Abstract

This paper examines the relationship between hotels' official ratings and customer review scores. Hotel ratings aim to provide an objective assessment of the hotel's quality and experience to potential customers. However, customer reviews frequently differ from official ratings. We use data on hotels in Dubai to explore their relationship and analyze their similarities and differences. Asymmetric information hampers demand in the hotel industry if ratings do not match the customers' views of quality. Furthermore, substantial discrepancies between the two measures provide competing interests for hotel managers to satisfy rating agencies' criteria or customers' preferences, reducing the hotels' efficiency and effectiveness in offering customers the best experience and value. Our findings show that, as expected, Star Rating primarily reflects hotel-related features. In contrast, customer review scores tend to appreciate features nearby in addition to hotel amenities. Also, some hotel amenities value differently in the customer review scores and Star Rating.

Keywords: Tourism economy, Hotel quality, Hotel attributes, Asymmetric information, Hotel location, Local amenities

1. Introduction

The hotel service is an experience good. An experience good is a product or service where its features and characteristics, such as quality, are difficult to observe in advance, but they become known upon consumption [1]. Any information that can help the customer better understand the characteristics and quality of an experience good can be critical to a well-functioning market. Despite considerable efforts by hotels to provide customers with reliable and relevant information (rating systems, promotional communications, etc.), the industry is rife with an asymmetric information problem in the sense of Akerlof [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. Lack of reliable and relevant information on quality is a major obstacle to a well-functioning hotel market and could present challenges to growth and improvement in the hospitality industry. Since its inception, the hotel industry has relied on ratings and other measures provided by agencies, organizations, and associations to circumvent the information asymmetry problem regarding hotel quality and experience [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. Trustworthy ratings have been a cornerstone of any flourishing hospitality market [[10], [11], [12]]. People generally dislike uncertainty [13,14]. Customer reviews usually reduce uncertainty in online shopping [[15], [16], [17]], and positive reviews stimulate actual purchases [18,19]. Travelers who have searched for a hotel for their next vacation or business trip recognize and appreciate the ratings provided by trusted and reliable sources. However, with the ever-increasing prevalence of the internet, the information on hotels' characteristics and attributes and the customers’ experiences, reviews, and scores have become increasingly available directly to travelers. eWOM (electronic word of mouth), a staple feature of online customer-to-customer communication, reduces information asymmetry of lesser-known hotels more than higher-quality hotels [5,10,16]. Specialized sites, such as Tripadvisor.com, and customer reviews and scores provided by the travel sites, such as Booking.com and Expedia.com, have significantly contributed to resolving the quality information problem in the travel and hotel industries [20]. They also provide review scores that have simplified comparisons.

The customers’ view of hotel quality is largely subjective and depends on their perception of its characteristics, amenities, services, location, and even the room price. Reviews and scores typically result from a reaction of a selective group of highly motivated customers to an abnormal and extreme experience. They may be biased or based on superficial information or inadequate observation. In addition, the large number of reviews makes it costly for customers to read them and draw conclusions. Since these issues can make it difficult for customers to make decisions confidently, authentication of such reviews and scores may constitute a basis for future demand as the experience of past customers is a criterion for choosing a hotel by prospective customers [21].

On the other hand, agencies, organizations, associations, and occasionally governments provide official ratings. Hotels usually are assessed by professional inspectors and travel writers to establish official ratings. Most official rating criteria are based on observable features of a hotel, such as room size, furnishings, recreational facilities, and other amenities. Official ratings aim to provide an objective, consistent, and standardized assessment of hotel quality and experience to potential customers. At the same time, official ratings could influence the commercial success of a hotel [4,22] and could also improve customer satisfaction. Therefore, most travelers still rely on official ratings as a measure of quality rather than spending a considerable amount of time sifting through the endless number of reviews. Also, official ratings are more standardized and easier to compare across hotels and even countries than customer reviews [23].

An important question is how consistent the official ratings and the customer review scores are. Considerable discrepancies between the two measures could introduce significant inefficiency in the industry. It provides the industry managers with conflicting interests to satisfy rating agencies' criteria and requirements or customers' preferences, thereby reducing the hotels' efficiency and effectiveness in offering customers the best experience and value. It could also erode the customers’ trust in either measure and reduce market activity, potentially aggravating the inherent asymmetric information problem in the market.

The reaction of travelers to different hotel services, facilities, and other amenities and their actual satisfaction from these factors are likely to vary across destination locations, cultures, climates, etc. Thus, it is crucial to establish, review, and revise the measures and the composition of the factors that determine reliable and objective official ratings locally, such as those developed for restaurants in Newcastle, UK [24] and tour packages in the UK [25]. Hence, empirical investigations of the relationship between official ratings and customer satisfaction at a particular location are critical to the development and success of the industry in the area. However, ensuring that the official rating calculations are adjusted to reflect true customer perceptions of quality in that region is vital.

Our goal in this paper is to compare and contrast the official ratings and customer review scores, particularly in the flourishing hospitality market in Dubai. Dubai has attracted a large number of visitors and residents thanks to successful growth policies pursued by the government in close collaboration with the private sector. Tourism and hospitality have played a significant role in this achievement. The strategic location of Dubai makes it a popular stopover for international travelers transiting between Europe, Asia, and the rest of the Middle East [26]. In testimony to this, Dubai is ranked fourth globally based on the number of visitors in 2018. The main airport of Dubai, the Dubai International Airport, DXB, has been used by 90 million passengers, where the number of passengers using Dubai International Airport (DXB) increased at an average annual rate of 8.3% between 2010 and 2018 [27]. Dubai surpasses the world average in terms of the number of air trips adjusted for the population [28]. In addition, Colliers Internationals’ report in 2018 indicates that about 37% of airline passengers visit or stay in Dubai, and the rest are transit passengers [29].

To accommodate the large volume of visitors, the number of hotels increased by 4% annually between 2010 and 2018, showing a healthy increase of 7.5% annually in hotel rooms. The strong growth in the tourism industry has brought growth to the ancillary sectors such as food, aviation, and services. In 2018, the accommodation and food industry reached 5.1% of Dubai real GDP, and the share of the sector's employment represented 7.6% of the Dubai labor market. In 2019, closely related industries, such as hospitality, tourism, and aviation, comprised about 25% of Dubai's GDP, with aviation contributing 13.3% [30] and tourism contributing 11.5% [31]. All these do not account for the multiplier effect with likely spillovers in other industries. In an open and competitive hotel market like Dubai, which caters to all types of visitors, hotel managers and entrepreneurs should correctly gauge customers' perception of the quality of their hotels and accordingly adjust their hospitality services. This issue is particularly important given that previous research shows businesses care about online consumer reviews [32]. Likewise, hotel customers need to have a reliable and unbiased measure of quality in choosing their stay during their time away from home.

This paper investigates the long-run and stable relationship between official ratings and customer reviews for about 250 hotels in Dubai to identify and analyze their similarities and differences. We use the Star Rating (henceforth SR) as the official measure of quality and Customer Review Scores (henceforth CRS) from Booking.com as a measure of customer satisfaction and customers’ perceptions of the hotel quality. To our knowledge, there have not been any studies explicitly focused on the relationship between the Star rating (SR) and customer review score (CRS) of hotels in the Middle East, and more specifically, Dubai.

The next section provides a brief literature review on the relationship between official hotel ratings and customer review scores. In sections III and IV, we first detail the background information on the star rating (i.e., the official rating used for hotels in the UAE), and then we provide the details on the Booking.com customer review scores, respectively. Section V introduces the variables and data we use in our empirical study and provides a brief statistical analysis of the main variables. In Section VI, we list our empirical models and specifications. Section VII explains the estimation results and uses them to compare and contrast the official ratings and customer reviews. Section VIII summarizes our findings and concludes.

2. Literature review

Akerlof [2] shows that asymmetric information can significantly reduce market activities. The hotel industry has grappled with the asymmetric information problem since its inception [[3], [4], [5]]. It is recognized that providing reliable and relevant information to potential customers is immensely important to the industry's success. Official ratings and promotional communications have been the main tools to lessen the asymmetric information problem. However, they only imperfectly and partially measure the customers' experience. Thus, improving these measures could improve the industry outcome. Past research shows that customers traditionally rely on the opinions of other customers, including family and friends, to gather reliable and useful information, rather than sellers [33] or travel agents while planning for travel [34].

With the expansion of the internet over the past decades, the emergence of electronic word of mouth (eWOM) has resulted in a paradigm shift in consumers’ decision-making. Nowadays, eWOM is the primary means of gathering travel information [35], and eWOM has practically replaced WOM [[36], [37], [38]]. The tourism industry, especially hotels, is the largest beneficiary of eWOM [39]. Internet and eWOM allow both small- and large-scale hotels to benefit from the availability of information about their hotels to potential customers and likely increase their customer base. However, among hotels, the primary beneficiaries of the easy spread of online information are lesser-known hotels rather than the big ones. This is because lesser-known hotels (usually smaller hotels that are not part of hotel chains) would have a harder time signaling their quality and unique selling points to potential customers. Indeed, larger and better-known hotels, including hotel chains, have a significant advantage in signaling their quality and spreading their selling messages via marketers and advertisers. However, recent studies show that customers rely on online reviews more than formal promotional communications [33,[40], [41], [42]]. Previous research also suggests that eWOM helps enhance brand familiarity for lesser-known hotels increasing the chances of attracting customers [43,44]. Even the mere number of comments online makes a difference for the lesser quality hotels [45], augmenting the possibility of their customer base.

Accordingly, this topic continues to attract considerable academic interest, and studies have found that over 70% of travelers refer to online reviews [46], and online reviews are the number one factor considered in making travel-related decisions [38]. In fact, online reviews from past customers of a product have been considered both a compliment and a substitute to officially mandated ratings for a good or service [47], creating a branding of its own. The need for a supplementary source of rating to the star ratings becomes even clearer because hotel classifications are often inconsistent and usually difficult to compare across countries [48,49]. In short, travelers use a mix of quality indicators such as eWOM and official ratings (e.g., Star rating) to judge the hotel quality [39,50], though the eWOM is becoming more influential.

On the supply side, increasing attention is also directed toward online ratings, as studies have shown that they impact sales [51,52], an establishment's reputation [53], and contribute to hotel room price variability within the same Star category [47,[54], [55], [56]].

Even though there has been much discussion surrounding the importance of eWOM in the tourism industry, the literature focusing on comparing and contrasting online customer review scores with star ratings remains sparse. For one, a study focusing on the determinants of hotel room rates in Shanghai, China [47] find that different customer perceptions (i.e., ratings) on online travel agency platform Agoda.com explain 59-70% of the variability in hotel room rates in a particular category. A similar study utilizing 3-star, 4-star, and 5-star hotel data in Lisbon, Portugal, shows that the highest price variabilities due to online ratings can be observed in the higher-end, 5-star category [56]. Martin-Fuentes [57] finds that a hotel's star rating positively correlated with its online rating and that a higher number of reviews positively impact the online review scores. The paper also seeks to determine whether there is any difference between the nature of reviews compared across two major platforms: Booking.com and TripAdvisor. The paper finds that reviews across the two platforms are virtually similar. Its findings are consistent with the conclusions of [55]. Martin-Fuentes [57] notably also finds that the highest correlation between hotel categories and online scores is present in the Middle East and Africa region (0.53 and 0.57 on Booking.com and TripAdvisor, respectively). The author also concludes that hotels with a higher star rating have higher online ratings throughout the whole sample. Finally, Agušaj, Bazdan, and Lujak [55] quantify the relationship between online customer rating, hotel rating, and room pricing power by studying 3-star, 4-star, and 5-star hotel establishments in Dubrovnik-Neretva County in Croatia and report results that align with past studies.

3. Star rating

3.1. What are hotel ratings?

The prime function of hotel ratings is to provide potential guests with straightforward comparative information about hotel amenities, such as view, room quality, room service, food, spa and fitness services, and more recently, on the quality of public services and amenities of the surrounding area. As there is no centralized system of rating hotels internationally, several prominent classification systems have emerged and are being applied in different parts of the world. A popularly adopted rating system is the star rating, which dates back to 1958 when oil and gas company Mobil, through their magazine “Forbes Travel Guide” (formerly Mobil's Travel Guide), rated hotels using stars. Over time, the Forbes Travel Guide has emerged as an online rating guide, having 1288 luxury spas and hotels in 70 countries listed on their website as of 2021—including 24 properties in Dubai. Many countries worldwide use star symbols on a 4- or 5-point scale, where an additional star represents a higher level of quality. Depending on the country and its regulations, many different variants of the star rating have emerged. For example, hotels in the European Hotelstars Union have a superior “S” mark to account for some extra features in a certain-star hotel. Alternatively, countries such as Australia also have half-star increments for their hotels, making it possible to find 1.5-star hotels, for example. In other countries, symbols other than the star are also used, such as the American Automobile Association's (AAA) Diamond ratings, which are being used to classify restaurants and hotels.

In Dubai, the Department of Tourism and Commerce Marketing (DTCM) regulates hotel ratings. The DTCM, formerly known as the Dubai Commerce and Tourism Promotion Board (DCTPB), was established in 1989 and oversaw the development of the tourism sector and services in Dubai, as well as the licensing and classification of hotels. Dubai, and more generally, the UAE, follow the star rating system in Spain, which is carefully regulated with detailed, legally specified guidelines [58]. Hotels are required to file detailed descriptions of their facilities, which are inspected by the DTCM officials. Based on these evaluations, hotels are granted appropriate ratings.

4. Customer review score

4.1. Definition and analysis of the Booking.com guest review score

A rating measure that customers have recently started paying increasing attention to is the online guest review score on Booking.com. The Booking.com guest review score is a compilation of customer experiences listed on the website, which helps users make more well-informed decisions. After customers have checked out of their hotels, they can evaluate the quality of their stay within 90 days. The rating is on a scale of 1–10, where 1 is the lowest and 10 is the highest. The reviews are limited to guests that have booked through Booking.com. It is worth noting that Booking.com allows filtering hotels on the following categories of review scores: “pleasant” or 6+, “good” or 7+, “very good” or 8+, and “superb” or 9+.

4.2. Components

The guest review process consists of required and optional parts. First of all, guests have to rate their experience with a hotel on an overall basis, from 1 to 10, 1 being worst and 10 being best. They are subsequently asked to rate the cleanliness, comfort, value for money, facilities, location, and staff at the hotel from 1 to 10. Guests then have the option to rate the WiFi and breakfast facilities at the hotel. Finally, guests are offered an opportunity to provide open-ended feedback on the hotel. The two optional ratings, as well as the feedback, do not count toward the overall score. Previously, the overall rating of a hotel was calculated as the unweighted average of six components rated by customers; however, since the end of 2019, customers separately decide the overall score themselves, and the only role of Booking.com is essentially to collect and report these scores.

5. Data

This section provides definitions, descriptive statistics, and other statistical analyses of the variables used in the paper. We use a unique dataset collected for this study that consists of information on 250 hotels out of the 380 hotels listed in Dubai on Booking.com, an online travel fare aggregator. Due to missing data for a few hotels, the final number of hotels (observations) in the most restrictive regression is limited to 239 (loss of 11 hotels). However, most of our regressions include the data for 244 or 245 hotels. In addition, we collect and use the location information and star rating of all 380 hotels to construct our economic geography variables. All data collected for this research are related to the long-run and stable hotel market outcome prior to COVID-19 and are not subject to policies and reactions related to the pandemic. We collected the data on customer reviews, star ratings, and hotel amenities and characteristics in February 2020 and before COVID-19 affected the reviews and ratings. The Booking.com review score is based on the guest reviews in the previous 36 months. Also, the star rating application process takes time to be completed, processed by the authorities, and reflected on Booking.com. Thus, the star ratings collected for this study were also established well before the pandemic.

We supplement the data with lists of locational amenities and economic geography variables for our estimations. Table A1 provides a brief definition of the variables. Table A2 reports descriptive statistics of all variables used in the regressions. As explained below, we group the explanatory variables into three main categories: Hotel amenities and characteristics, location-specific attributes, and economic geography variables.

The selection of variables is a challenge for studying a multifaceted concept such as hotel quality. The precise measurement of quality is a vague and subjective concept, especially in the services industry [59]. A large number of studies attempt to define or measure some quality notion by comparing the expectations of customers to actual realizations [60] and using an extensive set of variables [61]. In this sense, in the hotel industry, the effort is concentrated on analyzing survey data. Nevertheless, they do not necessarily model the relationship between quality and hotel features. To illustrate, Xie, Zhang, and Zhang [32] use variables such as the number and average score of customer ratings on several hotel amenities, including cleanliness, room size, location, and hotel star rating, to estimate a revenue function for the hotels. Alternatively, a number of studies consider hotel rooms within the framework of hedonic models (see Ref. [22] and references therein). These models center around the existence of certain features at a hotel to determine its value to potential customers. Those concepts of value usually refer to room prices. We gravitate toward a different angle by taking advantage of available quality indicators, such as star ratings and customer reviews. The justification of these as indicators of quality relies on the fact that while star ratings portend to signal an official measure of quality, the often-mentioned availability of the internet provides another means of quality assessment for customers [62]. We selectively employ some of the variables in the aforementioned studies. To this end, our analysis consists of three main categories of variables, as shown in Table A1, Table A2. These are hotel amenities and characteristics, location-specific attributes, and economic geography variables. In what follows, we provide an extensive discussion to justify the inclusion of various covariates to explain our dependent variable, i.e., measures of hotel quality.

5.1. Dependent variables

The dependent variables of this analysis are measures of hotel quality. We have two quality measures: Star Rating (SR) and customer review score (CRS). As explained above, while the former represents a formal assessment of hotel quality, the latter shows customers’ views of the quality of the hotel. The Star Rating (SR) assigns a discrete rating of 1 to 5-star (discrete values) to every hotel, whereas the customer review score is the average of the review scores by the customers for the hotel, and it is a continuous value ranging from 1 to 10. The customer review scores in our sample actually range from 5.2 to 9.4. As expected, the lowest value, 5.2, belongs to a 1-star hotel and the highest value, 9.4, belongs to a 5-star hotel. However, CRS interestingly varies from 5.2 to 8.9 among the 1-star hotels. The Star Rating is indicated on the Booking.com page for the hotel and is based on the hotel reporting. We collect both measures from Booking.com.

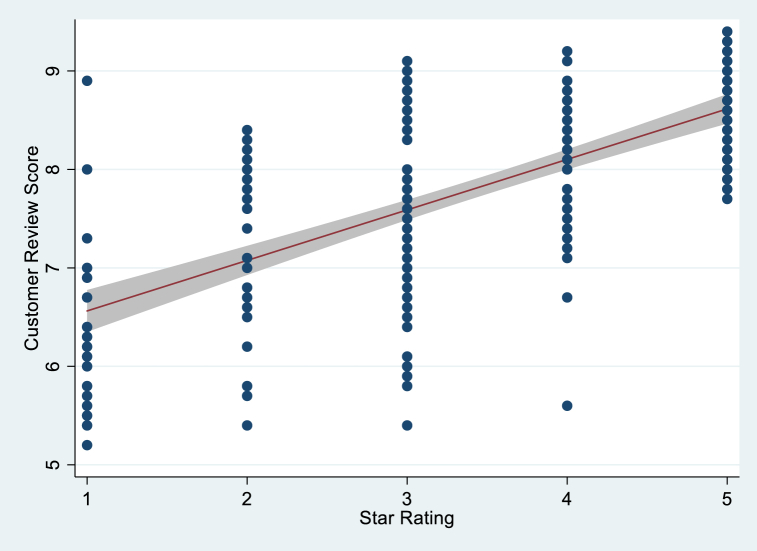

Fig. 1 and Tables A3 show that star rating (SR) and customer review score (CRS) are statistically strongly correlated. The average Star Rating and Customer Review Score for hotels in our sample are 3.49 and 7.84, respectively, and the correlation between the two quality measures is 64%. The mean of CRS increases as SR increases. CRS dispersion is tighter when SR is 5, as shown via the lowest standard deviation (SD) in Table A3 and the tighter distribution of CRS in Fig. 1. In other words, both official raters and customers tend to agree on the quality of upscale hotels. We investigate the direct relationship between CRS and SR in more detail in Section VI.

Fig. 1.

Customer Reviews vs. Star Rating.

On the other hand, customer review scores and star ratings tend to disagree most on hotels in the middle classification (3-star hotels). Customer review scores mainly agree with the official rating for the lowest quality hotels, even though they occasionally rate them highly, as shown in Fig. 1. In particular, some 1-star and 3-star hotels receive high customer scores, which could be attributed to the low price and high value for the money (bargain). Nonetheless, as expected, the highest CRS consistently belongs to hotels on the upper end of the scale.

5.2. Independent variables

The independent variables used in this study broadly cover the hotel amenities, characteristics, location-specific attributes, and economic geography variables (Table A1).

5.3. Hotel amenities

These consist of basic hotel-specific amenities and characteristics, which are all binarily coded (1 if an amenity is available and 0 if it is not), including the availability of a fitness center (gym), spa, and swimming pool in a hotel, and whether there is access to a private beach within the hotel, or whether there is a public beach in the hotel vicinity.

5.4. Location-specific attributes

As locational amenities, we include the ease of access to transportation hubs and tourist attractions. Thus, the location-specific variables include distances, in kilometers, to the city center (Downtown Dubai), to Dubai International Airport, and to the closest metro station. Downtown Dubai is home to many popular tourist destinations, including The Dubai Mall and Burj Khalifa. In our study, the effects of transportation hubs are measured as (i) the distance in kilometers to Dubai International Airport, the primary airport for international flights, and (ii) the distance in kilometers to the nearest metro station. Since distances only up to 750 m are available on Booking.com, the proximities to the nearest metro station for a few hotels are collected using Google Maps.

5.5. Economic geography variables

We construct and use two economic geography variables to account for the potential local competition, localization economies spillovers, and clustering. These variables capture the number of hotels in the immediate vicinity of the hotel and their average quality. The first variable captures local competition [22,63,64]. The number of hotels within 250 m indicates the severity of local competition. The second variable captures the potential effects of localization economies and positive spillovers [22,[65], [66], [67]]. The quality of hotels in the immediate vicinity indicates positive localized spillovers (externalities) because they provide easy access to high-quality services (e.g., restaurants, bars, and entertainment). To incorporate locational effects, we collect basic location information on all 380 hotels listed on Booking.com and calculate the number of hotels (cluster size) and their average quality (using Star Rating) in the hotel's close vicinity. We employ the latitude and longitude coordinates of hotels to compute the distance between them. We identify all hotels within 250 m of being a part of the cluster in the hotel's immediate vicinity.

5.6. Statistical analysis of covariates

As shown in Table A2 and Table A3, we have 250 hotels in the study, of which 23 hotels are 1-star, 27 are 2-star, 70 are 3-star, 65 are 4-star, and 65 are 5-star. There are wide variations among hotel features based on their official Star ratings. For example, while the average size of the room for 5-star hotels exceeds 40 square meters, it is only about 16.5 square meters for 1-star hotels and about 30 square meters for all hotels in our sample. Almost all 5-star hotels have a gym, pool, and spa, whereas none of the 1-star hotels provide such amenities. Hotels largely cluster around downtown, with an average distance to downtown Dubai under 9 km. Also, 1-star hotels are found to be closer to a metro station and 3-star farthest from there, but all hotels are, on average, only slightly more than half a kilometer away from the nearest metro station. The 4- and 5-star hotels are located farthest from the Dubai International Airport. Of course, some of these variations are related to the room price. The average room price for 5-star hotels is about 590 dirhams (about $161), whereas 1-star hotels, on average, charge 166 dirhams (about $45) per night for their basic rooms. The average price for all types of hotels in our sample is 324 dirhams (about $88).

6. Methodology

We consider hotel quality within the framework of hedonic models [68], where certain features of a hotel are evaluated to determine their worth to prospective customers. Firstly, we employ two different hedonic regression models to identify the relationship between the two quality measures, namely the official star rating (SR) and customer review score (CRS), with hotel services, amenities, characteristics, location-specific attributes, and economic geography variables. Secondly, we identify the discrepancies between the two quality measures and relate these discrepancies to hotel services, amenities, characteristics, location-specific attributes, and economic geography variables using the third hedonic regression.

In short, we employ the following three models.

M1: Identifies the relationships between SR and the characteristics and features of hotels.

M2: Identifies the relationships between CRS and the characteristics and features of hotels.

M3: Explores how CRS evaluates the characteristics and features of hotels differently from SR.

We employ linear regressions to estimate our hedonic models. Continuous covariates, such as room size and distances, are used in the log-linear form. Also, we include dummy variables to identify the presence of certain hotel features such as a gym, a spa, a pool, a private beach, or a public beach at the hotel. Likewise, we utilize dummy variables to investigate the impact of a hotel's membership in a chain. We account for the likely competition by counting the number of hotels in the neighborhood. Finally, the average star rating for hotels within 250 m will indicate the competition based on the hotel quality. All regressions use robust standard errors.

Our null hypothesis is that the official rating (SR) is well-designed and effectively encompasses all factors that matter to customers. Therefore, the official rating should perfectly align with the customer review score, except for purely random discrepancies. Conversely, our alternative hypothesis is that there are non-random discrepancies between the two measures of quality that relate to some characteristics and features of hotels.

In summary.

H0

CRS and SR identically evaluate the characteristic and features of the hotels.

H1

CRS evaluates some characteristics and features of hotels differently from SR.

Once H0 has been rejected, we can utilize regression analysis to investigate which features of hotels are overvalued, undervalued, or overlooked within the current official star rating framework. Through this analysis, we can potentially suggest revisions and updates to the rating criteria and standards. We present a detailed discussion of the empirical setup of our model and specifications in the next section.

7. Empirical models and specifications

Firstly, we employ a hedonic regression model to capture the relationship between official rating (star rating) and hotel amenities, location-specific attributes, and economic geography variables. We run several specifications to identify the influential factors in the official rating.

Secondly, we employ a hedonic regression model to estimate the relationship between the customer review score and hotel attributes, amenities, and location-specific characteristics. We compare the first and second sets of regressions to identify how the customer review score values hotel amenities, location-specific attributes, and economic geography variables differently from the official rating.

Thirdly, we use an empirical model for the customer review score that first takes away all variations in CRS that can be explained by the official rating (SR) and then uses hedonic regression to explain the remaining variation with hotel amenities, characteristics, and location-specific attributes. The goal is to determine whether the hotel amenities, characteristics, and location-specific attributes still influence customers’ experience and satisfaction controlling beyond the official rating. Of course, we expect a very strong statistical relationship between customer review scores and official ratings. The second stage of this model allows us to identify the discrepancies between how the official rating and customers value the hotel amenities, characteristics, and attributes. After controlling for the official rating, remaining influences from some hotel amenities, characteristics, and location-specific attributes on customer review scores suggest that the official rating criteria might be inadequate to signal quality (as perceived by customers) to potential customers and may need adjustments and updates.

We start with introducing a general empirical model in Equation (1) that relates the quality measure, namely SR and CRS, to the hotel amenities and location-specific attributes as follows:

| (1) |

where indicates the hotel amenities, services, and attributes (e.g., spa, private beach, and being part of a chain) and contains the location-specific attributes of the hotel (e.g., distance to a metro station and the city center) and economic geography variables (e.g., the number and quality of the hotels in the surrounding area). We use the log value of variables for continuous variables such as room size and distances. We use dummy variables for the hotel amenities, such as access to the gym and beach. For economic geography (clustering) variables, we use the number and quality of hotels within the immediate vicinity.

Equation (2) below represents the full specification for our first hedonic regression model (M1), where we relate the official rating with hotel-specific variables. Of course, we do not expect significant influence for variables beyond the hotel's basic amenities and location-specific attributes because the official rating criteria are related to the hotel attributes and not beyond.

| (2) |

We use a similar specification for our second hedonic regression model (M2) to determine the influential factors in the customer review scores in Equation (3). Using the exact specification as in Equation (2) allows us to compare and contrast the official rating vs. customer reviews.

| (3) |

In the third empirical model, we focus on differences between the official star rating and customer review scores. Our goal is to discover what factors influence the customers' experience (customer review score) beyond what is captured by the official rating. This is the critical model that allows us to identify the discrepancy between the official rating and customer experience, relate it to the basic hotel amenities, characteristics, and attributes, and learn whether other location-specific features significantly influence customer experience and are neglected in the official ratings. This specification might help industry experts and rating agencies adjust their rating criteria for hotels in the region.

This empirical model starts by taking out (or controlling for) all similarities between the CRS and SR. To do so, we regress CRS on SR in Equation (4) to take out all variations in CRS that SR can explain and calculate the residual of this regression as an unexplained part of CRS. This regression, in a sense, captures the differences between two quality measures, given that CRS and SR have different scales, and direct subtraction is not applicable.

| (4) |

After estimating Equation (4), we use the estimated value of and (i.e., and ) to calculate the residual values for the regression (i.e., the unexplained part of CRS), . The regression results in and or . The intercept and coefficient estimates are highly significant at lower than 1% confidence level with standard errors of 0.144 and 0.039, respectively. The explanatory powers (adjusted ) is 0.41. Fig. 1 presents the relationship, the tight confidence intervals for the predicted values, and the (unexplained) deviations from the predicted values.

In the second step, we use these residuals to identify the relationship between the hotel features and unexplained variations in CRS (M3) using the specification in Equation (5).

| (5) |

As mentioned, Table A1 presents the complete list of the variables and their detailed definitions, and Table A2 reports descriptive statistics for these variables. In addition, we investigate the correlation among the covariates to detect potential issues with multicollinearity. The highest correlation among the covariates is 0.705 between “pool” and “gym,” which allays concerns about multicollinearity. The full correlation matrix among the covariates is provided in the Appendix.

Table B1, Table B2, Table B3 present the results for our three models, and the following specifications are shown in a corresponding column in each table. In estimating each model, we start from the basic specification (S1), which is limited to the basic in-hotel amenities, such as a gym, spa, and pool. We add access to private and public beaches in the second specification (S2), whether the hotel is part of a chain in the third specification (S3), the hotel distances to the major access points and landmarks in Dubai in the fourth specification (S4), and the number and the average rating of the hotels in the immediate surrounding area in the fifth specification (S5). These are variables related to hotel clustering (local competition, spillovers, and quality spillover), where “hnumBr0” is the number of hotels within 250 m, and “hratBr0” is the average rating of those hotels. A large number of hotels nearby can indicate negative externalities from crowd, noise, and cleanliness and negatively impact the customers' experience. Alternatively, a large number of hotels nearby can indicate the availability of tourism services (taxis, restaurants, coffee shops, etc.) and attractions (historical sights, etc.) and positively impact the customers’ experience. In addition, being close to high-quality hotels can improve customer experience by having access to high-quality tourism services (e.g., restaurants) provided by other hotels in the close vicinity. We expect that these effects, if any, taper off with distance. We do not expect geographical variables to affect the official star rating substantially because the rating is done based on hotel services, amenities, and attributes, not the characteristics of nearby hotels. However, as long as the hotels with similar quality collocate, we can expect some positive correlation between Star Rating for a particular hotel and the average Star Rating in the surrounding area.

We use a log-linear OLS estimation method in all specifications and calculate the robust (White-corrected) standard errors for coefficients. The use of robust standard errors abates the potential problems with heteroscedasticity and reduces the chances of erroneous inferences regarding the significance of any variables.

8. Results

Table B1, Table B2 present our regression results for three models. We report the results for our five selected specifications in Columns (1) to (5) in all tables. We start from the basic hotel amenities in (1) and expand the variables to include access to the beach in (2), being part of a chain in (3), access to the main locations (downtown, metro station, and airport) in (4), and finally, the number and average quality of hotels in the immediate vicinity of a particular hotel in (5). The first aim is to ensure that our estimations for the basic amenities and characteristics are robust and do not significantly change by introducing other potential explanatory variables. Secondly, we would like to study the effect of location-specific features and economic geography variables (when appropriate) after controlling for the basic amenities.

We begin by presenting the results for the official star rating (M1) in Table B1. As expected, the official star rating is highly related to basic hotel amenities in Column (1), and these basic amenities explain about three-quarters of the variation in the star rating. In Columns (2) and (3), access to a private beach within the hotel and being part of a chain have strong and highly significant effects on the star rating. However, there is no effect from access to a public beach. Other location-specific and economic geography variables also show no (or negligible) effects. These results verify that the official star rating is based on the hotel-provided amenities and characteristics, as official raters record such features and use them in ratings. As reported in Column (3), an increase in the room size by one standard deviation of log value (about 12.4 square meters, from the average of 27.7–40.1) increases the star rating by about 0.35 points, access to gym increases the rating by about 0.66, spa by 0.72, pool by 0.52, private beach by 0.41, and being part of a chain by 0.18 points. In Table B2, we present the results for the customer review score concerning the same set of covariates (M2). As expected, customers also highly value the room size. In addition, access to a gym and being part of a chain are highly valued. However, access to a spa in the hotel has the opposite effect, though it is only significant at 10%. Access to a pool, beach, and other factors are not significant. There is, however, a strong indication that the quality of hotels in the immediate vicinity is valued positively by customers. As reported in Column (3), focusing on the coefficients that are significant at 1%, an increase in the room size by one standard deviation increases customer scores by about 0.231 points, access to a gym by about 1.004 points, and being part of a chain by 0.395 points. In addition, an increase in the average quality of hotels in the immediate vicinity by 1 star rating increases the score by 0.250 points in Column (5).

Regarding the comparison between SR and CRS, the results in Table B1, Table B2 provide stark differences in the pattern of significance. We can observe some noteworthy differences. Spa has a significant negative effect on CRS but a significant positive effect on SR. Pool has no (significant) effect on CRS, but a positive effect on SR, similar to a private beach. Chain has a strong positive effect on CRS but a mostly insignificant effect on SR, and some indications that the distance variables have some effects on CRS than SR. Lastly, as expected, most variations in SR (about 80%) are explained by the hotel services and amenities, but only about half of the variations in CRS are explained. However, directly comparing the effects (coefficients’ magnitude) is not informative because SR and CRS have different scales and baselines. Therefore, we provide a more detailed discussion of the differences and similarities between SR and CRS in the following when we discuss Model 3 results.

Finally, Table B3 reports Model 3 estimation results. These are the main findings of our study, which could call for a revision in the official rating framework and calculations. We present the relationships between unexplained residual leftovers of CRS (henceforth, RES, when taking out all variations that SR can explain) and hotel amenities and characteristics, location-specific features, and economic geography variables. The first interesting result is that controlling for the official rating entirely captures the strong room size influence on CRS; as there is no relationship between the unexplained part of CRS (i.e., RES) and room size after controlling for SR. In other words, SR adequately accounts for the value of room size to customers. Access to a gym and being part of the chain have strong and significant relationships with RES. The spa has a significant and negative relationship with RES. These results suggest that the importance and the weight of access to a gym and being part of a chain may have been undervalued in the official star rating. Conversely, access to a spa in a hotel may have been overvalued.

9. Discussions and comparisons

Hotel official ratings and customer review scores are different ways to evaluate a hotel's quality. Hotel ratings are typically assigned by either official government bodies or independent organizations based on a given set of criteria or standards. On the other hand, hotel customer review scores are based on the ratings or feedback provided by guests who have stayed at the hotel and are usually collected and aggregated by online travel booking platforms and other websites. These quality measures are generally used by travelers to make informed decisions when choosing hotels, and they also have implications for the pricing and marketing strategies of hotels. Our research investigates the factors that influence the official star-rating classification and customer review scores provided by Booking.com for hotels in Dubai. However, the aim is to analyze any inconsistencies that may exist between these two quality indicators. Our research contributes to a broader field of studies on hotel quality measures.

Several academic papers have explored the relationship between these quality measures and hotel characteristics and features. Overall, our results related to quality measures, namely SR and CRS, are consistent with those of [32,51,62,[69], [70], [71], [72], [73]]. Similar to our findings, they conclude that hotel features such as location, cleanliness, and room size are positively related to customers' perception of the quality of a hotel. Likewise, the star rating affects consumers’ booking decisions [74], although this is not necessarily related to the perception of quality.

We also find a robust positive relationship between star ratings and customer reviews, consistent with existing literature [57,75]. Jeong and Jeon [75] also find a strong relationship between customer satisfaction and hotel offerings (location, services, etc.). However, they point out that variation in the star rating does not perfectly match different components of customer reviews. Soifer, Choi, and Lee [76] present more asymmetric behavior in terms of star ratings and customer review scores. Although certain aspects of hotel amenities may appeal to customers of lower-star hotels, they fail to find any such relationship for highest-star hotels. Likewise, it is the case that the origin of the hotel customers and/or their anticipations may play a role in online ratings. Nunkoo et al. [77] also observe variations in how service quality influences customer satisfaction for hotels with different star ratings. Similarly, Bi et al. [78] find asymmetric effects of attributes on customer satisfaction based on the type of hotels, type of travelers, and travelers' regions. Leung et al. [79] also find that Chinese customers tend to post more reviews than other nationalities. Furthermore, customers at relatively higher-scaled hotels, such as those with five stars, tend to post reviews more often [80]. This fact may potentially lead to a discrepancy between star ratings and customer review scores. Among the factors affecting customers’ perspective of a hotel is how long they stay there [81,82], further complicating the comparison between official ratings and customer reviews.

It is worth noting, however, that the specific criteria used to assign hotel ratings can vary between different rating systems, and the relationship between ratings and hotel characteristics may differ depending on the region and country. As indicated above, our study demonstrates that the official ratings in Dubai (UAE) fall short in some criteria compared to customer review scores, failing to signal quality perfectly to potential customers as they perceive quality.

10. Summary and conclusion

Economic theory indicates that reliable ratings of hotels are critical for a well-functioning hotel industry where utility-maximizing customers and profit-maximizing hoteliers benefit from such ratings. Historically, official ratings have fulfilled this vital function and helped the industry to flourish. However, academic and commercial studies emphasize that regular updates and adjustments to such ratings are necessary as customers' preferences change and vary over time and across locations to better signal hotel qualities to potential customers. Such updates and adjustments in official ratings may be implemented quickly and efficiently thanks to advancements in technology, the widespread use of the internet, and real-time direct access to customers’ valuation of quality. While official ratings aspire to be an objective assessment of hotel quality, customer reviews provide a direct but subjective measure of quality. An important question for both hotel customers and hoteliers is how compatible these assessments are because their role is to reduce the asymmetric information problem and not to introduce more confusion. It is not a secret that official ratings may differ across different standards, and they frequently differ from customer scores.

This paper examines the relationship between official ratings and customer review scores for about 250 hotels in Dubai based on the data gathered from Booking.com. We use Star Ratings and customer review scores to explore their relationship and analyze their similarities and differences. We study the effect of location-specific features and other variables after controlling for basic amenities. We find that the official star rating is highly related to basic amenities and attributes offered by hotels, as expected. Room size, access to a gym, spa, pool, private beach, and being part of a chain determines the star rating. Conversely, we find that access to a public beach has no impact on the star rating. Our findings also reveal that other location-specific and economic geography variables show no (or, at best, negligible) effects. These results verify that the official star rating is based on the hotel-provided amenities and characteristics, as official raters record such features and use them in ratings. However, customers may view and weigh these amenities and attributes differently. In addition, the official ratings only reflect features owned by the hotel, and other local amenities do not influence official ratings though it is likely that these facilities (such as a public beach) affect customer review scores. For example, a private pool and a private beach within hotel premises are valued by official raters as opposed to customers who may take these as given for hotels in Dubai. Access to a spa in a hotel is overvalued by the star rating compared to customer review scores. There is, however, a strong indication that the quality of hotels in the immediate surrounding area is valued positively by the customers.

To investigate the differences between the star rating and customer scores, we devise a simple and intuitive model to identify how amenities and attributes influence customer reviews beyond what is captured by the official rating. To this end, we first take out all variations that can be explained by SR, and then we explore the relationships between unexplained residual leftovers of CRS (RES) and hotel amenities and characteristics, location-specific features, and economic geography variables. Our first observation is that the star rating does a good job of completely capturing the impact of room size, leaving no unexplained variation to customer review scores. However, the official rating falls short of fully capturing the effect of several hotel amenities and attributes and location-specific characteristics. Therefore, there is room for improvement. For example, access to a gym has strong and significant positive relationships with RES. This means that customers assign even greater importance to a gym than the star rating does. In other words, the star rating seems to undervalue the desirability of a gym. Another characteristic that the star rating undervalues compared to customer scores is the hotel being part of a chain. This suggests that name and brand recognition are even more important for customers than the star rating recognizes. That may be because being part of a chain guarantees a certain standard with regard to a wide variety of services, amenities, and features. On the other hand, access to a spa has a significant and negative relationship with RES. This result suggests that customers do not value access to a spa as strongly as the official rating does. In other words, the star rating strongly overvalues access to a spa. Overall, these results demonstrate that access to a gym and being part of a chain may have been undervalued in the official star ratings, and access to a spa in a hotel may have been overvalued. In addition, there are some indications that being close to an airport and particularly being close to other high-quality hotels are viewed positively by customers, which is missing from the official rating because the official rating does not include location-specific attributes of the hotel and mainly focuses on amenities and features provided by hotels.

10.1. Practical implication

As an overarching conclusion of our study, we observe that SR and CRS results provide stark differences in the pattern of significance, especially in regards to local features and amenities around hotels, but also the relative importance of some hotel-owned features. Our analysis is based on hotels in a particular location, i.e., Dubai, and discrepancies between the official rating and customer scores may call for updating and revising the official star rating classification for Dubai. Future studies may try to discover the generality of our findings if applied to other locations. Nevertheless, we see a clear call for more location-specific rating frameworks for official ratings. Such adjustments to the official ratings would result in a more informative rating for customers. This allows for a better signal to resolve the aforementioned asymmetric information problem, eliminating the probability of losing potential customers if ratings do not match the customer views of hotel quality. Better alignment between the official ratings and customer review scores may also help the hoteliers by eliminating the competing interests between satisfying the criteria and standards of rating agencies and meeting customers' preferences. As a result, it improves the efficiency and effectiveness of hotels in offering the best experience and value to customers and customers’ appreciation.

Lastly, one limitation of our study is its concentration on a single platform, Booking.com. Although some of the earlier papers [55,57], which studied more than one platform, such as Booking.com and TripAdvisor, find consistency across platforms, this is not a universally shared conclusion. The information provided in one platform may vary significantly in another due to linguistic and semantic reasons [83]. In a broader context, firms have incentives to ‘game’ the system to produce biased reviews [84]. Thus, more comprehensive studies, such as [74], are needed to use and compare more than one platform. Another extension could be the specialized analyses of different segments of hotel customers [85] or locations [86,87].

Author contribution statement

Mohammad Arzaghi; Ismail H Genc; Shaabana Naik: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants at the First International Academic Conference on Economic Policy and Research in the UAE and Beyond in Abu Dhabi in March 2022 and Economics Seminar Series at the American University of Sharjah for their helpful comments and also the Open Access Program at the American University of Sharjah for their support. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the stance or viewpoints of the American University of Sharjah.

Appendix

Table A1.

Main Variables Definitions and Expected Signs.

| Variables | Description | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| SR | Star Rating | Star rating of hotel, ranging from 1 to 5 (collected from Booking.com) |

| CRS | Customer Review Score | Customer review-rating of hotel, ranging from 1 to 10 (Booking.com) |

| lsize | Log of room size | Log of room size, in square meters |

| gym | Gym | Dummy variable for gym or fitness center in hotel (0 if no, 1 if yes) |

| spa | Spa | Dummy variable for spa in hotel (0 if no, 1 if yes) |

| pool | Swimming pool | Dummy variable for swimming pool in hotel (0 if no, 1 if yes) |

| pribeach | Private beach | Dummy variable for a private beach in hotel (0 if no, 1 if yes) |

| pubbeach | Public beach | Dummy variable for a public beach nearby hotel (0 if no, 1 if yes) |

| chain | Hotel Chain | Dummy variable for the hotel being part of a hotel chain (0 if no, 1 if yes) |

| ldistcen | Log distance to center | Distance to Downtown Dubai, in kilometers |

| ldistmet | Log distance to metro | Distance to the nearest subway station, in kilometers |

| ldistair | Log distance to airport | Distance to Dubai International Airport, in kilometers |

| hnumBr0 | Number of hotels in ring 0 | Number of hotels within 250 m |

| hratBr0 | Quality of hotels in ring 0 | Average star rating for hotels within 250 m |

Table A2.

Main Variables Descriptive Statistics.

| Variables | Obs. | mean | sd | min | max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR | 250 | 3.488 | 1.243 | 1 | 5 |

| CRS | 250 | 7.839 | 0.991 | 5.2 | 9.4 |

| lsize | 245 | 3.323 | 0.369 | 2.303 | 4.927 |

| gym | 250 | 0.696 | 0.461 | 0 | 1 |

| spa | 250 | 0.532 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| pool | 250 | 0.656 | 0.476 | 0 | 1 |

| pribeach | 249 | 0.044 | 0.206 | 0 | 1 |

| pubbeach | 250 | 0.148 | 0.356 | 0 | 1 |

| chain | 250 | 0.492 | 0.501 | 0 | 1 |

| ldistcen | 250 | 1.999 | 0.786 | −1.204 | 3.714 |

| ldistmet | 246 | −0.803 | 0.832 | −2.996 | 2.603 |

| ldistair | 249 | 2.199 | 0.762 | 0.336 | 3.936 |

| hnumBr0 | 250 | 7.984 | 7.213 | 0 | 27 |

| hratBr0 | 250 | 3.555 | 0.939 | 1 | 5 |

The definitions of variables are provided in Table A1.

Table A3.

Comparison of Two Quality Indicators

| CRS | SR = 1 | SR = 2 | SR = 3 | SR = 4 | SR = 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 6.41 | 7.20 | 7.61 | 8.13 | 8.57 |

| Median | 6.30 | 7.10 | 7.60 | 8.20 | 8.50 |

| Maximum | 8.90 | 8.40 | 9.10 | 9.20 | 9.40 |

| Minimum | 5.20 | 5.40 | 5.40 | 5.60 | 7.70 |

| SD | 0.85 | 0.85 | 1.02 | 0.64 | 0.39 |

| Observations | 23 | 27 | 70 | 65 | 65 |

Table B1.

Star Rating Regressions

| Variables | (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR | SR | SR | SR | SR | |

| lsize | 1.030*** (0.208) |

0.969*** (0.206) |

0.957*** (0.215) |

0.903*** (0.228) |

0.712*** (0.181) |

| gym | 0.752*** (0.144) |

0.733*** (0.143) |

0.656*** (0.147) |

0.668*** (0.147) |

0.487*** (0.132) |

| spa | 0.700*** (0.107) |

0.689*** (0.105) |

0.723*** (0.108) |

0.721*** (0.110) |

0.569*** (0.0968) |

| pool | 0.527*** (0.146) |

0.516*** (0.146) |

0.523*** (0.146) |

0.518*** (0.148) |

0.366*** (0.126) |

| pribeach | 0.382*** (0.141) |

0.413*** (0.148) |

0.437*** (0.163) |

0.161 (0.154) |

|

| pubbeach | 0.137 (0.120) |

0.0858 (0.123) |

0.0934 (0.133) |

0.0379 (0.119) |

|

| chain | 0.180** (0.0833) |

0.162* (0.0882) |

0.0415 (0.0825) |

||

| ldistcen | −0.0555 (0.0492) |

0.0188 (0.0427) |

|||

| ldistmet | 0.0203 (0.0503) |

0.0260 (0.0488) |

|||

| ldistair | −0.0230 (0.0508) |

−0.0713* (0.0417) |

|||

| hnumBr0 | −0.00154 (0.00689) |

||||

| hratBr0 | 0.437*** (0.0713) |

||||

| Constant | −1.159* (0.598) |

−0.972 (0.596) |

−0.982 (0.622) |

−0.624 (0.742) |

−1.186** (0.557) |

| Observations | 245 | 244 | 244 | 239 | 239 |

| R-squared | 0.746 | 0.753 | 0.757 | 0.749 | 0.797 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table B2.

Customer Review Score Regressions

| Variables | (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRS | CRS | CRS | CRS | CRS | |

| lsize | 0.688*** (0.207) |

0.653*** (0.206) |

0.625*** (0.214) |

0.571*** (0.218) |

0.462** (0.198) |

| gym | 1.192*** (0.170) |

1.173*** (0.171) |

1.004*** (0.180) |

0.957*** (0.184) |

0.781*** (0.182) |

| spa | −0.267** (0.114) |

−0.276** (0.116) |

−0.203* (0.111) |

−0.182* (0.104) |

−0.274*** (0.103) |

| pool | 0.154 (0.167) |

0.150 (0.167) |

0.166 (0.161) |

0.144 (0.157) |

0.0737 (0.152) |

| pribeach | 0.126 (0.153) |

0.193 (0.163) |

0.209 (0.185) |

0.0218 (0.186) |

|

| pubbeach | 0.141 (0.112) |

0.0295 (0.106) |

−0.0259 (0.108) |

−0.0672 (0.107) |

|

| chain | 0.395*** (0.1000) |

0.360*** (0.0993) |

0.271*** (0.0902) |

||

| ldistcen | −0.0497 (0.0464) |

0.00773 (0.0463) |

|||

| ldistmet | 0.1000* (0.0587) |

0.0871 (0.0597) |

|||

| ldistair | 0.124** (0.0603) |

0.0768 (0.0558) |

|||

| hnumBr0 | −0.0119 (0.00763) |

||||

| hratBr0 | 0.250*** (0.0854) |

||||

| Constant | 4.768*** (0.594) |

4.878*** (0.594) |

4.857*** (0.613) |

5.000*** (0.690) |

4.822*** (0.605) |

| Observations | 245 | 244 | 244 | 239 | 239 |

| R-squared | 0.492 | 0.495 | 0.528 | 0.530 | 0.563 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table B3.

Customer Review vs. Official Rating

| Variables | (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RES | RES | RES | RES | RES | |

| lsize | 0.160 (0.160) |

0.155 (0.163) |

0.134 (0.161) |

0.108 (0.163) |

0.0963 (0.164) |

| gym | 0.806*** (0.156) |

0.797*** (0.158) |

0.667*** (0.162) |

0.615*** (0.169) |

0.532*** (0.178) |

| spa | −0.626*** (0.110) |

−0.630*** (0.112) |

−0.574*** (0.108) |

−0.552*** (0.104) |

−0.566*** (0.109) |

| pool | −0.116 (0.156) |

−0.114 (0.157) |

−0.102 (0.152) |

−0.122 (0.154) |

−0.114 (0.157) |

| pribeach | −0.0706 (0.168) |

−0.0187 (0.172) |

−0.0152 (0.198) |

−0.0607 (0.200) |

|

| pubbeach | 0.0713 (0.109) |

−0.0145 (0.105) |

−0.0739 (0.112) |

−0.0867 (0.112) |

|

| chain | 0.303*** (0.0946) |

0.277*** (0.0924) |

0.249*** (0.0901) |

||

| ldistcen | −0.0212 (0.0461) |

−0.00191 (0.0494) |

|||

| ldistmet | 0.0896* (0.0536) |

0.0738 (0.0537) |

|||

| ldistair | 0.136** (0.0619) |

0.113* (0.0626) |

|||

| hnumBr0 | −0.0112 (0.00751) |

||||

| hratBr0 | 0.0260 (0.0896) |

||||

| Constant | −0.687 (0.470) |

−0.674 (0.477) |

−0.689 (0.467) |

−0.730 (0.535) |

−0.620 (0.555) |

| Observations | 245 | 244 | 244 | 239 | 239 |

| R-squared | 0.213 | 0.214 | 0.246 | 0.272 | 0.280 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

References

- 1.Nelson P. Information and consumer behavior. J. Polit. Econ. 1970;78(2):311–329. Mar. - Apr. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akerlof G.A. The market for ‘Lemons’: quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1970;84(3):488–500. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis R.C., Chambers R.E. Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1989. Marketing Leadership in Hospitality. Foundations and Practices. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolau J.L., Sellers R. The quality of quality awards: diminishing information asymmetries in a hotel chain. J. Bus. Res. 2010;63(8):832–839. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manesa E., Tchetchika A. The role of electronic word of mouth in reducing information asymmetry: an empirical investigation of online hotel booking. J. Bus. Res. 2018:185–196. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callan R.J. Small country hotels and hotel award schemes as a measurement of service quality. Serv. Ind. J. 1989;9(2):223–246. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qing L.Z., Liu J.C. Assessment of the hotel rating system in China. Tourism Manag. 1993;14(6):440–452. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oskam J., Boswijk A. Airbnb: the future of networked hospitality businesses. J. Tourism Futur. 2016;2(1):22–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohlmann M. Digital trust and peer-to-peer collaborative consumption platforms: a mediation analysis. 2016. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2813367 SSRN Working Paper 2813367, available at: (accessed 11/23/2021)

- 10.Yang Y., Park S., Hu X. Electronic word of mouth and hotel performance: a meta-analysis. Tourism Manag. 2018;67:248–260. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nalley M.E., Park J., Bufquin D. An investigation of AAA diamond rating changes on hotel performance. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2019;77:365–374. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Y., Zhang Z., Nicolau J., Liu X. How do hotel managers react to rating fluctuation? Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2020;89(August):102563. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gefen D., Straub D.-W. Consumer trust in B2C e-Commerce and the importance of social presence: experiments in e-Products and e-Services. Omega. 2004;32(6):407–424. doi: 10.1016/j.omega.2004.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pindyck R.S., Rubinfeld D.L. In: The Pearson Series in Economics. Global, editor. Pearson; 2018. Microeconomics. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amblee N., Bui T. Harnessing the influence of social proof in online shopping: the effect of electronic word of mouth on sales of digital microproducts. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2014;16(2):91–114. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filieri R., McLeay F. E-WOM and accommodation: an analysis of the factors that influence travelers' adoption of information from online reviews. J. Trav. Res. 2014;53(1):44–57. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erkan I., Evans C. Social media or shopping websites? The influence of eWOM on consumers' online purchase intentions. J. Market. Commun. 2016;24(6):617–632. https://doi-org.ep.bib.mdh.se/10.1080/13527266.2016.1184706 [Google Scholar]

- 18.So K., King C., Sparks B., Wang Y. The role of customer engagement in building consumer loyalty to tourism brands. J. Trav. Res. 2014;55(1):64–78. doi: 10.1177/0047287514541008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo J., Wang X., Wang Y. Positive emotion bias: role of emotional content from online customer reviews in purchase decisions. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2020;52(92):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li C., Cui G., Peng L. The signaling effect of management response in engaging customers: a study of the hotel industry. Tourism Manag. 2017;62:42–53. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, N. S. nd. Consumer Research Emphasizes Importance of Online Feedback Management. TrustYou, 9. Available at https://resources.trustyou.com/c/wp-online-feedback?x=cjJkLD&cn=wp-online-feedback&ct=White%20Paper. Accessed on 8/13/2021..

- 22.Arzaghi M., Genc I., Naik S. Clustering and hotel room prices in Dubai. Tourism Econ. 2022:1–21. doi: 10.1177/13548166211040931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thaler R.H., Sunstein C.R. Penguin Books; New York: USA: 2009. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness Paperback. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghimire B., Shanaev S., Lin Z. Effects of official versus online review ratings. Ann. Tourism Res. 2021:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clerides S., Nearchou P., Pashardes P. University of Cyprus, (February); 2004. Intermediaries as Quality Assessors in Markets with Asymmetric Information: Evidence from UK Package Tourism. Working Paper. (Accessed on 11/24/2021) [Google Scholar]

- 26.US-UAE Business Council (The) 2019. Hospitality, Tourism, and Leisure in the UAE: Overview and Opportunities for Business, (January), Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Economic Development. Government of Dubai Dubai Economic Report. 2019;2019 https://dubaided.gov.ae/StudiesAndResearchDocument/DER2019_EN_Report_f4.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lohmann G., Albers S., Koch B., Pavlovich K. From hub to tourist destination–An explorative study of Singapore and Dubai's aviation-based transformation. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2009;15(5):205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colliers International 2019. Arabian travel market | Aviation trends in the UAE. February 2019. https://www2.colliers.com/en-AE/Research/Dubai/ATM-Aviation-trends-in-the-UAE

- 30.International Air Transport Association The importance of air transport to the United Arab Emirates. IATA. 2019. https://www.iata.org/contentassets/f915debf638d4799876e6687a2283b5a/iata_united-arab_emirates_report.pdf

- 31.Fahy M. Dubai tourism numbers up 5.1 percent in 2019. The National, (January 21) 2020. https://www.thenational.ae/business/travel-and-tourism/dubai-tourism-numbers-up-5-1-per-cent-in-2019-1.967509 Accessed on September 7, 2020.

- 32.Xie K.L., Zhang Z., Zhang Z. The business value of online consumer reviews and management response to hotel performance. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2014;43:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bickart B., Schindler R.M. Internet forums as influential sources of consumer information. J. Interact. Market. 2001;15(3):31–40. doi: 10.1002/dir.1014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernández-Barcala M., González-Díaz M., Prieto-Rodríguez J. Hotel quality appraisal on the internet: a market for lemons? Tourism Econ. 2010;16(2):345–360. doi: 10.5367/000000010791305635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoon Y., Uysal M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: a structural model. Tourism Manag. 2005;26(1):45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schiffman L.G., Kanuk L.L. seventh ed. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2000. Consumer Behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun T., Youn S., Wu G., Kuntaraporn M. Online word-of-mouth: an exploration of its antecedents and consequences. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2006;11:1104–1127. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Litvin S.W., Goldsmith R.E., Pan B. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tourism Manag. 2008;29(3):458–468. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cantallops A.S., Salvi F. New consumer behavior: a review of research on eWOM and hotels. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2014;36:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bansal H.S., Voyer P.A. Word-of-mouth processes within a service purchase decision context. J. Serv. Res. 2012;3(2):166–177. doi: 10.1177/109467050032005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sparks B., Perkins H., Buckley R. Online travel reviews as persuasive communication: the effects of content type, source, and certification logos on consumer behavior. Tourism Manag. 2013;39:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berhanu K., Raj S. The trustworthiness of travel and tourism information sources of social media: perspectives of international tourists visiting Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2020;6 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vermeulen I.E., Seegers D. Tried and tested: the impact of online hotel reviews on consumer consideration. Tourism Manag. 2009;30(1):123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2008.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casado-Díaz A.B., Pérez-Naranjo L.M., Sellers-Rubio R. Aggregate consumer ratings and booking intention: the role of brand image. Service Business. 2017;11(3):543–562. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blal I., Sturman M.C. The differential effects of the quality and quantity of online reviews on hotel room sales, Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014;55:365–375. doi: 10.1177/1938965514533419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoo K.H., Gretzel U. Influence of personality on travel-related consumer-generated media creation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011;27(2):609–621. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andersson D.E., Jia M. Official and subjective hotel attributes compared: online hotel rates in Shanghai. J. China Tourism Res. 2019;15(1):50–65. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernández M.C.L., Bedia A.M.S. Is the hotel classification system a good indicator of hotel quality?: an application in Spain. Tourism Manag. 2004;25(6):771–775. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Núñez-Serrano J.A., Turrión J., Velázquez F.J. Are stars a good indicator of hotel quality? Asymmetric information and regulatory heterogeneity in Spain. Tourism Manag. 2014;42:77–87. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ladhari R., Michaud M. eWOM effects on hotel booking intentions, attitudes, trust, and website perceptions. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2015;46:36–45. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ogut H., Tas B.K.O. The influence of internet customer reviews on the online sales and prices in hotel industry. Serv. Ind. J. 2012;32(2):197–214. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phillips P., Barnes S., Zigan K., Schegg R. Understanding the impact of online reviews on hotel performance: an empirical analysis. J. Trav. Res. 2016;56(2):235–249. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang Y., Mueller N.J., Croes R.R. Market accessibility and hotel prices in the Caribbean: the moderating effect of quality-signaling factors. Tourism Manag. 2016;56:40–51. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson C.K. The impact of social media on lodging performance. Cornell Hospital. Report. 2012;12(15):4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Agušaj B., Bazdan V., Lujak D. The relationship between online rating, hotel star category and room pricing power. Ekonomska Misao i Praksa. 2017:189–204. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castro C., Ferreira F.A. Online hotel ratings and its influence on hotel room rates: the case of Lisbon, Portugal. Touris. Manag. Stud. 2018;14:63–72. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martin-Fuentes E. Are guests of the same opinion as the hotel star-rate classification system? J. Hospit. Tourism Manag. 2016;29:126–134. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Department of Culture and Tourism Abu Dhabi hotel classification manual. Available at. 2018. https://tcaabudhabi.ae/DataFolder/Files/Hotel-Classification-System-Manual.pdf (accessed 13 June 2020)

- 59.Ghobadian A., Speller S., Jones M. Service quality: concepts and models. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 1994;11(9):43–66. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akbaba A. Measuring service quality in the hotel industry: a study in a business hotel in Turkey. Hosp. Manag. 2006;25:170–192. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dolnicar S., Otter T. Which hotel attributes Matter? A review of previous and a framework for future research. 2003. https://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers/268 (Accessed on December 03, 2022)

- 62.Zhang Z., Ye Q., Law R. Determinants of hotel room price: an exploration of travelers' hierarchy of accommodation needs. Int. J. Contemp. Hospit. Manag. 2011;23(7):972–981. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Balaguer J., Pernías J.C. Relationship between spatial agglomeration and hotel prices. Evidence from business and tourism consumers. Tourism Manag. 2013;36:391–400. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sánchez-Pérez M., Illescas-Manzano M.D., Martínez-Puertas S. You’re the only one, or simply the best. Hotels differentiation, competition, agglomeration, and pricing. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2020;85(February):102362. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arzaghi M., Henderson J.V. Networking off madison avenue. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2008;75(4):1011–1038. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kerr W.R., Kominers S.D. Agglomerative forces and cluster shapes. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2015;97(4):877–899. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duranton G., Kerr W.R. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2015. The Logic of Agglomeration (No. W21452) [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosen S. Hedonic prices and implicit markets: product differentiation in pure competition. J. Polit. Econ. 1974;82(1):34–55. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu Y. Word-of-mouth for movies: its dynamics and impact on box office receipts. J. Market. 2006;70(3):74–89. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dellarocas C., Zhang X., Awad N.F. Exploring the value of online product ratings in revenue forecasting: the case of motion pictures. J. Interact. Market. 2007;21(4):23–45. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martin J., Barron G., Norton M.I. 2007. Choosing to Be Uncertain: Preferences for High Variance Experiences. in: London Business School Trans-Atlantic Doctoral Conference. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duan W.J., Gu B., Whinston A.B. Do online reviews matter? An empirical investigation of panel data. Decis. Support Syst. 2008;45(4):1007–1016. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ye Q., Law R., Gu B. The impact of online user reviews on hotel room sales. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2009;28:180–182. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ye Q., Law R., Gu B., Chen W. The influence of user-generated content on traveler behavior: an empirical investigation on the effects of e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011;27:634–639. [Google Scholar]