Abstract

Introduction:

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a global problem that often begins with prescribed medications. The available treatment and maintenance plans offer solutions for the consumption rate by individuals leaving the outstanding problem of relapse, which is a major factor hindering the long-term efficacy of treatments.

Areas covered:

Understanding the neurobiology of addiction and relapse would help identifying the core causes of relapse and distinguish vulnerable from resilient individuals which would lead to more targeted and effective treatment and provide diagnostics to screen individuals who have a propensity to OUD. In this review, we cover the neurobiology of the reward system highlighting the role of multiple brain regions and opioid receptors in the development of the disorder. We also review the current knowledge of the epigenetics of addiction and the available screening tools for aberrant use of opioids.

Expert opinion:

Relapse remains an anticipated limitation in the way of recovery even after long period of abstinence. This highlights the need for diagnostic tools that identify vulnerable patients and prevent the cycle of addiction. Finally, we discuss the limitations of the available screening tools and propose possible solutions for the discovery of addiction diagnostics.

Keywords: Opioid, Reward, Epigenetics, Brain, Circuitry, Addiction

1. Substance Use Disorder and The Opioid Crisis

Substance use disorder is an illness characterised by chronic uncontrolled compulsive seeking and consumption of a substance (in this case drugs), which is accompanied by negative emotional state when drugs are unavailable leading to relapse [1]. Abused drugs disrupt key cognitive systems and deploy them to maintain dependence. Molecular and physiological alterations of the brain reward, memory, motivation, and decision-making systems result in tolerance and withdrawal which characterise dependence. These molecular changes are behaviourally manifested in craving, stress, and depression, all of which are elements that characterise addiction [2]. While the terms “dependence” and “addiction” are usually used interchangeably, dependence and addiction are used to describe the molecular and the behavioural aspects of substance use disorder, respectively.

Drugs of abuse are classified according to their mode of action and target receptors. Psychostimulants, cannabis, alcohol, nicotine, and opioids are all substances that modulate the reward system and develop dependence through different mechanisms. In this review paper, we focus on opioids and their target receptors.

Opioids are derived from opium which is extracted from poppy seeds. It has been medically and recreationally used throughout history. In 1805, morphine, the active component, was isolated from opium and was identified as a potent painkiller. Shortly after, synthetic derivatives of morphine became medicinally available for pain management[3]. From the 1970s to the early 1990s, the discovery of opioid receptors and endogenous opioid polypeptides enhanced our knowledge and opened the door for molecular and genetic approaches to provide a better understanding of the opioid system[3].

Despite the availability of treatments for addiction, relapse is still a major challenge with an estimate of at least 40% of treated individuals relapsing within 6 months of treatment [4]. In North America, overprescribing of opioids for pain management has led to an opioid epidemic rising from the non-pharmaceutical use of prescribed opioids and the transition to the illegal use of heroin. In the United States, the number of drug-related overdose deaths rocketed to 72,000 annual deaths the majority of which are opioid-related [5]. The estimated number of high-risk opioid users in the EU reached to 1.3 million in 2017. Prescribed opioids have led to long-term addiction in 14.6% of first timers in the UK [6]. In their last published report in January 2022, the Northern Ireland Assembly described the addiction services available in Northern Ireland. According to their report and another report published in June 2020 by the Northern Ireland Audit Office, the prescription rate of drugs that are potentially addictive is higher in Northern Ireland than the rest of the UK with Tramadol and oxycodone listed amongst these drugs of concern [7]. Most of the drug-related deaths are caused by prescription drugs with an overall increase of >40% compared to the figures in 2013. Tramadol misuse-related deaths alone has increased by 14% in 2018 [7]. In addition to the significant mortality there is a high economic burden linked with addiction.

In order to approach the problem of addiction and understand how dependence is mediated, it is essential to understand the different phases of addiction and the implicated neurocircuitry, and how aberrant processing of reward, learning and memory and motivation facilitate addictive behaviour. Addiction is developed through three stages. The habit of drug consumption is formed through the cycle of intoxication, withdrawal, and anticipation [1]. Although it might appear as a simplistic description of the vicious cycle of addiction, this cycle attracts multiple psychological, behavioural, and neuroscientific theories of addiction. Nevertheless, despite the viewpoint from which we try to understand addiction, understanding the reward system and some of the implicated neurocircuitry is a focal starting point [2,8].

2. The Reward System

The term “reward” is defined as an event that increases the chance of the recurrence of a response toward a positive hedonic element [1]. Reward is mainly driven by the dopaminergic mesolimbic system which project from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to key cognitive regions in the brain amongst them the prefrontal cortex (PFC), the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and the hippocampus. Normal daily events that activate the reward system are as simple as food consumption, sexual and social activities. In the case of drug addiction, however, activation of dopaminergic VTA neurons results in an exaggerated increase of dopamine in the striatum and especially in the NAc, which is in the ventral striatum [2,4]. As the current understanding of the reward specific circuitry is broadened, it is well accepted that activation of certain systems does not solely rely on the activation of one class of receptors through the release of specific neurotransmitter. It is rather the convergence of multiple inputs and outputs that lead to the activation and neuromodulation of the reward system [1]. Such neurotransmitters include, but not limited to, dopamine [9], glutamate [10], γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [11], serotonin [12] and acetylcholine [1,4]. On this note, opioids indirectly activate the reward system via disinhibition of dopaminergic neurons through the inhibition of GABAergic interneurons [13]. Unlike opioids, psychostimulants exert their action directly by blocking presynaptic dopamine transporter (DAT) or by increasing the synaptic vesicle release rate [4].

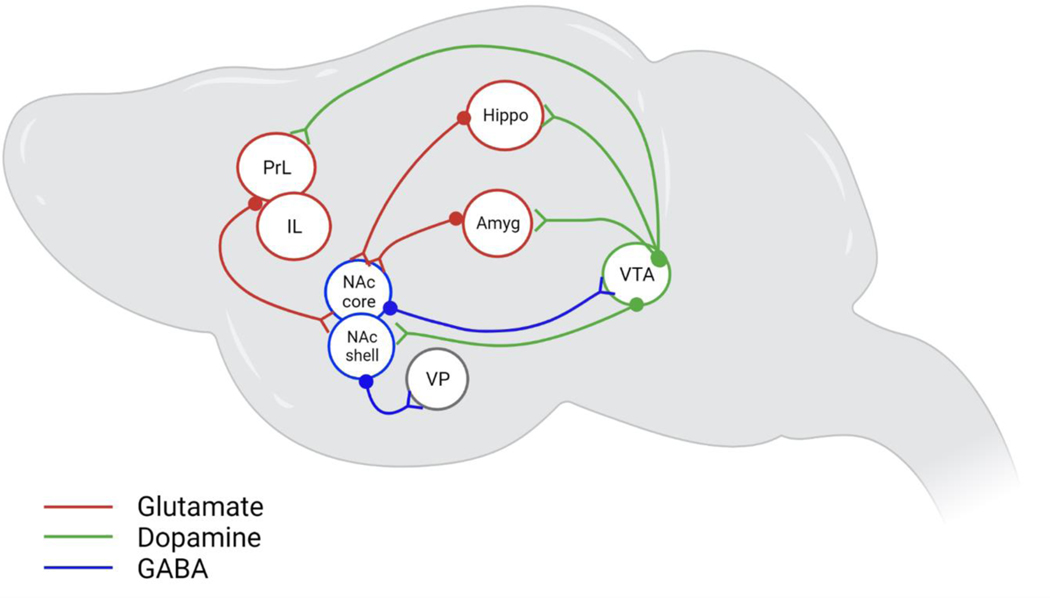

Activation of the reward sensation, or the feeling of being high, requires activation of the low-affinity dopamine receptors (D1). This can be achieved by a steep release of dopamine and opioid peptides in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the nucleus accumbens (NAc) through binge intake of drugs or intoxication stage. During this process, multiple brain regions, implicated in inhibitory control, decision making, stress and motivation, and learning and memory, are recruited to ensure habit formation and to maintain motivation for drug seeking and compulsive intake [1,2,8]. Figure 1 summarises some of these overlapping processes following the activation of multiple brain regions.

Figure.1: Neurocircuitry of addiction.

Dopaminergic signalling is an important element in motivation and goal seeking behaviour which plays a critical role in addiction. Establishment of the rewarding effect starts with disinhibition of dopaminergic neurons in the VTA which results in a steep release of dopamine in the NAc. The motivation and learning systems facilitate dependence by pairing the rewarding experience with contextual and drug-associated cues. Maintenance of the addictive behaviour involves glutamatergic inputs from PrL and the BLA to the NAc core alongside projections from the IL and ventral hippocampus to the NAc shell to mediate drug seeking. The motivation to obtain reward is further signalled by inhibitory GABA projections from the NAc shell to the VP. Anticipation and craving are mediated via dopaminergic projections from the VTA to the PFC, NAc, amygdala and the hippocampus all of which are context- and cue-induced. Abstinence results in a hypodopaminergic state associated with reduced uptake of dopamine [9] [49] in the NAc which mediates withdrawal.

2.1. The prefrontal cortex

It is widely acknowledged that the prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays a prominent role in cognition, including decision making, inhibitory control, valuation, and motivation [8]. Administration of opioids has been reported to disinhibit glutamatergic input from the PFC to the VTA and NAc and increase dopamine level in those areas whereby acute reward is signalled [14]. Projections from the PFC has been found to be implicated in the striatal-pallidalthalamocortical loop, which engages the dorsal striatum and results in habit formation and compulsive drug seeking [1]. Furthermore, neuroimaging studies have demonstrated consistent involvement of different subregions of the PFC in addiction [15].

The prelimbic cortex (PrL) of the PFC plays a primary role in the compulsive drug seeking behaviour, which is manifested by the persistence of drug seeking even with the anticipation of aversive consequences [16]. On the other hand, the infralimbic cortex (IL) is known to play a crucial role in the acquisition and the expression of habitual behaviour and extinction learning [17]. Projections from the PFC to the NAc and the resulting behavioural outcome can be defined by the involved subregions. Projections to the NAc core originate from the prelimbic cortex (PrL) and are responsible for maintaining drug-cues association [18], whereas the NAc shell receives projections from the infralimbic cortex (IL) [19] and this is responsible for the drug-context association [20]. Moreover, the PrL-NAc core and the IL-NAc shell have been found to drive the relapse process of addiction [14].

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is a critical region for decision-making and outcomes evaluation where it has been shown to be key for valuation and devaluation of rewards and integration of newly learned information for making more flexible and precise decisions [21]. The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) of the PFC is the subregion implicated in motivation and willed action control through encoding the value of reward expectancy. This cognitive property of the ACC is one of the influential factors that drive persistence in reward attainment despite delays [22].

2.2. The ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens

The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is one of the central brain regions of reward circuitry in general. The area is heterogeneously populated with neurons amongst which are dopaminergic (DA) and GABAergic interneurons constituting the majority and second majority, respectively [19]. Dopaminergic projections originate from the VTA to innervate key mesolimbic and mesocortical structures such as the nucleus accumbens (NAc), the PFC, the amygdala, and the hippocampus [14]. The VTA receives more GABAergic input from the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg), which lies at the tail of rodents’ VTA. These projections have been found to mediate the reinforcing effect of opioid by modulating GABAergic inhibition [23]. It also receives glutamatergic inputs from several brain regions rendering it a pivotal structure in processing reward-related information. Despite their different mechanisms of action, all drugs of abuse result in an elevated dopamine levels in the NAc and the subsequently featured addictive behaviour [14,15,19].

Unlike the VTA, the predominant neuronal population in the NAc is GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSN). These are commonly subdivided into D1 and D2 (dopamine receptors 1 and 2) expressing neurons. The NAc is comprised of two constituents, the nucleus accumbens shell and core based on their role in reward-related response. The nucleus accumbens core is responsible for the acquisition of the reward-cue association while the shell is primarily involved in the prediction of reward and processing of affective behaviour [24]. In terms of information input, the NAc receives dopaminergic input from the VTA and receives glutamatergic inputs from variety of limbic and cortical brain regions notably, the PFC, the basolateral amygdala (BLA) and the hippocampus [14,15]. In return, the NAc D1 MSNs has been reported to project primarily to the VTA and to other midbrain structures, whereas D2 MSNs project to the ventral pallidum. The received input and the projected outputs applies to both constituents of the NAc which explains some of the overlapping behavioural outcomes [24].

2.3. The amygdala and the hippocampus

The amygdala is part of the medial temporal lobe that was considered, initially, to play restricted role of aversive learning and fear conditioning. However, recent research has unveiled the crucial contribution of the amygdala in appetitive learning and its role in mediating goal-directed and adaptive behaviour [10,19]. The basolateral amygdala (BLA) receives glutamatergic projections from the thalamic and cortical regions which are reciprocated. It also unidirectionally projects to the central nucleus (CeN), NAc and the dorsomedial striatum. Dopaminergic and serotonergic innervations to the amygdala comes from the VTA and the dorsal raphe, respectively [10,25].

Studies of the appetitive conditioning role of the amygdala suggest that the basolateral amygdala (BLA) and the central nucleus (CeN) distinctively mediate emotional processing [15,19]. With respect to addiction, a considerable number of studies show that the control of goal-directed reward seeking relies on the glutamatergic BLA-NAc circuit. The BLA directly projects to the NAc shell to gate opioid reward and indirectly activates the NAc core, through the BLA-PrL, to mediate drug relapse [25]. On the other hand, CeN has been shown to be key for the acquisition and expression of both conditioned place preference and aversion to morphine and naloxone self-administration, respectively [26]. Glutamatergic projections from the CeN are generally responsible for withdrawal and aversion, particularly the CeN-PAG (Periaqueductal grey) innervations, a region that is known for the expression of physical withdrawal symptoms [10].

The hippocampus is the key structure for the processing and consolidation of long-term declarative memory [27]. It binds sensory inputs of spatial and contextual information to form a complex representation necessary for the formation of memories and autobiography [28]. The hippocampus sends glutamatergic projections to the NAc while receiving inputs from the BLA and PFC rendering it pivotal for integrating spatial/contextual and emotional information and subsequently maintaining an associative memory of events relevant to drug intake [10,19,28].

2.4. The habenula, ventral pallidum and raphe nucleus

The habenular complex is part of the diencephalic conduction system and is composed of two main domains, the lateral and the median habenula (LHb and MHb). Most projections to the MHb originate from the septum while the MHb exclusively projects to the interpeduncular nucleus (IPN) [29]. On the other hand, the lateral habenula (LHb) is heavily innervated by brain structures of the limbic system and basal ganglia projecting to the medial and lateral subdivisions of the LHb, respectively. In turn, the LHb projects to key structures of the brainstem. These include dopaminergic VTA and SNc, serotonergic raphe nucleus as well as the GABAergic RMTg. The circuitry in the LHb renders this structure a convergent point of funnelled information from major brain systems and a strategic node to relay the processed inputs from the cortex to the brainstem [30].

The habenular complex is involved in controlling emotional behaviour, such as fear and anxiety as well as mediation of positive motivational state. It is known to be the hub that regulates the intensity of pleasure-seeking behaviour as well as modulation of aversion [31–33]. Transgenic ablation of the mouse MHb resulted in maladaptation to novelty and heightened impulsive and compulsive behaviour [30]. More specifically, genetic ablation of the dorsal MHb (dMHb) of mice resulted in a decreased motivation towards wheel running activities and to sucrose-sweetened drinking water [32]. In contrast, increased neural and metabolic activities in the LHb is as sociated with depression in human subjects and depression-like behaviour in animal models [34]. Overall, the habenular complex has been reported to be a key structure for processing of acute and chronic stress and the related transitioning from active to passive coping [33–35].

In an addiction-related context, MHb was found to play a major role in drug seeking where deletion of mice nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the MHb resulted in an increased self-administration of nicotine [36]. This study shows that this part of the habenular complex is heavily implicated in the regulation of drug intake, particularly that associated with nicotine avoidance behaviour [29,30,36]. With respect to the opioid system, the MHb is one of the brain’s richest regions with μ-opioid receptors (MOR). They are found to be expressed mainly on substance P (SP) and subpopulations of cholinergic (Ach) neurons [37]. Conditioned knockout of OPRM1 gene in nicotinic β−4 cholinergic neurons in the MHb resulted in a reduced analgesic effect of morphine upon the first dose. However, analgesia and tolerance to morphine were restored upon the second administration of the drug [38]. In the same study, mutated mice displayed reduced conditioned place aversion (CPA) to naloxone which suggests that MORs in this region are recruited to control withdrawal-related aversion [38].

Ventral to the anterior commissure lies the ventral pallidum (VP), one of the key regions involved in motivation directed behaviours. The VP is a heterogeneous structure with GABAergic neuros constitute most cellular population [39]. It is subdivided into two main components according to the neuroanatomical and functional characteristics. Anatomically, the VP is divided to ventromedial (vm) and dorsolateral (dl) VP. The ventromedial VP (VPvm) is neurotensin positive whereas VPdl is calbindin-d28k positive and both subregions express substance P and enkephalin [39]. On the other hand, the VP is functionally subdivided into an anterior and posterior parts which show opposite hedonic responses [40] and different involvement in drug seeking behaviour [41].

At a cellular level, most of the cell population in the VP are GABAergic with a small population of glutamatergic and cholinergic neurons. The VP also contains parvalbumin neurons which were found to release both glutamate and GABA [42]. VP GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons project to different neurons within the VP as well as to other reward-related brain structures including the VTA, BLA, PFC and LHb [43]. However, activation of glutamatergic neurons was found to oppose the outcomes of the activation of GABAergic cells whereby GABAergic stimulations were associated with increased neuronal activity in the VTA, which was translated into a preference of an appetitive reinforcement. Glutamatergic stimulation produced aversion after the observed neuronal activation detected in the LHb [43]. The VP receives GABAergic innervations from the NAc while glutamatergic inputs to the VP come from the PFC and the amygdala, and dopaminergic projections from the VTA [44,45].

The dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) is the part of the hindbrain where almost half of the serotonergic innervations are derived. It is composed of different types of neurons with serotonergic neurons constituting the majority [46,47]. Alongside serotonergic neurons, the DRN is populated with dopaminergic, glutamatergic, GABAergic and substance P neurons as well as non-neuronal cells. The DRN is reciprocally connected to variety of functionally distinct cortical and subcortical structures and is heavily involved in learning and memory, decision-making, reward, and affection [46,48].

From the VTA, the DRN receives mainly GABAergic stimulations which have different reward-related behavioural outcomes. A study by Y. Li., et al showed that rostral VTA (rVTA) projections led to disinhibition of DRN serotonergic neurons by inhibiting local GABAergic neurons, whereas caudal VTA (cVTA) inputs directly inhibited serotonergic neurons. The study used Gad2-IRES-Cre mice expressing channelrhodopsin 2 (ChR2) or N. pharaonis halorhodopsin (NpHR) in the rostral and caudal VTA GABAergic neurons. To allow light-mediate inhibition or activation of the r-cVTA inputs to the DRN, they implanted optical fibres above the DRN. Photoactivation of rVTA – DRN signalling pathway produced place aversion while photoactivation of the cVTA – DRN pathway produced real time place preference in mice. Activation of VTA MOR depressed the rVTA – DRN signalling pathway and subsequently blocked place aversion in mice [48].

Apparently, the role of the DRN in addiction is not limited to expression of preference or aversion towards the rewarding event. More studies suggest that the DRN serotonergic system is involved in certain aspects of impulsive behaviour, which can predict vulnerability to substance use disorders [46].

Identifying the circuit by which addictive behaviour is mediated is a crucial step towards understanding the complexity of the disorder. However, more studies in the context of opioid addiction are important to highlight the individual characteristics of how opioids modulate the circuitry between the multiple regions of the brain.

3. Opioid Receptors

Opioid receptors are broadly expressed in the central (CNS) and to a lesser extent in the peripheral (PNS) nervous system. In the CNS, they are primarily expressed in the cortex, the limbic system, and the brain stem, whereas they have been found to be expressed peripherally in the gastrointestinal tract, heart, and immune system among other locations [50]. While opioid receptors can be activated by varieties of exogenous compounds as well as endogenous polypeptides, the resultant effects are manifested differently according to the location of the activated receptor. Activation of CNS opioid receptors is accompanied by peripheral adverse effects such as constipation and respiratory depression. However, the regulation of opioid receptors covered in this review is focused mainly on the CNS.

The transmembrane opioid receptors belong to the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. They include 4 types; μ- (MOR) encoded by the Oprm1 gene, δ- (DOR) encoded by the Oprd1 gene, К- (KOR) encoded by Oprk1 gene and the non-opioid orphanin FQ/nociception receptor encoded by Oprl1 gene [51].

Opioid receptors are stimulated by endogenous opioid polypeptides, under normal conditions, to regulate pain and modulate the reward system [3,51]. These are the β-endorphin, enkephalins and dynorphins which respectively activates, with preferential affinities, the μ-, δ- and К- opioid receptors.

3.1. μ-opioid receptors (MORs)

Amongst the opioid receptor family, MORs are central to the achievement of the therapeutic effect of drugs (i.e., analgesia) as MORs are the main target for opiate class of pain management drugs such as morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl [3,52] as well as the development of the adverse effects (dependence and hyperalgesia). Moreover, the functions of MORs in the CNS are not limited to the regulation of the perception of pain. Gene deletion studies have helped to delineate the physiological properties of MORs. Expression of oprm1 is linked to maternal attachment [53], social interaction [54], motivation [55,56], learning [56] and impulsivity [3,57].

As global deletion of the oprm1 gene resulted in reduced self-administration of cocaine, amphetamine, nicotine, and cannabinoid, it also impaired the animals’ behaviour where they displayed signs of autistic-like behaviour [3,58]. Furthermore, selective approaches in gene manipulation revealed more potentials. Recent studies have shown that conditional knockout (KO) of oprm1 in the forebrain GABAergic neurons reduced the consumption of alcohol and decreased alcohol-associated conditioned place preference (CPP) in mice [59]. CPP is an experimental technique that is used to monitor the rewarding effect of drugs. A recent study by Reeves and colleagues showed that conditional knockout of MOR in the thalamo-striatal type 2 vesicular glutamate transporter-expressing synapses (vGluT2) inhibited glutamate transmission at those synapses and disrupted oxycodone-related CPP without interfering with its antinociceptive properties [60]. Interestingly, these mice did not show withdrawal symptoms following treatment with naloxone. Meanwhile, activation of MORs in the NAc shell has been reported to regulate appetitive behaviour [61].

3.2. К-opioid receptors (KORs)

Unlike MORs, activation of К-opioid receptors (KORs) produces aversion in the form of dysphoria. During the addiction cycle, KORs are mainly recruited by the stress system [62] during withdrawal or prolonged abstinence to maintain dependence by mediating the emergence of negative affect. This in turn facilitates drug seeking behaviour leading to escalations of drug consumption [3].

While MOR activation results in the disinhibition of VTA dopaminergic neurons, KOR agonists inhibit the release of dopamine from dopaminergic terminals in the NAc and the PFC, a process responsible for KOR-induced aversion [63]. Animal studies have shown a remarkable reduction of drug self-administration and drug seeking [64], and intracranial self-stimulation [65] in response to agonist-induced activation of KORs. These findings opened the door for more studies to explore the potentials of KORs activation as an approach to prevent opioid addiction. A study by Zamarripa et al, explored this possibility with different KOR agonists, salvinorin A and nalfuratine. Interestingly, they found that combined administration of KOR agonists with oxycodone significantly reduced oxycodone self-administration in Rhesus monkeys [66].

3.3. δ-opioid receptors (DORs)

Like other opioid receptors, δ-opioid receptors (DORs) play a major role in the development of drug dependency. However, DORs are involved in addiction through the regulation of the motivation rather than mediating the rewarding effect of drugs [3]. Although DORs are not necessary for the perception of the drug reward, which is evidenced by unaltered self-administration of morphine and alcohol following gene deletion, they seem to be more relevant to the formation of the drug – context association. Gene deletion of oprd1 in mice subsequently blunted their ability to form or retrieve CPP towards morphine or CPA (conditioned place aversion) towards lithium [67]. Nevertheless, DORs have also been linked to the regulation of the mood and the modulation of stress-coping behaviour in which activation of DORs was found to alleviate depression-like symptoms [3,68].

3.4. Opioid receptor signalling and trafficking

As mentioned above, Opioid receptors belong to the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family and are heavily distributed throughout the CNS and some peripheral organs. When activated, opioid receptors trigger signalling cascade through their main functional subunits, Gα and Gβγ. Adenylyl cyclase (AC) is one of the main effectors of the G-protein subunits in which stimulation or inhibition of certain AC isoforms serves different functions. In general, Gαs stimulates all AC isoforms from AC I – AC IX and only AC I, V, VI are inhibited by Gαi/o. On the other hand, AC II, IV and VII are stimulated by Gβγ while AC I, V, VI and VIII are inhibited by the same subunit. Besides AC, Gβγ subunits also regulate different effectors such as, but not limited to, G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channel (GIRK), G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) 2/3, phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) [52].

Following the activation of opioid receptors, by for example endorphin or morphine, Gα and Gβγ are dissociated from one another and target various intracellular signalling pathways. During acute activation of the receptors, Gαi/o are recruited leading to inhibition of AC I, V and VI [69] whereas Gβγ stimulates the activity of AC II[70]. In contrast, prolonged or chronic activation of opioid receptors results in superactivation of AC I, V, VI and VIII [69], followed by a subsequent increase in cAMP, and superinhibition of AC II [70] when treatments are rapidly terminated by an antagonist [69,70]. Similar to GPCRs, opioid receptors undergo multiple conformational changes triggered by phosphorylation of the receptors followed by internalisation and desensitisation [71].

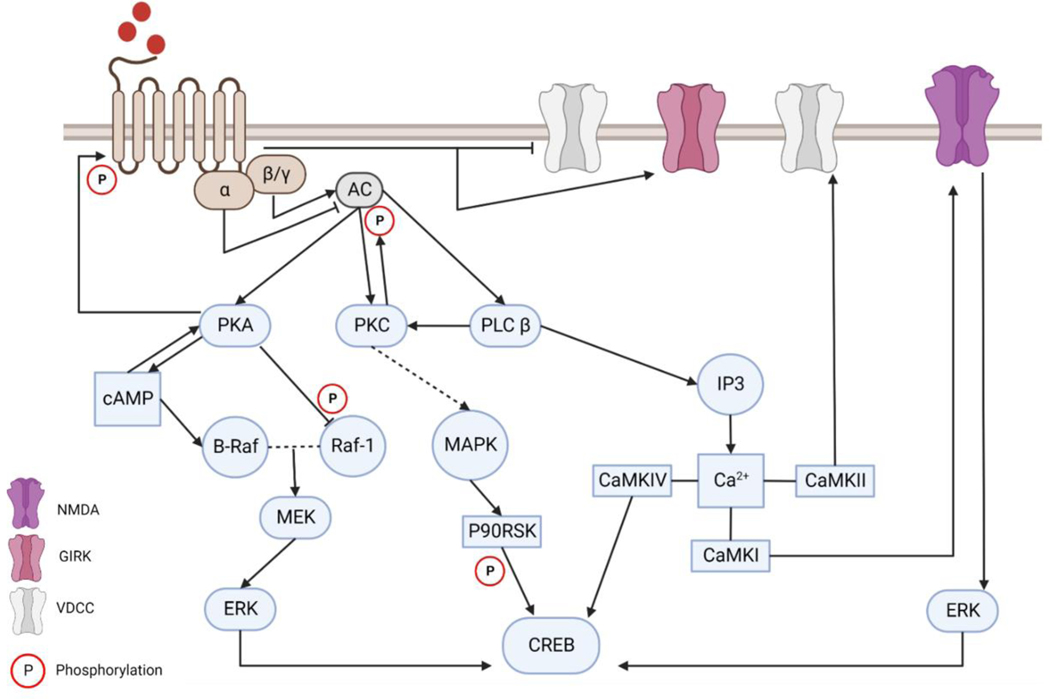

To induce their analgesic effect, opioid receptors control neuronal excitability by reducing neurotransmitter release, via inhibition of presynaptic VGCC (voltage-gated calcium channel), and promoting postsynaptic hyperpolarisation state, through the activation of GIRK [72]. This analgesic effect in conjunction with common opioid side effects such as respiratory depression and constipation are mediated through Gβγ [73]. The transition from pain management to drug dependency and development of withdrawal has been reported to be regulated by the cAMP signalling pathway (Figure.2). These events have been demonstrated at an electrophysiological level and were found to correspond to the changes in cAMP-dependent protein phosphorylation and the subsequent changes in AC and protein kinase A (PKA) levels. Briefly, acute administration of opioids reduced cell firing rate (pain relief), recovery of baseline cellular firing rate was achieved upon chronic exposure to drugs (tolerance), and several-fold increase in firing rate followed the exposure to antagonists (withdrawal and dependence) [74].

Figure.2: Intracellular signalling cascade following the activation of opioid receptors.

Activation of the G protein-coupled opioid receptors results in the dissociation of Gα and Gβγ. Acute activation of the receptor recruits Gαi/o leading to inhibition of AC I, V and VI, and recruits Gβγ resulting in the stimulation of AC II. The analgesic effect of opioid receptor is the product of inhibition of presynaptic VGCC and activation of GIRK via Gβγ. Dependency is regulated by cAMP signalling where prolonged activation of the receptors results in superactivation of AC leading to a rapid increase of cAMP. B-raf is activated by cAMP via Rap-1, which forms a dimer with Raf-1 and subsequently activate ERK via MEK. Intracellular Ca2+ is increased following the activation of IP3. Dissociated Gβγ activates PLCβ leading to the production of IP3 which mobilises Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum. Free Ca2+ bind to calmodulin (CAM) and modulate the function of multiple Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMKs) amongst them is CaMK IV which is the only CaMK with the ability to phosphorylate cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB). Activation of CREB can also be achieved via p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (p90RSK). Activation of PKC can be activated by the dissociated Gβγ or the free intracellular Ca2+ which results in the activation of the MAPK signalling cascade resulting in the activation of p90RSK. Opioid induced signalling cascades converge on the activation of the transcription factor CREB which is a crucial element of synaptic plasticity.

Two different signalling pathways were delineated in response to opioid exposure, one a canonical pathway and the other recently described non-canonical pathway. The canonical pathway starts with the acute stimulation of the receptor by the ligand resulting in the dissociation of the Gα and Gβγ from one another. G-protein subunits inhibit AC activities and subsequently inhibiting cAMP signalling pathway [75]. Liberated Gβγ binds to VGCC and inhibit the release of neurotransmitters, presynaptically, while it stimulates GIRK and facilitate hyperpolarisation postsynaptically. Stimulation of opioid receptors, also, recruit G-protein receptor kinase (GRK) and β-arrestin which phosphorylate and desensitise opioid receptors, respectively [76]. Prolonged stimulation of opioid receptors activates the non-canonical signalling pathway. This pathway involves the phosphorylation of opioid receptors by Src which is recruited by β-arrestin which leads to the conversion of opioid receptors to a receptor tyrosine kinase-like entity (RTK) resulting in the activation of Ras/Raf-1 [77]. Activated Ras and Raf-1 stimulate the activity of AC V and VI as well as the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathway. This non-canonical signalling pathway was demonstrated by Zhang, et al using human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells expressing OPRM1 [77] and confirmed in mice [76].

Studying the signalling pathways in which addiction is conducted and mediated between the different regions in the brain is key to understanding addiction and the potential for the development of diagnostic tests. Transcriptional consequences arising from the exposure to an opioid in the previously outlined regions indicates how reward perception and substance use disorder propagate. However, like other mental disorders, external factors play a crucial part in vulnerability to addiction. These are the factors that shape the individual differences in terms of perception and behavioural output via the introduction of stable changes in gene expression. The study of the epigenetics of addiction allows the study of the environmental influences and triggers that render some individuals more prone to the development of vulnerability to substance use disorder.

4. Epigenetics of Addiction

The effect of external stimulants on shaping an individual’s behaviour is indisputable. Twin studies elegantly showcase the enormous effect of the environment in producing the variety of personal traits and behavioural responses regardless of identical genetic compositions [78,79]. The environmental influence can take many forms and recent advances in the field of epigenetics highlight these changes. Epigenetics refers to reversible, however long lasting, and even transmittable, changes that alter the regulation of genes expression without interfering with the sequence of the DNA. This biological phenomenon takes place through different mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone modifications and/or the recruitment of non-coding RNA (RNA).

4.1. Methylation

DNA methylation is a stable epigenetic mechanism catalysed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and involves the addition of methyl group to the C5 position of the cytosine-phosphoguanine (CpG). The position where DNA methylation occurs can predict the transcriptional outcomes of the gene. Generally, DNA methylation in the promotor site of the gene results is transcriptional repression whereas methylation in the gene body is often associated with activation [80].

Following exposure to opioids, gene-specific DNA methylation can vary in different brain regions and different exposure time to opioids, and the same applies to global 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and 5-methylhydroxycytosine (5hmC). While global 5hmC was reported to increase in the hypothalamus, hippocampus and cerebral cortex following chronic exposure to morphine, it has been found to be decreased in the midbrain [81]. Repeated intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of oxycodone was found to not only alter rats’ hippocampal levels of 5-mC and 5-hmC, but also triggered transcriptional upregulation of crucial synaptic plasticity associated genes. This increase in mRNA expression was captured for synaptophysin (Syp), postsynaptic density protein 95 (Psd95), Synapsin 1 (Syn1), activity regulated cytoskeleton associated protein (Arc/Arg3.1), SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains protein 2 (Shank2), growth associated protein 43 (Gap43), Synaptopodin (Synpo), Synaptobrevin (Vamp1), Neurogranin (Nrgn) [82]. Stress- and cued-induced reinstatement of oxycodone CPP resulted in upregulation of the DNA demethylation catalyst ten eleven translocations (Tet1) and downregulation of the methylation catalyst DNA methyltransferase (Dnmt1), which suggest that the observed global decrease in hippocampal 5-mC [82] and the increased expression of 5-hmC [83] might be caused by discrepancies in the equilibrium of both catalysts in favour of global hypomethylation. Repeated oxycodone exposure also reduced DNA methylation of Arc, discs large MAGUK scaffold protein 1 (Dlg1), Dlg4 and Syn1 genes which was accompanied by an increase in gene expression [83].

Similar transcriptional changes have been reported in the VTA. Upregulation of Tet1 in conjunction with downregulation of Dnmt1 and the corresponding increase of 5-hmC and decrease of 5-mC expressions were observed in the rats’ VTA following repeated i.p. administration of oxycodone [84]. Repeated exposure to oxycodone altered synaptic associated genes in the VTA in the same manner reported from hippocampal tissues. Hypomethylation of exon 1 and exon 2 of Syp and Psd95, respectively, corresponded with transcriptional increase in mRNA level [84]. Heroin self-administration also resulted in global DNA methylation changes in the NAc. Rats trained to self-administer heroin showed hypomethylation of the Gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit D (GABRD) concomitant with an increase in the levels of mRNA [85]. Interestingly, these changes were only displayed by rats who self-administer heroin and not by heroin yoked groups who received the same dose of heroin at the same time their counterparts made the decision to self-administer the drug [85]. These results suggest a novel therapeutic target to tackle drug-seeking behaviour and, also, suggest a pivotal role of the process of decision making on the severity of dependence.

A recent genome-wide correlation study by Liu A. et al. 2021 investigated the differentially co-methylated gene modules associated with opioid addiction in human post-mortem brain tissue. Using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA), they explored the possible canonical pathways and inferred the upstream transcription regulators indicated by the list of differentially methylated and differentially expressed genes. Immune-related translational regulators including Jun, NFКB1, CEBPB, STAT1, SMARCA4 and RELA were reported to be hypomethylated and upregulated in the prefrontal cortex of human OUD brain [86].

In peripheral blood, heroin addiction has been found to increase DNA methylation in the promoter region of the BDNF gene [87] which is negatively correlated with BDNF levels in the blood [88]. Hyper methylation of region 2 of OPRM1 promoter in opium users has also been reported [89]. This could explain tolerance and physical dependence which might be attributed to the decreased expression of OPRM1 transcript [89]. Recently, Zhang, et al., showed a significant association between single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and methylation of CpG sites in DRD1 (rs5326-CpG_174872203) and DRD2 (rs1799978-CpG_113345668) genes in both heroin users and healthy controls [90]. However, a unique SNP-CpG pairs rs4867798-CpG_174872884 and rs5326-CpG_174872884 in DRD1 gene were identified in heroin users [90]. Finally, an epigenome-wide association study of opioid dependent European-American women identified three differentially methylated CpG sites. Those were mapping to PARG, RERE and CFAP77 genes, all of which are involved in chromatin remodelling, cell processes and DNA binding [91].

4.2. Histone modification

Histones are grouped proteins that surround the DNA to form the chromatin. The N-terminal tail of the histones can be covalently modified resulting in either a loose or tight chromatin which determines the accessibility to the DNA which gene expression depends on. Histone octamers are formed by a combination of four proteins: H2A, H2B, H3 and H4. In general, histone acetylation leads to a looser and more open chromatin which subsequently facilitates gene expression. Histone acetylation of lysine residues on H3 tail was the primary focus of drug-induced histone modification whereas the H4 tail did not receive as much attention.

Exposure to opioids, whether experimenter- or self-administered, has been reported to increase H3 acetylation within the mesolimbic system. Specifically, morphine has been reported to increase acetylation at H3K9 in the VTA [92], locus coeruleus [92] and the orbitofrontal cortex [93]. Increased H3K14 acetylation has been also reported in the basolateral amygdala [94]. In the NAc, exposure to heroin has been found to increase acetylation at H3K18, H4K5, H4K8 [95], H3K23 and H3K27 [96] while the last two were also observed in the dorsal striatum [96].

Using ATAC-seq (assay for transposase accessible chromatin sequencing) coupled with fluorescence-assisted nuclei sorting (FAN), Egervari and colleagues investigated chromatin accessibility in the dorsal striatum following chronic exposure to heroin [97]. They reported high neuronal ATAC signal enriched for EZH2 (which is a histone-lysine N-methyltransferase enzyme encoded by enhancer of zeste homolog 2 gene) and H3K4me1 binding sites marked enhancers. Accessible chromatin peaks from heroin users were enriched for genes involved in crucial neuronal processes such as post-synaptic density, neuronal projections, and glutamate receptor(s) activity [97]. The most significantly affected locus in those neurons was the SRC family tyrosine kinase FYN, which led to increased transcription of FYN gene which was captured in neurons of the dorsal striatum of chronic heroin users, heroin self-administrating rats and primary neuronal culture. Moreover, increased FYN kinase expression was observed in addition to an increased phosphorylation of Tau. Inhibition of FYN kinase activity by saracatinib attenuated cue-induced heroin reinstatement in self-administering rats [97].

Unlike histone acetylation, our knowledge of histone methylation is lacking. Chronic morphine administration has been found to downregulate G9a in the rat’s NAc. G9a is a histone methyltransferase that catalyses the mono- and dimethylation of H3K9 and is part of the repressive machinery in neurons which regulates gene expression in response to negative environmental stimuli [98]. Morphine-induced G9a and subsequent H3K9me2 downregulation in the NAc was concurrent with decreased expression of Δ-FosB suggesting a repressive regulatory role of G9a/H3K9me2 over FosB [98].

4.3. Non-coding RNAs

4.3.1. Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA)

lncRNA are >200 bp long RNA transcripts known to contribute to biological complexity directly, by regulating gene expression through transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms, and indirectly as epigenetic regulators of gene expression through chromatin remodelling. Regardless of their temporal and cellular specificity, our understanding of the role of lncRNA in opioid addiction is limited. However, many studies in the field of addiction have been devoted to understanding the role and importance of lncRNA in addiction. Here, we focus on opioid addiction.

A study on the post-mortem human NAc of heroin users and transcription regulation was revisited by Michelhaugh and colleagues in 2011 using lncRNA annotations in Affymetrix microarray data [99]. At least 10 lncRNAs were identified in the microarray data, 5 of which were reproducibly detected in the NAc. These are myocardial infarction associated transcript (MIAT), maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3), nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1) and 2 (NEAT2), and empty spiracles homeobox 2 opposite strand (EMX2OS). The expression of MIAT, NEAT1 and 2, and MEG3 were found to be up-regulated in the NAc of heroin users relative to healthy controls [99]. Another study conducted on rats investigated the expression of lncRNA in different brain regions following repeated morphine exposure [100]. The result was similar to the microarray study, with increased levels of MIAT1 observed in the hypothalamus and striatum. Expression of MIAT1 was not changed in the PFC and the hippocampus but decreased in the midbrain following morphine treatment. Alongside MIAT1 the group investigated other lncRNAs. Amongst them were H19, MALAT1 and BC1. Expression levels of these lncRNA were altered in the PFC, striatum, midbrain, and hypothalamus following the treatment with morphine [100]. Although each of these lncRNAs has a specific function, MEG3 was strikingly implicated in the vulnerability to heroin addiction in a genome-wide association study [101]. Furthermore, MEG3 was found up-regulated in the mouse neuronal cell line, HT22, following morphine treatment along with an increase in the expression of c-fos, ERK and beclin-1. Silencing MEG3 in those cells helped mitigate cell autophagy triggered by morphine treatment [102].

4.3.2. Micro-RNA (miRNA)

miRNAs are small (22 – 23 nucleotide) single stranded RNA that play a key role in regulating gene expression. They function by silencing the gene and inhibiting their translation into encoded proteins through binding to the 3’UTR (three prime untranslated region) of the target gene. Although extensive research of opioid-associated roles of miRNA is still needed, miRNAs have been found to play important roles in opioid addiction. miR-339 was found to down-regulate the expression of MOR in the hippocampus following repeated exposure to fentanyl and morphine [103]. On the other hand, miR-190 levels were downregulated following exposure to fentanyl, but not morphine, via β-arrestin2-mediated ERK phosphorylation [104]. miR-218 levels were found to decrease in the NAc following exposure to heroin while overexpression of miR-218 in the NAc was reported to partially inhibit heroin self-administration via targeting MeCP2 [105]. The let-7 family of miRNAs was also studied and linked with opioid tolerance. The expression level of let-7 increased following repeated exposure to morphine leading to down regulation of MOR by let-7 resulting in tolerance in mice which was partially restored by let-7 ablation [106].

5. Screening for Opioid Vulnerability

Treatments for drug abuse in general are set to reduce dependency by reducing consumption. Although maintenance therapy has proved to be useful in some cases, the problem with addiction is multidimensional and relapse is always a possibility even after a prolonged abstinence. This limits the robustness of treatments in the long-term. In this regard, studies began to explore whether a propensity to dependency can be detected at an early stage, which could help in preventing SUD.

Screening methods have been developed in the hope of detection and/or assessment of aberrant use of prescribed opioid. These include questionnaires that are designed to predict vulnerable patients who could be at high risk of developing SUD. Questions cover patients’ own history (and family history) of smoking or drug use as well as indication of previous or outstanding mental health problems [107,108]. Examples of such screening methods include the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) [108] and the Screener and opioid Assessment for Pain Patients (SOAPP-R) [107]. The design of these questionnaires considers the environmental factors that could influence prescribed drugs misuse which render them useful for identifying risk factors. However, these measurement tools ignore the prominent role of genetics.

The genetics of addiction aims to distinguish between potential addicts from healthy subjects by looking at the genetic component in terms of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). Being the major site of action for the addictive and the analgesic properties of opioid, MOR encoding gene (OPRM1) has received a lot of attention. The A118G SNP of the ORPM1 (re1799971) has been extensively studied and reported to result in a decreased expression of OPRM1 mRNA leading to a decreased levels of MOR. Moreover, the A118G SNP increases the binding of B-endorphin and alters stress/HPA Axis responsivity in humans [109], which is considered one of the main factors in vulnerability [110]. Interestingly, the combination of the A118G SNP with the OPRK1 variant (rs16918875) was identified in a study of an Indian cohort and has been found to increase the risk to heroin addiction [111].

Ethnicity is a critical factor to account for when it comes to screening for genetic differences. A study in China reported multiple SNPs of the PDYN (prodynorphin) gene that they found to be associated to the increased risk of opioid addiction. Amongst them were SNPs in the PDYN gene 68 bp (rs35286281), rs1022563 and rs910080 [112]. This was also confirmed by a study on European Americans which reported the rs1022563 SNP in heroin addicts of both sexes and rs910080 which was found to be more relevant to the female subset of the cohort. However, this finding was not observed in American heroin users of an African descent [113]. The list in genetic screening for SNPs extends to cover all the opioid-associated pathways, the addiction-related neurotransmitters, and their receptors, as well as polymorphisms of numerous growth factors and neuropeptides [101,114].

A study by Donaldson and colleagues probed 16 SNPs involved in the reward pathways obtained from patients with opioid prescription or heroin addiction. The group developed Neuro Response (NeuR) which is a prediction algorithm that detects patients with risk for opioid addiction based on their genotype information [115]. More studies have aimed to develop screening methods that incorporate both measures (i.e., genetic, and phenotypic risk factors) in conjunction with specialised detection algorithms. Proove Opioid Risk Profile (POR) is a commercially available test that assess patients with phenotypic risk factors and combines this with genotypic information collected from buccal swaps. The test includes an algorithm that calculates a risk score for each patient, using the phenotypic and genotypic data that correlates to the level of risk of SUD [116].

6. Concluding Remarks

Substance use disorder is a global problem that has costly consequences. Despite the medical and healthcare expenses, the life cost of addiction remains significant. Efficient interventions with respect to treatment and/or rehabilitation are still needed as relapse remains a prominent limitation.

SUD is a complex disorder with many factors playing key roles in the development of vulnerability. The mounting evidence pertinent to the mechanism of action of the drugs and how different regions of the brain are employed to skew normal cognition to favour the maintenance of dependence are important for the identification of medical and psychological interference with the progression of such illness. However, the mere fact that genetic propensities could be influenced by environmental factors does not make the mission for discovering more potent treatment any easier. However, the epigenetics of addiction has the potential to uncover the molecular underpinnings of vulnerability. These stable changes in the DNA are easily accessible and detectable with the technological advancement in biomolecular tools and assays.

The topic of addiction is rich in studies that successfully unfolded the transcriptional and epigenetics consequences of the illness as well as the tremendous efforts to improve the current treatment scheme. It is now the time to explore the route of pre-emptive solutions exploiting the available knowledge to prevent patients from falling for dependence on prescribed medications.

7. Expert Opinion

With all the technological advancements in screening for genetics and the breadth of information provided by numerous disciplines, which explain the problem of addiction from different viewpoints, the field is still lacking a targeted and robust intervention methods. The complexity of SUD is, understandably, limiting the discovery of treatments that have the therapeutic potentials to benefit patients on the long term regardless of their ethnic background, environment, and the severity of dependence. All these are valid factors that influence the different stages of addiction as highlighted in the previous sections. Therefore, more research focus on prevention could be of a great value. For example, one way to aid patients with SUD is to identify opioid-vulnerable patients before issuing a prescription of opioids. Instead, clinicians should be able to distinguish this group of patients. This means that we are in need of robust biomarkers that characterise vulnerability to a specific class of drugs or at least to call attention to general vulnerability to SUD. Although the screening methods outlined previously have delineated multiple targets, ethnicity remains an issue. Additionally, applicable diagnostics require specific targets that can be captured regardless of ethnicity and sex. Nevertheless, these targets should also be accessible, rapid, and easy to detect.

In terms of accessibility to biomarkers, extracellular vesicles (EVs) offer promising opportunities and outcomes. EVs are small vesicles secreted by cells, as means of communication, carrying information in the form of RNA, proteins, and lipids. The RNA composition of EVs covers coding and non-coding RNA. Furthermore, EVs offers enormous potentials to serve as drug delivery tools and as carriers of biomarkers for diseases [117–119]. Interestingly, in addition to all the different types of EVs derived from variety of cell types, brain derived EVs were found circulating in blood samples and have been isolated using their content as a marker to separate the type of cells they were released from [120]. Nonetheless, EVs content alterations has been reported following exposure to substance of abuse [118].

Until now, most studies in the field of addiction examine the consequences of addiction (molecular or behavioural) by comparing findings with respect to healthy and clean counterparts. While this approach is essential for the study of certain aspects of addiction, it introduces a limitation. It is well accepted that only a proportion of the population would become addicted following exposure to drugs with variable degrees of severity [121]. This necessitates the study of addiction in particular groups. We need to stratify vulnerability before the exposure to drugs by identifying these individuals in comparison to invulnerable ones who have been exposed to the same drugs. By doing so, we will be able to identify individuals at risk to addiction. Using rodents to model addiction, this can be achieved using unconventional design of experimental protocols that capture all possible responses towards the administration of drugs [122,123]. Also, these protocols should continue to apply freedom of choice for animals to self-administer the drug of interest [123].

Article highlights:

The global rise in the opioid epidemic combined with the absence of robust treatments for addiction is a debilitating burden that needs immediate attention.

Identification of novel targets to tackle this problem requires comprehensive understanding of the reward system and how different subregions in the brain are employed by opioids to maintain dependence.

The state of dependence propagates because of activation of specific opioid receptors that are targeted by exogenous opioids leading to the activation of signalling cascades and subsequent alterations of genes regulation.

Epigenetics of addiction provides different platforms to understand and potentially tackle the ongoing problem of addiction.

Funding

This manuscript was funded by NIH/NIDA 1U01DA045300-01A1, U54MD010706-CHH and start-up funding from Queens University Belfast.

Footnotes

Reviewers Disclosure

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Declaration of interest

G.H. is a founder of Altomics Datamation Ltd. and a member of its scientific advisory board. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (*) or of considerable interest (**) to readers.

- 1.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(8):760–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turton S, Lingford-Hughes A. Neurobiology and principles of addiction and tolerance. Medicine. 2020;48(12):749–753. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darcq E, Kieffer BL. Opioid receptors: drivers to addiction? Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2018;19(8):499–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayes A, Herlinger K, Paterson L, et al. The neurobiology of substance use and addiction: evidence from neuroimaging and relevance to treatment. BJPsych Advances. 2020;26(6):367–378. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AR, Nunes EV, Bisaga A, et al. Development of a cascade of care for responding to the opioid epidemic. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2019;45(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy N, Lord LJ, Lobo DN. UK recommendations on opioid stewardship. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnelly K. Addiction Services in Northern Ireland. 2022. p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loganathan K, Ho ETW. Value, drug addiction and the brain. Addictive behaviors. 2021;116:106816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Everitt BJ, Belin D, Economidou D, et al. Neural mechanisms underlying the vulnerability to develop compulsive drug-seeking habits and addiction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2008;363(1507):3125–3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heinsbroek JA, De Vries TJ, Peters J. Glutamatergic systems and memory mechanisms underlying opioid addiction. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2021;11(3):a039602. **Comprehensive review of the interactions between glutamatergic, dopaminergic, and opioid signalling to mediate the cycle of addiction.

- 11.Vashchinkina E, Panhelainen A, Aitta-Aho T, et al. GABAA receptor drugs and neuronal plasticity in reward and aversion: focus on the ventral tegmental area. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2014;5:256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham KA, Anastasio NC. Serotonin at the nexus of impulsivity and cue reactivity in cocaine addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:460–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birdsong WT, Williams JT. Recent progress in opioid research from an electrophysiological perspective. Molecular pharmacology. 2020;98(4):401–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hearing M. Prefrontal-accumbens opioid plasticity: Implications for relapse and dependence. Pharmacological research. 2019;139:158–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, et al. Addiction circuitry in the human brain. Focus. 2015;13(3):341–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Limpens JH, Damsteegt R, Broekhoven MH, et al. Pharmacological inactivation of the prelimbic cortex emulates compulsive reward seeking in rats. Brain research. 2015;1628:210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barker JM, Taylor JR, Chandler LJ. A unifying model of the role of the infralimbic cortex in extinction and habits. Learning & Memory. 2014;21(9):441–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hearing MC, Jedynak J, Ebner SR, et al. Reversal of morphine-induced cell-type–specific synaptic plasticity in the nucleus accumbens shell blocks reinstatement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113(3):757–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper S, Robison A, Mazei-Robison MS. Reward circuitry in addiction. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14:687–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bossert JM, Stern AL, Theberge FR, et al. Role of projections from ventral medial prefrontal cortex to nucleus accumbens shell in context-induced reinstatement of heroin seeking. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(14):4982–4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucantonio F, Caprioli D, Schoenbaum G. Transition from ‘model-based’to ‘model-free’behavioral control in addiction: involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex and dorsolateral striatum. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:407–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peoples LL. Will, anterior cingulate cortex, and addiction. Science. 2002;296(5573):1623–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jalabert M, Bourdy R, Courtin J, et al. Neuronal circuits underlying acute morphine action on dopamine neurons. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences. 2011;108(39):16446–16450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klawonn AM, Malenka RC, editors. Nucleus accumbens modulation in reward and aversion. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology; 2018: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wassum KM, Izquierdo A. The basolateral amygdala in reward learning and addiction. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2015;57:271–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roura‐Martínez D, Ucha M, Orihuel J, et al. Central nucleus of the amygdala as a common substrate of the incubation of drug and natural reinforcer seeking. Addiction Biology. 2020;25(2):e12706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ubaldi M, Ricciardelli E, Pasqualini L, et al. Biomarkers of hippocampal gene expression in a mouse restraint chronic stress model. Pharmacogenomics. 2015;16(5):471–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kutlu MG, Gould TJ. Effects of drugs of abuse on hippocampal plasticity and hippocampus-dependent learning and memory: contributions to development and maintenance of addiction. Learning & memory. 2016;23(10):515–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathis V, Kenny PJ. From controlled to compulsive drug-taking: The role of the habenula in addiction. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2019;106:102–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hikosaka O, Sesack SR, Lecourtier L, et al. Habenula: crossroad between the basal ganglia and the limbic system. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(46):11825–11829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loonen AJ, Ivanova SA. Evolution of circuits regulating pleasure and happiness with the habenula in control. CNS spectrums. 2019;24(2):233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu Y-WA, Wang SD, Wang S, et al. Role of the dorsal medial habenula in the regulation of voluntary activity, motor function, hedonic state, and primary reinforcement. Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34(34):11366–11384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nuno-Perez A, Tchenio A, Mameli M, et al. Lateral habenula gone awry in depression: bridging cellular adaptations with therapeutics. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2018;12:485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simmons SC, Shepard RD, Gouty S, et al. Early life stress dysregulates kappa opioid receptor signaling within the lateral habenula. Neurobiology of Stress. 2020;13:100267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cerniauskas I, Winterer J, de Jong JW, et al. Chronic stress induces activity, synaptic, and transcriptional remodeling of the lateral habenula associated with deficits in motivated behaviors. Neuron. 2019;104(5):899–915. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fowler CD, Lu Q, Johnson PM, et al. Habenular α5 nicotinic receptor subunit signalling controls nicotine intake. Nature. 2011;471(7340):597–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gardon O, Faget L, Chung PCS, et al. Expression of mu opioid receptor in dorsal diencephalic conduction system: new insights for the medial habenula. Neuroscience. 2014;277:595–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boulos L-J, Ben Hamida S, Bailly J, et al. Mu opioid receptors in the medial habenula contribute to naloxone aversion. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45(2):247–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Root DH, Melendez RI, Zaborszky L, et al. The ventral pallidum: Subregion-specific functional anatomy and roles in motivated behaviors. Progress in neurobiology. 2015;130:29–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ho C-Y, Berridge KC. An orexin hotspot in ventral pallidum amplifies hedonic ‘liking’for sweetness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(9):1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahler SV, Vazey EM, Beckley JT, et al. Designer receptors show role for ventral pallidum input to ventral tegmental area in cocaine seeking. Nature neuroscience. 2014;17(4):577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knowland D, Lilascharoen V, Pacia CP, et al. Distinct ventral pallidal neural populations mediate separate symptoms of depression. Cell. 2017;170(2):284–297. e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faget L, Zell V, Souter E, et al. Opponent control of behavioral reinforcement by inhibitory and excitatory projections from the ventral pallidum. Nature communications. 2018;9(1):849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tooley J, Marconi L, Alipio JB, et al. Glutamatergic ventral pallidal neurons modulate activity of the habenula–tegmental circuitry and constrain reward seeking. Biological psychiatry. 2018;83(12):1012–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kupchik YM, Prasad AA. Ventral pallidum cellular and pathway specificity in drug seeking. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2021;131:373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirby L, Zeeb F, Winstanley C. Contributions of serotonin in addiction vulnerability. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(3):421–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang KW, Ochandarena NE, Philson AC, et al. Molecular and anatomical organization of the dorsal raphe nucleus. Elife. 2019;8:e46464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, Li C-Y, Xi W, et al. Rostral and caudal ventral tegmental area GABAergic inputs to different dorsal raphe neurons participate in opioid dependence. Neuron. 2019;101(4):748–761. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samson KR, Xu W, Kortagere S, et al. Intermittent access to oxycodone decreases dopamine uptake in the nucleus accumbens core during abstinence. Addiction Biology. 2022;27(6):e13241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pathan H, Williams J. Basic opioid pharmacology: an update. British journal of pain. 2012;6(1):11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le Merrer J, Becker JA, Befort K, et al. Reward processing by the opioid system in the brain. Physiological reviews. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bian J-M, Wu N, Su R-B, et al. Opioid receptor trafficking and signaling: what happens after opioid receptor activation? Cellular and molecular neurobiology. 2012;32:167–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moles A, Kieffer BL, D’Amato FR. Deficit in attachment behavior in mice lacking the μ-opioid receptor gene. Science. 2004;304(5679):1983–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Becker JA, Clesse D, Spiegelhalter C, et al. Autistic-like syndrome in mu opioid receptor null mice is relieved by facilitated mGluR4 activity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(9):2049–2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papaleo F, Kieffer BL, Tabarin A, et al. Decreased motivation to eat in μ‐opioid receptor‐deficient mice. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;25(11):3398–3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lubbers ME, van den Bos R, Spruijt BM. Mu opioid receptor knockout mice in the Morris Water Maze: a learning or motivation deficit? Behavioural brain research. 2007;180(1):107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boulos L-J, Nasseef M, McNicholas M, et al. TouchScreen-based phenotyping: altered stimulus/reward association and lower perseveration to gain a reward in mu opioid receptor knockout mice. Scientific reports. 2019;9(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Charbogne P, Kieffer BL, Befort K. 15 years of genetic approaches in vivo for addiction research: Opioid receptor and peptide gene knockout in mouse models of drug abuse. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:204–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ben Hamida S, Boulos LJ, McNicholas M, et al. Mu opioid receptors in GABAergic neurons of the forebrain promote alcohol reward and drinking. Addiction biology. 2019;24(1):28–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reeves KC, Kube MJ, Grecco GG, et al. Mu opioid receptors on vGluT2‐expressing glutamatergic neurons modulate opioid reward. Addiction biology. 2021;26(3):e12942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Castro DC, Oswell CS, Zhang ET, et al. An endogenous opioid circuit determines state-dependent reward consumption. Nature. 2021;598(7882):646–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chavkin C, Koob GF. Dynorphin, dysphoria, and dependence: the stress of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(1):373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tejeda HA, Counotte DS, Oh E, et al. Prefrontal cortical kappa-opioid receptor modulation of local neurotransmission and conditioned place aversion. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(9):1770–1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rüedi-Bettschen D, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD, et al. Attenuation of cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug seeking in squirrel monkeys: kappa opioid and serotonergic mechanisms. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210:169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomasiewicz HC, Todtenkopf MS, Chartoff EH, et al. The kappa-opioid agonist U69, 593 blocks cocaine-induced enhancement of brain stimulation reward. Biological psychiatry. 2008;64(11):982–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zamarripa CA, Naylor JE, Huskinson SL, et al. Kappa opioid agonists reduce oxycodone self-administration in male rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2020;237:1471–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Le Merrer J, Plaza-Zabala A, Del Boca C, et al. Deletion of the δ opioid receptor gene impairs place conditioning but preserves morphine reinforcement. Biological psychiatry. 2011;69(7):700–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Callaghan CK, Rouine J, Islam MN, et al. Differential effects of opioid receptor modulators on motivational and stress-coping behaviors in the back-translational rat IFN-α depression model. bioRxiv. 2019:769349. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nevo I, Avidor-Reiss T, Levy R, et al. Acute and chronic activation of the μ-opioid receptor with the endogenous ligand endomorphin differentially regulates adenylyl cyclase isozymes. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39(3):364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schallmach E, Steiner D, Vogel Z. Adenylyl cyclase type II activity is regulated by two different mechanisms: implications for acute and chronic opioid exposure. Neuropharmacology. 2006;50(8):998–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nagi K, Piñeyro G. Regulation of opioid receptor signalling: implications for the development of analgesic tolerance. Molecular Brain. 2011;4(1):1–9. *Detailed review on the molecular mechanisms and adaptations that contribute to tolerance.

- 72.Nassirpour R, Bahima L, Lalive AL, et al. Morphine-and CaMKII-dependent enhancement of GIRK channel signaling in hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(40):13419–13430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Richard-Lalonde M, Nagi K, Audet N, et al. Conformational dynamics of Kir3. 1/Kir3. 2 channel activation via δ-opioid receptors. Molecular pharmacology. 2013;83(2):416–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nestler EJ. Historical review: molecular and cellular mechanisms of opiate and cocaine addiction. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2004;25(4):210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang L, Kibaly C, Wang YJ, et al. Src‐dependent phosphorylation of μ‐opioid receptor at Tyr336 modulates opiate withdrawal. EMBO molecular medicine. 2017;9(11):1521–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lemel L, Lane JR, Canals M. GRKs as key modulators of opioid receptor function. Cells. 2020;9(11):2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang L, Loh HH, Law P-Y. A novel noncanonical signaling pathway for the μ-opioid receptor. Molecular Pharmacology. 2013;84(6):844–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Robinson GE. Beyond nature and nurture. Science. 2004;304(5669):397–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Malaab M, Renaud L, Takamura N, et al. Antifibrotic factor KLF4 is repressed by the miR-10/TFAP2A/TBX5 axis in dermal fibroblasts: insights from twins discordant for systemic sclerosis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2022;81(2):268–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Nestler EJ, Lüscher C. The molecular basis of drug addiction: linking epigenetic to synaptic and circuit mechanisms. Neuron. 2019;102(1):48–59. **Comprehensive review of the epigenetic remodelling in the brain in light of synaptic plasticity.

- 81.Barrow TM, Byun H-M, Li X, et al. The effect of morphine upon DNA methylation in ten regions of the rat brain. Epigenetics. 2017;12(12):1038–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fan X-Y, Shi G, Zhao P. Reversal of oxycodone conditioned place preference by oxytocin: Promoting global DNA methylation in the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2019;160:107778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fan XY, Shi G, He XJ, et al. Oxytocin prevents cue‐induced reinstatement of oxycodone seeking: Involvement of DNA methylation in the hippocampus. Addiction Biology. 2021;26(6):e13025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fan X-Y, Shi G, Zhao P. Methylation in Syn and Psd95 genes underlie the inhibitory effect of oxytocin on oxycodone-induced conditioned place preference. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;29(12):1464–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hong Q, Xu W, Lin Z, et al. Role of GABRD gene methylation in the nucleus accumbens in heroin-seeking behavior in rats. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2021;11:612200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu A, Dai Y, Mendez EF, et al. Genome-wide correlation of DNA methylation and gene expression in postmortem brain tissues of opioid use disorder patients. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;24(11):879–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xiao Y, Zhu Y, Li Y. Elevation of DNA Methylation in the Promoter Regions of the Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Gene is Associated with Heroin Addiction. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2021;71:1752–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schuster R, Kleimann A, Rehme M-K, et al. Elevated methylation and decreased serum concentrations of BDNF in patients in levomethadone compared to diamorphine maintenance treatment. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience. 2017;267:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ebrahimi G, Asadikaram G, Akbari H, et al. Elevated levels of DNA methylation at the OPRM1 promoter region in men with opioid use disorder. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2018;44(2):193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang J, Fan Y, Zhou J, et al. Methylation quantitative trait locus rs5326 is associated with susceptibility and effective dosage of methadone maintenance treatment for heroin use disorder. Psychopharmacology. 2021;238(12):3511–3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Montalvo-Ortiz JL, Cheng Z, Kranzler HR, et al. Genomewide study of epigenetic biomarkers of opioid dependence in European-American women. Scientific reports. 2019;9(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jalali Mashayekhi F, Rasti M, Rahvar M, et al. Expression levels of the BDNF gene and histone modifications around its promoters in the ventral tegmental area and locus ceruleus of rats during forced abstinence from morphine. Neurochemical research. 2012;37:1517–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wei L, Zhu Y-M, Zhang Y-X, et al. Microinjection of histone deacetylase inhibitor into the ventrolateral orbital cortex potentiates morphine induced behavioral sensitization. Brain research. 2016;1646:418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang Y, Lai J, Cui H, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylase in the basolateral amygdala facilitates morphine context-associated memory formation in rats. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2015;55:269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen W-S, Xu W-J, Zhu H-Q, et al. Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate on heroin seeking behavior in the nucleus accumbens in rats. Brain research. 2016;1652:151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Egervari G, Landry J, Callens J, et al. Striatal H3K27 acetylation linked to glutamatergic gene dysregulation in human heroin abusers holds promise as therapeutic target. Biological psychiatry. 2017;81(7):585–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Egervari G, Akpoyibo D, Rahman T, et al. Chromatin accessibility mapping of the striatum identifies tyrosine kinase FYN as a therapeutic target for heroin use disorder. Nature Communications. 2020;11(1):4634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sun H, Maze I, Dietz DM, et al. Morphine epigenomically regulates behavior through alterations in histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation in the nucleus accumbens. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(48):17454–17464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]