Abstract

Context:

The contemporary workplace creates a challenge toward physicians and their teams. They are forced into a situation, in which to be competitive they must have skills outside of their medical specialty, such as health management, pedagogy, and information and communication technologies.

Aim:

To analyze the level of stress and burnout among the medical employees in the hospital care.

Settings and Design:

Healthcare professionals from three private, municipal, and regional hospitals filled a questionnaire in the time period January–March 2021.

Methods and Material:

An adapted Maslach Burnout Inventory 55 question questionnaire was used and analyzed.

Statistical Analysis Used:

One-way ANOVA, correlation, and multiple regression analysis in SPSS.

Results:

We identified high levels of emotional exhaustion (>62% report high signs or above), high levels of depersonalization (>70% report signs of depersonalization), and low levels of personal accomplishment (<39% have below average sense of achievements).

Conclusions:

Despite the physicians and their teams reporting high levels of workload and stress, the satisfaction from work has not diminished and the evaluation for the quality of provided work is still high. Additional research into the topic is required with focus on comparison between hospital physicians and primary care physicians.

Keywords: Burnout, medical professionals, stress

INTRODUCTION

Contemporary medicine is characterized by intensive development in science and technologies as well as increased competition between different participants in the health service market. The elevated requirements for knowledge, skills expertise, and organizational behavior toward medical specialists lead to consistent professional stress. Noted by Gundersen, physicians have less time for patient contact and spend more time on administrative work. At the same time, competition is increased, and additional efforts are required from them to keep up with modern trends and promote and present their practice in a way that would make them the preferred choice for healthcare provision.[1]

Workplace stress has consequences on personal, interpersonal, and organizational level and requires high adaptational capacity in medical workers to overcome. The current pandemic has only increased the strain and pressure on the healthcare work force, and burnout had become a common problem that must be addressed.

Even without the pandemic, the medical profession is stressful. The long hours, night shifts, constant need to update your knowledge, uncertainties during procedures, and medical errors build up. This pressure is initially “invisible,” but if measures are not taken could lead to severe symptoms and even diseases.[2] Burnout is defined as a psychological syndrome that may emerge when employees are exposed to a stressful working environment with high job demands and low resources.[3] Occupational burnout from unresolvable, long-standing job stress was first described in 1974 by Freudenberger.[4] He further expands burnout syndrome in three major dimensions—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and cynicism, and decreased sense of personal accomplishment (inefficacy). These three domains exist on a continuum, beginning with emotional exhaustion. As it becomes more severe, depersonalization and cynicism occur. Finally, practitioners feel that no matter what they do, it is not enough and that there is always more work to be done and they may begin to loathe a job they once loved.[5]

In the medical field, burnout is even more problematic, as it endangers both the health and well-being of the healthcare worker and the patients, due to decrease in quality of care and higher chance of medical error.[6] The existing literature on the subject lists death and suffering of patients, insufficient training, conflict with colleagues, lack of social support, excessive workload, and uncertainty about a treatment given as the major stress factors for nurses.[7] The major stress factors for physicians are time pressure, conflict between career and family, delayed gratification, loss of autonomy, and in some cases research and teaching activities.[8] Physician assistants, medical technicians, and administrative staff demonstrate highest association with stress the following factors—job strain, overcommitment, and social support.[9]

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Healthcare professionals from three hospitals in Bulgaria participated (two public vs. one private, two urban vs. one rural). The sampling was taken from hospital in the Stara Zagora region randomly. Aproval from the ethics committee was obtained November 2020.

All questionnaires were filled after informed consent, during the time period January–March 2021. Out of the 803 returned, 762 were finished correctly and usable, with a return rate of 94%.

We used an adapted Maslach Burnout Inventory questionnaire. It included 64 questions including gender, age, work experience, marital status, current position, working hours, night shifts work, and several perceived scales on how work has affected them. Each item was graded on a 5-point scale (1-strongly disagree, 2-disagree, 3-uncertain, 4-agree, and 5-strongly agree).

One-way analysis of variance was used for the analysis of burnout according to the sociodemographic information, profession, work conditions, and level of job strain. Correlation analysis was performed to analyze the relationships among independent variables influencing burnout. Multiple regression analysis for different models was performed to identify the factors influencing work-related burnout. All calculations were performed using software SPSS V.16, with the level of significance set at P < 0.05.

Standardized (z) values were used to calculate individual profiles. People with high value of at least two parameters are correlated with high scores on neurasthenia.

High Exhaustion (Emotional Exhaustion) at z = Mean + (SD * 0.5)

High Cynicism (Depersonalization) at z = Mean + (SD * 1.25)

High Professional Efficacy (Personal Accomplishment) at z = Mean + (SD * 0.10).

RESULTS

Out of 808 hospital care physicians (HPC), 764 responded (94.55%). Two of the 764 returned could not be analyzed to improper filling out or readability.

The participants were mainly female—75.6%, with nurses slightly outnumbering physicians—51,2% for the former, to 48,8% for the latter. Mean age was 46.6 years, with mean working experience 22.5 years. More than half were married—56.1%. Participants were predominantly in surgical specialties—68.3% and working in municipal hospitals—73.2% [Table 1].

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Factor | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 214 | 28,1 |

| Female | 548 | 71,9 |

| Age | ||

| <30 | 120 | 15,7 |

| 30-40 | 156 | 20,5 |

| 40-50 | 194 | 25,5 |

| 50-60 | 224 | 29,4 |

| >60 | 68 | 8,9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 468 | 61,4 |

| Single | 286 | 38,6 |

| Profession | ||

| Physician | 322 | 42,3 |

| Nurse | 440 | 57,7 |

| Work experience | ||

| <5 | 132 | 17,3 |

| 5-10 | 94 | 12,3 |

| 10-15 | 82 | 10,8 |

| 15-20 | 70 | 9,2 |

| 20-25 | 76 | 10 |

| 25-30 | 102 | 13,4 |

| >35 | 206 | 27 |

| Specialty type/department | ||

| Surgical | 438 | 57,5 |

| Internal | 324 | 42,5 |

| Workplace | ||

| Regional hospital | 260 | 34,1 |

| Municipal hospital | 124 | 16,3 |

| Private hospital | 378 | 49,6 |

| Day/Night shifts | ||

| Yes | 594 | 78 |

| No | 168 | 22 |

| Weekend duty | ||

| Yes | 636 | 83,5 |

| No | 126 | 16,5 |

| 24 h on call | ||

| Yes | 314 | 41,2 |

| No | 448 | 58,8 |

During the one-way ANOVA and correlation analysis, the following factors showed statistically significant influence on stress and burnout:

Gender

The female gender was associated with increased stress from working with people (p = 0,014, Pearson Correlation = 0,089) [Graph 1] and feelings of tiredness when arriving at work (p = 0,024, Pearson Correlation = 0,082). Women also significantly more felt they have reached the end of their power (p = 0,014, Pearson Correlation = 0,089), despite that are not as rude in their communication with patients as men (p = 0,018, Pearson Correlation = -0,086) and understand their patients with ease (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,151) [Graph 2]. Compared to them, male participants report a statistically significant positive influence on themselves (p = 0,031, Pearson Correlation = -0,078) and their work (p = 0,008, Pearson Correlation = -0,096), emotional balance (p = 0,003, Pearson Correlation = -0,106), a surplus of energy (p = 0,013, Pearson Correlation = -0,090), and feeling refreshed after working with patients (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,153). Women also report feeling more stress in their workplace (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = 0,112), with major factors being supervision pressure (p = 0,021, Pearson Correlation = 0,084) and insufficient payment (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,175). Men have less problems with scientific work* (p = 0,019, Pearson Correlation = -0,085). Women report reduced working speed (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,131) and lacking feelings of achievement (p = 0,007, Pearson Correlation = 0,098). When comparing symptom, females have significantly more headaches (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,158), stomach pain (p = 0,025, Pearson Correlation = 0,081), problems in breathing (p = 0,008, Pearson Correlation = 0,096) and sleeping (p = 0,012, Pearson Correlation = 0,091).

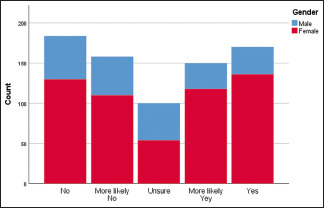

Graph 1.

Association between gender and stress from working with people

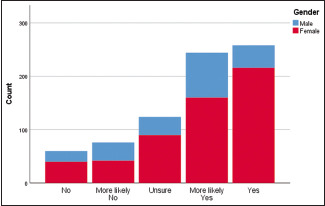

Graph 2.

Association between gender and understanding patients’ feelings with ease

*Scientific work includes any additional work outside of the standard clinical practices—research, advisory, teaching, and work with literature, scientific theories, and methods as well as data analysis.

Age

Older participants were less likely to be emotionally drained (p = 0,026, Pearson Correlation = 0,080) and felt less stress from working with people (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,138). At the same time, they complained that they are at the end of their power (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,185), and their work is destroying them (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,141). Older health professionals felt more disappointment (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,124) and displeasure (p = 0,018, Pearson Correlation = 0,086) in their work. With the increase in age, participants also felt their understanding of patients (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,152) and their problem-solving skills (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,128) are improved, but the feeling that patients blame them for their problems increases (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,224). Older respondents also feel more positive about their work (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,137). The most stressful factor for the older participants is patient pressure (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = 0,115), while for the younger generation it is scientific work (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,133) and lack of perspective (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,122). Arterial hypertension is more common in younger healthcare providers (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,384). Older respondents complain from reduced effectiveness (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,124), lack of interest (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,141), and reduced working speed (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,125). Younger age is associated with increased frequency of headaches (p = 0,006, Pearson Correlation = -0,099) and weight loss (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,121), while older age with feeling of helplessness (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,128) and loss of humor (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,136).

Marital status

Single/Divorced/Widowed partitioners have an easier time dealing with patients’ problems (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,126) [Graph 3] and their own emotions (p = 0,017, Pearson Correlation = -0,087). They also feel they have achieved positive results in their work (p = 0,026, Pearson Correlation = -0,081) and its influence on them (p = 0,007, Pearson Correlation = -0,098) and feel refreshed after working with a patient (p = 0,045, Pearson Correlation = -0,073). Married health professionals complain more from supervision stress (p = 0,026, Pearson Correlation = 0,081), negative influence of work on their family life (p = 0,037, Pearson Correlation = 0,076), headaches (p = 0,046, Pearson Correlation = 0,073), becoming vulnerable (p = 0,031, Pearson Correlation = 0,079), and gradual changes in their behavior (p = 0,011, Pearson Correlation = 0,093).

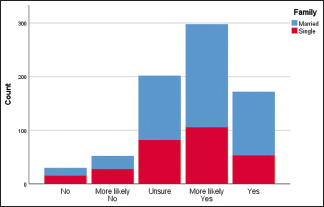

Graph 3.

Association between marital status and ease of dealing with patients’ problems

Profession

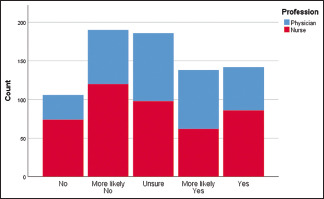

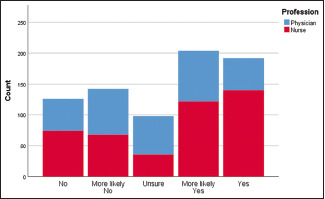

Nurses report higher levels of fatigue when coming (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = 0,111) [Graph 4], during (p = 0,028, Pearson Correlation = 0,080) [Graph 5], and after work (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,137) [Graph 6]. Compared to physicians, their stress from working with patients is higher (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = 0,114), and they are under the impression patients blame them for their problems (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,123), although they understand their emotions better (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,138). They feel at the end of their power (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,140), disappointed in their work (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,176), and that it is destroying them (p = 0,012, Pearson Correlation = 0,091). Physicians have become ruder (p = 0,025, Pearson Correlation = -0,081), but report easier time overcoming communication barrier with patients (p = 0,006, Pearson Correlation = -0,099), positive influence from their work (p = 0,024, Pearson Correlation = -0,081), feelings of achievement (p = 0,011, Pearson Correlation = -0,092), higher energy levels (p = 0,011, Pearson Correlation = -0,092), emotional stability (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,173), and feeling refreshed after working with a patient (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,172). Nurses feel more stress from patient pressure (p = 0,017, Pearson Correlation = 0,086), unethical behavior (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = 0,113), insufficient time (p = 0,022, Pearson Correlation = 0,083), and payment (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,201), while physicians from scientific work (p = 0,006, Pearson Correlation = -0,100). Nurses also suffer from lack of interest (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = 0,113), increased stress in the workplace (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,119), reduced working speed (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,149), headache (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = 0,112), breathing problems (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,155), feeling of helplessness (p = 0,039, Pearson Correlation = 0,075), and lack of achievements (p = 0,013, Pearson Correlation = 0,090).

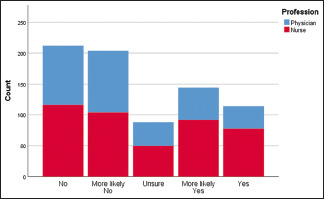

Graph 4.

Association between profession and energy coming to work

Graph 5.

Association between profession and energy during work

Graph 6.

Association between profession and energy at the end of work

Work experience

Personnel experience correlates with feeling of emotional exhaustion (p = 0,015, Pearson Correlation = 0,088), increased stress from working with people (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = 0,114), and a sense of work destroying them (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,124). Medical workers with more experience feel at the end of their power (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,167) and disappointment in their work (p = 0,011, Pearson Correlation = 0,092). They are also more sensitive about patient blaming them for their problems (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,185) and patient pressure (p = 0,025, Pearson Correlation = 0,081). At the same time, they express increased understanding of their patients (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,154), their problem-solving skills (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,144), and feel that their work can positively influence those around them (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,124). Lack of work experience on the other hand correlates with difficulties with scientific work (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,136) and loss of perspective (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,151). With more experience, healthcare professionals suffer from reduced interest in their work (p = 0,004, Pearson Correlation = 0,105), reduced speed (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = 0,113), and effectiveness (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,121). Interestingly, healthcare workers with less experience complain more from headaches (p = 0,003, Pearson Correlation = -0,106) and arterial hypertension (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,326). Their more experienced colleagues feel more irritable (p = 0,017, Pearson Correlation = 0,087) and helpless (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,136).

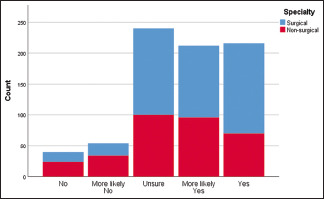

Specialty

Internal specialists are more inclined to feel tired working with people (p = 0,009, Pearson Correlation = 0,094), come to work feeling tired (p = 0,004, Pearson Correlation = 0,105), and feel exhausted at the end of the work shift (p = 0,011, Pearson Correlation = 0,092). They also feel under more stress due to patient communication (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,121), but are less concerned with becoming detached (p = 0,009, Pearson Correlation = -0,094) and ruder (p = 0,004, Pearson Correlation = -0,103) than surgical specialists. The latter feel more positively influenced by their work (p = 0,025, Pearson Correlation = -0,081), higher sense of achievement (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,150) [Graph 7], and feel more at ease solving patients’ problems (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,175) [Graph 8]. They also feel refreshed after work (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = -0,115) and less negative influence on their family life (p = 0,008, Pearson Correlation = -0,097). Healthcare professionals with surgical profiles suffer less from scientific work (p = 0,004, Pearson Correlation = -0,104) and lack of perspective (p = 0,012, Pearson Correlation = -0,090).

Graph 7.

Association between specialty and sense of achievement

Graph 8.

Association between specialty and ease of dealing with patients’ problems

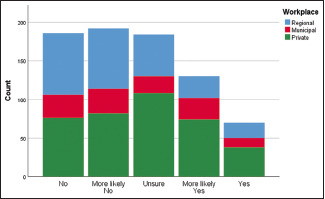

Workplace

Personnel working in smaller hospitals feel less satisfied in their work (p = 0,020, Pearson Correlation = -0,084) and blamed for patients’ problems (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = -0,165), while those working in private ones are feeling more detached (p = 0,021, Pearson Correlation = 0,083). The latter ones are also feeling more refreshed after working with patients (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,150) [Graph 9], but are stressed due to insufficient time with them (p = 0,004, Pearson Correlation = 0,105) and penalty fees (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,127). The smaller the hospital a healthcare worker is in the higher the stress from insufficient payment (p = 0,022, Pearson Correlation = -0,083) and scientific work (p = 0,013, Pearson Correlation = -0,090).

Graph 9.

Association between workplace and feelings of refreshment after working with patients

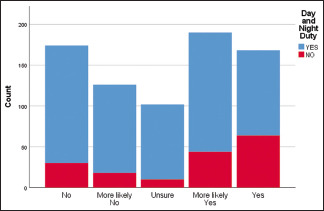

Day/Night shifts

Personnel giving 12-hour shifts are feeling tired coming to work (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = 0,111), stressed from working with people (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,139), and blamed for patients’ problems (p = 0,005, Pearson Correlation = 0,101). Those who do not give such shift feel higher levels of energy (p = 0,007, Pearson Correlation = -0,097), but are more stressed from administrative work (p = 0,006, Pearson Correlation = -0,099). The former feel under more pressure from their superiors (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,177) [Graph 10] and feel a negative influence on their family life (p = 0,012, Pearson Correlation = 0,092). They also felt they have insufficient time for rest (p = 0,010, Pearson Correlation = 0,093) and payment (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,172).

Graph 10.

Association between giving day/night shifts and feelings of pressure from superiors

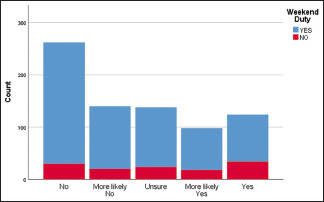

Weekend duty

Healthcare worker working on weekend feel that they have become more detached (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,125) and are more stressed from frequent changes in schedules (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,117). Weekend duty also makes them feel like there is not enough time for rest (p = 0,012, Pearson Correlation = 0,091) and has negatively influenced their family life (p = 0,006, Pearson Correlation = 0,100). It has also changed their behavior (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,141) [Graph 11] and made them more irritable (p = 0,002, Pearson Correlation = 0,112). Their sense of humor has disappeared (p = 0,003, Pearson Correlation = 0,107), they feel meeker (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,117), helpless (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,137), and are more prone to use alcohol (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,212).

Graph 11.

Association between giving weekend duty and changes in behavior

24-hour availability

Personnel giving 24-hour availability report higher levels of exhaustion at the end of the day (p = 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,115), feel that they work too much (p = 0,030, Pearson Correlation = 0,079), and come weary to work (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,157). Reasonably, people without such shift report higher level of energy (p = 0,019, Pearson Correlation = -0,085) and have less problems with scientific work (p = 0,004, Pearson Correlation = -0,105). A 24-hour availability is also connected to increased stress in the workplace (p < 0,001, Pearson Correlation = 0,144), reduced working speed (p = 0,010, Pearson Correlation = 0,094), and stomach pain (p = 0,004, Pearson Correlation = -0,105).

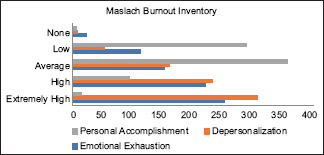

In the interview healthcare professionals, we identify high levels of emotional exhaustion (>62% report high signs or above), high levels of depersonalization (>70% report signs of depersonalization), and low levels of personal accomplishment (<39% have below average sense of achievements).

DISCUSSION

Burnout syndrome severity has been measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the gold standard for evaluating burnout in research originally developed in the 1980s.[10]

According to the American Psychological Association, there are four stages in the development of burnout syndrome[11]:

Stage I: the “honeymoon”—there is job satisfaction, hope for growth and creativity freedom;

Stage II: the “awakening”—awareness, sobriety, and false hopes;

Stage III: the “loss of tone in the work process”—characterized by constant insurmountable fatigue, loss interest in the profession, irritation; cynicism and outright criticism of the employer are increasingly being demonstrated more often;

Stage IV: “complete burn”—several months up to several years. The consequences are severe psychosomatic diseases such as diabetes, stroke, heart attack, and severe forms of depression.

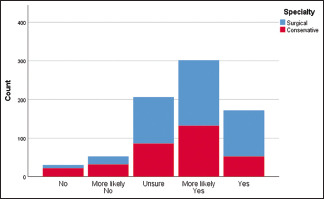

All the examined factors—age, gender, marital status, profession, specialty, work experience, giving day/night and weekend shifts as well as 24-hour availability—were found to be statistically significant influencers of Maslach Inventory categories. Despite this profession (47,27%), specialty (34,54%) and work experience (27,27%) were comparatively more influential than marital status (16,36%) and workplace (14,54%) [Graph 12 and Table 2].

Graph 12.

Correlation between independent variables and burnout syndrome in its subcategories

Table 2.

Maslach burnout inventory results

| Subcategories of MBI | None | Low | Average | High | Extremely High | Total | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Exhaustion | 23 (3,01%) | 114 (14,96%) | 152 (19,94%) | 221 (29%) | 252 (33,07%) | 100% | 27,20 | 11,874 |

| Depersonalization | 8 (1,04%) | 53 (6,95%) | 161 (21,12%) | 233 (30,57%) | 307 (40,28%) | 100% | 14,10 | 6,217 |

| Personal Accomplishment | 7 (0,91%) | 288 (37,79%) | 357 (46,85%) | 95 (12,46%) | 15 (1,96%) | 100% | 33,37 | 6,225 |

An empirical study of the burnout syndrome among medical students from 2014 found low-to-medium values on all scales, placing participants below the burnout threshold. The large discrepancy between the studies can reasonably be explained by the early stages of their career (Stage I) compared to the significantly higher level of work experience in our own and the lower prepandemic level of stress in the medical field.[12]

Yankova in study from 2013 analogous to our own reports high levels of burnout in more than 30% from the respondents. The research found a connection between the age, work experience, educational qualifications, family status, and the distribution and burden of burnout syndrome in nurses. The findings are similar to our own on the significant risk factors, but report slightly lower percentage of burnout, likely due to the absence of the Covid pandemic during that period.[10]

Shanafelt et al.[13] concluded that burnout is more likely to occur within surgeon specialties like trauma surgeons, urologists, otolaryngologists, and vascular and general surgeons. The team reported over 40% of respondents with burnout syndrome and additional associated factor with its higher prevalence—younger age, having children, area of specialization, number of nights on call per week, hours worked per week, and having compensation determined entirely based on billing. All of their findings are confirmed by our study.

The situation is similar in the primary care setting. A 2008 EGPRN study by Soler et al.[14] found 43% of respondents scored high for emotional exhaustion, 35% for depersonalization, and 32% for low personal accomplishments, with 12% scoring high burnout in all three dimensions. High burnout was found to be strongly associated with the respondents’ country of residence and European region, job satisfaction, intention to change job, sick leave utilization, the (ab)use of alcohol, tobacco, and psychotropic medication, younger age, and male sex.

See et al.[15] reported high levels of burnout among both physicians and nurses (50.3% versus 52.0%, P = 0.362). Their study notes varying burnout rates depending on the country or region, ranging from 34.6 to 61.5%. Major protective factors for physicians in their research were religiosity, experience, shift work, and number of stay-home night calls, while work days per month had a harmful effect. Among nurses, religiosity and better work–life balance were reported as having protective effect against burnout, while having a bachelor's degree as having a harmful effect.

A 2016 study by Abdo et al.[16] presents similar to our results in Egypt, with about one-quarter of questioned nurses and physicians (26,8% and 22,6%) suffering from high levels of burnout syndrome. Age, frequency of exposure to violence at work, years of experience, work burden, supervision, and work activities were found to be significant predictors of burnout syndrome.

Interestingly, Dinibutun reported lower levels of burnout among physicians who actively fought the Covid virus during the pandemic. The author attributes this to higher sense of meaningfulness of work, resulting in higher satisfaction with the work itself and, thus, creating less burnout.[17]

Limitations

The questionnaires were distributed among HCP in different types of hospital in one region. The random selection and of representations of all types of hospitals, large number of participants, and high return rate reduce possible selection and non-response bias. Despite that, additional studies covering hospitals from all regions of the country will be beneficial.

The study's focus was individual factors of the physicians contributing to increased burnout. As such, there were no questions included in the survey about external factors, like the patient's family, physicians as aggravators, etc.

CONCLUSION

The medical field is especially liable to burnout. Healthcare professionals must be regularly screened for early indicators and risk factors for burnout syndrome. Addressing these issues at the earliest possible moment will mitigate further complications and improve overall health of both professionals and patients. At the same time, the existence of such issues on system-wide and profession-wide levels must also be addressed, to reduce professional pressures and improve healthcare provider satisfaction and fulfillment. Physicians could gain important benefits from interventions to reduce burnout, especially from organization-directed interventions.[18]

Creating adequate mechanisms for coping with professional stress and pressure are of utmost importance. They must be taught during the standard medical training as a preventive measure and used as early as Stage II. The Covid pandemic gave us an excellent example how putting additional pressure on the already strained healthcare system pushed the vast majority of healthcare professionals over the burnout threshold. It is in situations like this that people must recognize their limits and take measures before severe negative effect is reached for physicians, hospitals, patients, and the healthcare system.

Multidisciplinary actions include changes in the work environmental factors along with stress management programs that teach people how to cope better with stressful events showed promising solutions to manage burnout.[19]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gundersen L. Physician burnout. 2001:145–148. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB. Historical and conceptual development of burnout. Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research. 2018:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freudenberger HJ. Staff burn-out. J Soc Issues. 1974;30:159–65. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridgeman PJ, Bridgeman MB, Barone J. Burnout syndrome among healthcare professionals. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:147–52. doi: 10.2146/ajhp170460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein J, Grosse Frie K, Blum K, von dem Knesebeck O. Burnout and perceived quality of care among German clinicians in surgery. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:525–30. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray-Toft P, Anderson JG. Stress among hospital nursing staff: Its causes and effects. Soc Sci Med A. 1981;15:639–47. doi: 10.1016/0271-7123(81)90087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siu C, Yuen SK, Cheung A. Burnout among public doctors in Hong Kong: Cross-sectional survey. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18:186–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou LP, Li CY, Hu SC. Job stress and burnout in hospital employees: Comparisons of different medical professions in a regional hospital in Taiwan. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004185. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Янкова Г. Burn out–синдрома в професионалната дейност на медицинските сестри. Medicine. 2014;4:226–31. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Лечева З, Георгиева Л, Стойчева M. Теоретични основи на професионалния стрес и бърнаут синдрома. Soc Med. 2017;1:33–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Димитрова С, Форева Г, Проданова М, Комсийска Д, Пеева К. Студенти‑Медици И Бърнаут Синдром‑Емпирично Изследване. Announcements of Union of Scientists - Sliven. 2014;28:47–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250:46371. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ac4dfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soler JK, Yaman H, Esteva M, Dobbs F, Asenova RS, Katic M, et al. Burnout in European family doctors: The EGPRN study. Fam Pract. 2008;25:24565. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.See KC, Zhao MY, Nakataki E, Chittawatanarat K, Fang WF, Faruq MO, et al. Professional burnout among physicians and nurses in Asian intensive care units: A multinational survey. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:2079–90. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdo SA, El-Sallamy RM, El-Sherbiny AA, Kabbash IA. Burnout among physicians and nursing staff working in the emergency hospital of Tanta University, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2016;21:906–15. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.12.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinibutun SR. Factors associated with burnout among physicians: An evaluation during a period of COVID-19 pandemic. J Healthc Leadersh. 2020;12:85. doi: 10.2147/JHL.S270440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, Lewith G, Kontopantelis E, Chew-Graham C, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:195–205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romani M, Ashkar K. Burnout among physicians. Libyan J Med. 2014;9 doi: 10.3402/ljm.v9.23556. 10.3402/ljm.v9.23556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]