Abstract

目的

探究应激性血糖升高与重症监护病房(intensive care unit, ICU) 患者28 d全因死亡风险之间的关系, 并比较不同应激性血糖升高指标的预测效能。

方法

以重症医学(Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care Ⅳ, MIMIC-Ⅳ) 数据库中符合纳入、排除标准的ICU患者为研究对象,将应激性血糖升高指标按照百分位数分为Q1(0~25%)、Q2(>25%~75%)、Q3(>75%~100%)组,以是否发生ICU内死亡及在ICU内接受治疗的时间为结局变量,以人口学特征、实验室指标、合并症等为协变量,利用Cox回归及限制性立方样条探究应激性血糖升高和ICU患者28 d全因死亡风险之间的关联; 采用受试者工作特征(receiver operation characteristic, ROC)曲线下面积(area under curve, AUC)评价不同应激性血糖升高指标的预测效能,应激性血糖升高指标包括应激性血糖升高比值(stress hyperglycemia ratio, SHR) 1、SHR2、血糖间隙(glucose gap, GG); 进一步将应激性血糖升高指标纳入牛津急性疾病严重程度评分(Oxford acute severity of illness score, OASIS),探究其改善评分的预测效能,即采用AUC评估评分区分度,AUC越大表明评分区分度越好,采用Brier score评价评分校准度,Brier score越小,表明评分校准度越好。

结果

共纳入5 249例ICU患者,其中发生ICU内死亡的患者占7.56%。调整混杂因素后的Cox回归分析结果表明,SHR1、SHR2和GG的最高组Q3与最低组Q1相比,ICU患者28 d全因死亡HR(95%CI)分别为1.545(1.077~2.217)、1.602(1.142~2.249)和1.442(1.001~2.061),且随着应激性血糖升高指标的增加,ICU患者死亡风险也逐渐增加(Ptrend < 0.05)。限制性立方样条分析表明,SHR和28 d全因死亡风险之间呈线性关系(P>0.05)。SHR2和GG的AUC显著高于SHR1: AUCSHR2=0.691(95%CI: 0.661~0.720),AUCGG=0.685(95%CI: 0.655~0.714),AUCSHR1=0.680(95%CI: 0.650~0.709),P < 0.05。将SHR2纳入OASIS评分中,能显著提高评分的区分度和校准度:AUCOASIS=0.820(95%CI: 0.791~0.848),AUCOASIS+SHR2=0.832(95%CI: 0.804~0.859),P < 0.05; Brier scoreOASIS=0.071,Brier scoreOASIS+SHR2= 0.069。

结论

应激性血糖升高与ICU患者28 d全因死亡风险密切相关,可为重症监护患者的临床管理和决策提供参考。

Keywords: 应激性血糖升高, 重症监护病房, 死亡风险, Cox回归, 限制性立方样条

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationship between stress glucose elevation and the risk of 28 d all-cause mortality in intensive care unit (ICU) patients, and to compare the predictive efficacy of different stress glucose elevation indicators.

Methods

ICU patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care Ⅳ (MIMIC-Ⅳ) database were used as the study subjects, and the stress glucose elevation indicators were divided into Q1 (0-25%), Q2 (>25%- 75%), and Q3 (>75%-100%) groups, with whether death occurred in the ICU and the duration of treatment in the ICU as outcome variables, and demographic characteristics, laboratory indicators, and comorbidities as covariates, Cox regression and restricted cubic splines were used to explore the association between stress glucose elevation and the risk of 28 d all-cause death in ICU patients; and subject work characteristics [receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and the area under curve (AUC)] were used to evaluate the predictive efficacy of different stress glucose elevation indicators, The stress hyperglycemia indexes included: stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR1, SHR2), glucose gap (GG); and the stress hyperglycemia index was further incorporated into the Oxford acute severity of illness score (OASIS) to investigate the predictive efficacy of the improved scores: the AUC was used to assess the score discrimination, and the larger the AUC indicated, the better score discrimination. The Brier score was used to evaluate the calibration of the score, and a smaller Brier score indicated a better calibration of the score.

Results

A total of 5 249 ICU patients were included, of whom 7.56% occurred in ICU death. Cox regression analysis after adjusting for confounders showed that the HR (95%CI) for 28 d all-cause mortality in the ICU patients was 1.545 (1.077-2.217), 1.602 (1.142-2.249) and 1.442 (1.001-2.061) for the highest group Q3 compared with the lowest group Q1 for SHR1, SHR2 and GG, respectively, and The risk of death in the ICU patients increased progressively with increasing indicators of stressful blood glucose elevation (Ptrend < 0.05). Restricted cubic spline analysis showed a linear relationship between SHR and the 28 d all-cause mortality risk (P>0.05). the AUC of SHR2 and GG was significantly higher than that of SHR1: AUCSHR2=0.691 (95%CI: 0.661-0.720), AUCGG=0.685 (95%CI: 0.655-0.714), and AUCSHR1=0.680 (95%CI: 0.650-0.709), P < 0.05. The inclusion of SHR2 in the OASIS scores significantly improved the discrimination and calibration of the scores: AUCOASIS=0.820 (95%CI: 0.791-0.848), AUCOASIS+SHR2=0.832 (95%CI: 0.804-0.859), P < 0.05; Brier scoreOASIS=0.071, Brier scoreOASIS+SHR2=0.069.

Conclusion

Stressful glucose elevation is strongly associated with 28 d all-cause mortality risk in ICU patients and may inform clinical management and decision making in intensive care patients.

Keywords: Stress-induced hyperglycemia, Intensive care unit, Risk of death, Cox regression, Restricted cubic splines

重症监护病房(intensive care unit, ICU)是专门收治危重病症患者并给予精心监测和精确治疗的医疗单元,其患者病情复杂多变,在短时间内快速评估并做出科学决策对挽救患者生命具有重要意义[1],因此,寻找易得有效的生物标志物对降低检查成本、提高诊治效率具有重要临床指导意义。应激性血糖升高(stress-induced hyperglycemia, SIH)指患者由于急性疾病或应激反应引起的短暂性血糖升高的临床现象,常见于ICU患者[2-3],该现象常用血糖相对指标,即应激性血糖升高比值(stress hyperglycemia ratio, SHR)[4]和血糖间隙(glucose gap, GG)[5]进行测量,其计算是基于血糖绝对指标, 即入院即刻血糖(admission glucose, AG)和糖化血红蛋白(glyca-ted hemoglobin, HbA1c)。越来越多的研究表明[6-8],相较于绝对指标,血糖相对指标与患者不良结局有更为密切的关联。既往研究较多聚焦于探究SIH与心肌梗死[9]、缺血性卒中[10]、糖尿病[11]等疾病死亡风险之间的关联,SIH与ICU患者死亡风险关联的相关研究较少,且缺乏不同血糖相对指标间的比较研究。本研究基于ICU患者的临床数据,探究SIH指标对患者28 d死亡风险的影响,并比较不同SIH指标对患者28 d死亡风险的预测效能,以期为重症监护患者的管理和临床决策提供参考。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 资料来源

研究对象来自重症医学(Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care Ⅳ, MIMIC-Ⅳ) 数据库[12],该数据库由美国贝斯以色列执事医学中心(Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center)于2008—2019年收集,包含256 878例患者真实临床信息,其详细记录了患者人口学信息、实验室检查、生命体征、生存状态,用药及手术操作等信息。该数据库的患者相关信息均去隐私化,本研究已获得该数据库使用权限(ID: 11696272),知情同意得到豁免。

1.2. 研究对象纳入、排除标准

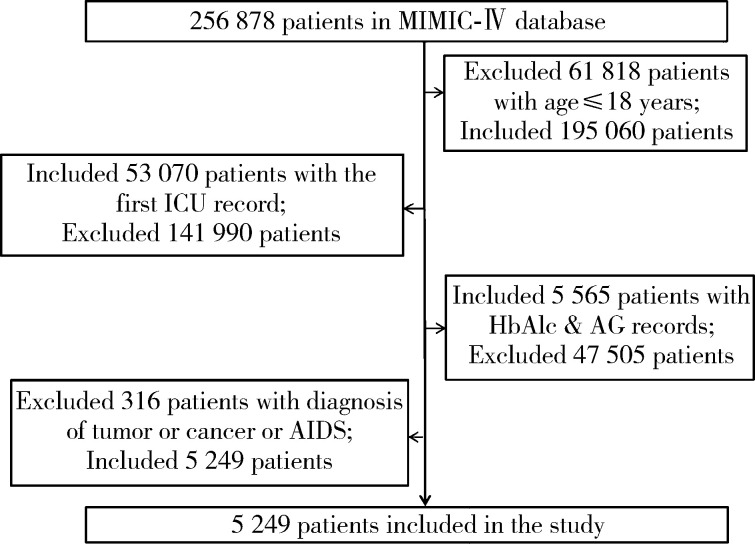

本研究选取MIMIC-Ⅳ数据库中首次进入ICU的患者为研究对象。纳入标准:(1)年龄>18岁; (2)有首次进入ICU的病例记录; (3)含有进入ICU的HbA1c和AG的测量记录。排除标准:患肿瘤、癌症、艾滋病等疾病。研究对象纳入、排除流程见图 1。

图 1.

研究对象纳入、排除流程图

Flow chart of inclusion of study population

MIMIC-Ⅳ, Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care Ⅳ; ICU, intensive care unit; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; AG, admission glucose; AIDS, accquired immune deficiency syndrome.

1.3. 数据提取

本研究以首次进入ICU后是否出现ICU内死亡及ICU内治疗时间作为研究结局变量,结合既往研究[2, 13-14]及MIMIC-Ⅳ数据库特征,提取协变量,包括人口学特征、合并症、共病指数、生命体征、实验室指标、格拉斯哥昏迷评分(Glasgow coma scale, GCS)、牛津急性疾病严重程度评分(Oxford acute severity of illness score, OASIS)[15]。分别采用如下公式计算SIH指标:SHR1(mmol/L)=AG/[(1.59× HbA1c)-2.59][4],SHR2=AG/HbA1c[16],GG(mmol/L)=AG -[(1.59×HbA1c) -2.59][5],将SIH指标按照百分位数分为Q1(0~25%)、Q2(>25%~75%)、Q3(>75%~100%)三组,详见表 1。上述数据均取进入ICU后24 h内的测量值,对于多次测量的指标,采用多次测量的平均值,对于缺失值,若缺失比例>20%,则不纳入该变量,若缺失比例≤20%,则采用多重插补法进行填补[17]。

表 1.

5 249例ICU患者的基本特征

Characteristic of 5 249 patients in the ICU

| Variables | Total (n=5 249) | Survival (n=4 852) | Death (n=397) | P value |

| ICU, intensive care unit; AG, admission glucose; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; GG, glucose gap. | ||||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Insurance, n(%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Medicaid | 302 (5.8) | 289 (6.0) | 13 (3.3) | |

| Medicare | 2 289 (43.6) | 2 074 (42.7) | 215 (54.2) | |

| Other | 2 658 (50.6) | 2 489 (51.3) | 169 (42.6) | |

| Marital status, n(%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Divorced | 407 (7.8) | 378 (7.8) | 29 (7.3) | |

| Married | 2 788 (53.1) | 2 594 (53.5) | 194 (48.9) | |

| Single | 1 372 (26.1) | 1 280 (26.4) | 92 (23.2) | |

| Widowed | 682 (13.0) | 600 (12.4) | 82 (20.7) | |

| Length of stay/d, M(P25, P75) | 2.24 (1.28, 4.58) | 2.17 (1.26, 4.23) | 4.25 (2.12, 9.16) | < 0.001 |

| Male, n(%) | 3 088 (58.8) | 2 895 (59.7) | 193 (48.6) | < 0.001 |

| Age/year, M(P25, P75) | 68.00 (56.00, 78.00) | 67.00 (56.00, 77.00) | 76.00 (62.00, 84.00) | < 0.001 |

| Complications | ||||

| Myocardial infarction, n(%) | 1 410 (26.9) | 1 292 (26.6) | 118 (29.7) | 0.201 |

| Congestive heart failure, n(%) | 1 506 (28.7) | 1 344 (27.7) | 162 (40.8) | < 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n(%) | 651 (12.4) | 595 (12.3) | 56 (14.1) | 0.321 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n(%) | 1 999 (38.1) | 1 769 (36.5) | 230 (57.9) | < 0.001 |

| Dementia, n(%) | 176 (3.4) | 152 (3.1) | 24 (6.0) | 0.003 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease, n(%) | 1 042 (19.9) | 953 (19.6) | 89 (22.4) | 0.205 |

| Rheumatic disease, n(%) | 143 (2.7) | 130 (2.7) | 13 (3.3) | 0.589 |

| Peptic ulcer, n(%) | 63 (1.2) | 56 (1.2) | 7 (1.8) | 0.406 |

| Mild liver disease, n(%) | 291 (5.5) | 238 (4.9) | 53 (13.4) | < 0.001 |

| Severe liver disease, n(%) | 71 (1.4) | 52 (1.1) | 19 (4.8) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes with chronic complication, n(%) | 550 (10.5) | 507 (10.4) | 43 (10.8) | 0.878 |

| Diabetes without chronic complication, n(%) | 1 561 (29.7) | 1 439 (29.7) | 122 (30.7) | 0.695 |

| Paraplegia, n(%) | 975 (18.6) | 843 (17.4) | 132 (33.2) | < 0.001 |

| Renal disease, n(%) | 896 (17.1) | 791 (16.3) | 105 (26.4) | < 0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, ±s | 5.47±2.48 | 5.36±2.44 | 6.91±2.51 | < 0.001 |

| Vital signs,M(P25, P75) | ||||

| Heart rate/(beats/min) | 79.97 (71.74, 89.58) | 79.77 (71.72, 89.11) | 83.61 (72.40, 95.48) | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate/(times/min) | 18.20 (16.58, 20.23) | 18.08 (16.51, 20.04) | 19.90 (17.81, 22.57) | < 0.001 |

| Temperature/℃ | 36.81 (36.62, 37.04) | 36.81 (36.62, 37.02) | 36.87 (36.62, 37.25) | < 0.001 |

| Oxygen saturation/% | 96.83 (95.60, 97.97) | 96.80 (95.60, 97.93) | 97.36 (95.61, 98.59) | 0.001 |

| Weight/kg | 84.13 (70.71, 100.08) | 84.50 (71.19, 100.37) | 80.00 (65.80, 96.00) | < 0.001 |

| Lab indexes, M(P25, P75) | ||||

| White blood cell count/(×109/L) | 10.80 (8.27, 13.67) | 10.60 (8.18, 13.48) | 12.80 (10.25, 16.25) | < 0.001 |

| Chloride/(mmol/L) | 104.60 (101.67, 107.00) | 104.50 (101.75, 107.00) | 105.00 (100.05, 108.00) | 0.157 |

| Creatinine/(mg/dL) | 0.93 (0.75, 1.20) | 0.90 (0.75, 1.20) | 1.23 (0.87, 1.98) | < 0.001 |

| AG/(mg/dL) | 7.29 (6.39, 8.89) | 7.22 (6.34, 8.72) | 8.37 (7.02, 10.69) | < 0.001 |

| Sodium/(mmol/L) | 138.20 (136.20, 140.50) | 138.02 (136.17, 140.28) | 139.40 (136.67, 142.11) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin/(g/dL) | 11.54 (10.06, 12.90) | 11.59 (10.11, 12.96) | 11.00 (9.45, 12.55) | < 0.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen/(mg/dL) | 16.67 (12.50, 23.50) | 16.00 (12.25, 22.50) | 25.00 (16.00, 41.40) | < 0.001 |

| Anion gap/(mEq/L) | 14.00 (12.00, 16.00) | 13.67 (12.00, 15.67) | 16.00 (14.00, 18.31) | < 0.001 |

| Potassium/(mEq/L) | 4.14 (3.87, 4.42) | 4.13 (3.88, 4.40) | 4.17 (3.85, 4.56) | 0.073 |

| Blood platelet count/(×109/L) | 193.71 (152.56, 244.50) | 193.00 (152.84, 243.66) | 202.00 (150.67, 252.00) | 0.547 |

| Thrombin time/s | 13.27 (12.05, 14.70) | 13.20 (12.00, 14.60) | 13.75 (12.35, 16.10) | < 0.001 |

| Prothrombin time/s | 30.65 (27.30, 38.70) | 30.56 (27.30, 38.28) | 31.70 (28.40, 47.65) | < 0.001 |

| International normalized ratio | 1.20 (1.10, 1.30) | 1.20 (1.10, 1.30) | 1.25 (1.10, 1.50) | < 0.001 |

| Bicarbonate/(mEq/L) | 23.50 (21.60, 25.40) | 23.67 (22.00, 25.50) | 21.80 (19.00, 24.00) | < 0.001 |

| Haematocrit/% | 34.70 (30.90, 38.80) | 34.80 (31.07, 38.80) | 33.88 (29.05, 38.40) | 0.004 |

| Red blood cell distribution width/% | 13.76 (13.10, 14.70) | 13.70 (13.10, 14.65) | 14.40 (13.60, 15.80) | < 0.001 |

| Calcium/(mg/dL) | 8.65 (8.20, 9.00) | 8.65 (8.24, 9.00) | 8.53 (8.10, 9.00) | 0.003 |

| HbA1c/% | 5.90 (5.50, 6.80) | 5.86 (5.50, 6.80) | 5.90 (5.50, 6.70) | 0.798 |

| Scores, M(P25, P75) | ||||

| GCS | 13.00 (10.00, 14.00) | 14.00 (11.00, 14.00) | 8.00 (6.00, 11.00) | < 0.001 |

| SIH-related index | ||||

| SHR1, M(P25, P75) | 1.04 (0.90, 1.20) | 1.03 (0.90, 1.18) | 1.19 (1.01, 1.42) | < 0.001 |

| GG, M(P25, P75) | 0.28 (-0.71, 1.31) | 0.20 (-0.75, 1.22) | 1.31 (0.11, 2.87) | < 0.001 |

| SHR2, M(P25, P75) | 1.20 (1.06, 1.37) | 1.19 (1.05, 1.35) | 1.39 (1.19, 1.64) | < 0.001 |

| SHR1 tertile, n(%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Q1(≤0.90) | 1 288 (24.5) | 1 241 (25.6) | 47 (11.8) | |

| Q2(>0.90, ≤1.20) | 2 681 (51.1) | 2 523 (52.0) | 158 (39.8) | |

| Q3(>1.20) | 1 280 (24.4) | 1 088 (22.4) | 192 (48.4) | |

| SHR2 tertile, n(%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Q1(≤1.06) | 1 342 (25.6) | 1 289 (26.6) | 53 (13.4) | |

| Q2(>1.06, ≤1.37) | 2 594 (49.4) | 2 456 (50.6) | 138 (34.8) | |

| Q3(>1.37) | 1 313 (25.0) | 1 107 (22.8) | 206 (51.9) | |

| GG tertile, n(%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Q1(≤-0.71) | 1 320 (25.1) | 1 270 (26.2) | 50 (12.6) | |

| Q2(>-0.71, ≤1.32) | 2 631 (50.1) | 2 482 (51.2) | 149 (37.5) | |

| Q3(>1.32) | 1 298 (24.7) | 1 100 (22.7) | 198 (49.9) | |

1.4. 统计学分析

使用Navicat Premium 15软件编写结构化语句从数据库提取所需数据并进行预处理,使用R 4.1.2软件进行统计分析。符合正态分布的定量数据以x±s表示,组间差异采用t检验,不符合正态分布的定量数据以M(P25, P75)表示,组间差异采用Wilcoxon秩和检验,计数资料以频数和百分比表示,组间差异采用χ2检验和Fisher确切概率法检验。通过绘制Kaplan-Meier曲线,采用Log-rank法比较不同SIH指标分组间的生存差异; 采用Cox回归分析SIH指标与ICU内患者死亡风险之间的关系,并对回归模型进行等比例风险假设检验和共线性诊断,若方差膨胀因子>5则认为存在共线性,并剔除该变量; 采用限制性立方样条探究SIH指标和ICU患者28 d死亡风险之间的线性关系; 为进一步探究指标的预测效能,不同定义的SIH指标对ICU患者死亡风险预测的受试者工作特征(receiver operation characteristic, ROC)曲线下面积(area under curve, AUC),采用Delong检验进行比较,并将预测性能较好的指标纳入OASIS危险评分中,以评估其改善危险评分区分度和校准度的能力,其中AUC越大则表明区分度越好,Brier score越小则表明校准度越好[18],同时进一步探究了SHR2与不同分层变量之间的交互作用,所有检验以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. 研究对象基本特征

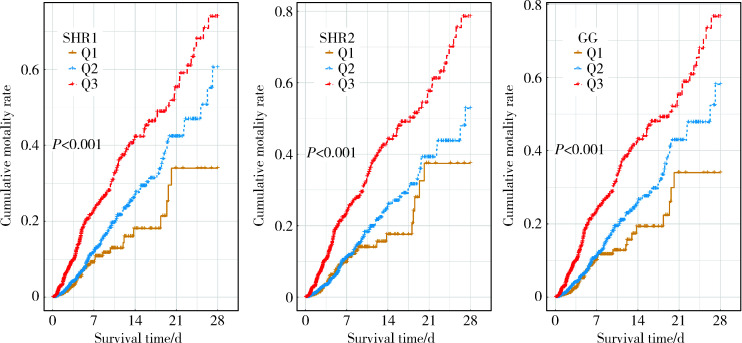

本研究共纳入5 249例ICU患者,其中发生ICU内死亡的患者占7.56%,所有纳入的患者在ICU内接受治疗的时间为2.24(1.28, 4.58) d,患者年龄为68.00 (56.00, 78.00)岁,男性多于女性,超半数患者处于已婚状态,以脑血管疾病、充血性心力衰竭患者居多,三组SIH指标中Q3组患者发生死亡的比例均高于Q2和Q1组(P < 0.05),Kaplan-Meier曲线显示不同SIH指标分组间生存差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),详见表 1、图 2。

图 2.

3种SIH指标分组Kaplan-Meier曲线

Kaplan-Meier curves of three SIH indexes

SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; GG, glucose gap; SIH, stress-induced hyperglycemia.

2.2. SIH指标和ICU患者28 d死亡风险的关联分析

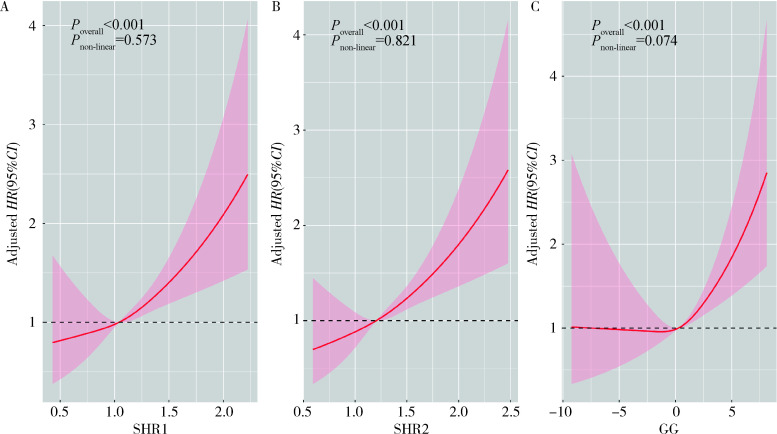

模型1中将SHR1、SHR2、GG分别纳入Cox回归中,三者对ICU患者死亡风险的影响均差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),以最低组Q1为参照组,最高组Q3组人群的死亡风险均显著增高(HRSHR1=2.663, HRSHR2=2.558, HRGG=2.739,P < 0.05),模型2在模型1的基础上进一步调整了人口学特征和共病情况,相较于最低组Q1,Q3组和Q2组仍与ICU患者死亡风险有较强的关联,Q3组能显著提高ICU患者死亡风险(HRSHR1=2.548, HRSHR2=2.615, HRGG=2.519,P < 0.05),模型3在模型2的基础上进一步校正了实验室指标,最高组Q3和最低组Q1相比差异仍有统计学意义(HRSHR1=1.545, HRSHR2=1.602, HRGG=1.442,P < 0.05),且随着SIH指标的增加,ICU患者死亡风险也逐渐增加(Ptrend < 0.05)。限制性立方样条分析表明随着SIH指标的升高,ICU患者死亡风险也呈现线性上升(Poverall < 0.05, Pnon-linear>0.05),在三个模型中,变量之间不存在明显的共线性(方差膨胀因子 < 5), 详见表 2, 图 3。

表 2.

SIH与ICU患者28 d死亡风险的关联

Association of SIH with 28 d mortality risk in ICU patients

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||

| HR(95%CI) | P | P trend | HR(95%CI) | P | P trend | HR(95%CI) | P | P trend | |||

| Model 1, crude model; Model 2, adjusted for model 1+ insurance, marital status, gender, age, myocardial infarction, congestive heart-failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatic disease, peptic ulcer, mild liver disease, severe liver disease, diabetes with chronic complication, diabetes without chronic complication, paraplegia, renal disease; Model 3, adjusted for model 2+ heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, oxygen saturation, weight, white blood cell count, chloride, creatinine, sodium, blood urea nitrogen, anion gap, potassium, blood platelet count, thrombin time, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, bicarbonate, haematocrit, red blood cell distribution width, calcium. SIH, stress-induced hyperglycemia; ICU, intensive care unit; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; GG, glucose gap. | |||||||||||

| SHR1 | 3.692(2.793, 4.881) | < 0.001 | 4.250(3.127, 5.776) | < 0.001 | 2.037(1.427, 2.908) | < 0.001 | |||||

| SHR1 tertile | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Q1(≤0.90) | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Q2(>0.90, ≤1.20) | 1.421 (1.013, 1.992) | 0.042 | 1.254 (0.889, 1.768) | 0.198 | 1.068 (0.753, 1.516) | 0.712 | |||||

| Q3(>1.20) | 2.663 (1.907, 3.710) | < 0.001 | 2.548 (1.816, 3.576) | < 0.001 | 1.545 (1.077, 2.217) | 0.018 | |||||

| SHR2 | 3.580 (2.767, 4.632) | 4.098 (3.084, 5.445) | < 0.001 | 2.059 (1.488, 2.850) | |||||||

| SHR2 tertile | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Q1(≤1.06) | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Q2(>1.06, ≤1.37) | 1.188 (0.856, 1.648) | 0.302 | 1.163 (0.836, 1.619) | 0.206 | 1.057 (0.754, 1.482) | 0.747 | |||||

| Q3(>1.37) | 2.558 (1.869, 3.502) | < 0.001 | 2.615 (1.902, 3.596) | < 0.001 | 1.602 (1.142, 2.249) | 0.006 | |||||

| GG | 1.215 (1.164, 1.269) | < 0.001 | 1.229 (1.172, 1.289) | < 0.001 | 1.110 (1.055, 1.168) | < 0.001 | |||||

| GG tertile | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Q1(≤-0.71) | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Q2(>-0.71, ≤1.32) | 1.407 (1.005, 1.971) | 0.047 | 1.215 (0.860, 1.718) | 0.270 | 1.014 (0.711, 1.445) | 0.940 | |||||

| Q3(>1.32) | 2.739 (1.972, 3.805) | < 0.001 | 2.519 (1.802, 3.522) | < 0.001 | 1.442 (1.001, 2.061) | 0.044 | |||||

图 3.

SIH限制性立方样条图

SIH restricted cubic spline diagram

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; GG, glucose gap; SIH, stress-induced hyperglycemia.

2.3. ICU患者28 d死亡风险的ROC曲线分析

HbA1c、AG、SHR1、SHR2、GG五个血糖相关指标的AUC经Delong检验结果显示,HbA1c和AG预测效果不如SIH指标(P < 0.05)。在三个SIH指标中,SHR2和GG的预测效果优于SHR1 (P < 0.05),详见表 3,图 4,同时将SHR2纳入OASIS危险评分中, SHR2能显著改善原始危险评分的区分度和校准度:AUCOASIS[0.820(0.791~0.848)] vs. AUCOASIS+SHR2 [0.832(0.804~0.859)], P < 0.05; BrierscoreOASIS (0.071) vs. BrierscoreOASIS+SHR2(0.069)。

表 3.

血糖相关指标的AUC比较

Comparison of glucose-related indexes AUC

| Variables | AUC(95%CI) | P a | P b | P c | P d |

| a, Hba1c as the reference; b, AG as the reference; c, SHR1 as the reference; d, SHR2 as the reference. AUC, area under curve; HbA1c, glyca-ted hemoglobin; AG, admission glucose; SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; GG, glucose gap. | |||||

| Hba1c | 0.504 (0.475-0.532) | ||||

| AG | 0.650 (0.618-0.675) | < 0.001 | |||

| SHR1 | 0.680 (0.650-0.709) | < 0.001 | 0.015 | ||

| SHR2 | 0.691 (0.661-0.720) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.007 | |

| GG | 0.685 (0.655-0.714) | < 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.111 |

图 4.

血糖相关指标ROC曲线

ROC curves of glucose-related indexes

HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; AG, admission glucose; SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; GG, glucose gap; ROC, receiver operation charac-teristic.

2.4. 交互作用分析结果

将性别、年龄、共病等因素进行分层,探究不同人群的SHR2与ICU患者28 d全因死亡风险之间的关系,结果表明在大多数分层中的交互作用差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。在患有脑血管疾病的患者中,SHR2与死亡风险的关联性比未患有脑血管疾病患者的关联性更强[HR(95%CI): 3.148 (1.872, 5.293) vs. 2.019(1.299, 3.137), Pinteraction < 0.05];而与患心肌梗死和慢性阻塞性肺炎的患者比较,未患心肌梗死和慢性阻塞性肺炎的患者SHR2对ICU患者28 d死亡风险的影响更大[HR(95%CI): 2.580(1.739~3.828)、HR(95%CI): 2.427(1.654~3.560), Pinteraction < 0.05],详见图 5。

图 5.

不同亚组分析森林图

Forest plot of different subgroups

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

3. 讨论

本研究以重症医学MIMIC-Ⅳ数据库中的ICU患者为研究对象,探究SIH对患者28 d死亡风险的影响,研究结果表明SIH与ICU患者28 d死亡风险有关,SIH指标与ICU患者28天死亡风险呈线性相关,在评估SIH的指标中,SHR2和GG的预测效能更好,且SHR2能显著提高OASIS危险评分的区分度和校准度。

从SIH指标和ICU患者28 d死亡风险之间的关系来看,本研究中模型3调整了协变量后,随着SIH指标的增加,患者死亡风险仍逐渐增加(Ptrend < 0.05),SHR2高值组Q3是低值组Q1患者死亡风险的1.602倍,同时限制性立方样条也表明二者存在线性相关,提示SIH是ICU患者28 d死亡风险的独立影响因素,这与既往研究[6]保持一致。此外,本研究亚组分析表明在心肌梗死患者中,SHR2和死亡风险之间的关联差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),这可能是因为本研究中研究对象多为老年人群,有研究表明在老年人群中,SIH对心肌梗死患者预测价值不一致,有时甚至不显著[19]。此外,有研究表明在机械血栓切除后大血管闭塞所致的缺血性卒中患者中,SHR高值组的患者三个月死亡风险较低值组增加3.55倍,院内死亡风险增加6. 79倍[20],这与本研究结果一致。本研究还表明SHR2能增加慢性阻塞性肺炎患者ICU内的死亡风险,Li等[21]研究肺功能和血糖之间的关系也表明,血糖异常者肺功能下降更为严重,与本研究一致。

从临床生理机制来看,SIH与患者死亡风险的关联机制尚未被完全了解,Zonneveld等[22]认为患者在急性期间发生SIH,进而刺激机体发生更大炎症和神经内分泌紊乱反应,同时SIH与炎症标志物增加、细胞毒性T细胞的表达增强、T细胞的表达减少有关联; Ergul等[23]认为应激性高血糖可能通过诱导内皮细胞凋亡、内皮细胞功能障碍和氧化应激等机制直接导致不良结局。

从SIH对ICU患者28 d死亡风险的预测效能来看,三个SIH指标分组后均能将患者危险程度区分开(P < 0.05); 同时,与血糖相关的三个相对指标的AUC显著高于血糖绝对指标,表明血糖相对指标对ICU患者28 d死亡风险有更好的预测效能,这与既往研究[24]保持一致。同时本研究还表明SIH指标中SHR2和GG较SHR1有更好的预测效能。此外,将SHR2纳入OASIS评分中能显著提高模型的预测效能,Lee等[6]将SHR纳入急性生理学和慢性健康评估(acute physiology and chronic health eva-luation Ⅱ, APACHEⅡ)中,也能显著提高原始评分的预测性能, AUCSHR[0.782(0.758~0.804)] vs. AUCSHR+APACHEⅡ[0.771(0.747~0.794])], P= 0.014,提示SHR有较好的临床应用价值。

本文存在以下局限性:首先,MIMIC-Ⅳ数据库为单中心数据库,可能会限制该研究结果对其他中心患者的适用性,因此,应考虑在多个中心临床数据进一步探究; 其次,由于MIMIC-Ⅳ数据库特征的限制,一些样本无法纳入,比如一些重要的协变量缺失严重、无AG或HbA1c记录的患者; 最后,这是一项回顾性分析,难以避免各种偏倚的影响,SIH与患者死亡风险之间的关系有待于在未来的前瞻性队列研究中进一步验证。

综上所述,本研究表明SIH是ICU患者28 d死亡风险的独立影响因素,在测量SIH的指标中,SHR2和GG有较好的预测效能,SIH有助于危重患者的早期识别,可为重症监护患者的临床管理和决策提供参考。

Funding Statement

国家重点研发计划(2018YFC1311700, 2018YFC1311703)

Supported by the National Key Development and Program of China(2018YFC1311700, 2018YFC1311703)

References

- 1.Mousai O, Tafoureau L, Yovell T, et al. Clustering analysis of geriatric and acute characteristics in a cohort of very old patients on admission to ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(12):1726–1735. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06868-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS, Preiser JC. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet. 2009;373(9677):1798–1807. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60553-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harp JB, Yancopoulos GD, Gromada J. Glucagon orchestrates stress-induced hyperglycaemia. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(7):648–653. doi: 10.1111/dom.12668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts GW, Quinn SJ, Valentine N, et al. Relative hyperglycemia, a marker of critical illness: Introducing the stress hyperglycemia ratio. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(12):4490–4497. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao WI, Wang JC, Chang WC, et al. Usefulness of glycemic gap to predict ICU mortality in critically ill patients with diabetes. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(36):e1525. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee TF, Drake SM, Roberts GW, et al. Relative hyperglycemia is an independent determinant of in-hospital mortality in patients with critical illness. Critical Care Medicine. 2020;48(2):e115–e122. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mcdonnell ME, Garg R, Gopalakrishnan G, et al. Glycemic gap predicts mortality in a large multicenter cohort hospitalized with covid-19. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108(3):718–725. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia Z, Gu T, Zhao Z, et al. The stress hyperglycemia ratio, a novel index of relative hyperglycemia, predicts short-term mortality in critically ill patients after esophagectomy. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;13(1):56–66. doi: 10.21037/jgo-22-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen G, Li M, Wen X, et al. Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio and in-hospital outcomes in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:698725. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.698725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu B, Pan Y, Jing J, et al. Stress hyperglycemia and outcome of non-diabetic patients after acute ischemic stroke. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1003. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo Y, Wang G, Jing J, et al. Stress hyperglycemia may have higher risk of stroke recurrence than previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13(6):9108–9118. doi: 10.18632/aging.202797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson A, Bulgarelli L, Pollard T, et al. Mimic-Ⅳ documentation (version 1.0)[EB/OL]. (2021-01-01)[2022-10-01]. https://mimic.mit.edu/docs/iv/

- 13.Koyfman L, Brotfain E, Erblat A, et al. The impact of the blood glucose levels of non-diabetic critically ill patients on their clinical outcome. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2018;50(1):20–26. doi: 10.5603/AIT.2018.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olariu E, Pooley N, Danel A, et al. A systematic scoping review on the consequences of stress-related hyperglycaemia. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0194952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson AE, Kramer AA, Clifford GD. A new severity of illness scale using a subset of acute physiology and chronic health evaluation data elements shows comparable predictive accuracy. Cri-tical Care Medicine. 2013;41(7):1711–1718. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a24fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su YW, Hsu CY, Guo YW, et al. Usefulness of the plasma glucose concentration-to-HbA1c ratio in predicting clinical outcomes during acute illness with extreme hyperglycaemia. Diabetes Metab. 2017;43(1):40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2016.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allison PD. Multiple imputation for missing data: A cautionary tale. Sociol Methods Res. 2000;28(3):301–309. doi: 10.1177/0049124100028003003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy AH. A new decomposition of the brier score: Formulation and interpretation. Mon Weather Rev. 1986;114(12):2671–2673. doi: 10.1175/1520-0493(1986)114<2671:ANDOTB>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolau JC, Serrano CV Jr, Giraldez RR, et al. In patients with acute myocardial infarction, the impact of hyperglycemia as a risk factor for mortality is not homogeneous across age-groups. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):150–152. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merlino G, Pez S, Gigli GL, et al. Stress hyperglycemia in patients with acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion undergoing mechanical thrombectomy. Front Neurol. 2021;12:725002. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.725002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W, Ning Y, Ma Y, et al. Association of lung function and blood glucose level: A 10-year study in China. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):444. doi: 10.1186/s12890-022-02208-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zonneveld TP, Nederkoorn PJ, Westendorp WF, et al. Hyperglycemia predicts poststroke infections in acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2017;88(15):1415–1421. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ergul A, Abdelsaid M, Fouda AY, et al. Cerebral neovascularization in diabetes: Implications for stroke recovery and beyond. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(4):553–563. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai ZM, Zhang MM, Feng RQ, et al. Fasting blood glucose-to-glycated hemoglobin ratio and all-cause mortality among chinese in-hospital patients with acute stroke: A 12-month follow-up study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):508. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03203-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]