedure was performed in the dark. The content of encapsulated DOX was determined by fluorescence measurement (maximum emission wavelength at 550 nm) with the calibration curve of DOX-DMSO solution. Drug loading content (DLC) and drug loading efficiency (DLE) were calculated according to the following equation: DLC (wt (the amount of DOX in the nanocarriers)/(the amount of DOX-loaded nanocarriers) × 100%; DLE (wt%) = (the amount of DOX in the nanocarriers)/(the amount of DOX feeding) × 100%. DOX-loaded micelles were dispersed in buffer solutions with different pH values (pH 7.4 and 5.0; ionic strength = 0.01 M) and 50 mM H2O2. Then 1 mL drug loading solution was transferred into dialysis tubes (MWCO 1000) and was immersed in vials containing 25 mL buffer solutions. The vials were put in a shaking bed at 37 °C with a shaking rate of 150 rpm. At designated time intervals, 1 mL medium with the released drug was taken out for fluorescence measurement, and the same volume of fresh medium was added into the vials. The released DOX was detected by a fluorescence detector with an excitation wavelength at 480 nm and emission wavelength at 550 nm.

2.4. Cells

Mice breast cancer cells 4T1 and adenocarcinomic human alveolar basal epithelial cells A549 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media, NIH 3T3 was cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

2.4.1. Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of blank micelle toward cancer and normal cells was tested by MTT assay. The cytotoxicity of blank micelle was tested on NIH 3T3 cells. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (3 × 103 cells per well), which were incubated with the blank micelles at different concentrations for 48 h, and the relative cell viability was tested by MTT assay. For the phototoxicity of blank micelles, 4T1 and A549 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (3 × 103 cells per well), which were incubated with the blank micelles at different concentrations for 24 h. The cells were then treated with a 660 nm LED light (50 mW/cm2) for 5 and 10 min, using no light irradiation as control. After incubation for another 24 h, the relative cell viability was tested by MTT assay. The cytotoxicity of drug-loaded micelles was tested similarly.

2.4.2. Live/dead assay of PDT treatment

Imaging of the PDT cytotoxicity was carried out through a calcein-AM/PI staining method. 4 T1 or A549 cells were treated with blank micelles of 100 μg/mL and illuminated with the 660 nm LED light (50 mW/cm2) for 0, 5, and 10 min. With further incubation of 4 h, cells were stained with calcein-AM/PI for 15 min. Then wash twice with PBS and were immediately recorded for image.

2.4.3. ROS generation in vitro

Laser-irradiation-induced ROS generation in 4T1 and A549 cells was detected using reactive oxygen species assay kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. To visualize ROS generation in vitro, 4T1 or A549 cells seeded in glass dishes at a cell density of 104 cells per mL and then incubated with blank micelle at designed concentration. The cell culture medium was removed after 4 h incubation, and fluorescent probe DCFH-DA was added. Twenty minutes later, cells were irradiated with a 660 nm light irradiation for 5 min by using no light irradiation as control and then examined through CLSM. For flow cytometry samples, cells were treated by a similar procedure on a 6-well plate and suspended in PBS cells for quantitative analysis.

2.4.4. GSH depletion

4T1, A549, and NIH/3T3 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. After 24 h incubation, the medium was replaced with medium containing blank micelle solution at a final concentration of 100 μg/mL. Cells were incubated for 24 h or 48 h and then collected for GSH testing using GSH and GSSG assay kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells without any treatment were used as control.

2.4.5. Cellular uptake of drug loaded micelles

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and flow cytometry were used to evaluate the cellular internalization efficiency of drug loaded micelles. 4T1 or A549 cells were cultured on glass dishes at a cell density of 104 cells per mL. Then, free DOX or DOX-loaded micelles (10 μg/mL) was added after incubation for different time points. The medium in the well was removed, and the dishes were washed with PBS several times. After that, the cells were observed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. A similar procedure was conducted for flow cytometry on a 6-well plate and harvested the cells for quantitative analysis.

2.4.6. In vitro anticancer activity of drug loaded micelles

4T1 or A549 cells were harvested and seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. After 24 h incubation, the medium was replaced with fresh culture medium containing DOX-loaded micelles with different DOX concentrations and incubated for 48 h. The culture medium was removed, and the relative cell viability was tested by MTT assay.

2.4.7. Detection of calreticulin (CRT) expression

The expression of CRT on the cell membrane after PDT was assessed by flow cytometry. 4T1 cells were seeded into 48-well plates. 24 h later, the cell culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing blank micelles at a concentration of 100 μg/mL. After 24 h incubation, cells were irradiated for different time and further incubated for 4 h. Then cells were collected and washed with PBS twice and stained with Zombie UV (BioLegend) for 10 min. After washing with PBS containing 0.1% FBS for once, cells were incubated with calreticulin antibody (Abcam) for 30 min. Finally, the cells were washed with PBS twice and examined by flow cytometry (BD LSRFortessa). The fluorescence intensity of CRT-stained cells was gated on Zombie UV-negative and CTR-positive cells.

2.5. Animals

Permission for the animal experiments was obtained from the ethics committee of Sichuan University. All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the Animal Management Rules of the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China and the institutional guidelines.

2.5.1. In vivo fluorescence imaging

This animal study was conducted following NIH guidelines and in accordance with an approved protocol by the Virginia Commonwealth University Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Female C57BL/6 mice (6 weeks) were purchased from the Charles Rivers.

Approximately 5 × 105 4T1 cells suspended in PBS (50 μL) were subcutaneously injected into the right flank of the BALB/c mice. Tumor volumes were calculated by the formula: V [mm3] = 1/2×(L × W2), where L and W represent the length and width of the tumor tissue. 1,1-dioctadecyl-3,3,3,3-tetramethylindotricarbocyanineiodide (DIR) was used as a fluorescence probe loaded into the polymeric micelles. When the tumor volume reached about 200 mm3, the mice were randomly divided into three groups: (i) PBS, (ii) Free DIR, (iii) Polymer/DIR. PBS or micelle solution was intravenously injected into tumor-bearing mice at an identical DIR dose of 5.0 mg/kg. The whole body fluorescence images were taken at 2, 4, 6, 10, 24, 54, and 76 h using an IVIS imaging system (PerkinElmer, USA). After taking images, the mice were sacrificed, and all major organs and tumors were collected and examined for fluorescence imaging ex vivo. The fluorescence intensity was calculated by Radiant efficiency through the software.

2.5.2. Pharmacokinetics

Six-week-old male BALB/c mice were purchased from Chengdu Dashuo Biological Technology Company. To investigate the pharmacokinetics of the drug-loaded micelle, the mice were randomly divided into two groups (n = 3). Each group was intravenously injected with 0.2 mL free DOX or DOX-loaded micelles solution in saline with an identical DOX concentration of 10 mg/kg. Blood samples were collected from the orbital venous plexus with a heparinized tube at 3 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, and 12 h post-administration. The supernatant of the blood samples was collected by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and 100 μL plasma was taken out and extracted with 0.5 mL of chloroform/isopropanol (4:1, V/V) by vortex mixing for 120 s. After centrifugation at 10, 000 rpm for 3 min at 4 °C, the organic phase was separated and dried under nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature. The residue was dissolved in 1 mL of DMSO, and the content of DOX in the supernatant was determined using fluorescence measurement.

2.5.3. In vivo anticancer activity

We use 4T1 cancer cells as tumor model. Approximately 5 × 105 4T1 cells suspended in PBS (50 μL) were subcutaneously injected into the right flank of the BALB/c mice. When the inoculated tumor volume reached 100–200 mm3, the mice were randomly divided into seven groups and treated with: (i) saline, (ii) DOX, (iii) Polymer, (iv) DOX/Polymer, (v) DOX + L, (vi) Polymer + L, and (vii) DOX/Polymer + L, here L means treatment with light irradiation. The mice were injected intravenously via the tail vein with a DOX dose of 5 mg/kg. The light irradiation used for PDT was conducted by 660 nm LED light (50 mW/cm2 for 10 min). All samples were injected four times at 3-day intervals, and the tumor regions were exposed to the light irradiation 6 h after injection. Animal death was recorded when the tumor volume reached 2000 mm3. After 24 days, the mice in all groups were randomly picked out and sacrificed. Major organs were taken out, fixed in 4% formaldehyde, processed routinely into paraffin, sectioned, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), tunnel, and immunohistochemical analysis (CD34 and Ki-67) staining and examined using a digital microscope.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All data obtained were presented as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). Furthermore, Student’s t test was engaged to analyze the difference between the study groups. Statistical significance was set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The synthesis and characterization of copolymer PEG(-b-PCL-Ce6)-b-PBEMA

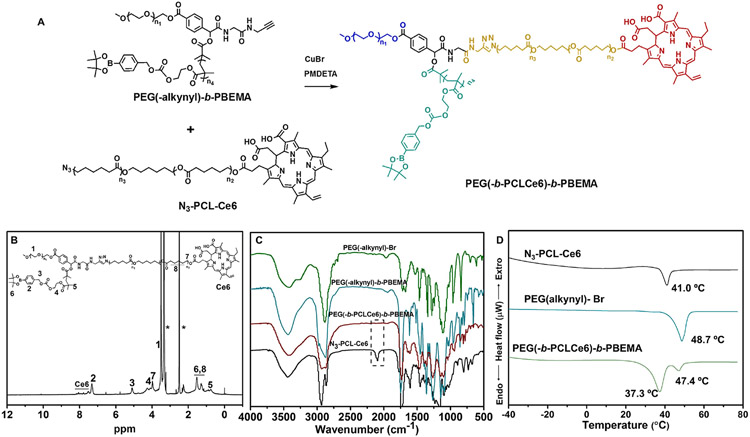

We designed and synthesized a star-shape polymer PEG(-b-PCL-Ce6)-b-PBEMA. In this copolymer, the arms of PBEMA and PCL are connected to the end of the PEG chain through ATRP and click chemistry, respectively. Thus, it is crucial to prepare a dual end-functionalized PEG(-alkynyl)-Br (Fig. S1), which was easily obtained from PEG-CHO via Passerini three-component reaction with 2-bromo-2 methylpropionic acid and propargyl isocyanoacetamide according to other’s papers [30]. The PEG(-alkynyl)-Br was used as a macroinitiator to polymerize BEMA through ATRP polymerization. The average degrees of polymerization (DP) were calculated by comparing the integration of the methylene peak (δ = 5.1 ppm) from arylboronic esters to the integration of the methyl peak (δ = 3.3 ppm) from PEG (Fig. S6). The polymer HO-PCL-OH was synthesized by our lab just as the formerly published paper [32]. After modification, the third chain containing Ce6 (N3-PCL-Ce6) for PDT was connected to PEG(-alkynyl)-PBEMA by click chemistry. All the compounds in the synthesis route were confirmed by NMR (Figs. S2-S7). The final product of PEG(-b-PCL-Ce6)-b-PBEMA was verified by NMR and FTIR (Fig. 1B and C), in which the characteristic peak at 2100 cm−1 from azide stretching vibration was disappeared after the click reaction, suggesting the polymer was successfully synthesized. The molecular weights of these polymers were measured by GPC and calculated by 1H NMR (Table S1). We used DSC to test the thermal properties of these polymers (Fig. 1D). The polymer N3-PCL-Ce6 and PEG(-alkynyl)-Br showed a melting transition at 41.0 °C and 48.7 °C respectively, indicating the typical crystallization peak of PCL and PEG. In the final product of PEG(-b-PCL-Ce6)-b-PBEM, there appeared two melting peaks, which were much lower than that of N3-PCL-Ce6 and PEG(-alkynyl)-Br, suggesting the introducing of PBEMA block induced the steric hindrance and disturbed the chain packing of PCL and PEG.

Fig. 1.

The synthesis and characterization of the star shape PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA. (A) The last step for PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA synthesis. 1H NMR spectrum of PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA in DMSO-d6 (B) and FTIR spectra (C) of the synthesized materials. (D) DSC results of N3-PCL-Ce6, PEG(-alkynyl)-Br, and PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA.

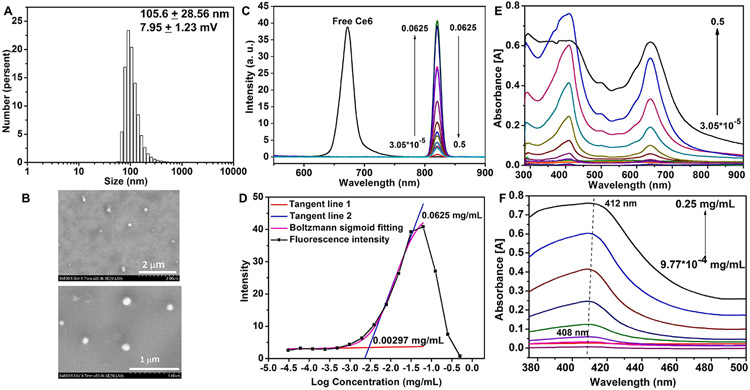

The amphiphilic block copolymer self-assembled into micelles in water using a cosolvent evaporation method. As shown in Fig. 2A, the blank micelle has a narrow size distribution around 105.6 nm and a slightly positive zeta potential (7.95 ± 1.23 mV). Fig. 2B showed the morphology of the blank micelles. We also investigated micelle’s colloidal stability (0.1 mg/mL) in PBS solution containing 10% FBS (Fig. S8). The micelles were stable with no visible aggregation within a week. The size was smaller, and the PDI was larger in PBS containing 10% FBS than in water. This was probably because serum components could strongly scatter the light, and serum proteins alone have a size distribution at the low nanometer range in diameter (data not shown) [33], which might impact the micelle size detection. We measured the fluorescence spectra and UV–Vis absorption spectra of different micelle concentration from 0.5 mg/mL with a two-fold serial dilution. Comparing with free Ce6 in DMSO having an emission peak around 673 nm, the emission peak of polymeric micelles was strongly red shifted (~820 nm) due to π-π stacking interaction of the hydrophobic aromatic ring. When the concentration below 0.0625 mg/mL, the fluorescence intensity was gradually increased along with the increasing of micelle concentration; when the concentration was high than 0.0625 mg/mL, the fluorescence intensity decreased sharply due to fluorescence quenching. The fluorescence intensity along with micelle concentration was shown in Fig. 2C. To measure the critical aggregation concentration (CAC) of nanoparticles [34], we took advantage of the fluorogenicity of Ce6 and used Ce6 as an internal probe. The polymer had a small CAC as 2.97 μg/mL (Fig. 2D). The Ce6 absorption was gradually increased with increasing micelle concentrations. As shown in Fig. 2E, the absorption peak showed a slightly red shift (Fig. 2F) due to J-aggregation of the hydrophobic aromatic ring arising from π-π stacking, which was also reported in other literatures [35,36].

Fig. 2.

Self-assembly of polymer PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA. (A, B) Size distribution by DLS (A) and SEM image (B) of blank polymer self-assembled micelles. (C, D) Fluorescence emission spectrum of different micelle concentration (C) and maximum fluorescence intensity for CAC measurement (D). (E, F) UV–Vis absorption spectrum of different micelle concentrations (E) and maximum absorbance wavelength from 375 nm to 500 nm (F).

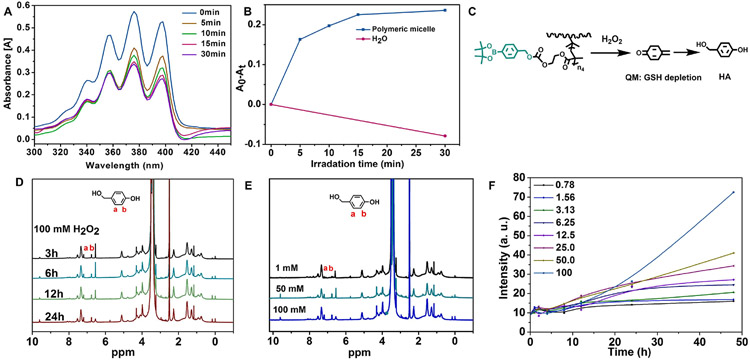

3.2. ROS generation and H2O2 induced QM release from polymeric micelles

The ROS probe ABDA was used as a ROS indicator to measure ROS concentration. The ABDA consumption was monitored by measuring the UV–Vis spectra of ABDA (Fig. 3A). Upon illumination with 660 nm irradiation of blank polymeric micelles (0.0625 mg/mL), the generation of ROS decreased the absorption of ABDA (Fig. 3B), suggesting that blank micelles were potent for photoactivity.

Fig. 3.

Characterization of ROS generation and H2O2 induced QM release of the polymeric micelles. The UV–Vis spectra of ABDA probe (A) and the (A0–At) absorption at 376 nm (B) for ROS generation of blank polymeric micelles (0.0625 mg/mL) upon 660 nm irradiation. (C) H2O2-responsive QM release and HA formation from PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA micelle. (D) 1H NMR spectra recorded the formation of HA from released QM at different time points when micelles were incubated with 100 mM of H2O2. (E) Comparison of 1H NMR spectrum for HA from released QM after incubation for 24 h in the presence of different H2O2 concentrations. (F) Time-dependent fluorescence intensity of PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA micelles incubated at different H2O2 concentrations.

Arylboronic esters have been comprehensively investigated as ROS-labile groups [37,38]. Here, we evaluated H2O2-induced QM release through 1H NMR. Because QM can be converted into 4-hydroxybenzyl alcohol (HA) rapidly in aqueous solution in the absence of nucleophiles (Fig. 3C) [39]. We analyzed HA production at 1 Mm (Fig. S9) and 100 mM (Fig. 3D) at different time points. The H2O2 responsiveness was much stronger when the H2O2 concentration was 50 or 100 mM, relative to 1 mM (Fig. 3E). The production of HA indicated that H2O2-triggered QM release occurred. During the H2O2-induced decomposition of arylboronic esters, the fluorescence of Ce6 would be influenced since micelle architecture would change when the balance of hydrophilic-hydrophobic interaction was destroyed. We prepared blank micelles with a concentration of 0.125 mg/mL as we observed fluorescence quenching in Fig. 2C and incubated them with 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, or 100 mM H2O2 at 37 °C for different time points. The fluorescence of Ce6 gradually recovered. This phenomenon was likely because the decomposition of arylboronic esters increased the hydrophilicity of micelle and relieved the fluorescence quenching. Fig. 3F showed that at 50 and 100 mM H2O2, the fluorescence of Ce6 was significantly increased.

3.3. In vitro ROS elevation and GSH depletion

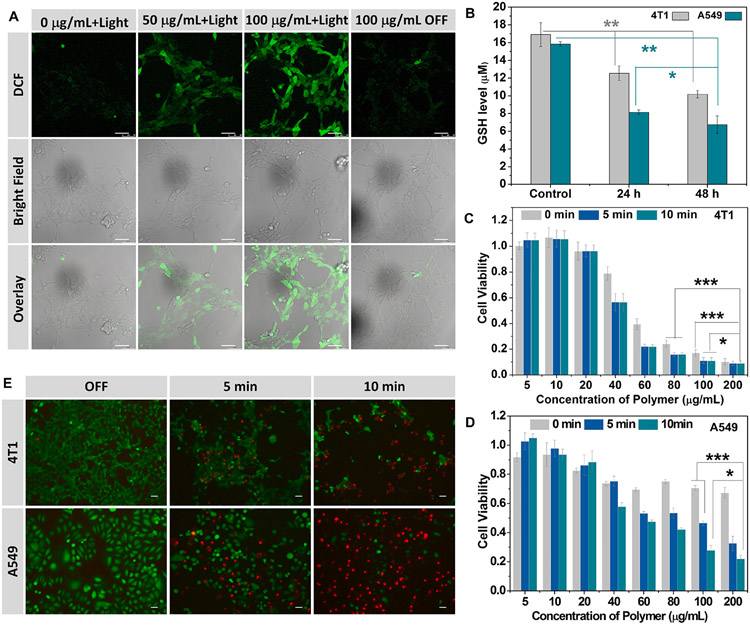

The cytotoxicity of blank micelle was studied using an MTT assay. As shown in Fig. S10, blank micelles were noncytotoxic to NIH/3T3 fibroblasts for the concentrations from 10 to 200 μg/mL in the dark. The ROS generated by Ce6 under light irradiation was verified by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) by using DCFH-DA as ROS fluorescence probe. Strong green fluorescence of DCF was observed in both 4T1 and A549 cells treated with micelles under 660 nm light irradiation (Figs. 4A and S11). In contrast, almost no green fluorescence was observed in control group without micelle incubation. This result demonstrated that polymeric micelles generated ROS for PDT under light irradiation. To further evaluate the ROS production in the CLSM image, we used ImageJ software to compare the mean fluorescence intensity of different nanoparticle concentration under light irradiation (Fig. S12). We also observed that the micelle group under no light irradiation condition was slightly brighter than control group without micelle incubation (Figs. 4A and S11). This is presumably due to the depletion of GSH, which caused a little high level of ROS. To confirm this, the influence of irradiation time on intracellular ROS generation by blank micelles was quantitatively examined using flow cytometry. Fig. S13 showed that the ROS level in the micelle without light irradiation was a little bit higher than cells without any treatment, implying a slightly high level of ROS caused by the depletion of GSH. This Fig. S13 also demonstrated that the intracellular ROS generation was positively correlated with the irradiation time.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of in vitro ROS elevation and GSH depletion. (A) CLSM images of intracellular ROS generation in 4T1 cancer cells in different conditions. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) GSH depletion in 4T1 cells after treatment with blank polymeric micelles (100 μg/mL). D) Phototoxicity of different micelle concentration against 4T1 (C) and A549 (D) cells with 660 nm light irradiation. (E) Fluorescence images of cells stained by Calcein-AM (green, live cells) and PI (red, dead cells) after light irradiation for 0, 5 and 10 min. Scale bar: 50 μm.

To evaluate the GSH-depleting ability of blank micelles in 4T1 and A549 cells, we used GSH/GSSG assay to measure the GSH concentration after cells were treated for different durations. As shown in Fig. 4B, the GSH concentration was decreased after incubation with blank micelles compared with untreated cells. We also observed similar the GSH depletion in human breast cancer cell MFC-7 upon micelle treatment (Fig. S14). Cancer cells are considered more dependent on antioxidants for cell survival and more vulnerable to oxidative stress due to the distorted redox balance [13]. Compared with cancer cells, NIH/3T3 cells have a lower GSH concentration (Fig. S14). Generally, the elevated GSH concentrations in cancer cells compared to the corresponding normal cells was also observed in others’ papers [40]. Indicating that cancer cells might be more sensitive for ROS generation causing by GSH depletion than normal cells. These results demonstrated the potent of GSH depletion ability of the blank polymeric micelles.

Based on these results, the phototoxicity of micelles on 4T1 and A549 cancer cells under light irradiation was measured to evaluate the PDT efficiency. As shown in Fig. 4C and D, the unirradiated group showed increased cytotoxicity to 4T1 and A549 cells along with increasing micelle concentrations due to GSH depletion. Also, the cell viability was markedly decreased with light irradiation compared with the nonirradiation group. The dose-dependent anticancer effects in 4T1 cells were more sensitive to PDT than A549 cells. The anticancer effect of PDT was further verified by cell staining. The cells were treated without or with light irradiation for 5 or 10 min and then stained with calcein-AM and PI (Fig. 4E). Strong green fluorescence was observed in the cells treated with blank micelles without light, suggesting the low cytotoxicity of micelle alone. After light irradiation and cell staining, some dead cells were washed away; however, we still observed red fluorescence remarkably increased after PDT. These results further confirmed that polymeric micelles could be used for PDT and the anticancer effect was dependent on the irradiation time.

3.4. Drug release, intracellular uptake and in vitro antitumor efficacy of DOX-loaded micelles

Hydrophobic doxorubicin was used as a model anticancer drug in our micelles for cancer chemotherapy (Fig. S15A). The DOX loading capacity (11.5%) and efficiency (52.0%) were calculated through fluorescence measurement with the calibration curve of DOX-DMSO solution. The drug release profiles of DOX loaded micelles were tested in PBS solutions at pH 7.4 and 5.0 at 37 °C (Fig. S15B). 54% of DOX was released from micelles within 12 h in cell culture medium at pH 5.0, and 43% DOX was released at pH 7.4. The faster release of DOX in acidic conditions was ascribed to the enhanced solubility of DOX at acidic pH. DOX release from drug-loaded micelles was slightly increased to 56% in the presence of 50 mM H2O2 due to the decomposition of arylboronic esters in the micelles. However, it didn’t accelerate DOX release much faster because the structure of the micelles didn’t thoroughly destroy since the PCL hydrophobic core still existed.

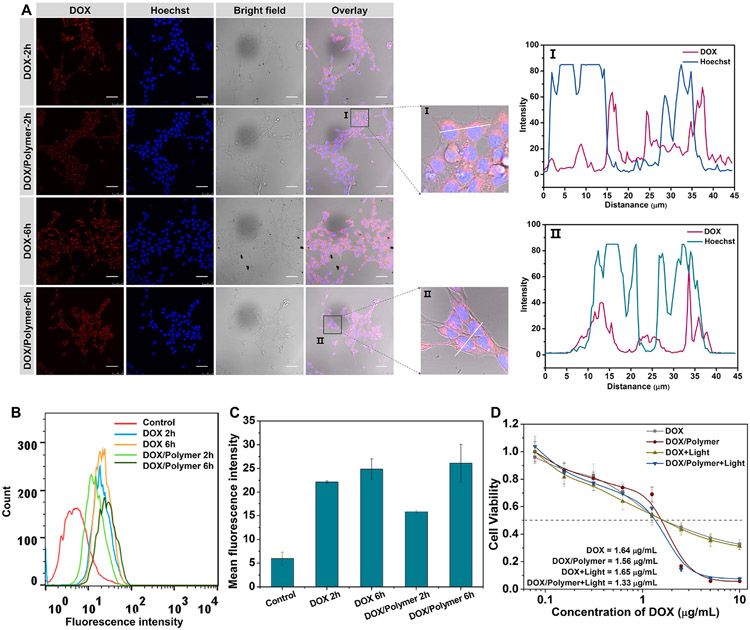

The intracellular localization of DOX-loaded micelles (DOX/Polymer) in 4T1 and A549 cells was investigated by CLSM. The red fluorescence of DOX was observed in the cytoplasm of 4T1 cells after incubation with DOX or DOX/Polymer for 2 h (Fig. 5A). Free DOX had stronger red fluorescence than DOX/Polymer, suggesting free drug diffusion had an advantage to enter into the cell cytoplasm in a short time. With an increase of the incubation time up to 6 h, a stronger red fluorescence was observed in all group and we could see almost no difference between DOX and DOX/Polymer, suggesting that a sustained internalized and drug release from DOX-loaded micelles. In the close-up image of DOX/Polymer, the red fluorescence of DOX was co-localized with the blue fluorescence of nuclei stained by Hochest showing as purple fluorescence indication the diffuse of DOX into nuclei. From the intracellular co-location analysis (Fig. 5A), we also could see that DOX were co-localized within the Hochest, suggesting some DOX could be taken into effect by inserting into DNA. Similar results were also observed in A549 cells (Fig S16A). The cellular internalization of DOX and DOX/Polymer in 4T1 cells was further studied by flow cytometry (Fig. 5B). We observed comparable cellular uptake between free DOX and of DOX-loaded micelles at 6 h. The mean fluorescence intensity of cells treated with DOX-loaded micelles was almost identical to those treated with DOX (Fig. 5C). These results suggested that the micelles effectively delivered DOX into tumor cells, providing the basis to inhibit cancer cell growth.

Fig. 5.

Characterization of DOX-loaded micelles. Cellular uptake of free DOX and DOX/Polymer by 4T1 cells at different time points by CLSM (Scale bar: 50 μm) (A) and flow cytometry (B). (C) The mean fluorescence intensity of DOX in 4T1 cells by flow cytometry. (D) In vitro anticancer activity of free DOX and DOX/Polymer against 4T1 cells in dark and light irradiation condition.

The in vitro anticancer activity of DOX-loaded micelles (DOX/Polymer) with light irradiation was investigated to evaluate its potency for combination anti-cancer therapy. Hydrophobic DOX was used as a control. As shown in Figs. 5D and S16B, DOX showed a moderate antitumor effect against 4T1 and A549 cells, regardless of light irradiation. The anticancer effect of micelles outperformed that of free DOX regardless of irradiation. The half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of DOX/Polymer under irradiation were 1.24 and 2.39-fold lower than that of DOX in 4T1 and A549 cells.

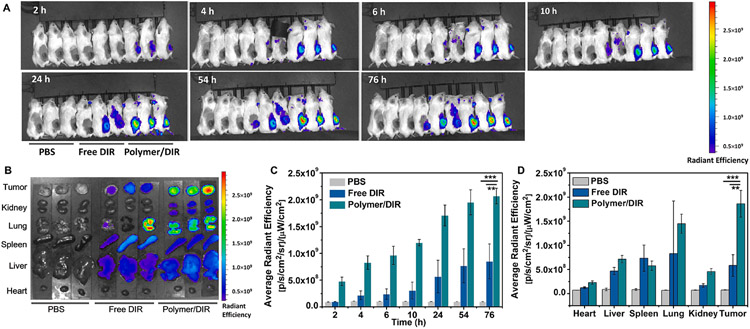

3.5. In vivo antitumor efficacy

As a fluorescence probe, DIR was loaded into the polymeric micelles to trace the biodistribution of micelles in vivo [41]. From the whole-body fluorescence imaging (Fig. 6A), we could see strong fluorescence emission at the tumor site for polymer loaded DIR (Polymer/DIR) comparing with free DIR. The average fluorescence intensity in the tumor sites became stronger as time went by (Fig. 6C). The passive tumor accumulation was further confirmed by fluorescence imaging and average fluorescence intensity of major organs and tumor tissues (Fig. 6B, D), which demonstrated the polymeric delivery system had a distinct advantage over free fluorescence probe. These results proved that nanoparticles could significantly extend the systemic circulation time and facilitated the accumulation at tumor sites.

Fig. 6.

Imaging of micelle bio-distribution in mice. (A) In vivo fluorescence imaging of 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice after intravenous injection of polymer nanoparticles loaded DIR (Polymer/DIR). (n = 3) (B) Ex vivo fluorescence images of tumor and major organs. (C) Average fluorescence intensity at the tumor sites from the whole-body image at different time points. (D) Average fluorescence intensity in the tumor and major organs in from mice administered.

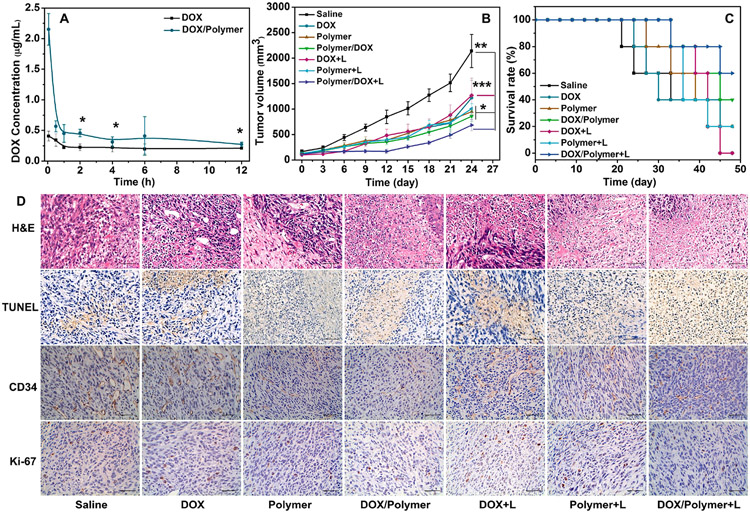

Long blood circulation time is a crucial factor for efficient cancer therapy of nanoparticles. The pharmacokinetics of DOX/Polymer in BALB/c mice was investigated by examining the blood concentration of DOX using fluorescence spectroscopy (Fig. 7A). The maximal drug concentration in blood (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC) of DOX/Polymer were 2.15 μg/mL and 4.86, respectively; 5.24 and 1.86-fold higher than those of DOX (0.14 μg/mL and 2.62). These results showed that DOX/Polymer micelle increased drug concentration in blood, and prolonged blood circulation time.

Fig. 7.

In vivo antitumor efficacy. (A) Pharmacokinetics of DOX and DOX/Polymer micelles. Tumor volumes (B) of tumor-bearing mice treated with different formulations and conditions and survival rates (C) of tumor-bearing mice; mice were sacrificed when the tumor volume reached 2000 mm3. (D) Immunohistochemical analysis (CD34 and Ki-67), TUNEL assay, and H&E staining results of the tumor sections. (Scale bar: 50 μm).

The tumor therapeutic effect was evaluated using a 4T1 tumor model in syngeneic BALB/c mice. Mice bearing 4T1 tumors (100–200 mm3) were randomly divided into seven groups for treatment: (i) saline, (ii) DOX, (iii) Polymer, (iv) DOX/Polymer, (v) DOX + L, (vi) Polymer + L, and (vii) DOX/Polymer + L, here L means treatment with light irradiation (Fig. S19). After treatment for 24 days, the tumor volume of the mice administrated with DOX/Polymer group was significantly smaller than that of the saline and free DOX group (Fig. 7B). Notably, the blank polymeric micelles did show slight antitumor efficacy. Light irradiation promoted the tumor therapeutic efficacy. The body weights of mice were monitored to evaluate the systemic toxicity. The mice treated with DOX showed a significant body weight loss during the experiment (Fig. S17A), indicating the severe systemic toxicity of DOX. In contrast, mice in other groups showed a stable body weight. The survival rates of the mice treated with the seven groups were measured (Fig. 7C). Mice in all groups except saline and DOX group survived after 24 days of treatment, and 20% of mice died for the DOX group within 24 days. The mice were sacrificed on day 24, and the tumor weights were measured (Fig. S17B). Consistently, mice treated with DOX/Polymer + L showed the lowest tumor weight. Key organs, including heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, were assessed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for systemic toxicity. The micellar formulations caused negligible organ damage and confirmed good biosafety (Fig. S18). These results showed that the designed polymeric micelles enhanced the antitumor efficiency in vivo and minimized the side effects.

The antitumor effects were further assessed by H&E, tunnel, and immunohistochemical analysis (CD34 and Ki-67) staining in tumor tissues (Fig. 7D). All groups indicated of tumor necrosis of varying degrees from H&E staining. The group of DOX/Polymr + L showed the largest area of tumor coagulative necrosis (approximately 75%), suggesting the most effective tumor inhibition of DOX/Polymer + L. This result implied that laser irradiation caused notable apoptosis of the tumor cells (approximately 70%), as confirmed by the TUNEL staining. The tumors were further used for immunohistochemical of endothelial cell marker CD34 to study vascular proliferation and proliferative markers of Ki-67 to study proliferative activity. Consistent with the in vivo antitumor studies, the mice treated with DOX/Polymer + L showed a much lower percentage of positive cells than those in the saline group, indicating effective inhibition of the cell proliferation and induction of the apoptosis of tumor cells.

4. Conclusion

We have synthesized a star shape polymer PEG(-b-PCLCe6)-b-PBEMA based on the Passerini three-component reaction, which both enhanced ROS generation during PDT and in situ decreased the level of GSH in cancer cells. The GSH depletion strategy was induced to make up for the shortcomings of PDT to reach the “threshold concept” of oxidative stress for cancer therapy. The polycaprolactone conjugated with Ce6 served as hydrophobic segments to promote micelle formation and fulfills PDT under light irradiation. The H2O2-labile group of arylboronic esters pendent on the third segment was designed for H2O2-induced QM release for GSH depletion. Through the UV–Vis and fluorescence spectrum, we have explored the assembly properties of blank micelle·H2O2-induced QM release and micelle decomposition were further characterized by 1H NMR and fluorescence spectrum, showing rapid responsiveness at H2O2 incubation. This blank polymeric micelle also showed ROS elevation and GSH depletion in vitro as we characterized in 4T1 and A549 cancer cells. Hydrophobic anti-cancer drug DOX could be efficiently loaded into the micelle at a loading capacity of 11.5% and showed H2O2- and pH-trigged release. The ROS generation under light irradiation and GSH elimination combined with chemotherapy were evaluated both in vitro and in vivo. The anticancer effect of micelles outperformed than free DOX. This combined anticancer strategy displayed improved antitumor efficiency over each monotherapy and showed great potentials for multimodal therapy of cancer.

Highly cytotoxic ROS is generated during PDT, which not only causes cell death directly via oxidative stress but also can induce immune response indirectly by releasing dying tumor cell debris [42,43]. The inducing of immunogenicity during PDT was known as immunogenic cell death (ICD). Typically, ICD is accompanied by the transportation of pro-apoptotic calreticulin (CRT) from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the surface of dying tumor cells [44,45]. Thus, CRT expression level on the surface of cells is a distinct biomarker undergoing ICD. In this paper, we finally evaluated the CRT expression on 4T1 cells treated with different irradiation times. The cells were stained with Alexa Flour 647-CRT antibody and Zombie UV. The fluorescence intensity of CRT-stained cells was gated on Zombie UV-negative cells. (Fig. S20A). The results showed that CTR expression was significantly elevated when 4T1 cells were treated with PDT (Fig. S20B), suggesting the immunogenicity inducing during PDT. In addition, the levels of CRT was increased along with irradiation time increased to 3 min. Therefore, additional studies aiming to identify the optimal immune-stimulating effects of this triple combined drug delivery system may be highly beneficial. We believe the combination of chemotherapy, ROS generation during PDT, and in situ GSH decreasing designed in the current study offer a new strategy for treating tumors more effectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the financial support of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51773130). This work was also supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81974435 and 81922052 to S.L.) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (2019B151502011 to S.L.). G.Z. acknowledges partial support from the Center for Pharmaceutical Engineering and Sciences-VCU School of Pharmacy, NIH KL2 Scholarship and Endowment Fund from VCU C. Kenneth and Dianne Wright Center for Clinical and Translational Research (UL1TR002649 and KL2TR002648), NINDS (R21NS114455), and VCU Presidential Research Quest Fund. Microscopy was performed at the VCU Microscopy Facility, supported in part by funding from NIH-NINDS Center Core Grant 5 P30 NS047463 and, in part, by funding from the NIH-NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016059. Flow cytometry was performed at the VCU Massey Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Shared Resource, which is supported, in part, with funding from NIH-NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016059.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.128561.

References

- [1].Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW, Regulation of cancer cell metabolism, Nat. Rev. Cancer 11 (2011) 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Holmström KM, Finkel T, Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 15 (2014) 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nathan C, Cunningham-Bussel A, Beyond oxidative stress: an immunologist’s guide to reactive oxygen species, Nat. Rev. Immunol 13 (2013) 349–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Trachootham D, Lu W, Ogasawara MA, Valle N-D, Huang P, Redox regulation of cell survival, Antioxid. Redox Signal 10 (2008) 1343–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P, Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 8 (2009) 579–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Perillo B, Di Donato M, Pezone A, Di Zazzo E, Giovannelli P, Galasso G, Castoria G, Migliaccio A, ROS in cancer therapy: the bright side of the moon, Exp. Mol. Med 52 (2020) 192–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Firczuk M, Bajor M, Graczyk-Jarzynka A, Fidyt K, Goral A, Zagozdzon R, Harnessing altered oxidative metabolism in cancer by augmented prooxidant therapy, Cancer Lett. 471 (2020) 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yang B, Chen Y, Shi J, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)-Based Nanomedicine, Chem. Rev 119 (2019) 4881–4985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhang M, Guo X, Wang M, Liu K, Tumor microenvironment-induced structure changing drug/gene delivery system for overcoming delivery-associated challenges, J. Control. Release 323 (2020) 203–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cheng F, Su T, Luo K, Pu Y, He B, The polymerization kinetics, oxidation-responsiveness, and in vitro anticancer efficacy of poly(ester-thioether)s, J. Mater. Chem. B 7 (2019) 1005–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhou Z, Ni K, Deng H, Chen X, Dancing with reactive oxygen species generation and elimination in nanotheranostics for disease treatment, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev (2020. DR-13573; No of Pages 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhou Z, Song J, Nie L, Chen X, Reactive oxygen species generating systems meeting challenges of photodynamic cancer therapy, Chem. Soc. Rev 45 (2016) 6597–6626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hileman EO, Liu J, Albitar M, Keating MJ, Huang P, Intrinsic oxidative stress in cancer cells: a biochemical basis for therapeutic selectivity, Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol 53 (2004) 209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Huang Y, Jiang Y, Xiao Z, Shen Y, Huang L, Xu X, Wei G, Xu C, Zhao C, Three birds with one stone: a ferric pyrophosphate based nanoagent for synergetic NIR-triggered photo/chemodynamic therapy with glutathione depletion, Chem. Eng. J 380 (2020), 122369. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Liu F, Gong S, Shen M, He T, Liang X, Shu Y, Wang X, Ma S, Li X, Zhang M, Wu Q, Gong C, A glutathione-activatable nanoplatform for enhanced photodynamic therapy with simultaneous hypoxia relief and glutathione depletion, Chem. Eng. J 403 (2021, 126305. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dong Z, Feng L, Chao Y, Hao Y, Chen M, Gong F, Han X, Zhang R, Cheng L, Liu Z, Amplification of tumor oxidative stresses with liposomal fenton catalyst and glutathione inhibitor for enhanced cancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy, Nano Lett. 19 (2019) 805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhong X, Wang X, Cheng L, Tang YA, Zhan G, Gong F, Zhang R, Hu J, Liu Z, Yang X, GSH-depleted PtCu3 nanocages for chemodynamic – enhanced sonodynamic cancer therap, Adv Funct Mater. 30 (2020) 1907954. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ju E, Dong K, Chen Z, Liu Z, Liu C, Huang Y, Wang Z, Pu F, Ren J, Qu X, Copper(II)–graphitic carbon nitride triggered synergy: improved ROS generation and reduced glutathione levels for enhanced photodynamic therapy, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 55 (2016) 11467–11471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Liu C, Wang D, Zhang S, Cheng Y, Yang F, Xing Y, Xu T, Dong H, Zhang X, Biodegradable biomimic copper/manganese silicate nanospheres for chemodynamic/photodynamic synergistic therapy with simultaneous glutathione depletion and hypoxia relief, ACS Nano 13 (2019) 4267–4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gong F, Cheng L, Yang N, Betzer O, Feng L, Zhou Q, Li Y, Chen R, Popovtzer R, Liu Z, Ultrasmall oxygen-deficient bimetallic oxide MnWOX nanoparticles for depletion of endogenous GSH and enhanced sonodynamic cancer therapy, Adv. Mater 31 (2019) 1900730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Heuer-Jungemann A, Feliu N, Bakaimi I, Hamaly M, Alkilany A, Chakraborty I, Masood A, Casula MF, Kostopoulou A, Oh E, Susumu K, Stewart MH, Medintz IL, Stratakis E, Parak WJ, Kanaras AG, The role of ligands in the chemical synthesis and applications of inorganic nanoparticles, Chem. Rev 119 (2019) 4819–4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Xu K, Thornalley PJ, Involvement of glutathione metabolism in the cytotoxicity of the phenethyl isothiocyanate and its cysteine conjugate to human leukaemia cells in vitro, Biochem. Pharmacol 61 (2001) 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dvorakova K, Payne CM, Tome ME, Briehl MM, McClure T, Dorr RT, Induction of oxidative stress and apoptosis in myeloma cells by the aziridine-containing agent imexon, Biochem. Pharmacol 60 (2000) 749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ma S, Song W, Xu Y, Si X, Lv S, Zhang Y, Tang Z, Chen X, Rationally Designed Polymer Conjugate For Tumor-Specific Amplification Of Oxidative Stress And Boosting Antitumor Immunity, Nano Lett. 20 (2020) 2514–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hagen H, Marzenell P, Jentzsch E, Wenz F, Veldwijk MR, Mokhir A, Aminoferrocene-based prodrugs activated by reactive oxygen species, J. Med. Chem 55 (2012) 924–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yin W, Li J, Ke W, Zha Z, Ge Z, Integrated nanoparticles to synergistically elevate tumor oxidative stress and suppress antioxidative capability for amplified oxidation therapy, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9 (2017) 29538–29546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cao H, Zhong S, Wang Q, Chen C, Tian J, Zhang W, Enhanced photodynamic therapy based on an amphiphilic branched copolymer with pendant vinyl groups for simultaneous GSH depletion and Ce6 release, J. Mater. Chem. B 8 (2020) 478–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kamaly N, Yameen B, Wu J, Farokhzad OC, Degradable controlled-release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: mechanisms of controlling drug release, Chem. Rev 116 (2016) 2602–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Su T, Peng X, Cao J, Chang J, Liu R, Gu Z, He B, Functionalization of biodegradable hyperbranched poly(α,β-malic acid) as a nanocarrier platform for anticancer drug delivery, RSC Adv. 5 (2015) 13157–13165. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Li L, Kan X-W, Deng X-X, Song C-C, Du F-S, Li Z-C, Simultaneous dual end-functionalization of peg via the passerini three-component reaction for the synthesis of ABC miktoarm terpolymers, J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem 51 (2013) 865–873. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang Q, Tao H, Lin Y, Hu Y, An H, Zhang D, Feng S, Hu H, Wang R, Li X, Zhang J, A superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic nanomedicine for targeted therapy of inflammatory bowel disease, Biomaterials 105 (2016) 206–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chen Y, Zhang YX, Wu ZF, Peng XY, Su T, Cao J, He B, Li S, Biodegradable poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(ε-carprolactone) polymeric micelles with different tailored topological amphiphilies for doxorubicin (DOX) drug delivery, RSC Adv. 6 (2016) 58160–58172. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Van Thienen TG, Raemdonck K, Demeester J, De Smedt SC, Protein release from biodegradable dextran nanogels, Langmuir 23 (2007) 9794–9801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Deng X, Liang Y, Peng X, Su T, Luo S, Cao J, Gu Z, He B, A facile strategy to generate polymeric nanoparticles for synergistic chemo-photodynamic therapy, Chem. Commun 51 (2015) 4271–4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Liu K, Xing R, Zou Q, Ma G, Möhwald H, Yan X, Simple peptide-tuned self-assembly of photosensitizers towards anticancer photodynamic therapy, Angew Chem Int Ed. 55 (2016) 3036–3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zhu T, Shi L, Yu C, Dong Y, Qiu F, Shen L, Qian Q, Zhou G, Zhu X, Ferroptosis promotes photodynamic therapy: supramolecular photosensitizer-inducer nanodrug for enhanced cancer treatment, Theranostics 9 (2019) 3293–3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhang M, Song C-C, Su S, Du F-S, Li Z-C, ROS-activated ratiometric fluorescent polymeric nanoparticles for self-reporting drug delivery, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10 (2018) 7798–7810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zhang M, Song C-C, Du F-S, Li Z-C, Supersensitive oxidation-responsive biodegradable PEG hydrogels for glucose-triggered insulin delivery, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9 (2017) 25905–25914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hulsman N, Medema JP, Bos C, Jongejan A, Leurs R, Smit MJ, de Esch IJP, Richel D, Wijtmans M, Chemical insights in the concept of hybrid drugs: the antitumor effect of nitric oxide-donating aspirin involves a quinone methide but not nitric oxide nor aspirin, J. Med. Chem 50 (2007) 2424–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zhang X, Wu F-G, Liu P, Gu N, Chen Z, Enhanced fluorescence of gold nanoclusters composed of HAuCl4 and histidine by glutathione: glutathione detection and selective cancer cell imaging, Small. 10 (2014) 5170–5177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Meng F, Wang J, Ping Q, Yeo Y, Quantitative assessment of nanopartide biodistribution by fluorescence imaging, revisited, ACS Nano 12 (2018) 6458–6468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Krysko DV, Garg AD, Kaczmarek A, Krysko O, Agostinis P, Vandenabeele P, Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy, Nat. Rev. Cancer 12 (2012) 860–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Castano AP, Mroz P, Hamblin MR, Photodynamic therapy and anti-tumour immunity, Nat. Rev. Cancer 6 (2006) 535–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Garg AD, Krysko DV, Vandenabeele P, Agostinis P, Hypericin-based photodynamic therapy induces surface exposure of damage-associated molecular patterns like HSP70 and calreticulin, Cancer Immunol. Immunother 61 (2012) 215–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Galluzzi L, Buqué A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G, Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease, Nat. Rev. Immunol 17 (2017) 97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.