INTRODUCTION

Dietary quality is a driver of overweight/obesity,1,2 malnutrition, other diet-related noncommunicable diseases3,4, and poor school readiness outcomes5 among preschool (3–5 years) children from low resource backgrounds.6,7 One-third of children entering Head Start, the federally funded preschool program that serves preschoolers and families from low-income backgrounds,8 are classified as overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 85th percentile), putting them at risk for the development of chronic diseases, lower self-esteem, and psychological and social distress. Combined, these factors are also associated with poor health and academic performance.9

One approach for improving children’s dietary intake is the repeated exposure strategy which focuses on offering children the same foods frequently.10,11 Unfortunately, the number of required taste exposures needed to impact children’s preferences for healthy foods, especially vegetables, is difficult to achieve, particularly for families from low resource backgrounds due to concerns about food waste.11,12 Head Start teachers are in a unique position to promote positive dietary behaviors daily to young children from families with low resources. Teachers have cited themselves as “parents at school” to indicate the significant impact they can have on children’s dietary quality13 through classroom experiences with food.14,15

Food-based learning (FBL) approaches that utilize the repeated exposure method to provide opportunities for children to explore fruits and vegetables have been demonstrated as effective for improving dietary quality.14–17 However, Head Start teachers reportedly face barriers to using FBL in the classroom such as limited time and competing school readiness priorities.18,19 Head Start teachers and administrators have previously suggested that these limitations could potentially be overcome by integrating nutrition into other learning domains (e.g., science, language) to simultaneously impact children’s dietary quality and school readiness outcomes.18 However, early childhood teachers have also expressed a need for professional development on how to effectively integrate FBL across domains.18,20,21

INTERVENTION DESCRIPTION

More PEAS Please! is a multi-level intervention that focuses on improving children’s dietary quality and school readiness (science knowledge and scientific language development) through early exposure and access to healthy foods in high-quality science learning environments. High-quality science learning environments provide developmentally appropriate hands-on, child-led, inquiry-based experiences for children and professional preparation and support for educators.22, 23 These environments engage and support the whole child with exploration and science inquiry.24 The More PEAS Please! intervention was developed by a team of multidisciplinary university faculty members with expertise in early childhood education and development, nutrition and nutrition education, language development and literacy, science education, and early childhood teacher professional development (PD).

Based on the Social Cognitive Theory25 (SCT) and Interconnected Model of Teacher Professional Growth26 (ICMTPG), the goal of our intervention is to improve the quality of children’s early language and science learning experiences by supporting teachers’ instructional practices focused on integrating nutrition into other learning domains (e.g., science, language) through FBL. SCT emphasizes agency, the sense of control over one’s actions and experiences, within an environment.25 Specifically, integration of SCT constructs enabled our team to examine the influence that individual experiences and environmental factors have on teacher practices. The ICMTPG presents teachers’ change and growth in their classroom/center environment through ongoing cycles of reflection and enactment through 4 domains (personal domain, external domain, domain of practice, and domain of consequences).26 The ICMTPG model is instrumental in understanding PEAS teachers’ learning trajectory and how this trajectory changes over time throughout their participation in the intervention.

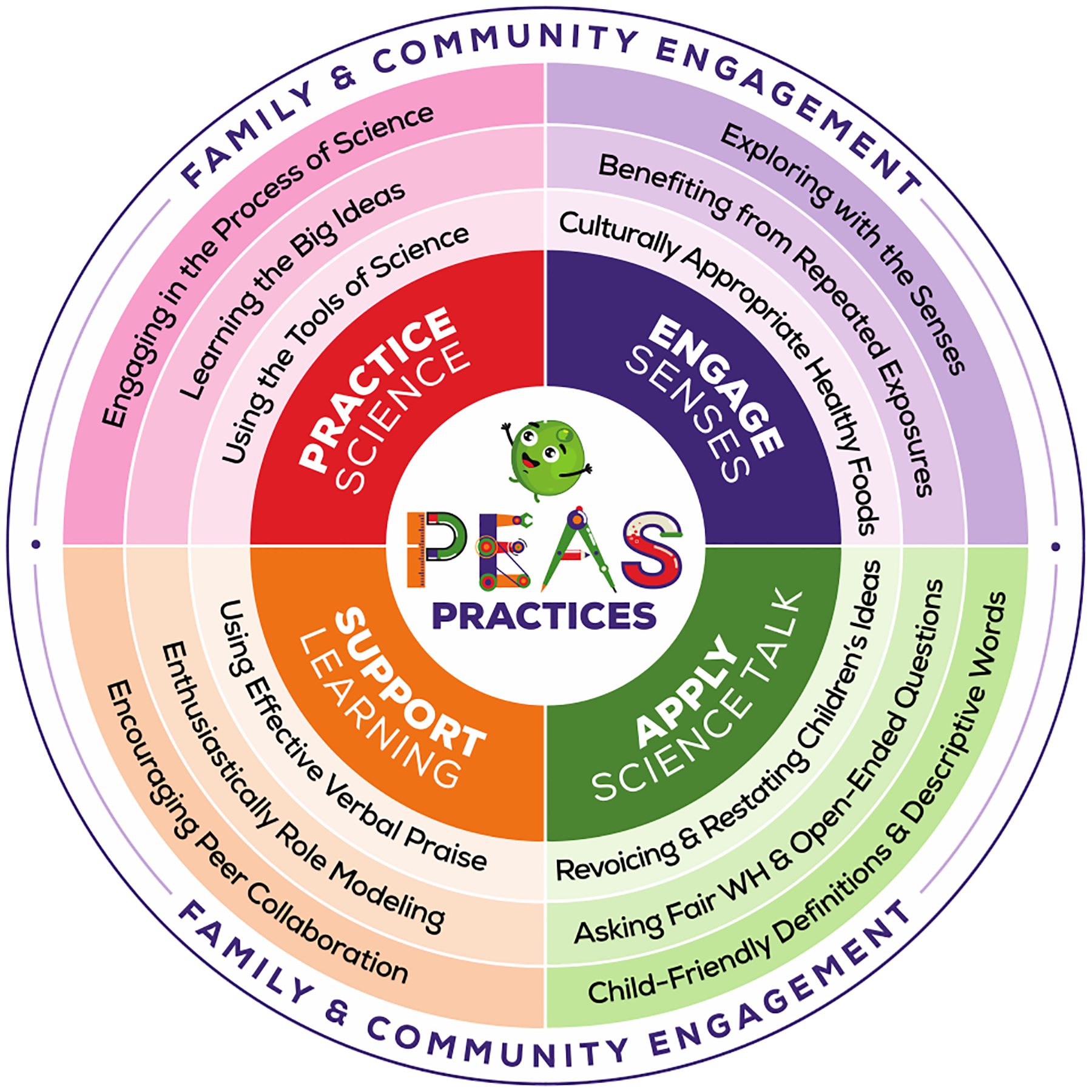

With an emphasis on evidence-based teaching practices, versus a conventional curriculum, each component of the intervention focuses on 1 of 4 areas: implementing high-quality science learning (Practice Science); engaging children in food-based experiences (Engage the Senses); developing language skills (Apply Science Talk); and supporting children’s learning using developmentally and culturally appropriate strategies (Support Learning) (Figure 1). Teachers were also encouraged to and provided with ideas on how to extend learning through family and community engagement, such as sharing classroom work with families and inviting parents and/or community members as guest speakers.

Figure 1.

Preschool Education in Applied Sciences (PEAS) Teaching Practices.

Teacher participation in More PEAS Please! consisted of 1) attending an initial 1-day training workshop 2) completing 6 learning modules (online or paper-based) 3) implementing 16 science learning classroom activities to practice key PEAS strategies using fresh vegetables and 4) receiving ongoing support from the research team and professional learning communities. Figure 2 describes the program’s components in more detail.

Figure 2.

Preschool Education in Applied Sciences (PEAS) Program Components.

The 1-day workshop introduced teachers to the program and our team during their in-service training prior to the start of the school year. As teachers progressed through the program, they watched engaging hand-drawn whiteboard videos for each learning module featuring the 3 evidence-based strategies for each of the PEAS Practices (Figure 1). Each module had 4 accompanying model science learning activities designed to support teachers’ ability to practice evidence-based strategies by integrating instruction on nutrition, science, and language in the classroom. Each module’s activities focused on a single topic (e.g., living versus non-living, seeds, plants, plant parts) and ended with an opportunity for children to taste test 4 target vegetables (carrot, tomato, spinach, and peas). Fresh vegetables were funded through Head Start’s participation in the Child and Adult Food Care Program, and we coordinated with Head Start Nutrition Managers to order food throughout the year. We provided environmental supports by improving the quality and variety of foods offered to children and teachers during meals and snacks27 and providing teachers with all materials, teaching guides, and instructions needed for the 16 PEAS model activities. These activities were designed to model science learning, support language development, promote school readiness, reduce teacher-identified barriers,18 and facilitate uptake by aligning with the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and Head Start’s Early Learning Outcomes Framework (ELOF).28,29 Furthermore, teachers received direct support from our research team during monthly virtual professional learning community (PLC) meetings. These meetings were teacher-driven, researcher-supported, and held on school-designated teacher workdays. Topics of discussion ranged from teachers’ current progress in the program to issues with modules and activities that teachers were encountering. Teachers who chose to participate in the PLC meetings were compensated an additional $15/meeting for their time. Working together with teachers, our research team brainstormed solutions for barriers teachers were encountering. In between PLC meetings, teachers received in-person, informal support from the project coordinator who communicated with teachers during site visits. The project coordinator followed up on issues discussed during PLC meetings, provided informal feedback on progress in the program, assisted teachers in writing goals, answered questions, and provided a general check-in for teachers.

The Institutional Review Board at East Carolina University reviewed and approved the study protocol under expedited review (IRB #21–001272). We obtained written consent from teachers. After consent was given, teachers were provided a brief demographic questionnaire where they were asked to self-report race and ethnicity from a list including White or European American, non-Hispanic; Latino(a), or Spanish; Black or African American, non-Hispanic; Asian or Asian American, non-Hispanic; American Indian or Alaskan Native, non-Hispanic; Middle Eastern or North African; Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; Multi-ethnic; or other (specify). Participants were allowed to select multiple responses to accurately reflect individuals’ self-designation. The demographic survey followed the US Office of Management and Budget protocols which guide the collection of race and ethnicity data in the US.30,31 Participants openendedly self-reported their gender. Demographic data were collected solely to describe the sample of participants. Regarding children’s participation in PEAS, caregivers gave implied permission. That is, caregivers were given IRB-approved documentation (informational letter to families, waiver of caregiver permission form) in English or Spanish, and caregivers signed and returned the document only if they did not want their child to participate. Due to the children’s age and following IRB protocols, child assent was not required. This article focuses primarily on the process evaluation of the project.

INTERVENTION EVALUATION AND RESULTS

We implemented the intervention over the course of the school year. A total of 24 Head Start teachers (lead and assistant) from 4 centers located in 3 Eastern North Carolina counties participated in the pre-service workshop at the beginning of the school year. Approximately 227 children within the 13 participating classrooms engaged in the 16 food-based science model learning activities during the intervention over the course of 5 months. Nineteen teachers completed all 6 teacher training modules, and 5 additional teachers completed at least 1 of the teacher-training modules. All participants (n=24) were female and were an average age of 46 ± 11.53 years at the time of the intervention. Teachers’ races were predominantly Black/African American (87%) followed by White (4%). Teachers’ ethnicities were non-Hispanic (91%). Many teachers held either an associate’s (52%) or a bachelor’s (30%) degree. Teachers had been working at Head Start for an average of 7 ± 6.21 years.

Our evaluation consisted of formative and summative components, including a formative teacher survey after each training module, a summative teacher survey at the end of the program, and in-depth telephone interviews. The measurement instruments used in this evaluation were either derived from previous existing instruments, in-depth interviews with Head Start teachers32–34, a smaller pilot of the FBL featured in the intervention,35 or developed by our team. A professional panel of 4 faculty with expertise in early childhood nutrition education and feeding, early childhood education, teacher PD, early science education, early language development, and program evaluation examined and evaluated the instruments for face and content validity. Additionally, we conducted cognitive interviews with 3 Head Start teachers and revised our interview questions to improve clarity based on the findings from this step. In the next paragraphs, we will present our survey results with descriptive statistics and frequencies of response type and findings from our qualitative phenomenological analysis.36

In the formative surveys using open and closed-ended questions, we asked teachers for feedback regarding the information and resources presented, which model science learning activities they taught (or why they could not teach the activities), and what difficulties and supports they encountered during that module. Approximately 83% of teachers (n=19) completed all the formative surveys. Teachers’ responses revealed that lack of time in teachers’ schedules was the most difficult challenge in implementing the intervention across modules. In addition, the most important support teachers experienced was children’s interest in the topic.

In the summative survey, teachers were asked to rate the helpfulness of each resource and PEAS activity, the program’s impact on their ability to teach science education, the program overall, and if they would continue to use or recommend PEAS teaching practices and programs to others. Nineteen teachers completed the summative survey. Teachers’ responses indicated that teachers found value in the program, which positively impacted their science teaching practices, and that they were likely to continue using the integrative teaching strategies. This analysis revealed that the most helpful resources for teachers were the teaching videos (27.8%) and the PEAS Teaching Guide with model science learning activities (27.8%). The least helpful resource was the on-demand learning modules on the online platform (33.3%), likely due to researcherobserved challenges with technology (e.g., reliable Wi-Fi access, teachers’ prior experience, and comfort with online learning). Teachers reported that the most valuable program incentive was access to the PEAS training resources (e.g., PEAS Teacher Guide and electronic resources on the program website) (38.9%) and the new science materials for their classroom (33.3%), followed by the gift cards (16.7%) and access to food for science activities at their center (11.1%). All teachers agreed or strongly agreed that the program positively impacted their ability to provide engaging science using healthy foods as a teaching tool. Half of the teachers who implemented PEAS rated their overall experience as excellent and the other half rated it good. All teachers were highly likely (HL) or likely (L) to continue using the teaching strategies: Practice Science (55.6% HL, 44.4% L), Engage the Senses (61.1% HL, 38.9% L), Apply Science Talk (61.1% HL, 38.9% L), and Support Learning (55.6% HL, 44.4% L). Most teachers said they were highly likely (38.9%) or likely (44.4%) to recommend PEAS to other teachers they know while 3 teachers (16.7%) said they were highly unlikely to recommend it to others. Most teachers (77.8%) preferred to complete the modules using paper copies instead of the online platform; both formats featured identical content.

Teachers were also given the opportunity to engage in a 60-minute in-depth telephone interview to discuss their experiences with the program. Interviews were conducted by a trained researcher, recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Two trained qualitative researchers independently completed open coding and identified initial overarching themes using a phenomenological approach. Phenomenology seeks to understand how human beings experience a phenomenon or the common lived experience of a group.36 Interviews (n=17) revealed teachers initially felt time was a barrier, but as they progressed through the modules, time became less of an issue. Teachers were motivated by children’s enthusiasm for learning and hands-on food exploration, including observing improvement in children’s willingness to try vegetables during taste-testing opportunities. Teachers suggested we increase the variety of foods presented in model science learning activities beyond the 4 selected vegetables (carrot, tomato, spinach, peas). Teachers expressed that PEAS improved their confidence in teaching science, and although children are naturally curious about scientific inquiry, teachers were surprised by children’s enthusiasm, capability, and retention of science concepts. Teachers’ feelings of surprise may reflect their initial beliefs and self-efficacy about science education in early childhood.37 Overall, teachers identified the PEAS technical and administrative team as a major support in their ability to engage in PEAS. Teachers commented that the COVID-19 pandemic continued to burden their engagement with the program and daily classroom routines (e.g., the class being out for 2 weeks due to a positive case in child/teacher). Teachers stated that the COVID-19 pandemic increased teacher feelings of burnout, which likely also impacted their PEAS experience and level of engagement with the program.

Lastly, teachers described using PEAS as a model for their learning and implementation. Throughout the program, teachers learned PEAS strategies, set goals to use PEAS strategies, and delivered activities to practice PEAS strategies. Teachers stated they would be likely to use each of the strategies in the future after the program ended.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

Prior studies examining Head Start teachers’ experience using food in the classroom suggest that limited time is a common barrier to FBL.18 Program evaluation of More PEAS Please! revealed that limited time continues to be a barrier to completing the intervention. However, as teachers became more familiar with the program and training resources, they verbally acknowledged that the magnitude of this challenge declined over time, as noted in the qualitative interviews. While teachers acknowledged barriers in implementing the program, they also emphasized that the continued PEAS technical and administrative support that they received during PEAS’ implementation was key to their successful progression through the program. Considering the future dissemination of the project sustained programmatic support for Head Start teachers will be critical for teacher retention, satisfaction, and program success.

Identification, consideration, and responsiveness to teachers’ needs were critical for the success of the program. For example, our learning modules were originally created to be implemented as on-demand, online-only modules based on Head Start teachers’ and administrators’ input prior to designing program materials. However, once the intervention began, many teachers experienced barriers to accessing online modules (e.g., trouble accessing a reliable Wi-Fi signal at their center, low technological proficiency, and a work policy regarding phone use). These barriers prompted us to convert all online materials to be available on paper shortly after the intervention began. Our data support the need to consider multiple modalities of program delivery to better meet teachers’ individual needs when engaging Head Start teachers in future programs.

Teachers requested an increase in the variety of fruits and vegetables featured in the program’s taste-testing opportunities. Originally, we chose 4 target vegetables to be featured throughout the 16 model science learning activities and taste tests to ensure that sufficient repeated exposure was achieved.10,11 Prior research suggests that repeated exposure to a vegetable can improve preference and consumption of vegetables as a whole.38 However, future research is warranted to determine if exposure to a variety of vegetables (repeated exposure, but not to the same vegetables to increase variety) will still positively impact preference and consumption towards all fruits and vegetables.

Acknowledgments:

The research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R25GM132939. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The Institutional Review Board of East Carolina University approved all study protocols (UMCIRB 21-001272). Teachers were recruited to participate in the pilot evaluation of the program on the first day of the PEAS Institute kick-starter pre-service workshop. Teachers were informed of the study purpose, what types of questions would be asked, the consenting process, the incentive, and the timeline for completing pilot evaluations. Teachers deciding not to participate in the pilot evaluation of the intervention were not excluded from participating in the program. Teachers who expressed interest in participating in the pilot study provided electronic consent through REDCap. Teachers received a gift card compensation (up to $120) for participating in PLC activities, completing program evaluation surveys at baseline, during, and post-intervention, and volunteering for an in-depth post-interview. The project was funded by a 5-year National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (www.nihsepa.org) (Award # R25GM132939). Special thanks to Nita Davis Edwards for her technical support assistance as well as the Head Start Center Directors at each site for their continued support of the program. The PEAS program materials are available for free on the More PEAS Please! website (www.morepeasplease.org). Whiteboard training videos can be found on the More PEAS Please! YouTube channel (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC92_74taZy9ocXKgv0yVATQ/videos).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Virginia C. Stage, Nutrition Education & Behavior Specialist, Director of the Food-based Early Education (FEEd) Lab, Department of Agricultural & Human Sciences, North Carolina State University, NC State Extension, 4101 Beryl Road, Raleigh, NC.

Jessica Resor, Department of Nutrition Science, College of Allied Health Sciences.

Jocelyn Dixon, Department of Nutrition Science, College of Allied Health Sciences.

Archana V. Hegde, Department of Human Development and Family Science, College of Health and Human Performance.

Lucía Mendez, Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, University of North Carolina Greensboro.

Tammy Lee, Department of Science Education, College of Education.

Raven Breinholt, College of Nutrition Science.

L. Suzanne Goodell, Department of Food, Bioprocessing & Nutrition Sciences, North Carolina State University.

Valerie McMillan, Department of Family and Consumer Sciences, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller AL, Lumeng CN, Delproposto J, Florek B, Wendorf K, Lumeng JC. Obesity-Related Hormones in Low-Income Preschool-Age Children: Implications for School Readiness. Mind, Brain, and Education. 2013;7:246–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Datar A, Sturm R. Childhood overweight and elementary school outcomes. IJO. 2006;30:1449–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreyeva T, Kenney EL, O’Connell M, Sun X, Henderson KE. Predictors of nutrition quality in early child education settings in Connecticut. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50(5): 458–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dev DA, McBride BA, Speirs KE, Donovan SM, Cho HK. Predictors of Head Start and child-care providers’ healthful and controlling feeding practices with children aged 2 to 5 years. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014; 114(9):1396–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burrows T, Goldman S, Pursey K, Lim R. Is there an association between dietary intake and academic achievement: a systematic review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30:117–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skouteris H, Bergmeier HJ, Berns SD, Betancourt J, Boynton-Jarrett R, Davis MB, Gibbons K, Pérez-Escamilla R, Story M. Reframing the early childhood obesity prevention narrative through an equitable nurturing approach. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17:e13094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumanyika SK. A framework for increasing equity impact in obesity prevention. AJPH. 2019;109:1350–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Office of Head Start, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services. About the Office of Head Start. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ohs/about. Accessed October 22, 2022.

- 9.Taras H, Potts-Datema W. Obesity and student performance at school. J School Health. 2005;75:291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nekitsing C, Hetherington MM, Blundell-Birtill P. Developing healthy food preferences in preschool children through taste exposure, sensory learning, and nutrition education. Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7:60–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson S. Developmental and Environmental Influences on Young Children’s Vegetable Preferences and Consumption. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:220–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert Wood Johnson Healthy Eating Research (October 2021). Evidence-based Recommendations and Best Practices for Promoting Healthy Eating in Children 2 to 8 Years. Technical Report. https://healthyeatingresearch.org/research/evidence-basedrecommendations-and-best-practices-for-promoting-healthy-eating-behaviors-inchildren-2-to-8-years/. Accessed September 6, 2022.

- 13.Mita SC, Li E, Goodell LS. A qualitative investigation of teachers’ information, motivation, and behavioral skills for increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in preschoolers. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;January;45:793–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Battjes-Fries MC, Haveman-Nies A, Zeinstra GG, van Dongen EJ, Meester HJ, van den Top-Pullen R, van’t Veer P, de Graaf K. Effectiveness of Taste Lessons with and without additional experiential learning activities on children’s willingness to taste vegetables. Appetite. 2017;1:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dazeley P, Houston-Price C, Hill C. Should healthy eating programmes incorporate interaction with foods in different sensory modalities? A review of the evidence. BJN. 2012;108:769–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellows LL, Johnson SL, Davies PL, Anderson J, Gavin WJ, Boles RE. The Colorado LEAP study: rationale and design of a study to assess the short term longitudinal effectiveness of a preschool nutrition and physical activity program. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whiteside-Mansell L, Swindle T, Davenport K. Evaluation of “Together, We Inspire Smart Eating” (WISE) nutrition intervention for young children: assessment of fruit and vegetable consumption with parent reports and measurements of skin carotenoids as biomarkers. JHEN. 2021;16:235–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carraway-Stage V, Henson SR, Dipper A, Spangler H, Ash SL, Goodell LS. Understanding the state of nutrition education in the Head Start classroom: a qualitative approach. Am J Health Educ. 2014;45:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes CC, Gooze RA, Finkelstein DM, Whitaker RC. Barriers to obesity prevention in Head Start. Health Affairs. 2010;29:454–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotugna N, Vickeryn C. Educating early childhood teachers about nutrition. J Res Child Educ. 2012;83(4):194–198. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rapson J, Conlon C, Ali A. Nutrition knowledge and perspectives of physical activity for pre-schoolers amongst early childhood education and care teachers. Nutrients. 2020;12(1984): 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashbrook P (2019, June 24). Six key themes in early childhood science: The NAEYC ECSIF presents at a science education conference. NAEYC. Retrieved October 23, 2022 from https://www.naeyc.org/resources/blog/six-key-themes-in-early-childhood-science. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClure E, Guernsey L, Clements D, Bales S, Nichols J, Kendall-Taylor N, Levine M. How to integrate STEM into early childhood education. Sci. Child 2017;55(2): 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Association for the Education of Young Children. Developmentally appropriate practice (DAP). https://www.naeyc.org/resources/developmentally-appropriate-practice/. Accessed October 23, 2022.

- 25.Bandura A (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 3:143–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clarke D, & Hollingsworth H Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2002;18:947–967. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ward D, Morris E, McWilliams C, Vaughn A, Erinosho T, Mazzuca S, Hanson P, Ammerman A, Neelon S, Sommers J, Ball S. Go NAP SACC: nutrition and physical activity self-assessment for child care. Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention and Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.NGSS Lead States. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/schoolreadiness/article/head-start-early-learning-outcomes-framework. Accessed October 22, 2022.

- 30.Díaz Rios LK, Stage VC, Leak TM, Taylor CA, Ricks M. Collecting, using, and reporting race and ethnicity information: Implications for research in nutrition education, practice, and policy to promote health equity. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2022;54(6):582–593. 10.1016/j.jneb.2022.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Standards for maintaining, collecting, and presenting federal data on race and ethnicity. Federal Register. (2016, September 30). Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/09/30/2016-23672/standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and-presenting-federal-data-on-race-and-ethnicity [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huye HF, Connell CL, Crook LB, Yadrick K, Zoellner J. Using the RE-AIM framework in formative evaluation and program planning for a nutrition intervention in the lower Mississippi delta. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46:34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dev DA, Padasas I, Hillburn C, Carraway-Stage V, Dzewaltowski DA. Using the RE-AIM Framework in Formative Evaluation of the EAT Family Style Multilevel Intervention. 2020. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-87491/v1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma SV, Chuang RJ, Byrd-Williams C, Vandewater E, Butte N, Hoelscher DM. Using Process Evaluation for Implementation Success of Preschool-Based Programs for Obesity Prevention: The TX Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration Study. Journal of School Health. 2019;89:382–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bayles J, Peterson AD, Pitts SJ, Bian H, Goodell LS, Burkholder S, Hegde AV, Stage VC. Food-based Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics (STEAM) learning activities may reduce decline in preschoolers’ skin carotenoid status. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2021;53:343–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahern SM, Caton SJ, Blundell P, Hetherington MM. The root of the problem: increasing root vegetable intake in preschool children by repeated exposure and flavour flavour learning. Appetite. 2014;80:154–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerde HK, Pierce SJ, Lee K, Van Egeren LA. Early childhood educators’ self-efficacy in science, math, and literacy instruction and science practice in the classroom. Early Education and Development. 2018;2:70–90. [Google Scholar]