Abstract

Depersonalisation/derealisation (DD) syndrome is often associated with severe traumatic experiences and the use of certain medications. Our patient reported experiencing a transient DD phenomenon a few hours after taking 37.5 mg of tramadol, together with etoricoxib, acetaminophen and eperisone. His symptoms subsided upon tramadol discontinuation, suggesting the possibility of tramadol-induced DD. A study of the patient’s cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 polymorphism, which mainly metabolises tramadol, indicated normal metaboliser status with reduced function. The concomitant administration of the CYP2D6 inhibitor, etoricoxib, would have led to higher concentrations of the serotonergic parent tramadol, providing an explanation for the patient’s symptoms.

Keywords: Drug interactions, Psychiatry, Toxicology

Background

Depersonalisation/derealisation (DD) is a dissociative phenomenon, characterised by a feeling of detachment from one’s body or surroundings.1 Depersonalisation involves a sense of self-alienation, where individuals perceive themselves as an observer of their own body or mental processes from a distance. Meanwhile, derealisation refers to an altered perception of one’s surroundings that feel unreal. These conditions are generally strongly related to traumatic events.1 However, relevant studies regarding their pathogenesis and treatment are still lacking.2 Individuals with persistent and severe symptoms that cause distress or functional impairment may be diagnosed with DD disorder. In this report, we report a case of transient DD syndrome induced by opioid analgesia—tramadol.

Case presentation

A male patient in his 20s with a medical history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), treated with methylphenidate (10 mg/day, as needed), reported worsening fibromyalgia around his neck and shoulders. He was prescribed etoricoxib, eperisone and tramadol/acetaminophen (37.5 mg/325 mg combination) and received a session of Thai traditional massage to alleviate his pain.

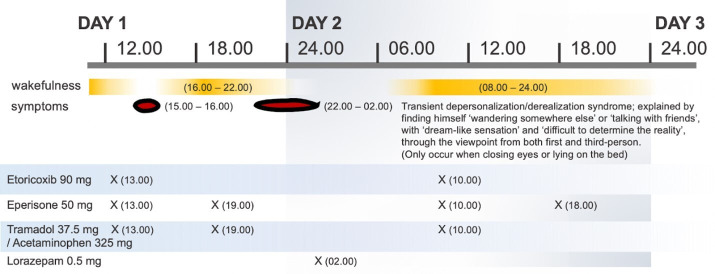

Although his fibromyalgia partially improved after the first dose of medications, he experienced a transient dream-like state and a sense of unreality of self. During this episode, he observed himself ‘wandering somewhere else’ or ‘interacting with friends and family members’. He viewed these events from both first-person and third-person perspectives and could hardly determine reality. He denied any recollection of ‘not being himself’ during the period. What he saw appeared unclear and shadowy, with the exception of lucid human bodies and faces. All symptoms ceased abruptly upon awakening, enabling him to resume his normal daily activities. However, his symptoms recurred during sleep, so he took 0.5 mg of lorazepam to get to sleep. These two episodes of abnormal perceptions occurred about 2–3 hours after ingestion of tramadol and eperisone and lasted for a few hours. The medication timeline is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of each medication used and the onset of depersonalisation/derealisation.

A psychiatric evaluation revealed no significant stressors except for subtle fatigue and pressure from his studies. His ADHD had been well controlled and required no pharmacotherapy for the last 3 months.

Investigations

Urine screening tests for illicit drug use and serum alcohol concentration were negative. The suspected cause of his DD symptoms was tramadol, which led to an investigation of his cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 polymorphism, the primary metaboliser. The result showed the patient had the CYP2D6*1/*10 genotype, indicative of a normal metaboliser with reduced function.3

Differential diagnosis

Although perceptual changes can be a characteristic of acute delirium, this diagnosis seems unlikely in our case, as the patient maintained intact consciousness. The diagnosis of other dissociative disorders typically requires longer duration of symptoms.

Treatment

Upon informing his doctor of the aforementioned symptoms, the patient was advised to discontinue tramadol/acetaminophen. It was not possible to determine the exact duration of recovery, as the symptoms did not recur. He continued taking other medications for 5 days, during which his pain subsided without any relapse of the reported symptoms.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient is healthy, with no clinical signs of DD following the recommendation to discontinue tramadol. His ADHD is regularly monitored by the psychiatrist and effectively well controlled under methylphenidate.

Discussion

There was a possible causal relationship between the patient’s symptoms and the newly introduced medication (figure 1). The Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale (Naranjo Scale) score of 5 suggested that tramadol was considered probable cause of DD in our patient.4 This was supported by the onset of symptoms after the introduction of tramadol and their resolution after its cessation.5 Although acetaminophen was taken at the same time, previous multiple exposures to acetaminophen resulted in no adverse events.

Despite the unclear pathogenesis of DD, many studies have hypothesised that DD may relate to hypersensitivity to serotonin, metabolic encephalopathy, panic disorder or substance use.2 5 However, conflicting data exist regarding the role of serotonin in inducing or alleviating DD symptoms, with some early clinical trials suggesting both outcomes.6–11 Kappa-opioid receptor interaction can also lead to the symptom in a dose-dependent manner and can be reversed with an opioid antagonist such as naloxone.12 Given that tramadol is an opioid agonist that interacts with a kappa-opioid receptor and inhibits serotonin reuptake, it is reasonable to postulate that its interaction with these receptors is a plausible explanation.

The main challenges are to explain why the symptoms occur with a therapeutic dose of tramadol and which receptors play a dominant role in its pathogenesis. We speculate that the patient might have a decreased metabolism of tramadol, especially from the highly polymorphic CYP2D6 and/or CYP2B6 polymorphism.13 This would cause a higher concentration of the parent tramadol, the main compound that exerts a serotonergic effect, which is suspected to be the aetiology of DD.13 Although his predicted CYP2D6 phenotype was a normal metaboliser, the CYP2D6 activity was reduced due to allele CYP2D6*10.3 Etoricoxib, a weak CYP2D6 inhibitor,14 may have also lower tramadol metabolism. In this regard, we believe that dysregulation of serotonin levels may play a more significant role in this case.

While eperisone has a known central nervous system (CNS) depressant effect,15 there is a lack of literature about its potential to induce changes in perception. It is possible that combining eperisone with tramadol may increase the risk of CNS depression due to a synergistic effect or a possible drug interaction (no strong evidence), since eperisone is possibly metabolised by CYP3A4,15 like tramadol.13

The irregular intake of methylphenidate, a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, may be a potential factor for the manifestation of DD as withdrawal symptoms. Although the role of these neurotransmitters in the pathogenesis of DD is not well established, evidence suggests that treatment with norepinephrine agonists can either exacerbate or improve DD symptoms.11 16 17 Moreover, the patient’s underlying ADHD, which involves complex interactions among dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin,18 may increase susceptibility to unexpected serotonergic effects of tramadol. However, further investigation is needed to substantiate these speculations.

Confounding factors such as physical stress (painful fibromyalgia) might need to be considered in our patient despite the strong temporal relationship of the symptom with tramadol ingestion. However, the patient strongly denied other contributing factors such as lack of sleep, emotional stress and substance abuse.19 Our patient was recommended to avoid tramadol with other CYP2D6 substrates thereafter.

The limitation of our case is the subjective clinical diagnosis of DD. Additionally, to strengthen our hypothesis, it would be beneficial to evaluate the status of CYP2B6 (another highly polymorphic CYP) and measure the plasma concentration of suspected drugs, in this case—tramadol and their metabolites. Unfortunately, these tests are not available at our faculty.

Learning points.

This case demonstrated a patient with depersonalisation/derealisation from a therapeutic dosage of tramadol ingestion and was resolved after discontinuation of the medicine.

The lower metabolism of tramadol from cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 polymorphism increases tramadol concentration in the body thus increasing the serotonergic effects of tramadol.

Drug interaction, in this case, etoricoxib and tramadol, could potentially enhance the effect of serotonin and might play a role in the pathogenesis of the symptom.

Drug interaction and CYP polymorphism should be considered when the patient is subjected to polypharmacy.

Footnotes

Contributors: The following authors were responsible for drafting of the text, sourcing and editing of clinical images, investigation results, drawing original diagrams and algorithms, and critical revision for important intellectual content—SW, PT and ST. The following authors gave final approval of the manuscript—SW and ST.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Spiegel D, Lewis-Fernández R, Lanius R, et al. Dissociative disorders in DSM-5. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2013;9:299–326. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dell PF. Depersonalization: A new look at a neglected syndrome, by M. Sierra J Trauma Dissociation 2011;12:401–3. 10.1080/15299732.2011.573763 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamnanphon M, Wainipitapong S, Wiwattarangkul T, et al. CYP2D6 predicts plasma Donepezil concentrations in a cohort of Thai patients with mild to moderate dementia. Pharmgenomics Pers Med 2020;13:543–51. 10.2147/PGPM.S276230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981;30:239–45. 10.1038/clpt.1981.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen PR. Medication-associated depersonalization symptoms: report of transient depersonalization symptoms induced by Minocycline. Southern Medical Journal 2004;97:70–3. 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000083857.98870.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy DL, Mueller EA, Hill JL, et al. Comparative anxiogenic, Neuroendocrine, and other physiologic effects of M-chlorophenylpiperazine given intravenously or orally to healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology 1989;98:275–82. 10.1007/BF00444705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simeon D, Hollander E, Stein DJ, et al. Induction of depersonalization by the serotonin agonist meta-chlorophenylpiperazine. Psychiatry Res 1995;58:161–4. 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02538-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somer E, Amos-Williams T, Stein DJ. Evidence-based treatment for Depersonalisation-Derealisation disorder (DPRD). BMC Psychol 2013;1:20. 10.1186/2050-7283-1-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simeon D, Stein DJ, Hollander E. Treatment of depersonalization disorder with Clomipramine. Biol Psychiatry 1998;44:302–3. 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00023-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollander E, Liebowitz MR, DeCaria C, et al. Treatment of depersonalization with serotonin reuptake blockers. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990;10:200–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foguet Q, Alvárez MJ, Castells E, et al. Methylphenidate in depersonalization disorder: a case report. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2011;39:75–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nuller YL, Morozova MG, Kushnir ON, et al. Effect of naloxone therapy on depersonalization: a pilot study. J Psychopharmacol 2001;15:93–5. 10.1177/026988110101500205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong L, Stamer UM, Tzvetkov MV, et al. Pharmgkb summary: Tramadol pathway. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2014;24:374–80. 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassahun K, McIntosh IS, Shou M, et al. Role of human liver cytochrome P4503A in the metabolism of etoricoxib, a novel Cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitor. Drug Metab Dispos 2001;29:813–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamagiwa T, Amino M, Morita S, et al. A case of torsades de pointes induced by severe QT prolongation after an overdose of Eperisone and Triazolam in a patient receiving nifedipine. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2010;48:149–52. 10.3109/15563650903524126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghaffarinejad A, Mehdizadeh Zare Anari A, Pouya F. 2321 – Derealization due to Dextroamphetamine: a rare side effect which could cause premature discontinuation of treatment. European Psychiatry 2013;28:1. 10.1016/S0924-9338(13)77167-021920709 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khazaal Y, Zullino DF. Depersonalization-derealization syndrome induced by Reboxetine. Swiss Med Wkly 2003;133:398–9. 10.4414/smw.2003.10195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riley TB, Overton PG. Enhancing the efficacy of 5-HT uptake inhibitors in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Med Hypotheses 2019;133:109407. 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.109407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madden SP, Einhorn PM. Cannabis-induced depersonalization-derealization disorder. Am J Psychiatry Resid J 2018;13:3–6. 10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2018.130202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]