Abstract

Background:

Germline BRCA1/2 testing (GT) is instrumental in identifying patients with breast (BC) and ovarian cancer (OC) who are eligible for PARP inhibitors (PARPi). Little is known about recent trends and determinants of GT since PARPi were approved for these patients.

Patients and Methods:

We performed a retrospective cohort study of patients in a nationwide EHR-derived oncology-specific database with the following GT eligibility criteria: BC diagnosed ≤45 years, triple negative BC diagnosed ≤60 years, male BC, or OC. GT within one year of diagnosis was assessed and stratified by tumor type. Multivariable log-binomial regressions estimated adjusted relative risks (RR) of GT by patient and tumor characteristics.

Results:

Among 2,982 eligible patients with BC, 56.4% of patients underwent GT between 1/2011-3/2020, with a significant increase in GT over time (RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.05-1.11 for each year), independent of when PARPi were approved for BRCA1/2-mutated metastatic BC in 1/2018. In multivariable analyses, older age (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.90-0.96 for every 5 years) and Medicare coverage (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49-0.96 versus commercial insurance) were associated with less GT. Among 5,563 eligible patients with OC, 35.4% of patients underwent GT between 1/2011-3/2020, with a significant increase in GT over time (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.07-1.14 for each year) which accelerated after PARPi were approved for BRCA1/2-mutated chemotherapy-refractory OC in 12/2014 (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.19-1.70). Older age (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.93-0.97 for every 5 years) and Black race (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.65-0.98 versus white race) were associated with less GT.

Discussion:

GT remains underutilized nationwide among patients with breast and ovarian cancer. Although GT has increased over time, significant disparities by age, race and insurance status persist.

Conclusion:

Additional work is needed to design, implement, and evaluate strategies to ensure that all eligible patients receive GT.

INTRODUCTION

Germline genetic testing (GT) is instrumental in identifying patients with cancer predisposition syndromes who may benefit from additional screenings, risk-reducing and therapeutic interventions, and cascade testing of family members. BRCA1 and BRCA2 are cancer susceptibility genes that when mutated, confer an increased risk for breast (BRCA1: 65-79%; BRCA2: 61-77%) and ovarian (BRCA1: 36-53%; BRCA2: 11-25%) cancers1. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends GT for BRCA1/2 and other high-penetrance cancer susceptibility genes for a subset of patients with breast cancer (e.g.; based on tumor characteristics, age at diagnosis, ancestry, and family history) and all patients diagnosed with ovarian cancer2. Despite these recommendations, prior studies have shown suboptimal rates of GT and disparities by age, race, and insurance status3-10.

Since 2014, GT has taken on added significance as poly ADP ribose polymerase inhibitors (PARPi) have introduced biomarker-driven interventions for breast and ovarian cancer patients with germline alterations in BRCA1/2 7,8,11,12. As the role for GT expands in clinical practice, there is a critical need to understand more recent trends and determinants of its uptake. We performed a retrospective cohort study to characterize nationwide trends and determinants of germline BRCA1/2 testing in patients diagnosed with breast and ovarian cancer between 2011 and 2020. We hypothesized that GT has increased but that sociodemographic disparities have persisted since PARPi were approved.

METHODS

Data source

This study used the Flatiron Health database, a nationwide, longitudinal, electronic health record (EHR)-derived database comprised of de-identified patient-level structured and unstructured data, curated via technology-enabled abstraction13. The database included data from approximately 280 community and academic cancer clinics (~800 sites of care) during the study period. Demographic variables for patients in the Flatiron Health database are similar with respect to age, sex, and geographic distribution to the 18-registry grouping from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program and data from the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR)14. Centralized abstraction protocols, duplicate chart abstraction, logic checks, and formal adjudication are used to ensure quality control15.

Patient population

The study included adult patients who met one of the following GT eligibility criteria between January 1, 2011 and March 31, 2020: 1) breast cancer diagnosed ≤45 years; 2) triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) diagnosed ≤60 years; 3) male breast cancer; or 4) ovarian cancer. The TNBC criterion was applied after April 7, 2011 to reflect the date when NCCN guidelines were updated to include this additional patient population. Patients were required to have both an ICD-9/10 code and pathology consistent with breast or ovarian cancer, as well as at least two encounters on different days and structured EHR activity within 90 days of diagnosis. Follow-up data were included until March 31, 2021.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was GT within one year of diagnosis, defined as BRCA1/2 testing performed on a blood or saliva specimen to distinguish it from somatic tumor testing. Patients with evidence of GT prior to diagnosis were excluded from the analysis. To explore potential misclassification of this outcome, we reviewed the medical records of a subset of patients with early-stage breast cancer at the University of Pennsylvania to determine the positive (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of Flatiron Health’s ascertainment of GT.

A secondary outcome of somatic next-generation sequencing (NGS) within one year of diagnosis was evaluated in an exploratory analysis evaluating the agreement between GT and NGS testing. Patients with evidence of somatic NGS testing prior to diagnosis were excluded from this analysis.

Determinants

Demographic, clinical, and tumor characteristics measured closest to and within 90 days of each patient’s diagnosis were evaluated as potential determinants of GT. These variables included age, race, ethnicity, insurance status, Charlson comorbidity index (calculated using ICD-9/10 codes, excluding any cancer), stage at diagnosis, and diagnosis date. Patient sex and TNBC status were also evaluated as potential determinants in the analysis of patients with breast cancer. To evaluate the potential association between PARPi approvals and GT, we defined diagnosis date epochs using the PARPi approval dates of January 12, 2018 for breast cancer (olaparib approval date for BRCA1/2-mutated metastatic breast cancer7) and December 19, 2014 for ovarian cancer (olaparib approval date for BRCA1/2-mutated chemotherapy-refractory ovarian cancer11).

Statistical analysis

Time from diagnosis to GT was evaluated using kernel density plots for both the breast and ovarian cancer cohorts. Baseline characteristics were evaluated using standard descriptive statistics. We evaluated the nature and degree of missingness for variables with missing data and found that they were not missing completely at random. As such, we conducted multiple imputation by chained equations to impute the missing values16,17. We generated 25 imputed datasets, performed our analyses using these datasets, and used Rubin’s rules to generate combined effect estimates and variances18. All analyses utilized the multiply imputed datasets except where noted.

Spline regression was used to estimate the annual prevalence of GT over time and to assess for nonlinearity in the association between GT and patient age for both the breast and ovarian cancer cohorts. We found that the relationship between GT and diagnosis date generally followed a linear pattern and as such, included diagnosis year as a continuous variable in subsequent regression analyses. Univariable log-binomial regressions were used to estimate the relative risk (RR) of GT for the determinants described above. Variables with p <0.1 on univariable models were retained in final multivariable models to estimate the adjusted RR of GT by patient and tumor characteristics. Generalized estimating equations were used to account for clustering by practice site. All analyses were stratified by tumor type. Tests of statistical significance were two-sided, and significance was defined as p <0.05. All analyses were performed using STATA version 17.

Sensitivity analyses

Multiple sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the robustness of our results. First, we limited our analyses to the post-PARPi approval period to evaluate more recent determinants of GT. Second, we restricted our analyses to community oncology practices on Flatiron Health’s OncoEMR platform to assess the impact of potential misclassification due to chart abstraction from the more heterogeneous set of EHRs used in academic oncology practices. Third, we limited our analyses to patients who remained alive one year after diagnosis to evaluate the impact of potential survival bias. Finally, we used the non-imputed data set to assess the impact of potential bias introduced during the multiple imputation procedure.

Exploratory analysis

We calculated kappa statistics to evaluate the agreement between GT and somatic NGS testing within one year of diagnosis for patients with metastatic breast and any-stage ovarian cancer.

Approval was obtained from the University of Pennsylvania and the Copernicus Group Institutional Review Boards and included waiver of informed consent.

RESULTS

Patient population

We reviewed 12,074 records in the Flatiron Health database that met eligibility criteria, of which 3,529 (29.2%) were excluded due to duplicate records, lack of structured EHR activity, or evidence of GT prior to diagnosis (Supplemental Figure 1). Among 2,982 patients with breast cancer, most patients (64.3%) were eligible for GT due to a diagnosis under age 45 (Table 1). The median age in the breast cancer cohort was 43.0 years; most patients were white (60.1%), not Hispanic or Latino (89.4%), and commercially insured (63.9%). Among 5,563 eligible patients with ovarian cancer, the median age was 65.9 years, 78.0% of patients were white, 92.8% of patients were not Hispanic or Latino, and 59.0% were commercially insured. These baseline characteristics followed a comparable distribution in the multiply imputed datasets (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Breast cancer (n = 2,982) | Ovarian cancer (n = 5,563) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germline BRCA1/2 testing1 (n = 1,682) |

No germline BRCA1/2 testing1 (n = 1,300) |

Germline BRCA1/2 testing1 (n = 1,968) |

No germline BRCA1/2 testing1 (n = 3,595) |

|

| Diagnosis year | ||||

| 2011 | 105 (6.2%) | 153 (11.8%) | 72 (3.7%) | 335 (9.3%) |

| 2012 | 135 (8.0%) | 175 (13.5%) | 86 (4.4%) | 459 (12.8%) |

| 2013 | 159 (9.5%) | 180 (13.8%) | 107 (5.4%) | 459 (12.8%) |

| 2014 | 200 (11.9%) | 174 (13.4%) | 184 (9.3%) | 452 (12.6%) |

| 2015 | 215 (12.8%) | 173 (13.3%) | 211 (10.7%) | 375 (10.4%) |

| 2016 | 236 (14.0%) | 131 (10.1%) | 300 (15.2%) | 408 (11.3%) |

| 2017 | 211 (12.5%) | 131 (10.1%) | 265 (13.5%) | 395 (11.0%) |

| 2018 | 182 (10.8%) | 86 (6.6%) | 309 (15.7%) | 362 (10.1%) |

| 2019 | 204 (12.1%) | 80 (6.2%) | 348 (17.7%) | 261 (7.3%) |

| 2020 | 35 (2.1%) | 17 (1.3%) | 86 (4.4%) | 89 (2.5%) |

| Diagnosed post-PARPi approval | ||||

| No | 1265 (75.2%) | 1125 (86.5%) | 443 (22.5%) | 1697 (47.2%) |

| Yes | 417 (24.8%) | 175 (13.5%) | 1525 (77.5%) | 1898 (52.8%) |

| Eligibility criterion | ||||

| Breast cancer <=45 | 1165 (69.3%) | 741 (57.0%) | --2 | -- |

| TNBC <=60 | 425 (25.3%) | 447 (34.4%) | -- | -- |

| Male breast cancer | 92 (5.5%) | 112 (8.6%) | -- | -- |

| Stage | ||||

| Stage I | 185 (11.0%) | 103 (7.9%) | 294 (14.9%) | 738 (20.5%) |

| Stage II | 460 (27.3%) | 282 (21.7%) | 180 (9.1%) | 283 (7.9%) |

| Stage III | 379 (22.5%) | 267 (20.5%) | 912 (46.3%) | 1337 (37.2%) |

| Stage IV | 418 (24.9%) | 390 (30.0%) | 430 (21.8%) | 787 (21.9%) |

| Unknown | 240 (14.3%) | 258 (19.8%) | 152 (7.7%) | 450 (12.5%) |

| Age, median (IQR3) | 42.3 (37.6, 48.4) | 44.0 (39.8, 53.4) | 64.9 (55.7, 72.8) | 66.5 (56.9, 75.2) |

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 48 (2.9%) | 47 (3.6%) | 48 (2.4%) | 84 (2.3%) |

| Black or African American | 295 (17.5%) | 255 (19.6%) | 108 (5.5%) | 221 (6.1%) |

| White | 957 (56.9%) | 668 (51.4%) | 1412 (71.7%) | 2580 (71.8%) |

| Other race4 | 230 (13.7%) | 202 (15.5%) | 244 (12.4%) | 418 (11.6%) |

| Unknown | 152 (9.0%) | 128 (9.8%) | 156 (7.9%) | 292 (8.1%) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 1511 (89.8%) | 1156 (88.9%) | 1828 (92.9%) | 3334 (92.7%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 171 (10.2%) | 144 (11.1%) | 140 (7.1%) | 261 (7.3%) |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Commercial health plan | 687 (40.8%) | 430 (33.1%) | 880 (44.7%) | 1338 (37.2%) |

| Medicare | 33 (2.0%) | 54 (4.2%) | 291 (14.8%) | 594 (16.5%) |

| Medicaid, other govt program, or pt assistance program | 82 (4.9%) | 75 (5.8%) | 54 (2.7%) | 106 (2.9%) |

| Other | 228 (13.6%) | 159 (12.2%) | 143 (7.3%) | 354 (9.8%) |

| Unknown | 652 (38.8%) | 582 (44.8%) | 600 (30.5%) | 1203 (33.5%) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||

| 0 | 711 (42.3%) | 586 (45.1%) | 939 (47.7%) | 1573 (43.8%) |

| 1+ | 20 (1.2%) | 19 (1.5%) | 68 (3.5%) | 135 (3.8%) |

| Unknown | 951 (56.5%) | 695 (53.5%) | 961 (48.8%) | 1887 (52.5%) |

Germline BRCA1/2 testing was ascertained within one year of diagnosis

Listed eligibility criteria do not apply to patients with ovarian cancer

IQR = interquartile range

Includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and race descriptions that fall in multiple race categories

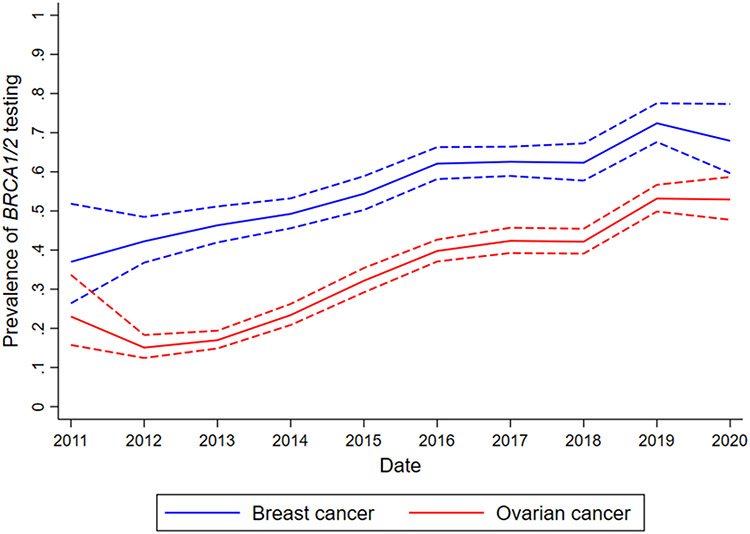

Prevalence of germline BRCA1/2 testing over time

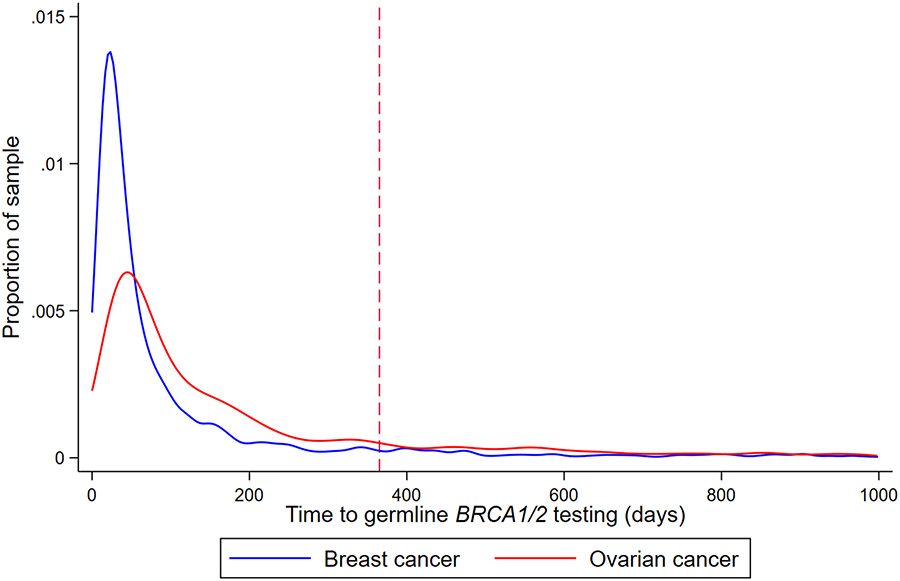

Among patients with breast cancer, the prevalence of GT within one year of diagnosis increased from 37.0% in 2011 to 67.9% in 2020 (Figure 1). Over the entire study period, 56.4% of patients were tested within one year of diagnosis, 7.1% were tested after one year, and 36.5% had no documentation of testing. Median time to GT was 42 days (Figure 2). In the ovarian cancer cohort, GT within one year of diagnosis increased from 23.0% in 2011 to 52.9% in 2020 (Figure 1), with 35.4% of patients tested within one year of diagnosis, 8.8% tested after one year, and 55.8% with no documentation of testing over the entire study period. Median time to GT was 101 days (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of germline BRCA1/2 testing over time, estimated using spline regressions among patients with breast cancer (blue) and ovarian cancer (red). Germline BRCA1/2 testing was defined as occurring within one year of diagnosis. Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Kernel density plot of time from diagnosis to BRCA1/2 test result among patients with breast cancer (blue) and ovarian cancer (red). The dashed red line indicates a threshold of 365 days that was used in subsequent analyses.

We evaluated for potential misclassification of GT by reviewing the medical records of 48 patients with early-stage breast cancer at the University of Pennsylvania and calculated a PPV of 96% and NPV of 61% in Flatiron Health’s ascertainment of GT. These discrepancies were due to GT results that had been scanned into the EHR but not available to Flatiron Health for abstraction.

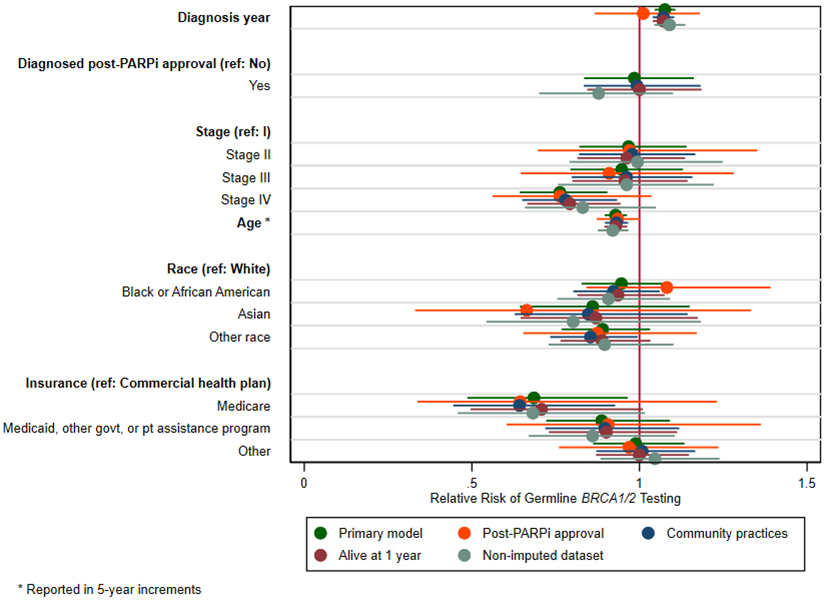

Determinants of germline BRCA1/2 testing

Among patients with breast cancer, there were no appreciable differences in GT within one year of diagnosis by sex, race, ethnicity. There was a significant increase in GT over time (RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.05-1.11 for each year after 2011), independent of when PARPi were approved for BRCA1/2-mutated metastatic breast cancer in January 2018 (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.83-1.16 for the post- versus pre-PARPi approval period, p-value for interaction term = 0.465) (Figure 3A, Supplemental Table 2). Compared to patients diagnosed with early-stage disease, patients diagnosed with metastatic disease were less likely to undergo GT (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.64-0.90 versus stage I disease). There was a negative linear relationship between GT and age (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.90-0.96 for every 5 years) (Supplemental Figure 2A). After adjusting for age, patients with Medicare were less likely to undergo GT (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49-0.96 versus commercial insurance), though the number of patients with Medicare was small (n = 87, 2.9%). Results remained similar in all pre-planned sensitivity analyses except in the analysis limiting to the post-PARPi approval period, where the effect estimates for disease stage, age, and insurance status remained similar in direction and magnitude but were no longer statistically significant (Supplemental Table 2).

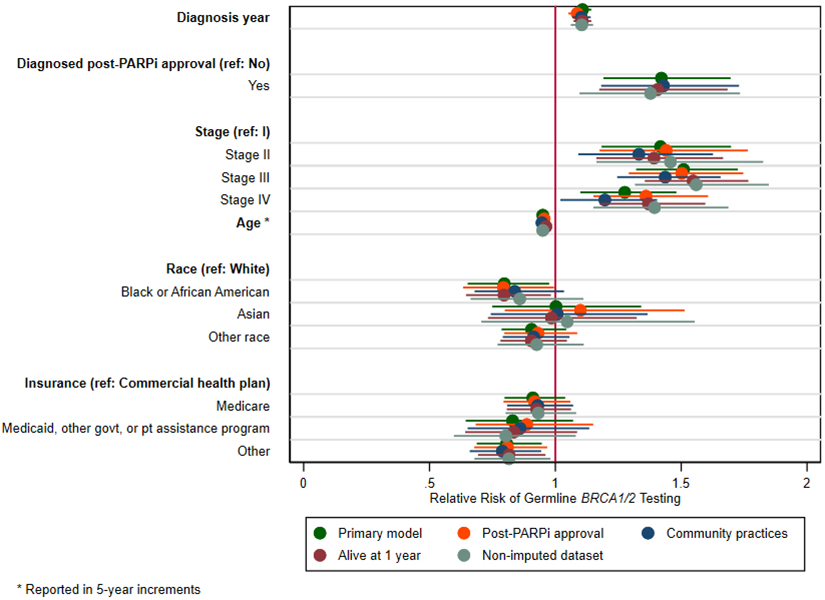

Figure 3.

Determinants of germline BRCA1/2 testing within one year of diagnosis among patients with A) breast cancer and B) ovarian cancer. Adjusted relative risks were estimated using log-binomial regressions using the multiply imputed datasets (primary analysis) and in sensitivity analyses limiting to the post-PARP inhibitor approval period, restricting to community oncology practices, limiting to patients who remained alive one year after diagnosis, and using the non-imputed dataset. Generalized estimating equations were used to account for clustering by practice site.

In the ovarian cancer cohort, there was a significant increase in GT over time (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.07-1.14 for each year after 2011) which accelerated after PARPi were approved in December 2014 for BRCA1/2-mutated chemotherapy-refractory ovarian cancer (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.19-1.70 versus the pre-PARPi approval period, p-value for interaction term = 0.003) (Figure 3B, Supplemental Table 3). Patients diagnosed with more advanced disease were more likely to undergo GT compared to those with stage I disease (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.18-1.70; RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.32-1.73; and RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.10-1.48 for stages II, III, and IV, respectively). Older age (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.93-0.97 for every 5 years) (Supplemental Figure 2B) and Black race (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.65-0.98 versus white race) were associated with a lower likelihood of GT, as was healthcare coverage other than a commercial health plan, Medicare, or Medicaid (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.69-0.95 versus commercial health insurance). Results remained similar in all pre-planned sensitivity analyses.

Exploratory analysis of somatic NGS testing

In an exploratory analysis of 2,005 patients with metastatic breast cancer, 125 (6.2%) completed both GT and somatic NGS testing within one year of diagnosis, 948 (47.3%) completed GT alone, 41 (2.0%) completed somatic NGS testing alone, and 891 (44.4%) had no documentation of either GT or somatic NGS testing. After accounting for the expected cooccurrence of GT and somatic NGS testing due to chance alone, we observed poor agreement in the completion of both tests in any given individual (kappa = 0.068, p <0.001).

Among 5,557 patients with ovarian cancer of any stage, 394 (7.1%) completed both GT and somatic NGS testing, 1,573 (28.3%) completed GT alone, 281 (5.1%) completed somatic NGS testing alone, and 3,309 (59.5%) completed neither. Agreement between somatic NGS testing and GT in this population was also poor (kappa = 0.143, p <0.001).

DISCUSSION

In this nationwide study of patients with breast and ovarian cancer, we demonstrated ongoing underutilization of GT through 2020, with over 40% of patients with breast cancer and 60% of patients with ovarian cancer with no documentation of GT within one year of diagnosis. Although GT has increased over time, significant disparities by age, race, and insurance status persist.

Multiple studies have demonstrated underutilization and sociodemographic disparities in GT, with rates ranging between 52-56% among eligible patients with breast cancer3-5 and 30-40% among patients with ovarian cancer9,19-21. Increasing age3,4,19, Black race5,9,10,19,21,22, and lack of commercial insurance coverage9,10 also have been identified as negative determinants of GT for both tumor types. However, these studies have been limited to single-institution investigations, claims-based analyses among commercially insured individuals, and registry-based studies in select states. In this study, we used a nationwide database comprised predominantly of community oncology practices to corroborate these previous findings while concurrently shedding light on other determinants of GT. Specifically, we observed a negative association between advanced tumor stage and GT for patients with breast cancer but a positive association for patients with ovarian cancer. We hypothesize that the higher prevalence of GT in patients with early-stage breast cancer may have been driven by decisions around risk-reducing surgery rather than PARPi candidacy, as this relationship persisted in our sensitivity analysis of the post-PARPi approval period. In contrast, patients with stage I ovarian cancer may have been less likely to undergo GT due to a perceived lack of therapeutic actionability, as PARPi have only been approved for more advanced disease. This contrasting relationship warrants further study, as it may inform a more tailored approach to improving the uptake of GT in these populations.

An additional strength of our study was the recency of the Flatiron Health database, which enabled us to evaluate recent trends in GT. A prior analysis of the Kaiser Permanente Washington integrated health system between 2005 and 2015 did not identify secular trends in GT among women with breast and ovarian cancer despite universal insurance coverage and access to specialized genetic services23. A subsequent study using the Georgia and California SEER registries demonstrated an annual 2% increase in GT between 2013 and 2017 among women with breast and ovarian cancer20. Our study spanning up to 2020 suggests that the prevalence of GT may be increasing further, likely due to a combination of PARPi approvals as well as rapidly advancing sequencing technologies24, novel “point-of-care” genetic testing models25-28, and the 2013 Supreme Court decision challenging the patentability of the BRCA1/2 genes29 which have collectively expanded access to and lowered costs for GT. Going forward, additional work is needed to ensure that all eligible patients receive GT, for instance by addressing patient-level barriers to GT; implementing default GT mechanisms into clinician workflows; raising awareness about existing insurance coverage and financial assistance programs for guideline-recommended GT; and simplifying GT guidelines (as was done with the NCCN’s 2022 update recommending GT for all patients with TNBC, regardless of age30).

The role of GT in therapeutic decision-making raises questions about when it should be offered in relation to a patient’s diagnosis and treatment. We demonstrated that time to GT followed a skewed distribution such that fewer than 15% of patients who had not undergone GT within one year of diagnosis received it later in their disease course. These patterns reinforce the importance of obtaining GT results early so that they can be used to determine candidacy not only for PARPi therapy but also for surgical interventions such as risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy and oophorectomy31-33. However, offering GT at the time of diagnosis may conflict with the provision of patient-centered care. In a qualitative study of patients with gynecologic malignancies who were eligible for GT, participants requested that GT follow active treatment so as not to overwhelm them at the time of initial diagnosis34. This preference for later GT may be due to difficulty discerning between the preventive versus therapeutic roles of GT, an observation that has been made among both breast and ovarian cancer patients35. Additional research is needed to identify more patient-centered approaches to offering GT while still ensuring that its timing facilitates its use in the delivery of personalized cancer care.

In addition to demonstrating underutilization of GT, this study highlighted a low prevalence of somatic NGS testing among patients with no documented GT, as well as poor agreement between somatic NGS testing and GT among patients with metastatic breast and any-stage ovarian cancer. These real-world practice patterns suggest that somatic NGS testing is not being used as a replacement for germline genetic risk assessment, although we recognize that this study was conducted prior to widespread incorporation of somatic NGS testing into NCCN guidelines. Given that somatic NGS testing is not perfectly substitutive for GT36-38, efforts should be made to ensure that all eligible patients are concomitantly evaluated for both germline and somatic genetic variation.

This study has several limitations. First, there are missing data for some of our study variables. We conducted multiple imputations on the missing variables and demonstrated comparable distributions between the non-imputed and multiply imputed data sets. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis using the non-imputed data set and observed findings that were similar to those of our primary analysis. Second, missing documentation of GT performed outside the Flatiron Health network may have led to misclassification of our primary outcome of interest. Indeed, our review of 48 patients with early-stage breast cancer at the University of Pennsylvania revealed a NPV of 61% due to Flatiron Health’s limited access to scanned records in Penn’s EHR. This limitation does not apply to the community oncology practices on Flatiron Health’s OncoEMR platform; as such, we conducted a sensitivity analysis restricting to community oncology practices and observed minimal variation in our study results. Finally, we were not able to ascertain specific reasons for why GT was not documented for some patients. Additional research is needed to identify other patient-, clinician-, and system-level determinants of GT.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates ongoing underutilization and sociodemographic disparities in GT among a nationwide cohort of patients with breast and ovarian cancer. Although GT has increased over time, additional work is needed to design, implement, and evaluate strategies to ensure that all eligible patients receive GT.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. Jama. 2017;317(23):2402–2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines); 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz SJ, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, et al. Gaps in Receipt of Clinically Indicated Genetic Counseling After Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(12):1218–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurian AW, Griffith KA, Hamilton AS, et al. Genetic Testing and Counseling Among Patients With Newly Diagnosed Breast Cancer. JAMA. 2017;317(5):531–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cragun D, Weidner A, Lewis C, et al. Racial disparities in BRCA testing and cancer risk management across a population-based sample of young breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2017;123(13):2497–2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy AM, Bristol M, Domchek SM, et al. Health Care Segregation, Physician Recommendation, and Racial Disparities in BRCA1/2 Testing Among Women With Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(22):2610–2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robson M, Im S-A, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(6):523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, et al. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(8):753–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurian AW, Ward KC, Howlader N, et al. Genetic Testing and Results in a Population-Based Cohort of Breast Cancer Patients and Ovarian Cancer Patients. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15):1305–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang M, Kamath P, Schlumbrecht M, et al. Identifying disparities in germline and somatic testing for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153(2):297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK, et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(3):244–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance Olaparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(26):2495–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birnbaum B NN, Seidl-Rathkopf K, et al. Model-assisted cohort selection with bias analysis for generating large-scale cohorts from the EHR for oncology research; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma X, Long L, Moon S, Adamson BJS, Baxi SS. Comparison of Population Characteristics in Real-World Clinical Oncology Databases in the US: Flatiron Health, SEER, and NPCR. medRxiv. 2020:2020.2003.2016.20037143. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miksad RA, Abernethy AP. Harnessing the Power of Real-World Evidence (RWE): A Checklist to Ensure Regulatory-Grade Data Quality. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(2):202–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes RA, Heron J, Sterne JAC, Tilling K. Accounting for missing data in statistical analyses: multiple imputation is not always the answer. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(4):1294–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoskins PJ, Gotlieb WH. Missed therapeutic and prevention opportunities in women with BRCA-mutated epithelial ovarian cancer and their families due to low referral rates for genetic counseling and BRCA testing: A review of the literature. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2017;67(6):493–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurian AW, Ward KC, Abrahamse P, et al. Time Trends in Receipt of Germline Genetic Testing and Results for Women Diagnosed With Breast Cancer or Ovarian Cancer, 2012-2019. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2021;39(15):1631–1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor C, Mooney R, Liu Y, et al. Testing for mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 among ovarian cancer patients at a diverse academic medical center. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2021;39(15_suppl):10588–10588. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy DE, Byfield SD, Comstock CB, et al. Underutilization of BRCA1/2 testing to guide breast cancer treatment: Black and Hispanic women particularly at risk. Genetics in Medicine. 2011;13(4):349–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knerr S, Bowles EJA, Leppig KA, Buist DSM, Gao H, Wernli KJ. Trends in BRCA Test Utilization in an Integrated Health System, 2005-2015. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(8):795–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pilarski R. How Have Multigene Panels Changed the Clinical Practice of Genetic Counseling and Testing. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2021;19(1):103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheinberg T, Young A, Woo H, Goodwin A, Mahon KL, Horvath LG. Mainstream consent programs for genetic counseling in cancer patients: A systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenfield Harold CS; Youngblom Janey; Tong Barry; Blanco Amie. Evaluation of the Genetic Testing Station, a Alternative Video-Based Model of Cancer Genetic Counseling and Testing. National Society of Genetic Counselors. Virtual; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton JG, Symecko H, Spielman K, et al. Uptake and acceptability of a mainstreaming model of hereditary cancer multigene panel testing among patients with ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancer. Genet Med. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colombo N, Huang G, Scambia G, et al. Evaluation of a Streamlined Oncologist-Led BRCA Mutation Testing and Counseling Model for Patients With Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(13):1300–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Supreme Court of the United States. Assoication for Molecular Pathology et al. v. Myraid Genetics, Inc., et al; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines); 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Singer CF, et al. Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. Jama. 2010;304(9):967–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Domchek SM. Risk-Reducing Mastectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: A Complex Discussion. Jama. 2019;321(1):27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armstrong J, Lynch K, Virgo KS, et al. Utilization, Timing, and Outcomes of BRCA Genetic Testing Among Women With Newly Diagnosed Breast Cancer From a National Commercially Insured Population: The ABOARD Study. JCO Oncology Practice. 2021;17(2):e226–e235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaw J, Bulsara C, Cohen PA, et al. Investigating barriers to genetic counseling and germline mutation testing in women with suspected hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome and Lynch syndrome. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(5):938–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright S, Porteous M, Stirling D, et al. Patients' Views of Treatment-Focused Genetic Testing (TFGT): Some Lessons for the Mainstreaming of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Testing. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(6):1459–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luthra R, Chen H, Roy-Chowdhuri S, Singh RR. Next-Generation Sequencing in Clinical Molecular Diagnostics of Cancer: Advantages and Challenges. Cancers (Basel). 2015;7(4):2023–2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellison G, Huang S, Carr H, et al. A reliable method for the detection of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in fixed tumour tissue utilising multiplex PCR-based targeted next generation sequencing. BMC Clin Pathol. 2015;15:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Casey G. The BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast cancer genes. Curr Opin Oncol. 1997;9(1):88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.