Abstract

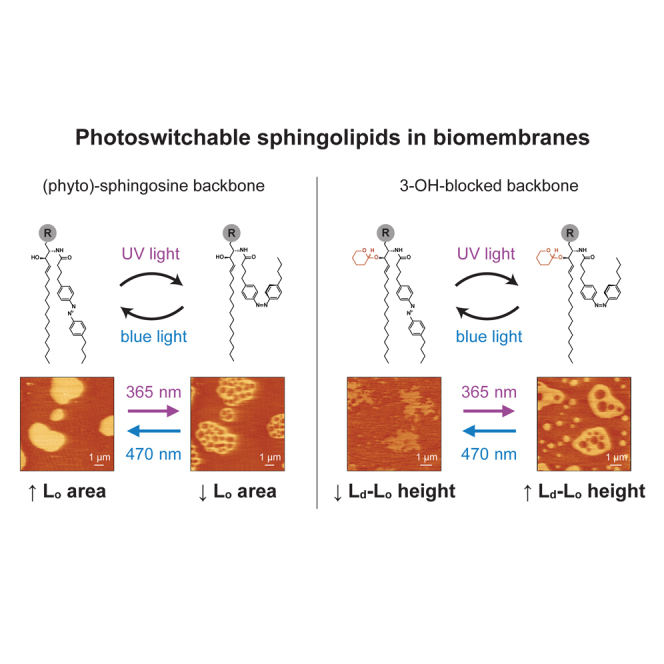

Sphingolipids are a structurally diverse class of lipids predominantly found in the plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells. These lipids can laterally segregate with other rigid lipids and cholesterol into liquid-ordered domains that act as organizing centers within biomembranes. Owing the vital role of sphingolipids for lipid segregation, controlling their lateral organization is of utmost significance. Hence, we made use of the light-induced trans-cis isomerization of azobenzene-modified acyl chains to develop a set of photoswitchable sphingolipids with different headgroups (hydroxyl, galactosyl, phosphocholine) and backbones (sphingosine, phytosphingosine, tetrahydropyran-blocked sphingosine) that are able to shuttle between liquid-ordered and liquid-disordered regions of model membranes upon irradiation with UV-A (λ = 365 nm) and blue (λ = 470 nm) light, respectively. Using combined high-speed atomic force microscopy, fluorescence microscopy, and force spectroscopy, we investigated how these active sphingolipids laterally remodel supported bilayers upon photoisomerization, notably in terms of domain area changes, height mismatch, line tension, and membrane piercing. Hereby, we show that the sphingosine-based (Azo-β-Gal-Cer, Azo-SM, Azo-Cer) and phytosphingosine-based (Azo-α-Gal-PhCer, Azo-PhCer) photoswitchable lipids promote a reduction in liquid-ordered microdomain area when in the UV-adapted cis-isoform. In contrast, azo-sphingolipids having tetrahydropyran groups that block H-bonding at the sphingosine backbone (lipids named Azo-THP-SM, Azo-THP-Cer) induce an increase in the liquid-ordered domain area when in cis, accompanied by a major rise in height mismatch and line tension. These changes were fully reversible upon blue light-triggered isomerization of the various lipids back to trans, pinpointing the role of interfacial interactions for the formation of stable liquid-ordered domains.

Graphical abstract

Significance

Sphingolipids are predominantly found at the plasma membrane of cells and are recurrently associated to segregated liquid-ordered domains with important cellular functions (e.g., signaling). Controlling the lateral organization of lipids within microdomains is thus of utmost significance. In this work, we took advantage of the light-triggerable trans-cis isomerization of azobenzene-modified acyl chains and designed novel photoswitchable sphingolipids with varying headgroups and sphingoid backbones. By combining atomic force and fluorescence microscopies, we were able to evaluate the ability of these photoswitchable lipids to reversibly alter the properties and amount of lipid domains on phase-separated model membranes by light, having identified the importance of sphingoid base functionality for a differential optical control of liquid-ordered properties by photoswitchable sphingolipids.

Introduction

Sphingolipids are a major component of eukaryotic (notably mammalian) membranes and play a crucial role in signaling inside cells (1,2,3). Members of this lipid class, like ceramide (Cer) or sphingomyelin (SM), have a backbone formed from sphingosine and have been widely studied in terms of their biophysical properties, behavior on membrane models, and affinity to other lipids (4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11). Another important, but less studied, class of sphingolipids is phytosphingolipids, which are abundant in plants and fungi (12,13,14). These lipids have phytosphingosine as a sphingoid base (2), a backbone with increased polarity compared with sphingosine. Sphingolipids are also largely localized in the plasma membranes of eukaryotic cells when compared with inner organelle membranes (3). Here, they are usually linked to so-called lipid rafts (15), liquid-ordered (Lo) phase domains composed of rigid lipid species (sphingolipids and saturated phospholipids) and sterols, thought to be a means by which cells organize or segregate important proteins within the membrane (16,17,18). In addition, sphingolipids have been shown to be distributed asymmetrically in the plasma membrane, being highly enriched on the outer leaflet (19).

From a molecular point of view, sphingolipids can form stable H-bond and hydrophobic interactions with other sphingolipids (e.g., SM) and cholesterol (Chol) (2,20). While in vivo such lipid interactions are assumed to be transient and lead to the formation of nanoscopic domains (21,22), these can, e.g., be observed in vitro on supported membrane model systems, as segregated rigid Lo phase microdomains embedded in a fluid bulk liquid-disordered (Ld) membrane phase (23,24,25,26,27). The presence of hydroxyl (–OH) groups on the backbone of sphingolipids are particularly relevant for the formation of Lo domains, as interfacial H-bonding markedly stabilizes the interactions among sphingolipids and Chol (20,28). In fact, the central role of the 3-OH moiety on the sphingosine backbone of sphingolipids, like Cer or SM, has been thoroughly scrutinized (13,29,30,31,32,33,34,35). Likewise, the presence of a second 4-OH hydroxyl group on phytosphingosine-based lipids, like PhCer, further strengthens H-bonding and domain thermostability (13). In contrast, hindering H-bonding by adding a methyl, ethyl, or tetrahydropyranyl (THP) group at the 3-OH hydroxyl severely affected the molecular packing and ability of those blocked sphingolipids to interact with Chol (29,36). Indeed, functionalization of the 3-OH of SM by THP greatly decreases gel-phase stability (lowering the melting temperature by 10°C), impedes tight contacts with Chol, and increases the rate of sterol desorption from vesicles containing this blocked SM analog (29).

As lipid segregation plays a crucial physiological role in biomembranes, new tools to investigate and control membrane phase properties are urgently needed. In that regard, strategies based on photopharmacology (37,38), which take advantage of the high spatiotemporal precision of light, are particularly appealing. In 2016, we reported that photoswitchable Cers (ACes), which have an azobenzene photoswitch incorporated in the lipid fatty acid chain, enable optical control of lipid raft-mimicking microdomains within synthetic membranes (39). While recent advancements demonstrated the potential of azobenzene-modified photoswitchable lipids for controlling/altering membrane properties without significant physiological perturbations (39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47), the structural diversity of these photoactive molecules is nonetheless still fairly limited. This stands in stark contrast to the impressive diversity of sphingolipids found in nature. Indeed, diverse sphingolipids can serve as docking sites for various toxins (e.g., Shiga toxin binds to Gb3 (48) or cholera toxin B binds to GM1 (49)) or can even modulate the uptake of viruses by the cells (e.g., SV40 requires GM1 as receptor (50) or HIV-1 gp120 surface protein binds to GalCer on epithelial cells (51)). Hence, controlling their lateral organization within membranes is of vital importance. An expanded palette of photoswitchable sphingolipids could therefore offer new photoresponsive N-acyl azobenzene sphingolipids with more complex headgroup functionalities and other types of sphingoid backbones.

In our present work, we then aimed to develop a new set of photoswitchable sphingolipids with increased functionalization and incorporate these various photoswitchable lipids (photolipids) into Ld-Lo phase-separated supported model membranes. Our main goal was to investigate the influence of these modifications on the reversible remodeling of membrane microdomains upon photoswitching, as well as on fundamental mechanical properties of lipid bilayers. To this end, we performed atomic force microscopy (AFM) combined with fluorescence confocal microscopy, following the generated changes in domain area, height, and line tension.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of N-acyl azobenzene-modified sphingolipids

A protocol for the synthesis and analysis of all photolipids can be found in the supporting material. Also, a schematic overview of all synthesis can be found on page 28 of the supporting material.

Membrane model systems

Throughout this work, small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) and supported lipid bilayers (SLBs) were used as lipid membrane model systems. These were primarily composed by N-stearoyl-d-erythro-sphingosylphosphorylcholine (C18-SM, or simply SM), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), and Chol, which were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA), into which different photolipids, notably Azo-Cer, Azo-PhCer, Azo-THP-Cer, Azo-α-Gal-PhCer, Azo-β-Gal-Cer, Azo-SM, or Azo-THP-SM, were mixed. Also, native N-stearoyl-d-erythro-sphingosine (C18-Cer), d-galactosyl-β-1,1′-N-stearoyl-d-erythro-sphingosine (C18-β-Gal-Cer), and N-stearoyl-4-hydroxysphinganine (C18-PhCer) were used as controls. Unless otherwise stated, the typical lipid composition was DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid with a 10:6.7:5:5 mol ratio. For fluorescence detection, lipid mixtures were also doped with 0.1 mol % Atto655-DOPE, purchased from ATTO Technology (Siegen, Germany).

First, all lipid stock concentrations were determined in duplicate on a Mettler-Toledo UMX2 ultrabalance (Greifensee, Switzerland) with an accuracy of ±0.1 μg. SUVs were then obtained through bath sonication of multilamellar vesicles. Briefly, the desired lipid mixtures dissolved in choloform:methanol (7:3) were added to a glass vial, and the solvent was then evaporated using N2 flow, followed by vacuum drying in a desiccator. Lipids were rehydrated by adding HEPES buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.4]), reaching a final lipid concentration of 10 mM, and then vigorously vortexed forming a suspension of multilamellar vesicles. These were then diluted to 1 mM with HEPES buffer and sonicated in an ultrasonic bath for 10–20 min until the suspension became clear, giving rise to SUVs.

SLBs were prepared by deposition and fusion of SUVs on top of freshly-cleaved mica glued on a borosilicate coverglass, as described elsewhere (39). Shortly, SUV suspensions (at 1 mM lipid concentration) were deposited in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 on freshly cleaved mica. The samples were then incubated for 20 min at 65°C, rinsed with HEPES buffer, and allowed to slowly cool down to room temperature for at least 1 h.

UV-visible (UV-vis) spectral and size characterization of vesicles with azo-sphingolipids

The mean number-normalized diameters and monodispersity of the formed SUVs were checked via dynamic light scattering using a Zetasizer Nano ZSP (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK), with an incident wavelength of 633 nm and a backscatter detection angle of 173°. Measurements were performed at 25°C and a total lipid concentration of 100 μM using disposable polystyrene cuvettes and a thermal equilibration time of 2 min.

UV-vis spectra of the various azo-sphingolipids embedded within SUVs were collected with Hellma SUPRASIL precision quartz cuvettes (10 mm light path) on a Jasco V-650 spectrophotometer (Tokyo, Japan) before and after illumination with UV-A or blue lights. More precisely, SUV suspensions at 150 μM lipid concentration, composed of DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid (10:6.7:7:3 mol ratio), were here utilized.

Because of the high polydispersity of the SUVs (Fig. S1), we also examined the UV-vis spectra of extruded large unilamellar vesicles with a DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid composition (10:6.7:5:5 mol ratio). These samples were then solubilized with 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 to eliminate the contribution of scattering and to more easily detect a possible shift in the main azobenzene peak. Extrusion was performed on an Avestin Lipofast extruder (Ottawa, Canada) by passing the multilamellar vesicle suspensions 21 times through polycarbonate membrane filters with 100 nm pore size.

Laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy was performed on a Zeiss LSM510 Meta laser scanning microscope (Jena, Germany) using a water immersion objective (C-Apochromat, 40 × 1.2 W UV-VIS-IR). Samples were excited with the 633 nm line of a He-Ne laser for Atto655 excitation. Images were typically recorded with 1 Airy unit pinhole and 512 × 512 pixel resolution. Image analysis was performed using Fiji software (http://fiji.sc/Fiji).

Segmentation methods

In order to quantify the lipid domain (Lo phase), the confocal data were processed by a custom-made MATLAB script for batch processing. The algorithm performs basic segmentation operations based on thresholding (Otsu’s method), morphological erosion, and dilation operations. The output is an image in Portable Network Graphic format of the positive mask of the dark regions corresponding to the lipid domains and a text file containing the calculated area ratio of the domains for each image.

AFM and force spectroscopy

AFM was performed on a JPK Instruments Nanowizard Ultra (Berlin, Germany) mounted on the Zeiss LSM510 Meta laser scanning confocal microscope (Jena, Germany). High-speed and normal-speed AFM, both in AC mode, were done with USC-F0.3-k0.3 ultrashort cantilevers from Nanoworld (Neuchâtel, Switzerland) with typical stiffness of 0.3 N/m. The cantilever oscillation was tuned to a frequency of 100–150 kHz, and the amplitude was kept below 10 nm. Images were acquired with a typical 256 × 256 pixel resolution. Scan rate was set to 12.5–150 Hz for high-speed AFM (i.e., line acquisition taking 6.7–80 ms and full frames 1.7–20.5 s) and to 2–6 Hz for normal-speed AFM. All measurements were performed at room temperature. The force applied on the sample was minimized by continuously adjusting the set point and gain during imaging. Height, error, deflection, and phase-shift signals were recorded, and images were line fitted as required. Data were analyzed using JPK data processing software v.6.0.55 (JPK Instruments) and Gwyddion v.2.49 (Czech Metrology Institute, Jihlava, Czechia).

Line tension (γ) was determined as previously reported (52) using the equation by Cohen and co-workers (53):

| (1) |

with δ being the Ld-Lo height mismatch; h the monolayer thickness with ho = (hr + hs)/2; B the elastic splay modulus; K the tilt modulus; and J the spontaneous curvature of the monolayer. Herein, the subscripts r and s refer to the Lo (rigid) and Ld (soft) membrane phases, respectively. For calculating the effective heights, we used the height mismatches obtained for the various samples and considered a thickness of the Ld bilayer of 3.9 nm, as measured in Fig. S7. Finally, as described by Cohen and co-workers (53) and García-Sáez et al. (52), and since the values of the elastic moduli of the model here employed are unknown, we assumed the case of flexible/soft “raft” domains with Br = Bs = 10 kBT, Kr = Ks = 40 mN/m, and Jr = Js = 0.

Force spectroscopy measurements were performed using uncoated silicon cantilevers CSC38 from MikroMasch (Tallinn, Estonia), with a spring constant of 0.12 N/m, as previously described (54,55). Shortly, sensitivity and spring constant calibration were done via the thermal noise method. The total z-piezo displacement was then set to 300 nm, the indenting approach speed was set to 800 nm/s, the retraction speed was 200 nm/s, and the maximal setpoint was set to 5–7 nN. Force measurements were carried out at different points of the lipid bilayers. An average of 200 and 900 approach force curves per illumination state were, respectively, acquired for DOPC:Chol:Azo-THP-SM (10:6.7:10 mol ratio) and DOPC:Chol:Azo-Cer (10:6.7:10 mol ratio) SLBs. The collected curves were then baseline subtracted (offset and tilt) and corrected for cantilever bending using the JPK data processing software v.6.0.55 (JPK Instruments). Identification of the breakthrough events (and respective force values) was done using the step fit, offset, and statistical quantification functions on the JPK data processing software. Finally, the retrieved yield forces were plotted as histograms using OriginPro2015 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

Compound switching on SUVs and SLBs

Photoswitching of the photolipid compounds was achieved using a CoolLED pE-2 LED light source (Andover, UK) for illumination at λ = 365 and 470 nm. The light source was typically operated for ∼20 s at 80% power. For the UV-vis spectroscopic experiments with SUVs inside cuvettes, the light beam was guided by a fiber-optic cable directly to the cuvette top. For microscopic experiments, the light beam was guided by an optical fiber directly through the objective of the LSM510 Meta microscope via a collimator at the backport.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the collected AFM and confocal microscopy data was performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni comparison tests (95% confidence interval), using SigmaPlot 12.3 (Systat Software, Chicago, IL, USA). Tables showing the data information (mean, standard deviation, and sample size), as well as the recovered t statistics and p values can be found in the supporting material.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of photoswitchable sphingolipids

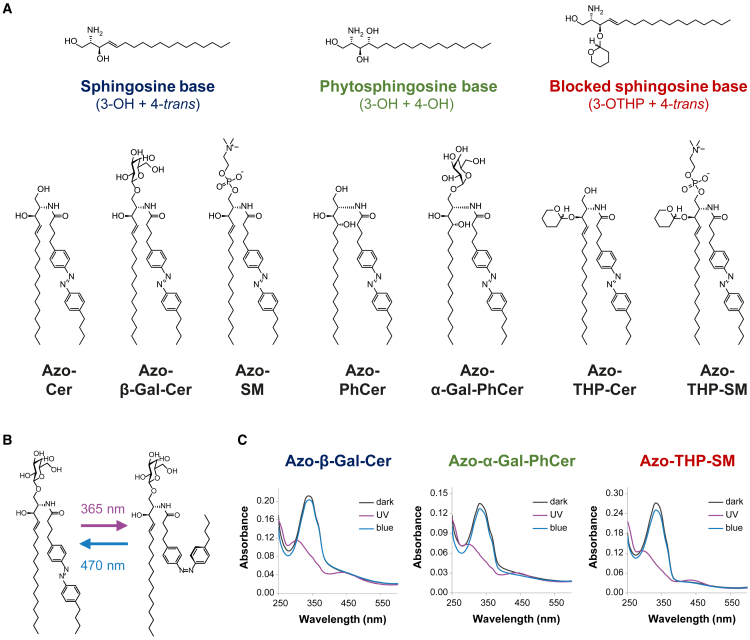

Inspired by the structural design of our simpler azo-Cers (ACes) (39) and more complex α-galactosyl-phytoceramides (40), we introduced five new azobenzene-modified sphingolipids, namely Azo-PhCer, Azo-THP-Cer, Azo-β-Gal-Cer, Azo-SM, and Azo-THP-SM. These photolipids featured (Fig. 1 A) 1) a FAAzo-4 fatty acid (37) at the N-acyl chain (equivalent to a Δ9 unsaturation when in the cis-isoform) and 2) sphingoid backbones based on naturally occurring sphingosine and phytosphingosine or hydroxyl-blocked sphingosine with a THP protecting group, as well as 3) lipid headgroups presenting either a free –OH, galactosyl, or phosphocholine moiety. For our comparative studies, Azo-Cer (previously named ACe-1) (39) and Azo-α-Gal-PhCer (40) (previously named GalACer-4), having the same FAAzo-4 moiety able to undergo trans-cis photoisomerization (Fig. 1 B), were also assessed.

Figure 1.

Structural and spectral properties of photoswitchable azo-sphingolipids. (A) Chemical structures of the N-acyl azobenzene-modified (FAazo-4 fatty acid) sphingolipids here tested, subdivided according to their sphingoid backbone: Azo-Cer, Azo-β-Gal-Cer, and Azo-SM with a sphingosine base and Azo-PhCer and Azo-α-Gal-PhCer with a phytosphingosine base, as well as Azo-THP-Cer and Azo-THP-SM displaying a 3-OH-blocked sphingosine base with a THP protecting group. (B) Schematics of light-induced trans-cis isomerization for an azo-sphingolipid, notably Azo-β-Gal-Cer. Application of UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) leads to the formation of a cis-photolipid, while illumination with blue light (λ = 470 nm) leads to the formation of a trans-photolipid. (C) UV-vis absorbance spectra of photoswitchable sphingolipids (notably Azo-β-Gal-Cer, Azo-α-Gal-PhCer, and Azo-THP-SM) incorporated in SUVs at the dark-adapted state (black curves), as well as after the sequential shining of UV-A (purple curves) and blue light (blue curves). To see this figure in color, go online.

The synthesis and characterization of Azo-Cer and Azo-α-Gal-PhCer were reported elsewhere (39,40). Azo-PhCer was prepared analogously to Azo-Cer by the coupling of phytoceramide with FAAzo-4 using HBTU as a coupling agent (see supporting material). Additional protecting group manipulations yielded Azo-THP-Cer.

For the synthesis of Azo-β-Gal-Cer, we used a benzoyl protected alcohol and the azide as protecting groups (56) (see supporting material). Azides do not coordinate to the primary alcohol, and thereby the nucleophilicity of the sphingosine is greatly enhanced. Glycosylation of azidosphingosine with trichloroacetimidate yielded protected glycoside in 92% yield and excellent β-selectivity. Staudinger reduction using PBu3 and subsequent amide coupling with FAAzo-4 (37) using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide, followed by global deprotection gave Azo-β-Gal-Cer (see supporting material).

The SM derivatives were prepared from Azo-THP-Cer, which was phosphorylated using 2-cyanoethyl-N,N,N′,N′-tetraisopropylphosphorodiamidite and 1H-tetrazole, followed by reaction with choline tosylate (see supporting material). An oxidation directly yielded Azo-THP-SM. Finally, deprotection under acidic conditions gave the unprotected Azo-SM (see supporting material).

Light responsiveness of membrane-embedded azo-sphingolipids

Next, we incorporated our newly synthesized Azo-β-Gal-Cer, Azo-SM, Azo-PhCer, Azo-THP-SM, and Azo-THP-Cer photolipids, as well as Azo-Cer and Azo-α-Gal-PhCer, into Ld-Lo phase-separated mixtures containing DOPC, Chol, and SM (18:0-SM) and formed SUVs as previously described (39,57). Unless otherwise stated, a molar ratio of 10:6.7:5:5 (DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid) was typically chosen.

We started with dynamic light scattering to determine the typical size and monodispersity of the sonicated SUVs. As shown in Fig. S1, the average number-normalized diameters were between 40 and 60 nm. Then, we collected UV-vis spectra of those various SUV suspensions and characterized the photodynamic properties of the different azobenzene-modified sphingolipids within a membrane environment. As seen in Figs. 1 C and S2 (see supporting material), the azo-sphingolipids displayed an absorbance maximum, λmax, at ∼340 nm when in the dark-adapted state prior to irradiation with UV-A or blue light. This peak corresponds to the π → π∗ transition and is characteristic for the trans-azobenzene isoform. First illumination with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) led to the reduction of the abovementioned absorbance peak and to the appearance of a new λmax at ∼450 nm. This new peak corresponds to the n → π∗ transition and is characteristic for the cis-azobenzene isoform. Subsequent irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) led then to a back isomerization of the N-acyl azobenzene moieties into the trans-isoform, as confirmed by the disappearance of the absorbance peak at ∼450 nm and the reemergence of the absorbance peak at ∼340 nm.

Our results indicate that the tested photoswitchable sphingolipids are in the trans-configuration for the dark- and blue light-adapted states and are mostly in cis-configuration for the UV light-adapted state. To infer if significant spectral shifts occur due to headgroup functionality and sphingoid polarity, we performed additional experiments examining the UV-vis spectra of extruded large unilamellar vesicles with a DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid composition (10:6.7:5:5 mol ratio), followed by solubilization with 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 to eliminate the contribution of scattering. When we normalize the spectral maxima (Fig. S2 E), we find a stronger spectral red shift of ∼7 nm for the blocked THP photolipids (maximum 338 nm) compared with the azo-sphingolipids and azo-phytosphingolipids (maximum 331 nm). Thus, it appears that the presence of the THP moiety only slightly affects the spectral azobenzene properties of our photolipids.

Subsequently, we deposited SUVs composed of quaternary DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid mixtures doped with 0.1 mol % Atto655-DOPE (dye labeling the Ld regions) on top of freshly cleaved mica to form SLBs via vesicle fusion. By collecting fluorescence confocal images, we first evaluated membrane integrity and the presence of phase separation for samples having sphingosine- (Azo-Cer, Azo-β-GalCer, Azo-SM), phytosphingosine- (Azo-PhCer, Azo-α-GalPhCer), and blocked THP-sphingosine-based (Azo-THP-SM) lipids. As seen in Figs. S3 and S4, all tested SLBs displayed Ld-Lo phase separation at the dark-adapted state, with μm-sized rigid Lo domains (dark areas in fluorescence images) segregated within a fluid Ld matrix (red areas in fluorescence images).

The photoresponsiveness and ability of the azo-sphingolipids to then remodel/reorganize phase-separated SLBs were further assessed directly after irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm). For membranes lacking a photolipid (control sample with a DOPC:Chol:SM composition at a mol ratio 10:6.7:10), no light-induced remodeling was observed (Fig. S3 A). In contrast, for SLBs containing azo-sphingolipids, stark lipid rearrangement dependent on the amount of photolipid present was reported. Here, lipid bilayers with the highest amount of azo-sphingolipid tested (18.7 mol %; DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid with mol ratio 10:6.7:5:5) showed strong reorganization of the Lo domains with admixing of fluorescently marked Ld lipids and blurring of the domain boundaries directly after UV-A irradiation (Fig. S3, B–G). Intermediate amounts of photolipid (11.2 mol %; DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid with mol ratio 10:6.7:7:3) led to a lower domain remodeling activity. Finally, for SLBs with the lowest amount of azo-sphingolipid tested (3.7 mol %; DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid with mol ratio 10:6.7:9:1), only a minor admixing of Ld-Lo domains was observed (Fig. S4). Thus, the higher the concentration of azo-sphingolipids on the membranes, the stronger the reorganization of the phase-separated domains directly after UV-triggered photoisomerization of the N-azobenzene acyl chain of lipids into cis. Specifically, the observed mixing of the Ld marker from the highly fluorescent Ld matrix regions to the nonfluorescent Lo domain regions is evidence that lipid content is exchanged between the two domains immediately after UV illumination. To be precise, this phenomenon hints that the membrane gets “fluidified” once the photolipids are switched, as Ld-localizing lipids appear to “populate” (i.e., diffuse into) the more rigid Lo domains.

Remodeling of membrane domains by sphingosine-based azo-sphingolipids

After the initial characterization and screening mentioned above, we systematically investigated the light-induced remodeling of phase-separated supported membranes with 18.7 mol % photolipid (DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid, 10:6.7:5:5 mol ratio) by first performing high-speed AFM to gain more insight into the activity of the photolipids. AFM enables us to capture minor dynamic changes in membrane architecture very accurately due to its exquisite sub-nm resolution. Herein, we started by analyzing bilayers containing the sphingosine-based photolipids Azo-Cer, Azo-β-GalCer, and Azo-SM.

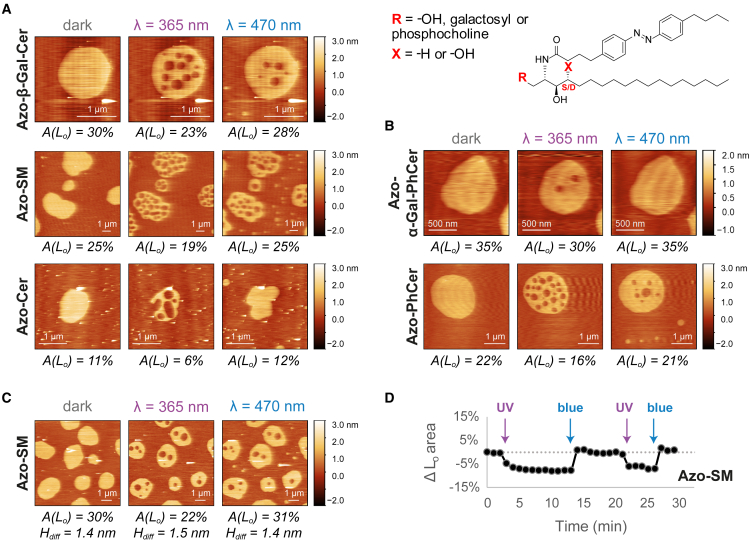

At the dark-adapted state, those various membranes displayed a height mismatch between the Ld and Lo regions of 1.1–1.7 nm, similar to what we reported before for phase-separated bilayers with Azo-Cer (ACes) lipids (39). Application of UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) to bilayers having Azo-Cer, Azo-β-GalCer, or Azo-SM led then to the generation of an Ld phase, with no major alteration of the Ld-Lo domain height mismatch (i.e., minor increase of ∼0.1 nm).

As seen from single images in Figs. 2 A and S5 B and Videos S1, S2, S3, S4, S10, S11, and S12, the UV-induced isomerization of the N-acyl chains from a straight trans-form into a kinked cis-form promoted an apparent “fluidization” of the phase-separated membranes, with an overall robust decrease of the total Lo area for all three azo-sphingolipids (Fig. S6 C). Directly after irradiation with UV-A light, small nanoscopic Ld “lakes” were formed within the more rigid, thicker Lo domains, consistent with the influx of Ld markers into the Lo regions observed in Fig. S3. Because the height of the Lo domains is largely unaffected by the isomerization of these photolipids in cis, the nanoscopic Ld lakes detected by AFM may be the reservoirs into which the fluorescent Ld markers distribute immediately after photoisomerization. These membrane nanopockets with diameters below the diffraction limit would be poorly resolved in fluorescence microscopy, which explains the fluorescently smeared appearance of the Lo regions when detected under the confocal microscope (Figs. S3 and S4).

Figure 2.

Lateral remodeling of phase-separated membranes containing nonblocked azo-sphingolipids upon light trigger analyzed by high-speed AFM. (A and B) Changes in the area of Lo domains (of depicted snapshots) before/after illumination with UV-A (λ = 365 nm) and blue (λ = 470 nm) lights on DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid (10:6.7:5:5 mol ratio) SLBs having (A) Azo-β-Gal-Cer (see Video S1), Azo-SM (see Video S2), or Azo-Cer (see Video S3) with a sphingosine backbone (X = –H) and varying headgroup functionality (R = galactosyl, phosphocholine, or –OH, respectively) or (B) Azo-α-Gal-PhCer (see Video S5) or Azo-PhCer (see Video S6) with a phytosphingosine backbone (X = –OH) and varying headgroup functionality (R = galactosyl or –OH, respectively). (C and D) Reversible lateral remodeling of a phase-separated SLB containing Azo-SM (DOPC:Chol:SM:Azo-SM; 10:6.7:5:5 mol ratio) upon UV-A/blue light irradiation, as seen in Video S4. (C) AFM images of the SLB at the dark-, UV-, and blue light-adapted states, displaying the area occupied by the Lo phase and the Ld-Lo height mismatches. (D) Relative variation of total Lo area of the SLB over time, shown in Video S4, upon shining short pulses (marked with arrows) of UV-A and blue light. To see this figure in color, go online.

The number of fluid Ld lakes then rapidly dropped in order to reduce surface tension. While the majority of the smaller nanoscopic Ld lakes seem to vanish toward the outer fluid Ld matrix, a few larger fluid Ld lakes remained trapped inside rigid Lo domains, appearing to grow primarily via domain fusion and/or Ostwald ripening (58). Finally, if all the high-speed AFM area values (Figs. 2, A and C, and S5 B; n = 7) for this class of photolipids are grouped, an average Lo area decrease of ∼25% (area Lo(UV)/area Lo(dark) = 0.75 ± 0.14) can be estimated, as depicted in Fig. S6.

After a few minutes of equilibration, subsequent application of a brief pulse of blue light (λ = 470 nm) to those phase-separated membranes reversed the effect, with an Lo phase being generated. Here, back isomerization of the N-acyl chains from a kinked cis-form into a straight trans-form, stimulated by blue light, promoted a rigidification of the membranes (Figs. 2 A and S5 B), with an increase of the total Lo area (Fig. S5 C) back to its original equilibrium dark-adapted value (area Lo(blue)/area Lo(dark) = 1.01 ± 0.18; from grouped high-speed AFM area values in Fig. S6). More specifically, upon irradiation with blue light, small rigid Lo “islands” were firstly formed within the fluid Ld matrix (Videos S1, S2, S3, S4, S10, S11, S12, and S13). These taller Lo islands then vanished, as preexisting Lo domains grew primarily via Ostwald ripening and domain fusion. Moreover, Lo domains displayed height values like the ones reported before for the initial dark-adapted state. Interestingly, those changes could be repeated over multiple cycles without dissipation effects, with the amount of Ld-Lo phase separation alternating between two defined steady states (or area levels) (Fig. 2, C and D).

Besides changes in Ld-Lo phase separation, we also observed sporadic generation of holes on our supported bilayers after the blue light-triggered conversion of the azo-sphingolipids’ N-acyl chains from cis to trans (Fig. S7 A). The presence of holes allowed us to recover the total membrane thickness, which was ∼5.2 nm (Ld thickness ∼3.9 nm; Fig. S7, B and C), in agreement with previously reported values for membranes of comparable lipid composition (59,60,61).

In summary, the tested azo-sphingolipids with a sphingosine backbone display a similar photoswitching profile independently of the type of headgroup. These lipids are able to increase the amount of Ld phase on phase-separated membranes upon conversion to the cis-isoform after UV-A light irradiation and increase the amount of Lo phase upon conversion to the trans-isoform after irradiation with blue light.

Remodeling of membrane domains by phytosphingosine-based azo-sphingolipids

Next, we recapitulated the same high-speed AFM procedures on membranes with photoswitchable phytosphingosine-based sphingolipids displaying two hydroxyl groups (3-OH + 4-OH) on the phytosphingosine backbone. More precisely, we investigated the ability of these photolipids to interfere with the Ld-Lo phase separation on SLBs when compared with sphingosine-based lipids having only one hydroxyl (3-OH) on their backbone.

In the dark-adapted state, phase-separated DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid SLBs with Azo-PhCer and Azo-α-Gal-PhCer exhibited a domain height mismatch of 1.2–1.8 nm (Figs. 2 B and S5 C), very close to the Ld-Lo height differences here reported for membranes with sphingosine analogs (Figs. 2 A and S5 B). Upon photoactivation, the Ld-Lo phase-separated SLBs containing either Azo-PhCer (with a hydroxyl headgroup) or Azo-α-Gal-PhCer (with a bulkier galactosyl headgroup) behaved in a similar way to membranes with sphingosine-based azo-sphingolipids by exhibiting, at the end, an identical phenotype of membrane remodeling (Fig. S6 C).

As seen in Figs. 2 B and S5 C and Videos S6, S7, S13, S14, and S15, after irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm), Ld lakes initially appeared inside existing Lo domains, and the total Ld phase membrane area lowered by ∼23% (area Lo(UV)/area Lo(dark) = 0.78 ± 0.18, from grouped high-speed AFM area values in Fig. S6, extracted from Figs. 2 B and S5 C; n = 5), while the domain height mismatch did not change majorly. Then, after irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm), Lo islands initially formed inside the Ld regions, and the total Lo phase membrane area subsequently increased to the initial equilibrium dark-adapted values (area Lo(blue)/area Lo(dark) = 1.03 ± 0.20, from grouped high-speed AFM area values in Fig. S6).

Our results confirm that the bulkiness of the neutral headgroup does not play a role in the membrane remodeling ability of our photoswitchable phytosphingolipids. Moreover, the increased backbone polarity of the phytosphingosine backbone does not seem to affect the way azo-phytosphingolipids engage in interactions with their neighboring lipids when compared with azo-sphingolipids. Hereby, we conclude that the tested Azo-Cer, Azo-β-GalCer, Azo-SM, Azo-α-Gal-PhCer, and Azo-PhCer establish stable interactions with other sphingolipids (such as SM) and sterols (such as Chol) inside Lo domains when their azobenzene acyl chain is in the trans-isoform (imitating a “straight” saturated acyl chain) and with unsaturated phosphatidylcholines (e.g., DOPC) inside Ld regions when the azobenzene is in the cis-isoform (mimicking a “bent” unsaturated chain).

It is worth noting that the normalized extent of Lo domain area changes produced by trans-cis isomerization of the N-acyl azobenzene chain in these two classes of photolipids (Fig. S6 C) appears to be robust and independent of domain size, scanned area dimensions, and different Lo phase surfaces scanned locally (Figs. 2, 3, and S5). A direct comparison of all AFM time lapses (Videos S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9, S10, S11, S12, S13, S14, S15, S16, and S17) also shows that it is difficult to assign whether the contribution of Ostwald ripening or domain fusion to the restructuring of Ld lakes is different for each photolipid type. This was particularly evident in membranes containing Azo-α-Gal-PhCer and Azo-Cer (with completely different backbones and headgroups), where some of the bilayers appeared to show a more rapid remodeling and domain fusion-based mechanism of the Ld lakes upon UV irradiation, while in other bilayers/areas, the remodeling/expulsion of the Ld lakes trapped inside Lo domains appeared to occur slowly by Ostwald ripening (for Azo-Cer, see Videos S3 and S12; for Azo-α-Gal-PhCer, see Videos S5, S13, and S14).

Figure 3.

Lateral remodeling of phase-separated membranes containing 3-OH-blocked azo-sphingolipids upon light trigger analyzed by high-speed AFM. (A) Changes in the area of Lo domains (of depicted snapshots) before/after illumination with UV-A (λ = 365 nm) and blue (λ = 470 nm) lights on DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid (10:6.7:5:5 mol ratio) SLBs having Azo-THP-SM (see Video S7) or Azo-THP-Cer (see Video S8) with a 3-OH-blocked (THP-protected) sphingosine backbone and varying headgroup functionality (R = phosphocholine or –OH, respectively). (B and C) Reversible lateral remodeling of a phase-separated SLB with Azo-THP-SM (DOPC:Chol:SM:Azo-THP-SM; 10:6.7:5:5 mol ratio) upon UV-A/blue light irradiation, as seen in Video S9. (B) AFM images of the SLB at the dark-, UV-, and blue light-adapted states, displaying the area occupied by the Lo phase and the Ld-Lo height mismatches. (C) Relative variation of total Lo area of the SLB over time, shown in Video S9, upon shining short pulses (marked with arrows) of UV-A and blue light. To see this figure in color, go online.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-β-GalCer upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-β-GalCer upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 3.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-SM upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-SM upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 16.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-Cer upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-Cer upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 5.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-SM upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-SM upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 20.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps. Quantification of the variation in Lo area is depicted in Fig. 2 D.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-α-Gal-PhCer upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-α-Gal-PhCer upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 4.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-PhCer upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-PhCer upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 5.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to phase signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-THP-SM upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-THP-SM upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 4.1 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-THP-Cer upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-THP-Cer upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 16.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-THP-SM upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-THP-SM upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 20.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps. Quantification of the variation in Lo area is depicted in Fig. 3 C.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-β-GalCer upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-β-GalCer upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 6.5 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-SM upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-SM upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 3.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-Cer upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-Cer upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 2.5 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-α-Gal-PhCer upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-α-Gal-PhCer upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 5.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-α-Gal-PhCer upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-α-Gal-PhCer upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 5.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-PhCer upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-PhCer upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 5.2 s/frame. Video frame rate = 5.2 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-THP-SM upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-THP-SM upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 10.1 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

Images correspond to height signal. Initial dark-adapted state is marked with a gray circle. Isomerization to cis-Azo-THP-Cer upon irradiation with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) is marked with a purple circle. Isomerization back to trans-Azo-THP-Cer upon irradiation with blue light (λ = 470 nm) is marked with a blue circle. Acquisition = 8.1 s/frame. Video frame rate = 11 fps.

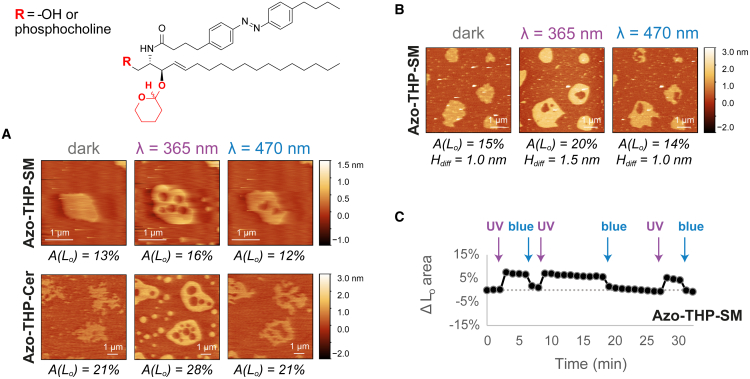

Remodeling of membrane domains by 3-OH-blocked azo-sphingolipids

In order to infer the exact role of H-bonding and sphingoid base polarity for the mode of action of azo-sphingolipids, we used high-speed AFM to further investigate the photoswitching and lateral membrane remodeling activities of the azo-sphingolipids Azo-THP-Cer and Azo-THP-SM. These lipids have the 3-OH group on their sphingosine backbone protected with a bulky THP moiety. Notably, the final protecting step resulted in an inseparable mixture of diastereomers at the THP linkage (see Fig. 3), which was used in all experiments.

In the dark-adapted trans-form, DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid bilayers containing 3-OH-blocked Azo-THP-SM or Azo-THP-Cer (Figs. 3 and S5 D; Videos S7, S8, S9, S16, and S17) had Lo domains with irregular borders and lower heights (∼0.6–0.9 nm) when compared with SLBs with nonblocked counterparts (Fig. 2). Such a noticeable effect on the global architecture of Lo domains is evidence that 3-OH-blocked lipids are able to reduce the molecular packing within the Lo phase, as previously reported for 3-OH-blocked stearoyl-SM (29,62).

When the membranes with THP-protected photolipids were irradiated with UV-A light (λ = 365 nm) and the lipids converted to the cis-isoform, the total area of Lo phase markedly increased ∼23% (area Lo(UV)/area Lo(dark) = 1.23 ± 0.21, from grouped high-speed AFM area values in Fig. S6, extracted from Figs. 3 and S5 D; n = 5), with Lo domains getting larger, rounder, and noticeably higher (∼1.1–1.4 nm) (Fig. 3, A and B). Quite strikingly, directly after exposure to UV-A light, Ld lakes inside preexisting Lo domains, as well Lo islands within the Ld matrix were transiently formed. The preexisting Lo domains then grew in total area, mainly via Ostwald ripening as Lo islands disappeared, whereas only a few larger Ld lakes appeared at the end trapped inside the enlarged Lo domains.

Subsequent illumination with blue light (λ = 470 nm) led to an overall decrease of both total Ld-Lo height mismatch and Lo area back to the initial dark-adapted state values (area Lo(blue)/area Lo(dark) = 0.98 ± 0.20, Fig. S6), as the 3-OH-blocked photolipids isomerized back to the trans-isoform. Interestingly, no noticeable formation of large Ld lakes or Lo islands was observed here. The Lo domains rapidly shrank with their domain borders becoming irregular (less rounded) and more unstable, as large rapid fluctuations were visible (Videos S7, S8, S9, S16, and S17). This clearly indicates that the THP-protected azo-sphingolipids, when in the trans-isoform, severely affect line tension of the phase-separated domains. Finally, the reported Lo domain height and area changes within the phase-separated bilayers could be repeated over multiple illumination cycles, as seen in Fig. 3 C and Videos S7, S8, S9, S16, and S17.

To sum up, photoswitchable sphingolipids having their 3-OH sphingoid moiety blocked with a THP group promote a clearly distinct light-induced reorganization of Ld-Lo phase-separated membranes when compared with nonblocked counterparts. These blocked lipids are able to significantly increase the percentual amount and height of the Lo phase upon UV-triggered isomerization to the cis-isoform and to decrease both these parameters upon blue light-triggered isomerization to the trans-isoform. Moreover, the formation of Ld lakes and Lo islands only after the application of UV light (and not blue light) suggests an altered distribution profile of these photolipids within the Ld and Lo phases when compared with nonblocked photolipids.

Phase-separation area changes by photoswitchable sphingolipids

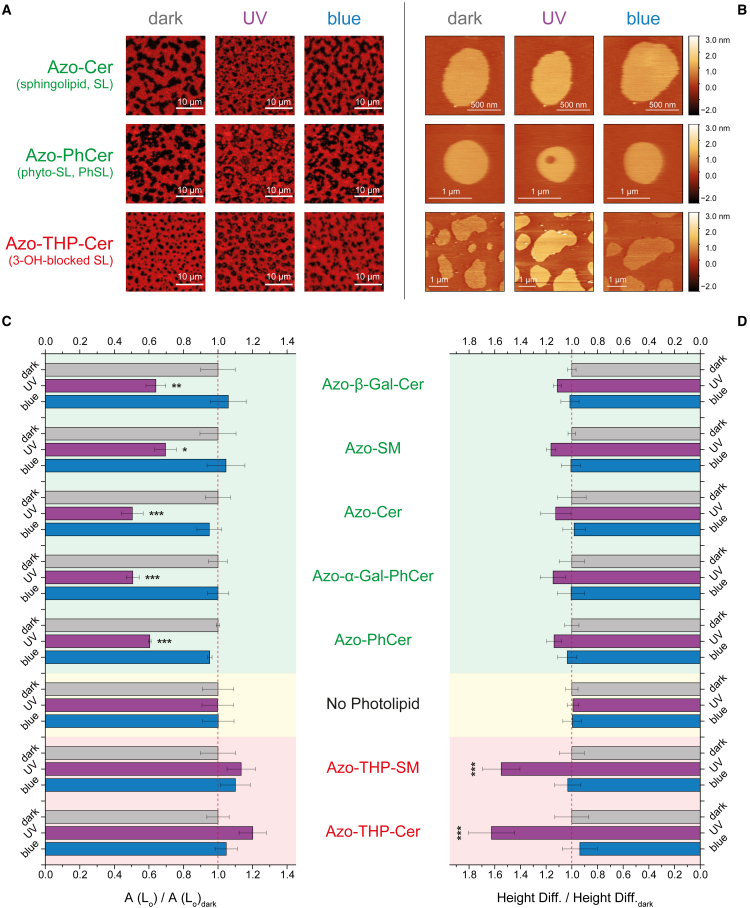

After demonstrating that the various nonblocked versus hydroxyl-blocked photoswitchable sphingolipids reorganize phase-separated membranes differently, we set out to quantitatively compare the extent by which these lipids alter the total distribution of phase separation, as well as other structural membrane parameters.

To begin, since AFM only allows us to follow a limited number of Lo domains simultaneously, we acquired additional large field-of-view fluorescence confocal images (Figs. S8, S9 A, and 4 A) to obtain better statistics for determining ensemble area values independent of domain size and number. We analyzed changes in Lo total area before/after UV/blue irradiation on DOPC:Chol:SM control SLBs (n = 5 images) and, most importantly, DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid SLBs containing 18.7 mol % Azo-Cer, Azo-β-GalCer, Azo-SM, Azo-PhCer, Azo-α-GalPhCer, Azo-THP-Cer, or Azo-THP-SM (number of images per photolipid, n = 5–8) doped with 0.1 mol % Atto655-DOPE for fluorescent detection of the Ld phase.

Figure 4.

Normalized changes in the total Lo phase area and Ld-Lo height difference on phase-separated SLBs having different types of azo-sphingolipids upon application of UV-A (λ = 365 nm) and blue (λ = 470 nm) lights. Fluorescence confocal (A) and AFM (B) images of DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid (10:6.7:5:5 mol ratio) SLBs with sphingosine-based Azo-Cer, phytosphingosine-based Azo-PhCer, or 3-OH-blocked sphingosine-based Azo-THP-Cer, all having the same –OH headgroup but distinct sphingoid backbone. Normalized Lo areas (C) and Ld-Lo height differences (D), respectively, recovered from fluorescence confocal and AFM data for phase-separated SLBs having either azo-(phyto)sphingolipids with free 3-OH (marked in green), no azo-sphingolipid (controls with SM, marked in yellow), or THP-protected azo-sphingolipids with the 3-OH blocked (marked in red). Error bars correspond to standard error of the mean (n = 5–8 confocal images each). Statistical analysis: cis-photolipids versus no photolipid (∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.005, ∗p < 0.05). See Figs. S9 and S11 for details. To see this figure in color, go online.

Usage of fluorescence allowed us to easily generate binary masks (Fig. S8), from which Lo phase areas could be straightforwardly estimated. Instead of collecting the confocal images immediately after photoisomerization (Fig. S3), which would have been smeared due to the short-lived nanoscopic Ld lakes, we let the SLBs equilibrate here for 20 min after brief irradiation with UV/blue light. In this way, we were able to reduce the number of hard-to-resolve Ld lakes and Lo islands and obtained a clearer macroscopic Ld-Lo phase separation (Figs. 4 A and S9 A).

All average absolute Lo area values recovered for the various SLBs are shown in Fig. S9 B. These values are particularly important as a way to assess the extent of membrane phase-separation perturbation caused by the presence of trans-photolipids prior to photoactivation. Briefly, control membranes without photolipids (DOPC:Chol:SM 10:6.7:10 mol ratio) displayed a total surface coverage by Lo domains of 45%. A similar average value of 45% ± 4% was obtained for membranes with 18.7 mol % nonblocked photolipids in trans. Only the SLBs with THP-protected trans-photolipids showed significantly lower total Lo domain coverage, about 29% ± 3% (p < 0.001), when compared with the control membranes without photolipids. This large reduction in total Lo area for membranes with hydroxyl-protected azo-sphingolipids clearly supports our AFM observation that THP-blocked trans-photolipids affect Lo phase properties.

To facilitate data comparison for the photoswitchable conversion of phase separation by our photolipids, the recovered Lo areas were normalized before/after UV/blue light illumination by the average Lo area for the different individual SLBs at the dark-adapted state (Fig. 4 C). This allowed us to analyze the relative changes in the total Lo area (for cis- and trans-photolipids) and compare it with the behavior of the DOPC:Chol:SM control lipid samples without photolipids (Fig. 4 C). Relevant statistical comparisons were then performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni comparison t-tests (95% confidence interval), and the respective t statistics and p values are listed as supporting material in Table S3.

As seen in Figs. 4 C and S9 B, the total Lo area for phase-separated SLBs having sphingosine- or phytosphingosine-based photolipids significantly decreased (with p values between p < 0.05 and p < 0.001) on average by 41% (area Lo(UV)/area Lo(dark) = 0.59 ± 0.04) after UV-A illumination (when the lipids are in cis) and augmented back to the original dark-adapted state (area Lo(blue)/area Lo(dark) = 1.00 ± 0.02) upon blue light irradiation (when the lipids are in trans). For SLBs having Azo-THP-SM or Azo-THP-Cer, on the contrary, the total area of the Lo phase did not statistically change (p > 0.05) when compared with control membranes without a photolipid. Here, only a slight increase by 17% (area Lo(UV)/area Lo(dark) = 1.17 ± 0.03) after illumination with UV-A light is seen, while the recorded amount of Lo phase decreased back to the original dark-adapted state value (area Lo(blue)/area Lo(dark) = 1.07 ± 0.03) after the application of a blue light pulse.

Interestingly, if we compare the changes in Lo area after azo-sphingolipid photoisomerization determined by fluorescence (Figs. 4 C and S9) versus high-speed AFM data (Fig. S6), the area changes for confocal microscopy seem to be skewed toward detecting higher amounts of Ld phase after UV irradiation. This skew may be a direct consequence of the limited pixel resolution of conventional laser-scanning confocal microscopy for detecting nanoscale Lo domains when compared with AFM. Despite this instrumental bias, similar trends in membrane domain area variations were detected with both fluorescence confocal and AFM techniques.

These experiments corroborate that sphingosine- and phytosphingosine-based photolipids rely on the same principles for reshuffling membrane phase-separated domains, whereas the THP-protected counterparts, owing to their distinct physicochemical properties, follow a markedly different mechanism. Finally, although there is no statistical difference between the various sphingosine- and phytosphingosine-based cis-photolipids (p = 1), the obtained t statistics for their comparison with the control DOPC:Chol:SM suggest a possible hierarchy. Here, Azo-Cer and the two azo-phytosphingolipids (Azo-α-Gal-PhCer and Azo-PhCer), the latter being able to establish stronger H-bonding interactions, appeared to possess the strongest “remodeling activity” (with p < 0. 001) (see Table S3 for more details).

Domain height mismatch changes by photoswitchable sphingolipids

Our results so far clearly point out that blocking the interfacial hydroxyl on the sphingoid backbone has a marked effect on the molecular organization of individual lipids and on the global architecture of Lo domains. Thus, to quantitatively ascertain how photoswitchable sphingolipids affect the structure and physicochemical properties of Lo domains within phase-separated membranes, we collected zoomed-in and high-resolution low-speed AFM images (n = 5–9) of individual Lo domains on DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid SLBs prior to and 20 min after brief illumination with UV-A/blue light (to let domains equilibrate and reduce the amount of Ld lakes and Lo islands), as depicted in Figs. 4 B, S10, and S11 A. This acquisition mode allows us to follow the membrane contour with an increased signal/noise ratio and therefore determine more accurately the height differences between the Lo domains and the surrounding Ld matrix (Fig. S10). This is an important parameter, as it relates to the hydrophobic mismatch between the saturated (“nonbent” acyl chains) lipids in Lo domains with increased chain order (63) and the unsaturated (bent acyl chains) lipids in less packed Ld regions.

Altogether, the average height difference between Lo and Ld regions (at the dark-adapted state for the various SLBs having either sphingosine- or phytosphingosine-based photolipids) was 1.3 ± 0.1 nm. This value corresponds to the mean of all average Ld-Lo height differences (± standard error) obtained for membranes containing Azo-Cer, Azo-β-GalCer, Azo-SM, Azo-PhCer, or Azo-α-GalPhCer (Fig. S11 B) and was very close to the less precise values previously reported using high-speed AFM. Owing to the exquisite z-resolution of AFM, we also identified that the Lo domains of SLBs having azo-sphingolipids with smaller headgroups (e.g., Azo-Cer and Azo-PhCer) were slightly less elevated (1 ± 0.1 nm) than the Lo domains of SLBs having azo-sphingolipids with larger headgroups (e.g., Azo-SM, Azo-β-GalCer, and Azo-α-GalPhCer). The later-displayed Ld-Lo height mismatches (1.4 ± 0.1 nm) are closer to the values recovered (1.8 ± 0.1 nm) for control ternary mixtures without a photolipid. Hence, our observations corroborate a preferred localization of the trans-azo-sphingolipids inside Lo domains, as these lipids could then engage hydrophobic packing and stable H-bonding interactions with SM and Chol, altering slightly the height of Lo domains due to the different headgroup size and N-acyl chain length (e.g., C18:0 acyl chain: 21.2 Å vs. FAAzo-4: 17.9 Å, retrieved from Chem3D, PerkinElmer, Boston, MA, USA).

Interestingly, upon applying UV-A light to SLBs having these nonblocked photolipids, the Ld-Lo height mismatch increased on average by 14% (1.4 ± 0.1 nm; Fig. 4 D). Although this variation is not statistically relevant, it is in line with the exclusion of cis-azo-sphingolipids from the Lo phase and SM being then the predominant sphingolipid molecule inside those domains. Subsequent irradiation with blue light led to the decrease of the domain height by 13% back to the original values reported for the dark-adapted state (Fig. 4 D), corroborating a repartitioning of trans-azo-sphingolipids back to the Lo phase.

For membranes having hydroxyl-blocked photolipids, the height of Lo domains at the dark-adapted state was lower, and the domain boundaries more irregular, when compared with membranes with nonblocked counterparts. Indeed, the Ld-Lo height mismatch observed for SLBs with Azo-THP-SM or Azo-THP-Cer was below 1 nm (0.7 ± 0.1 nm; Fig. S11 B), similar to the values observed using high-speed AFM and nearly 0.5 and 1.0 nm lower than the height mismatch found for SLBs with Azo-SM or control membranes lacking azo-sphingolipids, respectively. The lower Lo height observed for membranes with 3-OTHP-lipids indeed corroborates that these lipids establish altered interactions with other colipids in the Lo phase when in the trans-isoform but, most importantly, validates that blocking H-bonding severely alters the molecular packing, as well as the line tension within Lo domains.

This destabilization effect can be overcome once the hydroxyl-blocked azo-sphingolipid is converted to its cis-isoform upon illumination with UV-A light. Indeed, after applying UV-A to the phase-separated SLBs with Azo-THP-SM, the Ld-Lo height mismatch significantly increased (p < 0.001) by 55% (Fig. 4 D) to average values above 1 nm (1.1 ± 0.1 nm). This elevation in height suggests that Azo-THP-SM and Azo-THP-Cer lipids are expelled from the Lo phase when in the cis-isoform, leaving the Lo domains mainly composed by SM and Chol. Without the interference of these THP-protected lipids, SM and Chol molecules can then establish more stable H-bonding and tighter hydrophobic chain packing interactions, giving rise to taller, rounder, and larger Lo domains. In opposition, irradiation of the phase-separated SLBs with blue light leads to a marked reduction of the Lo domain height (Fig. 4 D) back to the initial dark-adapted state value (0.7 ± 0.1 nm). As the 3-OH-blocked azo-sphingolipids isomerize back to their trans-isoform, these lipids could then reestablish hydrophobic chain packing interactions with the other Lo-localizing lipids, destabilizing the existing H-bonding interactions between SM and Chol.

Domain line tension changes by photoswitchable sphingolipids

A parameter closely linked to the domain height mismatch is line tension, which can be perceived as the interfacial energy arising at the boundaries of coexisting phases and is an important driving force for membrane shape transformation (e.g., budding (4,64,65) and fusion (66)). In order to estimate the approximate values of line tension for the various Ld-Lo membranes with distinct blocked and nonblocked photoswitchable sphingolipids, based on the height mismatch values measured using low-speed AFM, we used the theoretical model for flexible domains implemented by Cohen and co-workers (Eq. 1). This model describes a quadratic dependence of the line tension with the phase height mismatch (53) and was previously used to estimate line tension on phase-separated membranes with similar lipid compositions (52).

Overall, as seen in Fig. S11 C, line tension values ranged from 1.9 to 4.3 pN for Ld-Lo phase-separated SLBs with sphingosine- and phytosphingosine-based lipids in the trans-isoform. When the lipids are in the cis-isoform and partition to the Ld phase instead, a statistically nonsignificant yet small increase in line tension by 24% (Fig. S12) was recovered, with the values being very close to the ones gauged for phase-separated SLBs lacking azo-sphingolipids (5.4 ± 0.6 pN).

In contrast, Ld-Lo bilayers with THP-protected azo-sphingolipids (such as Azo-THP-SM and Azo-THP-Cer) in the trans-isoform possess noticeably reduced line tension values (∼1.2 pN): 2.2- to 4.5-fold lower than the domain line tension measured for SLBs with nonblocked photolipid counterparts (Fig. S11 C). Next, when the hydroxyl-blocked lipids are in their cis-isoform and locate in the Ld phase, the domain line tension greatly increases (p < 0.001) by ∼120% (Fig. S12), reaching values close to the ones reported for nonblocked counterparts (2.6 pN). Hence, THP-protected photolipids, when in trans, greatly reduce the line tension of Lo domains in opposition to the azo-sphingolipids with free interfacial hydroxyls, appearing to possess additional line-active (lineactant) properties.

Line-active molecules are known to concentrate at the boundaries of membrane phases (67,68,69,70), reducing the hydrophobic mismatch and line tension around phase-separated domains (e.g., Lo versus Ld). Herein, hybrid lipids such as palmitoyl-oleyl-phosphatidylcholine, possessing both a saturated and unsaturated fatty acid chain, are of particular relevance. When added to ternary mixtures made of lipids with two saturated tails (e.g., DPPC or DSPC), two unsaturated tails (DOPC), and a sterol (Chol), palmitoyl-oleyl-phosphatidylcholine was shown to interact with the Lo phase and disturb the chain ordering of Lo domains in a so-called “partitioning and loosening” mechanism (71). Such an effect will then promote the reduction of line tension and formation of nanoscopic domains, hence lowering the differences in physical properties between the Lo and Ld phases (71,72,73,74,75). Interestingly, Azo-THP-SM and Azo-THP-Cer also appear to reduce line tension and promote the formation of nanoscopic domains in a similar way, sharing moreover key structural similarities with hybrid lipids: 1) the trans-azobenzene N-acyl chains mimic saturated fatty acids prone to localize within Lo domains, and 2) the bulky THP moiety at the sphingosine base appears to interfere with the molecular packing of lipids and therefore be susceptible to preferentially localize in the less packed Ld phase.

To sum up, the hybrid chain properties in addition to the blockage of H-bonding could be possible explanations for the observed perturbation of the Lo domain boundaries and reduction of domain height by THP-protected azo-sphingolipids in the trans-isoform. It is plausible that the blocked photolipids in the trans-configuration are not exclusively localized in the Lo phase but rather behave as a hybrid lipid able to interact with both the Ld and Lo phases.

Here, the blocked trans-photolipids partitioned inside the Lo phase could loosen the chain packing of the Lo domains, reduce line tension, and be responsible for the formation of Ld lakes within the Lo phase when converted into cis. Moreover, since the nominal height mismatch (Fig. S11 B) and total area (Fig. S9 B) of the Lo phase are significantly reduced (p < 0.001) on membranes with hydroxyl-blocked photolipids when compared with membranes with nonblocked photolipid equivalents (i.e., trans-Azo-SM and trans-Azo-Cer), we can also speculate that a small fraction of the destabilized “rigid” colipids (i.e., C18-SM and Chol) might be localized in the Ld phase as well. This would further substantiate the mechanism of Lo island formation after UV irradiation, as such a pool of rigid colipids in the Ld phase could serve as nuclei for the formation of Lo islands once the fraction of Ld-localizing THP photolipids is isomerized into cis and no longer destabilizes this pool of rigid colipids.

Changes in the mechanics of homogeneous membranes promoted by the photoisomerization of azo-spingolipids

Despite the differences in membrane domain remodeling by THP-protected versus nonprotected azo-sphingolipids, we also observed the generation of occasional membrane holes when isomerizing 3-OH-blocked photolipids from the bent cis-isoform to the straight trans-isoform, as depicted in Fig. S13 for phase-separated membranes with Azo-THP-SM. This hole formation clearly indicates that SLBs containing THP-protected azo-sphingolipids, similarly to membranes with nonblocked counterparts (Fig. S7 A), globally expand after UV-A illumination and subsequently compress upon illumination with blue light due to the bending and unbending on the N-acyl chains, respectively. Hence, photoswitching of azo-sphingolipids not only influences lipid phase separation (as discussed so far) but irrefutably affects basic mechanical properties of the membrane, such as packing and stiffness/fluidity.

To evaluate whether photoswitchable sphingolipids indeed interfere with global packing of membranes, irrespective of phase separation, we sought to perform additional analyses on a nonphase-separated system. In this context, we explored the possibility of using ternary compositions that form only a single Lo phase. It has been reported in the literature that certain sphingolipid-containing ternary mixtures such as DOPC:GalCer:Chol (37.5:37.5:25 mol %) can exhibit a single Lo phase in the presence of significant amounts of Chol (76), whereas other mixtures with the same ratio, e.g., DOPC:SM:Chol (37.5:37.5:25 mol %), can exhibit Ld-Lo phase separation (77). Some information is already available on ternary mixtures containing photolipids from previous work with colleagues, notably for the phosphatidylcholine Azo-PC. Specifically, for equimolar DPhPC:Azo-PC membrane mixtures, Urban et al. reported Ld-Lo phase separation in the presence of 10–35 mol % Chol and a single Lo phase with Chol above 35% (45). In addition, the authors also reported a single phase on giant vesicles for DOPC:Azo-PC with 20 mol % Chol (78).

With this in mind, we examined bilayers containing either Azo-Cer (as nonblocked azo-sphingolipid) or Azo-THP-SM (as 3-OH-blocked azo-sphingolipids) in a DOPC:Chol:photolipid composition with 10:6.7:10 mol ratio. As shown in Fig. S14 (using fluorescence confocal microscopy) and Fig. S15 (using AFM), these membrane compositions are indeed homogenous and do not exhibit domains either before or after irradiation with UV-A/blue light.

Next, we performed additional AFM-based force spectroscopy measurements, in particular nanoindentation experiments (54,55,79,80,81,82,83,84), on these ternary mixed homogenous SLBs having Azo-Cer (Fig. S16 A) or Azo-THP-SM (Fig. S16 D). In short, when indenting such membranes with an AFM tip, a typical jump (or discontinuity) corresponding to the force required to pierce (or break through) the SLB can be easily identified within the collected force-displacement curves (as seen in Fig. S16, B and E). The extent of such breakthrough forces is then directly linked to the mechanical properties of the membrane: lower forces are expected when the membranes are more fluid (or less compact) and higher forces when these are stiffer (or more compact). Thus, upon recording a set of force curves prior and after illumination with UV-A (λ = 365 nm) and blue (λ = 470 nm) lights, we evaluated the breakthrough events and displayed the recovered forces needed to pierce the membranes (Fig. S16, C and F) as histograms normalized by the average breakthrough force obtained for the dark-adapted state. Nonnormalized values are depicted in Fig. S17.

For homogenous DOPC:Chol:Azo-Cer SLBs, an average breakthrough force of 2.8 ± 0.3 nN (n = 900 curves) was recorded in the dark-adapted state (Fig. S17 A). After illumination with UV light, and consequent conversion of Azo-Cer to its bent cis-isoform, the force required for piercing the membrane reduced by ∼30% (Fig. S16 C) to 1.9 ± 0.2 nN (Fig. S17 B). Irradiation with blue light, on the contrary, promoted an increase of the breakthrough force back to its original average value (2.8 ± 0.3 nN; Fig. S17 C), as Azo-Cer would back isomerize to its trans-isoform. Thus, for nonblocked azo-sphingolipids, we confirmed that the cis-isoform expands/fluidifies the membrane, while the trans-isoform compacts/stiffens it. In this context, our force data clearly back up a previous study (44) based on fluorescence recovery after photobleaching, which showed that lateral lipid diffusion on a membrane made of Azo-PC (phosphatidylcholine analog with a FAAzo-4 acyl chain) was higher when the photolipid was in its cis-isoform and slower when in the trans-isoform.

Interestingly, the measured average breakthrough force required to pierce a bilayer with Azo-THP-SM was significantly higher than for bilayers containing Azo-Cer (Fig. S16, B and E). Although we cannot exclude a contribution of the THP moiety at the interface, the measured increase is mainly due to the larger phosphocholine headgroup of Azo-THP-SM compared with the smaller hydroxyl headgroup of Azo-Cer. Indeed, Garcia-Manyes et al. (81) had previously found a clear correlation of membrane piercing forces for lipids with the same acyl chains as a function of headgroup size. In that seminal work, the authors found that DPPA with the smallest headgroup had the lowest breakthrough force, followed by DPPE, DPPC, and DPPS.

When we instead analyze the normalized changes in breakthrough force for nonphase-separated DOPC:Chol:Azo-THP-SM bilayers as a function of photoisomeization, then similar trends as for Azo-Cer were recorded. More precisely, the piercing force needed to break through those membranes (n = 200 curves) also reduced by ∼25% (Fig. S16 F), from 5 ± 0.4 (Fig. S17 D) to 3.8 ± 0.4 nN (Fig. S17 E), upon irradiation with UV light and formation of cis-Azo-THP-SM, in agreement with a global expansion or fluidification of the membrane. Subsequently, the membrane breakthrough force also reverted back close to the original value (4.7 ± 0.6 nN; Fig. S17 F) upon illumination with blue light and formation of trans-Azo-THP-SM, in agreement with a global compaction or rigidification of those membranes.

Therefore, based on this force spectroscopy outcome for homogenous membranes, we can argue that the opposite changes in Lo area for phase-separated SLBs containing either 3-OH-blocked or nonblocked azo-sphingolipids (observed throughout the previous manuscript sections) are mainly due to different types of interactions these photolipids engage in via their sphingoid backbone with neighboring lipids within Lo domains and are not directly linked to the structural properties of the N-acyl photoswitch per se.

Comparison of the behavior of photolipids in direct relation to their natural sphingolipid counterparts

In this article, we have shown that photoswitchable sphingolipids with an azobenzene N-acyl chain are able to change the Ld-Lo ratio on phase-separated membranes and to affect packing on homogeneous membranes in a photoisomerization-dependent manner. However, a fundamental question remains as to how similar and biocompatible such photolipids are with respect to their natural counterparts.

Photolipids appear to maintain phase separation in the presence of native counterparts, as recently shown by Socrier et al. for photo-Gb3 (85) and previously by us for Azo-Cer (39). For example, in our previous work (39), we have shown that Azo-Cer not only maintains Ld-Lo phase separation but is also able to sustain a liquid-gel phase when mixed with DOPC and SM in the absence of Chol. From previous results with Azo-PC (45), it also appears that photolipids are, in principle, capable of forming phase separation themselves. However, the exact ratios required for these processes may differ from those of the native 18:0 or 16:0 counterparts and depend on the nature of the colipids used.

Concerning native sphingolipids, several studies in the literature suggest that small differences in headgroup, acyl chain, or sphingoid base are sufficient to significantly alter membrane properties and lateral organization. For example, it is well known that Cers have a strong ability to induce gel-fluid phase separation on membranes, as reported elsewhere (86,87). Particularly important is the presence of significant amounts of Chol, which is known to liquefy such rigid gel phases. As previously mentioned in changes in the mechanics of homogeneous membranes promoted by the photoisomerization of azo-spingolipids, no gel phases were found for equimolar DOPC:SM (77) or equimolar DOPC:GalCer (76) mixtures with 25 mol % Chol. For mixtures containing Cer, Castro et al. (88) also reported that increasing amounts of Chol liquefied the gel phases.

Since the presence or absence of certain phases depends then on the ratiometric combination and the nature of the spingolipids and colipids (i.e., unsaturated phospholipid and Chol), we still decided to investigate the phase-separation properties of natural C18 lipids in membranes under the same ratiometric combinations of colipids that we tested here for the photolipids. Therefore, we collected AFM and fluorescence images of quaternary DOPC:Chol:SM:C18-sphingolipid mixtures and finally compared them with those of quaternary DOPC:Chol:SM:photolipid (all bilayers with a molar ratio of 10:6.7:5:5 and 0.1 mol % Atto6550DOPE). Such a comparison will ultimately give us a clearer picture on how biocompatible our photolipids are in relation to their natural counterparts.

As summarized in Fig. S18, most membranes with photolipids ended up showing equivalent phase-behavior properties when compared with membranes having their natural sphingolipid counterparts. Indeed, DOPC:Chol:SM membranes with 18.7 mol % azo-β-GalCer and azo-PhCer exhibited similar total Lo area (in trans) as well as similar Ld-Lo height deviation as membranes with 18.7 mol % 18:0-β-GalCer and 18:0-PhCer (native counterparts). Membranes with 18.7 mol % Azo-SM showed a similar total Lo area (in trans) yet a slightly smaller (∼0.4 nm) but significant (p < 0.001) deviation in the Ld-Lo height mismatch compared with membranes with 18:0-SM.

A clearly different behavior was observed only for membranes with 18.7 mol % Azo-Cer, which did not exhibit any gel phase compared with their native 18:0-Cer counterpart. While Ld-Lo phase separation was observed for bilayers with 18:0-SM, 18:0-β-GalCer, and 18:0-PhCer, a gel phase (visible by AFM and fluorescence microscopy) was observed for membranes with 18:0-Cer instead. AFM analysis also shows that lipid bilayers with 18:0-Cer form a third Lo phase with an intermediate height (Fig. S18 B), which is consistent with previous results (10). However, apart from these differences, no significant variations can be observed when comparing the values of the recorded Ld-Lo height for both SLBs with azo-Cer or 18:0-Cer, as both membranes show a similar Ld-Lo mismatch height of 1.1 nm (Table S2).

Based on these last results, photolipids do not seem to behave dramatically differently from their native counterparts, at least in terms of their ability to maintain Ld-Lo phase separation and preserve their respective height deviation. This is very important information confirming that azobenzene-modified lipids are indeed biomimetic, or even bioequivalent, molecules and can therefore be considered a suitable option for manipulating native membrane properties.

Conclusions

In this work, we evaluated physicochemical foundations for the membrane remodeling ability by a family of photoswitchable sphingolipids, deciphering the relative contributions of the lipid headgroup and sphingoid backbone. We synthesized new types of N-acyl azobenzene sphingolipids with varying headgroup and sphingoid base functionalities. Then, we studied, with the help of atomic force and fluorescence microscopies, the propensity of these photolipids to alter membrane properties and laterally remodel Ld-Lo phase-separated supported membranes. Overall, we demonstrated that the headgroup type (simple hydroxyl versus more complex galactosyl or phosphocholine) does not interfere with the photoswitching ability of the various azo-sphingolipids within Ld-Lo lipid mixtures. Owing to the photodynamic reversibility of the azobenzene N-acyl chain, we further highlighted that trans-photolipids (i.e., dark-adapted and blue light-illuminated states) predominantly localize within preexisting Lo domains and compact membranes, while cis-photolipids (i.e., UV-A-illuminated state) preferentially locate within the more fluid Ld membrane regions and expand membranes.

Importantly, our results provide clear evidence that the nature of the sphingoid backbone, and its ability to engage stable H-bonding interactions with other colipids, plays a fundamental role in the way photoswitchable sphingolipids remodel Ld-Lo phase-separated membranes and change the amount, size, and height of Lo domains. Sphingosine- and phytospingosine-based lipids, with their free interfacial 3-OH and 4-OH hydroxyls, do not significantly alter the height of Lo domains when in the trans-isoform. In contrast, THP-protected lipids, with their interfacial 3-OH blocked, greatly interfere with the molecular packing and line tension of Lo domains, markedly reducing the overall Lo height mismatch. Whereas nonblocked azo-sphingolipids will promote a decrease of the total Lo phase area upon UV trigger, THP-protected azo-sphingolipids will increase the total Lo area, as well as induce a marked rise in Lo domain height after illumination with UV light.

Taken together, the structural diversity of the photoswitchable sphingolipids presented here, as well as an exquisite understanding of how these lipids alter important membrane properties, may offer new strategies for controlling the structure of biological lipid bilayers and the localization of membrane-interacting proteins. Thus, by further expanding the headgroup repertoire of photolipids, we may soon be in the position to target the fate of biologically relevant proteins on membranes using light as trigger. Such an endeavor would not only open up new, exciting avenues for optodynamic applications in the fields of synthetic biology, structural biology, or biophysics but would also offer novel perspectives toward the development of innovative photoresponsive drugs and pharmacological therapies.

Author contributions

H.G.F. and S.M.L. conducted the biophysical experiments and analyzed data. N.H. synthesized and purified most photolipids, in cooperation with N.W., H.T.-R., and J.A.F. P.S. and D.T. provided funding. D.T. supervised the synthesis of photolipids and H.G.F. their biophysical characterization. H.G.F., N.H., and S.M.L. prepared the first manuscript draft. All authors contributed to revision of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments