Abstract

In 1880, a German Jewish Professor of Pathology, Carl Weigert (1845–1904) first defined heart infarction as myocardial, coagulative necrosis (“Coagulationsnekrose”) due to obliteration of atherosclerotic coronary arteries thanks, at least, partially to his great diligence in vascular staining methods. Histochemical techniques made his name eponymic as Weigert’s Hematoxylin or Weigert’s and Van Gieson’s elastic stains are still used in routine practice to visualize, e.g., the framework of vessels. However, his discovery has been overshadowed by far more frequently cited in recent decades, subsequent but secondary, 214-page-long book dated on 1896 and titled “L’infarctus du myocarde et ses conséquences – ruptures, plaques fibreuses, anévrismes du coeur”, in which René Marie repeated Carl Weigert’s words that dead cardiomyocytes lost their cellular nuclei. Weigert introduced the term “die Infarcte des Herzmuskels”, in 1880, in his paper titled “Über die pathologischen Gerinnungsvorgänge”, in Virchows Archiv. According to Weigert, occlusions were caused by white thrombi (“weissen Thromben”) on the ground of atheromatous changes of the coronary arteries. In following manner, he gave macroscopic description of heart infarction: “If a blood supply is very roughly (German: brüsk), completely cut off in individual parts of the heart muscle, yellowish dry masses are formed that resemble coagulated fibrin”. “If examined microscopically, one usually does not find any fibrinous material exudate, but often a delusively normal tissue (sometimes you can even see cross striation of the muscle fibers): but all muscle fibers (…) are anucleate”. Paradoxically, coronary thrombosis was also a cause of Carl Weigert’s death.

Keywords: die Infarcte des Herzmuskels , anucleate cardiomyocytes , coronary thrombosis , Wrocław , Frankfurt am Main

Introduction

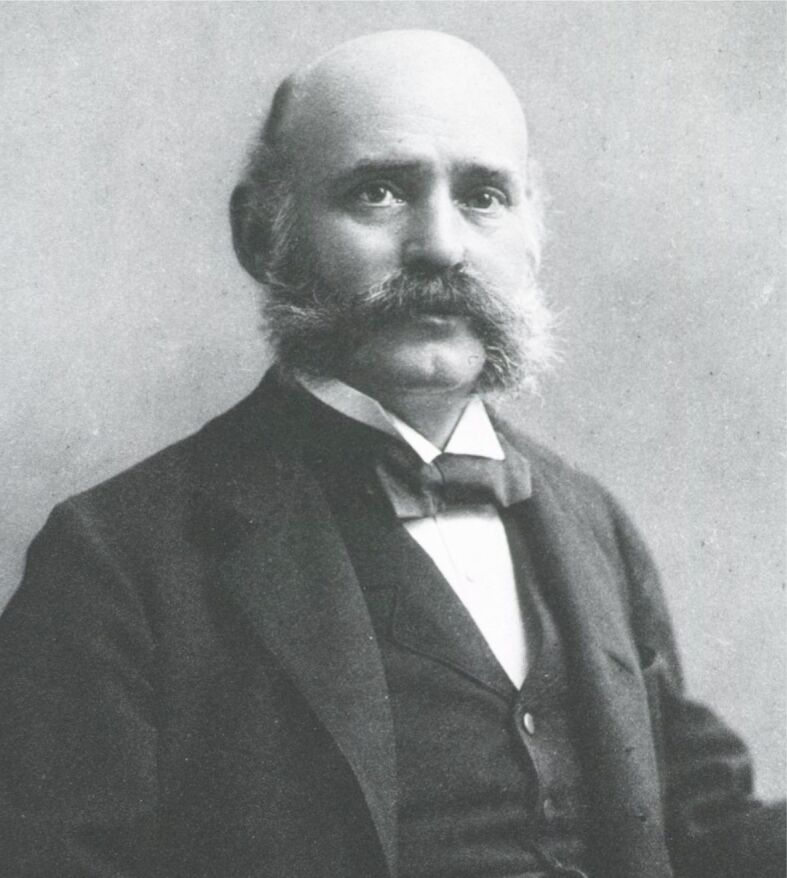

Who first described acute coronary syndrome, consistent with terms of currently, worldwide accepted definitions of the disorder? This question can be given at least a few answers with much of clinical controversy and reasonable debate. However, there should be the only one clear answer to the following question that refers to actually most frequent cause of deaths in history medicine: who first described and simultaneously gave an exact definition of heart infarction which is consistent with current diagnostic standards? In 1880, Carl Weigert (March 19, 1845–August 5, 1904) (Figure 1 ) first defined heart infarction as myocardial, coagulative necrosis due to obliteration of atherosclerotic coronary arteries [1, 2, 3]. His publication from Virchows Archiv is overshadowed by far more frequently cited in recent decades, subsequent but secondary, 214-page-long book dated on 1896/1897 and titled “L’infarctus du myocarde et ses conséquences – ruptures, plaques fibreuses, anévrismes du coeur”, in which René Marie repeated Carl Weigert’s words that dead cardiomyocytes lost their cellular nuclei, what is essential hallmark in a firm diagnosis of necrosis [3, 4]. However, to attract to his book more readership worldwide, René Marie provided fine drawings of microscopic appearance of the condition, which pathologist Carl Weigert missed to insert in his publication titled “Über die pathologischen Gerinnungsvorgänge”, in a mentioned Virchows Archiv [3, 4].

Figure 1.

Professor of Pathology Carl Weigert.

Materials and Methods

There are commemorative papers about Carl Weigert that were published shortly after his death [1, 2]. They could also be categorized as in situ resources, as their authors were lived in time of their cooperator Carl Weigert [1, 2]. Basic primary resources are his own publications. Secondary resources are papers which deal with Weigert’s discovery decades of years after his death. Thus, we decided to ground our paper on primary original resources.

Results

Weigert’s pioneer definition of myocardial infarction versus subsequent commentaries

First of all, Weigert introduced the term “die Infarcte des Herzmuskels”, in 1880, long before René Marie publishes his “L’infarctus du myocarde”, in 1896 [3, 4]. In his publication, Weigert described quite well understood at the time hemorrhagic infarct in the beginning to state: “Maybe even more typical are infarcts of different kind that are strangely not even mentioned: the infarcts of the heart muscle” [3]. Immediately afterwards, Weigert stated that thrombotic or embolic material formed on the ground of atheromatous changes of the coronary arteries and obstructed lumens of the vessels [3]. Thus, this was a revelation of cause of myocardial infarction first time in world literature! [3]. Carl Weigert was a German Jewish Professor of Pathology who worked under surveillance of Julius Cohnheim (1839–1884) in Breslau (Wrocław) and Leipzig Universities, who was deeply concerned with infarcts in result embolism of so-called end arteries [2]. In his lab, Weigert was diligent inventor of staining techniques of microscopic slides [2, 5]. Nowadays, so-called Weigert’s and Van Gieson’s stains are still widely used, precise, histochemical methods to visualize elastic laminas of arteries and in result to provide an accurate overview of histological architecture of vasculature [6]. René Marie mentioned Carl Weigert at least twice in his “L’infarctus du myocarde” from 1896 [4]. Namely, he admitted that Weigert revealed the basic significance of atherosclerosis of arterial heart vasculature in a progressive obliteration of the coronary branches [4]. However, the next sentence of his book Marie left without the proper quotation, making impression that it was his own discovery of French author in the topic of myocardial infarction: “While the sudden suppression of blood flow brings in the myocardium the production of a necrotic focus, its quantitative decrease causes the disappearance of muscle fibers and the formation of fibrous plaques” [4]. Such a statement was much better expressed but apparently secondarily based on Weigert observation published in 1880 [3]. Namely: “The obstructions of coronary arteries develop slowly or collateral pathways exist, so it results in (…) loss of muscle fibers without damage to the connective tissue” [3]. Here, Weigert emphasized incomparably greater vulnerability of cardiomyocytes to ischemic injury but nowadays we would rather say myocardium undergoes hypertrophy due to chronic ischemia, but Weigert referred to acute arterial occlusion when he wrote about loss of cardiac muscle. Next, Weigert provided macroscopic description of heart infarction: if a very rough, complete cutting off the blood supply takes place in individual parts of the heart muscle, yellowish dry masses are formed that resemble coagulated fibrin [3]. Here, René Marie’s “sudden” better characterizes the nature of complete occlusion of coronary arteries that the Weigert’ adjective “rough” (German: brüsk) [3, 4]. There is no doubt that Marie’s subsequent narration improves in detail the prior but basic Weigert’s description. René Marie could have been acquainted with publication by Ludvig Hektoen (July 2, 1863–July 5, 1951) who in 1892 reported severe myocardial infarction with a nonbacterial fibrinous pericarditis in result of complete occlusion of the sclerotic left coronary artery by red thrombus and this publication was popularized among American clinicians in 1912 by such titans of American cardiology as James Bryan Herrick (August 11, 1861–March 7, 1954) [7, 8]. Hektoen’s and Herrick’s papers are rightfully cited by fine reviews of the topic in US [9, 10]. However, some of them being clinically oriented on North American issues, did not mention about German, Jewish Pathologist Carl Weigert [9, 10]. Thus, we write straight ahead this paper to make it sound worldwide that Carl Weigert first described and defined heart infarction [3]. It does not mean that Weigert was not recognized at all in the field of studies on coronary heart disease. Yes, he was [1, 2, 5, 11, 12, 13]. One of the first medical historians who propagated Weigert as pioneer descriptor of myocardial infarction was Joshua Otto Leibowitz [April 25, 1895 (Vilnius, Lithuania)–July 10, 1993 (Jerusalem, Israel)] but as we reviewed literature on the topic of history of discovery of myocardial infarction and related coronary disease, we found Leibowitz did not reach his goal in changing still more popular point of view that René Marie coined the term of myocardial infarction with elucidation of its nature [5]. Leibowitz in his book in 1970 and Bruce Fye in 1985 even cited complete description of myocardial infarction, which was originally made in German by Weigert in 1880 [3, 5, 11]. Indeed, Weigert provided for the first time a microscopic picture of myocardial infarction [3, 5, 11]. However, Fye repeated Leibowitz’s translation of Weigert words also in this part: “almost no fibrous exudate, but often an apparently quite normal tissue (even the cross-striations of the muscle fibers often recognizable) but all muscle fibers and all the connective tissue are devoid of nuclei (originally in German: alle Muskelfasern, alles Bindegewebe ist kernlos)” [3, 5, 11]. At this point, we should be aware that in XIXth century the histological nomenclature was just being evolving for exact types of tissues. In translation of “Bindegewebe”, we would add to adjective “connective” also “linking” as the first righteously means exact type of human tissue, while the second one characterizes the organizational aspect of tissue that links and supports the architectural composition of myocardium in the framework of cardiac syncytium. Thus, in this matter, one should be careful not to get into linguistic trap: cardiac muscle fibers do not belong to fibrous connective tissue, while fibrinous and fibrin are totally different from fibrous – medical historian without higher medical education can easily get lost within differences of these terms. On the other hand, Weigert used “Bindegewebe” in the meaning of the connective tissue in other place of the manuscript, when he described gradual loss of cardiac muscle fibers and no damage to primary, normal connective tissue, that could overgrow in conditions of chronic ischemia and hypoxia or can give rise to fibrous scar after acute myocardial infarction. As the precise words are crucial in pathological report, we compare previous Leibowitz’s & Fye’s translation with ours in which Weigert’s narration is presented in more accurate manner: “if examined microscopically, one usually does not find any fibrinous material exudate, but often an apparently normal tissue (sometimes you can even see cross striation of the muscle fibers): but all muscle fibers, all “linking”, connective tissue is anucleate” [3]. We compare these translations because ours “fibrinous” versus Fye’s “fibrous” matters in precise medical report. Next, there is Weigert’s remark of reactive inflammatory infiltrate in vicinity of cardiac infarction, which Fye also quotes translates with great scrutiny [11]. Most importantly, loss of nuclei in cardiomyocytes has been a hallmark of myocardial necrosis and the most important feature of histopathological diagnosis of myocardial infarction and that is why its clinical diagnosis has been requiring presence of markers of myocardial necrosis [9, 11]. Macroscopically yellowish mass was denied by Weigert to be an organized fibrinous exudate, but he concluded that such areas resemble splenic and renal necroses/infarcts [3]. Thus, in his paper, Weigert put cardiac infarcts in the same group with splenic and renal infarcts, which according to current terminology are ischemic infarcts with microscopic picture of coagulative necrosis – a term currently worldwide used [3]. So as Weigert stated there was no intracardiac fibrinous mass but macroscopically fibrinous-like area of microscopically proved cellular necrosis and from word fibrinous-like has very much in common with coagulative in minds of medical practitioners worldwide [3]. Indeed, his whole publication of the year 1880 was regarded as monograph on coagulation necrosis in his short obituary in the year of his death 1904 [1]. Consequently, according to one of basic biographical reports about Weigert by Hyman Morrison, in 1924, Weigert considered the myocardial infarction, foci of sclerosis of central nervous system and tuberculous caseation as forms of coagulation necrosis [13]. Paradoxically, even the cause of his death was coronary thrombosis [13]. Thus, we decided to write a few cordial words about Weigert as his most important discoveries in the field of myocardial infarction have been overshadowed. On the contrary, other fields of Weigert exploration are soundly recognized and honored with magnitude of obituaries in the most important world medical journals and subsequent reviews that repeated about his staining methods and studies of nervous system [6, 13. 14, 15, 16].

Final remarks

Migrations of Breslauer medical scientists due to discrimination

In aspect of overshadowing of Weigert pioneer definition of myocardial infarction, his example is completely opposite to Leopold Auerbach whose greatest discovery of plexus myentericus was eponymously famous and world-recognized on contrary to the rest of Auerbach heritage until latest English written biographical papers that dealt with complete scientific impact and his biographical details [17, 18, 19, 20]. Actually, both Weigert and Auerbach were born in Lower Silesia: Weigert on March 19, 1845, in Münsterberg (Polish: Ziębice at present) while Auerbach on April 27, 1828, in Wrocław (Breslau at the time) [1, 2, 20]. Commemorative papers about Auxiliary Professor of Breslau University Leopold Auerbach were written exclusively in German by his close Breslauer friends Professor of Microbiology Ferdinand Julius Cohn (January 24, 1828–June 25, 1898) and Professor of Anatomy Gustav Born (1851–1900) in local journals and they had rather limited readership [17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]. Weigert died in 1904 as widely recognized Director of the whole The Senckenberg Institute of Pathology in Frankfurt am Main, which emerged to dimensions of huge banking city in the middle of Europe and his obituary was placed in British Medical Journal (an English written Journal of worldwide impact) [1]. Shortly afterwards, in 1906, 146-pages-long biographical book was published in German about Weigert by Professor of Surgery Robert Rieder (December 28, 1861–August 24, 1913) and still The Senckenberg Institute of Pathology cherishes memory of his great chief [2]. It might seem that Weigert had much more luck for excellent English-written biographies than Auerbach [1, 2]. However, Auerbach’s plexus is worldwide famous eponym while the term Weigert’s infarction has never been in use [9, 20]. Carl Weigert studied medicine in Berlin, Vienna, and Breslau. He worked in Breslau from 1871 to 1878 being Clinical Assistant of Hermann Lebert from 1871 to and 1874 and since 1874 he assisted Julius Friedrich Cohnheim (1839–1884) in Institute of Pathology of Breslau University having there his habilitation in 1875. From 1878, he translocated with Cohnheim to Leipzig, where Weigert received the same rank of Auxiliary Professor of Pathology (außerordentlichen Professor) in 1879 as Auerbach in Breslau [2, 20]. After Cohnheim death in 1884, Weigert did not succeed the Chair of Pathology and he was refused the position of Ordinary Professor in Leipzig because of his Jewish origin [2, 13]. Peculiarly enough, to prevent such a sort of discrimination, being also a Jew, Cohnheim converted to Christian faith to be granted professorship in Kiel (1868–1872) [2]. Thus, Weigert left Leipzig and moved to Frankfurt am Main where he was nominated an Ordinary Professor and Director of The Senckenberg Institute of Pathology (Pathologisch-Anatomischen Instituts der Senckenbergischen Stiftung) without necessity of conversion to Christianity [1, 2, 5, 6, 13]. Thus, from the point of academic career, Frankfurt am Main seemed to be more appropriate place for Jews than Wrocław (Breslau) for a number of reasons, mainly thanks to protective financial strength of highly esteemed family of bankers, the Rothschilds’, that was unrivalled by other, even quite prominent members of Jewish communities in cities like Breslau [2, 5, 20, 23, 24]. The problem of anti-Semitic discrimination was apparent in lives of both Weigert and Auerbach and was mainly expressed by the rule that scientist of Jewish faith was usually prevented from promotion to higher ranks of university career above the position of Associate Professor [2, 20, 24]. In our studies of Leopold Auerbach biography, we came across a publication titled “Nervenendigung in den Centralorganen”, dated on 1898, so a year after death of Leopold Auerbach (1828–1897) [20, 25]. To our surprise, in the title page of that paper it was undersigned “Von Dr. med. Leopold Auerbach, Nervenarzt zu Frankfurt a./M”, so we assumed that it was a publication (with postmortal date of the issue of the Journal) of the discoverer of plexus myentericus in spite of the fact that not only one man bore the name Leopold Auerbach [for example, a jurist Leopold Auerbach (1847 born in Breslau, died in 1925 in Berlin)], but we assumed that there was only one Leopold Auerbach, who was “Nervenarzt” in the end of XIXth century [20, 25]. We highlight this in current paper, because we suppose with great probability that Leopold Auerbach might have been invited to join Carl Weigert’s team in Frankfurt am Main, but he finally did not manage to move to Frankfurt due to his sudden death in summer 1897 [20]. Leopold was getting more and more isolated in envious society of Breslau, particularly after death of his wife, Arabella Auerbach (1837–1896), who being a very sociable person made Leopold more active in numerous initiatives in Wrocław [20]. This would be explanation for placing Frankfurt am Main as geographical affiliation of Leopold Auerbach in the publication of the year 1898 [25]. Auerbach felt deeply collapsed after death of Arabella, while still remaining in the position of Auxiliary Professor since 1872, in Breslau, so little could stop him from leaving the city of his birthplace [20]. In Breslau, there was much more grimmer atmosphere due to significant impact of local anti-Semitic literature, such as popular “Unser Verkehr” authored by Breslauer playwright and anti-Semitic, medical doctor Karl Borromäus Alexander Sessa (1786–1813), and anti-Jewish and anti-Polish roman “Soll und Haben” by Gustav Freytag (1816–1895) [17, 20]. Frankfurt was different in the end of XIXth century. For sure, more tolerance was induced in part thanks to Libertarian, Frankfurter Zeitung of high-circulation that was issued by a popular Jewish deputy to the Reichstag (1871–1877 and 1878–1884), local government official, philanthropist, and banker Leopold Sonnemann [26]. The atmosphere of Frankfurt really favored Jewish emancipation to much greater extent than in Breslau (Wrocław) [27, 28]. The Jewish community in Frankfurt was subject to rapid processes of emancipation and assimilation in the XIXth century with flourishing of Reformed Judaism and establishment of the first Jewish elementary school 1804 [2]. From 1796 (when French troops destroyed part of Judengasse), Jews were allowed to settle outside the ghetto. On a will of Napoleon I, a rule over Frankfurt was granted to a Duke of Prince-Archbishop of Regensburg Karl Theodor Anton Maria von Dalberg (1744–1817) in 1806 who, in the same year, was addressed a memorandum in which Jews highlighted the magnitude of their economical support of Frankfurt City and postulated full civil equality of that minority [23, 24]. It seems that economical interest mainly drove emancipation of Jews in Frankfurt [23]. After a short period of restitution of the ghetto, in 1807–1811, Jews purchased the right to live outside the ghetto area in 1811 for 400 000 golden guldens (the equivalent of much over 28 million USD as inflation rate speeds up) on official plea of lost tax revenues from Jews. Thanks to highly esteemed family of bankers, the Rothschilds, particularly Amschel Mayer Rothschild, such an amount was paid to Dalberg who being Grand Duke of Frankfurt granted the Jews full civil rights in result [23]. In 1815, the Free City of Frankfurt was restored with reduction of Jewish rights to the pre-revolutionary level (without the return of the 400 000 golden guldens previously paid, of course) and the Hep-Hep riots occurred, but as early as in 1824 private, civilian equality was introduced, and in 1854 full equality was re-established for all the citizens of the city [23, 27, 28]. This equalization took place in Frankfurt as the second German state after the Grand Duchy of Baden [27]. Then, the Free City of Frankfurt was incorporated into the Kingdom of Prussia in 1866 and official attitude of administration tended to be similar in Breslau and in Frankfurt [2, 23]. However, Jewish life had much more comfort to flourish in Frankfurt than in Breslau due to affluent bankers’ family of Rothschilds who maintained a kind of protective umbrella over Jewish community in Frankfurt due to their extraordinary financial power [23, 27, 28].

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

Piotr Woltanowski is indebted to his Father, Professor of History at Warsaw University, Andrzej Woltanowski (1942–1996), a close Tutor that grounded his reports on primary original archives, for all lessons of meticulousness and academic honesty.

References

- 1.Obituary: Karl, M undefined. D., Director of the Senkenberg Institute, Frankfort. Br Med J. 1904;2(2278):475–475. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rieder R . Carl Weigert und seine Bedeutung für die medizinische Wissenschaft unserer Zeit; eine biographische Skizze . Berlin : Springer Verlag ; 1906 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weigert C. ber die pathologischen Gerinnungsvorgänge. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Physiol Klin Med. 1880;79(1):87–123. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marie R . Thése de Paris . 88 . Paris : Georges Carré et C. Naud ; 1896 . L’infarctus du myocarde et ses conséquences – ruptures, plaques fibreuses, anévrismes du coeu ; pp. 1 – 214 . [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leibowitz JO . Publications of The Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine . 28 . Berkeley–Los Angeles, USA : University of California Press ; 1970 . The history of coronary heart disease ; pp. 9 – 175 . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wohlrab F, Henoch U. The life and work of Carl Weigert (1845–1904) in Leipzig 1878–1885] Zentralbl Allg Pathol. 1988;134(8):743–751–743–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hektoen L. Embolism of the left coronary artery; sudden death. The Medical News (A Weekly Journal of Medical Science) 1892 Aug;61(8):210–212. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrick JB. Clinical features of sudden obstruction of the coronary arteries. JAMA. 1912;59(23):2015–2022–2015–2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(1):54–63–54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1112570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dock W. Myocardial infarction becomes emeritus. Circulation. 1962;26(4):481–483–481–483. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.26.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fye WB. The delayed diagnosis of myocardial infarction: it took half a century. Circulation. 1985;72(2):262–271–262–271. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benson RL. The present status of coronary arterial disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1926;2:870–916–870–916. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrison H. Carl Weigert. Ann Med Hist. 1924;6(2):163–177–163–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohnheim JF . Lectures on general pathology: a handbook for practitioners and students . 2 . London : The New Sydenham Society ; 1889 . [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carl Weigert (1845–1904) JAMA. 1964;189(10):769–770. doi: 10.1001/jama.1964.03070100063018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sammet K. Carl Weigert (1845–1904) J Neurol. 2008;255(9):1439–1440–1439–1440. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0917-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wincewicz A, Woltanowski P. Leopold Auerbach’s heritage in the field of morphology and embryology with special emphasis on gametogenesis of invertebrates. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2020;61(2):587–593–587–593. doi: 10.47162/RJME.61.2.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wincewicz A, Woltanowski P. Leopold Auerbach. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(9):723–723. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wincewicz A, Woltanowski P. Leopold Auerbach’s achievements in the field of vascular system. Angiogenesis. 2020;23(4):577–579–577–579. doi: 10.1007/s10456-020-09739-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wincewicz A, Woltanowski P. Heritage of Leopold Auerbach in the field of morphology of nervous system. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2021;62(1):325–330–325–330. doi: 10.47162/RJME.62.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cohn F . Annals of Silesian Society for Native Culture . Breslau : G. P. Aderholz’ Buchhandlung ; 1898 . Leopold Auerbach – Nekrologe ; pp. 3 – 9 . [Google Scholar]

- 22. Born G . Leopold Auerbach . Jena : Anat Anz ; 1898 . pp. 257 – 267 . [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holtfrerich CL . Frankfurt as a financial centre: from medieval trade fair to European banking centre . München, : Verlag C. H. Beck ; 1999 . pp. 367 – 367 . [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gräfe TH . Judentum und Antisemitismus in Frankfurt am Main und Breslau 1866–1914 . München, : GRIN Verlag ; 2004 . pp. 1 – 6 . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auerbach L. Nervenendigung in den Centralorganen. Neurol Centralbl. 1898;17(10):445–454–445–454. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lordick H. Leopold Sonnemann. Streitbarer Politiker und Gründer der Frankfurter Zeitung. Kalonymos. 2009;12(3):1–6–1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Graetz Graetz H . History of the Jews (1923 historical reproduction, one volume abridged edition edited by Randolph Parrish). Resource Publications, 2002; Graetz H. Volkstümliche Geschichte der Juden [Popular History of the Jews]. Band I–III, Verlag von Oskar Leiner, Leipzig, 1888; Graetz H. Geschichte der Juden von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart. Band I–XI . Leipzig : Verlag von Oskar Leiner ; 1900 . pp. 11853 – 11875 . Available from: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb10570421?page=8. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Battenberg JF . Das europäische Zeitalter der Juden: zur Entwicklung einer Minderheit in der nichtjüdischen Umwelt Europas . Darmstadt : Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft (WBG) ; 1990 . pp. 306 – 361 . [Google Scholar]