1. Introduction

To a physicist, proton radiation therapy is fascinating at many levels. There is arguably more interesting physics involved in proton and particle therapy than in radiation therapy with photons. There is a lot more innovation happening in proton therapy too, and it is more dynamic with many new companies entering the field, and some leaving. For example, while the accelerator technology in photon therapy has not fundamentally changed since the 1970s, there are new ultra compact synchrocyclotrons, synchrotrons, high gradient linear accelerators, and laser wakefield accelerators in proton and particle therapy. The ability to make the proton “radiation scalpel” visible through its activation of oxygen-15 and carbon-11 isotopes, and the generation of prompt gamma radiation is unique. Then there is the technology aspect, the ability to control giant 100 ton devices with sub millimeter precision. Proton and particle therapy is the biggest and most expensive technology used in all of medicine. While it can be a thrill to be in charge of $100 million equipment, there is also the challenge and opportunity to democratize the technology, to shrink its size and price substantially in order to make it affordable for many more patients. To the medical physicist trying to maximize the benefit for individual patients, it is encouraging to see the results of recent clinical trials showing improved outcomes of proton therapy. Thanks to a steady stream of innovations, proton therapy has been on an exponential growth path for more than 6 decades, and there is no sign that it will stop growing anytime soon.

We are writing this article from the perspective of a senior and a junior medical physicist. We are not attempting to write a comprehensive review. Instead, following the spirit of this special issue, we are focusing on our own personal experiences and interests. We are hoping to convey where we are coming from and where our journey is heading, while sharing our excitement along the way.

2. Part A (Thomas Bortfeld)

During the very early stages of my career, I was quite skeptical about the benefit of proton therapy. Working on my PhD thesis in Heidelberg on inverse planning and optimization of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) with Wolfgang Schlegel as advisor in 1988–1990, I was adamant about showing that with optimized planning, IMRT with photons can produce dose distributions that are as good or better than proton dose distributions. My point was that the proponents of proton therapy oversell its physical advantage by bragging too much about the Bragg peak: Virtually every textbook and introductory lecture about proton therapy starts with a one-dimensional comparison of the Bragg curve with the clearly inferior exponential dose fall-off in photon therapy. However, such a comparison is misleading because the dose conformation problem in radiation therapy is of course a three-dimensional problem. The lateral dose fall-off (in x- and y-direction) is about as sharp, if not sometimes sharper, in a photon beam compared to a proton beam. The ability to create a sharp dose edge on one side (in one dimension) is sufficient to carve out an arbitrarily shaped high dose region to match any tumor target volume, assuming that many coplanar or non-coplanar beams can be combined. This follows from the theory of the Radon transform, which is also underlying image reconstruction principles in computed tomography. In other words, the Bragg peak is not necessary to achieve dose conformality of the high dose region. With that said, it also follows from first principles that since no dose is delivered beyond the Bragg peak, the average dose to surrounding healthy tissues – termed the “dose bath” by Michael Goitein – is reduced by at least a factor of 2.

In subsequent years I learnt to appreciate that a substantial reduction of the radiation dose bath is an important advantage of proton beams, especially because patients tend to survive their cancer diagnosis for many more years than back in the 1970s, making side effects less acceptable. Secondly, combination therapies such as chemo-radiation and (today) also radiation combined with immunotherapies have become the standard of care for many types of cancer, meaning that radiation dose thresholds in normal tissues have to be re-assessed. I changed my mind about the importance of the Bragg peak: it is important, even though not as important as the one-dimensional comparison with the exponential dose fall-off in photon beams suggests.

In 1995 I investigated the theoretical and practical dose shaping potential of photon and proton beams as part of my habilitation thesis – a second PhD thesis required to obtain a professorship in Germany – in the physics department of the University of Heidelberg. Around the same time, we started a close collaboration between the German Cancer Research Center and the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland, primarily with Tony Lomax, to perform a solid intercomparison study between advanced IMRT plans with photons, and proton treatment plans. The collaboration turned into a friendly rivalry, pushing the plans achieved with both modalities to the Pareto frontier, i.e., to their physical limit. The study revealed that proton therapy affords a dose bath reduction of close to a factor 3, not “just” a factor of 2. We also learnt that intensity modulation is crucially important to take full advantage of the dose shaping potential of both photon and proton beams.

2.1. The mathematical beauty of the Bragg peak

While working on photon and proton dose distributions in the mid 1990s, it occurred to me that simple approximations of photon depth dose distributions, usually just exponentials, are often useful in modeling and understanding the dose shaping potential of photon beams [1]. On the other hand, no closed form expression of the proton Bragg curve existed at that time. It turned out, however, that it is quite straight-forward to derive an analytical expression of the Bragg curve as follows:

According to the Bethe Bloch equation, the stopping power of protons in tissue is approximately inversely proportional to the square of the velocity of the protons, which means it is roughly inversely proportional to their kinetic energy: . The more the protons slow down, the more energy they lose in a certain depth interval, which is the whole reason why the Bragg peak comes about. Consequently, the depth increment ∂z per energy loss −∂E is proportional to the energy: . By integration we obtain the range-energy relationship: −z ~ E2. This means that the stopping power as a function of the depth is for z ≤ 0.

This derivation assumes that all protons stop at the same depth, z = 0. Range straggling leads to an approximately Gaussian spread of the range. This is modeled by convolving the stopping power from above with a Gaussian range straggling distribution, which yields the Bragg curve in the functional form . Here 𝒟−1/2(z) is a parabolic cylinder function, a special function. As a math nerd I find a certain elegance and beauty in this functional form and in the corresponding shape of the Bragg curve, shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Functional form of the Bragg curve (solid line) derived from first principles, as a convolution of a power-law function describing the stopping power at depth z, with a Gaussian range straggling distribution. 𝒟−1/2(z) is a parabolic cylinder function, a special function. The dotted curve is without range straggling.

Despite the many approximations and simplifications made, the simple model above approximates both measured and more accurately calculated Bragg curves surprisingly well. This is especially true when the exponent in the range-energy relationship is lowered from 2 to about 1.8, to take the logarithmic term in the Bethe Bloch equation as well relativistic effects into account.

The type of function defined as the product of a parabolic cylinder functions and a Gaussian, which we later called function, has characteristics that lends itself to several other useful applications. One such characteristic is that the convolution of two functions is another function. For example, we used it to rapidly calculate the expected PET image resulting from the activation through a proton beam, simply by convolving the dose distribution with a function (filter). In another study, we used it to directly reconstruct the dose distribution from a measured PET image, by de-convolving it with a function. Currently we apply these concepts to prompt gamma imaging.

2.2. Taking full advantage of the finite range

By the year 2000 I was under the impression that the bulk of the IMRT research was completed and there were more future opportunities in proton therapy. In 2001 I accepted a position as the physics research director at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and moved to the United States. Despite discouraging comments from some colleagues saying that refocusing more on proton therapy was the biggest mistake of my career, the times were exciting. Clinical treatments at the new Northeast Proton Therapy Center, the second hospital based proton center in the world (today there are over 100), were just about to start after I arrived. My boss George Chen put me in charge of the physics projects in a program project grant (P01) on proton therapy that was initiated 25 years earlier by the giants in the field, Michael Goitein and Herman Suit. Trying to develop a research theme to take the research program forward, I zoned in on the range uncertainty problem. It does indeed seem absurd that the finite range of the proton beam, which is its primary physical advantage, cannot be used to protect organs at risk because of the substantial (order of centimeter) range uncertainties. Reducing range uncertainties seemed like a worthwhile goal and it did provide a strong research focus in the following years and until today, both for the group at MGH and many other groups around the world.

Arguably the best way to reduce range uncertainties is to measure – and if necessary correct – the proton range directly in the patients under treatment. Having been loosely involved in the carbon ion therapy research project at the GSI in Darmstadt Germany, I knew that positron-emission-tomography (PET) imaging can be used to visualize the activation of tissue after irradiation with carbon ions, showing where the dose was actually delivered. Earlier work by other groups suggested that the same could be possible in proton beams, but it was unclear how clinically viable this approach could be. Starting in 2004 we ran a clinical study of PET scanning after proton treatment with support from Katia Parodi, who had just finished her PhD thesis on a related topic at the University of Dresden. First we used a PET scanner in the radiology department, later a mobile PET scanner in the treatment room, which could capture the shorter lived oxygen-15 signal. Results were promising but millimeter precision in assessing the proton range turned out to be very hard if not impossible to achieve, due primarily to: biological washout of the signal, overall low signal-to-noise-ratio, and the fact that there is no signal at the very end of the range because of the activation threshold of approximately 20 MeV.

For the next round of P01 funding, which was pursued in collaboration with colleagues from the new proton center at the MD Anderson Cancer Center (physicists including Radhe Mohan and Lei Dong), we set ourselves the ambitious goal to reduce range uncertainties to 1 mm. This was supposed to be accomplished by combining various imaging techniques including dual energy computed tomography (DECT) to get a handle on the proton stopping power, and magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) to measure tissue changes as a result of the radiation dose delivery. A related new idea was to measure the prompt gamma radiation that is produced in the nuclear interactions of protons with tissue, as opposed to measuring the β+ decay in a PET scanner. A talented PhD student, Joost Verburg, almost single-handedly designed and built a prompt gamma spectroscopy device that has later been deployed in the clinic [2].

In spite of all these efforts, we have not fully achieved the goal of measuring the proton range with 1 mm precision in patients, let alone the reduction of range uncertainties to that level. The problem is exacerbated by uncertainties of the relative biological effectiveness (RBE) near the end of range, which is a whole other research domain spear-headed by my colleague Harald Paganetti and his team. The use of the distal end of the proton Bragg peak for dose shaping therefore remains elusive. To put it positively though, we have a great opportunity for future research on our hands.

2.3. Solving challenging treatment planning and plan optimization problems

One thing we learn as physicists from early on is not to shy away from big challenges but to take them as opportunities. Proton therapy is full of those opportunities. Looking at the treatment planning problem, plan optimization in intensity modulated proton therapy (IMPT) is not fundamentally different from the corresponding problem in IMRT with photons. Since multileaf collimators (MLC) are not as essential in proton therapy as in IMRT, the beam intensity maps can be used more or less directly for the delivery with pencil beam scanning, making treatment planning actually simpler. However, there are several additional challenges/opportunities in proton therapy planning: first, there are more variables because for each beam direction we have to determine not only the intensities but also the energies. Secondly, the smaller pencil beam size can lead to more severe interplay between the beam delivery sequence and the motion of inner organs during the treatment, making “4D” temporo-spatial planning more critically important. Third, while the relative biological effectiveness adds a layer of uncertainty, we can take advantage of including the linear energy transfer (LET) in the optimization of the spatial dose distribution. Last and perhaps most importantly, range uncertainties pose a unique planning challenge.

In 2008 I became the chief of the physics division in radiation oncology at MGH. This came with its own challenges and meant that I had less time for research. However, I had the good fortune that I could continue to work with an enormously talented group of colleagues in research. And I could build upon strong collaborations with optimization experts in the field of operations research (OR) and in industry, which I had developed during my IMRT optimization work. In the 2000s, robust optimization had turned into a hot topic in OR. It became apparent that the concepts developed there could be applied to tackle the range uncertainty problem in proton therapy. The aim was to come up with an optimal treatment plan that is protected against uncertainties. In practice we defined many treatment delivery scenarios including range over- and undershoot, and determined the best plan in the worst scenario, or the best plan with respect to the expected value of the objective function taken over all scenarios [3]. Robust optimization has since been included in commercial treatment planning systems and is routinely applied in proton therapy. Robust optimization cannot, however, work miracles. One has to pay a price in terms of reduced plan quality for protecting a treatment plan against uncertainties through robust optimization. This is called the price of robustness.

Adaptive treatment planning performed multiple times during the course of the treatment or even on a daily basis, is a way to reduce variabilities and uncertainties, and it is more important in proton therapy than in conventional radiation therapy. Several efforts to facilitate adaptive proton planning, heavily utilizing artificial intelligence, are currently underway. The quintessential way of doing adaptive planning and delivery is real-time adaptation. Together with Robert Jeraj and Mark Plesko, I initiated the Marie Skłodowska–Curie innovative training network RAPTOR (Real-Time Adaptive Particle Therapy) of the European Union, which started in 2021 and has already grown into a highly successful program. My hope is that the results of this program will enable the democratization of proton therapy (chapter 3) through flexible yet accurate and precise positioning of the patient relative to a fixed beam.

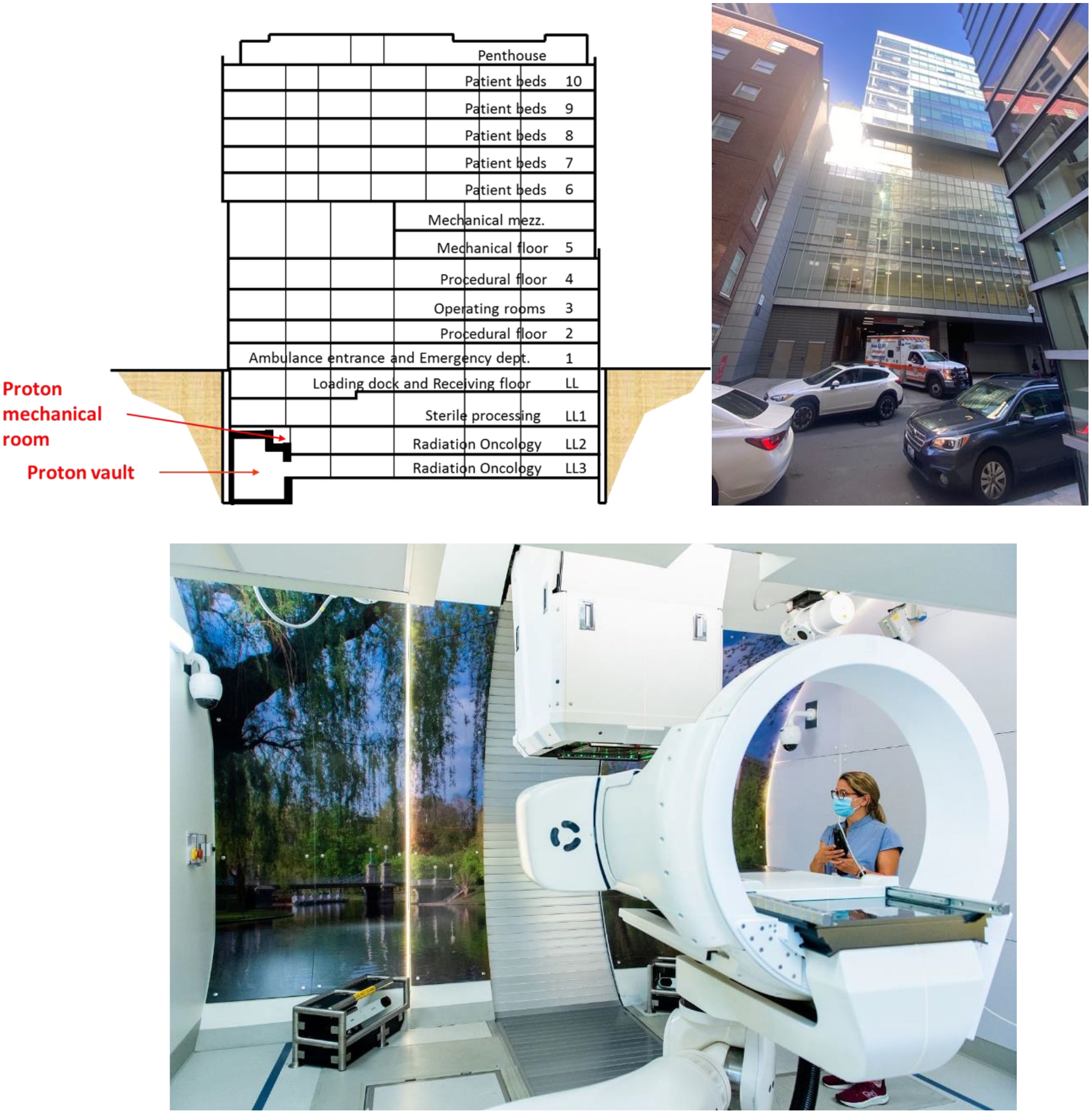

2.4. Retrofitting proton therapy in an existing building

A key milestone towards making proton therapy more affordable is to integrate proton systems in existing buildings, instead of constructing dedicated new buildings on previously undeveloped land (“greenfield” sites). In 2013 it was decided that the MGH needed more proton treatment capacity, and that it had to be on the main campus, near the existing proton therapy center. Space was available in a recently completed building with two empty bunkers originally designated as treatment rooms for photon radiation therapy with linear accelerators (linacs). The rooms were located on the lower level 3 below the surface, without direct access from above or from the sides. The only way to bring equipment into these rooms was through existing elevators and hallways. This restriction left a synchrotron with its smaller components as the only option for the accelerator, to be placed in one of the linac bunkers. The other bunker could house a compact half-gantry. After an extensive planning phase and surmounting many challenges related to installing this system in a busy clinic just below the emergency department, the first patient was treated at the beginning of 2020 [4]. I am exciting about this accomplishment because it paves the way for future “democratization” of proton therapy, as Susu Yan will describe in the next chapter.

3. Part B (Susu Yan)

In 2008 when I was a junior undergraduate, I went on a weekend trip to Boston with college friends. We were wandering on the MIT campus to explore. I was a physics major with interests in engineering. The cool research labs and the CSAIL building were unbelievable and eye-opening. I saw a robotics lab, with fascinating robotics arms, and electronics. I took a photo, dreaming that maybe one day I can work on innovative technology which will make great positive change to the world. I later actually worked on a robot during my medical physics PhD study at Duke University, developing an on-board SPECT imaging system in which the detector is attached to a robotic arm.

When I was accepted to the medical physics residency program at Harvard in 2014, I had the great opportunity to work with Drs. Thomas Bortfeld, Hsiao-Ming Lu and Jay Flanz on a proton therapy project as my first-year residency research. At that time, the number of proton centers around the world was limited, and it was the first time I started to have a deeper understanding of this treatment. Working with an exclusive treatment technique, as well as the complexity of such a treatment system, was very exciting. One of the interesting side effects of working on this project was that when talking to new friends in Boston about my work, the first word often was “wow”. This system, treating cancer patients with a proton beam, is astonishing. And even more surprising to them is that there is a system like this under the ground in the center of Boston. The enthusiasm of the lay person seems greater than that of the radiation oncology field.

My first project was to analyze 10 years of proton treatment data to investigate whether the proton gantry was fully used or not. If the gantry was not fully used, we could consider removing it, and developing the technology to facilitate a gantry-less proton system. This could greatly reduce the cost and size of the proton system. The results were exciting: we found that most of the beam angles can be achieved without a gantry if we can move the patient to sitting, lying or reclined positions. This work led us to further develop a patient positioner, immobilization device and imaging system that can facilitate a gantry-less, fixed beam-line proton system [5].

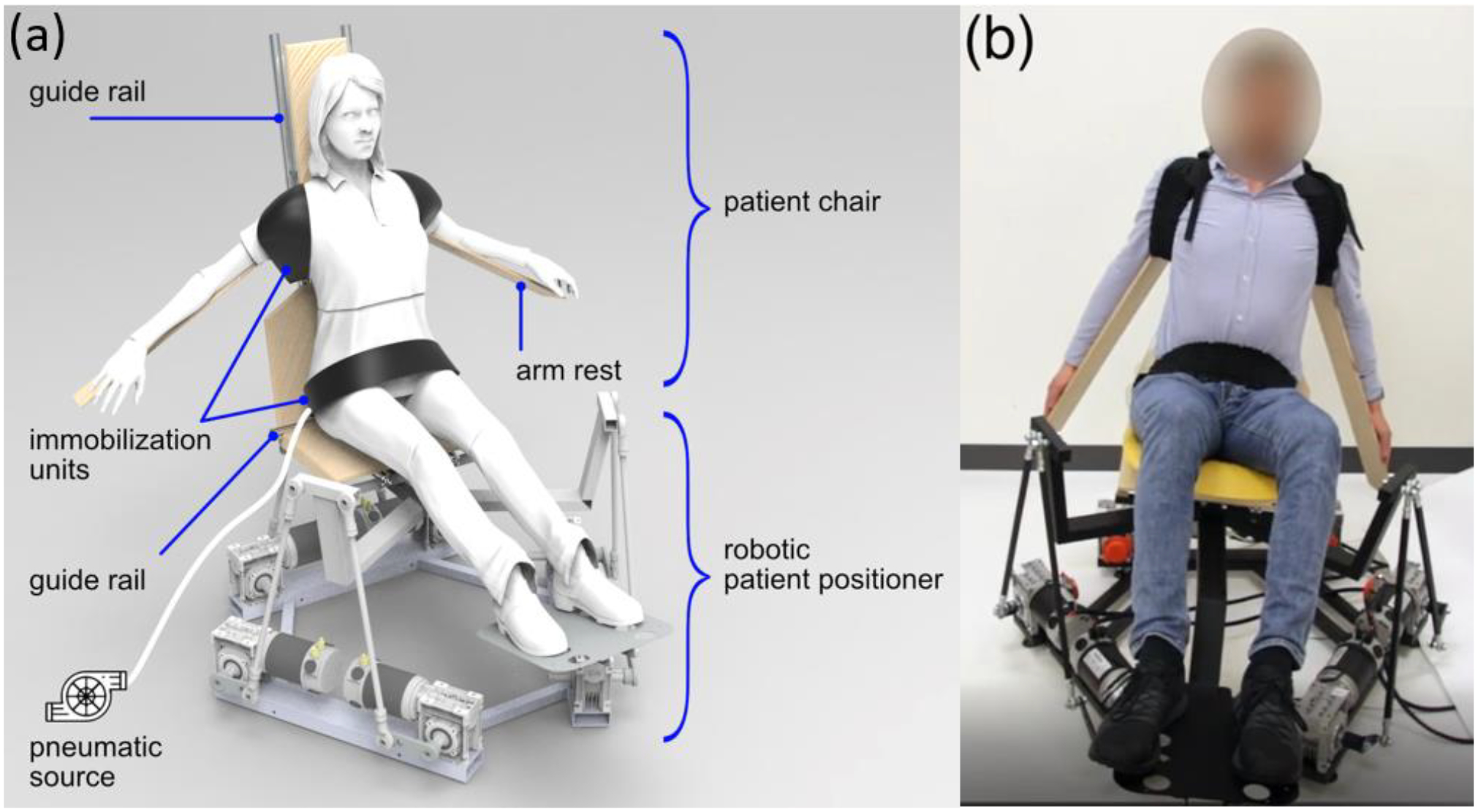

A collaboration with the MIT CSAIL department, Drs. Daniela Rus and Shuguang Li, on the patient positioner and immobilization device illustrates the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in the new era of research. We adapted their advanced robotic technology to radiation therapy, developing a soft robotic patient immobilization device which can be universally applied to various patient body shapes (Figure 4). It is soft and comfortable but strong enough to immobilize volunteers in sitting or reclined position to the current clinical standards. Personally, I was thrilled to work actively with the Rus Lab that I visited 10 years earlier as an undergraduate student - my dream came true!

Figure 4:

The patient positioner and immobilization device designed for compact gantry-less proton system. (a) A schematic drawing of three soft immobilization units attached to chair top which is mounted on a robotic positioner base (from Buchner T et al. A soft robotic device for patient immobilization in sitting and reclined positions for a compact proton therapy system. 8th IEEE RAS/EMBS International Conference for Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics, 2020:981–988). (b) A volunteer study was performed. The vacuum driven immobilization unit is contracted to the volunteer shoulder and abdominal region. The robotic positioner base is rolled at 8.6 degree. The immobilization units fix the volunteer position on the chair.

Now the even bigger dream is to retrofit a compact proton system to a conventional LINAC sized room. This is quite challenging, but maybe in another 10 years, many more centers around the world will have a LINAC-room sized proton system that is easy to install and maintain. From the accelerator and beam-line design to patient positioning and imaging, fitting these systems in a LINAC sized room requires not only thoughtful design, but also an efficient treatment workflow.

We are exploring many options to achieve high-quality but cost-effective treatments. Ultra-low field MRI is one interesting example. Initially focusing on breast treatments, we are investigating if this could be a good technology for image guidance. We optimized a breast coil for a specific ultra-low field scanner with a 6.5mT field. Volunteer studies in different positions will give us insights on anatomical deformations and allow to design treatment workflows with on board MRI imaging.

Treating patients with a fixed beam-line in different positions is challenging. Although historically proton therapy started with a fixed beam-line, since the gantry was introduced, all proton centers now use a full or half gantry. The challenges exist not only on the technical side, but it also requires soft skills to make different role groups change their notion about treating without a gantry. There is still a lot of research and development we need to do to demonstrate that treatments with a fixed beam-line can be comparable to the treatment with a gantry, if not better. At the beginning of my work in 2014, there was not much enthusiasm about the idea of removing the gantry. As time passed, there are more research groups and commercial companies working on finding solutions to reduce the cost and size of the proton system. I am thrilled to be part of this effort. My passion and belief are growing as well. I hope that an even larger group of scientists and engineers will work together on this exciting topic.

Despite the challenges, the benefit of democratizing proton therapy is substantial. The increase of accessibility of proton therapy to many more patients will provide more data for clinical trials. A less expensive compact system will also provide low and medium income countries (LMIC) accessibility to proton therapy, and expand proton therapy even more globally. One of the big societal impacts of democratization of proton therapy is the reduction of disability adjusted life year (DALY). In addition, democratization will promote new treatment strategies. Hypofractionation in proton therapy is increasingly being investigated. This could facilitate patients to have a more efficient treatment, especially in resources limited areas. Patients will travel less often and less far to the facility, and more patients can be treated. Photon-proton combination treatment is also an emerging area which could provide a better allocation of the proton treatment to those who benefit. New combinations with immunotherapy provide hope to cure more patients.

This is my journey so far. I look forward to embracing and overcoming all the exciting challenges the future brings, as well as to creating the future of a compact proton system!

4. Concluding remarks

Our personal perspective of proton therapy touches on some important developments only briefly, and completely ignores others. For example, FLASH therapy with its very high dose rates and short delivery times is emerging as one of the hottest research topics in the field of radiation oncology. It is covered in a separate article in this special issue. Whether or not FLASH keeps the promise of its biological advantage is unclear at this point. In a broader context, it has been said that the future of radiation oncology lies in biology, not so much in physics or technology. People have said this for many decades though, during which several disruptive innovations came from physics and technology, but hardly any clinically relevant biological breakthroughs. If research in FLASH can help to reduce the treatment delivery time, that will be a great improvement even without a biological benefit. We think that the temporo-spatial optimization of treatment delivery over different times scales from milliseconds to months, and the combination of proton/particle therapy with other treatment modalities including other radiation treatment modalities, is a promising research direction for the future. Our dream is that proton therapy with its improved physical selectivity will become part of the standard treatment arsenal for many if not most cancer patients. Overall, the most exciting part of the proton therapy journey may still be ahead of us.

Figure 1:

Theoretical limit of the dose shaping potential with photon and proton beams for a tumor target volume that wraps around a critical structure. Arc therapy and intensity modulation was assumed in both cases. Note that no range uncertainties were considered in the proton dose distribution. Source: Bortfeld, Habilitation thesis 1995.

Figure 3:

Schematic drawing (top left) and photo (top right) of the Lunder building at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where a proton therapy machine was retrofitted in levels LL2 and LL3 below the surface, under the ambulance entrance. Modified from Clasie et al. 2021 [4]. The treatment room is shown in the lower part of the figure (Massachusetts General Hospital photography).

References

- 1.Bortfeld T An analytical approximation of the Bragg curve for therapeutic proton beams. Med Phys. 1997;24(12):2024–2033. doi: 10.1118/1.598116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hueso-González F, Rabe M, Ruggieri TA, Bortfeld T, Verburg JM. A full-scale clinical prototype for proton range verification using prompt gamma-ray spectroscopy. Physics in Medicine & Biology. 2018;63(18):185019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unkelbach J, Bortfeld T, Martin BC, Soukup M. Reducing the sensitivity of IMPT treatment plans to setup errors and range uncertainties via probabilistic treatment planning. Med Phys. 2009;36(1):149–163. Doi: 10.1118/1.3021139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clasie BM, Bortfeld T, Kooy HM, Seybolt K, Sharp GC, Winey B. Retrofitting LINAC Vaults for Compact Proton Systems—Experiences Learned. IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences 2021;6(3):282–287. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan S, Depauw N, Adams J, et al. Technical note: Does the greater power of pencil beam scanning reduce the need for a proton gantry? A study of head-and-neck and brain tumors. Med Phys. 2022;49(2):813–824. doi: 10.1002/mp.15409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]