Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) target the PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways and allows the immune system to deliver antitumor effects. However, it is also associated with well-documented immune-related cutaneous adverse events (ircAEs), affecting up to 70–90% of patients on ICI. In this study, we describe the characteristics of and patient outcomes with ICI-associated steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent ircAEs treated with dupilumab. Patients with ircAEs treated with dupilumab between March 28, 2017, and October 1, 2021, at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center were included in this retrospective study, which assessed the rate of clinical response of the ircAE to dupilumab and any associated adverse events (AEs). Laboratory values were compared before and after dupilumab. All available biopsies of the ircAEs were reviewed by a dermatopathologist. Thirty-four of 39 patients (87%, 95% CI: 73% to 96%) responded to dupilumab. Among these 34 responders, 15 (44.1%) were complete responders with total ircAE resolution and 19 (55.9%) were partial responders with significant clinical improvement or reduction in severity. Only 1 patient (2.6%) discontinued therapy due to AEs, specifically, injection site reaction. Average eosinophil counts decreased by 0.2 K/mcL (p=0.0086). Relative eosinophils decreased by a mean of 2.6% (p=0.0152). Total serum immunoglobulin E levels decreased by an average of 372.1 kU/L (p=0.0728). The most common primary inflammatory patterns identified on histopathological examination were spongiotic dermatitis (n=13, 33.3%) and interface dermatitis (n=5, 12.8%). Dupilumab is a promising option for steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent immune-related cutaneous adverse events, particularly those that are eczematous, maculopapular, or pruritic. Among this cohort, dupilumab was well-tolerated with a high overall response rate. Nonetheless, prospective, randomized, controlled trials are warranted to confirm these observations and confirm its long-term safety.

Keywords: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors, Th1-Th2 Balance, Ipilimumab, Nivolumab

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have dramatically increased progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with a variety of cancers, including melanoma, lung, and colorectal.1–3 These agents work by targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways, allowing the immune system to circumvent checkpoints and deliver antitumor effects. However, they are also associated with numerous well-documented immune-related adverse events (irAEs) affecting the skin, gastrointestinal tract, endocrine system, and other organ systems.4 Among these, immune-related cutaneous adverse events (ircAEs) are prevalent, with maculopapular rash and pruritus occurring most frequently.5 Reported incidences of ircAEs with ICI use range up to 70–90%.6 These ircAEs may not only negatively impact patient quality of life but also lead to treatment interruptions and/or discontinuations.4 7

In this study, we describe the characteristics of and patient outcomes with ICI-associated steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent ircAEs treated with dupilumab.

Methods

Patients

Patients from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York, USA, treated with ICI (ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, nivolumab, cemiplimab, atezolizumab, avelumab, or durvalumab), referred to an oncodermatology clinic or evaluated by the inpatient oncodermatology service between March 28, 2017, and October 1, 2021, and who received a prescription for dupilumab were identified via the institutional health information and data management system (n=92). Their electronic health records were retrospectively reviewed, and patients were excluded if their rash was determined to be unrelated to ICI after evaluation by an oncodermatologist (n=8), they never received or used dupilumab after it was prescribed (n=20) or were on an active protocol study that prevented them from being included (n=25).

Study outcomes

The primary objective of this study was to assess the rate of clinical response of the ircAE to treatment with dupilumab. Complete response was defined as documented resolution of ircAE to Grade 0 based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) V.5.0 toxicity grading scale8 or assessments such as ‘completely clear’ or ‘resolved’. Partial response was defined as improvement to CTCAE Grade 1 or assessments of ‘improved’ or ‘markedly improved’. Patients who experienced complete or partial response were considered ‘responders’. Patients who experienced no improvement of their ircAEs, defined as ‘failed treatment’ were considered non-responders.

A secondary objective of this study was to assess any adverse events (AEs) associated with dupilumab use that were reported by patients or documented by their clinician. To corroborate clinical response, absolute eosinophil, lymphocyte, and neutrophil counts, relative eosinophils, lymphocytes, and neutrophils, white blood cell counts, immunoglobulin E (IgE), and interleukin 5 (IL-5) levels were compared before and after treatment with dupilumab. All available biopsies of the ircAEs were reviewed by a dermatopathologist and categorized by a primary inflammatory pattern of spongiotic dermatitis, interface dermatitis, lichenoid dermatitis, perivascular dermatitis, or sparse perivascular infiltrate. The ircAE phenotypes were categorized by an oncodermatologist as eczematous, maculopapular (morbilliform drug eruption), lichenoid, bullous pemphigoid, lichen planus pemphigoides, psoriasiform, or urticarial. Cancer response to antineoplastics prior to initiation of dupilumab, 90 days following initiation of dupilumab, and at the most recent follow-up were also recorded.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics including frequencies, relative frequencies, means, SD and ranges were used to describe the study participants, the characteristics of the ircAEs, and the laboratory measurements for each of the participants. Exact binomial CIs were calculated to estimate the range of response to dupilumab. Χ2 statistics and t-tests were used to evaluate the differences in study measures by dupilumab response category. All analyses were performed with Stata V.16.1MP, Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA.

Results

Demographics and oncologic history

Thirty-nine patients received treatment with dupilumab for ircAEs and were included for analysis (table 1) with a mean age of 68.1±12.4 years and slight male predominance (n=21, 53.8%). Most patients were white (n=32, 82.1%) or Asian (n=5, 12.8%). Patients were most frequently treated with ICI for urothelial or renal cancers (n=10, 25.6%), melanoma and other skin cancers (n=8, 20.5%), and lung cancers (n=6, 15.4%). Prior to developing ircAEs, patients had received treatment with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 blockade monotherapies including pembrolizumab (n=16, 41.0%), nivolumab (n=13, 33.3%), atezolizumab (n=3, 7.7%), and avelumab (n=1, 2.6%), anti-CTLA-4 blockade with ipilimumab (n=1, 2.6%), or combination anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab (n=5, 12.8%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with cancer receiving dupilumab for ircAEs

| All patients (n=39) |

Responders to dupilumab (n=34) | Non-responders to dupilumab (n=5) | P value | ||

| Age | Mean (SD) | 68.1 (12.4) | 69.4 (11.3) | 59.8 (17.8) | 0.11 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sex | Female | 18 (46.2) | 15 (44.1) | 3 (60.0) | 0.51 |

| Male | 21 (53.8) | 19 (55.9) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| Race | White | 32 (82.1) | 27 (79.4) | 5 (100.0) | 0.53 |

| Asian/Indian | 5 (12.8) | 5 (14.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other | 2 (5.1) | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | 3 (7.7) | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 0.49 |

| Non-Hispanic | 36 (92.3) | 31 (91.2) | 5 (100.0) | ||

| Cancer history | Melanoma/skin cancers | 8 (20.5) | 6 (17.7) | 2 (40) | 0.762 |

| HNSCC | 4 (10.3) | 4 (11.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Lung | 6 (15.4) | 5 (14.7) | 1 (20) | ||

| Sarcoma | 4 (10.3) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (20) | ||

| Urothelial/RCC | 10 (25.6) | 9 (26.5) | 1 (20) | ||

| Gynecologic | 3 (7.7) | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (10.3) | 4 (11.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| ICI type | Pembrolizumab | 16 (41) | 16 (47.1) | 0 (0) | 0.179 |

| Nivolumab | 13 (33.3) | 10 (29.4) | 3 (60) | ||

| Ipilimumab/nivolumab | 5 (12.8) | 3 (8.8) | 2 (40) | ||

| Atezolizumab | 3 (7.7) | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Avelumab | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | ||

| Ipilimumab | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) |

HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitors; ircAEs, immune-related cutaneous adverse events; RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

Clinicopathological characteristics

In this cohort (table 2), ircAEs were primarily eczematous (n=16, 41.0%) or maculopapular (n=16, 41.0%). Most patients had CTCAE V.5.0 grade 2 (n=15, 38.5%) or grade 3 (n=14, 35.9%) ircAEs prior to receiving treatment with dupilumab. All patients (n=39, 100%) reported pruritus before receiving dupilumab. Among the patients with available ircAE biopsies (n=23, 59.0%) the most common primary inflammatory patterns identified on histopathological examination were spongiotic dermatitis (n=13, 33.3%) and interface dermatitis (n=5, 12.8%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of ircAEs

| All patients (n=39) | Responders to dupilumab (n=34) | Non-responders to dupilumab (n=5) | P value | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| ircAE phenotype | Eczematous | 16 (41) | 15 (44.1) | 1 (20) | 0.03 |

| Maculopapular | 16 (41) | 15 (44.1) | 1 (20) | ||

| Other | 7 (18) | 4 (11.8) | 3 (60) | ||

| Primary inflammatory pattern | Spongiotic dermatitis | 13 (33.3) | 11 (32.4) | 2 (40) | 0.121 |

| Interface dermatitis | 5 (12.8) | 5 (14.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Lichenoid dermatitis | 2 (5.1) | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | ||

| Perivascular dermatitis | 2 (5.1) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (20) | ||

| Sparse perivascular infiltrate | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | ||

| No biopsy | 16 (41) | 15 (44.1) | 1 (20) | ||

| Baseline ircAE CTCAE V.5.0 grade | 1 | 3 (7.7) | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 0.671 |

| 2 | 15 (38.5) | 12 (35.3) | 3 (60) | ||

| 3 | 14 (35.9) | 13 (38.2) | 1 (20) | ||

| Not recorded | 7 (18) | 6 (17.7) | 1 (20) | ||

| Pruritus | No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Yes | 39 (100) | 34 (100) | 5 (100) | ||

| Baseline pruritus CTCAE V.5.0 grade | 1 | 4 (10.3) | 4 (11.8) | 0 (0) | 0.785 |

| 2 | 8 (20.5) | 7 (20.6) | 1 (20.0) | ||

| 3 | 10 (25.6) | 8 (23.5) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| Not recorded | 17 (43.6) | 15 (44.1) | 2 (40.0) |

CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; ircAEs, immune-related cutaneous adverse events.

Clinical response to Dupilumab

A median of 8 dupilumab injections (1–42) were given per patient. Thirty-four of 39 patients (87%, 95% CI: 73% to 96%) responded to dupilumab (table 1). Among these 34 responders to dupilumab, 15 (44.1%) were complete responders with total ircAE resolution and 19 (55.9%) were partial responders with significant clinical improvement or reduction in severity to CTCAE Grade 1. Response was documented after a median of 41.5 days (7–161) of dupilumab treatment, with complete responders and partial responders experiencing improvement after a median of 56 days (15–161) and 30 days (9–147), respectively. Partial and complete responders received a median of 2 (1–6) and 4 dupilumab injections (1–10) prior to their respective responses. Two patients stopped responding after initially improving, while the remaining 32 responders did not experience recurrence or worsening of their ircAEs after control with dupilumab. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, race, ethnicity, cancer history, or ICI type between responders and non-responders to dupilumab.

Nearly half of patients treated with dupilumab were able to continue their ICI without interruption (n=18, 46%). Nine patients had already completed their ICI at the time of dupilumab treatment. Twelve patients discontinued their ICI as a result of cutaneous (n=10) or non-cutaneous toxicities (n=2). Among the 10 patients who discontinued as a result of ircAEs, 1 patient was rechallenged successfully following treatment with dupilumab, while the remaining 9 patients did not get rechallenged for various reasons, including progression of their tumor (n=4), no evidence of tumor at the time of ICI discontinuation (n=4), and development of another primary cancer requiring a new regimen (n=1).

Changes in ircAE management before and after dupilumab

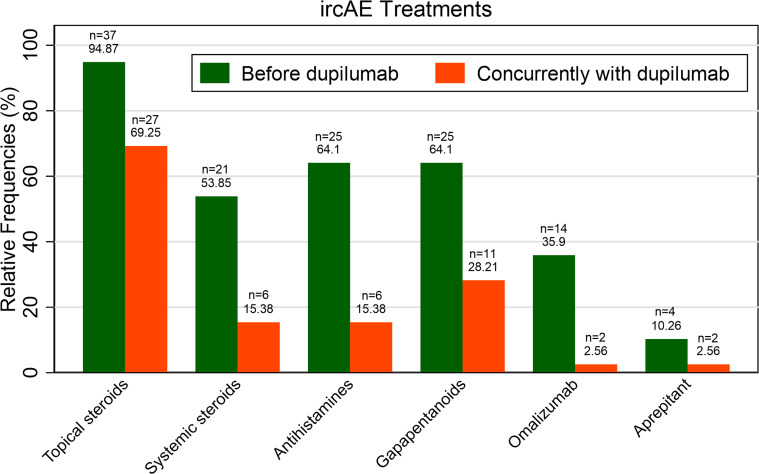

Prior to intervention with dupilumab, nearly all patients (n=37, 94.9%) had failed treatments with topical steroids and over half (n=21, 53.9%) received systemic steroids for their ircAEs (figure 1). More than half of patients had also received antihistamines (n=25, 64.1%) and/or gabapentinoids (n=25, 64.1%) prior to dupilumab. Although most patients continued supportive treatment with topical steroids (n=27, 69.3%), few (n=6, 15.4%) continued to receive systemic steroids along with dupilumab. Most patients (n=21) did not require continued supportive treatment with systemic therapies such as antihistamines, gabapentinoids, omalizumab, or aprepitant after initiating dupilumab.

Figure 1.

Treatments used to manage ircAEs before and after intervention with dupilumab. ircAE, immune-related cutaneous adverse event.

Tolerability of dupilumab

Patients received standard dosing of dupilumab, with a 600 mg loading dose followed by 300 mg administered subcutaneously every 2 weeks. Of the 39 patients treated with dupilumab in this cohort, only 1 patient (2.6%) discontinued therapy due to an adverse reaction associated with dupilumab, specifically injection site reaction. Two patients (5.1%) reported eye irritation after starting dupilumab but received supportive care and continued with dupilumab treatment.

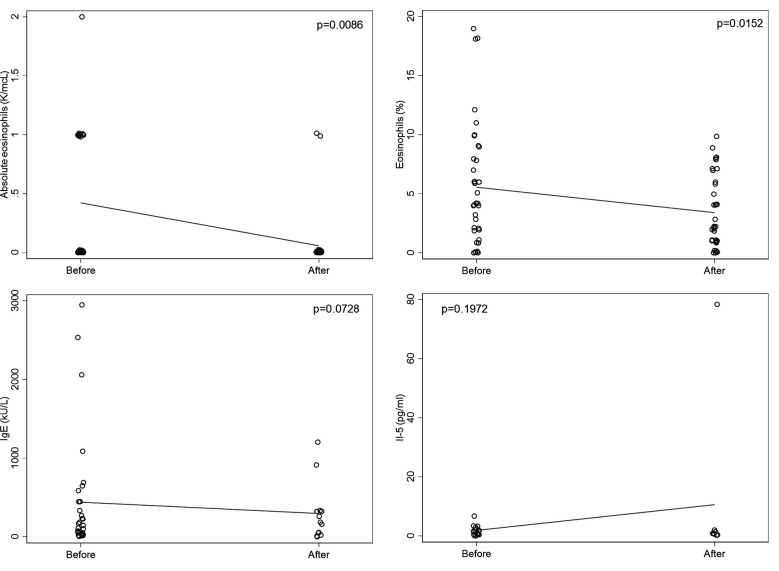

Changes in blood eosinophils and total serum IgE levels

Among 38 patients with available complete blood count with differential within 30 days prior to starting treatment with dupilumab, the average absolute eosinophil count was 0.4 K/mcL and 31 had measures within the normal range (0.0–0.7 K/mcL). Thirty-five of these patients had laboratory tests re-drawn after treatment with dupilumab and had a significantly lower average eosinophil count of 0.2 K/mcL. The mean paired difference was −0.2 K/mcL (p=0.0086). In these same patients, relative eosinophils were 5.5% (normal range: 0.0–4.9%) prior to starting dupilumab and significantly lower at 3.3% after treatment with dupilumab. The mean paired difference was −2.6% (p=0.0152). Average baseline total serum IgE levels were elevated at 439.3 kU/L (normal range: ≤214 kU/L). Among 11 patients with both baseline and follow-up laboratory values, after treatment with dupilumab and follow-up, IgE levels decreased by an average of 372.1 kU/L (p=0.0728). There were no significant differences in absolute and relative lymphocyte or neutrophil, or IL-5 values before and after treatment with dupilumab (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pre to post dupilumab changes in blood eosinophils, total serum IgE, and IL-5 of patients with ircAEs. Solid lines represent the trajectories of the means from before to after treatment with dupilumab. IgE, immunoglobulin E; IL-5, interleukin 5; ircAEs, immune-related cutaneous adverse events.

Antitumor response

In total, 17 patients (43.6%) experienced progression of their cancer at any point after dupilumab initiation (online supplemental figure). Of these patients, 12 had previously received systemic steroids for their ircAEs. Time to next treatment for these patients was a median of 562 days (69–2033).

jitc-2023-007324supp001.pdf (37.1KB, pdf)

Discussion

Dupilumab for steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent ircAEs

In 39 patients with ircAEs refractory to topical and/or systemic steroids, 35 patients demonstrated either partial or complete response to intervention with dupilumab. Considering that 70–90% of patients on ICI experience ircAEs,6 this response rate of nearly 90% is clinically significant and demonstrates that dupilumab is a promising treatment option and alternative to steroids for ircAEs. The majority of patients in our cohort were treated for ircAEs with primarily eczematous or maculopapular phenotypes and pruritus, although other ircAEs consistent with lichenoid dermatitis, bullous pemphigoid, and lichen planus pemphigoides were also responsive to dupilumab.

First-line treatments for high-grade ircAEs typically include high-potency topical steroids, oral antihistamines, and gabapentinoids such as pregabalin or gabapentin.9 10 For persistent or higher-grade ircAEs, systemic steroids are typically added.9 10 However, patients may also develop steroid-resistant or steroid-dependent irAEs, including ircAEs, that are refractory to steroid treatments or recur when steroids are tapered.11 12 After intervention with dupilumab, fewer patients required additional supportive therapies such as topical steroids and systemic steroids. This is especially important given significant toxicity associated with systemic steroids including infections, hyperglycemia, osteoporosis; and emerging evidence suggesting that long-term or high-dose systemic steroid use may limit ICI efficacy.13 14 In this context, recent guidelines,9 10 based on expert opinion, have recommended the use of steroid-sparing targeted immunomodulatory agents including omalizumab, which has been shown to reduce ICI-associated pruritus.15 Our data suggest dupilumab is a promising steroid-sparing option for ircAEs, particularly those of eczematous or maculopapular phenotypes, with likely favorable safety, supporting what has been reported in small studies of ICI-associated rash (n=2)12 and ICI-associated bullous pemphigoid.16–19

Dupilumab mechanism of action

Pathophysiology of ircAEs has not been fully elucidated but is thought to be a result of a combination of factors including shared epitopes between malignant tumors and skin,6 promotion of T-cell responses with resultant self-reactivity and autoimmunity,20 and enhanced Th1, Th2, and Th17 signaling as a result of PD-1 blockade.21 Interestingly, both eczematous or maculopapular ircAE phenotypes have been associated with eosinophilia,7 and eosinophilia and elevated IgE serum level have been associated with ircAE severity.12 Although average absolute eosinophil counts were not elevated at baseline in our cohort and relative eosinophils were only slightly elevated, both values decreased significantly after treatment with dupilumab and IgE levels downtrended, although this did not reach significance. Dupilumab is an IgG4 monoclonal antibody that binds to the IL-4 receptor alpha chain of IL-4 and IL-13, resulting in specific targeting of the Th2 axis and is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis.22 It may alleviate ircAEs by reducing Th2 axis activation and inhibiting IgE production, both of which play important roles in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis and bullous pemphigoid.22–24

Safety of dupilumab

Dupilumab has a favorable long-term safety and adverse effect profile. An analysis of 2677 patients with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab for up to 4 years found that the most common adverse events included nasopharyngitis, exacerbation of atopic dermatitis, upper respiratory tract infections, oral herpes, conjunctivitis, injection-site reactions, and headaches.25 In our cohort, only conjunctivitis and injection-site reactions were reported and only one patient discontinued dupilumab as a result of injection-site reactions. Additionally, an analysis of patients receiving treatment with dupilumab for atopic dermatitis found no association between dupilumab use and short-term risk of developing a primary or recurrent malignancy,26 with the exception of a small case series of possible cutaneous T-cell lymphoma worsening post dupilumab.27 Furthermore, the International Eczema Council recommends the use of dupilumab as a first-line therapy for atopic dermatitis in patients with history of malignancy.28 Although most patients who discontinued their ICI regimen were not subsequently rechallenged, the one patient who was rechallenged did not experience recurrence or worsening of their skin toxicity following ICI re-initiation, nor tumor progression, highlighting the potentially beneficial therapeutic role of IL-4 blockade in oncologic care.

While a subset of our cohort experienced cancer progression at any point after dupilumab treatment, all but one of these patients had metastatic disease at baseline, 52.9% had ongoing tumor progression prior to initiation of dupilumab, and 70.6% of those who progressed had also previously received systemic steroids. Systemic steroids greater than 7.5 mg of prednisone per day have been associated with reduced antitumor response.14 Given the prior systemic steroid exposure in most patients who progressed with known associated reduced antitumor response, the heterogenous cancer types and lack of a control group, further prospective investigation is needed to determine dupilumab effect on the time to oncologic treatment failure.

Limitations

Conclusions drawn by this study may be limited by its retrospective design, moderate sample size, heterogeneous cancer diagnoses, and prior exposure to systemic steroids. Additionally, patients in this study had eczematous or maculopapular ircAEs, so results may not be generalizable to all ircAEs due to heterogeneity.

Conclusions

Dupilumab is a promising option for steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent immune-related cutaneous adverse events, particularly those that are eczematous, maculopapular, or pruritic. Among this cohort, dupilumab was well-tolerated with a high overall response rate. Nonetheless, prospective, randomized, controlled trials are warranted to confirm these observations and confirm its long-term safety.

Acknowledgments

We thank Galina Yusim, data engineer, who assisted with collection of data from the institutional information systems service (Dataline).

Footnotes

Contributors: AM-SK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing, Visualization. SG: Validation, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing, Visualization. JS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation. APM: Validation, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing, Visualization. SWD: Software, Formal Analysis, Writing, Visualization. AG: Investigation, Writing. ECH: Investigation, Writing. YJ: Investigation, Writing. LK: Investigation, Writing. EAQ: Investigation, Writing. PC: Investigation, Writing. MEL: Investigation, Writing. AM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing, Visualization, Supervision.

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30-CA008748 made to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Competing interests: YJ receives research funding from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cycle for Survival, Department of Defense, Eli Lilly, Fred’s Team, Genentech/Roche, Merck, NCI, RGENIX, is on the advisory board or serves as a consultant for Amerisource Bergen, Arcus Biosciences, AstraZeneca, Basilea Pharmaceutica, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Geneos Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Imedex, Imugene, Lynx Health, Merck, Merck Serono, Mersana Therapeutics, Michael J. Hennessy Associates, Paradigm Medical Communications, PeerView Institute, Pfizer, Research to Practice, RGENIX, Seagen, Silverback Therapeutics, Zymeworks Inc., and has stock options with RGENIX. EAQ receives royalties from UpToDate. PC is a consultant for Merck, Immunocore, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer and has equity interest in Rgenix. MEL has a consultant role with Johnson and Johnson, Novocure, QED, Bicara, Janssen, Novartis, F. Hoffmann-LaRoche AG, EMD Serono, AstraZeneca, Innovaderm, Deciphera, DFB, Azitra, Kintara, RBC/La Roche Posay, Trifecta, Varsona, Genentech, Loxo, Seattle Genetics, Lutris, On Quality, Azitra, Roche, Oncoderm, NCODA, and Apricity. MEL receives research funding from Lutris, Paxman, Novocure, J&J, US Biotest, OQL, Novartis, and AstraZeneca. AM receives research funding from Incyte Corporation and Amryt Pharma; consults for Blueprint Medicines, ADC Therapeutics, Alira Health, OnQuality, Protagonist Therapeutics, and Janssen; and receives royalties from up to date.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Research data are stored in an institutional repository and can be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted with institutional review board approval (MSKCC Protocol #16–458).

References

- 1. Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2020–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1910231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Five-year survival with combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1535–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa1910836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. André T, Shiu K-K, Kim TW, et al. Pembrolizumab in Microsatellite-instability–high advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2207–18. 10.1056/NEJMoa2017699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune Checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol 2015;26:2375–91. 10.1093/annonc/mdv383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, et al. Immune Checkpoint inhibitor-related Dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;83:1255–68. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang E, Kraehenbuehl L, Ketosugbo K, et al. Immune-related cutaneous adverse events due to Checkpoint inhibitors. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2021;126:613–22. 10.1016/j.anai.2021.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune Checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and Immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol 2018;19:345–61. 10.1007/s40257-017-0336-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Cancer Institute . Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0. Bethesda, Maryland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Apalla Z, Nikolaou V, Fattore D, et al. European recommendations for management of immune Checkpoint inhibitors-derived Dermatologic adverse events. The EADV task force 'Dermatology for cancer patients' position statement. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022;36:332–50. 10.1111/jdv.17855 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/14683083/36/3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brahmer JR, Abu-Sbeih H, Ascierto PA, et al. Society for Immunotherapy of cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immune Checkpoint inhibitor-related adverse events. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9. 10.1136/jitc-2021-002435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luo J, Beattie JA, Fuentes P, et al. Beyond steroids: immunosuppressants in steroid-refractory or resistant immune-related adverse events. J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:1759–64. 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Phillips GS, Wu J, Hellmann MD, et al. Treatment outcomes of immune-related cutaneous adverse events. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:2746–58. 10.1200/JCO.18.02141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Horvat TZ, Adel NG, Dang T-O, et al. Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with Melanoma treated with Ipilimumab at Memorial Sloan Kettering cancer center. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3193–8. 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Faje AT, Lawrence D, Flaherty K, et al. High-dose glucocorticoids for the treatment of Ipilimumab-induced Hypophysitis is associated with reduced survival in patients with Melanoma. Cancer 2018;124:3706–14. 10.1002/cncr.31629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barrios DM, Phillips GS, Geisler AN, et al. Ige blockade with Omalizumab reduces pruritus related to immune Checkpoint inhibitors and anti-Her2 therapies. Ann Oncol 2021;32:736–45. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klepper EM, Robinson HN. Dupilumab for the treatment of Nivolumab-induced Bullous Pemphigoid: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J 2021;27. 10.5070/D327955136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mihailescu ML, Brockstein BE, Desai N, et al. Successful reintroduction and continuation of Nivolumab in a patient with immune Checkpoint inhibitor-induced Bullous Pemphigoid. Current Problems in Cancer: Case Reports 2020;2. 10.1016/j.cpccr.2020.100031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khazaeli M, Grover R, Pei S. Concomitant Nivolumab-associated Grover disease and Bullous Pemphigoid in a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol 2023;50. 10.1111/cup.14383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bur D, Patel AB, Nelson K, et al. A retrospective case series of 20 patients with Immunotherapy-induced Bullous Pemphigoid with emphasis on management outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022;87:1394–5. 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yoest JM. Clinical features, predictive correlates, and pathophysiology of immune-related adverse events in immune Checkpoint inhibitor treatments in cancer: a short review. Immunotargets Ther 2017;6:73–82. 10.2147/ITT.S126227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Okiyama N, Tanaka R. Immune-related adverse events in various organs caused by immune Checkpoint inhibitors. Allergol Int 2022;71:169–78. 10.1016/j.alit.2022.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harb H, Chatila TA. Mechanisms of Dupilumab. Clin Exp Allergy 2020;50:5–14. 10.1111/cea.13491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hashimoto T, Kursewicz CD, Fayne RA, et al. Pathophysiologic mechanisms of itch in Bullous Pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;83:53–62. 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abdat R, Waldman RA, de Bedout V, et al. Dupilumab as a novel therapy for Bullous Pemphigoid: A multicenter case series. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;83:46–52. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beck LA, Deleuran M, Bissonnette R, et al. Dupilumab provides acceptable safety and sustained efficacy for up to 4 years in an open-label study of adults with moderate-to-severe Atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2022;23:393–408. 10.1007/s40257-022-00685-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Owji S, Ungar B, Dubin DP, et al. No association between Dupilumab use and short-term cancer development in Atopic dermatitis patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022. 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Espinosa ML, Nguyen MT, Aguirre AS, et al. Progression of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma after Dupilumab: case review of 7 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;83:197–9. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Drucker AM, Lam M, Flohr C, et al. Systemic therapy for Atopic dermatitis in older adults and adults with Comorbidities: A Scoping review and international Eczema Council survey. Dermatitis 2022;33:200–6. 10.1097/DER.0000000000000845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2023-007324supp001.pdf (37.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Research data are stored in an institutional repository and can be shared upon request to the corresponding author.