Abstract

Background:

Diphtheria is a vaccine-preventable disease. When vaccination coverage and population immunity are low, outbreaks can occur. We investigated a diphtheria outbreak in Lao People’s Democratic Republic that occurred during 2012–2013 and highlighted challenges in immunization services delivery to children in the country.

Methods:

We reviewed diphtheria surveillance data from April 1, 2012–May 31, 2013. A diphtheria case was defined as a respiratory illness consisting of pharyngitis, tonsillitis, or laryngitis, and an adherent tonsillar or nasopharyngeal pseudomembrane. To identify potential risk factors for diphtheria, we conducted a retrospective case-control study with two aged-matched neighborhood controls per case-patient in Houaphan Province, using bivariate analysis to calculate matched odds ratio (mOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Reasons for non-vaccination among unvaccinated persons were assessed.

Results:

Sixty-two clinical cases of diphtheria and 12 diphtheria-related deaths were reported in seven of 17 provinces. Among case-patients, 43 (69%) were <15 years old, five (8%) reported receiving three DTP doses (DTP3), 21 (34%) had received no DTP doses, and 35 (56%) had unknown vaccination status. For the case-control study, 42 of 52 diphtheria case-patients from Houaphan province and 79 matched-controls were enrolled. Five (12%) case-patients and 20 (25%) controls had received DTP3 (mOR = 0.4, CI = 0.1–1.7). No diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine was received by 20 (48%) case-patients and 38 (46%) controls. Among case-patients and controls with no DTP dose, 43% of case-patients and 40% of controls lacked access to routine immunization services.

Conclusion:

Suboptimal DTP3 coverage likely caused the outbreak. To prevent continued outbreaks, access to routine immunization services should be strengthened, outreach visits need to be increased, and missed opportunities need to be minimized. In the short term, to rapidly increase population immunity, three rounds of DTP immunization campaign should be completed, targeting children aged 0–14 years in affected provinces.

Keywords: Diphtheria, Lao PDR, Outbreak, Vaccination, Vaccine-preventable

1. Introduction

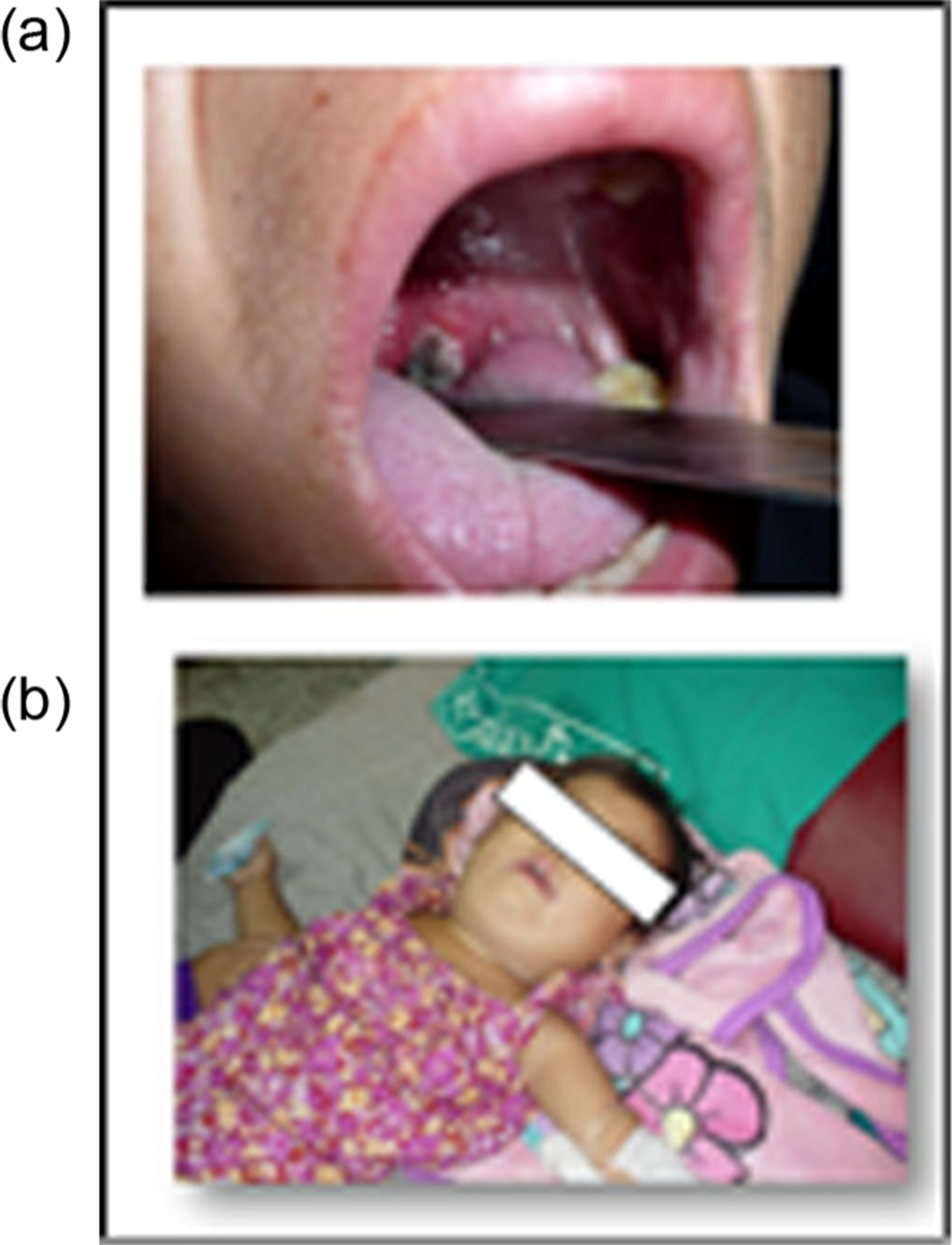

Diphtheria is a vaccine-preventable disease caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae that is transmitted from person-to-person through close physical contact and respiratory droplets. Severe diphtheria infection results in the formation of a pseudomembrane in the respiratory tract causing nasopharyngeal obstruction and death [1] (Fig. 1). Cardiovascular, neurological and renal complications resulting in death can occur weeks after acute infection [2]. Diphtheria case-fatality ratio (CFR) can be 10–50% depending on the severity of illness at presentation, vaccination status of the patient, timeliness of diphtheria anti-toxin (DAT) administration, and the level of medical care available [2]. In all countries, priority should be given to efforts to reach at least 90% coverage with three doses of Diphtheria and Tetanus Toxoids and Pertussis (DTP) vaccine in children below one year of age, in order to prevent ongoing transmission of diphtheria and outbreaks from occurring [3].

Fig. 1.

(a and b) Physical signs of diphtheria infection: pseudomembrane in 1a (Houaphan Province), and bull neck in 1b (Vientiane Capital)* – Lao People’s Democratic Republic, 2012–2013.

*Photos sourced from and used with permission from the National Center for Laboratory and Epidemiology, Ministry of Health, Lao People’s Democratic Republic.

A diphtheria vaccine has been available since 1923, and a combined DTP vaccine since 1948. In 1974, the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) was established by the World Health Organization (WHO) to provide universal childhood immunizations for six diseases: polio, tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis, measles and tuberculosis. WHO recommends that the routine childhood schedule should include a full primary course of three DTP doses (DTP3) to be administered in the first year of life. Three doses of diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine are required for a protective effect [4]. Globally, following increased DTP3 vaccination coverage, the number of cases of diphtheria reported to WHO decreased from 98,000 in 1980 [4] to 4490 in 2012 [4–6].

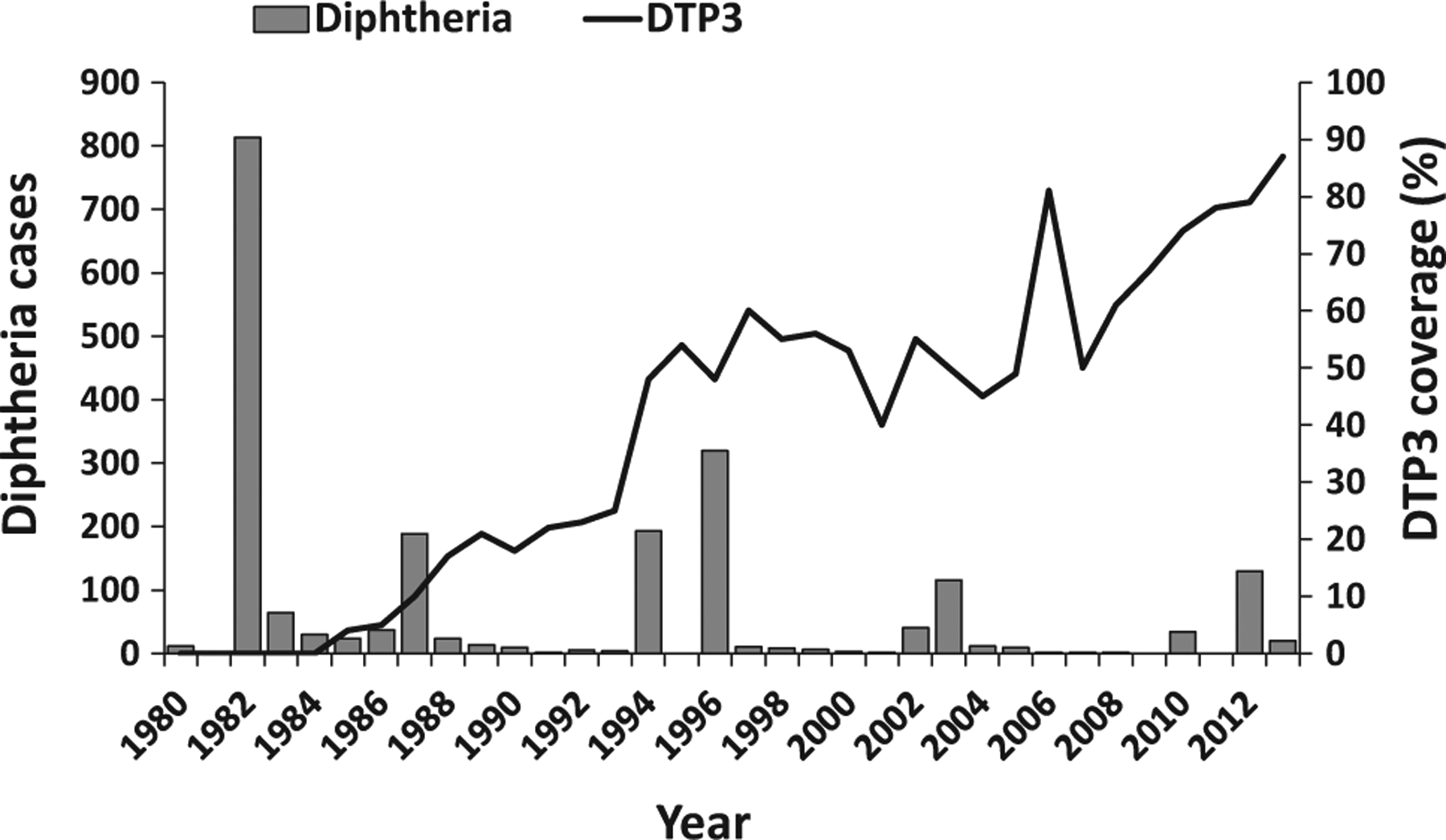

In Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), the national EPI started in 1979 [7]. In 2012, the routine childhood immunization schedule included three doses of DTP combined with Haemophilus influenzae type b and Hepatitis B virus antigens as a pentavalent vaccine administered at 6, 10 and 14 weeks [7]. Despite improvements in DTP3 coverage (from 4% in 1985, to 48% in 1996 to 78% in 2012), multiple outbreaks of diphtheria were reported (Fig. 2) [6]. During 1980–1996, the annual number cases of diphtheria reported to WHO was <100, except for outbreaks reported in 1982 (813) 1987 (189), 1994 (193), and 1996 (319). During 1997–2012, the number of annual reported cases of diphtheria was <15 each year, except for peaks in 2002 (40), 2003 (116), 2010 (34), 2012 (130) and 2013 (20) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Reported confirmed diphtheria cases* and estimated coverage** with three doses of diphtheria-containing vaccine (DTP3) among children aged 12–23 months – Lao People’s Democratic Republic, 1980–2013.

*Confirmed diphtheria cases reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) through the Joint Reporting Form (JRF), WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific Region.

**WHO/UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage: http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/incidences?c=LAO.

To identify the likely causes of the outbreak, we conducted an investigation to (1) review DTP3 vaccination coverage during 1980–2012, (2) describe characteristics of case-patients and the outbreak during April 1, 2012–May 31, 2013, and (3) conduct a case-control study to assess risk factors for diphtheria. As part of the investigation we also visited health care facilities at national, provincial, district and rural levels of the health system, to review available national protocols and guidelines on case detection and treatment.

2. Methods

We reviewed WHO/UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage with DTP3 for children aged one year in Lao PDR during 1980–2012. National EPI staff analyzed national and provincial administrative vaccination data for 2012 from the National Immunization Program (NIP) and calculated administrative DTP3 coverage as the number of DTP3 doses administered divided by the target population of surviving infants aged <1 year, with projected target population estimates based on the 2005 census from the Lao Statistics Bureau. We mapped administrative DTP3 coverage by province for 2012.

The MOH reported the annual number of cases of diphtheria to WHO and UNICEF using the WHO-UNICEF Joint Reporting Form. Diphtheria is one of 17 notifiable diseases reported to the National Center for Laboratory and Epidemiology (NCLE), Ministry of Health, Lao PDR. The national clinical case definition for diphtheria was an illness with laryngitis or pharyngitis or tonsillitis, and an adherent pseudomembrane of the tonsils, pharynx or nose. Provincial surveillance officers investigated patients with suspected diphtheria, using a case investigation form (CIF) to collect information on demographic characteristics, village and district of residence, symptom onset date, clinical symptoms, vaccination history, and laboratory specimens, if collected. In provinces with multiple reported cases, surveillance officers recorded data using a line-list form. Surveillance officers submitted CIFs and line-lists to the NCLE, and data assistants entered the information into an electronic database. We reviewed individual diphtheria case reports and the NCLE database to identify those meeting the national case definition. In Lao PDR, laboratory confirmation is not required for classification as a confirmed case.

During the investigation we visited nine health facilities (one city hospital, four provincial hospitals, one district hospital, three rural health facilities). We reviewed national protocols and guidelines on case detection and treatment and conducted informal interviews to determine health worker knowledge of diphtheria symptoms, investigation and treatment.

We conducted a retrospective case-control study during June 8–16, 2013 to determine risk factors for diphtheria during the outbreak in Houaphan Province where the majority of reported cases occurred. A case-patient was identified as a person meeting the surveillance case definition with illness onset during April 1, 2012–May 31 2013. Case-patients were identified by analyzing the NCLE surveillance database. Identified case-patients were then listed by district and village and categorized by age groups (<1 year, 1–4 years, 5–9 years, 10–14 years, 15–19 years, 20–24 years and ⩾ 25 years).

We selected two neighborhood controls for each case-patient, matched by age group, who were without history of diphtheria-like illness (symptoms of laryngitis or pharyngitis or tonsillitis) or history of hospitalization with diphtheria-like illness within two weeks before the illness onset date of the matched case-patients. This timeframe was chosen since the incubation period of diphtheria ranges from 1–10 days. For deceased case-patients, the next-of-kin was identified as a proxy case-patient and interviewed to obtain the necessary history for the study. Controls were selected by spinning a pen on the ground in front of the case-patient’s home and interviewers proceeded in the selected direction to the nearest household. If a member of that household met the control selection criteria, they were selected for the study. When a household had more than one member meeting the control criteria, the person closest in age to the matched case-patient was selected. If no control was identified, the interviewer proceeded to the next household until two controls per case-patient were enrolled in the study.

Interviews of case-patients and controls were conducted in their households using a questionnaire to collect information on demographic characteristics, fathers’ and mothers’ vocation, number of household members, number of persons in household sharing the same bed, travel history, history of chronic skin condition/lesions (defined as the presence of scaling rash or ulcer with well demarcated edges and membrane for a period of ⩾ 1 month), vaccination history, and solicited reasons for non-vaccination from a list of reasons that was provided. Vaccination history was confirmed by examining the interviewee’s vaccination card, if available. If the vaccination card was not available, the history was noted based on recall. During interviews, on-site verbal translation to local ethnic dialects was provided by the district health officer or the village leader. Informed verbal consent was obtained from participants or their guardians. For deceased case-patients, information was obtained from a parent or guardian.

Data were entered into Excel® (Microsoft Excel 2010, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and analyzed using SAS/STAT® software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). Bivariate conditional logistic regression analysis was performed to calculate matched odds ratios (mOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

3. Results

During April 1, 2012–May 31, 2013, a total of 168 suspected cases of diphtheria were reported from seven of 17 provinces to NCLE; however, only 62 met the clinical case definition. Among the latter, toxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheria was cultured from four of 21 patients from whom throat swabs were obtained. The median time between symptom onset and specimen collection was three days (range 1–30 days).

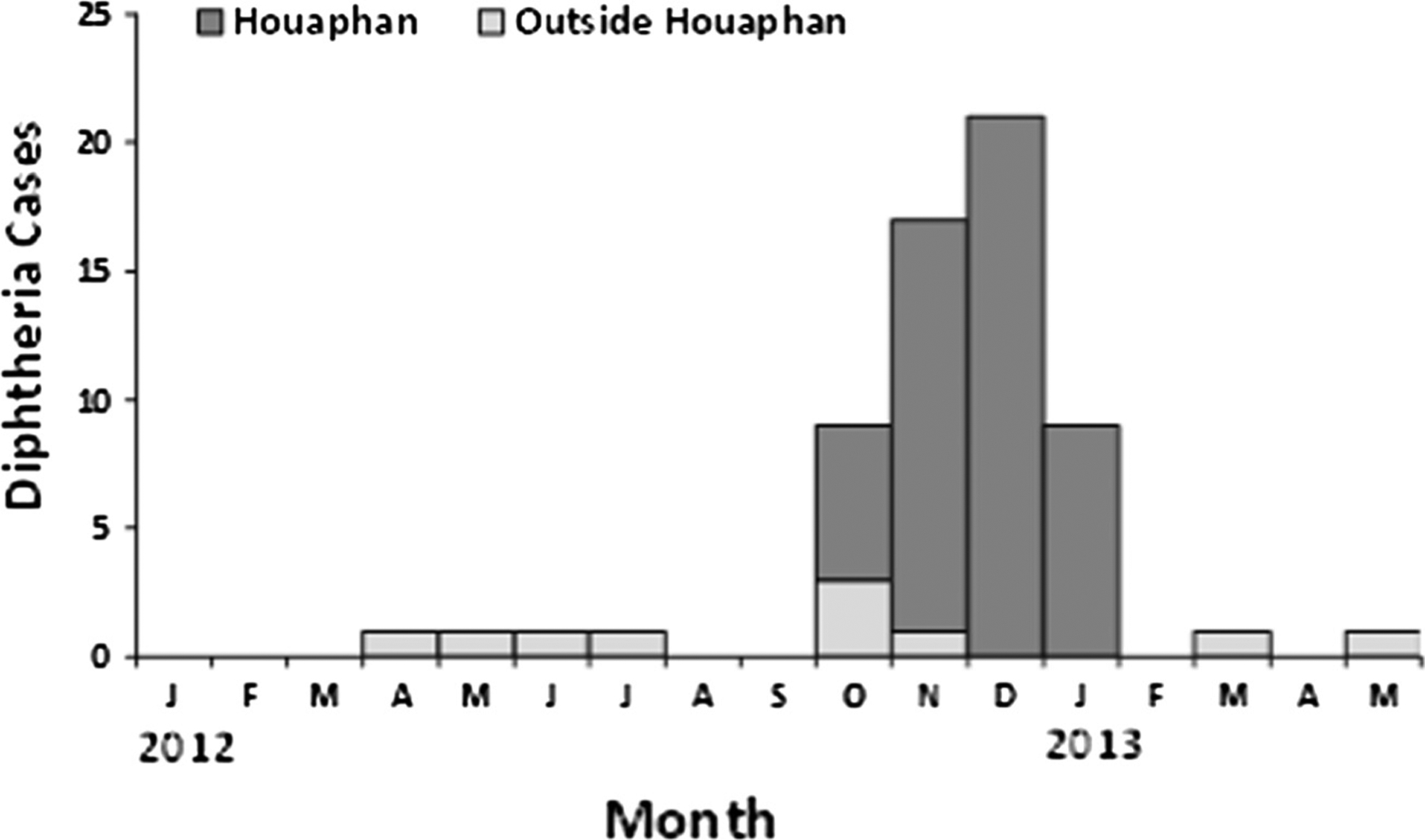

Clinical cases (those that met the clinical case definition) were reported from all seven provinces that reported suspected cases; the first from Vientiane capital on April 26, 2012, and the second, third and fourth clinical cases from Xiengkhouang, Bolikhamxay and Xayabuly provinces, respectively (Figs. 3 and 4). In the seven provinces reporting diphtheria during April 1, 2012–May 31, 2013, four were located in northern Lao PDR, and five reported <85% DTP3 coverage among young children aged 12–23 months, including Houaphan Province which had the lowest 2012 DTP3 coverage of 67% (Fig. 3). Among the 62 clinical cases, 52 (84%) were from Houaphan Province; the date of illness onset of the first case of diphtheria in Houaphan Province was October 9, 2012 and the number of reported confirmed diphtheria cases peaked in December 2012 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The number of reported confirmed diphtheria (N = 62) during April 1, 2012–May 31, 2013 and reported DTP3 administrative coverage (%) in 2012 by province – Lao People’s Democratic Republic.

Fig. 4.

Reported confirmed diphtheria cases (N = 62) within and outside Houaphan Province – Lao People’s Democratic Republic, April 1, 2012–May 31, 2013.

During the 14-month epidemic period (April 1, 2012–May 31, 2013) the number of reported diphtheria cases per 100,000 population was 0.8 nationally and 14.6 in Houaphan Province. The diphtheria CFR during the epidemic period was 19% nationally and 15% in Houaphan Province. Nationally, children <15 years of age accounted for 69% of clinical cases and 83% of diphtheria-related deaths. In Houaphan Province children <15 years of age accounted for 67% of clinical cases and 88% of diphtheria-related deaths.

Of the 62 clinical cases, the median age was 10.5 years (range: 3 months–43 years), and 43 (69%) were aged <15 years, 21 (34%) were unvaccinated, 35 (56%) had unknown vaccination status, and 38 (61%) were of Hmong ethnicity (Table 1). Among the 62 clinical cases, reports indicated that all patients had sore throat, 61 (98%) had fever, 56 (90%) had difficulty swallowing, 32 (52%) had difficulty breathing, and 12 (19%) died. Of the twelve deceased case-patients, eight (67%) were admitted for treatment with the median time between date of onset and admission of 3 days (range 2–23 days) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of diphtheria case-patients and deceased diphtheria case-patients – Lao People’s Democratic Republic, April 1, 2012–May 31, 2013.*

| Variable | Case-patients (n = 62) n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 31 (50) |

| Female | 31 (50) |

| Median age (years) | 10.5 (0.3–43.0) |

| Age group (years) | |

| <1 | 1 (2) |

| 1–4 | 6 (10) |

| 5–9 | 16 (26) |

| 10–14 | 20 (32) |

| 15–19 | 7 (11) |

| 20–24 | 5 (8) |

| ⩾25 | 7 (11) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hmong | 38 (61) |

| Laolum | 16 (26) |

| Khamou | 8 (13) |

| Symptoms | |

| Sore throat | 61 (98) |

| Fever | 56 (90) |

| Difficulty swallowing | 56 (90) |

| Difficulty breathing | 32 (52) |

| Number of DTP dose(s) | |

| 0 | 21 (34) |

| 1 | 1 (2) |

| 2 | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 5 (8) |

| Unknown | 35 (56) |

| Outcome | |

| Alive | 50 (81) |

| Deceased | 12 (19) |

| Variable | Deceased diphtheria case-patients (n = 12) n (%) |

| Median age (years) | 8.5 (0.1–16.0) |

| Age group (years) | |

| <1 | 1 (8) |

| 1–4 | 2 (17) |

| 5–9 | 6 (50) |

| 10–14 | 2 (17) |

| 15–16 | 2 (17) |

| Admitted for treatment | |

| Yes | 8 (67) |

| No | 4 (33) |

| Median time between date of onset and admission (days) | 3 (2–23) |

| Place of treatment | |

| City | 1 (8) |

| Province | 3 (25) |

| District | 2 (17) |

| Rural health facility | 1 (8) |

| Village | 3 (25) |

| Unknown | 2 (17) |

| Specimen collected | |

| Yes | 2 (17) |

| No | 10 (83) |

| Number of DTP dose(s) ** | |

| 0 | 3 (25) |

| 1 | 1 (8) |

| 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 3 (25) |

| Unknown | 5 (42) |

Data from the National Center for Laboratory and Epidemiology (NCLE), Lao PDR.

DTP = Diphtheria and Tetanus Toxoids and Pertussis vaccine.

At all health care facilities and villages visited, we observed that national treatment guidelines and DAT were not available. In addition, we observed that it was not standard practice for Tetanus and Diphtheria toxoids vaccine (Td) vaccine to be given as a booster dose to convalescing diphtheria patients.

For the case-control study, 52 clinical cases were identified in the NCLE database from Houaphan Province, among whom eight were deceased; study staff attempted to trace all 44 living case-patients and next-of-kin for those eight deceased, using contact information from the CIFs. In total, 42 (81%) case-patients were identified and contacted (including next-of-kin for all deceased case-patients) among 22 rural villages in the remote highlands of the province and were enrolled in the study. Of the ten (19%) case-patients not enrolled in the study, one had moved permanently to Vientiane, seven had moved temporarily for agricultural practices, and two resided in villages that were inaccessible because of the rainy season.

The 42 case-patients and 79 controls were similar in sex, fathers’ and mothers’ occupation, travel within two weeks and history of (non-specific) chronic skin condition/lesions which can be the manifestation of cutaneous diphtheria (Table 2). The median distance to a health facility was 14 km for both case-patients and controls (Table 2). Five (12%) case-patients and 20 (25%) controls reported receiving the primary course of three diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine doses, and 20 (48%) case-patients and 36 (46%) controls reported receiving no diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine. Multiple responses for non-vaccination were allowed; there were responses from 23 case-patients and 57 controls. The most frequently reported solicited reasons for non-vaccination chosen from the list of provided reasons were (1) child was not in the village at session time, (2) health care facility was too far, (3) child was unwell, and (4) guardians were unaware of the benefits of vaccination (Supplementary Table 1). Among those reporting non-vaccination, responses for 10 (43%) case-patients and 23 (40%) control individuals indicated lack of access to routine immunization services, and 13 (57%) case-patients and 34 (60%) controls missed opportunities for vaccination (Supplementary Table 1). No statistically significant risk factors were found; therefore multivariate analysis was not undertaken.

Table 2.

Characteristics among diphtheria cases and controls, case-control study, Houaphan Province – Lao People’s Democratic Republic, April 1, 2012–May 31, 2013.*

| Variable | Cases (n = 42) n (%)** | Controls (n = 79) n (%)** | Bivariate matched odds ratio (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 19 (45) | 38 (48) | Reference |

| Female | 23 (55) | 38 (48) | 0.91 (0.39–2.12) |

| Median age (years) | 12.0 (0.1–43.0) | 12.0 (0.5–45.0) | NA† |

| Age Group (years) | |||

| <1 | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | NA† |

| 1–4 | 3 (7) | 5 (6) | |

| 5–9 | 14 (33) | 26 (33) | |

| 10–14 | 15 (36) | 28 (35) | |

| 15–19 | 3 (7) | 6 (8) | |

| 20–24 | 2 (5) | 2 (3) | |

| ⩾25 | 4 (10) | 10 (13) | |

| Father’s occupation | |||

| Farmer | 38 (90) | 79 (100) | NA†† |

| Mother’s occupation | |||

| Farmer | 35 (83) | 77 (97) | 0.00 (0.00−∞ [infinity]) |

| Non farmer | 3 (7) | 2 (3) | Reference |

| Median distance to health facility (km) | 14.0 (0.0–28.0) | 13.8 (0.0–28.0) | |

| Number of children in household <5 years | |||

| ⩽2 | 26 (62) | 60 (76) | Reference |

| >2 | 11 (26) | 19 (24) | 1.43 (0.55–3.73) |

| Number in persons in household sharing same bed | |||

| ⩽4 | 23 (55) | 46 (58) | Reference |

| >4 | 15 (36) | 33 (42) | 0.39 (0.15–1.07) |

| Travel within 2 weeks | |||

| Yes | 2 (5) | 2 (3) | 2.72 (0.23–32.78) |

| No | 36 (86) | 76 (96) | Reference |

| Chronic skin condition/lesion | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA§ |

| No | 37 (88) | 79 (100) | |

| Number of DTP dose(s) §§ | |||

| 0 | 20 (48) | 36 (46) | Reference |

| 1 | 4 (10) | 14 (18) | 0.58 (0.15–2.29) |

| 2 | 6 (14) | 7 (9) | 1.64 (0.40–6.78) |

| 3 | 5 (12) | 20 (25) | 0.36 (0.08–1.66) |

Case control study conducted during 8–16 June, 2013.

Missing values not included in analysis: sex (3 controls); father’s and mother’s occupation (4 cases); number in household >5 (5 cases); number in household sharing same bed (4 cases), travel within 2 weeks (4 cases), knowledge of exposure (4 cases); chronic skin disease (5 cases); Sum of DTP doses (7 cases, 2 controls).

NA = not applicable; cases and controls were matched by age group.

NA = not applicable; all cases and controls had father’s occupation = farmer.

NA = not applicable; all cases and controls had chronic skin condition/lesion = negative (chronic skin condition/lesion defined as the presence of ulcer or scaling red rash with well demarcated edges for a period of ⩾ 1 month).

DTP = Diphtheria and Tetanus Toxoids and Pertussis vaccine; source of DTP vaccine information: recall 41/42 (98%) cases, 74/79 (94%) controls; vaccination card 1/42 (2%) cases, 5/79 (6%) controls.

4. Discussion

Following increased vaccination coverage in Lao PDR, and a period of low diphtheria incidence, a laboratory-confirmed diphtheria outbreak occurred with a cluster of cases of diphtheria reported in rural areas of Houaphan Province that had poor access to routine immunization services, with children <15 years of age accounting for the majority of clinical cases and diphtheria-related deaths.

During 2009–2012, Houaphan had reported DTP3 coverage of 44%, 63%, 71% and 67% respectively. Furthermore, in Houaphan Province, the case-control study found that only 14% of case-patients and 26% of controls had received the primary course of DTP3. Almost half of both case-patients and control participants received no diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine, and at least 40% of both case-patients and control participants reported poor access to immunization services. These findings suggest the cause of this outbreak was an accumulation of diphtheria-susceptible children who were either unvaccinated or had not received the full course of DTP3 due to poor access to immunization services.

Reported DTP3 coverage in Lao PDR increased from 53% in 2002 to 79% in 2012, and reached 87% and 88% during 2013 and 2014, respectively. However the Lao PDR National Social Indicator Survey (LSIS), estimated that DTP3 coverage among children aged 12–23 months during 2011–2012 was 37% by vaccination card and 52% by vaccination card or maternal recall [8]. This discrepancy suggests that the reported administrative coverage was likely over-estimated, possibly due to inaccuracies in population denominators based on projections from the 2005 census.

This investigation highlights challenges in delivery of routine immunizations in Lao PDR. Routine immunization services are provided at fixed sites at hospitals or health facilities to populations within a 5-km radius of the facility, or through mobile outreach whereby health workers travel to districts and villages to provide immunization services to the rest of the population. In the remote rural areas of Houaphan Province, routine immunization services are delivered primarily through outreach sessions; however, outreach is often not feasible during the annual rainy season from May to October each year. In 2012, a national EPI review estimated 70% of infants relied on outreach sessions for the delivery of their primary immunizations, and the EPI review team recommended increasing outreach sessions to 6 times per year [7]. The diphtheria outbreak suggests that reliance on outreach sessions to deliver routine immunization services might be insufficient.

A serosurvey for diphtheria and tetanus antibodies conducted in Houaphan Province, Lao PDR, during 2013, identified maternal education as a predictive factor for being vaccinated, and factors associated with non-vaccination were (1) distance from home to health center, (2) ethnicity (non Laolum), and (3) lack of vaccination education given to parents at the birth of a child [9]. The importance of community education, village leader engagement, and improving equity and access to services as protective factors have been previously identified by other studies in Lao PDR [10,11].

The high case fatality among reported cases of diphtheria in Lao PDR likely reflects reporting of more severe clinical cases, but also indicates the urgent need for improved case detection and management. Young children and unvaccinated persons have the highest risk of developing severe life-threatening diphtheria illness [2]. DAT is the treatment of choice for diphtheria and early administration is critical. Once toxin has entered host cells, it cannot be neutralized by antitoxin. To ensure early case detection and treatment, village volunteers and health workers should be sensitized to the importance of early treatment and a local DAT supply should be secured. National protocols and guidelines on case detection and treatment, including appropriate administration of DAT and antibiotics need to be available to health workers at all levels.

The average duration of protective immunity induced by the primary series of three-doses of diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine, is approximately ten years. Protective immunity can be boosted through exposure to circulating strains of toxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheria, however, naturally acquired partial protective immunity wanes with time [4]. Furthermore, diphtheria infection does not always confer protective immunity. Where natural boosting does not occur, booster doses of diphtheria toxoid beyond infancy and early school age are required [4].

Given the suboptimal DTP3 coverage in Lao PDR, the opportunity for a catch-up schedule as well as booster Diphtheria and Tetanus toxoids vaccine (DT) dose(s) could be provided during the second year of life. In keeping with the WHO recommendations, the opportunity for a Td booster dose should be offered to all those convalescing from diphtheria infection [12–14]. Furthermore, non-immune adults remain susceptible to diphtheria infection, and likely contribute to sustained transmission pathways within a community [4]. Periodic Td booster doses should therefore be offered to adults every ten years in Lao PDR, to sustain immunity as the risk for diphtheria infection remains high [4,14–16]. Currently in Lao PDR, Td booster doses are only offered to women of reproductive age for the prevention of maternal and neonatal tetanus.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of the study. The case-control study focused on a single province that reported the majority of case-patients. However, findings were based on a small number of reported cases, reducing the power of the study to identify risk factors. In addition, matching on neighborhood might have caused over-matching; for example, all children in one neighborhood might be missing vaccination history or have the same vaccination history, leading to the inability to find a significant association between disease and number of DTP doses. Also, many reported cases were missing vaccination status, and immunization card retention among case-patients and controls was considerably lower than 49% in the 2006 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) estimates, limiting analysis and introducing possible recall bias of DTP vaccination history [17]. Poor coverage among both case-patients and control participants limited the ability to demonstrate case-control differences, but highlights the need for improved service access and delivery.

In response to the outbreak in Lao PDR, a mass vaccination campaign using diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine targeting children 0–15 years of age was implemented in all eight northern provinces during March 4–15, 2013. Reported administrative coverage in the provinces ranged from 76% to 100% for Td (0–6 year olds); 89–100% for diphtheria and tetanus toxoids vaccine (DT) (7–15 year olds). The completion of three rounds of DTP immunization was recommended to rapidly increase population immunity against diphtheria.

The diphtheria outbreak in Lao PDR with its high case fatality ratio highlights the need to remain vigilant in strengthening surveillance and to develop and disseminate national guidelines to all levels to ensure prompt diagnosis and appropriate management, including access to timely DAT and appropriate boosting with Td for convalescing patients.

Outbreaks of any vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) such as this diphtheria outbreak in 2012, might serve as a red flag indicating gaps in population immunity due to insufficient routine immunization coverage. Indeed since 2012, Lao PDR has had outbreaks of VPDs including measles, diphtheria, tetanus, Japanese Encephalitis, and most recently during 2015–2016, vaccine-derived type 1 poliomyelitis; all due to low coverage with vaccines that are in the country’s routine infant immunization schedule [6].

The sustainable long-term solution for preventing both diphtheria and indeed other VPD outbreaks should focus on strengthening routine immunization services, including achieving the targets set in 2012 by the Global Vaccine Action Plan for DTP3 coverage of ⩾ 90% at national level and ⩾ 80% at district level by 2020 [18].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the dedication of the health workers, immunization officers, surveillance medical officers, and laboratory personnel in Lao PDR who are working toward the prevention of diphtheria and other vaccine-preventable diseases. We thank the outbreak investigation team for the field work conducted during the case-control study, Dr Kimberley Fox, and the WHO Western Pacific Regional office for their guidance and support. Lastly, a very special thanks to Dr William Schluter for his unparalleled commitment to providing exemplary technical assistance.

Funding source

Funding for this study was provided by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the World Health Organization or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disclosure by authors

All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Financial interest

The authors do not have a financial or proprietary interest in a product, method, or material or lack thereof.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.074.

References

- [1].Farizo KM et al. Fatal respiratory disease due to Corynebacterium diphtheriae: case report and review of guidelines for management, investigation, and control. Clin Infect Dis 1993;16(1):59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Vidor E, Plotkin SA. In: Plotkin S, Orenstein WA, Offitt PA, editors. Vaccine: poliovirus vaccine – inactivated. HongKong, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2013. p. 573–9 [China]. [Google Scholar]

- [3].World Health Organization Immunization Vaccines and Biologicals. The immunological basis for immunization series module 2: Diphtheria Update; 2009. Available from: <http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597869_eng.pdf> [Accessed 20 April 2015].

- [4].World Health Organization 2006. Position paper on diphtheria. Available from: <http://www.who.int/wer/2006/wer8103.pdf?ua=1> [Accessed 14 April 2015].

- [5].Wheeler BS. New trends in diphtheria research. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [6].WHO Diphtheria reported cases. Available from: <http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/timeseries/tsincidencediphtheria.html>. [Accessed 5 June 2016].

- [7].International Review of the Expanded Programme on Immunization WHO Western Pacific Region in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, May 2012. Available from: <http://www.wpro.who.int/immunization/documents/Intl_Review_of_EPI_in_Lao.pdf>. [Accessed 14 April 2015].

- [8].Lao PDR Social Indicator Survey (LSIS) 2011–12. Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey/Demographic and Health Survey. Available from: <http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR268/FR268.pdf>. [Accessed 14 April 2015].

- [9].Nanthavong N et al. Diphtheria in Lao PDR: insufficient coverage or ineffective vaccine? PLoS ONE 2015;10(4):e0121749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kitamura T et al. Factors affecting childhood immunization in Lao People’s Democratic Republic: a cross-sectional study from nationwide, population-based, multistage cluster sampling. Biosci Trends 2013;7(4):178–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Phimmasane M et al. Factors affecting compliance with measles vaccination in Lao PDR. Vaccine 2010;28(41):6723–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Galazka AM, Robertson SE. Diphtheria: changing patterns in the developing world and the industrialized world. Eur J Epidemiol 1995;11(1):107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Galazka A The changing epidemiology of diphtheria in the vaccine era. J Infect Dis 2000;181(Suppl. 1):S2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dittmann S et al. Successful control of epidemic diphtheria in the states of the Former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics: lessons learned. J Infect Dis 2000;181(Suppl. 1):S10–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sutter RW et al. Immunogenicity of tetanus-diphtheria toxoids (Td) among Ukrainian adults: implications for diphtheria control in the Newly Independent States of the Former Soviet Union. J Infect Dis 2000;181(Suppl 1):S197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Vitek CR et al. Risk of diphtheria among schoolchildren in the Russian Federation in relation to time since last vaccination. Lancet 1999;353 (9150):355–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2006: Lao PDR. Available from: <http://www.childinfo.org/files/MICS3_Lao_FinalReport_2006_Eng.pdf> [Accessed 14 April 2015].

- [18].Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011–2020. Available from: <http://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/> [Accessed 20 April 2015].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.