Abstract

Leiomyomas are common benign uterine smooth muscle tumours. Rarer subsets may demonstrate aggressive extrauterine growth which mimic metastatic disease. We discuss the case of a female patient in her 40s, with a long-standing atrophic right kidney, presenting with a 17 cm uterine mass demonstrating bilateral para-aortic and pelvic sidewall spread. Although biopsies favoured the diagnosis of a benign tumour, a leiomyosarcoma could not be excluded. The surgical complexity of the case was compounded by a tumour residing close to the only functioning kidney and engulfment of the inferior mesenteric artery. The surgical procedures indicated were a radical hysterectomy, the laterally extended endopelvic resection procedure to achieve clear margins in the pelvic sidewall and a left hemicolectomy. In the absence of formal guidelines, we present this challenging case to provide clarity into the histological assessment and surgical management of rare leiomyomas, as well as an overview of the current literature.

Keywords: Surgery, Obstetrics and gynaecology, Gynecological cancer

Background

Leiomyomas are the most common benign smooth muscle tumour of the uterus.1 Although typically confined to the uterus, rarer subsets may grow aggressively and demonstrate extrauterine extension while remaining histologically benign.1 2 This includes diffuse leiomyomatosis (DUL), intravenous leiomyoma (IVL) and cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma (CDL).1 Presentation of such subsets is often with vague symptoms like abdominal pain and abnormal vaginal bleeding.1 This non-specific presentation, coupled with the aggressive nature of the disease, commonly results in the misdiagnosis of metastatic leiomyosarcoma, which drastically alters a patient’s outcomes.3 4 Additional challenges in the care of such patients can be attributed to the paucity of guidelines and recommendations available on the diagnostic features and management of these rare, yet aggressive, entities.

We present the case of a patient with benign leiomyomas that demonstrates extensive spread into the abdomen. Our case adds to the limited literature documenting the magnitude of disease extension in these pathologies and highlights the role of histology in aiding diagnosis. We provide an overview on the available literature, with a focus on the underlying histological features distinguishing benign leiomyomas from metastatic disease. Furthermore, our case demonstrates the importance of surgical management in lieu of conservative management, particularly in instances of aggressive extrauterine growth.

Case presentation

Our patient, who is a woman in her 40s (gravidity 2), has a long history of known uterine fibroids and an atrophic right kidney (present since childhood). Other medical history of note includes cervical intraepithelial neoplasia II, which was diagnosed 10 years ago and managed with large loop excision of the transformation zone. The patient also underwent ureteric re-implantation during childhood. There is a family history of renal disease on the patient’s paternal side and her father is currently on dialysis. She is an ex-smoker, with a body mass index of 28.65, and is allergic to aspirin.

The patient noticed increase in her abdominal size and sought medical advice. Examination revealed a soft abdomen that was diffusely distended and tender over the lower quadrants. A mass in the pelvis could be palpated up until the level of the umbilicus. The patient was further investigated via the 2-week wait referral pathway, where CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a grossly enlarged uterus, measuring 17×11×15 cm, with solid/cystic nodules. CT also confirmed enlarged ovaries, bilateral para-aortic masses and a 4.9 cm left pelvic sidewall mass arising from the uterus. There was a lesion which sat at the angle of the left renal vein and bowel. The impression was that of a uterine neoplasm involving the ovaries, alongside bilateral para-aortic and pelvic sidewall spread. Further imaging by MRI revealed a grossly enlarged uterus with fibroids, while positron emission tomography showed more para-aortic spread. CA125 and lactate dehydrogenase were 34 IU/mL and 2125 IU/L, respectively. Biopsies of the para-aortic lymph nodes and uterus were conducted to aid diagnosis. The former showed spindle tumour cells with no nuclear pleomorphism, necrosis or mitotic activity. The specimen stained positive for SMA, desmin, oestrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR), and negative for CD34. Uterine samples stained similarly and showed fragments of endometrium glands separated by stroma, with scanty degenerated/necrotic material. All samples taken were inconclusive and a low-grade leiomyosarcoma could not be ruled out. The patient was commenced on letrozole and referred to the gynaecology oncology and sarcoma multidisciplinary team.

Careful deliberation was given on whether the patient should be managed surgically or medically using Zoladex injection. Surgery would most likely be curative, but given the proximity of the mass to the only functioning kidney, there was a risk the patient would require permanent dialysis. On the other hand, delaying surgery could increase the risk of developing life-threatening complications including emboli, compression of the pelvic vessels and bowel and bladder invasions (if the lesions proved to be malignant). Given the aforementioned risks, it was recommended that the patient was referred for urgent debulking surgery.

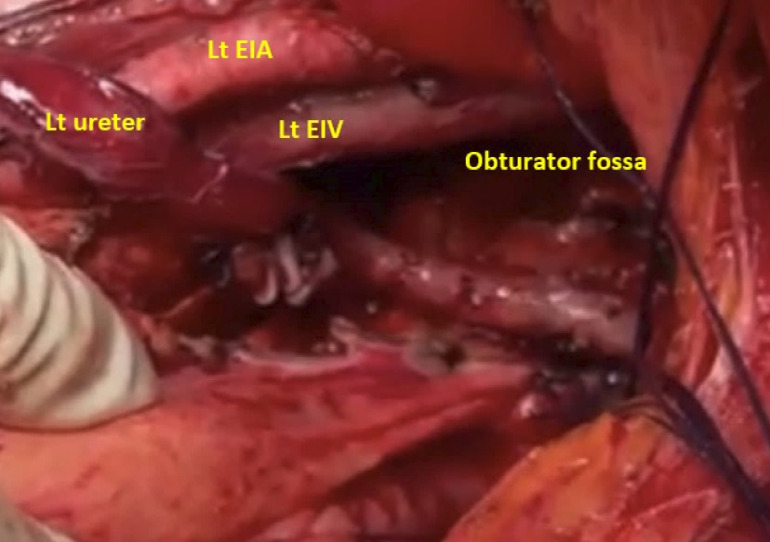

The patient underwent an extensive midline laparotomy in a joint procedure with the urology and colorectal team, which revealed three masses—one in the left pelvic sidewall and two bilateral retroperitoneal masses. A cystoscopy at the start of the procedure revealed grossly distorted anatomy and stenting failed. A radical hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy was completed. Laterally extended endopelvic resection (LEER) was used to achieve complete margins on the left pelvic side. The internal iliac artery was sacrificed, and the obturator fossa was dissected, alongside identification of the obturator nerve and vessels (figure 1). The lateral sidewall tumour was then removed, carefully separating it from the sidewall vessels. The retroperitoneal space was opened after mobilisation of the bowel from the lateral pelvic wall, using the Mattle Bracht and Matoux manoeuvres. As the tumour engulfed the inferior mesenteric artery, this vessel and the left colic artery had to be ligated (figure 2). This resulted in a left hemicolectomy with end-to-end anastomosis. Both retroperitoneal tumours were then carefully excised and great care was taken to ensure the left ureter, renal vessels and kidney were not injured. The kidney was observed for 15 min and appeared to be well perfused. Although the left ureter was bruised and congested, it was vermiculating well. There was around 2.5 L of blood loss. Overall, this was a major prolonged surgery that lasted for 8 hours.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative images during laterally extended endopelvic resection. EIA, external iliac artery; EIV, external iliac vein; Lt, left.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative images of the abdomen. CIA, common iliac artery; IMA, inferior mesenteric artery; IVC, inferior vena cava; Lt, left; Rt, right.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperatively, the patient was commenced on a standard regimen of low molecular weight heparin and co-amoxiclav for 28 and 3 days, respectively. A drain was placed in the left lower quadrant, which remained until the bowels opened. The catheter remained for 5 days and urinary output was carefully monitored for early signs of renal impairment. The patient had a smooth recovery and was discharged 5 days post-surgery and followed up after 3 weeks. Her kidney function remained normal, with a urea of 5.3 mmol/L and creatine of 77 µmol/L.

Postoperatively, the histology revealed a diagnosis of leiomyoma and no evidence of malignancy. Macroscopically, the tumour arose from the parametrial surface of the uterus, measuring 12.6 cm in diameter. There were multiple discrete, well-circumscribed, cream-coloured, whorled tumours. This was compatible with leiomyomata. On sectioning, the tumour appeared to have arisen from the anterior and posterior myometrium and grew superiorly out from the fundus. There was a tumour deposit within the vessels of the lower uterine cavity. The histology showed ill-defined smooth muscle lesions with areas of infiltrative/intravascular growth. These lesions had mildly increased cellularity but no cytological atypia or tumour necrosis could be detected. Immunohistochemistry showed diffuse strong staining for SMA and desmin, variable strong staining for H-caldesmon, diffuse strong staining for PR (8/8) and patchy staining for ER (7/8). Fumarate hydratase (FH) staining was retained. The left pelvic wall and retroperitoneal masses showed homogeneous, cream-coloured, whorled tumours with focal areas of haemorrhage, macroscopically.

All masses appeared to be completely excised and were morphologically consistent with benign uterine leiomyomas. There were no histological features satisfying the diagnostic criteria of leiomyosarcoma. The report suggested three possible subtypes of leiomyomas presenting in this patient, which included DUL, IVL and CDL with intravenous extension.

Discussion

The aggressive nature of these leiomyoma subsets can obscure the diagnosis, causing them to be misinterpreted as a metastatic leiomyosarcoma, rather than the much rarer benign counterpart.3 4 This misdiagnosis can have a great impact on the management and outcomes for the patient, as surgical intervention may only be palliative for a metastatic sarcoma but would be curative for a leiomyoma. The gold standard for distinguishing between benign and malignant uterine tumours is histological analysis, where the presence of features such as atypia and tumour necrosis will favour the latter.1 4 Moreover, histology can further differentiate between benign subsets of leiomyomas.1 It is therefore imperative that clinicians make proficient use of histology as a tool for diagnosis. This discussion will consider the pathologies of DUL, IVL and CDL, with a focus on their individual histological traits, as well as exploring the approach to surgical management in our case.

DUL is a rare, benign uterine pathology which is distinguished from fibroids by the involvement of the entire myometrium with multiple confluent, small, smooth muscle nodules.1 Insight into disease aetiology is limited but non-random X-allele inactivation has demonstrated that each lesion arises from an independent monoclonal population.5 This suggests that DUL is an augmented version of multiple leiomyomas, where the different nodules coalesce and cannot be distinguished. Macroscopically, the uterus appears to be symmetrically enlarged (unlike typical fibroids which is asymmetrical) and stains similarly to typical fibroids.1 6

There may be underlying genetic components resulting in a hereditary predisposition to DUL. Such differentials include hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC), which is a rare genetic syndrome caused by autosomal recessive mutations inactivating the FH gene.7 Patients typically present with cutaneous leiomyomas and/or DULs.7 Affected individuals are at a significantly higher risk of developing renal cell carcinomas.8 A gold-standard diagnosis is achieved by genetic tests.8 Earlier investigation includes histology, where a loss of FH staining in tumour samples is thought to be highly predictive of an HLRCC diagnosis.7 Although our patient retained FH staining, her renal history suggests that HLRCC may be included as a possible differential and this requires further follow-up via genetic testing.

IVLs are defined by intravascular proliferation of benign smooth muscle tumours—it is the intravascular component of this pathology that distinguishes it from the confinements of a typical leiomyoma.1 Invasion has mostly been documented in the venous system, particularly in the uterine and pelvic vessels.1 3 4 Although histologically benign, extension into the myocardium and lungs has been reported via the inferior vena cava and pulmonary artery, respectively.1 3 4 This pathology is therefore commonly misdiagnosed as a leiomyosarcoma.3 4

The origin of IVLs is currently up for debate; RNA sequencing analysis has opened the possibility for at least two theories, the first being that IVLs arise from a spread of leiomyomas into the vasculature.9 The second hypothesis is that this pathology originates from the smooth muscle of the vessel walls and is therefore an entity distinct from leiomyomas.10 Clinical findings currently more strongly support the former, as IVLs tend to occur in conjunction with leiomyomas.4 11 Nevertheless, it should be noted that there are a small number of cases reporting IVLs in the absence of leiomyomas.4 11

The affected uterus may be enlarged and will typically have diffuse/focal tumour nodules resembling mucus plugs.1 12 Such lesions may also be observed in the neighbouring vasculature.1 12 The smooth muscle tumours found intravascularly are covered by endothelial cells.1 12 A histological analysis of 13 IVL cases demonstrated that IVLs and normal myometrium stain strongly for desmin, while normal smooth muscle in the vessels was negative.12 This further supports the notion that IVLs may in fact be an extension of leiomyomas, rather than a tumour arising from the walls of the vasculature.

CDLs are a variant of uterine fibroids that appear as an exophytic mass of multinodular tissue resembling the placenta.1 More recently, rarer CDL subsets with an intravascular component and varying degrees of hydropic degeneration have been described.13 They have been termed as cotyledonoid hydropic intravenous leiomyomatosis.13 CDLs usually appear as large, deep-coloured, multinodular lesions that may present with extensive pelvic spread.1 13 The tumour cells have a swirling growth pattern with extensive hyalinisation.13 When associated with intravenous extension, CDLs have similar characteristics to IVLs, which raise further diagnostic challenges.1

Earlier differentiation between benign and malignant disease may be achieved by the presenting features and the advancement of imaging techniques, for example, MRI.6 14 In our case, the patient’s long-standing history of uterine fibroids and her being premenopausal favoured the diagnosis of a leiomyoma. However, a preoperative diagnosis of a low-grade sarcoma could not be ruled out based on these characteristics; the only way to exclude or confirm this would be with careful post-surgical pathological assessment. Therefore, the decision was made to incorporate LEER into the surgical management as this would help achieve complete radical resection and improve the patient’s prognosis.

LEER is a surgical technique used for complete resection of tumours that are extending and fixed into the pelvic sidewall.15 LEER is performed as a combination of at least two of the following procedures: total mesorectal excision, total mesometrial resection and total mesovesical resection.15 In addition to this, resection of the internal iliac vessel system may be performed to ensure complete removal, particularly in instances of lateral tumour fixation.15 16 LEER was introduced in 1999 and was initially used in patients with recurrent cervical cancer who have had previous pelvic irradiation.17 More recently, this technique has been deployed in the surgical management of a variety of tumours extending into the pelvic sidewall, including lateral pelvic sidewall metastasis, uterine sarcomas and deep lateral pelvic endometriosis.18–20

For benign tumours, as those found in our patient, surgical removal is curative and the risk of recurrence is deemed to be low.1 4 However, surgical management may be challenging in cases where there is aggressive disease extension, thus prompting clinicians to take a more conservative approach. Our report demonstrates that the surgical threshold should be lowered for complex cases, as the risk of life-threatening complications, such as emboli, is minimised after excision. This recommendation is not for lack of recognition of the surgical difficulty and postoperative morbidity presented by these complex cases.21–23 It is in these instances that the role of an exhaustive multidisciplinary team is so critical, as demonstrated with our patient whose care benefited from the insight of urologists and the colorectal team, in addition to their gynaecologists.

Beyond diagnostic and management, there is limited literature focusing on the follow-up of such patients. Given the risks associated with cardiac and pulmonary extension, it is paramount that follow-up recommendations are outlined in the near future.

Learning points.

Distinguishing a leiomyosarcoma from a benign leiomyoma is a clinical challenge, given the overlap in presentation and aggressive disease extension. Meticulous histological assessment is paramount for differentiating between benign and malignant disease.

The importance of surgical management in patients with rare leiomyomas should not be understated, as this intervention is curative and reduces the risk of developing life-threatening complications.

Surgical management is challenging for those with aggressive disease spread. We highlight the importance of a multidisciplinary approach with specialist knowledge in the management of such cases.

Footnotes

Contributors: The following authors were responsible for drafting of the text, sourcing and editing of clinical images, investigation results, drawing original diagrams and algorithms, and critical revision for important intellectual content—MK, SE, WG and HSM. The following authors gave final approval of the manuscript—MK, SE, WG and HSM.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Ip PPC, Tse KY, Tam KF. Uterine smooth muscle tumors other than the ordinary leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas: a review of selected variants with emphasis on recent advances and unusual morphology that may cause concern for malignancy. Adv Anat Pathol 2010;17:91–112. 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181cfb901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerdeira AS, Ismail L, Moore N, et al. Retroperitoneal leiomyomatosis: a benign outcome of power morcellation with potentially serious consequences. Lancet 2022;399. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00005-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadeghi N, Addley S, Alazzam M, et al. Intravascular leiomyomatosis; mimicking low grade endometrial sarcoma. J Obstet Gynaecol 2022;42:1564–8. 10.1080/01443615.2021.1963220 Available: https://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2102/101080/0144361520211963220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowie P, Eastwood B, Smyth S, et al. Atypical presentation of intravascular leiomyomatosis mimicking advanced uterine sarcoma: modified laterally extended endopelvic resection with preservation of pelvic neural structures. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e244774. 10.1136/bcr-2021-244774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baschinsky DY, Isa A, Niemann TH, et al. Diffuse leiomyomatosis of the uterus: a case report with clonality analysis. Hum Pathol 2000;31:1429–32. 10.1016/S0046-8177(00)80016-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren H-M, Wang Q-Z, Wang J-N, et al. Diffuse uterine leiomyomatosis: a case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2022;10:8797–804. 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamihara J, Schultz KA, Rana HQ. FH tumor predisposition syndrome. GeneReviews 2020. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1252/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smit DL, Mensenkamp AR, Badeloe S, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families referred for fumarate hydratase germline mutation analysis. Clin Genet 2011;79:49–59. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01486.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X, Wu L, Xu R, et al. Identification of the molecular relationship between intravenous leiomyomatosis and uterine myoma using RNA sequencing. Sci Rep 2019;9:1–9. 10.1038/s41598-018-37452-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W, Wang Y, Chen F, et al. Intravenous leiomyomatosis is inclined to a solid entity different from uterine leiomyoma based on RNA-Seq analysis with RT-qPCR validation. Cancer Med 2020;9:4581–92. 10.1002/cam4.3098 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/20457634/9/13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lan S, Wang X, Li Y, et al. Intravenous leiomyomatosis: a case study and literature review. Radiol Case Rep 2022;17:4203–8. 10.1016/j.radcr.2022.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang L, Lu B. Intravenous leiomyomatosis of the uterus: a clinicopathologic analysis of 13 cases with an emphasis on histogenesis. Pathol Res Pract 2018;214:871–5. 10.1016/j.prp.2018.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan LB, Al-Nafussi A, Beattie G. Cotyledonoid hydropic intravenous leiomyomatosis: a new variant leiomyoma. Histopathology 2002;40:245–52. 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01359.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos P, Cunha TM. Uterine sarcomas: clinical presentation and MRI features. Diagn Interv Radiol 2015;21:4–9. 10.5152/dir.2014.14053 Available: http://www.dirjournal.org/eng/arsivsayi/73/Archive/Issue [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Höckel M. Laterally extended Endopelvic resection (LEER)--Principles and practice. Gynecol Oncol 2008;111:S13–7. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Addley S, Soleymani Majd H. Laparoscopic resection of single site pelvic side wall recurrence 6 years after stage Iiic high grade serous primary peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2021;36:100709. 10.1016/j.gore.2021.100709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Höckel M. Laterally extended endopelvic resection. Novel surgical treatment of locally recurrent cervical carcinoma involving the pelvic side wall. Gynecol Oncol 2003;91:369–77. 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00502-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smyth S, Addley S, Alazzam M, et al. Adamantinoma: metastatic disease masquerading as a gynaecological malignancy. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e241615. 10.1136/bcr-2021-241615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SJ, Kim J, Kim J-W, et al. Safety and feasibility of laterally extended endopelvic resection for sarcoma in the female genital tract: a prospective cohort study. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2022;65:355–67. 10.5468/ogs.22071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Donna MC, Cucinella G, Sozzi G, et al. Surgical neuropelviology: combined sacral plexus neurolysis and laparoscopic laterally extended endopelvic resection in deep lateral pelvic endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2021;28:1565. 10.1016/j.jmig.2021.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addley S, McMullan JC, Scott S, et al. 'Well-leg' compartment syndrome associated with gynaecological surgery: a perioperative risk-reduction protocol and checklist. BJOG 2021;128:1517–25. 10.1111/1471-0528.16749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cowdell I, Smyth SL, Eltawab S, et al. Radical abdomino-pelvic surgery in the management of uterine carcinosarcoma with concomitant para-aortic lymphadenopathy metastasising from anal carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep 2022;15:e252233. 10.1136/bcr-2022-252233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guerrisi R, Smyth SL, Ismail L, et al. Approach to radical hysterectomy for Cervical cancer in pregnancy: surgical pathway and ethical considerations. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022;11:7352. 10.3390/jcm11247352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]