Abstract

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a leading cause of respiratory failure and death in ICU patients. Experimentally, acute lung injury (ALI) resolution depends on repair of mitochondrial oxidant damage by the mitochondrial quality control (MQC) pathways, mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy, but nothing is known about this in human lung. In a case-control autopsy study, we compared lungs of subjects dying of ARDS (n=8; cases) and age/gender-matched subjects dying of non-pulmonary causes (n=7; controls). Slides were examined by light microscopy and immunofluorescence confocal microscopy, randomly probing for co-localization of citrate synthase (CS) with markers of oxidant stress, mitochondrial DNA damage, mitophagy, and mitochondrial biogenesis. ARDS lungs showed diffuse alveolar damage with edema, hyaline membranes, and neutrophils. Compared with controls, a high degree of mitochondrial oxidant damage was seen in type 2 epithelial (AT2) cells and alveolar macrophages by 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine and malondialdehyde co-staining with CS. In ARDS, anti-oxidant protein heme oxygenase-1 and DNA repair enzyme N-glycosylase/DNA lyase (Ogg1) were found in alveolar macrophages, but not AT2 cells. Moreover, MAP1 light chain-3 (LC3) and serine/threonine-protein kinase (Pink1) staining were absent in AT2 cells, suggesting mitophagy failure. Nuclear respiratory factor-1 (NRF1) staining was missing in the alveolar region, suggesting impaired mitochondrial biogenesis. Widespread hyper-proliferation of AT2 cells in ARDS could suggest defective differentiation into type 1 cells. ARDS lungs show profuse mitochondrial oxidant DNA damage, but little evidence of MQC activity in AT2 epithelium. Since these pathways are important for ALI resolution, our findings support MQC as a novel pharmacologic target for ARDS resolution.

Key words: respiratory distress syndrome, mitochondrial turnover, mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy, oxidant stress, DNA damage

INTRODUCTION

Despite decades of research and advancements in supportive care, the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) remains prevalent1 and a significant cause of death and disability among critically ill patients2. A number of lung injury patterns are reported, but the histopathologic hallmark and most lethal pattern of ARDS3 is diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), found in roughly half of cases, and characterized by alveolar hyaline membrane formation, acute inflammation, and breakdown of the alveolar-capillary barrier leading to protein-rich pulmonary edema4. A programmed alveolar resolution response is the proliferation of alveolar type 2 (AT2) cells5, the mitochondria-rich putative alveolar epithelial stem cells that may differentiate into type 1 (AT1) cells to re-epithelialize the basement membrane after injury6 , 7. Animal models of acute lung injury (ALI) have shown AT2 cell support of alveolar function depends on activation of the cellular mitochondrial quality control (MQC) programs, mitochondrial biogenesis8 , 9, the generation of healthy mitochondria, and mitophagy8 , 10, or macroautophagosomal disposal of damaged mitochondria. Activation of both programs reduces alveolar inflammation, oxidant stress, and necroptotic cell death8, 9, 10. Our understanding of the state of MQC during human illness is nascent, but improving. For instance, we have shown that activation of mitochondrial biogenesis is evident in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with sepsis and associated with more ICU-free days11. However, little is known about MQC in the alveolar region in patients with ARDS. Therefore, we performed a histopathologic case-control autopsy study of lung tissue samples collected from patients dying of either ARDS or non-pulmonary causes. We hypothesized that MQC program activation could be measured in the alveolar region and might inform potential novel therapeutic drug targets12.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject selection

Eligible subjects were 18 – 80 years old with a post-mortem diagnosis of exudative phase diffuse alveolar damage. Control subjects were matched for age (± 6 years) and biological sex, died from non-pulmonary causes, and exhibited normal lung histology. Median (interquartile range) time to autopsy was 44 (26-58) hours.

Histology and confocal microscopy

De-identified lung tissue samples collected at autopsy were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, cut into five μm sections, and mounted onto slides. Sections were deparaffinized in an ethanol series, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), dehydrated, and cover slipped. We evaluated acute lung injury using a histology scoring system. Ten random fields of H&E-stained lung selected from areas of or adjacent to acute lung injury (at a final magnification of 400x) were captured and scored by a blinded researcher. A score of 0-4 was assigned to each pathological feature: 1) neutrophils and mononuclear cells in the alveolar space; 2) inflammatory cells in the interstitial space; 3) hyaline membranes; 4) proteinaceous debris filling the airspace, and 5) alveolar septal thickening. The sum of the scores was then presented as a percentage with a final score ranging between 0 and 100. Captured images were uploaded and analyzed by NIS-Elements AR software (v5.30, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunofluorescence staining was performed using the following primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti-citrate synthase (CS) (MAB3087, Millipore, Billerica, MA); 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) (sc-66036, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX); malondialdehyde (MDA) (Ab6463, Abcam, Waltham, MA); thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF1) (ab133737, Abcam); aquaporin-5 (AQP-5) (sc-28628, Santa Cruz); dynamin-1-like protein (Drp1) (8570s, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA); heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) (ADI-SPA-896-F, Enzo, Farmingdale, NY); nuclear respiratory factor-1 (NRF1) (sc-23624, Santa Cruz); MAP1 light chain 3 (LC3) (sc-16755, Santa Cruz); serine/threonine-protein kinase (Pink1) (ab23707, Abcam); CD68 (sc-9139, Santa Cruz); alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (sc-53142, Santa Cruz); and N-glycosylase/DNA lyase (OGG1) (sc-376935, Santa Cruz). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Alexa Fluor–coupled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used at 1:400. Sections were incubated in primary antibody diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for overnight, washed twice in PBS for 10 min, incubated in secondary antibody diluted in PBS for 1 h and washed again twice for 5 min. Coverslips were mounted using anti-fade mounting media with DAPI (P36935, Invitrogen). All incubations were performed at room temperature. Five stained sections from each sample were examined on a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 710, Oberkochen, Germany) and imaged at 40-60x magnification within 72 hours of staining. Multichannel images were captured from each section. All exposures were performed using best-microscopy practices to avoid signal saturation while maximizing the optimum range of intensity values detected by the camera in control samples. Image quantification was accomplished using NIS-Elements AR software (v5.30, Nikon). The signal intensity in collected images were measured automatically, and was compared to the signal within negative controls used to determine exposure times and prevent false positives. The mean pixel intensities were averaged for each slide to generate a mean value for each sample.

TUNEL assays

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) assays were performed on thin paraffin-embedded, formalin-fixed lung sections using a commercial kit (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Negative and positive control sections were prepared with label solution only or by pre-induction of strand breakage with recombinant DNase I. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Sections from six subjects in each group were used in the staining, and at least 5 unique fields/section were quantified in each experiment by a blinded observer using Nikon image software (NIS-Elements BR 3.2).

Statistical analysis

We calculated that n=6 subjects per group would provide 80% power to detect significant differences for α=0.05. Comparisons between groups were made using Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

The study enrolled fifteen subjects total: n=8 DAD cases and n=7 controls. Six subjects from each group were chosen at random for any given analysis. Demographics, cause of death, smoking history, and lung disease history are shown in the Table. Age and sex distributions were equitable between the groups. In contrast to the control subjects, which displayed normal lung histology, DAD lung samples showed interstitial edema, inflammation, and hyperemia, and alveolar-capillary damage evidenced by the presence of intra-alveolar acute inflammation, erythrocytes, and fibrin (Supplemental Fig. 1A). As expected, DAD scores were calculated and significantly higher in the DAD cases compared with controls (Supplemental Fig. 1B). DAD lung sections also had significantly increased expression of α-SMA, a marker of myofibroblast differentiation, characteristic of the fibroproliferative phase of ARDS (Supplemental Fig. 2)13,14.

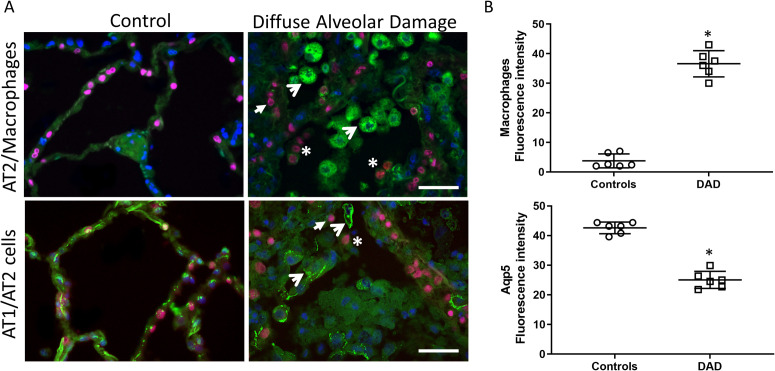

We next sought to identify major cell types present in the alveolar region by labeling the AT1 cells, AT2 cells, and macrophages (Figure 1 , Supplemental Fig. 3-4). Intra-alveolar macrophages (identified by CD68 staining) were found in significant numbers in DAD lung (Figure 1A), which was confirmed by quantification (Figure 1B). Whereas AT1 cells (identified by Aqp5 staining) lined the alveolar walls in control lung, in DAD lung, the AT1 cell marker Aqp5 was reduced and (when present) commonly observed in the alveolar space and inside alveolar macrophages, indicative of macrophage phagocytosis of dead or dying AT1 cells. Similarly, AT2 cells (identified by TTF1 staining) from DAD lung were also observed in the alveolar space and occasionally inside alveolar macrophages, indicative of cell death and detachment from the alveolar basement membrane (Figure 1A). TUNEL staining confirmed significant increases in cell death in the alveolar region including (but not limited to) AT2 cells (Supplemental Fig. 5). These data together support significant alveolar epithelial cell death in DAD and a robust alveolar macrophage response, which includes phagocytosis of host cellular debris.

Figure 1.

Alveolar epithelial damage and inflammation. A) Top row: Alveolar region of human lung stained for CD68 (macrophage marker, green), TTF1 (AT2 cell marker, red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Open arrows denote macrophages and closed arrows denote AT2 cells. Asterisks denote intra-alveolar AT2 cells. Bottom row: Alveolar region of human lung stained for epithelial markers Aqp5 (AT1 cell marker, green), TTF1 (red), and nuclei (DAPI blue). Aqp5 staining is evident in AT1 cells and a few macrophages (open arrows). Closed arrows denote AT2 cells. Asterisk denotes intra-alveolar AT2 cells. Original magnification, ×600. Bars = 20 μm. B) Scatter plots show the quantification of macrophage fluorescence density (upper panel) and Aqp5 fluorescence density (lower panel). Bars are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 by Student’s t-test.

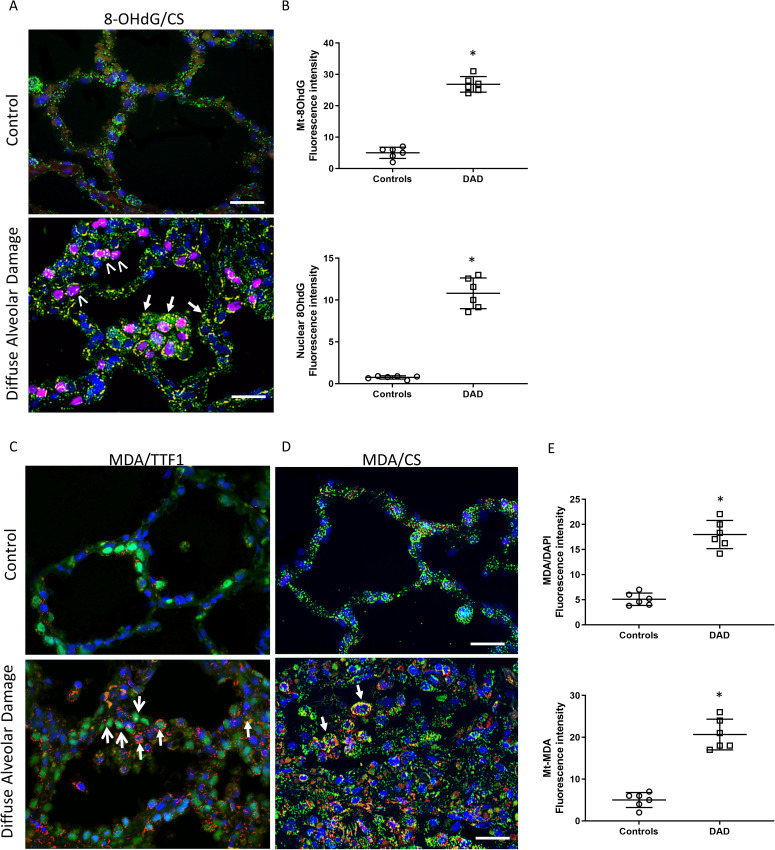

To investigate a potential mechanism for the observed epithelial cell death, we next analyzed the lung samples for evidence of oxidant damage (Figure 2 , Supplemental Fig. 6-8). First, the alveolar region was stained for 8-OHdG, a marker of nucleic acid oxidation, and co-localized with citrate synthase (CS), a mitochondrial matrix protein, and cell nuclei (DAPI). In contrast to the control lung, the DAD lung displayed increased and widespread 8-OHdG staining, indicative of oxidant damage in the alveolar epithelium and macrophages (Figure 2A). This co-localized with both nuclei (magenta) and mitochondria (yellow) indicating bi-genomic oxidant DNA damage. These relationships were quantified using fluorescence density and were statistically significant (p<0.05) (Figure 2B). We next analyzed the alveolar region for evidence of lipid oxidation by staining for malondialdehyde (MDA), and co-localized separately to AT2 cells (by TTF1 staining) or mitochondria (by CS staining) (Figure 2C-D). In comparison to control lung, there was hyperplasia of AT2 cells along the alveolar basement membrane. Furthermore, MDA staining in AT2 cells displayed a punctate and cytoplasmic distribution suggestive of mitochondrial co-localization (Figure 2C). This was demonstrated by co-localization staining of MDA with the mitochondrial protein CS (yellow), which confirmed lipid oxidation of mitochondria (Figure 2D). Quantification of fluorescence indicated higher total and mitochondrial MDA staining (Figure 2E). Taken together, we found abundant mitochondrial DNA and lipid oxidant damage in the alveolar region, including in AT2 cells, in subjects dying of DAD.

Figure 2.

Alveolar epithelial oxidant damage. A) View of the alveolar region of human lung tissue stained for nucleic acid oxidation by 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG, red), citrate synthase (CS, green), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Note, the nuclear co-localization (purple nuclei) demonstrating increased nuclear DNA oxidation (marked with white arrowheads) and mitochondrial co-localization (yellow dots) demonstrating mitochondrial DNA oxidation (marked with short arrows) in DAD compared with control lung. Magnification is ×600. Bars are 20 μm. B) Scatter plots show the quantification of 8-OHdG fluorescence intensity for mitochondrial (yellow/orange fluorescence, top panel) and nuclear (magenta fluorescence, bottom panel) oxidant damage. C) Alveolar region stained for lipid oxidation by malondialdehyde (MDA, red), TTF1 (AT2 cell marker, green nuclei) and other nuclei (DAPI, blue). Closed arrows show the punctate and cytoplasmic distribution of MDA staining in AT2 cells. Open arrows show prominent AT2 cell hyperplasia. D) Alveolar region stained for lipid oxidation by MDA (red), citrate synthase (CS, green) and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Closed arrows show the mitochondrial co-localization with MDA. Nuclear MDA staining was not prominent. Magnification is ×600. Bars are 20 μm. E) Scatter plots show the quantification of total MDA fluorescence intensity (top panel) and mitochondrial fluorescence intensity (yellow fluorescence, bottom panel). Bars are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 by Student’s t-test.

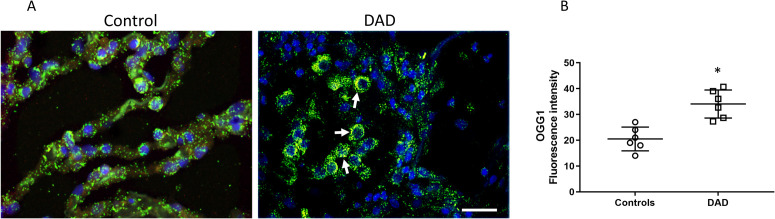

In view of this mitochondrial oxidant damage, we next analyzed the alveolar region for evidence of mitochondrial DNA repair by probing for expression and distribution of the Ogg1 DNA repair enzyme (Figure 3 , Supplemental Fig. 9). We observed Ogg1 co-localization with mitochondria, largely confined to the intra-alveolar cells (consistent with alveolar macrophages) but scant expression or co-localization in the alveolar epithelial cells (Figure 3A). Total alveolar Ogg1 co-localization with mitochondria was significantly increased as measured by quantitative fluorescence density (Figure 3B), consistent with activation of mitochondrial DNA repair mechanisms in alveolar macrophages but not alveolar epithelial cells.

Figure 3.

Alveolar mitochondrial DNA repair. A) Alveolar region of human lung stained for the DNA repair enzyme Ogg1 (red), citrate synthase (green), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Arrows denote areas of Ogg1 co-localization with mitochondria (yellow), observed especially in intra-alveolar cells. Magnification is ×400. Bars are 20 μm. B) Scatter plots show the quantification of yellow fluorescence density indicative of mitochondrial-Ogg1 co-localization. Bars are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 by Student’s t-test.

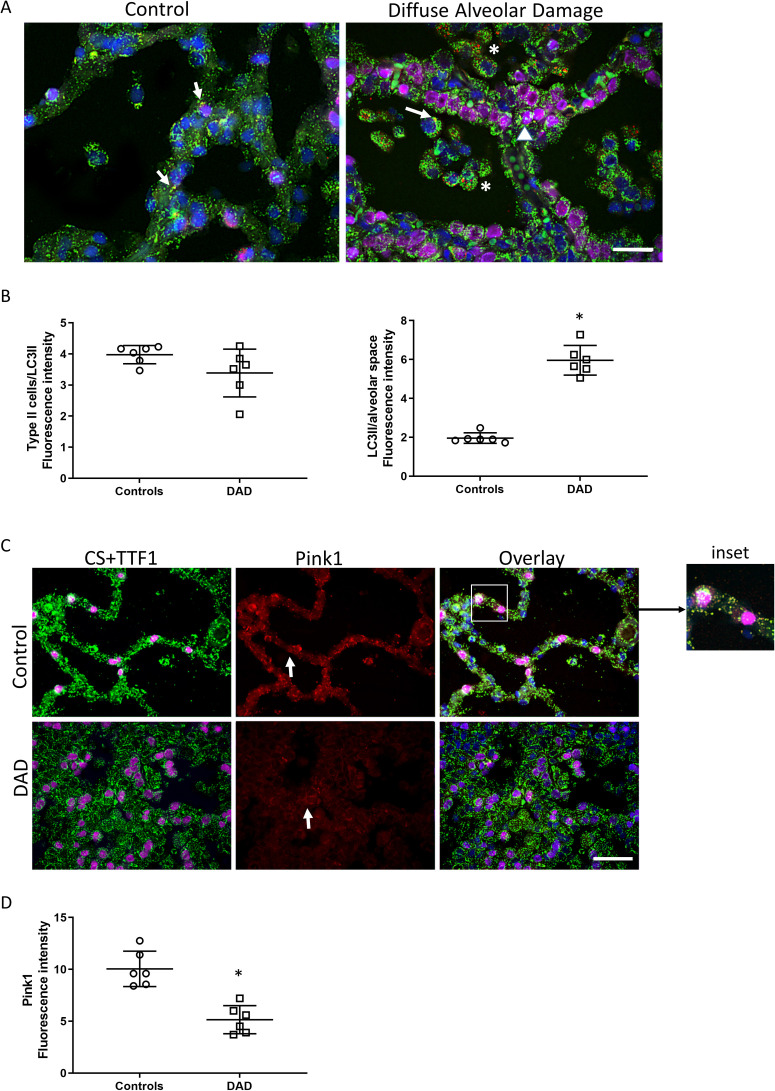

Given the degree of mitochondrial damage observed, we also investigated whether there was activation of mitophagy, the autophagosomal recycling of damaged mitochondria. We performed confocal microscopy for the mitophagy proteins LC3II and Pink1 (Figure 4 , Supplemental Fig. 10). LC3II distribution was increased in DAD lung compared with control, and localized to alveolar macrophages (Figure 4A). There was little expression evident in AT2 cells. By immunofluorescence density quantification, co-localization of alveolar LC3II and CS was increased in DAD lung compared with control lung, indicative of activation of the mitophagy program largely confined to alveolar macrophages (Figure 4B). In contrast, Pink1 distribution was significantly decreased in DAD lung compared with controls (Figure 4C-D) and there was little co-localization observed with CS, particularly in DAD lung. Taken together, of the two mitophagy pathways interrogated, only one (LC3II) was active in alveolar macrophages, but not in AT2 cells, suggesting impaired clearance of damaged mitochondria in AT2 cells in patients dying of ARDS.

Figure 4.

Alveolar mitophagy. A) Confocal immunofluorescence micrographs of the alveolar region of control and DAD lung section stained with four channel immunofluorescence staining for mitochondrial citrate synthase (CS, green), LC3II (red), TTF1 (AT2 cell marker, magenta), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). There is increased LC3II staining in alveolar macrophages in DAD (asterisks), but not in AT2 cells (arrow head). There is scarce mitochondrial/LC3 co-localization (arrows) apparent in both control and DAD lung. B) Scatter blots show the quantification of fluorescence intensity of mitochondrial LC3II staining (yellow/orange fluorescence). C) Confocal micrograph of the alveolar region of human lung stained for Pink1 (Red), citrate synthase (CS, green), TTF1 (AT2 cell marker, magenta), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). There is scarce mitochondrial/Pink1 co-localization (yellow fluorescence). The inset shows Pink1 staining in alveolar epithelium (arrow). D) Scatter plot shows the quantification of fluorescence density of mitochondrial Pink1 staining. Magnification for A) and C) is ×600 and bars are 20 μm. Bars are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 by Student’s t-test.

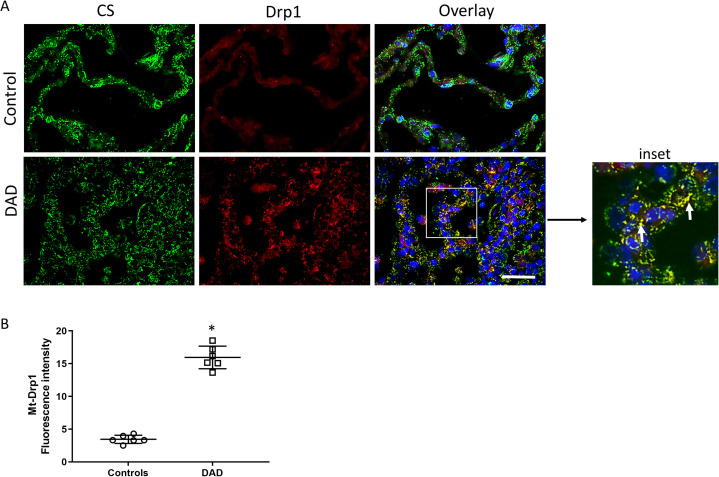

Given the evidence of impaired mitophagy in the alveolar region, we investigated whether there was increased alveolar mitochondrial fragmentation (fission), as noted in a number of other disease states12, by measuring the fission protein Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) (Figure 5 ). There was increased distribution of alveolar Drp1 in DAD compared with control lung (Figure 5A). Furthermore, there was significantly increased co-localization of Drp1 with CS, confirming increased mitochondrial fission in the alveolar region of patients dying of ARDS (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Alveolar mitochondrial fission. A) Confocal micrographs of the alveolar region of human lung stained for Drp1 (Red), citrate synthase (CS, green), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). The inset shows increased Drp1 staining in alveolar epithelium (arrows). Yellow fluorescence indicates co-localization of mitochondria (CS) and Drp1. Magnification is ×600, bars are 20 μm. B) Scatter plots show the quantification of fluorescence density of mitochondrial Drp1 staining. Bars are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 by Student’s t-test.

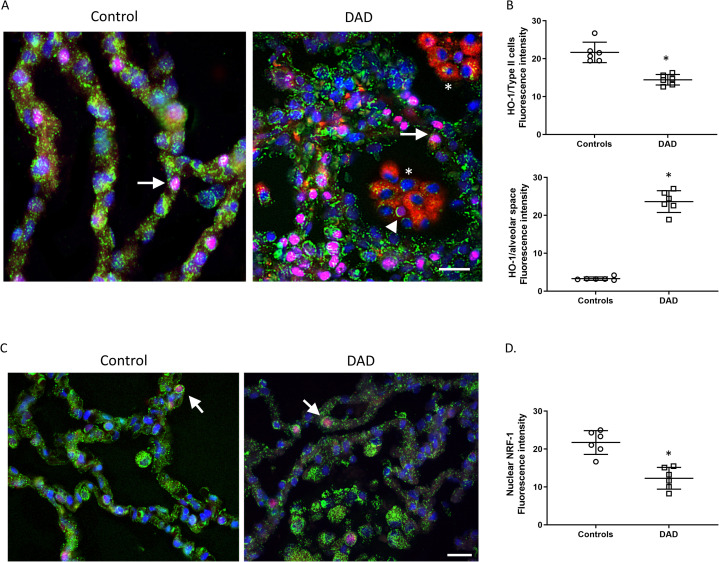

To interrogate alveolar mitochondrial biogenesis, the host program that responds to mitochondrial damage by increasing the mitochondrial mass, we checked for two critical regulators, the antioxidant protein heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)9 , 15, and nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1)16 (Figure 6 , Supplemental Fig. 11-12). HO-1 distribution was striking in intra-alveolar cells, mainly in alveolar macrophages (Figure 6A), but minimal in AT2 cells compared with control lung (Figure 6B). Nuclear accumulation of NRF1 was also minimal in both control and DAD lung (Figure 6C) but by fluorescence density measurement was significantly decreased in DAD compared with control (Figure 6D). Furthermore, CS fluorescence distribution was decreased in DAD alveolar epithelium compared with intra-alveolar cells (likely alveolar macrophages). Taken together, these data suggest an impairment in activation of mitochondrial biogenesis and reduced mitochondrial volume density in DAD alveolar epithelial cells compared with DAD alveolar macrophages and control alveoli.

Figure 6.

Alveolar mitochondrial biogenesis. A) Confocal micrograph of the alveolar region of human lung stained for HO-1 (red), citrate synthase (mitochondrial matrix protein, green), TTF1 (magenta) to stain for AT2 cells (closed arrows), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). The asterisks show clusters of intra-alveolar cells in DAD lung consistent with alveolar macrophages that display strong HO-1 expression. There appears to be an intra-alveolar AT2 cell (arrow head) suggestive of phagocytosis by macrophages. Magnification is ×600, bars are 20 μm. B) Scatter plot shows the quantification of fluorescence intensity of HO-1 staining. Upper panel in Type 2 cells. Lower panel in interalveolar spaces. C) Confocal micrograph of the alveolar region of human lung stained for NRF-1 (red), citrate synthase (green), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Nuclear NRF-1 staining (magenta nuclei) in alveolar epithelium is minimal (arrows). Magnification is ×600, bars are 20 μm. D) Scatter plots show the quantification of fluorescence density of NRF-1/DAPI staining. Bars are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 by Student’s t-test.

DISCUSSION

Significant progress in ARDS management has been made over the last twenty years related to reducing ventilator-induced lung injury17, 18, 19, 20, yet ARDS-associated mortality still remains high in part because novel therapies are lacking to improve outcomes1 , 2. One potential therapeutic target identified by preclinical studies is the alveolar MQC program which is critical for resolution of experimental pneumonia and acute lung injury5 , 8, 9, 10; however, these pathways have not been investigated in human lungs. We hypothesized that better understanding of MQC in human DAD lung might support future targeted pharmacologic interventions, and we performed a histopathologic case-control study investigating alveolar mitochondrial damage and repair in patients dying from ARDS. We found evidence of widespread mitochondrial oxidant damage and fragmentation in alveolar epithelium and alveolar macrophages. Despite this mitochondrial injury, we found little evidence of activation of the MQC programs in AT2 cells, the putative stem cells for the alveolar epithelium6 , 7. Instead, there was hyper-proliferation of AT2 cells without significant AT1 cell coverage of the alveolar basement membrane, which could suggest impaired differentiation of AT2 cells into AT1 cells.

Inflammatory and oxidant alveolar injuries are the hallmarks of acute lung injury (ALI) and ARDS and produce damage of epithelial cellular and subcellular components such as nuclear DNA and mitochondria21 , 22. Damaged and dysfunctional mitochondria in turn produce more reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to a feed forward cycle propagating further oxidant-driven injury21 , 23, 24, 25. The use of high inspired oxygen concentrations in these patients is prevalent, which exerts extra stress on the lung’s antioxidant and mitochondrial systems26. Previous ALI/ARDS studies have found signs of oxidant damage, including in serum27, exhaled breath22 , 28, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid22 , 29. Our study provides direct evidence of widespread alveolar mitochondrial oxidant injury, affecting both mitochondrial DNA and lipids, in subjects dying of ARDS. Our histologic findings advance previous preclinical8 and clinical22 , 27, 28, 29 studies and provide a plausible mechanism for AT2 cell dysfunction in ARDS.

Mitochondrial DNA damage, and specifically guanine oxidation, is a stimulus for the nuclear-encoded base excision enzyme Ogg1. Ogg1 is critical to mitochondrial DNA damage mitigation, as its inhibition triggers apoptosis in pulmonary artery endothelial cells under oxidant stress30. Its presence can attenuate mitochondrial DNA damage and ALI in rodents with Pseudomonas pneumonia31. Similar to the preclinical data, our findings in human DAD indicate significant induction of Ogg1 in alveolar macrophages in response to mitochondrial DNA oxidant damage, but not in AT2 cells, suggesting repair failure in this cell type in lethal ARDS.

Mitochondrial dysfunction, such as with excess ROS leakage, is a stimulus for activation of the two MQC programs: mitochondrial biogenesis, the renewal of healthy mitochondria; and mitophagy, the recycling of components of damaged mitochondria. Both MQC programs are anti-oxidant by nature and serve as critical alveolar host responses to ALI/ARDS8, 9, 10 : Mitochondrial biogenesis is coupled through HO-1, a cytoprotective anti-oxidant enzyme, to anti-inflammatory IL-10 and SOCS expression15 whereas mitophagy reduces oxidant production directly by disposing of ROS-producing mitochondria and depends on Nfe-2l2, a key transcription factor that binds to antioxidant response elements10. In non-lethal ALI in septic mice and non-lethal S. pneumoniae pneumonia in baboons, mitochondrial biogenesis is evident in AT2 cells several days after initiation of infection, but high inspired oxygen concentrations are absent5 , 8. Mitophagy is also evident in AT2 cells soon after inoculation in non-lethal S. aureus pneumonia/ALI mouse models8 , 10. Here, in the lungs of lethal ARDS patients, there was little evidence of activation of either program in AT2 cells. This suggests failure of the AT2 cell MQC program and provides proof-of-principal that alveolar MQC is a pharmacologic target12 , 32. Furthermore, AT2 mitochondrial dysfunction is also implicated in pathogenesis of other lung diseases, such as pulmonary fibrosis33 , 34, suggesting AT2 MQC may be broadly relevant to lung injury resolution, and not specific to DAD.

Our study is limited by several factors. First, because we used human tissues, we cannot define mechanism; however, our study is associational and advances prior mechanistic studies in rodents and nonhuman primates to the clinical arena5 , 8, 9, 10. Second, because we quantified protein immunofluorescence at the alveolar level (per field) rather than per cell type, differences in fluorescence intensity between groups could reflect variations in cell number within the field, rather than differences in protein expression per cell. Third, we could not obtain smoking history in approximately half of the subjects, and cannot exclude smoking as a confounder; however, we did document when subjects had smoking-related lung disease evident on pathologic exam. Fourth, we did not interrogate AT1 cells directly for signs of oxidative damage or damaged mitochondria clearance, and therefore cannot comment on whether AT1 MQC is functional in lethal ARDS or not. Finally, we did not observe significant autolysis in the tissue samples used for the study, and the deceased subjects were refrigerated if autopsy could not be performed the same day, but we cannot exclude it may have been present or affected our results. However, prior research has shown that mitochondrial function and mitochondrial DNA remain intact even after storage at unfavorable conditions35; these findings together suggest this did not contribute much to our results.

Whether AT2 cells are truly the stem cells for the alveolar region is controversial7. Murine lineage tracing studies have found evidence that AT2 cells do serve as a renewable source of AT1 and AT2 cells after birth, particularly after alveolar injury6 , 7 , 36. However, this process may be mischaracterized and simply represent a reaction similar to squamous metaplasia37. As such, we can only speculate on the significance of finding AT2 hyper-proliferation, and hypothesize that this might indicate defective differentiation, but acknowledge this is an active point of contention and cannot be determined from our studies.

In conclusion, we present direct evidence of widespread mitochondrial oxidant injury in AT2 cells in lethal ARDS, but few signs of activation of MQC programs to restore mitochondrial function and promote resolution of lung injury. Our findings provide a rationale for targeting AT2 cell MQC programs pharmacologically as a means to improve lung injury resolution and recovery of patients with otherwise non-resolving and lethal ARDS. Future studies should also consider the extent to which delivery of high oxygen concentrations to the lung could contribute to mitochondrial damage and failure in the alveolar epithelial region.

Table.

Subject demographics.

| Number | Age | Sex | Race | Group | Pre-mortem ARDS | Cause of death | Smoking history | Lung disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | Female | Other | DAD | Yes | DAD, influenza, sepsis | Unknown | None |

| 2 | 73 | Male | White | DAD | Yes | DAD, acute pneumonia, severe CAD, immune-mediated myocarditis | Former (20 P-Y) | None |

| 3 | 63 | Male | White | DAD | Yes | Anoxic brain injury due to DAD, HSV tracheitis, HSV pneumonia | Unknown | None |

| 4 | 68 | Male | White | DAD | Yes | DAD, severe CAD | Unknown | PAH |

| 5 | 71 | Female | White | DAD | Yes | DAD, abdominal sepsis, multiple organ failure | Unknown | None |

| 6 | 69 | Male | White | DAD | Yes | DAD, Streptococcal bronchopneumonia, PE, anoxic brain injury, severe CAD and MI | Yes | Emphysema |

| 7 | 48 | Female | Black | DAD | Yes | DAD, angioinvasive mucormycosis, gastrointestinal bleeding, cirrhosis | None | None |

| 8 | 56 | Male | Black | DAD | Yes | DAD, S. aureus bacteremia, PE | Unknown | None |

| 9 | 74 | Male | Black | Control | No | Acute MI | None | None |

| 10 | 62 | Male | Black | Control | No | Complications of cirrhosis | None | None |

| 11 | 36 | Female | Black | Control | No | Left main coronary artery dissection | Unknown | Asthma |

| 12 | 50 | Female | White | Control | No | Self-inflicted gunshot wound to chest | Former (19 P-Y) | None |

| 13 | 64 | Male | White | Control | No | Severe CAD and acute MI | None | None |

| 14 | 77 | Female | White | Control | No | Intracerebral hemorrhage due to amyloid angiopathy | Unknown | Unknown |

| 15 | 52 | Male | White | Control | No | Abdominal abscess following laparoscopic surgery | Unknown | None |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CAD, coronary artery disease; DAD, diffuse alveolar damage; HSV, herpes simplex virus; MI, myocardial infarction; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PE, pulmonary embolism; P-Y, pack-years.

Uncited reference

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Martha Salinas for her technical work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare there are no competing financial conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The study was designed by BDK, CAP, and HBS. The data was collected, analyzed, and/or interpreted by all authors. The manuscript was written by BDK and edited and approved by all authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

ETHICS APPROVAL/CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board (#Pro00033619) under a waiver of consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

FUNDING

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL130557).

Footnotes

Grant funding: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL130557)

Supplementary data

REFERENCES

- 1.Bellani G., Laffey J.G., Pham T., et al. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA. Feb 23. 2016;315(8):788–800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Heart Lung Blood Institute Petal Clinical Trials Network. Moss M., Huang D.T., et al. Early Neuromuscular Blockade in the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med. May 23 2019;380(21):1997–2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardinal-Fernandez P., Bajwa E.K., Dominguez-Calvo A., Menendez J.M., Papazian L., Thompson B.T. The Presence of Diffuse Alveolar Damage on Open Lung Biopsy Is Associated With Mortality in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest. May 2016;149(5):1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thille A.W., Esteban A., Fernandez-Segoviano P., et al. Comparison of the Berlin definition for acute respiratory distress syndrome with autopsy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Apr 1 2013;187(7):761–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201211-1981OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredenburgh L.E., Kraft B.D., Hess D.R., et al. Effects of inhaled CO administration on acute lung injury in baboons with pneumococcal pneumonia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. Oct 15 2015;309(8):L834–L846. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00240.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barkauskas C.E., Cronce M.J., Rackley C.R., et al. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J Clin Invest. Jul. 2013;123(7):3025–3036. doi: 10.1172/JCI68782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai T.J., Brownfield D.G., Krasnow M.A. Alveolar progenitor and stem cells in lung development, renewal and cancer. Nature. Mar 13. 2014;507(7491):190–194. doi: 10.1038/nature12930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suliman H.B., Kraft B., Bartz R., Chen L., Welty-Wolf K.E., Piantadosi C.A. Mitochondrial quality control in alveolar epithelial cells damaged by S. aureus pneumonia in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. Oct 1 2017;313(4):L699–L709. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00197.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Athale J., Ulrich A., MacGarvey N.C., et al. Nrf2 promotes alveolar mitochondrial biogenesis and resolution of lung injury in Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in mice. Free Radic Biol Med. Oct 15 2012;53(8):1584–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang A.L., Ulrich A., Suliman H.B., Piantadosi C.A. Redox regulation of mitophagy in the lung during murine Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. Free Radic Biol Med. Jan. 2015;78:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraft B.D., Chen L., Suliman H.B., Piantadosi C.A., Welty-Wolf K.E. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Demonstrate Mitochondrial Damage Clearance During Sepsis. Crit Care Med. May. 2019;47(5):651–658. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suliman H.B., Piantadosi C.A. Mitochondrial Quality Control as a Therapeutic Target. Pharmacol Rev. Jan. 2016;68(1):20–48. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang D., Nakayama T., Togashi M., et al. Two forms of diffuse alveolar damage in the lungs of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Hum Pathol. Nov. 2009;40(11):1618–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuo A, Tanida R, Yanagi S, et al. Significance of nuclear LOXL2 inhibition in fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in the fibrotic process of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Eur J Pharmacol. Feb 5 2021;892:173754. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173754 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Piantadosi C.A., Withers C.M., Bartz R.R., et al. Heme oxygenase-1 couples activation of mitochondrial biogenesis to anti-inflammatory cytokine expression. J Biol Chem. May 6. 2011;286(18):16374–16385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.207738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suliman H.B., Sweeney T.E., Withers C.M., Piantadosi C.A. Co-regulation of nuclear respiratory factor-1 by NFkappaB and CREB links LPS-induced inflammation to mitochondrial biogenesis. J Cell Sci. Aug 1 2010;123(Pt 15):2565–2575. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network Ventilation with Lower Tidal Volumes as Compared with Traditional Tidal Volumes for Acute Lung Injury and the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(18):1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/nejm200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amato M.B., Meade M.O., Slutsky A.S., et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. Feb 19. 2015;372(8):747–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1410639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briel M., Meade M., Mercat A., et al. Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. Mar 3. 2010;303(9):865–873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guerin C., Reignier J., Richard J.C., et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. Jun 6 2013;368(23):2159–2168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kellner M., Noonepalle S., Lu Q., Srivastava A., Zemskov E., Black S.M. ROS Signaling in the Pathogenesis of Acute Lung Injury (ALI) and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;967:105–137. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-63245-2_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chow C.W., Herrera Abreu M.T., Suzuki T., Downey G.P. Oxidative stress and acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. Oct. 2003;29(4):427–431. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.F278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Budinger G.R., Mutlu G.M., Urich D., et al. Epithelial cell death is an important contributor to oxidant-mediated acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Apr 15. 2011;183(8):1043–1054. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0181OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang M., Wang K., Deng G., et al. Mitochondria-Modulating Porous Se@SiO2 Nanoparticles Provide Resistance to Oxidative Injury in Airway Epithelial Cells: Implications for Acute Lung Injury. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020;15:2287–2302. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S240301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puri G., Naura A.S. Critical role of mitochondrial oxidative stress in acid aspiration induced ALI in mice. Toxicol Mech Methods. May. 2020;30(4):266–274. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2019.1710888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jamieson D., Chance B., Cadenas E., Boveris A. The relation of free radical production to hyperoxia. Annu Rev Physiol. 1986;48:703–719. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.003415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elkabany Z.A., El-Farrash R.A., Shinkar D.M., et al. Oxidative stress markers in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome: advanced oxidation protein products and 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine in relation to disease severity. Pediatr Res. Jan. 2020;87(1):74–80. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0464-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldwin S.R., Simon R.H., Grum C.M., Ketai L.H., Boxer L.A., Devall L.J. Oxidant activity in expired breath of patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet. Jan. 4 1986;1(8471):11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91895-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenz A.G., Jorens P.G., Meyer B., et al. Oxidatively modified proteins in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with ARDS and patients at-risk for ARDS. Eur Respir J. Jan. 1999;13(1):169–174. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13a31.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruchko M.V., Gorodnya O.M., Zuleta A., Pastukh V.M., Gillespie M.N. The DNA glycosylase Ogg1 defends against oxidant-induced mtDNA damage and apoptosis in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. May 1 2011;50(9):1107–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee Y.L., Obiako B., Gorodnya O.M., et al. Mitochondrial DNA Damage Initiates Acute Lung Injury and Multi-Organ System Failure Evoked in Rats by Intra-Tracheal Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Shock. Jul 2017;48(1):54–60. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fredenburgh L.E., Perrella M.A., Barragan-Bradford D., et al. A phase I trial of low-dose inhaled carbon monoxide in sepsis-induced ARDS. JCI Insight. Dec 6 2018;3(23) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.124039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suliman H.B., Healy Z., Zobi F., et al. Nuclear respiratory factor-1 negatively regulates TGF-beta1 and attenuates pulmonary fibrosis. iScience. Jan. 21 2022;25(1) doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Chung K.P., Hsu C.L., Fan L.C., et al. Mitofusins regulate lipid metabolism to mediate the development of lung fibrosis. Nat Commun. Jul 29 2019;10(1):3390. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11327-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheuerle A., Pavenstaedt I., Schlenk R., Melzner I., Rodel G., Haferkamp O. In situ autolysis of mouse brain: ultrastructure of mitochondria and the function of oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial DNA. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1993;63(6):331–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02899280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung M.I., Bujnis M., Barkauskas C.E., Kobayashi Y., Hogan B.L.M. Niche-mediated BMP/SMAD signaling regulates lung alveolar stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Development. May 11 2018;(9):145. doi: 10.1242/dev.163014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomashefski JF, Dail DH, Dail DH. Dail and Hammar's pulmonary pathology. 3rd ed. Springer; 2008:v. <1>.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.