Abstract

Enthusiasm for long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) is growing among donors and NGOs throughout the global reproductive health field. There is an emerging concern, however, that the push to insert these methods has not been accompanied by a commensurate push for access to method removal. We use data from 17 focus group discussions with women of reproductive age in an anonymized African setting to understand how users approach providers to request method removal, and how they understand whether or not such a request will be granted. Focus group participants described how providers took on a gatekeeping role to removal services, adjudicating which requests for LARC removal they deemed legitimate enough to be granted. Participants reported that providers often did not consider a simple desire to discontinue the method to be a good enough reason to remove LARC, nor the experience of painful side-effects. Respondents discussed the deployment of what we call legitimating practices, in which they marshalled social support, medical evidence, and other resources to convince providers that their request for removal was indeed serious enough to be honored. This analysis examines the starkly gendered nature of contraceptive coercion, in which women are expected to bear the brunt of contraceptive side-effects, while men are expected to tolerate no inconvenience at all, even vicarious. This evidence of contraceptive coercion and medical misogyny demonstrates the need to center contraceptive autonomy not only at the time of method provision, but at the time of desired discontinuation as well.

Keywords: Sexual and reproductive health and rights, Global health, Sub-Saharan Africa, Implant removal, Contraceptive coercion, Contraceptive autonomy

1. Introduction

Global family planning practitioners have expressed considerable enthusiasm about the potential of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) in recent years. Advocates and researchers in the global family planning community have praised LARC for its “many positive method characteristics,” including low failure rates, extended duration of use, suitability for all reproductive intentions, and ease of provision (Jacobstein, 2018; Secura et al., 2010; Stanback et al., 2015). There has been such great enthusiasm for LARC that many programs in both the Global North and Global South have adopted a “LARC-first” approach to contraceptive service provision in which shorter-acting methods are presented to clients last or sometimes not at all (Brandi & Fuentes, 2020; Gomez et al., 2014; Secura et al., 2010; Senderowicz et al., 2021). Enthusiasm for LARC has grown even stronger during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics suggesting, for example, that postpartum LARC could be “the solution” to “the negative impact of COVID-19 on contraception and sexual and reproductive health” (Makins et al., 2020).

In response to this enthusiasm, however, some scholars have expressed concern that the emphasis on LARC may translate into pressure among family planning clients to adopt a method they do not fully understand or want (Hendrixson, 2018; Howett et al., 2019). The provider-dependent nature of the two methods of LARC (the subdermal contraceptive implant and the intrauterine device) means that a provider is necessary not just for method insertion, but for removal as well. This provider dependency has led to concerns that LARC users may be particularly susceptible to contraceptive coercion. Drawing from Senderowicz, 2019, we define contraceptive coercion here as any action – subtle or overt, structural or interpersonal, upward or downward – that limits a person’s autonomous exercise of their contraceptive desires, including both method adoption and discontinuation. Affirming the importance of discontinuation, the World Health Organization and other professional medical associations have characterized LARC removal upon user request as an essential element of quality of care and of person-centered family planning (ACOG, 2022; World Health Organization and WHO, 2014).

Previous research has conceptualized the provider-dependent nature of LARC removal as creating a protracted timeline over which contraceptive coercion can occur, extending well past the time of initial method provision (Senderowicz, 2019). Feminist scholars have documented the ways that IUDs were used as tool of protracted reproductive coercion in China during the years when the “One Child” policy was in place (Chen & Summerfield, 2007; Greenhalgh, 1994). More recent research is exploring how some LARC users turn to self-removal, due at least in part to “barriers to formal care” that include provider reluctance to offer removal services on request (Broussard & Becker, 2021; Gbolade, 2015; Glaser et al., 2021). Research from the United States has explored internet message boards, video repositories and other social media as sites where LARC users share information and tips for method self-removal as a way to circumvent provider reluctance to remove the method (Amico et al., 2020; Broussard & Becker, 2021; Stimmel et al., 2022).

In sub-Saharan Africa, too, reproductive health scholars have raised concern about the incommensurately small focus on LARC removal services, as compared to insertion (Callahan et al., 2020; Christofield & Lacoste, 2016; Howett et al., 2019). In 2018, Hendrixson drew an explicit connection between the focus of Global North donor-funded family planning initiatives on increasing LARC uptake with the potential for contraceptive coercion among the racialized and gendered bodies of African women. Hendrixson cites the “implant volume guarantees” that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation offered the implant manufacturer, and the “market-driven targets for expanding implant use,” as reasons for the programmatic tunnel vision that has focused some reproductive health programs so narrowly on implant use in the sub-Saharan African region (Hendrixson, 2018).

And indeed, a small but growing body of evidence from around the region is showing contraceptive coercion at the time of desired implant discontinuation (Britton et al., 2021; Senderowicz, 2019; Senderowicz et al., 2021; Utaile et al., 2020; Yirgu et al., 2020). These studies have found that a programmatic emphasis on LARC can translate into biased counseling, pressure to adopt the method, and importantly, provider reluctance or outright refusal to remove the method on request. This research shows that providers may refuse to remove LARC, including in situations when the user wishes to get pregnant as well as when the labeled duration of use has completely elapsed (Utaile et al., 2020; Yirgu et al., 2020). A study from Kenya reports that some women perceived providers to be completely “unwilling to remove LARC, regardless of rationale”(Britton et al., 2021).

These studies have begun to scratch the surface of LARC removal in sub-Saharan Africa, but research on this topic is still in its early stages, with a great deal still to understand about patient-provider dynamics as well as the structural contexts in which they play out. In this analysis, we explore both the types of provider resistance that LARC users encounter when seeking removal services, as well as the legitimating practices that help users achieve the method discontinuation that they seek. We use data from 17 focus group discussions in an anonymized African setting to understand how LARC users (with a focus on subdermal implant users, as IUD use is considerably less common in this setting) approach providers to request an implant removal, and the internal logic of the decision-making processes that seem to drive whether or not such a request will be granted.

2. Material and methods

The data from this study come from a larger mixed-methods study on contraceptive coercion and reproductive autonomy. The study was carried out in a sub-Saharan African country that was a member of the Family Planning 2020 Initiative and engaged in family planning programs at the global, regional, and national levels funded and implemented by well-known global health organizations. Due to the sensitive and politicized nature of the subject matter and the findings we report, we have made the decision to anonymize the country setting and other identifying details.

2.1. Sampling and data collection

The data we use here come from the focus group discussion (FGD) phase of this study. We conducted 17 focus group discussions with 146 women of reproductive age. The focus groups each had between six and eleven participants. Focus group participants were identified and approached with the help and introduction of field supervisors and community leaders from established research platforms in those areas. Because these field supervisors have been working in these neighborhoods and towns for many years, they are well known to their respective communities, and their introduction was essential to gaining the confidence of the women we sought to interview. In addition to using their own networks, the field supervisors also used key informants from neighborhood groups and women’s associations to help further identify potential focus group participants. Due to documented health disparities in between rural and urban settings in this country, we divided our FGDs evenly between the capital city and a series of much smaller rural communities outside of the capital. The urban site is largely populated by the country’s majority ethnic group, while the rural site is largely populated by several of the country’s minority ethnic groups.

Respondents were eligible for inclusion if they were self-identified women between 15 and 49 years of age, lived within one of the neighborhoods or villages included in our study sites, and were willing and able to provide informed consent. We used key informants and local research collaborators to create our sampling strategy, which was purposive, and designed to maximize variation and obtain a diversity of opinion across a wide range of sociodemographic characteristics (Coyne, 1997). Focus groups were stratified by these sociodemographic factors: age, marital status, education, urbanicity, and religion. This stratification aimed to reduce hierarchies and promote ease of conversation among participants. The sociodemographic makeup of the focus groups is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of focus group discus.

| Focus group # | n | Religion | Site | Age Group | Education | Marital Status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | Mixed | Urban | 25–49 | Some school | Married | |

| 2 | 7 | Mixed | Urban | 25–49 | Some school | Married | |

| 3 | 10 | Mixed | Urban | 25–49 | No school | Married | |

| 4 | 10 | Mixed | Urban | 25–49 | No school | Married | |

| 5 | 8 | Mixed | Urban | 15–24 | Some school | Married | |

| 6 | 10 | Mixed | Urban | 15–24 | No school | Married | |

| 7 | 11 | Mixed | Urban | 15–24 | Some school | Unmarried | |

| 8 | 10 | Mixed | Urban | 15–24 | Some school | Unmarried | |

| 9 | 9 | Muslim | Rural | 25–49 | No school | Married | |

| 10 | 8 | Muslim | Rural | 25–49 | No school | Married | |

| 11 | 6 | Christian | Rural | 25–49 | No school | Married | |

| 12 | 6 | Christian | Rural | 25–49 | No school | Married | |

| 13 | 11 | Christian | Rural | 25–49 | No school | Married | |

| 14 | 10 | Muslim | Rural | 15–24 | Some school | Married | |

| 15 | 6 | Christian | Rural | 15–24 | No school | Unmarried | |

| 16 | 8 | Christian | Rural | 15–24 | Some school | Unmarried | |

| 17 | 6 | Muslim | Rural | 15–24 | Mixed | Unmarried | |

| Total n | 146 |

The FGD guide included questions on sociodemographic background, previous use of contraception, past experiences with family planning services providers, reproductive desires, fertility intentions, gender norms in decision-making, and views on childbearing. We pre-tested FGDs guides with key informants for clarity and content prior to use. Researchers and field supervisors closely monitored the data as it was collected for quality and made iterative changes to the tools as needed throughout the fieldwork period. In addition to asking women about their own experiences and values, the guide included additional questions and probes on experiences of friends, family members, neighbors and other community members, as previous research has found this an effective method of understanding sensitive reproductive experiences (Rossier, 2003).

Our study team trained eight experienced local women data collectors to moderate the focus groups, which were conducted in the country’s national colonial language as well as the two most common non-colonial languages according to respondent preference. Moderator training emphasized study goals, non-directive probing, and value-neutral moderation techniques. Two data collectors moderated each focus group, and no other study members were present for the discussions. Moderators took a semi-structured approach to guiding the discussions broadly around issues of autonomy, access and quality of care in family planning services, according to respondent interest. FGDs were audio-recorded, translated and transcribed verbatim with personal identifiers removed and a pseudonym assigned to all participants.

Due to the time of year (the beginning of the rainy season), many women in the rural areas were engaged in farm work from early morning to dusk. This made it challenging to find times to meet with them for the focus groups, but many women were gracious enough to share their lunch breaks with us, or otherwise make time to accommodate our request. It should be noted, though, that some of these women did express feeling pressed for time during the FGDs, causing the moderators to hasten them as much as possible without compromising study goals. All respondents were given a quantity of household soap or similar item to thank them for their time and participation.

2.2. Data analysis

Our multidisciplinary study team of US-based and local researchers used a modified grounded theory approach based on Straus and Corbin to guide our team coding approach for the analytic phase of this work (Corbin & Strauss, 2014; Giesen & Roeser, 2020). Guided by Geisen and Roeser’s team-based approach to qualitative coding, our team of four coders and one senior reviewer familiarized ourselves with the data and then used Dedoose software to free code the first few transcripts (Giesen & Roeser, 2020). Based on these free codes, we generated an initial list of codes that we began to organize under code families. Once we generated this initial list of codes, each transcript was then independently coded by two coders. We convened weekly team meetings to discuss points of agreement and disagreement between the coders, potential changes to the code list (creating new codes, collapsing codes together, etc.) as well as analytic memos, and other issues of note that had arisen during the previous week.

Given the strong body of global literature showing how disrespect and abuse from healthcare providers can be normalized (Freedman and Kruk, 2014; for example), we sought to both understand how women made their own sense of the stories they were sharing, as well as to understand these experiences in the larger context of the global family planning movement. Through our iterative process, we generated main themes and used axial coding to link concepts to one another and infer meaning from individual codes (Vollstedt & Rezat, 2019). We present these findings here with illustrative quotes.

2.3. Protection of human subjects

All relevant ethics boards reviewed and approved this study. These include the Institutional Review Board of the Office of Human Research Administration at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, USA, the national ethics committee of the country where the study took place, and the local ethics committee at one research site. Written informed consent was obtained from all adult participants (ages 20 and above). For minors (ages 15–19), written parental informed consent was obtained in addition to written assent from the minor. All participants were assigned pseudonyms and we retained no identifying respondent information.

3. Results

We divide our results into three key, interrelated findings. First, according to our participants, providers took on a gatekeeping role in relation to LARC removal, adjudicating which reasons for method removal were legitimate and important enough to be granted and which were not. Second, we found that a user’s desire to discontinue was often not considered a legitimate enough reason to convince a provider to remove the method. Finally, we found that LARC users in this context strategically deployed “legitimating practices,” marshalling social support, medical evidence, and other resources to convince providers that their request for removal was indeed serious enough to be honored.

3.1. Providers as gatekeepers of LARC discontinuation

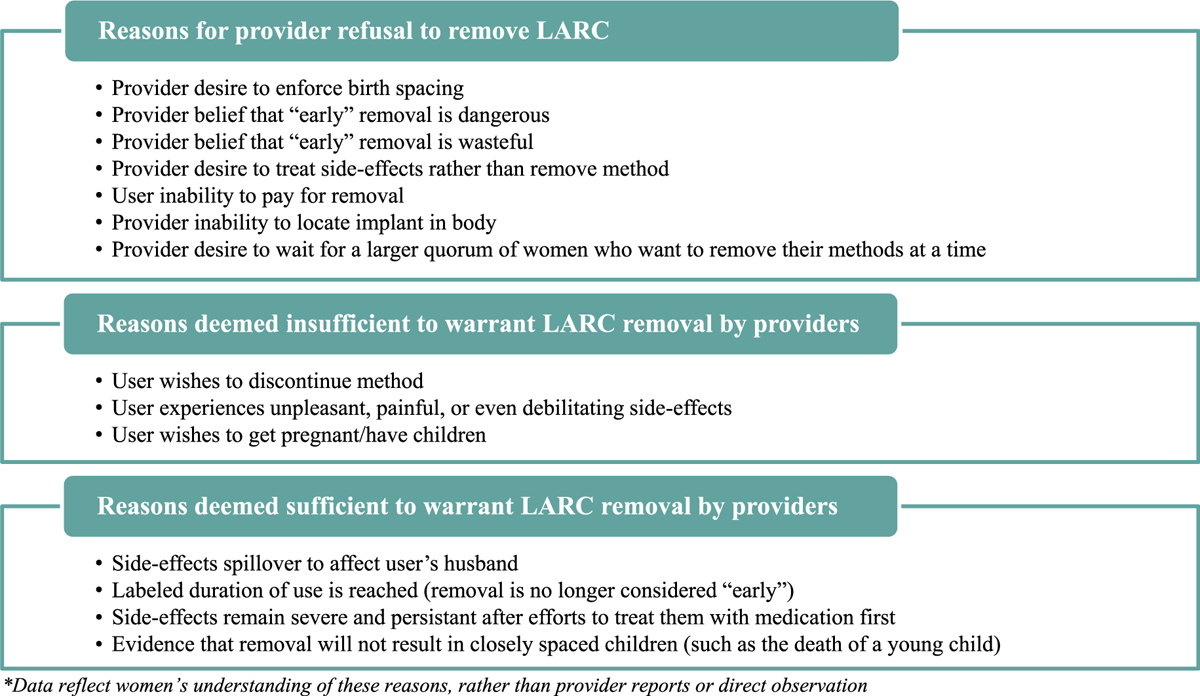

Focus group participants reported an array of stories from both their own experiences and from their social networks showing how providers assumed a gatekeeping role when it came to LARC discontinuation. Foundational to these stories was the understanding that discontinuing a method before the time of its labeled duration (5 years for the subdermal implant used in this context) was considered an “early” removal. Rather than viewing the implant as a method that can be used for up to five years but discontinued at any time prior upon user request, the default for providers in these stories was to insist on the five year maximum duration of labeled use. Deviations from this default timeline seemed to be strictly gatekept in many instances by providers. Reasons that FGD participants understood as justification for provider refusal to remove LARC included: a provider’s expression that it was medically dangerous to remove a method before the end of its labeled duration of use; a provider’s expression that it was a waste of precious resources not to use up the full efficacy of the method; a provider’s desire to medically treat method side-effects rather than removing the method; a provider’s solicitation of higher payments for removal than for insertion; and the inability to locate the implant during removal with no follow up care or referral. A summary of reasons for provider refusal to remove LARC, reasons providers deemed insufficient for removal, and rationales considered legitimate for removal is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Summary of reasons for provider refusal to remove LARC and reasons deemed in/sufficient to warrant removal.*

Maddie shared a typical story with the focus group:

Maddie: I used it [the implant] for three months and my periods stopped coming. I went to see a nurse at the clinic, and she told me that I should leave it, and that it’s normal. And I told her that I came to change [my method] and she told me no, that you cannot change and that you have to continue with it. Then I said that if that is how it works, I want my documents back and I am going to leave, because I do not ever want to use another [method again].

FGD3 (rural, Muslim, unmarried, under 25)

Like Maddie, many women in the focus groups shared that their provider’s refusal to remove their implant was not accompanied by a justification or rationale for the refusal. Examples of this type of outright refusal to remove implants were reported by respondents from across our sample, including women from a range of ethnicities, religious backgrounds and marital statuses, living in both the urban and the rural sites.

Some providers, however, did offer explanations to users for refusal to remove implants on request. Some focus group respondents, for example, shared that providers led them to believe that there were important medical contraindications to removing the implant too soon. For example, Rachel shared that:

Rachel: According to them [to providers], the contraceptive method had not yet taken effect, so if you remove it, it would be complicated [dangerous].

FGD13 (rural, married, Christian, over 25)

Rachel’s experience was echoed by Lauren, who was also told there were medical reasons for a provider’s refusal to remove implants “early.” In Lauren’s case, her provider told her that implants must be used for a minimum duration of two years:

Lauren: They said that the [implant], when you put that in there, if it’s not after two years, you can’t take it out. If it hasn’t reached two years there, they cannot remove it.

FGD5 (urban, married, Muslim, under 25)

In a different focus group, Marissa pushed back against the notion that providers could not remove the implant on request, showing that while many women were told there were medical contraindications to “early” removal, not all of them believed it. Marissa argues with her fellow focus group participants that the issue was not that providers could not remove the implants, but that they would not:

Marissa: It’s the health workers who refuse to take it out. Otherwise, you can remove it. There is nothing that makes it so you can’t remove it. Didn’t a person put it in?

FGD1 (urban, married, Catholic, over 25)

Marissa went on to explain that the reasons providers refused to remove LARC was not because of clinical reasons, but because of provider concern about the wastefulness of “early” LARC removal:

Marissa: They [the providers] say that it is a waste, they would see their product get wasted. Alternatively, it is not like there is a problem that could harm your body. They see that the medicine they prescribed you lasted two weeks instead of ten years and that is a waste.

Especially given the overall context of scarcity in this setting, where poverty often means that tires are ridden to shreds and food is eaten to the last morsel, the idea that the maximum value of the implant might not be used all the way up is a justification we heard often from respondents for provider refusals. Marissa’s quote emphasizes how providers were loath to remove LARC while it still had the ability to prevent pregnancy, since this would be tantamount to throwing away valuable medicine.

3.2. A user’s desire to discontinue is often not enough to obtain method removal

Women in our focus groups reported an array of reasons that they or others might want their implant removed, including, a desire to get pregnant and have a child, suffering from unpleasant or even debilitating side-effects, or simply their own desire for discontinuation. In spite of these reasons, respondents reported that providers often refused their requests. Indeed, a LARC user’s desire to discontinue her method for the simple reason that she did not wish to use it anymore was seldom considered a compelling enough reason for providers to honor her request, according to our respondents. Because providers sought to enforce a standard timeline based on maximum labeled duration of ef-ficacy, deviating from this timeline became something that LARC users needed to negotiate for and earn from providers.

While many women, like Maddie (above), reported that their requests to discontinue their method were refused outright with no provider justification, others reported being offered a rationale for their health worker’s refusal. Hannah, for example, told us:

Hannah: They were going to accept; but they find out that you have a child that is at a young age, they will not accept.

FGD1 (urban, married, Christian, over 25)

Hannah’s provider seemed to focus more attention on spacing out users’ births than on users’ desire for implant removal. Throughout the focus groups, respondents reported that providers made decisions about both LARC insertion and LARC removal with an eye toward ensuring lengthy interpregnancy intervals (IPIs). In this way, we found that healthcare providers seemed to be using LARC to enforce a sort of compulsory birth spacing in which they inserted LARC during the postpartum period and refused to remove it as long as the provider did not feel that a sufficient IPI had yet been reached. The most common time-frame providers had for these IPIs was between three and five years, according to our respondents, which is well beyond the six month IPI recommended by professional medical associations such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2019).

Later, Hannah told us that, although she was seeking to remove her implant due to undesirable menstrual changes, her provider instead insisted on treating her unwanted bleeding but refused to remove her implant:

Hannah: No, they will not remove it [the implant]. They will promise to give you medicine to stop your period from coming. Because if you use a contraceptive method and it makes you bleed for long periods of time. If you explain it to them, they will prescribe you some medicine that will make your bleeding stop.

With the provider emphasis on treating contraceptive side-effects with additional medicines, focus group participants reported that even debilitating side-effects were often not enough to convince providers to remove LARC “early.” We shared the following exchange with Lauren about one of her co-wives in her polygamous marriage:

Lauren: I have one of my co-wives who put in the implant but ever since she got it, she has pain around her hips all the time …

Moderator: When she had the hip pain, did she go back to get it removed?

Lauren: Yes, when she put it in and then started to feel bad, she went back for them to remove and they said that she should just leave it for at least three or four years before coming to take it out.

Moderator: So how much time later did she go back to get it taken out?

Lauren: It was before the three year mark that she wanted to take it out and they told her to leave for the three years or four years before taking it out, and that pain around the hip areas is normal … But before she took it out, she really had bad pain around her hips. She couldn’t do anything, not even wash the clothes or anything.

Moderator: But did she tell you why they [the healthcare providers] didn’t want to take it out?

Lauren: Yes, I asked her why they said they wouldn’t remove it. She told me that they said that this method is for five years, and as long as the five years haven’t come and gone, that they’re not supposed to take it out.

FGD5 (urban, married, Muslim, over 25)

In this setting, washing clothing by hand (by bending over a washtub) is an important, routine chore that women are conventionally expected to perform for themselves and for their families. That the pain was severe enough to prevent Lauren’s co-wife from performing this routine task but was not taken seriously enough by providers to warrant removal shows that even debilitating side-effects that interfere with everyday life were not always enough for providers to grant “early” requests for LARC removal. In addition to the pain and suffering that Lauren’s co-wife experienced, her inability to perform tasks as expected could have had important consequences for her relationships with other members of her household and for her social standing. That Lauren reports that the provider was “not supposed” to take the implant out prior to the five year period suggests that providers are perhaps being instructed not to remove implants “early.”

Other respondents reported financial reasons why providers would refuse to remove LARC. Allie, for example, tells us

Allie: Me, I know a woman who used the five year implant, now the five years have passed and she is still with it, that she, she did not have enough money to remove it.

FGD5 (urban, married, Muslim, over 25)

Allie’s story shows how financial barriers can result in women being trapped with an unwanted contraceptive in their body. Notably, respondents in several focus groups raised the point that providers often ask women to pay higher prices for LARC removal than they did for LARC insertion, rendering removal services inaccessible for many and raising important issues of equity.

Importantly, not all focus group participants experienced these types of barriers to LARC removal, and several respondents expressed the conviction that providers often did offer LARC removals on request and honored user preferences. Raquel shares an example of this sentiment:

Raquel: The health workers have said that if you put in a method today and then tomorrow or the day after you have problems, you can come back and they will remove it from you … They take it out without a problem if you really want to take it out. Even if you put it in today and in a week you to remove it, they take it out no problem.

FGD6 (urban, married, Catholic, under 25)

Raquel’s affirmations that providers would indeed remove LARC on request is important evidence of the diversity of experiences with implant removal, and shows that the degree of provider gatekeeping of removal services could vary substantially by case and by provider.

3.3. Legitimating LARC discontinuation

In the face of these substantial barriers to LARC discontinuation, some women were able to convince their providers to remove their LARC using practices aimed at getting the providers to consider their requests legitimate. We use the term “legitimating practices” to refer to range of acts (including developing rationales, gathering evidence, marshalling social support, and other tactics) that women used to convince healthcare providers that their request for method removal was legitimate enough to be granted.

Legitimating practices draw an understanding of provider rationales for refusing LARC removal, and the devising of strategies that might add weight to requests for LARC removal in the eyes of a gatekeeping provider. Understanding that a simple desire to discontinue the method or the experience of side-effects was often not enough to convince a provider to remove the implant “early,” especially if the provider sought to enforce compulsory birth spacing, the legitimating practices revolved around convincing the provider that a) the request for the removal was coming not only from the woman, but from a man in her life as well; b) that the removal was not, in fact, “early”; c) that the user had made a good faith effort to treat her side-effects or otherwise keep the method; and/or d) that the removal would not lead to closely spaced children (Fig. 1). Respondents saw the use of one or more of these legitimating practices as a way to increase the likelihood that a request for LARC removal would be granted.

One important factor affecting LARC removal was the way contraceptive side-effects could negatively impact men and men’s sexual desires. According to Maddie:

Maddie: Certain people, when they use it [the implant], they get dizzy. Others lose weight. Or else, like the big sister [a respectful reference to another focus group member] was saying, if your period comes and doesn’t stop. So even your husband can – if he wants to get close to you and you say ‘It’s here. It’s here. It’s here. It’s here’ [referring to a menstrual period]. It’s a problem! He’s going to say get out of here with that! [Laughs] When someone wants to get close to you and it’s ‘It’s here, it’s here.’ It [getting the method removed] is a must!..

Lily: It’s a must that they just take it out.

Maddie: You are required to take it out of me!

FGD3 (urban, married, Christian, over 25)

This exchange between Maddie and Lily was particularly striking because in countless other exchanges, participants had shared how women are expected to just live with contraceptive side-effects, to tolerate any pain they experience, and to muddle through as best they can with the implant. In this example, however, we saw that, when the unpleasant side-effects of contraceptive use bubbled over from exclusively affecting women and instead began to affect men, there was new sense of urgency and gravity. In this case, it was not the simple fact of the prolonged menstrual bleeding or its effect on the body of the woman experiencing that made removal “a must.” Instead, it was the fact that this menstrual bleeding impeded the user’s husband from access to sex with his wife that rendered removal an imperative.

It was not only the spill-over of contraceptive side-effects onto men that made men’s involvement legitimating for LARC removal. Even in the absence of side-effects, women used male family members as a way to escalate the importance of their removal requests in the eyes of providers. The utility of having a man request removal as a legitimating practice was exemplified by Sofia, who told us about how male family members could help convince providers to remove implants:

Sofia: I saw one woman who had used the implant, and when she got it inserted, she became thin, she became really thin, and people told her to go get it taken out. She went to get it taken out, but they (the nurses) refused. They say that she went to find her older brother who took her to the doctor to get it removed and free her.”

FGD1 (urban, married, Muslim, over 25)

In addition to seeking help from men to get the method removed, women expressed that they could also get their method removed if the labeled duration of use had been reached, and the request for removal was no longer considered “early.” We see an example of this from Susan, who was encouraged to get the implant after a difficult delivery:

Susan: They said to my husband to return 40 days later (after delivery) and they’ll place the rubber thing, the one for five years [referring the implant rod]. They told me I wouldn’t even have to pay [a very small sum of money]. I said okay, no problem. I went to talk to my husband and see if he agrees. Before the 40 days were even up, they sent our community health worker with a note to say that they need the women to come get a contraception method because she suffered a lot during childbirth and also the baby was big. In any case I was able to get the rubber [the implant rod]. It was worth five years, and it didn’t tired me out at all. And when the five years came to an end, I removed it.

FGD12 (rural, married, Christian, over 25)

In addition to waiting for their implants to expire, women in the focus groups shared that they might also be able to convince the provider to grant a removal request if they could show that their side-effects are really serious and that they are not simply giving up on the method without a good faith effort:

Charlotte: He [the provider] does not accept [to remove] it on the spot; he will give you medication first and if the ailment persists, he will then accept to remove it.

FGD2 (urban, married, Catholic, over 25)

A final way to legitimate implant removal that participants raised was if the provider could be convinced that the removal would not result in closely spaced children. One notable example from this comes from Hannah, who shares what happens in the case that a young child dies:

Hannah: If your child dies, the decision is between you and your husband now. If you do not want to have another child, you only have to wait the five years. On other hand, if you want to have another child, you can go get it [the implant] removed. If the health worker knows that you do not have children, they will accept to remove it without a problem.

FGD13 (rural, married, Christian, over 25)

That the decision reverts to the LARC user and her husband upon the death of a child implies that prior to that loss, the provider was a factor in that decision as well. This underscores the element of reproductive control that healthcare providers are wielding in these stories, deciding whom they think should be allowed to have children, under what circumstances, and when.

4. Discussion

These findings explore not only the ways in which access to LARC discontinuation is limited by provider reluctance to remove these methods, but also some of the legitimating practices that help women gain access to implant removal services, and the ways that women maneuver within restrictions to manifest their reproductive desires. These results add to the growing body of evidence showing how healthcare providers can view a LARC user’s own desire to discontinue as an insuf-ficiently strong rationale for removal. Users’ reports of their interactions with healthcare providers reveal that providers view their role as gatekeeping access to contraceptive discontinuation, rather than prioritizing responsiveness to user requests. As the gatekeepers of method discontinuation, then, providers must be presented with a sufficiently compelling grounds for honoring requests for contraceptive method removal. In response, our results find that women have developed an array of strategies to convince providers that their claim to method removal is strong enough.

The findings from this study indicate that the driving concern for family planning programs in this setting may not be to enable a woman to achieve her own reproductive desires, but rather, to enforce compulsory birth spacing and achieve other global family planning programmatic priorities. This relates to the connection between quantitative uptake targets and coercive family planning services that have been drawn in other analyses of contemporary global family planning and reproductive health programs (Hendrixson, 2018; Senderowicz, 2019, 2020; Senderowicz et al., 2021). These results also dovetail with an emerging body of literature that documents, from the provider perspective, how healthcare providers seek to impose their own biases and preconceptions about contraception onto their patients, especially among those from marginalized racial and ethnic backgrounds (Kramer et al., 2018; Manzer & Bell, 2021; Stevens, 2018).

The provider reluctance that women report when seeking to discontinue LARC is in direct contravention of the principles of contraceptive autonomy, and of reproductive rights and justice more broadly (Ross et al., 2017). Contraceptive autonomy is defined “as the factors that need to be in place for a person to decide for themselves what they want in regards to contraceptive use, and then to realize that decision,” broken down in the three components of informed, full, and free choice (Senderowicz, 2020). In previous work, we have explicitly identified provider reluctance to remove LARC on request as a form of contraceptive coercion, and included the right to discontinue provider-dependent methods without barriers or coercion as a key element of contraceptive autonomy (Senderowicz, 2019, 2020). This focus on the ability to discontinue LARC on demand is also highlighted in a “LARC Statement of Principles Issues” jointly by the National Women’s Health Network and the SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective. This document emphasizes that “A woman who wants her LARC removed should have her decision respected and her LARC promptly removed, even if her clinician believes that she might ultimately be happy with the device if she were to wait” (Christopherson, 2016).

While the research methods we employed do not allow us to know the gender of the providers themselves, they do allow us to note a starkly gendered divide in how removal requests are received by providers. Requests by women because they are experiencing unpleasant (sometimes severe) side-effects or simply because they no longer wish to use the LARC are often considered insufficient grounds for removal by providers. Indeed, there is considerable literature documenting the ways that women are expected to tolerate the side-effects and bear the broader social and physical costs of contraceptive use and family planning (Agadjanian, 2002; Littlejohn, 2013; Rosenthal & Lobel, 2020). In contrast, several of the “legitimating practices” that did convince providers to accede to removal requests involved men in the request. While side-effects that bother the woman often were not enough of a justification on their own, if those side-effects (such as frequent menstruation) were perceived to diminish the sexual access that the users husband had to her, this was indeed considered strong enough grounds to warrant method removal. In this way, even a mild, vicarious inconvenience to a man’s body seems to outweigh much more severe consequences to a woman’s body.

The expectation that women bear the brunt of contraceptive disadvantages, and the ways that contraception “becomes a fundamentally unbalanced and gendered responsibility” has been named “gendered compulsory birth control” by sociologist Krystale Littlejohn (Littlejohn, 2021). This finding is corroborated by a growing body of research showing how contraception is used to maintain and reinscribe existing gender norms (rather than contest or transform them) despite narratives focused on women’s empowerment, both in the Global North and the Global South (Agadjanian, 2002; James-Hawkins et al., 2019; Senderowicz et al., 2022). The incongruity of promoting LARC using the language of empowerment while depriving users the ability to discontinue use when they desire is an example of what Mann and Grzanka dubbed “agency-without-choice” in LARC promotion (Mann & Grzanka, 2018). Scholars have also highlighted the ways that using LARC to limit reproductive autonomy echo previous efforts to stratify reproduction along intersecting racial, ethnic, gendered, and geopolitical lines (Gubrium et al., 2016; Hendrixson, 2018; Senderowicz, 2019).

This research adds to a growing body of evidence exploring how LARC expands the power of healthcare providers to enact gendered reproductive governance through the bodies of users and non-users alike. Morgan and Roberts introduced the concept of reproductive governance in 2009 to refer to “the mechanisms through which different historical configurations of actors … use legislative controls, economic inducements, moral injunctions, direct coercion and ethical incitements to produce, monitor and control reproductive behaviors and practices” (Morgan & Roberts, 2012). A recent study from the southeastern United States found that “clinicians center their own contraceptive preferences and behaviors, prioritize pregnancy prevention via LARC use above other priorities patients may have, and communicate that contraceptive use is compulsory for women of reproductive age” (Mann, 2022).

Outside the United States, LARC programming has received considerably less scrutiny, but there are some data to show that a growing focus on LARC can have a deleterious effect on person-centered care, access to a broad contraceptive method mix, and other outcomes related to full, free and informed contraceptive choice (Callahan et al., 2020; Senderowicz et al., 2021). The ways that the gendered, racialized, classed, and colonial logics of global family planning programs intersect with one another to target poor women of color living in the Global South for fertility reduction measures has been particularly well-explored by critical feminist scholars over the past several decades (Bendix, 2016; Bhatia et al., 2020; Clarke, 2021; Hartmann, 1987; Kuumba, 1993; Suh, 2021). In 1999, Monica Bahati Kuumba dubbed this “simultaneous facilitat[ion of] racial inequality, class exploitation, and gender subordination” of women living in the Global South targeted by family planning programs a form of “reproductive imperialism” (Kuumba, 1999). This analysis, and the ways that global family planning still primarily target the bodies of poor women of color living in the poorest countries, provide evidence of the enduring salience of Kuumba’s analysis.

Limitations to this analysis include an exclusive focus on women’s perceptions of LARC removal, without provider perspectives or direct observations. We are unable to say whether or not providers were intending to impose their own values onto LARC users, or what types of justifications they themselves had for refusing to provide LARC removal services on request. Future work on this topic should explore not only users’ experiences, but provider and health systems perspectives as well, to better understand provider motivations. Regardless of provider motivations, the result for the LARC user seeking to discontinue their method is remains the same: they are stuck with a method they want to take out. Even in the absence of any malice, contraceptive coercion may still flourish.

The financial barriers focus group participants cited, for example, show that even in the face of provider willingness to provide removal services, women can still face structural barriers to free contraceptive choice. This adds to our understanding of “structural coercion” with results not from individual ill-will or provider-level factors, but from the broader legal, socioeconomic, and policy environment in which contraceptive services are delivered (Senderowicz, 2019). Structural coercion in reproductive health has received less attention than interpersonal coercion, but, drawing from the reproductive justice framework, an emerging body of literature (including a recent policy statement from the American Public Health Association) are beginning to emphasize the importance of structures and systems in perpetuating reproductive coercion (American Public Health Association, 2021; DeJoy, 2019; Julian et al., 2020; Morison, 2021; Nandagiri et al., 2020).

The focus group format invites participants to tell stories not only about their own experiences, but about friends, family, and neighbors as well. We do not have the ability to attribute any specific incident to any specific person, including second-hand accounts in addition to first-person experiences, but by drawing on their social networks, these focus groups discussions allow us to gain important insights into social norms and issues salient at the community level. While we primarily explore instances of provider refusal in this analysis, there was a tremendous diversity of experiences shared in the focus groups. Several women reported being able to remove their implants with little difficulty at all, while other reported struggling tremendously. Participants reported a range of provider reactions to different legitimating practices, suggesting that there is no universal experience of this type of contraceptive coercion and nor is there a one-size-fits-all approach to addressing it. Understanding the breadth, depth and nuance of these experiences is essential to finding solutions that will promote contraceptive autonomy and reproductive freedom.

5. Conclusions

This analysis adds to our understanding of contraceptive coercion, both by showing how women face coercion long after the time of method acquisition, as well as by showing some of the strategies that LARC users deploy to overcome this coercion. These results show contraceptive coercion to be a profoundly gendered phenomenon in which women’s bodies are subjected to compulsory birth spacing even in the face of substantial side-effects. Women’s requests for LARC discontinuation are routinely brushed aside or disregarded by healthcare providers, but when men experience the spillover effects of contraceptive side effects or a male relative requests LARC removal, these requests are taken more seriously. The starkly gendered nature of these results shows that there is nothing inherently emancipatory about contraception; in addition to their potential to subvert gender norms, family planning programs have the potential to reify and reinscribe medical misogyny as well.

Showing that contraceptive coercion is commonplace at the time of desired method discontinuation for women, these results call for a sweeping shift away from family planning programs that conceptualize method discontinuation as a programmatic failure. The global family planning community must shift both the mentalities and the measurement approaches that characterize method discontinuation as a negative outcome, and instead view method removal as an essential part of any rights-based family planning approach (Senderowicz, 2020). Method discontinuation on request – for any reason or no reason at all – is a key component of contraceptive autonomy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the many researchers, research assistants, field supervisors and data collectors who contributed to the data collection for this study.

Funding and role of funders

Funding for this research comes from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation (#2016–6774), the Heidelberg Institute of Global Health at the University of Heidelberg, and the anonymous family foundation that supports the University of Wisconsin Collaborative for Reproductive Equity.

Additional funding for this study came from a grant funded by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Department of Pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health (UWSMPH) through the University of Wisconsin-Madison Prevention Research Center. The University of Wisconsin-Madison Prevention Research Center is a member of the Prevention Research Centers (PRC) Program and is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cooperative agreement number 1U48DP006383. LS’s contribution was supported by a Ruth L Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32 HD049302) and Population Research Infrastructure grant (P2C HD047873). The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) awarded these grants. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of nor an endorsement by the UWSMPH Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, UWSMPH Department of Pediatrics, CDC/HHS, the NIH/NICHD, or the U.S. Government.

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

Due to the terms of our ethics approval, the qualitative data used in this analysis are protected and are not publicly available.

References

- ACOG. (2022). Patient-Centered Contraceptive Counseling (No. 1), Committee Statement https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-statement/articles/2022/02/patient-centered-contraceptive-counseling.

- Agadjanian V (2002). Men’s talk about “women’s matters” gender, communication, and contraception in urban Mozambique. Gender & Society, 16(2), 194–215. 10.1177/08912430222104903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2019). Obstetric care consensus No. 8: Interpregnancy care. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 133, E51–E72. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association. (2021). Opposing coercion in contraceptive access and care to promote reproductive health equity. No. 202110) https://www.apha.org/Policies-and-Advocacy/Public-Health-Policy-Statements/Policy-Database/2022/01/07/Opposing-Coercion-in-Contraceptive-Access-and-Care-to-Promote-Reproductive-Health-Equity.

- Amico JR, Stimmel S, Hudson S, & Gold M (2020). “$231… to pull a string!!!” American IUD users’ reasons for IUD self-removal: An analysis of internet forums. Contraception, 101(6), 393–398. 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendix D (2016). From fighting underpopulation to curbing population growth: Tracing colonial power in German development interventions in Tanzania. Postcolonial Studies, 19(1), 53–70. 10.1080/13688790.2016.1228137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia R, Sasser JS, Ojeda D, Hendrixson A, Nadimpally S, & Foley EE (2020). A feminist exploration of ‘populationism’: Engaging contemporary forms of population control. Gender, Place & Culture, 27(3), 333–350. 10.1080/0966369X.2018.1553859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandi K, & Fuentes L (2020). The history of tiered-effectiveness contraceptive counseling and the importance of patient-centered family planning care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 222, S873–S877. 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton LE, Williams CR, Onyango D, Wambua D, & Tumlinson K (2021). “When it comes to time of removal, nothing is straightforward”: A qualitative study of experiences with barriers to removal of long-acting reversible contraception in western Kenya. Contraception, 3, 100063. 10.1016/j.conx.2021.100063, 100063, X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussard K, & Becker A (2021). Self-removal of long-acting reversible contraception: A content analysis of YouTube videos. Contraception, 104(6), 654–658. 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan R, Lebetkin E, Brennan C, Kuffour E, Boateng A, Tagoe S, … Brunie A (2020). What goes in must come out: A mixed-method study of access to contraceptive implant removal services in Ghana. Global Health Science and Practice, 8(2), 220–238. 10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, & Summerfield G (2007). Gender and rural reforms in China: A case study of population control and land rights policies in northern liaoning. Feminist Economics, 13(3–4), 63–92. 10.1080/13545700701439440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christofield M, & Lacoste M (2016). Accessible contraceptive implant removal services: An essential element of quality service delivery and scale-up. Global Health Science and Practice, 4(3), 366–372. 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson S (2016). NWHN-SisterSong joint statement of principles on LARCs [WWW Document]. Natl. Women’s Heal. Netw. URL https://www.nwhn.org/nwhn-joins-statement-principles-larcs/ accessed 2.18.20.

- Clarke E (2021). Indigenous women and the risk of reproductive healthcare: Forced sterilization, genocide, and contemporary population control. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 6, 144–147. 10.1007/S41134-020-00139-9, 2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, & Strauss A (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th). SAGE publications. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne IT (1997). Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(3), 623–630. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-25-00999.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJoy G (2019). State reproductive coercion as structural violence. Columbia Social Work Review, 17(1), 36–53. 10.7916/cswr.v17i1.1827 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gbolade BA (2015). Attempted self-removal of Implanon®: A case report. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction, 4(3), 247–248. 10.1016/j.apjr.2015.06.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giesen L, & Roeser A (2020). Structuring a team-based approach to coding qualitative data. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, Article 1609406920968700. 10.1177/1609406920968700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser K, Fix M, Karlin J, & Schwarz EB (2021). Awareness of the option of IUC self-removal among US adolescents. Contraception, 104(5), 567–570. 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez AM, Fuentes L, & Allina A (2014). Women or LARC first? Reproductive autonomy and the promotion of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 46(3), 171–175. 10.1363/46e1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh S (1994). Controlling births and bodies in village China. American Ethnologist, 21(1), 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium AC, Mann ES, Borrero S, Dehlendorf C, Fields J, Geronimus AT, … Sisson G (2016). Realizing reproductive health equity needs more than Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC). American Journal of Public Health, 106(1), 18–19. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann B (1987). Reproductive rights and wrongs: The global politics of population control and contraceptive choice. New York City: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrixson A (2018). Population control in the troubled present: The ‘120 by 20’ target and implant access program: Population control in the troubled present. Development and Change, 50(3), 786–804. 10.1111/dech.12423 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howett R, Gertz AM, Kgaswanyane T, Petro G, Mokganya L, Malima S, …Morroni C (2019). Closing the gap: Ensuring access to and quality of contraceptive implant removal services is essential to rights-based contraceptive care. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 23(4), 19–26. 10.29063/ajrh2019/v23i4.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobstein R (2018). Liftoff: The blossoming of contraceptive implant use in Africa. Global Health: Science and Practice, 6(1), 17–39. 10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James-Hawkins L, Dalessandro C, & Sennott C (2019). Conflicting contraceptive norms for men: Equal responsibility versus women’s bodily autonomy. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 21(3), 263–277. 10.1080/13691058.2018.1464209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian Z, Robles D, Whetstone S, Perritt JB, Jackson AV, Hardeman RR, & Scott KA (2020). Community-informed models of perinatal and reproductive health services provision: A justice-centered paradigm toward equity among black birthing communities. Seminars in Perinatology, 44(5), Article 151267. 10.1016/J.SEMPERI.2020.151267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer RD, Higgins JA, Godecker AL, & Ehrenthal DB (2018). Racial and ethnic differences in patterns of long-acting reversible contraceptive use in the United States, 2011–2015. Contraception, 97(5), 399–404. 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuumba MB (1993). Perpetuating neo-colonialism through population control: South Africa and the United States. Africa Today, 40(3), 79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuumba M (1999). A cross-cultural race/class/gender critique of contemporary population policy: The impact of globalization. Sociological Forum, 14(3), 447–463. 10.1023/A:1021499619542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn KE (2013). It’s those pills that are ruining me”: Gender and the social meanings of hormonal contraceptive side effects. Gender & Society, 27(6), 843–863. 10.1177/0891243213504033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn KE (2021). Just get on the pill: The uneven burden of reproductive politics, just get on the pill. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Makins A, Arulkumaran S, Sheffield J, Townsend J, Hoope-Bender PT, Elliott M, … Makins A (2020). The negative impact of COVID-19 on contraception and sexual and reproductive health: Could immediate postpartum LARCs be the solution? International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 150(2), 141–143. 10.1002/ijgo.13237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann ES (2022). The power of persuasion: Normative accountability and clinicians’ practices of contraceptive counseling. SSM-Qualitative Res. Heal, 2, Article 100049. 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mann ES, & Grzanka PR (2018). Agency-without-Choice: The visual rhetorics of long-acting reversible contraception promotion. Symbolic Interaction, 41(3), 334–356. 10.1002/symb.349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manzer JL, & Bell AV (2021). We’re a little biased”: Medicine and the management of bias through the case of contraception. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 62(2), 120–135. 10.1177/00221465211003232, 00221465211003232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan LM, & Roberts EFS (2012). Reproductive governance in Latin America. Anthropology & Medicine, 19(2), 241–254. 10.1080/13648470.2012.675046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morison T (2021). Reproductive justice: A radical framework for researching sexual and reproductive issues in psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 15(6), Article e12605. 10.1111/SPC3.12605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nandagiri R, Coast E, & Strong J (2020). COVID-19 and abortion: Making structural violence visible. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 46(1), 83–89. 10.1363/46e1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L, & Lobel M (2020). Gendered racism and the sexual and reproductive health of Black and Latina Women. Ethnicity and Health, 25(3), 367–392. 10.1080/13557858.2018.1439896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L, Roberts L, Derkas E, Peoples W, & Toure PB (2017). Radical reproductive justice: Foundation, theory, practice, critique. New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, & Peipert JF (2010). The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: Reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 203(2). 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017, 115.e1–115.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senderowicz L (2019). “I was obligated to accept”: A qualitative exploration of contraceptive coercion. Social Science & Medicine, 239, Article 112531. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senderowicz L (2020). Contraceptive autonomy: Conceptions and measurement of a novel family planning indicator. Studies in Family Planning, 51(2), 161–176. 10.1111/sifp.12114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senderowicz L, Pearson E, Hackett K, Huber-Krum S, Francis J, Ulenga N, & Bärnighausen T (2021). I haven’t heard much about other methods”: Quality of care and person-centredness in a programme to promote the postpartum intrauterine device in Tanzania. BMJ Global Health, 6(6), Article e005775. 10.1136/BMJGH-2021-005775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senderowicz L, Sawadogo N, Chung S, Kolenda A, Langer A, Sie A, … Zabre P (2022). “For those that do not go to school, it’s for prostitution”: An intersectional analysis of attitudes toward contraceptive use in Burkina Faso. Population Association of America Annual Meeting. Atlanta, GA https://paa.confex.com/paa/2022/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/26629. [Google Scholar]

- Stanback J, Steiner M, Dorflinger L, Solo J, & Cates W (2015). WHO tiered-effectiveness counseling is rights-based family planning. Global Health Science and Practice, 3(3), 352–357. 10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens LM (2018). “We have to be mythbusters”: Clinician attitudes about the legitimacy of patient concerns and dissatisfaction with contraception. Social Science & Medicine, 212, 145–152. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimmel S, Hudson SV, Gold M, & Amico JR (2022). Exploring the experience of IUD self-removal in the United States through posts on internet forums. Contraception, 106, 34–38. 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh S (2021). A stalled revolution? Misoprostol and the pharmaceuticalization of reproductive health in francophone Africa. Frontiers in Sociology, 6, 21. 10.3389/fsoc.2021.590556, 590556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utaile MM, Debere MK, Nida ET, Boneya DJ, & Ergano AT (2020). A qualitative study on reasons for early removal of Implanon among users in Arba Minch town, Gamo Goffa zone, South Ethiopia: a phenomenological approach. BMC Women’s Health, 20(2), 1–7. 10.1186/s12905-019-0876-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollstedt M, & Rezat S (2019). An introduction to grounded theory with a special focus on axial coding and the coding paradigm. Compendium for Early Career Researchers in Mathematics Education, 13, 81–100. 10.1007/978-3-030-15636-7_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, WHO. (2014). Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services: Guidance and recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/102539/9789241506748_eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yirgu R, Wood SN, Karp C, Tsui A, & Moreau C (2020). “You better use the safer one… leave this one”: The role of health providers in women’s pursuit of their preferred family planning methods. BMC Women’s Health, 20, Article 170. 10.1186/s12905-020-01034-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the terms of our ethics approval, the qualitative data used in this analysis are protected and are not publicly available.