Abstract

Purpose of Review

The right ventricle (RV) has a complex geometry and physiology which is distinct from the left. RV dysfunction and failure can be the aftermath of volume- and/or pressure-loading conditions, as well as myocardial and pericardial diseases.

Recent Findings

Echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging and right heart catheterisation can assess RV function by using several qualitative and quantitative parameters. In pulmonary hypertension (PH) in particular, RV function can be impaired and is related to survival.

Summary

An accurate assessment of RV function is crucial for the early diagnosis and management of these patients. This review focuses on the different modalities and indices used for the evaluation of RV function with an emphasis on PH.

Keywords: Right ventricular function, Pulmonary hypertension, Right ventricular ejection fraction, Right ventricular-pulmonary arterial coupling, Right heart catheterisation

Introduction

Anatomy of the Right Ventricle

The right ventricle (RV) has a very distinct anatomy compared to the left (LV). It consists of 3 segments as follows: the inlet which includes the tricuspid valve (TV), the outlet or infundibulum with the pulmonary valve and a trabeculated apex [1]. The RV has at least 3 papillary muscles, a moderator band which incorporates the right bundle branch [2] and a myocardial fold called crista supraventricularis. RV myocardial fibres are arranged circumferentially in the superficial and longitudinally in the deep layers leading to a contraction from inlet to outlet and from the free wall to the septum. RV contraction relies more on longitudinal shortening than twisting and rotational movements as in the LV [3]. Normal coronary perfusion to the RV occurs during both systole and diastole in contrast with the LV which is perfused mainly in diastole. In utero RV and LV wall thickness are equal, however, once the umbilical cord is clamped at birth pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) reduces rapidly and RV wall thickness reverses [4, 5]. Hence, the RV is a thin-walled and crescent-shaped ventricle compared to a thick-walled and bullet-shaped LV [6]. This feature makes the RV respond better to volume overload but worse to pressure loading, unlike the LV. Both ventricles share the septum (IVS) and are contained within the same pericardium; these commonalities determine their interdependence [7].

Physiology

RV function should be examined along with pulmonary arterial (PA) function [8•]. RV and PA form a cardiopulmonary unit the function of which is characterised by two components: RV contractility and PA load, which is also known as RV afterload. In a normal-functioning RV, these two components are ‘coupled’. This ‘RV-PA coupling’ secures an efficient energy transfer of RV load to arterial load. The gold-standard metric to express RV contractility is end-systolic elastance (Ees). Elastance describes the change in pressure for a given change in volume and is a property of elastic chambers. Ees is load-independent and is determined by the contractile force of the myocyte and cardiac muscle hypertrophy [9].

PA load consists of two elements as follows: a steady and a pulsatile load. PVR is an expression of the steady load and pulmonary artery compliance (PAC) of the pulsatile load. PVR and PAC are inversely related [10]. PAC is a measure of PA distensibility and may be more sensitive to early disease [11, 12]. The calculation of a total PA load incorporating all components is challenging but is best represented by effective arterial elastance (Ea). There are different ways to calculate Ees, PVR, PAC, Ea and RV-PA coupling, which are described under ‘Invasive Haemodynamics’ in this review.

Pathophysiological Changes in a Pressure-Loaded RV

This review will focus on the assessment of RV function in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) which is the archetypical example of a pressure-loaded RV. In PAH, the proliferative changes in the small pulmonary arteries may lead to a decrease in PAC and a subsequent increase in PVR. The RV adapts to the increased afterload by concentric hypertrophy which can raise its contractility 4 to 5-fold, and thus ‘RV-PA coupling’ will be maintained [13]. However, as PAH advances and further RV hypertrophy is not feasible, the RV starts dilating as this is the only way to maintain stroke volume (SV) via the Frank-Starling mechanism [14•]. RV dilatation increases wall stress and oxygen consumption and triggers ischaemia via two mechanisms as follows: elevated oxygen demands and reduced perfusion in the context of increased intramural pressure [15, 16]. Another consequence of RV dilatation is the development of functional tricuspid regurgitation (TR) via TV annulus stretching, which causes RV volume loading and further dilatation. In addition, IVS shifts towards the LV in systole leading to interventricular dyssynchrony, LV underfilling and myocardial cell atrophy [17]. Thus, in PH it is more accurate to refer to biventricular rather than solely RV dysfunction and failure.

Aetiology of Right Heart Failure

Right heart failure (HF) is a syndrome characterised by alteration in structure and/or function of the RV-PA unit leading to suboptimal blood flow to the pulmonary circulation [18, 19]. Its causes are summarised in Table 1. It is not uncommon for more than one pathology or mechanisms to be present.

Table 1.

Causes of right heart failure

| Aetiology of right heart failure | |

| 1. Pressure overload | |

|

i) Acute: PE ii) Chronic: PH, PA or PV stenosis [20] | |

| 2. Volume overload | |

|

i) TR: structural (e.g. Ebstein’s anomaly [21], carcinoid, endocarditis, and flail valve) and functional (e.g. PH and chronic AF) ii) PR: structural (e.g. carcinoid and endocarditis) and functional (e.g. PA dilatation) iii) Left-right shunt (ASD and PAPVD) iv) High output status (e.g. anaemia, thyrotoxicosis, liver cirrhosis, and Paget’s) | |

| 3. Myocardial disease | |

|

i) RV myocardial infarction [22] ii) Arrhythmogenic RV cardiomyopathy [23] iii) Myocarditis [24] iv) Dilated cardiomyopathy v) Takotsubo cardiomyopathy vii) Uhl’s anomaly (aplasia or hypoplasia of RV myocardium) [27] viii) Endomyocardial fibrosis [28] ix) Amyloidosis [29] x) Chagas disease | |

| 4. Pericardial disease | |

|

i) Constriction ii) Tamponade | |

| 5. Iatrogenic (via volume or pressure overload) | |

| Excessive volume loading, mechanical ventilation | |

| 6. Mixed (e.g. pressure and volume overload) |

PE pulmonary embolism, PH pulmonary hypertension, PA pulmonary artery, PV pulmonary valve, TR tricuspid regurgitation, AF atrial fibrillation, PR pulmonary regurgitation, ASD atrial septal defect, PAPVD partial anomalous pulmonary vein drainage, RV right ventricular

Assessment of RV Function

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is an established tool for the evaluation of cardiac structure and function and can be used for diagnosis, monitoring and treatment guidance. Its widespread availability, versatility and relative ease of use makes it a fundamental investigation. Its limitations include incomplete visualisation of all aspects of the RV, poor echogenicity in some subjects and a lower repeatability than cardiac MRI. In addition, loading conditions (e.g. high cardiac output status and significant TR), ventilatory failure and the use of inotropes or invasive ventilation may influence RV function and should be considered during its evaluation. Echocardiography can provide qualitative and quantitative assessment of RV function. 2D imaging, M-mode, Doppler, Tissue Doppler Imaging (TDI) and colour flow mapping are standard approaches, whilst strain and 3D echocardiography have garnered a significant evidence base for diagnosis and prognostication. Often no single parameter is sufficient, and a holistic approach [20] is required, whilst protocols and datasets for RV assessment have been published [21–24].

The complex geometry of the RV and its retrosternal position make its imaging challenging. In standard 2D imaging, the RV focused apical 4-chamber view (RVf4C) rather than the conventional 4-chamber view should be used as the standard tomographic plane to measure linear metrics of RV size and function [21, 24–26]. In this view, RV size is systematically larger with lower variability, compared to the conventional view [26]. A basal RV diameter > 42 mm and/or RV:LV ratio > 1 indicate RV dilatation. More recent data support a normal basal RV size > 47 mm in males and 43 mm in females [21•]. Metrics of RV function are discussed below. Although not discussed in this review, continuous wave (CW) Doppler of tricuspid and pulmonary regurgitant velocities allow estimation of PA pressures and form an essential part of RV assessment. Furthermore, pulse wave (PW) Doppler of the RVOT can allow detection of a raised PVR; short PA acceleration time and mid-systolic notching are indicative of increased wave reflection [27,22•, ]. In a comprehensive RV assessment, it is also important for the compartments proximal (right atrium (RA)) and distal (PA) to the RV to be evaluated, as well as the left heart and pericardium.

Assessment of Regional RV Function

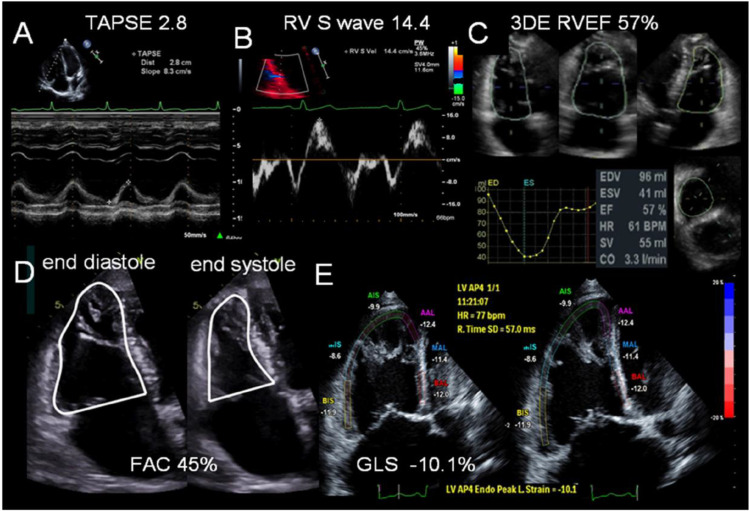

TAPSE

Tricuspid annular systolic plane excursion (TAPSE) is defined as the displacement (distance usually expressed in mm) of the lateral TV annulus during systole with M-mode echocardiography (Fig. 1). It is simple and reproducible but is load- and angle-dependent. It is measured from edge to edge with a high sweep speed (100 mm/s). In the setting of TR, it can become pseudo-normalised due to volume loading, and other indices such as strain [28, 29] or RV ejection fraction (RVEF) [30, 31] are recommended. An abnormal TAPSE is defined as < 17 mm. In our experience, TAPSE is often the last metric of RV function to worsen in PH, despite a severe reduction in radial function which usually precedes. TAPSE has been shown to correlate closely with RVEF determined by radionucleotide ventriculography [32] and MRI [33], and it is a strong prognostic marker in PH and other cardiovascular diseases [34–36]. However, it can only assess the longitudinal function of the basal RV free wall and not global RV function.

Fig. 1.

Echocardiographic parameters for the quantitative assessment of RV function. A Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), B right ventricular systolic wave velocity measured with Tissue Doppler Imaging (RV S′), C right ventricular ejection fraction measured by 3D-echocardiography (3DE RVEF), D fractional area change (FAC), E 2D right ventricular global longitudinal strain (GLS). Original image republished without need for permission under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International License from Rana et al. [37]

RV Systolic Wave Velocity (S′)

S′ is the peak systolic velocity of the lateral TV annulus (Fig. 1). It is measured with PW-TDI. It is angle- and load-dependent like TAPSE, and the ultrasound beam should align with the lateral TV annulus. It is a measure of the longitudinal function of the RV base. It has been shown to moderately correlate with MRI-derived RVEF [33] and has prognostic value. An abnormal S′ is defined as < 9.5 cm/s.

Assessment of Global RV Function

RV FAC

RV FAC is evaluated in the RVf4C view. It requires manual tracings of RV endocardial area at end-systole and end-diastole (Fig. 1). It should include the papillary muscles, trabeculations and moderator band. FAC is defined as and is expressed as a percentage. An abnormal FAC is defined as < 35% [24•], whereas British guidelines stipulate abnormal as < 30% in males and < 35% in females [21•].

RVLS

Strain is a dimensionless measure of myocardial deformation. RV longitudinal strain (RVLS) is the longitudinal shortening of fibres between the base and apex of the RV in systole and is expressed as a negative percentage [38]. It is measured by using 2D speckle tracking. It depends heavily on the imaging quality of the endocardial/myocardial borders and should be measured in the RVf4C view with a high frame rate. A standardised protocol for acquisition has been published [21, 25, 39]. Global RVLS can be measured by using either three segments (RV free wall) or six segments (free wall and IVS), as these are more standardised than segmental values. RVLS is less angle- and load-dependent, less affected by translational motion and more reproducible than TAPSE and S′, whilst it can identify subclinical dysfunction and has established prognostic utility [20, 25]. However, it neglects the contribution of the RVOT, and values are affected by vendor specific software. At present, there is no universally agreed reference range [25, 40–43]; however, RVFWLS > −20% can be regarded as abnormal with values > −15% identifying those with severe reduction [25•]. RVLS is the best echocardiographic correlate of MRI-derived RVEF [44–46]. RVLS has demonstrated diagnostic and prognostic roles in heart failure [25, 47, 48], PH [49–56], congenital heart disease, cardiomyopathies and tricuspid regurgitation [57–60]. 3D RV strain imaging is conceptually appealing [61–63], but its clinical utility is less well established.

3DE

Over the past decade improvements in 3D echocardiography (3DE) have led to its incorporation in the assessment of the left heart [64]. This has also led to a growing dataset establishing 3DE as a promising novel way of RV imaging [20, 65]. 3DE can circumvent most of the limitations of 2D parameters and calculate RVEF which is the best measure of global RV function [66–68]. 3DE has the unique advantages of simultaneously allowing assessment of several aspects of the right heart including volumes, function, ejection fraction and TV morphology. 3DE-derived RVEF closely correlates with MRI [69, 70]. In PH, 3DE has characterised RV geometry [70], patterns of RV remodelling [63], haemodynamics [71] and RV-PA coupling [72] and has been correlated with outcomes [73–75]. Limitations of 3DE include its dependency on good image quality (up to 25% cases are not feasible), regular heart rates, need for specific expensive hardware and software, time and expertise [20, 65, 76].

Other indices

The myocardial performance index (MPI) has generally fallen out of favour for TAPSE, S′ and FAC but is still used in some institutions. It should be measured with PW-TDI on the lateral TV annulus. It is defined as the ratio of isovolumic time (contraction and relaxation) to ejection time and an abnormal value is > 0.55. It is load-dependent and invalid in high RA pressures [21, 23]. Assessment of diastolic RV function is less well validated but includes inferior vena cava (IVC) profile, RA size and function (area and strain), PW Doppler of RV inflow, hepatic vein flow and PW-TDI of the TV annulus [21, 24].

Echocardiographic Assessment of RV-PA Coupling

TAPSE:PASP Ratio

This ratio was first proposed and evaluated as a surrogate of RV-PA coupling in a series of patients with HF and showed a prognostic role independent of the severity of LV dysfunction [77–79]. .TAPSE:PASP ratio has also been tested in pre-capillary PH where it correlated with haemodynamics and was an independent predictor of survival [80, 81]. TAPSE:PASP has been validated with invasive RV pressure-volume (P-V) analysis in a small group of patients with severe PAH [82]. Consequently, TAPSE:PASP ratio has been incorporated into the risk assessment algorithm of the 2022 ESC/ERS PH Guidelines [83•] and has a potential role in suspected PH in patients with systemic sclerosis [84]. Its limitations relate to incomplete/inaccurate estimation of PASP from TR jet velocity and IVC profile.

RVFWLS:PASP Ratio

A recent study has highlighted an independent prognostic role for the baseline RV free wall longitudinal strain RVFWLS:PASP ratio in treatment-naive patients with precapillary PH [85]. A preliminary analysis by an independent group has offered some retrospective validation for this parameter in a small cohort using invasive P-V loop analysis [86].

Stress Echocardiography

All of the metrics described above can be evaluated at rest and after peak stress (exercise or with dobutamine). Most of the data so far have been derived from healthy volunteers, but there are several small to medium-sized studies which have evaluated the prognostic role of RV contractile reserve in patients with PH, valve disease and HF [87].

MRI

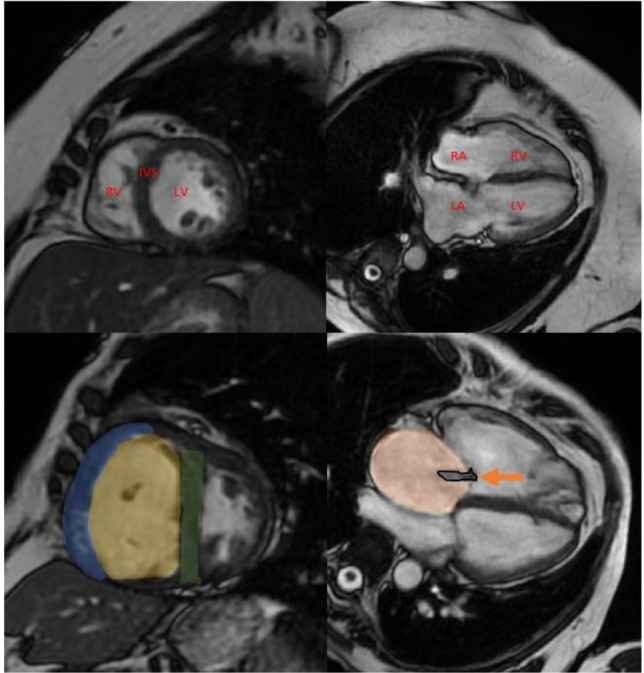

Cine Cardiac MRI

In PH, RV failure is the main determinant of death [83, 88]. MRI is considered the gold-standard for the assessment of RV size and function. The best index of global RV function is RVEF [89]. The volume of the cardiac chambers is built up using multiple slice positions in the short axis orientation with area measurements extrapolated to volume, mass and function measurements. The sequence used is balanced steady state free precession imaging [90]. RV volume and mass can be measured using the Simpson’s method, which involves tracing the RV endocardial border in multiple slices and calculating the total volume by summation. There are different cine views used in PH assessment, including but not limited to the 4-chamber view, short-axis view and axial views. In PH, cine MRI can detect RV dilatation and hypertrophy [91–94], IVS deviation towards the LV [95, 96] (Fig. 2) and PA dilatation and flow abnormalities [97–99]. Models combining these parameters have proven of value to diagnose PH at a tertiary referral setting [100, 101] and using modelling approaches [102]. A recent meta-analysis showed the prognostic power of MRI-derived RV parameters in PAH [103]. Adaptation of the RV to elevated afterload has been assessed by estimation of PA elastance and RV-PA coupling and predicts mortality [104–107]. Patients with RV dilatation without associated hypertrophy have a worse outcome than patients with hypertrophy [108, 109].

Fig. 2.

Cardiac MRI cine images (short-axis: left, four chamber: right). Top row: normal MRI. RV; right ventricle, LV; left ventricle, IVS; interventricular septum, RA; right atrium, LA; left atrium. Bottom row: pulmonary arterial hypertension features including a hypertrophied RV myocardium (blue), dilated RV chamber (yellow), IVS straightening (green), RA enlargement (orange) and tricuspid regurgitation jet (arrow)

4D Flow

Four-dimensional flow (4D) flow is an MRI technology that overcomes limitations of traditional 2D flow imaging in the evaluation of PH. Unlike conventional imaging, 4D flow provides a 3D visualisation of vascular flow and enables accurate assessment of vessel, transvalvular or intra-cavity flow, providing a more comprehensive description of complex flow changes in the pulmonary circulation. In the context of PH, 4D flow has been utilised to identify abnormal flow patterns in the main PA [110, 111], which are correlated with mean PA pressure (mPAP) [112] making its estimation possible. Furthermore, 4D flow allows the characterisation of other physiological vascular parameters, such as main PA wall shear stress, which can affect vascular remodelling and is typically reduced in PH [113]. Further studies are needed to determine the incremental role of 4D flow MRI assessment in PH management.

RV Strain Imaging

The quantification of myocardial deformation strain is an established MRI technique [114]. One method of strain analysis, called “feature tracking”, follows cardiac borders throughout the cardiac cycle on cine images [115, 116]. Biventricular strain impairment in PH can assist in the early detection of right and left heart dysfunction [117–119]. Feature tracking has been used to predict outcomes in patients with PH whilst reduced RV circumferential and longitudinal strain rates are associated with an impaired RVEF [120]. Reduced RA strain and phasic function are markers of disease severity, with decreased RA strain to be associated with decompensated RV function and stiffness [121, 122].

LGE

Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) is an MRI technique that uses gadolinium’s paramagnetic properties to identify areas of myocardial fibrosis [123]. LGE is associated with poor outcomes and increased mortality in cardiomyopathies [124]. However, in PH LGE, particularly at the RV insertion points or IVS, appears to be a consequence of increased mechanical stress and RV remodelling rather than a sign of RV decompensation and poor prognosis [125, 126].

Myocardial T1 and ECV Mapping

Native myocardial T1 mapping is a pixel-by-pixel representation of the longitudinal relaxation times within a tissue, providing surrogate tissue characterisation data that are measured on a standardized scale [127–129]. T1 values post-gadolinium can be used to estimate extracellular volume (ECV), which is calculated by subtracting the T1 values of the myocardium and blood pool pre- and post-contrast, corrected for the haematocrit level [127]. Elevated T1 mapping values and ECV can indicate areas of oedema and fibrosis in the myocardium [140, 141]. Recent studies have investigated their clinical application in PH [142–147]. T1-times are elevated in PH, particularly at the RV insertion points, and are associated with an increased IVS angle and LV eccentricity [142, 145]. However, the diagnostic application of T1 mapping in PH remains limited [142, 144, 148].

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Perspectives

A major strength of MRI is its high repeatability with a great value in the assessment of cardiac changes in response to PAH therapy [149]. The 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines [93•] have included thresholds for key RV parameters for mortality prediction. MRI limitations include its high cost and reduced availability compared to echocardiography. The future of image acquisition and analysis is bright with the revolution in machine learning which has offered the potential to improve the speed of image acquisition [150], image quality [151] and automation of RV measurements and their conversion into text reports via natural language processing. Progress has also been made in PH with artificial intelligence (AI), which has demonstrated higher repeatability in measurements, closer correlations with invasive haemodynamics and better survival prediction [152, 153].

Invasive Haemodynamics

Direct measurement of four pulmonary haemodynamic parameters — RA pressure (RAP), PAP, PA wedge pressure (PAWP) and cardiac output (CO) — via right heart catheterisation (RHC) allows assessment of RV preload, afterload, function and PAC (Table 2). RHC with a fluid-filled Swan-Ganz catheter is most commonly performed via the internal jugular vein but may also be performed via the brachial or femoral veins [154].

Table 2.

Haemodynamic parameters derived from standard right heart catheterisation

| Parameter | Definition |

|---|---|

| RAP/PAWP ratio | |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) | |

| Total pulmonary resistance (TPR) | |

| Stroke volume (SV) | |

| Stroke volume index (SVi) | |

| PA compliance | |

| RV stroke work index (RVSWi) | |

| PA pulsatility index (PAPi) |

RAP right atrial pressure, PAWP pulmonary arterial wedge pressure, mPAP mean pulmonary arterial pressure, CO cardiac output, CI cardiac index, SV stroke volume, PASP pulmonary arterial systolic pressure, PADP pulmonary arterial diastolic pressure, PAP pulmonary arterial pressure, RV right ventricular

RAP

RAP reflects central venous pressure but can also be increased in severe TR and impaired RV and RA compliance [155]. In the context of PAH, RV pressure and volume overload results in impaired filling leading to elevated RAP. In PAH, PAWP is higher than RAP until RV failure occurs at which point the RAP:PAWP will rise above 1. This ratio has been identified as a strong prognostic marker, outperforming RAP and several other haemodynamic parameters in two large cohorts of PAH patients [156].

CO

CO may be assessed via RHC by thermodilution (TD), the direct Fick (DF) or indirect Fick (IF) technique [157•]. TD involves injection of cooled saline into the proximal port of the Swan-Ganz catheter. The decrease in temperature between the RA and the distal thermistor produces a TD curve from which CO is computer-generated. DF and IF methods rely on the Fick equation:

where VO2 = oxygen consumption; Ca = arterial oxygen content = systemic oxygen saturation (SaO2, %) × haemoglobin (g/dL) × 1.34/100 and Cv = mixed venous oxygen content = mixed venous saturation (SvO2, %) × haemoglobin (g/dL) × 1.34/100. The DF method is recognised as the gold-standard method but relies on direct measurement of VO2 which requires specialised equipment in the catheter suite which is not widely available. The TD method has been shown to be a reliable method of measuring CO when compared with DF, even in patients with TR or low outputs [158, 159]. The IF method has poor accuracy and precision when compared to DF [159]. Current ESC/ERS guidelines recommend the use of either DF or TD techniques apart from patients with intra-cardiac shunts where TD is inaccurate [93•].

RV SV can simply be calculated by dividing CO by heart rate (HR). SV indexed for body surface area ( ) has been found to outperform standard haemodynamics in large cohorts of PAH patients [160]. RV stroke work index (RVSWI) is a further derived parameter (RVSWI = 0.0136 × SVi × (mPAP-RAP)), which aims to reflect effective work performed by the RV in every cardiac cycle but has limited supportive data in PAH [161]. PA pulsatility index (PAPi) calculated by the equation , where PADP is PA diastolic pressure, relates the ability of the RV to produce SV to its filling pressure and has been shown to be strongly predictive of survival in patients with advanced HF, but its role in PAH is less clear [162].

RV Contractility

CO and derived haemodynamic parameters such as SVi and RVSWI as well as imaging-derived markers of RV systolic function such as TAPSE, FAC and RVEF are all load-dependent. In addition to preload and afterload, RV function is also determined by intrinsic contractility which relates to myocardial shortening and will be impacted positively or negatively by processes such as compensatory hypertrophy or diffuse fibrosis. Ees is the gold-standard measure for RV contractility but cannot be assessed via standard RHC [155, 163]. Instead, P-V loop assessment is performed which requires the use of a conductance catheter which measures both pressure and volume within the RV. Ees is calculated by performing multiple P-V loops at different preloads (achieved by progressive IVC compression with an intravenous balloon or Valsalva). The gradient of the line connecting the different end-systolic points (end systolic pressure-volume relationship) is Ees [164]. This multi-point technique is technically challenging and so a single-beat method has been developed [165]. Although the single-beat method is technically less challenging, it has poor reproducibility and prognostic capability in PH [166]. Instead of using a conductance catheter, Ees can also be obtained by combining RHC (to measure pressure) and CMR (to measure volumes) based on the equation: where ESV is end-systolic volume [167].

RV Afterload

RV afterload consists of PVR and PAC. Total RV afterload can be described by Ea which can be derived from P-V loops: [165].

The relationship between RV load-independent function and RV afterload (RV-PA coupling) can therefore be described as the ratio between Ees and Ea. Ees:Ea should ideally be between 1 and 2. A recent study comparing RHC-derived Ees:Ea with CMR parameters demonstrated that Ees:Ea of < 0.8 was the best threshold indicating RV failure [168]. Interestingly a non-invasive CMR surrogate for RV-PA coupling, was at least as useful in identifying impending RV failure [168].

PVR, which accounts for ≈75% of RV afterload, is calculated using the equation . This therefore relies on accurate measurement of both mPAP and PAWP. These should ideally be measured at end-expiration (functional residual capacity) when intra- and extra-thoracic pressures should be equivalent [157•]. Large respiratory swings in obesity, at exercise or in the presence of significant lung disease can make this difficult and in these situations, it is recommended that a computerised average is used [93•].

PAC may be calculated using the 2-element Windkessel model; however, the simplest way of estimating it is by using the equation , where PP is pulse pressure i.e. PASP-PADP [169, 170]. Increased PAC leads to greater pulse wave reflection during systole which results in higher PASP requirements and hence higher RV energy requirements to create the same ejection.

The relationship between PVR and PAC (the resistance-compliance or RC time) represents the diastolic decay constant of PAP and in most conditions is constant, suggesting that most of both resistance and compliance occurs in the more distal vasculature [171].

Conclusions

A systematic evaluation of RV size and function requires the use of several parameters derived from different invasive and non-invasive modalities. 2DE and 3DE as well as speckle tracking can provide a quantitative assessment of RV systolic performance. MRI-derived RVEF remains the gold-standard metric of RV global function and can be used in a serial manner to assess response to treatment and disease progression in PH. RHC is not only the gold-standard method for the diagnosis of PH, but it can also estimate CO, RV contractility and RV-PA coupling. It is imperative for the clinician to know the strengths and weaknesses of its test and use them in a complementary fashion accordingly (Fig. 3). Machine learning and AI methods may in the future help us to overcome the obstacles of RV complex shape and physiology and offer a more accurate and reproducible assessment of its global function.

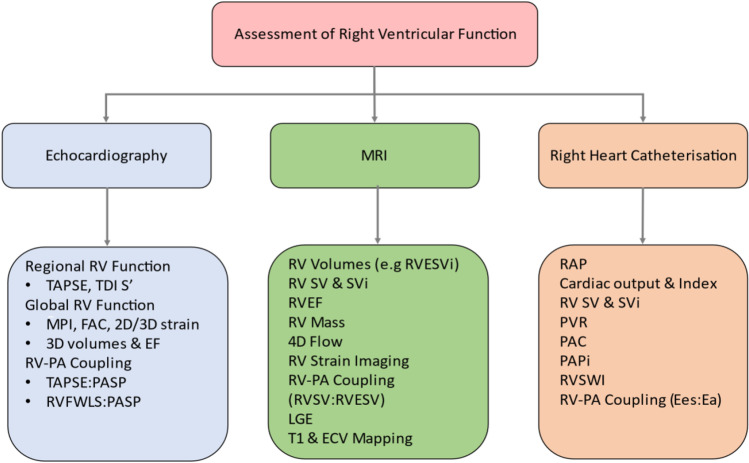

Fig. 3.

Modalities and parameters used for the assessment of right ventricular function. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RV, right ventricular; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TDI S′, right ventricular systolic wave on Tissue Doppler Imaging; MPI, myocardial performance index; FAC, fractional area change; EF, ejection fraction; PA, pulmonary artery; PASP, pulmonary arterial systolic pressure; RVFWLS, right ventricular free wall longitudinal strain; RVESVi, right ventricular end-systolic volume index; SV, stroke volume; SVi, stroke volume index; RVSV, right ventricular stroke volume; RVESV, right ventricular end-systolic volume; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; ECV, extracellular volume; RAP, right atrial pressure, PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; PAC, pulmonary arterial compliance; PAPi, pulmonary arterial pulsatility index; RWSVI, right ventricular stroke work index; Ees, end-systolic elastance; Ea, arterial elastance

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

A Hameed, R Condliffe, A J Swift, S Alabed, D J Kiely, and A Charalampopoulos declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

- 1.Lippmann MR, Maron BA. The right ventricle: from embryologic development to RV failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2022;19:325–333. doi: 10.1007/s11897-022-00572-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loukas M, Klaassen Z, Tubbs RS, et al. Anatomical observations of the moderator band. Clin Anat. 2010;23:43–50. doi: 10.1002/ca.20968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown SB, Raina A, Katz D, et al. Longitudinal shortening accounts for the majority of right ventricular contraction and improves after pulmonary vasodilator therapy in normal subjects and patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2011;140:27–33. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker LA, Buttrick PM. The right ventricle: biologic insights and response to disease: updated. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2013;9(1):73–81. doi: 10.2174/157340313805076296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guimaron S, Guihare J, Amsallem M, Haddad F, Fadel E, Mercier O. Current knowledge and recent advances of right ventricular molecular biology and metabolism from congenital heart disease to chronic pulmonary hypertension. Biomed Res Int. 2018;17(2018):1981568). doi: 10.1155/2018/1981568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheehan F, Redington A. The right ventricle: anatomy, physiology, and clinical imaging. Heart. 2008;94:1510–1515. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.132779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naeije R, Badagliacca R. The overloaded right heart and ventricular interdependence. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113:1474–1485. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vonk Noordegraaf A, Chin KM, Haddad F, Hassoun PM, Hemnes AR, Hopkins SR, Kawut SM, Langleben D, Lumens J, Naeije R. Pathophysiology of the right ventricle and of the pulmonary circulation in pulmonary hypertension: an update. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801900. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01900-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suga H, Sgawa K, Shoukas AA. Load independence of the instantaneous pressure-volume ratio of the canine left ventricle and effects of epinephrine and heart rate on the ratio. Circ Res. 1973;32:314–322. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.32.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lankhaar J-W, Westerhof N, Faes TJC, et al. Pulmonary vascular resistance and compliance stay inversely related during treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1688–1695. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pellegrini P, Rossi A, Pasotti M, Raineri C, Cicoira C, Bonapace S, et al. Prognostic relevance of pulmonary arterial compliance in patients with chronic heart failure. Chest. 2014;145:1064–1070. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tampakakis E, Shah JS, Borlaug BA, Leary PJ, Patel HH, Miller WL, et al. Pulmonary effective arterial elastance as a measure of right ventricular afterload and its prognostic value in pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(4):e004436. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyon RC, Zanella F, Omens JH, Sheikh F. Mechanotransduction in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Circ Res. 2015;116:1462–1476. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Haddad F, Chin KM, et al. Right heart adaptation to pulmonary arterial hypertension: physiology and pathobiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:D22–D33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogel-Claussen J, Skrok J, Shehata ML, et al. Right and left ventricular myocardial perfusion reserves correlate with right ventricular function and pulmonary hemodynamics in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Radiology. 2011;258:119–127. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Wolferen SA, Marcus JT, Westerhof N, et al. Right coronary artery flow impairment in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:120–127. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vonk Noordergraaf A, Westerhof BE, Westerhof N. The relationship between the right ventricle and its load in pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konstam M, Kiernan M, Bernstein D, et al. AHA Scientific Statement. Evaluation and management of right-sided heart failure. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e578–e622. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arrigo M, Huber LC, Winnik S, Mikulicic F, Guidetti F, Frank M, Flammer A, Ruschitzka F. Right ventricular failure: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Card Fail Rev. 2019;5(3):140–146. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2019.15.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Surkova E, Cosyns B, Gerber B, Gimelli A, la Gerche A, Ajmone MN. The dysfunctional right ventricle: the importance of multi-modality imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23(7):885–897. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEAC037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaidi A, Knight DS, Augustine DX, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a practical guideline from the British Society of Echocardiography. Echo Res Pract. 2020;7(1):G19–G41. doi: 10.1530/ERP-19-0051/METRICS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Augustine DX, Coates-Bradshaw LD, Willis J, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary hypertension: a guideline protocol from the British Society of Echocardiography. Echo Res Pract. 2018;5(3):G11–G24. doi: 10.1530/ERP-17-0071/METRICS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography: endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(7):685–713. doi: 10.1016/J.ECHO.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16(3):233–271. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEV014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muraru D, Haugaa K, Donal E, et al. Right ventricular longitudinal strain in the clinical routine: a state-of-the-art review. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23(7):898–912. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeac022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Genovese D, Mor-Avi V, Palermo C, et al. Comparison between four-chamber and right ventricular–focused views for the quantitative evaluation of right ventricular size and function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019;32(4):484–494. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaidi A, Oxborough D, Augustine DX, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of the tricuspid and pulmonary valves: a practical guideline from the British Society of Echocardiography. Echo Res Pract. 2020;7(4):G95–G122. doi: 10.1530/ERP-20-0033/METRICS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aalen JM, Smiseth OA. Strain identifies pseudo-normalized right ventricular function in tricuspid regurgitation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;22(8):876–877. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEAB089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ancona F, Melillo F, Calvo F, et al. Right ventricular systolic function in severe tricuspid regurgitation: prognostic relevance of longitudinal strain. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;22(8):868–875. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEAB030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badano LP, Caravita S, Rella V, Guida V, Parati G, Muraru D. The added value of 3-dimensional echocardiography to understand the pathophysiology of functional tricuspid regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(3):683–689. doi: 10.1016/J.JCMG.2020.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kresoja KP, Rommel KP, Lücke C, et al. Right ventricular contraction patterns in patients undergoing transcatheter tricuspid valve repair for severe tricuspid regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(14):1551–1561. doi: 10.1016/J.JCIN.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaul S, Tei C, Hopkins JM, Shah PM. Assessment of right ventricular function using two-dimensional echocardiography. Am Heart J. 1984;107(3):526–531. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pavlicek M, Wahl A, Rutz T, et al. Right ventricular systolic function assessment: rank of echocardiographic methods vs. cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011;12(11):871–880. doi: 10.1093/EJECHOCARD/JER138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Damy T, Kallvikbacka-Bennett A, Goode K, et al. Prevalence of, associations with, and prognostic value of tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) among out-patients referred for the evaluation of heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012;18(3):216–225. doi: 10.1016/J.CARDFAIL.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forfia PR, Fisher MR, Mathai SC, et al. Tricuspid annular displacement predicts survival in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(9):1034–1041. doi: 10.1164/RCCM.200604-547OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aloia E, Cameli M, D’Ascenzi F, Sciaccaluga C, Mondillo S. TAPSE: an old but useful tool in different diseases. Int J Cardiol. 2016;225:177–183. doi: 10.1016/J.IJCARD.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rana BS, Robinson S, Francis R, et al. Tricuspid regurgitation and the right ventricle in risk stratification and timing of intervention. Echo Res Pract. 2019;6:R26–R40. doi: 10.1530/ERP-18-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voigt JU, Cvijic M. 2- and 3-Dimensional myocardial strain in cardiac health and disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(9):1849–1863. doi: 10.1016/J.JCMG.2019.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badano LP, Kolias TJ, Muraru D, et al. Standardization of left atrial, right ventricular, and right atrial deformation imaging using two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography: a consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19(6):591–600. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEY042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Landzaat JWD, van Heerebeek L, Jonkman NH, van der Bijl EM, Riezebos RK. The quest for determination of standard reference values of right ventricular longitudinal systolic strain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Echocardiogr. 2023;21(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s12574-022-00592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang TKM, Grimm RA, Leonardo Rodriguez L, Collier P, Griffin BP, Popovic ZB. Defining the reference range for right ventricular systolic strain by echocardiography in healthy subjects: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0256547. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0256547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Addetia K, Miyoshi T, Citro R, et al. Two-dimensional echocardiographic right ventricular size and systolic function measurements stratified by sex, age, and ethnicity: results of the World Alliance of Societies of Echocardiography study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2021;34(11):1148–1157.e1. doi: 10.1016/J.ECHO.2021.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muraru D, Onciul S, Peluso D, et al. Sex- and method-specific reference values for right ventricular strain by 2-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(2) 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003866. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Lu KJ, Chen JXC, Profitis K, et al. Right ventricular global longitudinal strain is an independent predictor of right ventricular function: a multimodality study of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, real time three-dimensional echocardiography and speckle tracking echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2015;32(6):966–974. doi: 10.1111/ECHO.12783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agasthi P, Chao CJ, Siegel RJ, et al. Comparison of echocardiographic parameters with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of right ventricular function. Echocardiography. 2020;37(11):1792–1802. doi: 10.1111/ECHO.14877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, Zhang L, Gao Y, et al. Comprehensive assessment of right ventricular function by three-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography: comparisons with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2021;34(5):472–482. doi: 10.1016/J.ECHO.2020.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tadic M, Nita N, Schneider L, et al. The predictive value of right ventricular longitudinal strain in pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, and valvular diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:598. doi: 10.3389/FCVM.2021.698158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rudski LG, Fine NM. Right ventricular function in heart failure: the long and short of free wall motion versus deformation imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(1):e007396. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.007396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fine NM, Chen L, Bastiansen PM, et al. Outcome prediction by quantitative right ventricular function assessment in 575 subjects evaluated for pulmonary hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(5):711–721. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amsallem M, Sweatt AJ, Aymami MC, et al. Right heart end-systolic remodeling index strongly predicts outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(6) 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.da Costa Junior AA, Ota-Arakaki JS, Ramos RP, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of right ventricular strain in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension and relatively preserved functional capacity studied with echocardiography and magnetic resonance. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;33(1):39–46. doi: 10.1007/S10554-016-0966-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hulshof HG, Eijsvogels TMH, Kleinnibbelink G, et al. Prognostic value of right ventricular longitudinal strain in patients with pulmonary hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20(4):475–484. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEY120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li AL, Zhai ZG, Zhai YN, Xie WM, Wan J, Tao XC. The value of speckle-tracking echocardiography in identifying right heart dysfunction in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;34(12):1895–1904. doi: 10.1007/S10554-018-1423-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Badagliacca R, Pezzuto B, Papa S, et al. Right ventricular strain curve morphology and outcome in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(1):162–172. doi: 10.1016/J.JCMG.2020.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muraru D, Badano L. Disease staging and outcome in pulmonary hypertension: deciphering the right pattern. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(1):173–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hulshof HG, van Dijk AP, Hopman MTE, et al. 5-Year prognostic value of the right ventricular strain-area loop in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;22(2):188–195. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEAA143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prihadi EA, van der Bijl P, Dietz M, et al. Prognostic implications of right ventricular free wall longitudinal strain in patients with significant functional tricuspid regurgitation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(3):8666. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.118.008666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Romano S, Dell’atti D, Judd RM, et al. Prognostic value of feature-tracking right ventricular longitudinal strain in severe functional tricuspid regurgitation: a multicenter study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(8):1561–1568. doi: 10.1016/J.JCMG.2021.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Furlani AC, Garcia MJ. Right ventricular strain: getting closer to solving the tricuspid valve enigma. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(3):8862. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.119.008862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muthurangu V. Right ventricular longitudinal strain: a better predictor of outcome in patients with severe tricuspid regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(8):1569–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith BCF, Dobson G, Dawson D, Charalampopoulos A, Grapsa J, Nihoyannopoulos P. Three-dimensional speckle tracking of the right ventricle: toward optimal quantification of right ventricular dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blanchard DG, DeMaria AN. Right ventricular 3-dimensional strain in pulmonary hypertension: the quest to see the future. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(1):52–53. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2014.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ryo K, Goda A, Onishi T, et al. Characterization of right ventricular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension associated with patient outcomes by 3-dimensional wall motion tracking echocardiography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(6) 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.003176. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Lang RM, Addetia K, Narang A, Mor-Avi V. 3-Dimensional echocardiography: latest developments and future directions. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(12):1854–1878. doi: 10.1016/J.JCMG.2018.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Muraru D. 22nd Annual Feigenbaum lecture: right heart, right now: the role of three-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2022;35(9):893–909. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2022.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Addetia K, Lang RM. Decoding the right ventricle in 3 dimensions. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(10):910–911. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fernández-Golfín C, Zamorano JL. Three-dimensional echocardiography and right ventricular function. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(2):6099. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.006099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muraru D, Spadotto V, Cecchetto A, et al. New speckle-tracking algorithm for right ventricular volume analysis from three-dimensional echocardiographic data sets: validation with cardiac magnetic resonance and comparison with the previous analysis tool. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17(11):1279–1289. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEV309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Otani K, Nabeshima Y, Kitano T, Takeuchi M. Accuracy of fully automated right ventricular quantification software with 3D echocardiography: direct comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance and semi-automated quantification software. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21(7):787–795. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEZ236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bidviene J, Muraru D, Maffessanti F, et al. Regional shape, global function and mechanics in right ventricular volume and pressure overload conditions: a three-dimensional echocardiography study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;37(4):1289–1299. doi: 10.1007/S10554-020-02117-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vitarelli A, Mangieri E, Terzano C, et al. Three-dimensional echocardiography and 2D-3D speckle-tracking imaging in chronic pulmonary hypertension: diagnostic accuracy in detecting hemodynamic signs of right ventricular (RV) failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(3):1–14. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Y, Guo D, Gong J, et al. Right ventricular function and its coupling with pulmonary circulation in precapillary pulmonary hypertension: a three-dimensional echocardiographic study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8 10.3389/FCVM.2021.690606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Liu BY, Wu WC, Zeng QX, et al. The value of three-dimensional echocardiography in risk stratification in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a cross-sectional study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;36(4):577–584. doi: 10.1007/s10554-019-01743-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Murata M, Tsugu T, Kawakami T, et al. Prognostic value of three-dimensional echocardiographic right ventricular ejection fraction in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Oncotarget. 2016;7(52):86781–86790. doi: 10.18632/ONCOTARGET.13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jone PN, Schäfer M, Pan Z, Bremen C, Ivy DD. 3D echocardiographic evaluation of right ventricular function and strain: a prognostic study in paediatric pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19(9):1026–1033. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEX205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cosyns B, le Tourneau T, Rudski L. Right here, right now! Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21(1):22–23. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEZ265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guazzi M, Bandera F, Pelissero G, et al. Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion and pulmonary arterial systolic pressure relationship in heart failure: an index of right ventricular contractile function and prognosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305(9) 10.1152/AJPHEART.00157.2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Guazzi M, Dixon D, Labate V, et al. RV contractile function and its coupling to pulmonary circulation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: stratification of clinical phenotypes and outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(10):1211–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gorter TM, van Veldhuisen DJ, Voors AA, et al. Right ventricular-vascular coupling in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and pre- vs. post-capillary pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19(4):425–432. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEX133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tello K, Wan J, Dalmer A, et al. Validation of the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion/systolic pulmonary artery pressure ratio for the assessment of right ventricular-arterial coupling in severe pulmonary hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(9) 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.119.009047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Tello K, Axmann J, Ghofrani AJ, et al. Relevance of the TAPSE/PASP ratio in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2018;1(266):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Richter MJ, Peters D, Ghofrani HA, et al. Evaluation and prognostic relevance of right ventricular-arterial coupling in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(1):116–119. doi: 10.1164/RCCM.201906-1195LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.• 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension | European Heart Journal | Oxford Academic. Accessed February 19, 2023. https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/43/38/3618/6673929

- 84.Colalillo A, Grimaldi MC, Vaiarello V, et al. In systemic sclerosis, the TAPSE/sPAP ratio can be used in addition to the DETECT algorithm for pulmonary arterial hypertension diagnosis. Rheumatology. 2022;61(6):2450–2456. doi: 10.1093/RHEUMATOLOGY/KEAB748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ünlü S, Bézy S, Cvijic M, Duchenne J, Delcroix M, Voigt JU. Right ventricular strain related to pulmonary artery pressure predicts clinical outcome in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;00:1–8. doi: 10.1093/EHJCI/JEAC136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Richter MJ, Rako ZA, Tello K. Ratio between right ventricular strain and systolic pulmonary artery pressure as a surrogate for right ventricular to pulmonary arterial coupling: validation against the gold standard. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022; 10.1093/EHJCI/JEAC253. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Rudski LG, Gargani L, Armstrong WF, et al. Stressing the cardiopulmonary vascular system: the role of echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2018;31(5):527–550.e11. doi: 10.1016/J.ECHO.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kiely DG, Levin D, Hassoun P, Ivy DD, Jone P-N, Bwika J, et al. EXPRESS: statement on imaging and pulmonary hypertension from the Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute (PVRI) Pulm Circ. 2019;9:2045894019841990. doi: 10.1177/2045894019841990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Grothues F, Moon JC, Bellenger NG, Smith GS, Klein HU, Pennell DJ. Interstudy reproducibility of right ventricular volumes, function, and mass with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Am Heart J. 2004;147:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Syed MA, Raman SV, Simonetti OP. Basic principles of cardiovascular MRI: physics and imaging techniques. Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Simpson CE, Kolb TM, Hsu S, Zimmerman SL, Corona-Villalobos CP, Mathai SC, et al. Ventricular mass discriminates pulmonary arterial hypertension as redefined at the Sixth World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2022;12:e12005. doi: 10.1002/pul2.12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hagger D, Condliffe R, Woodhouse N, Elliot CA, Armstrong IJ, Davies C, et al. Ventricular mass index correlates with pulmonary artery pressure and predicts survival in suspected systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Rheumatology. 2009;48:1137–1142. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vogel-Claussen J, Shehata ML, Lossnitzer D, Skrok J, Singh S, Boyce D, et al. Increased right ventricular Septomarginal trabeculation mass is a novel marker for pulmonary hypertension: comparison with ventricular mass index and right ventricular mass. Invest Radiol. 2011;46:567–575. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31821b7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Swift AJ, Rajaram S, Condliffe R, Capener D, Hurdman J, Elliot CA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging of right ventricular morphology and function in the assessment of suspected pulmonary hypertension results from the ASPIRE registry. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14:40. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-14-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dellegrottaglie S, Sanz J, Poon M, Viles-Gonzalez JF, Sulica R, Goyenechea M, et al. Pulmonary hypertension: accuracy of detection with left ventricular septal-to-free wall curvature ratio measured at cardiac MR. Radiology. 2007;243:63–69. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431060067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johns CS, Wild J, Rajaram S, Kiely D, Swift A. Septal angle on MRI predicts combined pre- and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension. Clin Radiol. 2017:S1–2. 10.1016/j.crad.2017.06.043.

- 97.Sanz J, Kariisa M, Dellegrottaglie S, Prat-González S, Garcia MJ, Fuster V, et al. Evaluation of pulmonary artery stiffness in pulmonary hypertension with cardiac magnetic resonance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Boerrigter BG, Mauritz GJ, Marcus JT, Helderman F, Postmus PE, Westerhof N, et al. Progressive dilatation of the main pulmonary artery in pulmonary arterial hypertension is irrespective of changes in pulmonary artery pressure. B59. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: diagnosis, hemodynamic assessment, and imaging. 2010; 10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2010.181.1_meetingabstracts.a3397.

- 99.Sanz J, Kuschnir P, Rius T, Salguero R, Sulica R, Einstein AJ, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: noninvasive detection with phase-contrast MR imaging. Radiology. 2007;243:70–79. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431060477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Whitfield AJ, Solanki R, Johns CS, Kiely D, Wild J, Swift AJ. MRI Prediction of precapillary pulmonary hypertension according to the sixth world symposium on pulmonary hypertension. Radiology. 2020:482–2. 10.1148/radiol.2019192078. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 101.Johns CS, Kiely DG, Rajaram S, Hill C, Thomas S, Karunasaagarar K, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension with cardiac MRI: derivation and validation of regression models. Radiology. 2019;290:61–68. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lungu A, Swift AJ, Capener D, Kiely D, Hose R, Wild JM. Diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension from magnetic resonance imaging–based computational models and decision tree analysis. Pulm Circ. 2016:181–90. 10.1086/686020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 103.Alabed S, Shahin Y, Garg P, Alandejani F, Johns CS, Lewis RA, et al. Cardiac-MRI predicts clinical worsening and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14:931–942. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bartnik A, Pepke-Zaba J, Hoole SP, White P, Garbi M, Coghlan JG, et al. Right ventricular-pulmonary artery coupling in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Heart. 2022; 10.1136/heartjnl-2022-321770. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 105.Tsarova K, Morgan AE, Melendres-Groves L, Ibrahim MM, Ma CL, Pan IZ, et al. Imaging in pulmonary vascular disease-understanding right ventricle-pulmonary artery coupling. Compr Physiol. 2022;12:3705–3730. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c210017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Naeije R, Richter MJ, Rubin LJ. The physiological basis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2022:59. 10.1183/13993003.02334-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 107.Tello K, Dalmer A, Vanderpool R, Ghofrani HA, Naeije R, Roller F, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging-based right ventricular strain analysis for assessment of coupling and diastolic function in pulmonary hypertension. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:2155–2164. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Badagliacca R, Poscia R, Pezzuto B, Nocioni M, Mezzapesa M, Francone M, et al. Right ventricular remodeling in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: adaptive versus maladaptive morphology. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34:395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Goh ZM, Balasubramanian N, Alabed S, Dwivedi K, Shahin Y, Rothman AMK, et al. Right ventricular remodelling in pulmonary arterial hypertension predicts treatment response. Heart. 2022;108:1392–1400. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2021-320733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Reiter G, Reiter U, Kovacs G, Kainz B, Schmidt K, Maier R, et al. Magnetic resonance–derived 3-dimensional blood flow patterns in the main pulmonary artery as a marker of pulmonary hypertension and a measure of elevated mean pulmonary arterial pressure. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2008:23–30. 10.1161/circimaging.108.780247. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 111.Sieren MM, Berlin C, Oechtering TH, Hunold P, Drömann D, Barkhausen J, et al. Comparison of 4D Flow CMR to 2D Flow CMR in the pulmonary arteries in healthy volunteers and patients with pulmonary hypertension. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0224121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Reiter U, Reiter G, Kovacs G, Stalder AF, Gulsun MA, Greiser A, et al. Evaluation of elevated mean pulmonary arterial pressure based on magnetic resonance 4D velocity mapping: comparison of visualization techniques. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wang Z, Lakes RS, Golob M, Eickhoff JC, Chesler NC. Changes in large pulmonary arterial viscoelasticity in chronic pulmonary hypertension. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Almutairi HM, Boubertakh R, Miquel ME, Petersen SE. Myocardial deformation assessment using cardiovascular magnetic resonance-feature tracking technique. Br J Radiology. 2017:20170072. 10.1259/bjr.20170072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 115.Pedrizzetti G, Claus P, Kilner PJ, Nagel E. Principles of cardiovascular magnetic resonance feature tracking and echocardiographic speckle tracking for informed clinical use. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016; 10.1186/s12968-016-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 116.Vo HQ, Marwick TH, Negishi K. CMR-derived myocardial strain measures in normal subjects. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2018:196–205. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 117.Lin ACW, Seale H, Hamilton-Craig C, Morris NR, Strugnell W. Quantification of biventricular strain and assessment of ventriculo-ventricular interaction in pulmonary arterial hypertension using exercise cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and myocardial feature tracking. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019:1427–36. 10.1002/jCMR.26517. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 118.Kallianos K, Brooks GC, Mukai K, de Carvalho FS, Liu J, Naeger DM, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance evaluation of left ventricular myocardial strain in pulmonary hypertension. Acad Radiol. 2018:129–35. 10.1016/j.acra.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 119.Homsi R, Luetkens JA, Skowasch D, Pizarro C, Sprinkart AM, Gieseke J, et al. Left ventricular myocardial fibrosis, atrophy, and impaired contractility in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension and a preserved left ventricular function. Journal of Thoracic Imaging. 2017:36–42. 10.1097/rti.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 120.de Siqueira MEM, de Siqueira MEM, Pozo E, Fernandes VR, Sengupta PP, Modesto K, et al. Characterization and clinical significance of right ventricular mechanics in pulmonary hypertension evaluated with cardiovascular magnetic resonance feature tracking. J Cardiovasc Mag Res. 2016; 10.1186/s12968-016-0258-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 121.Leng S, Dong Y, Wu Y, Zhao X, Ruan W, Zhang G, et al. Impaired cardiovascular magnetic resonance-derived rapid semiautomated right atrial longitudinal strain is associated with decompensated hemodynamics in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:e008582. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.118.008582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tello K, Dalmer A, Vanderpool R, Ghofrani HA, Naeije R, Roller F, et al. Right ventricular function correlates of right atrial strain in pulmonary hypertension: a combined cardiac magnetic resonance and conductance catheter study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;318:H156–H164. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00485.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Croisille P, Revel D, Saeed M. Contrast agents and cardiac MR imaging of myocardial ischemia: from bench to bedside. Eur Radiology. 2006:1951–63. 10.1007/s00330-006-0244-z. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 124.Gulati A, Jabbour A, Ismail TF, Guha K, Khwaja J, Raza S, et al. Association of fibrosis with mortality and sudden cardiac death in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2013:896. 10.1001/jama.2013.1363. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 125.Biederman RWW. Does late gadolinium enhancement still have value? Right ventricular internal mechanical work, Ea/Emax and late gadolinium enhancement as prognostic markers in patients with advanced pulmonary hypertension via cardiac CMR. Cardiol Res Cardiovasc Med. 2017; 10.29011/2575-7083.000011. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 126.Swift AJ, Rajaram S, Capener D, Elliot C, Condliffe R, Wild JM, et al. LGE patterns in pulmonary hypertension do not impact overall mortality. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2014:1209–17. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 127.Haaf P, Garg P, Messroghli DR, Broadbent DA, Greenwood JP, Plein S. Cardiac T1 mapping and extracellular volume (ECV) in clinical practice: a comprehensive review. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017; 10.1186/s12968-016-0308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 128.Puntmann VO, Peker E, Chandrashekhar Y, Nagel E. T1 Mapping in characterizing myocardial disease: a comprehensive review. Circ Res. 2016;119:277–299. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Messroghli DR, Plein S, Higgins DM, Walters K, Jones TR, Ridgway JP, et al. Human myocardium: single-breath-hold MR T1 mapping with high spatial resolution—reproducibility study. Radiology. 2006:1004–12. 10.1148/radiol.2382041903. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 130.Bull S, White SK, Piechnik SK, Flett AS, Ferreira VM, Loudon M, et al. Human non-contrast T1 values and correlation with histology in diffuse fibrosis. Heart. 2013;99:932–937. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kuruvilla S, Janardhanan R, Antkowiak P, Keeley EC, Adenaw N, Brooks J, et al. Increased extracellular volume and altered mechanics are associated with LVH in hypertensive heart disease, not hypertension alone. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2015:172–80. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 132.Saunders LC, Johns CS, Stewart NJ, Oram CJE, Capener DA, Puntmann VO, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of cardiovascular magnetic resonance native myocardial T1 mapping in patients with pulmonary hypertension. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2018; 10.1186/s12968-018-0501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 133.Roller FC, Wiedenroth C, Breithecker A, Liebetrau C, Mayer E, Schneider C, et al. Native T1 mapping and extracellular volume fraction measurement for assessment of right ventricular insertion point and septal fibrosis in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Radiology. 2017:1980–91. 10.1007/s00330-016-4585-y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 134.Chen YY, Yun H, Jin H, Kong DH, Long YL, Fu CX, et al. Association of native T1 times with biventricular function and hemodynamics in precapillary pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;33:1179–1189. doi: 10.1007/s10554-017-1095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Reiter U, Reiter G, Kovacs G, Adelsmayr G, Greiser A, Olschewski H, et al. Native myocardial T1 mapping in pulmonary hypertension: correlations with cardiac function and hemodynamics. Eur Radiology. 2017:157–66. 10.1007/s00330-016-4360-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 136.Raman SV. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, an issue of heart failure clinics e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Patel RB, Li E, Benefield BC, Swat SA, Polsinelli VB, Carr JC, et al. Diffuse right ventricular fibrosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and pulmonary hypertension. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7:253–263. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mehta BB, Auger DA, Gonzalez JA, Workman V, Chen X, Chow K, et al. Detection of elevated right ventricular extracellular volume in pulmonary hypertension using accelerated and navigator-gated look-locker imaging for cardiac T1 estimation (ANGIE) cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:110. doi: 10.1186/s12968-015-0209-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Swift AJ, Wilson F, Cogliano M, Kendall L, Alandejani F, Alabed S, et al. Repeatability and sensitivity to change of non-invasive end points in PAH: the RESPIRE study. Thorax. 2021;76:1032–1035. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Zucker EJ, Sandino CM, Kino A, Lai P, Vasanawala SS. Free-breathing accelerated cardiac CMR using deep learning: validation in children and young adults. Radiology. 2021:539–48. 10.1148/radiol.2021202624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 141.Steeden JA, Quail M, Gotschy A, Mortensen KH, Hauptmann A, Arridge S, et al. Rapid whole-heart CMR with single volume super-resolution. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2020;22:56. doi: 10.1186/s12968-020-00651-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Alabed S, Alandejani F, Dwivedi K, Karunasaagarar K, Sharkey M, Garg P, et al. Validation of artificial intelligence cardiac CMR measurements: relationship to heart catheterization and mortality prediction. Radiology. 2022:212929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 143.Alandejani F, Alabed S, Garg P, Goh ZM, Karunasaagarar K, Sharkey M, et al. Training and clinical testing of artificial intelligence derived right atrial cardiovascular magnetic resonance measurements. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2022;24:25. doi: 10.1186/s12968-022-00855-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kovacs G, Avian A, Pienn M, et al. Reading pulmonary vascular pressure tracings. How to handle the problems of zero leveling and respiratory swings. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:252–257. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0269PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.El Hajj MC, Viray MC, Tedford RJ. Right heart failure: a hemodynamic review. Cardiol Clin. 2020;38:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2020.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Fares WH, Bellumkonda L, Tonelli AR, et al. Right atrial pressure/pulmonary artery wedge pressure ratio: a more specific predictor of survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:760–767. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Rosenkranz S, Preston IR. Right heart catheterisation: best practice and pitfalls in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24:642–652. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0062-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Hoeper MM, Maier R, Tongers J, et al. Determination of cardiac output by the Fick method, thermodilution, and acetylene rebreathing in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:535–541. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.9811062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Khirfan G, Ahmed MK, Almaaitah S, et al. Comparison of different methods to estimate cardiac index in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2019;140:705–707. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Weatherald J, Boucly A, Chemla D, et al. Prognostic value of follow-up hemodynamic variables after initial management in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2018;137:693–704. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Ibe T, Wada H, Sakakura K, et al. Right ventricular stroke work index. Int Heart J. 2018;59:1047–1051. doi: 10.1536/ihj.17-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Kochav SM, Flores RJ, Truby LK, et al. Prognostic impact of pulmonary artery pulsatility index (PAPi) in patients with advanced heart failure: insights from the ESCAPE Trial. J Card Fail. 2018;24:453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Kelly RP, Ting CT, Yang TM, et al. Effective arterial elastance as index of arterial vascular load in humans. Circulation. 1992;86:513–521. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.86.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Hsu S. Coupling right ventricular-pulmonary arterial research to the pulmonary hypertension patient bedside. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12:e005715. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Brimioulle S, Wauthy P, Ewalenko P, et al. Single-beat estimation of right ventricular end-systolic pressure-volume relationship. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1625–H1630. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01023.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Vanderpool RR, Pinsky MR, Naeije R, et al. RV-pulmonary arterial coupling predicts outcome in patients referred for pulmonary hypertension. Heart. 2015;101:37–43. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Sanz J, Garcia-Alvarez A, Fernandez-Friera L, et al. Right ventriculo-arterial coupling in pulmonary hypertension: a magnetic resonance study. Heart. 2012;98:238–243. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Tello K, Dalmer A, Axmann J, et al. Reserve of right ventricular-arterial coupling in the setting of chronic overload. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12:e005512. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Segers P, Brimioulle S, Stergiopulos N, et al. Pulmonary arterial compliance in dogs and pigs: the three-element windkessel model revisited. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H725–H731. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Chemla D, Hebert JL, Coirault C, et al. Total arterial compliance estimated by stroke volume-to-aortic pulse pressure ratio in humans. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H500–H505. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.2.H500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Thenappan T, Prins KW, Pritzker MR, et al. The critical role of pulmonary arterial compliance in pulmonary hypertension. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:276–284. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-599FR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Wald RM, Valente AM, Marelli A. Heart failure in adult congenital heart disease: emerging concepts with a focus on tetralogy of Fallot. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25:422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Pradat P, Francannet C, Harris JA, Robert E. The epidemiology of cardiovascular defects, part I: a study based on data from three large registries of congenital malformations. Pediatr Cardiol. 2003;24:195–221. doi: 10.1007/s00246-002-9401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Kakouros N, Cokkinos DV. Right ventricular myocardial infarction: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86:719–728. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2010.103887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, Basso C, Bauce B, Bluemke DA, Calkins H, Corrado D, Cox MG, Daubert JP, Fontaine G, Gear K, Hauer R, Nava A, Picard MH, Protonotarios N, Saffitz JE, Sanborn DM, Steinberg JS, Tandri H, Thiene G, Towbin JA, Tsatsopoulou A, Wichter T, Zareba W. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the Task Force Criteria. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:806–814. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Caforio AL, Calabrese F, Angelini A, et al. A prospective study of biopsy-proven myocarditis: prognostic relevance of clinical and aetiopathogenetic features at diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1326–1333. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Haddad F, Couture P, Tousignant C, Denault AY. The right ventricle in cardiac surgery, a perioperative perspective, I: anatomy, physiology, and assessment. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:407–421. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818f8623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Haddad F, Couture P, Tousignant C, Denault AY. The right ventricle in cardiac surgery, a perioperative perspective, II: pathophysiology, clinical importance, and management. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:422–433. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818d8b92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Vecht RJ, Carmichael DJS, Gopal R, Philip G. Uhl’s anomaly. Br Heart J. 1979;41:676–682. doi: 10.1136/hrt.41.6.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]