Abstract

This randomized crossover trial evaluates the cardiopulmonary effects of extended use of the N95 mask during daily life.

Introduction

Face masks have been proven effective in reducing the transmission of COVID-19.1 As airborne diseases continue to emerge, mask use is still suggested in public and work spaces as a precautionary measure. In China, mask use remains a highly adopted practice in everyday life.2 However, studies on the adverse effects of wearing masks yielded inconsistent conclusions due to short duration of intervention.3,4,5 Given that the N95 mask offers the highest level of protection against viruses such as COVID-19, we systematically evaluated the effects of extended use of the N95 mask during daily life.

Methods

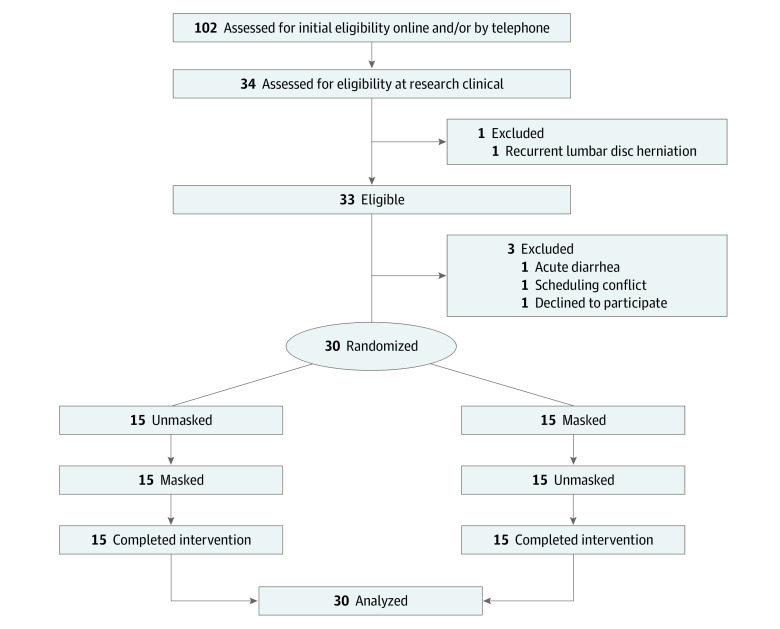

This randomized clinical trial included 30 healthy participants between March 7 and August 1, 2022, in Shanghai, China. The trial protocol (Supplement 1) was approved by the review board of Ruijin Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiaotong University, and all participants provided written informed consent. This study followed the CONSORT reporting guideline (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study Flowchart.

The study was conducted in a metabolic chamber to strictly control daily calorie intake and physical activity levels. With the use of stratified randomization, participants were randomly assigned to receive interventions with and without the N95 mask (9132; 3M) for 14 hours (8:00 to 22:00), during which they exercised for 30 minutes in the morning and afternoon using an ergometer at 40% (light intensity) and 20% (very light intensity) of their maximum oxygen consumption levels, respectively. Venous blood samples were taken before and 14 hours after the intervention for blood gas and metabolite analysis (eMethods, eTable, and eFigure in Supplement 2).

A sample size of 30 participants was required, based on our preliminary data of the mean (SD) heart rate between masked (87.5 [3.4] beats/min) and unmasked (85.7 [2.9] beats/min) conditions and to achieve 85% power and a significance level of .05. Analysis was performed on a per-protocol basis. Differences were estimated using a linear mixed-effects model. Where significant, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests were performed. Statistical tests were 2-sided. Statistical analyses were conducted using R, version 4.02 (R Group for Statistical Computing).

Results

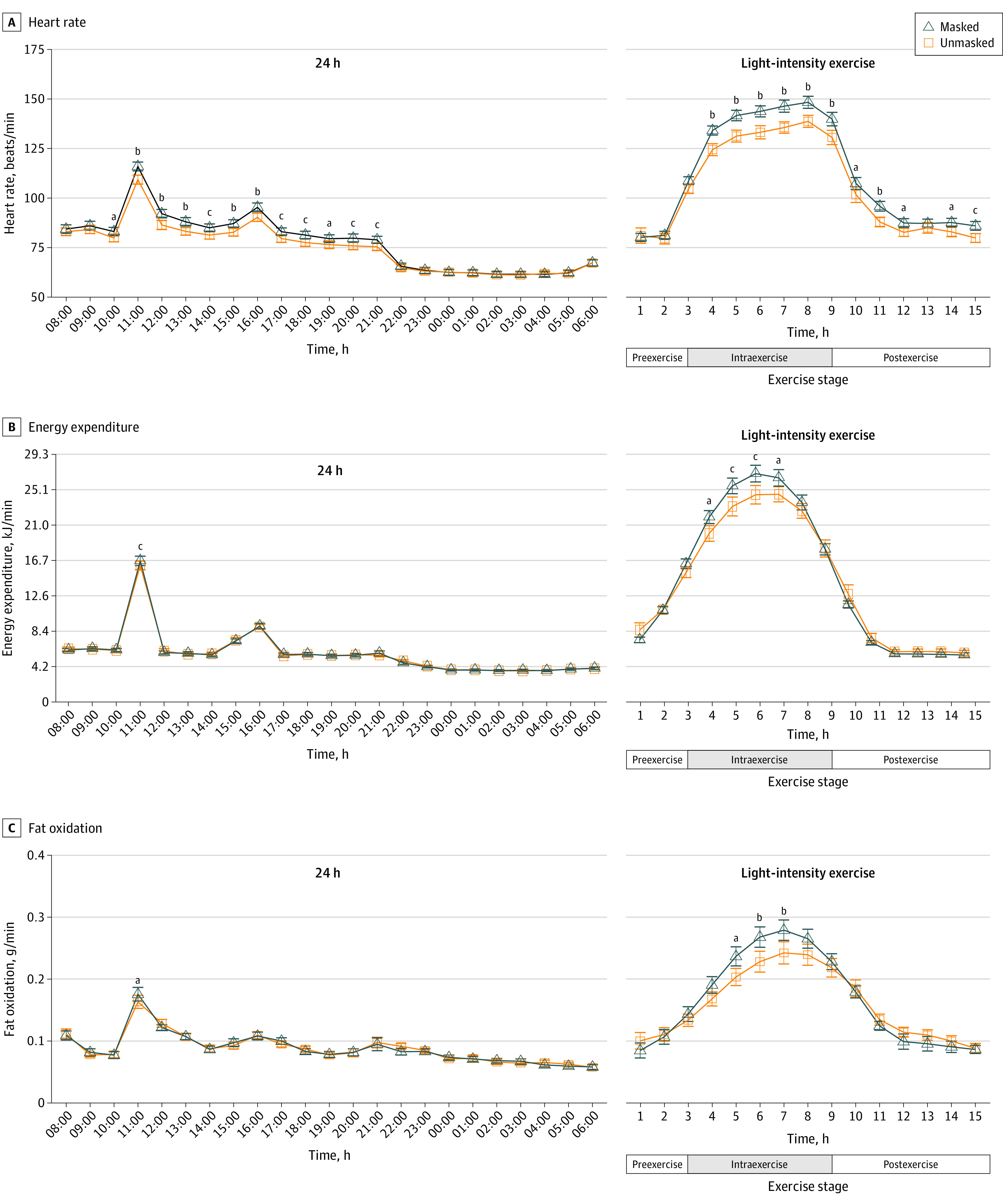

Thirty randomized participants (mean [SD] age, 26.1 [2.9] years; 15 women [50%]) completed the study. Wearing the N95 mask resulted in reduced respiration rate and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry (Spo2) within 1 hour, with elevated heart rate (mean change, 3.8 beats/min [95% CI, 2.6-5.1 beats/min]) 2 hours later until mask off at 22:00. During the light-intensity exercise at 11:00, mask-induced cardiopulmonary stress was further increased, as heart rate (mean change, 7.8 beats/min [95% CI, 5.3-10.2 beats/min]) and blood pressure (systolic: mean change, 6.1 mm Hg [95% CI, 0.6-11.5 mm Hg]; diastolic: mean change, 5.0 mm Hg [95% CI, 0.3-9.6 mm Hg]) increased, while respiration rate (mean change, −4.3 breaths/min [95% CI, −6.4 to 2.3 breaths/min]) and Spo2 (mean change, −0.66% [95% CI, −1.0% to 0.3%]) decreased. Energy expenditure (mean change, 0.5 kJ [95% CI, 0.2-0.8] kJ) and fat oxidation (mean change, 0.01 g/min [95% CI, −0.01 to 0.03 g/min]) were elevated at 11:00. After the 14-hour masked intervention, venous blood pH decreased, and calculated arterial pH showed a decreasing trend. Metanephrine and normetanephrine levels were increased. Participants also reported increased overall discomfort with the N95 mask (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effects of Wearing an N95 Mask on Physiological and Biochemical Parameters.

Parameters over 24 hours and light-intensity exercise were compared between unmasked and masked conditions.

aP < .05.

bP < .001.

cP < .01.

Discussion

The findings contribute to existing literature by demonstrating that wearing the N95 mask for 14 hours significantly affected the physiological, biochemical, and perception parameters.4,5 The effect was primarily initiated by increased respiratory resistance and subsequent decreased blood oxygen and pH, which contributed to sympathoadrenal system activation and epinephrine as well as norepinephrine secretion elevation. The extra hormones elicited a compensatory increase in heart rate and blood pressure. Although healthy individuals can compensate for this cardiopulmonary overload, other populations, such as elderly individuals, children, and those with cardiopulmonary diseases, may experience compromised compensation. Chronic cardiopulmonary stress may also increase cardiovascular diseases and overall mortality.6 However, the study was limited to only 30 young healthy participants in a laboratory setting; further investigation is needed to explore the effects of different masks on various populations in clinical settings.

Trial Protocol

eMethods.

eFigure. Study Design

eTable. Basal Characteristics of Participants

eReference.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Quigley A, Wang Q, MacIntyre CR. Non-pharmaceutical interventions during the roll out of COVID-19 vaccines. BMJ. 2021;375(2314):n2314. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng B, Zhu W, Pan J, Wang W. Patterns of human social contact and mask wearing in high-risk groups in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2022;11(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s40249-022-00988-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan NC, Li K, Hirsh J. Peripheral oxygen saturation in older persons wearing nonmedical face masks in community settings. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2323-2324. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engeroff T, Groneberg DA, Niederer D. The impact of ubiquitous face masks and filtering face piece application during rest, work and exercise on gas exchange, pulmonary function and physical performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Med Open. 2021;7(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s40798-021-00388-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopkins SR, Dominelli PB, Davis CK, et al. Face masks and the cardiorespiratory response to physical activity in health and disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(3):399-407. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202008-990CME [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caetano J, Delgado Alves J. Heart rate and cardiovascular protection. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26(4):217-222. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods.

eFigure. Study Design

eTable. Basal Characteristics of Participants

eReference.

Data Sharing Statement