Abstract

Objectives

To compare clinical outcomes with programmed-death ligand-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma (aUC) who have vs have not undergone radical surgery (RS) or radiation therapy (RT) prior to developing metastatic disease.

Patients and Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study collecting clinicopathological, treatment and outcomes data for patients with aUC receiving ICIs across 25 institutions. We compared outcomes (observed response rate [ORR], progression-free survival [PFS], overall survival [OS]) between patients with vs without prior RS, and by type of prior locoregional treatment (RS vs RT vs no locoregional treatment). Patients with de novo advanced disease were excluded. Analysis was stratified by treatment line (first-line and second-line or greater [second-plus line]). Logistic regression was used to compare ORR, while Kaplan–Meier analysis and Cox regression were used for PFS and OS. Multivariable models were adjusted for known prognostic factors.

Results

We included 562 patients (first-line: 342 and second-plus line: 220). There was no difference in outcomes based on prior locoregional treatment among those treated with first-line ICIs. In the second-plus-line setting, prior RS was associated with higher ORR (adjusted odds ratio 2.61, 95% confidence interval [CI]1.19–5.74]), longer OS (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.61, 95% CI 0.42–0.88) and PFS (aHR 0.63, 95% CI 0.45–0.89) vs no prior RS. This association remained significant when type of prior locoregional treatment (RS and RT) was modelled separately.

Conclusion

Prior RS before developing advanced disease was associated with better outcomes in patients with aUC treated with ICIs in the second-plus-line but not in the first-line setting. While further validation is needed, our findings could have implications for prognostic estimates in clinical discussions and benchmarking for clinical trials. Limitations include the study’s retrospective nature, lack of randomization, and possible selection and confounding biases.

Keywords: bladder cancer, urinary tract neoplasms, urothelial carcinoma, immune checkpoint inhibitors, immunotherapy, outcomes, #uroonc, #utuc, #BladderCancer, #blcsm

Introduction

Bladder cancer is one of the most common malignancies worldwide and the sixth most prevalent in the USA [1]. Locoregional treatment with radical surgery (RS; cystectomy or [nephro]ureterectomy) with lymph node dissection (ideally with neoadjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy) is the most accepted treatment for non-metastatic muscle-invasive urothelial cancer [2]. However, over half of patients undergoing RS develop recurrence, with poor outcomes [3–5].

Over the last 5 years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have become an established treatment option for patients with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (advanced urothelial carcinoma [aUC]). These agents improve overall survival (OS) when given as second-line or greater (second-plus-line) treatment (post-platinum progression, based on Keynote 045 trial) or in a switch maintenance setting (based on Javelin Bladder 100 trial) [6–8]. The US Food and Drug Administration has also accelerated approvals for pembrolizumab and atezolizumab in the first-line setting for patients ineligible for cisplatin therapy who have tumours with high programmed-death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression (CPS≥10 and IC2/3, respectively) and for patients who are ineligible for platinum (cisplatin and carboplatin) therapy, based on single-arm phase II trials [8]. While ICIs have led to significantly improved outcomes in patients with aUC, response rates and progression-free survival (PFS) remain modest, and cure remains elusive, while there is a notable risk of immune-related adverse events. Therefore, clinical and molecular biomarkers are needed to help identify patients who are more likely to benefit from ICIs.

In advanced kidney cancer, retrospective studies suggest OS with ICI-based therapy was longer in patients with prior nephrectomy compared to those without [9] but prospective trials are further investigating this question (PROBE trial; NCT04510597). However, the potential impact of the presence of the primary tumour on ICI response and outcomes in aUC remains unclear. It could be hypothesized that the primary tumour may either potentially serve as a ‘neoantigen beacon’, providing a plethora of neoantigens bolstering anti-tumour immune response, or, on the contrary, may exert immunosuppressive effects, dampening response to ICIs. To address this question, we conducted a retrospective cohort study investigating the potential association between prior definitive locoregional treatment, in the form of RS or RT, response and survival with subsequent ICIs given for aUC. We hypothesized that prior RS would be associated with higher response rates and longer survival after subsequent ICI treatment for aUC.

Patients and Methods

Study Design, Patients and Data Collection

After institutional review board approval was obtained in concordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, we performed a retrospective cohort study, using a cohort [10–13] of patients from 25 institutions in the United States and Europe. Consecutive patients at each institution were identified using a combination of provider-driven and electronic health record search algorithms. Patients were included if they had been treated with ICI monotherapy for aUC with prior locoregional-only disease. All included patients with RS had undergone RS prior to development of metastatic disease.

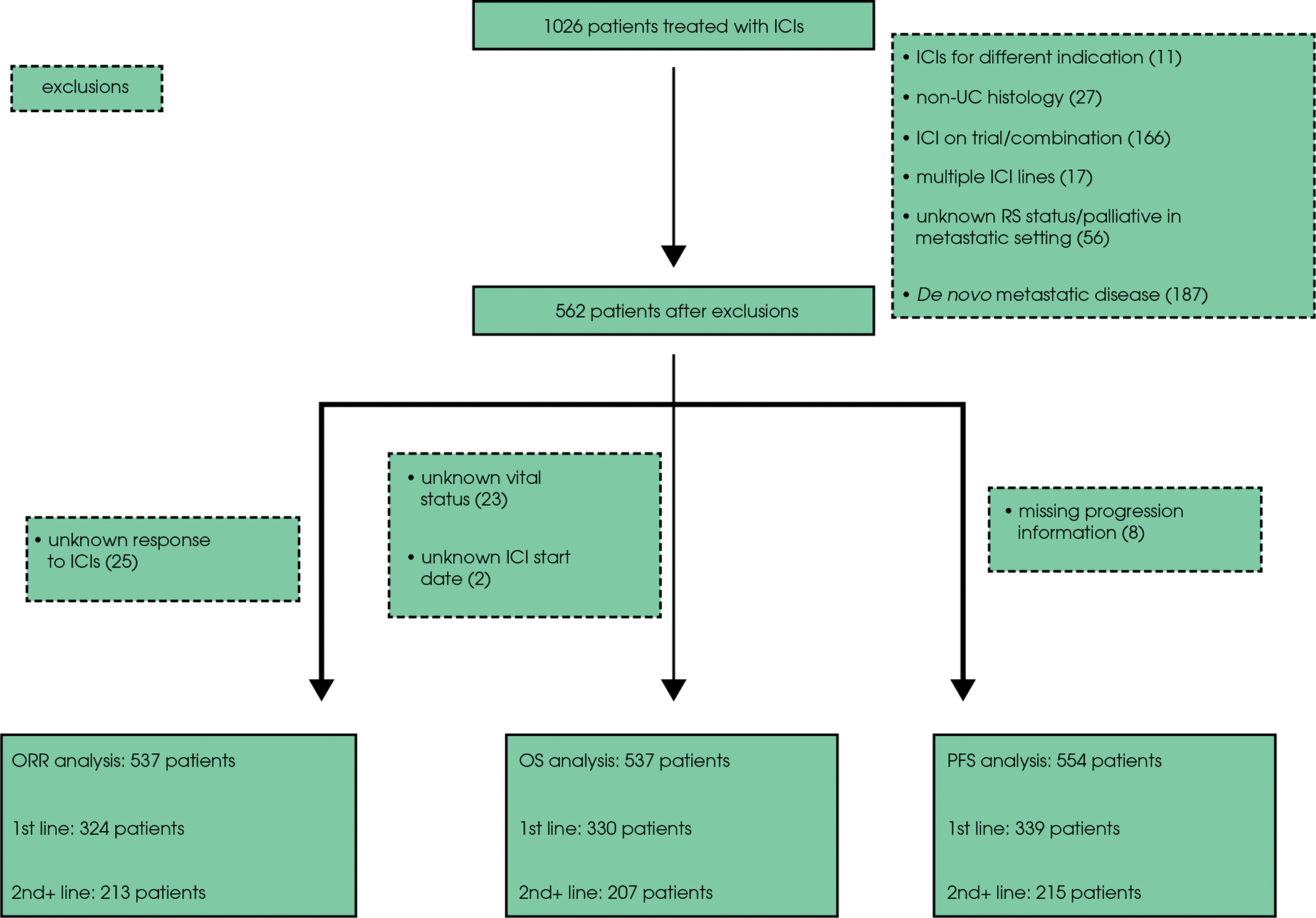

Patients were excluded if they had missing data, de novo advanced disease (unresectable or metastatic), had received multiple lines of ICIs, if ICI was given for a different indication, on a trial or in combination with other systemic therapy, if patients had pure non-UC histology, if RS history was unknown, or if they underwent palliative RS in the advanced disease setting (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram: patient selection and exclusion rationale. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; ORR, observed response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; UC, urothelial carcinoma.

For data collection and storage, we used web-based, secure and standardized REDCap capture tools hosted at the Institute of Translational Sciences [14,15]. Data collected included demographics, histology type, whether prior RS or RT was performed, laboratory values, sites of metastatic disease and outcomes (response, progression, death). Pathology and radiology results were assessed based on notes in the electronic health record; no central review of either was performed. All patients underwent imaging at the discretion of treating provider. Evaluation of response and progression were determined by the chart abstractor based on best available information in notes and radiographic studies.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics and compared via chi-squared and Student’s t-tests, for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Observed response rate (ORR) was determined on an investigator-provider basis and calculated as the sum of patients, with response divided by the total number of patients. OS was defined as time from ICI initiation to date of death, and PFS as time from ICI initiation until date of radiographic or clinical progression or death. Patients who did not experience death or progression were censored at the date of last follow-up.

All outcomes (ORR, PFS, OS) were analysed separately for patients treated with ICI in the first-line setting and the subsequent setting (second-line and beyond [second-plus]). For the primary analysis, we compared those with prior RS to those without prior RS. We also performed a secondary analysis comparing those with prior RS vs those with prior RT vs those with neither. The very few patients who had received both RS and RT were classified as recipients of RS in this secondary analysis. We also conducted an exploratory analysis comparing patients with lower tract urothelial carcinoma (LTUC) and those with upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC). We assume that those with LTUC underwent cystectomy and those with UTUC underwent (nephro)ureterectomy, although the specific type of RS was not explicitly collected in the survey tool. In both analyses, the group without history of locoregional therapy served as the reference group for all comparisons. We used univariable and multivariable logistic regression to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and CIs for ORR. For OS and PFS, we estimated medians using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared groups using univariable and multivariable Cox regression. For the multivariable analysis, models were adjusted based on calculated risk scores developed to prognosticate shorter OS; an internally developed risk score (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status [ECOG PS] ≥2, neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio > 5, albumin <35g/L (3.5g/dL), liver metastases [11]) was used for first-line and Bellmunt [16] for second-plus line analysis. The alpha value was set at 0.05 for all analyses. Analyses were performed with Stata IC 16.0 (Stata LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Data from 1026 patients with aUC treated with ICIs across 25 institutions were available, with 537, 537 and 554 patients ultimately included in the ORR, OS and PFS analyses, respectively (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients with and without prior RS, stratified by line of therapy (first and second-plus). Among 342 and 220 patients treated with first- and second-plus-line ICIs, 230 (67%) and 144 (65%) had prior RS, respectively. The median (interquartile range) time interval from RS to recurrence was 255 (101–479) days in the first-line and 422 (187–852) days in the second-plus-line subgroups, respectively. UTUC accounted for 14% in the first-line and 17% in the second-plus-line subgroup with a significantly higher proportion of patients with UTUC having had prior RS in both treatment setting subgroups. Among those without prior RS, 38 had received locoregional RT; 24 were treated with ICIs in the first-line setting and 14 in the second-plus-line setting. Only five patients had undergone both prior RS and RT.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma treated with checkpoint inhibitors, stratified by treatment line and prior radical surgery.

| Radical surgery, number of patients | First-line ICI treatment |

P | Second-plus-line ICI treatment |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||

| 112 | 230 | 76 | 144 | |||

| Age at ICI initiation, years | 74 (67–82) | 70 (61–77) | <0.001 | 71 (61–77) | 70 (64–74) | 0.48 |

| Male, n (%) | 83 (74) | 168 (73) | 0.83 | 64 (84) | 111 (77) | 0.21 |

| Ever smoker, n (%) | 78 (70) | 159 (69) | 0.99 | 58 (76) | 103 (71) | 0.45 |

| White race, n (%) | 74 (66) | 179 (78) | 0.02 | 52 (68) | 115 (80) | 0.06 |

| Pure UC, n (%) | 81 (72) | 153 (67) | 0.30 | 53 (70) | 111 (77) | 0.20 |

| Upper tract UC, n (%) | 10 (9) | 39 (17) | 0.05 | 7 (9) | 30 (21) | 0.03 |

| Prior platinum chemotherapy, n (%) | 25 (22)* | 149 (65) | <0.001 | 76 (94) | 131 (94) | 0.63 |

| Time from RS to metastatic progression, days | NA | 255 (101–479) | NA | NA | 422 (187–852) | NA |

| Albumin <35 g/L (3.5 g/dL) at ICI initiation, n (%) | 30 (27) | 57 (25) | 0.77 | 26 (34) | 23 (16) | 0.002 |

| Haemoglobin <10 g/dL at ICI initiation, n (%) | 33 (30) | 49 (21) | 0.11 | 26 (34) | 31 (22) | 0.04 |

| Liver metastasis at ICI initiation, n (%) | 12 (11) | 45 (20) | 0.04 | 10 (13) | 38 (26) | 0.02 |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 20 (18) | 50 (22) | 0.41 | 7 (9) | 24 (17) | 0.03 |

| 1 | 60 (54) | 101 (44) | 47 (58) | 85 (61) | ||

| 2 | 23 (21) | 47 (20) | 14 (17) | 19 (14) | ||

| 3 | 5 (5) | 4 (2) | 5 (6) | 1 (1) | ||

| 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Missing | 4 (4) | 27 (12) | 8 (10) | 11 (8) | ||

| Risk score†, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 40 (36) | 66 (29) | 0.44 | 6 (7) | 18 (13) | 0.31 |

| 1 | 29 (26) | 61 (27) | 37 (46) | 66 (47) | ||

| 2 | 18 (16) | 34 (15) | 26 (32) | 34 (24) | ||

| 3‡ | 13 (12) | 24 (10) | 3 (4) | 10 (7) | ||

| Missing | 12 (11) | 45 (20) | 9 (11) | 12 (9) | ||

| ICI received, n (%) | ||||||

| Atezolizumab | 39 (35) | 83 (36) | 0.74 | 46 (57) | 74 (53) | 0.55 |

| Avelumab | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | ||

| Durvalumab | 5 (5) | 5 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | ||

| Nivolumab | 5 (5) | 12 (5) | 5 (6) | 16 (11) | ||

| Pembrolizumab | 62 (55) | 125 (54) | 26 (32) | 45 (32) | ||

Data are median (interquartile range), unless otherwise stated. ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; UC, urothelial carcinoma.

Six patients received platinum-based chemotherapy with radiation; 19 received neoadjuvant platinum chemotherapy but did not proceed to cystectomy (either due to progression or patient preference).

First-line: Internally developed risk score [11]; Second or later line (second-plus): Bellmunt risk score [16].

First-line risk score includes four factors thus score of 3 is ≥3.

In the first-line setting, patients with prior RS were slightly younger (median 70 vs 74 years), with a significantly higher prevalence of white race, UTUC, presence of liver metastases, and prior receipt of platinum-based chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting. For those treated with ICIs in the second-plus-line setting, a significantly greater proportion with prior RS had UTUC and liver metastases and fewer patients had albumin levels <35g/L (3.5g/dL) and haemoglobin levels <10 g/dL (6.21 mmol/L) at the time of ICI initiation. Otherwise, in both the first- and second-plus-line subgroups, the distribution of risk scores (internally developed/published and Bellmunt [12,17]) was not significantly different between those with and without prior RS.

Observed Response Rate

A total of 537 patients were included in the ORR analysis; 324 and 213 patients were treated with ICIs in the first- and second-plus-line setting, respectively. The ORR between groups in the first-line setting was not significantly different: those with prior RS had an ORR of 28% (95% CI 23–34) and those without had an ORR of 33% (95% CI 24–42; Table 2). However, among those treated with ICIs in the second-plus-line setting, the ORR was 32% (95% CI 25–40) and 15% (95% CI 9–25) for those with and without prior RS, respectively (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.61 [95% CI 1.19–5.74]; Table 2). When type of locoregional therapy was considered in the model (no locoregional therapy vs RS vs RT), ORR with ICIs remained significantly higher for those with prior RS in the second-plus-line, but not in the first-line subgroup (Table 3). Upon analysing data based on the site of primary tumour, ORR was similar in the first-line subgroup, but in the second-plus-line subgroup, patients with prior RS for UTUC demonstrated lower ORR compared to those with LTUC (20% vs 36%; aOR 0.31 [95% CI 0.10–0.98]; Table S1).

Table 2.

Observed response rate, progression-free survival and overall survival according to prior radical surgery status, stratified by treatment line.

| ORR | ||||

|

| ||||

| Treatment line | History of RS? | ORR, % (95% CI) | Univariable OR (95% CI) | Multivariable* OR (95% CI) |

| First | No (n = 107) | 33 (24–42) | Reference | Reference |

| Yes (n = 217) | 28 (23–34) | 0.80 (0.49–1.33) | 0.73 (0.42–1.27) | |

| Second-plus | No (n = 73) | 15 (9–25) | Reference | Reference |

| Yes (n = 140) | 32 (25–40) | 2.67 (1.28–5.57)† | 2.61 (1.19–5.74)† | |

| PFS | ||||

|

| ||||

| Treatment line | Median PFS, months (95% CI) | Univariable HR (95% CI) | Multivariable* HR (95% CI) | |

| First | No (n = 112) | 6 (3–7) | Reference | Reference |

| Yes (n = 227) | 4 (3–5) | 1.12 (0.85–1.48) | 1.22 (0.89–1.66) | |

| Second-plus | No (n = 73) | 3 (2–4) | Reference | Reference |

| Yes (n = 142) | 5 (4–7) | 0.63 (0.45–0.87)† | 0.63 (0.45–0.89)† | |

| OS | ||||

|

| ||||

| Treatment line | Median OS, months (95% CI) | Univariable HR (95% CI) | Multivariable* HR (95% CI) | |

| First | No (n = 108) | 11 (7–14) | Reference | Reference |

| Yes (n = 222) | 10 (7–13) | 1.02 (0.75–1.38) | 1.10 (0.79–1.53) | |

| Second-plus | No (n = 70) | 5 (4–10) | Reference | Reference |

| Yes (n = 137) | 11 (8–18) | 0.65 (0.46–0.93)† | 0.61 (0.42–0.88)† | |

Table 3.

Observed response rate, progression-free survival and overall survival according to prior definitive locoregional therapy, stratified by treatment line.

| ORR | ||||

|

| ||||

| Treatment line | Definitive locoregional therapy | ORR, % (95% CI) | Univariable OR (95% CI) | Multivariable* OR (95% CI) |

| First-line | No surgery or radiation (n = 83) | 33 (23–43) | Reference | Reference |

| Radical surgery (n = 217) | 28 (23–34) | 0.81 (0.47–1.40) | 0.77 (0.43–1.40) | |

| Definitive radiation (n = 24) | 33 (18–54) | 1.04 (0.39–2.73) | 1.25 (0.43–3.63) | |

| Second-plus | No surgery or radiation (n = 59) | 10 (5–21) | Reference | Reference |

| Radical surgery (n = 140) | 32 (25–40) | 4.18 (1.67–10.48)† | 3.76 (1.46–9.69)† | |

| Definitive radiation (n = 14) | 36 (16–63) | 4.91 (1.23–19.59)† | 4.30 (0.92–20.13) | |

| PFS | ||||

|

| ||||

| Treatment line | Median PFS, months (95% CI) | Univariable HR (95% CI) | Multivariable* HR (95% CI) | |

| First | No surgery or radiation (n = 88) | 5 (3–9) | Reference | Reference |

| Radical surgery (n = 227) | 4 (3–5) | 1.12 (0.83–1.52) | 1.18 (0.84–1.65) | |

| Definitive radiation (n = 24) | 7 (2–13) | 1.01 (0.56–1.81) | 0.86 (0.46–1.63) | |

| Second-plus | No surgery or radiation (n = 59) | 3 (2–4) | Reference | Reference |

| Radical surgery (n = 142) | 5 (4–7) | 0.60 (0.42–0.86)† | 0.58 (0.40–0.84)† | |

| Definitive radiation (n = 14) | 4 (1–10) | 0.83 (0.44–1.57) | 0.71 (0.36–1.39) | |

| OS | ||||

|

| ||||

| Treatment line | Median OS, months (95% CI) | Univariable HR (95% CI) | Multivariable* HR (95% CI) | |

| First | No surgery or radiation (n = 85) | 12 (7–19) | Reference | Reference |

| Radical surgery (n = 222) | 10 (7–13) | 1.06 (0.76–1.47) | 1.09 (0.76–1.56) | |

| Definitive radiation (n = 23) | 10 (3–14) | 1.19 (0.66–2.16) | 0.96 (0.50–1.82) | |

| Second-plus | No surgery or radiation (n = 55) | 5 (4–9) | Reference | Reference |

| Radical surgery (n = 137) | 11 (8–18) | 0.62 (0.42–0.91)† | 0.57 (0.38–0.85)† | |

| Definitive radiation (n = 14) | 10 (2–21) | 0.93 (0.46–1.86) | 0.75 (0.36–1.57) | |

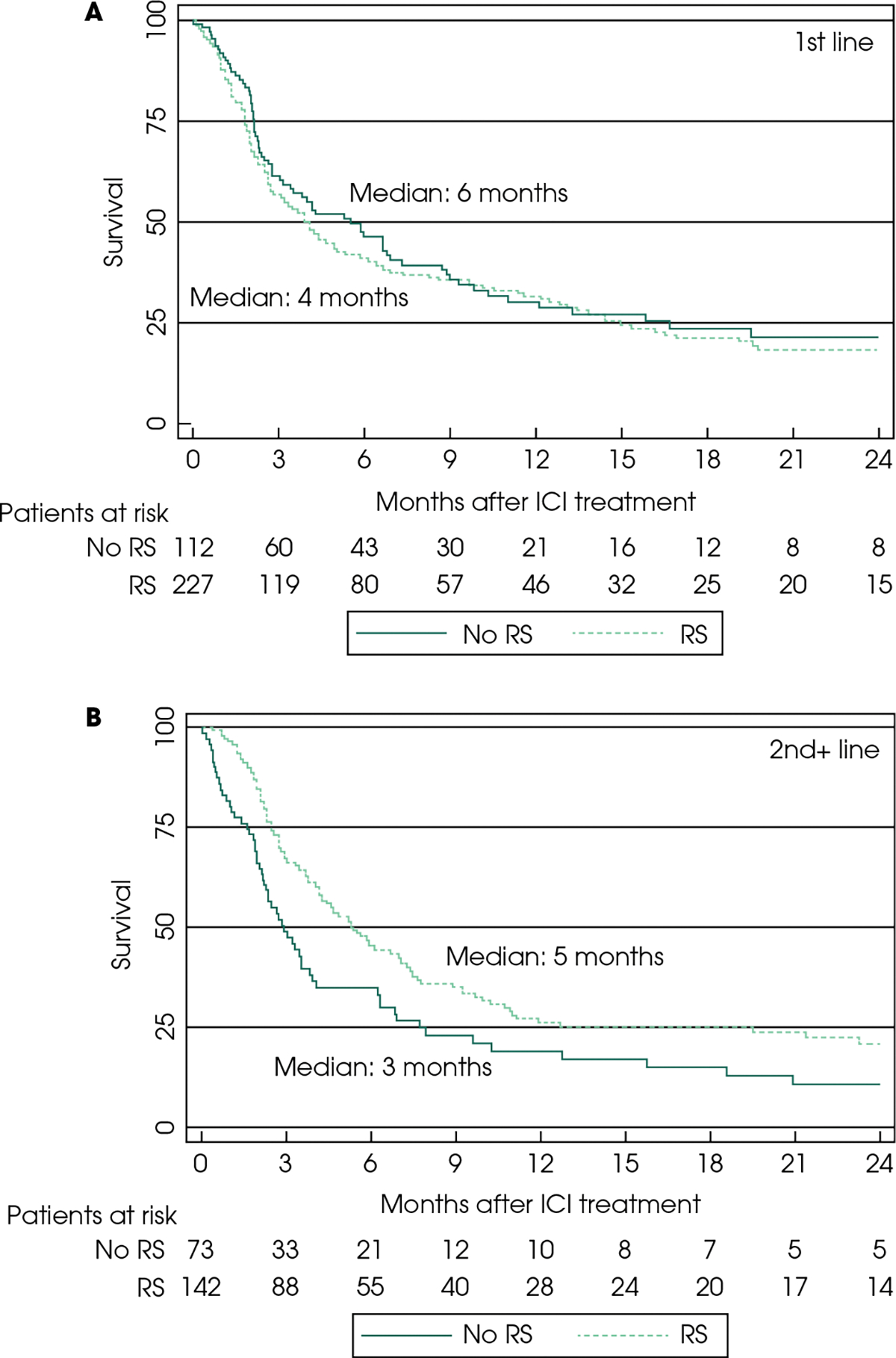

Progression-free Survival

A total of 554 patients were included in the PFS analysis; 339 and 215 were treated with ICIs in the first-and second-plus-line subgroups, respectively. The median PFS for those with and without prior RS was 4 months (95% CI 3–5) and 6 months (95% CI 3–7) in the first-line, and 5 months (95% CI 4–7) and 3 months (95% CI 2–4) in second-plus-line subgroups, respectively. Prior RS was associated with longer PFS in the second-plus-line but not the first-line setting (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.63 [95% CI 0.45–0.89]; Table 2; Fig. 2). This association of longer PFS in the second-plus-line subgroup with prior RS was also observed in the three-factor locoregional therapy model (Table 3; Fig. S1). In the exploratory analysis based on the site of the primary tumour, no significant difference in PFS was noted (Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival (OS) with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in the first-line- (A) and second-plus-line (B) setting. RS: radical surgery.

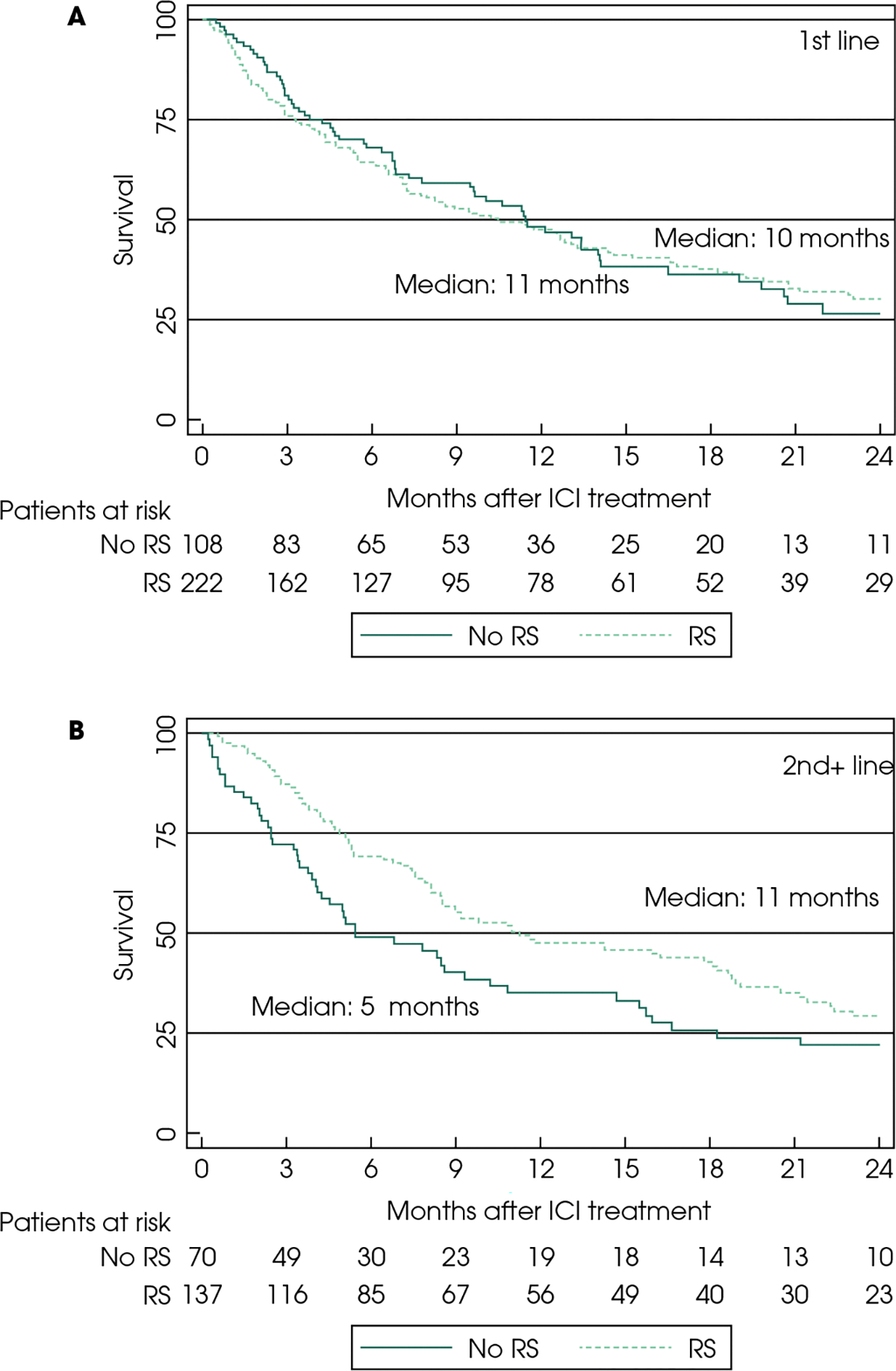

Overall Survival

A total of 537 patients were included in the OS analysis; 330 with first-line ICIs and 207 with second-plus-line ICIs. In the first-line subgroup, the OS between patients with vs without prior RS was similar (10 [95% CI 7–13] vs 11 months [95% CI 7–14]; aHR 1.10 [Table 2, Fig. 3]). In the second-plus line subgroup, patients with prior RS had longer median OS (11 [95% CI 8–18] vs 5 months [95% CI 4–10]), which was a significant association in our multivariable analyses (HR 0.61 [95% CI 0.42–0.88]; Table 2, Fig. 3). Upon comparing patients based on the three-factor locoregional therapy model, prior RS remained significantly associated with longer OS in the second-plus-line subgroup (Table 3, Fig. S2). In the exploratory analysis based on site of the primary tumour, no significant difference in OS was noted (Table S1).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for progression-free survival (PFS) with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in the first-line (A) and second-plus-line (B) setting. RS, radical surgery.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of patients with aUC treated with ICIs, history of RS was associated with higher ORR, as well as longer OS and PFS with ICIs in the second-plus-line, but not the first-line, setting. Prior definitive RT was associated with numerically, but not statistically significantly, higher ORR, and longer OS and PFS, a finding that might be attributed to the small sample size for this particular subset.

The association between prior RS and ORR, OS in patients receiving ICIs has not been well studied in aUC. To our knowledge, clinical trials of ICIs in aUC have not definitely investigated the association between prior RS and outcomes of ICI treatment. Prior retrospective studies from other solid-tumour malignancies have suggested that history of resection of the primary tumour can be associated with better outcomes with ICI therapy. Amin et al. [17] investigated outcomes of ICI treatment among patients with non-small lung cancer, breast cancer, melanoma, colorectal cancer or kidney cancer who had brain metastases, and noted longer OS among those with a history of surgical resection of the primary tumour. Similarly, Singla et al. [9] compared outcomes among patients with RCC treated with immunotherapy alone or with cytoreductive nephrectomy and noted longer OS for those treated with cytoreductive nephrectomy and immunotherapy. Selection and confounding biases may impact the outcome of such retrospective studies, with performance status, frailty and overall fitness being major potential confounders. Prospective clinical trials may ultimately help answer similar questions (e.g. S1931/PROBE).

In the setting of aUC, surgical considerations such as RS remain controversial. Radical cystectomy is associated with morbidity and has not been shown to definitively improve outcomes. At a molecular level, metastatic disease may have tumour heterogeneity, rendering the radical treatment of only part of the disease less valuable. Establishment of metastases implies the presence of circulating tumour cells seeding distant tissues, and making surgery seem futile.

Despite such concerns, prior retrospective studies in patients with aUC treated with cytoreductive or palliative cystectomy have also suggested that this approach might be appropriate for a subpopulation of patients with aUC. Li et al. [18] found that post-chemotherapy RS was associated with longer OS in patients with aUC compared with those treated with local radiation or no local therapy. A review by Abufaraj et al. [19] suggested that RS may be beneficial for patients with prior response to chemotherapy and low volume of disease. Moschini et al. [20] also reported a significant survival benefit for patients with up to one metastatic site. These results, despite their several inherent caveats, raise the question of whether carefully selected patients with aUC, especially those with very well controlled disease and an indolent course, might potentially benefit from RS. However, it remains unclear whether there is any interaction between RS (and its timing over the disease course) with response and outcomes with ICIs. While most of those studies in aUC or other solid tumours investigate the role of extirpative surgery in the advanced setting, our results suggest that prior RS for locoregional-only disease may also portend favourable prognosis.

It was also notable that in the present analysis of RS vs no-RS, non-RS treated patients included those with prior RT, which may have acted as a confounding factor. In the three-factor model for analysis of prior locoregional therapy type, separation of RT-treated patients from those without history of any locoregional therapy showed that the latter subset had significantly worse outcomes compared to those treated with prior RS.

Locoregional RT has been associated with greater response to ICIs, and a possible role for abscopal effect has been suggested [21,22]. However, when the abscopal effect was noted in studies, RT was administered concurrently to ICI, whereas in the present study RT was given prior to development of metastatic disease and ICIs were given for metastatic disease, so RT and ICIs were not given together and for most patients the time between RT and ICI treatment was extensive. The relative timing of RT and ICI administration was recently tested in a randomized phase I trial comparing pembrolizumab with sequential vs concomitant stereotactic body RT to a single metastatic lesion in 18 patients with aUC [23]. In this study, none of the nine patients randomized to sequential therapy had response (ORR 0%), whereas the ORR for those receiving concurrent RT was 44%. While the small sample and selection bias of this study require further external validation, those results suggest potential synergy between concomitant RT and ICIs, but not sequential therapy. The cohort in the present study did not demonstrate a clear signal of abscopal effect; patients had received RT before initiation of ICI, not concurrently, with variable time intervals between the two. However, the present study showed that prior locoregional RT had a trend towards better outcomes, but did not reach statistical significance, which could suggest a possible association that was limited by the small sample size and warrants further evaluation in larger cohorts.

In the present cohort, response rates in the second-plus-line setting were significantly greater among patients treated with prior locoregional treatment (ORR; 32% and 36% for RS and RT recipients, respectively, vs only 10% for those without prior locoregional therapy). This substantial difference could possibly be influenced by confounding factors, such as older age, worse ECOG PS or medical comorbidities that can render patients poor RT/RS candidates and also dampen immune response with ICI treatment. It is notable that in an exploratory analysis of cisplatin-ineligible patients of more senior age and poor PS in the KN-052 study, ORR was not significantly different in any subgroup, including among patients aged ≥65 and ≥75 years with ECOG PS of 2 [24]. Prior work from our registry has also shown that patients with ECOG PS ≥2 had similar ORR to those with ECOG PS 0–1, although none of the 11 patients with ECOG PS 3 had response [13]. In the present analysis, we considered the possible confounding influence by including risk scores in our multivariable model (internally developed risk factor model [11] for first-line treatment [adjusting for ECOG PS ≥ 2, neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio > 5, albumin <35g/L (3.5g/dL), liver metastasis] and for Bellmunt risk factors [16] for second-plus-line treatment) that have been developed to help discriminate patients with different outcomes. Therefore, the notion of a potential positive impact of prior RS on ICI response remains plausible.

While history of RS was associated with a higher response rate to ICIs and longer survival in the second-plus-line subgroup, this association was not significant in the first-line subgroup. This discordance may possibly be attributed to confounding factors. Patients treated with ICIs in the first-line setting can often be cisplatin-ineligible due to frailty and/or comorbidities, such as chronic kidney disease. Moreover, PD-L1 expression can be used for patient selection for ICIs in cisplatin-ineligible patients in the first-line setting, which can impact response and survival in this setting, while PD-L1 is not used for patient selection in the second-plus-line setting. This and other potential confounding factors may determine therapy response and outcomes in addition to specific anti-cancer therapies. In the second-plus-line treatment setting, patients without prior RS may be substantially more frail / less fit, which can further impact the outcome in this clinical setting of pretreated patients. The overall state of health of individuals receiving ICIs can possibly be associated with the robustness of the immune system, a factor that probably also affects immune system response.

Our analysis comparing outcomes with ICIs based on the primary tumour site (UTUC vs LTUC) showed that patients with prior RS with LTUC had a significantly higher ORR in the second-plus-line setting compared to those with UTUC. Our team previously investigated the association of primary tumour site with response to ICI treatment, demonstrating no significant differences [12] between UTUC and LTUC in all evaluated patients. It is possible that the difference detected in the present analysis might be attributed to both the relatively small sample size, as the second-plus-line subgroup consisted of 109 patients with LTUC and 30 with UTUC, as well as the selection of patients with prior RS.

The present study is retrospective and thus should be interpreted with caution. Our results provide insights into the association between prior RS and response to ICIs, raising the hypothesis that RS may possibly be associated with future ICI response after subsequent development of advanced disease. Our results cannot guarantee that differences in ICI response and survival are solely attributable to RS, and, not to other confounding factors, such as patient performance status and comorbidities. However, one may extrapolate that RS could be considered as an option in borderline resectable cases in the absence of metastatic disease and, therefore, could influence such informed/shared decision making. The decision to administer ICIs in aUC should not be based on whether the patient had prior RS or not, but our data may inform clinical discussions about prognostication and risk stratification.

Our results may also inform the interpretation of clinical trials evaluating ICIs in aUC. For example, the proportion of patients with prior RS in clinical trials may impact response and survival rates associated with ICIs. The selection of an ICI (pembrolizumab) vs a fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitor, erdafitinib, in the platinum-refractory setting is being assessed in the phase III THOR trial; the proportion of patients with prior RS enrolled may possibly affect the endpoint. Another potential indirect implication is the discussion about the optimal design and duration of ICI therapy in peri-operative clinical trials. For example, multiple phase II clinical trials with ICIs in the neoadjuvant setting have shown promising efficacy, measured by pathological complete response rate [25–28]. However, the question remains whether ICIs should be tested in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant, or both settings. Primary analysis from the adjuvant IMvigor 010 trial did not detect a significant disease-free survival benefit with atezolizumab vs observation [29], while the Checkmate 274 trial [30] showed significantly prolonged disease-free survival with adjuvant nivolumab vs placebo. Since the presence of the primary tumour may possibly compromise ORR and survival with ICIs in aUC, a generated hypothesis is that the adjuvant component may be relevant in peri-operative trials. However, the different disease settings (localized vs metastatic) can significantly limit the extrapolation of our findings to the peri-operative treatment scenario.

The present study has several limitations inherent to the retrospective study design, including lack of randomization, potential selection bias and residual confounding. In addition, clinical practices, surveillance schedules and follow-up times may vary, while documentation might not be perfectly consistent across all 25 institutions. We did not have centralized review of pathology or imaging, but all participating sites are reference academic sites with expert genitourinary oncologists, radiologists and pathologists. Detailed clinical staging information prior to locoregional therapy was not available, nor were data on response to peri-operative chemotherapy. Radical surgery approaches may also vary among institutions; however, all institutions were academic centres with dedicated genitourinary oncologists with relevant expertise, so there was not likely to have been significant variability in the quality of RS. Response and progression were determined by systematic comprehensive chart review based on clinical and radiological notes without mandating formal, prespecified interval assessments via RECIST 1.1 criteria.

The present study also had strengths, including the utilization of ‘real-world’ data, participation of multiple institutions on two continents, and a relatively large sample size.

In conclusion, the present study showed there was a significantly higher ORR, longer OS and PFS after ICI treatment in the second-plus-line setting in patients with aUC and prior RS compared to patients with no prior RS. Despite its inherent limitations, this analysis provides insight into an important topic that has not been extensively studied. Future research is needed to identify biomarkers and clinical tools that can better identify patients with aUC more likely to benefit from ICI treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

D. Makrakis and L. N. Diamantopoulos acknowledge the support of Kure It Cancer Research. E. Y. Yu and P. Grivas acknowledge the support of the Seattle Translational Tumor Research Program at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. D. J. Pinato acknowledges the infrastructure support provided by the Imperial Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, Cancer Research UK Imperial Centre, the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust Tissue Bank and the Imperial College BRC.

A. R. Khaki was supported by the National Cancer Institute under training grant T32CA009515. Research Electronic Data Capture at the Institute of Translational Health Sciences is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award UL1 TR002319. David J. Pinato is supported by grant funding from the Wellcome Trust Strategic Fund (PS3416).

Abbreviations:

- aHR

adjusted hazard ratio

- aUC

advanced urothelial carcinoma

- ECOG PS

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICI

immune checkpoint inhibitor

- LTUC

lower tract urothelial carcinoma

- mOS

median overall survival

- OR

odds ratio

- ORR

observed response rate

- OS

overall survival

- PD-L1

programmed-death ligand-1

- PFS

progression-free survival

- RT

radiation therapy

- UTUC

upper tract urothelial carcinoma

- NMIBC

non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

- CR

Complete Response

- PR

Partial Response

- SD

stable disease

- PD

progressive disease

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

D. Makrakis, R. Talukder, L. N. Diamantopoulos, L. Carril-Ajuria, J. Park, V. Santos, J. Jain, M. Devitt, A. Nelson, E. Shreck, B. A. Gartrell, Sankin, R. Zakopoulou, J. Murgic, Frobe, V. Kumar and M. Moses have no conflicts of interest to declare. D. Castellano received travel support from Pfizer, BMS, Astellas, Roche, GSK, Bayer and Ipsen, and acted as advisor for Pfizer, BMS, Exelixis, Astellas, Roche, GSK, Bayer, Ipsen, Pierre-Fabre, MSD, Astra Zeneca, Novartis, AAA and Eisai, Eusa. I. De Kouchkovsky received Merit Award funds from the ASCO Foundation. V. Koshkin received grants/contracts from Endocyte, Nektar, Clovis, Jannsen and Taiho, and consulting fees from Astra Zeneca, Clovis, Jansen, Pfizer, EMD Serono, Seattle Genetics / Astellas and Dendreon, and payment/honoraria for speaking/lectures from Seattle Genetics / Astellas. A. Alva received grants/contracts from Arcus Biosciences, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, LP Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Eisai Inc., Esanik, Ionnis, Merck & Co., Inc. and Prometheus, consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, EMD Serono, Merck & Co., Inc., and Pfizer Inc., and had a leadership/fiduciary role in ASCO TAPUR/CRC. M. A. Bilen has acted as a paid consultant for and/or as a member of the advisory boards of Exelixis, Bayer, BMS, Eisai, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Genomic Health, Nektar and Sanofi, and has received grants to his institution from Xencor, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, Seattle Genetics, Incyte, Nektar, AstraZeneca, Tricon Pharmaceuticals, Peleton Therapeutics and Pfizer for work performed outside of the present study. T. Stewart served as an advisor for Seagen/Astellas. R. R. McKay received research funding from Bayer, Pfizer and Tempus, serves on the Advisory Board for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Calithera, Exelixis, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Tempus and Myovant, is a consultant for Dendreon and Vividion, and serves on the molecular tumour board at Caris. N. Agarwal served as advisory/consultant for Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Aveo, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Calithera, Clovis, Eisai, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Exelixis, Foundation Medicine, Genentech, Janssen, Merck, MEI Pharma, Nektar, Novartis, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics and Seattle Genetics. Y. Zakharia served as advisor to BMS, Amgen, Roche Diagnostics, Novartis, Janssen, Eisai, Exelixis, Castle Bioscience, Array, Bayer, Pfizer, Clovis and EMD Serono. R. Morales-Barrera received payment/honoraria for lectures from Sanofi Aventis, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Astellas, BMS, Pfizer and Roche, and support for travel from Roche, Sanofi Aventis, Astellas, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bayer and Pfizer. M. Grant received honoraria for work in preparing case studies from Keynote 426 trial from MSD UK. M. Lythgoe received an educational grant from Bayer to attend ASCO GU 2020. D. J. Pinato received consulting fees from DaVolterra, H3B, EISAI, Roche and MiNa Therapeutics, payment for lectures/speaking from ViiV Healthcare, Bayer Healthcare, EISAI, Roche, travel support from BMS, MSD and Roche, and participated in an advisory board for AZ, EISAI and Roche. C. J. Hoimes received grants/contracts from Astellas, BioNTech, Eisai, Merck &Co, BMS, Genentech/Roche and Seagen, consulting fees from Merck &Co, BMS, Genentech/Roche and Seagen, payment/honoraria for lectures from Eisai, Merck &Co, BMS, Genentech/Roche and Seagen, travel support from BioNTech and Genentech/Roche and participated as an advisor for Seagen and Merck & Co. A. Tripathi received grants/contracts from EMD Serono, Bayer, Clovis Oncology, Aravive Inc., WindMIL Therapeutics and Corvus Pharmaceuticals, and served as an advisor for Foundation Medicine and Pfizer, Genzyme, EMD Serono, Exelixis. A. Bamias received grants/contracts from Pfizer, BMS, Astra Zeneca, Ipsen, and served as advisor and received payment/honoraria for lectures from BMS, Ipsen, MSD. A. Rodriguez-Vida received grants/contracts from Takeda, Pfizer and Merck, consulting fees from MSD, Pfizer, BMS, Astellas, Janssen, Bayer, Clovis, Ipsen and Roche, and payment for speaking from Pfizer, MSD, Astellas BMS, Janssen, Astra Zeneca, Roche, Bayer, Ipsen and Sanofi Aventis. A. Drakaki served as advisor and received consulting fees from Merck, Genentech/Roche, Astra Zeneca, PACT Pharma, NEKTAR and SeaGen, travel support from Astra Zeneca for attending ASCO GU 2019, and participated in a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Nektar. S. Liu received payment/honoraria for speaking/lecture from Exelixis, EMD-Serono and Merck. G. Di Lorenzo served as advisor/on the Data Safety Monitoring Board for Janssen, Astellas, Ipsen and Pfizer. M. Joshi received research grants from Astra Zeneca and Pfizer. P. Isaacson-Velho received grants from ASCO Conquer Cancer Foundation, consulting fees from Bayer, Astellas and AstraZeneca, payment for lectures and travel support from Astellas, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Merck, MSD, Janssen and BMS, and served as an advisor for Astellas, Pfizer and AstraZeneca. I. Duran received grants from Astra Zeneca and Roche, payments for lectures from Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD Ipsen, Roche-Genentech, Janssen, Astellas Pharma, EUSA Pharma, Bayer and Novartis, travel support from Astra-Zeneca, Ipsen and Pfizer, and served as advisor for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ipsen, Roche-Genentech, Astellas Pharma, Immunomedics, Seattle Genetics and Pharmacyclics. P. Barrata received grants from Seattle Genetics, BlueEarth Diagnostics, Nektar and AstraZeneca, and served as advisor for Exelixis, Caris, Bayer, Janssen, EMD/Serono, Pfizer, Astellas, Dendreon, Clovis and Sanofi. G. Sonpavde received grants from Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Immunomedics/Gilead, QED, Predicine and BMS, payment for lectures/manuscript writing/educational events from Physicians Education Resource (PER), Onclive, Research to Practice, Medscape (all educational), and Uptodate, is Editor of Elsevier Practice Update Bladder Cancer Center of Excellence, and has received travel support from BMS (2019), AstraZeneca (2018). He has served as advisor for BMS, Genentech, EMD Serono, Merck, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics/Astellas, Astrazeneca, Exelixis, Janssen, Bicycle Therapeutics, Pfizer, Immunomedics/Gilead, Scholar Rock, G1 Therapeutics, Mereo, and in steering committees for studies for BMS, Bavarian Nordic, Seattle Genetics, QED, G1 Therapeutics (all unpaid), and AstraZeneca, EMD Serono, Debiopharm (paid). E. Y. Yu received grants from Merck and Genentech, consulting fees from Merck and AstraZeneca, and travel support from Merck. J. L. Wright has received grants from Nucleix, Inc, Altor Biosci, Merck, SWOG and National Institutes of Health, royalties/licences from UpToDate, and consulting fees from Sanofi-Genzyme. P. Grivas’ institution has received grants from Bavarian Nordic, Bristol Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology, Debiopharm, EMD Serono, GlaxoSmithKline, Immunomedics, Kure It Cancer Research, Merck & Co., Mirati Therapeutics, Pfizer, QED Therapeutics, and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology, Dyania Health, Driver, EMD Serono, Exelixis, Foundation Medicine, Genentech/Roche, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Guardant Health, Heron Therapeutics, Immunomedics/Gilead, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Merck & Co., Mirati Therapeutics, Pfizer, QED Therapeutics, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Seattle Genetics and 4D Pharma PLC in the last 3 years. A. R. Khaki temporarily owned stocks of Sanofi & Merck in the last 3 years.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Fig S1. Kaplan–Meier curves for progression-free survival (PFS) with checkpoint inhibitors comparing history of radical surgery vs radiation therapy vs neither in the first-line (A) and second-plus line (B) setting.

Fig S2. Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival (OS) with checkpoint inhibitors comparing history of radical surgery vs radiation therapy vs neither in the first-line (A) and second-plus-line (B) setting.

Table S1. Observed response rate, progression-free survival and overall survival according to treatment line and primary tumour site in patients with prior RS.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68: 7–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abufaraj M, Gust K, Moschini M et al. Management of muscle invasive, locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a literature review with emphasis on the role of surgery. Transl Androl Urol 2016; 5: 735–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moschini M, Zamboni S, Karnes JR et al. Clinical recurrence after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer, defining optimal surveillance after surgery. Eur Urol Supp 2019; 18: e1144 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mari A, Campi R, Tellini R et al. Patterns and predictors of recurrence after open radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: a comprehensive review of the literature. World J Urol 2018; 36: 157–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sargos P, Baumann BC, Eapen L et al. Risk factors for loco-regional recurrence after radical cystectomy of muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A systematic-review and framework for adjuvant radiotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev 2018; 70: 88–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powles T, Park SH, Voog E et al. Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1218–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powles T, Durán I, van der Heijden MS et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 391: 748–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gopalakrishnan D, Koshkin VS, Ornstein MC et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in urothelial cancer: recent updates and future outlook. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2018; 14: 1019–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singla N, Hutchinson RC, Ghandour RA et al. Improved survival after cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the contemporary immunotherapy era: An analysis of the National Cancer Database. Urol Oncol 2020; 38: 604.e9–604.e17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller NJ, Khaki AR, Diamantopoulos LN et al. Histological subtypes and response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in advanced urothelial cancer: a retrospective study. J Urol 2020; 204: 63–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khaki AR, Li A, Diamantopoulos LN et al. A new prognostic model in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma treated with first-line immune checkpoint inhibitors [published online ahead of print, 2021 Jan 7]. Eur Urol Oncol 2021; 4: 464–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esagian SM, Khaki AR, Diamantopoulos LN et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced upper and lower tract urothelial carcinoma: a comparison of outcomes. BJU Int 2021; 128: 196–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khaki AR, Li A, Diamantopoulos LN et al. Impact of performance status on treatment outcomes: A real-world study of advanced urothelial cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer 2020; 126: 1208–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; 95: 103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellmunt J, Choueiri TK, Fougeray R et al. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract experiencing treatment failure with platinum-containing regimens. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 1850–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin S, Baine MJ, Meza JL, Lin C. Association of immunotherapy with survival among patients with brain metastases whose cancer was managed with definitive surgery of the primary tumor. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e2015444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li R, Metcalfe M, Kukreja J, Navai N. Role of radical cystectomy in non-organ confined bladder cancer: a systematic review. Bladder Cancer 2018; 4: 31–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abufaraj M, Dalbagni G, Daneshmand S et al. The role of surgery in metastatic bladder cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol 2018; 73: 543–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moschini M, Xylinas E, Zamboni S et al. Efficacy of surgery in the primary tumor site for metastatic urothelial cancer: analysis of an international, multicenter. Multidisciplinary Database. Eur Urol Oncol 2020; 3: 94–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rompré-Brodeur A, Shinde-Jadhav S, Ayoub M et al. PD-1/PD-L1 Immune checkpoint inhibition with radiation in bladder cancer. In Situ and Abscopal Effects. Mol Cancer Ther 2020; 19: 211–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daro-Faye M, Kassouf W, Souhami L et al. Combined radiotherapy and immunotherapy in urothelial bladder cancer: harnessing the full potential of the anti-tumor immune response. World J Urol 2021; 39: 1331–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundahl N, Vandekerkhove G, Decaestecker K et al. Randomized phase 1 trial of pembrolizumab with sequential versus concomitant stereotactic body radiotherapy in metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol 2019; 75: 707–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grivas P, Plimack ER, Balar AV et al. Pembrolizumab as first-line therapy in cisplatin-ineligible advanced urothelial cancer (KEYNOTE-052): Outcomes in older patients by age and performance status. Eur Urol Oncol 2020; 3: 351–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horowitz M, Neeman E, Sharon E, Ben-Eliyahu S. Exploiting the critical perioperative period to improve long-term cancer outcomes. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015; 12: 213–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Necchi A, Anichini A, Raggi D et al. Pembrolizumab as neoadjuvant therapy before radical cystectomy in patients with muscle-invasive urothelial bladder carcinoma (PURE-01): An Open-Label, Single-Arm, Phase II Study. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 3353–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powles T, Kockx M, Rodriguez-Vida A et al. Clinical efficacy and biomarker analysis of neoadjuvant atezolizumab in operable urothelial carcinoma in the ABACUS trial. Nat Med 2019; 25: 1706–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Dijk N, Gil-Jimenez A, Silina K et al. Preoperative ipilimumab plus nivolumab in locoregionally advanced urothelial cancer: the NABUCCO trial. Nat Med 2020; 26: 1839–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hussain MHA, Powles T, Albers P et al. IMvigor010: Primary analysis from a phase III randomized study of adjuvant atezolizumab (atezo) versus observation (obs) in high-risk muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma (MIUC). J Clin Oncol 2020; 38(15_suppl): 5000 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bajorin DF, Witjes JA, Gschwend J, Schenker M. First results from the phase 3 CheckMate 274 trial of adjuvant nivolumab vs placebo in patients who underwent radical surgery for high-risk muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma (MIUC). J Clin Oncol 2021; 39(6_suppl): 391 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.