Abstract

This study examines the impact of human capital on economic growth in 48 African countries from 2000 to 2019. The methodological approach involves the system GMM technique to address the problem of potential sources of endogeneity. The findings reveal that economic growth in Africa is positively influenced by human capital development. The findings also indicate that both the male and the female genders for human capital development are important for the economic growth of African countries. Similarly, internet penetration and foreign direct investments interact with human capital to produce positive net effects on economic growth. The study recommends policymakers attribute more resources to the education and health sectors to enhance human capital development as a prerequisite to ensure a stable economic growth.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43546-023-00494-5.

Keywords: Africa, Economic growth, Human capital, GMM

Introduction

Economic growth is one of the predominant research areas in economics with many theories developed to establish a better comprehension of economic complexity and development (Adeleye et al. 2022). Following the World Bank’s (2020a, b) report, there are substantial setbacks on Sustainable Development Goal 8, aimed at promoting sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all in recent years in the African economies. In addition, the International Labour Organization (ILO) (2020) confirms that the socioeconomic outlook of the African economy does not appear to be encouraging, with about 25–35 million people in extreme poverty bracket in 2021, down from 110 to 125 in 2020. However, sustained and inclusive growth can be attained through human capital accumulation which facilitates progress, create decent jobs for all, and improve living standards (World Bank 2020a, b). Following the endogenous growth model of Lucas (1988), economic development is enhanced by human capital through its interactive effects with Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), otherwise referred to as technological progress (Shobande and Asongu 2022). Investment in the educational sectors is expected to enhance the level of economic development in Africa (Tchamyou et al. 2019; Nchofoung and Asongu 2022a, b). Diebolt and Hippe (2022) highlighted that human capital through technological progress enhances the level of economic development. Labour productivity is facilitated by technological progress whose impact on economic development depends on access to educational facilities. Also, human capital has long been viewed as an important determinant of economic development and technological growth (Intisar et al. 2020).

The Newly Industrialized Economies around the globe with models based on the knowledge economy whose levels of developments have been far higher than those of most African countries in the last two decades could be an inspiration to the African economies (Ofori and Asongu 2021) and to a certain extend to motivate industries found in rural areas to apply the human resource management model to boost their performance (Margarian et al. 2022; Wirajing and Nchofoung 2023). Among these Newly Industrialized Economies whose growth was similar to those of African economies in the late twentieth century were Asian countries, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, China, and Malaysia (Tchamyou et al. 2019). These Newly Industrialized Economies have adapted well to the knowledge economy and apply human capital for the enhancement of the levels of their economic development, making them to move ahead of Africa in economic development, whose exportation is principally based on commodities, whose prices have frequently be subjected to negative exogenous shocks (Nchofoung and Asongu 2022a).

Ngouhouo et al. (2021) documented that countries with higher levels of human capital development are more resilient to economic shocks. The levels of the welfare of Africans rose in the 1970s after the independence of most of the territories from their colonial masters. The World Development Report (2016) in its digital dividends documented that ICT development is sufficient but not enough to ensure sustainable development without an enhanced human capital development. The fourth SDG on ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting learning opportunities for all encourages human capital accumulation as a process through which sustainability can be attained especially in the African continent where the level of development is comparatively low as compared to the western countries (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 2019).

The World Bank (2022) statistics show that the GDP growth rate of sub-Saharan Africa decreased from 3.41 in 2000 to 2.844 in 2015. The region's GDP growth has decreased considerably between 2019, from 2.577 to – 2.012, and 2020. African countries experienced low economic growth and made little progress in raising their investments in education and the health sector so as to enhance human capital. According to this same statistics, GDP growth of northern African countries decreased from 6.789 to – 3.98 in 2020. The negative GDP growth between 2019 and 2020 was caused by the health crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic. Countries with better access to education, enhanced human capital development, and information and technology infrastructures have higher levels of growth which contributes to its sustainability (Donou-Adonsou 2019). Bloom et al. (2020) posited that low GDP growth registered between 1975 and 1990 and in the early years of the twenty-first century was due to low rates of enrollment for higher education in Africa. The levels of enrollment in higher education in Africa are by far the lowest in the world. Whereas, education is widely considered as a leading instrument for promoting socio-economic development.

Extant literature has it that, human capital affects economic growth through its ability to enhance structural transformation and globalization. Globalization is facilitated by increasing technological innovation and human capital development which enhance economic development both at the micro and macro levels (Asongu and Odhiambo 2020). According to this author, several initiatives have to be taken to improve human capital in Africa among which are: to improve the quality of education through the construction of learning infrastructures and learning materials to support effective education, ensure quality teaching and learning through teacher development. The World Bank launched a Plan in response to Africa’s low scores on the human capital development which measures how well African countries will invest in the next generation of workers. The report revealed that the low scales of human capital is due to high mortality and stunting rates cooperated with inadequate learning outcomes that have highly affected the level of productivity outcomes in Africa (World Bank 2020b). According to this report, children in this region could expect to achieve only 40% of their future productivity if they enjoy complete education and full health which is very low as compared to other regions, such as in Europe and America, where the average human scale index is 0.8. Africa still registers 16.457861 million dropped out from primary schools, and the child infant mortality rate was still high (50) in 2020 which are disturbing signs in the pursuit of sustainable development in any economy (World Bank 2021). From the highlighted problems, the present study draws its inspirations from this growing concerns in the human capital sector to revisit the human capital–economic development nexus with the identified transmission channels through which economic development can be enhanced.

The study contributes to the extant literature in the following ways. First, the study assesses the effect of human capital on economic growth by considering the human capital of both the male and the female gender which has not been exploited in the existing literature. The closest studies to this effect are those of Ogundari and Awokuse (2018), Adeleye et al. (2022), Wang et al. (2022) and Colantonio et al. (2010). However, the aforementioned studies approached human capital by education, health and life expectancy at birth without considering the differences between the female and male human capital to measure if they both contribute to the enhancement of economic development, a gap filled by the present study. Second, the study identifies transmission mechanisms through which the effect of human capital on economic growth is modulated, by considering the channels of ICT, foreign direct investments and trade openness. This is a major contribution as it demonstrates how human capital can be enhanced through ICT, trade openness and FDI to improve the economic condition of the African economies which is absent in extant literature on human capital and economic development (Asongu and Odhiambo 2020; Intisar et al. 2020). This dimension of transmission mechanisms employed in the study is aimed to diversify economic policy settings and processes by providing the different ways and policy decisions to attain a sustainable level of economic development. These channels are also important for developing the human capital and the knowledge economy sectors which are prerequisites for a long-run sustainable economic development.

The paper is further organized in 4 sections. Sect. "Literature review" presents a brief theoretical literature and empirical findings on the effect of human capital on economic growth which immediately follows the introductory section. In Sect. "Data and methodology", we present the data and the research methodology with its justifications. Sect. "Results and discussion" presents the results with its corresponding discussions while Sect. "Conclusion and Policy recommendations" concludes with the policy recommendations and further research perspectives.

Literature review

Existing literature on how human capital influences the level of economic growth is varied and large with many time series, panel, and cross-sectional analyses. The literature on human capital and growth has been popularized and well-documented in the early works of Romer (1986), Lucas (1988) Barro (1991), who emphasized the role of human capital in enhancing economic growth in an economy. According to Becker (1975), education facilitates the creation of new ideas which is a major source of human capital reflected in the accumulation of scientific knowledge. Investments in the health and education sectors contribute to the enhancement of human capital which tends to generate growth in physical capital and thus economic growth (Romer 1990). The levels of productivity and efficiency are well enhanced by the persistent accumulation of knowledge by individuals. Lucas (1988) also posited that this accumulation of knowledge is through the process of learning by doing which enhances labor productivity, thus contributing to economic development. Subsequently, a large strand of empirical studies emerged in support of the positive contributions of human capital to economic growth. Among the works that emerged were those of Romer (1990), Barro (1991) Barro et al. (1992) Mankiw et al. (1992), Lau et al. (1993). According to Lucas (1988), the level of economic development is enhanced by human capital development through improved investment in education and health. Human capital development, therefore, serves as an engine of economic development. Solow (1956) documented in his exogenous growth theory that there exist two factors of production which are capital and labor. According to the Solow (1956) model, human capital is considered a separate factor of production like capital and labor but not an important component of the labor-induced growth process (Erich 1996).

Also, in the labor-augmented production function of the Cobb–Douglas form, Mankiw et al. (1992) demonstrate an augmented Solow model by introducing human capital development as a factor of production which accounts for technical progress (Barro and Sala-i-Martin 1992). The introduction of human capital as a determining factor of growth shows how economic development can be enhanced in Africa by investing more in education and the health sectors. The Solow model receives a series of criticisms on why technical progress is considered an external factor and also why his first model did not consider human capital as a factor of production. According to Lucas (1988), the level of economic development is enhanced by human capital development through improved investment in education and health. Human capital development, therefore, serves as an engine of economic development. De-Long and Summers (1991) and De long et al. (1992) documented the importance of human capital development as an engine of growth. According to these authors, health and education are important factors that stimulate economic growth. The authors also documented that investment, trade and technology play a positive role in a country's economic development process. Grossman and Helpman (1991), and Lawrence and Weinstein (1999) identified technology transferred from developed economies to developing countries in the form of imports to ameliorate the level of economic development.

Empirical studies conducted on the effect of human capital on economic growth have adopted different measures of human capital. Some of these studies employed education while others employed health as measures of human capital and others employed indexes that combine both education and health in their computation. Among the studies that employed both the dimension of health and education are Intisar et al. (2020) who conducted a study in two selected geographically distributed regions which encompass 19 Asian countries to assess the impact of human capital on economic growth which covers the period 1985–2017. Their findings reveal that trade openness and human capital have a significant and statistically positive relationship with economic growth in Southern Asia. The authors reveal that human capital and economic growth have a unidirectional causality in both regions. Soukiazis and Antunes (2012) conducted a study using a panel data model of European Union members over the period 1980–2004 estimated using different proxies of human capital and foreign trade as determining factors of economic growth. The findings from the regression analysis indicate that the inclusion of human capital, trade openness and interaction terms between them have significant positive effects on growth. Kowal and Paliwoda-Pękosz (2017) found that human capital in emerging economies enhances the level of economic growth. The authors further argue that ICT for Global Competitiveness also has a positive significant impact on the level of economic development in emerging economies. Similarly, Ogundari and Awokuse (2018) determine the effect of human capital on economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa covering 35 countries from 1980 to 2008. The authors employ health and education as indicators of human capital. The empirical results show that the two measures of human capital have positive effects on the level of economic development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Adeleye et al. (2022) conducted a study on human capital and economic growth dynamics in the Middle East and North African Countries. The study adopted two indicators of human capital which are education enrollment and life expectancy at birth on an unbalanced panel data of 19 MENA countries which cover the period 1980–2020. The findings reveal that both human capital indicators influence economic growth positively. Further examination of the findings reveals that primary education exerts the significance level of other education indicators while life expectancy appeared to be the most potent human capital indicator. Saldanha et al. (2022) found that human capital and market intensity positively moderate the influence of growth using cross-sectional primary data from a sample of 186 U.S. credit unions.

Another strand of literature emerged employing health as an indicator of human capital to test its impact on economic growth. Aghion et al. (2010) conducted a study in a cross-country analysis over the period 1960–2000 using health as an indicator of human capital and found out that higher levels of life expectancy have a significantly positive impact on GDP per capita growth which is an indicator of economic development. On their part, Wang et al. (2022) conducted a study to investigate the effect of life expectancy on economic growth in the six WHO regions, in 134 countries. The results illustrated the heterogeneity of spatiotemporal trends in life expectancy. The results indicate that Africa and South-East Asia show much lower life expectancy levels than the Americas, European, and Western Pacific which exhibit relatively higher life expectancy levels. The findings further reveal that countries with low overall levels of life expectancy show a relatively stronger upward trend in GDP per capita than the overall upward trend and vice versa. The findings of Wang et al. (2022) show that growth increases with decreasing levels of life expectancy which contradicts the findings of Aghion et al. (2010).

Some empirical works focused on education as an indicator of human capital in assessing the human capital–growth nexus. Some of these studies include the works of Chekina and Vorhach (2020) who conducted a study on the effect of education on the level of economic development over the periods 2015–2019 in the Eurozone. The results of the impact of higher education financing on GDP growth showed that there is an increasing trend with the higher expenditure on education corresponding to higher population qualification and a larger size of GDP. The results further reveal that there is no strong dependence of the population's skills upgrading on GDP growth. Similarly, Hanushek and Woessmann (2020) demonstrated in their study conducted on knowledge and economic growth that human capital development positively affects economic development. Chowdhury (2022) supported in his study conducted using quarterly data from 1974 to 2019 to analyze the effect of internationalization of education on the level of economic development in Australia that there is a long-run positive relationship and a short-run dynamic effect of education on the economic development of Australia. The finding of Chowdhury (2022) is similar to those of Prasetyo and Kistanti (2020) who also found out that education contributes to economic development. Considering the well-documented literature on how human capital is essential to economic growth, we set the following hypothesis:

H1

Human capital contributes in enhancing the level of economic growth in Africa.

In addition, the contemporary growth literature has acknowledged the importance of ICT diffusion, trade openness and FDI in speeding up the rate of economic development (Demissie 2015; Mohanty and Sethi 2021). In both the growth models of Solow and Lucas, technology is acknowledged as a facilitator of growth boosted by ICT diffusion and human capital development enhanced through trade openness and FDI (Su and Liu 2016). Mohanty and Sethi (2019) found out that outward FDI greatly contributes to the enhancement of human capital in BRICS countries in both short and long-run dynamics. In their attempt of investigating the human capital development effects on economic growth, they also found out that human capital boosts the quality of skilled labor through education which raises the level of productivity, and thus increases outward investments for economic development. This is following the findings of Su and Liu (2016) who demonstrated how economic growth is boosted by human capital endowment greatly intensified by FDI and ICT diffusion. This strand of literature supporting the modulating effects of FDI, trade openness and internet penetration on economic growth is well justifiable, especially in developing countries as technology and knowledge transfers are considered among the main factors that contribute to economic development facilitated by trade openness and FDI. This is so because FDI and trade openness are important aspects of transferring new ideas of development, the expansion of the knowledge-based economy and ICT diffusion which has been a typical case in newly industrialized economies (Das and Sethi 2020; Rehman 2016; Mohanty and Sethi 2021). After a careful examination of the literature, we consider FDI, trade openness and internet penetration as possible channels through which the effect of human capital on economic growth is modulated, and thus set the following hypotheses:

H2

FDI plays a positive role in moderating the effect of human capital on economic growth.

H3

The interaction between Trade openness and human capital produce a positive significant effect on economic growth.

H4

Internet penetration plays a positive role in modulating the effect of human capital on economic growth.

The existing literature on the empirical studies conducted in Africa such as in the works of Ogundari and Awokuse (2018), Adeleye et al. (2022), Wang et al. (2022) and Kowal and Paliwoda-Pękosz (2017) who demonstrated in their respective studies that human capital enhances the level of economic growth but have neglected the transmission channels through which human capital can influence the level of economic growth. The study has addressed this gap by identifying three transmission channels of ICT, trade openness and foreign direct investments. Also as a gap not addressed by studies conducted in investigating the human capital–development nexus in Africa, we investigated the effect of both the male and the female human capital on economic development. Some of these studies such as that of Wang et al. (2022) limited the measure of human capital to health performance while neglecting educational development. Our study considered a measure that encompasses both educational development and health performance to proxy human capital development. The present study added some significance by determining the net effects and the thresholds of the identified transmission channels to produce good modulating policy recommendation.

Data and methodology

Data

The study employs secondary panel data on 48 1African countries that spans from 2000 to 2019. The data on economic growth indicator, the rate of inflation, trade openness, gross savings and internet penetration are obtained from the World Bank Development Indicators (2022). The data on the human capital index is obtained from the Penn World Table version 10.0. Another dataset employed in the study for robustness checks includes the human capital index for the female and the male population obtained from the World Bank Development Indicators. The datasets employed for robustness checks are for the years 2017, 2019, and 2020. The choice of the sample size and the duration of the study are constrained by limited data on human capital. The Human capital index for the male and the female scale is available only for the periods 2017, 2019, and 2020. The choice of the study countries and period are based basically on the availability of data on the variables under investigation.

Dependent variable

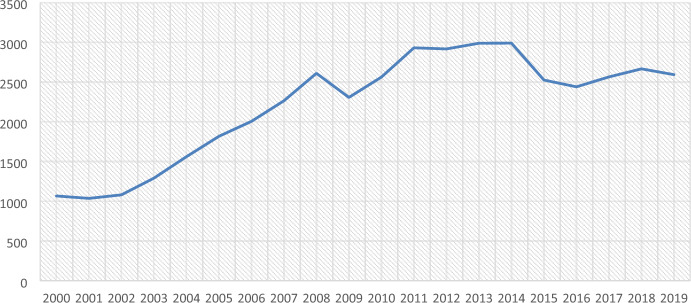

The dependent variable of the study is economic growth. Economic growth is proxied by GDP per capita. GDP per capita is the sum of the country’s money value of goods and services divided by the midyear population. It is also computed as the sum of value added by all resident producers in the country plus taxes and minus subsidies that are not part of the products’ value added. The adoption of GDP per capita as an indicator of economic growth is inspired by the works of Asongu and Odhiambo (2020), Intisar et al. (2020) and Prasetyo and Kistanti (2020). Figure 1 shows the trends in GDP per capita from 1980 to 2019.

Fig. 1.

Trends in economic growth in Africa

Figure 1 shows an increasing trend in gross domestic product per capita (GDP per capita). The average GDP per capita increases from 1066.711 in 2000 to 2562.375 in 2010. The growth between 2010 and 2014 very slow as compared to the growth between 2000 and 2010. Figure 1 shows that the highest GDP per capita in Africa between 2000 and 2019 was registered in 2014. Contrarily, the rate of GDP per capita decreases between 2014 and 2016 before rising, this can be attributed to the commodity price shocks that these countries suffer within these periods. The decreasing trend recorded in 2019 is due to the Covid-19 pandemic that brought the world economy into a recession.

Independent variable of interest

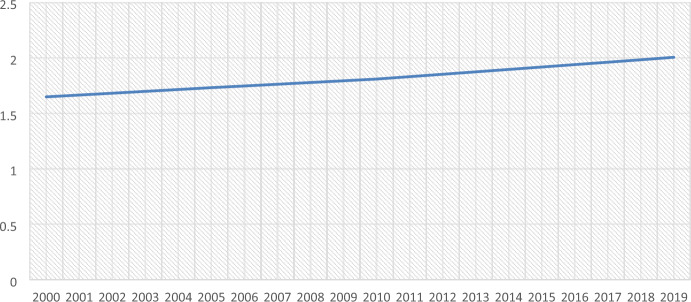

The variable of interest is human capital. It is measured by investments in the education and health sectors and how they contribute to productivity and efficiency of work force (World Bank 2022). Human capital index is computed in units of productivity relative to education and full health benchmarks. Three measures of human capital are employed in the study: human capital index as a gender parity index, human capital index for the male scale and human capital index for the female gender. The employment of human capital as a determinant of economic development is inspired by the works of Fatima et al. (2020) and Adeleye et al. (2022), Pelinescu (2015) and Ahmed et al. (2020). Figure 2 presents the trends in human capital development from 1980 to 2019.

Fig. 2.

Trends in human capital development in Africa measured by a gender parity index

Figure 2 shows the evolution of human capital development in Africa from 2000 to 2019. The figure indicates an increasing trend in human capital. Increasing trends in human capital signifies that much has been invested in the education and the health sectors in African countries between 2000 and 2019. Investments in the health and the education sector with their benchmark productivity from workforce increased considerably from 1.648 in 2000 to 1.808 in 2010 and to 2.1 in 2019. This increase in human capital development promotes sustainable development in Africa.

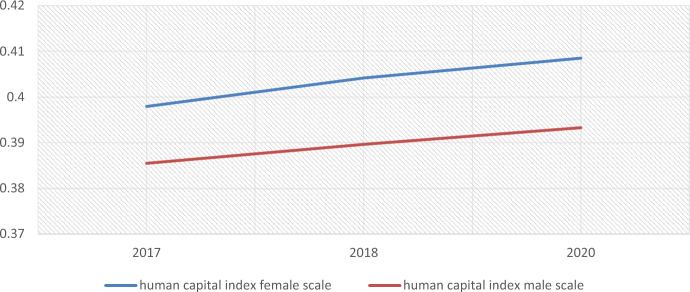

Figure 3 presents the evolution of human capital index of both the male and the female scale for the years 2017, 2019 and 2020. The figure demonstrates increasing trends in human capital development of the male population from 0.3854 in 2017 to 0.3932 in 2020. Also, the female human capital index increases from 0.397 in 2017 to 0.4085 in 2020. Growth In information and communication technology is what facilitated growth in human capital which still has high rates during the health crises periods (Bakibinga-Gaswaga et al. 2020).

Fig. 3.

Trends in human capital development in Africa (Male and Female scale)

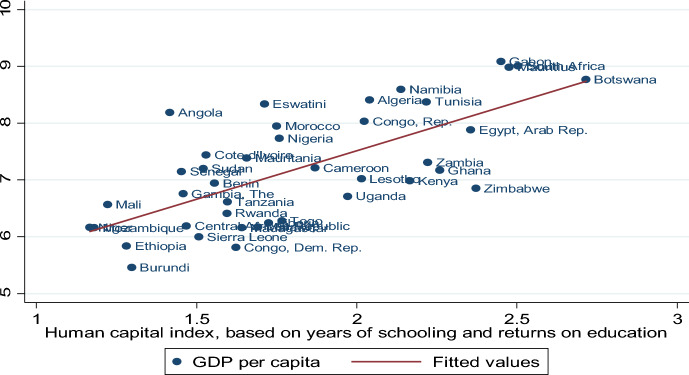

Figure 4 presents a correlation analysis between human capital and the level of economic development in Africa. The figure shows a positive relationship between the human capital index and GDP per capita. Figure acts as a preliminary test of the findings of the study. The figure could tempt us to arrive at the conclusion that human capital enhances the level of economic development in Africa. Due to some estimation issues, such as the problem of endogeneity, multicollinearity and time invariant that the scatter plot could not address, we adopt an empirical strategy of the two-step system GMM to arrive at our conclusion.

Fig. 4.

Scatter plot of the Human capital–economic development correlation

Figure 5 presents the correlation between human capital scale of the female and the male gender and GDP per capita. The figure shows a strong positive correlation between human capital of both genders and GDP per capita. The positive correlation in Figure confirms that presented in Fig. 4. The correlation analysis indicate that the level of economic development in Africa is enhanced by human capital development irrespective of whether it is the male or the female human capital index.

Fig. 5.

The relationship between human capital and economic development in Africa

Control variables

Human capital is not the sole determinant of economic growth. There are other factors that could have an influence on the level of economic growth. The choice of these factors is inspired by the existing literature on economic growth. The study employs trade openness as an indicator of economic development inspired by the works of Miao et al. (2020), Egyir et al (2020) and Abendin and Duan (2021). Trade is expected to have a positive influence on the level of economic growth in Africa. According to the existing literature, FDI is a determining factor of economic development (Asongu and Odhiambo 2020; Akpan et al. 2014; Ofori and Asongu 2021). FDI is expected to influence GDP per capita positively. Inflation is widely employed in extant literature as a factor that can influence the level of economic growth (Asongu and Odhiambo 2020; Akpan et al. 2014; Ofori and Asongu 2021; Rao et al. 2020). The rate of inflation is expected to have a negative influence on the level of economic growth in Africa. ICT is widely employed as an indicator of economic development especially in studies conducted in Africa (Asongu and Odhiambo 2020; Adeleye and Eboagu 2019). ICT is expected to have a positive effect on the level of economic development. Gross savings is also employed as an indicator of economic growth in existing literature (Ribaj and Mexhuani 2021; Van Wyk and Kapingura 2021).

Model specification

Many authors have developed different growth models over the years. Some of the notable growth models widely employed in literature are those of the Harrod–Domar Model, the Solow model and the Lucas human capital model of economic growth. The Harrod–Domar Model suggests that the rate of economic growth is essentially dependent on the level of savings and the amount of capital in an economy. Harrod–Domar argued in their model that higher savings enable higher investment since interest rates decrease with increasing availability of funds for investment. The authors further argued that the second factor of capital increases the possibility of an economy's output but becomes efficient if a lower capital-output ratio yields higher productivity in terms of output which therefore means that investment is more efficient and the economic growth rate will increase, accounting for capital depreciation.

Accounting for technology as a factor of production, Solow considers technology, capital and labor as determining factors of the level of output in an economy. We adopt the variable Cobb–Douglas function with the assumption of constant returns to scale and decreasing marginal returns to factor accumulation to present the Solow model, this result in the following equation.

| 1 |

represents output, and signify physical capital and labor respectively, signifies the coefficient of capital and (1– represents that of labor. Ait represents an autonomous technological change. According to the exogenous growth theory of Solow, only the physical capital and labor influences productivity and technological progress is considered to be exogenous and independent to growth.

| 2 |

Establishing this relation in the Solow model demonstrates that the variations in the level of output growth ( depends on the variations in the growth rate of factors that can influence its growth, such as technical progress, capital, and labor input. Due to the fact that the Solow model considered as coefficients that explain the total variation in output without considering the elasticity of human capital accumulation, the endogenous growth models of Lucas, Mankiw, Romer, and Weil modified the Solow model to include the human capital stock as an important production factor. Lucas (1988) establishes in his work to demonstrate how growth can be influenced by human capital accumulation (Tiwari and Mutascu 2011; Traore and Sene 2020). Improving the level of education and training, each individual increases the stock of human capital of the nation and the same vein, helps improve productivity of the national economy (Lucas 1988). The model considering human capital as a factor of growth is presented in Eq. 3.

| 3 |

The additional variable is human capital presented by h which varies with time and influences the level of growth. A thorough analysis of the determining factors will permit a better understanding of economic productivity considering the dynamisms of the new endogenous growth models in determining the optimal level of physical capital available for investments which is also largely determined in a competitive economy by real wages, interest rates, assets prices and real rent in their respective marginal productivities. This capital has a percentage that depreciates over time incorporated in the capital model with an exogenous levels of technological advancement and population growth that affect the level of economic activities and total output. The levels of prices and interest rates also affect the amount of human capital attributed for economic activities and thus determines total output (Traore and Sene 2020; Revenga 1997). Applying a log Cobb–Douglas function in Eq. 3 gives.

| 4 |

The level of growth rates is highly influenced by human capital, labor, technology, and physical capital. The growth rate is obtained by taking the derivative of Eq. 4 with respect to time.

| 5 |

represents growth rate of GDP influenced by human capital, technology, labor, and capital input. From this model with human capital incorporated, we draw our empirical model as follows:

| 6 |

Justifications of the transmission channels

Three transmission channels through which human capital could influence the level of economic growth in Africa are identified. First, the channel of ICT, human capital through its interaction with ICT can enhance the level of economic growth. Technological diffusion and education boost the level of productivity through an increase in the workforce. Countries more advanced in technology with a better knowledge economy have higher levels of growth than countries that have not adapted to new technological know-how (Asongu and Tchamyou 2018). ICT and human capital are both employed in literature as indicators of economic growth (Ofori and Asongu 2021). Second, trade openness can influence the effect of human capital on economic development (Intisar et al. 2020; Soukiazis and Antunes 2012). Openness increases human capital accumulation due to exchanges between countries with labor intensive and capital intensive which is less in closed economies. Due to the comparative advantage possessed by developed economies in terms of human capital development, trade liberalization increases the transmission of this human capital accumulation to developing countries which helps to boost their productivity (Intisar et al. 2020). Foreign direct investment is identified as another channel through which human capital can influence the level of economic growth. Foreign direct investments engender favorable outcomes on economic growth dynamics with increasing human capital accumulation. Human capital boosts the absorption capacity of foreign direct investments toward attaining economic sustainability (Asongu and Odhiambo 2020). FDI and human capital are employed as both determinants of economic development but not as a transmission channel through which development is enhanced. As such, the study determines how these channels can influence the effect of human capital on economic development. Following the justification of the variables employed in the study, it, therefore, suffices to present the estimated equation with all the variables. Equation 7 presents the variables of the study with the transmission channels through which the level of economic development could be influenced.

| 7 |

where i and t denote individual countries and time respectively, GDPit signifies Gross Domestic Products which is employed as an indicator of economic development, HC represents human capital, FDI denotes foreign direct investments, savings denotes gross domestic savings, trade = trade openness, internet signifies internet penetration, TM is the transmission mechanism variable that at first instance takes internet, second foreign direct investments, and third trade openness. U signifies the error term that accounts for sample fluctuations and poor specifications in the estimated model. The descriptive analysis of the variables employed in the study is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | 1850 | 6.72 | 1.075 | 4.605 | 10.041 |

| Human capital index | 1600 | 1.638 | 0.41 | 1.02 | 2.939 |

| Human capital female scale | 133 | 0.411 | 0.073 | 0.292 | 0.678 |

| Human capital male scale | 98 | 0.404 | 0.062 | 0.289 | 0.557 |

| Foreign direct investment | 1842 | 3.181 | 7.907 | – 28.624 | 161.824 |

| Inflation | 1839 | 39.746 | 650.735 | – 31.566 | 26,765.857 |

| Trade | 1643 | 66.244 | 33.006 | 1.219 | 225.023 |

| Savings | 1592 | 15.224 | 16.328 | – 60.117 | 88.389 |

| Internet | 1131 | 7.641 | 13.889 | 0.0310 | 75 |

Equation 7 is differentiated to obtain Eq. 8 which permit to interpret the coefficients of human capital and the interactive effect with internet, trade and foreign direct investments as elasticity.

| 8 |

The coefficient signifies the value at which the level of economic growth will change if there is a 1% change in the level of human capital. represent the coefficients of the modulating coefficients of internet, trade, and foreign direct investments with human capital on the level of economic development. The net effect of these modulating variables are further computed using the unconditional and the conditional coefficients which is presented in Eq. 9.

| 9 |

where Ω is the average of the policy modulating variables. We further decompose the net effects to provide thresholds for complementary policies. The threshold computation is presented in Eq. 10.

| 10 |

The three thresholds established in Eq. 10 are only computed if it ranges between the maximum and the minimum values of the modulating variables whose characteristics are presented in Table 1 of descriptive statistics.

Methodology

The study adopts the system Generalized Method of Moment (GMM) strategy for its empirical analysis. The GMM strategy is employed to account for the limits presented by the Ordinary Least Square (OLS) model adopted for the baseline analysis. The OLS model does not account for endogeneity resulting from causality bias and unobserved heterogeneity. For the study to provide efficient estimates with the GMM strategy, the following conditions have to hold: First, the number of cross sections should exceed the periods of each cross-section (Nchofoung and Asongu 2022a, b; Kouladoum et al. 2022). The first condition is fulfilled since the study covers a sample of 48 countries over 20 years. Second, the correlation between the dependent variable and its first lag is 0.990 which is higher than the threshold of 0.800 considered an established rule of thumb for assessing persistence in an economic indicator in accordance with attendant literature (Asongu and Odhiambo 2020; Wirajing and Nchofoung 2023). Given that the GMM in difference is consistent under heteroscedasticity, the system GMM is applied in this study. Besides, to limit the proliferation of instruments, the forward orthogonal deviation is used after collapsing the instruments (Nchofoung and Asongu 2022a, b; Kouladoum et al. 2022; Djeunankan et al. 2023).

The two-step system GMM strategy adopted in the study can be summarized with its subsequent equations in levels Eq. (11) and in first difference Eq. (12) as follows:

| 11 |

| 12 |

GDP represents Gross Domestic Products widely used in literature as an indicator of economic development. HC signifies human capital. Control variables have been explained in Eq. 1. W in Eq. (11) and (12) represents the vector of control variables, is the country specific effect, is the time-specific constant, τ represents the lagging coefficient and is the residual term.

The problems usually associated with the GMM framework are the problem of identification, exclusion and simultaneity restrictions. To solve these problems, all explanatory variables are treated as exogenous with the time-fixed effect used as instruments in the underlying regression (Nchofoung and Asongu 2022a, b; Wirajing et al. 2023; Kouladoum et al. 2022). We proceed to conduct a cross-sectional dependence test to choose between the first and the second-generation unit root test. In this regard, we proceed with the Pesaran (2015) test for cross-sectional dependence whose results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pesaran (2015) test for weak cross-sectional dependence

| Variables | CD test | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Human capital index | 110.617 | 0.000*** |

| GDP | 126.473 | 0.048* |

| FDI | 5.825 | 0.000*** |

| Inflation | 12.252 | 0.000*** |

| Trade | 13.037 | 0.000*** |

| Savings | – 1.745 | 0.662 |

| Internet | 84.249 | 0.000*** |

H0: errors are weakly cross-sectional dependent

H0

errors are weakly cross-sectional dependent

The Pesaran cross-sectional dependence test indicates that the null hypothesis of weakly cross-sectional dependence is rejected for all the variables except for the variable savings whose probability value is statistically insignificant. In addition, the Frees and the Pesaran cross-sectional dependence test of the global model are employed to confirm the acceptance of the alternative hypothesis indicating the probability values of all but one variable to be statistically significant. Based on the Frees (1995) cross-sectional dependence test whose findings are presented in Table 5, we reject the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence beyond the critical value (1%) by assuming the presence of cross-sectional dependence in the baseline model. Similarly, in Pesaran’s (2004) test, we reject (P value < 0.1) cross-sectional independence, confirming the presence of cross-sectional independence in the baseline model. The presence of the cross-sectional dependence test suffices the computation of the second-generation unit root test whose necessity is further examined in the heterogeneity slope test whose results are presented in Table 3.

Table 5.

The effect of human capital on economic development in Africa (System GMM technique)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | Driscoll/Kraay | GMM | |

| Variables | GDP | GDP | GDP |

| L.GDP | 0.935*** | ||

| (0.00300) | |||

| Human capital index | 1.106*** | 1.909*** | 0.0503*** |

| (0.0699) | (0.449) | (0.00699) | |

| FDI | – 0.0177*** | 0.00767*** | – 0.00644*** |

| (0.00478) | (0.00265) | (0.000359) | |

| Inflation | – 0.000291 | – 4.71e-05 | 0.00428*** |

| (0.000209) | (7.90e-05) | (0.000235) | |

| Trade | 0.00813*** | – 0.00480*** | 0.00122*** |

| (0.000912) | (0.00127) | (7.67e-05) | |

| Savings | 0.0213*** | 0.0123*** | 0.00204*** |

| (0.00150) | (0.00242) | (4.87e-05) | |

| Internet | 0.0123*** | 0.00309* | – 0.00123*** |

| (0.00181) | (0.00170) | (0.000119) | |

| Constant | 4.128*** | 3.759*** | 0.325*** |

| (0.114) | (0.787) | (0.0202) | |

| Observations | 513 | 513 | 425 |

| R-squared | 0.714 | ||

| r2_adjusted | 0.710 | ||

| Number of groups | 28 | 28 | |

| Wooldridge test | 0.0000*** | ||

| Breusch–Pagan / Cook-Weisberg test | 0.0174* | ||

| Pesaran’s CD test (p val) | 0.0000*** | ||

| Frees statistic | 12.659 | ||

| Critical value (1%) | 0.3169 | ||

| Prop > AR(1) | 0.000422 | ||

| Prop > AR(2) | 0.233 | ||

| Instruments | 29 | ||

| Hansen > Prop | 0.230 |

Standard errors in parentheses

***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1

Table 3.

Slope homogeneity test

| Delta | Statistic | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 11.551 | 0.000 | |

| adj | 15.522 | 0.000 |

Table 3 presents the heterogeneity test for the estimated baseline model with the null hypothesis of homogeneous coefficients. The study adopts the Pesaran and Yamagata (2008) test whose findings indicate statistically significant probability values at 1%, prompting the acceptance of the alternative hypothesis of heterogeneous coefficients. Considering the presence of cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneous coefficients, we use the test of Pesaran (2007) based on the standard unit root statistics in a cross-sectional ADF (CADF) regression whose findings are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Second generation Pesaran's CADF unit root test

| Variables | CD test | P value | Judgment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human capital index | – 1.399 | 0.081* | Stationary at level |

| GDP | – 1.666 | 0.048* | Stationary at level |

| FDI | – 2.159 | 0.015* | Stationary at level |

| Inflation | – 3.088 | 0.001** | Stationary at level |

| Trade | – 1.745 | 0.017* | Stationary at level |

| Savings | – 1.980 | 0.005** | Stationary at level |

| Internet | – 1.206 | 0.050* | Stationary at level |

Table 4 presents the Pesaran's CADF second-generation unit root test. As posited by Djeunankan et al. (2023), Ngouhouo et al. (2021) and Kengdo et al. (2020) the CADF panel unit root test is the only second-generation unit root test that accounts for the cross-sectional dependency and heterogeneity simultaneously among countries. As presented in Table 4, the null hypothesis is rejected for all variables, confirming the stationarity of the variables as indicated by their significance probability values.

Results and discussion

Direct effect results

Section "Results and discussion" presents and discusses the results. The section commences with the direct effect results presented in Table 4. The direct effect results are estimated using the ordinary least square model, the Driscoll/Kraay technique and a robust instrumental GMM strategy. The direct effect results of the OLS and the Driscoll/Kraay models indicate a significant positive effect of human capital on economic development. However, the study cannot depend on these two models to provide its conclusive remarks since it has some weaknesses as the strategy does not address the problems of endogeneity, unobserved heterogeneity and simultaneity bias which is addressed by the GMM technique. Also, the OLS and Driscoll/Kraay’s models are not robust with uncorrelated and homoscedastic errors. The multicollinearity test results presented in appendix 3 indicate the absence of multicollinearity since the average VIF for all variables is less than 6 and the largest individual VIF is also less than 10, following the works of Saadi (2020) and Asngar et al. (2022). Also, the Wooldridge and Breusch–Pagan test results presented in Table 5 indicate that there exist problems of autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity in the baseline model. In this regard, the two-step system Generalized Method of Moment is applied to address both the problems of heteroskedasticity, the autocorrelation of errors and cross-sectional dependence which is partly addressed by the Driscoll/Kraay strategy. The results of the two-step system Generalized Method of Moment are presented in the last column of Table 5, considered as Eq. 3.

Provided the proliferation problem raised in contemporary studies, the instrumentation process is controlled to ensure that the model is well estimated and unbiased. The Hansen probability and the AR (2) test indicate efficient estimates. The GMM findings presented in Table 5 are well estimated given that the Hansen probability test and the AR (2) are all greater than 10%. The nature of the AR (2) and Hansen probability validate the instruments used in the study. Table 5 presents the direct effect results of the OLS, Driscoll/Kraay and the GMM model. The results of the GMM model are more reliable as the technique addresses the problems of endogeneity, heteroscedasticity, multicollinearity, unobserved heterogeneity and simultaneity bias. The results indicate that the level of economic growth measured by Gross Domestic Product per capita in Africa is significantly ameliorated by growth in human capital. This is supported by the findings of Intisar et al. (2020), Soukiazis and Antunes (2012), and Ofori and Asongu (2021). Controlling for other factors that could influence the level of economic growth; we noticed that foreign direct investments hurt the level of economic growth in Africa. The negative effect contradicts the findings of Ofori and Asongu (2021) and Akpan et al., (2014), but corroborates those of Intisar et al. (2020). Foreign direct investment can hurt gross domestic product if the growth of the home-based industries or investments is being perturbed by giant multinational industries. The benefits of foreign direct investments are mostly to the side of the foreign country since most foreign direct investments in Africa set by the Western countries exploit the African natural resources to produce their products with cheap labor. The findings further reveal a negative effect of price instability on economic development. Inflation destabilizes economic activities. The effect of price instability affects the financial market through the demand and the supply of funds which has major consequences on the economy. The resulting negative effect of inflation on economic growth is supported by the findings of Ofori and Asongu (2021). Trade openness has a significant positive impact on the level of economic growth in Africa. The finding on the positive effect of trade on economic development corroborates that of Intisar et al. (2021) and Miao et al. (2020). Savings has a statistically significant effect on the level of economic growth in Africa. Savings procure positive effects on economic growth in the long run if the amount saved is invested in productive businesses that contribute to growth in the gross domestic product (Ribaj and Mexhuani 2021).

Robustness analysis

To ensure the reliability of the study findings, we test for the robustness of the results by adopting a quantile regression as it examines the initial levels of economic growth. Table 6 presents the results of the Quantile regression estimates at the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 90th quantiles. For more robustness checks, we extracted another data set from the World Development Indicators of the World Bank for the years 2017, 2019 and 2020. The database contains the human capital index scale at gender parity whose estimates are presented in the first row of Table 7, the human capital index female scale (second row of Table 7) and the human capital index for the male scale (third row of Table 7). The robustness checks are based on the Quantile regressions, whose estimates are on the effect of human capital on economic development at different points of the conditional distribution. The quantile regressions are adopted in literature as a robust regression technique that allows for a typical assumption of normality of the error term (Belaïd et al. 2021; Koenker and Bassett 1978). The quantile regression also estimates models with censoring (Buchinsky 2002, 1995). The quantile regression results suggest an exclusively positive effect of human capital on economic growth at different points in the quantile conditional distribution. The coefficients are significant at both the lower and the upper quantiles.

Table 6.

The effect of human capital on economic development in Africa (Quantile regressions)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantiles levels | (0.10) | (0.25) | (0.50) | (0.75) | (0.90) |

| Variables | GDP | GDP | GDP | GDP | GDP |

| Human capital index | 1.050*** | 1.150*** | 1.189*** | 1.021*** | 1.123*** |

| (0.0725) | (0.0782) | (0.0672) | (0.0706) | (0.0639) | |

| FDI | 0.0146*** | – 0.0167*** | – 0.0178*** | – 0.0274*** | – 0.0318*** |

| (0.00496) | (0.00535) | (0.00460) | (0.00483) | (0.00438) | |

| Inflation | – 0.00106*** | – 0.00122*** | – 9.62e-05 | – 0.000223 | – 0.000328* |

| (0.000217) | (0.000234) | (0.000201) | (0.000211) | (0.000191) | |

| Trade | – 0.000240 | 0.00772*** | 0.00860*** | 0.0119*** | 0.0131*** |

| (0.000946) | (0.00102) | (0.000878) | (0.000921) | (0.000835) | |

| Savings | 0.0248*** | 0.0230*** | 0.0226*** | 0.0185*** | 0.0142*** |

| (0.00156) | (0.00168) | (0.00144) | (0.00151) | (0.00137) | |

| Internet | 0.0152*** | 0.0109*** | 0.00772*** | 0.0116*** | 0.00774*** |

| (0.00188) | (0.00202) | (0.00174) | (0.00183) | (0.00165) | |

| Constant | 3.876*** | 3.734*** | 3.955*** | 4.506*** | 4.638*** |

| (0.118) | (0.127) | (0.109) | (0.115) | (0.104) | |

| Observations | 513 | 513 | 513 | 513 | 513 |

| Rank | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| sum_rdev | 86.50 | 168.8 | 222.8 | 174.6 | 88.19 |

| sum_adev | 49.44 | 88.75 | 109.2 | 85.66 | 44.52 |

Standard errors in parentheses

***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1

Table 7.

The effect of human capital on economic development in Africa (Periods; 2017, 2018 and 2020)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantiles | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.90 |

| Variables | GDP | GDP | GDP | GDP | GDP |

| Human capital index | 3.227*** | 2.764*** | 1.667** | 2.314*** | 2.466*** |

| (0.472) | (0. 448) | (0. 423) | (0. 572) | (465) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 66 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 66 |

| Female human capital | 2.081*** | 0. 607* | 0.692* | 2.196** | 2.081*** |

| (0.462) | (0. 322) | (0.301) | (0.624) | (0.472) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 | 53 |

| Male human capital | 3.149*** | 0.537 | 0.466 | 1.035* | 3.149*** |

| (0.589) | (0.371) | (0.333) | (0.559) | (0.589) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 52 | 52 | 52 | 52 | 52 |

Standard errors in parentheses

***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1

The findings presented in Table 6 are that of the quantile regression which shows that the level of human capital enhances economic growth in Africa. The findings are consistent at the lower quantiles to the upper quantiles indicating an exclusive significant positive effect of human capital on economic development. The results presented in Table 7 represent the case where human capital is measured by the three different indicators. Firstly, proxied as a gender parity index, secondly as a female human capital index scale and thirdly as a male gender human capital index scale whose results are all presented in Table 7. Table 6 reveals that the human capital index scale at gender parity has an exclusive positive significant effect on economic development in Africa at both the lower (0.10th and 0.25th) and the upper (0.75th and 0.90th) quantiles. It also reveals that the level of economic development in Africa is ameliorated by female human capital accumulation throughout the quantiles. The result presented in Table 7 further indicates that the human capital index for the male scale has an exclusive positive significant effect on economic development in Africa. The robustness checks presented in Table 7 aiming to examine human capital across different genders were limited to only three years because of data constrained. The study has passed robustness checks as the effect of human capital on economic development in Africa remained significantly positive throughout the five tables of results provided across different quantiles. The findings of the study are supported by the findings of Intisar et al. (2020), Soukiazis and Antunes (2012), and Ofori and Asongu (2021) and also validate the first hypothesis on the role of human capital in boosting economic growth in Africa.

Indirect effect results

Sect. "Indirect effect results" presents the indirect effect results of the transmission channels through which the effect of human capital on economic growth could be affected. These channels have been chosen based on existing literature on the determinants of economic development. The interaction between human capital, ICT, FDI and trade openness are the transmission channels selected in the study. ICT and human capital are both employed in literature as indicators of economic growth (Ofori and Asongu 2021). Similarly, it is well documented in the literature that trade openness can influence the effect of human capital on economic growth (Intisar et al. 2020; Soukiazis and Antunes 2012). Moreover, foreign direct investment can influence the effect of human capital on the level of economic growth. The indirect effect results are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

The role of internet, trade and FDI in modulating the effect of human capital on economic development in Africa

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | GDP | GDP | GDP |

| L. GDP | 0.951*** | 0.916*** | 0.952*** |

| (0.00551) | (0.00715) | (0.00619) | |

| Human capital | 0.0234** | 0.166*** | 0.0222*** |

| (0.00947) | (0.0490) | (0.00739) | |

| FDI | – 0.00584*** | – 0.00650*** | – 0.0124*** |

| (0.000535) | (0.000462) | (0.00203) | |

| Inflation | 0.00328*** | 0.00418*** | 0.00465*** |

| (0.000470) | (0.000369) | (0.000373) | |

| Trade | 0.000902*** | 0.00416*** | 0.000614*** |

| (0.000150) | (0.000917) | (0.000103) | |

| Savings | 0.00174*** | 0.00238*** | 0.00162*** |

| (0.000154) | (0.000217) | (0.000156) | |

| Internet | – 0.00404*** | – 0.000978*** | – 0.00150*** |

| (0.000872) | (0.000262) | (0.000133) | |

| Internet*Human capital | 0.00120*** | ||

| (0.000351) | |||

| Trade*Human capital | – 0.00149*** | ||

| (0.000536) | |||

| FDI*Human capital | 0.00486*** | ||

| (0.00125) | |||

| Net effect | 0.03257 | 0.06729 | 0.23746 |

| Threshold | 19.5 | 111.409 | 4.5679 |

| Constant | 0.299*** | 0.229*** | 0.289*** |

| (0.0317) | (0.0729) | (0.0336) | |

| Observations | 412 | 387 | 388 |

| Number of ID | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| Prop > AR(1) | 0.000338 | 0.000528 | 0.000393 |

| Prop > AR(2) | 0.128 | 0.281 | 0.283 |

| Instruments | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Hansen > Prop | 0.223 | 0.285 | 0.165 |

Standard errors in parentheses

***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1

Table 8 presents the results of the transmission channels through which the effect of human capital on economic growth is modulated. The results reveal an enhancing effect of human capital on economic growth in Africa. The results presented in Table 8 show that the effect of human capital on economic growth can become negative if interacted with trade openness. The negative role of trade openness on the human capital–economic growth nexus is feasible given that African countries depend more on the primary sector and specifically the agricultural sector to boost their GDP per capita than trade in human capital products which are relatively insignificant given the low human capital accumulation in Africa. The results also reveal that the level of economic growth in Africa is modulated by the interaction between human capital and internet penetration. Information and communication technology (ICT) is identified as a channel through which human capital can influence the level of economic development in Africa. ICT is proxied in the study by internet penetration. The GMM estimates reveal that internet penetration plays a positive significant role in modulating the effect of human capital on economic development in Africa. This is explained by the fact that the level of human capital accumulation increases with increasing internet penetration and technological innovation (Ofori and Asongu 2021). The rate of internet penetration in Africa has increased over the years and contributes to increased scholarly research output and the average number of school enrollments which are signs of sustainable development in an economy. Trade openness plays a negative role in modulating the effect of human capital on economic development in Africa, though this negative effect is nullified by the positive net effects outcome. The negative effect could still be a possibility as most African economies export raw materials to Western countries at very low prices and import manufactured products. The countries that import raw materials from Africa seem to have a comparative advantage over African countries (Malefane 2018). The interaction between human capital and foreign direct investment resulted in a positive significant effect on the level of economic development in Africa. The positive interactive effect of human capital and foreign direct investments on the level of economic growth conforms to the findings of Ofori and Asongu (2021) whose results indicate the enhancement of the level of economic development by human capital, and partly in accordance with the findings of Mohanty and Sethi (2019), and Demissie (2015) who documented how FDI is instrumental in the human capital–economic growth relationship in BRICS and developing economies respectively. The results are justifiable if foreign direct investment results in positive domestic payment balances. Internet penetration interacts with human capital to procure a positive net effect. This positive net effect is nullified at the internet penetration threshold of 19.5 (users per every 100 in the population). This negative effect at high levels of digital penetration can be justified by the fact that human capital is still highly underdeveloped in Africa and low-skilled capital are in the majority. At high levels of digitalization, the economies would lack the necessary human capital required to operate these technologies. In this respect, the unskilled majority labor force would lose their job increasing the rate of unemployment in the economy leading to an increase in social instability and consequently a decrease in economic growth. The findings also indicate a positive net effect of trade interaction with human capital on economic growth which is nullified at a trade openness threshold of 111.409 (% of GDP). Similar patterns are followed by the interaction between foreign direct investments and human capital which produces positive net effects. The foreign direct investments threshold required to nullify this net effect is 4.5697 (%GDP). The results, therefore, suggest that for efficient growth to be enhanced, the trade openness in African economies should not exceed the established threshold. In essence, African economies still have struggling industries that cannot compete internationally with some multinational firms from other developed economies, as such require some sort of protectionism from the State to attain maturity to be able to compete. Above the established threshold, therefore, these small firms are exposed to foreign competition leading to the eviction effect and consequently a fall in economic growth.

Conclusion and policy recommendations

This study investigated the effect of human capital on economic growth in 48 African countries from 2000 to 2019. The system GMM and the Quantiles regressions strategies have been adopted to address potential endogeneity. Human capital has been measured as a gender parity index, Human capital index for female scale and human capital index for the male gender. The study employed GDP per capita as a proxy for economic growth. The study further identified ICT, trade openness and foreign direct investments as transmission channels through which human capital can affect the level of development in Africa. The findings reveal a statistically significant effect of human capital on economic development in Africa. Human capital for both genders also indicates a statistically significant positive effect on gross domestic product per capita. The GMM estimates used for the interpretation of the results show that internet penetration plays a significant positive role in modulating the effect of human capital on the level of economic development in Africa with a positive net effect that is nullified at the internet threshold of 19.5. The findings also show a positive role played by foreign direct investment in modulating the effect of human capital on economic development with a positive net effect that is nullified at the foreign direct investments thresholds of 4.5697. Other factors, such as internet penetration, the rate of inflation, savings, FDI, and trade, are identified as control variables that could influence the level of economic development in Africa. The results provided show that trade openness enhances the level of economic development in Africa. Gross savings also appeared to significantly influence the level of economic development. Trade openness appeared to enhance economic growth in Africa and also produces a positive net effect when it acts as a channel of human capital development. This positive net effect of trade openness is nullified at a threshold of 111.409 trade (% of GDP).

The study recommends policymakers invest more in the education and the health sectors in other to enhance the level of human capital development in Africa. The enhancement of human capital will ameliorate the level of economic development. ICT infrastructures should be promoted to ensure growth in human capital and technological adaptability in most African economies since technology appeared to be a channel through which human capital enhances the level of economic development. As a perspective for further studies, a study should be conducted to determine the influence of education and health inequality on the level of economic development in Africa. Research should also be done in individual countries to identify the channels through which human capital can retard sustainable development, such as capital flight, corruption, and embezzlement of public funds by public officials.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

All the authors participated in the conceptualization, writing, and collection of data, analyses and interpretations.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study is available upon reasonable request addressed to the corresponding author.

Code availability

The Stata codes are available upon reasonable request addressed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors present no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This work is not under consideration in another outlet

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Central African Republic (CAR), Chad, Comoros, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cote d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Contributor Information

Muhamadu Awal Kindzeka Wirajing, Email: wirajingmuhamadu@gmail.com.

Tii N. Nchofoung, Email: ntii12@yahoo.com

Felix Mejame Etape, Email: etapeson3@gmail.com.

References

- Abendin S, Duan P. International trade and economic growth in Africa: the role of the digital economy. Cogent Econ Financ. 2021;9(1):1911767. doi: 10.1080/23322039.2021.1911767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adeleye N, Eboagu C. Evaluation of ICT development and economic growth in Africa. NETNOMICS: Econ Res Electron Netw. 2019;20(1):31–53. doi: 10.1007/s11066-019-09131-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adeleye BN, Bengana I, Boukhelkhal A, Shafiq MM, Abdulkareem HK. Does human capital tilt the population-economic growth dynamics? Evidence from middle east and north African countries. Soc Indic Res. 2022;162(2):863–883. doi: 10.1007/s11205-021-02867-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aghion P, Howitt P, Murtin F (2010) The relationship between health and growth: when Lucas meets Nelson-Phelps (No. w15813). National Bureau of Economic Research

- Ahmed Z, Asghar MM, Malik MN, Nawaz K. Moving towards a sustainable environment: the dynamic linkage between natural resources, human capital, urbanization, economic growth, and ecological footprint in China. Resour Policy. 2020;67:101677. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akpan U, Isihak S, Asongu S (2014) Determinants of foreign direct investment in fast-growing economies: a study of BRICS and MINT. African Governance and Development Institute WP/14/002

- Asongu SA, Odhiambo NM. Foreign direct investment, information technology and economic growth dynamics in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telecommun Policy. 2020;44(1):101838. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2019.101838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asongu SA, Tchamyou VS (2018) Human capital, knowledge creation, knowledge diffusion, institutions and economic incentives: South Korea versus Africa. Contemporary Social Science

- Bakibinga-Gaswaga E, Bakibinga S, Bakibinga DBM, Bakibinga P. Digital technologies in the COVID-19 responses in sub-Saharan Africa: policies, problems and promises. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(Suppl 2):38. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.23456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barro RJ. Economic growth in a cross section of countries. Q J Econ. 1991;106(2):407–443. doi: 10.2307/2937943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barro RJ, Sala-i-Martin X. Public finance in models of economic growth. Rev Econ Stud. 1992;59(4):645–661. doi: 10.2307/2297991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barro RJ, Mankiw NG, Sala-i-Martin X (1992) Capital mobility in neoclassical models of growth (No. w4206). National Bureau of Economic Research

- Becker GS. Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom N, Jones CI, Van Reenen J, Webb M. Are ideas getting harder to find? Am Econ Rev. 2020;110(4):1104–1144. doi: 10.1257/aer.20180338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchinsky M. Quantile regression, Box-Cox transformation model, and the US wage structure, 1963–1987. J Econom. 1995;65(1):109–154. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(94)01599-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchinsky M. Economic applications of quantile regression. Heidelberg: Physica; 2002. Quantile regression with sample selection: estimating women’s return to education in the US; pp. 87–113. [Google Scholar]

- Chekina VD, Vorhach OA. The impact of education expenditures on economic growth: empirical estimation. Econ Ind. 2020;3(91):96–122. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury MB. Internationalisation of education and its effect on economic growth and development. World Econ. 2022;45(1):200–219. doi: 10.1111/twec.13174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio E, Marianacci R, Mattoscio N. On human capital and economic development: some results for Africa. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2010;9:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das A, Sethi N. Effect of foreign direct investment, remittances, and foreign aid on economic growth: evidence from two emerging South Asian economies. J Public Aff. 2020;20(3):e2043. doi: 10.1002/pa.2043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Long JB, Summers LH. Equipment investment and economic growth. Q J Econ. 1991;106(2):445–502. doi: 10.2307/2937944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Long JB, Summers LH, Abel AB. Equipment investment and economic growth: how strong is the nexus? Brook Pap Econ Act. 1992;1992(2):157–211. doi: 10.2307/2534583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demissie M (2015) FDI, human capital and economic growth: a panel data analysis of developing countries

- Diebolt C, Hippe R. Human capital and regional development in Europe. Cham: Springer; 2022. Lessons from human capital evolution over the last 200 Years; pp. 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- Djeunankan R, Njangang H, Tadadjeu S, Kamguia B. Remittances and energy poverty: fresh evidence from developing countries. Util Policy. 2023;81:101516. doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2023.101516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donou-Adonsou F. Technology, education, and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telecommun Policy. 2019;43(4):353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2018.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egyir J, Sakyi D, Baidoo ST. How does capital flows affect the impact of trade on economic growth in Africa? J Int Trade Econ Dev. 2020;29(3):353–372. doi: 10.1080/09638199.2019.1692365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erich G (1996) Openness and economic growth in developing countries

- Fatima S, Chen B, Ramzan M, Abbas Q. The nexus between trade openness and GDP growth: analyzing the role of human capital accumulation. SAGE Open. 2020;10(4):2158244020967377. doi: 10.1177/2158244020967377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman GM, Helpman E. Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth. Eur Econ Rev. 1991;35(2–3):517–526. doi: 10.1016/0014-2921(91)90153-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek EA, Woessmann L. The economics of education. Elsevier; 2020. Education, knowledge capital, and economic growth; pp. 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- International labour organization (ILO) (2020). COVID-19 cruelly highlights inequalities and threatens to deepen them

- Kengdo AAN, Nchofoung T, Ntang PB. Effect of external debt on the level of infrastructure in Africa. Econ Bull. 2020;40(4):3349–3366. [Google Scholar]

- Koenker R, Bassett G., Jr Regression quantiles. Econom J Econom Soc. 1978;46(1):33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kouladoum JC, Wirajing MAK, Nchofoung TN. Digital technologies and financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telecommun Policy. 2022;46(9):102387. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2022.102387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal J, Paliwoda-Pękosz G. ICT for global competitiveness and economic growth in emerging economies: economic, cultural, and social innovations for human capital in transition economies. Inf Syst Manag. 2017;34(4):304–307. doi: 10.1080/10580530.2017.1366215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau LJ, Jamison DT, Liu SC, Rivkin S. Education and economic growth some cross-sectional evidence from Brazil. J Dev Econ. 1993;41(1):45–70. doi: 10.1016/0304-3878(93)90036-M. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RZ, Weinstein D (1999) Trade and growth: import-led or export-led? Evidence from Japan and Korea

- Lucas RE., Jr On the mechanics of economic development. J Monet Econ. 1988;22(1):3–42. doi: 10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mamadou Asngar T, Ongo Nkoa BE, Wirajing MAK (2022) The effect of banking competition on financial stability in central African economic and monetary community zone. Financ Stud 26(1)

- Mankiw NG, Romer D, Weil DN. A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Q J Econ. 1992;107(2):407–437. doi: 10.2307/2118477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Margarian A, Détang-Dessendre C, Barczak A, Tanguy C. Endogenous rural dynamics: an analysis of labour markets, human resource practices and firm performance. SN Bus Econ. 2022;2(8):1–33. doi: 10.1007/s43546-022-00256-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miao M, Lang Q, Borojo DG, Yushi J, Zhang X. The impacts of Chinese FDI and China-Africa trade on economic growth of African countries: the role of institutional quality. Economies. 2020;8(3):53. doi: 10.3390/economies8030053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty S, Sethi N. Outward FDI, human capital and economic growth in BRICS countries: an empirical insight. Transnatl Corp Rev. 2019;11(3):235–249. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty S, Sethi N. Does inward FDI lead to export performance in India? An empirical investigation. Global Bus Rev. 2021;22(5):1174–1189. doi: 10.1177/0972150919832770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nchofoung TN, Asongu SA. ICT for sustainable development: global comparative evidence of globalisation thresholds. Telecommun Policy. 2022;46(5):102296. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2021.102296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nchofoung TN, Asongu SA. Effects of infrastructures on environmental quality contingent on trade openness and governance dynamics in Africa. Renew Energy. 2022;189:152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2022.02.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ngouhouo I, Nchofoung T, NjamenKengdo AA. Determinants of trade openness in sub-Saharan Africa: do institutions matter? Int Econ J. 2021;35(1):96–119. doi: 10.1080/10168737.2020.1858323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ofori IK, Asongu SA. ICT diffusion, foreign direct investment and inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telemat Inform. 2021;65:101718. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2021.101718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogundari K, Awokuse T. Human capital contribution to economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: does health status matter more than education? Econ Anal Policy. 2018;58:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2018.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelinescu E. The impact of human capital on economic growth. Procedia Econ Financ. 2015;22:184–190. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00258-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasetyo PE, Kistanti NR. Human capital, institutional economics and entrepreneurship as a driver for quality & sustainable economic growth. Entrep Sustain Issues. 2020;7(4):2575. [Google Scholar]

- Rao DT, Sethi N, Dash DP, Bhujabal P. Foreign aid, FDI and economic growth in South-East Asia and South Asia. Global Bus Rev. 2020;24(1):31–47. doi: 10.1177/0972150919890957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman NU. FDI and economic growth: empirical evidence from Pakistan. J Econ Adm Sci. 2016;32(1):63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Revenga A. Employment and wage effects of trade liberalization: the case of Mexican manufacturing. J Law Econ. 1997;15(S3):S20–S43. [Google Scholar]

- Ribaj A, Mexhuani F. The impact of savings on economic growth in a developing country (the case of Kosovo) J Innov Entrep. 2021;10(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13731-020-00140-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romer PM. Increasing returns and long-run growth. J Polit Econ. 1986;94(5):1002–1037. doi: 10.1086/261420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romer PM. Capital, labor, and productivity. Brookings papers on economic activity. Microeconomics. 1990;1990:337–367. [Google Scholar]

- Saadi M. Remittance inflows and export complexity: New evidence from developing and emerging countries. J Dev Stud. 2020;56(12):2266–2292. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2020.1755653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]