Abstract

Objective:

Stressors and worries related to the COVID-19 pandemic have contributed to the onset and exacerbation of psychological symptoms such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Using a micro-longitudinal framework, we uniquely investigated bidirectional associations between daily-level PTSD symptoms and COVID-19 worries.

Method:

Data from 42 trauma-exposed university students (Mage=22.67 ± 5.02, 86.7% female) were collected between March-August 2020. Participants completed daily surveys for 10 days to assess PTSD symptom severity and COVID-19 worries. Multilevel regression was conducted to examine both lagged and simultaneous models of daily person-centered mean PTSD symptom severity predicting COVID-19 worries, and vice-versa.

Results:

Days with greater COVID-19 worries were associated with greater same-day (b=.53, SE=.19, p=.006) and next-day (b=.65, SE=.21, p=.003) PTSD symptom severity. Additionally, days with greater PTSD symptom severity were associated with greater same-day COVID-19 worries (b=.06, SE=.02, p=.006).

Conclusions:

COVID-19 worries may influence same-day and next-day PTSD symptoms, and PTSD symptoms may influence same day COVID-19 worries. Findings substantiate the interplay between on-going stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic and posttrauma symptoms, and support therapeutically targeting COVID-19 stress in PTSD treatments to potentially impact posttrauma symptoms.

Keywords: COVID-19 worries, trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, multilevel models

1. Introduction

Most adults in the United States (U.S.; ~90%) experience a potentially traumatic event (PTE) in their lifetime (Kilpatrick et al., 2013). Approximately ~8% of these individuals report clinical levels of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Kilpatrick et al., 2013). PTSD, defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5), is represented by four symptom clusters: intrusions, persistent avoidance of internal and external trauma reminders, negative alterations in cognitions and mood (NACM), and alterations in arousal and reactivity (AAR; American Psychiatric Association & Association, 2013). Individuals with PTSD symptoms are susceptible to experiencing more PTEs (Kilpatrick et al., 2013), daily stressors (Larsen & Pacella, 2016), and psychological and physical health comorbidities (Fox et al., 2020). Thus, there is a need to better understand factors that may influence PTSD symptoms, such as psychological effects of the recent Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

In December 2019, an outbreak of the novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (COVID-19) was reported in Wuhan, China. By March 11, 2020 the outbreak had spread to over 100 countries and was classified as a pandemic by the World Health Organization. The U.S. declared a national emergency and implemented social distancing and stay-at-home protocols on March 13, 2020 to halt the spread of COVID-19. This prompted widespread closures of schools, college campuses, and businesses, impacting individuals’ psychological health by increasing emotional distress, anxiety, and psychiatric illness in the general population (Hsing et al., 2020; Pfefferbaum & North, 2020; Rosen et al., 2020; Serafini et al., 2020). Consistent with other pandemic estimates (e.g., Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in 2003 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome in 2012; Cheng et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2009), several studies have indicated concerning estimates of PTSD prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diagnostic PTSD prevalence estimates range from 10%-17.7%, and the presence of clinically significant (or elevated) symptoms as determined by empirically validated PTSD measures range from 29.5%-33.2% across diverse samples from the U.S. (C. H. Liu et al., 2020), United Kingdom (Shevlin et al., 2020), Italy (Forte et al., 2020), India (Varshney et al., 2020), and China (N. Liu et al., 2020). Among healthcare workers, diagnostic PTSD prevalence estimates (8-30%) during COVID-19 have historically been higher than those in the general population (Carmassi et al., 2020).

Relevant to the current study, a question worth investigating is the nature and directionality of associations between PTSD symptoms and COVID-19 worries. One line of research suggests that PTSD symptoms may develop or worsen during the COVID-19 pandemic and following COVID-19 stress or worries (Dutheil et al., 2020). Indeed, evidence suggests more exposure to PTEs during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may contribute to the onset or exacerbation of PTSD symptoms. Relevant PTE examples include life-threatening illnesses (Carmassi et al., 2020), sudden unexpected death of loved ones (Kaltman & Bonanno, 2003), medical traumas from surgical or emergency procedures in those infected with COVID-19 (Griffiths et al., 2007), and physical or sexual abuse and violence due to living in forced quarantine conditions with an abuser (Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020). Furthermore, impacts of these PTEs on PTSD symptoms may be exacerbated by COVID-19 stressors, worries, and risk factors such as experienced feelings of vulnerability (Carmassi et al., 2020); occupational roles that increase COVID-19 exposure risk (Lai et al., 2020); reduced social support, greater social isolation, and stigma of seeking help due to quarantine protocols (González-Sanguino et al., 2020; C. H. Liu et al., 2020); disrupted use of existing coping mechanisms (i.e., reduced help-seeking behaviors and effective problem solving; Dempsey et al., 2000); and less reliable access to treatment (Chan & Huak, 2004).

Another line of research indicates that pre-existing PTSD symptoms may contribute to COVID-19 worries. Negative cognitive appraisals of oneself, others, and the world are central to PTSD’s symptomatology (Brown et al., 2019), and may negatively bias one’s perceptions of COVID-19 events promoting stress and worries (Tsur & Abu-Raiya, 2020). Furthermore, drawing on the theoretical framework of the predatory imminence theory (Brown et al., 2019), PTSD symptoms may lower the threshold for fear-based reactions to COVID-19 stressors and increase the likelihood that exposure to these stressors might provoke adverse posttraumatic reactions (Tsur & Abu-Raiya, 2020). Alternatively, emotion dysregulation as related to PTSD symptoms (Weiss et al., 2013) may disrupt effective coping with COVID-19 anxieties and worries. For example, experienced emotion dysregulation may prevent individuals from learning corrective information about coping with their fears (Raudales et al., 2020), ultimately leading to greater COVID-19 distress. Lastly, individuals with PTSD report psychological symptoms such as substance use (Weiss et al., 2012), anxiety (van Minnen et al., 2015), and depression (van Minnen et al., 2015), coupled with reduced social support and mental health treatment (Stecker et al., 2013). These individuals may also experience other medical conditions (e.g., insomnia, cardiovascular disease) that render them more susceptible to contracting COVID-19. All such factors may exacerbate COVID-19 anxieties and worries (Serafini et al., 2020).

Critical limitations in the existing literature prompted the current study. First, most existing COVID-19 research has been cross-sectional (Carmassi et al., 2020; Dutheil et al., 2020; Gallagher et al., 2021; González-Sanguino et al., 2020), which prevents examining directionality of impacts. Second, among COVID-19 studies using a longitudinal framework (Duan & Zhu, 2020; Wang et al., 2020), most have used aggregated single-score estimates, which fail to account for symptom variability across days, and conflate relationships among data at the upper (between-person) and lower (within-person) level of analyses. Third, most COVID-19 studies have relied on retrospective recollections of symptoms or behaviors that are subject to recall bias. This is particularly problematic when collecting data on PTSD symptoms, as PTSD is characterized by memory encoding- and retrieval-based disturbances (Brewin et al., 2009). Fourth, no study to our knowledge has attempted to clarify the directionality of associations between daily-level PTSD symptoms and COVID-19 worries, which may elucidate which treatment options should be prioritized. Addressing these research gaps, we used a micro-longitudinal study design (i.e., repeated measures over several days) to examine associations between COVID-19 worries and PTSD symptoms recorded daily for 10 days in a sample of trauma-exposed students. Drawing from existing research (e.g., Carmassi et al., 2020; Dutheil et al., 2020), we hypothesized that (1) days with greater COVID-19 worries would be associated with greater next-day PTSD symptom severity; (2) days with greater PTSD symptom severity would be associated with greater next-day COVID-19 worries; and (3) days with greater PTSD symptom severity would be associated with greater same-day COVID-19 worries (and vice versa).

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the University of North Texas Institutional Review Board (IRB). Participants were recruited online through the university undergraduate psychology pool, as well as through flyers posted in campus buildings and classroom announcements from January 2019 to August 2020. The larger parent study was not originally designed to examine the impact of the pandemic; mid-way during the parent study (March 17, 2020), we added COVID-19 measures with IRB approval. All study surveys were completed online using Qualtrics. The larger study included three phases: a baseline phase, a micro-longitudinal phase, and a follow-up phase; we describe the baseline and micro-longitudinal phases relevant to the current analyses.

Baseline Phase.

Interested participants provided informed consent and contact information for study purposes and received a randomly generated Participant Identification (ID) number. On a different survey, participants responded to eligibility questions (≥18 years; endorsing a traumatic event assessed by the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5; [Prins et al., 2016]; ability to speak, write, and read in English; and owning a mobile phone) and questions assessing demographics, psychological symptoms, and affect and cognitive processes. This survey had three embedded validity checks to ensure attention and comprehension (Thomas & Clifford, 2017). Eligible and consenting participants who passed all validity checks were invited to enroll into the next phases of the study and received four course credits.

Micro-Longitudinal Phase.

Participants received one daily survey for 10 days. The gap between the Baseline Phase survey and the 1st daily survey averaged 1.56 days. Research assistants sent text messages with survey links daily at 5 p.m. to complete the survey between 7-10 p.m. that day; research assistants sent reminder texts or emails at 9 p.m. Participants received a $1.50 gift card for every completed daily survey (maximum total of $15); those who completed a minimum of eight daily surveys entirely received an additional $5 gift card.

2.2. Participants, Exclusions, and Missing Data

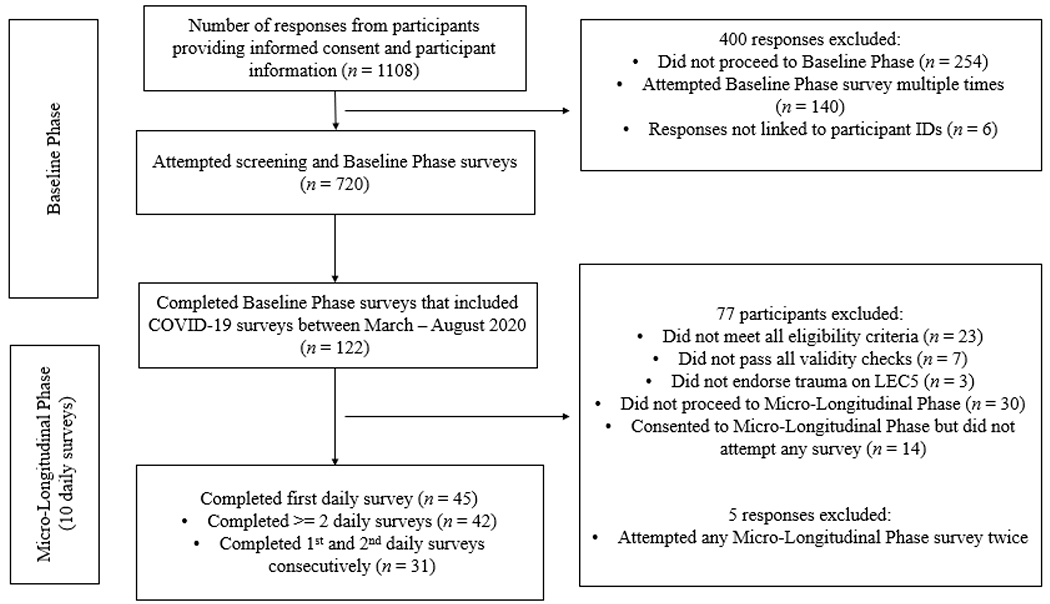

See Figure 1 for the procedural diagram and participant exclusions. The parent study received a total of 1,108 responses from potential participants who provided informed consent and participant information. Our final sample included 42 participants as indicated in Figure 1. The substantial truncation of the data is because the COVID-19 measures were added mid-way during the parent study (March 17, 2020) given the onset and worsening of the pandemic; we excluded 598 participants who were not administered the COVID-19 surveys. Thus, the timeline of the data collected for this study was between March-August 2020, which includes the period in which the United States government had issued a state-wide lockdown for two weeks affecting universities transitioning to online instruction. In this final sample of 42 participants who completed the 1st daily survey and ≥ two daily surveys in total in the Micro-Longitudinal Phase, individuals averaged 6.51 completed surveys (SD = 3.30) out of 10 possible surveys. The final sample of 42 individuals reported an average age of 22.59 years (SD = 4.75); 36 participants (85.7%) identified as women. Detailed demographic information is provided in Table 1 and information on trauma types is provided in Supplemental Table 1. As a post-hoc sensitivity analysis, we examined our a priori hypotheses in a subsample of 31 individuals who averaged 8.03 completed surveys (SD = 2.51) to see if results held among individuals with higher levels of compliance.

Figure 1.

Procedural Diagram and Participant Exclusions.

Note: LEC-5 represents the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5. “Five responses excluded” represents the number of daily surveys that were removed from the Micro-Longitudinal Phase due to a participant attempting a given daily survey twice on the same day. We compared participants who completed the Baseline Phase with COVID-19 measures and did not proceed to the Micro-Longitudinal Phase (n = 44) vs. participants who completed the Baseline Phase with COVID-19 measures and the first daily survey (n = 45); results revealed no differences across groups on demographic variables and baseline PTSD symptom severity. The group comparisons were: age, t(84) = 0.09, p = .929; gender (woman; not woman), χ2(1) = 0.06, p = .804; race (white; non-white), χ2(1) = 1.20, p = .274; education (some college; no college), χ2(1) = 0.06, p = .811; employment status (employed [full- or part-time]; not employed), χ2(1) = 0.15, p = .696; income (<$45,000; ≥ $45,000), χ2(1) = 0.55, p = .460; relationship status (single; not single [dating; married]), χ2(1) = 0.54, p = .461; and baseline PTSD symptom severity, t(82) = −0.86, p = .389.

Table 1.

Information on demographics

| N = 42 | N = 31 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | |

| Age | 22.59 (4.75) | 22.67 (4.94) | ||

| Number of Daily Surveys Completed | 6.51 (3.30) | 8.03 (2.51) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 3 (7.1) | 2 (6.5) | ||

| Female | 36 (85.7) | 26 (83.9) | ||

| Woman to Man (FTM) Transgender | 1 (2.4) | 1 (3.2) | ||

| Genderqueer/nonbinary | 1 (2.4) | 1 (3.2) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 5 (11.9) | 4 (12.9) | ||

| White | 28 (66.7) | 24 (77.4) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (4.8) | 2 (6.4) | ||

| Asian | 4 (9.5) | 3 (9.7) | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 2 (4.8) | 1 (3.2) | ||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 14 (33.3) | 6 (19.4) | ||

| Other | 1 (2.4) | 0 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Completed K-12 | 4 (9.5) | 4 (12.9) | ||

| Completed 1-4 Years Post-Secondary | 36 (85.7) | 26 (83.9) | ||

| Completed 5+ Years Post-Secondary | 2 (4.8) | 1 (3.2) | ||

| Employment Status | ||||

| Full Time | 10 (23.8) | 7 (22.6) | ||

| Part Time | 12 (28.6) | 9 (29.0) | ||

| Unemployed | 7 (16.7) | 4 (12.9) | ||

| Not in Labor Force | 13 (31.0) | 11 (35.5) | ||

| Income | ||||

| < $15,000 | 8 (21.6) | 4 (14.8) | ||

| $15,000-$44,999 | 15 (40.5) | 11 (40.7) | ||

| $45,000-$79,999 | 6 (16.2) | 4 (14.8) | ||

| > $80,000 | 8 (21.6) | 8 (29.6) | ||

| Relationship Status | ||||

| Single | 13 (31.0) | 10 (32.3) | ||

| Dating | 26 (61.9) | 19 (61.3) | ||

| Married | 3 (7.1) | 2 (6.5) | ||

| Know Someone Tested for COVID-19 | 28 (66.7) | 18 (58.1) | ||

| Behavior Has Changed Since COVID-19 | 38 (90.4) | 25 (80.6) | ||

Note. M (SD) represents mean and standard deviation; n/% represents number of individuals or percentage. N=42 represents the final sample of 42 participants who averaged 6.51 completed surveys (SD = 3.30) out of 10 possible surveys. N=31 represents a subsample of 31 individuals who averaged 8.03 completed surveys (SD = 2.51) out of 10 possible surveys.

2.3. Measures

Demographic Information.

Participants reported their age, gender, racial or ethnic background, religion, educational level, employment status, income level, and relationship status.

Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5).

Administered at the Baseline Phase, the 17-item self-report LEC-5 (Weathers, Blake, et al., 2013) was used to assess experiences of lifetime PTEs. Sixteen LEC-5 items query specific potentially traumatic events, and the 17th item queries for any additional stressful event. An 18th item examined the most distressing PTE. Endorsing any of the first four response options (i.e., happening to them, witnessing it, learning about it, or as part of their job) on items 1-16 was considered a positive trauma endorsement.

PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5).

Administered at all study phases, the PCL-5 (Weathers, Litz, et al., 2013) is a 20-item self-report measure of PTSD symptom severity using a 5-point Likert scale (0 [“Not All All”] to 4 [“Extremely”]). Total summed scores range from 0-80. Participants referenced time since the previous daily survey in the Micro-Longitudinal Phase; and the past month in the Baseline Phase. Participants were asked to index the most distressing PTE endorsed on the LEC-5 when completing the PCL-5. The PCL-5 yields sound psychometric properties (Bovin et al., 2016); the scale demonstrated good internal consistency across days (α ranged .91 - .95) in the current study.

COVID-19 Experiences and Exposures Scale.

Administered at the Baseline Phase, the COVID-19 Experiences and Exposures Scale (Freedman et al., 2020) is a 7-item self-report questionnaire examining participant’s general awareness of and exposure to COVID-19. Two items from this scale, which were predicted to most likely influence associations between PTSD symptom severity and COVID-19 worries (Bridgland et al., 2021), were included in the current study as covariates: ‘Do you know people who have been tested for the COVID-19 virus?’ (Q1) and ‘Since learning about or hearing about COVID-19 have you changed your behavior?’ (Q2). The two items were categorically coded as “Yes”, “No”, or “Don’t Know.”

COVID-19 Worries Scale.

At all study phases, a preliminary version of the COVID-19 Worries Scale (Freedman et al., 2020) was administered, which was an 8-item self-report measure of perceived worries related to the COVID-19 pandemic impacting various aspects of daily life (e.g., worries about being exposed to COVID-19, quarantine-related worries). Examples of items included: “Are you worried about being infected?”, “Are you worried about your job or academic security if the situation worsens?”, and “Are you worried about the ability of health systems to care for COVID-19 patients if the situation worsens?” Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Very Little”) to 5 (“Very Much”). In the current study, we used a summed score of all 8-items; total summed scores range from 0-40. In this study, the scale demonstrated good internal consistency across days (a ranged .86-,93), and item-level intercorrelations ranged between .43 and .63.

2.4. Data Analytical Plan

Analyses were conducted in the statistical program R (R Core Team, 2013) provided in Supplemental Document 1. Multilevel models were conducted using the R package nlme (Pinheiro et al., 2017). For all multilevel models, level 1 days were nested within level 2 individuals. All level 1 repeated measures independent variables were person-mean centered (PMC) so that values represented deviations from an individual’s average taken across all 10 days. Restricted maximum likelihood (REML) was used, which is a robust method for handling missing data using all available information to estimate the model (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Given the smaller sample size (N = 42), intercepts were allowed to vary randomly across individuals, but slopes were fixed as models with random slopes were not identified. All models covaried for gender (0 = male, 1 = female), COVID-19 exposure Q1 (0 = No, 1 = Yes), and COVID-19 exposure Q2 (0 = No, 1 = Yes), unless otherwise noted, given previous studies showing robust differences in PTSD symptom severity by gender and COVID-19 exposure (Lai et al., 2020). No participants endorsed “Don’t know” as a response for the two COVID-19 exposure questions; thus, this response category was not considered in the analyses. For analyses examining daily PTSD symptoms predicting subsequent COVID-19 worries, PTSD symptom severity was lagged back one day (reflecting PTSD symptom severity the previous day). For analyses examining daily COVID-19 worries predicting subsequent PTSD symptom severity, COVID-19 worries were lagged back one day (reflecting COVID-19 symptoms the previous day). An example equation for daily PTSD symptom severity (Daily PTSD; reported the previous day) predicting the random intercept of next-day COVID-19 worries (controlling for two COVID-19 exposure questions and gender) is displayed below:

where: β0j is the within-person intercept of daily COVID-19 Worries, modeled as a function of the grand mean for daily COVID-19 worries when all other predictors equal 0 (γ00), the overall effect of gender on daily COVID-19 Worries (γ01), the overall effect of COVID-19 exposure Q1 on daily COVID-19 Worries (γ02), the overall effect of COVID-19 exposure Q2 on daily COVID-19 Worries (γ03), and a person-level residual from the grand mean (u0j); and β1j is the within-person slope between daily PTSD symptom severity and COVID-19 Worries, modeled as a function of an overall slope (γ10). As supplemental analyses, we tested study hypotheses regarding lagged associations in a subsample (N = 31) that had greater survey compliance.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive results

Primary variable residuals were normally distributed across all models. Participants reported average PTSD symptom severity of 32.62 (SD = 17.12) at baseline; 20 participants (47.6%) met the threshold for probable PTSD based on a PCL-5 score of ≥ 33 (Blevins et al., 2015). Average baseline scores for the PTSD symptom clusters were as follows: 8.22 (SD = 4.95; max score = 20) for intrusions cluster; 3.88 (SD = 2.72; max score = 8) for avoidance cluster; 11.90 (SD = 7.17; max score = 28) for NACM cluster; and 8.88 (SD = 5.03; max score = 24) for AAR cluster. Further, participants reported daily PTSD symptom severity averaging 18.18 (SD = 15.54; subthreshold range). Average daily scores for the PTSD symptom clusters were as follows: 3.95 (SD = 4.02) for intrusions cluster; 2.13 (SD = 2.08) for avoidance cluster; 6.88 (SD = 6.11) for NACM cluster; and 5.39 (SD = 4.42) for AAR cluster. Finally, participants reported daily COVID-19 worries averaging 23.49 (SD = 7.95). For the repeated measures variables, the intraclass correlation coefficients (i.e., percentage of variance at the between-person level, compared to the total variance [i.e., between-person variance plus within-person variance]) were 79% for daily total PTSD symptom severity, 65% for daily intrusions cluster, 60% for daily avoidance cluster, 77% for daily NACM cluster, 76% for daily AAR cluster, and 90% for daily COVID-19 worries. The intraclass correlation coefficients suggest between 10-40% of variation in these constructs is due to day-to-day fluctuations, which may be obscured by low mean values across the 10 days. Average between-person daily PTSD symptom severity was weakly correlated with average between-person COVID-19 worries (Pearson’s r = 0.18).

3.2. Lagged Associations

Results for the full sample (N = 42) and subsample with higher compliance (N = 31) are presented in Table 2 and Supplemental Table 2, respectively. In the full sample, days with greater COVID-19 worries than an individual’s average were associated with greater PTSD symptom severity the next day (b = 0.65, SE = 0.21, p = .003). Specifically, every one-unit increase in the COVID-19 Worries Scale total score was associated with a .65 increase in the PCL-5 total score. Similarly, in the subsample, days with greater COVID-19 worries than an individual’s average were associated with greater PTSD symptom severity the next day (b = 0.66, SE = 0.22, p = .003). However, in the full sample and subsample, daily PTSD symptom severity was not associated with next-day COVID-19 worries.

Table 2.

Lagged associations between daily PTSD symptom severity and daily COVID-19 worries (N = 42)

| Next-Day COVID-19 Worries | Next-Day PTSD Symptom Severity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | b | 95% CI | P | Predictors | b | 95% CI | P |

|

| |||||||

| (Intercept) | 22.10 | 9.57 – 34.63 | 0.001 | (Intercept) | 25.28 | 2.81 – 47.74 | 0.028 |

| Daily PTSD symptom severity | −0.05 | −0.10 – 0.00 | 0.052 | Daily COVID-19 worries | 0.65 | 0.23 – 1.07 | 0.003 |

| Know someone tested for COVID-19 | −0.26 | −6.48 – 5.96 | 0.932 | Know someone tested for COVID-19 | 6.82 | −4.35 – 17.99 | 0.222 |

| Behavior has changed since COVID-19 | 3.33 | −5.41 – 12.06 | 0.444 | Behavior has changed since COVID-19 | −10.37 | −25.95 – 5.20 | 0.184 |

| Female | −1.12 | −10.03 – 7.79 | 0.800 | Female | −4.32 | −20.41 – 11.77 | 0.588 |

| Random Effects | Random Effects | ||||||

| σ2 | 6.24 | σ2 | 51.47 | ||||

| T00 ID | 76.11 | T00 ID | 237.28 | ||||

| N ID | 36 | N ID | 36 | ||||

| Observations | 211 | Observations | 211 | ||||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.25 / NA | Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.37 / NA | ||||

Note. Daily PTSD symptom severity represents daily posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity as measured by the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) total score; Daily COVID-19 worries represent daily Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 worries as measured by the COVID-19 Worries Scale total score; b is the unstandardized regression weight; and 95% CI represents 95% confidence intervals. Bold values represent significant effects, σ2 is the level 1 variance; T00 ID is the level 2 variance; N ID is the number of level 2 observations (people); Observations is number of level 1 observations (days); Marginal R2 is the variance of the fixed effects only; Conditional R2 is the variance of the fixed and random effects.

3.3. Simultaneous Associations

Table 3 includes results for daily PTSD symptom severity predicting same-day COVID-19 worries, and daily COVID-19 worries predicting same-day PTSD symptom severity (N = 42). Days with greater PTSD symptom severity than an individual’s average were associated with greater COVID-19 worries the same day (b = 0.06, SE = 0.02, p = .006). Additionally, days with greater COVID-19 worries than an individual’s average were associated with greater PTSD symptom severity the same day (b = 0.53, SE = 0.19, p = .006). Every one-unit increase in the PCL-5 total score was associated with a .06 increase in the COVID-19 Worries Scale total score, and every one-unit increase in the COVID-19 Worries Scale total score was associated with a .53 increase in the PCL-5 total score.

Table 3.

Simultaneous associations between daily PTSD and daily COVID-19 Worries (N = 42)

| Daily COVID-19 Worries | Daily PTSD Symptom Severity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | b | 95% CI | P | Predictors | b | 95% CI | P |

|

| |||||||

| (Intercept) | 21.6 | 10.17 – 33.03 | <0.001 | (Intercept) | 24.08 | 2.10 – 46.06 | 0.032 |

| Daily PTSD symptom severity | 0.06 | 0.02 – 0.10 | 0.006 | Daily COVID-19 worries | 0.53 | 0.15 – 0.90 | 0.006 |

| Know someone tested for COVID-19 | −1.04 | −6.49 – 4.41 | 0.702 | Know someone tested for COVID-19 | 3.5 | −7.01 – 14.01 | 0.504 |

| Behavior has changed since COVID-19 | 3.23 | −4.77 – 11.24 | 0.419 | Behavior has changed since COVID-19 | −8.61 | −23.96 – 6.74 | 0.263 |

| Female | −0.07 | −8.17 – 8.04 | 0.986 | Female | −0.73 | −16.37 – 14.91 | 0.925 |

| Random Effects | Random Effects | ||||||

| σ2 | 6.81 | σ2 | 58.93 | ||||

| T00 ID | 66.32 | T00 ID | 239.6 | ||||

| N ID | 41 | N ID | 41 | ||||

| Observations | 273 | Observations | 273 | ||||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.22 / NA | Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.20 / NA | ||||

Note. Daily PTSD symptom severity represents daily posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity as measured by the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) total score; Daily COVID-19 worries represent daily Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 worries as measured by the COVID-19 Worries Scale total score; b is the unstandardized regression weight; and 95% CI represents 95% confidence intervals. Bold values represent significant effects, σ2 is the level 1 variance; T00 ID is the level 2 variance; N ID is the number of level 2 observations (people); Observations is number of level 1 observations (days); Marginal R2 is the variance of the fixed effects only; Conditional R2 is the variance of the fixed and random effects.

4. Discussion

We examined bidirectional associations (lagged and simultaneous) between daily PTSD symptom severity and COVID-19 worries in a trauma-exposed student sample. Consistent with study hypotheses, we found that greater COVID-19 worries were associated with greater next-day and same-day PTSD symptom severity. These findings corroborate research suggesting PTSD symptom severity may develop or worsen following stressful or traumatic experiences and worries related to the COVID-19 pandemic (Carmassi et al., 2020; Dutheil et al., 2020; Gallagher et al., 2021). These findings also support cross-sectional findings of several studies showing that COVID-19-related distress is associated with PTSD symptoms (Carmassi et al., 2020; Dutheil et al., 2020; González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Tsur & Abu-Raiya, 2020); similar associations have been noted in other previous acute respiratory virus outbreaks (Wu et al., 2009). COVID-19 worries, such as thoughts of uncertainty and vulnerability (Carmassi et al., 2020), fears of contracting COVID-19 and of losing loved ones due to COVID-19 (Carmassi et al., 2020; Kaltman & Bonanno, 2003), as well as anxieties related to being in lockdown and restricted accessibility to supplies (Bridgland et al., 2021) combined with disrupted coping mechanisms (Chan & Huak, 2004; Dempsey et al., 2000; C. H. Liu et al., 2020) may influence greater PTSD symptoms. Further, daily worries about the pandemic may become a stressor itself, and thus, exacerbate PTSD symptom severity. Indeed, research supports that daily stressors (beyond traumatic events) exacerbate PTSD symptoms (Larsen & Pacella, 2016). Additionally, disruptions in social support networks due to mandated social distancing and lack of proximity and access to family and friends in the context of COVID-19 may add to anxieties and worries, which in turn, may contribute to PTSD symptoms (Galea et al., 2020).

When examining pathways from daily PTSD symptom severity to next-day COVID-19 worries, we found non-significant results, inconsistent with study hypotheses. Notably, this particular pathway is understudied. One study by Tsur & Abu-Raiya (2020) examined this pathway and observed an association between PTSD symptoms and COVID-19 worries; however, this study was cross-sectional and unable to ascertain the temporal order of associations. Perhaps, health correlates of PTSD, such as risky behaviors (Weiss et al., 2012) and daily stressors (van Minnen et al., 2015), especially in the context of mitigation procedures during the pandemic (Galea et al., 2020), may influence associations between PTSD symptoms and next-day COVID-19 worries. In this regard, future research needs to identify factors beyond PTSD symptoms that may influence daily fluctuations in COVID-19 worries, such as daily or weekly updates on lockdown, COVID-19 cases, deaths, and hospital occupancies (Ko et al., 2020; Merchant et al., 2020). Alternatively, in the current study, we examined the influence of PTSD symptoms on COVID-19 worries at the daily level; however, PTSD symptoms may exhibit a greater degree of influence on COVID-19 worries when looking at a different time scale (e.g., week-to-week or month-to-month). Finally, study findings may be attributed to a small sample size, or the nature of our non-clinical sample.

In contrast to lagged associations, same-day PTSD symptom severity had a small positive association with same-day COVID-19 worries, consistent with existing cross-sectional findings (Carmassi et al., 2020; Dutheil et al., 2020; González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Tsur & Abu-Raiya, 2020). It may be that, in real-time and within the same day timeframe, the experience of PTSD symptoms may negatively bias one’s perceptions of COVID-19 events and lower the threshold for fear-based reactions to COVID-19 stressors; such processes may promote worries and increase the likelihood that exposure to these stressors might provoke adverse posttraumatic reactions (Tsur & Abu-Raiya, 2020). Alternatively, effective coping with COVID-19 anxieties and worries may be temporarily disrupted by emotion dysregulation, arousal, and cognitive biases related to PTSD symptoms (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Weiss et al., 2013), ultimately leading to greater momentary COVID-19 distress.

4.1. Implications and Study Limitations

Study results inform theory and clinical practice. First, study findings of between and within-person variability for daily PTSD symptom severity map onto other reported findings (Ruggero et al., 2021). While PTSD symptom severity is largely driven by between-person differences rather than within-person changes across days, there is still significant daily within-person variability across days. Study results are critical because they suggest that daily PTSD symptoms may be malleable or transitionary, and that PTSD maintenance and chronicity can be influenced by external psychosocial factors such as fluctuations in COVID-19 worries. Thus, ecological momentary interventions (McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2018) may be optimal to address these transitionary PTSD symptoms, as individuals can receive real-time, tailored feedback via a mobile application based on endorsed symptoms. Interestingly, we found that COVID-19 worries were less transitionary across days and less malleable to the influences of daily fluctuations in PTSD symptoms. In this regard, clinicians should be mindful that targeting PTSD symptoms therapeutically may not have long-lasting impacts on pre-existing COVID-19 anxieties and worries.

Second, it may be helpful for clinicians to routinely examine and therapeutically target daily worries related to the COVID-19 pandemic to potentially reduce PTSD severity, given that COVID-19 worries influenced same-day and next-day PTSD symptom severity. As part of early interventions, clinicians may consider providing psychoeducation on healthy coping mechanisms and exploring how the pandemic influences mental health for individuals presenting with PTSD symptoms. In this regard, some coping strategies for COVID-19 worries may be moderating consumption of media and news about the pandemic (González-Sanguino et al., 2020); engaging in mindfulness-based exercises and physical activity (Farris et al., 2021); and seeking positive social support (González-Sanguino et al., 2020).

Lastly, our findings add to existing cognitive and biologically-based theoretical frameworks of PTSD. Foa and Kozak’s (1986) Emotion Processing Theory explains that individuals, after experiencing traumatic events, develop associative fear-based networks, which include information about the feared stimuli, responses to that stimuli, as well as the perceived meaning of fear. These individuals may misinterpret neutral stimuli and events as overexaggerated threats, which activates these fear-based networks and contributes to an overexaggerated response to the stimuli. While COVID-19 is not a neutral event, our findings suggest that trauma-exposed individuals may perceive daily stressors or worries related to the pandemic as an overexaggerated threat, which may activate the associative fear structures and add to next-day PTSD symptoms (Black et al., 2021). This is further supported by Kolb’s two-factor learning theory (Black et al., 2021), stating that excessive threatening stimuli from a traumatic event can sensitize neuronal circuits responding to the threat, thus, creating a generalized sensitivity to all stimuli perceived as threatening such as stressors or worries in the context of COVID-19.

Although this study had several methodological strengths (e.g., micro-longitudinal design across 10 days, simultaneous and lagged analyses), some limitations need to be acknowledged. While we had 420 potential measurement occasions, more observations of PTSD symptoms and COVID-19 worries may offer more reliable estimates. However, this approach should always be weighed against participant burden. Also, while the COVID-19 Worries Scale demonstrated good reliability within our sample, future studies should focally validate and examine psychometric properties of this scale. Further, our non-clinical sample was educated, and most participants identified as young and non-Hispanic white, which limits generalizability to other samples. Studies have shown important racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in PTSD (Santos et al., 2008), and in the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (Do & Frank, 2021), which will be essential to examine in future studies on daily PTSD symptoms and COVID-19 worries. This being said, we note that several individuals reported a high rate of sexual assault, physical assault, and unwanted sexual experiences. While we controlled for COVID-19 exposure using two items of the COVID-19 Experiences and Exposure Scale, these two measures indicate a relatively indirect measurement of COVID-19 exposure. It is essential that future studies attempt to replicate our results in clinical samples with PTSD and direct exposure to COVID-19. Furthermore, although we administered the COVID-19 Experiences and Exposure Scale, we did not cue the PCL-5 to COVID-19 stressors (rather cued it to the most distressing trauma reported on the LEC-5). Thus, we were unable to assess whether participants also referenced the on-going COVID-19 stressors as index events while reporting PTSD symptoms (i.e., reactions to the COVID-19 reality were intertwined with reported PTSD symptoms). For instance, it is possible that participants may report feelings of being distant or cut off from other individuals as a reaction to social distancing practices; or may report concentration and sleep disturbances as side effects of working from home or schooling children (which may explain higher scores for PTSD NACM and AAR symptoms). Future studies could parse out PTSD symptoms exacerbated by the unique stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated mitigation procedures. Finally, it would be helpful to examine moderating and mediating variables (e.g., emotion dysregulation, coping) that could potentially influence the daily-level associations between PTSD symptoms and COVID-19 worries.

In conclusion, as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact individuals, it is imperative that emerging research captures mechanisms underlying and consequences of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on daily mental health. Specifically, a wealth of studies has documented impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on PTSD symptoms. Our results extend these findings by examining the bidirectional (lagged and simultaneous) nature of daily PTSD symptoms and COVID-19 worries in a trauma-exposed student sample that has been shown to report extensive rates of trauma and PTSD (Boals et al., 2020). The current study provides a methodological and statistical framework to investigate other potential COVID-19 factors (e.g., regional number of cases, vaccination rates) that may interact with PTSD symptoms on a daily basis. Findings support that mental health intervention and prevention strategies in disease outbreaks, along with data-driven accurate information, may minimize potential distress to individuals and downstream health and financial costs to societies. Additionally, findings potentially inform research and clinical care in future global health crises, in that daily stressors from global health crises may impact or exacerbate daily and next-day PTSD severity. Findings remain relevant beyond the scope of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic; PTSD interventions may consider providing psychoeducation on how daily life stressors related to global health crises may impact PTSD severity, as well as consider enhancing skills to cope with daily life stressors.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Impact Statement:

The present study suggests that, among trauma-exposed individuals, daily posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms (PTSD) are exacerbated by same-day or prior-day COVID-19 worries. Further, results suggest that daily PTSD symptoms exacerbate same-day COVID-19 worries. Clinicians may find it helpful to consider the potential interplay between on-going stressors related to the COVID-19 pandemic and posttrauma symptoms, and to therapeutically target COVID-19 stress and anxieties in PTSD interventions to influence treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgement.

We acknowledge Ms. Fallon Keegan, Ms. Stephanie Caldas, and Ms. Svetlana Goncharenko for aiding data collection and management.

Funding.

The work on this research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health awarded to Nicole H. Weiss (K23DA039327, P20GM125507).

Footnotes

Declaration of interests. The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Brett A. Messman, Department of Psychology, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, U.S

Hanan Rafiuddin, Department of Psychology, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, U.S.

Danica Slavish, Department of Psychology, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, U.S.

Nicole H. Weiss, Department of Psychology, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI

Ateka A. Contractor, Department of Psychology, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, U.S

References

- American Psychiatric Association, A., & Association, A. P. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (Vol. 10). Washington, DC: American psychiatric association. [Google Scholar]

- Black LL, Flynn S, & Ottens AJ (2021). In crisis, trauma and disaster a clinician’s guide. In In crisis, trauma and disaster a clinician’s guide (pp. 113–153). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, & Domino JL (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of traumatic stress, 28(6), 489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boals A, Contractor AA, & Blumenthal H (2020). The utility of college student samples in research on trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A critical review. Journal of anxiety disorders, 102235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, & Keane TM (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological assessment, 28(11), 1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones C, & Isham L (2020). The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of clinical nursing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Lanius RA, Novac A, Schnyder U, & Galea S (2009). Reformulating PTSD for DSM-V: life after criterion A. Journal of traumatic stress, 22(5), 366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgland VM, Moeck EK, Green DM, Swain TL, Nayda DM, Matson LA, Hutchison NP, & Takarangi MK (2021). Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. Plos one, 16(1), e0240146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, Belli GM, Asnaani A, & Foa EB (2019). A review of the role of negative cognitions about oneself, others, and the world in the treatment of PTSD. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 43(1), 143–173. [Google Scholar]

- Carmassi C, Foghi C, Dell’Oste V, Cordone A, Bertelloni CA, Bui E, & Dell’Osso L (2020). PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: What can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res, 292, 113312. 10.1016/i.psychres.2020.113312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AO, & Huak CY (2004). Psychological impact of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on health care workers in a medium size regional general hospital in Singapore. Occupational Medicine, 54(3), 190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SK, Chong GH, Chang SS, Wong CW, Wong CS, Wong MT, & Wong KC (2006). Adjustment to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): Roles of appraisal and post-traumatic growth. Psychology and Health, 21(3), 301–317. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey M, Stacy O, & Moely B (2000). “Approach” and “avoidance” coping and PTSD symptoms in innercity youth. Current Psychology, 19(1), 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Do DP, & Frank R (2021). Unequal burdens: assessing the determinants of elevated COVID-19 case and death rates in New York City’s racial/ethnic minority neighbourhoods. J Epidemiol Community Health, 75(4), 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L, & Zhu G (2020). Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), 300–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutheil F, Mondillon L, & Navel V (2020). PTSD as the second tsunami of the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic. Psychol Med, 1–2. 10.1017/s0033291720001336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SR, Grazzi L, Holley M, Dorsett A, Xing K, Pierce CR, Estave PM, O’Connell N, & Wells RE (2021). Online Mindfulness May Target Psychological Distress and Mental Health during COVID-19. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 10, 21649561211002461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, & Kozak MJ (1986). Emotional processing of fear: exposure to corrective information. Psychological bulletin, 99(1), 20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, & Casagrande M (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic in the Italian Population: Validation of a Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire and Prevalence of PTSD Symptomatology. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox R, Hyland P, Power JM, & Coogan AN (2020). Patterns of comorbidity associated with ICD-11 PTSD among older adults in the United States. Psychiatry Research, 113171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman S, Green T, & Armour C (2020). COVID-19 Questionnaires. 10.17605/OSF.IO/YQR2D [DOI]

- Galea S, Merchant RM, & Lurie N (2020). The Mental Health Consequences of COVID-19 and Physical Distancing: The Need for Prevention and Early Intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(6), 817–818. 10.1001/iamainternmed.2020.1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, Smith LJ, Richardson AL, & Long LJ (2021). Examining Associations Between COVID-19 Experiences and Posttraumatic Stress. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos MÁ, Saiz J, López-Gómez A, Ugidos C, & Muñoz M (2020). Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 87, 172–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths J, Fortune G, Barber V, & Young JD (2007). The prevalence of post traumatic stress disorder in survivors of ICU treatment: a systematic review. Intensive care medicine, 33(9), 1506–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing A, Zhang JS, Peng K, Lin W-K, Wu Y-H, Hsing JC, LaDuke P, Heaney C, Lu Y, & Lounsbury DW (2020). A rapid assessment of psychological distress and well-being: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and Shelter-in-Place. Available at SSRN; 3578809. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltman S, & Bonanno GA (2003). Trauma and bereavement:: Examining the impact of sudden and violent deaths. Journal of anxiety disorders, 17(2), 131–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, & Friedman MJ (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of traumatic stress, 26(5), 537–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, Wu J, Du H, Chen T, & Li R (2020). Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA network open, 3(3), e203976–e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen SE, & Pacella ML (2016). Comparing the effect of DSM-congruent traumas vs. DSM-incongruent stressors on PTSD symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Journal of anxiety disorders, 38, 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, Hyun S, & Hahm HC (2020). Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res, 290, 113172. 10.1016/i.psychres.2020.113172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, Jia Y, Shang Z, Sun L, Wu L, Sun Z, Zhou Y, Wang Y, & Liu W (2020). Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res, 287, 112921. 10.1016/i.psychres.2020.112921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy ME, Luciano MT, & Zakarian RJ (2018). Use of ecological momentary assessment and intervention in treatment with adults. Focus, 16(4), 370–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B, & North CS (2020). Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(6), 510–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, Heisterkamp S, Van Willigen B, & Maintainer R (2017). Package ‘nlme’. Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models, version, 3(1). [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, Marx BP, Kimerling R, Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, Kaloupek DG, Schnurr PP, Kaiser AP, & Leyva YE (2016). The primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(10), 1206–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudales AM, Weiss NH, Schmidt NB, & Short NA (2020). The role of emotion dysregulation in negative affect reactivity to a trauma cue: Differential associations through elicited posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 267, 203–210. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Bryk AS (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (Vol. 1). sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen Z, Weinberger-Litman SL, Rosenzweig C, Rosmarin DH, Muennig P, Carmody ER, Rao ST, & Litman L (2020). Anxiety and distress among the first community quarantined in the US due to COVID-19: Psychological implications for the unfolding crisis.

- Ruggero CJ, Schuler K, Waszczuk MA, Callahan JL, Contractor AA, Bennett CB, Luft BJ, & Kotov R (2021). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Daily Life Among World Trade Center Responders: Temporal Symptom Cascades. Journal of psychiatric research. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos MR, Russo J, Aisenberg G, Uehara E, Ghesquiere A, & Zatzick DF (2008). Ethnic/racial diversity and posttraumatic distress in the acute care medical setting. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 71(3), 234–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini G, Parmigiani B, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Sher L, & Amore M (2020). The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(8), 531–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin M, McBride O, Murphy J, Miller JG, Hartman TK, Levita L, Mason L, Martinez AP, McKay R, & Stocks TV (2020). Anxiety, Depression, Traumatic Stress, and COVID-19 Related Anxiety in the UK General Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stecker T, Shiner B, Watts BV, Jones M, & Conner KR (2013). Treatment-seeking barriers for veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts who screen positive for PTSD. Psychiatric Services, 64(3), 280–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team, R. C. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. http://www.R-project.org

- Thomas KA, & Clifford S (2017). Validity and Mechanical Turk: An assessment of exclusion methods and interactive experiments. Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 184–197. [Google Scholar]

- Tsur N, & Abu-Raiya H (2020). COVID-19-related fear and stress among individuals who experienced child abuse: The mediating effect of complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Child Abuse & Neglect, 104694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Minnen A, Zoellner LA, Harned MS, & Mills K (2015). Changes in comorbid conditions after prolonged exposure for PTSD: a literature review. Current psychiatry reports, 17(3), 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney M, Parel JT, Raizada N, & Sarin SK (2020). Initial psychological impact of COVID-19 and its correlates in Indian Community: An online (FEEL-COVID) survey. Plos one, 15(5), e0233874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, McIntyre RS, Choo FN, Tran B, Ho R, & Sharma VK (2020). A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain, behavior, and immunity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Blake DD, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, & Keane TM (2013). The life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5).

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, & Schnurr PP (2013). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov, 10.

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Anestis MD, & Gratz KL (2013). The relative and unique contributions of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity to posttraumatic stress disorder among substance dependent inpatients. Drug and alcohol dependence, 128(1-2), 45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Viana AG, Anestis MD, & Gratz KL (2012). Impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy: Examining associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors among substance dependent inpatients. Journal of anxiety disorders, 26(3), 453–458. 10.1016/i.janxdis.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, Fan B, Kong J, Yao Z, Liu X, Fuller CJ, Susser E, & Lu J (2009). The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(5), 302–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.