Abstract

目的

描述中国山东某县女性初潮年龄与绝经年龄长期趋势。

方法

应用研究地区婚前医学检查及宫颈癌和乳腺癌筛查资料,研究1951—1998年出生女性月经初潮年龄及1951—1975年出生女性绝经年龄长期变化趋势。采用Joinpoint回归确定初潮年龄长期趋势有无拐点以及拐点年份,采用多因素加权Cox回归估计不同年代出生女性较早绝经平均风险比(average hazard ratios,AHR)。

结果

1951年和1998年出生女性平均初潮年龄分别为(16.43±1.89)岁和(13.99±1.22)岁,城镇女性低于农村女性,教育水平越高女性平均初潮年龄越低;Joinpoint回归发现1959年、1973年和1993年三个拐点年份,1951—1959年、1960—1973年和1974—1993年出生者初潮年龄分别年均减小0.03岁(P < 0.001)、0.08岁(P < 0.001)和0.03岁(P < 0.001),1994—1998年出生者初潮年龄维持平稳(P=0.968)。与1951—1960年出生女性相比,1961—1965年、1966—1970年和1971—1975年出生者较早绝经风险总体上逐渐降低,绝经年龄呈现延迟趋势;分层分析显示,教育水平为初中及以下者较早绝经风险逐渐降低,绝经年龄呈现明显延迟趋势,但教育水平为高中及以上者这一趋势并不明显,其中教育水平为大专及以上者较早绝经风险先降后升,相应的AHR依次为0.90(0.66~1.22)、1.07(0.79~1.44)和1.14(0.79~1.66)。

结论

1951年以来出生女性初潮年龄逐渐下降,至1994年趋于平稳,40余年下降近2.5岁;1951—1975年出生女性绝经年龄总体上随时间推移而延迟,但教育水平相对较高人群呈现先延迟而后提前的趋势。在婚育年龄推迟与人群生育力下降的双重背景下,应加强女性基础生殖健康状况尤其是较早绝经风险的评估与监测。

Keywords: 月经初潮, 绝经, 年龄, 妇女卫生, 生殖健康

Abstract

Objective

To describe the secular trends of age at menarche and age at natural menopause of women from a county of Shandong Province.

Methods

Based on the data of the Premarital Medical Examination and the Cervical Cancer and Breast Cancer Screening of the county, the secular trends of age at menarche in women born in 1951 to 1998 and age at menopause in women born in 1951 to 1975 were studied. Joinpoint regression was used to identify potential inflection points regarding the trend of age at menarche. Average hazard ratios (AHR) of early menopause among women born in different generations were estimated by performing multivariate weighted Cox regression.

Results

The average age at menarche was (16.43±1.89) years for women born in 1951 and (13.99±1.22) years for women born in 1998. The average age at menarche was lower for urban women than that for rural women, and the higher the education level, the lower the average age at menarche. Joinpoint regression analysis identified three inflection points: 1959, 1973 and 1993. The average age at menarche decreased annually by 0.03 (P < 0.001), 0.08 (P < 0.001), and 0.03 (P < 0.001) years respectively for women born during 1951-1959, 1960-1973, and 1974-1993, while it remained stable for those born during 1994-1998 (P=0.968). As for age at menopause, compared with women born during 1951-1960, those born during 1961-1965, 1966-1970 and 1971-1975 showed a gradual decrease in the risk of early menopause and a tendency to delay the age at menopause. The stratified analysis presented that the risk of early menopause gradually decreased and the age of menopause showed a significant delay among those with education level of junior high school and below, but this trend was not obvious among those with education level of senior high school and above, where the risk of early menopause decreased and then increased among those with education level of college and above, and the corresponding AHRs were 0.90 (0.66-1.22), 1.07 (0.79-1.44) and 1.14 (0.79-1.66).

Conclusion

The age at menarche for women born since 1951 gradually declined until 1994 and leveled off, with a decrease of nearly 2.5 years in these years. The age at menopause for women born between 1951 and 1975 was generally delayed over time, but the trend of first increase and then decrease was observed among those with relatively higher education levels. In the context of the increasing delay in age at marriage and childbearing and the decline of fertility, this study highlights the necessity of the assessment and monitoring of women' s basic reproductive health status, especially the risk of early menopause.

Keywords: Menarche, Menopause, Age, Women' s health, Reproductive health

月经初潮与绝经是女性基础生殖特征,分别标志着女性生殖周期的开始与结束[1-2]。随着经济社会发展及基础营养状况改善,全球女性基础生殖特征在上个世纪发生较大变化[3-4]。美国的一项研究发现,1900年前后和1960年前后出生女性平均初潮年龄分别为13.5岁和12.7岁[5];基于在27个中低收入国家所做研究的汇总分析发现,1932—2002年出生女性平均初潮年龄从14.7岁下降至12.9岁[6]。此外,前述美国研究还发现同期出生女性平均自然绝经年龄由48.4岁增至49.9岁[5];一项挪威的研究发现,20世纪30年代末和60年代初出生女性平均绝经年龄分别为50.31岁和52.73岁[7]。大量研究证实,女性基础生殖特征与其健康状况密切相关,初潮过早不仅增加青春期社会心理问题,还会增加远期罹患肥胖、糖尿病、乳腺癌等疾病的风险[8-13];绝经过晚、行经年限延长则会造成内源性雌激素和孕激素累积性高暴露,增加乳腺癌、子宫内膜癌等激素相关疾病发生风险[14-15];而初潮过晚或绝经过早又会缩短女性生殖周期,进而影响生育及其健康状况。

随着我国经济社会快速发展,居民营养状况显著改善,中国女性基础生殖特征很可能发生了较大变化[16-17],但相关流行病学证据较为匮乏。针对我国改革开放前出生女性的一项研究发现,1930—1974年出生女性平均初潮年龄从16.1岁下降至14.3岁,1930—1950年出生女性平均绝经年龄从47.9岁增加至49.3岁[18]。在人群生育力较快下降、婚育年龄推迟的大背景下,研究我国女性基础生殖特征长期变化趋势,特别是新近趋势具有较高科学价值和重要现实意义。本研究依托山东某县较为完善的女性生殖健康相关项目资料,研究1951—1998年出生女性月经初潮年龄以及1951—1975年出生女性绝经年龄的长期变化特征。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 资料来源

研究所用资料包括山东某县宫颈癌和乳腺癌筛查数据(简称两癌数据)与婚前医学检查数据(简称婚检数据)。综合考虑资料完整性与可用性,两癌数据纳入时段为2019年1月至2021年9月,期间共有88 658人接受宫颈癌和乳腺癌筛查服务(第七次人口普查该县35~64岁女性共112 228人,据此推算筛查人群覆盖率约79%);婚检数据纳入时段为2017年5月至2021年9月,期间共为9 048名女性(其中5 002人为当地常住人口)提供婚前医学检查服务(同期该县共约11 600对夫妻登记结婚,据此推算婚检率约为78%)。

两癌数据与婚检数据均收集了参加对象的初潮年龄,故综合利用两类数据研究初潮年龄趋势,主要排除标准如下:(1)初潮年龄缺失;(2)初潮年龄可疑异常(< 5岁或>25岁);(3)重要基础变量缺失(包括出生日期、城乡);(4)剔除对象总数不足100人的年份的数据,以避免因样本不足而导致趋势的异常波动。两癌数据还收集了是否绝经以及已绝经对象的绝经年龄,故还依托该项目资料研究绝经年龄变化趋势,主要排除标准如下:(1)1976年及以后出生女性;(2)未报告是否绝经,或已绝经但绝经年龄不详;(3)绝经年龄可疑异常(< 40岁或>62岁);(4)子宫切除术后、卵巢切除术后或有激素替代治疗史;(5)重要基础变量缺失(包括出生日期、城乡、教育水平等);(6)对象总数不足100人的年份的数据。

1.2. 数据情况

两癌数据由医护人员通过专用调查表收集,主要包括如下信息:(1)一般人口学特征(出生日期、现住址、教育水平等);(2)月经情况(初潮年龄、末次月经、是否绝经、绝经年龄等);(3)孕产史与哺乳史等其他信息。婚检数据由婚检医师通过面对面询问的方式收集女性出生日期、现住址、教育水平、民族以及初潮年龄等信息。

研究除了提取出生年份、初潮年龄、绝经年龄等关键数据外,还提取了居住地(城镇、农村)、民族(汉族、非汉族)、教育水平(小学及以下、初中、高中或中专、大专及以上)等人口学特征。

1.3. 统计学分析

1.3.1. 初潮年龄分析

采用均数±标准差及中位数(四分位数间距)描述初潮年龄分布特征,采用t检验、方差分析或秩和检验比较不同特征群体初潮年龄分布差异情况。采用Joinpoint回归分析初潮年龄长期变化趋势并确定有无拐点以及拐点年份,在此基础上应用一般线性模型(general linear model,GLM)调整城乡、民族及教育水平,量化评价初潮年龄随时间变化特征。

1.3.2. 绝经年龄与行经年限分析

以绝经为结局事件,以绝经年龄为生存时间变量(未绝经者按截尾数据处理),估计平均绝经年龄及中位绝经年龄,并绘制Kaplan-Meier曲线,采用log-rank检验比较不同特征群体绝经年龄分布差异。应用时协变量法检验比例风险(proportional hazards,PH)假定,若满足该假定则采用Cox比例风险模型量化估计出生年代与较早绝经风险之间的关联,若不满足该假定则采用加权Cox回归计算相应的平均风险比(average hazard ratios,AHR)[19-20]。同时以城乡与教育水平为分层变量开展分层分析,探究不同特征人群绝经年龄长期趋势。Joinpoint回归通过专用软件Joinpoint Regression Program 4.9.0.1完成,加权Cox回归通过R软件coxphw程序包[21]完成,其余分析使用SAS 9.4软件完成。显著性水平均为双侧α=0.05。

2. 结果

研究期间婚检数据研究对象共有5 002人次,两癌数据研究对象共有88 658人次,经数据清理和去重处理,共58 114人纳入初潮年龄分析,出生年份范围为1951—1998年;38 483人纳入绝经年龄分析,出生年份范围为1951—1975年。数据清理和去重过程详见图 1。

图 1.

初潮年龄与绝经年龄趋势分析的研究对象纳入和排除流程

The flow chart of subjects' inclusion on the analyses of secular trends of age at menarche and age at menopause

2.1. 初潮年龄分析

全部研究对象平均初潮年龄为(15.17±1.61)岁,总体看出生年代越早平均初潮年龄越高,城镇女性平均初潮年龄低于农村女性,教育水平越高平均初潮年龄越低,具体情况详见表 1。

表 1.

不同特征人群初潮年龄分布情况(n=58 114)

Distribution of age at menarche in different population groups (n=58 114)

| Characteristic | Total, n(%) | Age at menarche | P value | |

| Mean±SD | M (P25, P75) | |||

| Birth cohort | < 0.001 | |||

| 1951-1959 | 7 247 (12.47) | 16.23±1.93 | 16.00 (15.00, 18.00) | |

| 1960-1969 | 20 766 (35.73) | 15.56±1.55 | 15.00 (15.00, 16.00) | |

| 1970-1979 | 17 365 (29.88) | 14.89±1.34 | 15.00 (14.00, 16.00) | |

| 1980-1989 | 8 245 (14.19) | 14.43±1.28 | 15.00 (14.00, 15.00) | |

| 1990-1998 | 4 491 (7.73) | 14.05±1.25 | 14.00 (13.00, 15.00) | |

| Region | < 0.001 | |||

| Urban | 40 598 (69.86) | 15.10±1.57 | 15.00 (14.00, 16.00) | |

| Rural | 17 516 (30.14) | 15.34±1.70 | 15.00 (14.00, 16.00) | |

| Educational level | < 0.001 | |||

| Primary school or below | 17 559 (30.21) | 15.75±1.72 | 15.00 (15.00, 17.00) | |

| Junior high school | 24 094 (41.46) | 15.18±1.49 | 15.00 (14.00, 16.00) | |

| Senior high school | 8 432 (14.51) | 14.80±1.47 | 15.00 (14.00, 16.00) | |

| College or above | 7 973 (13.72) | 14.24±1.31 | 14.00 (13.00, 15.00) | |

| Unknown | 56 (0.10) | 14.68±1.16 | 15.00 (14.00, 15.00) | |

进一步分析发现,1951—1998年出生女性初潮年龄由(16.43±1.89)岁下降至(13.99±1.22)岁(图 2A)。图 2B给出了城镇女性和农村女性平均初潮年龄长期趋势,由图可见绝大多数年份城镇女性平均初潮年龄略低于农村女性。

图 2.

月经初潮年龄的长期变化趋势

Secular trend of age at menarche

A, total (x±s); B, by region.

Joinpoint回归分析发现1959年、1973年以及1993年为平均初潮年龄的3个拐点年份。以相应出生年份为节点进行分段GLM回归发现,1951—1959年出生女性的初潮年龄年均减小0.03岁(P < 0.001),1960—1973年出生女性年均减少0.08岁(P < 0.001),1974—1993年出生女性年均减少0.03岁(P < 0.001),1994—1998年出生女性初潮年龄维持平稳(P=0.968),结果详见表 2。

表 2.

月经初潮年龄分段一般线性模型回归分析结果

Segmented general linear model regression analysis of age at menarche

| Birth cohort | β | SE | t | P value |

| Adjust region, educational levels and ethnic groups. | ||||

| 1951-1959 | -0.03 | 0.008 | -4.38 | < 0.001 |

| 1960-1973 | -0.08 | 0.002 | -47.55 | < 0.001 |

| 1974-1993 | -0.03 | 0.002 | -17.55 | < 0.001 |

| 1994-1998 | 0.00 | 0.014 | 0.04 | 0.97 |

2.2. 绝经年龄与行经年限分析

纳入分析对象共38 483人,其中27 576人(71.66%)已绝经,已绝经者平均绝经年龄为(49.83±3.85)岁。单变量log-rank检验显示,出生年代、城乡、教育水平与绝经年龄的关系具有统计学意义(P < 0.05),结果详见表 3。

表 3.

不同特征人群绝经年龄分布情况(n=38 483)

Distribution of age at menopause in different population groups (n=38 483)

| Characteristic | Total, n(%) | Postmenopausal, n(%) | Age at menopause | χ 2 | P value | |

| Mean±SEa | M (P25, P75)b | |||||

| a, the mean survival time and its standard error might be underestimated because the largest observation was censored and the estimation was res-tricted to the largest event time; b, the median survival time and interquartile range. | ||||||

| Birth cohort | 42.969 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 1951-1960 | 7 853 (20.41) | 7 845 (99.90) | 50.24±0.05 | 50.00 (48.00, 53.00) | ||

| 1961-1965 | 10 275 (26.70) | 10 015 (97.47) | 50.71±0.04 | 51.00 (49.00, 53.00) | ||

| 1966-1970 | 11 815 (30.70) | 8 046 (68.10) | 50.95±0.04 | 51.00 (49.00, 53.00) | ||

| 1971-1975 | 8 540 (22.19) | 1 670 (19.56) | 50.10±0.19 | 51.00 (49.00, 52.00) | ||

| Region | 7.605 | 0.006 | ||||

| Urban | 26 083 (67.78) | 18 302 (70.17) | 50.81±0.03 | 51.00 (49.00, 53.00) | ||

| Rural | 12 400 (32.22) | 9 274 (74.79) | 50.60±0.04 | 51.00 (49.00, 53.00) | ||

| Educational level | 29.068 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Primary school or below | 16 092 (41.82) | 13 280 (82.53) | 50.49±0.03 | 51.00 (48.00, 53.00) | ||

| Junior high school | 17 335 (45.05) | 11 281 (65.08) | 50.89±0.03 | 51.00 (49.00, 53.00) | ||

| Senior high school | 3 613 (9.39) | 2 335 (64.63) | 50.96±0.07 | 51.00 (49.00, 53.00) | ||

| College or above | 1 443 (3.75) | 680 (47.12) | 51.13±0.11 | 51.00 (50.00, 53.00) | ||

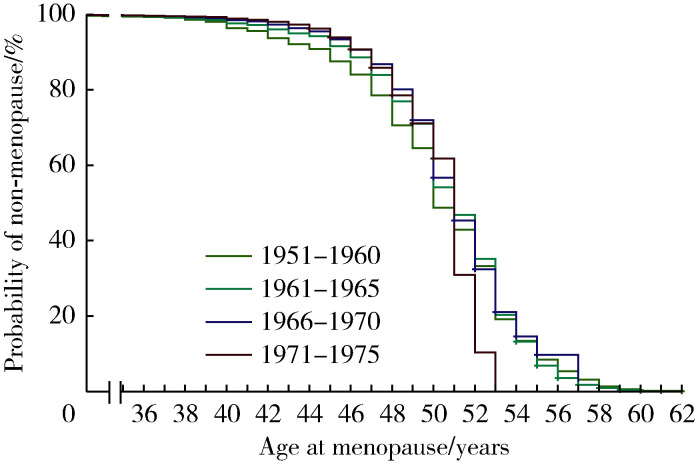

图 3为不同年代出生女性绝经年龄Kaplan-Meier曲线,由图可见,与1951—1960年出生女性相比,其他年代出生者较早绝经风险更低,绝经年龄整体呈延迟趋势。按城乡分层分析发现,农村居民和城镇居民绝经年龄的长期趋势均与总体情况类似,但农村居民延迟趋势略为明显(图 4)。按教育水平分层分析发现,教育水平为初中及以下者较早绝经风险逐渐降低、绝经年龄呈现延迟趋势,教育水平为高中及以上者这一趋势并不明显(图 5)。

图 3.

不同出生年代女性绝经年龄的Kaplan-Meier曲线

Kaplan-Meier curve of age at menopause among women in different birth cohorts

图 4.

不同出生年代女性绝经年龄的Kaplan-Meier曲线(按城乡分层)

Kaplan-Meier curve of age at menopause among women in different birth cohorts (by region)

图 5.

不同出生年代女性绝经年龄的Kaplan-Meier曲线(按教育水平分层)

Kaplan-Meier curve of age at menopause among women in different birth cohorts (by educational level)

经检验出生年份与绝经年龄关系不满足PH假定(P < 0.001),故应用加权Cox回归估计出生年代与较早绝经之间的关联。总体上看,与1951—1960年出生女性相比,此后出生者较早绝经风险逐渐降低,女性绝经年龄整体呈现延迟趋势。按照城乡分层分析显示,农村与城镇女性绝经年龄的时间趋势与总体情况类似。按照教育水平分层分析显示,初中及以下者较早绝经风险逐渐降低,绝经年龄呈现明显延迟趋势;教育水平为高中或中专者,与1951—1960年出生者相比,1961—1965年、1966—1970年出生者较早绝经风险降低,但1971—1975年出生者较早绝经风险与之相仿;教育水平为大专及以上者,与1951—1960年出生者相比,1961—1965年、1966—1970年及1971—1975年出生者较早绝经风险先降后升,其AHR依次为0.90(0.66~1.22)、1.07(0.79~1.44)和1.14(0.79~1.66),绝经年龄呈现先延迟后提前的趋势。以上结果详见表 4。

表 4.

出生年代与较早绝经的关联分析

Association between birth cohorts and early menopause

| Birth cohort | Adjusted AHR (95%CI) | |||

| 1951-1960 | 1961-1965 | 1966-1970 | 1971-1975 | |

| AHR, average hazard ratios. | ||||

| Total | Reference | 0.91 (0.88-0.94) | 0.89 (0.86-0.91) | 0.80 (0.75-0.84) |

| Region | ||||

| Rural | Reference | 0.90 (0.86-0.95) | 0.84 (0.80-0.89) | 0.71 (0.64-0.78) |

| Urban | Reference | 0.92 (0.89-0.96) | 0.91 (0.88-0.95) | 0.85 (0.79-0.91) |

| Educational level | ||||

| Primary school or below | Reference | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | 0.87 (0.83-0.91) | 0.81 (0.73-0.89) |

| Junior high school | Reference | 0.92 (0.86-0.98) | 0.94 (0.88-1.00) | 0.86 (0.79-0.94) |

| Senior high school | Reference | 0.81 (0.72-0.90) | 0.86 (0.77-0.97) | 0.87 (0.72-1.06) |

| College or above | Reference | 0.90 (0.66-1.22) | 1.07 (0.79-1.44) | 1.14 (0.79-1.66) |

3. 讨论

本研究利用妇幼保健常规数据分析了女性基础生殖特征长期变化趋势,发现1951年以来出生女性初潮年龄逐渐下降,至1994年趋于平稳,40余年共下降近2.5岁。研究还发现1951—1975年出生女性绝经年龄总体上随时间推移呈延迟趋势,但学历较高人群绝经年龄呈现先延迟而后又有所提前的趋势。

随着经济社会发展与营养状况改善,女性平均初潮年龄从19至20世纪以来总体上呈下降趋势,部分国家在经历了下降期后步入平台期[6, 22-24],也有国家出现小幅回升[2]。一项基于中国慢性病前瞻性研究数据(China Kadoorie Biobank,CKB)的研究分析了新中国成立前后出生女性初潮年龄变化趋势[18],发现1930年出生者初潮年龄为16. 1岁,1974年出生者降至14.3岁,下降速度同比快于英国和美国女性;云南一项研究发现1965—2001年出生女性的初潮年龄从14. 1岁下降至13. 3岁[25],该研究农民占97%, 少数民族占36%;另有一项研究通过分析全国12省市样本数据发现1973—2004年出生女性的初潮年龄从14.3岁下降至12.6岁[26],其样本量相对较小,年均仅约100人,研究期间部分年份初潮年龄波动较大。

前述三项研究主要通过逐个年份或逐个时段描述以及绘图方式分析初潮年龄变化趋势,均未探究变化趋势是否存在拐点。本研究利用Joinpoint回归针对初潮年龄变化趋势识别出3个拐点年份并据此将整个研究划分为4个时段,发现前3个时段初潮年龄均呈下降趋势但下降速度存在差异,而第4个时段即1994年及以后出生的女性初潮年龄维持平稳,提示研究地区女性初潮年龄在经历了较长周期的下降后已步入平台期,这一发现对于科学把握育龄女性基础生殖特征有重要价值。未来宜依托更大范围人群数据,分析其他地区女性初潮年龄是否呈相似趋势,同时加强对女性初潮年龄变化情况的监测,探究研究地区的平台期是否长期稳定。

本研究发现1951—1959年出生女性初潮年龄下降趋势较缓且波动较大,推测与这些女性在1959—1961年正值幼儿期至青春前期有关。既往研究表明,女童在幼儿期至青春前期热量摄入不足以及营养缺乏可能会延迟下丘脑促性腺激素释放激素释放,进而导致初潮年龄推迟[27-29]。CKB研究也发现我国1940—1950年出生女性初潮年龄相对推迟1年左右,1950—1960年出生女性初潮年龄下降趋势较缓且波动较大[18]。

绝经年龄是女性另一基础生殖特征,多数研究表明绝经年龄自上个世纪以来总体呈现逐步延迟趋势。2021年有学者利用美国健康与营养调查数据研究了女性自然绝经年龄长期趋势[5],发现平均绝经年龄由1900年前后出生女性的48.4岁增至1945年前后的49.9岁。前述CKB研究也同时分析了中国女性绝经年龄变化趋势,发现1930—1950年出生女性平均绝经年龄从47.9岁增至49.3岁[18]。本研究纳入绝经年龄分析的女性的出生年份跨度为1951—1975年,绝经年龄总体上随时间推移亦呈现延迟趋势,推测与经济社会发展、生活方式转变、营养状况改善、医疗保健条件提升等有关[1-2, 30]。近年来国际上也有研究发现女性绝经年龄延迟停滞甚至出现了逆转,比如,前述2021年美国健康与营养调查数据显示,1945—1960年前后出生女性的平均绝经年龄始终保持在49.9岁,不再随时间推移呈现延迟趋势[5];英国研究发现1925—1944年出生女性绝经年龄呈上升趋势,但1945—1955年出生者绝经年龄有所下降[31];葡萄牙1900—1931年出生女性绝经年龄呈上升趋势,但1932—1963年出生女性绝经年龄呈下降趋势[32]。循证证据提示,初潮提前、产次减少、吸烟、工作压力大、轮班工作等因素增加女性绝经提前的风险[33-35],这些因素可能与前述英国、葡萄牙女性绝经年龄提前有关。国内虽有卵巢早衰发病增多的相关报道[36-37],但未见绝经年龄提前的流行病学证据。本研究发现教育程度相对较高人群绝经年龄呈现先延迟而后又有所提前的趋势,这与前述英国、葡萄牙相关研究结果一致,提示在婚育年龄推迟的大背景下女性生育周期有可能会因绝经提前而被进一步挤压。当前我国生育形势严峻、人群生育力较快下降,有必要加强女性绝经年龄的监测与评估,并探讨其对女性生育情况和健康状况的影响。

本研究有以下局限性:(1)初潮年龄与绝经年龄均为研究对象自报,不能排除信息偏倚,但本研究获得的平均初潮年龄与平均绝经年龄与国内同类研究相仿[38-39]。由于初潮与绝经是女性重要生殖事件,既往研究也表明其回忆可信度较高且无明显偏倚[40-41]。本研究初潮年龄来源于两癌数据、婚检数据两个数据库,在两个数据库均报告初潮年龄的研究对象有394人,其中302人(76.6%)两次自报初潮年龄相差≤1岁,数据一致性较高且无明显的系统性偏差,尽管如此,本研究仍无法从根本上避免资料可能不够准确的问题,鉴于此,将来可以通过前瞻性设计,加强在数据收集过程中的质量控制,提高研究资料的准确性,进而提升研究结论的稳定性和可靠性。(2)研究所用的两癌数据和婚检数据各覆盖研究地区近80%的目标女性,虽然覆盖面较广但仍不能除外选择偏倚。(3)1971—1975年出生女性参加调查时年龄相对偏小,已绝经者占比约20%,已绝经者的平均绝经年龄会低估整批女性的平均绝经年龄。鉴于这一数据特点,本研究通过生存分析量化估计出生年代与较早绝经风险的关联,相对而言其结果更为可靠。(4)研究对象来自于山东某县,该县位列全国经济百强县,研究结果对于同类地区或有参考价值,但向更大范围地区外推宜谨慎。将来有必要开展多中心、大样本研究,探究较大范围中国女性初潮年龄与绝经年龄的长期变化趋势。(5)初潮年龄长期趋势的研究对象出生年份范围为1951—1998年,仅观察到1994—1998年5年的平台期,该平台期是否长期稳定尚不可知,有待更长周期的随访观察。

综上,本研究发现研究地区1951年以来出生女性的初潮年龄随着时间推移呈持续下降趋势,至1994年进入平台期;1951—1975年出生女性绝经年龄随时间推移而延迟,但教育水平相对较高女性绝经年龄呈现先延迟而后提前趋势。在生育形势严峻的背景下,宜加强对女性基础生殖健康状况尤其是较早绝经风险的监测与评估。

志谢

感谢桓台县妇幼保健院参加宫颈癌和乳腺癌筛查与婚前医学检查的全体工作人员。

Funding Statement

中央高校基本科研业务费专项资金(BMU2021RCZX029)

Supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (BMU2021RCZX029)

Contributor Information

穆 英超 (Ying-chao MU), Email: 1319094858@qq.com.

李 宏田 (Hong-tian LI), Email: lihongtian@pku.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Gold EB. The timing of the age at which natural menopause occurs. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011;38(3):425–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichols HB, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM, et al. From menarche to menopause: Trends among US women born from 1912 to 1969. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(10):1003–1011. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomula A, Koziel S. Secular trend and social variation in age at menarche among Polish schoolgirls before and after the political transformation. Am J Hum Biol. 2018;30(1):e23048. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.23048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.InterLACE Study Team Variations in reproductive events across life: A pooled analysis of data from 505 147 women across 10 countries. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(5):881–893. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appiah D, Nwabuo CC, Ebong IA, et al. Trends in age at natural menopause and reproductive life span among US women, 1959-2018. JAMA. 2021;325(13):1328–1330. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leone T, Brown LJ. Timing and determinants of age at menarche in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(12):e003689. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottschalk MS, Eskild A, Hofvind S, et al. Temporal trends in age at menarche and age at menopause: A population study of 312 656 women in Norway. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(2):464–471. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu X, Cai H, Kallianpur A, et al. Age at menarche and natural menopause and number of reproductive years in association with mortality: Results from a median follow-up of 11.2 years among 31 955 naturally menopausal Chinese women. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canoy D, Beral V, Balkwill A, et al. Age at menarche and risks of coronary heart and other vascular diseases in a large UK cohort. Circulation. 2015;131(3):237–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copeland W, Shanahan L, Miller S, et al. Outcomes of early pubertal timing in young women: A prospective population-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(10):1218–1225. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreyfus JG, Lutsey PL, Huxley R, et al. Age at menarche and risk of type 2 diabetes among African-American and white women in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Diabetologia. 2012;55(9):2371–2380. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2616-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farahmand M, Ramezani Tehrani F, Khalili D, et al. Is there any association between age at menarche and anthropometric indices? A 15-year follow-up population-based cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179(9):1379–1388. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03575-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang L, Li L, Millwood IY, et al. Adiposity in relation to age at menarche and other reproductive factors among 300 000 Chinese women: Findings from China Kadoorie Biobank study. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(2):502–512. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dossus L, Allen N, Kaaks R, et al. Reproductive risk factors and endometrial cancer: The European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(2):442–451. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: Individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(11):1141–1151. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70425-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding QJ, Hesketh T. Family size, fertility preferences, and sex ratio in China in the era of the one child family policy: Results from national family planning and reproductive health survey. BMJ. 2006;333(7564):371–373. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38775.672662.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu X, Bao L, Du Z, et al. Secular trends of age at menarche and the effect of famine exposure on age at menarche in rural Chinese women. Ann Hum Biol. 2022;49(1):35–40. doi: 10.1080/03014460.2022.2041092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewington S, Li L, Murugasen S, et al. Temporal trends of main reproductive characteristics in ten urban and rural regions of China: The China Kadoorie biobank study of 300 000 women. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(4):1252–1262. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rauch G, Brannath W, Brückner M, et al. The average hazard ratio: A good effect measure for time-to-event endpoints when the proportional hazard assumption is violated? Methods Inf Med. 2018;57(3):89–100. doi: 10.3414/ME17-01-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schemper M, Wakounig S, Heinze G. The estimation of average hazard ratios by weighted Cox regression. Stat Med. 2009;28(19):2473–2489. doi: 10.1002/sim.3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunkler D, Ploner M, Schemper M, et al. Weighted cox regression using the R package coxphw. J Stat Softw. 2018;84(2):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parent AS, Teilmann G, Juul A, et al. The timing of normal puberty and the age limits of sexual precocity: Variations around the world, secular trends, and changes after migration. Endocr Rev. 2003;24(5):668–693. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gohlke B, Woelfle J. Growth and puberty in German children: Is there still a positive secular trend? Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106(23):377–382. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vercauteren M, Susanne C. The secular trend of height and me-narche in Belgium: Are there any signs of a future stop? Eur J Pediatr. 1985;144(4):306–309. doi: 10.1007/BF00441769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W, Yan X, Li C, et al. A secular trend in age at menarche in Yunnan Province, China: A multiethnic population study of 1 275 000 women. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1890. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11951-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng X, Li S, Duan W, et al. Secular trend of age at menarche in Chinese adolescents born from 1973 to 2004. Pediatrics. 2017;140(2):e20170085. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Schnurbein J, Moss A, Nagel SA, et al. Leptin substitution results in the induction of menstrual cycles in an adolescent with leptin deficiency and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Horm Res Paediatr. 2012;77(2):127–133. doi: 10.1159/000336003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yermachenko A, Dvornyk V. Nongenetic determinants of age at menarche: A systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:371583. doi: 10.1155/2014/371583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang B, Ostbye T, Huang X, et al. Maternal age at menarche and pubertal timing in boys and girls: A cohort study from Chongqing, China. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(3):508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoenaker DA, Jackson CA, Rowlands JV, et al. Socioeconomic position, lifestyle factors and age at natural menopause: A syste-matic review and meta-analyses of studies across six continents. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(5):1542–1562. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gentry-Maharaj A, Glazer C, Burnell M, et al. Changing trends in reproductive/lifestyle factors in UK women: Descriptive study within the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e011822. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duarte E, de Sousa B, Cadarso-Suarez C, et al. Structured additive regression modeling of age of menarche and menopause in a breast cancer screening program. Biom J. 2014;56(3):416–427. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201200260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martelli M, Zingaretti L, Salvio G, et al. Influence of work on andropause and menopause: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):10074. doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu D, Chung HF, Pandeya N, et al. Relationships between intensity, duration, cumulative dose, and timing of smoking with age at menopause: A pooled analysis of individual data from 17 observational studies. PLoS Med. 2018;15(11):e1002704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishra GD, Chung HF, Cano A, et al. EMAS position statement: Predictors of premature and early natural menopause. Maturitas. 2019;123:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.毕 丹, 林 秀文, 程 红玲, et al. 卵巢早衰的性激素水平分析及临床发病率. 中国妇幼保健. 2005;20(19):2568–2569. [Google Scholar]

- 37.郭 琪, 梁 晓燕. 干细胞在早发性卵巢功能不全中的应用. 中华生殖与避孕杂志. 2021;41(6):557–561. [Google Scholar]

- 38.林 丽玲, 郑 棒, 吕 筠, et al. 中国10个地区成年女性初潮年龄与身高和腿长的关联研究. 中华流行病学杂志. 2016;37(11):1454–1458. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.肖 悦, 高 文会, 王 鲜, et al. 轮班对妇女绝经年龄及行经年限的影响. 中华劳动卫生职业病杂志. 2021;39(6):472–474. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121094-20201110-00622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rödström K, Bengtsson C, Lissner L, et al. Reproducibility of self-reported menopause age at the 24-year follow-up of a population study of women in Göteborg, Sweden. Menopause. 2005;12(3):275–280. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000135247.11972.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundblad MW, Jacobsen BK. The reproducibility of self-reported age at menarche: The Tromsø Study. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0420-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]