Abstract

Background: Transitions of care represent a vulnerable time for patients where unintended therapeutic changes are common and inadequate communication of information frequently results in medication errors. Pharmacists have a large impact on the success of patients during these care transitions; however, their role and experiences are largely absent from the literature.

Objectives: The purpose of this study was to gain a greater understanding of British Columbian hospital pharmacists’ perceptions of the hospital discharge process and their role in it.

Methods: A qualitative study utilizing focus groups and key informant interviews of British Columbian hospital pharmacists was conducted from April to May 2021. Questions asked during interviews were developed following a detailed literature search and included questions regarding the use of frequently studied interventions. Interview sessions were transcribed and then thematically analyzed using both NVivo software and manual coding.

Results: Three focus groups with a total of 20 participants and one key informant interview were conducted. Six themes were identified through data analysis: (1) overall perspectives; (2) important roles of pharmacists in discharges; (3) patient education; (4) barriers to optimal discharges; (5) solutions to current barriers; and (6) prioritization.

Conclusions and Relevance: Pharmacists play a vital role in patient discharges but due to limited resources and inadequate staffing models, they are often unable to be optimally involved. Understanding the thoughts and perceptions of pharmacists on the discharge process can help us better allocate limited resources to ensure patients receive optimal care.

Key Words: patient discharge, clinical pharmacist, seamless care

INTRODUCTION

Transitions of care refer to points in a patient’s journey where they are moving from one level of care to another, including being discharged from the hospital back to the community. These time points leave the patient vulnerable as during their stay in hospital, many of their chronic medication therapies may have been discontinued or changed without this being clearly communicated to patients or their community care providers. This can lead to medication-related problems, estimated to be the most significant cause (~40%) of all hospital readmissions, with approximately 14% of these being considered preventable.1

Factors contributing to medication-related problems following hospital discharge include: adverse drug events; subpar information communication with patients and community care providers; unintended medication changes; intentional and unintentional medication nonadherence; and inappropriate medication prescribing.1,2 Because medication-related problems pose a burden to patients and the healthcare system, it is vital to identify the most optimal way to discharge patients from an inpatient setting to increase their chances of success as an outpatient.

Interventions related to optimizing discharge medication practices, which have been evaluated in the literature, include: medication reconciliation on admission/discharge; patient education/counselling; post-discharge follow up in person or via phone; and coordinating care with an interdisciplinary care team.1-12 Some studies have found that interventions led by hospital pharmacists can improve patient outcomes.1-3,11,12 For instance, pharmacy-led medication reconciliation interventions effectively reduce medication discrepancies.3.

Overall, hospital pharmacists can play a pivotal role in optimizing patient discharges; however, an understanding of their perception of the discharge process is largely missing from the literature. The purpose of this study was to gain insight into hospital pharmacists’ perceptions of their roles in hospital discharge and their thoughts on the optimal discharge practices related to medications.

METHODS

This was a qualitative study that used focus group methodology. For potential participants that were wanting to participate but unable to attend the focus group sessions the option of participating in an interview was provided. The study (ID # H21-00117) was approved by the University of British Columbia (UBC) Behavioural Ethics Board and Harmonized Partner Boards (Fraser Health, Interior Health, Northern Health and Island Health).

Pharmacists working in British Columbia (BC) at the Northern Health Authority, Island Health Authority, Interior Health Authority or Lower Mainland Pharmacy Services were invited to participate in the study. Clinical coordinators within each of the health authorities were asked to send out an email invitation to their pharmacist staff. Also, a purposive snowballing method, as described by Gregory and Zubin (2019)13, was used to identify additional prospective participants.

In BC, the role of hospital pharmacists varies depending on their site location. Pharmacists may work primarily in the dispensary or on hospital units providing clinical care. Some pharmacists may also have the responsibility of verifying orders in a decentralized setting while also providing clinical pharmacy services. For pharmacists that provide clinical services these may include but not be limited to rounding with providers, therapy optimization, clinical monitoring, and patient education. Depending on the hospital site and staffing levels, pharmacists may be available in some sort of capacity 7 days a week. For the purposes of this study, pharmacists were eligible to participate in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) employed by a hospital in BC; (2) provided direct patient care for most of their work time; (3) involved in the patient discharge process; (4) able to read and converse in English; (5) able to give informed consent; and (6) had computer and internet access. Pharmacists who work primarily in a community setting, pharmacy technicians, assistants and pharmacists who did not provide patient care were excluded. Participants received a $10.00 gift card honorarium for their participation.

The interview questions (Appendix 1) were developed following a detailed literature search and further refined by the research team and key stakeholders who were all pharmacists with experience practicing in a hospital setting and participating in the patient discharge process. The target sample size of each focus group session was 6-8 participants, with all interview sessions occurring after work hours via Zoom®. One of the study team members acted as the focus group facilitator (K.D., or M.L.) and the remainder of the study team would observe (S.L., C.I.). In addition to observing, S.L. also recorded the sessions and took notes.

Both K.D. and M.L. have experience in qualitative research and focus group methodology. Because of their background in clinical pharmacy K.D., M.L. and C.I are familiar and experienced with the patient discharge process.

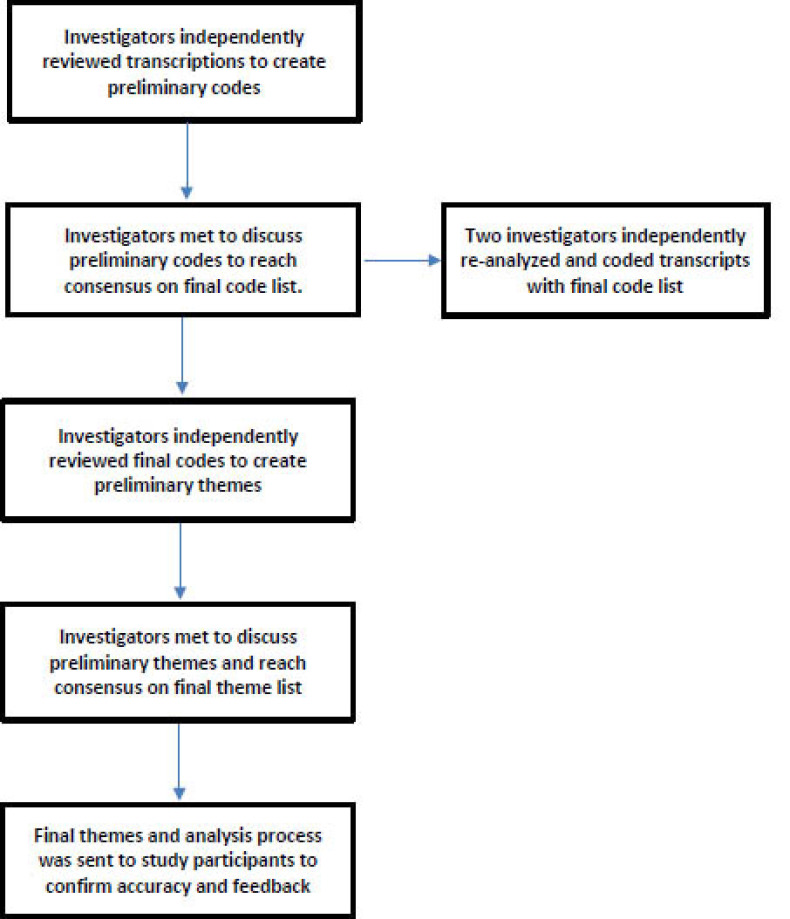

Interview transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis (Figure 1).14 First, the transcripts were coded one at a time and codes and ideas were created from the transcripts by the investigators independently. Two investigators (S.L. and C.I.) used NVivo® software (https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/about/nvivo) for coding and two investigators (K.D. and M.L.) coded manually. After completion of the individual coding, the investigators met to compare their coding results and discussed any differences until consensus was reached, before moving on to the next transcript. The process was repeated until all four focus group transcripts were coded and a final codes list was developed. Next, S.L. and C.I. independently reanalysed all four transcripts using the final codes list to ensure accuracy. The investigators then independently used the final codes list to create overall themes and then met to discuss differences until a consensus was reached for a final themes list. Member checking was then done with participants given the opportunity to review the final themes anonymously within Qualtrics®. Participants were provided a description of each theme and asked, “Does this theme resonate with you?” with the options “yes” or “no” and the option to provide written feedback (Appendix 2).

Figure 1.

Thematic Analysis Process

RESULTS

In total, 23 pharmacists consented to participate in the study and completed the anonymous demographic survey (Table 1). Of these 23, two pharmacists did not participate in an interview or focus group (one due to a last-minute scheduling conflict and the other for an unknown reason).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of participants who consented to the study (N=23)

| Characteristic | No. of Participants (%) |

| Interview Type | |

| Focus Group 1 | 7 (30) |

| Focus Group 2 | 6 (26) |

| Focus Group 3 | 7 (30) |

| Individual Interview | 1 (4) |

| Did not participate | 2 (9) |

| Highest Level of Training | |

| Post-Graduate PharmD | 10 (43) |

| Year 1 Residency | 7 (30) |

| BSc Pharmacy | 3 (13) |

| Other1 | 3 (13) |

| Setting/Specialization 2 | |

| Internal/General Medicine | 13 (57) |

| Surgery | 6 (26) |

| Renal Transplant | 2 (9) |

| ICU/ HAU/CCU | 4 (17) |

| Cardiology | 2 (9) |

| Psychiatry/Mental Health | 3 (13) |

| Other | 6 (26) |

| Primary Setting (multiple vs. single) | |

| Multiple Specialities | 10 (43) |

| Single Specialty | 13 (57) |

| Liaise with Community Pharmacies Post Discharge? | |

| Yes | 23 (100) |

| No | 0 |

| HCP’s Have Defined Roles in Patient Discharge? | |

| Yes | 12 (52) |

| No | 11 (48) |

| Median (IQR) | |

| Years of Training | 4 (8.9) |

| Number of Beds in Hospital | 432.5 (138) |

| Patients per Pharmacist | 27 (14.5) |

| Average # of Discharges per Week | 10 (11) |

| % Of Discharges Pharmacists Participate in | 72.5 (37.5) |

IQR= Interquartile Range; ICU= Intensive Care Unit; HAU= High Acuity Unit;

CCU= Critical Care Unit

Other degrees were: Post-Grad Diploma in Clinical Pharmacy, Year 2 Residency, and did not specify.

Participants had the option of choosing more than one setting/specialization.

From April to May 2021, 3 focus groups and 1 individual interview was conducted. The interviews ranged from 40-75 minutes in length. Thematic analysis of the interview transcripts revealed 24 codes that were organized into 6 themes (Table 2): 1) Overall perspectives on the discharge process; 2) Prioritization; 3) Important roles of a pharmacist in discharges; 4) Patient education; 5) Barriers to optimal discharges; and 6) Solutions to current barriers. By the analysis of the third focus group session, it appeared that data saturation was reached as the majority of ideas around major themes were consistent with previous interview sessions, with the exception of new ideas around solutions to barriers.

Table 2.

Final Themes, Description and Relevant Codes

| Theme | Description | Codes (frequency) | Quotes |

| Overall perspectives on the discharge process | Optimal patient discharge process is multifaceted and is a team approach. Clinical pharmacists in particular have expertise to play a central role in the discharge process which is recognized by other HCPs. |

|

“I was just trying to think of how to put it into words but essentially, it’s what we’ve really discussed throughout this entire discussion today. Just being able to have like pharmacists lay eyes on the discharge prescription, making sure everything makes sense. Having the opportunity to talk to the patient or their caregivers, ensuring that they have at least some understanding of the medications that we’ve made changes to or we have started or discontinued. And sort of doing that over multiple days, as opposed to bombarding them with information right before they go. And just ensuring that they can physically get the medication with the coverage issues, as well as our community pharmacy colleagues having the drug or having had time to prepare the meds. Essentially what we’ve all said really. But that’s ideally what I would picture like a ideal discharge process to look like.”- Participant #I22 |

| Prioritization | Because pharmacists cannot be involved in all discharges, they prioritize patients for discharge interventions based on criteria such as complexity, number of medication changes, high risk medications, and adverse drug related admission. |

|

“I tend to prioritize patients definitely who have new medications started in the hospital cuz I literally new ARVs because there’s a lot of medication counselling and drug interactions to review and a lot of logistical stuff to consider in terms of medication supply and where are they going to pick up their ARVs and that sort of thing. So, I do focus a lot of my time on those patients in particular. Or the patients with new medications that require quite a bit of counselling.” -Participant #I32“Yeah so, I would say similar to “I32” as well any patients that have a new diagnosis or previously, they were on no medications and then all of a sudden got a new diagnosis and started on new medications then I would prioritize them. Just cuz I know they would benefit from a lot of counselling and patient education”- Participant #I31 |

| Important roles of a pharmacist in discharges | Pharmacists are the optimal HCP to complete the medication reconciliation and discharge prescriptions, and communicate discharge plans to the patients’ health care team (e.g., GP, community pharmacy, mental health team and other primary care team members). An important pharmacist discharge role is to address practical barriers to the patient actually receiving their medications post-discharge. These include: financial barriers such as fair Pharmacare and special authority arrangements; ensuring patients can pick up/access a supply of their medications; and ensuring special arrangements such as daily dispense and compliance aids are in place. |

|

“Yeah, I’d say, id add on to that and say liaising with community pharmacy is often quite important like as “I23” was mentioning, daily dispense patients, giving them a heads up of what’s going on. I mean these are their patients just as much as they are ours. Having that put on hold, that actually helps in the end as well because you’ve been in communication. Yeah, so I would say something like that.”- Participant #I25 “I think a lot of them have already been said in terms of, in regards to my experience within the mental health population, I think if there is any barrier at all to the patient picking up their medication it’s done. Like if they are under the mental health act, they weren’t going to get it. So, if there is no coverage, there’s no plan C or plan G, if the pharmacy didn’t get the prescription and they have to wait for the fax, you know, if there was some sort of error on the prescription as “I22” and “I25” have said and they have to clarify, any of those things can be a barrier to a person not picking it up and being basically re-admitted maybe within like 24-48 hours.” -Participant #I24 “I think it depends on the patient. I feel that some of the simpler discharges definitely the physicians can do, but there’s the complex discharges where as previously mentioned, where medications have been changed significantly throughout the admission, I personally like to be involved in those and I think that just for like logistics in terms of all the right people to communicate with the community pharmacy, what’s been stopped what’s been changed and communicating with the patient, I think the pharmacist is probably the more appropriate person to be involved in the complex discharges.”- Participant #I47 |

| Patient Education | Optimal discharge education is started early in the hospital stay, repeated frequently and supplemented by customized patient-specific written/printed instructions. Further, including patient’s family and friends in the educational process can be beneficial. Although, patient education pertaining to medications is important, but pharmacists lack the time to consistently provide this for all patients. Unfortunately, some current discharge education processes are suboptimal and/or inefficient. |

|

“Yeah, just to echo what the others have said already so definitely the patient education I find is really helpful. A lot of times when we relay the information the patients might look like they understand but when I use like things like teach back method, they might not be able to answer the questions we had talked about earlier. So, I think education would be a big thing. And then also for the discharge prescriptions, stating which medications have been changed or newly started. I think those ones are, what I perceive to be important things.”- Participant #I42 “I think that patient education isn’t something that necessarily has to happen always at discharge. The literature is a little bit unclear about when I think the best time is to preform education. Probably it’s said a number of times and including after discharge? Based on what I’ve seen at least in the literature. So, something that I’ve attempted to do is provide education earlier than very last minute because I often find that patients are so focused on leaving and their family members, they’re just focused on the logistics and not at all about actually what’s happened, what their medications are. So, finding that right time for education.”- Participant #I46 |

| Barriers to optimal discharges | Insufficient time, lack of staffing resources and excessive workload prevents pharmacists from being optimally involved in patient discharges. Further, system factors such as unplanned or short-notice discharges and variable patient volumes adversely affect the quality of discharge arrangements. Due to these issues, pharmacists often have to provide less than optimal discharges. |

|

“Yeah, I feel I think, I was already aware of this from my own role and the role of my colleagues in patient discharge but this discussion just kind of further solidified the vital role in patient discharge that pharmacists play. And really highlighted to me how much we are really being spread thin and as “I23” said we could some days have role in just patient discharges. Were being spread in so many different directions especially with Covid and taking on new responsibilities as well depending on which role you’re in and which patient population you’re following. So, it’s a challenge. So, I think that pharmacists have a huge role in patient discharge but again hard to make optimal time for our patients on a day in and day out basis. Depending on how many discharges we’re faced with.”- Participant #I26 “I know one challenge I’ve faced is when you have to do like you said a last minute discharge and the patient doesn’t speak the language and you’re trying to figure out how to communicate and then usually you would have family members around but with COVID now you don’t have as many family members available. So, sometimes you may have to Zoom with them on the phone and it’s very very challenging to do a discharge virtually with this 3-way type of communication.”- Participant #I45 “Just to add to like “I42’s” comment about like coming in on a Monday and discharging someone, similar to like internal medicine there’s a lot of rotating, so you, if it’s like your first day working with that team, getting to know that patient, and then you’re told that you have to discharge that patient so now you have a finite amount of time to get to know the patient, quickly work up the patient and discharge that patient. So that can sometimes be a little bit stressful as well.”- Participant #I47 |

| Solutions to Current Barriers | Pharmacists identify a variety of potential solutions to optimize the discharge process. Specifically, additional pharmacy staffing, and at minimum reviewing discharge medication reconciliation and/or discharge prescriptions to reduce medication errors. |

|

“Yeah, I think if there was a lot of time (laughs) a lot of free time that was allotted that would be the ideal situation. I think another thing would be if there was enough time that if everyone was able to leave like a short note or something that needs to be followed up. So, I know like sometimes when we write on our discharge prescription like discontinue metoprolol but then we might not say was bradycardic, had a fall, came into the hospital. It would be nice to say like oh new ramipril, please like follow up or ask patient to monitor blood pressure or whatever just something that we can kind of communicate to the pharmacy or whoever’s following up just to make sure that there’s a little bit more communication piece rather than just sending the script cuz I feel like a lot of times, having like worked as a student in a community pharmacy in receiving discharge prescriptions, if there’s questions or anything, it was always like, oh no I don’t know how we’re gonna contact the team or I dunno how we’re gonna reach the ward or the doctor that wrote this prescription. So, that’s something that could be improved on, is opening that communication piece so that we can have kind of a two way street in terms of having a little bit more detail to accompany the discharge when they go to the pharmacy”- Participant #I31 “Although I do think that it should be give and take, I do think that it’s helpful to have well defined roles, and then when we’re not able to, to let each other know and obviously to have that communication. But I think where gaps happen is when each of us thinks that another person is doing the thing, like okay I thought you were going to get the special authority or I thought you had it. So, I think having whatever you decide within your team works as the divide, I don’t think it should always be the same for every team and every situation. But, clearly knowing what everyone’s responsible for and then of course if you’re not there or if you can’t make it or if you’re too busy then passing it over to someone else.”- Participant #I24 |

Overall perspectives on the discharge process

The first theme identified was that pharmacists have some consistent, overall perspectives or philosophies about the patient discharge process. Specifically, pharmacists tend to agree that patient discharges are a team-based process with multiple components.

“I consider a conjoined effort… I believe the pharmacist and the doctor should be involved in the discharge prescriptions…because I know things about the prescriptions that the prescriber doesn’t or vice versa.”-Participant

Further, most participants agreed that hospital pharmacists have a unique expertise related to ensuring the success of patients post discharge, which is recognized and valued by other healthcare team members. Because of this, hospital pharmacists should play a central role in the patient discharge process.

Prioritization

The next major theme identified was the prioritization of patients for discharge interventions. Pharmacists expressed that, ideally, they would like to be involved in all or most patient discharges. However, across all interviews, there was a consensus that a consequence of high workloads and limited staffing is that pharmacists are forced to constantly prioritize patients for discharge interventions and prioritize among potential interventions (e.g., medication education). Pharmacists stated that patient prioritization is based on various factors including: the type of medications (i.e., high vs low risk), number of medication changes or additions on discharge, and adverse drug event related admissions.

“…we can’t see everyone so usually we prioritize patients that are on… high alert medications, anti-coagulants, insulin and patients that have had a lot of medication changes or are just on a lot of medications in general.”-Participant

Most participants acknowledged that prioritization is done out of necessity, and more patients would benefit from pharmacist involvement in discharge interventions. Also, if time/resources permitted, these interventions would ideally be done for all patients.

Important roles of a pharmacist in discharges

The participants identified a number of key roles for pharmacists which can optimize the discharge process including active involvement in formulating and communicating the discharge medication plan. Further, most participants agreed that hospital pharmacists should ideally lead discharge medication reconciliation, review all discharge prescriptions and where scope permits, take the lead on writing them. Participants agreed that hospital pharmacists are the optimal healthcare team member to communicate patient medication care plans with community care providers, especially for more complex cases.

“I think it depends on the patient…. there’s the complex discharges…where medications have been changed significantly throughout the admission, I personally like to be involved in those and I think… in terms of…the right people to communicate with the community pharmacy, what’s been stopped what’s been changed and communicating with the patient, I think the pharmacist is probably the more appropriate person to be involved in the complex discharges.”-Participant

Participants also felt that hospital pharmacists are uniquely skilled at customizing care for individual patients through addressing barriers to patients accessing and receiving medications, and implementing medication special arrangements (e.g., daily dispense) with community pharmacists.

Patient Education

Patient education, including medication counselling, was agreed to be an important component of optimal discharges. Most participants indicated that current resources do not allow for optimal pharmacist involvement because of the time intensive nature of patient education, particularly if it is done effectively. Participants described the optimal approach to education as starting early, repeating instructions often and supplementing verbal information with customized written materials.

“I would say on top of…counselling is having something written for the patients to follow. Especially in regards to medications when they go home because a lot of it, I think they either forget or it’s not clear enough the first time around. So, having something that they can refer to when they leave would be important... “-Participant

Further, the current discharge education process, particularly generic, duplicate verbal information was noted as being ineffective.

“[General patient drug information handouts] that have 5 different indications need to be removed out of hospitals because we are luxuriant enough to know the actual indication for the drug, where the retail pharmacy, unfortunately often doesn’t. So, it just blows my mind that we would have… apixaban for VTE, SVT, Afib, all on the same form….”-Participant

Barriers to optimal discharges

The next theme is closely related to prioritization. Hospital pharmacists discussed many barriers they face when it comes to optimally discharging patients. When asked if they felt like they had enough time to optimally discharge their patients, most pharmacists stated that they do not.

“I think probably the biggest issue is … just a lack of time…. we have a certain amount of time each day and we have a full ward of patients we have to look after and I think as pharmacists are being more and more recognized as valuable members of the team, we are starting to get pulled into all directions to do different things…”-Participant

The most frequently mentioned barriers that contribute to the occurrence of suboptimal patient discharges were staffing, overall daily workload (i.e., competing responsibilities) and high patient to pharmacist ratios.

“I think another barrier is staffing…I feel like sometimes we need more than one pharmacist …to 40 patients…on a general medicine ward.”-Participant

Other important barriers identified include system factors, such as last minute or unplanned discharges and lack of formalization for the discharge process; and patient specific factors, such as language barriers and inability to obtain edications post discharge. It was also noted that constant fforts to support optimal discharge can contribute to feelings of burnout.

Solutions to current barriers

Throughout all interviews, participants identified several solutions to the barriers impacting optimal patient discharges. A frequently cited solution was increased pharmacy staffing. Participants indicated that improved staffing ratios would allow pharmacists to be actively involved in a greater proportion of patient discharges. Additionally, support from pharmacy technicians and assistants was proposed.

“…. I have found useful is that our site has admission med-recs techs who take the [Best Possible Medication History] BPMH and one thing we’ve asked them to do is identify the patient’s community pharmacy early on.”-Participant

Next, having a more standardized approach to discharge intervention by defining the pharmacists and other team members’ roles, may improve communication and allow for more optimal discharge interventions.

“Although I do think that it should be give and take, I do think that it’s helpful to have well defined roles…But I think where gaps happen is when each of us thinks that another person is doing the thing, like okay I thought you were going to get the special authority or I thought you had it… I don’t think it should always be the same for every team and every situation but, clearly knowing what everyone’s responsible for and then of course if you’re not there or if you can’t make it or if you’re too busy then passing it over to someone else.”-Participant

Another solution proposed was to increase the pharmacist scope of practice, which would allow pharmacists to take the lead on writing discharge prescriptions. Participants also discussed how pharmacists are trained to clearly reconcile medications on prescriptions and understand the fragmentation that occurs from the community pharmacy and patient perspective. Because of this, there was general agreement that pharmacists taking the lead on writing prescriptions allows for a more streamlined process. Lastly, implementation of post-discharge phones calls, especially for higher risk patients, was noted as being potentially beneficial in reducing negative patient outcomes. However, time and resources may limit pharmacists from carrying out this intervention.

Member Checking Survey

A member checking survey was distributed to the study participants in order to provide feedback regarding the identified themes. In total 13 of 21 participants responded to the survey. All participants expressed agreement with the themes shared by the study team.

DISCUSSION

Optimal patient discharge is a multifaceted, team-based process. The pharmacist participants of this study felt strongly that pharmacists should play a central role in the patient discharge process and described how their unique expertise contributes to its success. However, the current consensus amongst those we interviewed was that they cannot participate optimally due to excessive workload and competing demands.

The pharmacist participants endorsed the value of interventions that have been shown in the literature to be impactful (e.g., pharmacist-led patient counselling, post-discharge phone calls, and communication with other team members) 1-3,10-12, 15-17. For instance, the implementation of pharmacist-led patient education can result in improved medication knowledge, improved adherence, reduction in morbidity and possibly a reduction in mortality as well. 10,12, 15-17 However, to mitigate the time and resource constraints faced, pharmacists consistently described a constant pressure to prioritize patients and choosing which interventions to implement. The process of prioritizing patients for discharge interventions can be a difficult task, as it may not always be clear which patients are at a higher risk of medication related errors compared to others. Further, there may be variation in what different practitioners perceive to be high risk.

The studies discussed above all implemented a formalized process for the interventions studied; however, the participants in our study did not generally have defined or standardized roles in the discharge process (e.g., physician writes the prescription, pharmacist provides medication counselling etc.). The few pharmacists that did have defined roles, expressed more confidence in their ability to discharge patients optimally. For example, pharmacists working in renal transplant revealed that they have clearly defined roles in discharge intervention implementation and that these interventions are implemented in a standardized way. Interventions included providing patient education (starting early and repeating often) and communicating with community care providers. Having a standardized approach ensures that all patients receive the information they require to be well versed in the use of their medications to prevent post-discharge medication related errors or readmissions.

In addition to defined roles, the renal transplant model generally has slower patient turnover and patient to pharmacist ratios that are lower than in other areas. Unfortunately, optimal pharmacist to patient ratios are not always possible due to lack of funding and little consensus on what optimal pharmacist to patient ratios are for clinical practice. However, although funding is often cited as a reason for inadequate staffing, increased pharmacist involvement in discharge could reduce other costs such as delayed discharges (flow), readmissions and ADEs and therefore, would be worth exploring.

Another solution would be increased support from pharmacy technicians. Pharmacy technicians are vital to a pharmacy team and can take on tasks traditionally completed by pharmacists. For instance, the qualitative review by Irwin et al., (2017) found that pharmacy technicians can complete the BPMH with similar efficiency as other healthcare providers (pharmacists, physicians etc.). 18 Therefore, having pharmacy technicians assist with BPMH as well as discharge coordination tasks, such as faxing prescriptions to community providers and making arrangements for medication cost reimbursement, would help alleviate the pharmacist’s workload. Ultimately, this would allow pharmacists more time to optimally discharge patients.

This study is not without its limitations. First, the results of this study may be difficult to extrapolate to clinical settings outside of BC. However, it should be noted that the participants that did participate were from a variety of different backgrounds and worked in a variety of practice settings. The heterogeneity of our participants may be seen as a strength. Second, the use of focus group interviews can introduce bias, such as the group bias effect.19 Further, participants in a focus group setting may be less likely to reveal more personal thoughts or opinions compared to during one-on-one interview settings.19 Participants did have the opportunity to provide anonymous feedback during the member checking survey of the analysis. Third, we assumed that a theoretical data saturation was achieved; however, there may be thoughts and perceptions of hospital pharmacists that were not captured. Fourth, we did not consider the perception of other clinical team members or patients regarding the role of pharmacists in the patient discharge process. The pharmacists’ self-perceived role and value may differ from other team members or patient perspectives.

CONCLUSION

Overall, we found that because of their skill set and expertise, pharmacists feel that they should play a central role in the discharge process. However, time and resource constraints prevent pharmacists from being optimally involved in all patient discharges. Solutions to this include increased pharmacy support staff, expanding the pharmacist’s scope of practice and standardization of healthcare team member roles. Future research into the development of standardized approaches and/or clinical tools, and the thoughts and perceptions of other healthcare team members and patients on the role of pharmacists in patient discharges, may help assist pharmacists in optimally discharging their patients.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interests: All authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Financial acknowledgments: Honorarium for participants was funded from the Principal Investigator’s (KD) unrestricted start-up research funds. No other funding was provided for this study.

Presentations: This research was presented as a poster at the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists Together: Canada’s Hospital Pharmacy Conference 2022.

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors.

References

- 1.Rodrigues C, Harrington A, Murdock Net al. Effect of Pharmacy-Supported Transition-of-Care Interventions on 30-Day Readmissions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51(10):866-889. doi: 10.1177/1060028017712725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mekonnen A, McLachlan A, Brien J.. Effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on clinical outcomes at hospital transitions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010003. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mekonnen A, McLachlan A, Brien J.. Pharmacy-led medication reconciliation programmes at hospital transitions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(2):128-144. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herledan C, Baudouin A, Larbre Vet al. Clinical and economic impact of medication reconciliation in cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(8):3557-3569. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05400-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke R, Guo R, Prochazka A, Misky G.. Identifying keys to success in reducing readmissions using the ideal transitions in care framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1). doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyler N, Wright N, Waring J.. Interventions to improve discharge from acute adult mental health inpatient care to the community: systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:883-907. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4658-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Hajj MS, Jaam MJ, Awaisu A.. Effect of pharmacist care on medication adherence and cardiovascular outcomes among patients post-acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2018;14:507-520. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNab D, Bowie P, Ross A, MacWalter G, Ryan M, Morrison J.. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27:308-320. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomlinson J, Cheong VL, Fylan Bet al. Successful care transitions for older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of interventions that support medication continuity. Age Aging. 2020;49:558-569. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okumura LM, Rotta I, Correr CJ.. Assessment of pharmacist-led patient counseling in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36:882-891. doi: 10.1007/s11096-014-9982-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Oliveira GS, Castro-Alves LJ, Kendall MC, McCarhy R.. Effectiveness of pharmacist intervention to reduce medication errors and health-care resources utilization after transitions of care: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Patient Saf. 2017;0:1-6. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makari J, Dagenais J, Tadrous M, Jennings S, Rahmaan I, Hayes K.. Hospital pharmacist discharge care is independently associated with reduced risk of readmissions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A propensity-matched cohort study. Can Pharm J. 2022;155(2):101-6. doi: 10.1177/17151635211061141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregory P, Zubin Austin. Pharmacists’ lack of profession-hood: Professional identity formation and its implications for practice. Can Pharm J. 2019:152(4);251-256. doi: 10.1177/1715163519846534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun V, Clarke V.. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark PM, Karagoz, T, Apikoglu-Rabus S, Izzettin FV.. Effect of pharmacist-led patient education on adherence to tuberculosis treatment. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(5):497-505. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroud A, Adunlin G, Skelley JW.. Impact of a pharmacy-led transition of care service on post-discharge medication adherence. Pharmacy. 2019;7(3):128. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy7030128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saini B, LeMay K, Emmerton Let al. Asthma disease management—Australian pharmacists’ interventions improve patients’ asthma knowledge and this is sustained. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(3):295-302. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irwin AN, Ham Y, Gerrity TM.. Expanded roles for pharmacy technicians in the medication reconciliation process: a qualitative review. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(1):44-53. doi: 10.1310/hpj5201-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyumba TO, Wilson K, Derrick CJ, Mukherjee N.. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol Evol. 2018;9(1):20-32. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12860 [Google Scholar]