Summary

While pathogenic variants can significantly increase disease risk, it is still challenging to estimate the clinical impact of rare missense variants more generally. Even in genes such as BRCA2 or PALB2, large cohort studies find no significant association between breast cancer and rare missense variants collectively. Here, we introduce REGatta, a method to estimate clinical risk from variants in smaller segments of individual genes. We first define these regions by using the density of pathogenic diagnostic reports and then calculate the relative risk in each region by using over 200,000 exome sequences in the UK Biobank. We apply this method in 13 genes with established roles across several monogenic disorders. In genes with no significant difference at the gene level, this approach significantly separates disease risk for individuals with rare missense variants at higher or lower risk (BRCA2 regional model OR = 1.46 [1.12, 1.79], p = 0.0036 vs. BRCA2 gene model OR = 0.96 [0.85, 1.07] p = 0.4171). We find high concordance between these regional risk estimates and high-throughput functional assays of variant impact. We compare our method with existing methods and the use of protein domains (Pfam) as regions and find REGatta better identifies individuals at elevated or reduced risk. These regions provide useful priors and are potentially useful for improving risk assessment for genes associated with monogenic diseases.

Keywords: clinical risk prediction, genic regions, selective constraint, variant interpretation, variants of uncertain significance, predispositional cancer risk, breast cancer, missense variant prediction

Methods to identify regions of genes that are most functionally impactful have relied on structural, evolutionary, and population data. We extend these approaches with REGatta, a method to estimate the clinical risk conferred by variants in regions of genes with established disease phenotypes using diagnostic and population cohort data.

Introduction

Large cohort studies have identified numerous genes in which individuals with germline variation have an increased predispositional risk of developing breast cancer.1 In particular, pathogenic coding variants in these genes are associated with significantly increased risk and are routinely screened in diagnostic testing panels.2 However, translating this risk to individuals with rare missense variants of uncertain significance (VUSs) continues to pose a challenge in the diagnostic setting.

Collectively, many individuals harbor rare VUSs in predispositional cancer-associated genes, potentially increasing their risk of disease. However, on the basis of the collective frequency of these variants, some are unlikely to be highly penetrant or functionally impactful.3,4 Given their low frequencies, it is challenging to assess their clinical significance with epidemiological evidence at the variant level.

One approach to improve risk assessment has been to define groups of missense variants or to identify genic regions that may confer higher or lower risk. These methods include modeling the depletion of variation with population sequencing data (selective constraint) with sets of exons,5 protein domains and regulatory sequences,6 three-dimensional protein structures,7 sequence contact sets,8 specific disease phenotypes,9 and evolutionary conservation data.10 These methods have excellent resolution in genes or regions under strong selection, even in genes whose function is not well established, but can otherwise be challenged by the effects of drift, population structure, or sampling variance at low allele counts.

Other approaches have identified regions that are enriched for pathogenic variation and depleted of putatively neutral variation, including at protein interfaces,11 within protein structures,12 across genes and gene families,13 in pathways,14 and homologous regions.15 These methods make use of known biological structures and abundant clinical diagnostic data but may also be challenged by the biases of prior diagnostic observations (whether from case ascertainment or assessment process) and consequently may not reflect the relative risk in population screening.

The interpretation of germline variants in clinically actionable disease-associated genes is becoming commonplace in biobanks and large population health studies. The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics recommends a set of 78 genes (ACMG SF v3.1) be reviewed, regardless of the indication for sequencing.16 Many of these genes are associated with predispositional cancer risk and are commonly screened in the diagnostic setting. The ACMG/Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) guidelines for sequence variant interpretation consider several related forms of evidence, including mutational “hot spots” or well-studied functional domains without benign variation (PM1) and high rates of known pathogenic and low rates of benign missense variants (PP2). Here, we develop a framework to improve the estimation of risk within gene regions for rare missense VUSs derived from clinical diagnostic and population health data. This approach may be useful toward identifying protein segments that confer higher or lower risk as well as providing an informative prior probability of pathogenicity for variation within a region.

Material and methods

Study design, setting, and participants

The UK Biobank (UKB) is a prospective cohort of over 500,000 individuals recruited between 2006 and 2010 of ages 40–69.17 Drawing from 200,625 participants with exome-sequencing data were included in this analysis, and we analyze 109,581 female participants for breast cancer.

Clinical endpoints

The primary clinical endpoints were specific to each condition—coronary artery disease (CAD) for familial hypercholesterolemia, breast cancer (BC) for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome, and colorectal cancer for Lynch syndrome. Case definitions for CAD, BC, and colorectal cancer were defined in the UKB via a combination of self-reported data confirmed by trained healthcare professionals, hospitalization records, and national procedural, cancer, and death registries, previously described at the disorder level.18

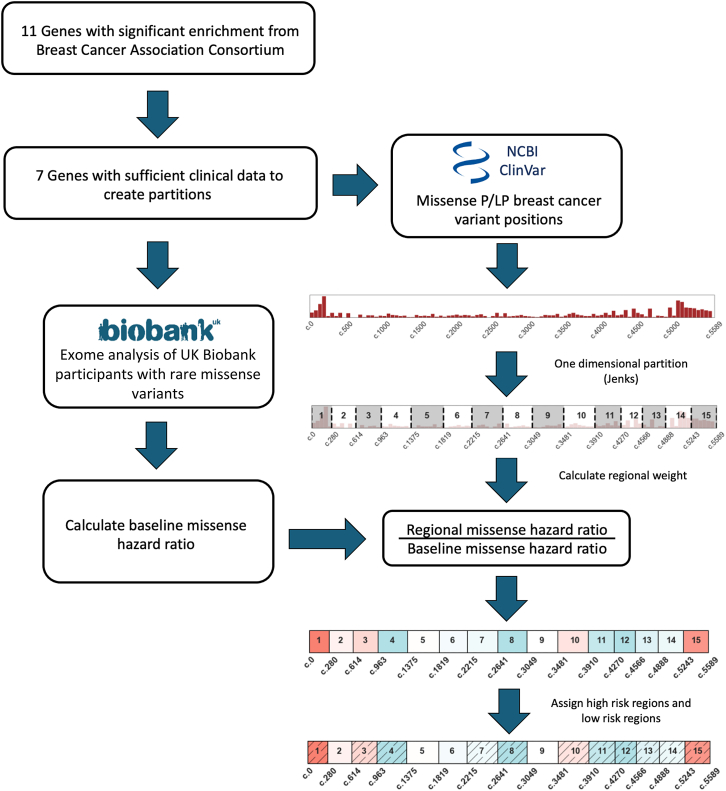

Defining genic regions with significant differences in germline cancer risk

To define genic regions with potentially distinct clinical risk of breast cancer, we identify segments that are enriched or depleted in pathogenic variant reports in ClinVar.19 We restrict our analyses to missense variants, removing all stop-gain, frameshift, and canonical splice-site variants. We then use Jenks natural breaks optimization to partition the transcript on the basis of the coding positions of pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) breast cancer reports.20 We break each transcript into 15 regions, or the maximum number of regions possible while maintaining sufficient numbers of individuals with missense variants in each region to make risk estimates (supplemental methods, Table S1).

We then make use of clinical data from the UKB to estimate the risk attributable to carrying a rare missense variant in each region.17 First, we establish a baseline risk for individuals who carry any rare missense variant in each gene. We perform a univariate Cox regression, comparing the risk for individuals with any rare missense variant to those without any variant.21 The resulting partial hazard for individuals with missense variants in each gene, GM, is used in further comparisons. We next calculate the risk of carrying a rare missense variant in each predefined protein region, . We compare the resulting partial hazard for each region, Gi, to GM to identify an elevated or reduced clinical risk in each region (Figure 1). The risk ratio is thresholded, defining a relative risk of 1.15 or above as a higher-risk region (HRR) or 0.85 or below as a lower-risk region (LRR). We define these sets of regions as

| (1) |

Figure 1.

Assessing regional risk using clinical diagnostic and population sequencing data

We analyze data from 34 genes from a well-powered breast cancer meta-analysis (Breast Cancer Association Consortium) for their potential to have protein regions that confer higher or lower clinical risk for individuals with rare missense variants.1 We restrict to seven genes with sufficient clinical diagnostic data in ClinVar and use the distribution of pathogenic variant reports to partition each gene into distinct regions (material and methods). Using those regional boundaries, we then use breast cancer status and population sequencing data from over 100,000 women in the UK Biobank to calculate the missense risk ratio in each region. We thresholded risk ratio values to label sets of regions as higher-risk regions (HRRs) or lower-risk regions (LRRs), and we find that these ratios can significantly distinguish participants at elevated or reduced clinical risk. Such risk values may be aligned with clinical diagnostic guidelines (ACMG/AMP PM1, PP2) or added to integrative prediction methods.

This threshold provides the highest effect size such that all seven genes evaluated have at least one HRR and one LRR via this set of partitions (Figure 2A, Tables S1 and S2).

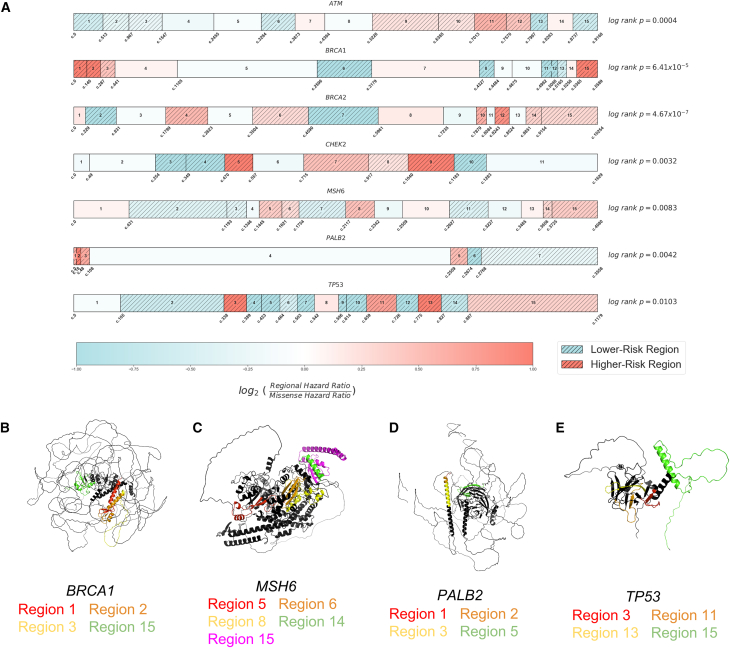

Figure 2.

Regional partitions of breast cancer-associated genes and structural distribution of higher-risk regions

(A) Regional boundary definitions are calculated using the distribution of pathogenic variant reports in ClinVar and Jenks Natural Breaks optimization, spanning the entire length of each transcript (material and methods). For each gene, higher-risk regions (HRRs) are assigned for regions with risk ratios greater than or equal to 1.15 and lower-risk regions (LRRs) for those less than or equal to 0.85. A relative risk ratio is computed as the Cox proportional hazard ratio of individuals with rare missense variants in each region divided by the Cox proportional hazard ratio for individuals with missense variants across all regions of each gene. Using breast cancer outcome data, we compare risk among individuals with rare missense variants in HRRs and LRRs (log rank p values, right).

(B–E) BRCA1, MSH6, PALB2, and TP53 higher-risk regions highlighted on AlphaFold-predicted protein structures. Despite the distance in one-dimensional nucleotide sequence, HRRs are often aligned in three-dimensional space.

Exome sequencing and variant annotation

Exome sequencing was performed for UKB participants as previously described.17 Variant allele frequencies were estimated from the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD v2.1 exomes N = 125,748). Variants were included with population maximum allele frequencies of ≤0.005 (Ensembl gnomAD plugin)22 or if not present in gnomAD. The canonical functional consequence of each variant was calculated with Variant Effect Predictor (v99) and we restrict our relative risk calculations to missense variants.23 For effect size comparison analyses, we specify predicted loss-of-function (pLOF) variants to include frameshift, stop gain, canonical splice-site, start lost, and stop lost annotation and separately analyze synonymous variants. Non-coding variants outside of essential splice sites were not considered in the analysis. Variants that are non-PASS filter quality in gnomAD were excluded, as well as any variants in low complexity regions, segmental duplications, or other regions known to be challenging for next-generation-sequencing alignment or calling.24

Selecting genes for analyses

Drawing from 34 putative cancer predisposition genes evaluated by the Breast Cancer Association Consortium,1 we retained genes with either statistically significant differences in breast cancer for individuals with rare non-synonymous variants or genes with large effect sizes (odds ratio[OR] ≥ 2), resulting in 11 genes. We removed four of these genes (BARD1, PTEN, RAD51D, RAD51C) either because of a lack of P/LP missense reports in ClinVar, which prevented derivation of regional boundaries, or a lack of individuals with variants with breast cancer in the UKB, which prevented reliable risk estimates in each region. For the remaining seven genes in this study, we restrict to P/LP ClinVar reports annotated for breast or ovarian cancer with the exception of MSH6, for which we do not restrict to breast or ovarian cancer reports.

Selecting parameters for regional boundary definitions

We selected a relative risk threshold for missense variants in each region of ±0.15, as it was the largest tested value such that all seven genes had at least one HRR and LRR. The optimization approach to define regional boundaries from pathogenic reports requires setting a number of regions a priori, which was initially set to 15 for all genes. When we could not break a gene into 15 regions reliably and with sufficient power (of participants with variants and disease cases) to perform Cox regressions without convergence errors, we selected the maximum number of regions that allowed such regressions to converge.

Participant exclusion criteria

Males were excluded from all analyses, as well as individuals with missing information regarding participant age or age of incident or prevalent cancer diagnosis. Analyses were performed separately for each gene. Individuals with multiple missense variants in the same gene were excluded from analysis. Individuals with a loss-of-function (LOF) variant were grouped in the LOF category for each gene. For each gene analysis, we removed individuals who carry LOF variants in any of the other six genes if LOF variants in that gene are known to have a significant difference in breast cancer risk as measured by log rank p value (p ≤ 0.05). To analyze the translatability of risk ratio estimates across population groups, we restricted to participants who are described by UKB field “22006” as being self-identified as having “White British” ancestry or those with similar genetic ancestry based on principal-component analysis.

Results

Regional partitions identify gene segments that confer varying levels of risk

Using this approach, we define regional boundaries and calculate relative risks for individuals with rare missense variants and identify regions that confer higher and lower risk. We find that participants with variants in HRRs have a significantly different risk of breast cancer than those with variants in LRRs in all seven breast cancer-associated genes analyzed (Figure 2A). We find that regions of elevated risk cluster closely in three-dimensional space in several genes despite substantial distance in the one-dimensional transcript sequence. Using AlphaFold structural predictions available for five genes,25 we find multiple HRRs within BRCA1 (regions 1–3 vs. 15), MSH6 (region 8 vs. 14 and 15), PALB2 (regions 1–3 vs. 5), and TP53 (region 3 vs. 11 and 13) in close three-dimensional proximity but far apart in the nucleotide sequence (Figures 2B–2D). HRRs in CHEK2 were adjacent in the protein core and were also adjacent in one dimensional space (Figure S1).

Regional information improves clinical risk prediction

Consistent with findings from a large meta-analysis examining breast cancer incidence,1 we find that rare missense variants do not always confer a significantly increased risk of breast cancer. Only two of the seven genes confer an increased risk at the gene level for participants with rare missense variants: ATM (OR = 1.17 [1.06, 1.28], log rank p = 0.011) and CHEK2 (OR = 1.37 [1.19, 1.56], log rank p = 4.93 × 10−5); other well-known genes such as BRCA2 have no significant difference in risk (OR = 0.95 [0.79, 1.12], log rank p = 0.33).

In contrast, REGatta can distinguish higher and lower risk for participants with rare missense variation. We find significant differences in breast cancer incidence among participants with missense variants in HRRs vs. LRRs in all seven genes analyzed (log rank p < 0.05) (Figure S2). Observed effect sizes for participants with HRR variants vs. LRR variants exceed those observed when comparing participants with missense variants across the entire gene vs. those without any variant in all seven genes (Figure 3A, Table S3).

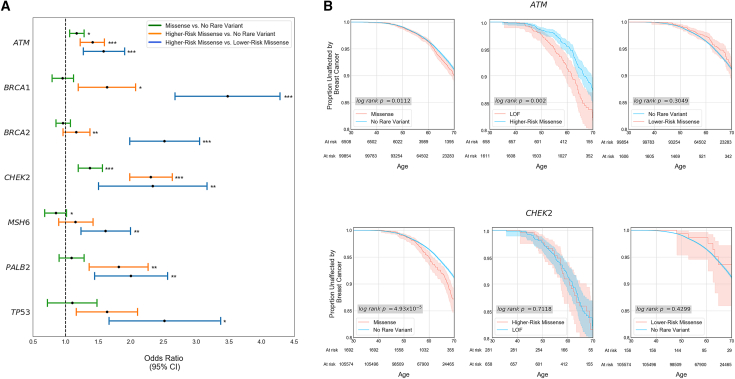

Figure 3.

Regional stratification improves specificity in elevated risk predictions

(A) Age 65 odds ratio (OR) for the seven genes partitioned into higher-risk regions (HRRs) and lower-risk regions (LRRs) for rare missense variants. At the gene level, only two genes have an increased risk at the gene level for individuals with rare missense variants when compared to individuals without rare variants (green bars: CHEK2, ATM). Partitioning each gene transcript into HRRs and LRRs results in significant differences in breast cancer incidence among individuals with rare missense variants in all seven genes examined (blue bars).

(B) Kaplan-Meier curves of breast cancer outcomes. While missense variants in aggregate in ATM and CHEK2 are significantly associated with breast cancer at the gene level, participants who carry variants in LRRs have no significant difference in risk when compared to individuals without rare variants in both genes. Additionally, those with rare missense variants in HRRs within CHEK2 have no significant difference in breast cancer incidence from those who carry a predicted loss-of-function (canonical splice-site, stop gain, or frameshift) variant.

This also extends to genes that already confer a significant risk at the gene level for participants with rare missense variants across the gene (ATM, CHEK2): REGatta can distinguish regions with higher and lower relative risk. Regions that are predicted as LRR have no significant difference in breast cancer incidence when compared with participants who carry no rare variant in ATM (OR = 0.89 [0.63, 1.15], log rank p = 0.30) or CHEK2 (OR = 0.99 [0.22, 1.75], log rank p = 0.43). Importantly this distinguishes regions where rare missense variants are unlikely to substantially increase clinical risk in genes where they generally confer significantly increased risk (Figure 3B). Further, in CHEK2, we find no significant difference in breast cancer incidence among participants with HRR missense variants and pLOF variants (OR = 0.95 [0.56, 1.34], log rank p = 0.71) (Figure 3B), emphasizing the utility of this approach in identifying missense variation with large estimated functional impacts.

Separately, we evaluated the enrichment of P/LP variants in HRRs vs. LRRs to determine whether the risk ratios derived from UKB clinical data align with the locations of previously identified pathogenic variation. We find an enrichment of 2.3× more sites with P/LP reports in HRRs vs. LRRs (Table S4).

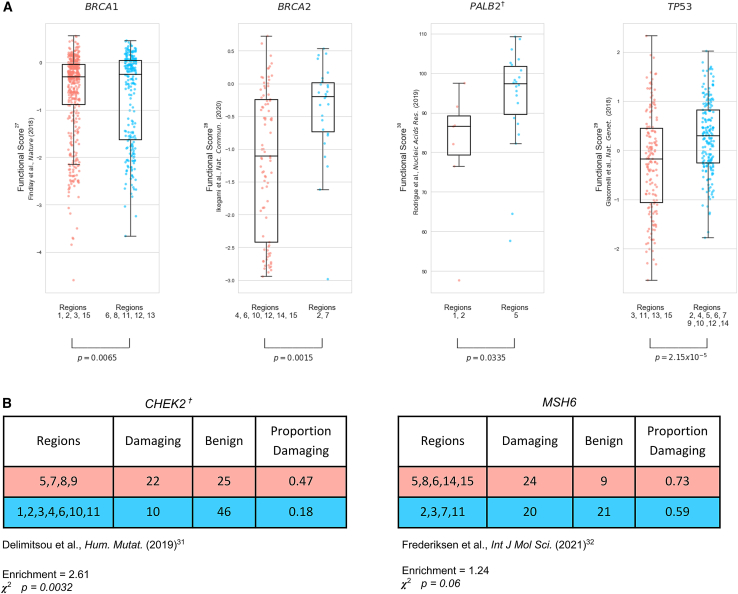

Validation of regional risk assessments with functional assay data

Measurements from well-established functional assays may be considered strong evidence of pathogenicity in the clinical variant assessment process (PS3).26 We make use of experimental evidence from high-throughput variant installation assays as an orthogonal source of validation for our regional risk assessments.27,28,29,30,31,32 For the four genes where functional impact is reported on a continuous scale, we find significant differences in assay measurements between variants in HRRs vs. LRRs (two-sided Kolmogorov–Smirnov p < 0.05, Figure 4A). In two genes where functional impact is reported dichotomously (either damaging or neutral), we find a statistically significant difference in CHEK2 HRR vs. LRR reports (enrichment = 2.61, ꭓ2 p = 0.003) and an increased but non-significant effect size in MSH6 HRR vs. LRR reports (enrichment = 1.24, ꭓ2 p = 0.06, Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Validation of regional assignments using variant functional assays

(A)When comparing functional estimates of variant impact from high-throughput experimental assays with assigned higher-risk regions (HRRs) and lower-risk regions (LRRs), we find significant differences between functional assay values in each region type. Scatterplots are shown for datasets where functional values are reported on a continuous scale.

(B) Tables shown for datasets where functional impact is assessed on a binary damaging/benign scale.

✝ Gene parameters reported differently than those reported in Figure 2. CHEK2 reported at 11 breaks, 0.05 difference. PALB2 reported at five breaks, 0.15 difference.

Comparison to protein domains and other methods to differentiate risk in regions

We compare alternative approaches to stratify risk in genic regions, starting with annotated protein domains (Pfam).33 In most genes, variants collectively within the protein domains confer no significant difference in breast cancer risk when compared to variants outside of protein domains (Table S5). Notably in MSH6, variants within any domain confer elevated but non-significant risk (OR = 1.36 [1.01, 1.72], log rank p = 0.236). In this case, MSH6 Pfam domains substantially overlap with REGatta HRRs, comprising 75.5% of the HRR coding positions and 87.8% of participants with HRR variants (Figure S3). In comparison, our regional approach identifies a significant difference between participants with variants in HRR vs. LRR segments with a larger mean effect size (OR = 1.61 [1.23, 1.99], log rank p = 0.008).

Among the 21 domains across these genes, only three confer significantly increased risk and all three overlap considerably with our defined HRRs. Two of these domains are in MSH6 (MutS domain I 62.75% overlap, MutS domain V 54.3% overlap) and the third is the BRCA1 RING domain. The 40 amino acid RING domain confers the highest OR of any domain (OR = 5.86 [5.87, 6.86], log rank p = 9.32 × 10−7) and is located entirely in BRCA1 regions 1 and 2, the two highest-risk regions in BRCA1. We find that this elevated clinical risk appears to extend beyond the RING domain: participants with missense variants in BRCA1 regions 1 and 2 outside of the RING domain have an increased effect size when compared to participants without variants (n = 33 individuals, OR = 2.51 [1.64, 3.37], log rank p = 0.09). The ATM FAT domain is the next most significant domain by log rank p value (p = 0.056), which has complete overlap with HRRs in ATM. Participants with HRR variants outside this domain also have significantly elevated breast cancer incidence vs. those without variants (OR = 1.39 [1.15, 1.63], log rank p = 0.0039) (Figure S3, Tables S2 and S5).

Prior work has made use of the clustering of ClinVar reports to inform risk predictions for missense variants.34 We compare our method to one such method that can effectively discriminate between known pathogenic and benign variation by using this information (MutScore) and has identified non-random distributions of such variation in regions in a broad set of 559 genes with clinical associations. We apply this score to population cohort data in the seven genes analyzed, where our method can identify regions with significantly higher and lower risk, and we find no significant difference in breast cancer incidence among those in the top third vs. bottom third of MutScore values (Table S6), the thresholds used in that study. We also compare our method to previous analyses of constrained coding regions (CCRs) and find high complementarity in covered regions with REGatta.35 Very few of the segments in the genes in our analysis are under strong purifying selection as estimated by CCRs, with only 0.49% falling at or above the 95th percentile and 2.54% of base pairs ≥ 90th percentile in the seven breast cancer-associated genes we examine, and no base pairs above the 95th percentile in either LRRs or HRRs in all seven genes (Table S7).

Sensitivity analysis for optimization of parameters by gene

We assess whether the parameter space for numbers of genic regions and effect size thresholds may be optimized per gene rather than using a fixed value of ±0.15 for HRR/LRR and a fixed (or maximum) number of regions. Different parameter values yield models with more significant associations in certain genes, as measured by log rank p value (Figure S4). We also find that all seven genes have at least one significant result by Benjamini-Hochberg correction (⍺ = 0.01) controlling for combinations of parameters (Table S2), demonstrating the robustness of this approach to choice of model parameters. We also identify significant differences in variant functional scores under a variety of region and risk threshold parameter configurations (Table S8).

Somatic variation rates in breast tumors in higher- and lower-risk regions

We next sought to evaluate whether our regions putatively enriched or depleted in germline variation have similar correlations in somatic variation, mindful that such comparisons may be challenged by rates of somatic variation, ascertainment of somatic variation, or clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential. We examine rates of somatic variation in breast tumor samples obtained from COSMIC36 in the genes we partitioned. We find no consistent trend in genetic variation rates in HRRs vs. LRRs, which may be related to the broad range of somatic variants by gene (ranging from a low 0.0097 somatic variants per nucleotide position in MSH6 HRRs to a high 0.34 somatic variants per nucleotide position in TP53 HRRs). We observe elevated rates of variation in four of seven genes, but these are not significantly different in any consistent manner (Table S9).

Evaluating how population inclusion criteria affect regional risk estimates

We assess whether restricting to a single population group within the UK Biobank cohort may affect regional risk estimates. Given that the number of participants with rare missense variants in each region may be very low in smaller population groups within the UK Biobank, we would be underpowered to make estimates in single population groups. Instead, we assessed whether restricting to only individuals of self-described and genetically similar “White British” ancestry has significantly different regional risk values when compared to our prior whole-cohort estimates. We find that regional risk estimates derived from the restricted ancestry group are highly correlated with those generated from the entire cohort (Pearson r = 0.77, p value < 1 × 10−16, Table S10).

Evaluating how selection of regional boundaries affects regional risk estimates

We next evaluate whether the choice of regional boundaries specified with Jenks natural breaks optimization is superior to randomly assigning boundaries. We had previously evaluated a variety of numbers of regions per gene, described in Figure 2A. In this evaluation, we maintain the same numbers and sizes of regions per gene and randomly re-sort each set of regions within the gene. We find that our breakpoints provide better model fit (as measured by log likelihood) than the shuffled regions in 5/7 genes, with notably strong differences in BRCA1 (binomial p = 0.029), BRCA2 (binomial p = 0.0065), and CHEK2 (binomial p = 0.055).

Extending REGatta to additional genes and phenotypes

We next extend REGatta to evaluate additional phenotypes and genes, including myocardial infarction (APOB, LDLR, and PCSK9) and Lynch syndrome (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2). Together with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (BRCA1, BRCA2), these three phenotypes and gene sets are designated as having sufficient evidence for population health screening by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention37 and clinical actionability by the ACMG.16 We find at least one HRR and LRR in each of these genes (Figure S5). There are significant differences in CAD incidence for participants with LDLR (log rank p = 5.91 × 10−5) and PCSK9 (log rank p = 0.0064) variants (Tables S11–S13) and significant differences in colorectal cancer incidence for MSH2 (log rank p = 0.0035) and MSH6 (log rank p = 0.001) (Tables S14–S16).

These regions align with prior clinical evidence knowledge. These include APOB region 9, which is small but has a very high relative risk and contains six of the 15 known P/LP missense variants in ClinVar. There are similarly large regions of some genes that are estimated to confer significantly lower risk, including regions 9–14 of MSH2. Conversely, almost all genes include at least one region that is estimated to confer a very high relative risk.

Discussion

Germline risk assessment for cancer syndromes is a major application area of precision medicine.38 Population sequencing cohorts have sufficiently expanded to identify pathogenic variants associated with clinical outcomes.39 However, it is still challenging to estimate the clinical risk rare missense variants generally confer given limited numbers of observations of each variant and many with smaller effect sizes. We approach this problem by measuring the clinical impact of missense variation within predefined regions from a large national biobank, which provides a uniform assessment of clinical risk.

This provides an attractive alternative to estimating the strength of purifying selection in regions from patterns of variation present in the general population. While methods to assess selective constraint can be a powerful predictor of pathogenicity and can be sensitive in regions under strong selection, they can be limited in resolution for missense variation for genes under weaker selection as a result of stochastic effects of drift. Alternative regional boundaries, such as protein domains, may be limited in their applicability because of small size or low numbers of individuals with variants, potentially leading to overdispersed estimates of effect, and may also miss putatively damaging variation outside of known protein domains. Finally, methods that provide estimates of functional effects via the relative abundance of pathogenic and/or neutral variation may provide biased estimates of functional effect, as they are not derived from neutrally ascertained populations. For example, the lack of known pathogenic variant reports has been used to argue that variants within certain genic regions are unlikely to be pathogenic, including a large “cold spot” within exon 11 of BRCA2.40 This conflicts with HRRs identified by REGatta in BRCA2, where regions 4 and 6 fall within a “cold spot” encompassing exon 11 and confer significantly increased risk.

The estimates of effect size that we have produced may serve as a useful prior for population-level risk, which may be useful in diagnostic variant assessment. The ACMG/AMP sequence variant interpretation guidelines consider many sources of evidence in favor of pathogenicity, including computational predictions of variant impact (PP3), presence in a known protein domain (PM1), experimental assays of functional impact (PS3), or absence in population databases (PS4), which may overlap with the evidence defined by REGatta. This approach makes use of newly abundant population data linked with clinical outcomes to infer which regions may be associated with elevated clinical risk. Given that this approach may be informed by more than one of the interpretation criteria, this information should be weighed carefully in variant interpretation.

Limitations of this work include the generalizability of these estimates in populations beyond those highly represented in the UKB, which may bias estimates of effect size. In populations other than those most highly represented in the UKB, there are insufficient numbers of participants with rare missense variants within each region to make robust comparisons of relative risk estimates across populations. Though we are currently limited by a small set of genes, these are some of the most commonly screened genes in the diagnostic setting associated with predispositional cancer risk.41 Given that we are making estimates from germline variation, it is worth noting that germline sequencing may uncover somatic variants associated with clonal hematopoiesis (CH), a process that occurs more frequently in older individuals. These putatively somatic variants arising from this process have been shown to be pathogenic.42 These variants may be filtered by variant allelic fraction, but it may be imperfect to effectively differentiate between somatic and germline variants in older individuals. Regions that are considered high risk and low risk are ultimately dependent on the underlying distributions of participants with variants and cases. Given that there are often strong enrichments of cases, we believe it is reasonable that other methods of creating partitions could similarly be helpful at separating HRRs and LRRs and this may be particularly helpful for phenotypes where there are not yet established pathogenic variants in ClinVar. Using other methods, however, would miss certain variation hotspots that our method captures (e.g., regions 1–3 of PALB2 for breast cancer and region 9 of APOB for coronary artery disease).

Future work includes integrating these regional risk ratios with computational or experimental predictions of functional effect at the variant level, potentially in concert with individual-level risk factors (e.g., family history, lifestyle and behavioral risk factors, and polygenic risk scores).43 Additional studies may also assess the actionability of these risk assessments as they may help optimize choice of therapy (e.g., PARP inhibitors) in individuals with BRCA1 or BRCA2 variants. Additional work should include expansion to additional genes and phenotypes with strong associations for rare coding variation.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the UK Biobank and its participants who provided biological samples and data for this analysis, performed under UK Biobank application #41250 and Mass General Brigham IRB protocol 2020P002093. We gratefully acknowledge funding from NIH R01HG010372 (J.D.F. and C.A.C.) from the National Human Genome Research Institute and helpful advice from Drs. Peter Kraft, Matthew Lebo, Natasha Strande, Shamil Sunyaev, Vineel Bhat, and Tian Yu.

Author contributions

Manuscript: J.D.F., C.A.C. Data generation: J.D.F. Statistical analysis: J.D.F., C.A.C. Model design and creation: J.D.F., C.A.C.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: May 25, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.05.003.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

Code used for all analyses and all figure creation is available at https://github.com/cassalab/regatta. The publicly available data underlying these analyses (Pfam domains, ClinVar, MutScore, functional data, and AlphaFold structural predictions) are available in annotated files in the repository as well.

References

- 1.Breast Cancer Association Consortium. Dorling L., Carvalho S., Allen J., González-Neira A., Luccarini C., Wahlström C., Pooley K.A., Parsons M.T., Fortuno C., Wang Q., et al. Breast Cancer Risk Genes - Association Analysis in More than 113,000 Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:428–439. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1913948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samadder N.J., Riegert-Johnson D., Boardman L., Rhodes D., Wick M., Okuno S., Kunze K.L., Golafshar M., Uson P.L.S., Jr., Mountjoy L., et al. Comparison of Universal Genetic Testing vs Guideline-Directed Targeted Testing for Patients With Hereditary Cancer Syndrome. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:230–237. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassa C.A., Tong M.Y., Jordan D.M. Large numbers of genetic variants considered to be pathogenic are common in asymptomatic individuals. Hum. Mutat. 2013;34:1216–1220. doi: 10.1002/humu.22375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forrest I.S., Chaudhary K., Vy H.M.T., Petrazzini B.O., Bafna S., Jordan D.M., Rocheleau G., Loos R.J.F., Nadkarni G.N., Cho J.H., Do R. Population-Based Penetrance of Deleterious Clinical Variants. JAMA. 2022;327:350–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.23686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samocha K.E., Kosmicki J.A., Karczewski K.J., O'Donnell-Luria A.H., Pierce-Hoffman E., MacArthur D.G., Neale B.M., Daly M.J. Regional missense constraint improves variant deleteriousness prediction. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1101/148353. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou J., Valiant G., Valiant P., Karczewski K., Chan S.O., Samocha K., Lek M., Sunyaev S., Daly M., MacArthur D.G. Quantifying unobserved protein-coding variants in human populations provides a roadmap for large-scale sequencing projects. Nat. Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicks M., Bartha I., Di Iulio J., Venter J.C., Telenti A. Functional characterization of 3D protein structures informed by human genetic diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:8960–8965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820813116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li B., Roden D.M., Capra J.A. The 3D mutational constraint on amino acid sites in the human proteome. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:3273. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30936-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motelow J.E., Povysil G., Dhindsa R.S., Stanley K.E., Allen A.S., Feng Y.C.A., Howrigan D.P., Abbott L.E., Tashman K., Cerrato F., et al. Sub-genic intolerance, ClinVar, and the epilepsies: A whole-exome sequencing study of 29,165 individuals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021;108:965–982. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper G.M., Stone E.A., Asimenos G., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Green E.D., Batzoglou S., Sidow A. Distribution and intensity of constraint in mammalian genomic sequence. Genome Res. 2005;15:901–913. doi: 10.1101/gr.3577405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livesey B.J., Marsh J.A. The properties of human disease mutations at protein interfaces. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iqbal S., Pérez-Palma E., Jespersen J.B., May P., Hoksza D., Heyne H.O., Ahmed S.S., Rifat Z.T., Rahman M.S., Lage K., et al. Comprehensive characterization of amino acid positions in protein structures reveals molecular effect of missense variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:28201–28211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002660117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pérez-Palma E., May P., Iqbal S., Niestroj L.M., Du J., Heyne H.O., Castrillon J.A., O’Donnell-Luria A., Nürnberg P., Palotie A., et al. Identification of pathogenic variant enriched regions across genes and gene families. Genome Res. 2020;30:62–71. doi: 10.1101/gr.252601.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laddach A., Ng J.C.F., Fraternali F. Pathogenic missense protein variants affect different functional pathways and proteomic features than healthy population variants. PLoS Biol. 2021;19 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X., Theotokis P.I., Li N., SHaRe Investigators. Wright C.F., Samocha K.E., Whiffin N., Ware J.S. Genetic constraint at single amino acid resolution improves missense variant prioritisation and gene discovery. medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.02.16.22271023. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller D.T., Lee K., Abul-Husn N.S., Amendola L.M., Brothers K., Chung W.K., Gollob M.H., Gordon A.S., Harrison S.M., Hershberger R.E., et al. ACMG SF v3.1 list for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing: A policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) Genet. Med. 2022;24:1407–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2022.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bycroft C., Freeman C., Petkova D., Band G., Elliott L.T., Sharp K., Motyer A., Vukcevic D., Delaneau O., O’Connell J., et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562:203–209. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel A.P., Wang M., Fahed A.C., Mason-Suares H., Brockman D., Pelletier R., Amr S., Machini K., Hawley M., Witkowski L., et al. Association of rare pathogenic DNA variants for familial hypercholesterolemia, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, and lynch syndrome with disease risk in adults according to family history. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landrum M.J., Chitipiralla S., Brown G.R., Chen C., Gu B., Hart J., Hoffman D., Jang W., Kaur K., Liu C., et al. ClinVar: improvements to accessing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D835–D844. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenks G. Vol. 7. 1967. The data model concept in statistical mapping; pp. 186–190. (International Yearbook of Cartography). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox D.R. Regression models and life-tables. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B. 1972;34:187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yates A., Beal K., Keenan S., McLaren W., Pignatelli M., Ritchie G.R.S., Ruffier M., Taylor K., Vullo A., Flicek P. The ensembl REST API: ensembl data for any language. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:143–145. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLaren W., Gil L., Hunt S.E., Riat H.S., Ritchie G.R.S., Thormann A., Flicek P., Cunningham F. The ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 2016;17:122. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zook J. 2020. Genome in A Bottle - Genome Stratifications. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varadi M., Anyango S., Deshpande M., Nair S., Natassia C., Yordanova G., Yuan D., Stroe O., Wood G., Laydon A., et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:D439–D444. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., Grody W.W., Hegde M., Lyon E., Spector E., et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Findlay G.M., Boyle E.A., Hause R.J., Klein J.C., Shendure J. Saturation editing of genomic regions by multiplex homology-directed repair. Nature. 2014;513:120–123. doi: 10.1038/nature13695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikegami M., Kohsaka S., Ueno T., Momozawa Y., Inoue S., Tamura K., Shimomura A., Hosoya N., Kobayashi H., Tanaka S., Mano H. High-throughput functional evaluation of BRCA2 variants of unknown significance. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2573. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16141-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giacomelli A.O., Yang X., Lintner R.E., McFarland J.M., Duby M., Kim J., Howard T.P., Takeda D.Y., Ly S.H., Kim E., et al. Mutational processes shape the landscape of TP53 mutations in human cancer. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:1381–1387. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0204-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodrigue A., Margaillan G., Torres Gomes T., Coulombe Y., Montalban G., da Costa e Silva Carvalho S., Milano L., Ducy M., De-Gregoriis G., Dellaire G., et al. A global functional analysis of missense mutations reveals two major hotspots in the PALB2 tumor suppressor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:10662–10677. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delimitsou A., Fostira F., Kalfakakou D., Apostolou P., Konstantopoulou I., Kroupis C., Papavassiliou A.G., Kleibl Z., Stratikos E., Voutsinas G.E., Yannoukakos D. Functional characterization of CHEK2 variants in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae system. Hum. Mutat. 2019;40:631–648. doi: 10.1002/humu.23728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frederiksen J.H., Jensen S.B., Tümer Z., Hansen T. v O. Classification of MSH6 variants of uncertain significance using functional assays. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:8627. doi: 10.3390/ijms22168627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mistry J., Chuguransky S., Williams L., Qureshi M., Salazar G.A., Sonnhammer E.L.L., Tosatto S.C.E., Paladin L., Raj S., Richardson L.J., et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D412–D419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quinodoz M., Peter V.G., Cisarova K., Royer-Bertrand B., Stenson P.D., Cooper D.N., Unger S., Superti-Furga A., Rivolta C. Analysis of missense variants in the human genome reveals widespread gene-specific clustering and improves prediction of pathogenicity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2022;109:457–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Havrilla J.M., Pedersen B.S., Layer R.M., Quinlan A.R. A map of constrained coding regions in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:88–95. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0294-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tate J.G., Bamford S., Jubb H.C., Sondka Z., Beare D.M., Bindal N., Boutselakis H., Cole C.G., Creatore C., Dawson E., et al. COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D941–D947. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Office of Science (OS) Office of Genomics and Precision Public Health . 2023. Tier 1 genomics applications and their importance to public health.https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/implementation/toolkit/tier1.htm [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green E.D., Gunter C., Biesecker L.G., Di Francesco V., Easter C.L., Feingold E.A., Felsenfeld A.L., Kaufman D.J., Ostrander E.A., Pavan W.J., et al. Strategic vision for improving human health at The Forefront of Genomics. Nature. 2020;586:683–692. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Backman J.D., Li A.H., Marcketta A., Sun D., Mbatchou J., Kessler M.D., Benner C., Liu D., Locke A.E., Balasubramanian S., et al. Exome sequencing and analysis of 454,787 UK Biobank participants. Nature. 2021;599:628–634. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04103-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dines J.N., Shirts B.H., Slavin T.P., Walsh T., King M.C., Fowler D.M., Pritchard C.C. Systematic misclassification of missense variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 “coldspots. Genet. Med. 2020;22:825–830. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0740-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Fuchs H.E., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2022;72:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fortuno C., McGoldrick K., Pesaran T., Dolinsky J., Hoang L., Weitzel J.N., Beshay V., San Leong H., James P.A., Spurdle A.B. Suspected clonal hematopoiesis as a natural functional assay of TP53 germline variant pathogenicity. Genet. Med. 2022;24:673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2021.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fife J.D., Tran T., Bernatchez J.R., Shepard K.E., Koch C., Patel A.P., Fahed A.C., Krishnamurthy S., Center R.G., Collaboration D., et al. A framework for integrated clinical risk assessment using population sequencing data. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.08.12.21261563. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Code used for all analyses and all figure creation is available at https://github.com/cassalab/regatta. The publicly available data underlying these analyses (Pfam domains, ClinVar, MutScore, functional data, and AlphaFold structural predictions) are available in annotated files in the repository as well.